Abstract

Objectives

Disease activity control in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) with corticosteroid and immunosuppressant withdrawal is a treatment goal. We evaluated whether this could be attained with sequential subcutaneous belimumab (BEL) and one cycle of rituximab (RTX).

Methods

In this phase 3, double-blind BLISS-BELIEVE trial (GSK Study 205646), patients with active SLE initiating subcutaneous BEL 200 mg/week for 52 weeks were randomised to intravenous placebo (BEL/PBO) or intravenous RTX 1000 mg (BEL/RTX) at weeks 4 and 6 while stopping concomitant immunosuppressants/tapering corticosteroids; standard therapy for 104 weeks (BEL/ST; reference arm) was included. Primary endpoint: proportion of patients achieving disease control (SLE Disease Activity Index-2000 (SLEDAI-2K) ≤2; without immunosuppressants; prednisone equivalent ≤5 mg/day) at week 52 with BEL/RTX versus BEL/PBO. Major (alpha-controlled) secondary endpoints: proportion of patients with clinical remission (week 64; clinical SLEDAI-2K=0, without immunosuppressants/corticosteroids); proportion of patients with disease control (week 104). Other assessments: disease control duration, anti-dsDNA antibody, C3/C4 and B cells/B-cell subsets.

Results

The modified intention-to-treat population included 263 patients. Overall, 16.7% (12/72) of BEL/PBO and 19.4% (28/144) of BEL/RTX patients achieved disease control (OR (95% CI) 1.27 (0.60 to 2.71); p=0.5342) at week 52. For major secondary endpoints, differences between BEL/RTX and BEL/PBO were not statistically significant. Anti-dsDNA antibodies and most assessed B cells/B-cell subsets were lower with BEL/RTX versus BEL/PBO. Mean disease control duration through 52 weeks was significantly greater with BEL/RTX versus BEL/PBO.

Conclusions

BEL/RTX showed no superiority over BEL/PBO for most endpoints analysed; however, it led to significant improvements in disease activity markers compared with BEL/PBO. Further investigation of combination treatment is warranted.NCT03312907

Trial registration number

Keywords: Autoimmune Diseases; Biological Therapy; B-Lymphocytes; Lupus Erythematosus, Systemic; Rituximab

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Achieving low disease activity in the absence of corticosteroids remains an important treatment goal in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Preliminary studies suggested that sequential therapy with belimumab and rituximab in patients with active SLE may provide clinical benefits with an acceptable safety profile.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

In this robust phase 3 BLISS-BELIEVE study of sequential belimumab and rituximab administration, while the primary and major secondary endpoints were not met, the mean duration of longest disease control was nominally significantly greater in patients treated with belimumab and rituximab sequential therapy compared with belimumab and placebo.

Significant reductions in anti-dsDNA antibody levels, CD19+ B cells and B-cell subsets, were observed with belimumab and rituximab sequential therapy versus belimumab and placebo.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

This is the first randomised study in SLE to prospectively investigate a novel treatment regimen that incorporated a rapid reduction and withdrawal of standard immunosuppressants and thereby it sets the stage for future trials in SLE to aim for the stringent, clinically meaningful endpoint of remission off-therapy.

Introduction

Despite traditional standard therapy (ST), including medications such as corticosteroids, antimalarials and immunosuppressants, a significant proportion of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) do not achieve long-term disease control.1,3 As prolonged exposure to glucocorticoids increases the risk of organ damage accrual,4 management guidelines recommend tapering corticosteroids to ≤5 mg/day or withdrawing entirely when possible.3 Furthermore, the treat-to-target principle has been embraced by SLE experts where, besides achieving low disease activity, treatment goals should be remission on-therapy and, even more aspirational, remission off-therapy.5 6 Notwithstanding these ambitious goals, achieving disease control without corticosteroids remains an unmet treatment goal, but no randomised trial has previously employed these endpoints.2 These goals could be achieved with disease-modifying therapies targeting the underlying pathogenesis of SLE.7

B cells play a key role in the pathogenesis of SLE.8 B-lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS) promotes B-cell activation and differentiation,9,11 and elevated serum BLyS is associated with higher disease activity, disease relapse and increased numbers of autoantibody-secreting plasma cells.9 12

Belimumab, a human IgG1λ monoclonal antibody that selectively inhibits soluble BLyS, is approved in combination with ST for treating SLE and lupus nephritis (LN).13 14 Rituximab, a B-cell-depleting anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, is used off-label in clinical practice as clinical trials have not demonstrated clinical efficacy.815,18

The scientific justification for sequential therapy with belimumab and rituximab is twofold. Elevated BLyS levels, which occur following B-cell depletion, promote the maturation of autoreactive B cells by allowing them to bypass tolerance checkpoints and enter the immune repertoire.19,22 Conversely, B-cell reconstitution without high levels of BLyS might result in tolerised B cells without autoreactivity and an enhanced clinical response. This potentially explains the inability of rituximab alone to show superiority over ST in SLE studies.23 A second rationale for dual therapy is that although rituximab rapidly depletes peripheral B cells, tissue-resident B cells are less affected.24,26 Thus, since belimumab was shown to increase circulating B-cell levels by either disrupting lymphocyte trafficking and preventing B cells from transmigrating from the blood into tissue or by preventing B cells from being retained at the tissue level, greater B-cell depletion may occur when belimumab is administered before rituximab.27,34

Three small phase 2 trials, Synbiose (in patients with severe, refractory SLE, of whom the majority had active LN), Belimumab after B cell depletion therapy in patients with SLE (BEAT-LUPUS; in refractory SLE) and The Combination of Antibodies in Lupus Nephritis: Belimumab and Rituximab Assessment of Tolerance and Efficacy (CALIBRATE; in LN), have evaluated the efficacy and safety of rituximab and belimumab sequential therapy in improving disease biomarkers and outcomes, including B-cell depletion.31 32 35 We have therefore hypothesised that the belimumab/rituximab combination may result in greater B-cell depletion and thus yield better control of disease activity with less need for concomitant immunosuppressants and corticosteroids than belimumab alone. To test this hypothesis, we evaluated the efficacy, safety and tolerability of belimumab with or without a single cycle of rituximab while stopping concomitant immunosuppressants and tapering corticosteroids in adult patients with SLE, using novel and stringent disease control endpoints.

Methods

Study design

This phase 3, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 104-week study (GSK Study 205646, NCT03312907) was conducted at 71 sites globally between March 2018 and July 2021 (online supplemental figure S1). The study protocol has been published previously.28

Patients

Eligible patients were ≥18 years of age, fulfilled ≥4 of the 11 American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for SLE,36 37 and were required to have serum positivity for anti-nuclear antibody (titre ≥1:80) and/or anti-dsDNA antibody (≥30 IU/mL) and an SLE Disease Activity Index-2000 (SLEDAI-2K) score ≥6. Patients with severe LN or severe, active central nervous system lupus were excluded. Full eligibility criteria have been published previously.28

Randomisation and masking

Patients were centrally randomised in a 1:2:1 ratio to: (1) BEL/PBO arm: subcutaneous (SC) belimumab 200 mg/week for 52 weeks and intravenous placebo at weeks 4 and 6; (2) BEL/RTX arm: belimumab 200 mg/week SC for 52 weeks and rituximab 1000 mg/week intravenous at weeks 4 and 6; or (3) BEL/ST arm: open-label belimumab 200 mg/week SC and ST for 104 weeks. The BEL/ST arm was included to provide an exploratory reference for assessing the relative performance of BEL/RTX versus BEL/PBO. Patients were stratified by their screening SLEDAI-2K score (≤9 or ≥10), immunosuppressant use (yes/no) and corticosteroid dose (prednisone equivalent ≤10 or >10 mg/day).

Procedures

BEL/PBO and BEL/RTX patients received study treatment until week 52 (primary efficacy endpoint assessment) and then entered a 52-week, treatment-free (no belimumab or rituximab) double-blind observational phase through week 104 to allow assessment of the durability of remission. During the double-blind observational phase, comprehensive clinical assessments were scheduled at week 60, week 64 and every 8 weeks thereafter up to week 104. Data were also collected at any unscheduled visits that occurred. Patients were considered to have failed treatment if they received, at the investigator’s discretion, corticosteroids (>5 mg/day), any immunosuppressants, and/or open-label belimumab (online supplemental materials). BEL/ST patients received belimumab and continued their ST throughout the 104 weeks.

Antimalarials, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and/or prednisone-equivalent doses of ≤5 mg/day were allowed within protocol-defined limits in weeks 53 through 104 in all treatment groups.

Discontinuation of immunosuppression and tapering of corticosteroids

All BEL/PBO and BEL/RTX patients discontinued immunosuppressants at or before week 4. Reinitiation of immunosuppressants post week 4 in BEL/PBO and BEL/RTX groups (on the physician discretion) resulted in treatment failure. In the BEL/ST group, an increase of immunosuppressant dose post week 12 resulted in treatment failure. After the initial 12 weeks of study treatment, all treatment groups were required to taper prednisone-equivalent dose to ≤5 mg/day by week 26. Patients were considered treatment failures if their dose exceeded 5 mg/day after week 26 (online supplemental materials).

Outcomes

Efficacy endpoints

The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients achieving a state of disease control at week 52, defined as a SLEDAI-2K score ≤2 achieved without immunosuppressants and with a prednisone-equivalent dose of ≤5 mg/day.

Major secondary endpoints were the proportion of patients in clinical remission at week 64, defined as a clinical SLEDAI-2K score of 0 (without a serological activity component) achieved without immunosuppressants and with a prednisone-equivalent dose of 0 mg/day, and the proportion of patients with a state of disease control (defined as per primary endpoint) at week 104. Additional secondary efficacy endpoints included analysis of the primary efficacy endpoint by baseline characteristics (age, race, sex, SLEDAI-2K, use of immunosuppressants, corticosteroid dose, complement 3/4 (C3/C4) and anti-dsDNA antibody levels, BLyS levels, and region). As the BEL/ST arm was open label, the primary and major secondary assessments were conducted by independent blinded assessors (IBA).

Secondary efficacy endpoints that were assessed by principal investigators (PI) included duration of disease control through 52 and 104 weeks in patients achieving disease control at ≥1 time point; time to disease control (defined as per primary endpoint); time to clinical remission (defined as per secondary endpoint); change from baseline in SLEDAI-2K score and the proportion of patients achieving Lupus Low Disease Activity State (LLDAS)38 39 at weeks 52, 64 and 104.

Time-to-first severe flare was measured through week 104 by a modified SLE Flare Index (SFI), which did not consider severe flares that were triggered only by an increase in SLEDAI-2K score to >12, but included patients classified as a treatment failure by our stringent definition (eg, receiving corticosteroid dose >5 mg/day after week 26, restarting belimumab in year 2 (BEL/PBO or BEL/RTX)), as having a severe flare. Post hoc analyses were also performed to assess disease control at week 52 by baseline proteinuria (≤0.5 g/24 hours vs >0.5 g/24 hours), time to severe flare (modified SFI) without imputing treatment failures as a flare, proportions of patients with proteinuria shift from >0.5 g/24 hours to normal (≤0.5 g/24 hours) and prednisone-equivalent reduction by ≥25% from baseline to ≤7.5 mg/day during weeks 40 through 52.

Biomarker endpoints

Prespecified biomarker endpoints included changes from baseline in IgG, anti-dsDNA antibody and complement C3/C4 levels. Proportions of patients with anti-dsDNA antibody shift from positive at baseline to negative, and with C3/C4 shifts from low at baseline to normal/high were also assessed. B cells and B-cell subsets were assessed by flow cytometric characterisation. Central laboratory testing was used for all biomarker measurements. Biomarker endpoints were assessed statistically at weeks 52, 64 and 104.

Safety endpoints

Safety assessments included adverse events (AEs), serious AEs, AEs of special interest (malignant neoplasms; post-injection/infusion anaphylaxis/hypersensitivity reactions; all infections of special interest (opportunistic infections, herpes zoster, tuberculosis and sepsis); depression/suicide/self-injury) and deaths. AEs are reported on treatment for week 52 (year 1) and on study for week 104 (year 1+2).

Statistical analysis

The target sample size of 280 patients was expected to achieve ≥98% power to detect a treatment difference in the primary endpoint at the 5% two-sided level of significance, assuming response rates of 10% and 35% in the BEL/PBO and BEL/RTX groups (1:2 randomisation), respectively.

All randomised patients who received ≥1 dose of study treatment were included in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population. Efficacy endpoints were assessed using a modified ITT (mITT) population, which comprised the ITT population but excluded 29 patients from the BEL/ST group due to IBAs being potentially unblinded.

Primary and the two major secondary efficacy endpoints were alpha controlled using a prespecified testing order; endpoints could be tested in sequence (two-sided alpha=0.05), provided that statistical significance was achieved in all prior tests. These endpoints were analysed using logistic regression adjusted for baseline SLEDAI-2K score (≤9 or ≥10), immunosuppressant use (use or no use), prednisone-equivalent dose (≤10 mg/day or >10 mg/day) and treatment group. As the primary endpoint was not statistically significant, the p values for the two major secondary endpoints are nominal.

Other endpoints were not adjusted for multiplicity, and all associated p values are nominal.

Patients who met treatment-failure criteria, withdrew or missed assessments (and subsequent data collection was not possible) were regarded as non-responders for primary and secondary efficacy assessments and as experiencing a severe flare for the modified SFI flare endpoint. Other analyses were not alpha controlled; preplanned analyses were performed at weeks 52, 64 and 104.

The post hoc analysis for proteinuria is described in the online supplemental materials.

Biomarker outcomes were performed on observed data for ITT patients who were ongoing after 52 weeks and received both intravenous doses of rituximab or placebo or who remained on open-label belimumab through week 52 (for BEL/ST group) and did not have more than 28 consecutive days from baseline to week 51 without a belimumab dose. Year 1 and 2 analyses used data collected in year 1 before belimumab restart (BEL/PBO and BEL/RTX groups) or discontinuation (BEL/ST group) for patients who completed week 52 on treatment. No imputation was carried out for missing data in these analyses.

Safety endpoints were summarised descriptively.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination of this research.

Role of the funding source

This study (GSK Study 205646) was funded by GSK. GSK was involved in designing the study, contributed to the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, supported the authors in the manuscript development, and funded the medical writing assistance. All authors approved the content of the submitted manuscript and were involved in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

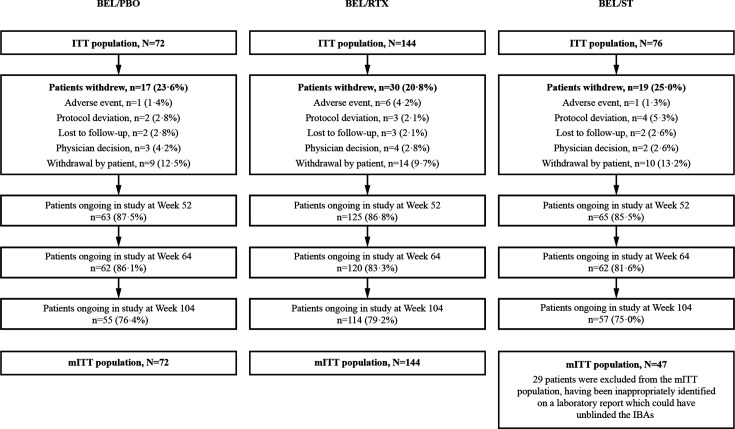

Of 396 patients screened, 292 were included in the ITT population and 263 in the mITT population. Overall, 226/292 (77.4%) patients completed the study at week 104, with 215 of these patients having completed the scheduled study treatment up to Week 52. Across all groups, the most common reason for not completing the study was the patient’s decision to withdraw (figure 1).

Figure 1. Patient disposition summary. mITT population excludes 29 patients from the BEL/ST group, due to IBAs being potentially unblinded. BEL, belimumab; IBA, independent blinded assessor; ITT, intention-to-treat; mITT, modified intention-to-treat; RTX, rituximab; ST, standard therapy.

Baseline characteristics were similar across treatment groups. The mean (SD) glucocorticoid dose was 10.0 (10.49) mg/day; most patients (80.8%) were taking glucocorticoids, followed by antimalarials (79.8%; table 1).

Table 1. Patient baseline characteristics (ITT population, N=292).

| BEL/PBO (n=72) | BEL/RTX (n=144) | BEL/ST* (n=76) | Total (N=292) | |

| Region, n (%) | ||||

| USA/Canada | 33 (45.8) | 54 (37.5) | 30 (39.5) | 117 (40.1) |

| Europe | 12 (16.7) | 34 (23.6) | 13 (17.1) | 59 (20.2) |

| Rest of world | 27 (37.5) | 56 (38.9) | 33 (43.4) | 116 (39.7) |

| Female, n (%) | 66 (91.7) | 129 (89.6) | 73 (96.1) | 268 (91.8) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 40.6 (12.58) | 40.1 (11.45) | 41.0 (12.75) | 40.5 (12.04) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 17 (23.6) | 33 (22.9) | 22 (28.9) | 72 (24.7) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 55 (76.4) | 111 (77.1) | 54 (71.1) | 220 (75.3) |

| Race†, n (%) | ||||

| White | 39 (54.2) | 101 (70.1) | 48 (63.2) | 188 (64.4) |

| African American/Black African ancestry | 21 (29.2) | 22 (15.3) | 13 (17.1) | 56 (19.2) |

| Asian | 10 (13.9) | 17 (11.8) | 12 (15.8) | 39 (13.4) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1 (1.4) | 3 (2.1) | 3 (3.9) | 7 (2.4) |

| Multiple | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.3) | 3 (1.0) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 2 (0.7) |

| SLE disease duration (years), median (IQR) | 6.5 (3.0–14.2) | 7.7 (3.1–12.7) | 7.1 (1.7–12.3) | 7.2 (2.9–12.9) |

| SLEDAI-2K score (PI)‡, mean (SD) | 10.2 (3.94) | 10.5 (4.06) | 9.9 (3.29) | 10.3 (3.84) |

| SLEDAI-2K category (PI), n (%) | ||||

| ≤9 | 35 (48.6) | 62 (43.1) | 34 (44.7) | 131 (44.9) |

| 10–11 | 18 (25.0) | 31 (21.5) | 20 (26.3) | 69 (23.6) |

| ≥12 | 19 (26.4) | 51 (35.4) | 22 (28.9) | 92 (31.5) |

| Proteinuria (>0.5 g/24 hours),§ n (%) | 11 (16.2) | 24 (17.8) | 15 (21.1) | 50 (18.2) |

| Proteinuria (g/24 hours), mean (SD) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.3 (0.6) |

| Biomarkers, n (%) | ||||

| Anti-dsDNA antibody positive (≥30 IU/mL) | 44 (61.1) | 95 (66.0) | 44 (57.9) | 183 (62.7) |

| Low C3 (<90 mg/dL) | 28 (38.9) | 62 (43.1) | 26 (34.2) | 116 (39.7) |

| Low C4 (<10 mg/dL) | 13 (18.1) | 41 (28.5) | 11 (14.5) | 65 (22.3) |

| ≥1 low C3 (<90 mg/dL) or C4 (<10 mg/dL) | 31 (43.1) | 71 (49.3) | 28 (36.8) | 130 (44.5) |

| Low C3/C4 levels and anti-dsDNA antibody positive | 27 (37.5) | 62 (43.1) | 21 (27.6) | 110 (37.7) |

| Medication use at baseline, n (%) | ||||

| Glucocorticoid dose (mg/day), mean (SD) | 9.4 (9.27) | 9.5 (8.21) | 11.8 (14.59) | 10.0 (10.49) |

| Antimalarials, n (%) | 61 (84.7) | 112 (77.8) | 60 (78.9) | 233 (79.8) |

| Glucocorticoids,¶ n (%) | 60 (83.3) | 116 (80.6) | 60 (78.9) | 236 (80.8) |

| Glucocorticoid dose category, n (%) | ||||

| 0 to ≤5 mg/day | 30 (41.7) | 58 (40.3) | 28 (36.8) | 116 (39.7) |

| >5 mg/day | 42 (58.3) | 86 (59.7) | 48 (63.2) | 176 (60.3) |

| Immunosuppressants, n (%) | 37 (51.4) | 73 (50.7) | 38 (50.0) | 148 (50.7) |

| Immunosuppressants+antimalarials, n (%) | 4 (5.6) | 13 (9.0) | 8 (10.5) | 25 (8.6) |

| Glucocorticoids + antimalarials, n (%) | 24 (33.3) | 46 (31.9) | 28 (36.8) | 98 (33.6) |

| Glucocorticoids + immunosuppressants, n (%) | 7 (9.7) | 14 (9.7) | 8 (10.5) | 29 (9.9) |

| Glucocorticoids + immunosuppressants + antimalarials, n (%) | 26 (36.1) | 43 (29.9) | 19 (25.0) | 88 (30.1) |

| Azathioprine | 12 (16.7) | 16 (11.1) | 11 (14.5) | 39 (13.4) |

| Methotrexate | 10 (13.9) | 28 (19.4) | 12 (15.8) | 50 (17.1) |

| Cyclosporine | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Tacrolimus | 4 (5.6) | 4 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (2.7) |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 5 (6.9) | 15 (10.4) | 8 (10.5) | 28 (9.6) |

| Mycophenolate sodium | 1 (1.4) | 4 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.7) |

| Mycophenolic acid | 7 (9.7) | 10 (6.9) | 8 (10.5) | 25 (8.6) |

| Leflunomide | 2 (2.8) | 2 (1.4) | 1 (1.3) | 5 (1.7) |

ST included corticosteroids, antimalarials, immunosuppressants, and NSAIDs.

Patients who checked more than one race category are counted under individual race category per the minority rule as well as the Multiple category.

BEL/PBO, n=71; BEL/RTX, n=143; BEL/ST, n=76, Ttotal, N=290.

BEL/PBO, n=68; BEL/RTX, n=135; BEL/ST, n=71, total, N=274.

Prednisone equivalent.

BEL, belimumab; C3/4, complement 3/4; ITT, intention-to-treat; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PBO, placebo; PI, principal investigator; RTX, rituximab; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SLEDAI-2K, SLE Disease Activity Index-2000; ST, standard therapy

Efficacy results

At week 52, 16.7% of BEL/PBO-treated and 19.4% of BEL/RTX-treated patients achieved disease control, which was not statistically significant (table 2). Of note, 25.5% of BEL/ST-treated patients achieved disease control. The observed differences in individual components of disease control between BEL/RTX and BEL/PBO groups are summarised in online supplemental table S1, and the first reasons for not achieving disease control at Week 52 in online supplemental table S2.

Table 2. Summary of primary and major secondary efficacy endpoints, based on IBA assessment (mITT population,* N=263).

| Observed response rate, n (%) | BEL/RTX versus BEL/PBO | |||||

| Blinded BEL/PBO(n=72) | Blinded BEL/RTX(n=144) | Open-label BEL/ST reference arm†(n=47) | Observed treatment difference(%) | OR (95% CI)‡ | P value‡ | |

| Primary endpoint | ||||||

| Disease control§ at week 52 | 12 (16.7) | 28 (19.4) | 12 (25.5) | 2.78 | 1.27 (0.60 to 2.71) | 0.5342 |

| Major secondary endpoints | ||||||

| Clinical remission§ at week 64 | 4 (5.6) | 9 (6.3) | 5 (10.6) | 0.69 | 1.12 (0.33 to 3.78) | 0.8582 |

| Disease control§ at week 104 | 5 (6.9) | 16 (11.1) | 10 (21.3) | 4.17 | 1.64 (0.57 to 4.72) | 0.3613 |

mITT population excludes 29 patients from the BEL/ST group, due to independent blinded assessors being potentially unblinded.

ST included corticosteroids, antimalarials, immunosuppressants and NSAIDs.

OR (95% CI), adjusted treatment difference (95% CI), and p value are from a logistic regression model with covariates: baseline SLEDAI-2K, baseline immunosuppressants, baseline prednisone-equivalent dose and treatment group.

Disease control defined as SLEDAI-2K score ≤2 achieved without immunosuppressants and with a prednisone-equivalent dose of ≤5 mg/day; clinical remission defined as a clinical SLEDAI-2K score=0, without immunosuppressants and with corticosteroids at a prednisone-equivalent dose of 0 mg/day.

BEL, belimumab; IBA, independent blinded assessor; mITT, modified intention-to-treat; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PBO, placebo; RTX, rituximab; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SLEDAI-2K, SLE Disease Activity Index-2000; ST, standard therapy

Proportions of patients off-treatment achieving clinicalremission at week 64 or disease control at week 104 showed no statistically significant differences between BEL/RTX and BEL/PBO (table 2). The most common first reason for not achieving disease control at week 104 was continuation or restart of belimumab at the investigator’s discretion (online supplemental table S2). In the ITT population, including those for whom it was the first reason for not achieving disease control, 54.8% (n=34/62) of BEL/PBO and 50.0% (n=62/124) of BEL/RTX patients continued or restarted belimumab in year 2.

Few patients achieved disease control or clinical remission that was sustained for at least 24 weeks and maintained through week 104, with no significant difference between BEL/RTX and BEL/PBO (online supplemental table S3).

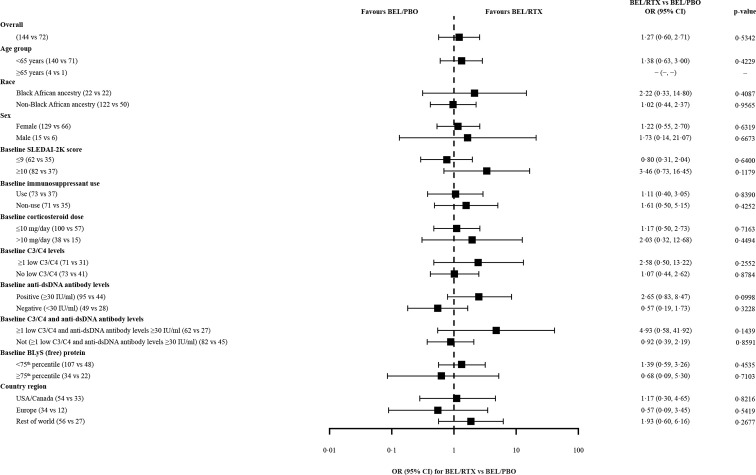

Prespecified subgroup analyses by baseline characteristics for the primary endpoint, disease control at week 52, showed no significant differences. However, there were numerically higher ORs in favour of BEL/RTX versus BEL/PBO for achieving disease control in patients with low C3/C4 levels and anti-dsDNA antibodies ≥30 IU/mL or SLEDAI-2K score ≥10 at baseline (figure 2). When analysed by baseline proteinuria (post hoc) at week 52, disease control was achieved by 18.0% (n=11/61) of BEL/PBO and 20.8% (n=25/120) of BEL/RTX patients with baseline proteinuria ≤0.5 g/24 hours (OR (95% CI) 1.21 (0.54 to 2.71), p=0.6353), and by 9.1% (n=1/11) of BEL/PBO and 12.5% (n=3/24) of BEL/RTX patients with baseline proteinuria >0.5 g/24 hours (OR (95% CI) 1.74 (0.12 to 25.15), p=0.6845).

Figure 2. Disease control* by baseline characteristics subgroups at week 52, based on IBA assessment (mITT population†; N=263). Note: OR (95% CI) and p value are from a logistic regression model with covariates: baseline SLEDAI-2K, baseline immunosuppressants, baseline prednisone-equivalent dose and treatment group (however, covariates were excluded from the corresponding subgroup models, for example, baseline SLEDAI-2K was not included in analysis by baseline SLEDAI-2K). *Disease control is defined as a SLEDAI-2K score ≤2 achieved without immunosuppressants and with a prednisone-equivalent dose of ≤5 mg/day. †mITT population excludes 29 patients from the BEL/ST group, due to IBAs being potentially unblinded. BEL, belimumab; BLyS, B-lymphocyte stimulator; C3/4, complement 3/4; IBA, independent blinded assessor; mITT, modified intention-to-treat; PBO, placebo; RTX, rituximab; SLEDAI-2K, SLE Disease Activity Index-2000; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; ST, standard therapy.

The mean duration of the longest disease control response (prespecified analysis) was significantly greater in BEL/RTX versus BEL/PBO patients through 52 weeks (adjusted treatment difference (95% CI) 47.0 (8.0 to 86.0) days, p=0.0188). Duration of disease control over 104 weeks, including the observational phase where all immunosuppression was stopped, was not significantly different between treatments (table 3). Reductions in SLEDAI-2K scores through 104 weeks were observed in all treatment groups, with a significantly larger reduction observed with BEL/RTX versus BEL/PBO (adjusted treatment difference (95% CI) −1.6 (−2.4 to –0.7), p=0.0003; online supplemental figure S2A). The odds of achieving LLDAS were not significantly different for BEL/RTX versus BEL/PBO at week 52 or 104 (online supplemental figure S2B).

Table 3. Duration of disease control,* based on PI assessment (mITT population,† N=263).

| BEL/PBO(n=72) | BEL/RTX(n=144) | BEL/ST‡(n=47) | BEL/RTX versus BEL/PBO | ||

| Adjusted treatment difference§(95% CI) | P value§ | ||||

| Duration of disease control through 52 weeks | |||||

| Number of patients with disease control Mean (SE) number of days in disease control | 3460.1 (13.46) | 72105.4 (11.53) | 3086.9 (14.51) | 47.0 (8.0 to 86.0) | 0.0188 |

| Duration of disease control through 104 weeks | |||||

| Number of patients with disease control Mean (SE) number of days in disease control | 34112.4 (24.93) | 77167.7 (19.90) | 31185.4 (33.67) | 54.5 (−15.0 to 124.1) | 0.1231 |

Disease control defined as SLEDAI-2K score ≤2 achieved without immunosuppressants and with a prednisone-equivalent dose of ≤5 mg/day; duration defined as longest period a patient maintained disease control without a break = last consecutive disease control date – first consecutive disease control date +1. Disease control non-responder status due to missing data was not considered as a break.

mITT population excludes 29 patients from the BEL/ST group, due to independent blinded assessors being potentially unblinded.

ST included corticosteroids, antimalarials, immunosuppressants and NSAIDs.

Adjusted treatment difference (95% CI), and p value are from an ANCOVA model with covariates: baseline SLEDAI-2K, baseline immunosuppressants, baseline prednisone-equivalent dose and treatment group.

ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; BEL, belimumab; mITT, modified intention-to-treat; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PBO, placebo; PI, principal investigator; RTX, rituximab; SLEsystemic lupus erythematosusST, standard therapy

Reduction from baseline in SLEDAI-2K ≥4 at week 52 by anti-dsDNA antibody and C3/C4 levels is shown in online supplemental table S4.

SLE severe flares were assessed using a modified SFI as defined. As such, through week 52, 37.5% of BEL/PBO and 36.1% of BEL/RTX patients had a severe SFI flare. Over 104 weeks, this increased to 75.0% and 64.6%, respectively (HR (95% CI) 0.81 (0.57 to 1.13), p=0.2150) (online supplemental figure S2C). The median number of days to the first severe SFI flare was 372 in the BEL/PBO group and 379 in the BEL/RTX group. In post hoc analysis of severe flares that did not impute treatment failure, 20.8% of BEL/PBO-treated patients and 15.3% of BEL/RTX-treated patients experienced severe SFI flares over 104 weeks (HR (95% CI) 0.69 (0.36 to 1.34), p=0.2745). Among these patients, the median number of days to first severe flare was 202.0 and 226.5 in the BEL/PBO and BEL/RTX groups, respectively.

Within the small number of patients with proteinuria >0.5 g/24 hours at baseline (BEL/PBO, n=11; BEL/RTX, n=24; BEL/ST, n=9), at week 52, a numerically greater proportion of BEL/RTX-treated patients versus BEL/PBO-treated patients shifted from high (>0.5 g/24 hours) to normal (≤0.5 g/24 hours), but the difference was not significant (p=0.1318; post hoc analysis; online supplemental figure S3A).

In a post hoc analysis, among patients with baseline prednisone-equivalent corticosteroid dose of >7.5 mg/day, dose reduction by ≥25% from baseline to ≤7.5 mg/day during week 40 through week 52 was observed in 50.0% (n=18/36) of BEL/PBO and 54.7% (n=41/75) of BEL/RTX patients, with no statistical difference (OR (95% CI) 1.29 (0.57 to 2.90), p=0.5379).

Biomarkers

By week 52, a decrease from baseline in IgG was observed in all groups, with the greatest decreases observed with BEL/RTX. On belimumab discontinuation from week 52, IgG levels gradually increased but remained below baseline (online supplemental figure S3B).

A significantly greater decrease in anti-dsDNA antibodies from baseline was observed with BEL/RTX versus BEL/PBO at weeks 52 (p=0.0495) and 64 (p=0.0230), but not at week 104 (p=0.2501; online supplemental figure S3C). Among anti-dsDNA antibody-positive patients at baseline (BEL/PBO, 63.6%; BEL/RTX, 71.4%), a significantly greater proportion of BEL/RTX versus BEL/PBO patients shifted to negative at week 52 only (n=18/74, 24.3% vs n=2/35, 5.7%; p=0.0186).

Increases from baseline in median C3 and C4 levels were observed in all groups, particularly BEL/RTX; levels were generally maintained above baseline during the observation phase (online supplemental figure S3D, E). Significant differences between BEL/RTX and BEL/PBO for median change from baseline were observed only for C3 levels at week 64 (p=0.0315). Among patients with low C3 levels (BEL/PBO, 43.6%; BEL/RTX, 44.8%) and those with low C4 levels (BEL/PBO, 18.2%; BEL/RTX, 32.4%) at baseline, there was no difference in the shift to normal/high levels between BEL/RTX and BEL/PBO groups.

At week 52, decreases in B cells and B-cell subsets were observed across all three groups, with significantly greater decreases observed with BEL/RTX versus BEL/PBO (p <0.0001) for all assessed B cells and B-cell subsets (online supplemental figure S4). At week 104, the only statistically significant BEL/RTX versus BEL/PBO treatment difference was for memory CD20+ CD27+ B cells (p=0.0026).

Safety

Similar proportions of patients across treatment groups experienced on-treatment AEs (year 1) and on-study AEs (years 1+2; table 4). Proportions of patients experiencing belimumab-related AEs on-study were 34.7%–38.2% across all treatment groups and study periods (table 4). Infections and infestations were the most frequently reported serious and non-serious AEs by system organ class, experienced by a higher proportion of the BEL/RTX group than other treatment groups (table 4). In year 1, serious infections and infestations occurred in eight, two and one patients in the BEL/RTX, BEL/PBO and BEL/ST groups, respectively.

Table 4. Summary of AEs and AESI for year 1 and years 1 + 2 (ITT population; N=292).

| Number of patients (%) | ||||||

| Year 1 (on-treatment*) | Year 1+2 (on-study†) | |||||

| BEL/PBO(n=72) | BEL/RTX(n=144) | BEL/ST‡(n=76) | BEL/PBO(n=72) | BEL/RTX(n=144) | BEL/ST‡(n=76) | |

| AEs, n (%) | ||||||

| Any event | 63 (87.5) | 127 (88.2) | 62 (81.6) | 63 (87.5) | 132 (91.7) | 64 (84.2) |

| AEs by SOC occurring in ≥5% of patients in any treatment group | ||||||

| Infections and infestations | 41 (56.9) | 85 (59.0) | 43 (56.6) | 44 (61.1) | 100 (69.4) | 46 (60.5) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 18 (25.0) | 38 (26.4) | 21 (27.6) | 21 (29.2) | 49 (34.0) | 24 (31.6) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 20 (27.8) | 42 (29.2) | 12 (15.8) | 21 (29.2) | 51 (35.4) | 18 (23.7) |

| Nervous system disorders | 17 (23.6) | 40 (27.8) | 14 (18.4) | 21 (29.2) | 48 (33.3) | 17 (22.4) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 18 (25.0) | 32 (22.2) | 16 (21.1) | 22 (30.6) | 40 (27.8) | 18 (23.7) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 7 (9.7) | 31 (21.5) | 7 (9.2) | 12 (16.7) | 39 (27.1) | 9 (11.8) |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 10 (13.9) | 21 (14.6) | 4 (5.3) | 10 (13.9) | 25 (17.4) | 9 (11.8) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 12 (16.7) | 20 (13.9) | 4 (5.3) | 12 (16.7) | 25 (17.4) | 6 (7.9) |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | 8 (11.1) | 17 (11.8) | 6 (7.9) | 10 (13.9) | 23 (16.0) | 9 (11.8) |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 5 (6.9) | 17 (11.8) | 8 (10.5) | 6 (8.3) | 22 (15.3) | 9 (11.8) |

| Vascular disorders | 5 (6.9) | 16 (11.1) | 6 (7.9) | 7 (9.7) | 20 (13.9) | 7 (9.2) |

| Eye disorders | 6 (8.3) | 11 (7.6) | 1 (1.3) | 6 (8.3) | 19 (13.2) | 3 (3.9) |

| Investigations | 7 (9.7) | 9 (6.3) | 4 (5.3) | 7 (9.7) | 13 (9.0) | 5 (6.6) |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 3 (4.2) | 9 (6.3) | 2 (2.6) | 5 (6.9) | 14 (9.7) | 3 (3.9) |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 3 (4.2) | 3 (2.1) | 6 (7.9) | 4 (5.6) | 6 (4.2) | 7 (9.2) |

| Cardiac disorders | 2 (2.8) | 6 (4.2) | 3 (3.9) | 2 (2.8) | 6 (4.2) | 5 (6.6) |

| Ear and labyrinth disorders | 0 (0.0) | 6 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 8 (5.6) | 1 (1.3) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 4 (5.6) | 2 (1.4) | 2 (2.6) | 4 (5.6) | 3 (2.1) | 3 (3.9) |

| AE related to BEL | 24 (33.3) | 47 (32.6) | 23 (30.3) | 25 (34.7) | 52 (36.1) | 29 (38.2) |

| AE related to RTX | 12 (16.7) | 46 (31.9) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (16.7) | 46 (31.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| AE resulting in discontinuation and/or withdrawal | ||||||

| AE resulting in BEL discontinuation | 5 (6.9) | 13 (9.0) | 3 (3.9) | 7 (9.7) | 14 (9.7) | 4 (5.3) |

| AE resulting in RTX discontinuation | 0 (0.0) | 7 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| AE resulting in study withdrawal | 2 (2.8) | 4 (2.8) | 1 (1.3) | 3 (4.2) | 6 (4.2) | 1 (1.3) |

| Serious AEs | 8 (11.1) | 25 (17.4) | 10 (13.2) | 10 (13.9) | 32 (22.2) | 15 (19.7) |

| Serious AEs by SOC occurring in ≥2% of patients in any treatment group | ||||||

| Infections and infestations | 2 (2.8) | 8 (5.6) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.8) | 13 (9.0) | 4 (5.3) |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 1 (1.4) | 3 (2.1) | 2 (2.6) | 1 (1.4) | 4 (2.8) | 2 (2.6) |

| Cardiac disorders | 2 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.6) | 2 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.9) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 4 (2.8) | 1 (1.3) |

| Vascular disorders | 1 (1.4) | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.6) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.6) |

| Nervous system disorders | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (2.6) |

| Severe AEs | 9 (12.5) | 20 (13.9) | 10 (13.2) | 10 (13.9) | 28 (19.4) | 12 (15.8) |

| AEs of special interest | ||||||

| All malignancies§ ¶ | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.3) |

| Postinjection systemic reactions | 7 (9.7) | 16 (11.1) | 3 (3.9) | 7 (9.7) | 19 (13.2) | 4 (5.3) |

| All infections of special interest§ | 4 (5.6) | 6 (4.2) | 1 (1.3) | 5 (6.9) | 12 (8.3) | 5 (6.6) |

| Serious infections of special interest§ ** | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Opportunistic infections†† | 1 (1.4) | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Active tuberculosis§ | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| All herpes zoster§ | 2 (2.8) | 5 (3.5) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.8) | 6 (4.2) | 1 (1.3) |

| Non-opportunistic herpes zoster†† | 2 (2.8) | 3 (2.1) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.8) | 4 (2.8) | 1 (1.3) |

| Opportunistic herpes zoster†† ‡‡ | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Recurrent herpes zoster†† | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Sepsis§ | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Depression (inc. mood disorders and anxiety)/suicide/self-injury | 9 (12.5) | 13 (9.0) | 4 (5.3) | 9 (12.5) | 16 (11.1) | 5 (6.6) |

| Serious depression | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Serious suicide/self-injury | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.3) |

| Suicidal behaviour | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.3) |

| Deaths | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7)§§ | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4)¶¶ | 2 (1.4)*** | 0 (0.0) |

Note: patients were counted only once in each row and column for which they have any AE meeting the criterion.

On treatment was defined as from first dose of belimumab to the latter of: last dose of belimumab+28 days or last dose of rituximab+28 days.

On study was defined as from the first dose of belimumab until the date of study completion or study withdrawal (including lost to follow-up and death).

ST included corticosteroids, antimalarials, immunosuppressants, and NSAIDs.

Per Custom MedDRA query (version 24.0).

Year 1: malignancy (stage 0 cervix carcinoma) reported in 1 patient in the BEL/ST group; year 1 + 2: malignant neoplasm (solid tumour) reported in 1 patient in each treatment group.

Opportunistic infections, herpes zoster, tuberculosis and sepsis.

Per sponsor adjudication.

Defined as non-recurrent or non-disseminated.

One death while off-treatment but on-study was reported in BEL/RTX group 94 days after the first dose of study treatment and 65 days after the most recent dose of study treatment in a patient with severe pneumonia.

The fatal SAE of cholangiocarcinoma started on study but the death occurred after the patient was withdrawn from the study. This patient also experienced another fatal SAE of septic shock that started while patient was not on study.

The fatal SAEs of pneumonia and sudden death occurred on study.

AE, adverse event; AESI, adverse events of special interest; BEL, belimumab; HZ, herpes zoster; ITT, intention-to-treat; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PBO, placebo; RTX, rituximab; SAE, serious adverse event; SC, subcutaneous; SOC, system organ class; ST, standard therapy

The incidence of infections of special interest was low, with one patient reporting sepsis in the BEL/RTX group.

Overall, 9 (12.5%) BEL/PBO-treated patients, 16 (11.1%) BEL/RTX-treated patients, and 5 (6.6%) BEL/ST-treated patients experienced psychiatric disorders of special interest and events of depression/suicide/self-injury (table 4). Suicidal behaviour was reported in one patient in each group. No completed suicides were reported. Three deaths were recorded: one in the BEL/PBO group due to cholangiocarcinoma (fatal SAE started on study, but death occurred after study withdrawal) and two on study in the BEL/RTX group (one due to pneumonia and one attributed to ‘sudden death’).

Discussion

This study addressed a novel treatment approach of adding rituximab to belimumab in patients with active SLE while investigating a rigorous withdrawal of background immunosuppressants and tapering corticosteroids. As such, BLISS-BELIEVE is the first randomised clinical trial in SLE to investigate disease control and remission off-therapy as stringent study outcomes. Similar proportions of BEL/RTX-treated and BEL/PBO-treated patients achieved disease control; therefore, the study’s primary endpoint was not met. However, the study demonstrated that disease control without immunosuppressants and low-dose corticosteroids can be achieved in 16.7%–19.4% of patients with active SLE.

Belimumab and rituximab have complementary mechanisms of action, providing an immunological rationale for their combined use,28 as supported by case reports showing improvement with belimumab either preceding rituximab in primary Sjögren’s Syndrome (pSS) or following rituximab in pSS, SLE and LN.3033 40,43 While the BEAT-LUPUS trial demonstrated a reduced risk of severe flares among patients receiving belimumab after rituximab compared with placebo after rituximab, this was not observed in the present study of belimumab and subsequent rituximab therapy. The two study designs, sizes and populations differed substantially. For example, BEAT-LUPUS, a small phase 2 trial of 52 patients with refractory SLE, incorporated less stringent corticosteroid tapering and permitted immunosuppression.32 Furthermore, the risk of severe flares was a secondary endpoint, and a different definition of severe flare was used in BEAT-LUPUS; thus, caution is required in comparing findings across the two trials.

In subgroup analyses, disease control rates at week 52 tended to numerically favour BEL/RTX versus BEL/PBO in patients with low C3/C4 and high anti-dsDNA antibody levels at baseline and in patients with baseline SLEDAI-2K score ≥10. Also, a numerically greater improvement in proteinuria was observed with BEL/RTX versus BEL/PBO in a post hoc analysis; however, these data must be interpreted with caution due to small patient numbers.

In the present study, BEL/RTX led to significant reduction in anti-dsDNA antibody levels at week 52 versus BEL/PBO corroborating the primary outcome results of anti-dsDNA antibody levels from the BEAT-LUPUS trial.32 Similarly, C3/C4 levels increased from baseline to week 104 in all treatment groups, with a trend for larger increases with BEL/RTX at both week 52 and week 104. With respect to B-cell phenotyping, B-cell subsets (such as naïve B cells) decreased within 16 weeks of belimumab treatment in our study and memory B cells rapidly increased in circulation, consistent with observations made in previous studies.44,46 More recently, the surge in circulating memory B cells following belimumab initiation has been associated with disrupted lymphocyte trafficking.34 47 As previously demonstrated, the surge of BLyS levels after rituximab treatment can be targeted by sequentially treating with belimumab and vice versa as the memory B-cell surge following initiation of belimumab can be well targeted by rituximab. It remains, however, to be established whether disrupting lymphocyte trafficking and depriving memory B cells of cell-to-cell interactions can adequately modulate memory B cell-mediated immunological processes driving pathology and/or whether depletion of circulating memory B cells is an absolute requirement to impact the pathological pathways driven by this B-cell subset. We favour the latter, as anti-dsDNA antibodies have been shown to be markedly reduced in all randomised studies of sequential therapy, regardless of the order in which belimumab and rituximab are administered.31 32 35 Significant decreases in anti-dsDNA antibody levels and increases in complement levels were observed in patients with complete depletion of B cells.48 Successful depletion of B cells was also shown to predict response to rituximab, whereas repopulation of B cells increased the risk of clinical relapse.48 Therefore, repopulation of B cells or subsets thereof (such as memory B-cells) could potentially act as an important biomarker for personalised treatment decisions when employing B-cell targeted therapies in active SLE.

Thus, the biomarker investigations as secondary outcomes of this study should prompt further studies to address whether changes seen in serological biomarkers and degree of B-cell depletion can be translated to identify a subgroup of patients with SLE that benefit the most from belimumab/rituximab combination therapy.

Safety findings were consistent with the known safety profiles of belimumab and rituximab, although incidences of AEs and serious infections and infestations, and depression were lower than in the BEAT-LUPUS phase 2 study of rituximab followed by belimumab treatment of patients with SLE.32 Comparable proportions of patients in all treatment groups experienced ≥1 AE during our study. Although incidence of serious infections and infestations was higher in the BEL/RTX group than in other treatment groups, there was no evidence of new or unexpected safety signals using the combination. Nonetheless, the benefit from sequential belimumab and rituximab treatment in any subgroup of patients will need to be balanced against risk of serious infections and infestations.

In the present study, 25.5% of BEL/ST patients achieved disease control at week 52, which was higher than either BEL/PBO or BEL/RTX patients. One could speculate that a less stringent tapering of immunosuppression in the primary comparator groups BEL/PBO and BEL/RTX could have resulted in better disease control.49 50 The patients in this study had a median disease duration of 7 years and a baseline mean daily corticosteroid dose of 10 mg/day, perhaps making them better suited to a less stringent tapering regimen, further supporting one of the important learnings of this informative study design.

This study has several limitations. Occurrence of severe SFI flare during the 2-year study period was relatively high, due partly to including the stringent study-specific definition of treatment failure (eg, corticosteroids >5 mg/day rather than 7.5 mg/day, restarting belimumab in year 2 (BEL/PBO or BEL/RTX); see online supplemental materials for full definition). Also, the BEL/ST group was included for descriptive reference only and cannot be directly compared with BEL/RTX; though, in real-world practice, belimumab is administered as an add-on to ST. The study aimed to investigate the hypothesis that combined B-cell targeting therapy would be effective without other ST. As such, the present study was not designed to reflect clinical practice accurately, and the use of less stringent tapering of IS, repetitive treatment cycles of rituximab and a comparison with continued BEL/ST would have been counterproductive to the study’s goal to achieve clinical remission off-therapy. BLISS-BELIEVE used SLEDAI-2K in our stringent efficacy outcomes, which, as a binary assessment, does not measure the improvement in symptoms, nor does it capture incomplete improvement in those symptoms. Furthermore, it is difficult to make direct comparisons between the BLISS-BELIEVE study and previous interventional SLE trials, in which response was determined by the SLE Responder Index 4 or British Isles Lupus Assessment Group-based Composite Lupus Assessment.

Primary and major secondary efficacy endpoints used IBA assessments, while other efficacy endpoints and treatment decisions were based on PI assessments. Some residual bias cannot be ruled out, as PIs were not blinded to the BEL/ST reference group.

The BLISS-BELIEVE study incorporated a unique and stringent efficacy endpoint requiring immunosuppression-free disease remission in patients with active SLE, a concept consistent with treat-to-target criteria.38 50 Although BEL/RTX treatment was not superior to BEL/PBO and the addition of rituximab to patients’ therapy did not improve disease control using the stringent outcome measures employed by this study, there were significant reductions in circulating B-cells and improvement in serological biomarkers. This warrants further investigation to determine if combination with rituximab provides better disease control for patients. Nonetheless, this large, robust study provides valuable information to clinicians to support their treatment decision-making and informs future studies into combination therapy, perhaps with less rapid immunosuppressant tapering.

supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participating patients and their families, clinicians and study investigators. Medical writing support was provided by Olga Conn, PhD, of Fishawack Indicia, UK, part of Avalere Health, and was funded by GSK.

Footnotes

Funding: This study (GSK Study 205646) was funded by GSK.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Handling editor: Josef S Smolen

Patient consent for publication: Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

Ethics approval: This study involves human participants and was approved by "Argentina: 1. Framingham Centro Medico 2. Comite de Etica en Investigacion 3. Comité Independiente de Ética Médica del Noroeste Argentino (CIEM-NOA)""Brazil: 1. CEP do Hospital Universitario Julio Muller / MT 2. Fundação Faculdade Regional de Medicina de são José do Rio Preto 3. Hospital Santa Izabel 4. Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa do Hospital Universitário da Universidade Federal de Juiz de For a""Canada: 1. Advarra Institutional Review Board 2. Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board 3. University Health Network, Research Ethics Board""France: 1. Comite de Protection des Personnes Nord-Ouest II - CHU d’Amiens Hôpital Nord ""Germany: 1. Ethik-Kommission des Fachbereichs Medizin der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität 2. Ethik-Kommission bei der Ärztekammer Hamburg 3. Ethik-Kommission der Medizinischen Hochschule Hannover 4. Ethik-Kommission der Med. Fakultaet der Christian-Albrechts-Universitaet zu Kiel""Republic of Korea: 1. IRB of Hanyang University Hospital, College of Medicine 2. IRB of Kyungpook National University Hospital 3. IRB of Chonnam National University Hospital, Clinical trial center 4. IRB of Seoul National University Hospital, Biomedical Research Institute 5. IRB of Seoul Saint Mary’s hospital 6. IRB of Inha University Hospital 7. Ajou University Hospital IRB, 5th Floor Annex building""Mexico: 1. Investigación Biomédica para el Desarrollo de Fárm 2. Hospital Centro de Especialidades Médicas CEM""Netherlands: 1. MEC-U""Russian Federation: 1. Republican Clinical Hospital 2. Local Ethics Committee of The State Educational Institution of the Highest Professional Education 3. University of Roszdrav 4. Institute of Cytology and Genetics 5. BUZ Regional Clinical Hospital 6. I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Local Ethics Committee of Federal State Autonomous Educational Institution of Higher Education 7. Chelyabinsk Regional Clinical Hospital 8. Tver Regional clinical hospital 9. Krasnoyarsk State Medical University 10. Local Ethics Committee at “Clinical Hospital #2, City Hospital #8 11. Kemerovo Regional Clinical Hospital 12. Republican Hospital nom Baranov, Ethics comitee 13. Ulyanovsk Regional Clinical Hospital 14. Local Ethics Committee at LLC Research Medical Complex ""Your Health 15. Local Ethics Committee at State Budgetary Institution of Ryazan Region ‘Regional Clinical Cardiology Dispensary 16. City Rheumatology Center, Hospital #25""Spain1. Comité Etico Hospital U. Germans Trias i Pujol""United States: 1. Advarra Institutional Review Board 2. Biomedical Research Alliance of New York, LLC, Institutional Review Board 3. WCG Institutional Review Board 4. Columbia University Medical Center, Institutional Review Board 5. Ochsner Clinic Foundation Institutional Review Board 6. NYU School of Medicine Institutional Review Board" Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Data availability free text: GSK is committed to publicly disclosing the results of GSK-sponsored clinical research that evaluates GSK medicines, and as such was involved in the decision to submit the results of this study (GSK Study 205646). Anonymised individual patient data and study documents can be requested for further research from https://www.gsk-studyregister.com/en/.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Contributor Information

Cynthia Aranow, Email: caranow@northwell.edu.

Cornelia F Allaart, Email: c.f.allaart@lumc.nl.

Zahir Amoura, Email: zahir.amoura@aphp.fr.

Ian N Bruce, Email: ian.bruce@manchester.ac.uk.

Patricia C Cagnoli, Email: pcagnoli@med.umich.edu.

Walter W Chatham, Email: wchatham@uabmc.edu.

Kenneth L Clark, Email: KenClark100@gmail.com.

Richard Furie, Email: RFurie@northwell.edu.

James Groark, Email: j_groark@comcast.net.

Murray B Urowitz, Email: m.urowitz@utoronto.ca.

Ronald van Vollenhoven, Email: r.vanvollenhoven@amsterdamumc.nl.

Mark Daniels, Email: markdaniels@doctors.org.uk.

Norma Lynn Fox, Email: normalynn@normalynn.com.

Yun Irene Gregan, Email: ireney.gregan@gmail.com.

Robert B Henderson, Email: robbie.b.henderson@gsk.com.

André van Maurik, Email: andre.x.van-maurik@gsk.com.

Josephine C Ocran-Appiah, Email: josephine.c.ocran-appiah@gsk.com.

Mary Oldham, Email: mary.x.oldham@gsk.com.

David A Roth, Email: david.a.roth@gsk.com.

Don Shanahan, Email: don.shanahan@gmail.com.

Paul P Tak, Email: tak.paulpeter@gmail.com.

Yk Onno Teng, Email: y.k.o.teng@lumc.nl.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Nikfar M, Malek Mahdavi A, Khabbazi A, et al. Long-term remission in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e13909. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dörner T, Furie R. Novel paradigms in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancet. 2019;393:2344–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30546-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fanouriakis A, Kostopoulou M, Andersen J, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus: 2023 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024;83:15–29. doi: 10.1136/ard-2023-224762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ugarte-Gil MF, Mak A, Leong J, et al. Impact of glucocorticoids on the incidence of lupus-related major organ damage: a systematic literature review and meta-regression analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Lupus Sci Med. 2021;8:e000590. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2021-000590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Vollenhoven R, Voskuyl A, Bertsias G, et al. A framework for remission in SLE: consensus findings from a large International task force on definitions of remission in SLE (DORIS) Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:554–61. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parra Sánchez AR, Voskuyl AE, van Vollenhoven RF. Treat-to-target in systemic lupus erythematosus: advancing towards its implementation. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022;18:146–57. doi: 10.1038/s41584-021-00739-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Vollenhoven R, Askanase AD, Bomback AS, et al. Conceptual framework for defining disease modification in systemic lupus erythematosus: a call for formal criteria. Lupus Sci Med. 2022;9:e000634. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2021-000634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dörner T, Kinnman N, Tak PP. Targeting B cells in immune-mediated inflammatory disease: a comprehensive review of mechanisms of action and identification of biomarkers. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;125:464–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petri M, Stohl W, Chatham W, et al. Association of plasma B lymphocyte stimulator levels and disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2453–9. doi: 10.1002/art.23678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheema GS, Roschke V, Hilbert DM, et al. Elevated serum B lymphocyte stimulator levels in patients with systemic immune-based rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1313–9. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200106)44:6<1313::AID-ART223>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang J, Roschke V, Baker KP, et al. Cutting edge: a role for B lymphocyte stimulator in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2001;166:6–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roth DA, Thompson A, Tang Y, et al. Elevated blys levels in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: associated factors and responses to belimumab. Lupus. 2016;25:346–54. doi: 10.1177/0961203315604909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.GSK Belimumab prescribing information. 2023. https://gskpro.com/content/dam/global/hcpportal/en_US/Prescribing_Information/Benlysta/pdf/BENLYSTA-PI-MG-IFU.PDF Available.

- 14.GSK Belimumab summary of product characteristics. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/benlysta-epar-product-information_en.pdf n.d. Available.

- 15.Fava A, Petri M. Systemic lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and clinical management. J Autoimmun. 2019;96:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duxbury B, Combescure C, Chizzolini C. Rituximab in systemic lupus erythematosus: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lupus. 2013;22:1489–503. doi: 10.1177/0961203313509295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merrill J, Buyon J, Furie R, et al. Assessment of flares in lupus patients enrolled in a phase II/III study of rituximab (EXPLORER) Lupus. 2011;20:709–16. doi: 10.1177/0961203310395802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rovin BH, Furie R, Latinis K, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in patients with active proliferative lupus nephritis: the lupus nephritis assessment with rituximab study. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:1215–26. doi: 10.1002/art.34359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cambridge G, Stohl W, Leandro MJ, et al. Circulating levels of B lymphocyte stimulator in patients with rheumatoid arthritis following rituximab treatment: relationships with B cell depletion, circulating antibodies, and clinical relapse. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:723–32. doi: 10.1002/art.21650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lavie F, Miceli-Richard C, Ittah M, et al. Increase of B cell-activating factor of the TNF family (BAFF) after rituximab treatment: insights into a new regulating system of BAFF production. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:700–3. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.060772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carter LM, Isenberg DA, Ehrenstein MR. Elevated serum BAFF levels are associated with rising anti-double-stranded DNA antibody levels and disease flare following B cell depletion therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2672–9. doi: 10.1002/art.38074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazarus MN, Turner-Stokes T, Chavele K-M, et al. B-cell numbers and phenotype at clinical relapse following rituximab therapy differ in SLE patients according to anti-dsDNA antibody levels. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:1208–15. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vallerskog T, Heimbürger M, Gunnarsson I, et al. Differential effects on BAFF and APRIL levels in Rituximab-treated patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther . 2006;8:R167. doi: 10.1186/ar2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pijpe J, Meijer JM, Bootsma H, et al. Clinical and histologic evidence of salivary gland restoration supports the efficacy of rituximab treatment in sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:3251–6. doi: 10.1002/art.24903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamza N, Bootsma H, Yuvaraj S, et al. Persistence of immunoglobulin-producing cells in parotid salivary glands of patients with primary sjögren’s syndrome after B cell depletion therapy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1881–7. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramwadhdoebe TH, van Baarsen LGM, Boumans MJH, et al. Effect of rituximab treatment on T and B cell subsets in lymph node biopsies of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology . 2019;58:1075–85. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones A, Muller P, Dore CJ, et al. Belimumab after B cell depletion therapy in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (BEAT lupus) protocol: a prospective multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, 52-week phase II clinical trial. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e032569. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teng YKO, Bruce IN, Diamond B, et al. Phase III, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 104-week study of subcutaneous belimumab administered in combination with rituximab in adults with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): BLISS-BELIEVE study protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e025687. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ehrenstein MR, Wing C. The baffling effects of rituximab in lupus: danger ahead? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12:367–72. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2016.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gualtierotti R, Borghi MO, Gerosa M, et al. Successful sequential therapy with rituximab and belimumab in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: a case series. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018;36:643–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraaij T, Arends EJ, van Dam LS, et al. Long-term effects of combined B-cell immunomodulation with rituximab and belimumab in severe, refractory systemic lupus erythematosus: 2-year results. Nephrol Dial Transplant . 2021;36:1474–83. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfaa117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shipa M, Embleton-Thirsk A, Parvaz M, et al. Effectiveness of belimumab after rituximab in systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1647–57. doi: 10.7326/M21-2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bela MM, Espinosa G, Cervera R. Next stop in the treatment of refractory systemic lupus erythematosus: B-cell targeted combined therapy. Lupus. 2021;30:134–40. doi: 10.1177/0961203320965707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arends EJ, Zlei M, Tipton CM, et al. Belimumab add-on therapy mobilises memory B cells into the circulation of patients with SLE. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:585. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-eular.248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Atisha‐Fregoso Y, Malkiel S, Harris KM, et al. Phase II randomized trial of rituximab plus cyclophosphamide followed by belimumab for the treatment of lupus nephritis. Arthritis Rheum . 2021;73:121–31. doi: 10.1002/art.41466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hochberg MC. Updating the American college of rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1271–7. doi: 10.1002/art.1780251101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Franklyn K, Lau CS, Navarra SV, et al. Definition and initial validation of a lupus low disease activity state (LLDAS) Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1615–21. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oon S, Huq M, Golder V, et al. Lupus low disease activity state (LLDAS) discriminates responders in the BLISS-52 and BLISS-76 phase III trials of belimumab in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:629–33. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chevalier K, Belkhir R, Seror R, et al. Efficacity of a sequential treatment by anti-CD 20 monoclonal antibody and belimumab in type II cryoglobulinaemia associated with primary sjögren syndrome refractory to rituximab alone. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:1257–9. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Vita S, Quartuccio L, Salvin S, et al. Sequential therapy with belimumab followed by rituximab in sjögren’s syndrome associated with B-cell Lymphoproliferation and overexpression of BAFF: evidence for long-term efficacy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32:490–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gandolfo S, De Vita S. Double anti-B cell and anti-BAFF targeting for the treatment of primary sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019;37 Suppl 118:199–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kraaij T, Huizinga TWJ, Rabelink TJ, et al. Belimumab after rituximab as maintenance therapy in lupus nephritis. Rheumatology . 2014;53:2122–4. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Genovese MC, Lee E, Satterwhite J, et al. A phase 2 dose-ranging study of subcutaneous tabalumab for the treatment of patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1453–60. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stohl W, Merrill JT, Looney RJ, et al. Treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus patients with the BAFF antagonist "[eptibody" blisibimod (AMG 623/A-623): results from randomized, double-blind phase 1A and phase 1B trials. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:215. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0741-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tak PP, Thurlings RM, Rossier C, et al. Atacicept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results of a multicenter, phase IB, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalating, single- and repeated-dose study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:61–72. doi: 10.1002/art.23178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dimelow R, Gillespie WR, van Maurik A. Population model-based analysis of the memory B-cell response following belimumab therapy in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2023;12:462–73. doi: 10.1002/psp4.12919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Md Yusof MY, Shaw D, El-Sherbiny YM, et al. Predicting and managing primary and secondary non-response to rituximab using B-cell biomarkers in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1829–36. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fanouriakis A, Kostopoulou M, Alunno A, et al. Update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:736–45. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Vollenhoven RF, Bertsias G, Doria A, et al. DORIS definition of remission in SLE: final recommendations from an international task force. Lupus Sci Med. 2021;8:e000538. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2021-000538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.