Abstract

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) represents an extremely chemoresistant tumour type. Here, authors analysed the immunophenotype of GBM tumours by flow cytometry and correlated the immunophenotypic characteristics with sensitivity to chemotherapy. The expression of selected neural and non-neural differentiation markers including A2B5, CD34, CD45, CD56, CD117, CD133, EGFR, GFAP, Her-2/neu, LIFR, nestin, NGFR, Pgp and vimentin was analysed by flow cytometry in eleven GBM (WHO gr.IV) patients. The sensitivity of tumour cells to a panel of chemotherapeutic agents was tested by the MTT assay. All tumours were positive for A2B5, CD56, nestin and vimentin. CD133, EGFR, LIFR, NGFR and Pgp were expressed only by minor tumour cell subpopulations. CD34, CD45, CD117, GFAP and Her-2/neu were constantly negative. Direct correlations were found between the immunophenotypic markers and chemosensitivity: A2B5 vs lomustine (r2 = 0.642, P = 0.033), CD56 vs cisplatin (r2 = 0.745, P = 0.013), %Pgp+ vs vincristine (r2 = 0.846, P = 0.008), and %NGFR+ vs daunorubicine (r2 = 0.672, P = 0.047) and topotecan (r2 = 0.792, P = 0.011). In contrast, inverse correlations were observed between: EGFR vs paclitaxel (r2 = −0.676, P = 0.046), CD133 vs dacarbazine (r2 = −0.636, P = 0.048) and LIFR vs daunorubicine (r2 = −0.878, P = 0.004). Finally, significant associations were also found among sensitivities to different chemotherapeutic agents and among different immunophenotypic markers. In conclusion, histopathologically identical GBM tumours displayed a marked immunophenotypic heterogeneity. The expression of A2B5, CD56, NGFR and Pgp appeared to be associated with chemoresistance whereas CD133, EGFR and LIFR expression was characteristic of chemosensitive tumours. We suggest that flow cytometric imunophenotypic analysis of GBM may predict chemoresponsiveness and help to identify patients who could potentially benefit from chemotherapy.

Keywords: Glioblastoma multiforme, Chemosensitivity, Immunophenotype, Flow cytometry

Introduction

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) represents the most malignant form of central nervous system tumours of the astrocytic origin. The average life expectancy in GBM patients is approximately 17 weeks without therapy, and 62 weeks with radiation and chemotherapy (DeAngelis 2001; Del Sole et al. 2001). Despite the very unfavourable prognosis, a small number of patients exist who display prolonged survival times. However, the genetic and phenotypic characteristics that would allow a distinction between the long-term survivors who respond to radiation and/or chemotherapy, and the rest of the GBM patients have not yet been identified.

It is well known that differences in chemosensitivity do not only exist between different histological glioma tumour types but also between histopathologically identical neoplasms. Cairncross et al. (1998) showed that anaplastic oligodendroglioma patients with certain chromosomal abnormalities (e.g. loss of heterozygosity on chromosomes 1p and 19q) exhibit longer reccurence-free survival time after chemotherapy than do individuals with other genetic changes. Recently, it has been suggested that brain tumours may arise from the so-called ‘brain tumour stem cell’ (BTSC) (Hemmati et al. 2003; Ignatova et al. 2002; Singh et al. 2003) similarly to what has been shown for leukaemia (Bonnet and Dick 1997; Lapidot et al. 1994) or breast cancer (Al-Hajj et al. 2003). These BTSCs were CD133+ (Singh et al. 2003) and the neurospheres formed expressed CD133 and nestin by immunohistochemistry (Singh et al. 2003) or CD133, musashi-1, bmi-1 and other markers by RT-PCR (Hemmati et al. 2003), the characteristics by which they closely resemble normal neural stem cells. In contrast to their normal counterparts or CD133− brain tumour cells, the BTSCs were capable of tumour initiation when transplanted into NOD–SCID mouse brains (Singh et al. 2004). These data suggest that the lineage of glioma origin may be represented by cells that typically express markers of neural and/or hematopoietic stem cells.

In addition, Dahlstrand et al. (1992) and later Almqvist et al. (2002) described increased expression of nestin in GBM than in less malignant gliomas. Furthermore, nestin and vimentin co-expression unlike expression of GFAP was shown to serve as a marker for an astrocytoma cell type with enhanced motility and invasive potential (Rutka et al. 1999). Xia et al. (2003) observed that astrocytomas expressing A2B5 displayed a higher proliferative activity and reccurence rate than their A2B5− counterparts; interestingly, A2B5+ lineage astrocytomas showed a higher frequency of p53 abnormalities. A2B5 is a marker of O-2A neural progenitor cells that give rise to oligodendrocytes and type-2 astrocytes, but is absent in type 1 astrocytes. It appears to play a role in glioma cell motility and invasion (Merzak et al. 1994) but was also associated with increased chemoresistance to carmustine (Nutt et al. 2000), one of the drugs most often used in the treatment of gliomas.

In vitro chemosensitivity assays provide a tool for the selection of a specific drug for individual patients (Yung 1989). However, each assay has pitfalls such as artificial selective pressure inherent to tissue culture sytem, heterogeneity of biopsy specimen, in vitro drifting of cultured cells from homogeneous to heteroclonal culture, possible cytotoxic effect of metabolites, not the parent compound, and finally heterogeneity in chemosensitivity and consecutive problems with the interpretation of results (Jordan et al. 1992; Kimmel et al. 1987; Yung 1989). While expression of the above-mentioned markers has been correlated with tumour malignancy, proliferative activity, invasive potential or patient prognosis, there is only a limited knowledge about such associations with respect to the sensitivity of astrocytic tumours to chemotherapy. As flow cytometry has a potential to avoid or overcome some of the issues related to in vitro chemosensitivity assays, it seemed reasonable to perform a study that would attempt to define possible relationships between the lineage of glioma tumour cells (as defined by immunophenotype) and their responsiveness to chemotherapy, an approach that has been successfully applied in hematooncology.

In this study, the expression of selected neural, as well as non-neural differentiation markers in GBM tumours was evaluated by means of multiparametric flow cytometry and the observed immunophenotype was correlated with in vitro chemosensitivity.

Methods

Patients

Eleven patients, four females and seven males with a mean age of 50 ± 8 years (range: 36–62 years) diagnosed with glioblastoma multiforme at the Department of Neurosurgery, P.J. Safarik University in Kosice, Slovakia between 2002 and 2004, were included in this study. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients before surgery. Histopathologic diagnosis and classification of GBM were established using the criteria of the WHO classification (Kleihues and Cavenee 2000). Representative samples for subsequent chemosensitivity testing and flow cytometry immunophenotypic studies were obtained from the whole tumour specimen removed at surgery.

Primary Human Glioblastoma Cell Cultures

The tumour tissue specimens were mechanically disrupted and cells were separated by density centrifugation as described previously in detail (Sarissky et al. 2005). Then, erythrocytes were lysed, isolated cells were washed twice in DMEM medium (Gibco, Life Technologies, Paisley, Scotland, UK) and resuspended in the culture medium: RPMI 1640 with GlutaMAX-I (l-alanyl-l-glutamine, 446 mg.l−1) (Gibco) supplemented with insulin (40 IU ml−1) (Actrapid® HM 100 IU/ml, Novo Nordisk, Bagsvaerd, Denmark), apo-transferrin (5 μg ml−1) (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), foetal calf serum (10%) (Gibco), penicillin (100 IU ml−1) (Gibco) and streptomycin (100 μg ml−1) (Gibco). Cells were filtered through a 40-μm cell strainer (Falcon, Becton Dickinson Biosciences—BDB, San Jose, CA, USA) to remove the cell aggregates, and the viable cells were counted in the Bürker chamber. Cell viability was estimated by trypan blue (Sigma) exclusion. After appropriate adjustment of the cell concentration, they were pipetted into standard 96-well polystyrene cell culture microplates (Sarstedt, Newton, Germany) at c = 4–8 × 104 cells per well in a total volume of 80 μl and maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2/95% air incubator (Sanyo, Japan). The excess cells were washed, resuspended in sterile PBS (pH = 7.6) with 0.5% BSA (Sigma) to achieve c = 106 cells/100 μl PBS/BSA and frozen at −20°C. These single cell suspensions were used in further immunophenotypic studies.

Chemosensitivity Testing by Using MTT Assay

The cytotoxic effects of chemotherapeutic agents including carmustin (BCNU) (BiCNU®, Bristol-Myers Squibb, USA), cisplatin (CDDP) (Platidiam 10®, Pliva-Lachema, Czech Republic), dacarbazine (DTIC) (Dacarbazin®, Pliva-Lachema, Czech Republic), daunorubicine (DAU) (Daunoblastina®, Pharmacia&Upjohn, Belgium), etoposide (VP16) (Etoposid Ebewe®, Ebewe, Austria), lomustine (CCNU) (CeeNU®, Bristol-Myers Squibb, USA), paclitaxel (TAX) (Taxol®, Bristol-Myers Squibb, USA), topotecan (TOPO) (Hycamtin®, GlaxoSmithKline, United Kingdom) and vincristine (VCR) (Vincristin Liquid-Richter®, Richter Gedeon, Hungary) were tested by using the microculture assay with the MTT end point (MTT = 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide) (Sigma). The amount of MTT reduced to formazan is proportional to the number of viable cells (Fig. 1) (Mosmann 1983). The chemotherapeutic agents were used in the following concentration ranges: 0.488–500 μg ml−1 for DTIC, 0.098–100 μg ml−1 for BCNU, CDDP and CCNU, 0.049–50 μg ml−1 for VP16, TAX, TOPO and VCR, and 0.002–2 μg ml−1 for DAU. The chemotherapeutic agents were prepared freshly from the above-mentioned pharmaceutical preparations by dilution in the RPMI culture medium in steps 1:4 and pippeted into 96-well microplates in duplicates in a total volume of 20 μl. The plates prepared in this manner were frozen at −20°C and kept for future use. The above-specified final concentrations were achieved after the addition of 80 μl of tumour cell suspensions, i.e. in the final volume of 100 μl. After 72 h of incubation, 10 μl of MTT (5 mg ml−1) was added to each well. After an additional 4 h, during which insoluble formazan was formed, 100 μl 10% SDS (Sigma) was added to each well and another 12 h were allowed for the formazan to be dissolved. The absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at 540 nm using an automated MRX microplate reader (Dynatech Laboratories, Guernsey, UK). Absorbance of the wells containing the control (untreated) cells was taken as 100% and the cell viability of the treated cells was expressed as a percentage of the control. Finally, EC50—effective concentrations required to reduce the cell viability by 50% were calculated.

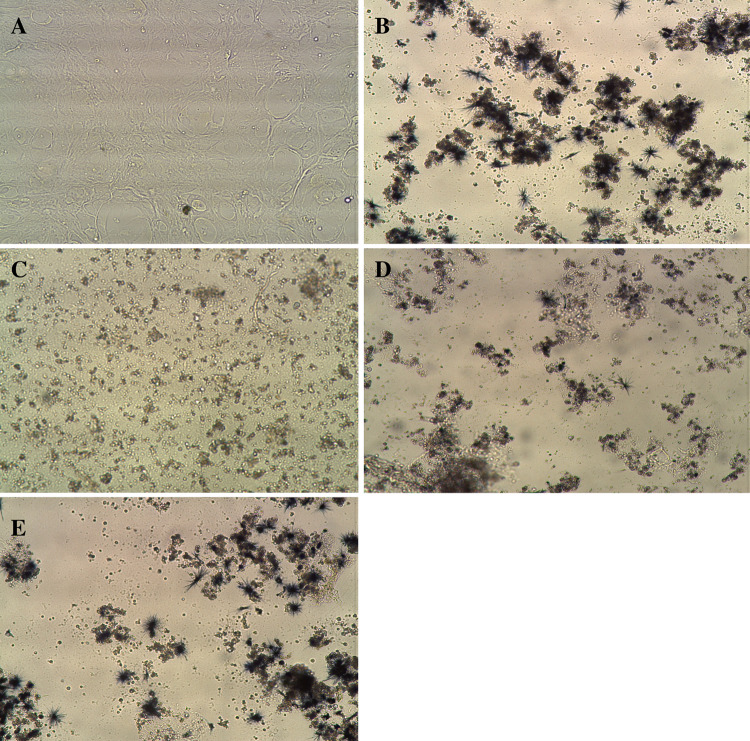

Fig. 1.

Illustrative photomicrographs showing primary culture of glioblastoma cells isolated from a GBM tumour (a) and results of the MTT assay: cells cultured in the absence of chemotherapeutic agent (b) and after 72 h cultivation with cisplatin at 100 μg ml−1 (c), 6,272 μg ml−1 (d) and 0,392 μg ml−1 (e). The amount of MTT reduced to formazan (blue crystals) is proportional to the number of viable cells (original magnification 10×, Leica DMIL inverted microscope)

Flow Cytometric Immunophenotypic Studies

Immunophenotypic analysis of tumour cells was performed using frozen glioblastoma tumour single cell suspensions after thawing at room temperature (RT). Once thawed, approx. 0.25–0.5 × 106 tumour cells in a total volume of 100 μl PBS/BSA were immediately stained for 15 min at RT with the following two-colour—fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)/phycoerythrin (PE)—combinations of monoclonal antibodies using direct immunofluorescence: 20 μl CD45 (clone HI30)/20 μl CD56 (clone NCAM16.2) (both BDB), 20 μl CD34 (clone 8G12) (BDB)/10 μl CD133/1 (clone AC133) (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), -/20 μl CD117 (clone 104D2), -/20 μl EGFR (clone EGFR.1), -/20 μl Her-2/neu (clone Neu 24.7), -/20 μl LIFR (clone 7G7), -/20 μl NGFR (clone C40-1457) (all from BDB) and -/20 μl Pgp (clone UIC2) (Immunotech, Marseille, France). Afterwards, cells were washed, resuspended in 200 μl PBS/BSA and 100 μl of a solution containing 10 μg ml−1 of Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA), and incubated for another 5 min in darkness (RT). Then, data acquisition was performed as described below.

A different staining procedure was employed for the simultaneous detection of GFAP, A2B5, vimentin and nestin neural markers. First, cells were incubated with 1 μg anti-A2B5 moAb (clone 105, pure) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) for 30 min, and subsequently with 5 μl rat anti-mouse IgG1-PE-Cy7 (clone R6-60.2) (BDB) secondary antibody for another 30 min. Then, fixation and permeabilisation of cells were performed by using Fix & Perm Cell Permeabilization Reagents (Caltag, Burlingame, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Afterwards, 20 μl anti-GFAP-PE PAb (N-18), 1 μg anti-vimentin-FITC moAb (clone V9) (both from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), and 1 μg anti-nestin moAb (clone 196098, pure) (R&D Systems) complexed with goat anti-mouse Fab-Alexa Fluor 647 conjugate (Molecular Probes) were added to cells and incubated for 30–45 min. The complex was prepared by using the Zenon™ Alexa Fluor 647® mouse IgG1 labelling kit (Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All staining steps were performed under dimmed light conditions and samples were incubated in darkness at RT. A washing step was carried out after each staining, fixation and permeabilisation step. Isotypic controls, mouse IgG1 pure, mouse IgG1-FITC, goat IgG-PE, mouse IgM pure (all from Caltag), mouse IgG1-PE (clone MOPC-21), mouse IgG2b-PE (clone 27-35) (both from BDB), and mouse IgG2a-PE (clone U7.27) (Immunotech) were used when appropriate. Subsequent to the final wash, cells were centrifuged and the cell pellet was resuspended in 200 μl PBS/BSA. Then, 100 μl of a solution containing 10 μg ml−1 of Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes) was added to each tube and the cells were incubated for another 5 min in darkness (RT). Then, data acquisition was performed in a FACS Vantage SE flow cytometer (BDB) using the CellQuest Pro software package (BDB), information being stored for 104 cells/tube. The application-specific settings were set up by means of U373 MG glioma cells (used as a positive control) stained for the above-mentioned markers. The instrument’s performance was monitored according to the European Working Group on Clinical Cell Analysis (EWGCCA) guidelines on instrument setup for immunophenotypic analysis (Kraan et al. 2003). The Paint-A-Gate Pro software package (BDB) was used for data analysis. Tumour cells were identified as those events showing strong Hoechst 33342 staining. For each antigen, the following information was reported: (1) presence or absence of an antigen, (2) intensity of expression as reflected by the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) expressed as arbitrary relative linear fluorescence channel units scaled from 0 to 104 of the stained cells after subtracting the MFI obtained for control unstained cells.

Statistical Analysis

For each variable analysed, its mean, median and range values were calculated using the SPSS Base version 13.0 software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For bivariate correlations between selected variables, the two-tailed Spearman’s correlation test was employed. Statistical significance was considered to be present once p-values were <0.05.

Results

Chemosensitivity of Glioblastomas

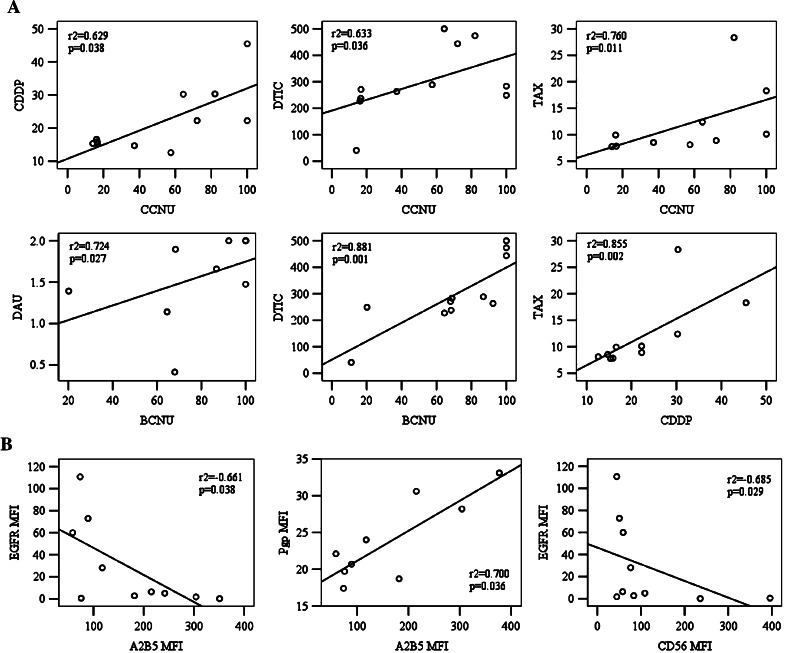

In vitro chemosensitivity testing of a histopathologically uniform group of glioblastoma tumours revealed a variable sensitivity to the panel of selected chemotherapeutic agents (Table 1). The panel included several drugs with different mechanisms of action such as alkylating, intercalating, and antimitotic agents and inhibitors of topoisomerase I and II, some of them being typically indicated for the treatment of brain tumours, while others were used only occasionally. The most frequent in vitro responses were observed for TAX followed by DTIC and TOPO. Three tumours were TAX-sensitive, six displayed partial chemosensitivity whereas only one was chemoresistant. For DAU, DTIC and TOPO we found one chemosensitive and three chemoresistant tumours, the rest being tumours of partial chemosensitivity. Approximately half of the tumours studied were found to possess high or partial chemosensitivity to CCNU or CDDP. In contrast, all but one tumour were resistant to VP16 and only two displayed sensitivity to BCNU or VCR. Interestingly, direct correlations were found between the chemosensitivity to BCNU, CCNU, CDDP, DTIC, DAU and TAX (Fig. 2a). Chemosensitivity/chemoresistance to CCNU correlated significantly with that to CDDP (r2 = 0.629, P = 0.038), DTIC (r2 = 0.633, P = 0.036) and TAX (r2 = 0.760, P = 0.011). An association was also found between resistance to CDDP and TAX (r2 = 0.855, P = 0.002). Furthermore, resistance to BCNU showed a correlation with resistance to DTIC (r2 = 0.881, P = 0.001) and DAU (r2 = 0.724, P = 0.027). Interestingly, no significant association was found between chemosensitivities to BCNU and CCNU.

Table 1.

In vitro chemosensitivity in glioblastoma tumour cells

| Case no. | CDDP | VP16 | TAX | VCR | DAU | DTIC | CCNU | BCNU | TOPO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15.331 | 40.377 | 7.768 | 50 | ND | 40.707 | 14.081 | 11.161 | ND |

| 2 | 15.226 | 50 | ND | 41.385 | 0.413 | 270.833 | 16.678 | 68.040 | 0.482 |

| 3 | 16.584 | 50 | 9.934 | 9.375 | 1.141 | 227.083 | 16.167 | 64.538 | 0.428 |

| 4 | 15.871 | 50 | 7.834 | 1.990 | 1.897 | 237.775 | 16.555 | 68.336 | 0.702 |

| 5 | 30.241 | 50 | 12.396 | 50 | 2 | 500 | 64.406 | 100 | 50 |

| 6 | 14.693 | 50 | 8.531 | 50 | 2 | 263.435 | 37.206 | 92.370 | 0.580 |

| 7 | 22.265 | 50 | 8.898 | 50 | 2 | 443.841 | 72.074 | 100 | 50 |

| 8 | 12.581 | 50 | 8.111 | 50 | 1.660 | 288.676 | 57.500 | 86.842 | 0.528 |

| 9 | 22.246 | 50 | 10.111 | ND | ND | 283.405 | 100 | 68.856 | 0.591 |

| 10 | 30.323 | 50 | 28.335 | 50 | 1.475 | 473.769 | 82.041 | 100 | 0.356 |

| 11 | 45.469 | 50 | 18.298 | 50 | 1.392 | 248.896 | 100 | 20.152 | 1.353 |

| Mean ± SD | 21.894 ± 9.937 | 49.125 ± 2.901 | 12.022 ± 6.553 | 40.275 ± 18.511 | 1.553 ± 0.528 | 298.038 ± 131.327 | 52.428 ± 33.971 | 70.936 ± 30.756 | 10.502 ± 20.819 |

Results expressed as effective concentrations EC50 in μg ml−1

ND not determined

Fig. 2.

a Chemosensitivity of glioblastoma tumours: statistically significant correlations observed between chemosensitivities to BCNU, CCNU, CDDP, DAU and DTIC. b Immunophenotype of glioblastoma tumours: statistically significant correlations observed between the expression of A2B5, CD56, EGFR and Pgp. r2, Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient

Immunophenotypic Characteristics of Glioblastomas

Variable levels of antigen expression were observed for the markers tested in the study. As shown in Table 2 and Figs. 3 and 4, expression of A2B5, vimentin, nestin, CD56, CD133, EGFR, LIFR, NGFR and Pgp was detected in glioblastoma cells while CD34, CD45, CD117 and Her-2/neu were constantly negative. Expression of GFAP was only weak or undetectable.

Table 2.

Immunophenotypic characteristics of glioblastoma tumour cells

| Case no. | GFAP | A2B5 | Vim | Nestin | CD34 | CD133 | CD56 | CD117 | EGFR | Her2 | LIFR | NGFR | Pgp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 59 | 401 | 203 | 2 | 96 | 59 | 1 | 60 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 22 |

| 2 | 33 | 182 | 1032 | 741 | 3 | 0 | 84 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 98 | 2 | 19 |

| 3 | 34 | 215 | 346 | 139 | 5 | 341 | 58 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 79 | 6 | 31 |

| 4 | 7 | 89 | 171 | 83 | 1 | 245 | 51 | 1 | 73 | 1 | 48 | 14 | 21 |

| 5 | 17 | 118 | 699 | 560 | 1 | 26 | 76 | 1 | 28 | 2 | 0 | 12 | 24 |

| 6 | 5 | 74 | 258 | 144 | 1 | 215 | 44 | 2 | 111 | 2 | 18 | 13 | 17 |

| 7 | 3 | 76 | 129 | 79 | 0 | 21 | 396 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 48 | 9 | 20 |

| 8 | 31 | 304 | 979 | 812 | 1 | 21 | 45 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 23 | 2 | 28 |

| 9 | 25 | 377 | 852 | 599 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 33 |

| 10 | 22 | 242 | 787 | 540 | 3 | 22 | 109 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 64 | 31 | ND |

| 11 | 9 | 351 | 96 | 46 | 0 | 207 | 236 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ND | 35 | ND |

| Mean ± SD | 17 ± 12 | 190 ± 117 | 523 ± 354 | 360 ± 293 | 2 ± 2 | 119 ± 122 | 116 ± 114 | 2 ± 2 | 29 ± 39 | 2 ± 2 | 42 ± 35 | 13 ± 12 | 24 ± 6 |

Results expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI, arbitrary relative linear fluorescence channel units). For positively tested markers, the MFI refers only to those cell subpopulations that displayed evident positivity for the corresponding marker. The frequency of positive cells is indicated in the text where appropriate

Vim vimentin, Her2 Her-2/neu, ND not determined

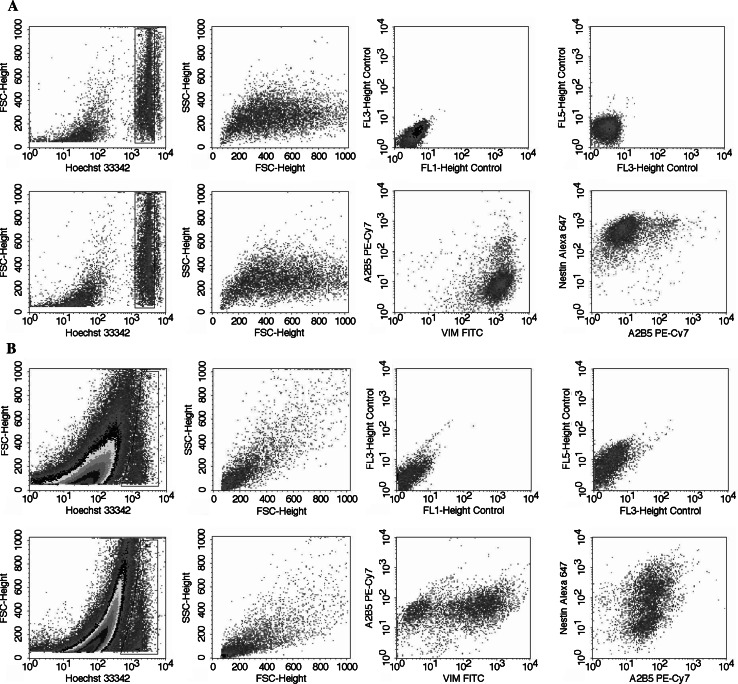

Fig. 3.

Illustrative bivariate dot plots of the multiparametric five-colour immunophenotypic analysis of a U373 MG glioma cell line (positive control) and b glioblastoma tumour cells (case 1). The upper dot plots show Hoechst 33342-stained cells used to establish the baseline autofluorescence levels of tumour cells (unstained negative control). The lower panels show glioblastoma cells stained simultaneously for Hoechst 33342 and vimentin-FITC, GFAP -PE, A2B5-PE-Cy7 and nestin-Alexa Fluor 647; the cells display bimodal vimentin and nestin staining whereas A2B5 staining is uniform

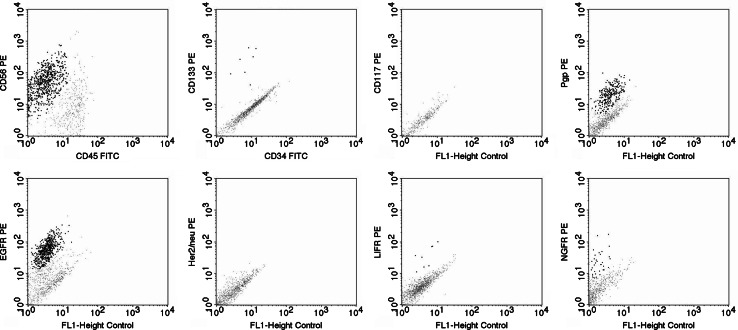

Fig. 4.

Illustrative bivariate dot plots of the immunophenotypic analysis of glioblastoma tumour cells. Examples of tumours positive for CD56 (case 5), CD133 (case 3), Pgp (case 5), EGFR (case 4), LIFR (case 4) and NGFR (case 11) are shown (positive cells are visualised as highlighted black dots). However, all tumours were negative for CD45, CD34 (case 3), Her-2/neu (case 1) and CD117 (case 1). CD45 was only expressed on infiltrating leukocytes

From the positive antigens, low to intermediate levels of CD133, EGFR, LIFR, NGFR and Pgp were detected in nine out of ten, four out of ten, seven out of nine, six out of ten and nine out of nine cases studied, respectively. However, the positively tested samples contained variable proportions of positive cells: CD133 was positive in 0.6–2.6% of cells, EGFR in 1.6–43.0%, LIFR in 0.3–2.7%, NGFR in 1.6–73.0% and Pgp in 9.7–27.7% of cells. In contrast, A2B5, vimentin, nestin and CD56 were constantly positive, i.e. were detected in all samples tested. CD45+ cells were also present in all tumours with a frequency ranging from 14% to 39%. These cells were identified as infiltrating leukocytes. The strongest reactivity among positive cells was found for vimentin and nestin (mean MFI of 523 ± 354 and 360 ± 293, respectively); A2B5+ CD133+ and CD56+ cases showed intermediate intensities (mean MFI of 190 ± 117, 119 ± 122 and 116 ± 114, respectively) while expression of GFAP, EGFR, LIFR, NGFR and Pgp was the lowest in terms of MFI/cell (17 ± 12, 29 ± 39, 42 ± 35, 13 ± 12 and 24 ± 6, respectively).

Interestingly, both direct and inverse correlations were observed among the expressions of A2B5, CD56, EGFR and Pgp: A2B5 vs EGFR (r2 = −0.661, P = 0.038), A2B5 vs Pgp (r2 = 0.700, P = 0.036) and CD56 vs EGFR (r2 = −0.685, P = 0.029) (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, A2B5 expression was higher in tumours with a lower percentage of EGFR+ cells (r2 = −0.751, P = 0.012) whereas LIFR expression was higher in tumours that contained less Pgp+ cells (r2 = −0.922, P = 0.001).

Upon staining glioblastoma tumour cells simultaneously for GFAP, A2B5, vimentin, nestin and DNA (Fig. 3), we observed a marked variability in their expression in individual glioblastoma cases (Table 2). Moreover, nine of 11 tumours were found to contain two cell subpopulations distinguishable by different vimentin and/or nestin staining intensities (Fig. 3). Generally, one of the subpopulations was negative, whereas the other was positive. The proportion of the positive population ranged from 26.8% to 73.0%. In contrast, the expression of A2B5 was relatively uniform. Thus, we observed not only intertumoural, but also intratumoural heterogeneity of vimentin and nestin expression. For A2B5, however, only intertumoural not intratumoural heterogeneity was detected.

Relationship Between Immunophenotype and Chemosensitivity

As summarised in Table 3, significant relationships were found between the immunophenotype of individual glioblastoma tumours and their chemosensitivity/chemoresistance to selected chemotherapeutic agents. First, expression of A2B5 showed a significant association with chemoresistance to CCNU, strongly positive tumours being more resistant (r2 = 0.642, P = 0.033). However, for GFAP, vimentin and nestin, no significant correlations were observed. In contrast, high CD56 expression correlated significantly with chemoresistance to CDDP (r2 = 0.745, P = 0.013) and non-significantly to CCNU (r2 = 0.588, P = 0.074). Furthermore, NGFR expression was increased in tumours that were resistant to CDDP (r2 = 0.636, P = 0.048) and CCNU (r2 = 0.661, P = 0.038). Moreover, tumours showing a higher percentage of NGFR+ cells displayed significantly greater chemoresistance to DAU (r2 = 0.672, P = 0.047) and TOPO (r2 = 0.792, P = 0.011), and non-significantly to CDDP (r2 = 0.607, P = 0.063), CCNU (r2 = 0.575, P = 0.082) and BCNU (r2 = 0.589, P = 0.073). Similarly, tumours with a higher proportion of Pgp+ cells were chemoresistant to VCR (r2 = 0.846, P = 0.008). In contrast, an inverse association was observed between the expression of EGFR and chemoresistance to TAX, EGFR+ tumours being chemosensitive while EGFR− tumours were chemoresistant. The TAX-resistant tumours also displayed non-significant increases in the expression of A2B5 (r2 = 0.612, P = 0.060) and NGFR (r2 = 0.617, P = 0.077). Inverse associations were also found between the expression of CD133 and chemoresistance to DTIC (r2 = −0.636, P = 0.048) and expression of LIFR and chemoresistance to DAU (r2 = −0.878, P = 0.004). Furthermore, LIFR+ tumours displayed a tendency towards being more VCR- and TOPO-sensitive (r2 = −0.656, P = 0.055 and r2 = −0.683, P = 0.062) than their LIFR− counterparts. Finally, no significant relationships were observed between any of the markers analysed and the chemosensitivity/chemoresistance to VP16 and BCNU. Overall, an increased expression of A2B5, CD56 and NGFR as well as a higher percentage of NGFR+ and Pgp+ cells were associated with chemoresistance, whereas CD133-, EGFR- and LIFR-positivity was typical of chemosensitive glioblastoma tumours.

Table 3.

Glioblastoma tumours: correlations observed between the expression/frequency of expression of the positively tested markers and the chemosensitivities to a panel of antineoplastic agents

| CDDP | VP16 | TAX | VCR | DAU | DTIC | CCNU | BCNU | TOPO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2B5 | – | – | r2 = 0.612 | – | r2 = −0.661 | – | r2 = 0.642 | – | – |

| P = 0.060 | P = 0.053 | P = 0.033 | |||||||

| Vim | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | r2 = −0.565 |

| P = 0.089 | |||||||||

| Nestin | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| CD56 | r2 = 0.745 | – | – | – | – | – | r2 = 0.588 | – | – |

| P = 0.013 | P = 0.074 | ||||||||

| CD133 | – | – | – | – | – | r2 = −0.636 | – | – | – |

| P = 0.048 | |||||||||

| %CD133+ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| EGFR | – | – | – | – | – | – | r2 = −0.624 | – | – |

| P = 0.054 | |||||||||

| %EGFR+ | – | r2 = −0.588 | r2 = −0.676 | – | r2 = 0.594 | – | – | – | – |

| P = 0.074 | P = 0.046 | P = 0.092 | |||||||

| LIFR | – | – | – | r2 = −0.656 | r2 = −0.878 | – | – | – | r2 = −0.683 |

| P = 0.055 | P = 0.004 | P = 0.062 | |||||||

| %LIFR+ | r2 = −0.650 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| P = 0.058 | |||||||||

| NGFR | r2 = 0.636 | – | r2 = 0.617 | – | – | – | r2 = 0.661 | – | – |

| P = 0.048 | P = 0.077 | P = 0.038 | |||||||

| %NGFR+ | r2 = 0.607 | – | – | – | r2 = 0.672 | – | r2 = 0.575 | r2 = 0.589 | r2 = 0.792 |

| P = 0.063 | P = 0.047 | P = 0.082 | P = 0.073 | P = 0.011 | |||||

| Pgp | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| %Pgp+ | – | – | – | r2 = 0.846 | r2 = 0.667 | – | – | – | – |

| P = 0.008 | P = 0.102 |

r2, Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient

Discussion

For a number of different neural markers, associations have been demonstrated between their expressions in human gliomas and histopathologic grading of the tumours, their proliferative activity and invasive potential as well as patient prognosis. However, no analogous relationships have been revealed between those markers and the response of gliomas to chemotherapy, with the exception of proteins involved in multidrug resistance. In spite of an extremely unfavourable prognosis for a vast majority of GBM patients, a small percentage of them still do respond to therapy (therapeutical modalities include surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy) and enjoy long-term survival. In this study, we have attempted to identify possible relationships between the expression of selected neural differentiation markers in GBMs as detected by flow cytometry and in vitro chemosensitivity of the tumours. In a set of eleven human glioblastomas, we observed heterogeneous patterns of chemosensitivity and neural differentiation marker expression as well as several potentially important correlations between these two parameters. This could be especially interesting in families with two or more members affected by brain tumours (Sulla et al. 1987).

The strongest reactivity was found for nestin and vimentin. These markers were detected in all tumours although with a high variability in staining intensity. A number of authors found an increased expression of nestin in glioblastomas as compared to gliomas of lower malignancy or normal brain tissue (Almqvist et al. 2002; Ma et al. 2008) and demonstrated correlation between amounts of nestin positive cells and the malignant behaviour of tumours (Strojnik et al. 2007; Ma et al. 2008). Rutka et al. (1999) reported an increased motility and invasiveness in astrocytoma cells co-expressing nestin and vimentin. However, an inverse relationship was found between the expression of nestin and GFAP. GFAP is very often lost completely in the most malignant gliomas (i.e. glioblastomas) which tend to lack the markers of mature astrocytes probably due to their undifferentiated nature. In addition, nestin positivity was also demonstrated in the tumour neovasculature and immature endothelial cells as contrasted with differentiated endothelial cells of normal blood vessels thus supporting the hypothesis that an increase in blood supply is critical to GBM progression (Mokry et al. 2004; Mangiola et al. 2007). In our study, an abundant expression of nestin and vimentin as opposed to GFAP was found. However, no significant associations between the expression of these markers and chemosensitivity to any of the chemotherapeutic agents tested in our study was found.

A hypothesis has been recently introduced that glioma as well as other brain tumours (e.g. medulloblastomas) may arise from nestin- and/or CD133+ neural stem-like cells named ‘brain tumour stem cells’. Basically, this means that only a small subset of tumour cells (resembling neural stem or progenitor cells) has clonogenic capacity, and these cells alone are capable of further propagation (Singh et al. 2004). These brain tumour stem cells may be characterised phenotypically (similarly to leukaemias) and their phenotype may be reflected in typical patterns of sensitivity to different chemotherapeutic agents (again similarly to leukaemias). However, the existence of different subtypes of primary GBMs has been supposed upon the CD133 expression. CD133 negative primary GBMs were characterized by a lower proliferation index (Ki-67) and by different gene expression than CD133+ primary GBMs, whereas GFAP staining was similar (Beier et al. 2007). Indeed, we found CD133+ cells in 90% of the tumours studied. The frequency of positive cells was approx. 1–3% of the total tumour cell population. The statistical analysis revealed that tumours containing CD133+ cells with higher staining intensities displayed increased chemosensitivity to DTIC. This might be explained by a reported increased proliferative activity of CD133+cells. Such fast proliferating tumours might initially display better responses to chemotherapeutics; however, they perhaps recover more quickly from the chemotherapy-induced damage which is consequently reflected in a rapid tumour reccurence and reduced patient survival times. Liu et al. (2006) have indicated that CD133+ glioma stem cells display strong capability of resistance to chemotherapy probably due to their higher expression of BCRP1 (ATP-binding cassette transporter protein) and MGMT (O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase), as well as the anti-apoptosis protein and inhibitors of apoptosis protein families. Concerning radioresistance, glioma stem cells expressing CD133 (Bao et al. 2006) or cells expressing aldehyde dehydrogenase (Bar et al. 2007), which has been shown to mark both haematopoietic and neural stem cells (Armstrong et al. 2004; Corti et al. 2006) survive radiation in increased proportions in comparison to most CD133− tumour cells (Bao et al. 2006; Bar et al. 2007) and preferentially activated the DNA damage checkpoint in response to radiation as well as repaired radiation-induced DNA damage more effectively than CD133− tumour cells (Bao et al. 2006).

Furthermore, we also observed a marked expression of A2B5, a lipopolysacharide found on cell membranes of immature neural cells. The expression of A2B5 was increased in tumours resistant to CCNU and TAX. The observation of high levels of A2B5 on glioblastoma cells is consistent with other authors’ findings that increased A2B5 expression correlates well with tumour proliferative activity, recurrence rate (Xia et al. 2003) and with tumour grade (Ogden et al. 2008). Moreover, it has been demonstrated that A2B5 might be involved in tumour motility and invasion (Merzak et al. 1994). More recently it has been shown that GBMs contain neoplastic glial restricted precursor cells (GRP), which are migrating, dividing, express A2B5 or GFAP and can generate oligodendrocytes or type-1 and type-2 astrocytes in appropriate culture medium (Colin et al. 2006). On the other hand (in contrast with oligodendrogliomas and low-grade astrocytomas), minority of GBMs express markers such as NG2 and PDGFR-α distinctive for oligodendrocyte type-2 astrocyte (O2-A) precursors (Shoshan et al. 1999). If these observations mean that GBMs may develop from different types of progenitors, such as NSCs, GRP or even O2-A progenitor or appearance of these precursors may predict favourable prognosis is still a matter of debate. Ogden et al. (2008) demonstrated that A2B5 reactivity identifies human glioma cells with increased tumorigenicity compared with cells without A2B5 reactivity. In a study comparing chemosensitivity of rat astrocytes (GFAP+A2B5-GalC-), O-2A progenitors (GFAP-A2B5+GalC-) and oligodendrocytes (GFAP-A2B5-GalC) to BCNU, Nutt et al. (2000) demonstrated that A2B5+ progenitors displayed the greatest chemoresistance amongst all cell types examined. The resistance could probably be accounted for by high levels of MGMT expression in A2B5+ progenitors since its inhibition by O6-benzylguanin completely restored the sensitivity to BCNU. In our study, similarly, an increased chemoresistance to BCNU was found in the group of tumours with higher rather than lower levels of A2B5 expression but the difference was not significant. Furthermore, we found a significant association between the expression of A2B5 and chemoresistance to CCNU. Both agents, BCNU and CCNU, belong to the same group of alkylating agents, namely the nitrosourea derivatives.

Similar to other authors, we observed an abundant expression of CD56, a neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM), in glioblastoma tumour cells. A downregulation of NCAM with an increasing grade of malignancy was shown in a set of 52 astrocytic tumours (Sasaki et al. 1998). Furthermore, an increased expression of CD56 was associated with diminished motility of tumour cells and hence compromised capacity to infiltrate normal brain parenchyma (Prag et al. 2002). However, Owens et al. (1998) found that NCAM-overexpressing rat CNS-1 glioma cells exhibited a less cohesive pattern of growth near the site of tumour instillation and more individual cell infiltration of the brain parenchyma after implantation into a rat frontal cortex. In our study, we observed that tumours expressing higher levels of CD56 showed increased chemoresistance to CDDP and CCNU. This observation might be explained by a hypothesis that less motile tumour cells might form larger and/or more dense tumours which could be less permeable to chemotherapeutic agents thus decreasing their anti-tumour effects. Contrary to our findings, Hikawa et al. (2000) reported a reduced expression of NCAM in doxorubicine-, etoposide- and vincristine-selected drug-resistant IN157 human glioma cells.

Of growth factors receptors that play a role in proliferation and differentiation of neural stem and precursor cells, we selected EGFR, Her-2/neu, LIFR and NGFR to be analysed in this study. In GBM, EGFR abnormalities are found in around 40% of the cases (Hamel and Westphal 2000; Ohgaki et al. 2004; Waha et al. 1996). This is consistent with our findings when EGFR-positivity was observed in four of ten glioblastoma cases studied. We found an increased chemosensitivity to CCNU and TAX in EGFR+ tumours in comparison with their EGFR− counterparts. A possible explanation might lie in the assumption that faster growing EGFR+ tumours initially respond well to chemotherapy but the recurrence can occur earlier. Interestingly, Chakravarti et al. (2002) demonstrated an actual antagonistic effect between sequential aministration of radiation and BCNU chemotherapy in primary human GBM cell lines, which also happen to demonstrate strong expression of the EGFR. Upon inhibition of EGFR with the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, this crossresistance between sequential administration of radiation and BCNU was abrogated and actually results in a greater enhancement of apoptosis in the setting of combined modality therapy.

An overexpression of Her-2/neu was documented by the immunohistochemistry studies on 347 cases of primary malignant brain tumours (Potti et al. 2004) and 149 cases of glioblastomas (Koka et al. 2003) in 10.4 and 15.4% of patients, respectively. Her-2/neu overexpression was associated with a significant increase in mortality in this patient subgroup and correlated to a higher degree of glioma cells anaplasia (Kristt and Yarden 1996). Application of anti-HER2/neu antibodies induces apoptosis and cellular-dependent cytotoxicity of HER2/neu-expressing GBM cell lines (Mineo et al. 2004). Contrary to these reports, we did not detect any Her-2/neu expression in our set of glioblastoma tumours. This might be due to a low number of patients in our study. Nevertheless, the role of Her-2/neu in glioblastoma remains unclear.

Regarding the expression of LIFR (leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor), we found a small percentage (up to 3%) of LIFR+ cells in seven out of nine tumours tested and LIFR expression was associated with chemosensitivity of tumour cells to CDDP, DAU, TOPO and VCR. Carpenter et al. (1999) showed that LIF promotes the proliferation of neural stem cells and their long-term maintenance in an undifferentiated state. However, its role in glioma pathogenesis and response to therapy remains to be elucidated.

As for NGFR (nerve growth factor receptor), we observed its expression in six out of ten tumours tested with a high variability in the proportion of positive cells ranging from 1.6% to 73%. Tumours showing a higher percentage of NGFR+ cells displayed significantly greater chemoresistance to DAU and TOPO, and non-significantly, to CDDP, CCNU and BCNU. Except demonstration of expression of the receptor in some glioma cell lines (Amano et al. 1992; Bilzer et al. 1991), no correlations with tumour grading, patient prognosis or therapeutical outcome have been reported yet.

Finally, we found consistent expression of Pgp (P-glycoprotein) in 9.7–27.7% of cells in all samples analysed. An increased proportion of Pgp+ cells correlated well with chemoresistance to VCR. However, it is unclear if the detected Pgp+ cells were tumoural or endothelial cells. The expression of Pgp were significantly associated with CD133 expression in majority of the GBM suggesting a greater number of stem cells and higher multidrug resistance gene profiles in glioma compared with normal brain tissues (Shervington and Lu 2008). Several studies have demonstrated Pgp expression in human gliomas prevailing in endothelial rather than tumour cells (Andersson et al. 2004; Rieger et al. 2000). Increased expression of Pgp by tumour neovasculature endothelium was associated with higher degree of malignancy (von Bossanyi et al. 1997) and worse prognosis of glioma patients (Andersson et al. 2004; von Bossanyi et al. 1997;). An in vitro study on glioma cell lines demonstrated an increased chemosensitivity of cells to VCR when they were coexposed to verapamil, a Pgp inhibitor (Rieger et al. 2000). The above findings are in congruence with our observation of the increased resistance to VCR in tumours with a higher frequency of Pgp+ cells.

Several in vitro chemosensitivity assays have been developed for predicting the clinical response of malignant gliomas to chemotherapy. By using colony-forming assay Rosenblum and Gerosa (1984) reported that only five of the 11 patients with GBM with in vitro sensitivity to BCNU had an in vivo response to BCNU while 11 of the 13 patients with GBM with in vitro resistance were resistant to BCNU in vivo. Yung (1989) studied 12 patients with malignant gliomas and demonstrated that two of the three patients with in vitro sensitivity to CDDP or BCNU showed in vivo response to intraearotid infusion of BCNU and CDDP, while one of the three patients with in vitro resistance to BCNU and CDDP also showed clinical response to BCNU and CDDP. Kornblith et al. (1981) studied clinical correlation with cytotoxicity assay against BCNU for 14 patients with brain tumours. Nine patients had in vitro sensitivity to BCNU, but only five responded clinically to BCNU, while the other five patients with in vitro resistance to BCNU did not respond to BCNU. Darling and Thomas (1983) utilized an amino-acid precursor uptake assay for an in vitro–in vivo comparison and found out that patients whose tumour cells responded to CCNU in vitro had a longer survival time after treatment with PCV than other patients. in vitro sensitivity to procarbazine or vincistine had no correlation with survival time. Bogdahn (1983) reported that seven patients with gliomas showing in vitro sensitivity to BCNU studied with a thymidine uptake assay lived longer than the ten patients who did not. The study was in contrast to the results reported by Nikkhah et al. (1992) that BCNU sensitivity increased with increasing grades of malignancy. In vitro chemosensitivity assay should provide a tool for selection of a specific drug for the individual patient. However, this goal seems to be still illusive until pitfalls in the assays mentioned above will be overcome.Clinical chemoresistance seems to be correctly predicted in nearly 100% of the patients whereas chemosensitivity in only 50–70% (Kimmel et al. 1987; Kornblith et al. 1981; Rosenblum and Gerosa 1984; Yung 1989). The MTT assay, however, shows a tendency to underestimation rather than overestimation of chemosensitivity (Kimmel et al. 1987). Based on this, we might assume that the MTT assay employed in this study should yield consistent and reliable estimates of at least chemoresistance. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that the associations between some of the immunophenotypic characteristics and chemoresistance observed in our study could indeed reflect clinical reality and could be later confirmed in further studies correlating the phenotype with clinical response to chemotherapy.

Interestingly, we also found inverse relationships between some of the markers typical for chemosensitive tumours and some of the markers characteristic for their chemoresistant counterparts. For example, EGFR was inversely correlated with A2B5, CD56 and NGFR. However, there were direct associations amongst A2B5, CD56 and Pgp. Similarly, LIFR expression was reduced in tumours containing higher percentages of Pgp+ cells. These associations provide further support for our observation of relationships that were hypothesised to be existent between immunophenotypic characteristics of glioblastomas and their response to chemotherapy.

To conclude, in this study, we have found a marked heterogeneity in the immunophenotypic characteristics and chemosensitivity patterns within a group of histopathologically identical glioblastoma multiforme tumours. Flow cytometric analysis seems to have proven to be a suitable method for the study of the glioma tumour immunophenotype as it enables detection of multiple phenotypic markers simultaneously on a single cell. This facilitates a much more complex analysis than the traditional methods such as immunohistochemistry permit. We suggest that A2B5, CD56, NGFR and Pgp expression appear to be associated with chemoresistance whereas CD133, EGFR and LIFR expression are characteristic of chemosensitive tumours. However, one should be aware that our conclusions are limited by a low number of patients included in this study and therefore should be validated by further independent investigations. It also remains to be clarified if the above findings are applicable under in vivo conditions as well and whether they indeed reflect clinical reality. Therefore, further studies should be performed that would correlate immunophenotype of tumour cells not only with in vitro but also more importantly with in vivo (clinical) response to chemotherapy. Nonetheless, based on our results, such an approach appears to be feasible. In conclusion, we suggest that multiparametric flow cytometric imunophenotypic analysis of glioblastoma multiforme tumours may predict chemoresponsiveness and help to identify patients who could potentially benefit from chemotherapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Slovak Research and Development Agency under contracts No. APVT-20-014002, APVT-20-032504 and APVV-20-052005. The work was further supported by 23/2002/IG4 and 16/2002/IGM1 intramural grants of the Faculty of Medicine, P.J. Safarik University as well as by the League Against Cancer, Slovakia (Liga proti rakovine SR). The authors also wish to thank Mr. Chris Herbert of the British Council, Kosice, Slovakia for checking and correcting the manuscript.

Footnotes

Vladimir Balik and Marek Sarissky contributed equally to this work and are considered joint first authors.

References

- Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF (2003) Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:3983–3988. doi:10.1073/pnas.0530291100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almqvist PM, Mah R, Lendahl U, Jacobsson B, Hendson G (2002) Immunohistochemical detection of nestin in pediatric brain tumors. J Histochem Cytochem 50:147–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano T, Yamakuni T, Okabe N, Kuwahara R, Ozawa F, Hishinuma F (1992) Regulation of nerve growth factor and nerve growth factor receptor production by NMDA in C6 glioma cells. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 14:35–42. doi:10.1016/0169-328X(92)90007-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson U, Malmer B, Bergenheim AT, Brannstrom T, Henriksson R (2004) Heterogeneity in the expression of markers for drug resistance in brain tumors. Clin Neuropathol 23:21–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong L, Stojkovic M, Dimmick I, Ahmad S, Stojkovic P, Hole N, Lako M (2004) Phenotypic characterization of murine primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells isolated on basis of aldehyde dehydrogenase activity. Stem Cells 22:1142–1151. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2004-0170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, Hao Y, Shi Q, Hjelmeland AB, Dewhirst MW, Vagner DD, Rich JN (2006) Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature 444:756–760. doi:10.1038/nature05236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar EE, Chaudhry A, Lin A, Fan X, Schreck K, Matsui W, Piccirillo S, Vescovi AL, DiMeco F, Olivi A, Eberhart CG (2007) Cyclopamine-mediated hedgehog pathway inhibition depletes stem-like cancer cells in glioblastoma. Stem Cells 25:2524–2533. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2007-0166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier D, Hau P, Proescholdt M, Lohmeier A, Wischhusen J, Ordner PJ, Signet L, Brawanski A, Bogdahn U, Beier CP (2007) CD133+ and CD133- glioblastoma-derived cancer stem cells show differential growth characteristics and molecular profiles. Cancer Res 67:4010–4015. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilzer T, Stavrou D, Dahme E, Keiditsch E, Burrig KF, Anzil AP, Wechsler W (1991) Morphological, immunohistochemical and growth characteristics of three human glioblastomas established in vitro. Wirchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 418:281–293. doi:10.1007/BF01600156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdahn V (1983) Chemosensitivity of malignant human brain tumors. Preliminary results. J Neurooncol 1:149–166. doi:10.1007/BF00182961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet D, Dick JE (1997) Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med 3:730–737. doi:10.1038/nm0797-730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairncross JG, Ueki K, Zlatescu MC, Lisle DK, Finkelstein DM, Hammond RR, Silver JS, Stark PC, Macdonald DR, Ino Y, Ramsay DA, Louis DN (1998) Specific genetic predictors of chemotherapeutic response and survival in patients with anaplastic oligodendrogliomas. J Natl Cancer Inst 90:1473–1479. doi:10.1093/jnci/90.19.1473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter MK, Cui X, Hu ZY, Jackson J, Sherman S, Seiger A, Wahlberg LU (1999) In vitro expansion of a multipotent population of human neural progenitor cells. Exp Neurol 158:265–278. doi:10.1006/exnr.1999.7098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarti A, Chakladar A, Delaney MA, Latham DE, Loeffler JS (2002) The epidermal growth factor receptor pathway mediates resistance to sequential administration of radiation and chemotherapy in primary human glioblastoma cells in a RAS-dependent manner. Cancer Res 62:4307–4315 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colin C, Baeza N, Tong S, Bouvier C, Quilichini B, Durbec P, Figarella-Branger D (2006) In vitro identification and functional characterization of glial precursor cells in human gliomas. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 32:189–202. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2990.2006.00740.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corti S, Locatelli F, Papadimitriou D, Donadoni C, Salani S, Del Bo R, Strazzer S, Bresolin N, Comi GP (2006) Identification of a primitive brain-derived neural stem cell population based on aldehyde dehydrogenase activity. Stem Cells 24:975–985. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2005-0217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlstrand J, Collins VP, Lendahl U (1992) Expression of the class VI intermediate filament nestin in human central nervous system tumors. Cancer Res 52:5334–5341 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling BL, Thomas DGT (1983) Results obtained using assay of intermediate duration and clinical correlations. In: Dendy PP, Hill BT (eds) Human Tumor Drug Sensitivity Testing in Vitro. Techniques and clinical applications. Academic Press, London, pp 269–280 [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelis LM (2001) Brain tumors. N Engl J Med 344:114–123. doi:10.1056/NEJM200101113440207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Sole A, Falini A, Ravasi L, Ottobrini L, De Marchis D, Bombardieri E, Lucignani G (2001) Anatomical and biochemical investigation of primary brain tumours. Eur J Nucl Med 28:1851–1872. doi:10.1007/s002590100604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel W, Westphal M (2000) Growth factors in gliomas revisited. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 142:113–138. doi:10.1007/s007010050015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmati HD, Nakano I, Lazareff JA, Masterman-Smith M, Geschwind DH, Bronner-Fraser M, Kornblum HI (2003) Cancerous stem cells can arise from pediatric brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:15178–15183. doi:10.1073/pnas.2036535100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikawa T, Mori T, Abe T, Hori S (2000) The ability in adhesion and invasion of drug-resistant human glioma cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 19:357–362 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignatova T, Kukekov VG, Laywell ED, Suslov ON, Vrionis FD, Steindler DA (2002) Human cortical glial tumors contain neural stem-like cells expressing astroglial and neuronal markers in vitro. Glia 39:193–206. doi:10.1002/glia.10094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan JP, Hand CM, Markowitz RS, Black P (1992) Test for chemotherapy sensitivity of cerebral gliomas: use of colorimetric MTT assay. J Neurooncol 14:19–35. doi:10.1007/BF00170942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel DW, Shapiro JR, Shapiro WR (1987) In vitro drug sensitivity testing in human gliomas. J Neurosurg 66:161–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleihues P, Cavenee WK (2000) Pathology and genetics of tumours of the nervous system. IARC Press, Lyon [Google Scholar]

- Koka V, Potti A, Forseen SE, Pervez H, Fraiman GN, Koch M, Levitt R (2003) Role of Her-2/neu overexpression and clinical determinants of early mortality in glioblastoma multiforme. Am J Clin Pathol 26:332–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornblith PL, Smith BH, Leonard LA (1981) Response of cultured human brain tumors to nitrosoureas: correlations with clinical data. Cancer 47:255–265. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19810115)47:2%3c255::AID-CNCR2820470209%3e3.0.CO;2-J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraan J, Gratama JW, Keeney M, D’Hautcourt JL (2003) Setting up and calibration of a flow cytometer for multicolor immunophenotyping. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 17:223–233 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristt DA, Yarden Y (1996) Differences between phosphotyrosine accumulation and neu/erbB-2 receptor expression in astrocytic proliferative processes: implication for glial oncogenesis. Cancer 78:1272–1283. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960915)78:6%3c1272::AID-CNCR16%3e3.0.CO;2-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, Murdoch B, Hoang T, Caceres-Cortes J, Minden M, Paterson B, Callgiuri MA, Dick JE (1994) A cell initiating human acute leukemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature 367:645–648. doi:10.1038/367645a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Juan X, Zeng Z, Tunici P, Ng H, Abdulkadir IR, Lu L, Irvin D, Black KL, Yu JS (2006) Analysis of gene expression and chemoresistance of CD133+ cancer stem cells in glioblastomas. Mol Cancer 5:67–68. doi:10.1186/1476-4598-5-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma YH, Mentlein R, Knerlich F, Kruse ML, Mehdorn HM, Held-Feindt J (2008) Expression of stem cell markers in human astrocytomas of different WHO grades. J Neurooncol 86:31–45. doi:10.1007/s11060-007-9439-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangiola A, Lama G, Giannitelli C, De Bonis P, Anile C, Lauriola L, La Torre G, Sabatino G, Maira G, Jhanwar-Uniyal M, Sica G (2007) Stem cell marker nestin and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases in tumor and peritumor areas of glioblastomas multiforme: possible prognostic implications. Clin Cancer Res 13:6970–6977. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merzak A, Koochekpour S, Pilkington GJ (1994) Cell surface gangliosides are involved in the control of human glioma cell invasion in vitro. Neurosci Lett 177:44–46. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(94)90040-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineo J-F, Bordron A, Quintin-Roue I, Loisel S, Ster KL, Buhe V, Lagarde N, Berthou C (2004) Recombinant humanised anti-HER2/neu antibody (Herceptins®) induces cellular death of glioblastomas. Br J Cancer 91:1195–1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokry J, Cizkova D, Filip S, Ehrmann J, Osterreicher J, Kolar Z, English D (2004) Nestin expression by newly formed human blood vessels. Stem Cells Dev 13:658–664. doi:10.1089/scd.2004.13.658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T (1983) Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods 65:55–63. doi:10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikkhah G, Tonn JC, Hoffmann O, Kraemer H-P, Darling JL, Schachenmayr W, Schönmayr R (1992) The MTT assay for chemosensitivity testing of human tumors of the central nervous system. Part II: evaluation of patient- and drug–specific variables. J Neurooncol 13:13–24. doi:10.1007/BF00172942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutt CL, Noble M, Chambers AF, Cairncross JG (2000) Differential expression of drug resistance genes and chemosensitivity in glial cell lineages correlate with differential response of oligodendrogliomas and astrocytomas to chemotherapy. Cancer Res 60:4812–4818 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden AT, Waziri AE, Lochhead RA, Fusco D, Lopez K, Ellis JA, Kang J, Assanah M, McKhann GM, Sisti MB, McCormick PC, Canoll P, Bruce JN (2008) Identification of A2B5 + CD133–tumor-initiating cells in adult human gliomas. Neurosurgery 62:505–515. doi:10.1227/01.neu.0000316019.28421.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohgaki H, Dessen P, Jourde B, Horstmann S, Nishikawa T, Di Patre PL, Burkhard C, Schuler D, Probst-Hensch NM, Maiorka PC, Baeza N, Pisani P, Yonekawa Y, Yasargil MG, Lutolf UM, Kleihues P (2004) Genetic pathways to glioblastoma: a population-based study. Cancer Res 64:6892–6899. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens GC, Orr EA, DeMasters BK, Muschel RJ, Berens ME, Kruse CA (1998) Overexpression of a transmembrane isoform of neural cell adhesion molecule alters the invasiveness of rat CNS-1 glioma. Cancer Res 58:2020–2028 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potti A, Forseen SE, Koka VK, Pervez H, Koch M, Fraiman G, Mehdi SA, Levitt R (2004) Determination of Her-2/neu overexpression and clinical predictors of survival in a cohort of 347 patients with primary malignant brain tumors. Cancer Invest 22:537–544. doi:10.1081/CNV-200026523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prag S, Lepekhin EA, Kolkova K, Hartmann-Petersen R, Kawa A, Walmod PS, Belman V, Gallagher HC, Berezin V, Bock E, Pedersen N (2002) NCAM regulates cell motility. J Cell Sci 115:283–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger L, Rieger J, Winter S, Streffer J, Esser P, Dichgans J, Meyermann R, Weller M (2000) Evidence for a constitutive, verapamil-sensitive, non-P-glycoprotein multidrug resistance phenotype in malignant glioma that is unaltered by radiochemotherapy in vivo. Acta Neuropathol 99:555–562. doi:10.1007/s004010051160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum ML, Gerosa MA (1984) Stem cell sensitivity. Prog Exp Tumor Res 28:1–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutka JT, Ivanchuk S, Mondal S, Taylor M, Sakai K, Dirks P, Jun P, Jung S, Becker LE, Ackerley C (1999) Co-expression of nestin and vimentin intermediate filaments in invasive human astrocytoma cells. Int J Dev Neurosci 17:503–515. doi:10.1016/S0736-5748(99)00049-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarissky M, Lavicka J, Kocanova S, Sulla I, Mirossay A, Miskovsky P, Gajdos M, Mojzis J, Mirossay L (2005) Diazepam enhances hypericin-induced photocytotoxicity and apoptosis in human glioblastoma cells. Neoplasma 52:352–359 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H, Yoshida K, Ikeda E, Asou H, Inaba M, Otani M, Kawase T (1998) Expression of the neural cell adhesion molecule in astrocytic tumors: an inverse correlation with malignancy. Cancer 82:1921–1931. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19980515)82:10%3c1921::AID-CNCR16%3e3.0.CO;2-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shervington A, Lu C (2008) Expression of multidrug resistancegenes in normal and cancer stem cells. Cancer Invest 26:535–542. doi:10.1080/07357900801904140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoshan Y, Nishiyama A, Chang A, Mörk S, Barnett GH, Cowell JK, Trapp BD, Staugaitis SM (1999) Expression of oligodendrocyte progenitor cell antigens by gliomas: implications for the histogenesis of brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:10361–10366. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.18.10361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, Bonn VE, Hawkins C, Squire J, Dirks PB (2003) Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res 63:5821–5828 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, Squire JA, Bayani J, Hide T, Henkelman RM, Cusimano MD, Dirks PB (2004) Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature 432:396–401. doi:10.1038/nature03128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strojnik T, Rosland GV, Sakariassen PO, Kavalar R, Lah T (2007) Neural stem cell markers, nestin and musashi proteins, in the progression of human glioma: correlation of nestin with prognosis of patient surfoval. Surg Neurol 68:133–144. doi:10.1016/j.surneu.2006.10.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulla I, Fagula J, Santa M (1987) Three observations of familial incidence of the central nervous system neoplasms. Zentralbl Neurochir 48:168–170 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Bossanyi P, Diete S, Dietzmann K, Warich-Kirches M, Kirches E (1997) Immunohistochemical expression of P-glycoprotein and glutathione S-transferases in cerebral gliomas and response to chemotherapy. Acta Neuropathol 94:605–611. doi:10.1007/s004010050756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waha A, Baumann A, Wolf HK, Fimmers R, Neumann J, Kindermann D, Astrahantseff K, Blumcke I, von Deimling A, Schlegel U (1996) Lack of prognostic relevance of alterations in the epidermal growth factor receptor-transforming growth factor-α pathway in human astrocytic gliomas. J Neurosurg 85:634–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia CL, Du ZW, Liu ZY, Huang Q, Chan WY (2003) A2B5 lineages of human astrocytic tumors and their recurrence. Int J Oncol 23:353–361 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung WKA (1989) In vitro chemosensitivity testing and its clinical application in human gliomas. Neurosurg Rev 12:197–203. doi:10.1007/BF01743984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]