Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Diabetes affects 537 million people globally, with 34% expected to develop foot ulceration in their lifetime. Diabetes-related foot ulceration causes strain on health care systems worldwide, necessitating provision of high-quality evidence to guide their management. Given heterogeneity of reported outcomes, a core outcome set (COS) was developed to standardize outcome measures in studies assessing treatments for diabetes-related foot ulceration.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

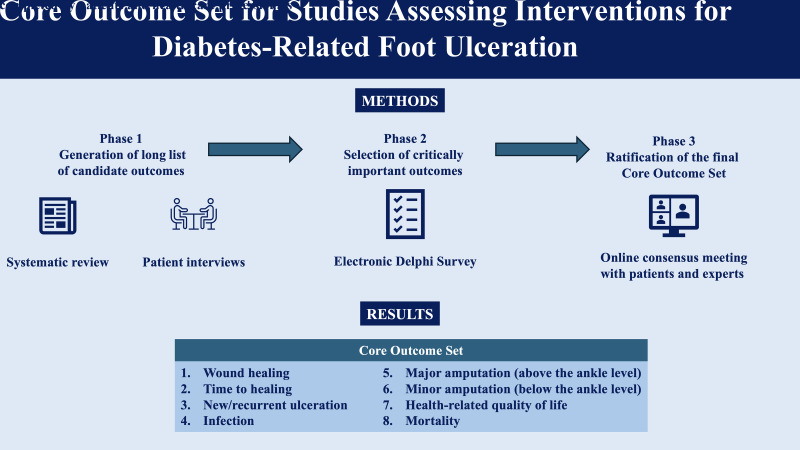

The COS was developed using Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) methodology. A systematic review and patient interviews generated a long list of outcomes that were rated by patients and experts using a nine-point Likert scale (from 1 [not important] to 9 [critical]) in the first round of the Delphi survey. Based on predefined criteria, outcomes without consensus were reprioritized in a second Delphi round. Critical outcomes and those without consensus after two Delphi rounds were discussed in the consensus meeting where the COS was ratified.

RESULTS

The systematic review and patient interviews generated 103 candidate outcomes. The two consecutive Delphi rounds were completed by 336 and 176 respondents, resulting in an overall second round response rate of 52%. Of 37 outcomes discussed in the consensus meeting (22 critical and 15 without consensus after the second round), 8 formed the COS: wound healing, time to healing, new/recurrent ulceration, infection, major amputation, minor amputation, health-related quality of life, and mortality.

CONCLUSIONS

The proposed COS for studies assessing treatments for diabetes-related foot ulceration was developed using COMET methodology. Its adoption by the research community will facilitate assessment of comparative effectiveness of current and evolving interventions.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Diabetes is a global public health concern, currently affecting 537 million people worldwide (1) and directly resulting in more than one million deaths annually (2). In addition to major cardiovascular, renal, and eye disease, people with diabetes are also at high risk of foot complications, including neuropathy, peripheral artery disease, infection, and foot ulcers. While most ulcers will heal with expert multidisciplinary care, major lower limb amputations in people with diabetes are invariably preceded by ulceration (3). Current figures suggest that 19–34% of people with diabetes develop foot ulceration in their lifetime (4).

Diabetes-related foot ulceration results in significant disability and economic burden (5). Dependent on the type of diabetes and sex, rates of limb loss are between 6 and 32 times those of the general population (6).

The ability to confidently select the most effective evidence-based interventions for diabetes-related foot ulceration is important to improve patient outcomes and current pathways of care. Despite previous attempts at standardizing reporting of studies on the prevention and management of diabetes-related foot ulceration (7), a subsequent systematic review demonstrated ongoing marked heterogeneity in reported outcomes, hindering the selection of the most effective treatments (8).

Similar issues have been noted in other disease processes (9), and, as a result, the international Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative was introduced after consultation with trialists, clinicians, funders, regulators, and patients to help standardize outcome reporting across studies and facilitate the choice of useful metrics allowing for direct comparison of health care interventions (10). The COMET initiative outlines rigorous methodology for development of a disease- or treatment-specific core outcome set (COS) that is a minimum set of outcomes to be measured and reported in the studied area. Since its introduction, 262 COS have been developed and implemented into research practice (11). For instance, the COS for studies on rheumatoid arthritis has been used in 158 randomized controlled trials between 2009 and 2019 (12).

The aim of this study was to develop a COS for studies assessing the effectiveness and safety of interventions to treat diabetes-related foot ulceration.

Research Design and Methods

The COS for studies assessing interventions for diabetes-related foot ulceration was developed in four phases in line with the standardized COMET methodology (10). The study received approval from South Central - Berkshire B Research Ethics Committee (Nottingham, U.K.) (REC reference: 18/SC/0478) and was registered with the COMET initiative prior to the commencement of the first phase (13). The development process of this COS has been reported according to the Core Outcome Set – Standards for Reporting Statement (COS-STAR) (14).

Scope of the COS

The COS has been designed for use in all trials and clinical research studies evaluating safety and effectiveness of all potential interventions for diabetes-related foot ulceration in adults aged ≥16 years with a diagnosis of diabetes.

Phase I: Generation of the Long List of Outcomes

Systematic Review (October 2021)

A systematic review of outcomes reported in people undergoing interventions for diabetes-related foot ulcers was undertaken to generate a list of outcomes for consideration in the COS; this systematic review has been published elsewhere (8).

Patient Interviews (September 2022 to March 2023)

Using a topic guide developed in collaboration with a qualitative researcher (Supplementary Material), semistructured patient interviews were subsequently conducted to capture any additional outcomes considered to be important by patients that had not been identified in the systematic review. Adults with diabetes who were able to provide written consent were identified from multidisciplinary diabetic foot clinics within the Bristol, Bath and Weston Vascular Network. Given the heterogeneity of this population, patients were purposefully sampled to ensure representative views of those with lived experience of healed ulceration, orthopedic procedures, revascularization, foot debridement, and minor and major lower limb amputation. A minimum of 15 patients were expected to be interviewed. Patient recruitment was concluded when outcome saturation was reached, defined as no new outcomes in the preceding two interviews. Participating patients signed written consent forms prior to being interviewed via the Microsoft Teams platform. Interviews were then transcribed verbatim by the Microsoft Teams platform, and two independent researchers analyzed the transcripts to extract the additional outcomes.

Phase II: Delphi Process (May–December 2023)

First Round (May–August 2023)

The long list of outcomes, generated through the systematic review and patient interviews, was taken forward to two rounds of a Delphi survey. The Delphi survey was designed and delivered via the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) platform, a secure online application hosted by University of Bristol (15). An anonymous link to the survey was distributed through the mailing lists of key professional societies with an interest in diabetic foot disease, including the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF) and the Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland (VSGBI) diabetic foot specialist interest group. The link was also shared on social media, including X (formerly Twitter), and with patients attending multidisciplinary diabetic foot clinics in Bristol, Bath and Weston Vascular Network, and Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust. Given the ethical approval arrangements, only patients from the U.K. were able to participate.

Prior to accessing the survey, participants were taken to the introductory page containing detailed instructions and a downloadable participant information leaflet. The survey could only be activated once a participant completed a simplified electronic consent form. Additionally, the health care professionals were asked to specify their specialty, country of practice, and years of clinical experience.

The long list of outcomes was presented in five core areas including death, physiological/clinical, life impact, resource use, and adverse events using the COMET taxonomy (10). Each outcome was scored on a Likert scale from 1 (not important) to 9 (critically important). In keeping with previously used consensus criteria (9), all outcomes ranked as critical (7–9) by ≥70% of respondents and not important (1–3) by ≤15% of participants were automatically taken forward for consideration in COS. Similarly, outcomes ranked as not important (1–3) by ≥70% of participants and 7–9 by ≤15% of participants were automatically excluded. The outcomes not fulfilling the criteria for inclusion or exclusion were considered to lack consensus and were taken forward to the second round of the Delphi survey. The questionnaires were screened for duplicates, and, if multiple responses were submitted from the same e-mail address, only the questionnaire with the highest number of outcomes scored was taken forward to the second round, in line with previous Delphi studies (16).

Second Round (September–November 2023)

A personalized link to the second round of the Delphi survey was sent out to everyone who completed the first round. Participants could see their previous responses in comparison with the overall group ranking in the form of both a histogram and a median rating for each outcome. Nonrespondents received three reminder e-mails to complete the survey.

Phase III: Steering Group Meeting (December 2023)

Given the expected heterogeneity of the patient population of interest, the steering group—composed of one trial methodologist (J.N.), four vascular surgeons (R.J.H., D.R., A.S., and C.A.), and one diabetologist (F.G.)—reviewed and rationalized the list of outcomes rated as either critical or without consensus to generate a list of relevant outcomes that would be feasibly discussed in the consensus meeting. The rationalization process included deduplication of outcomes, removal of measures that either were not considered to be true outcomes or were relevant only to a specific subgroup of patients with diabetes-related foot ulceration (such as revascularization-specific outcomes).

Phase IV: Consensus Meeting (January 2024)

The consensus meeting was held online on the Microsoft Teams platform and was attended by patients with lived experience of diabetes-related foot ulceration and international experts in the field of diabetes-related foot disease, including diabetologists, podiatrists, vascular, orthopedic plastic surgeons, movement scientists, and wound care specialists. The expert panel was selected purposefully from the members of the IWGDF and VSGBI diabetic foot specialist interest group to ensure balanced representation from the relevant stakeholder groups. All attendees provided written consent prior to attending the meeting.

All outcomes considered to be either critical or lacking consensus during the Delphi rounds were discussed in the consensus meeting. Each outcome was open for voting using the consensus criteria from the Delphi stage using anonymous Mentimeter software (Mentimeter; Stockholm, Sweden). This followed a detailed discussion for each outcome between all the stakeholders to help create the final feasible and practical COS.

Data Sharing

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published article and the Supplementary Material.

Results

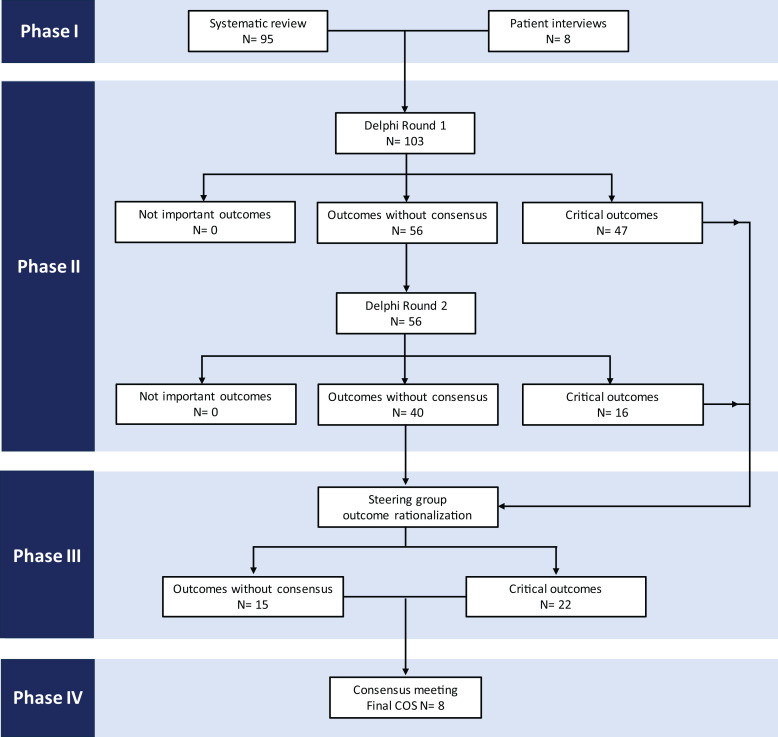

An overview of the four phases of COS development is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

The four phases of COS development. Critical outcomes indicate items that have been rated as 7–9 by at least 70% of respondents at a given stage. Outcomes without consensus are those that have not been rated as either critical or not important by enough respondents.

Phase I: Generation of the Long List of Outcomes

Systematic Review

The systematic review generated 714 unique outcomes that were subsequently merged into 95 outcomes following application of the COMET taxonomy (8).

Patient Interviews

In total, 18 patients were interviewed, with a median age of 69 (interquartile range 62.5–74.3) years. Most patients were men (n = 17, 94%). Within the group, four patients had experienced surgical debridement, nine had undergone revascularization, eight had experienced minor and two had experienced major lower limb amputation, three had had orthopedic reconstructive surgery, and four had experienced foot ulceration that had healed with wound care and offloading.

Patient interviews yielded eight additional outcomes, which included wound bleeding, foot swelling, weight loss, requirement for foot elevation, reduction in cigarette smoking, psychological impact on partner, complications of debridement, and complications of plaster casting.

Phase II: Delphi Process

The 103 unique outcomes identified through systematic review (n = 95) and patient interviews (n = 8) were taken forward to the Delphi survey. The two consecutive rounds were sequentially completed between May 2023 and November 2023. Following removal of 26 duplicate submissions, 336 responses were recorded (281 from health care professionals and 55 from patients) in the first round and 176 (152 from health care professionals and 24 patients) in the second round, corresponding to a 52% second round response rate (Table 1). Among the participating health care professionals, two-thirds practiced in the U.K., and the remaining third represented 33 other countries across six continents.

Table 1.

Demographics of health care professionals participating in the Delphi survey

| Round 1 | Round 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | ||

| Total | 336 | 176 |

| Health care professionals | 281 (84) | 152 (86) |

| Patients | 55 (16) | 24 (14) |

| Clinical role of health care professionals | ||

| Doctor | 114 (41) | 65 (43) |

| Podiatrist | 133 (47) | 69 (45) |

| Nurse | 12 (4) | 8 (5) |

| Other | 22 (8) | 10 (7) |

| Specialty of health care professionals | ||

| Vascular Surgery | 72 (26) | 43 (28) |

| Orthopedics | 13 (5) | 4 (3) |

| Diabetes and Endocrinology | 124 (44) | 74 (49) |

| Other | 72 (26) | 31 (20) |

| Seniority of participating doctors | ||

| Consultant | 86 (75) | 51 (79) |

| Staff grade | 10 (9) | 4 (6) |

| Registrar | 18 (16) | 10 (15) |

| Years of clinical experience | ||

| <5 | 27 (10) | 10 (7) |

| 5–10 | 52 (19) | 27 (18) |

| 11–20 | 82 (29) | 51 (34) |

| >20 | 120 (43) | 64 (42) |

Values are provided as counts with proportion of the relevant group expressed in percentages in brackets. All health care professionals could express their specialty.

Of the 103 outcomes available for rating in the first round, 47 (46%) were ranked as critical and were automatically considered for inclusion in the final COS. The remaining 56 (54%) outcomes did not reach consensus and were taken forward to the second round. Of these, 16 (15%) were subsequently rerated as critical, giving a total of 63 critical outcomes, with 40 remaining without consensus (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of the two rounds of the Delphi survey

| Votes for exclusion (rated 1–3) (%) | Votes for inclusion (rated 7–9) (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 1 | Round 2 | Result |

| Mortality | 4 | 81 | Critical | ||

| Survival | 4 | 80 | Critical | ||

| Blood tests | 15 | 14 | 38 | 28 | No consensus |

| Anemia | 12 | 12 | 40 | 31 | No consensus |

| Serum metal deficiencies | 26 | 30 | 18 | 7 | No consensus |

| Markers of oxidative stress | 26 | 30 | 26 | 9 | No consensus |

| Lipid profile | 13 | 15 | 44 | 35 | No consensus |

| Serum inflammatory markers | 6 | 4 | 60 | 77 | Critical |

| Serum assessment of coagulation | 19 | 20 | 34 | 20 | No consensus |

| Clinical observations | 5 | 6 | 62 | 65 | No consensus |

| Cardiovascular events | 3 | 75 | Critical | ||

| Cardiovascular measurements | 6 | 6 | 57 | 66 | No consensus |

| Ear and labyrinth complications | 47 | 55 | 11 | 5 | No consensus |

| Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) | 4 | 81 | Critical | ||

| Serum glucose measurements | 16 | 10 | 48 | 46 | No consensus |

| Markers of insulin metabolism | 24 | 16 | 40 | 32 | No consensus |

| Development of cataract | 37 | 41 | 20 | 8 | No consensus |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 28 | 31 | 24 | 13 | No consensus |

| Effectiveness of pain relief | 9 | 7 | 56 | 61 | No consensus |

| Odor | 15 | 13 | 45 | 45 | No consensus |

| Pain | 3 | 72 | Critical | ||

| Biochemical markers of inflammation | 3 | 5 | 66 | 75 | Critical |

| Infection | 1 | 90 | Critical | ||

| Bacterial load | 10 | 7 | 52 | 60 | No consensus |

| Need for antimicrobial treatment | 3 | 82 | Critical | ||

| Osteomyelitis | 0 | 89 | Critical | ||

| Falls | 9 | 10 | 45 | 37 | No consensus |

| Metabolic and nutritional outcome | 11 | 9 | 37 | 33 | No consensus |

| Bone reconstruction | 7 | 5 | 54 | 58 | No consensus |

| Bone resection | 4 | 3 | 67 | 72 | Critical |

| Foot fracture | 4 | 2 | 59 | 69 | No consensus |

| Biochemical markers of wound healing | 9 | 9 | 48 | 50 | No consensus |

| Plantar pressure measurements | 5 | 4 | 59 | 69 | No consensus |

| Cerebrovascular events | 7 | 5 | 56 | 60 | No consensus |

| Measures of psychological morbidity | 4 | 2 | 58 | 67 | No consensus |

| Acute kidney injury | 5 | 8 | 63 | 72 | Critical |

| Respiratory complications | 13 | 13 | 41 | 30 | No consensus |

| Time to healing | 1 | 85 | Critical | ||

| Wound appearance | 5 | 70 | Critical | ||

| Wound healing | 0 | 91 | Critical | ||

| Change in ulcer dimensions | 1 | 79 | Critical | ||

| Genetic markers | 34 | 29 | 18 | 9 | No consensus |

| Failure of healing | 1 | 82 | Critical | ||

| Levels of exudate | 6 | 6 | 57 | 62 | No consensus |

| Degree of granulation tissue | 5 | 5 | 60 | 70 | Critical |

| Clinical improvement | 6 | 70 | Critical | ||

| Diabetes-related foot events | 4 | 79 | Critical | ||

| Ulcer recurrence | 0 | 89 | Critical | ||

| Healed diabetes-related foot ulcer | 1 | 82 | Critical | ||

| New ulceration | 1 | 89 | Critical | ||

| Measures of response to treatment | 4 | 75 | Critical | ||

| Maintenance of wound closure | 1 | 80 | Critical | ||

| Clinical features of chronic limb ischemia | 2 | 87 | Critical | ||

| Measurement of limb perfusion | 1 | 87 | Critical | ||

| Limb salvage | 0 | 94 | Critical | ||

| Revascularization | 1 | 89 | Critical | ||

| Primary patency | 3 | 79 | Critical | ||

| Secondary patency | 3 | 78 | Critical | ||

| Pattern of peripheral arterial disease | 4 | 74 | Critical | ||

| Wound bleeding | 13 | 8 | 44 | 44 | No consensus |

| Foot swelling | 7 | 8 | 51 | 64 | No consensus |

| Weight loss | 16 | 16 | 30 | 20 | No consensus |

| Foot elevation | 15 | 16 | 40 | 39 | No consensus |

| Reduction in cigarette smoking | 11 | 9 | 67 | 70 | Critical |

| Clinical signs of infection | 3 | 88 | Critical | ||

| Sleep disturbance | 9 | 9 | 41 | 48 | No consensus |

| Number of interventions | 5 | 4 | 56 | 54 | No consensus |

| Procedural success | 2 | 74 | Critical | ||

| Failure to complete the full course of treatment | 3 | 4 | 67 | 74 | Critical |

| Surgical intervention was undertaken | 3 | 76 | Critical | ||

| Logistics of delivery of health care | 8 | 5 | 52 | 86 | Critical |

| Patient experience | 1 | 0 | 69 | 82 | Critical |

| Safety | 3 | 78 | Critical | ||

| Tolerability | 3 | 1 | 69 | 86 | Critical |

| Self-reported psychological measures | 5 | 3 | 60 | 74 | Critical |

| Global quality of life | 3 | 1 | 65 | 83 | Critical |

| Health-related quality of life | 1 | 71 | Critical | ||

| Return to normal physical activities | 3 | 75 | Critical | ||

| Ambulatory status | 2 | 76 | Critical | ||

| Measure of foot function | 3 | 1 | 67 | 83 | Critical |

| Offloading | 2 | 80 | Critical | ||

| Role functioning | 2 | 1 | 69 | 83 | Critical |

| Psychological impact on partner | 5 | 6 | 50 | 56 | No consensus |

| Cost | 6 | 3 | 59 | 69 | No consensus |

| Product wastage | 14 | 13 | 40 | 46 | No consensus |

| Length of hospital stay | 3 | 3 | 67 | 67 | No consensus |

| Treatment duration | 3 | 1 | 64 | 78 | Critical |

| Wound care | 2 | 75 | Critical | ||

| Hospital admission | 2 | 79 | Critical | ||

| Major amputation | 2 | 93 | Critical | ||

| Revision amputation | 2 | 89 | Critical | ||

| Need for additional surgical procedures | 2 | 84 | Critical | ||

| Forefoot amputation | 2 | 87 | Critical | ||

| Minor amputation | 2 | 85 | Critical | ||

| Requirement for debridement | 3 | 81 | Critical | ||

| Requirement for social care | 6 | 4 | 58 | 68 | No consensus |

| Complications of revascularization | 2 | 80 | Critical | ||

| Complications of debridement | 2 | 74 | Critical | ||

| Complications of plaster casting | 3 | 3 | 66 | 69 | No consensus |

| Device related complications | 2 | 0 | 64 | 75 | Critical |

| Adverse events | 1 | 79 | Critical | ||

| Serious adverse events | 1 | 89 | Critical | ||

| Pruritus | 21 | 16 | 26 | 18 | No consensus |

Values are presented as a proportion of respondents selecting a specific rating for each outcome given in percentages. Only outcomes without consensus were rescored in the second round. Critical outcomes for potential inclusion in COS are defined as ≥70% of respondents scoring as 7–9 (critical) and 1–3 by ≤15%. Outcomes for exclusion are defined as ≥70% of respondents scoring as 1–3 (not important) and 7–9 by ≤15%. Indeterminate votes (neither for inclusion or exclusion) are not presented in the table.

Phase III: Steering Group Meeting

Given the unexpectedly high number of outcomes being considered as critical (n = 63) or lacking consensus (n = 40), the steering group rationalized the list of outcomes to ensure that the COS was relevant, practical, and feasible. Following review of the critical outcomes, 41 out of 63 (65%) were excluded from discussion in the subsequent consensus meeting, as 12 were captured in other outcomes, 11 were not universally relevant to all patients, 7 were not specific enough for inclusion in the COS, 5 were not a true outcome measure, and the remaining 6 were treatments and not outcomes (Supplementary Table 1).

A similar process was undertaken for outcomes without consensus, with 25 of 40 outcomes (63%) being excluded (Supplementary Table 2).

Phase IV: Consensus Meeting

The online consensus meeting was attended by 23 health care professionals who were international experts on diabetes-related foot disease and members of the IWGDF and/or VSGBI diabetic foot specialist interest group, and included 8 vascular surgeons, 4 diabetologists, 4 podiatrists, 2 orthopedic surgeons, 2 movement scientists, 1 plastic surgeon, 1 infectious diseases physician, and 1 trial methodologist, representing the U.K., U.S., Australia, the Netherlands, and Portugal. The meeting was also attended by five patient representatives from the U.K.

Following the Delphi process and steering committee review, 37 out of 103 long-listed outcomes (22 ranked as critical and 15 without consensus) were discussed and voted on in the consensus meeting (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of the consensus meeting in comparison with Delphi survey scores

| Participants voting for exclusion (rated 1–3) (%) | Participants voting as no consensus (rated 4–6) (%) | Participants voting for inclusion (rated 7–9) (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Delphi | Consensus meeting | Delphi | Consensus meeting | Delphi | Consensus meeting |

| Voted as critical in the Delphi process | ||||||

| Mortality | 4 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 81 | 100 |

| Wound healing | 0 | 0 | 9 | 4 | 91 | 96 |

| Major amputation | 2 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 93 | 95 |

| Minor amputation | 2 | 4 | 13 | 4 | 85 | 91 |

| Ulcer recurrence | 0 | 0 | 11 | 17 | 89 | 83 |

| Time to healing | 1 | 0 | 14 | 17 | 85 | 83 |

| Infection | 1 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 90 | 83 |

| New ulceration | 1 | 5 | 10 | 18 | 89 | 77 |

| Health-related quality of life | 1 | 4 | 28 | 24 | 71 | 72 |

| Osteomyelitis | 0 | 8 | 11 | 21 | 89 | 71 |

| Hospital admission | 2 | 0 | 19 | 35 | 79 | 65 |

| Revascularization | 1 | 12 | 10 | 28 | 89 | 60 |

| Global quality of life | 1 | 12 | 16 | 32 | 83 | 56 |

| Cardiovascular events | 3 | 12 | 22 | 35 | 75 | 54 |

| Ambulatory status | 2 | 17 | 22 | 35 | 76 | 48 |

| Pain | 2 | 15 | 25 | 42 | 73 | 42 |

| Change in ulcer dimensions | 1 | 8 | 20 | 54 | 79 | 38 |

| Acute kidney injury | 8 | 15 | 20 | 50 | 72 | 35 |

| Need for antimicrobial treatment | 3 | 38 | 15 | 33 | 82 | 29 |

| Need for additional surgical procedures | 2 | 28 | 14 | 44 | 84 | 28 |

| Degree of granulation tissue | 5 | 25 | 25 | 54 | 70 | 21 |

| Tolerability | 1 | 24 | 13 | 56 | 86 | 20 |

| No consensus following the Delphi process | ||||||

| Length of hospital stay | 3 | 19 | 30 | 58 | 67 | 23 |

| Falls | 10 | 32 | 53 | 52 | 37 | 16 |

| Cerebrovascular events | 5 | 32 | 35 | 56 | 60 | 12 |

| Requirement for social care | 4 | 50 | 28 | 42 | 68 | 8 |

| Foot fracture | 2 | 56 | 29 | 40 | 69 | 4 |

| Levels of exudate | 6 | 68 | 32 | 28 | 62 | 4 |

| Psychological impact on partner | 6 | 68 | 38 | 28 | 56 | 4 |

| Sleep disturbance | 9 | 65 | 43 | 31 | 48 | 4 |

| Foot swelling | 8 | 76 | 28 | 24 | 64 | 0 |

| Odor | 13 | 81 | 42 | 19 | 45 | 0 |

| Wound bleeding | 8 | 81 | 48 | 19 | 44 | 0 |

| Anemia | 12 | 88 | 57 | 12 | 31 | 0 |

| Respiratory complications | 13 | 88 | 58 | 12 | 30 | 0 |

| Weight loss | 16 | 96 | 64 | 4 | 20 | 0 |

| Development of cataract | 41 | 96 | 51 | 4 | 8 | 0 |

Values are presented as a proportion of respondents selecting a specific rating for each outcome given in percentages. Outcomes for potential inclusion in COS are defined as ≥70% of respondents scoring as 7–9 (critical) and 1–3 by ≤15%. Outcomes for exclusion are defined as ≥70% of respondents scoring as 1–3 (not important) and 7–9 by ≤15%. Outcomes with consensus are defined as not meeting criteria for inclusion or exclusion.

The consensus meeting participants unanimously ratified the final COS for studies assessing interventions for diabetes-related foot ulceration by the end of the meeting and agreed to include eight outcomes:

Wound healing

Time to healing

New/recurrent ulceration

Infection

Major amputation (above the ankle level)

Minor amputation (below the ankle level)

Health-related quality of life

Mortality

Conclusions

Key Findings

Using standardized, COMET methodology (10), this study established a set of eight core outcomes that should be reported in studies evaluating interventions for diabetes-related foot ulceration. The COS, which includes wound healing, time to healing, new and/or recurrent ulceration, infection, major amputation, minor amputation, health-related quality of life, and mortality, should be interpreted as the bare minimum outcome reporting standard and does not preclude measurement and reporting of additional outcomes relevant to an individual study design or population. The COS is not intended to provide guidance on how each outcome should be measured.

COS in the Context of Previous Work

IWGDF and the European Wound Management Association have previously jointly published guidance on the core planning and reporting details for studies on prevention and management of diabetic foot ulceration (7). Nonetheless, this statement was a product of expert panel discussion rather than a formal methodological approach with active patient and public involvement. Despite these differences, six of the outcomes in the COS, including wound healing, time to healing, minor amputation, major amputation, health-related quality of life, and mortality, were already recommended as the key quality measures for studies on interventions for diabetes-related foot ulceration by IWGDF and European Wound Management Association.

Ratification of the Final COS

The consensus meeting, attended by patients and international experts in diabetes-related foot disease representing the key stakeholder groups, facilitated balanced debate on the key components of the COS. The overarching aim was to create a practical COS, of similar size to that of other disciplines (17–20), which can be applied to all patients with diabetes-related foot ulceration across various health care systems globally. Despite 22 outcomes being considered as critical in the Delphi process, the final 8 included in the COS captured most of these measures, respecting the development process. Most of the deliberation during the final consensus meeting related to issues surrounding the definition and subsequent reporting of new and recurrent ulceration, subtypes of infection requiring universal reporting, measurement of quality of life, physical activity and functional status, hospitalization, revascularization, and major adverse cardiovascular events.

The consensus group acknowledged that, ideally, new and recurrent ulceration should be reported separately as outcomes. It was felt that new ulceration could be regarded as a study safety measure to determine whether a specific treatment resulted in additional wounds during the course of treatment and before the initial ulcer was healed (e.g., a foot ulcer from inappropriate casting). Recurrent ulceration, on the other hand, would potentially imply that a particular intervention may have been ineffective, but would also require longer follow-up periods. However, based on experience from previous trials using diverse methodologies and a current lack of uniform definitions (21), the experts agreed that it may be challenging to differentiate between new and recurrent ulceration. Therefore, grouping new and/or recurrent ulceration together would allow for pragmatic outcome reporting of wounds guided by the needs of the individual research team.

Following debate, osteomyelitis, despite being seen as critical by 89% of Delphi participants, was not included in the final COS. Osteomyelitis was regarded as a specific subtype of infection and could be seen as a confounder of a poor clinical outcome. Including it in the COS would also potentially result in the need for additional diagnostic tests (e.g., imaging, bone biopsy) to facilitate the diagnosis in patients with diabetes-related foot ulceration, whose clinical presentation would not necessarily have supported these tests in routine practice. Furthermore, none of the current diagnostic tests are 100% specific or sensitive in the detection of osteomyelitis (22), suggesting that such an outcome may not be reliably reported. Infection was chosen as one of the core outcomes as an umbrella term to capture all infective processes.

Pain and ambulatory status were rated as critical in the Delphi process. However, both of these outcomes are often explicitly captured or are considered to be key determinants of health-related quality of life. For example, ambulatory status (defined as level of physical activity or walking ability) is captured in most health-related quality of life questionnaires. Furthermore, pain was considered not to be universally experienced by all patients, with previous studies suggesting that it affects 21% of patients with neuropathy (23). While tolerability was felt to be important to patients, its close links to adherence with a particular intervention and potential loss to follow-up would traditionally be captured in the study’s CONSORT flowchart. Similarly, falls were found to be specific to trials assessing offloading devices rather than all interventions.

Potential reporting of hospitalization for a diabetes-related foot ulcer was noted to be challenging given the inherent difficulties in comparison of such outcomes, because of variable admission thresholds across diverse health care systems and pathways of care. It has been recognized that physicians without access to designated multidisciplinary diabetes-related foot clinics are more likely to admit patients with an ulcer compared with those practicing in specialist centers (24). Current evidence suggests a global increase in hospitalizations for diabetes-related foot complications (25). Nevertheless, there has been a shift in paradigm, with various national strategies being implemented to promote admission avoidance, such as specific guidance from the Joint British Diabetes Societies for Inpatient Care in the U.K. (26). With the shift toward community-based interventions, including utilization of outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy or hospital at-home services (27), hospitalization rates may no longer be of key significance to the population of patients with diabetes-related foot ulceration. As most diabetic foot care is delivered in community or outpatient settings, hospital admission was ultimately considered not to be a critical outcome.

Revascularization was not included in the COS as it was considered to be a form of treatment aimed at improving overall patient outcome, such as wound healing or limb salvage, rather than an outcome itself. Even though 50% of patients with diabetes-related foot ulcers have underlying peripheral artery disease, fewer than 10% require revascularization (28), reducing its applicability to all studies.

While major adverse cardiovascular events were overall seen as critical, the consensus was that they would not be relevant to all studies, particularly those looking at effectiveness of specific dressings or wound care. As a result, acute kidney injury and cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events were not included in the final COS.

Limitations

Despite three reminders being sent to the second round nonresponders, the response rate in our Delphi survey was moderate at 52%, similar to that of other studies (16). Nonetheless, relatively low response rates in the consecutive rounds are a recognized limitation of the Delphi process, particularly in surveys with a high number of items available for rating (29). Given the moderate response rate and the fact that additional outcomes were rerated as critical but none were excluded after the second round, there was no role for further rounds, in keeping with COS development in other disciplines (17,20).

Despite promoting the study with support from patient charities and approaching all suitable patients under the care of two large multidisciplinary diabetic foot networks providing at least five diabetic foot clinics a week with 12 follow-up and four new appointments daily, patient participation in the Delphi survey was relatively low. However, patients were actively engaged in all stages of the COS development. The interview phase, which included 18 patients with diverse foot complications and exposure to a range of interventions, generated eight distinct patient-specific outcomes, which were subsequently incorporated into the Delphi survey. Furthermore, the consensus meeting was attended by five patient representatives who provided crucial input into discussions shaping the final COS.

Lastly, patients with diabetes-related foot ulceration form a very heterogenous group, with variable levels of underlying neuropathy, peripheral arterial disease, and infection, ultimately resulting in dissimilar personal experiences, disease progression, and treatment plans. It was therefore understandable why the Delphi process resulted in the unexpectedly high number of critical outcomes (n = 63), which, if included, would have resulted in an impractical and undeliverable COS. This issue necessitated deviation from the standard COS development protocol, with rationalization of critical and no consensus outcomes prior to discussion in the consensus meeting, to ensure valuable and structured discussion and formalization of a feasible COS. Nonetheless, the majority of outcomes excluded by the steering group prior to the consensus meeting either were not true outcomes or were too specific to a particular subgroup of patients, already precluding their incorporation in the final COS. Despite this deviation from standard protocol, both the list of outcomes discussed in the consensus meeting and the final COS included outcomes ranked as most critical during the Delphi process. Similar issues and other forms of protocol adjustment have been noted in other COS development studies (17).

Impact and Implementation Strategy

The COS for studies evaluating interventions for diabetes-related foot ulceration will be shared with key international societies, including IWGDF and other specialist interest groups, to help increase its adoption. Previous research has demonstrated that the main reason for reduced uptake of COS is a lack of awareness of their availability (30); therefore, an effective dissemination strategy will be crucial to ensure its global implementation. Both core descriptor and core measurement sets are currently underway to standardize reporting of study participant demographics and guide how the core outcomes should be measured.

In conclusion, the proposed COS for studies evaluating treatments for diabetes-related foot ulceration was developed using robust, internationally validated COMET methodology and involved the relevant stakeholders, including people with lived experience of diabetes-related foot ulceration. Its implementation in research practice will improve the quality of evidence and, ultimately, progress in the care of an exponentially increasing population of patients.

This article contains supplementary material online at https://doi.org/10.2337/figshare.26792704.

Article Information

Acknowledgments. The authors thank Dr. Jemima Dooley (Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol) for her help in designing the topic guide for patient interviews. The authors also express our gratitude to the patient representatives Linda Brodie, Janet Harford, Brenda Riley, Sarah Parsons, and Michael Vernon for their valuable contributions to discussion during the consensus meeting.

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. G.D. and R.J.H. conceptualized the study. A.S. and G.D. completed the systematic review to facilitate the first phase of the COS development. A.S. and M.O.-G. interviewed patients and analyzed the transcripts. C.A. created patient descriptors for the outcomes in the long list. A.S. designed the Delphi survey on REDCap and provided oversight of data collection. A.S., A.J., and R.J.H. analyzed the data. A.S. drafted the manuscript. A.S., F.G., J.N., D.R., C.A., and R.J.H. formed the steering group. A.S., F.G., J.N., D.R., D.G.A., C.A., S.A.B., J.C., V.C., K.D., M.E., R.F., C.G., E.J.H., A.J., V.K., L.A.L., J.L.M., M.M.-S., E.J.G.P., J.S., J.v.N., D.K.W., and R.J.H. participated in the consensus meeting. All coauthors critically reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. R.J.H. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Handling Editors. The journal editors responsible for overseeing the review of the manuscript were Elizabeth Selvin and Rodica Pop-Busui.

References

- 1. International Diabetes Association . IDF Diabetes Atlas. 10th ed. Accessed 11 April 2024. Available from https://www.diabetesatlas.org

- 2. Khan MAB, Hashim MJ, King JK, Govender RD, Mustafa H, Al Kaabi J. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes - global burden of disease and forecasted trends. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2020;10:107–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ahmad N, Thomas GN, Gill P, Torella F. The prevalence of major lower limb amputation in the diabetic and non-diabetic population of England 2003–2013. Diab Vasc Dis Res 2016;13:348–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Armstrong DG, Boulton AJM, Bus SA. Diabetic foot ulcers and their recurrence. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2367–2375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kerr M, Barron E, Chadwick P, et al. The cost of diabetic foot ulcers and amputations to the National Health Service in England. Diabet Med 2019;36:995–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Diabetes Audit . Outcomes - England and Wales. Accessed 11 March 2024. Available from https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiYTdiNDI5NjgtNWI2Ny00ZGQwLWI5MDgtZDIyOTE3ZmQ4ZDdiIiwidCI6IjM3YzM1NGIyLTg1YjAtNDdmNS1iMjIyLTA3YjQ4ZDc3NGVlMyJ9

- 7. Jeffcoate WJ, Bus SA, Game FL, et al.; International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot and the European Wound Management Association . Reporting standards of studies and papers on the prevention and management of foot ulcers in diabetes: required details and markers of good quality. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016;4:781–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dovell G, Staniszewska A, Ramirez J, et al. A systematic review of outcome reporting for interventions to treat people with diabetic foot ulceration. Diabet Med 2021;38:e14664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Williamson PR, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, et al. Developing core outcome sets for clinical trials: issues to consider. Trials 2012;13:132–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Williamson PR, Altman DG, Bagley H, et al. The COMET handbook: version 1.0. Trials 2017;18(Suppl 3):280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kearney A, Gargon E, Mitchell JW, et al. A systematic review of studies reporting the development of core outcome sets for use in routine care. J Clin Epidemiol 2023;158:34–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hughes KL, Clarke M, Williamson PR. A systematic review finds Core Outcome Set uptake varies widely across different areas of health. J Clin Epidemiol 2021;129:114–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dovell G, Hinchliffe RJ. Development of a core outcome set for diabetic foot ulceration, 2018. Accessed 30 May 2024. Available from https://www.comet-initiative.org/Studies/Details/1138

- 14. Kirkham JJ, Gorst S, Altman DG, et al. Core Outcome Set-STAndards for Reporting: The COS-STAR statement. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van Tol RR, Kimman ML, Melenhorst J, Stassen LPS, Dirksen CD, Breukink SO, Members of the Steering Group . European Society of Coloproctology Core Outcome Set for haemorrhoidal disease: an international Delphi study among healthcare professionals. Colorectal Dis 2019. May;21:570–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Avery KNL, Chalmers KA, Brookes ST, et al.; CONSENSUS Esophageal Cancer Working Group . Development of a core outcome set for clinical effectiveness trials in esophageal cancer resection surgery. Ann Surg 2018;267:700–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Byrne M, O’Connell A, Egan AM, et al. A core outcomes set for clinical trials of interventions for young adults with type 1 diabetes: an international, multi-perspective Delphi consensus study. Trials 2017;18:602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Innes K, Hudson J, Banister K, et al. Core outcome set for symptomatic uncomplicated gallstone disease. Br J Surg 2022;109:539–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Potter S, Holcombe C, Ward JA, Blazeby JM, BRAVO Steering Group . Development of a core outcome set for research and audit studies in reconstructive breast surgery. Br J Surg 2015;102:1360–1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Netten JJ, Bus SA, Apelqvist J, et al.; International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot . Definitions and criteria for diabetes-related foot disease (IWGDF 2023 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2023;40:e3654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pineda C, Espinosa R, Pena A. Radiographic imaging in osteomyelitis: the role of plain radiography, computed tomography, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, and scintigraphy. Semin Plast Surg 2009;23:80–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Abbott CA, Malik RA, van Ross ERE, Kulkarni J, Boulton AJM. Prevalence and characteristics of painful diabetic neuropathy in a large community-based diabetic population in the U.K. Diabetes Care 2011;34:2220–2224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jude EB, Oyibo SO, Millichip MM, Boulton AJM. A survey of physicians' involvement in the management of diabetic foot ulcers in secondary health care. Pract Diab Int 2003;20:89–92 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lazzarini PA, Cramb SM, Golledge J, Morton JI, Magliano DJ, Van Netten JJ. Global trends in the incidence of hospital admissions for diabetes-related foot disease and amputations: a review of national rates in the 21st century. Diabetologia 2023;66:267–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Joint British Diabetes Societies for Inpatient Care . Admissions avoidance and diabetes: guidance for clinical commissioning groups and clinical teams, 2013. Accessed 12 February 2024. Available from https://abcd.care/sites/default/files/site_uploads/JBDS_Guidelines_Current/JBDS_07_IP_Admissions_Avoidance_Diabetes.pdf

- 27. Lyhne CN, Bjerrum M, Riis AH, Jørgensen MJ. Interventions to prevent potentially avoidable hospitalizations: a mixed methods systematic review. Front Public Health 2022;10:898359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Skrepnek GH, Armstrong DG, Mills JL. Open bypass and endovascular procedures among diabetic foot ulcer cases in the United States from 2001 to 2010. J Vasc Surg 2014;60:1255–1265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gargon E, Crew R, Burnside G, Williamson PR. Higher number of items associated with significantly lower response rates in COS Delphi surveys. J Clin Epidemiol 2019;108:110–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fletcher J, Sheehan KJ, Smith TO. Barriers to uptake of the hip fracture core outcome set: an international survey of 80 hip fracture trialists. Clin Trials 2020;17:712–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]