Abstract

Methionine and cysteine residues in proteins are the major targets of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The present work was designed to characterize the impact of methionine and cysteine oxidation upon [Ca2+]i in hippocampal neurons. We investigated the effects of H2O2 and chloramine T(Ch-T) agents known to oxidize both cysteine and methionine residues, and 5, 5′-dithio-bis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB)—a cysteine-specific oxidant, on the intracellular calcium in hippocampal neurons. The results showed that these three oxidants, 1 mM H2O2, 1 mM Ch-T, and 500 μM DTNB, induced an sustained elevation of [Ca2+]i by 76.1 ± 3.9%, 86.5 ± 5.0%, and 24.4 ± 3.2% over the basal level, respectively. The elevation induced by H2O2 and Ch-T was significantly higher than DTNB. Pretreatment with reductant DTT at 1 mM for 10 min completely prevented the action of DTNB on [Ca2+]i, but only partially reduced the effects of H2O2 and Ch-T on [Ca2+]i, the reductions were 44.6 ± 4.2% and 29.6 ± 6.1% over baseline, respectively. The elevation of [Ca2+]i induced by H2O2 and Ch-T after pretreatment with DTT were statistically higher than that induced by single administration of DTNB. Further investigation showed that the elevation of [Ca2+]i mainly resulted from internal calcium stores. From our data, we propose that methionine oxidation plays an important role in the regulation of intracellular calcium and this regulation may mainly be due to internal calcium stores.

Keywords: Reactive oxygen species, Cysteine and methionine oxidation, Intracellular calcium, Inositol triphosphate

Introduction

The oxidative damage theory of aging postulates that the age-dependent accumulation of oxidative damage to macromolecules causes a progressive functional deterioration of cells, tissues, and organ systems that manifests as functional senescence and culminates in death (Harman 1956). Environmental reactive oxygen species (ROS) can cause proteins to be oxidized at a small number of specific sites. Oxidative damage to proteins results in the oxidation of certain amino acid residues, among which oxidation of sulfur-containing amino acids, methionine, and cysteine, is notable because of the susceptibility of these residues to damage (Stadtman 2004; Koc and Gladyshev 2007).

Oxidation of amino acid residues in proteins is known to alter their functional properties, leading to an alteration in cellular homeostasis (Stadtman 1993). For example, α-1 antitrypsin loses its ability to inhibit neutrophils elastase once its Met 351 and Met 358 are oxidized (Taggart et al. 2000)—an event that may cause emphysema. Similarly, HIV-2 protease becomes inactive once its two methionines (Met 76 and Met 95) are oxidized (Davis et al. 2002). In calmodulin, methionine oxidation inhibits the activation of the plasma membrane Ca-ATPase (Yao et al. 1996), and alters activation and regulation of CaMKII (Robison et al. 2007). The reduced methionine at residue 35 of the Alzheimer’s disease-associated amyloid-beta peptide is important for a wide range of neurotoxic and oxidative properties of the peptide (Dai et al. 2007; Crouch et al. 2006; Clementi et al. 2006; Clementi and Misiti 2005). Our previous study also demonstrated that the P/C-type inactivation in voltage-gated K+ channels could be accelerated by methionine oxidation (Chen et al. 2000), and P/Q type calcium current could be enhanced by oxidation of cysteine and methionine (Chen et al. 2002). These findings suggest that oxidation of certain cysteine and methionine residues are critical for the overall cellular function, thereby play a fundamental role in regulating cell physiology.

Increases in ROS and mis-regulation of calcium homeostasis are associated with aging and various diseases of nervous system. The Ca2+ hypothesis reveals that the impaired calcium regulation in neurons and [Ca2+]i elevation are considered as key factors in brain aging (Khachaturian 1994; Foster and Kumar 2002; Mattson and Chan 2003; Toescu and Verkhratsky 2003, 2004; Whalley et al. 2004). Memory processes that depend on intact hippocampal function appear to be particularly age-sensitive (Foster 1999). However, no detailed studies have been performed in rats concerning the impact of cysteine and methionine residues oxidation upon [Ca2+]i in hippocampal neurons.

In the present study, to discern the possible contribution of cysteine or methionine oxidation, the effects of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), chloramine T (Ch-T), and 5, 5′-dithio-bis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) on cultured hippocampal neurons and the cellular signaling pathways were explored. The results will provide evidence to support the methionine oxidation and Ca2+ dysregulation hypothesis.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Ch-T, DTNB, dithiothreitol (DTT), ATP, cyclopiazonic acid (CPA), and caffeine were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). H2O2 was purchased from Merck (Germany). Fura-2/AM (Biotium, Hayward, CA, USA) was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at −20°C. DTNB was dissolved in alcohol. Other general agents were available commercially. All the drugs were prepared as stock solutions and diluted to the final concentrations before application. The final concentration of DMSO was <0.05%.

Cell Culture

Neonatal SD (Sprague-Dawley) rats (day 0–3) of both sexes were obtained from the Experimental Animal Center of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science & Technology. All experimental procedures were approved by the University of Animal Welfare Committee. Neurons were isolated as previously described (Ming et al. 2006) with some modifications. Briefly, hippocampi of neonatal rats were dissected and rinsed in ice-cold dissection buffer containing (in mM, pH 7.20) 137 NaCl, 2.7 KCl, 9.7 Na2HPO4 · 12H2O, and 1.6 KH2PO4. Blood vessels and white matter were removed and tissues were incubated in 0.125% trypsin for 30 min at 37°C. Neurons were collected by centrifugation (1000g, 5 min) and resuspended in Dulbecoo’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and F-12 supplement (1:1) with 10% fetal bovine serum (heat-inactivated, Hyclone), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 U/ml). The cells were seeded at 104–105 per 35 mm2 on poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips and kept at 37°C in 5% CO2 incubator. After 24 h, the culture medium was refreshed and astrocytes were minimized by treating with cytosine (10 μM) on the third day. The culture medium was replaced with fresh medium every 3 days. Experiments were performed on day 5–7.

Calcium Imaging

Digital calcium imaging was performed as described by Ming et al. (2006). The cells were washed three times by artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mM): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.3), then loaded with 1 μM Fura-2/AM in ACSF for 30 min at 37°C to remove the excess extracellular Fura-2/AM (Yermolaieva et al. 2001). EGTA (100 μM) was substituted for CaCl2 in calcium-free solution. Coverslips were then mounted on a chamber positioned on the movable stage of an inverted microscope (Olympus IX-70, Japan), which is equipped with a calcium imaging system ((TILL-Photonics, Gräfelfingen, Germany). The cells were superfused by ACSF at a rate of 2 ml/min for 10 min. Fluorescence was excited at wavelengths of 340 nm for 150 ms and 380 nm for 50 ms at 1 s interval by a monochromator (Polychrome IV) and the emitted light was imaged at 510 nm with a video camera (TILL-Photonics Imago) through a X-70 fluor oil immersion lens (Olympus) and a 460-nm long-pass barrier filter. F 340 /F 380 fluorescence ratio was recorded and analyzed by TILL vision 4.0 software, which was used as an indicator of [Ca2+]i independent of intracellular fura-2 concentration. All experiments were repeated at least three times using different batches of cells.

Statistical Analysis

The amplitude of [Ca2+]i transient represents the difference between baseline concentration and the transient peak response to the stimulation. The normalized variations of [Ca2+]i (ΔF/F) were analyzed. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA was used for the statistical analysis by using SPSS 12.0 software. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Oxidants-Induced Increase of [Ca2+]i in Rat Hippocampal Neurons

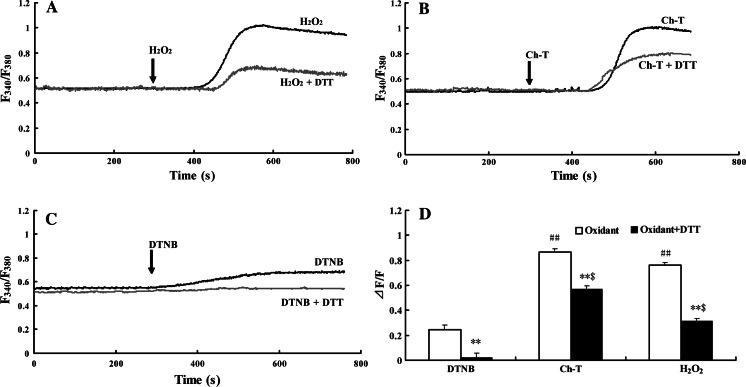

Application of 1 mM H2O2 induced an elevation of [Ca2+]i in cultured hippocampal neurons, it was detected at about 3–5 min after administration, and rapidly reached a plateau within 6.0 min. The peak value of the increase was 76.1 ± 3.9% over base line (n = 60). This increase lasted for at least 10 min (Fig. 1a). In another group of cells, application of 1 mM Ch-T obviously increased [Ca2+]i by 86.5 ± 5.0% over base line in cultured hippocampal neurons (Fig. 1b). In addition, 500 μM DTNB also increased [Ca2+]i, but relatively mild (24.4 ± 3.2% over base line) (Fig. 1c). The results indicated that exogenous oxidants significantly increased [Ca2+]i in hippocampal neurons, and the elevation induced by H2O2 and Ch-T was much higher than DTNB, the difference was statistically different (P < 0.01 for H2O2 and Ch-T vs. DTNB, Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

Elevation of [Ca2+]i by oxidants was inhibited by pretreatment with 1 mM DTT. (a) H2O2, (b) Ch-T, and (c) DTNB were applied to primary cultured hippocampal neurons, respectively with or without pretreatment of 1 mM DTT for 4 min. Single administration of 10 mM H2O2, 1 mM Ch-T, and 500 μM DTNB stimulated [Ca2+]i increase by 76.1 ± 3.9% (n = 63), 86.5 ± 5.0% (n = 66), and 24.4 ± 3.2% over baseline (n = 65), respectively. [Ca2+]i increase was collected as F 340/F 380 ratios. Arrows indicate the time when H2O2, Ch-T, or DTNB was applied. (d) Summary of maximal response in [Ca2+]i for each oxidant and changes in [Ca2+]i with preincubation of 1 mM DTT. [Ca2+]i variations were analyzed according to the normalized fluorescence ∆F/F. **P < 0.01 Oxidants + DTT vs. Oxidants; ## P < 0.01 H2O2, Ch-T vs. DTNB; and $ P < 0.01 H2O2 + DTT, Ch-T + DTT vs. DTNB

Effect of Reducing Agent DTT on the Oxidants-Induced Rises of [Ca2+]i

The neurons were treated with 1 mM DTT, an agent to reduce the sulfhydryl groups. As shown in Fig. 1, pretreatment with 1 mM extracellular DTT for 10 min completely prevented the action of DTNB on [Ca2+]i, but only partially reduced the effects of H2O2 and Ch-T on [Ca2+]i; the reductions were 44.6 ± 4.2% and 29.6 ± 3.1% over basal level for H2O2 and Ch-T, respectively (P < 0.01 vs. oxidants). The elevation of [Ca2+]i induced by H2O2 and Ch-T after pretreatment with DTT was statistically higher than that induced by single administration of DTNB (P < 0.01 for H2O2 + DTT, Ch-T + DTT vs. DTNB, Fig. 1d).

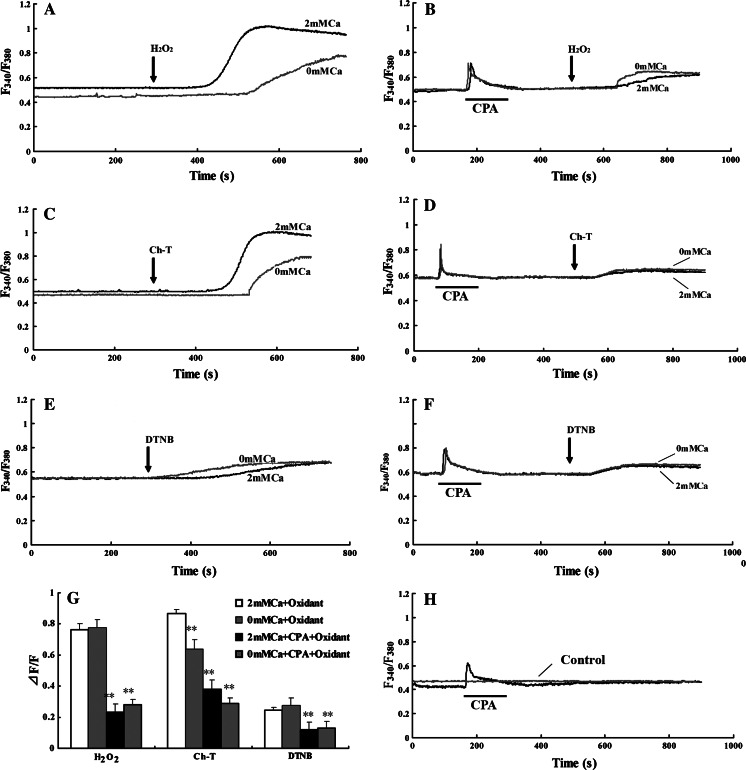

The Sources of Ca2+ Rise Induced by Oxidants

To identify the sources of Ca2+ mobilization induced by oxidants, the respective role of extracellular Ca2+ influx and intracellular Ca2+ stores was examined in oxidants-mediated [Ca2+]i changes in cultured hippocampal neurons. First, the neurons were alternately superfused with Ca2+-containing and Ca2+-free artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) in the presence of oxidants. As shown in Fig. 2c, Ch-T-induced [Ca2+]i rise was obviously reduced by 23.0 ± 1.8% over resting level in Ca2+-free medium (P < 0.01 vs. Ca2+-containing medium, Fig. 2g). However, as shown in Fig. 2a and e there was no statistical differences in [Ca2+]i rise induced by H2O2 and DTNB between Ca2+-containing and Ca2+-free media (Fig. 2g), indicating that extracellular Ca2+ influx was only in part responsible for Ch-T-induced elevation of [Ca2+]i, but not for [Ca2+]i rise induced by H2O2 and DTNB. Furthermore, cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) was used to deplete intracellular Ca2+ stores. CPA alone elicited a transient [Ca2+]i rise by 42.8 ± 2.3% over basal level, (Fig. 2h), indicated reversible loss of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. The time-matched basal controls without oxidant treatment were stable. After the hippocampal neurons were preincubated with CPA for 10 min, oxidants were administrated. The depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores by CPA in Ca2+-containing medium significantly suppressed the elevation of [Ca2+]i to 23.3 ± 2.0%, 38.1 ± 3.2%, and 12.0 ± 3.7% over resting level induced by H2O2, Ch-T, and DTNB respectively (Fig. 2b, d, f, g). The results suggest that the CPA-sensitive endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ stores was the major source of [Ca2+]i increase induced by oxidants, and extracellular Ca2+ influx also plays a role in Ch-T-induced [Ca2+]i rise. When the hippocampal neurons were pretreated with CPA in Ca2+-free ACSF, however, it did not completely block the oxidant-induced [Ca2+]i increase (Fig. 2b, d, f, g). These results suggested that oxidant-mediated [Ca2+]i increase also depended on additional pathways, besides the extracellular influx and the internal reservoir in the ER.

Fig. 2.

Effect of Ca2+-free solution and CPA on oxidants-induced [Ca2+]i rise. (a, c, e) The Ca2+-free solution did not inhibit the action of H2O2 and DTNB, but significantly inhibited the action of Ch-T. 2 mM Ca,Ca2+-containing ACSF and 0 mM Ca, Ca2+-free ACSF were applied. (b, d, f) Application of 1 mM CPA to deplete the intracellular calcium store significantly attenuated the oxidants-induced [Ca2+]i increases in hippocampal neurons. However, pretreatment with CPA in Ca2+-free ACSF did not completely block oxidants-induced [Ca2+]i increase in hippocampal neurons. (g) Oxidant-mediated [Ca2+]i increase depends on the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores and Ca2+ influx. (h) Effect of 1 mM CPA on [Ca2+]i in primary cultured hippocampal neurons. CPA alone elicited a transient [Ca2+]i rise by 42.8 ± 2.3% (n = 15, in four independent experiments). The time-matched basal controls without oxidants were stable. The experiments were repeated at least three times. **P < 0.01 compared to untreated cells. Results are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Arrows indicate the time when H2O2, Ch-T, and DTNB were applied

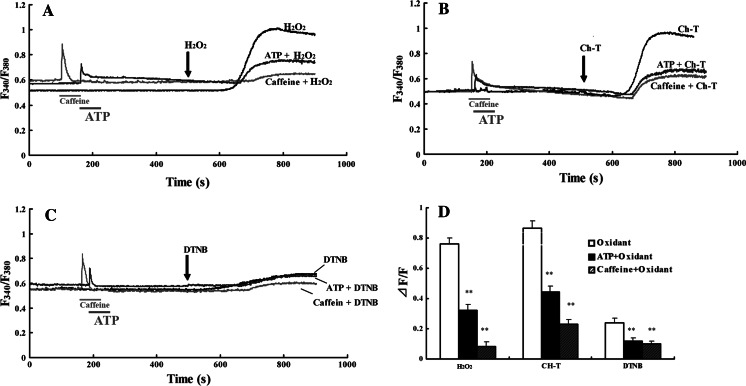

Internal Ca2+ Stores Contributed to the Oxidants-Induced Enhancement of [Ca2+]i

Hippocampal neurons were exposed to 2 mM caffeine (IP3 receptor antagonists) or 100 μM ATP (IP3-sensitive calcium stores depletor) prior to applying the oxidants. As shown in Fig. 3, ATP significantly inhibited the elevation of [Ca2+]i evoked by H2O2, Ch-T, and DTNB; the rates of inhibition were 57.6 ± 4.1%, n = 46; 48.7 ± 4.9%, n = 53; and 51.2 ± 3.0%, n = 49, respectively (P < 0.01 vs. oxidants). The inhibition of the [Ca2+]i rise is more significant by caffeine; the rates of inhibition were 89.1 ± 2.9%, n = 51; 73.2 ± 4.9%, n = 47; 59.4 ± 1.8%, n = 56, respectively (P < 0.01 vs. oxidants), which suggest that IP3-sensitive Ca2+ stores are mainly responsible for the oxidants-induced Ca2+ mobilization.

Fig. 3.

Oxidants mobilize Ca2+ from IP3-releasable Ca2+ stores in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. (a–c) Pretreatment with 100 μM ATP or 2 mM caffeine, almost prevented the [Ca2+]i increase induced by H2O2, Ch-T, and DTNB. (d) The summary of changes in [Ca2+]i by each oxidant after pretreatment with 100 μM ATP or 2 mM caffeine. Results are presented as mean ± S.E.M. **P < 0.01 compared to oxidants

Discussion

In the present study, we report that cysteine and methionine residue oxidation induces elevation of [Ca2+]i through the activation of IP3 in cultured hippocampal neurons. The effects of several oxidants on [Ca2+]i were explored. The results showed that application of 1 mM H2O2, 1 mM Ch-T, and 500 μM DTNB induced a sustained [Ca2+]i rise, and the elevation induced by H2O2 and Ch-T was much higher than DTNB. Previous studies demonstrated that Ch-T and H2O2 have been used to infer the effects of both methionine and cysteine oxidation in physiological systems (see review, Hoshi and Heinemann 2001; Squier and Bigelow 2000); DTNB is known as the cysteine-specific oxidant (Prasad and Goyal 2004; Jönsson et al. 2007). The present study indicates an central role of cysteine residue oxidation in response to DTNB, and dual role of cysteine and methionine residue oxidation in response to H2O2 and Ch-T, thus the amplitude of [Ca2+]i induced by DTNB is much lower than the other two oxidants.

Promoted by the presence of trace amounts of metal ions such as Cu2+, Fe2+, Co2+, and Mn2+, cysteine often leads to a variety of products including the sulfenic ion, disulfide, and sulfonic ion (Finkel 2000). Physiologically, the disulfide formation may be the most likely consequence of cysteine oxidation. The disulfides in oxidized cysteine can be reduced back to thiols by DTT in vitro. Methionine is oxidized to methionine sulfoxide (MetO, MeSOX, MetSO, or MsX) by the addition of an extra oxygen atom. Unlike the reduction of disulfides in oxidized cysteine, the reducing reaction of oxidized methionine by DTT in vitro needs the catalysis of the enzyme peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase (MsrA) (Moskovitz et al. 1996). In our experiment, pretreatment with 1 mM extracellular DTT for 10 min abolished the action of DTNB on [Ca2+]i, but only partially reversed the effect of H2O2 and Ch-T on [Ca2+]i, suggesting the involvement of methionine oxidation in the increase of [Ca2+]i in response to H2O2 and Ch-T. In addition, the elevation of [Ca2+]i induced by H2O2 and Ch-T after pretreatment with DTT was statistically higher than that induced by single administration of DTNB, implying that methionine oxidation may play an important pathological role in [Ca2+]i elevation induced by exogenous ROS.

A low resting [Ca2+]i can be maintained either by extrusion of Ca2+ across the plasma membrane or by re-uptake of Ca2+ into internal stores via Ca2+-ATPase located on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane. The sustained elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ in H2O2-exposed cells may be attributed to the inactivation of the Ca2+-ATPase on either ER membrane or plasma membrane (Pariente et al. 2001; Zaidi et al. 2003; Rosado and Sage 2000). Early studies hypothesized that the direct oxidation of sulfhydryl groups in Ca2+-ATPase underlies the inactivation. The Ca-ATPase on ER is reversibly regulated through oxidation of specific cysteine residues (Viner et al. 1997).

CaM is an oxidatively sensitive calcium regulatory protein that modulates the activity of calcium channels and pumps (Bigelow and Squier 2005). Recently, CaM was reported to lose the ability to activate the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase with the C-terminal methionine residues being oxidized (Lushington et al. 2005; Slaughter et al. 2007). Our results showed the critical role of methionine oxidation in H2O2 and Ch-T-induced [Ca2+]i rise. So the potential direct molecular targets for the oxidizing actions of H2O2 and Ch-T may be CaM and Ca2+-ATPase; and DTNB may act on Ca2+-ATPase directly to result in the increase of [Ca2+]i.

Previous study has shown that two major intracellular sources contribute to [Ca2+]i: an intracellular influx through plasma membrane channels, and an internal reservoir in the ER and mitochondria (Bootman et al. 2001). Our data showed that Ch-T still induce an increase in [Ca2+]i in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, but the elevation is lower than that in Ca2+-containing ACSF; however, the removal of Ca2+ had no effect on [Ca2+]i increase induced by H2O2 or DTNB, implying the involvement of extracellular Ca2+ in Ch-T-evoked [Ca2+]i rise. Both Ch-T and H2O2 have been used to induce methionine and cysteine oxidation; however, only Ch-T-induced [Ca2+]i rise was significantly inhibited in Ca2+-free ACSF. This may be due to the different target methionine residues of Ch-T and H2O2; Ch-T modifies exposed surface methionine residues whereas H2O2 attacks both exposed and buried methionine residues (Keck 1996; Feng and Hart 1995). CPA is an inhibitor of sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. In this study, by using CPA to deplete intracellular Ca2+ stores, the [Ca2+]i rise evoked by all the three oxidants was almost prevented, which implies that the Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores was primarily responsible for this [Ca2+]i elevation. Previous study has focused on the capacity of mitochondria to buffer synaptic calcium levels, besides their central role in cellular metabolism (see reviews, Cindy and Patrik 2006; Collins et al. 2000). In the present study, when hippocampal neurons were pretreated with CPA in Ca2+-free ACSF. However, it also did not abolish the oxidant-induced [Ca2+]i increase. These results suggest that oxidant-mediated [Ca2+]i increase also depends on mitochondria. Our current results are supported by the other studies devoted to elucidate the H2O2-induced [Ca2+]i mobilization (González et al. 2006; Pariente et al. 2001).

It has been well characterized that the binding of IP3, the product of a phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C, to its receptor (IP3R) on ER is the main pathway to initiate Ca2+ release from intracellular stores in many cell types. Ca2+ liberation from ER is triggered by the activation of IP3R and RyR (Rizzuto 2001; Finch et al. 1991; Berridge 1998). This process is promoted by cytosolic Ca2+, resulting in a regenerative process of Ca2+-induced release (CICR), which enables interaction between different Ca2+-dependent process (Finch et al. 1991; Friel and Tsien 1992; Fagni et al. 2000). In this study, to examine whether the release of Ca2+ from intracellular Ca2+ stores was mediated by IP3 receptors, hippocampal neurons were exposed to 2 mM caffeine or 100 μM ATP prior to oxidant. Caffeine can stimulate ryanodine receptors and inhibit both cAMP degradation and PLC activation, then prevent IP3-sensitive Ca2+ channel opening (Hong et al. 2006). ATP is an important neurotransmitter in both the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system (Ralevic and Burnstock 1998). These two substances share the ability to antagonize IP3-mediated Ca2+ release. Our results showed that they significantly attenuated the increase of [Ca2+]i evoked by oxidants, which suggests that cysteine and methionine residue oxidation-induced Ca2+ mobilization are mainly mediated by IP3-sensitive internal Ca2+ stores.

In summary, the present study demonstrated that cysteine and methionine residue oxidation plays an important pathological role in the regulation of [Ca2+]i elevation in response to ROS and oxidants through multiple pathways, especially the internal calcium stores. Recently, more attention has focused on the correlation between methionine oxidation and aging (Petropoulos and Friguet 2006; Stadtman 2006; Cabreiro et al. 2006). Our study will provide evidence to support to this hypothesis dealing with the role of methionine oxidation and Ca2+ dysregulation hypothesis.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the grants from the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars of China (No. 30425024) and the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program) (No. 2007CB507404) to Dr. Jian-Guo Chen, and Joint Research Fund for Overseas Chinese Young Scholars to Dr. Yong Xia and Dr. Jian-Guo Chen (No. 30728010).

References

- Berridge MJ (1998) Neuronal calcium signaling. Neuron 21:13–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow DJ, Squier TC (2005) Redox modulation of cellular signaling and metabolism through reversible oxidation of methionine sensors in calcium regulatory proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1703:121–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootman MD, Collins TJ, Peppiatt CM, Prothero LS, MacKenzie L, De Smet P, Travers M, Tovey SC, Seo JT, Berridge MJ, Ciccolini F, Lipp P (2001) Calcium signaling—an overview. Semin Cell Dev Biol 12:3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabreiro F, Picot CR, Friguet B, Petropoulos I (2006) Methionine sulfoxide reductases: relevance to aging and protection against oxidative stress. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1067:37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Avdonin V, Ciorba MA, Heinemann SH, Hoshi T (2000) Acceleration of P/Q-type inactivation in voltage-gated K+ channels by methionine oxidation. Biophys J 78:174–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Daggett H, Heinemann SH, Hoshi T (2002) Nitric oxide augments voltage-gated P/Q- type Ca2+ channels constituting a putative positive feedback loop. Free Radic Biol Med 32:638–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementi ME, Misiti F (2005) Substitution of methionine 35 inhibits apoptotic effects of Abeta (31–35) and Abeta (25–35) fragments of amyloid-beta protein in PC12 cells. Med Sci Monit 11:BR381–BR385 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementi ME, Pezzotti M, Orsini F, Sampaolese B, Mezzogori D, Grassi C, Giardina B, Misiti F (2006) Alzheimer’s amyloid beta-peptide (1–42) induces cell death in human neuroblastoma via bax/bcl-2 ratio increase: an intriguing role for methionine 35. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 342:206–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins TJ, Lipp P, Berridge MJ, Li W, Bootman MD (2000) Inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate-induced Ca2+ release is inhibited by mitochondrial depolarization. Biochem J 347:593–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch PJ, Barnham KJ, Duce JA, Blake RE, Masters CL, Trounce IA (2006) Copper-dependent inhibition of cytochrome oxidase by Abeta (1–42) requires reduced methionine at residue 35 of the Abeta peptide. J Neurochem 99:226–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai XL, Sun YX, Jiang AF (2007) Attenuated cytotoxicity but enhanced betafibril of a mutant amyloid beta-peptide with a methionine to cysteine substitution. FEBS Lett 581:1269–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis DA, Newcomb FM, Moskovitz J, Fales HM, Levine RL, Yarchoan R (2002) Inactivation of HIV-2 protease through methionine oxidation and its restoration by methionine sulfoxide reductase. Methods Enzymol 348:249–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagni L, Chavis P, Ango F, Bockaert J (2000) Complex interactions between mGluRs, intracellular Ca2+ stores and ion channels in neurons. Trends Neurosci 23:80–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng YH, Hart G (1995) In vitro oxidative damage to tissue-type plasminogen activator: a selective modification of the biological functions. Cardiovasc Res 30:255–261 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch E, Turner T, Goldin S (1991) Calcium as a coagonist of inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate-induced calcium release. Science 252:443–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel T (2000) Redox-dependent signal transduction. FEBS Lett 476:52–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster TC (1999) Involvement of hippocampal synaptic plasticity in age-related memory decline. Brain Res Rev 30:236–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster TC, Kumar A (2002) Calcium dysregulation in the aging brain. Neuroscientist 8:297–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friel DD, Tsien RW (1992) A caffeine- and ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ store in bullfrog sympathetic neurons modulates effects of Ca2+ entry on [Ca2+]i. J Physiol 450:217–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González A, Granados MP, Pariente JA, Salido GM (2006) H2O2 mobilizes Ca2+ from agonist- and thapsigargin-sensitive and insensitive intracellular stores and stimulates glutamate secretion in rat hippocampal astrocytes. Neurochem Res 31:741–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman D (1956) Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J Gerontol 11:298–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JH, Moon SJ, Byun HM, Kim MS, Jo H, Bae YS, Lee SI, Bootman MD, Roderick HL, Shin DM, Seo JT (2006) Critical role of PLCγ1 in the generation of H2O2- evoked [Ca2+]i oscillation in cultured rat cortical astrocytes. J Biol Chem 281:13057–13067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi T, Heinemann SH (2001) Regulation of cell function by methionine oxidation and reduction. J Physiol 531:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson TJ, Ellis HR, Poole LB (2007) Cysteine reactivity and thiol-disulfide interchange pathways in AhpF and AhpC of the bacterial alkyl hydroperoxide reductase system. Biochemistry 46:5709–5721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck RG (1996) The use of t-butyl hydroperoxide as a probe for methionine oxidation in proteins. Anal Biochem 236:56–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khachaturian ZS (1994) Calcium hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease and brain aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci 15:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koc A, Gladyshev VN (2007) Methionine sulfoxide reduction and the aging process. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1100:383–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lushington GH, Zaidi A, Michaelis ML (2005) Theoretically predicted structures of plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase and their susceptibilities to oxidation. J Mol Graph Model 24:175–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly CV, Verstreken P (2006) Mitochondria at the synapse. Neuroscientist 12:291–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP, Chan SL (2003) Neuronal and glial calcium signaling in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Calcium 34:385–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming YL, Zhang H, Long LH, Wang F, Chen JG, Zhen XC (2006) Modulation of Ca2+ signals by phosphatidylinositol-linked novel D1 dopamine receptor in hippocampal neurons. J Neurochem 98:1316–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskovitz J, Weissbach H, Brot N (1996) Cloning and expression of a mammalian gene involved in the reduction of methionine sulfoxide residues in proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:2095–2099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pariente JA, Camello C, Camello PJ, Salido GM (2001) Release of calcium from mitochondrial and nonmitochondrial intracellular stores in mouse pancreatic acinar cells by hydrogen peroxide. J Membr Biol 179:27–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petropoulos I, Friguet B (2006) Maintenance of proteins and aging: the role of oxidized protein repair. Free Radic Res 40:1269–1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad M, Goyal RK (2004) Currents in colonic smooth muscle by oxidants. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286:671–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralevic V, Burnstock G (1998) Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev 50:413–492 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto R (2001) Intracellular Ca2+ pools in neuronal signaling. Curr Opin Neurobiol 11:306–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robison AJ, Winder DG, Colbran RJ, Bartlett RK (2007) Oxidation of calmodulin alters activation and regulation of CaMKII. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 356:97–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosado JA, Sage SO (2000) Regulation of plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase by small GTPases and phosphoinositides in human platelets. J Biol Chem 275:19529–19535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter BD, Urbauer RJ, Urbauer JL, Johnson CK (2007) Mechanism of calmodulin recognition of the binding domain of isoform 1b of the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase: kinetic pathway and effects of methionine oxidation. Biochemistry 46:4045–4054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squier TC, Bigelow DJ (2000) Protein oxidation and age-dependent alterations in calcium homeostasis. Front Biosci 5:D504–D526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadtman ER (1993) Oxidation of free amino acids and amino acid residues in proteins by radiolysis and by metal-catalyzed reactions. Annu Rev Biochem 62:797–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadtman ER (2004) Role of oxidant species in aging. Curr Med Chem 11:1105–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadtman ER (2006) Protein oxidation and aging. Free Radic Res 40:1250–1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taggart C, Cervantes-Laurean D, Kim G, McElvaney NG, Wehr N, Moss J, Levine RL (2000) Oxidation of either methionine 351 or methionine 358 in alpha 1-antitrypsin causes loss of anti-neutrophil elastase activity. J Biol Chem 275:27258–27265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toescu EC, Verkhratsky A (2003) Neuronal ageing from an intraneuronal perspective: roles of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. Cell Calcium 34:311–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toescu EC, Verkhratsky A (2004) Ca2+ and mitochondria as substrates for deficits in synaptic plasticity in normal brain aging. J Cell Mol Med 8:181–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viner RI, Ferrington DA, Aced GI, Miller-Schlyer M, Bigelow DJ, Schöneich Ch (1997) In vivo aging of rat fast twitch skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca-ATPase Chemical analysis and quantitative simulation by exposure to low levels of peroxyl radicals. Biochim Biophys Acta 1329:321–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalley LJ, Deary IJ, Appleton CL, Starr JM (2004) Cognitive reserve and the neurobiology of cognitive aging. Ageing Res Rev 3:369–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Yin D, Jas GS, Kuczer K, Williams TD, Schoneich C, Squier TC (1996) Oxidative modification of a carboxyl-terminal vicinal methionine in calmodulin by hydrogen peroxide inhibits calmodulin-dependent activation of the plasma membrane Ca-ATPase. Biochemistry 35:2767–2787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yermolaieva O, Chen J, Couceyro PR, Hoshi T (2001) Cocaine-and amphetamine-regulated transcript peptide modulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ signaling in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci 21:7474–7480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi A, Barron L, Sharov VC, Schoneich C, Mochaelis EK, Michaelis ML (2003) Oxidative inactivation of purified plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase by hydrogen peroxide and protection by calmodulin. Biochemistry 42:12001–12010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]