Abstract

Objectives

To compare medication errors identified at audit and via direct observation with medication errors reported to an incident reporting system at paediatric hospitals and to investigate differences in types and severity of errors detected and reported by staff.

Methods

This is a comparison study at two tertiary referral paediatric hospitals between 2016 and 2020 in Australia. Prescribing errors were identified from a medication chart audit of 7785 patient records. Medication administration errors were identified from a prospective direct observational study of 5137 medication administration doses to 1530 patients. Medication errors reported to the hospitals’ incident reporting system were identified and matched with errors identified at audit and observation.

Results

Of 11 302 clinical prescribing errors identified at audit, 3.2 per 1000 errors (95% CI 2.3 to 4.4, n=36) had an incident report. Of 2224 potentially serious prescribing errors from audit, 26.1% (95% CI 24.3 to 27.9, n=580) were detected by staff and 11.2 per 1000 errors (95% CI 7.6 to 16.5, n=25) were reported to the incident system. Although the prescribing error detection rates varied between the two hospitals, there was no difference in incident reporting rates regardless of error severity. Of 40 errors associated with actual patient harm, only 7 (17.5%; 95% CI 8.7% to 31.9%) were detected by staff and 4 (10.0%; 95% CI 4.0% to 23.1%) had an incident report. None of the 2883 clinical medication administration errors observed, including 903 potentially serious errors and 144 errors associated with actual patient harm, had incident reports.

Conclusion

Incident reporting data do not provide an accurate reflection of medication errors and related harm to children in hospitals. Failure to detect medication errors is likely to be a significant contributor to low error reporting rates. In an era of electronic health records, new automated approaches to monitor medication safety should be pursued to provide real-time monitoring.

Keywords: Incident reporting; Patient safety; Paediatrics; Medication safety; Medical error, measurement/epidemiology

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Hospitalised children are more likely to experience medication errors and related harm compared with adults.

It is unclear how well incident reports reflect the extent of medication errors in paediatric hospitals.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Staff detected 26% of potentially serious prescribing errors and only reported 1.1% to the incident reporting system.

Of the errors associated with actual patient harm, 82% were undetected and 90% had no corresponding incident report.

Some error types with potentially serious consequences to patients (eg, wrong patient and wrong drugs) were not reported at all.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY.

This study found incident reporting data do not provide an accurate reflection of medication errors and related harm in paediatric hospitals.

Failure to detect medication errors is likely to contribute significantly to low error reporting rates.

Effective interventions to support hospital staff in detecting and intercepting errors before they affect hospitalised children are critically needed.

Introduction

Paediatric medication errors remain one of the most important patient safety issues for children and can have lethal consequences.1 2 Evidence suggests that medication errors are more likely to occur in children than in adults and may be up to three times more likely to cause harm.3,5 Voluntary incident reporting has been used to monitor medication errors and related patient safety risks in hospitals around the world.6 7 A retrospective study of medication errors in children submitted to the US Pharmacopeia’s Medication Errors Reporting Program found that 31% of the errors were cited as harmful or fatal.8

Due to the voluntary nature of incident reporting systems, concerns have been raised about the extent to which incident reports comprehensively reflect the extent of the problem of medication errors.9 Studies have indicated staff are generally hesitant to report patient safety incidents,10 citing concerns around negative professional and legal consequences.11,16 Other reported barriers to reporting include the characteristics of the safety incident, for example, non-hazardous and frequently occurring incidents, lack of confidentiality, absence of feedback, lack of knowledge on incidents, diminished patient trust, feelings of guilt and pressure, process and systems of reporting, and absence of a patient safety culture.11 13 15 16 Paediatric-focused surveys show that paediatricians are willing to report errors to hospital incident reporting systems but identified similar barriers to reporting.17,19

A robust body of evidence has suggested that incident reporting systems only contain a small fraction of incidents occurring in practice.20,25 This is well supported by the findings of a 2015 comparative study at two Australian hospitals comparing medication errors identified from an audit of 3291 adult patient records with those reported to the hospitals’ incident reporting systems.26 Of 12 567 prescribing errors identified at audit, only 1.2 per 1000 of these prescribing errors had an incident report. However, specific studies of medication error detection and reporting by staff in children are lacking despite evidence that the causes, severity and types of errors differ from those in adults.27 28

Better understanding of incident reporting data provides insights on the potential causes and contexts of incidents, which can contribute to the development of optimal strategies to detect errors and help improve the quality of healthcare in children. In this study, we aimed (1) to examine the extent to which medication errors identified at audit and via direct observation were reported to an incident reporting system at two paediatric hospitals and (2) to investigate differences in types and severity of errors detected and reported by staff.

Methods

Study design, setting and incident reporting system

This comparison study involved two major tertiary referral paediatric hospitals in Sydney, Australia (340 and 180 beds, respectively). These two hospitals provide tertiary paediatric care to the entire state of New South Wales (8.2 million population), Australia. Both hospitals use the same incident reporting system.

Hospital staff members are required to report all identified clinical incidents, near misses and complaints to the electronic incident reporting system.29 30 Incidents are defined as any unplanned event resulting in, or with the potential for, injury, damage or other loss (including a near miss).29 Incidents may be identified at the time they occur or at any time after the event. Incidents may be identified through several methods, including direct observation, team discussion, coroner’s reports, mortality and morbidity review meetings, death review processes, staff meeting discussions, complaints, audits and/or chart reviews. Medication error is one of the main incident types and there may be more than one type of incident associated with each report. Detailed steps on how to manage incidents are stipulated for hospitals to follow after the incidents are reported.

Prescribing errors, potentially serious errors and actual harm identified at medical record audit and errors detected by hospital staff

Prescribing error data were collected retrospectively at the two study hospitals using medical chart review of patients admitted during three time periods: (1) April–July 2016, (2) June–September 2017 and (3) June–August 2020. There was a mixture of medical and surgical wards from each hospital (nine wards from hospital A and five from hospital B; see online supplemental appendix S1 for ward descriptions). Wards included from the two hospitals were broadly matched in terms of specialties. Emergency departments, intensive care units and oncology departments were excluded from the study. Chemotherapy agents were excluded in the medication chart review. Experienced clinical pharmacists independent from the study hospitals audited a total of 7785 patient records: 5123 from hospital A and 2662 from hospital B. Errors were classified into 14 different error types and rated into five severity levels of potential harm (see online supplemental appendix S2). High-risk drugs were defined by the study hospitals as anti-infectives, potassium and other electrolytes, insulin, narcotics/opioids and sedatives, heparin and other anticoagulants, and paracetamol (Sydney Children’s Hospital Network High Risk Medicine Register, 2015). In the analysis, we excluded paracetamol, which comprised 12.5% of all medications prescribed, from the high-risk drug list.

Study pharmacists recorded any documented evidence of errors being detected by hospital staff (either before or after the errors reached the patients), or evidence of actions taken in response to an error, for example, a request for additional testing or monitoring of the patient. All relevant definitions and methods of the chart review process have been published previously.31 32

Actual harm associated with prescribing errors for specific patients was assessed by a multidisciplinary harm panel, including paediatricians, paediatric nurses, pharmacists and clinical pharmacologists. The harm assessment process was conducted for a subsample of patients admitted between April and July 2016 at hospital A who experienced a potentially serious error. Panel members received a detailed case history of these patients and assessed each case independently and then discussed their assessments to reach consensus as a panel as to whether errors were associated with actual patient harm.

Medication administration error data

Medication administration error data were collected through a prospective direct observational study.31 33 The observations were conducted across nine medical and surgical wards from April to September 2016 in hospital A, excluding the emergency department, intensive care units and oncology department. A total of 298 nurses were observed. Highly trained nurse researchers watched and recorded 5137 medication doses administered to a random selection of patients. The observers collected data at different times of the day (between 07:00 and 22:00) and on all days of the week (including weekends). Nurse observers were instructed to follow a serious error protocol (see online supplemental appendix S3) in case they witnessed a potentially serious error or practice that could result in patient harm. During the study period, observers did not intervene in any medication administrations as none met the serious error protocol guidelines for intervention. Direct observational data of medications administered were compared with patients’ medication charts to identify clinical administration errors which were rated for their potential harm. This process occurred after all the observational data had been collected and was conducted by an experienced nurse, independent from the study hospital.

Medication administration errors were defined as administrations which deviated from the prescriber’s order, manufacturer’s instructions or hospital policies. Patients with a potentially serious administration error were selected for further assessment of actual harm. The same multidisciplinary harm panel reached consensus as to whether errors were associated with actual harm to patients. Further details regarding the methods have been published.33

Individual patient consent to access retrospective medication and clinical records was waived.

Data linkage and analyses

This study only included clinical medication errors (eg, wrong drug, dose, route) and excluded procedural errors (eg, illegal or unclear orders). Medication-related incident data were extracted from the hospitals’ incident reporting system for all study wards over the same time periods as the prescribing error and medication administration error data collection periods. This data extraction occurred after both audit and observational studies had finished.

The extracted incident data were reviewed by an experienced paediatric clinical pharmacist who was not involved in the audit process for prescribing errors or the observation for medication administration errors. Error types and severity were classified based on the same study protocols and double-checked by a second reviewer—another experienced paediatric clinical pharmacist independent from the study hospitals. Reported medication errors and audited/observed errors were then linked and possible matched/unmatched cases were again reviewed by the second research pharmacist to confirm agreement. If multiple errors were reported on the same incident form, all reported errors were categorised and recorded.

Incident reporting rates were calculated using the number of errors reported in incident reports divided by the total errors identified though medical record audit. Error detection rates were calculated using the number of errors with evidence of detection as the numerator. These rates are presented by hospital, error severity and error types. Separate rates are presented for errors involving high-risk medications. The Wilson score interval method was used for calculating 95% CIs. Data management was performed in SAS V.9.4 and analysis in R V.4.3.

Results

Comparison of prescribing errors, potentially serious errors and actual harm identified at audit with information reported to the hospitals’ incident reporting system

A total of 11 302 prescribing errors were identified from a review of 61 116 medication orders from 7785 patient records (table 1), which represents an overall prescribing error rate of 18.5 per 100 orders (95% CI 18.2 to 18.8). Of these errors, 19.7% (95% CI 19.0% to 20.6%, n=2224) were rated as potentially serious errors.

Table 1. Prescribing errors identified at audit, detected and reported by staff.

| Hospital | Patients | Orders audited | Errors identified at audit | Error rate per 100 orders (95% CI) | Errors detected by staff | Detection rate per 1000 errors (95% CI) | Errors reported by staff | Reporting rate per 1000 errors (95% CI) |

| All prescribing errors | ||||||||

| Hospital A | 5123 | 40 861 | 6238 | 15.3 (14.9 to 15.6) | 938 | 150.4 (141.7 to 159.5) | 26 | 4.2 (2.8 to 6.1) |

| Hospital B | 2662 | 20 255 | 5064 | 25.0 (24.4 to 25.6) | 576 | 113.7 (105.3 to 122.8) | 10 | 2.0 (1.1 to 3.6) |

| Total | 7785 | 61 116 | 11 302 | 18.5 (18.2 to 18.8) | 1514 | 134.0 (127.8 to 141.4) | 36 | 3.2 (2.3 to 4.4) |

| Potentially serious errors | ||||||||

| Hospital A | 5123 | 40 861 | 1617 | 4.0 (3.8 to 4.2) | 395 | 244.3 (224.0 to 265.8) | 20 | 12.4 (8.0 to 19.0) |

| Hospital B | 2662 | 20 255 | 607 | 3.0 (2.8 to 3.2) | 185 | 304.8 (269.5 to 342.5) | 5 | 8.2 (3.5 to 19.1) |

| Total | 7785 | 61 116 | 2224 | 3.6 (3.5 to 3.8) | 580 | 260.8 (243.0 to 279.4) | 25 | 11.2 (7.6 to 16.5) |

| All prescribing errors involving high-risk drugs | ||||||||

| Hospital A | 2906 | 5591 | 1044 | 18.7 (17.7 to 19.7) | 139 | 133.1 (113.9 to 155.1) | 7 | 6.7 (3.2 to 13.8) |

| Hospital B | 1376 | 3065 | 1277 | 41.7 (39.9 to 43.4) | 82 | 64.2 (52.0 to 79.0) | 0 | 0 (0 to 3.0) |

| Total | 4282 | 8656 | 2321 | 26.8 (25.9 to 27.8) | 221 | 95.2 (83.9 to 107.8) | 7 | 3.0 (1.5 to 6.2) |

| Potentially serious errors involving high-risk drugs | ||||||||

| Hospital A | 2906 | 5591 | 480 | 8.6 (7.9 to 9.3) | 94 | 195.8 (162.8 to 233.7) | 6 | 12.5 (5.7 to 27.0) |

| Hospital B | 1376 | 3065 | 183 | 6.0 (5.2 to 6.9) | 37 | 202.2 (150.4 to 266.9) | 0 | 0 (0 to 20.6) |

| Total | 4282 | 8656 | 663 | 7.7 (7.1 to 8.2) | 131 | 197.6 (169.1 to 229.6) | 6 | 9.0 (4.2 to 19.6) |

Of 8656 orders involving high-risk drugs, 2321 prescribing errors were identified at audit and 28.6% (95% CI 26.8% to 30.4%, n=663) of these errors were potentially serious. The prescribing error rate of orders involving high-risk drugs (26.8 per 100 orders, 95% CI 25.9 to 27.8; table 1) was higher than of orders not involving high-risk drugs (17.1 per 100 orders, 95% CI 16.8 to 17.4). High-risk drugs also had a higher potentially serious error rate than non-high-risk drugs prescribed (7.7 errors per 100 orders, 95% CI 7.1 to 8.2, vs 3.0 errors per 100 orders, 95% CI 2.8 to 3.1, respectively).

All the prescribing errors reported in the incident reports were identified through the audit. Of all errors identified at audit, only 36 had a matching incident report, equivalent to a reporting rate of 3.2 incident reports per 1000 identified errors (95% CI 2.3 to 4.4; table 1). The reporting rate was higher for potentially serious errors at 11.2 reports per 1000 errors (95% CI 7.6 to 16.5). Despite higher error rates of high-risk drugs, high-risk drug errors were reported at similar rates (3.0 incident reports per 1000 identified errors involving high-risk drugs, 95% CI 1.5 to 6.2; table 1) compared with overall errors.

The two hospitals had different prescribing error rates (table 1). However, incident reporting rates were not significantly different (hospital A: 26 incident reports for 6238 errors identified at audit, 4.2 incident reports per 1000 identified errors, 95% CI 2.8 to 6.1, vs hospital B: 10 incident reports for 5064 errors identified, 2.0 incident reports per 1000 identified errors, 95% CI 1.1 to 3.6).

During the period covered by the harm panel assessment at hospital A, 40 clinical prescribing errors identified at audit were associated with actual patient harm. Four of these errors were reported to the hospital’s incident system, a reporting rate of 10.0% (95% CI 4.0% to 23.1%).

Table 2 presents a sample of prescribing errors identified at audit with and without incident reports by error severity levels. Examples of errors associated with actual harm are also included in the table.

Table 2. Examples of prescribing errors with or without incident reports by potential severity level.

| Potential severity level | Potential severity rating* | Error description | Error type† | Reported to the hospitals’ incident reporting system (yes/no) | Actual harm level if applicable |

| Minor | 1 | Ondansetron oral disintegrating tablets prescribed with sublingual route rather than oral route. | Wrong route | No | |

| 1 | Total daily dose of valproate prescribed in three divided doses when guidelines recommend two divided doses. | Wrong frequency | No | ||

| 2 | Prescribed initial dose of vancomycin calculated to 2100 mg. Initial dose should be capped at 1500 mg. | Overdose | Yes | ||

| Potentially serious | 3 | Gentamicin once-only dose prescribed to patient using a dosing weight of 10 kg. Patient’s actual weight was 3.9 kg‡. | Overdose | Yes | Minor |

| 3 | Ibuprofen prescribed with postsurgical intravenous ketorolac. | Duplicated drug therapy | No | ||

| 3 | Patient was prescribed half the recommended treatment dose of piperacillin/tazobactam for infection‡. | Underdose | No | Moderate | |

| 4 | Insulin prescribed for a patient who does not have diabetes. | Wrong drug | No | ||

| 4 | Dose of ketamine given ‘once only’ intravenously for induction/sedation was almost three times the maximum recommended dose‡. | Overdose | No | Moderate | |

| 4 | Wrong intravenous cephalosporin prescribed, leading to errors also with dose and frequency‡. | Wrong drug | Yes | Minor | |

| 5 | Midazolam continuous infusion for seizures not ceased when new order prescribed. | Duplicated drug therapy | No | ||

| 5 | Intranasal fentanyl prescribed in milligrams instead of micrograms, creating 1000-fold overdose. | Overdose | No |

See online supplemental appendix S1Appendix Table S1 for the prescribing error potential harm severity rating scale.

See online supplemental appendix S2Appendix S2 for prescribing error type definitions.

Error associated with actual harm.

Rates of prescribing errors, potentially serious errors and actual harm detected by hospital staff at each hospital

Of 11 302 prescribing errors identified at audit, there was documented evidence that hospital staff detected 13.4% (n=1514) (table 1). The overall detection rate of potentially serious errors was 26.1% (580/2224).

The error detection rate for orders involving high-risk drugs was lower than of orders not involving high-risk drugs (9.5%, 95% CI 8.4% to 10.8%, vs 14.4%, 95% CI 13.7% to 15.1%). A similar pattern of error detection was observed for potentially serious errors (detection rate of errors involving high-risk drugs 19.8%, 95% CI 16.9% to 23.0%, vs detection rate of errors not involving high-risk drugs 28.8%, 95% CI 26.6% to 31.1%). Of 40 errors associated with actual harm, only 7 had evidence of being detected by staff (17.5%, 95% CI 8.7% to 31.9%).

Overall, staff at hospital A detected a higher proportion of prescribing errors than those at hospital B (15.0%, 95% CI 14.2% to 16.0%, vs 11.4%, 95% CI 10.5% to 12.3%; table 1). However, staff at hospital B detected more potentially serious errors than their colleagues at hospital A (30.5%, 95% CI 27.0% to 34.3%, vs 24.4%, 95% CI 22.4% to 26.6%, respectively). The two hospitals had similar error detection rates for potentially serious errors involving high-risk drugs.

There was evidence that doctors detected 40.6% of all detected errors, followed by pharmacists (17.4%) and nurses (8.7%; table 3). Similar proportions of potentially serious errors were detected by doctors (39.1%) and nurses (9.3%), while the proportion detected by pharmacists dropped to 15.9%.

Table 3. Proportion of prescribing errors detected by staff group within each hospital, n (%).

| Hospital | Doctor | Nurse | Pharmacist | Other* | Total |

| All prescribing errors | |||||

| Hospital A | 358 (38.2) | 83 (8.8) | 145 (15.5) | 352 (37.5) | 938 (100) |

| Hospital B | 256 (44.4) | 48 (8.3) | 119 (20.7) | 153 (26.6) | 576 (100) |

| Total | 614 (40.6) | 131 (8.7) | 264 (17.4) | 505 (33.4) | 1514 (100) |

| Potentially serious errors | |||||

| Hospital A | 143 (36.2) | 38 (9.6) | 57 (14.4) | 157 (39.7) | 395 (100) |

| Hospital B | 84 (45.4) | 16 (8.6) | 35 (18.9) | 50 (27.0) | 185 (100) |

| Total | 227 (39.1) | 54 (9.3) | 92 (15.9) | 207 (35.7) | 580 (100) |

| All prescribing errors involving high-risk drugs | |||||

| Hospital A | 54 (38.8) | 12 (8.6) | 11 (7.9) | 62 (44.6) | 139 (100) |

| Hospital B | 49 (59.8) | 5 (6.1) | 12 (14.6) | 16 (19.5) | 82 (100) |

| Total | 103 (46.6) | 17 (7.7) | 23 (10.4) | 78 (35.3) | 221 (100) |

| Potentially serious errors involving high-risk drugs | |||||

| Hospital A | 36 (38.3) | 10 (10.6) | 8 (8.5) | 40 (42.6) | 94 (100) |

| Hospital B | 20 (54.1) | 4 (10.8) | 4 (10.8) | 9 (24.3) | 37 (100) |

| Total | 56 (42.7) | 14 (10.7) | 12 (9.2) | 49 (37.4) | 131 (100) |

‘Other’ could be other members of staff, for example, dietitians, external healthcare providers and parent/carers. However, there was not enough information on the medication charts for our research pharmacists to determine exactly who they were.

Prescribing errors detection and reporting by error type

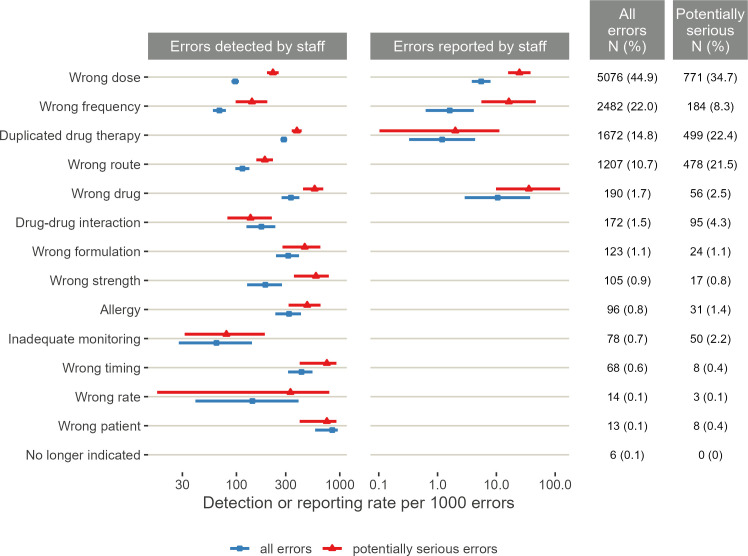

The detection rates of errors varied across the 14 error types (figure 1; the numbers related to this figure are in online supplemental appendix S4a). The majority of errors (92.3%) and potentially serious errors (86.9%) were from four error types: wrong dose, wrong frequency, duplicated drug therapy and wrong route. Among these four error types, duplicated drug therapy had the highest detection rate (28.8% of 1672 duplication errors and 38.5% of 499 potentially serious duplication errors).

Figure 1. Prescribing errors and potentially serious errors detected and reported by hospital staff by error type category. Error bars are detection rates and reporting rates per 1000 errors with 95% CI. For details, see online supplemental appendix S4a.

Only four error types were reported to the incident reporting system (figure 1). Of all error types, wrong drug errors had the highest reporting rate (10.5 reports per 1000 wrong drug errors found at audit), followed by wrong dose, wrong frequency and duplicated drug therapy.

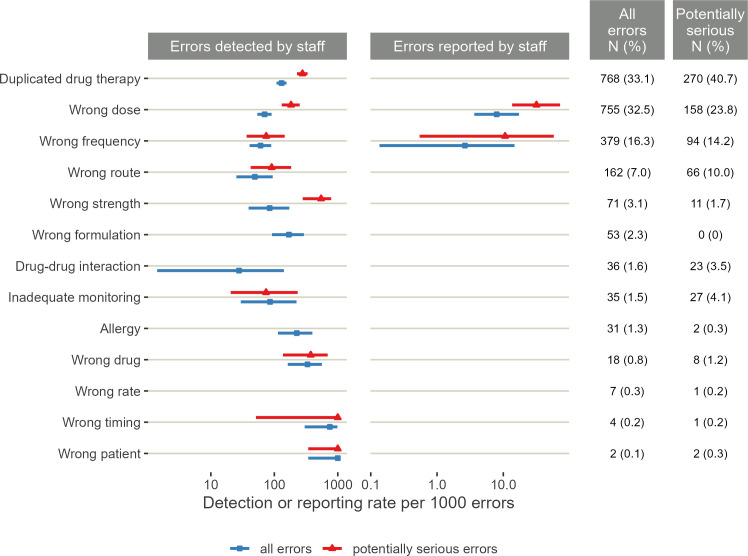

Duplicated drug therapy was the most common error type for high-risk drugs (figure 2; the numbers related to this figure are in online supplemental appendix S4b). Although the detection rate for duplication errors was the highest for all error types, none of these errors (including those rated as potentially serious errors) was reported to the hospitals’ incident reporting system. Only wrong dose and frequency errors were reported for errors involving high-risk drugs.

Figure 2. Prescribing errors and potentially serious errors involving high-risk drugs detected and reported by staff by error type. Error bars are detection rates and reporting rates per 1000 errors with 95% CI. For details, see online supplemental appendix S4b.

Comparison of medication administration errors observed with those reported to the hospitals’ incident system

A total of 2883 clinical medication administration errors were identified from a direct observational study of 5137 medication administration doses for 1530 patients. Nearly 10% of medication administrations contained at least one error with the potential for serious harm (489 drug administrations with 903 errors). There were 468 administrations involving high-risk drugs, with 28% (n=129) having errors.

Further harm assessment concluded 67 drug administrations (with 144 errors) were associated with actual patient harm. None of the 2883 medication administration errors observed, including those associated with actual harm (n=144), had an incident report.

Discussion

Of potentially serious prescribing errors identified at audit, only 1.1% were reported to the hospitals’ incident reporting system. Potentially serious prescribing errors associated with high-risk medication had an even lower incident reporting rate (0.9%). Overall, only 3 in every 1000 clinical prescribing errors identified at audit were reported to the hospitals’ incident system. A 2015 Australian study of 3291 adult patient records at two hospitals revealed remarkably similar prescribing error reporting rates (3.4 per 1000 clinical prescribing errors and 1.3% of potentially serious errors).26 Our findings provide comprehensive evidence on the limitations of incident data in paediatrics. Apart from the very low reporting rates of prescribing errors, we also found that reporting rates at the two study hospitals bear no relation to the level of error rates. In other words, a higher number of incident reports did not indicate higher actual error rates or greater risk of actual harm. Previous studies have also produced findings that suggest that incident reporting data cannot be used as a proxy measure for overall patient safety in hospitals.26 34 As qualitative research has found, many staff do not seek to report low-risk or frequent medication errors.11 13 35 Yet we also found that only a very small proportion of errors associated with actual patient harm were reported (10%, 4 out of 40 errors), suggesting these errors were either missed or intentionally not reported.

Our findings on the extent of errors detected by hospital staff are novel and help to better understand the reasons for under-reporting of prescribing errors. For only 18% of errors (7 out of 40) associated with actual patient harm was there evidence in patients’ records that the errors had been detected. In other words, five out of six serious errors that caused actual patient harm (82%) were undetected. Overall, only 13% of clinical prescribing errors identified at audit had evidence that staff had detected the errors. Although potentially serious errors were more likely to be detected (26%) than other clinical prescribing errors, three out of four of these serious errors (74%) were undetected. A previous study investigating medication errors in adult patients at two Australian hospitals found slightly lower error detection rates (12% of clinical prescribing errors and 22% of potentially serious errors).26 Our further investigation of error detection involving high-risk drugs found that only 20% of potentially serious errors were detected. Overall, our findings highlight the need for effective interventions and programmes to support hospital staff in detecting and intercepting errors before they affect patients in both adult and paediatric hospitals. In an era of electronic health records systems, greater attention needs to be paid both to improve decision support to guide safe prescribing and to automate error detection processes to improve medication safety.36 A Cochrane review illustrated that clinical decision support systems (CCDS) can improve prescribing practices and reduce medication errors by supporting discontinuation of inappropriate medication, improving the commencement of beneficial medicines and ensuring appropriate monitoring of long-term conditions and medicines.37 Given nearly half of all errors identified at audit in our study were wrong dose errors, it is encouraging that an overview of 20 systematic reviews has shown that CCDS for medication dosing assistance was the system most likely to reduce medication errors and improve patient outcomes.36

A retrospective study of medication errors in paediatric inpatients reported to the Danish national reporting system found that dosing errors were the most reported type of errors.38 Although wrong dose was the most common clinical error type detected and reported in our study, we found that the reporting rate of wrong dose errors was not different from the other three error types reported: wrong drug, frequency and duplication errors. For errors involving high-risk drugs, duplication error was the most frequent error type (including potentially serious errors), but none of these duplication errors involving high-risk drugs was reported. Furthermore, some error types (eg, wrong patient and wrong drugs) with potentially serious consequences to patients were not reported. Focused interviews or surveys would be helpful to understand why reporting rates were low for the other 8 of 14 total error types identified during audit.

Medication administration errors are more likely to impact or harm patients than prescribing errors. We found that none of the 2883 clinical medication administration errors identified during the prospective observation, including 903 errors rated as having the potential to cause patient harm, was reported by staff to the hospitals’ incident reporting system. Westbrook et al26 also found that none of 2043 medication administration errors identified across two adult hospitals was reported to the hospitals’ incident reporting systems. Importantly, our study is one of the very few that have investigated actual harm associated with medication errors. We found that none of 144 medication administration errors associated with actual patient harm was reported to the incident system.

Our study has some limitations. The error detection rates may be underestimated as evidence of error detection may not always have been recorded. However, our study examined error detection related to actual harm and potentially serious errors, that is, those with the potential to cause temporary to permanent harm to patients and may require intervention. In these cases, clinical staff are expected to document any corrections or measures taken to rectify errors, thus indicating medication error detection. The hospitals in our study are specialist children’s hospitals. The error detection rates for children in our study are likely to be higher than those from general hospitals where staff are not solely dedicated to paediatric care. Another limitation is that information about the detection of medication administration errors by staff was not collected in the prospective observation study. Lastly, the prescribing errors were reviewed retrospectively. The use of prospective data collection may have allowed for the evidence of error detection which may not be documented in patient records and thus not available during retrospective reviews.

This is the first paediatric study, to our knowledge, to investigate the extent of medication errors reported to hospital incident reporting systems. We have identified serious limitations of incident reporting, particularly under-reporting in relation to error types and those errors causing actual harm. Caution is required when interpreting incident data, especially when comparing patient risk and quality performance within or across hospitals. Open environments and reduced fear of a punitive response may increase incident reporting.34 Incident reporting is a primary patient safety data source used by hospitals to learn about and from incidents.920 24 39,41 Its strength lies not in counting harm but in the qualitative contextual and contributing factors within incident descriptions that can inform preventive and corrective strategies to reduce the occurrence of harm.25 However, a compelling evidence base has suggested that incident reporting alone does not necessarily improve patient safety or patient outcomes, as shown by a lack of improvement in patient outcome measures such as standardised mortality ratio.41 42 Multiple data sources and methodologies, for example trigger tools,43 should be considered to collect patient safety information to enable them to have a more complete picture of safety to support system-wide improvement while reducing the burden of front-line clinicians.25 41 Routinely collected data from electronic health record systems, which contain rich clinical information and medication data, have shown great potential to support medication safety.44,47 Cutting-edge analytical methods, such as natural language processing and machine learning, have been used to detect and reduce adverse drug events or to automate various medication safety tasks, such as medication reconciliation.44,46 Future work for medication safety can focus on the integration of data sources from different domains to improve the ability to identify potential adverse events more quickly and to improve clinical decision support with regard to a patient’s estimated risk for specific adverse events at the time of medication prescription or review.45 This approach has enormous potential to provide real-time, real-world evidence to guide clinical decision making.47

In conclusion, our findings show that many important medication errors are not reported and that failure to detect medication errors is likely to be a significant contributor to lower error reporting rates. Our results demonstrate that incident reporting data provide a distorted profile of medication errors and related harm occurring to children. While incident reports still play a valuable role in understanding and resolving medication safety issues, the interpretation of incident data needs careful consideration with a full understanding of its limitations. In the mean time, more reliable data sources and approaches are needed for real-time monitoring of medication safety and designing new interventions to reduce medication-related harm to our children.

supplementary material

Footnotes

Funding: This study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council, Partnership Project Grant (1094878; JIW and LL were Chief Investigators) Early Career Researcher Fellowship (MZR; 1143941), and Elizabeth Blackburn Leadership Fellowship (JIW; 117).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Data availability free text: This study used individual patient health data that cannot be shared without ethical approval. This also precludes the sharing of aggregated data sets. Analysis data sets are stored according to the ethical approval and access can only be provided to researchers who have received approval from the ethics committee.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was received from the Sydney Children’s Hospital Network Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/15/SCHN/370).

Contributor Information

Ling Li, Email: ling.li@mq.edu.au.

Tim Badgery-Parker, Email: tim.badgery-parker@mq.edu.au.

Alison Merchant, Email: Alison.Merchant@mq.edu.au.

Erin Fitzpatrick, Email: Erin.fitzpatrick@mq.edu.au.

Magdalena Z Raban, Email: magda.raban@mq.edu.au.

Virginia Mumford, Email: virginia.mumford@mq.edu.au.

Najwa-Joelle Metri, Email: j.metri@westernsydney.edu.au.

Peter Damian Hibbert, Email: peter.hibbert@mq.edu.au.

Cheryl Mccullagh, Email: Cheryl.Mccullagh@beamtree.com.au.

Michael Dickinson, Email: michael.dickinson@health.nsw.gov.au.

Johanna I Westbrook, Email: Johanna.westbrook@mq.edu.au.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

References

- 1.Carson-Stevens A, Edwards A, Panesar S, et al. Reducing the burden of iatrogenic harm in children. Lancet. 2015;385:1593–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61739-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cousins D, Clarkson A, Conroy S, et al. Medication errors in children-an eight year review using press reports. Paediatr Perinat Drug Ther. 2002;5:52–8. doi: 10.1185/146300902322125893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghaleb MA, Barber N, Franklin BD, et al. The incidence and nature of prescribing and medication administration errors in paediatric inpatients. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:113–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.158485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alenezi S, Abramson J, Smith C, et al. Interventions made by UK pharmacists to minimise risk from paediatric prescribing errors. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:e2. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311535.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaushal R, Bates DW, Landrigan C, et al. Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. JAMA. 2001;285:2114–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cottell M, Wätterbjörk I, Hälleberg Nyman M. Medication‐related incidents at 19 hospitals: a retrospective register study using incident reports. Nurs Open. 2020;7:1526–35. doi: 10.1002/nop2.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavell GF, Mandaliya D. Magnitude of error: a review of wrong dose medication incidents reported to a UK hospital voluntary incident reporting system. Eur J Hosp Pharm . 2021;28:260–5. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2019-001987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cowley E, Williams R, Cousins D. Medication errors in children: a descriptive summary of medication error reports submitted to the United States pharmacopeia. Current Therapeutic Research. 2001;62:627–40. doi: 10.1016/S0011-393X(01)80069-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macrae C. The problem with incident reporting. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:71–5. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yusuf Y, Irwan AM. The influence of nurse leadership style on the culture of patient safety incident reporting: a systematic review. Br J Health Care Manag. 2021;27:1–7. doi: 10.12968/bjhc.2020.0083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Archer S, Hull L, Soukup T, et al. Development of a theoretical framework of factors affecting patient safety incident reporting: a theoretical review of the literature. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017155. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamed MMM, Konstantinidis S. Barriers to incident reporting among nurses: a qualitative systematic review. West J Nurs Res. 2022;44:506–23. doi: 10.1177/0193945921999449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee W, Kim SY, Lee S-I, et al. Barriers to reporting of patient safety incidents in tertiary hospitals: a qualitative study of nurses and resident physicians in South Korea. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2018;33:1178–88. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naome T, James M, Christine A, et al. Practice, perceived barriers and motivating factors to medical-incident reporting: a cross-section survey of health care providers at Mbarara regional referral hospital, Southwestern Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:276. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05155-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ock M, Lim SY, Jo M-W, et al. Frequency, expected effects, obstacles, and Facilitators of disclosure of patient safety incidents: a systematic review. J Prev Med Public Health. 2017;50:68–82. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.16.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sujan M. An Organisation without a memory: a qualitative study of hospital staff perceptions on reporting and organisational learning for patient safety. Reliab Eng Syst Saf. 2015;144:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ress.2015.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garbutt J, Brownstein DR, Klein EJ, et al. Reporting and disclosing medical errors: pediatricians' attitudes and behaviors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:179–85. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rishoej RM, Hallas J, Juel Kjeldsen L, et al. Likelihood of reporting medication errors in hospitalized children: a survey of nurses and physicians. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2018;9:179–92. doi: 10.1177/2042098617746053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stratton KM, Blegen MA, Pepper G, et al. Reporting of medication errors by pediatric nurses. J Pediatr Nurs. 2004;19:385–92. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohrn A, Elfström J, Liedgren C, et al. Reporting of sentinel events in Swedish hospitals: a comparison of severe adverse events reported by patients and providers. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37:495–501. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(11)37063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bates DW, Leape LL, Petrycki S. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events in hospitalized adults. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:289–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02600138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franklin BD, O’Grady K, Paschalides C, et al. Providing feedback to hospital doctors about prescribing errors; a pilot study. Pharm World Sci . 2007;29:213–20. doi: 10.1007/s11096-006-9075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stanhope N, Crowley-Murphy M, Vincent C, et al. An evaluation of adverse incident reporting. J Eval Clin Pract. 1999;5:5–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.1999.00146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Feijter JM, de Grave WS, Muijtjens AM, et al. A comprehensive overview of medical error in hospitals using incident-reporting systems, patient complaints and chart review of inpatient deaths. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hibbert PD, Molloy CJ, Schultz TJ, et al. Comparing rates of adverse events detected in incident reporting and the global trigger tool: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2023;35:mzad056. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzad056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Westbrook JI, Li L, Lehnbom EC, et al. What are incident reports telling us? A comparative study at two Australian hospitals of medication errors identified at audit, detected by staff and reported to an incident system. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015;27:1–9. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzu098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cass H. Reducing Paediatric medication error through quality improvement networks; where evidence meets pragmatism. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:414–6. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tully MP. Prescribing errors in hospital practice. Brit J Clinical Pharma. 2012;74:668–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04313.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clinical Excellence Commission Incident management policy. 2020. https://www1.health.nsw.gov.au/pds/ArchivePDSDocuments/PD2020_019.pdf Available.

- 30.Clinical Excellence Commission Incident management. https://www.cec.health.nsw.gov.au/Review-incidents/incident-management n.d. Available.

- 31.Westbrook JI, Li L, Raban MZ, et al. Stepped-wedge cluster randomised controlled trial to assess the effectiveness of an electronic medication management system to reduce medication errors, adverse drug events and average length of stay at two paediatric hospitals: a study protocol. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011811. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Westbrook JI, Li L, Raban MZ, et al. Short- and long-term effects of an electronic medication management system on paediatric prescribing errors. NPJ Digit Med. 2022;5:179. doi: 10.1038/s41746-022-00739-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Westbrook JI, Li L, Raban MZ, et al. Associations between double-checking and medication administration errors: a direct observational study of paediatric Inpatients. BMJ Qual Saf. 2021;30:320–30. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2020-011473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howell A-M, Burns EM, Bouras G, et al. Can patient safety incident reports be used to compare hospital safety? Results from a quantitative analysis of the English national reporting and learning system data. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dirik HF, Samur M, Seren Intepeler S, et al. Nurses' identification and reporting of medication errors. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28:931–8. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jia P, Zhang L, Chen J, et al. The effects of clinical decision support systems on medication safety: an overview. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0167683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alldred DP, Raynor DK, Hughes C, et al. Interventions to optimise prescribing for older people in care homes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013:CD009095. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009095.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rishoej RM, Almarsdóttir AB, Christesen HT, et al. Medication errors in pediatric Inpatients: a study based on a national mandatory reporting system. Eur J Pediatr. 2017;176:1697–705. doi: 10.1007/s00431-017-3023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farley DO, Haviland A, Champagne S, et al. Adverse-event-reporting practices by US hospitals: results of a national survey. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:416–23. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2007.024638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farley DO, Haviland A, Haas A, et al. How event reporting by US hospitals has changed from 2005 to 2009. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21:70–7. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shojania KG. Incident reporting systems: what will it take to make them less frustrating and achieve anything useful. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2021;47:755–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2021.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frey B, Schwappach D. Critical incident monitoring in paediatric and adult critical care: from reporting to improved patient outcomes. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2010;16:649–53. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32834044d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takata GS, Mason W, Taketomo C, et al. Development, testing, and findings of a pediatric-focused trigger tool to identify medication-related harm in US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e927–35. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang Y, Yang J, Ang PS, et al. Detecting adverse drug reactions in discharge summaries of electronic medical records using Readpeer. Int J Med Inform. 2019;128:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wong A, Plasek JM, Montecalvo SP, et al. Natural language processing and its implications for the future of medication safety: a narrative review of recent advances and challenges. Pharmacotherapy. 2018;38:822–41. doi: 10.1002/phar.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Segal G, Segev A, Brom A, et al. Reducing drug prescription errors and adverse drug events by application of a probabilistic, machine-learning based clinical decision support system in an inpatient setting. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26:1560–5. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocz135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Del Rio-Bermudez C, Medrano IH, Yebes L, et al. Towards a symbiotic relationship between big data, artificial intelligence, and hospital pharmacy. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2020;13:75. doi: 10.1186/s40545-020-00276-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.