Abstract

Salmonella enterica, a prominent foodborne pathogen, contributes significantly to global foodborne illnesses annually. This species exhibits significant genetic diversity, potentially impacting its infectivity, disease severity, and antimicrobial resistance. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) offers comprehensive genetic insights that can be utilized for virulence assessment. However, existing bioinformatic tools for studying Salmonella virulence have notable limitations. To address this gap, a Salmonella Virulence Database with a non-redundant, comprehensive list of putative virulence factors was constructed. Two bioinformatic analysis tools, Virulence Factor Profile Assessment and Virulence Factor Profile Comparison tools, were developed. The former provides data on similarity to the reference genes, e-value, and bite score, while the latter assesses the presence/absence of virulence genes in Salmonella isolates and facilitates comparison of virulence profiles across multiple sequences. To validate the database and associated bioinformatic tools, WGS data from 43,853 Salmonella isolates spanning 14 serovars was extracted from GenBank, and WGS data previously generated in our lab was used. Overall, the Salmonella Virulence database and our bioinformatic tools effectively facilitated virulence assessment, enhancing our understanding of virulence profiles among Salmonella isolates and serovars. The public availability of these resources will empower researchers to assess Salmonella virulence comprehensively, which could inform strategies for pathogen control and risk evaluations associated with human illnesses.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-74124-x.

Keywords: Salmonella, Virulence genes, Database, WGS analyses tools

Subject terms: Computational biology and bioinformatics, Microbiology

Introduction

As one of the major foodborne pathogens, Salmonella entericacauses about 1.35 million infections, leading to 26,500 hospitalizations and 420 deaths each year in the United States alone1. Currently, S. enterica encompasses more than 2,600 serovars that differ from each other in the polysaccharide portion of the lipopolysaccharide layer (O antigen) and/or the filamentous portion of the flagella (H antigen) present on the surface of Salmonella2. Different S. entericaserovars display variations in their pathogenicity, virulence, and susceptibility to antimicrobial treatment. While many serovars may be capable of causing infections in humans and animals, only a limited number of serovars cause most human infections3. Some S. entericaserovars are host-restricted and can only infect certain hosts, while others infect a wide range of hosts. Also, they vary considerably in the nature of the disease that they cause. Some serovars are more likely to cause invasive disease in humans, and some only cause mild gastroenteritis. These distinctions in disease severity may arise from the considerable genetic diversity observed in the virulence factors (VFs), which are molecules produced by microbial pathogens that allow them to overcome host defense mechanisms and cause disease in a host4. The difference in VFs among the serovars within Salmonellamay impact their likelihood to cause more severe disease5.

Antimicrobial therapy is often required for the more severe cases of illnesses caused by Salmonellainfection6. Therefore, the occurrence and spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) causes many concerns for making regulatory decisions related to antimicrobial use in food animals a continuing public health concern. Severe, often invasive, cases of Salmonellaare typically associated with increased virulence of the infecting strain, which illustrates the important confluence of virulence and AMR7,8. Mechanisms for the spread of antimicrobial resistance characteristics among pathogens include both horizontal and vertical genetic transfer. Key components of horizontal gene transfer are plasmids, which are circular DNA elements that replicate independently from the chromosome and can acquire and exchange genes with the chromosome and other host-resident plasmids9. Like AMR genes, VFs can also be spread through horizontal and vertical genetic mechanisms to increase the likelihood that pathogens, such as Salmonella, develop an increased ability to colonize hosts and avoid immune system clearance while at the same time becoming resistant to antimicrobial treatment10.

Recent advancements in DNA sequencing have revolutionized our understanding of virulence and AMR in enteric pathogens, like Salmonella, offering profound implications for public health improvement. As DNA sequencing has become less expensive and more accessible, it has greatly accelerated biological and medical research and discovery. Whole genome sequencing (WGS), which can reveal the complete DNA make-up of an organism and facilitate the detection of variations both within and between species, has been widely used by public health and food regulatory agencies to expedite the detection and identification of bacteria isolated from food and/or environmental samples during foodborne disease outbreaks11. However, effective analyses of WGS data necessitates robust bioinformatics tools. Consequently, bioinformatics approaches are increasingly pivotal in exploring AMR and virulence in foodborne pathogens, including Salmonella. Despite the progress, existing tools for studying Salmonella virulence exhibit limitations in usability and result provision, hindering their efficacy in addressing public health inquires; thus, there is a pressing need to develop improved tools to enhance the assessment of potential virulence-associated factors. Several VF databases have been developed for enteric organisms, such as the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC; formally Pathosystems Resource Integration Center (PATRIC)), which curated Salmonella VFs based on WGS data, the Virulence Factor Database (VFDB), and Victors, which have curated large numbers of Salmonella VFs based on WGS data (over 4,000,000 SalmonellaVF genes cataloged from over 5,000 genomes)12,13. While these sources offer vast amounts of data, the presence of redundant genes complicates navigation and use for virulence assessment. In addition, these databases lack comprehensiveness in some cases, as several VFs, including many that are encoded on plasmids, are not represented. To fully utilize the wealth of information provided by WGS data and accurately evaluate the virulence of Salmonella isolates, there was a need to develop an improved Salmonella database. Such a database should feature a non-redundant, comprehensive compilation of putative VFs from Salmonella, empowering more effective risk assessment.

In this study, a comprehensive Salmonella virulence database that contained virulence and putative VFs from both Salmonella genomic DNA and plasmids was developed. Additionally, computational tools that were devised for identifying virulence genes in Salmonella strains and comparing virulence gene profiles among different isolates were incorporated into the database. To validate the efficacy of the database and the tools, the WGS data from 43,853 Salmonella strains spanning 14 different key serovars were downloaded from NCBI and analyzed. The predicted virulence profiles formatted as binary data were further analyzed using BioNumerics (ver. 7.6; Applied Maths, Austin, TX) and Pandas (Python Data Analysis Library). Our results show that this newly developed database offers a valuable resource for the scientific community for rapid strain characterization and can assist in tracing the sources of pathogens based on their virulence profiles. The variations in VF profiles of different strains and serovars is also crucial for developing effective strategies for disease prevention, management, and treatment.

Methods

Generation of a non-redundant, comprehensive list of virulence factors from Salmonella

The generation of a non-redundant, comprehensive list of VFs from Salmonellaemployed two steps. In the first step, a list of putative virulence genes was generated based on the existing available datasets. Currently, there are several VF databases for enteric organisms, including PATRIC (now BV-BRC)12, VFDB14, and Victors4, that provided baseline virulence gene data for organisms such as S. enterica, Escherichia coli, Shigella, and other enteric pathogens. In the second step, additional Salmonella-associated VFs and other putative VFs, which are not represented in these databases, were identified through an extensive literature review15. In the initial phase of database development, S. Typhimurium LT2 was used as the reference genome for those VFs present in the strain. Additional genes, not in LT2, were subsequently added to the cumulative list, and their reference strain was provided in the database.

Development of comprehensive Salmonella virulence gene databases

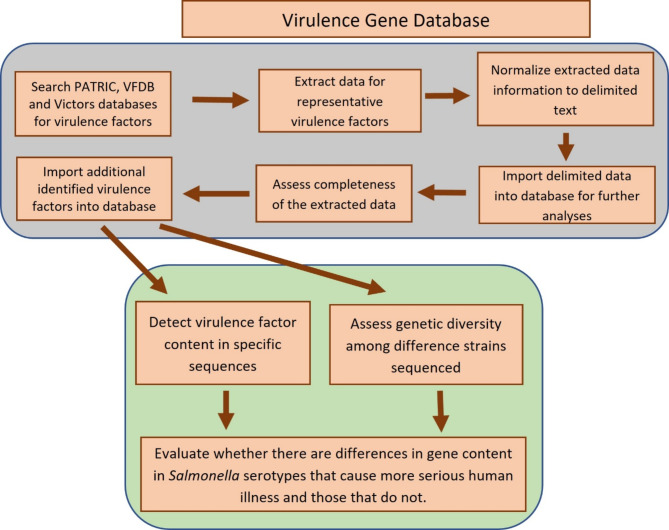

The gene-level sequence data and other related information (protein sequence, product, etc.) of these genes were extracted from GenBank using a customized Python and Biopython program. The extracted data were normalized, a process of organizing the extracted DNA sequence data to ensure their consistency, reduce redundancy, and improve data integrity, then converted to a delimited form and imported into a PostgreSQL relational database. The completeness of the extracted data was regularly evaluated through ongoing literature review and the information on the additional identified virulence factors were subsequently imported into our database. The scheme used to develop the virulence gene database and downstream applications of the database are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The scheme that was used to develop the virulence gene database and downstream application of the database.

Bioinformatics analysis tools development

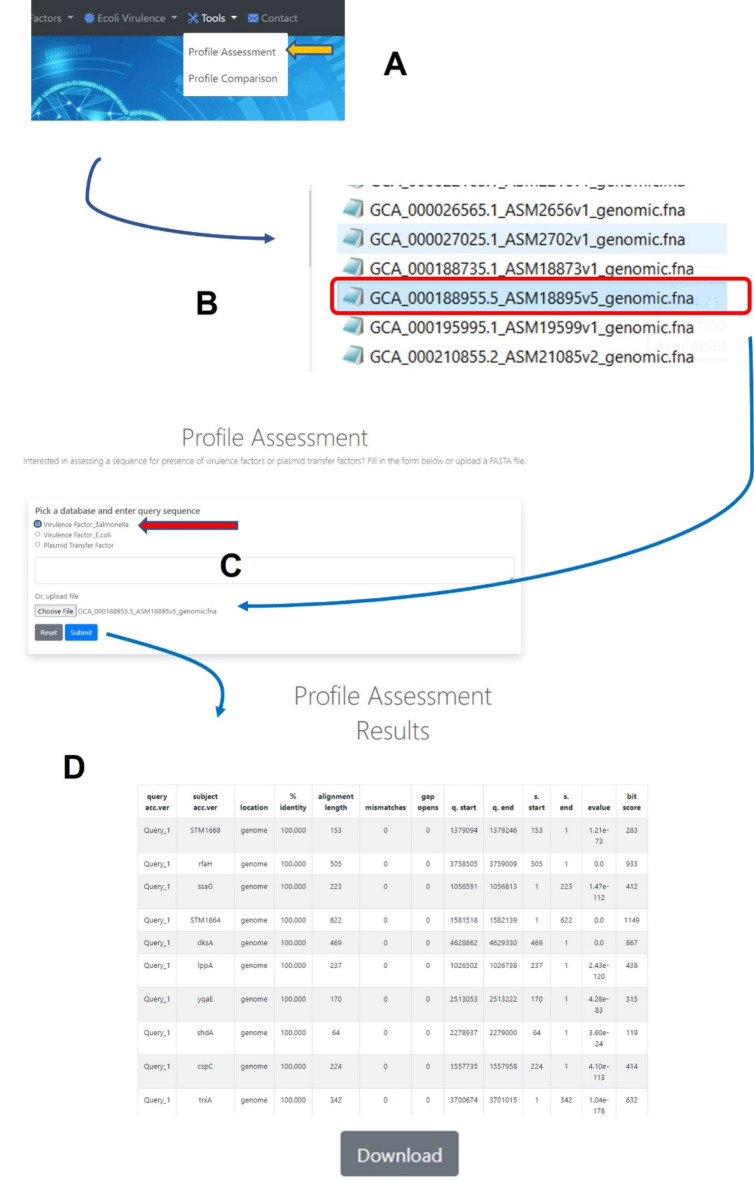

Two distinct bioinformatics analysis tools were developed in this study. The first tool, termed “Profile Assessment” employs matching algorithms based on the BLAST algorithm to predict the presence of virulence genes in sequence strains. Users can copy/paste the sequence directly into a text box or input a single FASTA nucleotide file. Upon submission, the sequence is compared to the virulence gene sequences in the Salmonella VF database, and a detail table containing information on the identified virulence genes, including the % identity to the reference sequence, number of mismatched base pairs, e-value, and bit score, is generated (Fig. 2). A cutoff e-value of 10−3 is utilized, aligning with the threshold used in NCBI BLAST searching (https://biopython.org/docs/1.76/api/Bio.Blast.Applications.html). The genes with an e-value less than 10−3 indicate their predicted presence in the WGS and are included in the assessment result.

Fig. 2.

The analyses processes of the tool “Salmonella Virulence Factor Assessment” (A-C) and the output after the analysis (D). To start the analysis, “Profile Assessment” tab (A) is clicked, then a single sequence (FASTA) file of the isolate is selected (B) and “Virulence Factor_ Salmonella” (indicated by the red arrow) is picked. Then the sequence uploaded into system and a BLAST-based analyses is conducted. When a gene is identified information related to identity to reference, locations, etc. are provided for all the genes present (D). A download button is provided at the bottom of the output to facilitate further analyses in different programs.

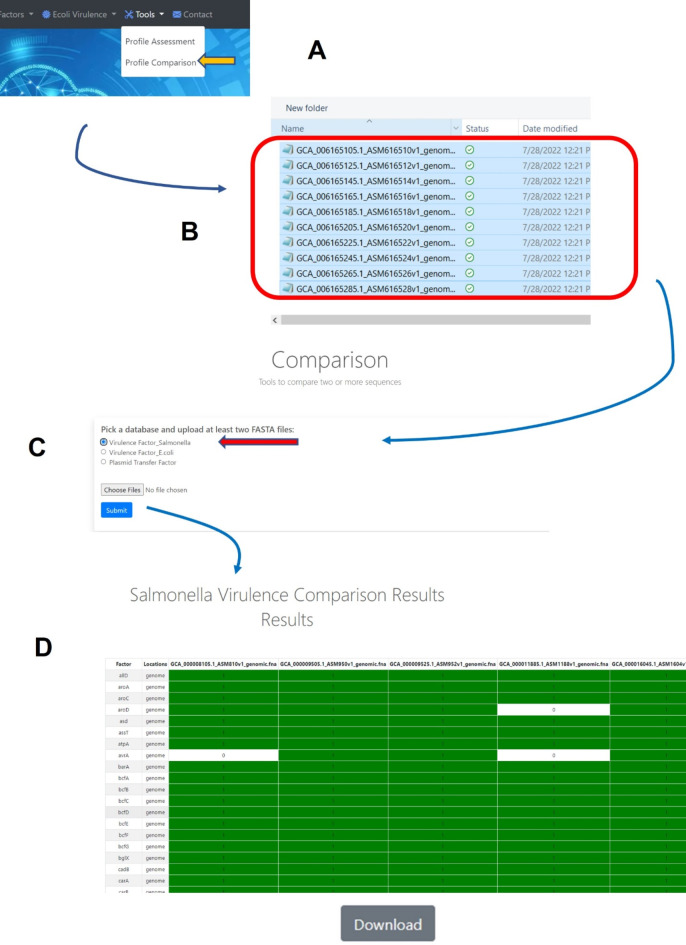

The second tool, named “Profile Comparison” was developed and can be used for comparative analyses of the virulence gene profiles among different strains. Users upload multiple FASTA-formatted sequence files simultaneously, which are then compared to the gene sequences in the VF database (Fig. 3). Similar to the VF Profile Assessment tool, genes are considered present if they meet the BLAST e-value cutoff of 10−3. The output of the comparison is a binary matrix indicating the presence or absence of the transfer genes in the sequences. The matrix can be viewed in the database window or downloaded from the database as a delimited file for further analysis.

Fig. 3.

The analyses processes of the tool “Virulence Factor Comparison” (A-C) and the output after the analysis (D). To start the analyses, “Profile Comparison” tab (A) is clicked, then multiple sequence (FASTA) files of interest are selected for uploading (B) and “Virulence Factor_ Salmonella” (indicated by the red arrow) is selected to upload the sequences into system (C) and a BLAST-based analyses is conducted to identify the predicted genes present. When genes are detected a resulting presence/absence matrix is generated to facilitate comparison among strains (D). These analyses can be downloaded as a tab-delineated file using the download button and extracted for further phylogenetic analyses.

Assessment of the virulence database and analysis tools

To evaluate the virulence database and the functionality of the developed tools, WGS data from 43,853 Salmonella isolates from 14 different serovars (Table 1 and Supplemental Table 1), the most commonly identified serovars in human, animals and foods, that were released from 1980 (the earliest time of data available) until 2022 were downloaded from NCBI.

Table 1.

Information on genomic sequences downloaded from NCBI for analyses of database and tools.

| Taxon | Serotype | Number of Sequences | Assembly level* | Year released |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 58,095 | Agona | 3012 | 1,2,3,4 | 1980–2022 |

| 98,360 | Dublin | 2571 | 1,2,3,4 | 1980–2022 |

| 149,539 | Enteritidis | 692 | 2,3,4 | 1980–2022 |

| 149,385 | Hadar | 1505 | 1,2,3,4 | 1980–2022 |

| 611 | Heidelberg | 4502 | 1,2,3,4 | 1980–2022 |

| 440,524 | I,4,[5],12:i:- | 3889 | 1,2,3,4 | 1980–2022 |

| 286,783 | Indiana | 882 | 1,2,3,4 | 1980–2022 |

| 595 | Infantis | 11,821 | 1,2,3,4 | 1980–2022 |

| 363,569 | Javiana | 1595 | 1,2,3,4 | 1980–2022 |

| 108,619 | Newport | 6552 | 1,2,3,4 | 1980–2022 |

| 90,105 | Saintpaul | 2144 | 1,2,3,4 | 1980–2022 |

| 340,190 | Schwarzengrund | 2071 | 1,2,3,4 | 1980–2022 |

| 90,370 | Typhi | 1536 | 2,3,4 | 1980–2022 |

| 90,371 | Typhimurium | 1081 | 2,3,4 | 1980–2022 |

| Total: | 43,853 |

Notes: 1980 is the earliest date that sequences were available.

*Sequence assembly level: 1-contig; 2-scaffold; 3-chromosome; 4-completed.

For serovars of Typhimurium, Enteritidis, and Typhi, only the WGS of the sequence assembly levels 2–4 (i.e., scaffold, chromosome, and completed) were downloaded due to the large volume of available data, while all available sequence (levels 1–4, which also include contigs) were used for other serovars. For the evaluation of the Salmonella VF Profile Assessment tool, a random subset of WGS data from 810 strains was analyzed. The resultant percent identity to the reference gene sequences was extracted and merged with the results for the other strains for comparative analyses. For the SalmonellaVF Comparison tool, the predicted virulence gene information was extracted from the database and transformed to binary data, with “1” indicating the presence of the gene and “0” indicating the absence of the gene. A random subset of 481 WGS were resampled and analyzed to confirm the detection of gene calls. The predicted virulence profiles (percent identity to reference for the assessment tool data or binary results for the comparison tool data) were further analyzed using BioNumerics (ver. 7.6; Applied Maths, Austin, TX) for Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and minimal spanning tree (MST) analyses to compare the similarity of the VF profiles within and among serovars. Additionally, Pandas (Python Data Analysis Library)16 was employed to identify the predominant VF profiles within each serovar, i.e., the genes that are present or absent in all the isolates of each serovar. From these results, one isolate representing the predominant VF profile in each serovar was chosen to create a dendrogram using BioNumerics to display the relatedness of their virulence profiles.

Results

Reference gene catalog composition, database construction, and analysis tools development

Based on the function of the genes from published literature15,17–20, a total of 594 VFs or putative VFs, including at least 150 located on a Salmonella Pathogenicity Island (SPI), 19 on Salmonella genomic island 1 (SGI) and at least 20 associated with plasmids from various Salmonella, were cataloged. The genes that encode these VFs were utilized to build the backbone of the Salmonella VF Database (Supplemental Table 2). As the field of Salmonella virulence research advances, ongoing efforts will be periodically assessed to evaluate and update the database with newly identified virulence genes. Figure 1 provides an overview of the workflow involved in this process. To effectively utilize the curated data from the initial phase of the study, the two distinct tools were developed to analyze WGS data. The Salmonella VF Profile Assessment tool is depicted in Fig. 2 and can be used to provide a detailed characterization of the virulence genes present in a sequenced strain. The Salmonella VF Profile Comparison tool (Fig. 3), facilitates simultaneous comparison of multiple FASTA files, generating a presence/absence matrix for comprehensive virulence gene profile comparisons among various Salmonella isolates.

To enhance user accessibility, a user-friendly website hosting the Salmonella VF gene data and analysis tools was built using Django v2.2 and running on Apache HTTP Server v2.4.37. The database and tools described above are publicly accessible at https://virulence.fda.gov and are freely available to the scientific community for identifying Salmonella VFs. Additionally, the database includes modules for assessing plasmid transfer genes and putative Escherichia coli VFs21. Notably, draft versions of the Salmonellavirulence database have already contributed to published studies22,23.

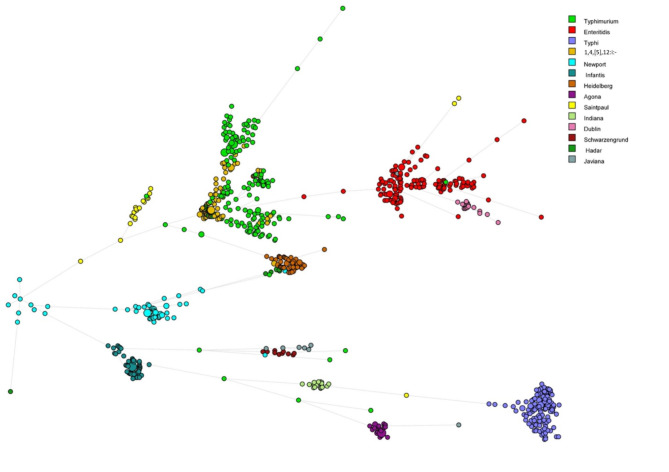

Evaluation of the Salmonella virulence factor assessment tool

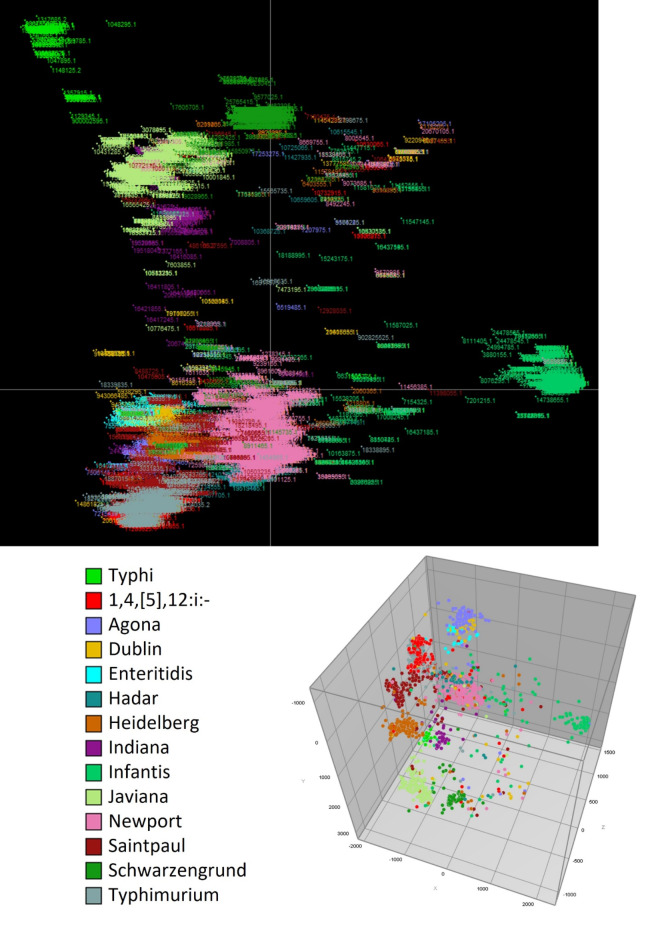

The Salmonella VF Profile Assessment tool, featured in Fig. 2, provided a detailed assessment of the putative VF genes present in the analyzed FASTA file, delivering detailed information on the identified genes and their percent identity to the reference strains. The BLAST-generated output for the 810 strains analyzed, including the calculated percent identity for each detected gene, is shown in Supplemental Table 3. These data were compared across strains to assess the virulence gene similarity profiles among multiple Salmonella strains. The data imported into BioNumerics and MST were calculated based on the percent identity of the genes present compared to their references, with the samples denoted by serovar (Fig. 4). The results show that there is a general clustering based on serovars, with notable overlap between serovars Typhimurium and I,4,[5],12:i:-, which are known to be genetically closely related24. As the monophasic variant of S. Typhimurium, I,4,[5],12:i:- is closely related to S. Typhimurium both antigenically and genetically25. The key difference between them is that I,4,[5],12:i:- lacks the fljB gene, while the biphasic S. Typhimurium expresses two flagellar antigens: fljC (phase-1 flagellin) and fljB(phase-2 flagellin)25. In addition, serovars Enteritidis and Dublin exhibited close alignment and share similar antigenic profiles with one another.

Fig. 4.

Minimal spanning tree of 810 strains randomly selected from one the 14 serovars. The minimal spanning tree was calculated based on the percent identity of the virulence factors to the references with the samples denoted by serovars.

Evaluation of the Salmonella virulence factor comparison tool

The Salmonella VF Comparison tool, highlighted in Fig. 3, can generate a matrix indicating the presence or absence of genes in the database, which facilitates the simultaneous comparison of multiple FASTA files, enabling the comparison of VF profiles across diverse Salmonella strains from various serovars. Utilizing this tool, sequences from the 43,853 Salmonella strains (GenBank accession numbers provided in Supplemental Table 1) were analyzed to predict the presence/absence of the 594 VFs. The resulting binary data for the VF profiles was downloaded from the database and saved in an Excel format. When the subset of genes was resampled, the data matched the original calls. Subsequently, the presence rate of each gene in each serovar was calculated and summarized in Supplemental Table 4. Employing Pandas, the binary comparison data was further analyzed to identify the predominant virulence profile in each serovar. Table 2 presents number of the isolates with the predominant virulence profile along with their percentage within the serovar. The results revealed notable findings regarding the variations of VF profiles across different serovars. For instance, most of the S. Infantis isolates share the same VF profiles (86.47%, 9,637 out of 11,145) (Table 2). While in S. Newport and S. Saintpaul, the most common virulence profiles are only shared by 15.87% (1,039 out of 6,545) and 15.24% (327 out of 2,146) of the isolates, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

The number of the isolates with the predominate virulence profile in each serotypes.

| Serotype | Total # of isolates | Number of isolates with predominate virulence profile | Percent of total isolates | Representative isolate with the predominate virulence profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agona | 3012 | 1729 | 57.40 | GCA_007370785.1 |

| Dublin | 2571 | 1875 | 72.93 | GCA_011286465.1 |

| Enteritidis | 692 | 323 | 46.68 | GCF_002037995.1 |

| Hadar | 1505 | 1036 | 68.84 | GCA_010737855.1 |

| Heidelberg | 4502 | 2955 | 65.64 | GCA_007013425.1 |

| I,4,[5],12:i:- | 3889 | 1728 | 44.43 | GCA_010399885.1 |

| Indiana | 882 | 662 | 75.06 | GCA_024419575.1 |

| Infantis | 11,821 | 9637 | 81.52 | GCA_006683165.1 |

| Javiana | 1595 | 474 | 29.72 | GCA_010685105.1 |

| Newport | 6552 | 1039 | 15.86 | GCA_011528265.1 |

| Saintpaul | 2144 | 327 | 15.25 | GCA_010461045.1 |

| Schwarz | 2071 | 479 | 23.13 | GCA_008642875.1 |

| Typhi | 1536 | 1173 | 76.37 | GCA_003719235.1 |

| Typhimurium | 1081 | 301 | 27.84 | GCA_001154285.1 |

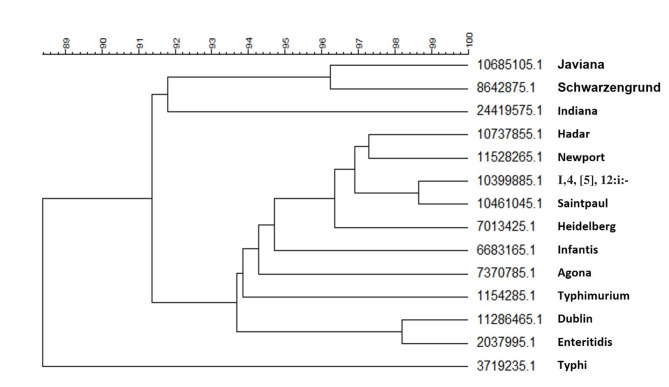

The data were further analyzed using BioNumerics with PCA. The resultant PCA showed that the isolates of the same serovars are mostly clustered together (Fig. 5). Based on their clinical presentation and host specificity, Salmonellais broadly categorized into two groups: typhoidal and non-typhoidal15. As the only typhoidal serovar analyzed, S. Typhi isolates are separated from the other nontyphoidal serovars (NTS). The typhoidal serovars also include Paratyphi A, B, or C that are most associated with causing typhoid or paratyphoid fevers. The NTS, including the other 13 serovars in this study, include the majority of the Salmonella serovars associated with foodborne infections. The result of the phylogenetic analysis of the most common virulence profile from each serovar shows that S. Typhi has less than 90% similarity with the isolates from the 13 NTS (Fig. 6). One of the main differences between S. Typhi and the NTS is the presence of the 28 genes (stgABD, STY_RS18755, tviABCDE, vexABCDE, and pilLMNaNbOPQRSTUVV2) in S.Typhi that are mainly associated with SPI-7, one of the SPIs that is particularly notable for its role in the virulence of typhoidal serovars15,26. These genes were detected in the majority (more than 97%) of the S. Typhi isolates examined. Conversely, the presence of these genes in the other 13 serovars is less than 5% (Supplemental Table 4) (Table 3).

Fig. 5.

Principal component analysis (PCA) results of all the 43,853 isolates based on their VFs. The resultant PCA showed that the isolates of the same serovars are mostly clustered together, which indicates that the similarity of the VF profiles within the same serovars and diversity of the VF profiles among several of the different serovars.

Fig. 6.

Phylogenetic tree of the predominate isolate from each serovar.

Table 3.

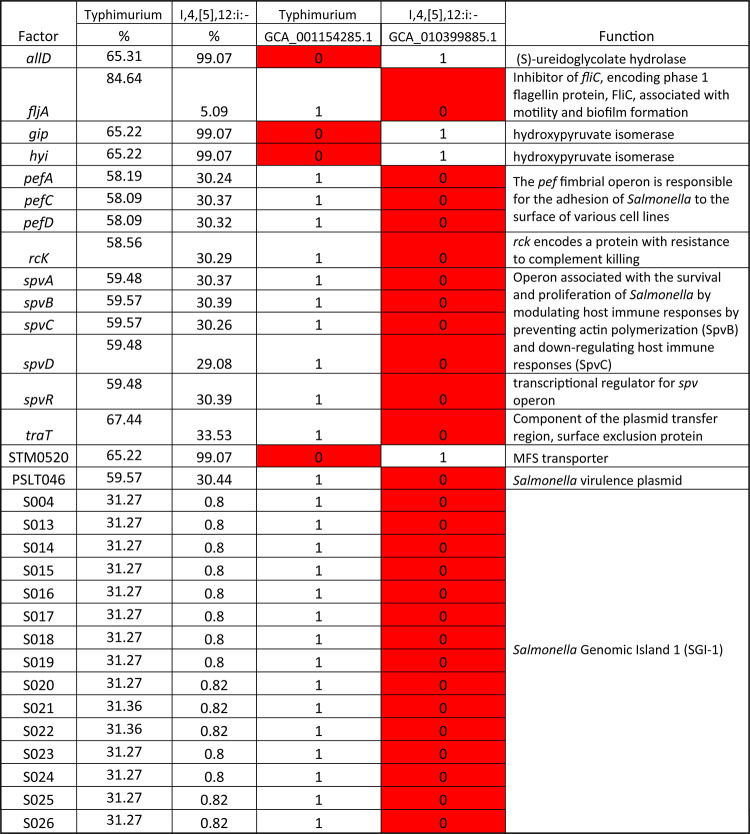

The genes with difference presence rate in serotypes Typhimurium and I,4,[5],12:i:-.

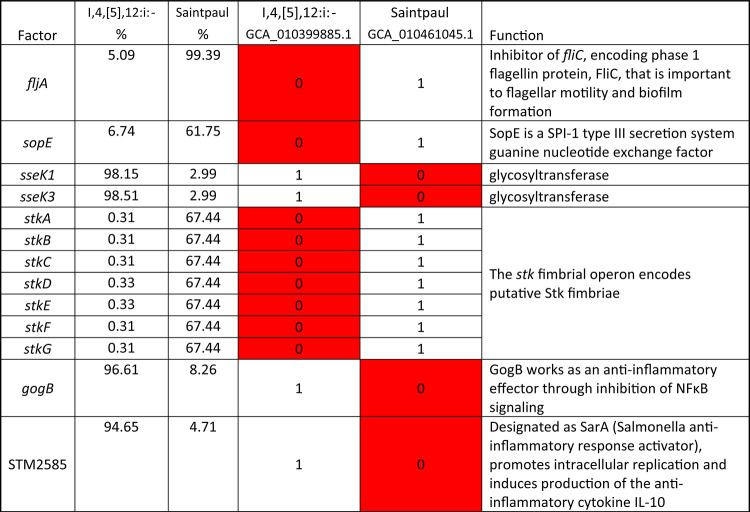

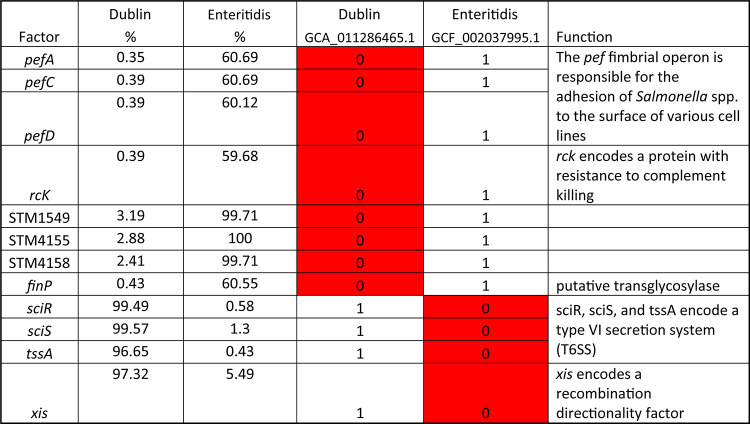

The PCA results showed that the isolates from S. I,4,[5],12:i:- overlapped extensively with the isolates from S. Typhimurium (Fig. 5), further confirming they are closely related. However, the phylogenetic analysis results showed the similarity between the predominant virulence profiles of these two serovars is only around 93.4% (Fig. 6). From the results of the phylogenetic analysis shown in Fig. 6, the predominant virulence profile of S. I,4,[5],12:i:- is also closely related to that of S. Saintpaul, with only 13 genes difference between their predominant VF genotypes (Table 4). Some key differences include the presence of the Stk fimbrial operon in S. Saintpaul and the gogA and sseK genes in S. I,4,[5],12:i:-. The VF profiles of isolates from serovars S. Enteritidis and S. Dublin are also similar based on the PCA and phylogenetic analysis, results with about 97.5% similarity (Fig. 6). The main differences are twelve genes, including plasmid encoded fimbriae (pefACD) and rck in S. Enteritidis and type VI secretion system (T6SS) genes (sciRS and tssA) common to S. Dublin, as shown in Table 5.

Table 4.

The genes with difference presence rate in serotypes I,4,[5],12:i:- and Saintpaul.

Table 5.

The genes with difference presence rate in serotypes Dublin and Enteritidis.

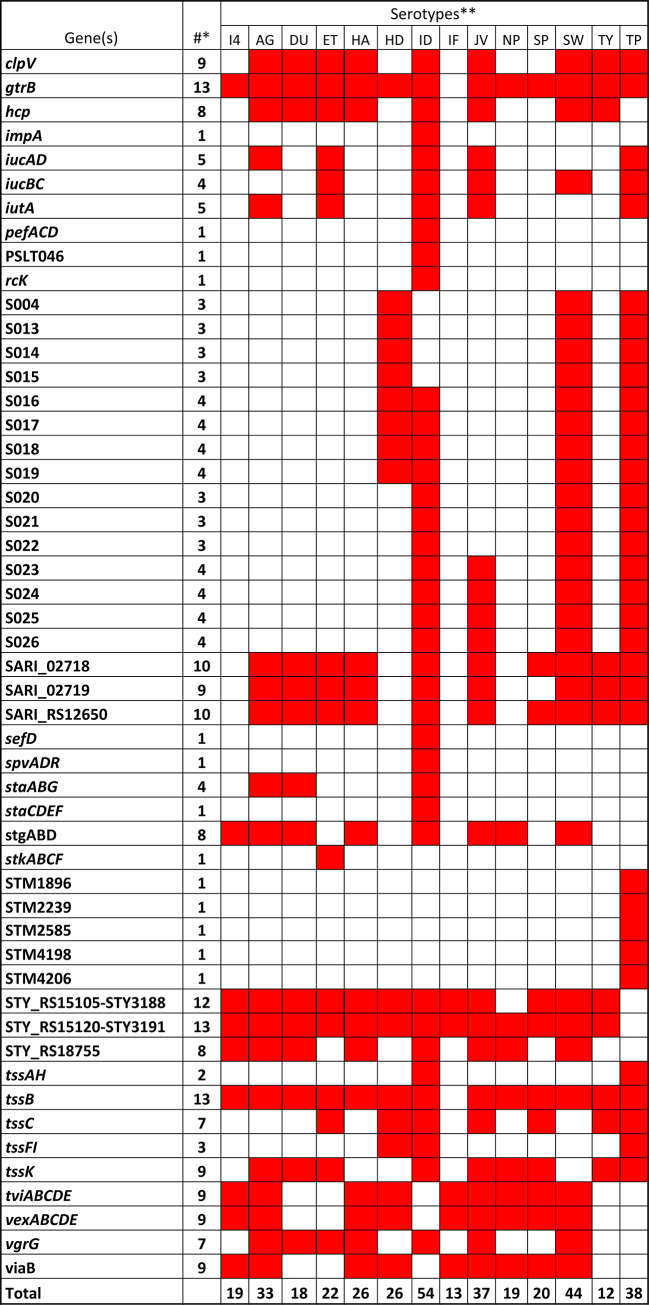

The binary comparison data of the comprehensive virulence gene profiles were also analyzed using Panda to identify the virulence genes that are present or absent in all the isolates of each serovar. The present analyses show that among the 594 virulence genes deposited in the VF database, 413 genes exist in all the isolates of at least one of the serovars. Nine of these genes (pflB, narG, dsbB, slyD, citC, cpxR, focA, cspE, and cpxA) were present in all the isolates analyzed, while 26 and 46 genes were found in all the isolates of 13 and 12 serovars, respectively (Supplemental Table 5). Additionally, there were 36 genes that were present in all the isolates of one particular serovar, but were detected much less frequently in other serovars. When looking at those genes absent in a particular serovar, there were 78 that were missing from all the isolates in at least one of the 14 serovars (Table 6). Isolates from S. Indiana were missing most of these genes, as it had 54 VFs absent from all the isolates analyzed from the serovar. All isolates of S. Schwarzengrund, S. Typhi, and S. Agona lacked 44, 38, and 33 of the VF genes, respectively. Conversely, S. Typhimurium and S. Infantis were the two serovars with the most virulence genes in any of the isolates, with only 12 and 13 genes missing, respectively.

Table 6.

Genes that are missing in all the isolates analyzed in the serotypes. *The number of serotypes missing the genes. **Abbreviation for serotypes: I,4,[5],12:i:-; AG-Agona; DU-Dublin; ET-Dublin; HA-Hadar; HD-Heidelberg; ID-Indiana; IF-Infantis; JV-Javiana; NP-Newport; SP-Saintpaul; SW-Schwarzengrund; TY-Typhimurium; TP-Typhi. ***Genes that are missing are highlighted in red color.

Discussion

Not all the existing 2,600 Salmonella serovars exhibit equal pathogenicity to humans. Specific serovars or strains of Salmonella, especially those in subspecies enterica, are more apt to cause invasive infections in both humans and/or animals27. This feature suggests that these isolates may harbor specific VFs crucial for infection. In this project, WGS data from S. Typhi and 13 different NTS ranging from common causes of human illness (e.g. Enteritidis, Typhimurium and Newport) to thus less common (e.g. Schwarzengrund and Indiana) were analyzed using a database with a non-redundant, comprehensive list of Salmonella VFs and accompanying tools known as VF Profile Assessment and VF Profile Comparison tools. The database was created by compiling existing datasets and conducting an extensive literature review to account for those that were not represented in these databases. The current version of the database contains 594 VFs or putative VFs, including approximately 157 predicted to be located in an SPI-19 on SGI-1 and 21 that commonly located on plasmids (Supplemental Table 3). Some of these plasmid-associated genes, such as the sitoperon, can also be located in the chromosome. Among the SPIs, genes from all 24 currently identified SPIs are included and more details about their functions was recently reviewed15. To establish the Virulence and Plasmid Transfer Factor Database to facilitate the prediction of virulence genes, the nucleotide and amino acid sequences of reference genes, and other related information such as the predicted product, locus tag, and accession numbers, were extracted from GenBank to create the backend reference VF dataset accessed by the analysis tools.

The VF Profile Assessment tool was developed to facilitate the prediction of the presence of VFs in an uploaded sequence and provide detailed information on the nucleotide percent identity and matching location to the reference virulence genes in the database. The results of this tool can be viewed in the program online and/or downloaded and exported into a spreadsheet to facilitate further data analysis. To evaluate the utility of the tool, WGS data from 810 strains from 14 different serovars were combined and analyzed using Profile Assessment tool (Supplemental Table 3). An observed sequence diversity among individual virulence genes present in strains/serovars could offer valuable insights into their effects on host and/or tissue specificity, gene expression, and other related factors. For example, differences in the percent identities to reference genes among the various fimbrial gene (e.g., bcfoperon, Supplemental Table 3) across different serovars may influence their tropism to interact with host epithelial cells28. The fimbriae can play key roles in adhesion to host tissues. With the capability of preferential binding to various glycans, fimbriae enhance Salmonella’sability to adhere to different host cell surfaces, whether within the same host (tissue tropism) or across different hosts (host tropism), aiding in the colonization and infection process28,29. Figure 4 clearly showed that many VF similarity profiles within specific serovars cluster closely together while remaining distinct from those of other serovars. The pattern of serovar dispersion is similar to what is observed when examining the presence or absence of genes but reveals a greater diversity of genotypes. These data highlight that beyond simply identifying the presence or absence of particular VFs, understanding genetic diversity is crucial in shaping the pathogenicity and virulence of Salmonella strains.

The VF Profile Comparison tool allows users to upload multiple sequence files at once, which facilitated the comparison of multiple sequences simultaneously. The results display a binary matrix output indicating the presence or absence of VF genes across the uploaded sequences. The resultant comparison data can be visualized online in the program window or downloaded for further analyzed using other software programs. In this current assessment, WGS data of 43,853 Salmonella isolates from 14 different serovars were analyzed, extracted and collated in a spreadsheet and uploaded into BioNumerics for further analyses. The resulting PCA output demonstrated that isolates belonging to the same serovars predominantly clustered together (Fig. 5), suggesting a high degree of similarity in VF profiles within individual serovars and but diversity between the different serovars, with some exceptions noted above. Some of the key factors that drive the diversity among the serovars are the fimbrial operons present in the respective serovars (Supplemental Table 3). These phylogenetic results were consistent with the clustering generated by the Profile Assessment tool.

To assess the utility of the database for Salmonella characterization, differences in the VF profiles for the strains from the different serovars were compared in detail. Not surprisingly, the PCA results show that the S. Typhi isolates (n = 1, 536) separated from the NTS serovars (n = 42, 317). There were 28 genes present in the majority (more than 97%) of S. Typhi isolates but absent from the majority of other serovars that belong to three different gene clusters and their detailed functions are listed in Table 3. These included genes encoding a S.Typhi-specific fimbriae, type VI pilus, and the Vi antigen which are important for their pathogenesis30–32. Indeed, the Vi antigen production distinguishes S. Typhi from the NTS Salmonella32.

Table 7.

The list of the genes that are in majority (more than 97%) of S. Typhi isolates, but less than 5% in other serotypes studied.

| Genes | Functions |

|---|---|

| stgA, stgB, STY_RS18755, stgD | The stg gene cluster is S. Typhi -specific fimbrial operon. It expresses a functional adhesin that mediates adherence of serovar Typhi to host epithelial cells and inhibits phagocytosis, potentially contributing to the initial stages of typhoid fever pathogenesis |

| pilV/pilV2, pilL, pilM, pilNa, pilNb, pilO, pilP, pilQ, pilR, pilS, pilT and pilU | These genes belong to the pil operon, which encode proteins that are essential for the biogenesis of the R64 type IV pilus, which is used by S. Typhi to enter human intestinal epithelial cells. |

| vexA, vexB, vexC, vexD, vexE | encodes proteins required for transcriptional regulation of Vi production and biosynthesis (tviABCDE genes) and translocation (vexABCDE genes). |

| tviA, tviB, tviC, tviD, tviE |

The differences in the VF profiles of the representative isolates with the predominant virulence profiles from S. Typhimurium and S. I,4,[5],12:i:- were analyzed, and the genes unique to each isolate are listed in Table 3, along with their overall prevalence in these two serovars. Although there are 31 virulence genes listed as different between the predominant virulence profiles of these two serovars; with the exception of fljA, the overall presence rates of the other genes are not significantly different between the serovars. This further confirmed that the monophasic variant of S. Typhimurium, S. I,4,[5],12:i:- is closely related to S. Typhimurium. While four genes (allD, gip, hyi, and STM0520) are absent in the predominant virulence profile of S. Typhimurium, their presence rates in all the S. Typhimurium isolates analyzed in this study are more than 65%. Meanwhile, the other 27 VFs are absent in the predominant profile of S. I,4[5],12:i:- and present in the predominant virulence profile of S. Typhimurium, but their presence rates in all the S. Typhimurium isolates analyzed are relatively low. Except for fljA, the presence rates of each of the other 26 genes in the S. Typhimurium isolates is less than 60% (Table 3). The reasons for this phenomenon are that the VF profiles of S. Typhimurium are notably diverse, with a total 227 distinct VF profiles identified among the isolates analyzed (n = 1,081), and the predominant profile of S. Typhimurium are only present in 27.94% (302/1,081) of the strains. Notably, the majority of the 27 genes that are absent in the predominant VF profile of S. I,4,[5],12:i:- are located on pSLT virulence plasmid or SGI1. The spv locus (genes spvABCD and spvR), which is strongly associated with strains that cause NTS bacteremia and not present in typhoid strains, is missing in the majority (around 70%) of S. I,4,[5],12:i:- and 40% of S. Typhimurium isolates. The spv operon is associated with the survival and proliferation of Salmonella spp. within macrophages33. It encodes the primary virulence factors associated with serovar-specific virulence plasmids in S. enterica. The loss of the spv region eliminates the virulence phenotype of the serovars in their animal hosts and frequently in the mouse model, introducing a pSV (Salmonellavirulence plasmid) into a serovar naturally lacking it does not enhance the virulence properties of the strain, which implies that other chromosomally encoded factors are essential for the virulence phenotype19. The low presence rate of the spv locus in Salmonella shown in this study is consistent with earlier research indicating that only a small fraction of Salmonellaserovars contain this virulence operon34,35. Another operon that is missing from the predominant virulence profile of S. I,4,[5],12:i:- and has a low presence rate in both serovars is the pef fimbrial operon (plasmid-encoded fimbriae), which is responsible for the adhesion of Salmonellaspp. to the surface of various cell lines15,36. Since most plasmids impose fitness costs on their hosts, the loss of the plasmid-encoded VFs in Salmonella isolates may have evolutionary advantages that have resulted in its emergence over the past decade. Also, the genes located on SGI-1, a genomic island containing an antibiotic resistance gene cluster, are missing in 99% of the S. I,4,[5],12:i:- isolates and exist in only around 31% of S. Typhimurium isolates. Other VFs that have lower presence rates in S. I,4,[5],12:i:- include fliA, rck, and traT. fljA encodes an inhibitor of fliC, which encodes a phase 1 flagellin protein, FliC, that is important to flagellar motility and biofilm formation37. This result is consistent with the previous finding that S. I,4,[5],12:i:- is closely related to S. Typhimurium but lacks the expression of fliA and fljB(encoding phase 2 flagellin) common to all Typhimurium isolates24. rck is located close to the pefoperon on pSV, and it encodes a protein with resistance to complement killing that can recruit various complement inhibitors to resist the attack of the innate immune system and has been implicated in the invasion of epithelial cells15. traTencodes a 27 kDa protein that imparts weak resistance to serum killing and is a component of the plasmid transfer region15.

The major difference between the VF profiles of S. I,4[5],12:i:- and S. Saintpaul is the presence of a fimbrial gene cluster (stkABCDEFG) that occurs in about 67% of S. Saintpaul isolates, but only about 3% in S. I,4[5],12:i:- (Supplemental Table 4). The stk fimbrial operon encodes putative Stk fimbriae and was initially reported to be specific for S. Paratyphi A38. However, subsequent studies revealed the presence of this operon in other NTS, such as S. Heidelberg, and S. Kentucky38. Our results showed that this operon has high presence rates in serovars Hadar, Indiana, and Heidelberg with a presence rate of more than 99% in S. Hadar and S. Indiana and more than 97% in S. Heidelberg (Supplemental Table 4). The presence rate in the rest of the serovars analyzed in this study was around or less than 1%. The genes that are missing in almost all S. Saintpaul isolates, but present the great majority of S. I,4[5],12:i:- are the T3SS effectors sseK1 and sseK3.These effectors encode SseK proteins, which are reported to help inhibit antibacterial and inflammatory host responses15,39. While the presence rate of sseK1 and sseK3 in S. Saintpaul is only about 3%, another gene variant, sseK2, is detected in more than 99% of all serovars analyzed in this study, including S. Saintpaul (Supplemental Table 4). In all the isolates analyzed in this study, the presence rate of sseK1 and sseK3 is consistent, either more than 99% or less than 3% in a particular serovar. This phenomenon is logical given the collaborative inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway by SseK1 and SseK3 during Salmonellainfection in macrophages19. Although SseK2 can inhibit TNF-α-induced NF-κB reporter activation, its impact on the NF-κB pathway during Salmonellainfection in macrophages is minimal15. Further research is needed to explore the role SseK2 plays in Salmonella virulence, considering its high prevalence in S. enterica strains. The other two genes, gogBand STM2585, encode T3SS effectors that are involved in the inflammatory response40.

The differences in the major VF profiles between serovars S. Enteritidis and S. Dublin are due to 12 genes (Table 5). The plasmid encoded fimbriae genes (pefACD), and resistance to complement killing (rck) are missing from more than 99% of the S. Dublin isolates. Conversely, the genes sciR, sciS, tssA, and xis are missing from the majority isolate of S. Enteritidis, but present in greater than 97% of S. Dublin. The genes sciRS, and tssA encode a T6SS, which is a contact-dependent contractile apparatus that contributes to Salmonellacompetition with the host microbiota and its interaction with infected host cells41–44. These findings highlight that these S. Enteritidis lack the T6SS, which is consistent with the previous finding that several genomic islands appear absent or degenerate in S.Enteritidis45.

Salmonella virulence systems are very complex, as many genes are involved in contributing to their virulence. Numerous VFs, including adhesion molecules, invasins, lipopolysaccharides, polysaccharide capsules, iron acquisition factors, host defense-subverting mechanisms, and toxins, have been identified in Salmonella, and these VFs play different roles during infection to enable the bacterial cells to colonize the host, disseminate, and cause disease15. The difference in the presence/absence of the virulence genes in each isolate/serovar might indicate their relative virulence to humans or other animal species. Therefore, the development of enhanced tools to identify Salmonella VFs can help to predict virulence potential and explain the observed clinical disparities in disease pathogenesis, which is important to understand risks associated with different Salmonella genotypes.

Conclusions

Salmonella enterica remains a significant contributor to foodborne illnesses worldwide, necessitating a deeper understanding of its virulence potential. These insights are crucial for developing targeted prevention and treatment strategies, improving vaccine design, and enhancing public health interventions to better control and reduce Salmonella-related infections. By comprehensively analyzing virulence gene profiles, researchers can identify mechanisms that contribute to the ability of S. enterica to cause disease and better assess the potential risk of causing disease in humans posed by the different Salmonella serovars as well as through specific S. enterica strains. The Salmonella Virulence Database and tools evaluated in the current project offer invaluable bioinformatic resources for identifying and characterizing these virulence genes. Making these resources publicly accessible empowers FDA scientists and the wider scientific community to comprehensively evaluate Salmonella virulence. Moreover, the tools’ capacity for phylogenetic comparison of virulence genes across various strains and serovars, particularly between isolates that cause severe disease and those associated with milder illness, will facilitates the identification of key VFs that influence and contribute to infection and disease severity. These attributes will enhance our capacity to effectively mitigate Salmonella-related health risks.

While this study significantly advances our understanding of the virulence of S. enterica isolates, there are limitations that require further investigation. For instance, although the current database includes a comprehensive list of virulence factors, it largely depends on existing information and may miss novel virulence factors that have yet to be identified or characterized, particularly in emerging or less-studied Salmonella serovars. Ongoing literature review and mining of WGS data from emergent pathogens will be essential to capture these newly discovered VFs. Additionally, although the bioinformatics tools are effective in identifying virulence genes, their presence does not guarantee that they are expressed or functional. Future research could address these limitations by incorporating experimental approaches, such as in vitro and in vivo assays, to validate bioinformatics predictions and uncover new virulence mechanisms.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Center for Toxicological Research and U.S. Food and Drug Administration. All the authors thank Drs. Ashraf Khan and OhGew Kweon for reviewing the manuscript.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Department of Health and Human Services, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, or the U.S. Government. Reference to any commercial materials, equipment, or process does not in any way constitute approval, endorsement, or recommendation by the Food and Drug Administration.

Author contributions

J.H., S.Z. and S.L.F. conceptualized the database and identified the virulence factor list. J.H. and H.T. developed the computational approaches for the database and analysis tool development. J.H. and S.L.F. evaluated the database tools. S.L.F. secured the funds for the project. All authors contributed to the draft manuscript development and revising and completing the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

All data is publicly available through GenBank and identified in the Supplemental Tables of the manuscript. The DNA and amino acid sequences of the database genes are provided in Supplemental Tables 2 and at the database website (https://virulence.fda.gov). Supplemental Table 2 also provides the GenBank accession number and locations of the reference genes and corresponding protein IDs for the virulence factors included in the database. Supplemental Tables 1 and 3 includes the GenBank Assembly Accession numbers for the genomes used for the evaluation of the Virulence Factor Profile Comparison and Virulence Factor Profile Assessment tools, respectively.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jing Han, Email: jing.han1@fda.hhs.gov.

Steven L. Foley, Email: Steven.Foley@fda.hhs.gov

References

- 1.CDC. in Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019. (2019).

- 2.(IFSAC), T.I.F.S.A.C. Foodborne illness source attribution estimates for 2017 for Salmonella, Escherichia coli O157, Listeria monocytogenes, and Campylobacter using multi-year outbreak surveillance data, United States (2019).

- 3.CDC. National Salmonella Surveillance Annual Report, 2018. (2016).

- 4.Sayers, S. et al. Victors: A web-based knowledge base of virulence factors in human and animal pathogens. Nucleic Acids Res.47(D1), D693–D700 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andino, A. & Hanning, I. Salmonella enterica: Survival, colonization, and virulence differences among serovars.Sci. World J.2015, 520179 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Foley, S. L. & Lynne, A. M. Food animal-associated Salmonella challenges: Pathogenicity and antimicrobial resistance. J. Anim. Sci.86(14 Suppl), E173–E187 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fierer, J. Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella (iNTS) infections. Clin. Infect. Dis.75 (4), 732–738 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suez, J. et al. Virulence gene profiling and pathogenicity characterization of non-typhoidal Salmonella accounted for invasive disease in humans. PLoS One. 8 (3), e58449 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson, T. J. & Nolan, L. K. Pathogenomics of the virulence plasmids of Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev.73 (4), 750–774 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gokulan, K. et al. Impact of plasmids, including those encodingVirB4/D4 type IV secretion systems, on Salmonella enterica Serovar Heidelberg virulence in macrophages and epithelial cells. PLoS One. 8 (10), e77866 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown, E. et al. Use of whole-genome sequencinG for food safety and public health in the United States. Foodborne Pathog Dis.16(7), 441–450 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mao, C. et al. Curation, integration and visualization of bacterial virulence factors in PATRIC. Bioinformatics. 31 (2), 252–258 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wattam, A. R. et al. Improvements to PATRIC, the all-bacterial bioinformatics database and analysis resource center. Nucleic Acids Res.45(D1), D535–D542 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen, L. et al. VFDB: a reference database for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Res.33 (Database issue), D325–D328 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han, J. et al. Infection biology of Salmonella enterica. EcoSal Plus, eesp–0001. (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.McKinney, W. Pandas: A foundational python library for data analysis and statistics. Python High. Perform. Sci. Comput.14(9), 1–9 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azimi, T. et al. Molecular mechanisms of Salmonella effector proteins: A comprehensive review. Infect. Drug Resist.13, 11–26 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dos Santos, A. M. P., Ferrari, R. G. & Conte-Junior, C. A. Virulence factors in Salmonella Typhimurium: The sagacity of a bacterium. Curr. Microbiol.76(6), 762–773 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silva, C., Puente, J. L. & Calva, E. Salmonella Virulence plasmid: Pathogenesis and ecology. Pathog. Dis. (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Sharma, A. K. et al. Bacterial virulence factors: Secreted for survival. Indian J. Microbiol.57(1), 1–10 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Algarni, S. et al. Development of an antimicrobial resistance plasmid transfer gene database for enteric bacteria. Front. Bioinform. 3, 1279359 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tate, H. et al. Genomic diversity, antimicrobial resistance, and virulence gene profiles of Salmonella Serovar Kentucky isolated from humans, food, and animal Ceca content sources in the United States. Foodborne Pathog Dis.19(8), 509–521 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aljahdali, N. H. et al. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of incompatibility group FIB positive Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium isolates from Food animal sources. Genes (Basel), 11(11), (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Switt, A. I. et al. Emergence, distribution, and molecular and phenotypic characteristics of Salmonella enterica serotype 4,5,12:i. Foodborne Pathog Dis.6 (4), 407–415 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hopkins, K. L. et al. Multiresistant Salmonella enterica serovar 4,[5],12:i:- in Europe: A new pandemic strain?. Euro. Surveill15(22), 19580 (2010). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marcus, S. L. et al. Salmonella pathogenicity islands: big virulence in small packages. Microbes Infect.2 (2), 145–156 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teklemariam, A. D. et al. Human salmonellosis: A continuous global threat in the farm-to-Fork Food Safety Continuum. Foods, 12(9). (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Cheng, R. A. & Wiedmann, M. Recent advances in our understanding of the diversity and roles of chaperone-usher Fimbriae in facilitating Salmonella host and tissue tropism. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.10, 628043 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Humphries, A. D. et al. Role of fimbriae as antigens and intestinal colonization factors of Salmonella serovars. FEMS Microbiol. Lett.201 (2), 121–125 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forest, C. et al. Contribution of the stg fimbrial operon of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhi during interaction with human cells. Infect. Immun.75 (11), 5264–5271 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang, X. L. et al. Salmonella enterica serovar typhi uses type IVB pili to enter human intestinal epithelial cells. Infect. Immun.68 (6), 3067–3073 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wear, S. S. et al. Investigation of core machinery for biosynthesis of vi antigen capsular polysaccharides in Gram-negative bacteria. J. Biol. Chem.298 (1), 101486 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rychlik, I., Gregorova, D. & Hradecka, H. Distribution and function of plasmids in Salmonella enterica. Vet. Microbiol.112 (1), 1–10 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huehn, S. et al. Virulotyping and antimicrobial resistance typing of Salmonella enterica serovars relevant to human health in Europe. Foodborne Pathog Dis.7 (5), 523–535 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lan, T. T. Q. et al. Distribution of virulence genes among Salmonella Serotypes isolated from pigs in Southern Vietnam. J. Food. Prot.81 (9), 1459–1466 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baumler, A. J. et al. The pef fimbrial operon of Salmonella typhimurium mediates adhesion to murine small intestine and is necessary for fluid accumulation in the infant mouse. Infect. Immun.64 (1), 61–68 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang, F. et al. Flagellar Motility is Critical for Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Biofilm Development. (1664-302X (Print)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Tawfick, M. M., Rosser, A. & Rajakumar, K. Heterologous expression of the Salmonella enterica Serovar Paratyphi A Stk fimbrial operon suggests a potential for repeat sequence-mediated low-frequency phase variation. Infect. Genet. Evol.85, 104508 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El Qaidi, S. et al. NleB/SseK effectors from Citrobacter rodentium, Escherichia coli, and Salmonella enterica display distinct differences in host substrate specificity. J. Biol. Chem.292(27), 11423–11430 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jaslow, S. L. et al. Salmonella activation of STAT3 signaling by SarA effector promotes intracellular replication and production of IL-10. Cell. Rep.23(12), 3525–3536 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mulder, D. T., Cooper, C. A. & Coombes, B. K. Type VI secretion system-associated gene clusters contribute to pathogenesis of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium. Infect. Immun.80 (6), 1996–2007 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bao, H. et al. Genetic diversity and evolutionary features of type VI secretion systems in Salmonella. Future Microbiol.14, 139–154 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen, C., Yang, X. & Shen, X. Confirmed and potential roles of bacterial T6SSs in the intestinal ecosystem. Front. Microbiol.10, 1484 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blondel, C. J. et al. Identification and distribution of new candidate T6SS effectors encoded in Salmonella pathogenicity Island 6. Front. Microbiol.14, 1252344 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomson, N. R. et al. Comparative genome analysis of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 and Salmonella Gallinarum 287/91 provides insights into evolutionary and host adaptation pathways. Genome Res.18 (10), 1624–1637 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data is publicly available through GenBank and identified in the Supplemental Tables of the manuscript. The DNA and amino acid sequences of the database genes are provided in Supplemental Tables 2 and at the database website (https://virulence.fda.gov). Supplemental Table 2 also provides the GenBank accession number and locations of the reference genes and corresponding protein IDs for the virulence factors included in the database. Supplemental Tables 1 and 3 includes the GenBank Assembly Accession numbers for the genomes used for the evaluation of the Virulence Factor Profile Comparison and Virulence Factor Profile Assessment tools, respectively.