Abstract

The developmental changes of the sodium channel and construction of synapse connection were studied in cerebral cortical pyramidal neurons of rats at different age groups. We used whole-cell patch-clamp recordings to characterize electrophysiological properties of cortical neurons at different age stages, including the sodium currents, APs evoked by depolarizing current and short-term plasticity of the eEPSCs. The result shows that the sodium currents undergo a hyperpolarizing shift in activation process and acceleration of activation and inactivation with age. The maximal sodium current also increased with maturation, and the evident difference appeared from P7–P11 (with the day of birth as P0) to P12–P15 group. The tendency of the sodium current density changes which exhibited the same properties as that of sodium current, showed the significant increases from P19–P21 to P ≥ 22 group. The APs’ parameters exhibited the age-dependent changes except the threshold, including the increase of the peak amplitude from P ≤ 6 to P16–P18 groups, and the curtailment of duration and the time-to-peak with age. The amplitude of 1st eEPSC increased with maturation, and STP displays depression at all observed groups. In addition, although STP also exhibited depression in response to last three stimulations in P ≥ 22 group, the 2nd response showed the tendency of facilitation compared with the younger age groups. Our results indicated that the cerebral cortical pyramidal neurons of rats are undergoing marked changes in the characteristics of their sodium channels with maturation, which play a critical role in synaptogenesis and construction of the neuronal network.

Keywords: Cortical neurons, Maturation, Sodium channels, Action potential, Evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents, Short-term plasticity

Introduction

Brain undergoes a series of developmental changes including neurogenesis and synaptogenesis after birth, understanding the crucial mechanisms of that could provide clues to recognize the pathophysiological characters of a variety of psychiatric and neurological disorders e.g., recurrent depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, epilepsy, head injury, and Alzheimer’s disease (Anisman et al. 2008; Vaillend et al. 2008). Proper brain development is achieved by strict spatiotemporal control of neurogenesis, cell differentiation and migration. One first and critical step of cortex development is the generation and proliferation of neuronal cells. Pyramidal neurons as the principle cells, which represent the major output neurons of the cerebral cortex, integrate and transfer information from extra-cortical input and local circuits to distant cortical areas and sub-cortical structure (Dégenètais et al. 2002). The developmental changes of these neurons, including morphological to structural, are all in accordance with the requirement in their function. For most vertebrate organs and tissues, development primarily occurs during embryogenesis, whereas postnatal changes are primarily concerned with growth. But the central nervous system is unusual in that a considerable amount of morphological development, cell differentiation and acquisition of function takes place during postnatal development (Noback and Strominger 1995; Akazawa et al. 1995). In rats, early postnatal development of the cerebral cortex (1–10 days) consists, almost exclusively, of growth and proliferation of neurons and, to a lesser extent, glial processes (Eayrs and Goodhead 1959; Altman and Das 1965). According to Eayrs and Goodhead (1959), maximal growth of axons occurs during days 6–19th of postnatal development, while the proliferation of dendrites takes place during days 18–24th of postnatal development. Accompanied with the proliferation processes of neurons, the number of synaptic junctions is progressively increasing and reaches adult values around the 20–25th day of postnatal development. A sharp increase of the number of synaptic junctions occurs between days 12–20th of postnatal development (Aghajanian and Bloom 1967). This is a complex process based on a precise sequence of cellular events which regulated temporally and spatially.

In previous research, there has been a proof for an enhancement in the mammalian neuronal excitability (Xia and Haddad 1994) during brain development, which is along with the increase in voltage-dependent sodium current density (McCormick and Prince 1987; Huguenard et al. 1988) and sodium channel expression (Felts et al. 1997; Biella et al. 2007). Some other reports showed that the sodium currents also undergo functional changes during postnatal development, for example a hyperpolarization shift of the voltage dependence of activation (6.2 mV) in older (postnatal day 21) neocortical neurons (Cummins et al. 1994). Voltage-dependent sodium current is an essential element of action potential initiation and propagation in excitable cells (Catterall 2000; Goldin et al. 2000), which mostly result from the channel activation, while the channel inactivation contributes to action potential attenuation (Jung et al. 1997).

Cortical neurons are embedded in a dense, complex network and targeted by a great many individual synapses. Both excitatory and inhibitory synapses continuously release transmitter as a result of action potentials within network interconnections. Evoked excitatory postsynaptic current which reflects the network activity is instrumental in determining the excitability of any given neuron. On the other hand, synapses exhibit different short-term plasticity patterns, either synaptic depression or synaptic facilitation. This short-term modification is based on changes in the probability of presynaptic transmitter release, which is reported for several types of synaptic connections (Bolshakov and Siegelbaum 1995; Choi and Lovinger 1997; Pouzat and Hestrin 1997; Reyes and Sakmann 1999) and postsynaptic feedback (Rebola et al. 2007). During the brain development, there are many factors to decide or influence the synapses formation, structure and function, which could be correlated with known physiological functions by determining the spread of electrical activity among cortical neurons, influencing information processing in neuronal networks, and changing the establishment of specific synaptic connections. However, only few studies explored whether the establishment of synaptic contacts and functional integration into network activity are associated with the maturation of sodium channels of cortical neurons. In this paper, we employed whole-cell patch-clamp recordings to characterize the electrophysiological properties of somatosensory cortex pyramidal neurons in acutely dissociated brain slices from rats at various postnatal ages, and to determine whether there is a significant co-operation between the changes of synaptogenesis and the sodium channels of cortical neurons during the postnatal development in rats.

Materials and Methods

Brain Slice Preparations

The brain slices were prepared from Sprague–Dawley rats, of either sex, aged P5–P30 (with the day of birth as P0). All procedures were performed according to the international guidelines on the ethical use of animals. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane and decapitated. The brain was rapidly removed (<60 s) and placed in ice-cold cutting solution containing (in mM): 125 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1 CaCl2, 7 MgCl2, 20 d-glucose, pH 7.4, saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2. Coronal slices (400 μm thickness) were cut with a Vibratome (Campden) and slices were incubated on cell culture inserts (8 μm pore diameter, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) covered by a thin layer of cutting solution and surrounded by a humidified 95% O2 and 5% CO2 atmosphere at room temperature (25°C). After at least one hour incubation, slices were transferred to a submerged recording chamber with continuous flow (2–3 ml/min) of artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) that contained (in mM) 124 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 d-glucose, pH 7.4. The upright infrared microscope (Olympus BX51W1) was used to check the condition of the cell which was used for subsequent patch-clamp recording. The experiment was performed on the neurons of layers III–V in the somatosensory cortex, which were selected by their appropriate and almost same size (soma diameter = 15 ± 5 μm), pyramidal soma and regular spiking pattern in response to depolarizing current pulses in current clamp configuration. Data were acquired by using the whole-cell patch clamp technique at 37°C.

Whole-Cell Recordings

The electrophysiological recordings were performed with the conventional whole-cell recording configuration. The patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass (1.2/1.0 mm; Quanshui Experimental Instrument) on a horizontal puller (P-97, Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA). Pipettes had resistances between 2 and 4 MΩ when filled with an internal solution containing (in mM): 130 K-gluconate, 10 HEPES, 4 Mg–ATP, 0.3 GTP–Na, 0.2 EGTA, 8 NaCl (pH 7.3, 295 ± 5 mOsm). The seal resistance was >1 GΩ and the series resistance were between 8 and 16 MΩ. When whole-cell configuration was achieved, we allowed the cells to stabilize for 5 min before recording. In voltage-clamp experiment, cells were held at −65 mV and then a series of voltage steps (from −80 to +55 mV, increment was 15 mV) were applied. The channels recorded in this experiment were confirmed by tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1 μM, Sigma). In current clamp mode, action potentials (APs) were induced by injecting depolarizing current pulses (200 pA) of 300 ms duration. The values of the threshold, amplitude, duration and time to peak of the first spike were measured.

Recording of Stimulus-Evoked Excitatory Postsynaptic Currents

For stimulus-evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents, a glass electrode (3–5 MΩ) filled with ACSF was placed on dendrites area and 50–70 μm away from the cell bodies being recorded. Picrotoxin (the GABAA receptor blocker, 50 μM, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to the solution in order to block the GABAergic input. 5-pulse train stimulations at 10 Hz were given to elicit evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (eEPSCs) at the voltage clamp configuration. Stimulation strength was twice the adequate stimulus intensity which can evoke current trace. The interval between trains was 10 s. Currents were identified by their constant latency and a single peak for all five responses in the train. The baseline was taken immediately before the onset of each stimulus train. The analysis of the first response (1st eEPSC) of 5-pulse train stimulations was used to evaluate eEPSCs, and short-term plasticity (STP) was quantified by normalizing the amplitude of all five responses to that of the first response.

Acquisition and Data Analysis

All the recordings were obtained using an Axopatch 700A amplifier (Axon Instruments, Burlingame, CA, USA), and digitized at sampling intervals of 10–50 μs using a Digidata 1320AD/DA converter (Axon Instruments). Stimulation, acquisition, and data analysis were controlled with pClamp 9.0 (Axon Instruments). Statistics and data plotting were done with Origin 7.5 (Origin Lab, Northampton, MA) and SPSS 16.0. All quantitative data in the text and figures are expressed as mean ± SEM unless stated otherwise, and statistical significance was tested using one-way ANOVA, LSD-test and Student’s t-test.

Results

Developmental Changes of Sodium Currents From Cortical Neurons at Different Stages of Maturation

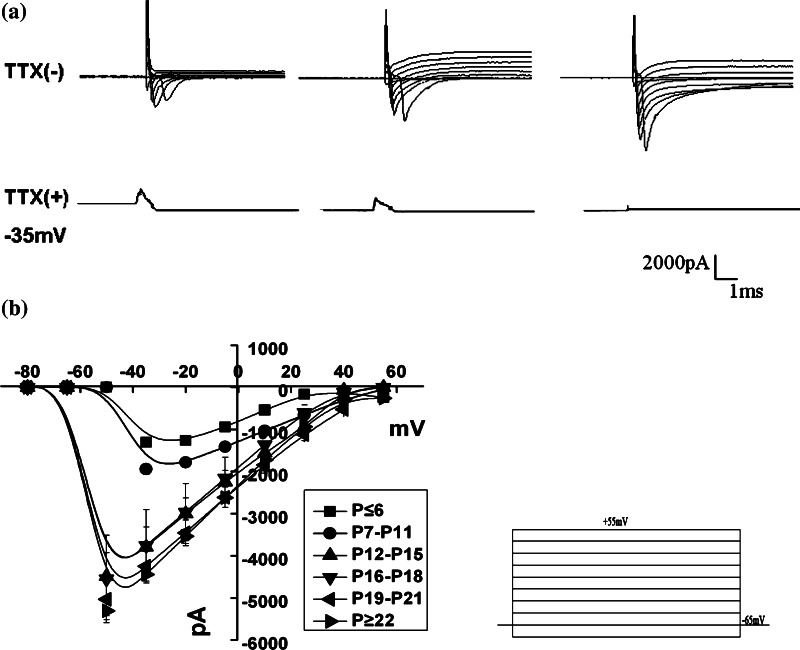

The voltage-gated Na+ current responsible for generating action potentials in cortical pyramidal neurons was characterized in terms of the steady-state and kinetic parameters of activation and inactivation (Biella et al. 2007). Figure 1a shows a series of inward current recordings obtained from cortical neurons of rats at different stages on whole-cell voltage-clamp mode. Noticeably, these inward currents were highly sensitive to the Na+ channel blocker as currents elicited at the test potential of −35 mV became negligible during perfusion with extracellular saline containing 1 μM TTX. Figure 1b shows the current amplitude/voltage relationship of neurons at a voltage range between −80 and +55 mV with a holding potential of −65 mV, obtained from six different development stages (P ≤ 6, P7–P11, P12–P15, P16–P18, P19–P21 and P ≥ 22). As predicted by comparison of the current traces in Fig. 1, the maximal current amplitude increased obviously in P12–P15 compared with P ≤ 6 and P7–P11 groups (one-way ANOVA and LSD-test, P < 0.01), then reached a steady stage in P12–P15, P16–P18, P19–P21 and P ≥ 22 groups (one-way ANOVA and LSD-test, P > 0.05). As shown, the inward currents turned on and reached the maximal peak amplitude at −35 mV in neurons of P ≤ 6 and P7–P11 groups, while at −50 mV in P12–P15, P16–P18, P19–P21 and P ≥ 22 groups. The voltage dependence of activation reveals a significant shift to more negative potentials (from −35 to −50 mV) in neurons with age, which showed the same tendency of developmental changes as hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons (Costa 1996).

Fig. 1.

Developmental changes of sodium current (evoked by a series of 100 ms voltage steps from a holding potential of −65 mV to potential ranging from −80 to +55 mV in 15 mV increments) in different development stages of cortical neurons. a Na+ current traces elicited at the potentials indicated by the protocol (on right bottom) were obtained from cortical neurons of P5 (left), P16 (middle) and P25 (right) rats, respectively. The bottom traces was taken from the corresponding cells at −35 mV during TTX application (1 μM); b current–voltage relationships of the six different stages in cortical neurons (P ≤ 6, n = 13; P7–P11, n = 11; P12–P15, n = 11; P16-P18, n = 10; P19–P21, n = 10; P ≥ 22, n = 23 groups). The voltage dependence of channel activation appears to shift to more negative potential during postnatal development. The average maximal current amplitude obtained at −35 mV for P ≤ 6 and P7–P11 groups and at −50 mV for other four groups (P ≤ 6: −1,306.6 ± 109.7 pA, n = 13; P7–P11: −1,944.8 ± 122.9 pA, n = 11; P12–P15: −4,494.3 ± 564.7 pA, n = 11; P16–P18: –4,552.1 ± 1,042 pA, n = 10; P19–P21: −5,033.4 ± 396.5 pA, n = 10; P ≥ 22: −5,306.7 ± 217.4 pA, n = 23; one-way ANOVA and LSD test). Values are showed in means ± SEM

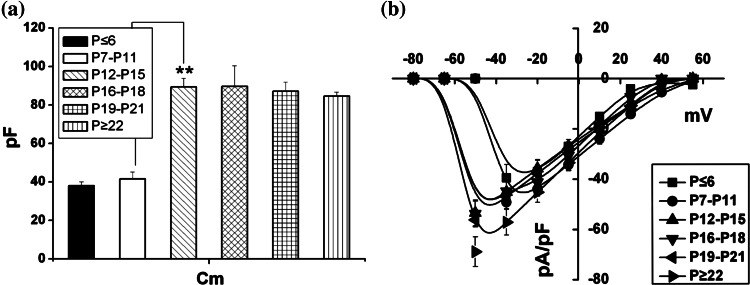

In addition, it was found that test neurons’ membrane capacitance (Cm) increased during the postnatal development and then reached a steady-state. The remarkable increase of Cm appeared between P7–P11 and P12–P15 groups (one-way ANOVA and LSD-test, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2a), which indicated that the intrinsic membrane properties of the neurons underwent an acute change during the first two postnatal weeks. A similar result has been reported in CA3 hippocampal pyramidal neurons (Tyzio et al. 2003), however the latter showed a continuous increasing state until P25, which could indicate that the pyramidal neurons from different areas of brain exhibited the variable state.

Fig. 2.

Na+ current density in cortical neurons at different age stages. a Mean membrane capacitance for cortical neurons (P ≤ 6: 38.0 ± 2.06 pF, n = 13; P7–P11: 41.6 ± 3.52 pF, n = 11; P12–P15: 89.4 ± 4.44 pF, n = 11; P16–P18: 89.6 ± 10.8 pF, n = 10; P19–P21: 87.1 ± 4.74 pF, n = 10; P ≥ 22: 86.7 ± 5.88 pF, n = 23); b The Na+ current density–voltage relationship in the six different development stages. The maximal current density changed with age. (P ≤ 6: −39.5 ± 5.34 pA/pF, n = 13; P7–P11: −49.2 ± 2.57 pA/pF, n = 11; P12–P15: −53.4 ± 5.17 pA/pF, n = 11; P16–P18: −53.7 ± 5.04 pA/pF, n = 10; P19–P21: −56.3 ± 2.73 pA/pF, n = 10; P ≥ 22: −68.9 ± 5.88 pA/pF, n = 23). Values are showed in means ± SEM. Asterisks mark significant differences between the two groups linked by line (one-way ANOVA and LSD test), P < 0.01

The related Na+ current density was calculated according to the equation: pF/pC = I Na/Cm, where pF/pC stands for the Na+ current density and I Na is the Na+ current amplitude as shown in Fig. 1b. The maximal current density increased slightly with age but the significant difference was emerged in P ≥ 22 group compared with the other groups (one-way ANOVA and LSD-test, P < 0.05). Figure 2b shows the current density/voltage relationship over a voltage range between −80 and +55 mV, which were in accordance with the traces of the current amplitude/voltage relationship, The average current density peaked at −35 mV for P ≤ 6 and P7–11 groups and at −50 mV for P12–15, P16–P18, P19–P21 and P ≥ 22 groups. For P ≤ 6 and P7–P11 groups, the traces presented a linear relationship from −35 mV to +25 mV, while that for other four groups presented a linear relationship from −50 to +40 mV (Fig. 2b). In order to further examine the changes in Na+ channel, we fitted the linear part with standard straight line function to yield the channel conductance and then compared the fitted lines in Fit comparison windows of Origin 7.5 (F-test). It was found that the conductance rapidly increased during the first two postnatal weeks and then maintained a steady-state with age (P ≤ 6:23.0 ± 1.21 nS, n = 13; P7–P11: 23.7 ± 1.39 nS, n = 11; P12–P15: 48.6 ± 0.754 nS, n = 11; P16–P18: 50.5 ± 1.35 nS, n = 10; P19–P21: 51.0 ± 1.04 nS, n = 10; P ≥ 22: 56.9 ± 1.24 nS, n = 23). Also the significant increase between P7–P11 and P12–P15 groups showed the confidence level of 95% (F-test).

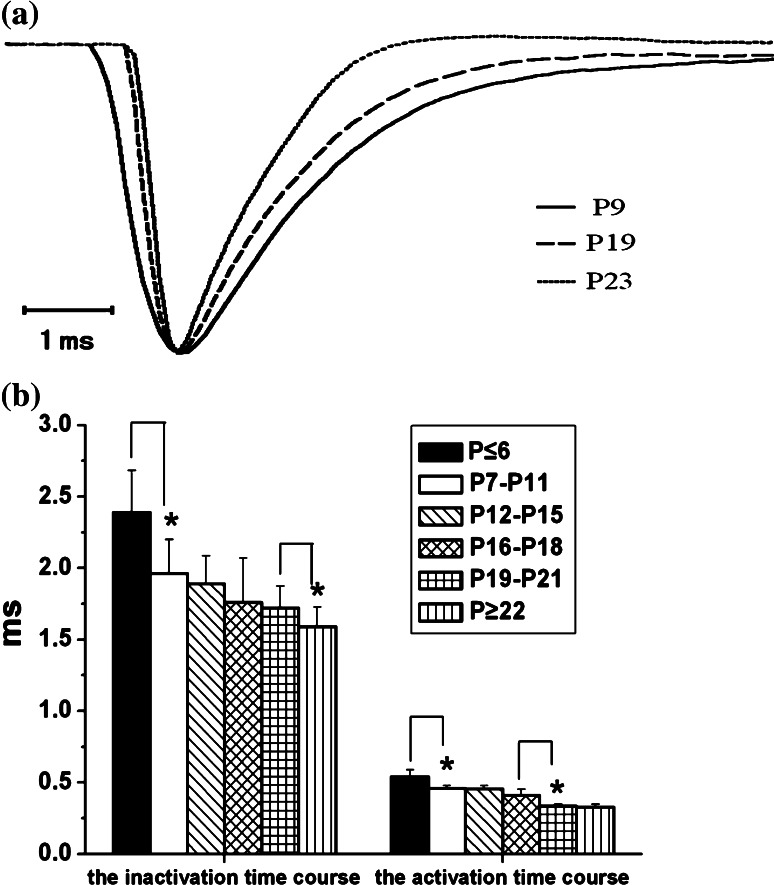

It is noteworthy that I Na in all of the test neurons showed an activation/inactivation component, activation accelerated and inactivation became more rapid with maturation (Fig. 3a). We measured the activation time (from 10 to 90% of peak amplitude) and inactivation time course (tau) (from 70 to 10% of peak amplitude) at −35 mV depolarization pulse. As shown in Fig. 3b, both the activation and inactivation time course shortened with age, but the evident changes of the activation time appeared in between P ≤ 6 and P7–P11 groups and in between P16–P18 and P19–P21 groups, while the significant differences of inactivation time were presented in between P ≤ 6 and P7–P11 groups and in P19–P21 and P ≥ 22 groups (one-way ANOVA and LSD-test, P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

The activation and inactivation time courses of I Na. a I Na induced during depolarization could be divided into the activation and inactivation phases. Traces from different development groups were normalized to a comparable scale to show the activation and inactivation kinetics. Activation time was measured from 10 to 90% of the decline phase, within this case, 0.54, 0.32, and 0.30 ms, for P9 (real line), P19 (dashed), and P23 (dots) rats, respectively. The major part of inactivation phase (from 70 to 10% of peak amplitude) could be well fitted by standard exponential function to yield the time constant values (tau) of 2.19, 1.73, and 1.58 ms, respectively; b the activation and inactivation time courses of I Na decreased with age. (activation time: P ≤ 6: 0.541 ± 0.0487 ms, n = 13; P7–P11: 0.459 ± 0.0200 ms, n = 11; P12–P15: 0.455 ± 0.0232 ms, n = 11; P16–P18: 0.410 ± 0.0427 ms, n = 10; P19–P21: 0.335 ± 0.0115 ms, n = 10; P ≥ 22: 0.329 ± 0.0187 ms, n = 23; inactivation time: P ≤ 6: 2.39 ± 0.293 ms, n = 13; P7–P11: 1.96 ± 0.241 ms, n = 11; P12–P15: 1.89 ± 0.197 ms, n = 11; P16–P18: 1.76 ± 0.308 ms, n = 10; P19–P21: 1.72 ± 0.153 ms, n = 10; P ≥ 22: 1.59 ± 0.139 ms, n = 23). Values are showed in means ± SEM. Asterisks mark significant differences between the two groups linked by line (one-way ANOVA and LSD test), *, P < 0.05

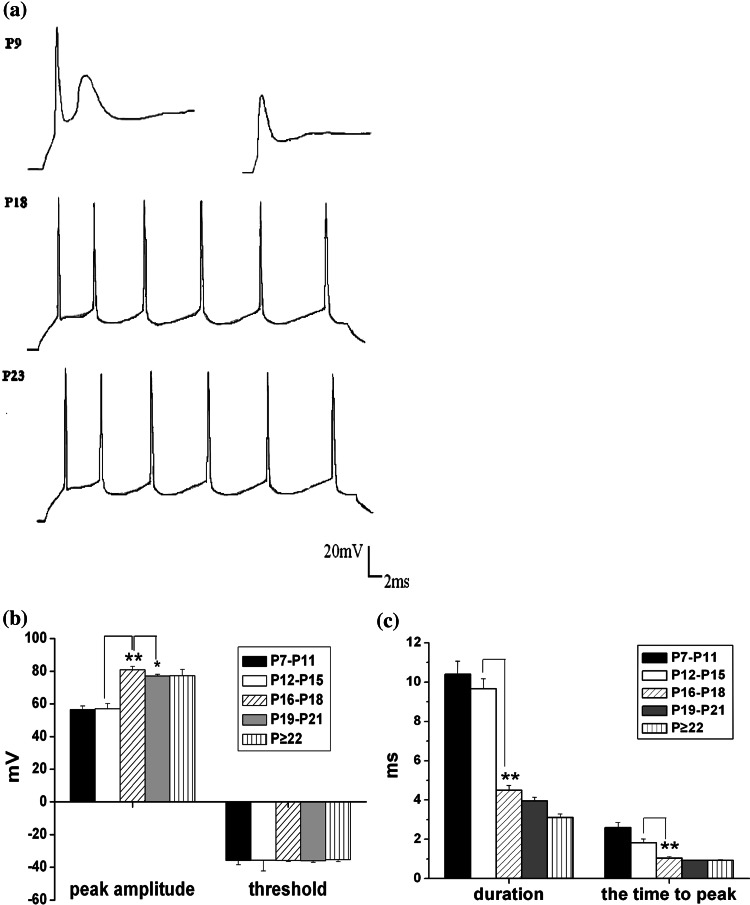

Developmental Changes of Action Potentials in Rats’ Cortical Neurons During Postnatal Maturation

We recorded the action potentials of cortical neurons by applying depolarizing current (200 pA), which is enough to elicit action potential, and evaluated the activity of neurons by the threshold, amplitude, duration, the time to peak (tp) of the 1st action potential (AP).

The postnatal neurons gain the capacity to fire repetitive trains of AP (Annis et al. 1993; Heidi et al. 2003). But in our results, most of the neurons in P ≤ 6 group (n = 8) were not able to emit a typical action potential waveform which was in accordance with that in embryonic 13 (E13) of rat spinal motoneuron reported by Gao and ZIiskind-Conhaim (1998) (Fig. 4a, top right). Additionally, in P7–P11 group, although some neurons (n = 9) could generate the first spike, their second and third spikes exhibited typically diminished in amplitude and prolonged in duration which were called after depolarizing potential (ADP) (Gao and ZIiskind-Conhaim 1998) (Fig. 4a, top left). While in P12–P15 and other older (P16–P18, P19–P21, P ≥ 22) groups, all neurons were able to fire a train of AP without diminished amplitudes or prolonged durations on subsequent spikes (Fig. 4a). Consistent with Gao and ZIiskind-Conhaim (1998), although the AP waveform was changed gradually with the developing transformation of the passive and intrinsic membrane properties including the development of the ionic channel currents, it is showed that the distinct development characters were exhibited at the same point of development stage in different kinds of neurons. In this study, we just statistically analyzed the neurons which can generate one or more typical APs.

Fig. 4.

Intrinsic properties of action potential change during postnatal development. a The original representative voltage traces in response to depolarizing current (200 pA) injections were recorded on cortical neurons from P9 (top), P18 (middle) and P23 (bottom) groups; b the development changes of thresholds and amplitudes of the first action potential in five age groups. (Threshold: −35.8 ± 2.63 mV (n = 9), −35.6 ± 6.67 mV (n = 12), −35.8 ± 0.47 mV (n = 11), −35.9 ± 1.00 mV and −35.3 ± 1.28 mV (n = 10), respectively for P7–P11, P12–P15, P16–P18,P19–P21 and P ≥ 22 groups; Amplitude: P7–P11: 56.5 ± 2.19 mV, n = 9; P12–P15: 57.1 ± 2.99 mV, n = 12; P16–P18: 80.9 ± 1.93 mV; P19–P24: 77.2 ± 0.99 mV, n = 15; P ≥ 25, 77.2 ± 3.94 mV, n = 10); c the age-dependent duration of action potential (P7–P11: 10.4 ± 0.675 ms, n = 9; P12–P15: 9.65 ± 0.528 ms, n = 12; P16–P18: 4.49 ± 0.249 ms, n = 11; P19–P21: 3.95 ± 0.199 ms, n = 15; P ≥ 22: 3.12 ± 0.169 ms, n = 10, respectively) and the time to peak (P7–P11: 2.60 ± 0.256 ms, n = 9; P12–P15: 1.83 ± 0.191 ms, n = 12; P16–P18: 1.05 ± 0.0752 ms, n = 11; P19–P21: 0.922 ± 0.0409 ms, n = 15; and P ≥ 22: 0.920 ± 0.0574 ms, n = 10, respectively). Values are showed in means ± SEM. Asterisks mark significant differences between the two groups linked by line (one-way ANOVA and LSD test), *, P < 0.05 or **, P < 0.01

Consistent with other reports (Belleau and Warren 2000; Zhou and Hablitz 1996; Zhang 2004), our results showed that the amplitude of action potentials increased by 25 mV during the first 3 weeks (one-way ANOVA and LSD-test, P < 0.01), while both the time to peak and duration decreased nearly by 50% when a depolarizing current of 200 pA was injected. It was showed that the maximal amplitude of action potential appeared in P16–P18 group, and then decreased significantly in following development stages (one-way ANOVA and LSD-test, P < 0.05) (Fig. 4b). And the duration shortened remarkably in P16–P18 and other two older groups compared with P7–P11 and P12–P15 groups (one-way ANOVA and LSD-test, P < 0.01) (Fig. 4c). The average values of tp were significantly reduced with age in the same groups compared with P7–P11 and P12–P15 groups (one-way ANOVA and LSD-test, P < 0.01) (Fig. 4c).

Referring to the AP threshold of pyramidal neurons, different reports concerning distinct area of brain varied from one to another. And it was constant with age in our study as Anne-Marie and Alex (2008) reported, whereas some other reports showed that it shifted to hyperpolarizing potentials significantly with maturation (Zhang 2004; Elodie et al. 2005; Zhou and Hablitz 1996) (Fig. 4b).

Developmental Changes of Excitatory Synapses Among Rats’ Cortical Neurons During Postnatal Maturation

To characterize the functional changes of excitatory synapses in the developing cortical neural network, we applied a train of five stimulation pulses at 10 Hz to induce the responses of evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents in the presence of picrotoxin (the GABAA receptor blocker). In P ≤ 6 group, many neurons (n = 9) did not give all these five responses, even the first response was not induced. So we just statistically analyzed the neurons which had generated all these five responses.

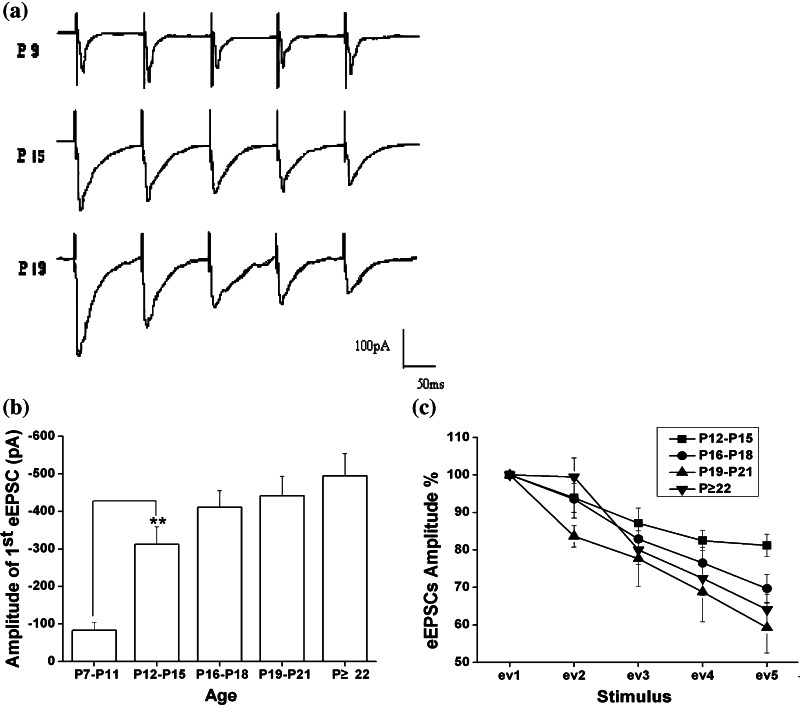

The first response (1st eEPSC) of 5-pulse train stimulations was analyzed for evaluating the functional changes of excitatory inputs for the given neurons. As shown in Fig. 5a and b, the amplitude of 1st eEPSC increased significantly in P12–P15 group (one-way ANOVA and LSD test; P < 0.01) followed by a steady-state in P16–P18 group, and then that of the P19–P21 and P ≥ 22 development groups increased distinctly compared with that in P12–P15 group, even that in P ≥ 22 group was bigger than that in P16–P18 group significantly (one-way ANOVA and LSD test; P < 0.05). The amplitude of 1st eEPSC comparisons among different development stages also reflects a phenomenon of more intensive excitatory input with age.

Fig. 5.

The short-term plasticity (STP) of eEPSCs in cortex at different developmental stages. a The representative STP trace induced by a 10 Hz 5-pluse train stimulations were obtained at P9(top), P15 (middle) and P19 (bottom) day, respectively; b the amplitude of 1st eEPSC increases significantly with age (P7–P11: −83.3 ± 20.6 pA, n = 4; P12–P15: −243.5 ± 33.5 pA, n = 16; P16–P18: −298.1 ± 41.17 pA, n = 21; P19–P21: −441.6 ± 52.0 pA, n = 11; P ≥ 22: −516.24 ± 49.9 pA, n = 8; one-way ANOVA and LSD test, P < 0.05); c short-term plasticity was quantified by normalizing the amplitude of all five responses to that of the first response, so the pooled data show relative EPSC amplitude (EPSCn/EPSC1*100%, n: the number of pulse from 1 to 5) of pyramidal cells in different development stages. Values are showed in means ± SEM. Asterisks mark significant differences between the two groups linked by line (one-way ANOVA and LSD test), *, P < 0.05 or **, P < 0.01

Additionally, in our study, STP of eEPSCs was quantified by normalizing the amplitude of all five responses to that of the first one. In P ≤ 6 and P7–P11 groups, even as the neurons generated all five responses, the maximal response happened randomly, so it had no meaning for statistically analyzing. Thus, we just compared the other four groups qualitatively (P12–P15, P16–P18, P19–P21, P ≥ 22) (Fig. 5c). As illustrated, it was found that, in response to the five stimulus, STP displayed synaptic depression (reduced the magnitude of the summed current) in all researched age groups which did not shift to synaptic facilitation (increase the magnitude of the summed current) completely with age as other previous studies shown (Chen and Roper 2004; Zhang 2004).At the same time, although STP of P ≥ 22 group also exhibited depression in response to last three stimulus (the 3rd to 5th normalized rate of responses: 80.0 ± 3.92%, 72.4 ± 4.52%, 64.1 ± 4.14%, n = 8) in all researched neurons, the 2nd response of nearly 62.5% neurons showed the tendency of facilitation significantly compared with the younger age group (the 2nd normalized rate of responses: P12–P15, 93.9 ± 3.79%; P16–P18, 93.6 ± 5.05%; P19–P21, 83.6 ± 2.85%, n = 11; P ≥ 22, 99.5 ± 5.05%, n = 8; one-way ANOVA and LSD test, P < 0.05).

In addition, we further took a comparison among the fitted line of the last three responses in different development stages (F-test), it was showed that synaptic depression induced by the last three stimulus became significantly larger with age from P12–P15 to P19–P21 groups (F-test, P < 0.05), and the most prominent depression appeared in P19–P21 group, but P ≥ 22 group presented the tendency of reduction on synaptic depression compared with P19–P21 group, and the difference between P ≥ 22 and P19–P21 groups was also significant (F-test, p < 0.05). These data actually suggested that the mechanism of synapses concerned with STP could undergo the developmental changes during maturation.

Discussion

In this paper, we examined electrophysiological properties of rat cortical pyramidal neurons, such as voltage-gated Na+ currents, action potential, eEPSC amplitude and STP, to evaluate the roles of sodium channels in synaptogenesis accompanying the developmental changes of neurons.

Identification of the Cell Type

The cell type was identified according to their morphological and electrophysiological properties. The defining feature of their morphology is the presence of a triangularly shaped soma, a single apical dendrite extending toward the pial surface, multiple basal dendrites, and a single axon (Spruston 2008). Additionally, the spiking pattern we characterized is based on the method described in Vincent and Tell (1999). In this study, the neurons from P12–P15 and older age groups were able to generate 3–8 spikes during the test time (300 ms), and the parameters of 1st AP are similar to the pyramidal neurons previously reported (Luebke and Chang 2007; Karpuk and Vorobyov 2003). So we have reasons to believe that the cells we studied belong to pyramidal neurons.

The Variable Intrinsic Properties of Individual Neurons During the Rat Postnatal Brain Development

The present results indicate that significant changes take place in the properties of Na+ currents during the different stages of maturation. The most remarkable findings were the increase in Na+ current amplitude, the hyperpolarization shift in activation process, and the acceleration of activation and inactivation with maturation. Possible reasons for the increase in Na+ current amplitude during postnatal development might be: (a) an increase in the number of ion channels; (b) an increase in single channel conductance with age which we can exclude from our result; (c) an increase in the opening probability of the ion channels (Kaneko and Saito 1992). In our results, it was found that the Na+ current amplitude and the Na+ current density were all increasing with maturation, but the former showed the acutely changing period in P12–P15 group, whereas the latter showed the significant growth period in P ≥ 22 group. The changes of cell membrane capacitance also exhibited a significant increase between P7–P11 and P12–P15 groups, which indicated that the changes of the voltage-sensitive sodium currents contributed to the corresponding changes of the membrane capacitance, as we control the similar size of the cell body in our tested neurons (Gordan and Manfred 2001). Under the increasing of the Na+ current amplitude steadily with age, a significant difference of the current density in P ≥ 22 group compared with the other groups may result from the membrane capacitance which switched to opposite changes slightly after P19–P21 group, this phenomenon was in accordance with pruning of dendrites in older ages (Smith 1981).

Changes toward more negative potentials (−35 mV of P ≤ 6 and P7–P11 groups to −50 mV of P12–P15 and other older groups) in the voltage-dependence of Na+ current activation curve have been reported before, for example, during the early development of retinal ganglion cells and neurons in the lateral geniculate nucleus of Ferret (Skaliora et al. 1993; Ramoa and McCormick 1994; Schmid and Guenther 1998). The time course of Na+ current is fairly consistent with the report that the acceleration of activation and inactivation of Na+ channel occurred in maturate neurons (Costa 1996), but the results presented that there are two significant shortened processes in time course with maturation whether activation or inactivation. The first change both appeared between P ≤ 6 and P7–P11 groups in time course of activation and inactivation, which was presumably correlated with the expression of different kinds of the sodium channel isoforms (Castillo et al. 1997). The second difference occurred in latter developmental progress, which maybe caused by the changed excitability of tested neurons because of synaptogenesis.

These changes of Na+ currents are likely to have important functional implications. Firstly, the increase of Na+ current amplitude could lead to an enhanced influx of Na+ ions of an action potential in the maturate neurons. Secondly, due to the shift in the process of activation toward more negative membrane potentials, smaller depolarization is required to activate the Na+ current at a given potential. A faster activation and inactivation of Na+ channel are associated with the curtailment of action potential durations and the time-to-peak (Maruyama et al. 2007; Benninger et al. 2003), which affect the spiking patterns of AP. What is more, age-related AP amplitude changes in these cells may result from altered expression of voltage-activated sodium channel subunits (Lu et al. 2004; Erraji-Benchekroun et al. 2005); otherwise, shorter AP duration may also be due to the variable expression of potassium channels such as Kv3.1 and Kv3.2 (Martina et al. 1998); thus these changes clearly reflect the up-regulation of voltage-dependent sodium and potassium conductance during development (Picken and Moody 2003). In our studies, the change in the parameters of AP is agreed with that of sodium currents. Taken together, these aspects indicate that the alterations in the Na+ channel observed in our study may enhance the excitability of mature neurons during postnatal development, which would be in agreement with the observation that action potentials could be frequently elicited in more mature neurons, whereas abortive regenerative events or no action potentials were most frequently observed in immature ones (Holter et al. 2007; Shao et al. 2006).

Developmental Modification of Synaptogenesis in the Cerebral Cortex

Developmental modifications of synaptic properties, including the changes in the synaptic number and structure, are an important facet of the matured brain. Excitatory inputs to neurons in the neocortex were measured by eEPSC after picrotoxin application, we observed that the amplitudes of eEPSC were increased with age, which are likely to reflect both functional maturation of individual synapses such as the increase of the number of receptors, release probability and/or quantum size of presynaptic vesicles and increases in the number of synapses (Takai et al. 2003; Ye et al. 2005).

Previous reports supported the idea that short-term plasticity induced by paired- or multiple-pulse stimulation in synapses generally shows depression at early stages of development, but switches to facilitation at later stages (Chen and Roper 2004; Zhang 2004). It has to be pointed out that the short-term plasticity of eEPSCs is uncertain in P ≤ 6 group and some neurons in P7–P11 group, neither depression nor facilitation; in other words, we could consider that the STP has not been formed because the responses induced by five stimulus pulses happened randomly and most neurons did not give all these five responses. This suggested that the STP is full of association with amount of synapses. From P12–P15 group to P19–P21 group, stimulation at 10 Hz (Fig. 2b) induced a significantly larger short-term synaptic depression with age. The short-term synaptic depression is mainly attributed to the depletion of a readily releasable vesicle pool that occurs with repetitive presynaptic activation resulting in a decline in neurotransmitter release, which may represent a crucial mechanism in neural coding to regulate information processing in the adult cortex (Reig et al. 2006). During maturation, the enhancement of synaptic depression might contribute to the adjustment of the cortical spontaneous activity so as to avoid the hyperexcitability. In P ≥ 22 group, nearly 62.5% researched neurons switched from synaptic depression to facilitation just in response to the 2nd stimulus, but did not turn into facilitation completely as previous reports (Chen and Roper 2004; Zhang 2004). This could be because the specimens we chose were not old enough, of which over 25 days just were in P ≥ 22 group, and the location of tested neurons was in different layer with previous report (Reyes and Sakmann 1999). The other cause may be the stimulation intensity that was set to produce less than one-third of the maximum response in previous report (Zhang 2004), while that we used was double stimulate intensity to generate an enough response (but not the maximum) in order to observe the eEPSC at different age groups. In fact, the responses with 5 train pulses shows non- line relationship of depression in P ≥ 22 group, furthermore, compared with P19–P21 group, the last three responses showed the smaller depression in P ≥ 22 group, which also reflected a combined effect of depression and facilitation. The STP of eEPSCs reflects the changes of the probability of evoked transmitter release, suggesting it is mediated predominantly by presynaptic mechanisms (Bolshakov and Siegelbaum 1995; Choi and Lovinger 1997; Pouzat and Hestrin 1997; Reyes and Sakmann 1999). This developmental decrease in the release probability in normal cortex may be important in the maturation and stabilization of cortical neuronal networks.

Critical Roles of Voltage-Dependent Sodium Channels in the Process of Synaptogenesis During the Postnatal Cortical Development of Rats

The neurons in P ≤ 6 and P7–P11 groups showed smaller sodium currents and less formation of synaptic activities. The five responses with five trains of pulse stimulus actually correspond to the representation of AP in these neurons, which is consistent with Kombian et al. (2000) who proposed that STP requires action potentials for its generation. In our results, most of the neurons in P ≤ 6 and P7–P11 groups did not generate a model AP because of immaturities of sodium channels, correspondingly did not induce all five responses by five trains stimulations. Plus the smallest amplitude of 1st eEPSC, our studies suggested that in rats, early postnatal development of the cerebral cortex (<12 days) mainly consists of growth and proliferation of neurons (Eayrs and Goodhead 1959; Altman and Das 1965), and few formations of synapses.

According to our results, both the amplitude of sodium currents and eEPSCs undergo significant changes between P7–P11 and P12–P15 groups, but the amplitude of sodium currents stands at the steady state while the amplitude of 1st eEPSCs shows an obvious increase from P12–P15 group to P ≥ 22 group, which was consistent with previous studies concerning other areas of the brain and implied that a sharp increase of the number of synaptic junctions formed between days 12th–20th of postnatal development (Aghajanian and Bloom 1967). Other reports concluded that neuronal electrical activity promoted developmental branching of cortical neurons (Uesaka et al. 2005, 2006), as TTX suppressed both neuronal electrical activity and branching of the terminal arborization of axons. Accumulated experimental evidence indicated that both spontaneous and experience-driven electrical activities are essential for engraving and bolstering the structural basis for the functional neuronal network from early in embryonic development through adulthood (Wada 2006). Together with our results, the maturation of electrical activity of pyramidal neurons with the increasing number and the maturate property of sodium channels play important roles in axon development and neuronal circuit formation. Finally, based on the report that electrical activities play important roles in developmental processes including neuronal differentiation, cell migration, formation, and refinement of synaptic connections (Katz and Shatz 1996), our results that slight changes of intrinsic properties and significant switch of synaptogenesis occurred after P12 led us to conclude that the maturation of the intrinsic properties of neurons controlled by gene accelerate the process of synaptic formations, whereas synaptic inputs modify the intrinsic properties of neurons.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that a series of changes in intrinsic properties of neuron and synaptic plasticity were taken place in cortical cortex during postnatal development. Compared with that in immature neurons, the voltage-dependent sodium current in mature ones appears to be activated much easier and faster. A larger amplitude of sodium current and a hyperpolarization shift of voltage dependent sodium channel activation were recorded in rats both P12–P15 and other older groups compared with that in the younger. This is not only concerned with the augment of channel expression, but also the modification of individual channel property as well as variation in subtype expression. Corresponsive changes could be found in the decrease of AP duration and increase of AP amplitude, both of which led to a sharper spike in response to sustained current injection in mature animals. Take consider of the neuron networks, our study on eEPSC indicates that more connections are formed between pre- and post-synaptic neurons in cortical cortex in the mature groups, which is consistent with network formation. In summary, although it has been known that the synaptic formation exhibits a different developmental phase with the maturation of sodium channels, and sodium channels plays important roles in neuronal circuit formation during cortical maturation, the molecular mechanism between them need to explore in depth for our further research.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Guangdong Science-Tech Program (No. 2001331004202516), and the Science Foundation of Life Sciences School, Sun Yat-sen University.

Footnotes

Ke Wang, Jihong Cui, and Yijun Cai contributed equally to this work.

References

- Aghajanian GK, Bloom FE (1967) The formation of synaptic junctions in developing rat brain: a quantitative electron microscopic study. Brain Res 6(4):716–717. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(67)90128-X:10.1016/0006-8993(67)90128-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akazawa C, Ishibashi M, Shimizu C, Nakanishi S, Kagiyama R (1995) A mammalian helix-loop-helix structurally related to the product of Drosophilaproneural gene atonal is a positive transcriptional regulator expressed in the developing nervous system. J Biol Chem 270(15):8730–8738. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.15.8730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Das GD (1965) Postnatal origin of microneurones in the rat brain. Nature 207(5000):953–956. doi:10.1038/207953a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anisman H, Merali Z, Stead JD (2008) Experiential and genetic contributions to depressive- and anxiety-like disorders: clinical and experimental studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 32:1185–1206. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.03.001:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anne-Marie MO, Alex DR (2008) Maturation of intrinsic and synaptic properties of layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons in mouse auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol 99:2998–3008. doi:10.1152/jn.01160.2007:10.1152/jn.01160.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annis CM, Robertson RT, O’Dowd DK (1993) Aspects of early postnatal development of cortical neurons that proceed independently of normally present extrinsic influences. J Neurobiol 24(11):1460–1480. doi:10.1002/neu.480241103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belleau ML, Warren RA (2000) Postnatal development of electrophysiological properties of nucleus accumbens neurons. J Neurophysiol 84:2204–2216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benninger F, Beck H, Wernig M, Tucker KL, Brustle O, Scheffler B (2003) Functional integration of embryonic stem cell-derived neurons in hippocampal slice cultures. J Neurosci 23(18):7075–7083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biella G, Di Febo F, Goffredo D, Moiana A, Taglietti V, Conti L, Cattaneo E, Toselli M (2007) Differentiating embryonic stem–derived neural stem cells show a maturation-dependent pattern of voltage-gated sodium current expression and graded action potentials. Neuroscience 149(1):38–52. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.07.021:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolshakov VY, Siegelbaum SA (1995) Regulation of hippocampal transmitter release during development and long-term potentiation. Science 269(5231):1730–1734. doi:10.1126/science.7569903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo C, Daz ME, Balbi D, Thornhill WB, Recio-Pinto E (1997) Changes in sodium channel function during postnatal brain development reflect increases in the level of channel sialidation. Dev Brain Res 104:119–130. doi:10.1016/S0165-3806(97)00159-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA (2000) From ionic currents to molecular mechanisms: the structure and function of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron 26(1):13–25. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81133-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HX, Roper SN (2004) Tonic activity of metabotropic glutamate receptors is involved in developmental modification of short-term plasticity in the neocortex. J Neurophysiol 92(2):838–844. doi:10.1152/jn.01258.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Lovinger DM (1997) Decreased probability of neurotransmitter release underlines striatal long-term depression and postnatal development of corticostriatal synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:2665–2670. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.6.2665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PF (1996) The kinetic parameters of sodium currents in maturing acutely isolated rat hippocampal CA1 neurons. Dev Brain Res 91(1):29–40. doi:10.1016/0165-3806(95)00159-X:10.1016/0165-3806(95)00159-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins TR, Xia Y, Haddad GG (1994) Functional properties of rat and human neocortical voltage-sensitive sodium currents. J Neurophysiol 71(3):1052–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dégenètais E, Thierry AM, Glowinski J, Gioanni Y (2002) Electrophysiological properties of pyramidal neurons in the rat prefrontal cortex: an in vivo intracellular recording study. Cereb Cortex 12(1):1–16. doi:10.1093/cercor/12.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eayrs JT, Goodhead B (1959) Postnatal development of the cerebral cortex in the rat. J Anat 93(4):385–402 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elodie C, Nathalie D, Daniel JL, Zolta’n M, Serge C, Etienne A (2005) Two populations of layer V pyramidal cells of the mouse neocortex: development and sensitivity to anesthetics. J Neurophysiol 94:3357–3367. doi:10.1152/jn.00076.2005:10.1152/jn.00076.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erraji-Benchekroun L, Underwood MD, Arango V, Galfalvy H, Pavlidis P, Smyrniotopoulos P, Mann JJ, Sibille E (2005) Molecular aging in human prefrontal cortex is selective and continuous throughout adult life. Biol Psychiatry 57(5):549–558. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felts PA, Yokoyama S, Dib-Hajj S, Black JA, Waxman SG (1997) Sodium channel alpha-subunit mRNAs I, II, III, NaG, Na6 and hNE (PN1): different expression patterns in developing rat nervous system. Mol Brain Res 45(1):71–82. doi:10.1016/S0169-328X(96)00241-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao BX, ZIiskind-Conhaim L (1998) Development of ionic currents underlying changes in action potential waveforms in rat spinal motoneurons. J Neurophysiol 80:3047–3061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin A, Barchi R, Caldwell J, Hofmann F, Howe J, Hunter J, Kallen R, Mandel G, Meisler M, Netter Y (2000) Nomenclature of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron 28(2):365–368. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00116-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordan K, Manfred L (2001) Voltage-dependent membrane capacitance in rat pituitary nerve terminals due to gating currents. Biophysical 80:1220–1229. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76098-5:10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76098-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidi L, Bahrey P, Moody WJ (2003) Early development of voltage-gated ion currents and firing properties in neurons of the mouse cerebral cortex. J Neurophysiol 89(4):1761–1773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holter NI, Zuber N, Bruehl C, Draguhn A (2007) Functional maturation of developing interneurons in the molecular layer of mouse dentate gyrus. Brain Res 1186:56–64. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.089:10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huguenard JR, Hamili OP, Prince DA (1988) Developmental changes in Na+ conductances in rat neocortical neurons: appearance of a slowly inactivating component. J Neurophysiol 59(3):778–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung HY, Mickus T, Spruston N (1997) Prolonged sodium channel inactivation contributes to dendritic action potential attenuation in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci 17(17):6639–6646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko Y, Saito T (1992) Appearance and maturation of voltage-dependent conductances in solitary spiking cells during retinal regeneration in the adult newt. J Comp Physiol 170(4):411–425. doi:10.1007/BF00191458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpuk N, Vorobyov V (2003) Spike sequences and mean firing rate in rat neocortical neurons in vitro. Brain Res 973(1):16–30. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(03)02478-8:10.1016/S0006-8993(03)02478-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LC, Shatz CJ (1996) Synaptic activity and the construction of cortical circuits. Science 274(5290):1133–1138. doi:10.1126/science.274.5290.1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kombian SB, Hirasawa M, Mouginot D, Chen XH, Pittman QJ (2000) Short-term potentiation of miniature excitatory synaptic currents causes excitation of supraoptic neurons. J Neurophysiol 83(5):2542–2553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Pan Y, Kao SY, Li C, Kohane I, Chan J, Yankner BA (2004) Gene regulation and DNA damage in the ageing human brain. Nature 429(6994):883–891. doi:10.1038/nature02661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luebke JI, Chang YM (2007) Effects of aging on the electrophysiological properties of layer 5 pyramidal cells in the monkey prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience 150(3):556–562. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.09.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martina M, Schultz JH, Ehmke H, Monyer H, Jonas P (1998) Functional and molecular differences between voltage-gated K+ channels of fast-spiking interneurons and pyramidal neurons of rat hippocampus. J Neurosci 18(20):8111–8125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama A, Ishikawa A, Hosoyama D, Yoshimura Y, Tamura H, Sato H, Fujita I (2007) Developmental changes in electrophysiological properties of layer III pyramidal neurons in macaque visual cortices. Neurosci Res 58(1):154. doi:10.1016/j.neures.2007.06.624 [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Prince DA (1987) Postnatal development of electrophysiological properties of rat cerebral cortical pyramidal neurons. J Physiol 393:743–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noback CR, Strominger NL, Demarest RJ (1995) The human nervous system. Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

- Picken BHL, Moody WJ (2003) Early development of voltage-gated ion currents and firing properties in neurons of the mouse cerebral cortex. J Neurophysiol 89:1761–1773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouzat C, Hestrin S (1997) Developmental regulation of basket/stellate cell-Purkinje cell synapses in the cerebellum. J Neurosci 17(23):9104–9112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramoa AS, McCormick DA (1994) Developmental changes in electrophysiological properties of LGNd neurons during reorganization of retinogeniculate connections. J Neurosci 14(4):2089–2097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebola N, Sachidhanandam S, Perrais D, Cunha RA, Mulle C (2007) Short-term plasticity of kainate receptor-mediated EPSCs induced by NMDA receptors at hippocampal mossy fiber synapses. J Neurosci 27(15):3987–3993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reig R, Gallego R, Nowak LG, Sanchez-Vives MV (2006) Impact of cortical network activity on short-term synaptic depression. Cereb Cortex 16:688–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes R, Sakmann B (1999) Developmental switch in the short-term modification of unitary EPSPs evoked in layer 2/3 and layer 5 pyramidal neurons of rat neocortex. J Neurosci 19(10):3827–3835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid S, Guenther E (1998) Alterations in channel density and kinetic properties of the sodium current in retinal ganglion cells of the rat during in vivo differentiation. Neuroscience 85(1):249–258. doi:10.1016/S0306-4522(97)00644-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao M, Hirsch JC, Peusner KD (2006) Maturation of firing pattern in chick vestibular nucleus neurons. Neuroscience 141(2):711–726. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.03.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaliora I, Scobey RP, Chalupa LM (1993) Prenatal development of excitability in cat retinal ganglion cells: action potentials and sodium currents. J Neurosci 13(1):313–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ZDJ (1981) Organization and development of brain stem auditory nuclei of the chicken: dendritic development in N. laminaris. J Comp Neurol 203(3):309–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruston N (2008) Pyramidal neurons: dendritic structure and synaptic integration. Nat Rev Neurosci 9:206–221. doi:10.1038/nrn2286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai Y, Shimizu K, Ohtsuka T (2003) The roles of cadherins and nectins in interneuronal synapse formation. Curr Opin Neurobiol 13:520–526. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2003.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyzio R, Ivanov A, Bernard C, Holmes GL, Ben-Arii Y, Khazipov R (2003) Membrane potential of CA3 hippocampal pyramidal cells during postnatal development. J Neurophysiol 90:2964–2972. doi:10.1152/jn.00172.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uesaka N, Hirai S, Maruyama T, Ruthazer ES, Yamamoto N (2005) Activity dependence of cortical axon branch formation: a morphological and electrophysiological study using organotypic slice cultures. J Neurosci 25:1–9. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3855-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uesaka N, Ruthazer ES, Yamamoto N (2006) The role of neural activity in cortical axon branching. Neuroscientist 12:102–106. doi:10.1177/1073858405281673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillend C, Poirier R, Laroche S (2008) Genes, plasticity and mental retardation. Behav Brain Res 192:88–105. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2008.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent A, Tell F (1999) Postnatal development of rat nucleus tractus Solitarius neurons: morphological and electrophysiological evidence. Neuroscience 93(1):293–305. doi:10.1016/S0306-4522(99)00109-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada A (2006) Roles of voltage-dependent sodium channels in neuronal development, pain, and neurodegeneration. J Pharmacol Sci 102:253–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y, Haddad GG (1994) Postnatal development of voltage-sensitive Na+ channels in rat brain. J Comp Neurol 345(2):279–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye GL, Yi S, Gamkrelidze G, Pasternak JF, Trommer BL (2005) AMPA and NMDA receptor-mediated currents in developing dentate gyrus granule cells. Dev Brain Res 155:26–32. doi:10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZW (2004) Maturation of layer V pyramidal neurons in the rat prefrontal cortex: intrinsic properties and synaptic function. J Neurophysiol 91(3):1171–1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou FM, Hablitz JJ (1996) Postnatal development of membrane properties of layer I neurons in rat neocortex. J Neurosci 16:1131–1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]