Abstract

The purpose of this study was to identify the correlates of depressive symptoms and the prevalence of depression, distress, and demoralization among patients with cancer in Taiwan in relation to their sociodemographics. A cross-sectional study design with convenience sampling was used to recruit 191 consecutive patients with cancer from the Cancer Center of a teaching hospital in northern Taiwan. Multiple linear regression was applied to analyze the determinants of depressive symptoms. The prevalence rates of depression (including suspected cases), distress, and demoralization were 17.8%, 36.1%, and 32.5%, respectively. The regression model explained 42.2% of the total variance, with significant predictors including marital status, life dependence, comorbidity, demoralization, and distress. The results demonstrated that higher levels of distress and demoralization were associated with more depressive symptoms. Demoralization and distress played vital roles in moderating depressive symptoms among patients with cancer. Nursing interventions should integrate appropriate mental health services, such as alleviating distress and demoralization, to prevent the occurrence of depression in patients with cancer.

Keywords: nursing, cancer, demoralization, depression, distress, perceived benefits, anxiety, patient experience

1. Introduction

The International Agency for Research on Cancer estimates that in 2022 there were 20 million new cancer patients and 9.7 million cancer-related deaths worldwide [1]. A high proportion (25–35%) of patients with cancer also experience depression [2,3,4]. Cancer patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders are at higher risk of death compared to cancer patients without comorbidity, and they are less likely to receive stage-appropriate treatment [5]. Therefore, early identification of patients with the greatest risk of depression is essential to the early detection of mental health problems.

In Taiwan, depression among patients with cancer has been noted to particularly increase after diagnosis of the cancer, which highlights the importance of mental health care in cancer management [6]. Preventive strategies and integrating identification of the risks of mental disorders among patients with cancer into healthcare systems are key targets for improving mental health wellbeing [7]. Therefore, it is necessary to detect the risk of depression as early as possible and recognize the potential factors that affect depression, so as to subsequently prevent and ameliorate depression in cancer patients.

2. Background

Demoralization, distress, patient experience, perceived benefits, and anxiety are among the risk factors for psychological problems in patients with cancer, and they make such patients vulnerable to depression [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

Demoralization is an existential distress syndrome that involves an incapacity to cope, feelings of hopelessness and helplessness, and a loss of meaning and purpose; it can also compromise one’s self-esteem [15]. Demoralization differs from depression in that patients who feel demoralized retain the ability to feel immediate happiness and more subjective incompetence, whereas those with depression do not. Specifically, the sense of incompetence associated with demoralization is caused by uncertainty about the appropriate direction of action, while depression lacks motivation even if the direction of action is known [16,17,18]. The prevalence rates of demoralization among patients with cancer reportedly range from 13.5% to more than 60% [16,19,20]. According to studies on patients with cancer in Germany (n = 516) by Mehnert et al. [21] and in Taiwan (n = 234) by Lee et al. [22] using the Depression Scale of PHQ-9 and the Demoralization Scale, both correlation matrices have positive associations (r = 0.61, p < 0.001; r = 0.617, p < 0.001, respectively). In addition to the above two articles, a literature review by Robinson et al. pointed out that nine other studies also showed a strong positive correlation between demoralization and depression. A recent systematic review of 36 studies by Wang et al. [19] found that the factors affecting depression associated with cancer are many and complex, including a strong correlation with suicidal ideation and an apparent intersection between demoralization and depression, suicidal ideation, and anxiety.

According to the definition of the NCCN [23], distress is “a multifactorial unpleasant experience of a psychological (i.e., cognitive, behavioral, emotional), social, spiritual, and/or physical nature… Distress extends along a continuum, ranging from common normal feelings of vulnerability, sadness, and fears to problems that can become disabling, such as depression, anxiety, panic, social isolation, and existential and spiritual crisis”. Distress occurs in patients with cancer mainly due to the lack of relevant medical information and inadequate professional treatment, leading to a high degree of uncertainty about the future, which in turn leads to anxiety and depression [11,13]. Distress encompasses anger, anxiety, and depressive symptoms [24]. The rate of distress in recent large-scale studies with more than 1000 people was 33.2% to 46.5% [25,26,27]. Depression has also been significantly related to distress [28,29]. McFarland et al. [29] studied 125 patients with breast cancer and found that the rate of depression (87%) among the physical problems (from the Physical Problem List) of distress was higher than the rates of anxiety (53%) or distress (27%).

The terms “patient experience” and “patient satisfaction” are often used interchangeably by researchers. Patient satisfaction is measured based on many factors falling under “patient experience” before, during, and after care, as well as characteristics of the care environment [30]. According to The Beryl Institute’s [31] definition, the patient experience is “the sum of all interactions, shaped by an organization’s culture, that influence patient perceptions across the continuum of care.” It is a multidimensional, multifaceted, and closely related concept and covers four key themes: personal interactions, organizational culture, patient and family perceptions, and continuum of care [32]. Patient experience therefore includes several aspects of healthcare on which patients place high value when seeking and receiving care, such as timely appointments, easy access to information, and good communication with healthcare providers [33]. According to a study by Bui et al. [10] of patients newly diagnosed with breast cancer (n = 210), each unit increase in depressive symptoms at baseline reduced the predicted odds of being “very satisfied” with medical care at follow-up by 6% (OR = 0.94, 95% CI = 0.89, 0.99). Satisfaction with medical care is negatively correlated with depression [34,35].

“Perceived benefits” are positive psychological changes patients observe in themselves following adversity, such as posttraumatic growth, stress-related growth, and thriving [36,37]. Because negative life experiences (adversity) in patients with cancer, including lower perceived social support and more stressful life events, are associated with depressive symptoms, perceived benefits following adversity may help prevent the onset of depression [38].

Regarding the evolution of anxiety comorbidity, research shows that anxiety disorders often precede the onset of major depression [39]. Interestingly, a study by Maass et al. [40] that included the results of 17 articles showed that depressive symptoms increased in the long term after breast cancer, but anxiety symptoms did not. A recent cross-sectional study surveyed 1011 cancer patients (399 inpatients and 612 outpatients) and found a significant correlation between anxiety and depression (r = 0.812) [41]. In addition, a systematic literature review of 40 studies indicated that four of these showed a positive correlation between anxiety and depression [7].

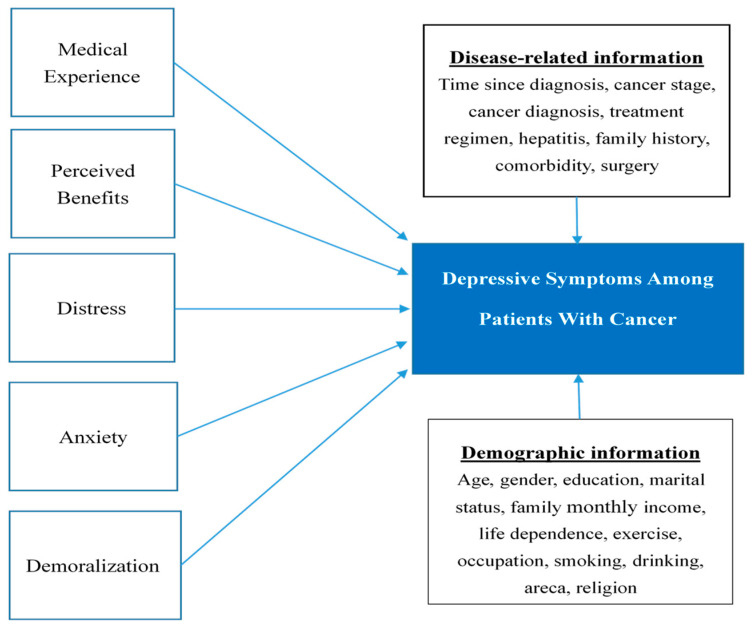

Among these factors, to our knowledge, only demoralization has been extensively studied in Taiwanese populations with cancer [12,22,42,43,44]. However, other psychosocial elements that may lead to depressive somatic symptoms are just as important [45,46]. Hence, we hypothesize that demoralization, distress, perceived benefit, patient experience, and anxiety play important roles in cancer-related depression by influencing the subjective perception of situations and the consequent reactions to them. The conceptual structure of this study is shown in Figure 1. The main aim of this study was to investigate the correlates of depression. The prevalence of depression, distress, and demoralization, and the association of the latter two constructs with depression in patients with cancer, in relation to the patients’ sociodemographic information, were also examined.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design

The study employed a cross-sectional design.

3.2. Instruments with Validity and Reliability

3.2.1. Sociodemographic Information

Baseline demographic data, including age, gender, marital status, education level, occupation, time since diagnosis, household income, diagnosis, pathological stage, treatment plan, substance use (including tobacco, alcohol, and betel nut), history of hepatitis, family history, comorbidity, level of dependence for activities of daily living, exercise habits, and religion, were obtained. Patient medical records outlining cancer diagnosis and treatment were also reviewed.

3.2.2. Distress

The Distress Thermometer (DT) is a validated screening tool for measuring psychological distress; it was endorsed by the NCCN [23]. The DT is a single-item self-reported questionnaire that is used to identify distress from any source. Participants were instructed to circle their answers on a scale of 0 (no distress) to 10 (extremely distressed) to indicate their level of distress in the preceding week. A score of ≥4 was considered the cutoff for a high distress level. The Chinese version of the DT, which included a Problem List, was employed. This version has demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity [47,48].

3.2.3. Demoralization

The Demoralization Scale, Mandarin Version (DS_MV) was developed by Kissane et al. [49] and was translated into Chinese by Hung et al. [44]. This scale evaluates five aspects of demoralization: loss of meaning, dysphoria, disheartenment, helplessness, and a sense of failure. The scale contains 24 items scored using a five-point scoring method, with answers ranging from “strong disagreement” (0 points) to “strong agreement” (4 points). The cutoff score was set at 30 points, with a score of ≥30 points indicating demoralization. Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale was 0.928, and Cronbach’s alpha values for the individual aspects of the scale ranged from 0.63 to 0.88. The convergent and divergent validities were evidenced by a positive correlation with the Beck Hopelessness Scale (r = 0.703, p < 0.001) and a negative correlation with the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (r = −0.680, p < 0.001), respectively [44].

3.2.4. Anxiety and Depression

Anxiety and depression were assessed using the Chinese version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), which has been shown to have favorable reliability, specificity, and sensitivity [48,50]. The HADS is a self-administered questionnaire with two subscales of seven items each to evaluate levels of anxiety (HADS_A) and depression (HADS_D). Each item is scored from 0 to 3 points on a four-point Likert scale, with a higher score indicating a higher degree of anxiety or depression. A total score of less than 7, 8–10, and 11 or more respectively indicates that the patient has no anxiety or depression, has a suspected case of anxiety or depression, or has anxiety or depression [51]. In this study, a score ≥ 8 on the HADS_D questionnaire was considered to indicate depression.

3.2.5. Perceived Benefits

The Perceived Benefit Scale was developed by McMillen and Fisher [52] and translated into Chinese by Wang [53]. The 38-item Chinese version contains five subscales: increased community closeness, enhanced family closeness, enhanced self-efficacy, increased spirituality, and increased compassion. The subscales are scored using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (not at all like my experience) to 4 (very much like my experience). Cronbach’s α for the subscales of the original scale ranged from 0.73 to 0.93, and for the Chinese version ranged from 0.76 to 0.86. The reliability of the original scale after two weeks ranged from 0.66 to 0.97. The Chinese version had expert and construct validity [53].

3.2.6. Patient Experience

The Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) is a 20-item self-reporting instrument for assessing patients’ reception of clinical services and actions consistent with the Chronic Care Model, which was developed to ensure that patients receive care that is patient-centered, proactive, and well-planned and includes collaborative goal setting, problem solving, and follow-up. The PACIC has five subscales: patient activation, decision support, goal setting, problem solving, and follow-up or coordination. Cronbach’s α for the total scale was 0.93, and those for the subscales ranged from 0.77 to 0.90. The scale was demonstrated to have favorable construct validity and content validity [54].

3.3. Sampling and Recruitment

A convenience sampling method was used to recruit outpatients who were undergoing active cancer treatment, including surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy, in a cancer center in northern Taiwan. Patients who met the following criteria were included: age ≥ 20 years, absence of a psychiatric diagnosis, ability to speak Chinese, and willingness to participate in the study and provide written informed consent.

3.4. Sample Size and Power

In establishing the sample size, we considered α = 0.05, β = 0.2, the medium effect size = 0.25, and a 20% dropout rate. Of the 472 qualifying patients, a total of 191 were included in the sample, which fulfilled the minimum required sample size of 154 as estimated using G Power software version 3.1.

3.5. Data Sources/Collection

Patients were recruited through convenience sampling conducted from January 2019 to January 2020. Before recruiting patients during their outpatient visits, the principal investigator first discussed the study with the physicians of the cancer center and obtained their consent. Researchers then screened for patients who met the criteria for inclusion by searching the hospital outpatient information system for patients with qualifying medical-related information.

Initial contact with patients was made via telephone, during which the researchers provided an overview of the study’s purpose, procedures, and benefits. Patients who expressed interest in participating were then scheduled for a face-to-face meeting with the researchers during their outpatient visit. During this meeting, the researchers provided a detailed explanation of the study, including relevant benefits, potential risks, data processing, and utilization. Participants were given ample opportunity to ask questions and clarify any concerns. Trained researchers were available to assist and ensure participants fully understood the study before they signed the informed consent form and completed the study questionnaires. However, the data collection process was thoroughly documented as part of the overall research plan, with specific details available in the publication by Yu et al. [55].

3.6. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 24 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Missing values were handled by pairwise deletion. Descriptive statistics and frequency distributions were calculated for the lists of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. The t-test and analysis of variance were performed to determine differences in sociodemographic and disease-related variables with respect to depression. The prevalence of distress, anxiety, depression, and demoralization was determined using descriptive statistics and frequency analysis. Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to identify potential associations among age, time since diagnosis, distress, anxiety, depression, demoralization, perceived benefits, and patient experience. Finally, multiple linear regression was used to identify the determinants of depressive symptoms. The dependent variable (depressive symptoms) was a continuous variable. The independent variables were selected based on the statistical method proposed by Bursac et al. [56]. Factors that showed significant results in the chi-squared tests, t-tests, and Pearson correlation analyses of the aforementioned sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were included in the multiple linear regression model. This approach was used to analyze the factors influencing depressive symptoms, thereby avoiding potential issues such as model instability, inflated results, or unreasonable outcomes that could arise from including categorical variables with small sample sizes or too many variables with minimal influence. Categorical variables were converted into dummy variables for analysis. The enter method was used for the multiple linear regression analysis. A p-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

3.7. Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Joint Institutional Review Board of a medical university in northern Taiwan (IRB number N201809031). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The informed consent process involved providing participants with detailed information about the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits, as well as their right to withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences. Consent forms were signed by the participants and were securely stored in a locked file cabinet accessible only to authorized research personnel. All participants were provided with a copy of the consent form for their records.

4. Results

4.1. Sociodemographic and Disease-Related Information

4.1.1. Demographic Information

Overall, 191 out of the 472 qualifying patients completed the questionnaires, indicating an overall response rate of 40.5%. The main reason for refusal to participate was not having time to complete the study questionnaires. The mean age of patients was 55.3 ± 12.04 years. As indicated in Table 1, the participants were primarily women (73.3%) and married (62.8%), and seven out of ten patients reported religious affiliations. Among the patients with cancer, higher levels of depressive symptoms were experienced by males and those with a household income per month of less than TWD$ 29,999 and within the range of TWD$ 70,000 to 89,999; smokers; those who were separated or divorced; and those with a high level of dependence in life. However, the Scheffé test did not reveal significant differences among patients with different household monthly incomes.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for demographics and differences in HADS_D (N = 191).

| Number (n)/Mean (SD) | Percent (%) |

HADS_D (Mean) |

HADS_D (SD) |

p-Value/ Statistics |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 55.3 (12.04) | - | - | - | - |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 51 | 26.7 | 5.75 | 3.155 | p = 0.005 |

| Female | 140 | 73.3 | 4.38 | 2.865 | t = 2.837 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 47 | 24.6 | 4.04 | 2.621 |

p = 0.001 F = 7.766 post hoc: single vs. other p = 0.010 married vs. other p = 0.036 |

| Married | 120 | 62.8 | 4.6 | 2.748 | |

| Other (separated, divorced) |

24 | 12.6 | 6.83 | 3.975 | |

| Occupation | |||||

| No | 101 | 52.9 | 4.95 | 3.339 | p = 0.306 |

| Yes | 90 | 47.1 | 4.51 | 2.563 | t = 1.026 |

| Education | |||||

| ≤Primary school (9 grade) |

31 | 16.2 | 5.45 | 3.793 |

p = 0.541 F = 0.720 |

| High school | 54 | 28.3 | 4.63 | 3.036 | |

| College graduate | 90 | 47.1 | 4.56 | 2.805 | |

| Postgraduate degree | 16 | 8.4 | 4.81 | 2.136 | |

| Family monthly income (TWD) (N = 181) | |||||

| ≤29,999 | 33 | 17.3 | 5.52 | 3.607 |

p = 0.036 F = 2.639 post hoc: (Scheffé) non-significant |

| 30,000–49,999 | 38 | 19.9 | 3.71 | 2.680 | |

| 50,000–69,999 | 43 | 22.5 | 4.86 | 2.900 | |

| 70,000–89,999 | 19 | 9.9 | 5.74 | 2.557 | |

| ≥90,000 | 48 | 25.1 | 4.25 | 2.733 | |

| Smoking | |||||

| No | 145 | 75.9 | 4.32 | 2.784 | p = 0.001 |

| Yes a | 46 | 24.1 | 6.07 | 3.289 | t = 3.533 |

| Drinking | |||||

| No | 99 | 51.8 | 4.81 | 3.212 | p = 0.757 |

| Yes | 92 | 48.2 | 4.67 | 2.766 | t = 0.310 |

| Areca (betel nut) | |||||

| No | 173 | 90.6 | 4.62 | 2.872 | p = 0.074 |

| Yes | 18 | 9.4 | 5.94 | 3.918 | t = −1.796 |

| Life dependence | |||||

| No | 173 | 90.6 | 4.45 | 2.699 | p = 0.005 |

| Yes | 18 | 9.4 | 7.61 | 4.146 | t = −3.170 |

| Exercise | |||||

| No | 61 | 31.9 | 5.28 | 3.312 | p = 0.101 |

| Yes | 129 | 67.5 | 4.47 | 2.812 | t = 1.657 |

| Religion | |||||

| No | 54 | 28.3 | 4.96 | 3.040 | p = 0.527 |

| Yes | 137 | 71.7 | 4.66 | 2.989 | t = 0.634 |

Abbreviations: HADS_D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale–Depression; a “Smoking:Yes” refers to occasional smoking (only in social situations, never alone), current smoking (smoking addiction), and abstinence.

4.1.2. Disease-Related Information

Stage 0 refers to cancer in situ that has not spread [57,58]. Most of the respondents were in stage I (25.7%) of their cancer, followed by stage II (25.1%), stage IV (25.1%), stage III (15.7%), and stage 0 (8.4%). Regarding tumor type, almost half of the patients (53.4%) had breast cancer, followed by other cancers (23.6%) (such as prostate, oral, gynecological, lymphoma, and liver), colorectal (11.5%), lung (5.8%), and gastrointestinal/pancreatic cancer (5.8%). Regarding treatment, 40% of the patients were undergoing more than two treatment plans, whereas just 2.1% were undergoing forms of treatment other than chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormone therapy, and target therapies. Chemotherapy was the preferred treatment (31.4%). Furthermore, almost half of the patients (49.7%) had a family history of cancer, and more than a third (38.7%) had comorbidity; 13.6% of patients had hepatitis. The disease-related information is presented in Table 2. Among the patients with cancer, higher levels of depressive symptoms were experienced by those with more comorbidity. Patients who were given diagnoses of gastric or pancreatic cancer experienced the highest level of depressive symptoms. However, the Scheffé test did not reveal significant differences among patients given different cancer diagnoses.

Table 2.

Differences in disease-related information (N = 191).

| Characteristic | Number (%) | HADS_D (Mean ± SD) |

Statistics, p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time since diagnosis | |||

| ≤1 year | 129 (67.5) | 4.53 ± 3.03 | t = −1.390, p = 0.166 |

| >1 year | 62 (32.5) | 5.23 ± 2.90 | |

| Cancer stage | |||

| 0 | 16 (8.4) | 3.63 ± 3.38 | F = 1.762, p= 0.138 |

| I | 49 (25.7) | 4.55 ± 2.72 | |

| II | 48 (25.1) | 4.6 ± 2.76 | |

| III | 30 (15.7) | 4.47 ± 3.18 | |

| IV | 48 (25.1) | 5.63 ± 3.16 | |

| Cancer Diagnosis | |||

| Colorectal | 22 (11.5) | 5.59 ± 3.23 | F = 3.161, p= 0.015 post hoc: no significant (Scheffé) |

| Lung | 11 (5.8) | 5.55 ± 2.58 | |

| Breast | 102 (53.4) | 4.04 ± 2.63 | |

| Gastric & pancreatic | 11 (5.8) | 5.64 ± 4.32 | |

| Others (prostate, oral, gynecological, lymphoma, liver) | 45 (23.6) | 5.51 ± 3.12 | |

| Treatment regimen | |||

| Chemotherapy | 60 (31.4) | 5.17 ± 3.13 | F = 2.149, p = 0.062 |

| Radiotherapy | 38 (19.9) | 3.84 ± 2.69 | |

| Hormone | 26 (13.6) | 3.77 ± 2.03 | |

| Target | 23 (12) | 5.78 ± 3.64 | |

| More than two types | 40 (20.9) | 5 ± 2.96 | |

| Others (surgery, folk medicine) |

4 (2.1) | 4.75 ± 3.30 | |

| Hepatitis | |||

| No | 165(86.4) | 4.61 ± 2.95 | t = −1.530, p = 0.128 |

| Yes | 26 (13.6) | 5.58 ± 3.25 | |

| Family history | |||

| No | 83 (43.5) | 4.89 ± 3.02 | F = 1.159, p = 0.316 |

| Unknown | 13 (6.8) | 3.54 ± 2.82 | |

| Yes | 95 (49.7) | 4.78 ± 2.99 | |

| Comorbidity | |||

| No | 117 (61.3) | 4.36 ± 2.73 | t = −2.252, p = 0.025 |

| Yes | 74 (38.7) | 5.35 ± 3.30 | |

| Surgery (n = 190) | |||

| No | 34 (17.8) | 5.44 ± 2.92 | t = 1.47, p = 0.143 |

| Yes | 156 (82.1) | 4.61 ± 3.01 |

Abbreviations: HADS_D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale–Depression.

4.2. Prevalence of Depressions, Anxiety, Demoralization, and Distress

The mean HADS_D, HADS_A, DS_MV, and DT scores were 4.74 (SD = 3.00), 5.1 (SD = 3.08), 24.71 (SD = 12.51), and 2.96 (SD = 2.34), respectively. The prevalence rates of depression, anxiety (including suspected), and demoralization were 17.8%, 19.4%, and 32.5%, respectively. In addition, 36.1% of participants (69/191) experienced a high level of distress, and 4.97% (9/191) were highly vulnerable patients with scores that met the cutoff points for the HADS_D (including suspected), HADS_A (including suspected), DS_MV, and DT. The mean HADS_D score was 9.56 (SD = 2.46). The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Scores and cutoff points for depression, anxiety, demoralization, and distress (N = 191).

| Number (%) | Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|

| HADS_D | 4.74 ± 3.00 | |

| Non-depression (<8) | 157 (82.2) | 3.73 ± 2.12 |

| Suspected (8–10) | 26 (13.6) | 8.58 ± 0.86 |

| Depression (≥11) | 8 (4.2) | 12.13 ± 1.36 |

| HADS_A | 5.1 ± 3.08 | |

| Non-anxiety (<8) | 154 (80.6) | 4.11 ± 2.21 |

| Suspected (8–10) | 29 (15.2) | 8.76 ± 0.83 |

| Anxiety (≥11) | 8 (4.2) | 12.88 ± 1.64 |

| DT degree | 2.96 ± 2.34 | |

| <4 | 122 (63.9) | 1.45 ± 1.12 |

| ≥4 | 69 (36.1) | 5.62 ± 1.34 |

| DS_MV degree | 24.71 ± 12.51 | |

| <30 | 129 (67.5) | 18.11 ± 8.19 |

| ≥30 | 62 (32.5) | 38.45 ± 7.91 |

| HADS_D ≥ 8, HADS_A ≥ 8, DT ≥ 4, and DS_MV ≥ 30 a | 9 (4.97) | 9.56 ± 2.46 (for HADS_D) |

Abbreviations: HADS_A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale–Anxiety; DT, Distress Thermometer; DS_MV, Demoralization Scale–Mandarin Version; a Scores of all four scales are greater than or equal to the cutoff point.

4.3. Correlations between Age, Time since Diagnosis, and Study Variables

The correlations between age, time since diagnosis, and the study variables are presented in Table 4. Depression was significantly and positively associated with anxiety (r = 0.34, p < 0.001), psychological distress (r = 0.38, p < 0.001), and demoralization (r = 0.57, p < 0.001). By contrast, depression was significantly and negatively associated with perceived benefit (r = −0.26, p < 0.001) and patient experience (r = −0.19, p = 0.007). No significant correlation was identified between age and time since diagnosis (r = 0.08/0.04, p > 0.05).

Table 4.

Summary of Pearson correlation coefficients between age, time since diagnosis, HADS_D, HADS_A, PBS, DT, and PACIC.

| Age | Time Since Diagnosis | HADS_D | HADS_A | DT | DS_MV | PBS | PACIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1 | |||||||

| Time since diagnosis | 0.06 | 1 | ||||||

| HADS_D | 0.08 | 0.04 | 1 | |||||

| HADS_A | −0.17 * | 0.10 | 0.34 *** | 1 | ||||

| DT | −0.14 | 0.06 | 0.38 *** | 0.51 *** | 1 | |||

| DS_MV | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.57 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.46 *** | 1 | ||

| PBS | 0.23 ** | 0.03 | −0.26 *** | −0.18 * | −0.15 * | −0.40 *** | 1 | |

| PACIC | 0.05 | −0.1 | −0.19 ** | −0.16 * | −0.15 * | −0.23 ** | 0.25 *** | 1 |

Abbreviations: HADS_D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale–Depression; HADS_A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale–Anxiety; DT, Distress Thermometer; DS_MV, Demoralization Scale, Mandarin Version; PBS, Perceived Benefits Scale; PACIC, Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

4.4. Analysis of Determinants of Depressive Symptoms

Based on the results of the previous difference analysis in Table 1 and Table 2, the significant variables identified were gender, marital status, smoking, life dependence, comorbidity, and the scores of major indicators (Anxiety Scale, Depression Scale, Distress Thermometer, Perceived Benefit Scale, and Patient Medical Experience Scale). These variables were included in the multiple linear regression model analysis with the dependent variable being the Depression Scale score. The model indicated that current smoking habits, life dependence, comorbidity, distress, and demoralization are important determinants of depressive symptoms. The results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Potential variables associated with depression in patients with cancer.

| Potential Variables | Univariate Regression Analysis | Multiple Regression Analysis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% CI for B | β | p | B | 95% CI for B | β | p | |||

| Age | 0.021 | −0.015 | 0.057 | 0.084 | 0.248 | 0.006 | −0.026 | 0.039 | 0.025 | 0.709 |

| Gender_male | 1.367 | 0.417 | 2.317 | 0.202 | 0.005 | 0.784 | −0.181 | 1.749 | 0.116 | 0.111 |

| Smoking | 1.741 | 0.769 | 2.713 | 0.249 | 0.001 | 0.689 | −0.268 | 1.646 | 0.099 | 0.157 |

| Life dependence | 3.166 | 1.769 | 4.563 | 0.309 | <0.001 | 1.915 | 0.745 | 3.085 | 0.187 | 0.001 |

| Marital status_single (vs. other) | −2.791 | −4.225 | −1.357 | −0.402 | <0.001 | −1.670 | −2.866 | −0.474 | −0.240 | 0.006 |

| Marital status_married (vs. other) | −2.233 | −3.511 | −0.955 | −0.361 | 0.001 | −1.546 | −2.594 | −0.498 | −0.250 | 0.004 |

| Comorbidity | 0.992 | 0.123 | 1.862 | 0.162 | 0.025 | 0.865 | 0.131 | 1.598 | 0.141 | 0.021 |

| DT | 0.489 | 0.319 | 0.658 | 0.382 | <0.001 | 0.182 | 0.011 | 0.353 | 0.142 | 0.037 |

| DS_MV | 0.136 | 0.107 | 0.164 | 0.565 | <0.001 | 0.073 | 0.035 | 0.110 | 0.303 | <0.001 |

| PBS | −0.047 | −0.072 | −0.022 | −0.264 | <0.001 | −0.011 | −0.034 | 0.012 | −0.061 | 0.344 |

| Anxiety | 0.330 | 0.199 | 0.462 | 0.339 | <0.001 | 0.084 | −0.056 | 0.223 | 0.086 | 0.237 |

| PACIC | −0.609 | −1.052 | −0.166 | −0.193 | 0.007 | −0.155 | −0.515 | 0.206 | −0.049 | 0.398 |

Abbreviations: CI, Confidence Interval; vs., versus.

Regarding psychological predictors, after adjusting for basic demographic and disease-related variables, for each standard deviation increase in depression (DS_MV score), the depression score increased by 0.303 standard deviations (95% CI for B = 0.035–0.110, p < 0.001). For each standard deviation increase in distress (DT score), the depression score increased by 0.142 standard deviations (95% CI for B = 0.011–0.353, p = 0.037). Therefore, among all predictors, demoralization (DS_MV score) had the greatest impact. After adjusting for basic variables including smoking habits, life dependence, comorbidity, and distress, each one-unit (point) increase in demoralization (DS_MV score) resulted in a 0.073-point increase in the depression score. After adjusting for basic variables such as smoking habits, life dependence, comorbidity, and demoralization, each one-unit (point) increase in distress (DT score) resulted in a 0.182-point increase in the depression score. Collectively, these independent variables (Marital status_single, Marital status_married, life dependence, comorbidity, distress, and demoralization) explained 42.2% of the variance in depression.

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Purpose and Findings

The main purpose of this study was to explore the correlates of depressive symptoms among patients with cancer in Taiwan. It also investigated the prevalence of depression, demoralization, and distress among patients with cancer in Taiwan as well as the sociodemographic characteristics and disease-related factors that affect the prevalence of depression. The results revealed that the prevalence of distress (36.1%) among patients with cancer was higher than that of depression (17.8%) and demoralization (32.5%). Marital status, life dependence, and comorbidity were significant predictors of depression, with higher levels of distress and demoralization correlating with increased depressive symptoms.

5.2. Comparison with Previous Studies

The findings of this study indicate that the rate of depression (including suspected depression) among patients with cancer in Taiwan is approximately 17.8%. However, a study in Australia reported the depression rate among patients with cancer to be 45% [59]. This rate is much higher than that calculated in our study. The discrepancy may be due to differences in disease characteristics, types of cancer treatment, number of side effects of cancer treatment, and assessment methods [60]. In addition, cultural differences may have influenced the reported incidence of depressive symptoms among patients with cancer. Compared with the personal orientation of Europe and the United States, Chinese people are more family-oriented and less revealing of their feelings and taboos about death [61,62]. Asian patients often focus more on physical rather than psychological symptoms, and the depressive symptoms may have been underestimated in our study [63].

The prevalence of demoralization in our study was 32.5%, which was higher than the global prevalence of 13–18% found in the systematic review by Robinson et al. [17]. Their study used PRISMA guidelines to search nine electronic bibliographic databases and found 33 articles from 2000 to 2013, with a total of 4545 participants from Australia, the United States, Italy, Taiwan, Hungary, Germany, Japan, Ireland, and Portugal. The prevalence of demoralization may be driven by the influence of sociodemographic and psychological factors. Research indicates that older age is associated with higher scores for demoralization [16]. In addition, patients with cancer who reported being unemployed had higher scores for demoralization [17]. The majority of our participants were women, older adults, and were unemployed; these demographic factors likely led to the prevalence of demoralization being higher in our study than in others. Furthermore, demoralization is related to psychological factors; patients with cancer who experience depression are prone to demoralization [17]. Given that our participants had higher levels of depression, the higher prevalence of demoralization in our study is unsurprising.

Regarding anxiety, this study found a prevalence rate of 19.4% (including suspected cases), which is consistent with the 19.1% rate reported by Naser et al. [41] at the Amman Cancer Center, despite their study excluding suspected anxiety cases. The higher anxiety prevalence in our study may be attributed to the specific cancer types in our population, as nearly two-thirds were diagnosed with lung, breast, prostate, or head and neck cancers—types known to be associated with higher anxiety levels [46]. Similarly, Goerling et al. [64] reported a 13.8% anxiety prevalence in a German multicenter study using the GAD-7, with particularly high anxiety risks in bladder and testicular cancer patients (OR, 5.3; 95% CI = 3.0–9.4). The differences in cancer types and our smaller sample size limit direct comparisons, but these findings align with our observation of elevated anxiety levels in specific cancer populations. Additionally, a meta-analysis incorporating 36 studies and 16,298 breast cancer patients reported an anxiety prevalence rate of 41.9% (95% CI = 30.7–53.2), underscoring the high prevalence of anxiety in this population. The study highlighted the significant impact of psychological factors on anxiety levels among breast cancer patients, emphasizing the importance of addressing these factors in clinical care [65].

Distress is a common mental health problem that occurs among patients with cancer. In this study, almost a third of the participants experienced distress. However, a study from Australia found that almost 91% of patients with cancer reported clinically significant stress, indicating that the prevalence in that study was three times higher than that in our study. The discrepancy may be related to cultural values. People from Western countries were found to seek support when they perceived information or treatment to be insufficient, rather than continue to complete the routine procedure, which may explain why they report distress more frequently than Asian people do [13,66].

In this study, the prevalence of chronic comorbidities among cancer patients was 38.7%. Generally, cancer patients tend to have more physical comorbidities compared to those without a history of cancer. According to Petrova et al. [67], who analyzed 484 patients in Spain diagnosed with cancer within a year, the prevalence of chronic comorbidities was 89.7%. Furthermore, each additional comorbidity increased the likelihood of psychological distress (GHQ-12) by 9% (OR = 1.09, 95% CI = 1.01–1.16). Another study in the United States involving 2073 cancer patients found a significant association between the number of comorbidities at the time of cancer diagnosis and the risk of recent depression (PHQ-9), with those having multiple comorbidities being 3.48 times more likely to exhibit significant depressive symptoms within five years compared to those without comorbidities (95% CI = 1.26–9.55). The most impactful comorbidities were stroke, kidney disease, hypertension, obesity, asthma, and arthritis [68]. Additionally, a study in China with 1546 participants found that cancer patients with one or two chronic comorbidities were 1.35 times more likely to suffer from depression (95% CI = 1.04–1.75, p = 0.022), and those with three or more comorbidities were 1.74 times more likely (95% CI = 1.30–2.33, p < 0.001) [69]. The primary difference between these studies and the current research is the stage of patients; while previous studies focused on post-treatment patients, this research involves patients in various stages of treatment. Nevertheless, comorbidities consistently emerge as predictors of depressive symptoms.

Numerous studies have shown that as cancer patients’ self-care abilities improve, their dependence on others is reduced, leading to a reduction in depressive symptoms [70,71,72]. Self-care ability and dependence on others are inversely related [73,74]. When self-care ability declines, dependence on others increases correspondingly [74]. Due to mobility impairments caused by the disease, cancer patients often rely on others for daily care, which diminishes their independence and sense of control, contributing to depression. Additionally, the guilt associated with requiring care and the financial burdens they face can further exacerbate emotional distress, making depressive symptoms more likely [72,74,75]. This study also found that life dependence is a significant factor influencing depression symptoms. People who are dependent on others and unable to care for themselves exhibit more severe depression problems than those who maintain independence.

The results of the present study indicate that women tended to have lower levels of depression than men. However, another study reported lower depression levels in men [76]. A recent study in Taiwan found that men with prostate cancer had higher anxiety and depression problems, which may be due to the cultural phenomenon that men value “face” and dignity more than women, suppress emotions, and limit social support [77]. Furthermore, this could be explained by the greater age of most men in our study. Older patients experience depression more often because they experience multiple losses in their lives over a short period. In addition to experiencing declining health due to cancer and age, many older patients experience the loss of a spouse, functional impairment, and a poor social network, which leads them to feel more depressed [78,79,80,81]. They also experience lower levels of concentration and difficulty in remembering, which prevent them from recognizing that they have experienced symptoms of depression and lead them to delay seeking help.

The results of this study indicate that smoking was associated with a higher risk of depression. According to the self-medication model, people smoke because they want to alleviate psychological symptoms [82]. When these people experience symptoms of depression, they attempt to minimize them by smoking. However, the relationship between smoking and depression is bidirectional, which indicates that prolonged smoking can also perpetuate depression [82]. Choi and Park [83] conducted a study in Korea involving 1163 cancer survivors and found that smokers had a 1.7 times higher risk of depression compared to non-smokers (OR = 1.73, 95% CI = 1.04–2.87).

In this study, having an “other” marital status, such as being separated or divorced, was revealed to be a risk factor for depression. Similar to a previous study [84], the prevalence of depression among widows who were diagnosed with cancer was found to be higher than that of married patients. Patients who are separated or divorced may not have someone with whom they can share emotions, thoughts, or decisions or who can provide them with support for treatments and healthcare visits. Therefore, when patients lose support, they are at a higher risk of developing depression. The results indicate that patients with colorectal cancer and other types of cancer were more likely to have depression compared to those with breast cancer. This is in line with the findings reported in a previous study [2]. Patients with breast cancer are usually mildly depressed and may have improved family support, self-care, patient satisfaction, and medical care related to the improvement of quality of life [66,85].

This study demonstrated that distress and demoralization significantly affect depression. This is in line with the findings of Robinson et al. [17], who demonstrated that demoralization can be a risk factor for or a prodromal symptom of depression. This could explain why most patients with cancer who felt demoralized had similar symptoms to those of depression, such as feelings of sadness and a loss of hope. The prolonged loss of enjoyment resulting from experiencing cancer may be associated with a loss of hope and a feeling that life is no longer worth living, which may precede depression [16].

The results of the present study suggest that distress can increase the risk of depression. The risk of depression is commonly believed to significantly increase when distress levels are higher, which can affect a patient’s quality of life [86]. However, Ng et al. [87] reported no association between any level of distress and depression. Their results may be explained by the complexity of depression among patients with cancer, with the symptoms often varying in clinical presentation, leading to some features potentially being underestimated or overestimated. This variation often leads to clinicians misidentifying symptoms of depression, which may explain why some studies have identified an association between distress and depression while others have not. Furthermore, this relationship may be mediated by patients’ strategies for coping with their illness trajectories [86], although in the current study, we did not explore coping strategies. Further investigation may be warranted to clarify this potential relationship.

This study revealed that perceived benefits, including aspects related to social support such as increased community and family closeness, could serve as a protective factor against depression. People often report having benefited from negative life events, like a cancer diagnosis [52], which can accelerate patients’ recovery and enhance psychosocial functioning. However, the results did not show a significant impact of perceived benefits on depressive symptoms. Despite this, social support remains a crucial aspect of mental health for cancer patients. While perceived benefits as a whole might not have significantly influenced depression in our sample, specific elements of social support could still play a vital role.

The regression model employed in our study explained 42.2% of the total variance. According to previous reports, personal health behaviors (physical activity or smoking habits), social status (low degree of social support such as being separated or divorced, and life dependence), and psychological status (demoralization and distress) can reflect psychological morbidity more accurately than can disease characteristics [88,89]. In the current study, sociodemographic and psychological factors played key roles in influencing the development of depression among patients with cancer.

Although previous literature and clinical observations suggest that different cancer types, such as breast cancer, might influence depressive symptoms due to their unique biopsychological contexts, our analysis did not find cancer type to be a significant predictor. A Scheffé post-hoc test showed no significant differences in depressive symptoms among the cancer type. Even after including cancer type in the multiple linear regression model (as shown in Supplementary Table S1), it remained non-significant. This result suggests that, within our study population, depressive symptoms are more strongly influenced by factors such as psychological distress and demoralization rather than the specific type of cancer. This finding underscores the importance of focusing on psychosocial factors when addressing depression in cancer patients, rather than assuming that cancer type alone will dictate the psychological outcomes.

5.3. Limitations of the Work

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, the use of convenience sampling may introduce selection bias, as certain characteristics of the participants may be overrepresented or underrepresented. Second, while we initially considered cancer type as a potential predictor of depressive symptoms, it was excluded from the final regression model due to its lack of significant impact. This exclusion suggests that cancer type may not significantly influence depressive symptoms within our sample. However, this finding may not be generalizable to larger or more diverse populations, where cancer type could play a more significant role. The absence of a significant effect may also reflect the specific characteristics of our sample rather than a universal finding, indicating that future studies with larger sample sizes and diverse cancer types are needed to clarify the role of cancer type in the psychological outcomes of cancer patients. Additionally, the study did not account for biological mechanisms that might induce depression, such as those activated by medications used to alleviate cancer treatment side effects. This omission limits our understanding of the potential interplay between biological and psychological factors in the development of depressive symptoms. Moreover, the reliance on self-reported questionnaires could have led to an overestimation of the prevalence of depression, as patients might have exaggerated or understated their symptoms, affecting the accuracy of the data collected. Furthermore, because participants in this study were recruited from a single referral hospital in northern Taiwan, the findings may not be generalizable to other populations. The cultural context of Taiwan, including specific attitudes toward mental health and the experience of illness, might also have influenced how patients reported and perceived depressive symptoms. In particular, there is a cultural tendency among some patients to self-attribute their cancer diagnosis to bad living habits and irresponsibility for their own health [90]. This self-blame may exacerbate feelings of guilt and shame, potentially influencing how they experience and report depressive symptoms. Such cultural factors could contribute to variations in how depression is recognized and addressed among cancer patients in Taiwan, complicating the interpretation of the study’s findings.

5.4. Recommendations for Further Research

To address the study’s limitations and build on its findings, future research should employ random sampling to improve representativeness and generalizability. Incorporating biological markers and treatment variables will enhance our understanding of how biological mechanisms contribute to depression in cancer patients. Since our findings indicated that cancer type did not significantly impact depressive symptoms within our sample, future studies should explore this further in larger, more diverse populations to determine if this result holds true in different contexts. Detecting patients’ distress and demoralization can help identify the likelihood of these patients suffering from depression and slow the progression of depression. Regular assessments of these underlying factors could provide valuable insights into the mental health trajectory of cancer patients. Additionally, integrating clinical assessments or longitudinal follow-ups with self-reported data would allow for more accurate estimates of depression prevalence, reducing potential biases. A multidisciplinary approach to nursing interventions could be designed to assess the reduction in distress-related maladaptive outcomes. Furthermore, real-time services via telephone and dedicated internet lines can also be provided to establish good communication channels, allowing cancer patients to easily obtain medical care-related information and assist them with medical treatment and adjustment at home. Finally, future research should also more directly investigate the impact of social support, potentially isolating it from broader constructs like perceived benefits, to better understand its moderating effects on depression among cancer patients [9].

6. Conclusions

The prevalence of depression among the Taiwanese population with cancer is similar to global prevalence. Depression was influenced by distress, demoralization, and perceived benefits. Patients with higher levels of distress and demoralization were more vulnerable to developing depression, whereas higher perceived benefits were a protective factor that led patients with cancer to be less prone to developing depression. These findings expand upon our understanding of the role of demoralization and psychological distress in predicting depressive symptoms in patients with cancer. Nursing interventions should integrate appropriate mental health services to prevent negative outcomes of depression in patients with cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan for their support. We also extend our gratitude to all the participants in this study for their valuable contributions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/curroncol31100431/s1, Table S1: Multiple linear regression analysis of depression in cancer patients, including cancer type.

Author Contributions

W.-Z.Y. and H.-J.C.; methodology, W.-Z.Y., N.H., C.-S.L. and H.-J.C.; software, C.-S.L., W.-Z.Y. and N.H.; validation, W.-Z.Y., Y.-C.H. and H.-J.C.; formal analysis, Y.-C.H. and W.-Z.Y.; investigation, W.-Z.Y., H.-F.W. and Y.-L.L.; resources, H.-F.W., Y.-L.L. and Y.Y.; data curation, Y.-C.H., C.-S.L. and W.-Z.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, W.-Z.Y. and N.H.; writing—review and editing, W.-Z.Y. and H.-J.C.; visualization, W.-Z.Y.; supervision, Y.Y. and H.-J.C.; project administration, W.-Z.Y. and H.-J.C.; funding acquisition, H.-J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Joint Institutional Review Board of a medical university in northern Taiwan (IRB number N201809031). The approve date was 30 October 2018.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data from our study are unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (grant number: 108-6001-006-300).

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Union for International Cancer Control [UICC] GLOBOCAN 2022: Latest Global Cancer Data Shows Rising Incidence and Stark Inequities. [(accessed on 1 February 2024)]. Available online: https://www.uicc.org/news/globocan-2022-latest-global-cancer-data-shows-rising-incidence-and-stark-inequities.

- 2.Pitman A., Suleman S., Hyde N., Hodgkiss A. Depression and anxiety in patients with cancer. BMJ. 2018;361:k1415. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caruso R., Nanni M.G., Riba M., Sabato S., Mitchell A.J., Croce E., Grassi L. Depressive spectrum disorders in cancer: Prevalence, risk factors and screening for depression: A critical review. Acta Oncol. 2017;56:146–155. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2016.1266090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gold S.M., Köhler-Forsberg O., Moss-Morris R., Mehnert A., Miranda J.J., Bullinger M., Steptoe A., Whooley M.A., Otte C. Comorbid depression in medical diseases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2020;6:69. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0200-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charlesworth L., Fegan C., Ashmore R. How does severe mental illness impact on cancer outcomes in individuals with severe mental illness and cancer? A scoping review of the literature. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Sci. 2023;54:S104–S114. doi: 10.1016/j.jmir.2023.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee M.J., Huang C.W., Lee C.P., Kuo T.Y., Fang Y.H., Chin-Hung Chen V., Yang Y.H. Investigation of anxiety and depressive disorders and psychiatric medication use before and after cancer diagnosis. Psycho-Oncol. 2021;30:919–927. doi: 10.1002/pon.5672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riedl D., Schüßler G. Factors associated with and risk factors for depression in cancer patients—A systematic literature review. Transl. Oncol. 2022;16:101328. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett J.A., Cameron L.D., Brown P.M., Whitehead L.C., Porter D., Ottaway-Parkes T., Robinson E. Time since diagnosis as a predictor of symptoms, depression, cognition, social concerns, perceived benefits, and overall health in cancer survivors. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2010;37:331–338. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.331-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bourdon M., Blanchin M., Campone M., Quereux G., Dravet F., Sebille V., Bonnaud Antignac A. A comparison of posttraumatic growth changes in breast cancer and melanoma. Health Psychol. Off. J. Div. Health Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2019;38:878–887. doi: 10.1037/hea0000766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bui Q.U., Ostir G.V., Kuo Y.F., Freeman J., Goodwin J.S. Relationship of depression to patient satisfaction: Findings from the barriers to breast cancer study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2005;89:23–28. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-1005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blodt S., Kaiser M., Adam Y., Adami S., Schultze M., Muller-Nordhorn J., Holmberg C. Understanding the role of health information in patients’ experiences: Secondary analysis of qualitative narrative interviews with people diagnosed with cancer in Germany. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019576. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang C.K., Chang M.C., Chen P.J., Lin C.C., Chen G.S., Lin J., Hsieh R.K., Chang Y.F., Chen H.W., Wu C.L., et al. A correlational study of suicidal ideation with psychological distress, depression, and demoralization in patients with cancer. Support. Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Support. Care Cancer. 2014;22:3165–3174. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2290-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirk D., Kabdebo I., Whitehead L. Prevalence of distress, its associated factors and referral to support services in people with cancer. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021;30:2873–2885. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang L., Li Z., Pang Y. The differences and the relationship between demoralization and depression in Chinese cancer patients. Psycho-Oncol. 2020;29:532–538. doi: 10.1002/pon.5296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bovero A., Botto R., Adriano B., Opezzo M., Tesio V., Torta R. Exploring demoralization in end-of-life cancer patients: Prevalence, latent dimensions, and associations with other psychosocial variables. Palliat. Support. Care. 2019;17:596–603. doi: 10.1017/S1478951519000191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vehling S., Kissane D.W., Lo C., Glaesmer H., Hartung T.J., Rodin G., Mehnert A. The association of demoralization with mental disorders and suicidal ideation in patients with cancer. Cancer. 2017;123:3394–3401. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robinson S., Kissane D.W., Brooker J., Burney S. A systematic review of the demoralization syndrome in individuals with progressive disease and cancer: A decade of research. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2015;49:595–610. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Figueiredo J.M. Depression and demoralization: Phenomenologic differences and research perspectives. Compr. Psychiatry. 1993;34:308–311. doi: 10.1016/0010-440X(93)90016-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y., Sun H., Ji Q., Wu Q., Wei J., Zhu P. Prevalence, associated factors and adverse outcomes of demoralization in cancer patients: A decade of systematic review. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2023;40:1216–1230. doi: 10.1177/10499091231154887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woźniewicz A., Cosci F. Clinical utility of demoralization: A systematic review of the literature. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2023;99:102227. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehnert A., Vehling S., Höcker A., Lehmann C., Koch U. Demoralization and depression in patients with advanced cancer: Validation of the German version of the demoralization scale. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2011;42:768–776. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee C.Y., Fang C.K., Yang Y.C., Liu C.L., Leu Y.S., Wang T.E., Chang Y.F., Hsieh R.K., Chen Y.J., Tsai L.Y., et al. Demoralization syndrome among cancer outpatients in Taiwan. Support. Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Support. Care Cancer. 2012;20:2259–2267. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.NCCN Distress Management. [(accessed on 22 March 2024)]. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/distress.pdf.

- 24.Irwin D.E., Gross H.E., Stucky B.D., Thissen D., DeWitt E.M., Lai J.S., Amtmann D., Khastou L., Varni J.W., DeWalt D.A. Development of six PROMIS pediatrics proxy-report item banks. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2012;10:22. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang G.-L., Cheng C.-T., Feng A.-C., Hsu S.-H., Hou Y.-C., Chiu C.-Y. Prevalence, risk factors, and the desire for help of distressed newly diagnosed cancer patients: A large-sample study. Palliat. Support. Care. 2017;15:295–304. doi: 10.1017/S1478951516000717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thapa S., Sun H., Pokhrel G., Wang B., Dahal S., Yu S. Performance of distress thermometer and associated factors of psychological distress among chinese cancer patients. J. Oncol. 2020;2020:3293589. doi: 10.1155/2020/3293589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlson L.E., Zelinski E.L., Toivonen K.I., Sundstrom L., Jobin C.T., Damaskos P., Zebrack B. Prevalence of psychosocial distress in cancer patients across 55 North American cancer centers. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2019;37:5–21. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2018.1521490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan J.Y., Molassiotis A., Lloyd-Williams M., Yorke J. Burden, emotional distress and quality of life among informal caregivers of lung cancer patients: An exploratory study. Eur. J. Cancer Care. 2018;27:e12691. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McFarland D.C., Shaffer K.M., Tiersten A., Holland J. Physical symptom burden and its association with distress, anxiety, and depression in breast cancer. Psychosomatics. 2018;59:464–471. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berkowitz B. The patient experience and patient satisfaction: Measurement of a complex dynamic. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2016;21:E1–E8. doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol21No01Man01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Beryl Institute Defining Patient and Human Experience. [(accessed on 6 April 2024)]. Available online: https://theberylinstitute.org/defining-patient-experience/

- 32.Oben P. Understanding the patient experience: A conceptual framework. J. Patient Exp. 2020;7:906–910. doi: 10.1177/2374373520951672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality What Is Patient Experience? [(accessed on 6 April 2024)]; Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/about-cahps/patient-experience/index.html.

- 34.Kavalnienė R., Deksnyte A., Kasiulevičius V., Šapoka V., Aranauskas R., Aranauskas L. Patient satisfaction with primary healthcare services: Are there any links with patients’ symptoms of anxiety and depression? BMC Fam. Pract. 2018;19:90. doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0780-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lam W.W.T., Kwong A., Suen D., Tsang J., Soong I., Yau T.K., Yeo W., Suen J., Ho W.M., Wong K.Y., et al. Factors predicting patient satisfaction in women with advanced breast cancer: A prospective study. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:162. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4085-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chien T.-W., Wang W.-C., Chien C.-C., Hwang W.-S. Rasch analysis of positive changes following adversity in cancer patients attending community support groups. Psycho-Oncol. 2011;20:98–105. doi: 10.1002/pon.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zang Y., Hunt N.C., Cox T., Joseph S. Short form of the changes in outlook questionnaire: Translation and validation of the Chinese version. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2012;10:41. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henry M., Fuehrmann F., Hier M., Zeitouni A., Kost K., Richardson K., Mlynarek A., Black M., MacDonald C., Chartier G., et al. Contextual and historical factors for increased levels of anxiety and depression in patients with head and neck cancer: A prospective longitudinal study. Head Neck. 2019;41:2538–2548. doi: 10.1002/hed.25725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kessler R.C., Wang P.S. The descriptive epidemiology of commonly occurring mental disorders in the United States. Annu. Rev. Public. Health. 2008;29:115–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maass S.W., Roorda C., Berendsen A.J., Verhaak P.F., de Bock G.H. The prevalence of long-term symptoms of depression and anxiety after breast cancer treatment: A systematic review. Maturitas. 2015;82:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naser A.Y., Hameed A.N., Mustafa N., Alwafi H., Dahmash E.Z., Alyami H.S., Khalil H. Depression and anxiety in patients with cancer: A cross-sectional study. Front. Psychol. 2021;12:1067. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.585534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fang C.-K., Chiu Y.-J., Yeh P.-C., Pi S.-H., Li Y.-C. Association among depression, demoralization, and posttraumatic growth in cancer patient: Preliminary study. Asia-Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;8:228–229. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin C.C., Her Y.N. Demoralization in cancer survivors: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis for quantitative studies. Psychogeriatrics. 2024;24:35–45. doi: 10.1111/psyg.13037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hung H.C., Chen H.W., Chang Y.F., Yang Y.C., Liu C.L., Hsieh R.K., Leu Y.S., Chen Y.J., Wang T.E., Tsai L.Y., et al. Evaluation of the reliability and validity of the mandarin version of demoralization scale for cancer patients. J. Intern. Med. Taiwan. 2010;21:427–435. doi: 10.6314/JIMT.2010.21(6).06. (Original work published in traditional Chinese) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guimond A.J., Ivers H., Savard J. Clusters of psychological symptoms in breast cancer: Is there a common psychological mechanism? Cancer Nurs. 2019;43:343–353. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith H.R. Depression in cancer patients: Pathogenesis, implications and treatment (Review) Oncol. Lett. 2015;9:1509–1514. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.2944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chiou Y.J., Lee C.Y., Li S.H., Chong M.Y., Lee Y., Wang L.J. Screening for psychologic distress in taiwanese cancer inpatients using the national comprehensive cancer network distress thermometer: The effects of patients’ sex and chemotherapy experience. Psychosomatics. 2017;58:496–505. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang G.L., Hsu S.H., Feng A.C., Chiu C.Y., Shen J.F., Lin Y.J., Cheng C.C. The HADS and the DT for screening psychosocial distress of cancer patients in Taiwan. Psycho-Oncol. 2011;20:639–646. doi: 10.1002/pon.1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kissane D.W., Wein S., Love A., Lee X.Q., Kee P.L., Clarke D.M. The demoralization scale: A report of its development and preliminary validation. J. Palliat. Care. 2004;20:269–276. doi: 10.1177/082585970402000402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen P.Y., See L.C., Wang C.H., Lai Y.H., Chang H.K., Chen M.L. The impact of pain on the anxiety and depression of cancer patients. Formos. J. Med. 1999;3:373–382. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zigmond A.S., Snaith R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McMillen J.C., Fisher R.H. The perceived benefit scales: Measuring perceived positive life changes after negative events. Soc. Work Res. 1998;22:173–186. doi: 10.1093/swr/22.3.173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang S.W. Master’s Thesis. Fu-Jen Catholic University; New Taipei, Taiwan: 2002. Research of the Perceived Benefits and Related Factors with Breast Cancer Patients. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Glasgow R.E., Wagner E.H., Schaefer J., Mahoney L.D., Reid R.J., Greene S.M. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) Med. Care. 2005;43:436–444. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000160375.47920.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu W.-Z., Wang H.-F., Lin Y.-K., Liu Y.-L., Yen Y., Whang-Peng J., Huang T.-W., Chang H.-J. The effect of oncology nurse navigation on mental health in patients with cancer in Taiwan: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Curr. Oncol. 2024;31:4105–4122. doi: 10.3390/curroncol31070306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bursac Z., Gauss C.H., Williams D.K., Hosmer D.W. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol. Med. 2008;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cancer Research UK What do Cancer Stages and Grades Mean? [(accessed on 13 May 2024)]. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/common-health-questions/operations-tests-and-procedures/what-do-cancer-stages-and-grades-mean/

- 58.Gress D.M., Edge S.B., Greene F.L., Washington M.K., Asare E.A., Brierley J.D., Byrd D.R., Compton C.C., Jessup J.M., Winchester D.P. Principles of cancer staging. AJCC Cancer Staging Man. 2017;8:3–30. [Google Scholar]

- 59.O’Connor M., Butcher I., Hansen C.H., Kleiboer A., Murray G., Sharma N., Thekkumpurath P., Walker J., Sharpe M. Measuring improvement in depression in cancer patients: A 50% drop on the self-rated SCL-20 compared with a diagnostic interview. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2010;32:334–336. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Niedzwiedz C.L., Knifton L., Robb K.A., Katikireddi S.V., Smith D.J. Depression and anxiety among people living with and beyond cancer: A growing clinical and research priority. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:943. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6181-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang S.-Y., Chen C.-H., Chen Y.-S., Huang H.-L. The attitude toward truth telling of cancer in Taiwan. J. Psychosom. Res. 2004;57:53–58. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00566-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blackhall L.J., Murphy S.T., Frank G., Michel V., Azen S. Ethnicity and attitudes toward patient autonomy. Jama. 1995;274:820–825. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530100060035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bailey R.K., Geyen D.J., Scott-Gurnell K., Hipolito M.M., Bailey T.A., Beal J.M. Understanding and treating depression among cancer patients. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer Off. J. Int. Gynecol. Cancer Soc. 2005;15:203–208. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-00009577-200503000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goerling U., Hinz A., Koch-Gromus U., Hufeld J.M., Esser P., Mehnert-Theuerkauf A. Prevalence and severity of anxiety in cancer patients: Results from a multi-center cohort study in Germany. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023;149:6371–6379. doi: 10.1007/s00432-023-04600-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hashemi S.-M., Rafiemanesh H., Aghamohammadi T., Badakhsh M., Amirshahi M., Sari M., Behnamfar N., Roudini K. Prevalence of anxiety among breast cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer. 2020;27:166–178. doi: 10.1007/s12282-019-01031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Su J.-A., Yeh D.-C., Chang C.-C., Lin T.-C., Lai C.-H., Hu P.-Y., Ho Y.-F., Chen V.C.-H., Wang T.-N., Gossop M. Depression and family support in breast cancer patients. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2017;13:2389–2396. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S135624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Petrova D., Redondo-Sánchez D., Rodríguez-Barranco M., Romero Ruiz A., Catena A., Garcia-Retamero R., Sánchez M.J. Physical comorbidities as a marker for high risk of psychological distress in cancer patients. Psycho-Oncol. 2021;30:1160–1166. doi: 10.1002/pon.5632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Petrova D., Catena A., Rodríguez-Barranco M., Redondo-Sánchez D., Bayo-Lozano E., Garcia-Retamero R., Jiménez-Moleón J.-J., Sánchez M.-J. Physical comorbidities and depression in recent and long-term adult cancer survivors: NHANES 2007–2018. Cancers. 2021;13:3368. doi: 10.3390/cancers13133368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yan R., Xia J., Yang R., Lv B., Wu P., Chen W., Zhang Y., Lu X., Che B., Wang J. Association between anxiety, depression, and comorbid chronic diseases among cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncol. 2019;28:1269–1277. doi: 10.1002/pon.5078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Isik K., Cengiz Z., Doğan Z. The relationship between self-care agency and depression in older adults and influencing factors. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2020;58:39–47. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20200817-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Luciani A., Jacobsen P.B., Extermann M., Foa P., Marussi D., Overcash J.A., Balducci L. Fatigue and functional dependence in older cancer patients. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;31:424–430. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e31816d915f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mu T.-Y., Xu R.-X., Xu J.-Y., Dong D., Zhou Z.-N., Dai J.-N., Shen C.-Z. Association between self-care disability and depressive symptoms among middle-aged and elderly Chinese people. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0266950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0266950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Godfrey C.M., Harrison M.B., Lysaght R., Lamb M., Graham I.D., Oakley P. Care of self-care by other-care of other: The meaning of self-care from research, practice, policy and industry perspectives. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2011;9:3–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2010.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Koyuncu N.E., Su S. Investigation of the relationship between care dependency and self-care behaviors in chemotherapy patients. Cyprus J. Med. Sci. 2023;8:372–377. doi: 10.4274/cjms.2021.3530. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sadeghpour F., Heidarzadeh M., Kohi F., Asadi R., Aghamohammadi-Kalkhoran M., Abbasi F. The relationship between “self-care ability” and psychological changes among hemodialysis patients. Indian. J. Palliat. Care. 2020;26:276. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_129_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Puigpinós-Riera R., Graells-Sans A., Serral G., Continente X., Bargalló X., Doménech M., Espinosa-Bravo M., Grau J., Macià F., Manzanera R. Anxiety and depression in women with breast cancer: Social and clinical determinants and influence of the social network and social support (DAMA cohort) Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;55:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chien C., Chuang C., Liu K., Wu C., Pang S., Tsay P., Chang Y., Huang X., Liu H. Effects of individual and partner factors on anxiety and depression in Taiwanese prostate cancer patients: A longitudinal study. Eur. J. Cancer Care. 2018;27:e12753. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chochinov H.M. Depression in cancer patients. Lancet. Oncol. 2001;2:499–505. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00456-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lee A.R.Y.B., Leong I., Lau G., Tan A.W., Ho R.C.M., Ho C.S.H., Chen M.Z. Depression and anxiety in older adults with cancer: Systematic review and meta-summary of risk, protective and exacerbating factors. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2023;81:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2023.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nelson C.J., Weinberger M.I., Balk E., Holland J., Breitbart W., Roth A.J. The chronology of distress, anxiety, and depression in older prostate cancer patients. Oncologist. 2009;14:891–899. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Domènech-Abella J., Mundó J., Haro J.M., Rubio-Valera M. Anxiety, depression, loneliness and social network in the elderly: Longitudinal associations from The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA) J. Affect. Disord. 2019;246:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fluharty M., Taylor A.E., Grabski M., Munafò M.R. The association of cigarette smoking with depression and anxiety: A systematic review. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2016;19:3–13. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Choi K.-H., Park S.M. Psychological status and associated factors among Korean cancer survivors: A cross-sectional analysis of the fourth & fifth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2016;31:1105–1113. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.7.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Civilotti C., Botto R., Maran D.A., Leonardis B.D., Bianciotto B., Stanizzo M.R. Anxiety and depression in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer and waiting for surgery: Prevalence and associations with socio-demographic variables. Medicina. 2021;57:454. doi: 10.3390/medicina57050454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Goudarzian A.H., Bagheri Nesami M., Zamani F., Nasiri A., Beik S. Relationship between depression and self-care in iranian patients with cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2017;18:101–106. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Huda N., Yun-Yen, Deli H., Shaw M.K., Huang T.-W., Chang H.-J. Mediation of coping strategies among patients with advanced cancer. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2021;30:1153–1163. doi: 10.1177/10547738211003276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ng C.G., Mohamed S., Kaur K., Sulaiman A.H., Zainal N.Z., Taib N.A., MyBCC Study group Perceived distress and its association with depression and anxiety in breast cancer patients. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0172975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Boyes A.W., Girgis A., D’Este C., Zucca A.C. Flourishing or floundering? Prevalence and correlates of anxiety and depression among a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors 6months after diagnosis. J. Affect. Disord. 2011;135:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen S.C., Huang B.S., Lin C.Y. Depression and predictors in Taiwanese survivors with oral cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013;14:4571–4576. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.8.4571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yu-Yueh T. The body experience of Taiwanese cancer patients: Illness, death, and the power of the medical profession. Taiwan. J. Sociol. 2004;33:51–108. (Original work published in traditional Chinese) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data from our study are unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.