ABSTRACT

Isoniazid is an early bactericidal anti-tuberculosis (TB) agent and isoniazid mono-resistance TB is the most prevalent drug-resistant TB worldwide. Concerns exist regarding whether resistance to isoniazid would lead to delayed culture conversion and worst outcomes. From January 2008 to November 2017, adult culture-positive pulmonary TB patients receiving isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol were identified through Taiwan Center for Disease Control database and were followed until the end of 2017. Primary outcomes included time to sputum culture conversion (SCC) within two months. Secondary outcomes included death and unfavourable outcomes at the end of 2nd month. A total of 37,193 drug-susceptible and 2,832 isoniazid monoresistant pulmonary TB patients were identified. Compared with no resistance, isoniazid monoresistance was not associated with a delayed SCC (HR: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.94─1.05, p = 0.8145), a higher risk of 2-month mortality (HR: 1.19, 95% CI: 0.92─1.53, p = 0.1884), and unfavourable outcomes at 2nd month (OR: 1.05, 95% CI: 0.97─1.14, p = 0.2427). Isoniazid monoresistance was associated with delayed SCC (HR: 0.90, 95% CI: 0.83─0.98, p = 0.0099) and a higher risk of unfavourable outcomes (OR:1.18, 95% CI: 1.05─1.32, p = 0.0053) in patients aged between 20 and 65, and delayed SCC in patients without underlying comorbidities (HR: 0.90, 95% CI: 0.81─0.98, p = 0.0237). Isoniazid mono-resistant TB had a comparable outcome with drug-susceptible TB at the end of the intensive phase. Healthy, and non-elderly patients were more likely to had culture persistence, raising concerns about disease transmission in these subgroups and warranting early molecular testing for isoniazid resistance.

KEYWORDS: Drug-susceptible, isoniazid resistance, mortality, sputum culture conversion, tuberculosis

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) continues to be an important global infectious disease with a substantial disease burden and high mortality rate. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) report, it was estimated that 10.6 million individuals were diagnosed with TB in 2021, representing a 4.5% increase compared to the previous year [1]. This sudden reversal in the declining trend is concerning. Drug-resistant TB (DR-TB) poses a significant challenge to effective treatment, and isoniazid monoresistant TB (HR-TB) is the most common form of DR-TB. It was estimated in a recent meta-analysis that the global prevalence of HR-TB was 7.4% among new TB patients and 11.4% among previously treated TB patients [2]. Addressing the issue of HR-TB is crucial to achieving better global TB control.

HR-TB deserves special attention due to its association with worse treatment outcomes [3]. In a meta-analysis, adverse treatment outcomes including relapse or failure, and acquired drug resistance were 15% and 3.6% for patients with HR-TB, compared with 4% and 0.6% for drug-susceptible TB [3]. Additionally, HR-TB is a precursor to and is associated with emergence of multidrug resistance (MDR). It was estimated that as high as 8% HR-TB patients developed MDR during their treatment [3]. Given these findings, early diagnosis, prompt treatment, and effective measures to prevent the transmission are of great importance in addressing the challenges posed by HR-TB.

While line probe assays such as GenoType MTBDRplus (Hain Lifescience, Nehren, Germany) have been endorsed by WHO for detecting isoniazid and rifampicin resistance among smear-positive or culture-positive specimens to replace phenotypic testing and in meta-analysis the sensitivity and specificity of detecting isoniazid resistance compared with phenotypic method is high, their use in direct testing among all TB suspects is still not widely adopted due to concerns of sensitivity especially in smear-negative specimens [4,5]. Unlike rifampicin drug resistance, which can be rapidly detected using molecular methods such as the Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra assay, isoniazid resistance is typically unknown until results of conventional culture-based drug susceptibility testing are available. Unfortunately, obtaining these results can take weeks after collecting sputum mycobacterial cultures [6]. This delay in identifying isoniazid resistance can lead to adverse outcomes and TB dissemination, particularly among vulnerable patients.

Currently, there is limited knowledge regarding the specific group of patients who are more likely to experience worse outcomes when facing isoniazid resistance. Considering that isoniazid is an important anti-TB agent known for its early bactericidal effects, it is intriguing to investigate whether resistance to isoniazid prolongs the time required for sputum culture conversion under standard anti-TB treatment [7]. The recommended regimen for treating isoniazid monoresistant TB has changed as evidence showed that the addition of a fluoroquinolone to at least 6 months of daily rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide was associated with better outcomes [8]. As a result, the WHO endorsed a regimen of 6 months of fluoroquinolone, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide [9]. It is possible that resistance to isoniazid could hinder the initial bactericidal effects of the treatment, leading to delayed culture conversion. The persistence of mycobacterial culture is a significant factor that influences the transmission and contagiousness of TB. This is because the development of TB disease requires at least one viable Mtb droplet nucleus to reach the lung alveolar macrophage [10]. Therefore, culture persistence plays a crucial role in disease transmission.

The objective of our study is to investigate the impact of isoniazid monoresistance on sputum culture conversion and unfavourable outcomes within the initial two-month period. Additionally, we aim to identify specific at-risk groups that may experience worse outcomes compared to patients with isoniazid-susceptible TB. By doing so, we hope to identify patients who would benefit from more intensive therapy, close monitoring, and use of rapid molecular testing methods to detect isoniazid resistance. The findings of this study may help develop targeted strategies for managing isoniazid monoresistant TB cases.

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

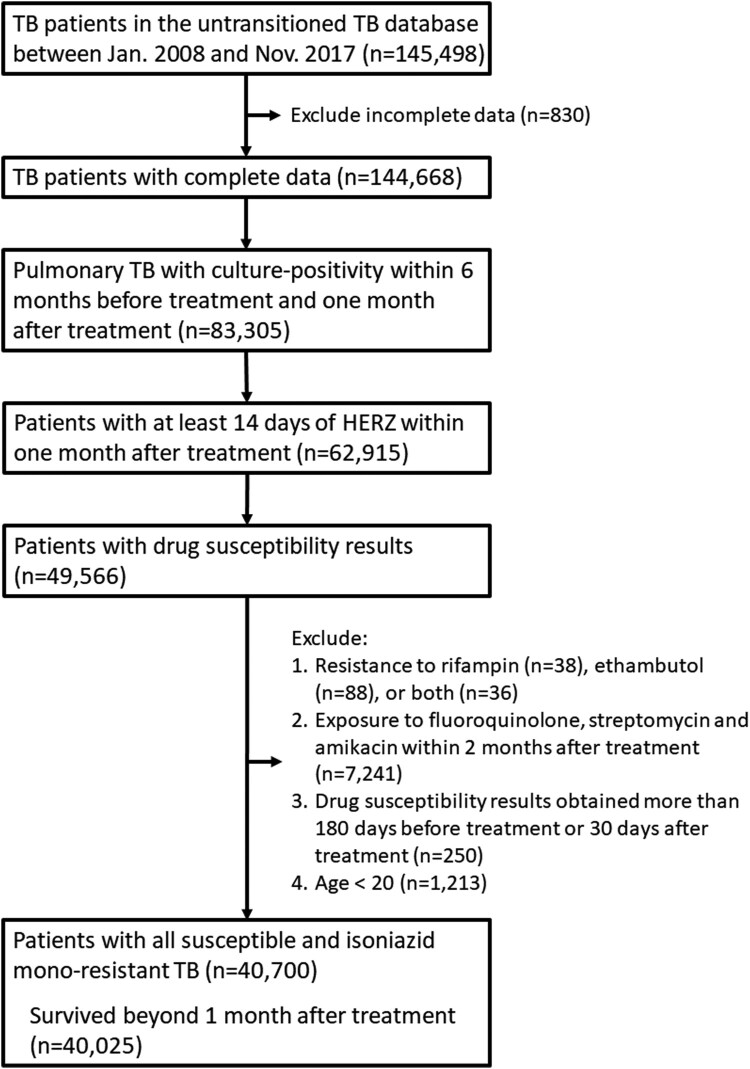

We recruited adults (age ≥20) in Taiwan who were culture-positive pulmonary TB patients between January 2008 and November 2017. Eligible participants were either all susceptible or had isoniazid monoresistant TB and had received at least 14 days of treatment with isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol within one month after treatment. Among them, those who exposed to fluoroquinolone, streptomycin, and amikacin within 2 months after treatment were excluded. For the main study, we included patients who survived after the first month of treatment (Figure 1). To recruit this cohort, we utilized the Taiwan Center for Disease Control (CDC) un-transitioned TB database, which is an internal database maintained by the Taiwan CDC. It is important to note that this database is distinct from the Taiwan TB transitioned database, which has been previously used in various studies and has provided valuable insights [11,12]. The un-transitioned TB database contains information primarily derived from the clinical practices of the Taiwan's public health and medical systems, focusing on individual TB patients. It includes crucial details such as body weight of the patient, the drug susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex to first-line anti-TB medications (isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol), the results of sputum acid-fast smear and mycobacterial cultures before and after TB treatment, and treatment supervision (directly observed therapy, short course [DOTs]). These specific variables were not available in the TB transitioned database or the Taiwan Health Insurance Research Database. By utilizing the un-transitioned TB database, we have access to comprehensive and detailed information that allows for a more in-depth analysis of the impact of isoniazid resistance on treatment outcomes and culture conversion within the initial two-month time frame. Moreover, it is important to note that tuberculosis (TB) is a notifiable disease in Taiwan, meaning that the maintenance of the TB database is mandatory. As a result, the CDC un-transitioned TB database we utilized for this study is comprehensive and includes data from all reported TB cases in Taiwan. To improve the available information for analysis, the CDC linked the un-transitioned TB database to the Taiwan Health Insurance claims database. This linkage allowed us to obtain additional data on the underlying comorbidities of the TB patients. Taiwan has a single payer health insurance system with a coverage rate approaching 100%, providing extensive healthcare coverage for the population (source: https://www.nhi.gov.tw/) [11,13]. Additionally, the mortality data used in our study were obtained from the Department of Statistics in Taiwan. This ensures accurate and reliable information regarding the mortality rates associated with TB cases.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of case selection HERZ, isoniazid, ethambutol, rifampicin, pyrazinamide; TB, tuberculosis.

Data collection and definition

In the Taiwan CDC un-transitioned TB database, isoniazid monoresistance was identified and classified based on the level of resistance. First-line anti-TB drug susceptibility testing (DST) was conducted at quality-assured laboratories that actively participated in a proficiency testing programme organized by the Reference Laboratory of Mycobacteriology at the Taiwan CDC [14]. Briefly, M. tuberculosis isolates were subjected to drug susceptibility testing using the proportion method with solid media. Isoniazid monoresistance was defined as resistance to isoniazid and documented susceptibility to rifampicin and ethambutol. Resistance was defined as 1% of the colonies growing in the presence of the following critical concentrations of drugs (low-level isoniazid: 0.2 μg/ml, high-level isoniazid 1 µg/mL) [15]. The Reference Laboratory of Mycobacteriology provides guidance, quality control materials, and training to the participating laboratories, ensuring that standardized protocols and procedures for DST are followed [14].

The definition of urban and non-urban areas in Taiwan followed previous publication [16]. Hospital level was determined based on the hospital's accreditation level with the highest number of visits in the first two months before beginning treatment.

Outcome definition

In this study, there were two primary outcomes and two secondary outcomes. Primary outcomes were time to sputum culture conversion (SCC) and no positive cultures after 2nd month. Secondary outcomes were death within two months and unfavourable outcomes at 2nd month.

Sputum culture conversion (SCC) is defined as the negativity of three consecutive sputum samples. The date of the first of the three samples being plated is considered as the date of SCC. An unfavourable outcome in the second month assessment point was defined as the occurrence of patient mortality within the initial 2-month treatment period, loss of follow-up, or failure to achieve SCC. No positive cultures after 2nd month were defined as the absence of any positive TB culture after 2nd month (after 60 days).

Statistical analysis

In this study, we used descriptive statistics to summarize the demographic, clinical, and radiographic characteristics of TB patients. For continuous variables, means were calculated, while proportions were used for categorical variables. To compare differences between groups, we used an independent-sample t-test for continuous variables and a chi-squared test for categorical variables. In the logistic regression analysis, we examined the association between isoniazid resistance and no positive cultures after 2nd month and unfavourable outcomes at the 2nd month. Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to assess the association between isoniazid resistance and time to SCC and survival within 2 months. Additionally, competing risk analysis was also performed for time to SCC using death as the competing risk. Sensitivity analysis was performed by not excluding those who died within one month. For adjustment, we put either isoniazid only (isoniazid mono-resistant vs. all susceptible) or isoniazid low-level and high-level resistance (isoniazid low-level resistant vs. isoniazid high-level resistant vs. all susceptible) in the multivariable models. Subgroup analyses were conducted for different age groups, sex, smear results, body weight, and patients without comorbidities. All data analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). A significance level of p < 0.05, determined by a two-sided test, was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics

During the study period (2008–2017), there were 144,668 pulmonary TB patients. There were 83,305 (57.6%) patients with culture-positivity and among them, 62915 (75.5%) received at least 14 days of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. Overall, 49,566 (78.8%) had drug susceptibility results. After excluding resistance to either ethambutol or rifampicin (n = 162), previous exposure to fluoroquinolone, streptomycin, or amikacin (n = 7241), not categorized within all susceptible, low-dose INH resistance or high-dose resistance (n = 250), aged less than 20 (n = 1213), a total of 40,700 pulmonary TB patients were identified. Among them, 675 died within one month after TB treatment, and the remaining 40,025 pulmonary TB patients were included in the main analysis.

Among them, 92.9% (n = 37,193) had drug-susceptible TB, and 7.1% (n = 2,832) had HR-TB. The median age was 64 years old (mean ± standard deviation [SD], 62.2 ± 18.9) among all susceptible TB and 62 years old (mean ± SD, 61.8 ± 18.1, p = 0.2618) among HR-TB. There was a male predominance among all susceptible (n = 26645, 71.6%) and HR-TB (n = 2010, 71.0%, p = 0.4492). Among the 2,832 HR-TB patients, 51.0% (n = 1,443) had low-level isoniazid resistance, and 49.0% (n = 1,389) had high-level isoniazid resistance.

Compared to patients with drug-susceptible TB, those with HR-TB were more likely to have cavitary lesions (21.2% vs. 19.5%, p = 0.0291), smear-positive results (56.2% vs. 54.0%, p = 0.0237), and less likely to have extrapulmonary lesions (5.7% vs. 7.2%, p = 0.0025). When comparing isoniazid high-level resistance with low-level resistance, patients with low-level resistance tended to be younger (60.7 ± 17.9 vs. 63.1 ± 18 years old, p = 0.0004), have cavitary lesions (23.5% vs. 18.7%, p = 0.0019), and were less likely to be under the service of a chest/infectious disease subspecialty (84.1% vs. 87.3%, p = 0.0154). There was also a trend towards smear positivity in patients with low-level resistance, although it did not reach statistical significance (57.7% vs. 54.6%, p = 0.0983). The detailed demographic data are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data of participants.

|

Overall n = 40025 (100%) |

DS-TB n = 37193 (92.9%) |

HR-TB n = 2832 (7.1%) |

LL HR-TB n = 1443 (3.6%) |

HL HR-TB n = 1389 (3.5%) |

P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS vs. LL HR vs. HL HR |

DS vs. HR |

LL HR vs. HL HR |

||||||

| Age (year) | 62.2 ± 18.9 | 62.2 ± 18.9 | 61.8 ± 18.1 | 60.7 ± 17.9 | 63.1 ± 18.1 | 0.0019 | 0.2618 | 0.0004 |

| ≥20 & < 65 | 20497 (51.2) | 18976 (51.0) | 1521 (53.7) | 818 (56.7) | 703 (50.6) | <0.0001 | 0.0003 | 0.0003 |

| ≥65 & < 85 | 15536 (38.8) | 14451 (38.9) | 1085 (38.3) | 534 (37.0) | 551 (39.7) | |||

| ≥85 | 3992 (10.0) | 3766 (10.1) | 226 (8.0) | 91 (6.3) | 135 (9.7) | |||

| Female sex | 11370 (28.4) | 10548 (28.4) | 822 (29.0) | 435 (30.2) | 387 (27.9) | 0.3031 | 0.4492 | 0.1807 |

| Cavity | 7838 (19.6%) | 7239 (19.5) | 599 (21.2) | 339 (23.5) | 260 (18.7) | 0.0006 | 0.0291 | 0.0019 |

| Smear-positivity | 21683 (54.2) | 20091 (54.0) | 1592 (56.2) | 833 (57.7) | 759 (54.6) | 0.0200 | 0.0237 | 0.0983 |

| Extra-pulmonary | 2839 (7.1) | 2678 (7.2) | 161 (5.7) | 78 (5.4) | 83 (6.0) | 0.0086 | 0.0025 | 0.5125 |

| Weight (Kg) | 56.3 ± 11.2 | 56.3 ± 11.2 | 56.0 ± 11.2 | 55.9 ± 11.0 | 56.0 ± 11.5 | 0.2601 | 0.1023 | 0.8776 |

| >20 & ≤ 40 | 1945 (4.9) | 1794 (4.8) | 151 (5.3) | 65 (4.5) | 86 (6.2) | 0.7562 | 0.4555 | 0.0383 |

| >40 & ≤ 70 | 33128 (82.8) | 30801 (82.8) | 2327 (82.2) | 1210 (83.9) | 1117 (80.4) | |||

| >70 | 4952 (12.4) | 4598 (12.4) | 354 (12.5) | 168 (11.6) | 186 (13.4) | |||

| Highly urbanized area | 6685 (16.7) | 6199 (16.7) | 486 (17.2) | 248 (17.2) | 238 (17.1) | 0.7934 | 0.4970 | 0.9709 |

| Pulmonary disease | ||||||||

| COPD | 5839 (14.6) | 5422 (14.6) | 417 (14.7) | 201 (13.9) | 216 (15.6) | 0.4633 | 0.8313 | 0.2235 |

| Asthma | 3017 (7.5) | 2791 (7.5) | 226 (8.0) | 117 (8.1) | 109 (7.9) | 0.6297 | 0.3549 | 0.7980 |

| Bronchiectasis | 1488 (3.7) | 1380 (3.7) | 108 (3.8) | 56 (3.9) | 52 (3.7) | 0.9439 | 0.7796 | 0.8490 |

| Pneumoconiosis | 430 (1.1) | 385 (1.0) | 45 (1.6) | 23 (1.6) | 22 (1.6) | 0.0224 | 0.0059 | 0.9830 |

| Systemic disease | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 14122 (35.3) | 13123 (35.3) | 999 (35.3) | 510 (35.3) | 489 (35.2) | 0.9970 | 0.9931 | 0.9388 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 9988 (25.0) | 9241 (24.9) | 747 (26.4) | 386 (26.8) | 361 (26.0) | 0.1727 | 0.0695 | 0.6464 |

| Dyslipidemia | 5215 (13.0) | 4837 (13.0) | 378 (13.4) | 198 (13.7) | 180 (13.0) | 0.7279 | 0.6019 | 0.5509 |

| Coronary arterial disease | 4379 (10.9) | 4063 (10.9) | 316 (11.2) | 148 (10.3) | 168 (12.1) | 0.2721 | 0.7004 | 0.1203 |

| Cancer | 3432 (8.6) | 3217 (8.7) | 215 (7.6) | 100 (6.9) | 115 (8.3) | 0.0672 | 0.0526 | 0.1753 |

| Congestive heart failure | 2165 (5.4) | 2000 (5.4) | 165 (5.8) | 79 (5.5) | 86 (6.2) | 0.4174 | 0.3086 | 0.4156 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1917 (4.8) | 1775 (4.8) | 142 (5.0) | 67 (4.6) | 75 (5.4) | 0.5419 | 0.5615 | 0.3565 |

| End-stage renal disease | 460 (1.2) | 431 (1.2) | 29 (1.0) | 14 (1.0) | 15 (1.1) | 0.7804 | 0.5165 | 0.7719 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 432 (1.1) | 397 (1.1) | 35 (1.2) | 18 (1.3) | 17 (1.2) | 0.7036 | 0.4029 | 0.9549 |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 256 (0.6) | 240 (0.7) | 16 (0.6) | 10 (0.7) | 6 (0.4) | 0.5987 | 0.6053 | 0.3542 |

| Psoriasis | 192 (0.5) | 175 (0.5) | 17 (0.6) | 6 (0.4) | 11 (0.8) | 0.2203 | 0.3353 | 0.1952 |

| HIV | 160 (0.4) | 155 (0.4) | 5 (0.2) | 5 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0511 | 0.0509 | 0.0625 |

| PAOD | 130 (0.3) | 121 (0.3) | 9 (0.3) | 6 (0.4) | 3 (0.2) | 0.6446 | 0.9458 | 0.5078 |

| Hospital accreditation level | ||||||||

| Medical centre | 15427 (38.5) | 14419 (38.8) | 1008 (35.6) | 515 (35.7) | 493 (35.5) | 0.0015 | 0.0002 | 0.6760 |

| Regional hospital | 17576 (43.9) | 16220 (43.7) | 1356 (47.8) | 684 (47.4) | 672 (48.4) | |||

| Local hospital | 4717 (11.8) | 4409 (11.9) | 308 (10.9) | 166 (11.5) | 142 (10.2) | |||

| Other | 2305 (5.8) | 2145 (5.8) | 160 (5.7) | 78 (5.4) | 82 (5.9) | |||

| Chest or ID specialist | 34407 (86.0) | 31982 (86.0) | 2425 (85.6) | 1213 (84.1) | 1212 (87.3) | 0.0434 | 0.5942 | 0.0154 |

DS-TB, drug-susceptible tuberculosis; HL, high-level; HR-TB, isoniazid mono-resistant tuberculosis; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ID, infectious disease; LL, low-level; PAOD, peripheral arterial occlusive disease;

Within the two months, a total of 854 (2.1%) patients had died. At the 2-month mark, SCC was not achieved in 10,834 (27.1%) of the patients. Therefore, 11,687 patients (29.2%) had an unfavourable outcome at the 2nd month.

Rate and volume of sputum culture examinations

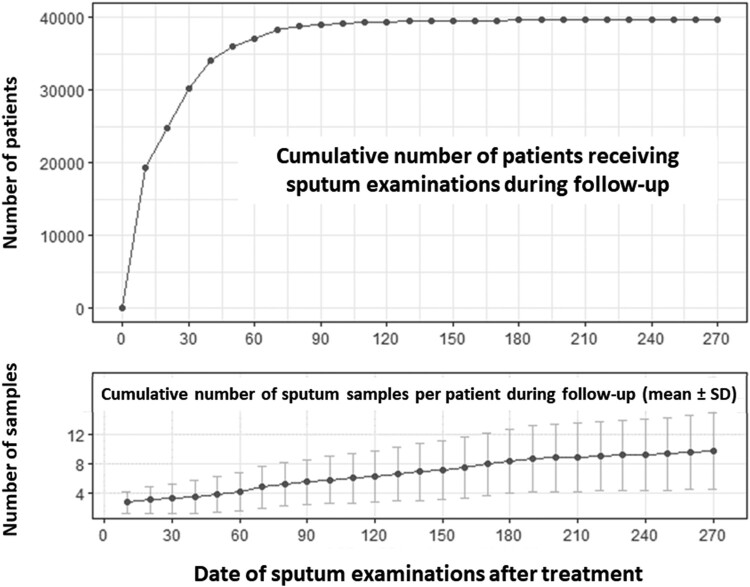

Before treatment, sputum samples were examined in 92.64% of patients. All patients had their sputum samples examined within the first month of treatment. During the first month, a cumulative total of 30,245 patients (75.6%) underwent follow-up sputum cultures, and in the 2nd month, 37,098 patients (92.7%) had follow-up sputum culture performed. By the 6th month, 39,652 patients (99.1%) had undergone follow-up sputum mycobacterial culture (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of participants who received sputum examinations before and after treatment.

Furthermore, by the end of the first month of treatment, participants had a median of 3 sputum samples collected (mean ± SD, 3.2 ± 2.1 samples). At second month, participants had a median of 4 sputum samples collected (mean ± SD, 4.1 ± 2.7 samples). Figure 2 illustrates the proportion of participants who received sputum examinations before and after treatment.

Association between isoniazid resistance and outcomes

Cox regression model for time to SCC

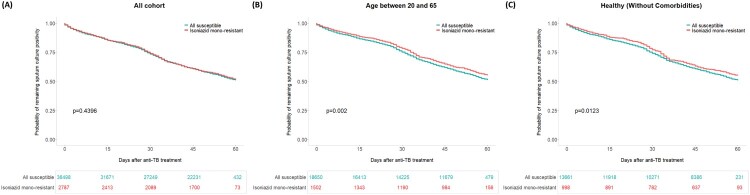

In multivariable Cox regression analysis, neither isoniazid resistance nor the level of isoniazid resistance was found to be associated with the time to SCC within 2 months (1. Adjusted with isoniazid resistance only, isoniazid resistance, adjusted hazard ratio [aHR]: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.94─1.05, p = 0.8145; 2. Adjusted for isoniazid low-level resistance and high-level resistance, isoniazid low-level resistance, aHR: 1.02, 95% CI: 0.95─1.10, p = 0.5898; isoniazid high-level resistance, aHR: 0.97, 95% CI: 0.89─1.04, p = 0.3811, Table 2). The factors associated with the time to SCC in primary analysis and sensitivity analysis, with or without competing risk analysis are illustrated in Supplementary Table 1. The Kaplan-Meier curve of time-to-culture conversion in the overall cohort is illustrated in Figure 3A.

Table 2.

Association between isoniazid resistance and different clinical outcomes.

| Outcome | Model | Isoniazid resistance | Isoniazid resistance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| low-level | high-level | |||||||||

| ES* | 95% CI | p value | ES* | 95% CI | p value | ES* | 95% CI | p value | ||

| Time to Sputum culture Conversion | CR | 0.99 | 0.94─1.05 | 0.8145 | 1.02 | 0.95─1.10 | 0.5898 | 0.97 | 0.89─1.04 | 0.3811 |

| No positive cultures after 2nd month | LR | 0.96 | 0.88─1.05 | 0.3398 | 1.00 | 0.88─1.12 | 0.9468 | 0.92 | 0.82─1.04 | 0.1858 |

| 2-month survival | CR | 1.19 | 0.92─1.53 | 0.1884 | 1.36 | 0.97─1.90 | 0.0731 | 1.02 | 0.70─1.49 | 0.9114 |

| Unfavorable Outcome at 2nd Month | LR | 1.05 | 0.97─1.14 | 0.2427 | 1.03 | 0.92─1.16 | 0.6017 | 1.07 | 0.95─1.21 | 0.2428 |

Models were adjusted for isoniazid resistance, age, sex, body weight, cavitation, smear positivity, extrapulmonary tuberculosis, income, marriage status, urbanization, comorbidities, hospital accreditation level and doctor specialty.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval; CR, cox regression; ES, effect size; LR, logistic regression

* ES (effect size) represents hazard ratio in cox regression and odds ratio in logistic regression.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves of time to sputum culture conversion among all cohort (A), participants aged between 20 and 65 (B) and healthy participants (C).

Logistic regression model for no positive cultures after 2nd month

In multivariable logistic regression analysis for no positive cultures after 2nd month, neither isoniazid resistance nor the level of isoniazid resistance was found to be associated with no positive cultures after 2nd month (1. Adjusted with isoniazid only, isoniazid resistance, adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 0.96, 95% CI: 0.88─1.05, p = 0.3398; 2. adjusted with low- and high-level isoniazid resistance, isoniazid low-level resistance, aOR: 1.00, 95% CI: 0.88─1.12, p = 0.9468; isoniazid high-level resistance, aOR: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.82─1.04, p = 0.1858, Table 2). Factors associated with no positive cultures after 2nd month in the primary analysis and sensitivity analysis are illustrated in Supplementary Table 2.

Cox regression model for mortality within two months

In multivariable Cox regression analysis, isoniazid resistance was not found to be associated with the worst survival within two months (adjusted for isoniazid only, isoniazid resistance, aHR: 1.19, 95% CI: 0.92─1.53, p = 0.1884). However, isoniazid low-level resistance showed a borderline association with a higher risk of death within two months (adjusted for isoniazid low-level resistance and high-level resistance, isoniazid low-level resistance, aHR: 1.36, 95% CI: 0.97─1.90, p = 0.0731; isoniazid high-level resistance, aHR: 1.02, 95% CI:0.70─1.49, p = 0.9114, Table 2). Factors associated with mortality within two months in primary analysis and sensitivity analysis are illustrated in Supplementary Table 3.

Logistic regression model for unfavourable outcomes at 2nd month

In multivariable logistic regression analysis for unfavourable outcomes in the 2nd month, neither isoniazid resistance nor the level of isoniazid resistance was found to be associated with unfavourable outcomes (isoniazid resistance, aOR: 1.05, 95% CI: 0.97─1.14, p = 0.2427; isoniazid low-level resistance, aOR: 1.03, 95% CI: 0.92─1.16, p = 0.6017; isoniazid high-level resistance, aOR: 1.07, 95% CI: 0.95─1.21, p = 0.2428). Factors that were identified to be associated with unfavourable outcomes in the 2nd month in the analysis and sensitivity analysis are summarized in Supplementary Table 4.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis adjusted isoniazid resistance for SCC

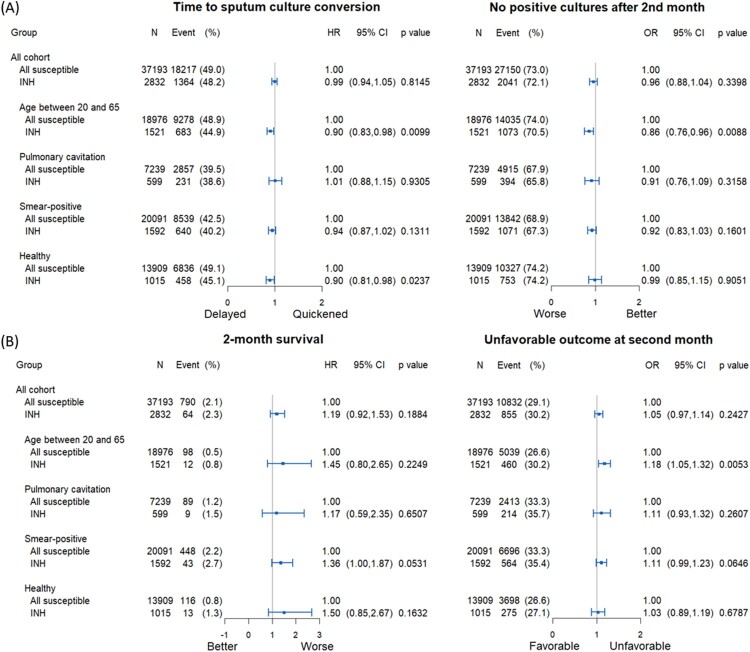

The Kaplan-Meier curves of time to SCC among individuals aged between 20 and 65 years and healthy patients are illustrated in Figure 3. In the Cox regression analysis, isoniazid resistance was associated with a longer time to SCC among individuals aged between 20 and 65 years old (aHR: 0.90, 95% CI: 0.83─0.98, p = 0.0099) and healthy patients (without comorbidities) (aHR: 0.90, 95% CI: 0.81─0.98, p = 0.0237) (Figure 4A, left panel). Among individuals aged 20-65, isoniazid resistance was less likely to achieve sputum culture conversion in 2nd month (aOR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.76─0.96, p = 0.0088) (Figure 4A, right panel).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of subgroup analysis on time to sputum culture conversion within two months and no positive cultures after 2nd month (A) and on 2-month survival and unfavourable outcome at 2nd month (B).

Subgroup analysis adjusted isoniazid resistance for survival and unfavourable outcome

Isoniazid resistance was not associated with the worst 2-month survival among the abovementioned 4 subgroups (Figure 4B, left panel), but was associated with a higher risk of unfavourable outcome in 2nd month in patients aged between 20 and 65 (aOR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.05─1.32, p = 0.0053) (Figure 4B, right panel).

Subgroup analysis adjusted isoniazid low- and high-level resistance for SCC

Isoniazid low-level resistance was associated with a longer time to SCC among individuals aged between 20 and 65 years old (aHR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.79─0.98, p = 0.0197), whereas isoniazid high-level resistance was associated with a longer time to SCC among healthy patients (without comorbidities) (aHR: 0.83, 95% CI: 0.73─0.96, p = 0.0097) (Supplementary Figure 1). Also, individuals aged 20–65 with low-level isoniazid resistance were less likely to achieve SCC within 2 months (aOR: 0.82, 95% CI: 0.70–0.95, p = 0.0105) (Supplementary Figure 1).

Subgroup analysis adjusted isoniazid low- and high-level resistance for survival and unfavourable outcome

Isoniazid low-level resistance was associated with a worse 2-month survival in smear-positive patients (aHR: 1.60, 95% CI:1.06─2.40, p = 0.0235) and a higher likelihood of unfavourable outcomes at the 2nd month in patients aged between 20 and 65 (aOR: 1.24, 95% CI: 1.06─1.44, p = 0.0066) (Supplementary Figure 2).

Discussion

Our large-scale population-based cohort demonstrated that isoniazid monoresistance was not associated with sputum culture conversion or unfavourable outcomes at the 2-month after treatment, as compared to fully susceptible tuberculosis. However, upon closer examination of subgroups, we discovered a greater likelihood of delayed culture conversion among younger patients and those without comorbidities. Moreover, when comparing low-level and high-level isoniazid resistance, we found that low-level resistance was more commonly associated with adverse outcomes across various metrics.

Our study has several strengths. Its population-based design resulted in a large number of patients, making it one of the largest cohorts ever described in the literature. Additionally, the database for un-transitioned TB contains detailed information on sputum mycobacterial examinations, results, and drug susceptibility. In Taiwan, the diagnosis and treatment of TB are fully funded by the National Health Insurance programme, supplemented further by additional contributions from the Taiwan CDC [14]. Taiwan has achieved excellent performance in TB control. Taiwan's impressive success in TB control is evidenced by the notification rate of all TB forms, which dropped from 67.4 per 100,000 populations in 2006 to 30.1 per 100,000 populations in 2022 (https://monitor.cdc.gov.tw/). The cooperation between the public health system and the medical system provided a solid background for our studies.

In a previous study that looked at household contacts with different drug susceptibility patterns of the index case, it was discovered that household contacts of index cases with isoniazid monoresistance were at a higher risk of TB infection compared to cases of drug-susceptible TB [17]. Additionally, genetic variations such as the katG S315 T or inhA promoter mutation have been linked to TB transmission. Strains carrying these mutations are more likely to spread [18]. In our study, we failed to detect a difference in sputum conversion between isoniazid monoresistant TB and drug-susceptible TB. This may be due to the fact that common mutations in isoniazid resistance are not associated with an increase in virulence or reproductive ability [19,20]. We, however, observed that isoniazid monoresistance was associated with delayed culture conversion in specific patient groups.

Furthermore, we found that low-level isoniazid resistance was associated with a higher risk of delayed culture conversion and adverse outcomes. Interestingly, low-level isoniazid-resistant-TB cases were more likely to exhibit cavitation and have positive sputum smears. Additionally, previous studies have suggested that specific gene mutations (e.g. KatG and/or inhA) in isoniazid resistance can have different impacts on patient outcomes [21,22]. The higher virulence of isoniazid low-level resistance compared to high-level resistance may also be due to the genetic mutations involved. Importantly, while some may assume that low-level isoniazid resistance indicates lower virulence due to the low MIC level, our findings suggest that low-level isoniazid resistance should still be given special attention.

The findings that younger patients and those without comorbidities with isoniazid monoresistant TB tend to have delayed culture conversion compared with drug-susceptible TB are interesting. While comparing the impact of isoniazid resistance on outcomes between isoniazid monoresistant TB and drug-susceptible TB, a possible explanation is that among patients with more intact immune status, drug resistance is more likely to contribute to a significant difference in culture conversion time than among patients with impaired immune status. This aligns with the aim of this study, which calls for more rapid molecular testing to detect isoniazid resistance to facilitate early and more effective treatment regimens. Interestingly, in multidrug-resistant TB patients, delayed culture conversion has also been observed among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative patients compared with HIV-positive patients [23,24]. The interaction between the immune system and drug-resistant TB may be complex and somewhat counterintuitive.

The findings indicating that middle-aged and young adults were associated with delayed culture conversion are of particular significance and warrant special attention. Previous research, including a systematic review and meta-analysis, has indicated that a considerable proportion of TB transmission occurs at the community level rather than within households [25]. Additionally, several studies have demonstrated that young adults are more likely to experience loss to follow-up in TB treatment [26]. Because, middle-aged individuals and young adults are often actively working and socially engaged, they may have a higher potential for community-level TB transmission. The results of our study, which indicate that this population is at higher risk for delayed culture conversion, suggest that testing for isoniazid resistance may be beneficial in preventing TB transmission among middle-aged and young adults.

In a study conducted in the United Kingdom, whole genome sequencing (WGS) showed faster results for drug susceptibility testing compared to traditional phenotypic tests [27]. This approach was particularly effective in identifying isoniazid resistance. Most treatment modifications resulting from WGS were related to isoniazid resistance [27]. In another retrospective cohort study in France, molecular detection of isoniazid resistance on an initial sample was independently associated with a shorter time to adequate treatment [28]. Additionally, risk factors associated with isoniazid-resistant TB are not efficient in effectively screening isoniazid-resistant TB [29]. The systematic implementation of rapid molecular testing on clinical samples remains the only effective way to make early diagnoses of HR-TB [29].

At present, there is no point-of-care test commercially available that is specifically designed to detect isoniazid resistance. Some line probe assays, such as MTBDRplus (Hain Lifescience, Nehren, Germany) were designed to detect isoniazid resistance, but were limited by their requirement for specialized facilities and exhibited low sensitivity in smear-negative specimens [4]. Widely used tests, such as Xpert MTB/RIF and Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, USA), can detect rifampicin resistance by targeting the rpoB gene mutation [30]. However, these tests do not directly detect isoniazid resistance, which is an important aspect of TB management. Our study emphasizes the significance of rapid molecular methods for detecting isoniazid resistance. The recently introduced Xpert MTB/XDR (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, USA) assay may offer a potential solution to this issue. According to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, the Xpert MTB/XDR assay has shown a pooled sensitivity of 94.2% and a specificity of 98.5% for detecting isoniazid resistance [31]. Although caution is still warranted due to the limited number of detected resistance variants in specific genes, [31] early diagnosis of isoniazid-resistant TB using the Xpert MTB/XDR assay could be beneficial in implementing more intensive and targeted management strategies for patients with isoniazid-resistant TB.

While our study focused on the short-term (two-month) outcome of isoniazid monoresistance, the long-term treatment outcome is equally important. A meta-analysis comparing isoniazid monoresistant TB to drug-susceptible TB (the same comparator used in our study) found that isoniazid monoresistance was associated with a higher risk of treatment failure and acquired drug resistance when using first-line drugs [3]. More recent studies largely support the conclusion that isoniazid monoresistant TB carries a higher risk of unfavourable outcomes compared to drug-susceptible TB [32,33]. However, a recent case–control study conducted in France presented contrasting results. This study found no significant difference in treatment success rates between isoniazid monoresistant and drug-susceptible TB. Notably, in this French study, fluoroquinolone was added among a majority of isoniazid monoresistant TB patients (56 out of 99, or 56.6%) [29] This aligns with the aim of our study, which emphasizes the importance of early identification of drug resistance and the implementation of optimal treatment regimens.

Although our study provides valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations. The study design was retrospective, which could introduce biases and limitations. The follow-up of sputum mycobacterial culture was not standardized, and there may be variations in the timing and frequency of culture collection among participants. However, it is important to note that a substantial proportion of patients (75.6% within one month and 92.7% within two months) underwent follow-up sputum culture, and the participants had a median of four sputum specimens by the end of the second month. This high rate and volume of follow-up sputum cultures help mitigate the potential weaknesses associated with the retrospective design. Secondly, our study did not consider the specific impact of anti-TB treatment on the outcomes observed. During the study period, the recommended treatment for isoniazid-resistant TB in Taiwan followed certain guidelines, including the use of rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol, with or without isoniazid, while fluoroquinolones were not suggested during that time. Therefore, the potential impact of these drugs on treatment outcomes was of less concern in our study. Additionally, we did not assess long-term follow-up data to evaluate the impact of isoniazid resistance on the long-term prognosis of patients. Instead, we evaluated the outcome at the 2nd month, which may better reflect the impact of rapid bactericidal effect of isoniazid. Lastly, we did not have information on pyrazinamide resistance in our databases, as drug susceptibility testing for pyrazinamide is not routinely performed in clinical practice.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study findings suggest that there is no significant correlation between isoniazid monoresistance and unfavourable outcomes two months after treatment. However, we have identified specific patient groups who are at a higher risk for delayed culture conversion and adverse outcomes compared to those with drug-susceptible tuberculosis. These high-risk groups include younger patients and those being previously healthy. These findings emphasize the importance of targeted interventions and close monitoring for these at-risk individuals to ensure timely culture conversion and improved treatment outcomes. Additionally, the development and implementation of rapid molecular testing methods for isoniazid resistance can help identify patients who may need more intensive therapy and closer follow-up.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Taiwan Center for Disease Control for establishing the un-transitioned TB database, and to the Department of Statistics for maintaining and linking the Health Insurance Database.

Funding Statement

This study is funded by the National Taiwan University Hospital Hsin-Chu branch (109-HCH019). The funder had no role in the study design and manuscript writing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Author contributions

M.-R. L., J.-Y. W. and L.-T. K. conceptualized the study. M.-R. L., L.-T. K., J.-H. C.,C.-H.L. and J.-Y. W. was responsible for the data curation. M.-R. L. M.-C. L and L.-T. K. analyzed the data. L.-T. K. was responsible for funding acquisition. M.-R. L., L.-T. K. and J.-Y. W. investigated and collected the data. J.-Y. W., L.-T. K., M.-R. L and J.-H. C. designed the study. J.-Y. W., M.-C. L. and C.-H. L. supervised the study processing. M.-R. L., L.-T. K., J.-H. C., C.-H.L., M.-C. L. and J.-Y. W. wrote the original draft. M.-R. L., J.-Y. W. and L.-T. K. wrote, reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics statement

The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of National Taiwan University Hospital Hsin-Chu Branch (IRB number: 108-058-E). Informed consent was waived because the study utilized an encrypted database and did not pose any additional risk to participants.

References

- 1.Bagcchi S. Who's global tuberculosis report 2022. Lancet Microbe. 2023;4:e20. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(22)00359-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dean AS, Zignol M, Cabibbe AM, et al. Prevalence and genetic profiles of isoniazid resistance in tuberculosis patients: a multicountry analysis of cross-sectional data. PLoS Med. 2020;17:e1003008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gegia M, Winters N, Benedetti A, et al. Treatment of isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis with first-line drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(2):223–234. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30407-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nathavitharana RR, Cudahy PG, Schumacher SG, et al. Accuracy of line probe assays for the diagnosis of pulmonary and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(1):1601075. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01075-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis: Module 3: diagnosis - rapid diagnostics for tuberculosis detection. Geneva2020.

- 6.Opota O, Mazza-Stalder J, Greub G, et al. The rapid molecular test Xpert MTB/RIF ultra: towards improved tuberculosis diagnosis and rifampicin resistance detection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25(11):1370–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vilcheze C, Jacobs WR Jr. The isoniazid paradigm of killing, resistance, and persistence in mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Mol Biol. 2019;431(18):3450–4361. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fregonese F, Ahuja SD, Akkerman OW, et al. Comparison of different treatments for isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(4):265–275. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30078-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO treatment guidelines for isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis: Supplement to the WHO treatment guidelines for drug-resistant tuberculosis. Geneva2018. [PubMed]

- 10.Migliori GB, Nardell E, Yedilbayev A, et al. Reducing tuberculosis transmission: a consensus document from the world health organization regional office for Europe. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(6):1900391. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00391-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee MR, Lee MC, Chang CH, et al. Use of antiplatelet agents and survival of tuberculosis patients: a population-based cohort study. J Clin Med. 2019;8(7):923. doi: 10.3390/jcm8070923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen JH, Lee CH, Lee MR, et al. Bisphosphonate use is not associated with tuberculosis risk among patients with osteoporosis: a nationwide cohort study. J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;62(11):1412–1418. doi: 10.1002/jcph.2090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee MR, Yu KL, Kuo HY, et al. Outcome of stage IV cancer patients receiving in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a population-based cohort study. Sci Rep. 2019;9:9478. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45977-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu MC, Chiang CY, Lee JJ, et al. Treatment outcomes of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Taiwan: tackling loss to follow-up. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(2):202–210. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SJ. Drug-susceptibility testing in tuberculosis: methods and reliability of results. Eur Respir J. 2005;25(3):564–569. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00111304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu CY, Huang YT, Chuang YL, et al. Incorporating development stratification of Taiwan townships into sampling design of large scale health interview survey. J Health Manag. 2006;4(1):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Becerra MC, Huang CC, Lecca L, et al. Transmissibility and potential for disease progression of drug resistant mycobacterium tuberculosis: prospective cohort study. Br Med J. 2019;367:l5894. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gagneux S, Burgos MV, DeRiemer K, et al. Impact of bacterial genetics on the transmission of isoniazid-resistant mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2(6):e61. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pym AS, Saint-Joanis B, Cole ST.. Effect of katG mutations on the virulence of mycobacterium tuberculosis and the implication for transmission in humans. Infect Immun. 2002;70(9):4955–4960. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.9.4955-4960.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nieto RL, Mehaffy C, Creissen E, et al. Virulence of mycobacterium tuberculosis after acquisition of isoniazid resistance: individual nature of katG mutants and the possible role of AhpC. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0166807. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Velayutham B, Shah V, Mythily V, et al. Factors influencing treatment outcomes in patients with isoniazid-resistant pulmonary TB. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2022;26(11):1033–1040. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.21.0701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antonenko Kate OKVI, Antonenko PB.. Mutations leading to drug-resistant mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in Ukraine. Cent Eur J Med. 2010;5:30–35. doi: 10.2478/s11536-009-0114-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shibabaw A, Gelaw B, Wang SH, et al. Time to sputum smear and culture conversions in multidrug resistant tuberculosis at University of Gondar hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0198080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abebe M, Atnafu A, Tilahun M, et al. Determinants of sputum culture conversion time in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients in ALERT comprehensive specialized hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2024;19(5):e0304507. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0304507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez L, Shen Y, Mupere E, et al. Transmission of mycobacterium tuberculosis in households and the community: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185(12):1327–1339. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laycock KM, Enane LA, Steenhoff AP.. Tuberculosis in adolescents and young adults: emerging data on TB transmission and prevention among vulnerable young people. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2021;6(3):148. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed6030148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park M, Lalvani A, Satta G, et al. Evaluating the clinical impact of routine whole genome sequencing in tuberculosis treatment decisions and the issue of isoniazid mono-resistance. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22:349. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07329-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bachir M, Guglielmetti L, Tunesi S, et al. Molecular detection of isoniazid monoresistance improves tuberculosis treatment: a retrospective cohort in France. J Infect. 2022;85(1):24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2022.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bachir M, Guglielmetti L, Tunesi S, et al. Isoniazid-monoresistant tuberculosis in France: risk factors, treatment outcomes and adverse events. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;107:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.03.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horne DJ, Kohli M, Zifodya JS, et al. Xpert MTB/RIF and Xpert MTB/RIF ultra for pulmonary tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;6:CD009593. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009593.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pillay S, Steingart KR, Davies GR, et al. Xpert MTB/XDR for detection of pulmonary tuberculosis and resistance to isoniazid, fluoroquinolones, ethionamide, and amikacin. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;5:CD014841. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014841.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Araújo-Pereira M, Arriaga MB, Carvalho ACC, et al. Isoniazid monoresistance and antituberculosis treatment outcome in persons with pulmonary tuberculosis in Brazil. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2024;11(1):ofad691. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofad691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karo B, Kohlenberg A, Hollo V, et al. Isoniazid (INH) mono-resistance and tuberculosis (TB) treatment success: analysis of European surveillance data, 2002 to 2014. Euro Surveill. 2019;24:1800392. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.12.1800392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.