Abstract

Aims Effects of insulin and ascorbic acid on expression of Bcl-2 family proteins and caspase-3 activity in hippocampus of diabetic rats were evaluated in this study. Methods Diabetes was induced in Wistar male rats by streptozotocin (STZ). Six weeks after verification of diabetes, the animals were treated for 2 weeks with insulin or/and ascorbic acid in separate groups. Hippocampi of rats were removed and evaluation of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Bax proteins expression in frozen hippocampi tissues were done by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and blotting. The Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Bax proteins bands were visualized after incubation with specific antibodies using enhanced chemiluminescences method. Caspase-3 activity was determined using the caspase-3/CPP32 Fluorometric Assay Kit. Results Diabetic rats showed increase in Bax protein expression and decrease in Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL proteins expression. The Bax/Bcl-2 and Bax/Bcl-xL ratios were found higher compared with non-diabetic control group. Treatments with insulin and/or ascorbic acid were resulted in decrease in Bax protein expression and increase in Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL proteins expression. The Bcl-2/Bax and Bcl-xL/Bax ratios were found higher in treated groups than untreated diabetic group. Caspase-3 activity level was found higher in diabetic group compared with non-diabetic group. Treatment with insulin and ascorbic acid did downregulated caspase-3 activity. Conclusions Our data provide supportive evidence to demonstrate the antiapoptotic effects of insulin and ascorbic acid on hippocampus of STZ-induced diabetic rats.

Keywords: Diabetes, Insulin, Ascorbic acid, Hippocampus, Apoptosis, Rat-Caspase-3, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Bax

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic, debilitating, and often deadly disease that affects all races in the world. It is estimated that there are 177 million cases of diabetes. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) report, the number of diabetics in the world is likely to increase more than twofold by 2030 (Khookhor et al. 2007).

Diabetes mellitus is a heterogenic metabolic disorder in which the body does not make enough insulin and characterized by hyperglycemia and alterations in fat and protein metabolism resulting from impaired insulin secretion, resistance to insulin action, or both (Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus 2003). The occurrence of a specific set of microvascular, neurologic complications, and renal failure has been reported with hyperglycemia (Biessels et al. 1998). Long-term complications of diabetes can damage the eyes, kidneys, nervous system, and cardiovascular systems (Greene et al. 1999).

Researchers have recently concluded that diabetes affect the central nervous system and specially hippocampus as a specific target that is associated with memory, learning, and other cognitive functions (Biessels et al. 1998). It has been reported that the number of cases with disorders in these functions are more in diabetic population (Li et al. 2002a, b; Sima et al. 1988). It has been suggested that the hippocampus of diabetic animals is extremely susceptible to additional stressful events following impairment of glucose utilization, which in turn can lead to irreversible hippocampal damage (Reagan et al. 1999).

The neurodegenerative mechanisms resulted by diabetes in hippocampus have not been recognized clearly.

In different studies, it has been shown that change in insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptor expression, decrease in glucocorticoids receptors, decrease in insulin transmitters, and apoptosis induction may resulted in neurodegenerative mechanisms (Sima et al. 1988).

Apoptosis is executed through a suicide program that is common in diabetes and degenerative central nervous system disorders. It has been revealed that apoptosis implicated in several neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Kam and Ferch 2000). It has been claimed to be a prominent phenomenon in diabetic neuropathy (Saraste and Pulkki 2000).

Apoptosis could be proposed as a possible mechanism for hyperglycemia-induced hippocampal neuronal cell death (Sima et al. 1988).

Several factors are contributed in apoptosis, but the key elements are categorized in two main families of proteins including caspase enzymes and Bcl-2 family. Caspase enzymes are working as a cascade and caspase 3 is the most important member of this family that has an effective role in neurons of central nervous system (Thornberry and Lazebnik 1998).

The second family, Bcl-2 family is a set of cytoplasmic proteins members that regulate apoptosis. The two main groups of this family, Bcl-2, and Bax proteins are functionally opposed: Bcl-2 acts to inhibit apoptosis, whereas Bax counteracts this effect (Ashkenazi and Dixit 1998; Kroemer 1997).

It has been reported that insulin might be able to counteract cognitive impairments resulting from diabetes (Biessels et al. 1998). The inhibitory effects of insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) on apoptosis of oligodendrocytes, epithelial, and cancerous cells were shown (Barres et al. 1992; Brownlee et al. 1988).

In addition, it has been mentioned the oxidative stress has a possible role in development of complications in diabetes and using of antioxidants such as ascorbic acid can reduce these complications (Desco et al. 2002; Sima et al. 1988).

The aim of this work was to investigate the effect of the insulin and ascorbic acid in diabetic rats on the Caspase-3 activity and Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Bax proteins levels.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Thirty male adult Wistar rats weighting 200–250 g (8–10 weeks old) were used for this study. The animals were housed in the animal care facility of Bu-Ali research Institute in a temperature-controlled room (23 ± 2°C) with a 12–12 h light–dark cycle with free access to food and water.

Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats

Diabetes was induced in overnight fasted rats by a single intraperitoneal injection of 60 mg/kg body weight of streptozotocin (STZ) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in 0.5 ml normal saline. Control rats were injected with normal saline alone.

Animals presenting blood glucose values >250 mg/dl 3 days after STZ injection were enrolled in the diabetic group.

Blood samples were taken from the tail vein. The blood glucose concentration and weight of animals were recorded weekly. The blood glucose concentration was measured with Glucometer equipment (Bioname, UK).

Treatment Regimens

The treatment of animals was conducted 6 weeks after the verification of diabetes as is shown in Table 1. Four to six units of insulin protamin (NPH) (EXIR Pharmaceutical Company, Borujerd, Iran) was delivered subcutaneously (SC). l-Ascorbic acid, 200 mg/kg (Darou Pakhsh Distribution Company, Tehran, Iran) was injected intraperitoneally (IP). Injections were carried out daily for 2 weeks.

Table 1.

The treatment of animals with insulin and/or ascorbic acid 6 weeks after the verification of diabetes was done in separate groups of rats

| Group | Diabetic | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| C | − | Normal saline |

| D | + | Normal saline |

| I | + | Insulin protamin (NPH) |

| AA | + | Ascorbic acid |

| I + AA | + | Insulin + ascorbic acid |

Tissue Collection

Animals were anesthetized with chloroform. The whole brain was removed and placed on an ice-cooled cutting board. After the meninges were removed, the hemispheres were bisected and hippocampus were dissected, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −70°C for extraction of protein.

Evaluation of Bcl-2, Bcl-Xl, and Bax Expression in Frozen Hippocampal Tissues

The expression of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Bax proteins were analyzed by western blotting in hippocampal tissues of rats (Bar-Am et al. 2005). Tissues collected were homogenized with ice-cold homogenizing buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.5 mM Triton X-100, pH 7.4) containing protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche, Germany). Bio-Rad protein assay was used for determining protein concentration. Protein lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE (12.5%) under reducing conditions and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, USA). Blotted membranes were treated using the Attoglow western blot system and incubated with Millennium Enhancer (BioChain, Hayward, CA, USA). Briefly blotted membranes were blocked with blocking buffer (5% skimmy milk powder in PBS). After blocking, blots were incubated with anti-Bcl-2 polyclonal antibody (1/500, v/v), anti-Bcl-xL polyclonal antibody (1/1000, v/v), and anti-Bax polyclonal antibody (1/250, v/v) (Biovision, USA) for 20 h at 4°C, separately. After four times washing with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated-secondary antibody (1/5000, v/v, Biochain, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. The Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Bax protein bands were exposed to autoradiography film and were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescences (ECL) method (Bioimaging System, Syngene, UK). Quantification of the results was accomplished by measuring the optical density of the labeled bands, using the computerized imaging program Kodack-1D (USA).

Measurement of Caspase-3 Activity

Caspase-3 activity was determined using the caspase-3/CPP32 Fluorometric Assay Kit (K105) purchased from BioVision, Inc. (Mountain View, CA, USA). For each assay, 50 μg of tissue cell lysate was used. Samples were read in a fluorimeter equipped (Jasco, FP-6200, Japan) with a 400-nm excitation and a 505-nm emission filter. Fold-increase in caspase-3 activity was determined by comparing fluorescence of 7-amino-4-trifluoromethyl courmarin in control and treated hippocampus with STZ.

Statistical Analyses

The data were analyzed using SPSS, version 11.5. One-way ANOVA, Tukey and T Student tests were performed. A probability level of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Body Weight and Plasma Glucose Levels

Blood glucose level was significantly increased in diabetic untreated rats compared with control rats (P < 0.001).

Diabetic rats showed a significant reduction in body weight (P < 0.01) over the experimental period of this study. At the 6th week, the difference between these groups was significant (P < 0.01). After treatment the weight of treated rats in groups I and I + AA were higher than group D significantly (P < 0.01).

The blood glucose level of diabetic rats treated in groups I and I + AA were lower than the blood glucose level in untreated diabetic rats, group D (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristic parameters of the control and STZ-diabetic rats

| Parameter | Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | D | I | AA | AA + I | |

| Initial body weight(g) | 243.75 ± 9.25 | 247.08 ± 19.08 | 213.40 ± 10.10 | 205.25 ± 11.30 | 198.30 ± 13.04 |

| Final body weight(g) | 306.00 ± 10.40 | 198.17 ± 21.04* | 237.08 ± 12.70** | 219.50 ± 19.30** | 224.00 ± 17.20** |

| Initial blood glucose(mg/dl) | 109.40 ± 5.60 | 106.90 ± 6.30 | 479.40 ± 23.30 | 472.75 ± 32.00 | 496.25 ± 31.60 |

| Final blood glucose(mg/dl) | 111.25 ± 1.30 | 477.10 ± 28.40* | 111.25 ± 11.20** | 483.17 ± 26.90 | 118.30 ± 11.50** |

* P < 0.01 versus control group (C)

** P < 0.01 versus diabetic group (D)

Analysis of Bcl-2, Bcl-Xl, and Bax Proteins Expression in Frozen Hippocampal Tissues

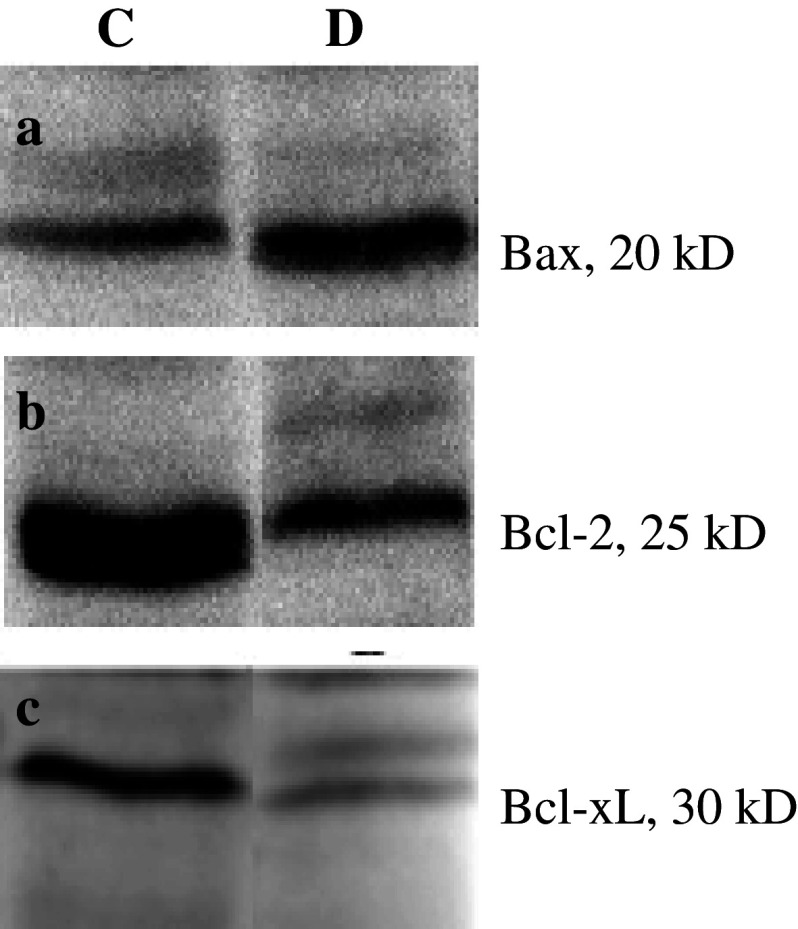

The level of expression of Bax in group D showed increase significantly compared with group C (Fig. 1a), but the levels of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL were found lower in group D than group C (Fig. 1b, c).

Fig. 1.

Analysis of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Bax proteins expression in frozen hippocampi of rats groups C (Control) and D (Diabetic) by western blotting. (a) Bax gene expression, the level of expression of Bax in group D showed increase significantly compared with group C, (b) Bcl-2 gene expression, and (c) Bcl-xL gene expression, the levels of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL were found lower in group D than group C

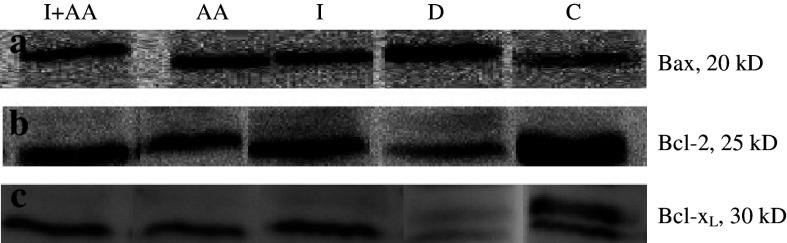

These levels for Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL in groups I, AA, and I + AA were detected higher than group D, but these differences between mentioned groups were not different significantly (Fig. 2b, c).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Bax proteins expression in frozen hippocampi of rats groups C (Control), D (Diabetic), I (treated with insulin), AA (treated with ascorbic acid), and I + AA (treated with insulin + ascorbic acid) by western blotting. (a) Bax gene expression, the level of expression of Bax in groups I, AA, and I + AA showed decrease significantly compared with group D, (b) Bcl-2 gene expression, and (c) Bcl-xL gene expression, the levels of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL were found higher in groups I, AA, and I + AA compared to the group D

The level of expression of Bax in groups I, AA and I + AA were found lower than group D. But the differences in those groups were not detected (Fig. 2a).

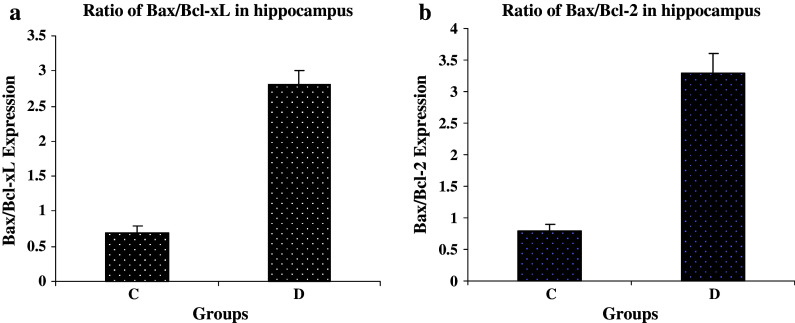

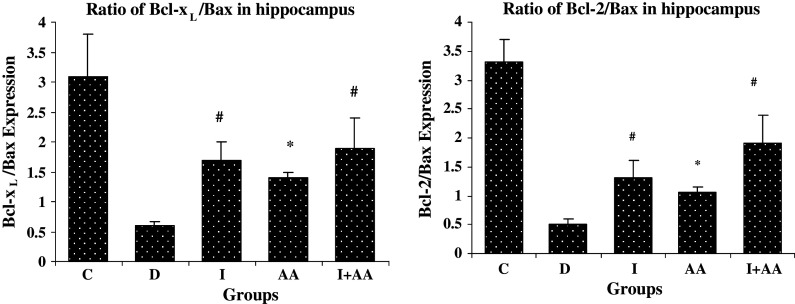

The comparison of Bax/Bcl-2 and Bax/Bcl-xL ratios between groups revealed the higher ratio in group D than group C, but the Bcl-2/Bax and Bcl-xL/Bax ratios were higher in groups I, AA and I + AA than group D (Figs. 3 and 4).

Fig. 3.

Bax/Bcl-xL and Bax/Bcl-2 expression ratios in hippocampus tissue of control (C) and STZ-induced diabetic (D) groups of rat. (a) Bar graph indicates the mean ± SEM of Bax/Bcl-xL ratio. P < 0.001, compared to the control group (n = 3 each group). (b) Bar graph indicates the mean ± SEM of Bax/Bcl-2 ratio. P < 0.01, compared to the control group (n = 3 each group)

Fig. 4.

The effects of insulin and ascorbic acid on Bcl-xL/Bax and Bcl-2/Bax expression ratios in hippocampal tissue of rats. Bar graph indicates the mean ± SEM. # P < 0.001, * P < 0.01 compared to the D group (n = 3 each group)

Analyses of Caspase 3 Activity

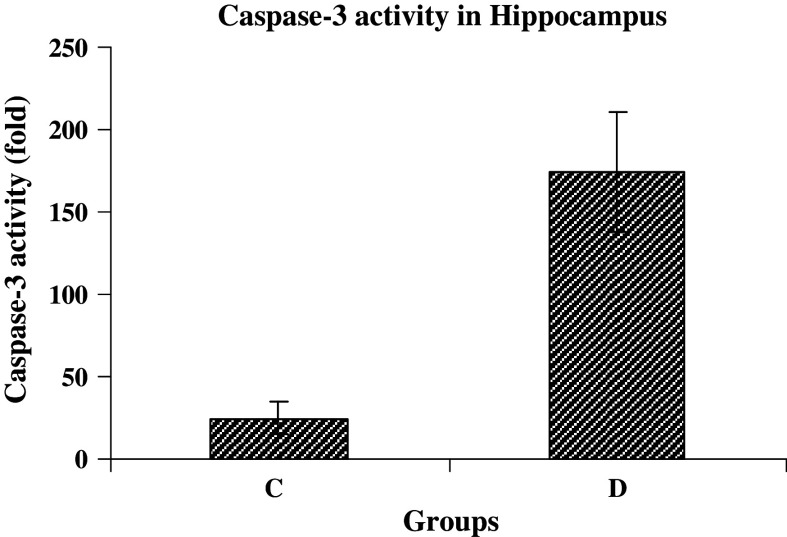

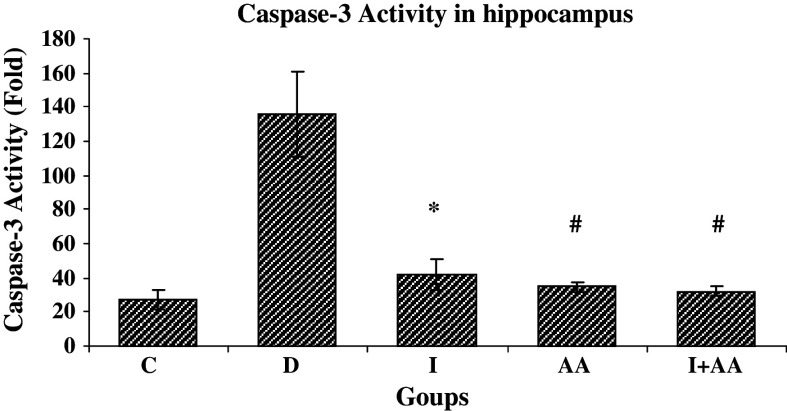

The caspase-3 activity increased nearly sevenfold higher in group D compared with group C after 8 weeks of diabetes induction (Fig. 5). But 2 weeks after treatment with insulin and ascorbic acid (groups I, AA, and I + AA), the caspase activity was decreased 3.9, 4.4, and 5.2 folds, respectively. However, no change was found in group C (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Caspase-3 activity in hippocampal tissues of control (C) and STZ-induced diabetic (D) rat groups (n = 3 each group). Bar graph indicates the mean ± SEM P < 0.001, compared to the control group)

Fig. 6.

Caspase-3 activity in hippocampal tissues rats groups C (Control), D (Diabetic), I (treated with insulin), AA (treated with ascorbic acid), and I + AA (treated with insulin + ascorbic acid) (n = 3 each group). Caspase-3 activity in groups I, AA, and I + AA showed decrease significantly compared with group D. Bar graph indicates the mean ± SEM, # P < 0.001, * P < 0.01 compared with group D

Discussion

Apoptosis is executed through a suicide program that is built into all animal cells (Podesta et al. 2000). It is proposed as a main cause of neuropathy in diabetic subjects that is related to hyperglycemia and oxidative stress. Toxicity of glucose resulted from increase of intracellular glucose oxidation process that resulted in ROS overproduction. This overproduction can lead to damage of neurons (Srinivasan et al. 1998).

It is showed that excess oxidative stress in the mitochondria leads to cellular damage. Mitochondria are the principal source of ROS in cells that are the end products of mitochondrial respiratory chain and are inhibited by intracellular antioxidants defense system, normally (Raha et al. 2000). Excess in oxidation of glucose leads to overproduction of ROS molecules like superoxides, nitric oxide, and their derivatives (Aragno et al. 2002). These can result in apoptosis that might contribute to the diabetes manifestations such as neuropathy, nephropathy, retinopathy, and vascular complications (Allen et al. 2005).

In this study, we found increase in blood glucose level is correlated with increase in Bax/Bcl-2 and Bax/Bcl-xL ratios in hippocampus tissues. Indeed, it appeared that increase in expression of proapoptotic proteins and decrease in expression of antiapoptotic proteins induce cell death in these cells.

Several experimental models support that over expression of Bax can induces apoptosis in cells both in vivo and in vitro (Li et al. 2002a, b). In addition, the apoptosis has been reported in neuroblast cell cultures treated with diabetic human sera (Srinivasan et al. 1998). Sharifi et al. showed the excess concentration of glucose resulted in increase in Bax expression protein and then induced apoptosis in PC12 cells (Sharifi et al. 2007) and decrease in Bcl-2 expression was detected in primary neurons of dorsal root ganglions (Chong et al. 2000).

Multiple lines of evidence indicate that apoptosis can be triggered by the activation of a family of cysteine proteases with specificity for aspartic acid residues, including CED-3 of C. elegans, CPP32/Yama/Apopain of humans, and DCP-1 of Drosophila. Recently, these proteins have been designated as caspases (Thornberry and Lazebnik 1998).

The most intensively studied apoptotic caspase is caspase-3, previously called CPP32/Yama/Apopain. Caspase-3 normally exists in the cytosolic fraction of cells as an inactive precursor that is activated proteolytically when cells are signaled to undergo apoptosis (Schlegel et al. 1996; Wang et al. 1996). Caspase-3 plays central roles in neuronal death during focal cerebral ischemia. Caspase-3 acts as an executioner of the neuronal apoptosis (Endresen et al. 1996; Lipton 1996).

Another step in this study was the evaluation of caspase-3 activity. It was measured using the caspase-3/CPP32 Fluorometric Assay Kit. We found 6.7-fold increase in caspase-3 activity in hippocampus of diabetic rats compared to nondiabetic rats. This finding is in concurrence with previous studies on transgenic rats and neural cells culture (Li et al. 2002a; Vincent et al. 2002).

The precise mechanism through which this occurs in hyperglycemia-induced apoptosis is not clear, but it has shown that hyperglycemia could elevate ROS in hippocampal neuronal cells resulted in elevation of intracellular calcium in neuronal cells (Rytter et al. 2005). Russell et al. (1999) showed excess mitochondrial ROS due to hyperglycemia depolarize mitochondrial membranes follows by decrease in ATP activity, increase in caspases-3 and 9 leading to caspase dependent apoptosis.

Results of this study showed that treatment with insulin can inhibit the apoptosis induced by hyperglycemia in hippocampus tissue of STZ-induced diabetic rats.

It is proposed that insulin prevents the Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL downregulation induced by hyperglycemia, release of cytochrome C and other apoptotic factors due to the relation of apoptosis threshold to ratios of antiapoptotic and proapoptotic molecules like Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Bax (Basu and Haldar 1998).

Kumar et al. in another study showed that the treatment of STZ-induced diabetic rats using insulin resulted in decrease expression of apoptotic protein, Bax, in renal tubule cells and increase expression of antiapoptotic protein, Bcl-xL (Kumar et al. 2004).

The results reported in different studies indicated antiapoptotic effects of insulin, pro-insulin, peptide C and IGF (Li et al. 2003). Raf-I dependent signaling cascade via Pi-3-Kinase pathway is activated by insulin and resulted in inhibition of apoptosis (Orike et al. 2001).

Furthermore, we found that ascorbic acid is able to inhibit apoptosis as well as insulin.

Previously the protection effect of antioxidants on neural system has been studied (Piotrowski et al. 2001). However, this is the first report of apoptotic inhibitory effect of ascorbic acid in STZ-induced apoptosis in hippocampus.

The effects of ascorbic acid on upregulation of Bcl-xL expression in colon cancer cells and downregulation of Bcl-2 expression in human endothelial cell have been confirmed (Wenzel et al. 2004).

It has been showed that ascorbic acid as an antioxidant agent has protection effects in neurological disorders like brain ischemia via inhibition of mitochondrial function in overproduction of ROS molecules (Ahn et al. 1998).

A histopathological evaluation has been demonstrated that ascorbic acid significantly attenuates apoptosis in the developing hippocampus and also simultaneous administration of ascorbic acid and lead lowered the level of Bax protein and increased Bcl-2 in pup hippocampus. Based on these studies, it seems that ascorbic acid may potentially be beneficial in treating lead-induced brain injury in the developing rat brain (Han et al. 2007).

We showed, previously that treatment with ascorbic acid and insulin, simultaneously, downregulate the expression of Bax and upregualte the expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL at mRNA level in hippocampal tissues of diabetic rats (Jafari et al. 2007).

In the present study, significant differences were not detected in single treatment with insulin or ascorbic acid and simultaneous treatment of both.

Based on the results, it is concluded that the administration of insulin and ascorbic acid has no more advantage compare with their single administration to inhibit the apoptosis.

Further and in-depth studies and clinical trials are needed to find the mechanisms of inhibitory effects of insulin and ascorbic acid on apoptosis.

Acknowledgment

Grant support was provided by Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (MUMS) (No. 85146).

References

- Ahn YH, Kim YH, Hong SH, Koh JY (1998) Depletion of intracellular zinc induces protein synthesis-dependent neuronal apoptosis in mouse cortical culture. Exp Neurol 154:47–56. doi:10.1006/exnr.1998.6931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen DA, Yaqoob MM, Harwood SM (2005) Mechanisms of high glucose-induced apoptosis and its relationship to diabetic complications. J Nutr Biochem 16:705–713. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragno M, Mastrocola R, Brignardello E, Catalano M, Robino G, Manti R, Parola M, Danni O, Boccuzzi G (2002) Dehydroepiandrosterone modulates nuclear factor-kappaB activation in hippocampus of diabetic rats. Endocrinology 143:3250–3258. doi:10.1210/en.2002-220182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi A, Dixit VM (1998) Death receptors: signaling and modulation. Science 281:1305–1308. doi:10.1126/science.281.5381.1305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Am O, Weinreb O, Amit T, Youdim MB (2005) Regulation of Bcl-2 family proteins, neurotrophic factors, and APP processing in the neurorescue activity of propargylamine. FASEB J 19:1899–1901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barres BA, Hart IK, Coles HS, Burne JF, Voyvodic JT, Richardson WD, Raff MC (1992) Cell death and control of cell survival in the oligodendrocyte lineage. Cell 70:31–46. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(92)90531-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu A, Haldar S (1998) The relationship between Bcl-2, Bax and p53: consequences for cell cycle progression and cell death. Mol Hum Reprod 4:1099–1109. doi:10.1093/molehr/4.12.1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biessels GJ, Kamal A, Urban IJ, Spruijt BM, Erkelens DW, Gispen WH (1998) Water maze learning and hippocampal synaptic plasticity in streptozotocin-diabetic rats: effects of insulin treatment. Brain Res 800:125–135. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00510-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee M, Cerami A, Vlassara H (1988) Advanced glycosylation end products in tissue and the biochemical basis of diabetic complications. N Engl J Med 318:1315–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong MJ, Murray MR, Gosink EC, Russell HR, Srinivasan A, Kapsetaki M, Korsmeyer SJ, McKinnon PJ (2000) Atm and Bax cooperate in ionizing radiation-induced apoptosis in the central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:889–894. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.2.889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desco MC, Asensi M, Marquez R, Martinez-Valls J, Vento M, Pallardo FV, Sastre J, Vina J (2002) Xanthine oxidase is involved in free radical production in type 1 diabetes: protection by allopurinol. Diabetes 51:1118–1124. doi:10.2337/diabetes.51.4.1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endresen PC, Loennechen T, Kildalsen H, Aarbakke J (1996) Apoptosis and transmethylation metabolites in HL-60 cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 278:1318–1324 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene DA, Stevens MJ, Obrosova I, Feldman EL (1999) Glucose-induced oxidative stress and programmed cell death in diabetic neuropathy. Eur J Pharmacol 375:217–223. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(99)00356-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JM, Chang BJ, Li TZ, Choe NH, Quan FS, Jang BJ, Cho IH, Hong HN, Lee JH (2007) Protective effects of ascorbic acid against lead-induced apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing rat hippocampus in vivo. Brain Res 1185:68–74. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari AI, Sankian M, Ahmadpour S, Haghir H, Bonakdaran S, Varasteh A (2007) The study of effects of insulin and ascorbic acid on Bcl-2 family expression in hippocampus of streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats. J Zanjan Univ Med Sci 60:1–16 [Google Scholar]

- Kam PC, Ferch NI (2000) Apoptosis: mechanisms and clinical implications. Anaesthesia 55:1081–1093. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2044.2000.01554.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khookhor O, Bolin Q, Oshida Y, Sato Y (2007) Effect of Mongolian plants on in vivo insulin action in diabetic rats. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 75:135–140. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2006.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G (1997) The proto-oncogene Bcl-2 and its role in regulating apoptosis. Nat Med 3:614–620. doi:10.1038/nm0697-614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D, Zimpelmann J, Robertson S, Burns KD (2004) Tubular and interstitial cell apoptosis in the streptozotocin-diabetic rat kidney. Nephron Exp Nephrol 96:e77–e88. doi:10.1159/000076749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ZG, Zhang W, Sima AA (2002a) C-peptide prevents hippocampal apoptosis in type 1 diabetes. Int J Exp Diabetes Res 3:241–245. doi:10.1080/15604280214936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ZG, Zhang W, Grunberger G, Sima AA (2002b) Hippocampal neuronal apoptosis in type 1 diabetes. Brain Res 946:221–231. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(02)02887-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ZG, Zhang W, Sima AA (2003) C-peptide enhances insulin-mediated cell growth and protection against high glucose-induced apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 19:375–385. doi:10.1002/dmrr.389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton SA (1996) Similarity of neuronal cell injury and death in AIDS dementia and focal cerebral ischemia: potential treatment with NMDA open-channel blockers and nitric oxide-related species. Brain Pathol 6:507–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orike N, Middleton G, Borthwick E, Buchman V, Cowen T, Davies AM (2001) Role of PI 3-kinase, Akt and Bcl-2-related proteins in sustaining the survival of neurotrophic factor-independent adult sympathetic neurons. J Cell Biol 154:995–1005. doi:10.1083/jcb.200101068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski P, Wierzbicka K, Smialek M (2001) Neuronal death in the rat hippocampus in experimental diabetes and cerebral ischaemia treated with antioxidants. Folia Neuropathol 39:147–154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podesta F, Romeo G, Liu WH, Krajewski S, Reed JC, Gerhardinger C, Lorenzi M (2000) Bax is increased in the retina of diabetic subjects and is associated with pericyte apoptosis in vivo and in vitro. Am J Pathol 156:1025–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raha S, McEachern GE, Myint AT, Robinson BH (2000) Superoxides from mitochondrial complex III: the role of manganese superoxide dismutase. Free Radic Biol Med 29:170–180. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00338-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reagan LP, Magarinos AM, McEwen BS (1999) Neurological changes induced by stress in streptozotocin diabetic rats. Ann N Y Acad Sci 893:126–137. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07822.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus (2003) Diabetes Care 26:S5–S20 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Russell JW, Sullivan KA, Windebank AJ, Herrmann DN, Feldman EL (1999) Neurons undergo apoptosis in animal and cell culture models of diabetes. Neurobiol Dis 6:347–363. doi:10.1006/nbdi.1999.0254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rytter A, Cardoso CM, Johansson P, Cronberg T, Hansson MJ, Mattiasson G, Elmer E, Wieloch T (2005) The temperature dependence and involvement of mitochondria permeability transition and caspase activation in damage to organotypic hippocampal slices following in vitro ischemia. J Neurochem 95:1108–1117. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03420.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraste A, Pulkki K (2000) Morphologic and biochemical hallmarks of apoptosis. Cardiovasc Res 45:528–537. doi:10.1016/S0008-6363(99)00384-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel J, Peters I, Orrenius S, Miller DK, Thornberry NA, Yamin TT, Nicholson DW (1996) CPP32/apopain is a key interleukin 1 beta converting enzyme-like protease involved in Fas-mediated apoptosis. J Biol Chem 271:1841–1844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi AM, Mousavi SH, Farhadi M, Larijani B (2007) Study of high glucose-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells: role of bax protein. J Pharmacol Sci 104:258–262. doi:10.1254/jphs.FP0070258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sima AA, Nathaniel V, Bril V, McEwen TA, Greene DA (1988) Histopathological heterogeneity of neuropathy in insulin-dependent and non-insulin-dependent diabetes, and demonstration of axo-glial dysjunction in human diabetic neuropathy. J Clin Invest 81:349–364. doi:10.1172/JCI113327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan S, Stevens MJ, Sheng H, Hall KE, Wiley JW (1998) Serum from patients with type 2 diabetes with neuropathy induces complement-independent, calcium-dependent apoptosis in cultured neuronal cells. J Clin Invest 102:1454–1462. doi:10.1172/JCI2793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry NA, Lazebnik Y (1998) Caspases: enemies within. Science 281:1312–1316. doi:10.1126/science.281.5381.1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent AM, Brownlee M, Russell JW (2002) Oxidative stress and programmed cell death in diabetic neuropathy. Ann N Y Acad Sci 959:368–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zelenski NG, Yang J, Sakai J, Brown MS, Goldstein JL (1996) Cleavage of sterol regulatory element binding proteins (SREBPs) by CPP32 during apoptosis. Embo J 15:1012–1020 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel U, Nickel A, Kuntz S, Daniel H (2004) Ascorbic acid suppresses drug-induced apoptosis in human colon cancer cells by scavenging mitochondrial superoxide anions. Carcinogenesis 25:703–712. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgh079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]