Abstract

Trans-Himalayan hot spring waters rich in boron, chlorine, sodium and sulfur (but poor in calcium and silicon) are known based on PCR-amplified 16S rRNA gene sequence data to harbor high diversities of infiltrating bacterial mesophiles. Yet, little is known about the community structure and functions, primary productivity, mutual interactions, and thermal adaptations of the microorganisms present in the steaming waters discharged by these geochemically peculiar spring systems. We revealed these aspects of a bacteria-dominated microbiome (microbial cell density ~8.5 × 104 mL-1; live:dead cell ratio 1.7) thriving in the boiling (85°C) fluid vented by a sulfur-borax spring called Lotus Pond, situated at 4436 m above the mean sea-level, in the Puga valley of eastern Ladakh, on the Changthang plateau. Assembly, annotation, and population-binning of >15-GB metagenomic sequence illuminated the numeral predominance of Aquificae. While members of this phylum accounted for 80% of all 16S rRNA-encoding reads within the metagenomic dataset, 14% of such reads were attributed to Proteobacteria. Post assembly, only 25% of all protein-coding genes identified were attributable to Aquificae, whereas 41% was ascribed to Proteobacteria. Annotation of metagenomic reads encoding 16S rRNAs, and/or PCR-amplified 16S rRNA genes, identified 163 bacterial genera, out of which 66 had been detected in past investigations of Lotus Pond’s vent-water via 16S amplicon sequencing. Among these 66, Fervidobacterium, Halomonas, Hydrogenobacter, Paracoccus, Sulfurihydrogenibium, Tepidimonas, Thermus and Thiofaba (or their close phylogenomic relatives) were presently detected as metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs). Remarkably, the Hydrogenobacter related MAG alone accounted for ~56% of the entire metagenome, even though only 15 out of the 66 genera consistently present in Lotus Pond’s vent-water have strains growing in the laboratory at >45°C, reflecting the continued existence of the mesophiles in the ecosystem. Furthermore, the metagenome was replete with genes crucial for thermal adaptation in the context of Lotus Pond’s geochemistry and topography. In terms of sequence similarity, a majority of those genes were attributable to phylogenetic relatives of mesophilic bacteria, while functionally they rendered functions such as encoding heat shock proteins, molecular chaperones, and chaperonin complexes; proteins controlling/modulating/inhibiting DNA gyrase; universal stress proteins; methionine sulfoxide reductases; fatty acid desaturases; different toxin-antitoxin systems; enzymes protecting against oxidative damage; proteins conferring flagellar structure/function, chemotaxis, cell adhesion/aggregation, biofilm formation, and quorum sensing. The Lotus Pond Aquificae not only dominated the microbiome numerically but also acted potentially as the main primary producers of the ecosystem, with chemolithotrophic sulfur oxidation (Sox) being the fundamental bioenergetic mechanism, and reductive tricarboxylic acid (rTCA) cycle the predominant carbon fixation pathway. The Lotus Pond metagenome contained several genes directly or indirectly related to virulence functions, biosynthesis of secondary metabolites including antibiotics, antibiotic resistance, and multi-drug efflux pumping. A large proportion of these genes being attributable to Aquificae, and Proteobacteria (very few were ascribed to Archaea), it could be worth exploring in the future whether antibiosis helped the Aquificae overcome niche overlap with other thermophiles (especially those belonging to Archaea), besides exacerbating the bioenergetic costs of thermal endurance for the mesophilic intruders of the ecosystem.

Introduction

Hydrothermal environments, despite being the potential nurseries of early life on Earth [1–3], are characterized by the entropic disordering of biomacromolecular systems, which in turn restricts the habitability of these ecosystems [4,5]. Thermophilic and hyperthermophilic microorganisms [6], that are adept to counter chaos and restore order at the molecular level without incurring untenable energy costs for cell system maintenance, are the habitual natives of hydrothermal vents. For most other taxa abundant at the 30–40°C sites of these ecosystems (these are the phylogenetic relatives of mesophilic microorganisms), habitability is progressively constrained in the 50°C to 100°C trajectory [5,7–10]. Conversely, as the bioenergetic cost of cell system maintenance get relaxed down the temperature gradient, habitability, and therefore in situ diversity, increases for most microbial taxa except for the true thermophiles [11,12].

Idiosyncratic to the low-biodiversity community structure axiomatic for hydrothermal vent ecosystems, a geochemically unusual category of Trans-Himalayan hot springs, located on the either side of the tectonically active Indus Tsangpo Suture Zone (ITSZ, the collision intersection between the Asian and Indian continental crusts engaged in Himalayan orogeny) in eastern Ladakh, India [13–16], has recently been reported for their extra-ordinarily diversified vent-water microflora [5,10,17,18]. Compared with other well studied hydrothermal systems, the geochemical specialty of these Trans-Himalayan hot springs lies in their paucity of dissolved solids in general and calcium and silicon in particular, which again is accompanied by the exceptional abundance of boron, chlorine, sodium, and various sulfur species including both sulfide and sulfate. Concurrent to such reports of highly bio-diverse microbiomes from the hot springs of the Puga valley and Chumathang geothermal areas situated on the Changthang plateau, to the south and north of the ITSZ respectively, studies of microbial diversity within the vent-waters, and vent-adjacent areas, of a number of hot springs located across discrete Himalayan and Trans-Himalayan geothermal regions have corroborated that hydrothermal environments are not “Thermophiles only” territories [19–26].

As for the well-studied Puga hydrothermal system, PCR-amplified 16S rRNA gene sequence-based investigations of microbial communities within the boiling vent-waters of a number of springs have revealed the presence of several such genera whose members are incapable of laboratory-growth at >45°C [10,17,18]. Diurnal fluctuations in the biodiversity and chemistry of the vent-waters, in conjunction with circumstantial geological evidences, have indicated that the copious tectonic faults of this ITSZ-adjoining area serve as potential conduits for the infiltration of meteoric water, and therewith mesophilic microorganisms, to the shallow geothermal reservoir [10]. The phenomenon of mesophilic microorganisms getting introduced to hot spring systems has been reported from other parts of the world too; for instance, systemic infiltration of mesophiles from surface and sub-surface sources of cold water and meteoric fluids have been observed for hot springs of New Zealand and Yellowstone National Park, USA [27,28]. Furthermore, for the Puga hot spring system, shotgun metagenome sequencing-based investigation of microbial mat communities along the spring-water transits and dissipation channels of a microbialite has identified several genus-level populations to occupy such sites within the hydrothermal gradients which have temperatures tens of degree-Celsius above the in vitro growth-limits of those taxa [5,29]. While the overall geomicrobiology of the Puga hot springs have indicated the system’s peculiar chemistry (mineralogy) to be a key facilitator of the high habitability of the environment [5,18], physiological attributes of a vent-water isolate identified dissolved solutes such as lithium and boron, which are characteristic to the Puga hydrothermal system [15,16], as the key enablers of high temperature endurance by the mesophilic bacteria present in situ [30].

Despite a considerable progress in our basic awareness about the peculiar geobiology of Trans-Himalayan sulfur-borax hot springs, we still do not have any quantitative idea about the structural and functional dynamics of the vent-water microbiomes of these astrobiologically significant hydrothermal systems [16,31,32]. For instance, we have a fair measure of the microbial diversity in terms of the variety of taxa present, but we are completely uninformed about the relative abundance and temporal consistency of the individual taxa constituting the microbiome, the thermal adaptations of the native microorganisms (especially the phylogenetic relatives of mesophilic bacteria present), and the mutual interactions of the various components of the microbiome. We also know nothing about the pathways of primary productivity that sustain the ecosystem in these boiling spring waters. To address these shortcomings in our knowledge on the ecology of Trans-Himalayan sulfur–borax spring systems, this study comprehensively reveals the vent-water microbiome of the Lotus Pond hot spring, which is one of the most conspicuous hydrothermal manifestations within the Puga valley [10,16,17]. While the bacterial diversity of Lotus Pond’s vent-water has been investigated previously by means of 16S amplicon sequencing [10,17], the present exploration, for the first time, unraveled the qualitative as well as quantitative architecture of the microbiome via shotgun metagenome sequencing, and fluorescence microscopy. Besides elucidating the dominance and equitability of taxa within the microbiome, the >15 giga base metagenomic sequence data generated was analyzed to illuminate the aforesaid aspects of microbiome functioning. Furthermore, to know whether the Lotus Pond vent-water microbiome remained consistent over time, its bacterial and archaeal diversity was evaluated afresh by amplified 16S rRNA gene sequencing and comparing the current findings with the previous data obtained on the basis of similar analyses.

Materials and methods

Study site and sampling

Lotus Pond, located at 33°13’46.3”N and 78°21’19.7”E, is one of the most prominent hot springs or geysers within the Puga valley (Fig 1A), which in turn is one of the most vigorous geothermal areas of the Indian Trans-Himalayas. Notably, Puga Valley is situated at an altitude of 4436 m, where the boiling point of water remains at around 85°C [10,16,33]. The venting point (Fig 1B) is embedded in a hot water pool that has been formed by its own discharges and lies within the old crater (Fig 1A) which was formed from the same hydrothermal eruption that gave rise to the geyser itself. From one side of the hot water pool, the spring-water flows over thin unstable terraces of geothermal sinters, into the Rulang rivulet, which meanders through the valley of Puga. On the other flank of the hot water pool, a wall of travertine, sulfur, and boron mineral deposits [10,16] guard the crater and debars the spring-water from escaping the pool (Fig 1C).

Fig 1.

Topography of the study site: (A) the Lotus Pond hot spring in the context of the river Rulang and the valley of Puga, (B) the boiling vent-water explored for microbiome structure and function, (C) boratic sinters, and fresh condensates of sulfur and boron minerals covering the broken wall of the old crater within which Lotus Pond is embedded.

Water (having temperature 85°C and pH 7.5) was collected as described at length previously [5,10,17,18] from Lotus Pond’s vent at 13:00 h of 29 October 2021, when ebullition was strong and fumarolic activity copious. For microscopic studies, 500 mL vent-water was passed through a sterile 0.22 μm mixed cellulose ester membrane filter (Merck Life Science Private Limited, India) having a diameter of 47 mm, and inserted into a sterilized cryovial containing 5 mL of autoclaved 0.9% (w/v) NaCl solution supplemented with 15% (v/v) glycerol. Simultaneously, for the extraction of total environmental DNA (metagenome), overall 5 L vent-water was passed through five individual sterile 0.22 μm filters, each of which was inserted into a separate sterilized cryovial containing 5 mL of autoclaved 50 mM Tris:EDTA (pH 7.8). After filter insertion, all the cryovials were sealed with parafilm (Tarsons Products Limited, India), packed in polyethylene bags, put into dry ice, and air lifted to the laboratory at Bose Institute in Kolkata. The entire on-field procedure was carried out aseptically using sterilized syringes (Tarsons Products Limited, India), Swinnex filter holders (Merck KGaA, Germany), and forceps on every occasion of water collection from the vent, filtration through the membrane, and insertion of the filter to the cryovial.

Enumeration of microbial cells

Total microbial cell count per unit volume of vent-water was determined alongside the number of metabolically active and metabolically inactive cells present. The microbial cells that were filtered out from 500 mL vent-water were first detached from the adherence matrix by shredding the filter with sterilized scissors, and then vortexing for 30 min, within the NaCl-glycerol containing cryovial in which the filter was inserted on-field. The vial was spun at 1000 g for 5 seconds to allow the filter shreds to settle down. Finally, the supernatant was collected (without disturbing the bottom debris), its exact volume measured, and then analyzed as described previously [34] using a hemocytometer (Paul Marienfeld GmbH & Co. KG, Germany) and an upright fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX53 Digital, Olympus Corporation, Japan). Microbial cell density measurement was carried out based on the axiom that the final supernatant collected contained all the microbial cells that were present in the 500 mL vent-water filtered on-field. The cell suspension (i.e. the collected supernatant) was stained with 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), fluorescein diacetate (FDA) or propidium iodide (PI) solution, and cell numbers were counted as described previously [35]. Details of the procedure followed for microscopy and microbial cell enumeration have been given in the Supplementary Methods.

Metagenome extraction and sequencing

The 0.22 μm membrane filters suspended in sterile 50 mM Tris:EDTA (pH 7.8) were treated as described previously [5,10,17,18], and from the final cell suspension obtained metagenomic DNA was extracted using PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA molecules having high levels of structural integrity, as evident from NanoDrop spectrophotometry and Qubit fluorometry (both the operations were carried out using platforms manufactured by Thermo Fisher Scientific), were used as the input material (approximately 1 ng total quantity) for preparing shotgun metagenome sequencing library with the help of Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina Inc., USA). Quality of the final library was assesed using high sensitivity D1000 screen tape in 2200 TapeStation (Agilent Technologies Inc., USA), while its quantification was carried out using a Qubit fluorometer. Paired end (2 × 250 nucleotides) sequencing of the library was performed in a Novaseq 6000 (Illumina Inc.) next-generation DNA sequencer. The whole metagenomic sequence dataset of 31353866 read-pairs obtained in the process was submitted to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), USA, under the BioProject PRJNA296849.

In tandem with the aforesaid procedure, potential traces of contaminating microial DNA, often referred to as the “kitome” [36,37], was isolated in the same way as described above for the five membrane filters through which vent-water was passed on-field. The only difference in case of the kitome preparation was that no vent-water was passed through any of the five filters, which in this case also were inserted to five individual sterilized cryovials each containing 5 mL of autoclaved 50 mM Tris:EDTA (pH 7.8). The final suspension obtained for the blank filters was subjected to the same DNA extraction procedure using the same PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit as it was done for the actual sample suspension. No DNA could be detected using NanoDrop spectrophotometry or Qubit fluorometry, so the so-called kitome DNA preparation could not be subjected to shotgun sequencing on the Illumina platform.

Assembly and annotation of the metagenomic sequence

Clipping of adapters and quality-filtering of the trimmed sequences (for average Phred score ≥20) were carried out using Trim Galore v0.6.4 (https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore) with default parameters. The 31342225 processed read-pairs obtained post quality filtering were subjected to de novo assembly by Megahit v1.2.9 using default parameters [38]. Open reading frames (ORFs) or genes were identified within the assembled contigs using Prodigal v2.6.3 with default parameters [39]. Annotation of the predicted ORFs into protein coding sequences (CDSs) was carried out by searching against the eggNOG database v5.0 [40] using eggNOG-mapper v2.1.9 in default mode using Diamond algorithm [41]. The software eggNOG-mapper aligns CDSs to precomputed orthology assignments in the eggNOG database in such a way that it can infer orthologs, and transfer the functional annotations and taxonomic information obtained to the queries, thereby providing detailed taxonomic annotations for the individual metagenomic CDSs analyzed [41]. Notably, CDS annotated in this way included potential pseudogenes, which could also be outcomes of sequencing error-induced frame shifts. The eggNOG-derived data was processed to assign orthology identities, and determine pathway affiliations, for the annotated CDSs with the help of the information available in the literature in tandem with those provided in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG; https://www.genome.jp/kegg/). Furthermore, to identify the clusters of orthologous genes (COGs) to which the different ORFs predicted within the assembled metagenome belonged, the translated form of the Prodigal-derived gene catalog was annotated by searching against the COG Little Endian version of the Conserved Domain Database of NCBI located at https://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/pub/mmdb/cdd/little_endian/Cog_LE.tar.gz, using COGclassifier v1.0.5 [42]. The bacterial version v7.0 of the antibiotics & Secondary Metabolite Analysis Shell (antiSMASH) pipeline was used in strict detection mode [43,44] to identify gene clusters for secondary metabolites biosynthesis within the assembled metagenome of Lotus Pond. To identify antibiotic resistance genes, the assembled metagenome was searched against the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) v3.2.8 using the software Resistance Gene Identifier v6.0.3 with default parameters [45]. Here, gatifloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, nalidixic acid, norfloxacin, sparfloxacin, and ciprofloxacin antibiotics were grouped as fluoroquinolones; cloxacillin and oxacillin were grouped under beta-Lactam antibiotics.

Direct annotation of metagenomic reads corresponding to rRNA gene sequences

The 62684450 quality-filtered reads available for the Lotus Pond metagenome were searched against the rrnDB database v5.8 [46] using Bowtie2 v2.2.5 [47] in “—end-to-end” mode to extract sequences matching prokaryotic 16S rRNA genes. The aligned FASTQ file was converted to FASTA format and used for sequence annotation with the help of RDP Classifier located at http://https://rrndb.umms.med.umich.edu/estimate/. While 82756 aligned reads were extracted from Lotus Pond’s metagenomic sequence dataset via mapping against rrnDB, their eventual annotation using RDP Classifier with confidence cut-off 0.8 led to the taxonomic classification of 81619 reads.

Construction and taxonomic characterization of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs)

The de novo assembled metagenomic contigs that were ≥2500 nucleotides in length were first binned into putative population genomes or MAGs, via three separate procedures using three different softwares with default parameters: Metabat2 v2.12.1 [48], MaxBin2 v2.2.4 [49], and CONCOCT v1.1.0 [50]. Best quality MAGs were then selected using DASTool v1.1.6 [51] with default parameters from the outputs of the three different binning procedures. The MAGs selected were checked for their completeness and contamination level with the help of CheckM v1.2.2 by searching against collocated sets of marker genes that are ubiquitous and single-copy within a given phylogenetic lineage [52].

Taxonomic identity of the selected MAGs was first predicted independently via searches for genom-genome relatedness conducted using Genome Taxonomy Database Toolkit (GTDB-Tk) v1.7.0 [53], Rapid Annotations using Subsystems Technology (RAST) [54], and Type Strain Genome Server (TYGS) in default mode [55]. As and when required, MAG versus genome/MAG pairs were tested for the extent of their in silico or digital DNA-DNA hybridization (dDDH) using the online software Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC) v3.0 [55]. In TYGS as well as GGDC analyses, total length of all high-scoring segment pairs (HSPs) divided by the total genome length (TGL) of the query MAG was considered as the dDDH value. Taxonomic classifications inferred using the aforesaid index, i.e. “(total HSP length) / (TGL)”, were further corroborated by testing for the index “(total identities found in HSPs) / (total HSP length)”. Notably, these two indices are also known as TYGS formula d0 / GGDC formula 1, and TYGS formula d4 / GGDC formula 2, respectively. Orthologous genes-based average nucleotide identity (ANI) between a pair of MAG and genome/MAG was calculated using ChunLab’s online ANI Calculator [56].

The MAG sequences were deposited to the GenBank and annotated for their gene contents using the Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/annotation_prok/) of the NCBI, USA. Phylogeny of bacterial MAGs, in relation to their closest genomic relatives, was reconstructed based on conserved marker gene sequences, using the Up-to-date Bacterial Core Gene Pipeline v3.0 [57] with default parameter. The dataset used for this purpose contained all the close genomic relatives of the individual MAGs that were indicated by GTDB-Tk and TYGS analyses. The best fit nucleotide substitution model was selected using ModelTest-NG v0.1.7 [58], following which a maximum likelihood tree was generated using RAxML v8.2.12 [59] with 10,000 bootstrap experiments. The software utility called Interactive Tree of Life v6.7.5 [60] was used to visualize the phylogram graphically. The KEGG automatic annotation server (KAAS) was used for ortholog assignment and pathway mapping for the CDSs identified within the MAGs [61]. Relative abundance of the individual MAGs within the metagenome was determined by mapping all quality-filtered metagenomic read-pairs available onto the individual MAG sequences via independent in silico experiments carried out using Bowtie2 v2.2.5 [47] in “—end-to-end” mode.

PCR-amplified 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis

PCR-amplified 16S rRNA gene sequence-based taxonomic diversity was revealed using the fusion primer protocol [10,17,22] on the Ion S5 DNA sequencing platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific), which in turn involved PCR amplification, sequencing, and analysis of the V3 regions of all Bacteria-specific 16S rRNA genes and V4-V5 regions of all Archaea-specific 16S rRNA genes [18] present in the Lotus Pond metagenome. The forward primer 5′ -CCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG- 3′ and the reverse primer 5’ -ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG- 3′ were used to amplify the bacterial V3 regions, while the archaeal V4-V5 regions were amplified using the forward and reverse primers 5′ -GCYTAAAGSRICCGTAGC- 3′ and 5′ -TTTCAGYCTTGCGRCCGTAC- 3′ respectively [18]. Albeit no quantifiable DNA was present in the so-called kitome preparation, it was still subjected to individual PCRs using the two 16S rRNA gene sequence primer-pairs mentioned above. Notably, no DNA could be detected even after re-PCR with any of the two primer-pairs used, so the null PCR products were not subjected to sequencing on the Ion S5 platform.

Reads present in an amplicon sequence dataset (725025 and 589009 reads were there in the bacterial and archaeal sets respectively) were trimmed for their adapters, filtered for average Phred score ≥20 and length >100 nucleotides, and then clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs), i.e. species-level entities united by ≥97% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarities, by USEARCH v10.0.259 [62]. While singleton sequences were eliminated before clustering, OTUs generated for a given dataset were classified taxonomically based on their consensus sequences using the RDP Classifier with confidence cut-off 0.8. Rarefaction curves (S1 Fig in S1 File) were generated via USEARCH v10.0.259.

Results

Density of microbial cells in Lotus Pond

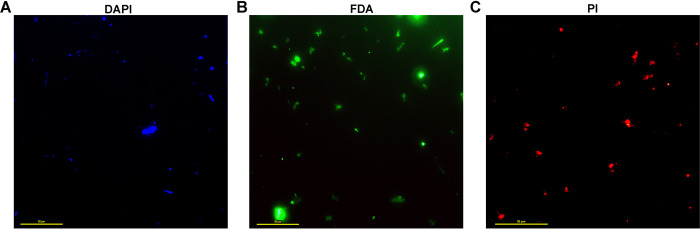

Gross density of microbial cells in the vent-water of Lotus Pond was found to be approximately 8.5 × 104 mL-1, via staining with DAPI, followed by hemocytometry using an upright fluorescence microscope (Fig 2). Using similar instrumentation, the density of metabolically active cells was estimated to be approximately 5.4 × 104 mL-1, via staining with FDA, while that of apparently dead cells was found to be 3.2 × 104 mL-1, via PI staining. Thus, the ratio between the densities of metabolically active and dead cells in Lotus Pond’s vent water was almost 1.7.

Fig 2.

Representative picture of the fluorescence microscopic fields based on which microbial cell density was calculated in the vent-water sample of Lotus Pond: (A) sample stained with DAPI, (B) sample stained with FDA, (C) sample stained with PI. Scale bars in all the three micrographs indicate 50 μm length.

Microbiome composition reconstructed from the assembled metagenome

Quality filtration of the native metagenomic sequence dataset having 31353866 read-pairs resulted in the retention of 31342225 read-pairs (S1 Table in S1 File). Assembly of the quality-filtered dataset yielded 286918 contigs having a minimum and an average length of 200 and 563 nucleotides respectively (96% of all quality-filtered reads participated in the assembly, at an average coverage of ~85X). While the largest contig obtained was 197270-nucleotide long, the consensus sequence of the assembled metagenome was ~162 million nucleotides, with a total of 379412, complete or partial, ORFs or genes identified therein. Out of the 379412 ORFs identified, 220687 could be annotated as CDSs, of which again 220635 could be ascribed to potential taxonomic sources (S2 Table in S1 File). Approximately 97.3%, 1%, 1.5% and 0.2% of the taxonomically classifiable CDSs, i.e. 214652, 2309, 3276 and 398 CDSs, belonged to Bacteria, Archaea, Eukarya and Viruses respectively (S2 and S3 Tables in S1 File).

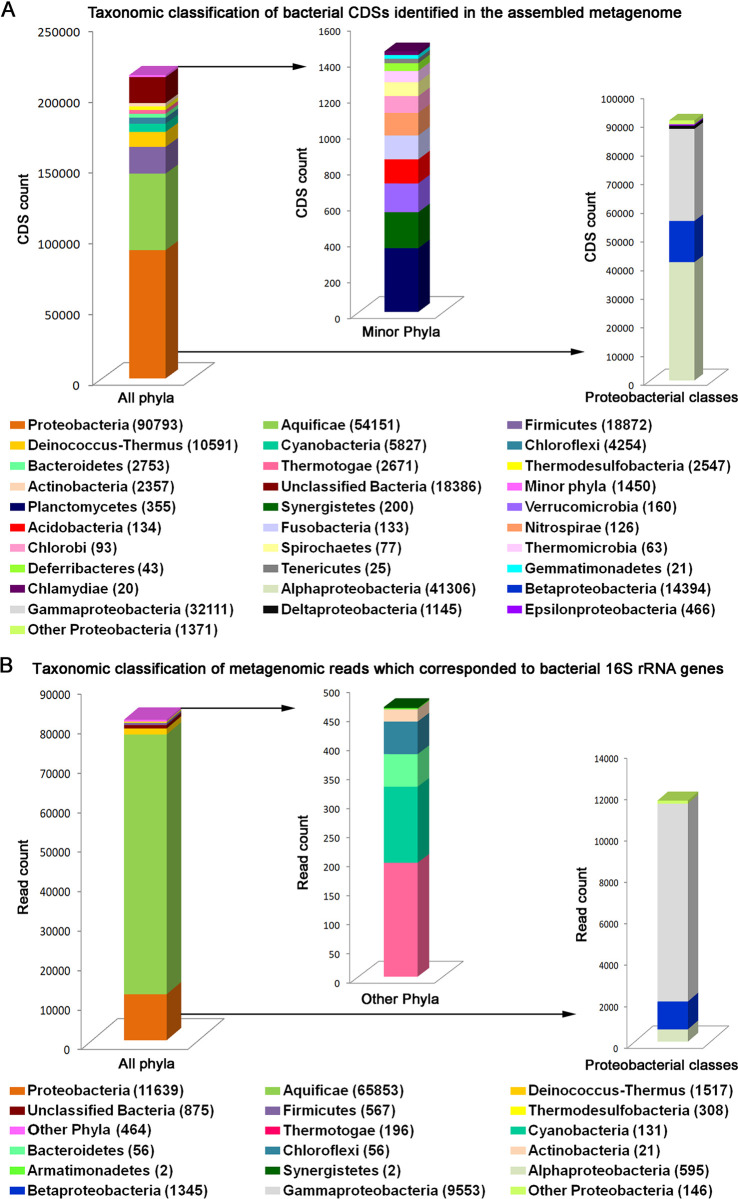

The 214652 bacterial CDSs identified were found to be distributed over 23 phyla, with most CDSs being affiliated to Proteobacteria / Pseudomonadota (90793), followed by Aquificae / Aquificota (54151), Firmicutes / Bacillota (18670), Deinococcus-Thermus / Deinococcota (10591), Cyanobacteria (5827), Chloroflexi / Chloroflexota (4254), Bacteroidetes / Bacteroidota (2753), Thermotogae / Thermotogota (2671), Thermodesulfobacteria / Thermodesulfobacteriota (2547), Actinobacteria / Actinomycetota (2357). Unclassified Bacteria accounted for 18386 CDSs, while 13 other (minor) phyla, namely Planctomycetes / Planctomycetota (355), Synergistetes / Synergistota (200), Verrucomicrobia / Verrucomicrobiota (160), Acidobacteria / Acidobacteriota (134), Fusobacteria / Fusobacteriota (133), Nitrospirae / Nitrospirota (126), Chlorobi / Chlorobiota (93), Spirochaetes / Spirochaetota (77), Thermomicrobia / Thermomicrobiota (63), Deferribacteres / Deferribacterota (43), Tenericutes / Mycoplasmatota (25), Gemmatimonadetes / Gemmatimonadota (21) and Chlamydiae / Chlamydiota (20) were represented sparsely in the CDS catalog (S2 and S3 Tables in S1 File; Fig 3A).

Fig 3.

Taxonomic distribution of (A) the CDSs identified in the assembled metagenome of Lotus Pond, and (B) the metagenomic reads which corresponded to 16S rRNA genes (actual CDS count or metagenomic read count recorded for each taxon is given in parenthesis). In (A) “minor phyla” included the following: Acidobacteria, Chlamydiae, Chlorobi, Deferribacteres, Fusobacteria, Gemmatimonadetes, Nitrospirae, Planctomycetes, Spirochaetes, Synergistetes, Tenericutes, Thermomicrobia and Verrucomicrobia. In (B) “other phyla”, also marginal in representation, included the following: Cyanobacteria, Thermotogae, Bacteroidetes, Chloroflexi, Actinobacteria, Armatimonadetes and Synergistetes.

Among the different classes of Proteobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, followed by Gammaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, Deltaproteobacteria and Epsilonproteobacteria accounted for most CDSs in the assembled metagenome (41306, 31865, 14394, 1145 and 466 CDSs respectively). The other proteobacterial classes Hydrogenophilia, Acidithiobacillia and Oligoflexia were represented by 118, 106 and 101 CDSs respectively, while unclassified Proteobacteria accounted for 1046 CDSs (Fig 3A). Furthermore, within the proteobacterial CDS catalog, the Xanthomonadales-Lysobacterales complex, Vibrionales, Oceanospirillales (all three belonged to the Gammaproteobacteria), and Rhodocyclales (belonging to Betaproteobacteria) were the maximally represented orders, with 10039, 6025, 3,940 and 3582 CDSs affiliated to them respectively (S2 and S3 Tables in S1 File).

The small archaeal genetic diversity was contributed by Crenarchaeota / Thermoproteota, followed by Euryarchaeota (1479 and 647 CDSs respectively); unclassified Archaea accounted for 183 CDSs (S2 and S3 Tables in S1 File). While the Crenarchaeota related CDSs were not classifiable further, the Euryarchaeota-affiliated CDSs were distributed over the classes Halobacteria (177), Thermococci (169), Archaeoglobi (83), Methanococci (60), Methanomicrobia (30), Methanobacteria (19) and Thermoplasmata (9); unclassified Euryarchaeota accounted for 100 CDSs (S2 and S3 Tables in S1 File). Most of the putatively eukaryotic CDSs detected exhibited highest sequence similarities with homologs from Opisthokonta, affiliated to either Fungi or Metazoa (S2 Table in S1 File). The few viral CDSs detected were mostly contributed by Podoviridae, Myoviridae, Siphoviridae and Caudovirales (S2 Table in S1 File).

Genus-level constitution of the microbiome

Taxonomic classification of CDSs predicted within the assembled metagenome was not extended up to the genus level. Instead, generic components of the microbiome were delineated via taxonomic classification of (i) metagenomic reads corresponding to 16S rRNA genes, and (ii) OTUs clustered from PCR-amplified 16S rRNA gene sequences. Additionally, the taxonomic diversity data obtained from the current analysis of PCR-amplified 16S rRNA gene sequences were utilized to evaluate the consistency of the Lotus Pond vent-water microbiome by comparing with equivalent data available from previous explorations of the habitat.

According to the RDP-based classification of the metagenomic reads, out of the 62684450 high quality reads analyzed, 81619 represented parts of prokaryotic 16S rRNA genes: 81223 bacterial and 396 archaeal (S4 Table in S1 File).

Out of the total 81223 metagenomic reads corresponding to bacterial 16S rRNA genes 80348 were classifiable under 12 phyla (the remaining 875 reads belonged to unclassified Bacteria), of which Aquificae accounted for an overwhelming majority (65853) of reads (S4 Table in S1 File; Fig 3B). Substantive number of reads were also ascribable to Proteobacteria (11639), Deinococcus-Thermus (1517) and Firmicutes (567), while Thermodesulfobacteria (308), Cyanobacteria (131), Thermotogae (196), Bacteroidetes (56), Chloroflexi (56), Actinobacteria (21), Armatimonadetes / Armatimonadota (2), and Synergistetes (2) contributed much fewer reads. The proteobacterial reads, again, were mostly from Gammaproteobacteria (9553), followed by Betaproteobacteria (1345) and Alphaproteobacteria (595). Furthermore, 70729 out of the total 81223 bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequence related reads got ascribed to 92 genera (S4 Table in S1 File) led by Hydrogenobacter (44547), Sulfurihydrogenibium (16371), Halomonas (3075), Vibrio (2549), Thermus (1454), Tepidimonas (965) and Paracoccus (196). Whereas the two Aquificales genera Hydrogenobacter and Sulfurihydrogenibium, affiliated to the families Aquificaceae and Hydrogenothermaceae respectively, accounted for 75.8% of all 16S rRNA gene related reads present in the quality-filtered metagenomic sequence dataset; the other Aquificae members detected, namely Thermocrinis, Venenivibrio, Persephonella and Hydrogenothermus, accounted for only 180, 48, 6 and 2 such reads respectively (S4 Table in S1 File).

As for the 396 reads corresponding to archaeal 16S rRNA genes, all were attributable to the phylum Crenarchaeota and only 9 were classifiable up to the level of the genus, detecting Aeropyrum (6), Stetteria (2) and Pyrobaculum (1) in the process (S4 Table in S1 File).

A corroborative experiment involving PCR amplification, seuencing and analysis of the V3 regions of all Bacteria-specific 16S rRNA genes present in the metagenome extracted from the hot water discharged by Lotus Pond revealed 602 bacterial OTUs that in turn were classifiable under 16 different phyla: Proteobacteria (352), Firmicutes (63), Bacteroidetes (52), Actinobacteria (40), Cyanobacteria (20), Deinococcus-Thermus (16), Thermotogae (8), Aquificae (3), Acidobacteria (2), Armatimonadetes (2), Chloroflexi (2), Spirochaetes / Spirochaetota (2), Thermodesulfobacteria (2), Dictyoglomi / Dictyoglomota (1), Rhodothermota (1) and Synergistetes (1); unclassified Bacteria accounted for 35 OTUs (S5 Table in S1 File). Of the total 602 bacterial OTUs identified, 249 were classifiable upto the level of genus. Overall, 121 genera were identified in that way (S5 Table in S1 File), with maximum number of OTUs getting affiliated to Vibrio (21), followed by Halomonas (16) and Thermus (13).

Concurrent to the above experiment, PCR amplification, seuencing and analysis of the V4-V5 regions of all Archaea-specific 16S rRNA genes present in the Lotus Pond vent-water metagenome were carried out to reveal the in situ archaeal diversity (S5 Table in S1 File). Only 30 OTUs were detected in this way, of which, 10 were ascribable to Crenarchaeota, 6 each belonged to Euryarchaeota and Nitrososphaerota, and 8 were not classifiable below the domain level (S5 Table in S1 File). Furthermore, none of the Crenarchaeota OTUs were classifiable at the genus level, whereas out of the 6 OTUs affiliated to Euryarchaeota, 1 and 3 were classifiable as species of Methanomassiliicoccus and Methanospirillum respectively; all the 6 Nitrososphaerota OTUs were classified as members of Nitrososphaera (S5 Table in S1 File).

Predominant generic entities identified via population genome binning

When all the >2500 nucleotide contigs present in the assembled metagenome were binned using Metabat2, MaxBin2, and CONCOCT via separate in silico experiments, 19, 14 and 30 MAGs were obtained respectively. Refinement and optimization of these 63 population genome bins using DASTool yielded 14 bacterial (Table 1 and S6 Table in S1 File; Fig 4) and one archaeal (Table 1 and S6 Table in S1 File) MAGs for subsequent consideration and analysis. Each of these draft genomes had a contamination level of <5%, except the one designated as LotusPond_MAG_Paracoccus_sp._1. Likewise, most of the short-listed MAGs (9 out of 15) had >90% completeness; two, identified as Paracoccus_sp._2 and Unclassified_Thermodesulfobacteriaceae, had <50% completeness; and four, identified as Paracoccus_sp._1, Fervidobacterium_sp., Thermus_sp. and Unclassified_Bacteria, possessed approximately 51.2%, 70.2%, 70.3% and 81.9% completeness respectively. In terms of consensus sequence length, the population genomes classified as Vibrio metschnikovii and Halomonas sp. were the largest (approximately 3.5 and 3.4 mb respectively) whereas the one classified as a novel member of the family Thermodesulfobacteriaceae was the smallest (approximately 0.4 mb only). Furthermore, when the 31342225 high quality read-pairs used for metagenome assembly were searched against the 15 population genomes, a total of 68.08% read-pairs mapped concordantly on to the MAGs as a whole. Individually, the 15 MAGs accounted for 0.06% to 55.9% of the metagenomic read-pairs analyzed.

Table 1. Key features of the population genome bins (MAGs) constructed from the assembled metagenome of Lotus Pond’s vent-water.

| Name of the population genome bin obtained (genome accession number) |

% of quality-filtered metagenomic read-pairs matching sequences of the MAG concordantly | No. of contigs | Genome size (nucleotides) | G+C content (%) | Completeness (%) |

Contamination (%) |

Number of ORFs (genes) / CDSs detected in the MAG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LotusPond_MAG_Unclassified_Aquificaceae (JARJNB000000000) | 55.92 | 131 | 1489711 | 43.32 | 95.12 | 0.61 | 1754 / 1707 |

| LotusPond_MAG_Sulfurihydrogenibium_azorense (JARJNA000000000) | 3.48 | 47 | 1516769 | 32.77 | 98.98 | 0.00 | 1680 / 1639 |

| LotusPond_MAG_Halomonas_sp. (JARJMQ000000000) | 2.65 | 97 | 3349510 | 60.21 | 99.46 | 0.94 | 3245 / 3176 |

| LotusPond_MAG_Unclassified_Desulfurococcales (JARJMZ000000000) | 1.60 | 37 | 1553981 | 49.38 | 99.63 | 0.00 | 1621 / 1559 |

| LotusPond_MAG_Vibrio_metschnikovii (JARJMP000000000) | 1.54 | 249 | 3487509 | 44.28 | 94.07 | 1.85 | 3222 / 3172 |

| LotusPond_MAG_Thermus_sp. (JARJMW000000000) | 1.01 | 372 | 1887946 | 62.80 | 70.34 | 4.24 | 2206 / 2157 |

| LotusPond_MAG_Tepidimonas_sp. (JARJMT000000000) | 0.46 | 200 | 2150705 | 66.30 | 94.16 | 1.29 | 2200 / 2155 |

| LotusPond_MAG_Thermosynechococcus_sp. (JARJMS000000000) | 0.35 | 104 | 2328058 | 52.52 | 97.05 | 0.12 | 2367 / 2319 |

| LotusPond_MAG_Tepidimonas_taiwanensis (JARJMR000000000) | 0.28 | 245 | 2568138 | 69.51 | 90.53 | 3.56 | 2567 / 2525 |

| LotusPond_MAG_Fervidobacterium_sp. (JARJMY000000000) | 0.24 | 293 | 1525481 | 39.93 | 70.18 | 0.88 | 1639 / 1611 |

| LotusPond_MAG_Paracoccus_sp._1 (JARJMU000000000) | 0.17 | 528 | 2138329 | 62.94 | 51.22 | 15.08 | 2383 / 2345 |

| LotusPond_MAG_Unclassified_Bacteria (JARJMV000000000) | 0.11 | 335 | 2025372 | 61.84 | 81.86 | 0.31 | 2082 / 2039 |

| LotusPond_MAG_Unclassified_Chromatiales (JARJMX000000000) | 0.10 | 214 | 1644354 | 62.57 | 91.04 | 2.01 | 1796 / 1758 |

| LotusPond_MAG_Unclassified_Thermodesulfobacteriaceae (JARJND000000000) | 0.07 | 114 | 439694 | 36.23 | 30.15 | 0.31 | 477 / 467 |

| LotusPond_MAG_Paracoccus_sp._2 (JARJNC000000000) | 0.06 | 284 | 1087115 | 64.14 | 34.31 | 1.10 | 1214 / 1201 |

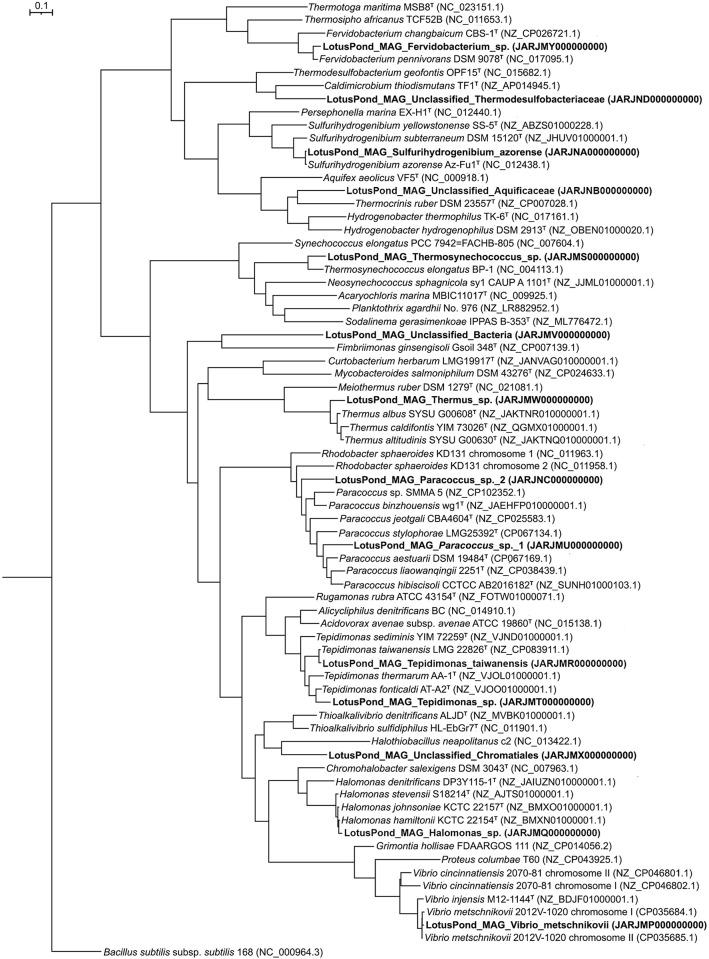

Fig 4. Phylogenetic tree (number of bootstrap tests carried out = 10000) based on 92 universal bacterial core genes that shows the evolutionary relationships among the 14 bacterial MAGs reconstructed from the Lotus Pond vent-water metagenome and their closest relatives identified based on dDDH and/or rRNA gene sequence relationships.

Scale bar denotes a distance equivalent to 10% nucleotide substitution. In the phylogeny reconstructed, nucleotide substitutions were interpreted using the generalized time-reversible model, which considers the proportion of invariable sites and/or the rate of variation across the sites.

The genome bin LotusPond_MAG_Unclassified_Aquificaceae accounted for an overwhelming proportion of the metagenome (55.9% of all read-pairs assembled mapped back to this MAG), while another Aquificales bin identified as Sulfurihydrogenibium azorense, a member of Hydrogenothermaceae, accounted for 3.5% of all read-pairs. Four more bins individually represented ≥1% of the metagenome; these were identifed as (i) an unknown species of the genus Halomonas, (ii) an unclassified member of the order Desulfurococcales within the archaeal class Thermoprotei, (iii) the gammaproteobacteium Vibrio metschnikovii, and (iv) an unknown species of the genus Thermus. These MAGs accounted for 2.7%, 1.6%, 1.5% and 1% of all metagenomic read-pairs respectively. Seven other MAGs, ascribed to Tepidimonas taiwanensis, Tepidimonas sp., Fervidobacterium sp., Thermosynechococcus sp., Paracoccus sp., an unclassified member of the gammaproteobacterial order Chromatiales, and an unclassified taxon of Bacteria, individually accounted for >0.1% but <1% of the metagenome. The remaining two Lotus Pond MAGs individually represented <0.1% of the metagenome; these were identified as one unclassified member each from the family Thermodesulfobacteriaceae of the monotypic phylum Thermodesulfobacteria, and the genus Paracoccus. Details of the phylogenomic relationships, and the consequent basis of taxonomic identification, of the individual MAGs are given in Supplementary Results.

Environmentally advantageous functions encoded by the Lotus Pond MAGs

Apart from house-keeping genes, all the MAGs encompassed genes for heat stress management. Irrespective of their completeness level, MAGs affiliated to thermophilic taxa such as Aquificaceae, Sulfurihydrogenibium, Desulfurococcales, Thermodesulfobacteriaceae and Thermus had less than 10 such genes each. In contrast, almost all the MAGs affiliated to mesophilic taxa had ≥10 heat stress management genes each. Almost all the MAGs contained genes for managing oxidative and periplasmic stress; a half of them had genes for withstanding carbon starvation and nitrosative stress. Eight MAGs encoded genes conferring high frequency of lysogeny as a means of stress response. Every bacterial MAG, but not the archaeal one, encompassed genes for stringent response to environmental stimuli via (p)ppGpp metabolism. Most of the MAGs encoded versatile sporulation-associated proteins, while those affiliated to mesophilic or moderately thermophilic taxa encoded a universal stress protein. Four of the 15 MAGs possessed 12–34 genes for different toxin-antitoxin systems, eight had 1–9 such genes, whereas three (belonging to Aquificaceae, Desulfurococcales and Thermodesulfobacteriaceae) had none. All but one MAG contained genes for cation transport; most had genes for twin-arginine motif-based protein translocation and Ton and Tol transport systems, while some encoded ABC transporters, uni- sym- and antiporters, TRAP transporters, and various secretion systems. Half of the MAGs harbored genes for flagellar motility or chemotaxis; protection against metals, toxins, and antibiotics; and CRISPR systems.

Details of the adaptationally useful genes encompassed by the different MAGs are given in Supplementary Results.

Microbiome functions predicted from the assembled metagenome

Out of the 379412 genes predicted within the assembled Lotus Pond metagenome by Prodigal v2.6.3 212749 were ascribable to COGs that again were distributed across 25 functional categories (S7 Table in S1 File). Of these, Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis; and Energy production and conversion had the maximum number of CDSs ascribed to them (26153 and 22448 respectively). Next in attendance were the COG categories Amino acid transport and metabolism (19711 CDSs); Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis (15685 CDSs); Coenzyme transport and metabolism (14510 CDSs); and Inorganic ion transport and metabolism (11949 CDSs). Notably, the lowest numbers of CDSs, i.e. 26, 23, 21 and 3, were allocated to Extracellular structures; Cytoskeleton; RNA processing and modification; and Chromatin structure and dynamics, respectively. The COG category termed as Nuclear structure had no gene assigned to it at all (S7 Table in S1 File).

For energy production and conversion, maximum homologs were detected for the genes encoding NADH-quinone oxidoreductase and cytochrome c oxidase. While oxidative phosphorylation was the most represented pathway under energy production and conversion, NADH:quinone oxidoreductase, the reductive tricarboxylic acid (rTCA) cycle or the reductive citrate cycle, the TCA or citrate cycle, and cytochrome c oxidase were the biochemical modules with most CDSs (S2 Table in S1 File).

For DNA metabolism, maximum number of homologs was detected for a transposase encoding gene. Mismatch repair, homologous recombination, replication, and nucleotide excision repair were the most represented pathways, while DNA polymerase III complex and fluoroquinolone-resistance gyrase-protecting protein Qnr, were the most represented biochemical modules (S2 Table in S1 File).

For translation and ribosomal structure and biogenesis, maximum homologs were detected for the elongation factor Tu. Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis was the most represented pathway, while ribosome (bacterial followed by archaeal) was the maximally represented biochemical module (S2 Table in S1 File).

Regarding amino acid transport and metabolism, maximum homologs were there for glycine cleavage system protein H and cysteine desulfurase. Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites was the most represented pathway, while maximum CDSs were attributed to the biochemical module photorespiration.

As for cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis, maximum homologs were detected for the transaminase which isomerizes glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate, and the GTP-binding protein LepA, which acts as a potential fidelity factor of translation (for accurate and efficient protein synthesis) under certain stress conditions [63,64]. Under this category, amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism, antibiotics biosynthesis, and peptidoglycan biosynthesis were the most represented pathways. At the module level, nucleotide sugar biosynthesis, dTDP-L-rhamnose biosynthesis, lipoprotein-releasing system, lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis (KDO2-lipid A), and multidrug resistance related efflux pumps AcrAB-TolC/SmeDEF, AcrAD-TolC, MexAB-OprM and AmeABC were maximally represented (S2 Table in S1 File).

For coenzyme transport and metabolism, maximum homologs were detected for uroporphyrin-III C-methyltransferase. Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, porphyrin metabolism, pantothenate and co-enzyme A (CoA) biosynthesis, and antibiotics biosynthesis were the most represented pathways, while heme biosynthesis was the most represented biochemical module (S2 Table in S1 File).

Regarding inorganic ion transport and metabolism, maximum homologs were detected for NADH-quinone oxidoreductase subunit L. Under this category, ABC transporters, oxidative phosphorylation, quorum sensing, and two-component system, were the most represented pathways, wheras at the module level, NADH:quinone oxidoreductase, peptides/nickel transport system, phosphate transport system, iron complex transport system, nickel transport system, NitT/TauT family transport system, nitrate/nitrite transport system, and iron(III) transport system were represented maximally (S2 Table in S1 File).

Chemolithotrophic sulfur oxidation (Sox) is the primary bioenergetic mechanism of the Lotus Pond vent-water ecosystem

Out of all the mechanisms of chemolithotrophy known, only sulfur oxidation (Sox) was found to have substantial numbers of coding sequences, partial or complete, in the assembled metagenome for most of its constituent biochemical reactions (enzymatic steps). Overall, 333 CDSs were there for the different components of the Sox multienzyme complex: 21 for the L-cysteine S-thiosulfotransferase protein SoxX (K17223), 53 for the SoxA subunit of L-cysteine S-thiosulfotransferase (K17222), 112 and 57 for the sulfur compounds chelating/binding protein subunits SoxY (K17226) and SoxZ (K17227) respectively, 79 for the S-sulfosulfanyl-L-cysteine sulfohydrolase SoxB (K17224), and 11 for the sulfane dehydrogenase protein’s molybdopterin-containing subunit SoxC (K17225) and diheme c-type cytochrome subunit SoxD (K22622), the CDSs of which occur universally as overlapping ORFs. In terms of taxonomic distribution, maximum number of Sox protein encoding sequences (~40% of the total 333) was ascribed to Aquificae, followed by Alphaproteobacteria (~25%), Betaproteobacteria (14%), and Deinococcus-Thermus (9%). Unclassified Bacteria, Gammaproteobacteria, and other Proteobacteria individually accounted for approximately 8, 4 and 1 percent of all the Sox CDSs annotated (S2 Table in S1 File).

As for the other forms of chemolithotrophy known in the microbial world, only a small number of CDSs could be detected for the key proteins of arsenite and hydrogen oxidation. Whereas five CDSs each were detected for the small and large subunits AoxA (K08355) and AoxB (K08356) of arsenite oxidase respectively, only a single CDS was identifiable for the small subunit of ferredoxin hydrogenase (K00534), even as no CDS could be detected for the hydrogenase large subunit (K00533). Notably, no CDS was also there for any of the other hydrogenase variants known in the literature.

No CDS was present in the Lotus Pond microbiome for the chemolithotrophic iron oxidation protein iron:rusticyanin reductase (K20150). Likewise, there was also no CDS for the enzymes concerned with the chemolithotrophic oxidation of ammonia to nitrite. However, despite the absence of genes encoding the different subunits of methane/ammonia monooxygenase (pmoABC—K10944, K10945 and K10946), or for that matter the nonexistence of any CDS for the other ammonia-oxidizing enzyme hydroxylamine dehydrogenase (K10535), the Lotus Pond metagenome did encompass several genes for the alpha (K00370) and beta (K00371) subunits of nitrite to nitrate oxidizing enzyme nitrate reductase / nitrite oxidoreductase (269 and 90 CDSs respectively).

So far as the population genome bins are concenrned, the one designated as LotusPond_MAG_Unclassified_Aquificaceae was found to have genes coding for the proteins SoxX, SoxA, SoxB, SoxY, and SoxZ, plus the accessory protein SoxW, which is a thioredoxin serving the purpose of reducing the different subunits of the Sox multienzyme complex to their functionally active states. The genome bin designated as LotusPond_MAG_Thermus_sp. encoded the proteins SoxX, SoxA, SoxB, SoxC, and SoxD, while the one entitled as LotusPond_MAG_Unclassified_Chromatiales contained genes for SoxX, SoxA, SoxB, and SoxC. LotusPond_MAG_Paracoccus_sp._1 contained gene encoding SoxB, SoxCD, and the additional sulfur oxidation proteins SoxF (a periplasmic flavoprotein sulfide dehydrogenase) and SoxG (a thiosulfate-induced periplasmic zinc metallohydrolase that can act as a potential thiol esterase), while the largely incomplete genome bin designated as LotusPond_MAG_Paracoccus_sp._2 contained genes for only SoxY, SoxZ, and the transcriptional regulator of the sox operon called SoxR.

The population genome bin LotusPond_MAG_Sulfurihydrogenibium_azorense encompassed genes for all the four subunits—alpha (K17993), delta (K17994), gamma (K17995) and beta (K17996)–of the signature protein of the genus called sulfhydrogenase (HydADGB), which is H2:polysulfide oxidoreductase catalyzing hydrogen oxidation via reduction of elemental sulfur or polysulfide to hydrogen sulfide.

Centrality of the rTCA cycle, and Aquificae, in Lotus Pond’s primary productivity

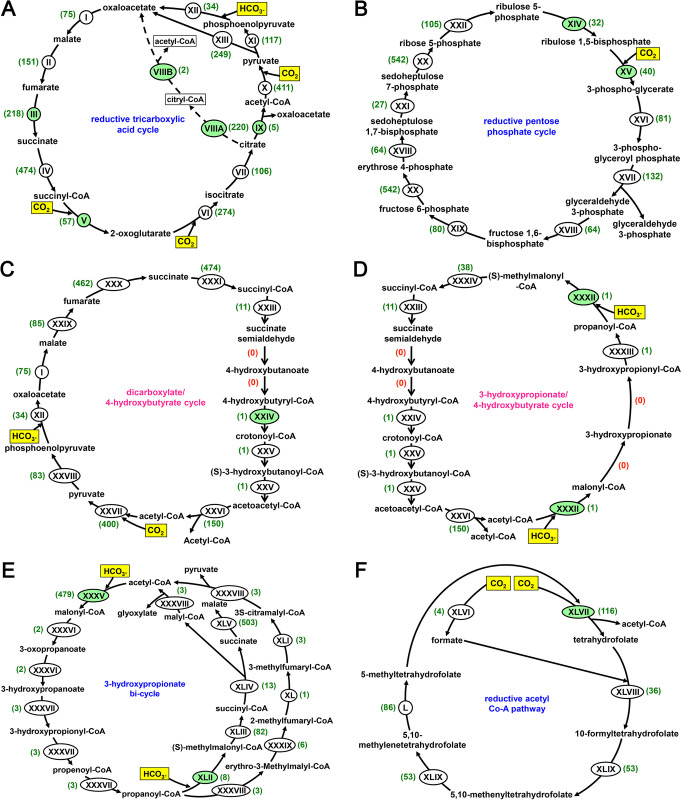

In the assembled metagenome of Lotus Pond there were substantial numbers of CDSs, whether complete or partial, for all the enzymatic steps necessary to execute (i) the rTCA (Arnon-Buchanan) as well as the modified rTCA cycle [65,66], (ii) the reductive pentose phosphate (Calvin-Benson-Bassham) cycle [67], (iii) the 3-hydroxypropionate bi-cycle [68], and (iv) the reductive acetyl Co-A (Wood-Ljungdahl) pathway [65,69]. For the other major pathways of carbon assimilation (autotrophic carbon fixation), namely (v) the dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle [70] and (vi) the 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle [65], genes concerned with a number of intermediate transformations were either missing from the metagenome or were represented by just one or two CDSs (Fig 5). For the other recently-reported and not so common pathways, the key biochemical steps are rendered by the specialized activities of certain typical enzyme variants for which genes are difficult to identify on the basis of homology analysis alone. These pathways are (vii) the reverse oxidative TCA (roTCA) cycle, where citrate is converted to acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate by a reverse acting citrate synthase homolog [71], (vii) the transaldolase variant of the Calvin cycle mediated by Form III RubisCO [72], and (ix) the reductive glycine pathway, where CO2 is converted to formate by the action of a formate dehydrogenase, and 5,10-methylene-tetrahydrofolate is converted to glycine by a glycine cleavage/synthase system [73].

Fig 5. Simplified schematic view of the carbon assimilation pathways for which genes were identified in the assembled metagenome of Lotus Pond.

The relevant genes were identified based on the annotation of CDSs with reference to the published literature, and biochemical modules curated under the KEGG Pathway Maps database located at https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html: (A) reductive citrate cycle, (B) reductive pentose phosphate cycle, (C) dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle, (D) 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle, (E) 3-hydroxypropionate bi-cycle, and (F) reductive acetyl Co-A pathway. Names of the pathways for which one or more genes were undetectable in the metagenome have been written in pink fonts. The active inorganic carbon substrates assimilated by the different pathways are highlighted in yellow. The biochemical conversions (steps) of the different pathways for which CDSs could be identified in the assembled metagenome are indicated by the roman numerals I through L. While the roman numerals shaded green indicate the key enzymatic steps of the pathway in question, the numbers given in parentheses denote the numbers of CDSs identified for the individual enzymatic steps. The enzyme-coding genes actually detected in the metagenome for the biochemical steps labeled as I through L are enumerated below by their KEGG orthology identifiers. I—K00024; II—K01676, K01677, K01678, K01679; III—K18556, K18557, K18558, K18559, K18560; IV—K01902, K01903; V—K00174, K00175, K00176, K00177; VI—K00031; VII—K01681, K01682; VIIIA—K15232, K15233; VIIB—K15234; IX—K15230, K15231; X—K00169, K00170, K00171, K00172, K03737; XI—K01006, K01007; XII—K01595; XIII—K01958, K01959, K01960; XIV—K00855; XV—K01601, K01602; XVI—K00927; XVII—K00134, K00150; XVIII—K01623, K01624; XIX—K01086, K02446, K03841, K11532; XX—K00615; XXI—K01086, K11532; XXII—K01807, K01808; XXIII—K15038; XXIV—K14534; XXV—K15016; XXVI—K00626; XXVII—K00169, K00170, K00171, K00172; XXVIII—K01007; XXIX—K01677, K01678; XXX—K00239, K00240, K00241, K18860; XXXI—K01902, K01903; XXXII—K15037; XXXIII—K15020; XXXIV—K05606, K01848, K01849; XXXV—K02160, K01961, K01962, K01963; XXXVI—K14468; XXXVII—K14469; XXXVIII—K08691; XXXIX—K14449; XL—K14470; XLI—K09709; XLII—K15052; XLIII—K05606, K01847, K01848, K01849; XLIV—K14471, K14472; XLV—K00239, K00240, K00241, K01679; XLVI—K05299, K22015; XLVII—K00194, K00195, K00196, K00197, K00198, K14138; XLVIII—K01938; XLIX—K01491; L—K00297. In the panel A showing the different steps of the rTCA cycle, dotted lines indicate the reactions of the modified rTCA cycle which are mediated by the enzymes citryl-CoA synthetase (VIIIA) and citryl-CoA lyase (VIIIB).

In case of rTCA cycle, CDSs detected in Lotus Pond’s assembled metagenome included 5, 218, and 57 homologs for (i) ATP-citrate lyase AclAB (K15230 and K15231), (ii) NADH-dependent fumarate reductase FrdABCDE (K18556, K18557, K18558, K18559 and K18560), and (iii) ferredoxin-dependent 2-oxoglutarate synthase/oxidoreductase KorABCD (K00174, K00175, K00176 and K00177), which catalyze the key reactions (i) citrate to acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate, (ii) fumarate to succinate, and (iii) succinyl CoA to 2-oxoglutarate, respectively. Most of these CDSs exhibited closest sequence similarities with homologs from members of Aquificae followed by Thermotogae. CDSs corresponding to K18556, K18557, K18558, K18559 and K18560 were also detectable within LotusPond_MAG_Unclassified_Aquificaceae, while CDSs corresponding to K15230 and K15231, and K18556 and K18557 were identified within LotusPond_MAG_Sulfurihydrogenibium_azorense. Furthermore, in the assembled metagenome of Lotus Pond, 411, 34, 57 and 274 CDSs were detected for the conversion of (i) acetyl-CoA to pyruvate (with CO2 addition), (ii) phosphoenolpyruvate to oxaloacetate (with HCO3¯ addition), (iii) succinyl-CoA to 2-oxoglutarate, and (iv) 2-oxoglutarate to isocitrate (the last two conversions involve CO2 addition) respectively (Fig 5A).

Apart from the key rTCA cycle genes mentioned above, 108 and 112 CDSs were detectable in Lotus Pond’s assembled metagenome for the two subunits of citryl-CoA synthetase (K15232 and K15233 respectively), while two CDSs were also there for citryl-CoA lyase (K15234). Notably, all the CDSs corresponding to these two enzymes catalyzing the two key reactions of the modified rTCA cycle, namely citrate to citryl-CoA, and citryl-CoA to oxaloacetate and acetyl-CoA, exhibited closest sequence similarities with homologs from Aquificae. Corroboratively, CDSs corresponding to K15232, K15233 and K15234 were identified within LotusPond_MAG_Unclassified_Aquificaceae, while a single CDS corresponding to K15234 was detectable in LotusPond_MAG_Sulfurihydrogenibium_azorense.

As regards the reductive pentose phosphate cycle, CDSs detected in Lotus Pond’s assembled metagenome included 32 and 40 homologs for (i) phosphoribulokinase (K00855) and (ii) ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RubisCO, K01601 and K01602), which catalyze the key reactions (i) ribulose-5-phosphate to ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate, and (ii) ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate to 3-phosphoglycerate (the sole CO2 fixing step of the pathway), respectively (Fig 5B). While most of these CDSs exhibited closest sequence similarities with homologs from members of Deinococcus-Thermus, CDSs corresponding to K00855, as well as K01601 and K01602, were there in LotusPond_MAG_Thermus_sp.; notably, homologs of K01601 and K01602 encoding the large (RbcL) and small (RbcS) subunits of RubisCO were also detected in LotusPond_MAG_Thermosynechococcus_sp. and LotusPond_MAG_Unclassified_Chromatiales.

So far as the dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle is concerned, only one Lotus Pond CDS was found for 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase (K14534), which governs the key step of converting 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA to crotonyl-CoA. Moreover, though 400 and 34 CDSs were there in the Lotus Pond metagenome for the conversion of (i) acetyl-CoA to pyruvate, and (ii) phosphoenolpyruvate to oxaloacetate, via addition of CO2 and HCO3¯ respectively, the numbers of CDSs detected for the reactions of the hydroxybutyrate half of the cycle were extremely low (Fig 5C). In this context it is noteworthy that the carbon fixation reactions of the dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle are same as the first two carbon fixation steps of the rTCA cycle: phosphoenolpyruvate to oxaloacetate conversion involves the same enzyme phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (KEGG orthology: K01595) in either pathway, while there is only one additional enzyme [pyruvate-ferredoxin/flavodoxin oxidoreductase Por (K03737)] for acetyl-CoA to pyruvate conversion by the rTCA cycle, and that precisely accounted for the extra 11 CDSs ascribed to the corresponding step of the rTCA cycle (Fig 5). Evidently, the high CDS counts for the carbon fixation reactions of dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle were only a reflection of the overall preponderance of the rTCA cycle, and dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle was plausibly not prevalent in the microbiome.

The 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle is characterized by its signature protein acetyl-CoA/propionyl-CoA carboxylase (biotin-dependent). This protein by virtue of its three subunits structured in an α4β4γ4 configuration and having the functional domains for biotin carboxylase (K01964), biotin carboxyl carrier protein (K15037), and carboxytransferase (K15036) respectively, catalyzes (i) the conversion of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA, as well as (ii) the conversion of propanoyl-CoA to (S)-methylmalonyl-CoA, using HCO3¯ as the active inorganic carbon source in both the reactions. The Lotus Pond metagenome had only one Crenarchaeota-affiliated CDS matching the gene K15037 but no CDS for the genes K01964 and K15036 (Fig 5D).

The key steps of the 3-hydroxypropionate bi-cycle involve carbon fixation reactions similar to those encountered in the 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle. However, the two HCO3¯ assimilating reactions in the bi-cycle are catalyzed by enzymes that are distinct from the acetyl-CoA/propionyl-CoA carboxylase of 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle. For instance, conversion of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA in the bi-cycle is rendered by a separate acetyl-CoA carboxylase complex AccABCD, which is made up of the biotin carboxylase subunit AccC (K01961), the biotin carboxyl carrier AccB (K02160), and the carboxyl transferase subunits alpha (AccA; K01962) and beta (AccD; K01963). Propanoyl-CoA, in the bi-cycle, is converted to (S)-methylmalonyl-CoA by an independent propionyl-CoA carboxylase (K15052). The Lotus Pond metagenome encompassed 479 CDSs for the AccABCD complex, whereas only eight CDSs could be identified for propionyl-CoA carboxylase (Fig 5E). Most of the Lotus Pond CDSs corresponding to AccABCD and propionyl-CoA carboxylase exhibited closest sequence similarities with homologs from Aquificae and Chloroflexi respectively. The Lotus Pond MAGs affiliated to unclassified Aquificaceae and Sulfurihydrogenibium azorense encompassed CDSs for all the subunits of AccABCD.

In the key step of the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway an O2-sensitive bifunctional multienzyme complex called carbon monoxide dehydrogenase/acetyl-CoA synthase (CODH/ACS) first reduces a CO2 molecule to a CO (carbonyl) moiety, and then combines the CO with a methyl (CH3) group (furnished by the other branch of the pathway) and CoA to generate acetyl-CoA. The CODH/ACS complex is made up of five subunits and four of them are homologous across Archaea and Bacteria. In Archaea they are referred to as the α, β, γ and δ subunits, or the CdhA (K00192), CdhC (K00193), CdhE (K00197) and CdhD (K00194) proteins, whereas in Bacteria the same four homologs are known as the β, α, γ and δ subunits, or the AcsA (K00198), AcsB (K14138), AcsC (K00197) and AcsD (K00194) proteins, respectively. In addition, an ε subunit called CdhB (K00195) is exclusively present in the Archaea, while the AcsE (K15023) protein is exclusive to Bacteria. Overall 13 CDSs for the different components of the Cdh and/or Acs complex were identified in Lotus Pond’s assembled metagenome (Fig 5F), and most of them showed closest sequence similarities with homologs from Thermodesulfobacteria. Concurrently, LotusPond_MAG_Unclassified_Thermodesulfobacteriaceae encompassed one CDS each for AcsA, AcsB and AcsD.

Copious invasion, virulence, and antibiosis related genes in the Lotus Pond metagenome

While there were several complete or partial CDSs (a total of 76) in the Lotus Pond vent-water’s assembled metagenome for proteins concerned with biofilm formation and cellular adhesion, quite a few CDSs attributed to hemagglutinin and hemolysin biosynthesis (86), and stationary phase metabolisms including the formation of persister cells (43) were also there (S2 Table in S1 File). Furthermore, the metagenome encompassed 1084 complete or partial CDSs encoding the different components of Type-I, Type-II, Type-III, Type-IV, Type-VI, Type-VIII and Type-IX secretion systems (SSs). Of these, most were parts of the Type-II, and Type-III and Type-IV SSs. In terms of taxonomic distribution (S2 Table in S1 File), most of the SS related CDSs identified (57% of the total 1084) were attributed to Aquificae, followed by Betaproteobacteria (~10%). Gammaproteobacteria and Firmicutes each accounted for 8%, while Alphaproteobacteria accounted for ~5% of all these CDSs. Approximately 1–3% of all SS related CDSs were ascribable to Deinococcus-Thermus, Unclassified Proteobacteria, Unclassified Bacteria, Thermodesulfobacteria, Cyanobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Archaea. Thermotogae accounted for ~0.6% of the SS related CDSs identified in the assembled metagenome. The Lotus Pond MAGs also encompassed quite a few CDSs for biofilm formation, cellular adhesion, invasion and virulence, with the one identified as Vibrio metschnikovii having the maximum number and diversity of CDSs for these functions.

Genomic loci (gene clusters) concerned with the biosynthesis of diverse bioactive natural compounds were identified using the antiSMASH pipeline. By searching for specific sequence signatures in the putative biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) detected the following classes of secondary metabolites were predicted to be synthesized within the microbiome: N-acyl amino acids, aryl polyene compounds, protease inhibitor-containing beta-lactones, ectoines, homoserine lactones, and terpenes. BGCs corresponding to non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) and NRPS-like fragments, Type I and other polyketide synthases, ribosomally synthesised and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs), RiPP recognition elements, and a host of unclassified secondary metabolite-related proteins were also detectable in Lotus Pond’s assembled metagenome. Overall, approximately 3000 complete or partial CDSs (S2 and S8 Tables in S1 File) could be identified as parts of BGCs and/or involved directly or indirectly in the biosynthesis of antibiotics such as the acarbose and validamycin, carbapenems, monobactams, neomycin/kanamycin/gentamicin, novobiocin, penicillins and cephalosporins, phenazine, prodigiosin, staurosporine, streptomycin, and vancomycin. So far as the key biosynthetic genes are concerned, several CDSs for non-ribosomal peptide synthetase and prephenate dehydrogenase, which are central to the vancomycin biosynthesis pathway, were found in the Lotus Pond metagenome (S2 Table in S1 File). CDSs for myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase, dTDP-4-dehydrorhamnose 3,5-epimerase, and dTDP-4-dehydrorhamnose reductase, which are all crucial for the biosynthesis of streptomycin were also detected alongside CDSs for the phenazine biosynthesis protein PhzF (S2 Table in S1 File). For the biosynthesis of carbapenems, several homologs of the carA, carB and carC genes that encode the carbamoyl phosphate synthetase holoenzyme involved in the initial steps of carbapenem biosynthesis (formation of the carbapenem backbone) were detected alongside homologs of carD that is involved in the modification of the carbapenem backbone (S2 Table in S1 File). In terms of taxonomic distribution (S8 Table in S1 File), maximum number of these CDSs (~29% of the total) was attributed to Aquificae, followed by Alphaproteobacteria (~21%). The entire domain Archaea accounted for only ~2% of all antibiotic biosynthesis related genes identified. Apart from the BGCs, several genomic loci concerned with the resistance of diverse antibiotics, disinfecting agents, and antiseptics were identified by annotating the assembled metagenome with reference to the CARD database. The antimicrobial agents corresponding to which putative resistance related gene clusters were detected included beta-Lactam compounds, chloramphenicol, erythromycin, fluoroquinolones, metronidazole, teicoplanin, tetracycline, trimethoprim, and vancomycin. In the eggNOG-based annotation (S2 and S8 Tables in S1 File), overall ~5500 such complete or partial CDSs were identified in the assembled metagenome of Lotus Pond’s vent-water that were directly or indirectly involved in the resistance of aminoglycosides, bacitracin, beta-lactam compounds, cationic antimicrobial peptides, fluoroquinolones, imipenem, nisin, polymyxin antibiotics, tetracycline, and vancomycin. Furthermore, a wide variety of multi-drug resistance related efflux pumps were detected in the assembled metagenome via eggNOG annotation. In terms of taxonomic distribution (S8 Table in S1 File), considerable number of these antibiotic resistance related CDSs (30% of the total) was attributed to Aquificae, followed by Gammaproteobacteria (~28%). The entire domain Archaea accounted for only one antibiotic resistance related CDS, and the same was meant to protect against aminoglycosides.

Discussion

Comparing the microbial diversities revealed by shotgun metagenomics and 16S amplicon sequencing

The extents of Lotus Pond’s microbial diversity revealed by the different approaches of molecular genetics had their own differences, as well as concurrence. For instance, two archaeal phyla, Crenarchaeota and Euryarchaeota, were identified by taxonomic annotation of the CDSs predicted within the assembled metagenome (S3 Table in S1 File), but searching of metagenomic reads for 16S rRNA-encoding sequences detected only Crenarchaeota (S4 Table in S1 File), whereas PCR amplified 16S rRNA gene sequence based OTU analysis identified Crenarchaeota, Euryarchaeota and Nitrososphaerota (S5 Table in S1 File). Concurrently, the archaeal genera Aeropyrum, Pyrobaculum and Stetteria, identified by direct annotation of metagenomic reads, went undetected in 16S amplicon-based analysis, whereas Methanomassiliicoccus, Methanospirillum and Nitrososphaera, detected via 16S amplicon sequencing, were undetectable in the direct annotation of metagenomic reads (compare S4 and S5 Tables in S1 File).

For Bacteria, 23 phyla were identified via taxonomic classification of CDSs: of these, 10 (Actinobacteria, Aquificae, Bacteroidetes, Chloroflexi, Cyanobacteria, Deinococcus-Thermus, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Thermodesulfobacteria, and Thermotogae) were major phyla embracing >2000 CDSs each, and 13 (Acidobacteria, Chlamydiae, Chlorobi, Deferribacteres, Fusobacteria, Gemmatimonadetes, Nitrospirae, Planctomycetes, Spirochaetes, Synergistetes, Tenericutes, Thermomicrobia, and Verrucomicrobia) were minor phyla with <500 CDSs each (S3 Table in S1 File; Fig 3A). Annotation of metagenomic reads corresponding to 16S rRNA genes detected 12 phyla in all. These included all the 10 major phyla, and only Synergistetes out of the 13 minor phyla, detected via taxonomic classification of CDSs. Additionally, only one such new phylum, namely Armatimonadetes, was detected via direct metagenomic reads (S4 Table in S1 File; Fig 3B) classification that was not represented in the CDS catalog (S3 Table in S1 File; Fig 3A). 16S amplicon-based OTU analysis identified 16 bacterial phyla (S5 Table in S1 File), which included the 10 major ones identified from CDS annotation, three of the 13 minor phyla (Acidobacteria, Spirochaetes and Synergistetes) detected via CDS annotation, plus Armatimonadetes, and two new phyla (Dictyoglomi and Rhodothermota) that were not represented among the CDSs or the metagenomic reads encoding 16S rRNAs.

Annotation of metagenomic reads corresponding to bacterial 16S rRNA genes revealed 92 bacterial genera (S4 Table in S1 File), while OTU analysis of PCR amplified 16S rRNA gene sequences identified 121 (S5 Table in S1 File). Between these two sets of generic names obtained using two different approaches, 50 genera were common, of which seven (Fervidobacterium, Halomonas, Paracoccus, Sulfurihydrogenibium, Tepidimonas, Thermus and Vibrio) were represented in the MAGs obtained from the assembled metagenomic data, and two (Hydrogenobacter and Thiofaba) were represented by very closely related MAGs (namely, LotusPond_MAG_Unclassified_Aquificaceae and LotusPond_MAG_Unclassified_Chromatiales; detailed phylogenomic relationships are given in the Supplementary Results). Of all the genera represented among the MAGs (Tables 1 and S6 in S1 File; Fig 4), Thermosynechococcus alone was not detected in any 16S rRNA gene sequence-based analysis; however, LotusPond_MAG_Thermosynechococcus_sp. did encompass a near-complete 16S rRNA gene, 99.6% similar to the Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1 homolog. This indicated that the nonappearance of Thermosynechococcus in 16S rRNA gene sequence based analyses was a bioinformatic glitch.

Discrepancies are known to arise in the microbial diversities revealed by analyzing the sample sample via shotgun metagenome sequencing and PCR-amplified 16S rRNA gene sequencing. A number of studies have found 16S amplicon sequencing to underrepresent taxa at different hierarchical levels [74–77], whereas the opposite outcome has also been reported by quite a few studies [78,79]. The present data demonstrated that the annotation of metagenomic reads corresponding to 16S rRNA genes reliably delineated most part of the diversity under investigation, at both the phylum and genus levels. Although this approach did not fare well in revealing the scarcely represented taxa, the diversity revealed by this approach was fairly reproducible in the corresponding data obtained via taxonomic classification of CDSs annotated within the assembled metagenome, and the OTUs clustered from PCR-amplified 16S rRNA gene sequences. The latter two approaches, in turn, appeared to be more adept to unearthing the less-abundant taxa, at the phylum as well as genus level. With all the three approaches having their own strengths and limitations, a simultaneous use of all of them seems to be the best practice in obtaining a comprehensive picture of microbial diversity in a given environmental sample.

Lotus Pond’s vent-water microbiome remains stable over time

Over the last ten years, the Lotus Pond has been explored for its vent-water bacterial (but not archaeal) diversity, via 16S amplicon sequencing alone, on five previous time-points [10,17]. A comparison of the present 16S amplicon-based OTU data with those from the past showed that all the 16 bacterial phyla detected in the current investigation (S5 Table in S1 File), except Rhodothermota and Synergistetes, had been identified in previous exploration(s). The five previous explorations too had collectively discovered 16 bacterial phyla, of which only Ignavibacteriae and Nitrospirae went undetected in the present 16S amplicon-based survey. Furthermore, 11 bacterial phyla, namely Actinobacteria, Aquificae, Bacteroidetes, Chloroflexi, Cyanobacteria, Deinococcus-Thermus, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Synergistetes, Thermodesulfobacteria and Thermotogae were consistently detected in the present annotation of CDSs, 16S rRNA-encoding metagenomic reads, and OTUs clustered from 16S amplicon sequences; all of these, except Synergistetes, were detectable in one or more previous studies of 16S amplicon sequencing and analysis.

At the genus level, 121 entities were detected in the current PCR-based investigation (S5 Table in S1 File), out of which 59 were identified in one or more previous explorations, which in turn had collectively discovered 156 genera. Seven out of the 97 genera that were identified previously, but went undetected in the present PCR-based analysis (these were Acidovorax, Armatimonadetes_gp5, Buttiauxella, Cyanobacteria GpIV, Klebsiella, Ornithinimicrobium and Sphingomonas), got identified in the present annotation of metagenomic reads corresponding to 16S rRNA genes (S4 Table in S1 File). In this way, a total of 66 bacterial genera (Table 2) were found to be present consistently in Lotus Pond’s vent-water over a period of approximately ten years. Notably, six out of these 66 genera, namely Fervidobacterium, Halomonas, Paracoccus, Sulfurihydrogenibium, Tepidimonas and Thermus, were unequivocally represented in the population genome bins (MAGs) obtained from the current metagenomic data, while two more, namely Hydrogenobacter and Thiofaba, were represented by very closely related entities, if not direct member strains of the genera. In this way, there were only two such bacterial genera—namely Thermosynechococcus and Vibrio—that figured among the MAGs obtained in the current study but were not represented in any of the previous OTU data.

Table 2. Bacterial genera that were detected in the present exploration of the Lotus Pond vent-water as well as in one or more previous studies of the same habitat using 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis.

| Phylum to which the genera belonged | Names of the genera1,2 | Maximum temperature for Laboratory-growth3 (°C) |

Sampling date of the previous study in which the genus was also identified | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 July, 2013 [17] |

20 October, 2014 [10] |

|||

| Actinobacteria | Brevibacterium | 42 | + | + |

| Corynebacterium | 42 | + | + | |

| Mycobacterium | 43 | - | + | |

| Nocardioides | 37 | - | + | |

| Ornithinimicrobium | 50 | + | - | |

| Rothia | 38 | + | - | |

| Armatimonadetes | Gp5 | - | - | + |

| Gp7 | - | - | + | |

| Aquificae | Hydrogenobacter | 85 | + | + |

| Sulfurihydrogenibium | 80 | + | + | |

| Bacteroidetes | Chryseobacterium | 37 | + | + |

| Cloacibacterium | 40 | + | + | |

| Pedobacter | 35 | - | + | |

| Porphyromonas | 37 | + | - | |

| Prevotella | 45 | + | - | |

| Chloroflexi | Chloroflexus | 59 | + | + |

| Cyanobacteria | GpXIII | - | - | + |

| GpIV | - | - | + | |

| Deinococcus-Thermus | Thermus | 80 | + | + |

| Truepera | 50 | + | + | |

| Dictyoglomi | Dictyoglomus | 80 | - | + |

| Firmicutes | Anoxybacillus | 70 | + | + |

| Bacillus | 70 | + | + | |

| Chryseomicrobium | 45 | + | - | |

| Enterococcus | 45 | + | - | |

| Exiguobacterium | 49 | + | + | |

| Gemella | 37 | - | + | |

| Lactococcus | 40 | + | - | |

| Lysinibacillus | 45 | - | + | |

| Planococcus | 42 | + | + | |

| Sporolactobacillaceae_incertae_sedis | - | - | + | |

| Staphylococcus | 40 | + | + | |

| Streptococcus | 45 | + | + | |

| Alphaproteobacteria | Azospirillum | 37 | + | + |

| Bradyrhizobium | 37 | + | + | |

| Brevundimonas | 42 | + | + | |

| Paracoccus | 45 | + | + | |

| Sphingobium | 37 | - | + | |

| Sphingomonas | 45 | + | + | |

| Sulfitobacter | 40 | + | + | |

| Betaproteobacteria | Achromobacter | 42 | + | + |

| Acidovorax | 37 | + | + | |

| Burkholderia | 37 | + | + | |

| Comamonas | 44 | - | + | |

| Delftia | 40 | - | + | |

| Herbaspirillum | 45 | + | - | |

| Pelomonas | 37 | + | + | |

| Ralstonia | 41 | + | + | |

| Tepidimonas | 60 | + | + | |

| Gammaproteobacteria | Aeromonas | 41 | + | + |

| Acinetobacter | 37 | + | + | |

| Buttiauxella | 42 | - | + | |

| Enhydrobacter | 41 | + | + | |

| Escherichia/Shigella | 37 | - | + | |

| Halomonas | 50 | + | + | |

| Klebsiella | 37 | - | + | |

| Marinobacter | 50 | + | + | |

| Pseudomonas | 42 | - | + | |

| Psychrobacter | 38 | + | + | |

| Rheinheimera | 35 | - | + | |

| Serratia | 35 | + | - | |

| Shewanella | 30 | + | - | |

| Stenotrophomonas | 42 | + | + | |

| Thiofaba | 51 | + | + | |

| Thiovirga | 34 | + | - | |

| Thermotogae | Fervidobacterium | 90 | + | + |

1 Genera detected in the present PCR-amplified 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis are indicated by bold fonts.

2 Names of the genera that were detected in the present annotation of metagenomic reads corresponding to 16S rRNA genes are underscored.