Abstract

Clinical and laboratory investigations have demonstrated the involvement of viruses and bacteria as potential causative agents in cardiovascular disease and have specifically found coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) to be a leading cause. Experimental data indicate that cytokines are involved in controlling CVB3 replication. Therefore, recombinant CVB3 (CVB3rec) variants expressing the T-helper-1 (TH1)-specific gamma interferon (IFN-γ) or the TH2-specific interleukin-10 (IL-10) as well as the control virus CVB3(muIL-10), which produce only biologically inactive IL-10, were established. Coding regions of murine cytokines were cloned into the 5′ end of the CVB3 wild type (CVB3wt) open reading frame and were supplied with an artificial viral 3Cpro-specific Q-G cleavage site. Correct processing releases active cytokines, and the concentration of IFN-γ and IL-10 was analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and bioassays. In mice, CVB3wt was detectable in pancreas and heart tissue, causing massive destruction of the exocrine pancreas as well as myocardial inflammation and heart cell lysis. Most of the CVB3wt-infected mice revealed virus-associated symptoms, and some died within 28 days postinfection. In contrast, CVB3rec variants were present only in the pancreas of infected mice, causing local inflammation with subsequent healing. Four weeks after the first infection, surviving mice were challenged with the lethal CVB3H3 variant, causing casualties in the CVB3wt- and CVB3(muIL-10)-infected groups, whereas almost none of the CVB3(IFN-γ)- and CVB3(IL-10)-infected mice died and no pathological disorders were detectable. This study demonstrates that expression of immunoregulatory cytokines during CVB3 replication simultaneously protects mice against a lethal disease and prevents virus-caused tissue destruction.

Cardiovascular disease is one of the major causes of death in humans and has been linked to many different environmental risk factors. Among them, coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3)—a member of the picornavirus family—is one of the most important causes of virus-induced acute or chronic myocarditis in humans (37). The presence of CVB3 in heart tissue of patients with acute myocarditis or dilated cardiomyopathy has been demonstrated, e.g., by detection of virus genome (18) and virus protein (23). In order to study CVB3-caused infections in more detail, several murine models have been established (7, 26, 36). Some mechanisms have been proposed in an attempt to distinguish between pathogenesis caused by direct viral myocardial tissue destruction (25) or by virus-induced immune responses directed at infected cardiomyocytes (6, 7) or at surface epitopes shared between viral and cellular proteins (5). These investigations demonstrated that the pathology of CVB3-induced acute or chronic disease depends not only on the virus infection but also on several immune parameters, like the balance of T-cell activation (15, 21) or cytokine activity (16). Among them, CD4+ T-helper (TH) lymphocytes seem to be involved in the outcome of CVB3-induced myocarditis (22). These cells differentiate into two subsets capable of secreting distinct patterns of cytokines upon antigen stimulation. TH-1 (TH1) cells secrete gamma interferon (IFN-γ), interleukin-2 (IL-2), and tumor necrosis factor alpha, whereas TH2 cells predominantly produce IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13 (32). In general, these T-cell subsets are reciprocally regulated by IL-4, IL-10, and IFN-γ. The local expression of cytokines plays a crucial role in the murine immune response against CVB3. CVB3-infected cells expressing not only viral proteins but also murine cytokines should influence the normal pattern of virus-specific immune responses. Therefore, experimental modulation of local immunity could help to elucidate the role of cytokines in the onset of acute and chronic stages of murine myocarditis. In order to characterize the influence of either TH1- or TH2-directed T-cell activation on the outcome of CVB3-caused disease, two different recombinant CVB3 (CVB3rec) variants were established expressing the immunomodulatory cytokines IFN-γ [by CVB3(IFN-γ)] and IL-10 [by CVB3(IL-10)] using the cloning procedure first described by Andino et al. (1). Subsequent in vitro mutagenesis of CVB3(IL-10) led to the control virus CVB3(muIL-10) releasing biologically inactive IL-10. After cytokine expression was confirmed in vitro, BALB/c mice were infected with CVB3wt and CVB3rec variants. Virus-caused cytokine expression was detectable in tissue samples. At several days postinfection (p.i.), tissue samples were obtained and analyzed for the amount of infectious virus, inflammation, and cell destruction. In mice, CVB3rec variants were not able to infect the heart and revealed therefore an attenuated phenotype. In contrast, as expected, CVB3wt was detectable in pancreas and heart tissue of BALB/c mice, causing massive destruction of the exocrine pancreas and inflammation as well as maximal myocardial inflammation and heart cell destruction. All inoculated CVB3 variants induced virus-specific antibody responses. Furthermore, 28 days after the initial infection challenge experiments with the lethal variant, CVB3H3 revealed almost complete protection against CVB3 infections, when we used BALB/c as well as C57BL/6 mice, which was dependent on the virus-caused production of functional cytokines by CVB3rec variants but was independent of whether TH1- or TH2-specific cytokines were expressed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Male inbred BALB/c (H-2dd) and C57BL/6 (H-2bb) mice (7 to 9 weeks of age) were used in this study. Experimental groups consisted of a minimum of three or four mice, and experiments were repeated usually three or four times. Animal experiments complied with all federal requirements and guidelines and institutional policies.

Viruses and cell lines.

The CVB3 used was cDNA-generated viruses obtained after transfection of African green monkey kidney (GMK) cells with the plasmid pCVB3M2 (24) or pBK-CMV/CVB3H3 (20). Viruses were propagated in GMK cells and quantified by standard plaque formation assay on GMK cell monolayers as described previously (7).

Infection protocol.

Mice were inoculated by intraperitoneal injection of 0.2 ml of saline containing the stated amount of virus and were monitored daily for morbidity and mortality up to 4 weeks p.i.

Challenge experiments.

Four weeks after the initial infection with CVB3wt or CVB3rec variants, all surviving mice were challenged with five 50% lethal doses (LD50s) of the lethal CVB3H3 variant by intraperitoneal infection. Age-matched control mice which were not infected during the first set of experiments were used to verify the outcome of the lethal challenge. Mice were monitored daily for morbidity and mortality up to 4 weeks p.i. The statistical comparisons were carried out with Microsoft Excel by using Student's t test.

Construction of chimeric CVB3.

The murine genes encoding IL-10 and IFN-γ were cloned into the SacI restriction site at nucleotide position 747 of the coxsackieviral genome. The insertion site corresponds to codon 2 of the capsid protein VP4. It was aimed to clone the cytokine genes without the N-terminal signal peptides to avoid trafficking of the nascent polyprotein into the endoplasmic reticulum. At the C-terminal junction to the CVB3 polyprotein, an additional 12 nucleotides encoding a QG consensus sequence preceded by the tripeptide ALF was introduced to accomplish proper polyprotein processing by the viral 3C-proteinase. Prior to cloning, the cytokine sequences were obtained from the heart tissue of CVB3-infected mice by reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) and by using the primer pairs IL-10-5′ (5′-AAAATGGGAGCTCAA-AGCAGGGGCCAGTACAGCCGG-3′) and IL-10-3′ (5′-TGATACTTGAGCTCCTTGAAACAAAGCGCTTTTTACTTTGATCAT-3′) for amplification of IL-10 and IFN-γ-5′ (5′-AAAATGGGAGCTCAATCTGGCTGTTACTGCCACGGC-3′) and IFN-γ-3′ (5′-TGATACTTGAGCTCCTTGAAACAAAGCGCAGCGACTCCTTTTCCG-3′) for amplification of IFN-γ. PCR fragments were digested with SacI and cloned into the infectious cDNA pCVB3M2 (24) to give the plasmids pCVB3M2(IL-10) and pCVB3M2(IFN-γ). Viable cDNA-generated viruses CVB3(IL-10) and CVB3(IFN-γ) were obtained after transfection of GMK cells with plasmid DNA. The correct insertion of the inserted genes was verified by sequencing of viral RNA. In order to analyze the in vivo effects caused by the real cytokine activity, a suitable control virus was necessary. To generate such a control virus, the IL-10 gene was modified by subsequent in vitro mutagenesis leading to CVB3(muIL-10). For that purpose, a small peptide (PAAAPG) was inserted between amino acids 111 and 112 of the IL-10 sequence, causing a significant change of the secondary protein structure by interfering with the correct alignment of the disulfide bridges between the highly conserved cysteines at positions 62, 108, and 120.

One-step growth curve experiments.

GMK cell monolayers were infected with one multiplicity of infection. After 45 min at 37°C, supernatants were removed and cell monolayers were washed twice. Thereafter, 2-ml cell culture media were added, and all monolayers were incubated at 37°C. At different times p.i., supernatants as well as remaining cells were isolated and frozen at −20°C. Cells were disrupted by three cycles of freezing and thawing. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and samples were stored at −70°C. The amount of infectious virus was determined in triplicates by standard plaque assay. The obtained growth curve for each virus variant was calculated from three different experiments and is demonstrated as mean ± standard deviation.

Quantification of cytokines.

The amount of IFN-γ in culture supernatants and in murine sera was determined using a commercial available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (R&D Systems, Inc.). The concentration of IL-10 was measured using a bioassay based on the IL-10-dependent growth of the murine mast cell line D36 (31) and was described in detail by Schlaak et al. (30). Recombinant IL-10 (PeproTech Inc.) was used to standardize the assay.

Virus titer in organs.

At different days p.i., organs were aseptically obtained, washed with sterile saline, and homogenized with cell culture medium (Dulbecco modified Eagle medium) containing 50 U of penicillin and 50 mM streptomycin per ml. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and supernatants were subjected to sequential 10-fold dilutions in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium. The virus titer was determined by 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) assays. The statistical comparisons were carried out with Microsoft Excel by using Student's t test.

Determination of serum α-HBDH activity.

In sera, the concentration of the cardiomyocyte-specific enzyme α-hydroxybutyrate-dehydrogenase (α-HBDH) was analyzed using a commercially available kit (Sigma Diagnostics) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Briefly, murine sera were diluted 1:4 with saline and maintained at 25°C together with the kit reagent. Part of each sample (0.02 ml) was incubated for 30 s with 0.5 ml of the prewarmed kit reagent. Then the absorbance was determined at 340 nm. Exactly 1, 2, and 3 min after the initial reading, the absorbance was measured again and the mean value change per minute was determined. Thereafter, α-HBDH activity was compared to whole lactate dehydrogenase activity (Sigma Diagnostics), demonstrating that the quotient of LDH/α-HBDH was always below 1.3, which indicates cardiomyocyte destruction.

Preparation and staining of routine histology.

Aseptically removed pancreas and heart tissue was fixed with 4% formalin and mounted in paraffin, and 6-μm sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or with Sirius red.

RT-PCR.

RNA was isolated from the pancreas tissue of infected and noninfected BALB/c mice according to the acid guanidinium thiocyanate phenol chloroform method (3), which is described in detail in reference 8. The detection of viral genomes was performed by RT-PCR using a primer pair which corresponds to the positions 471 to 494 and 848 to 872 of the original cDNA, giving the following PCR products: CVB3wt, 340 bp; CVB3(IFN-γ), 740 bp; CVB3(IL-10), 820 bp; and CVB3(muIL-10), 838 bp.

Immunohistochemistry with paraffin sections.

The detection of CVB3 antigens in murine tissue samples was carried out as described previously (7).

Immunohistochemistry with frozen sections.

Immunohistochemical studies were carried out with cryomicrotome sections from pancreas and heart tissue as described previously (8). Primary antibody was applied for 14 h at 4°C. These consisted of rat anti-mouse IL-10 anti-bodies (clone JES5-16E3; PharMingen) and rat anti-mouse IFN-γ antibodies (clone XMG1.2; PharMingen). Thereafter, secondary biotin-conjugated goat anti-rat antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were used.

Quantification of CVB3-specific antibodies.

The concentration of virus-binding antibodies in the sera of CVB3-infected mice was determined by using 96-well flat-bottomed microtiter plates coated with a rabbit anti-CVB3 serum (protein concentration, 1 μg/ml). After removal of the excess, wells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with a blocking buffer (PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin) for 30 min at 37°C. Plates were then automatically washed six times with PBS and 0.05% Tween 20. Purified CVB3 preparations were then bound to the coated plates and incubated overnight at 4°C. Thereafter, plates were washed three times with PBS and 0.05% Tween 20, followed by experimental mouse sera. After additional washing, peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G was added and samples were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. After several washing procedures, o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (OPD-peroxidase substrate tablet set; Sigma Diagnostics) was applied to determine relative amounts of CVB3-binding immunoglobulin G measured by absorbance at 490 nm.

In situ hybridization.

The detection of viral RNA in tissue samples of infected mice was carried out as described previously (8).

RESULTS

Construction and characterization of CVB3rec variants.

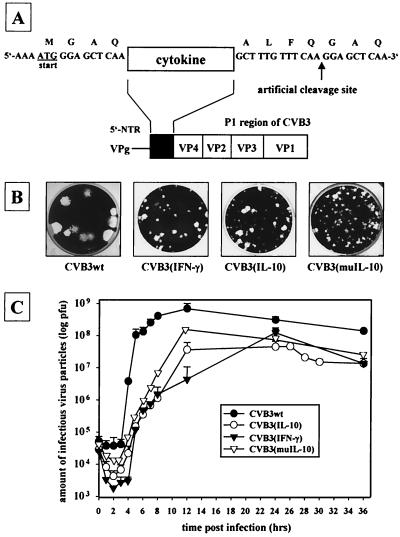

In order to establish cytokine-expressing CVB3 variants, the coding sequence of murine IFN-γ or IL-10 was amplified by PCR using cytokine-specific primer pairs supplied with an artificial viral 3Cpro-specific Q-G protease cleavage site and was inserted into the full-length cDNA of CVB3 (pCVB3M2) as demonstrated in Fig. 1A. Due to the insertion of the cytokine sequence, plaque assays and one-step growth curves indicated reduced growth capacity of the CVB3rec variants CVB3(IFN-γ) and CVB3(IL-10) when compared to the wild-type virus CVB3wt as demonstrated in Fig. 1B and C. To distinguish between effects caused by this reduced replication efficiency and the real cytokine activity under in vivo conditions, a suitable control virus was necessary. In order to generate such a control virus, the IL-10 gene was modified by subsequent in vitro mutagenesis leading to CVB3(muIL-10). For that purpose, a small peptide was inserted between amino acids 111 and 112 of the original IL-10 sequence, causing a significant change of the secondary protein structure. In view of viral replication in vitro, there was no difference between CVB3(IL-10) and CVB3(muIL-10) detectable (Fig. 1B and C). The stability of the obtained CVB3rec variants was tested by RT-PCR, demonstrating that after seven passages the original virus was still intact (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Sequences encoding murine IFN-γ or IL-10 were cloned at the start of the translation together with an artificial cleavage site for 3Cpro (A). The insertion of additional nucleotide sequences caused reduced growth capacities of the CVB3rec variants, which were analyzed by standard plaque formation assays on GMK cell monolayers (B) and by one-step growth curve experiments (C).

Quantification of cytokine production by CVB3rec variants.

As demonstrated in Table 1, correct processing of the CVB3 polyprotein released IL-10 and IFN-γ. The concentration of IL-10 in supernatants of virus-infected GMK cells was determined with a bioassay based on the IL-10 susceptibility of D36 cells. Using recombinant IL-10 as a standard, the mean value of IL-10 in the supernatant of CVB3(IL-10)-infected GMK cells was calculated as 11.65 ± 4.24 U/ml, whereas in supernatants of GMK cells infected with CVB3wt, CVB3(IFN-γ), or CVB3(muIL-10), no IL-10 activity was detectable. This bioassay clearly demonstrated that IL-10 produced by CVB3(muIL-10) was biologically inactive. The concentration of IFN-γ in supernatants of CVB3(IFN-γ)-infected GMK cells was determined by an ELISA indicating that the mean value of IFN-γ was 507 ± 38 U/ml, whereas in supernatants of CVB3wt-, CVB3(IL-10)-, or CVB3(muIL-10)-infected GMK cells, no IFN-γ was detectable. All samples contained the same virus amount of 107 PFU/ml. Furthermore, increased levels of IFN-γ in serum were also detectable in CVB3(IFN-γ)-infected BALB/c mice 1 day p.i. (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Characterization of cytokine expression

| Virus variant | Amt of IL-10 released (U/ml)a | Amt of IFN-γ released (U/ml)b |

|---|---|---|

| CVB3wt | NDc | ND |

| CVB3(IFN-γ) | ND | 507 ± 38 |

| CVB3(IL-10) | 11.65 ± 4.24 | ND |

| CVB3(muIL-10) | ND | ND |

The concentration of IL-10 was determined in cell culture supernatants from virus-infected GMK cells using a bioassay. The data represent the mean ± standard deviation of three experiments.

The concentration of IFN-γ was determined in cell culture supernatants from virus-infected GMK cells using an ELISA. The data represent the mean ± standard deviation of three experiments.

ND, not detectable.

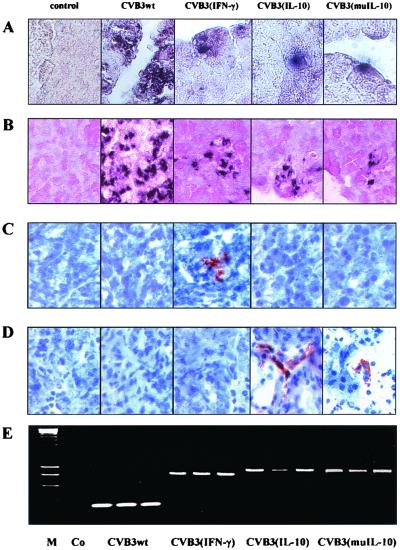

Detection of CVB3 variants in murine pancreas tissue.

After cytokine expression was confirmed in vitro, male BALB/c mice were infected with 106 PFU of CVB3wt, CVB3(IFN-γ), CVB3(IL-10), or CVB3(muIL-10) or remained noninfected. One day p.i., pancreas tissue was obtained and analyzed for the presence of viral protein (Fig. 2A) or viral RNA (Fig. 2B). Infection with CVB3wt caused a widespread viral replication in the exocrine pancreatic tissue, whereas the replication of the recombinant viruses was limited to small areas. The presence of virus-produced cytokines was characterized by immuno-histochemistry. Expression of IFN-γ (Fig. 2C) or IL-10 (Fig. 2D) was detectable only in murine tissue which was infected either with CVB3(IFN-γ) or CVB3(IL-10). The mutated IL-10 expressed by CVB3(muIL-10) was also recognized by the IL-10-specific primary antibody but with decreased sensitivity, indicating that structural changes in the protein sequence of muIL-10 may also interfere with antibody binding sites. As demonstrated in Fig. 2E, the insertion into the genome of the CVB3rec variants remained genetically stable also under in vivo conditions, as shown by RT-PCR from pancreas tissue 3 days p.i.

FIG. 2.

One day p.i., the expression of virus-produced cytokines was determined by immunohistochemistry. By using pancreas paraffin sections of BALB/c mice, the presence of viral protein (A), viral genomes (B), virus-produced IFN-γ (C), and virus-produced IL-10 (D) was analyzed and compared to that of noninfected controls (magnification, ×440). (E) Three days p.i., the CVB3rec variants remained genetically stable under in vivo conditions as shown in pancreas tissue samples by use of RT-PCR. The detection of viral genomes was performed using a primer pair which corresponds to positions 471 to 494 and 848 to 872 of the original cDNA, resulting in the following PCR products: CVB3wt, 340 bp; CVB3(IFN-γ), 740 bp; CVB3(IL-10), 820 bp; and CVB3(muIL-10), 838 bp.

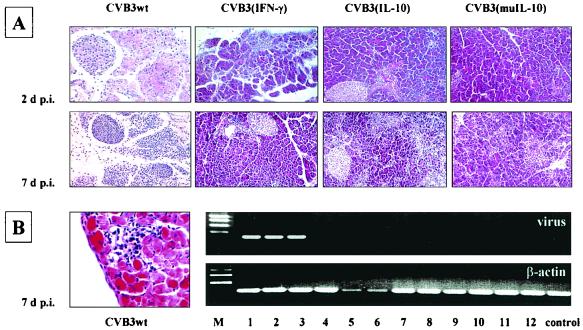

Comparison of virus-induced pathogenesis in pancreas and heart tissue.

CVB3wt was detectable in pancreas and heart tissue of BALB/c mice, causing massive destruction of the exocrine pancreas and inflammation 1 to 2 days p.i. (Fig. 3A) as well as maximal myocardial inflammation 7 days p.i. (Fig. 3B), which was accompanied by significantly increased levels of α-HBDH activity in serum 4 and 7 days p.i. (Table 2) (for CVB3wt versus CVB3rec variants, P < 0.01), indicating cardiomyocyte destruction. In contrast, low titers of CVB3rec variants were present only in the pancreas tissue of infected mice (Table 2), causing inflammation with subsequent healing, but the occurrence of infiltrating immune cells was dependent on the virus variant used (Fig. 3A). In CVB3(IFN-γ)-infected mice, early inflammation started 1 to 2 days p.i. and declined up to 7 days p.i., whereas in CVB3(IL-10)-infected mice, the presence of inflamed areas in pancreas tissue was delayed, reaching maximal expansion up to 7 days p.i. In CVB3(muIL-10)-infected mice, no intense inflammation was present in pancreas tissue up to 7 days p.i. All replicating virus was removed from pancreatic tissue 7 days p.i. (Table 2). Furthermore, CVB3rec variants were not able to reach the heart, and no cardiomyocyte destruction was detectable, which was confirmed by normal serum α-HBDH levels in these mice (Table 2). Myocardial tissue of these infected mice was normal, like tissue of control mice (data not shown), and no viral RNA was detectable in heart tissue samples when RT-PCR was used (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

(A) Paraffin sections of pancreas tissue obtained from BALB/c mice were stained with hematoxylin and eosin 2 and 7 days following infection with CVB3wt or CVB3rec variants (magnification, ×200). (B) RT-PCR was performed. Replication of CVB3wt in heart tissue (lanes 1 to 3, virus) was accompanied by myocardial inflammation (magnification, ×200), whereas no viral genome was detectable in the heart tissue of CVB3rec-infected mice. Additional lanes: M, DNA molecular weight markers; 4 to 6 CVB3(IFN-γ); 7 to 9, CVB3(IL-10); 10 to 12, CVB3(muIL-10).

TABLE 2.

Virus replication and tissue damage in CVB3-infected BALB/c mice

| Day p.i. | Virus variant | Virus loada

|

α-HBDH activityb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreas | Heart | |||

| 1 | CVB3wt | 8.21 ± 4.50 | 3.89 ± 2.50 | 1.10 ± 0.10 |

| CVB3(IFN-γ) | 4.74 ± 2.50 | NDc | 0.98 ± 0.15 | |

| CVB3(IL-10) | 3.86 ± 2.22 | ND | 0.99 ± 0.11 | |

| CVB3(muIL-10) | 4.25 ± 3.10 | ND | 1.01 ± 0.12 | |

| 2 | CVB3wt | 7.08 ± 3.89 | 4.25 ± 2.89 | 1.46 ± 0.25 |

| CVB3(IFN-γ) | 4.25 ± 3.00 | ND | 0.92 ± 0.05 | |

| CVB3(IL-10) | 4.15 ± 2.77 | ND | 1.05 ± 0.12 | |

| CVB3(muIL-10) | 4.00 ± 2.33 | ND | 0.99 ± 0.12 | |

| 4 | CVB3wt | 6.42 ± 4.00 | 4.50 ± 3.56 | 1.68 ± 0.22 |

| CVB3(IFN-γ) | 3.35 ± 2.15 | ND | 1.02 ± 0.08 | |

| CVB3(IL-10) | 4.95 ± 3.25 | ND | 0.97 ± 0.10 | |

| CVB3(muIL-10) | 3.85 ± 3.00 | ND | 1.02 ± 0.12 | |

| 7 | CVB3wt | ND | 5.75 ± 4.56 | 2.25 ± 0.23 |

| CVB3(IFN-γ) | ND | ND | 0.93 ± 0.12 | |

| CVB3(IL-10) | ND | ND | 1.03 ± 0.09 | |

| CVB3(muIL-10) | ND | ND | 1.00 ± 0.11 | |

| 14 | CVB3wt | ND | 2.88 ± 1.67 | 1.10 ± 0.22 |

| CVB3(IFN-γ) | ND | ND | 0.99 ± 0.12 | |

| CVB3(IL-10) | ND | ND | 0.98 ± 0.10 | |

| CVB3(muIL-10) | ND | ND | 0.97 ± 0.05 | |

The amount of replicating virus is presented as log TCID50 titer/100 mg of tissue. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation of three experiments.

α-HBDH activity in murine sera is presented as relative amount in comparison to the α-HBDH activity in sera of mice of the noninfected group. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation of three experiments.

ND, not detectable.

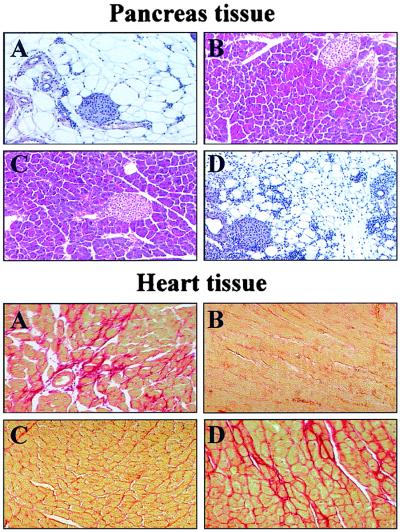

Expression of immunoregulatory cytokines by CVB3rec variants confers protection against a lethal CVB3 challenge.

As demonstrated in Table 3, 80.8% (38 of 47) of CVB3wt-infected BALB/c mice survived, but only 23.7% (9 of 38) of these mice remained without obvious symptoms like loss of weight, decreased reactivity, and bristled-up fur 28 days p.i. In contrast, all BALB/c mice infected either with CVB3(IFN-γ) or CVB3(IL-10) revealed no sign of ongoing disease, and no casualties occurred. In the CVB3(muIL-10)-infected group also, no casualties were present and 90% (27 of 30) of these mice remained without obvious symptoms. In order to investigate if the results from these experiments were dependent on the genetic background of the murine host, the C57BL/6 mouse strain was used. Basically the same results were obtained (Table 3). Of the CVB3wt-infected C57BL/6 mice, 100% (10 of 10) survived, but only 50% (5 of 10) remained without obvious symptoms 28 days p.i. In contrast, C57BL/6 mice infected either with CVB3(IFN-γ) or CVB3(IL-10) were healthy without any sign of ongoing disease and no casualties occurred. In the CVB3(muIL-10)-infected group also, no casualties were present and 90.9% (10 of 11) remained healthy. These data demonstrate that during the first infection no obvious differences between the cytokine-expressing variants CVB3(IFN-γ) and CVB3(IL-10) and the control virus CVB3(muIL-10) were detectable. In addition, the characterization of the amount of CVB3-specific antibodies in the sera of all infected mice revealed no differences (Table 3). In order to analyze the possibility that the virus-produced cytokines IFN-γ and IL-10 induced a strong memory immune response in mice, all surviving animals were challenged with five LD50s of the lethal CVB3H3 variant 4 weeks after the first infection (Table 4). All BALB/c control mice, which received no virus inoculation during the first infection, died within 7 days p.i. In addition, more casualties in the group originally infected with CVB3wt occurred and all mice revealed obvious symptoms linked to the viral infection. But only one mouse of 31 died in the CVB3(IFN-γ) group, and no death occurred in the CVB3(IL-10) group. All of these surviving mice appeared healthy. In contrast, only 46.7% (14 of 30) of the mice originally infected with the control virus CVB3(muIL-10) survived this lethal challenge and most of these mice demonstrated symptoms. Statistical analyses of the number of surviving animals during these challenge experiments showed significant differences between mice originally infected with CVB3wt and mice that received CVB3(IFN-γ) or CVB3(IL-10), as well as between mice originally infected with CVB3(muIL-10) and mice that received CVB3(IFN-γ) or CVB3(IL-10) (for all comparisons, P < 1 × 10−8), but no significant difference was detectable between mice originally infected with CVB3wt and with CVB3(muIL-10) (P = 0.06). When another mouse strain, like C57BL/6, was used, basically the same results were obtained during the challenge experiments (Table 4). All C57BL/6 control mice, which received no virus inoculation during the first infection, died within 7 days p.i. Furthermore, 50% (5 of 10) of mice originally infected with CVB3wt died and all surviving mice revealed obvious symptoms linked to the viral infection. In contrast, no death was present in the CVB3(IFN-γ) and CVB3(IL-10) group and all of these mice appeared without any symptoms. But only 54.5% (6 of 11) of the mice originally infected with the control virus CVB3(muIL-10) survived this lethal challenge, and most of these mice were sick. Statistical analyses of the amount of surviving animals during these challenge experiments showed significant differences between mice originally infected with CVB3wt and those that received CVB3(IFN-γ) or CVB3(IL-10), as well as between mice originally infected with CVB3(muIL-10) and those that received CVB3(IFN-γ) or CVB3(IL-10) (for all comparisons, P < 0.0065), but no significant difference was detectable between mice originally infected with CVB3wt and with CVB3(muIL-10) (P = 0.64). The data obtained from all challenge experiments indicate that in both mouse strains, the protection seen in the CVB3(IFN-γ)- and CVB3(IL-10)-infected group was based on the expression of cytokines from these CVB3rec variants most likely linked with an extensive activation of the immune response against CVB3 in general. In addition, the tissue of BALB/c mice originally infected with CVB3wt or CVB3(muIL-10) that survived the lethal CVB3H3 challenge revealed massive destruction of the exocrine pancreas as well as fibrosis in heart tissue 28 days p.i., as shown in Fig. 4A and D, whereas no pathological disorders were detectable in mice originally infected with CVB3(IFN-γ) or CVB3(IL-10) 28 days postchallenge (Fig. 4B and C). These results indicate that simultaneous expression of immunoregulatory cytokines during CVB3 replication can prevent virus-based tissue destruction caused by a normally lethal virus infection. The prevention of CVB3H3-induced lethal disease observed in mice originally infected with CVB3(IFN-γ) or CVB3(IL-10) was based on a dramatic inhibition of viral replication in the pancreas tissue and the lack of virus replication in the heart tissue during the early stage of the lethal challenge, as demonstrated in Fig. 5. BALB/c mice that remained noninfected during the first inoculation revealed high viral titers in pancreas and heart tissue 3 days after the lethal challenge with 5 LD50s of CVB3H3. In the pancreas tissue of these mice, the amount of infectious CVB3H3 was significantly increased in comparison with the viral load in mice that received a first inoculation 28 days earlier (P < 0.028). A significant reduction of viral replication was observed in the pancreas tissue of mice that received either CVB3(IFN-γ) or CVB3(IL-10) during the first inoculation, compared to mice of all other groups (P < 0.03). No statistical significance was detectable between the CVB3(IFN-γ) and the CVB3(IL-10) groups as well as between the CVB3wt and CVB3(muIL-10) groups. In heart tissue, the challenge virus was detectable only in mice which received CVB3wt or CVB3(muIL-10) during the first inoculation or remained noninfected. The viral load in heart tissue of these mice was not significantly different. In the heart tissue of mice which were inoculated with CVB3(IFN-γ) or CVB3(IL-10) during the first infection, the challenge virus was not detectable by TCID50 assays or RT-PCR and remained negative up to 4 weeks postchallenge (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Number and percentage of surviving and healthy mice 28 days after the first infection

| Mouse strain | Virus variant | No. of mice before infection | No. (%) of surviving mice | No. (%) of mice without symptomsa | Amt of CVB3-specific antibodies (OD490)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BALB/c | CVB3wt | 47 | 38 (80.8) | 9 (23.7) | 1.01 ± 0.10 |

| CVB3(IFN-γ) | 31 | 31 (100) | 31 (100) | 1.05 ± 0.06 | |

| CVB3(IL-10) | 40 | 40 (100) | 40 (100) | 0.93 ± 0.03 | |

| CVB3(muIL-10) | 30 | 30 (100) | 27 (90) | 0.98 ± 0.12 | |

| C57BL/6 | CVB3wt | 10 | 10 (100) | 5 (50) | 1.12 ± 0.06 |

| CVB3(IFN-γ) | 10 | 10 (100) | 10 (100) | 1.17 ± 0.07 | |

| CVB3(IL-10) | 8 | 8 (100) | 8 (100) | 1.06 ± 0.19 | |

| CVB3(muIL-10) | 11 | 11 (100) | 10 (90.9) | 0.99 ± 0.11 |

Obvious symptoms linked to CVB3 infection are loss of weight, decreased reactivity, and bristled-up fur.

Amount of CVB3-specific antibodies detected by ELISA (serum dilution, 1:100) and demonstrated as the optical density at 490 nm (OD490). Data represent the mean ± standard deviation of three experiments. Background levels in sera of mice prior virus inoculation were at 0.22 ± 0.12.

TABLE 4.

Number and percentage of surviving and healthy mice 28 days after the lethal challenge

| Mouse strain | Virus variant | No. of mice before infectiona | No. (%) of surviving mice | No. (%) of mice without symptomsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BALB/c | Control | 15 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| CVB3wt | 38 | 23 (60.5) | 0 (0) | |

| CVB3(IFN-γ) | 31 | 30 (96.8) | 30 (100) | |

| CVB3(IL-10) | 40 | 40 (100) | 40 (100) | |

| CVB3(muIL-10) | 30 | 14 (46.7) | 2 (14.3) | |

| C57BL/6 | Control | 10 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| CVB3wt | 10 | 5 (50) | 0 (0) | |

| CVB3(IFN-γ) | 10 | 10 (100) | 10 (100) | |

| CVB3(IL-10) | 8 | 8 (100) | 8 (100) | |

| CVB3(muIL-10) | 11 | 6 (54.5) | 2 (33.3) |

After the first infection (Table 3), all surviving mice were challenged with five LD50s of CVB3H3.

Obvious symptoms linked to CVB3 infection are loss of weight, decreased reactivity, and bristled-up fur.

FIG. 4.

Paraffin sections of pancreas tissue (stained with hematoxylin and eosin) as well as of heart tissue (stained with Sirius red; connective tissue is stained red) of BALB/c mice that were originally infected with CVB3wt (A) or CVB3(muIL-10) (D) but survived the lethal CVB3H3 challenge revealed massive destruction of the exocrine pancreas, as well as fibrosis in heart tissue 28 days postchallenge, whereas no pathological disorders were detectable in mice originally infected with CVB3(IFN-γ) (B) or CVB3(IL-10) (C). Magnification, ×220.

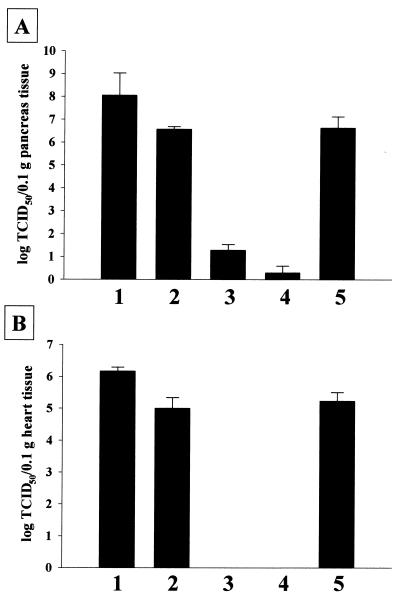

FIG. 5.

Amount of infectious virus particles in pancreas (A) and heart tissue (B) of BALB/c mice 3 days after a lethal challenge with five LD50s of CVB3H3 characterized by TCID50 assays. Four weeks prior to challenge, mice were inoculated either with CVB3wt (column 2), CVB3(IFN-γ) (column 3), CVB3(IL-10) (column 4), or CVB3(muIL-10) (column 5) or remained noninfected (1). Experimental groups consisted of five mice, and experiments were repeated three times. The mean ± standard deviation is shown.

DISCUSSION

After experimental CVB3 infection of mice, replicating viruses can be detected during the acute stage of infection in several organs but especially in heart and pancreas tissue. Even though CVB3 is typically a cytolytic virus, persistence of viral genomes in the murine heart can lead to chronic stages of myocarditis characterized by infiltration of lymphocytes, cardiomyocyte destruction, fibrosis, and calcification. Both virus-caused tissue damage and immune activation are involved in CVB3-caused pathology. The simultaneous expression of immunoregulatory proteins from within the viral genome and starting immediately with the viral replication should activate immune responses much faster than during a normal course of infection. Two sites have been used successfully to insert larger foreign nucleotide sequences into picornaviral genomes: the start of the translation (1) and the junction of the viral capsid protein 1D and the viral protease 2Apro (35). Until today, three studies have described coxsackieviral vectors to express foreign sequences (2, 11, 29). For example, it has recently been demonstrated that a CVB3 vector can produce an intact, biologically active interleukin (IL-4) under in vitro and in vivo conditions (2).

The purpose of the experiments described in this publication was to elucidate the effect of a TH1- or TH2-specific cytokine expression by CVB3rec variants on the outcome of the CVB3-induced pathogenesis and on the induction of a protective status in mice to prevent a lethal disease. In order to generate such recombinant viruses, the murine sequences encoding IFN-γ or IL-10 were cloned into the CVB3 genome. Subsequent in vitro mutagenesis of the IL-10 sequence led to the control virus CVB3(muIL-10) producing no biologically active IL-10. The CVB3 protease 3Cpro cleaved the cytokines from the nascent CVB3 polyprotein efficiently, as demonstrated by ELISA and bioassays (Table 1). In general, CVB3 replicated primarily in tissue of the exocrine pancreas upon i.p. inoculation (8). The CVB3rec variants revealed an attenuated phenotype in mice, because only a limited virus replication was detectable in pancreas tissue with subsequent healing and an infection of the heart was not observed. With regard to the virus load and the virus-caused pathogenesis in the pancreas tissue of BALB/c mice, only minor differences between CVB3(IFN-γ)-, CVB3(IL-10)-, and CVB3(muIL-10)-infected mice occurred, indicating that due to the insertion of additional nucleotide sequences into the viral genome, the replication efficiency of the CVB3rec variants was decreased. However, in comparison with CVB3(IFN-γ) and CVB3(muIL-10), the time course of the CVB3(IL-10) replication was slightly delayed during the first 2 days p.i., reaching a maximum of 4 days p.i., whereas CVB3(IFN-γ) replication declined faster than CVB3(IL-10) and CVB3(muIL-10) replication up to 4 days p.i. (Table 2). These findings were accompanied with the observation that inflammation in the pancreas tissue of CVB3(IFN-γ)-infected mice was already maximal 2 days p.i., indicating that early virus-produced IFN-γ most likely induced an activation of resident macrophages to defend pancreatic cells from the invading virus (13). The inflammatory infiltration of immune cells in the pancreatic tissue of CVB3(IL-10)-infected mice was delayed up to 7 days p.i., indicating that IL-10 produced by CVB3(IL-10) could be responsible for this result. Furthermore, no strong infiltration was observed in the pancreas tissue of CVB3(muIL-10)-infected mice (Fig. 3A). In contrast to the results obtained from CVB3rec-infected mice, CVB3wt caused an ongoing disease in BALB/c mice, accompanied by tremendous viral replication and massive destruction of the exocrine pancreas as well as myocardial inflammation and cardiomyocyte destruction (Fig. 3 and Table 2). In sera of all mice which survived the infection, high anti-CVB3 antibody titers were detectable.

Four weeks after the first infection, surviving mice were challenged with five LD50s of the lethal CVB3H3 variant, causing more casualties in the CVB3wt group, whereas almost all mice of the CVB3(IFN-γ)- and CVB3(IL-10)-infected groups remained healthy. The significance of this result was confirmed by the nonprotective effect of CVB3(muIL-10) and the independence from the genetic background of the murine host used (Tables 4 and 5). Therefore, a strong cytokine-dependent immune response during the first infection could be responsible for the protection of almost all mice during the second infection with the lethal CVB3H3 strain. This protection was linked with a significant reduction of the viral load in the pancreas tissue and a prevention of CVB3H3 replication in the heart. Decreased viral replication was also one reason for the vaccine-induced protection against CVB3-caused myocarditis observed in DNA-vaccinated mice (9, 10). In contrast, the tissue of mice that received CVB3wt or CVB3(muIL-10) during the first infection remained susceptible to CVB3H3 (Fig. 4 and 5). How were these immunoregulatory cytokines IFN-γ and IL-10, produced by CVB3(IFN-γ) and CVB3(IL-10), able to prevent a lethal disease in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice even after complete viral clearance 4 weeks after the initial infection? The mechanisms by which both IFN-γ and IL-10 abate CVB3H3 replication in mice were most likely very complex, involving multiple protective responses. Previous studies have already demonstrated that cytokine-mediated immune responses are commonly involved in CVB3-caused myocarditis (33) and may help to reduce or to intensify disease. For example, transgenic overexpression of IFN-γ in pancreas tissue conferred protection of mice from CVB3-induced myocarditis (14) and from CVB4-caused pancreatitis (13). IFN-γ is pluripotent in its function, inducing cellular processes that activate macrophages (12, 34) as well as direct protection (28). Thus IFN-γ produced by CVB3(IFN-γ) may activate nonspecific antiviral immune responses in the pancreas and therefore protect the acinar tissue by the induction of a rapid inflammatory infiltration, which reflects our observation shown in Fig. 3A. In view of the CVB3(IL-10)-induced protection, it was demonstrated earlier that IL-10 can inhibit IL-2 production by lymphocytes (4). Exogenous treatment by IL-2 accentuated the myocardial damage caused by CVB3 (16). In another report, exogenous administration of IL-2 caused prolonged survival and reduced myocardial injury during the 1st week after CVB3 infection in mice, but administration of this cytokine during the 2nd week exacerbated the course of the disease (19). Because IL-10 can inhibit IL-2 production of lymphocytes, IL-10 may prolong survival and attenuate myocardial injury in part by inhibiting IL-2 release. As shown previously, systemic treatment with recombinant IL-10 caused enhanced survival in encephalomyocarditis virus-infected mice by suppression of inflammation during virus-caused myocarditis (27). In addition, immunization with a live-attenuated varicella-zoster virus vaccine induced IFN-γ and IL-10 production in human volunteers and was the prerequisite for an intense T-cell proliferation in primary and memory immune responses (17), indicating that both cytokines may be important for the induction of a long-lasting immunity to some viral antigens.

In general, our data indicate that the simultaneous expression of immunoregulatory cytokines during CVB3 replication can influence the normal pattern of immune pathways, causing an intense protective reaction against subsequent viral infections, which was independent of whether IFN-γ or IL-10 was released by the CVB3rec variants. Further experiments are focused on the characterization of the protective immune responses induced by CVB3(IFN-γ) and CVB3(IL-10).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Katrin Klement, Beate Menzel, and Birgit Meißner for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andino R, Silvera D, Suggett S D, Achacoso P L, Miller C J, Baltimore D, Feinberg M B. Engineering poliovirus as a vaccine vector for the expression of diverse antigens. Science. 1994;265:1448–1451. doi: 10.1126/science.8073288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapman N M, Kim K S, Tracy S, Jackson J, Hofling K, Leser J S, Malone J, Kolbeck P. Coxsackievirus expression of the murine secretory protein interleukin-4 induces increased synthesis of immunoglobulin G1 in mice. J Virol. 2000;74:7952–7962. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.17.7952-7962.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiorentino D F, Bond M W, Mosmann T R. Two types of mouse T helper cell. IV. Th2 clones secrete a factor that inhibits cytokine production by Th1 clones. J Exp Med. 1989;170:2081–2095. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.6.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gauntt C J, Higdon A L, Arizpe H M, Tamayo M R, Crawley R, Henkel R D, Pereira M E, Tracy S M, Cunningham M W. Epitopes shared between coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) and normal heart tissue contribute to CVB3-induced murine myocarditis. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;68:129–134. doi: 10.1006/clin.1993.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hashimoto I, Tatsumi M, Nakagawa M. The role of T lymphocytes in the pathogenesis of Coxsackie virus B3 heart disease. Br J Exp Pathol. 1983;64:497–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henke A, Huber S, Stelzner A, Whitton J L. The role of CD+ T lymphocytes in coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis. J Virol. 1995;69:6720–6728. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6720-6728.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henke A, Launhardt H, Klement K, Stelzner A, Zell R, Munder T. Apoptosis in coxsackievirus B3-caused diseases: interaction between the capsid protein VP2 and the proapoptotic protein Siva. J Virol. 2000;74:4284–4290. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4284-4290.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henke A, Wagner E, Whitton J L, Zell R, Stelzner A. Protection of mice against lethal coxsackievirus B3 infection by using DNA immunization. J Virol. 1998;72:8327–8331. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8327-8331.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henke A, Zell R, Stelzner A. DNA vaccine-mediated immune responses in Coxsackie virus B3-infected mice. Antivi Res. 2001;49:49–54. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(00)00132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Höfling K, Tracy S, Chapman N, Kim K-S, Leser J S. Expression of an antigenic adenovirus epitope in a group B coxsackievirus. J Virol. 2000;74:4570–4578. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.10.4570-4578.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horwitz M S, Evans C F, McGavern D B, Rodriguez M, Oldstone M B. Primary demyelination in transgenic mice expressing interferon-gamma. Nat Med. 1997;3:1037–1041. doi: 10.1038/nm0997-1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horwitz M S, Krahl T, Fine C, Lee J, Sarvetnick N. Protection from lethal coxsackievirus-induced pancreatitis by expression of gamma interferon. J Virol. 1999;73:1756–1766. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.1756-1766.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horwitz M S, La Cava A, Fine C, Rodriguez E, Ilic A, Sarvetnick N. Pancreatic expression of interferon-gamma protects mice from lethal coxsackievirus B3 infection and subsequent myocarditis. Nat Med. 2000;6:693–697. doi: 10.1038/76277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huber S A, Pfaeffle B. Differential Th1 and Th2 cell responses in male and female BALB/c mice infected with coxsackievirus group B type 3. J Virol. 1994;68:5126–5132. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.5126-5132.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huber S A, Polgar J, Schultheiss P, Schwimmbeck P. Augmentation of pathogenesis of coxsackievirus B3 infections in mice by exogenous administration of interleukin-1 and interleukin-2. J Virol. 1994;68:195–206. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.195-206.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jenkins D E, Redman R L, Lam E M, Liu C, Lin I, Arvin A M. Interleukin (IL)-10, IL-12, and interferon-gamma production in primary and memory immune responses to varicella-zoster virus. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:940–948. doi: 10.1086/515702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kandolf R, Ameis D, Kirschner P, Canu A, Hofschneider P H. In situ detection of enteroviral genomes in myocardial cells by nucleic acid hybridization: an approach to the diagnosis of viral heart disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:6272–6276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.17.6272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kishimoto C, Kuroki Y, Hiraoka Y, Ochiai H, Kurokawa M, Sasayama S. Cytokine and murine coxsackievirus B3 myocarditis. Interleukin-2 suppressed myocarditis in the acute stage but enhanced the condition in the subsequent stage. Circulation. 1994;89:2836–2842. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.6.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knowlton K U, Jeon E-S, Berkley N, Wessely R, Huber S. A mutation in the puff region of VP2 attenuates the myocarditic phenotype of an infectious cDNA of the Woodruff variant of coxsackievirus B3. J Virol. 1996;70:7811–7818. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7811-7818.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leipner C, Borchers M, Merkle I, Stelzner A. Coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis in MHC class II-deficient mice. J Hum Virol. 1999;2:102–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leipner C, Grun K, Borchers M, Stelzner A. The outcome of coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3)-induced myocarditis is influenced by the cellular immune status. Herz. 2000;25:245–248. doi: 10.1007/s000590050014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Y, Bourlet T, Andreoletti L, Mosnier J F, Peng T, Yang Y, Archard L C, Pozzetto B, Zhang H. Enteroviral capsid protein VP1 is present in myocardial tissues from some patients with myocarditis or dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2000;101:231–234. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.3.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindberg A M, Crowell R L, Zell R, Kandolf R, Pettersson U. Mapping of the RD phenotype of the Nancy strain of coxsackievirus B3. Virus Res. 1992;24:187–196. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(92)90006-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McManus B M, Chow L H, Wilson J E, Anderson D R, Gulizia J M, Gauntt C J, Klingel K E, Beisel K W, Kandolf R. Direct myocardial injury by enterovirus: a central role in the evolution of murine myocarditis. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;68:159–169. doi: 10.1006/clin.1993.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merkle I, Tonew M, Gluck B, Schmidtke M, Egerer R, Stelzner A. Coxsackievirus B3-induced chronic myocarditis in outbred NMRI mice. J Hum Virol. 1999;2:369–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishio R, Matsumori A, Shioi T, Ishida H, Sasayama S. Treatment of experimental viral myocarditis with interleukin-10. Circulation. 1999;100:1102–1108. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.10.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramsay A J, Ruby J, Ramshaw I A. A case for cytokines as effector molecules in the resolution of virus infection. Immunol Today. 1993;14:155–157. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90277-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reimann B-Y, Zell R, Kandolf R. Mapping of a neutralizing antigenic site of coxsackievirus B4 by construction of an antigen chimera. J Virol. 1991;65:3475–3480. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3475-3480.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schlaak J F, Schmitt E, Huls C, Meyer zum Buschenfelde K H, Fleischer B. A sensitive and specific bioassay for the detection of human interleukin-10. J Immunol Methods. 1994;168:49–54. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmitt E, Van Brandwijk R, Fischer H G, Rude E. Establishment of different T cell sublines using either interleukin 2 or interleukin 4 as growth factors. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:1709–1715. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seder R A, Paul W E. Acquisition of lymphokine-producing phenotype by CD4+ T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:635–673. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seko Y, Takahashi N, Yagita H, Okumura K, Yazaki Y. Expression of cytokine mRNAs in murine hearts with acute myocarditis caused by coxsackievirus b3. J Pathol. 1997;183:105–108. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199709)183:1<105::AID-PATH1094>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spitalny G L, Havell E A. Monoclonal antibody to murine gamma interferon inhibits lymphokine-induced antiviral and macrophage tumoricidal activities. J Exp Med. 1984;159:1560–1565. doi: 10.1084/jem.159.5.1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang S, van Rij R, Silvera D, Andino R. Toward a poliovirus-based simian immunodeficiency virus vaccine: correlation between genetic stability and immunogenicity. J Virol. 1997;71:7841–7850. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7841-7850.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wessely R, Klingel K, Santana L F, Dalton N, Hongo M, Lederer W J, Kandolf R, Knowlton K U. Transgenic expression of replication-restricted enteroviral genomes in heart muscle induces defective excitation-contraction coupling and dilated cardiomyopathy. J Clin Investig. 1998;102:1444–1453. doi: 10.1172/JCI1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Why H J, Meany B T, Richardson P J, Olsen E G, Bowles N E, Cunningham L, Freeke C A, Archard L C. Clinical and prognostic significance of detection of enteroviral RNA in the myocardium of patients with myocarditis or dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1994;89:2582–259. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.6.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]