Abstract

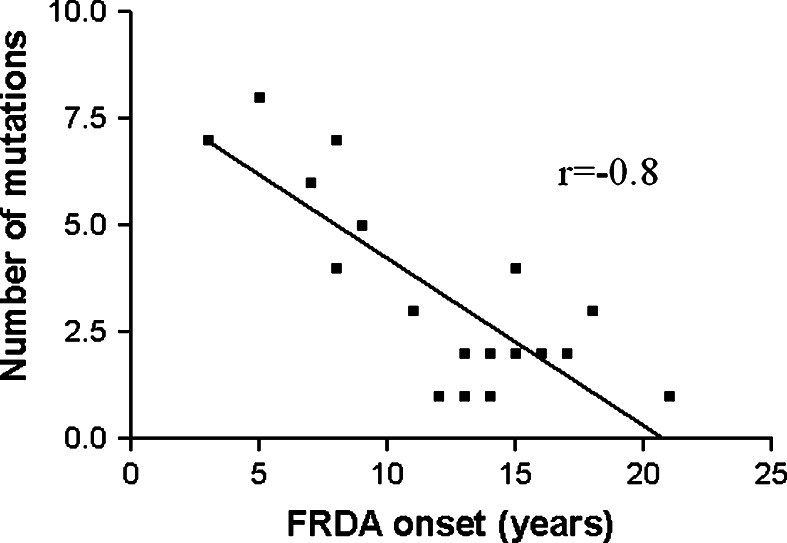

Friedreich’s ataxia (FRDA) is an autosomal recessive neurodegenerative disorder caused by decreased expression of the protein Frataxin. Frataxin deficiency leads to excessive free radical production and dysfunction of chain complexes. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) could be considered a candidate modifier factor for FRDA disease, since mitochondrial oxidative stress is thought to be involved in the pathogenesis of this disease. It prompted us to focus on the mtDNA and monitor the nucleotide changes of genome which are probably the cause of respiratory chain defects and reduced ATP generation. We searched about 46% of the entire mitochondrial genome by temporal temperature gradient gel electrophoresis (TTGE) and DNA fragments showing abnormal banding patterns were sequenced for the identification of exact mutations. In 18 patients, for the first time, we detected 26 mtDNA mutations; of which 5 (19.2%) was novel and 21 (80.8%) have been reported in other diseases. Heteroplasmic C13806A polymorphisms were associated with Iranian FRDA patients (55.5%). Our results showed that NADH dehydrogenase (ND) genes mutations in FRDA samples were higher than normal controls (P < 0.001) and we found statistically significant inverse correlation (r = −0.8) between number of mutation in ND genes and age of onset in FRDA patients. It is possible that mutations in ND genes could constitute a predisposing factor which in combination with environmental risk factors affects age of onset and disease progression.

Keywords: Friedreich’s ataxia (FRDA), MtDNA, NADH dehydrogenase (ND) genes, Mutation, TTGE

Introduction

Friedreich ataxia (FRDA) is an autosomal recessive neurodegenerative disorder with an incidence of approximately 1 in 50,000. FRDA is characterized by progressive gait and limb ataxia, reduced tendon reflexes in the legs, loss of position sense, dysarthria, and pyramidal weakness of the legs (Harding 1981). The age of onset is usually around puberty, almost always before 25 years with a slow progression of the disease (Geffroy et al. 1976). The chromosomal locus for FRDA (9q13) was reported in 1988 (Campuzano et al. 1996) and in 97% of FRDA patients there is an expansion of an unstable GAA trinucleotide repeat in intron 1. Normal individuals have 7–34 repeats, while FRDA patients have expansions of 66 repeats or greater (Cossi et al. 1997).

The FRDA gene encodes a widely expressed 210-aa protein, Frataxin, which is located in mitochondria (Babcock et al. 1997). Although frataxin function is still unknown, yeast strains carrying a disruption in the Frataxin homolog gene (YFH1) showed a severe defect of mitochondrial respiration (Wilson and Roof 1997; Foury and Talibi 2001) and loss of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) (Foury and Cazzalini 1997; Ramazzotti et al. 2004) associated with elevated intramitochondrial iron (Wilson and Roof 1997; Foury and Talibi 2001; Ramazzotti et al. 2004).

NADH ubiquinone reductase (complex I) is the first and one of the largest catalytic complexes of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system. Defects of this complex either alone or in combination with other complexes are probably the most frequently observed defect in respiratory chain (RC). This predominance of complex I dysfunction suggests that its structure or function is relatively easily perturbed (Cooper et al. 1992). Dysfunction of the mitochondrial RC is seen in patients with neurological disease including Alzheimer disease (AD) (Kish et al. 1992), Parkinson disease (PD) (Schapira et al. 1990), Multiple sclerosis (MS) (Heales et al. 1999; Lu et al. 2000), and Friedreich’s ataxia (FRDA) (Bradley et al. 2000; Rotig et al. 1997).

Complex I is particularly vulnerable to mutation. The purpose of this present report was to investigate the areas of mtDNA, assumed to be of special interest, with regard to FRDA and study the relationship between point mutations in coding areas and this disease. The areas of mtDNA investigated are parts of 16s rRNA, ND1, ND2, ND3, ND4L, ND4, ND5, and ND6 genes (NADH dehydrogenase). These parts include about 46% of the whole of mtDNA. Subunits of ND are involved in complex I (NADH-coenzyme Q reductase) in the electron transport chain and since we previously detected a large scale deletion (~8.7 kb) in this area (Houshmand et al. 2006), these parts of mtDNA are assumed to be hot spots in Friedreich’s ataxia. Regarding heteroplasmic mtDNA mutations, a cell can compensate for a reduced number of wild-type mtDNA molecules until a certain threshold is met and apoptosis occurs or the functions of that cell are otherwise compromised (Wallace et al. 2001). When enough cells in a tissue are so affected clinical disease occurs. The threshold is dependent on the specific mutation as well as the cell type.

Although direct DNA sequencing has been the gold standard of mutation identification, its sensitivity is often listed as being able to detect proportions of the minor species (heteroplasmy) down to 20–40%, even using the low-end value. This means that all samples with near 0–20%, heteroplasmy will be missed or interpreted as a homoplasmic polymorphism. Thus, the DNA sequencing works best as an adjunct test to use in parallel with a heteroplasmy screening assay, not to replace the heteroplasmy screening assay (Wong et al. 2002). Therefore, for detection of mutations in these areas, we used temporal temperature gradient gel electrophoresis (TTGE) for rapid screening of mtDNA mutations.

Patients and Methods

Patients

We studied 18 patients (8 females and 10 males) from 18 unrelated families with diagnosis of FRDA regarding their clinical aspects. We basically adopted the clinical criteria of Harding (1981) and Geffroy et al. (1976). We also chose 48 healthy controls (23 females and 25 males) matched for age, sex, ethnicity, and geographical origin. Control subjects had no signs of FRDA when enrolled in the study. All of the patients and the control group were informed about the aims of the study and they gave their informed consents to the genetic analysis. Patients were referred for assessment by consultant neurologists in Iran.

Sizing of GAA Repeats

DNA was isolated from peripheral blood samples using a DNA extraction kit (DNAfast Kit-Genfanavaran, Tehran, Iran). A portion of the FRDA gene was amplified by using the Expand Long Template PCR System (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and the 5200Eco (5′-GGG CTG GCA GAT TCC TCC AG-3′) and 5200Not (5′-TAA GTA TCC GCG CCG GGA AC-3′) primers (Campuzano et al. 1996). The GAA repeat length was calculated according to the size of the PCR product (457 + 3n bp, n = number of GAA triplets).

Temporal Temperature Gradient Gel Electrophoresis (TTGE)

TTGE clearly distinguished heteroplasmic from homoplasmic mutations, and it was sensitive enough to detect heteroplasmic mutations at as low as 4% in DNA fragments as large as 1 kb (Wong et al. 2002). Following PCR, the products are heated and allowed to cool gradually, which results in the formation of heteroduplex DNA if sequence heterogeneity is present. In the presence of mtDNA heteroplasmy, the sequence difference between the two species in the heteroduplexes results in a physical bulge at the site of the sequence mismatch, and leads to decrease in local melting temperature. The DNA fragments from controls and patients were analyzed simultaneously. The relative amounts of band intensity were quantitated with Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Any DNA fragments showing differences in banding patterns between the controls and patients were sequenced to identify exact mutations (Tan et al. 2002).

Nine segments, ranging in size from 280 to 957 bp, were amplified by PCR and assayed by TTGE. The primers used in PCR, the sizes of PCR products, temperature ranges, and ramp rates of the TTGE analysis are listed in Table 1. Each segment is named based on the gene or genes it encoded. Amplification was carried out using DNA thermal cyclers (Eppendorf, master cyclers, 5330) in 50 μl of solution. PCR products were denatured at 95°C for 30 s and slowly cooled to 45°C for a period of 45 min at a rate of 1.1°C/min. TTGE was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Dcode Universal Mutation Detection Systems, BioRad, Hercules, CA). Ten microliters of the denatured and reannealed PCR products was loaded onto the gel. Electrophoresis was carried out at 140 V for 5–6 h at a constant temperature increment of 1–2°C/h, as shown in Table 1. The temperature range was determined by computer simulation (Win Melt software; Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Table 1.

TTGE conditions and primer sequences

| Segment | Size (bp) | Position | Primers (5′–3′) | T m (°C) | Temperature range (°C) | Ramp rate (°C/min) | Gel (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ND1 | 957 | 3,187–4,144 | F: CTCAACTTAGTATTATACCC | 59 | 55–64 | 1.8 | 4 |

| R: TCGGGCGTATGCTGTTCG | |||||||

| ND1& 2 | 539 | 4,111–4,650 | F: CTGTTCTTATGAATTCGAACA | 60 | 57–64 | 1.6 | 6 |

| R: GGAAATACTTGATGGCAGCT | |||||||

| ND2-1 | 939 | 4,491–5,430 | F: GTCATCTACTCTACCTACTT | 58 | 53–67 | 1.8 | 4.5 |

| R: TGTATGTTCAAACTGTCATT | |||||||

| ND2-2 | 280 | 5,461–5,740 | F: CCCTTACCACGCTACTCCTA | 57 | 52–60 | 1.2 | 8 |

| R: GGCGGGAGAAGTAGATTGAA | |||||||

| ND4L | 660 | 10,361–11,020 | F: TCTGGCCTATGAGTGACTAC | 60 | 52–70.5 | 2.1 | 6 |

| R: TTCACTGGATAAGTGGCGTT | |||||||

| ND4a | 385 | 11,646–12,030 | F: TCGTAGTAACAGCCATTCTC | 59 | 56–64 | 1.3 | 6 |

| R: TTAATGTGGTGGGTGATGGA | |||||||

| ND4b | 520 | 11,901–12,420 | F: TGCTAGTAACCACGTTCTCC | 57 | 56–59 | 1 | 6 |

| R: TTTGTTAGGGTTAACGAGGG | |||||||

| ND5 | 775 | 13,506–14,280 | F: TCCAAAGACCACATCATCGAAAC | 60 | 56–64 | 1.3 | 6 |

| R: TCAGGGTTCATTCGGGAGGA | |||||||

| ND6 | 657 | 14,184–14,840 | F: ACCAACAAACAATGGTCAACCAG | 59 | 54–61 | 1.2 | 6 |

| R: TTCATCATGCGGAGATGTTG |

Sequencing Analysis

If a band shift or length heteroplasmy pattern was detected by TTGE, it was confirmed with direct DNA sequencing by using ABI 3700 capillary sequencer (Macrogene Company, South Korea). The primers and PCR conditions were described in Table 2. The results of DNA sequence analysis were compared with the published Cambridge sequence (Anderson et al. 1981). Each sequence variation was then checked against the MtDB—Human Mitochondrial Genome Database (MtDB 2008). Those not recorded in the database were categorized as novel mtDNA variations. The conservation of the novel polymorphism bases were assayed using DNA star software (MEGALIGN program). This software was used to determine the DNA sequence alignment of the ND genes in humans and in other species (chimpanzee, cow, dog, horse, and mouse).

Table 2.

Primer sequences and PCR conditions for sequencing analysis

| Segment | Size (bp) | Nucleotide position | Gene included | Primers (5′–3′) | PCR conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ND1 | 1,463 | 3,187–4,650 | 16s rRNA, ND1, ND2 |

F: CTCAACTTAGTATTATACCC R: GGAAATACTTGATGGCAGCT |

95: 50″, 58: 55″, 72: 50″ (30 cycle); 72: 10′ |

| ND2 | 1,249 | 4,491–5,740 | ND2 |

F: GTCATCTACTCTACCTACTT R: GGCGGGAGAAGTAGATTGAA |

95: 55″, 56.5: 1′, 72: 55″ (35 cycle); 72: 10′ |

| ND3 | 1,499 | 10,361–11,860 | ND3, ND4L, ND4 |

F: TCTGGCCTATGAGTGACTAC R: GAGGTTAGCGAGGCTTGCTA |

95: 55″, 58.5: 1′, 72: 55″ (30 cycle); 72: 10′ |

| ND4 | 519 | 11,901–12,420 | ND4, ND5 |

F: TGCTAGTAACCACGTTCTCC R: TTTGTTAGGGTTAACGAGGG |

95: 50″, 57: 1′, 72: 55″ (30 cycle); 72: 10′ |

| ND5 | 1,334 | 13,506–14,840 | ND5, ND6 |

F: TCCAAAGACCACATCATCGAAAC R: TTCATCATGCGGAGATGTTG |

95: 55″, 59: 1′, 72: 55″ (30 cycle); 72: 10′ |

Statistical Analysis

Fisher’s exact probability test was used to examine the association between two groups. Values of P < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the GraphPad Prism software.

Results

The age range of patients and controls were 10–32 and 12–34 years, respectively. The age of FRDA onset in our patients was 12.2 ± 4.5 (Mean ± SD). The (GAA)n repeats of FRDA patients were observed in both alleles, ranging from 256 to 991 GAA repeats. Patients with GAA expansion repeats more frequently showed absence of tendon reflexes and abnormalities in: (a) position and vibration sense, (b) feet (Pes Cavus), and (c) ECG findings.

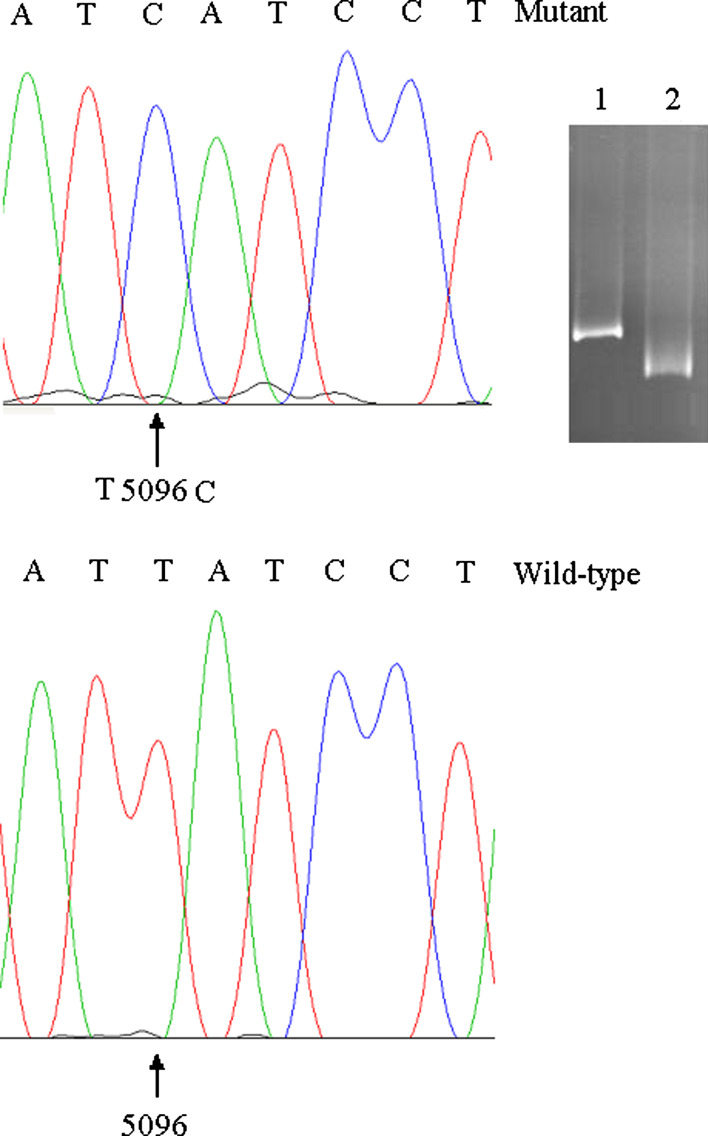

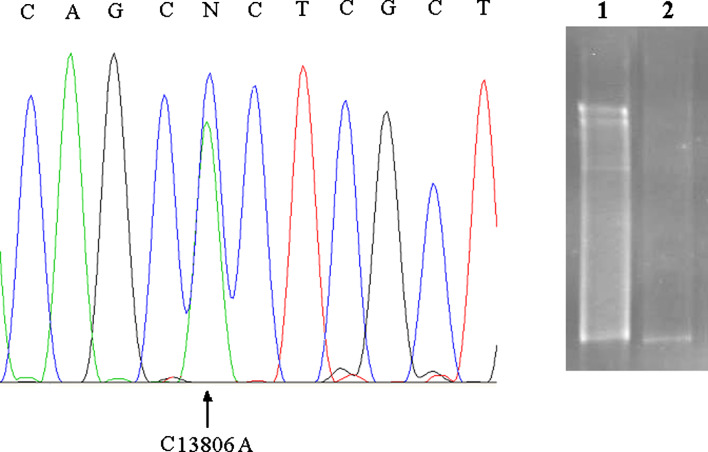

TTGE analyses were carried out on a total of 18 patients and 48 healthy controls. Normal controls of the same ethnicity were also genotyped to establish the frequency of mutations. On TTGE analysis, a single band shift represents a homoplasmic nucleotide substitution (Fig. 1, lane 1) and a multiple banding pattern represents a heteroplasmic mutation (Fig. 2, lane 1). DNA fragments showing abnormal banding patterns on TTGE analysis were sequenced for the identification of exact mutations. The analyzed mtDNA sequences were compared with those of the published sequence (MtDB 2008). TGGE analysis of the mitochondrial genome of the 18 patients detected 26 mutations (25 homoplasmic and 1 heteroplasmic banding patterns) distributed relatively equally in the coding regions of mtDNA. Among them 5 (19.2%) were novel (Table 3) and 21 (80.8%) have been reported in other diseases (Table 4). The results of alignment revealed that the conservation of novel polymorphism bases (C3588T, C4616T, C13806A), (C14130T), and (C10607A) were high, moderate, and low, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Detection and identification of a homoplasmic mtDNA mutation in FRDA patient by TTGE and sequencing. Lane 1, homoplasmic band shift belong to FA patient. Lane 2, wild type. Sequencing result revealed T5096C mutation

Fig. 2.

Detection of heteroplasmic mtDNA SNP by TTGE and sequencing. Lane 1, heteroplasmic multiband pattern belongs to FRDA patient. Lane 2, wild type. Sequencing result revealed C13806A mutation

Table 3.

Novel mtDNA SNPs found in FRDA

| Gene | NT change | NT conservation | AA residue | No. of Ind. | Hetero/Homo | No. of control | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ND1 | C3588T | High | Pro | 1 (5.5%) | Homo | 0 | 0.272 |

| ND2 | C4616T | High | Asn | 1 (5.5%) | Homo | 0 | 0.272 |

| ND4L | C10607A | Low | Leu | 1 (5.5%) | Homo | 0 | 0.272 |

| ND5 | C13806A | High | Ala | 10 (55.5%) | Hetero | 4 (8.34%) | 0.0003 |

| ND5 | C14130T | Moderate | Thr | 1 (5.5%) | Homo | 0 | 0.272 |

NT, Nucleotide; AA, acid amine; No. of Ind., number of individuals; Hetero: Heteroplasmy; Homo: Homoplasmy; No. of control: Number variations found in controls; Conserved: conserved sequence blocks were compared with chimpanzee, cow, dog, horse, mouse, and human

Table 4.

Reported mtDNA SNPs found in FRDA

| Gene | NT change | AA residue | No. of Ind. | Hetero/Homo | No. of control | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ND1 | G3591A | Leu | 3 (16.6%) | Homo | 1 (2.08%) | 0.0731 |

| ND1 | C3696T | Ile | 3 (16.6%) | Homo | 0 | 0.0178 |

| ND2 | T4688C | Ala | 4 (22%) | Homo | 1 (2.08%) | 0.0174 |

| ND2 | G4991A | Gln | 3 (16.6%) | Homo | 0 | 0.0178 |

| ND2 | T5096C | Ile | 1 (5.5%) | Homo | 1 (2.08%) | 0.474 |

| ND2 | C5460T | Ala → Thr | 1 (5.5%) | Homo | 0 | 0.272 |

| ND4 | T10873C | Pro | 1 (5.5%) | Homo | 2 (4.16%) | 1.0 |

| ND4 | T10885C | Phe | 1 (5.5%) | Homo | 0 | 0.272 |

| ND4 | A11467G | Leu | 5 (27.7%) | Homo | 3 (6.35%) | 0.0297 |

| ND4 | A11566G | Met | 1 (5.5%) | Homo | 0 | 0.272 |

| ND4 | G11719A | Gly | 8 (44.4%) | Homo | 4 (8.34%) | 0.0019 |

| ND5 | G12372A | Leu | 3 (16.6%) | Homo | 1 (2.08%) | 0.0731 |

| ND5 | G13590A | Leu | 1 (5.5%) | Homo | 1 (2.08%) | 0.474 |

| ND5 | G13708A | Ala → Thr | 2 (11%) | Homo | 0 | 0.0713 |

| ND5 | A13966G | Thr → Ala | 1 (5.5%) | Homo | 0 | 0.272 |

| ND5 | A14070G | Ser | 1 (5.5%) | Homo | 0 | 0.272 |

| ND6 | G14305A | Ser | 1 (5.5%) | Homo | 1 (2.08%) | 0.474 |

| ND6 | G14364A | Leu | 1 (5.5%) | Homo | 0 | 0.272 |

| ND6 | T14470C | Gly | 2 (11%) | Homo | 1 (2.08%) | 0.1783 |

| ND6 | A14527G | Gly | 1 (5.5%) | Homo | 0 | 0.272 |

| ND6 | G14569A | Ser | 1 (5.5%) | Homo | 0 | 0.272 |

NT, Nucleotide; AA, acid amine; No. of Ind., number of individuals; Hetero, Heteroplasmy; Homo, Homoplasmy; No. of control, Number variations found in controls

Our results showed that ND genes mutations in FRDA samples were higher than normal controls (P < 0.001). All of the mutations were in mRNA genes. Mutations were subsequently analyzed in two groups: (1) point mutations found in protein-encoding structural genes without amino acid replacement or synonym mutations (at 23 loci) and (2) point mutations found in structural genes with amino acid replacement. The three mutations (C5460T, G13708A, A13966G) resulting in amino acid replacements (Table 4) were at amino acid residues with low evolutionary conservation.

Discussion

The expansion of the GAA repeat in intron 1 of the FRDA gene results in a reduction of frataxin expression. Although skeletal muscle cell involvement is not a prominent clinical feature of patients with FA, it has been shown that frataxin is absent or severely reduced in skeletal muscle cell of FA patients (Campuzano et al. 1996; Cossi et al. 1997). Our 18 patients were homozygous for an expanded (GAA)n repeat in FRDA gene. The size of GAA expansion observed in our patients, ranging from 256 to 991, reflects the instability of this expansion during transmission.

In this report we present a comprehensive study of mtDNA base changes in FRDA. Among the 26 distinct mutations, 5 were observed for the first time and 21 have been reported in other disease (MtDB 2008). The 26 mutations found in the coding region were: 3 in ND1 (NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1), 5 in ND2, 1 in ND4L, 5 in ND4, 7 in ND5, and 5 in ND6.

The result of DNA sequence alignment with other species revealed that the novel heteroplasmic C13806A was highly conserved. This mutation has been found in 10 sporadic FRDA cases (55.5%) with 40–65% heteroplasmy levels. In one patient (with two FRDA siblings) and healthy mother, this mutation too was found. The degree of heteroplasmy in siblings was about 65% relative to wild-type allele, but the degree of heteroplasmy in mother was about 45% by TTGE. Although, till date, most of the polymorphisms in mitochondrial diseases have been seen in homoplasmic state, in this study, we found a heteroplasmic C13806A that does not change amino acid.

Two of our patients had optic atrophy and we found a homoplasmic point mutation at position 13708 in ND5 gene that G (Ala) alters to A (Thr). The 13708 mutation have previously been demonstrated in multiple families with LHON (Johns and Berman 1991) and most likely represent synergistic or indicator mutations that are in linkage disequilibrium with the primary pathogenetic mutation.

We demonstrate that base changes rate in ND genes of patients was higher than control (P < 0.001). Figure 3 shows statistically significant inverse correlation (r = −0.77) between number of mutations in ND genes and age of onset in FRDA patients. These mutations are not effective by themselves but a high level of mutation may indicate mtDNA instability and thus indicate deleterious mutations in mtDNA. The findings of the current study indicate that collection of mtDNA mutations may be a predisposing factor which in combination with environment risk factors could have an affect on age of onset and FRDA progression.

Fig. 3.

Correlation between age of onset and number of mutations in ND genes

Iron accumulation in the mitochondria of patients with FRDA would result in hypersensitivity to oxidative stress as a consequence of Fenton reaction (Fe2+-catalyzed production of hydroxyl radicals). As reactive oxygen species (ROS) are continuously generated by the respiratory chain, they may cause significant oxidative damage to mtDNA (for example mtDNA deletions or mutations) if not efficiently eliminated (Wei 1998).

It should be noted that transcription of mitochondrial genome produced two polycistronic primary transcripts that are processed by endonuclease to yield the mature rRNA, tRNA, and mRNA molecules. Thus, nucleotide changes anywhere in the genome affecting the folding and secondary structure of the RNA precursors are potentially detrimental to RNA processing. Additional biochemical and molecular studies of RNA processing and protein expression should be investigated in cell cultures to elucidate the biological effect of these sequence variations before any pathogenic significance can be assigned (Tan et al. 2002). However, further investigations on ND genes and other genes may shed new light on the molecular pathogenesis of FRDA.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Tarbiat Modares University (TMU). We thank all patients for providing blood samples for scientific research as well as Special Medical Center (Tehran, Iran), whose cooperation and support is essential in our work. The study was approved by National Institute for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (NIGEB) Human Research Ethics committee.

References

- Anderson S, Bankier AT, Barrel BG et al (1981) Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature 290:457–465. doi:10.1038/290457a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock M, de Silva D, Oaks R et al (1997) Regulation of mitochondrial iron accumulation by Yfh1p, a putative homolog of frataxin. Science 276:1709–1712. doi:10.1126/science.276.5319.1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley J, Blake JC, Chamberlain S, Thomas PK, Cooper JM, Schapira AHV (2000) Clinical, biochemical and molecular genetic correlations in Friedreich’s ataxia. Hum Mol Genet 9(2):275–282. doi:10.1093/hmg/9.2.275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campuzano V, Monermini L, Molto MD, Pianese L, Cossee M (1996) Friedreich’s ataxia: autosomal recessive disease caused by an intronic GAA triplet repeat expansion. Science 271:1423–1427. doi:10.1126/science.271.5254.1423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JM, Mann VM, Krige D, Schapira AHV (1992) Human mitochondrial complex I dysfunction. Biochim Biophys Acta 1101:198–203. doi:10.1016/S0005-2728(05)80019-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossi M, Schmitt M, Campuzano V (1997) Evolution of the Friedreich’s ataxia trinucleotide repeat expansions: founder effect and permutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:7452–7457. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.14.7452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foury F, Cazzalini O (1997) Deletion of the yeast homologue of the human gene associated with Friedreich’s ataxia elicits iron accumulation in mitochondria. FEBS Lett 411:373–377. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00734-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foury F, Talibi D (2001) Mitochondrial control of iron homeostasis. A genome wide analysis of gene expression in a yeast frataxin deficient mutant. J Biol Chem 276:7762–7768. doi:10.1074/jbc.M005804200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geffroy G, Barbeau A, Breton G (1976) Clinical description and roentgenologic evaluation of patients with Friedreich’s ataxia. Can J Neurol Sci 3:279–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding AE (1981) Friedreich’s ataxia: a clinical and genetic study of 90 families with an analysis of early diagnostic criteria and intrafamilial clustering of clinical features. Brain 104:589–620. doi:10.1093/brain/104.3.589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heales SJR, Bolanos JP, Stewart VC, Brookes PS, Land JM, Clark JB (1999) Nitric oxide, mitochondria and neurological disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1410:215–228. doi:10.1016/S0005-2728(98)00168-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houshmand M, Shariat Panahi SM, Nafisi S, Soltanzadeh A, Alkandari FM (2006) Identification and sizing of GAA trinucleotide repeat expansion, investigation for D-loop variations and mitochondrial deletions in Iranian patients with Friedreich’s ataxia. Mitochondrion 6:87–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns DR, Berman J (1991) Alternative, simultaneous complex I mitochondrial DNA mutations in Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 174:1324–1330. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(91)91567-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kish SJ, Bergeron C, Rajput A, Dozic S, Masdrogiacomo F, Chang L (1992) Brain cytochrome oxidase in Alzheimers disease. J Neurochem 59:776–779. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09439.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu F, Selak M, O’Connor J et al (2000) Oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA and activity of mitochondrial enzymes in lesions of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 177:95–103. doi:10.1016/S0022-510X(00)00343-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MtDB—Human Mitochondrial Genome Database (2008) http://www.genpat.uu.se/mtDB/

- Ramazzotti A, Vanmansart V, Foury F (2004) Mitochondrial functional interactions between frataxin and Isu1p, the iron-sulfur cluster scaffold protein, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett 557:215–220. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(03)01498-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotig A, de Lonlay P, Chretien D et al (1997) Aconitase and mitochondrial iron-sulphur protein deficiency in Friedreich ataxia. Nat Genet 17:215–217. doi:10.1038/ng1097-215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapira AHV, Cooper JM, Dexter D, Clark JB, Jenner P, Marsden CD (1990) Mitochondrial complex I deficiency in Parkinsons disease. J Neurochem 54:823–827. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb02325.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan DJ, Bai RK, Wong LJC (2002) Comprehensive scanning of somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations in breast cancer. Cancer Res 62:972–976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace DC, Lott MT, Brown MD, Kerstann K (2001) Mitochondria and neuro-ophthalmologic diseases. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D (eds) The metabolic & molecular bases of inherited disease, 8th edn. McGraw-Hill, New York, pp 2425–2509 [Google Scholar]

- Wei YH (1998) Oxidative stress and mtDNA mutations in human evolution and disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 217:53–63 [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RB, Roof DM (1997) Respiratory deficiency due to loss of mitochondrial DNA in yeast lacking the frataxin homologue. Nat Genet 16:352–357. doi:10.1038/ng0897-352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong LJC, Liang MH, Kwon H, Park J, Bai RK, Tan DJ (2002) Comprehensive scanning of the entire mitochondrial genome for mutations. Clin Chem 48:1901–1912 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]