Abstract

Language development entails four fundamental and interactive abilities: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Over the past four decades, a large body of evidence has indicated that reading acquisition is strongly associated with a child's listening skills, particularly the child's sensitivity to phonological structures of spoken language. Furthermore, it has been hypothesized that the close relationship between reading and listening is manifested universally across languages and that behavioral remediation using strategies addressing phonological awareness alleviates reading difficulties in dyslexics. The prevailing view of the central role of phonological awareness in reading development is largely based on studies using Western (alphabetic) languages, which are based on phonology. The Chinese language provides a unique medium for testing this notion, because logographic characters in Chinese are based on meaning rather than phonology. Here we show that the ability to read Chinese is strongly related to a child's writing skills and that the relationship between phonological awareness and Chinese reading is much weaker than that in reports regarding alphabetic languages. We propose that the role of logograph writing in reading development is mediated by two possibly interacting mechanisms. The first is orthographic awareness, which facilitates the development of coherent, effective links among visual symbols, phonology, and semantics; the second involves the establishment of motor programs that lead to the formation of long-term motor memories of Chinese characters. These findings yield a unique insight into how cognitive systems responsible for reading development and reading disability interact, and they challenge the prominent phonological awareness view.

Keywords: dyslexia, phonological awareness, reading development, child language, reading Chinese

Learning to read involves a complex system of skills relevant to visual (i.e., the appearance of a word), orthographic (visual word form), phonological, and semantic processing. In one prominent theory, reading acquisition builds on the child's spoken language, which is already well developed before the start of formal schooling; once a novel written word is decoded phonologically, its meaning will become accessible via the existing phonology-to-semantics link in the oral language system (1-3). Thus, the child's awareness of the phonological structure of speech plays a pivotal role in the development of reading ability. Since the 1960s, a large number of studies have supported this theory, while also suggesting that the child's phonological sensitivity serves as a universal mechanism governing reading ability across different writing systems including alphabetic English (4-14) and logographic Chinese (15-17). Phonological awareness occurs at several levels, from coarse sound units such as syllables to fine-grained sound units such as phonemes represented by letters. Different grain sizes of speech sounds may account for differential variances in reading performance across cultures (14, 16, 18); the centrality of phonological sensitivity in learning to read across languages, however, remains unchallenged.

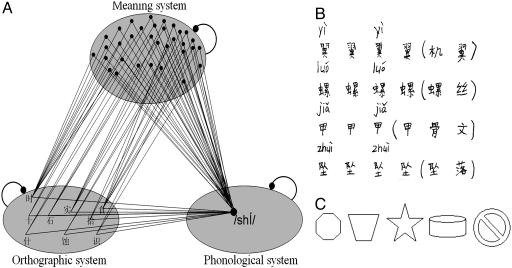

In this study, we report evidence contrary to the accepted theory. We argue that the role of phonological awareness in Chinese reading development is minor, and we investigate other skills that account for successful reading acquisition. Central to this argument are two characteristics of the Chinese language: (i) Spoken Chinese is highly homophonic, with a single syllable shared by many words, and (ii) the writing system encodes these homophonic syllables in its major graphic unit, the character. Thus, when learning to read, a Chinese child is confronted with the fact that a large number of written characters correspond to the same syllable (as depicted in Fig. 1A), and phonological information is insufficient to access semantics of a printed character.

Fig. 1.

Complex relationships of visual, orthographic, phonological, and semantic systems in Chinese. (A) The extensive homophony in Chinese entails that many orthographic units converge on one phonological unit, resulting in a kind of convergent connection, and a phonological unit connects with more than one meaning nodes, producing a kind of divergent connection. For example, the pronunciation “/shi/” is shared by 10 characters with the same tone but very different meanings. The orthographic units of these characters converge on the phonological node/shi/, which connects with all of the meaning nodes of these characters. This pattern is one of convergent phonology and divergent semantics, the typical pattern in reading in Chinese. (B) A sample of a Chinese child's writing homework. In Chinese elementary schools, a novel character is usually written down 4-6 times continuously, often with its pronunciation (e.g., “/yi/”) denoted by Pinyin appearing above the character. (C) A sample of pictures of simple objects for children to copy by drawing.

In addition to these system-level (language and writing system) factors, Chinese writing presents some script-level features that distinguish it visually from alphabetic systems. The Chinese character is composed of strokes and subcharacter components that are packed into a square configuration, possessing a high, nonlinear visual complexity. Significant spatial analysis is intrinsic in learning a Chinese character, and visual-orthographic processing is an important part of character reading (19, 20). Thus, an integrated reading circuit that links orthography, meaning, and pronunciation is crucial for fluent reading (21-23), whereas dysfunctional mapping of either orthography-to-phonology or orthography-to-meaning can lead to reading disability (24). We suggest that the visual-orthographic demands of written Chinese necessitate what has become a prevalent strategy for teaching children to learn to read, namely asking children to repeatedly copy, by writing down, samples of single characters (for example see Fig. 1B). Through writing, children learn to deconstruct characters into a unique pattern of strokes and components and then regroup these subcharacters into a square linguistic unit. This type of decoding occurs at the visual-orthographic level and is assumed to facilitate children's awareness of the character's internal structure (orthographic awareness). This awareness supports the formation of connections among orthographic, semantic, and phonological units of the Chinese writing system and may be associated with the quality of lexical entries in long-term memory (25).

The purpose of this study was to determine which variables best predict and facilitate skilled reading in Chinese children. In experiment 1, we developed a test of writing in which beginning readers (n = 58, 7-8 years of age) and intermediate readers (n = 73, 9-10 years of age) were required to copy written characters from samples as quickly and accurately as possible. To directly examine the relative contribution of writing and phonological sensitivity to reading ability in Chinese, we administered two phonological awareness tests to our subjects individually. In one, the child listened to sets of four syllables; for each set, one of the syllables was the odd one out by virtue of lacking a beginning or ending sound shared by the other three syllables (oddity test). This test was to assess the child's phonological awareness of onsets and rimes, two fine-grained subdivisions of a syllable. In a second test to evaluate the child's sensitivity to coarse sound units, the child listened to a two- or three-syllable spoken word and was required to delete a specified syllable and verbally report the remaining sound(s) (syllable deletion). Because reading ability is relevant to symbol processing speed (26), we used a rapid automatized naming (RAN) task to measure the general processing speed component, where children were asked to name printed digits (2, 4, 6, 7, and 9, each repeated 10 times) as fast and accurately as possible. Experiment 1 found a strong relationship between writing and reading ability, whereas the role of phonological awareness was minor.

In experiment 2, we sought to elucidate how writing mediates reading development. We considered two possible mechanisms. The first assumes that writing facilitates the development of orthographic awareness, which, in turn, has a positive influence on reading acquisition. Under this model, one would predict that strong skills in the writing of pseudocharacters, by virtue of their orthographic legality, would impact orthographic awareness and demonstrate a strong association with reading performance. By contrast, the ability to draw simple objects does not involve orthographic processes and thus should not be related to reading ability.

Alternatively, the link between writing and reading may rely less on orthographic awareness than on the underlying motor programs that subserve writing (27). Writing of Chinese characters requires a high-order organization of strokes and components that constitute the internal structure of the character. This motor activity may result in pairing of hand movement patterns and language stimuli (28, 29) and may help form long-term motor memory of Chinese characters. This motor memory of linguistic stimuli will facilitate the consolidation process of lexical representations in the cognitive system and make mental organizations of written Chinese resistant to disruption. On this motoric mechanism, writing pseudocharacters is assumed to be associated with reading performance, whereas other sorts of activities involving precise, coordinated movements such as picture drawing should be also correlated with reading performance. Furthermore, because pictures of objects possess higher visual complexities than do many Chinese characters, picture drawing, in general, demands finer motor activity than writing. This analysis suggests a possibility that the influence of picture drawing on reading may have a developmental lag compared with character writing. If so, the predictive power of picture drawing on reading performance will therefore be greater for intermediate readers than for beginners.

To determine the mechanisms that mediate the effect of writing on reading acquisition, in experiment 2, we asked the two groups of children participating in experiment 1 to perform two tasks: copying by writing printed pseudocharacters, and copying by drawing simple figures presented on a sheet (for example see Fig. 1C).

Methods

Subjects. From three classrooms of Beijing Yong Tai Primary School, 131 children were tested, of whom 58 were beginning readers (23 boys and 35 girls, 7-8 years of age) and 73 were intermediate readers (31 boys and 42 girls, 9-10 years of age). This primary school was located in a suburban community of average level socioeconomic status outside of Beijing. All children were native speakers of Putonghua, the official dialect of Mainland China and the language of instruction in school. They had not started to study English or other languages at the time this study was conducted. Subjects' handedness was judged by an inventory based on Snyder and Harris (30). The subjects' demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1, and all children participated in experiments 1 and 2.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics and descriptive statistics for all children.

| Variable | Beginning readers (n = 58) | Intermediate readers (n = 73) |

|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | ||

| Age, months | 98.2 (4.7) | 116.9 (5.1) |

| Handedness | ||

| Right | 56 | 70 |

| Left | 2 | 3 |

| Nonverbal IQ in percentile | 76 (21) | 70 (22) |

| Character reading (max = 200) | 78.3 (25:3) | 113.6 (23.9) |

| Character writing (max = 60) | 12.2 (4.0) | 24.1 (6.4) |

| Syllable deletion (max = 16) | 14.2 (1.7) | 14.7 (1.4) |

| Oddity (max = 20) | 9.1 (3.4) | 10.8 (3.7) |

| RAN, sec | 26.5 (6.0) | 21.7 (4.6) |

| Experiment 2 | ||

| Pseudocharacter writing (max = 80) | 35.5 (7.0) | 50.0 (8.1) |

| Picture drawing (max = 24) | 14.8 (4.0) | 17.4 (4.6) |

Data are presented as mean, with standard deviations in parentheses.

Experimental Materials. In experiment 1, the materials consisted of a battery of writing, phonological, and rapid-naming tasks and measures of intelligence and reading achievement. In the writing task, children were given 60 real characters printed on one sheet, and were asked to copy down as many as possible within 3 min. The standardized Chinese version of Raven's Standard Progressive Matrices was used as an index of nonverbal intelligence. The mean nonverbal Raven IQ fell in the 76th percentile for beginning readers (ranged from the 10th to the 95th percentile, SD = 21) and the 70th percentile for intermediate readers (ranged from the 5th to the 95th percentile, SD = 22). The writing and intelligence tests were administered on a group basis.

The phonological awareness, rapid-naming, and reading tasks were administered individually, which took ≈20 min. In the oddity test, there were 20 items that were discriminating after item analysis, with a resultant Cronbach's α coefficient of 0.90 (beginning readers) and 0.83 (intermediate readers). In syllable deletion, there were 16 test items, all being found to be discriminating after item analysis, with resulting Cronbach's α coefficients of 0.79 (beginning readers) and 0.75 (intermediate readers). In rapid naming, naming latencies were recorded with a stopwatch to the nearest millisecond.

To evaluate children's reading ability, 200 Chinese characters in the test were selected from textbooks that were used in Beijing primary schools for first to fifth graders, 40 from each. Characters were arranged in a sequence that increased in difficulty (as determined by grade level and visual complexity or stroke number). Children were asked to read the characters aloud as quickly and accurately as possible within 2 min.

In experiment 2, we used 80 pseudocharacters and 24 line-drawing pictures in the copying task. Pseudocharacters were unpronounceable but orthographically legal. For both pseudocharacters and objects, children were required to copy down as many stimuli from the samples as they could within 5 min. They were instructed to complete the task with precision; accuracy scores were based on the children's ability to produce an entirely accurate representation, as determined by two independent observers.

Results

Experiment 1: Relative Contributions of Writing, Phonological Awareness, and RAN to Reading Development of Chinese Children. Significant differences were found between the two age groups in Chinese reading (t = 8.28, P < 0.001), writing (t = 12.374, P < 0.001), oddity test (t = 2.709, P < 0.01), and RAN (t = 5.131, P < 0.001), with intermediate readers showing better performance than beginning readers (Table 1). Performance in syllable deletion was nonsignificantly higher for the older group (t = 1.849, P = 0.067). This less reliable syllable level difference (compared with the differences at finer grain units) suggests that syllable analysis develops more quickly in children than subsyllabic processing, including the phoneme (31) and the onset and rime units (32). Correlation analyses (after partialing out nonverbal intelligence assessed by Raven's test) indicated significant relationships between Chinese reading performance and writing, syllable deletion, and RAN in both groups (Table 2). Oddity was significantly associated with reading in the intermediate group, but not in the beginning group.

Table 2. Partial correlations between reading performance and component skills, controlling for nonverbal intelligence.

| Skill | Beginning readers | Intermediate readers |

|---|---|---|

| Writing | 0.497*** | 0.471*** |

| Syllable deletion | 0.307* | 0.333** |

| Oddity | 0.035 | 0.364** |

| RAN | −0.383** | −0.502*** |

*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005; ***, P < 0.001.

To determine the relative power of character writing, phonological awareness, and RAN in predicting Chinese reading acquisition, we conducted a series of fixed-order hierarchical multiple regressions, with reading performance as the criterion variable and performances in other tests as independent variables (Table 3). For beginning readers, nonverbal IQ accounted for 10.1% of the variance in reading (ΔF = 6.305, P < 0.05). Writing, syllable deletion, and RAN, respectively, accounted for an additional 22.2% (ΔF = 18.044, P < 0.001), 8.5% (ΔF = 5.737, P < 0.05), and 13.1% (ΔF = 9.423, P < 0.005) of the variance. Oddity did not predict beginning readers' reading achievement. For intermediate readers, nonverbal IQ did not predict reading; however, writing, syllable deletion, oddity, and rapid naming, respectively, accounted for 19.8% (ΔF = 17.606, P < 0.005), 10.5% (ΔF = 8.426, P < 0.001), 12.2% (ΔF = 9.988, P < 0.005), and 24.0% (ΔF = 22.915, P < 0.001) of the variance.

Table 3. Summary of hierarchical multiple regressions that tested the predictive power of various component skill measures on reading performance.

| Reading performance (ΔR2)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| step | Variable | Beginning readers | Intermediate readers |

| Controlling for variation in nonverbal IQ | |||

| 1 | Nonverbal IQ | 0.101* | 0.036 |

| 2 | Writing | 0.222** | 0.198** |

| 2 | Syllable Deletion | 0.085* | 0.105** |

| 2 | Oddity | 0.001 | 0.122** |

| 2 | RAN | 0.131** | 0.240** |

| Controlling for variation in nonverbal IQ and RAN | |||

| 1 | Nonverbal IQ | 0.101* | 0.036 |

| 2 | RAN | 0.131** | 0.240** |

| 3 | Writing | 0.136** | 0.062* |

| 3 | Syllable deletion | 0.068* | 0.031† |

| 3 | Oddity | 0.001 | 0.060* |

| Controlling for variation in nonverbal IQ, RAN, and phonological awareness | |||

| 1 | Nonverbal IQ | 0.101* | 0.036 |

| 2 | RAN | 0.131** | 0.240** |

| 3 | Syllable deletion | 0.068* | 0.031† |

| 4 | Oddity | 0.000 | 0.046* |

| 5 | Writing | 0.104** | 0.036* |

| Controlling for variation in nonverbal IQ, writing, and RAN | |||

| 1 | Nonverbal IQ | 0.101* | 0.036 |

| 2 | Writing | 0.222** | 0.198** |

| 3 | RAN | 0.045† | 0.105** |

| 4 | Syllable deletion | 0.037† | 0.026 |

| 4 | Oddity | 0.003 | 0.034† |

†, P < 0.10; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005.

Because the reading and writing tasks in this study were time-limited, it was likely that their shared variance reflected a general speed processing component. To determine the contribution of writing (and also phonological awareness) after RAN was controlled, we performed another set of fixed-order multiple regression analyses, with children's nonverbal intelligence being again entered in the equation as step 1, and RAN being entered as step 2. Writing, syllable deletion, or oddity was then entered as the last step (Table 3). In beginning readers, writing accounted for 13.6% of the variance (ΔF = 11.612, P < 0.001), whereas syllable deletion accounted for 6.8% of the variance (ΔF = 5.265, P < 0.05). In intermediate readers, writing and oddity accounted for 6.2% (ΔF = 6.322, P < 0.05) and 6.0% (ΔF = 6.13, P < 0.05) of the variance, respectively; syllable deletion did not account for additional variance in reading performance.

In principle, writing and phonological awareness may be related to each other; the child often pronounces characters during writing production. To estimate the unique predictive power of writing and phonological awareness on reading development, we entered writing or phonological awareness as the last step in the equation after entering all other factors (Table 3). With this stringent statistical control, we found that writing still contributed 10.4% (ΔF = 9.117, P < 0.005) and 3.6% (ΔF = 3.869, P < 0.05) to the variance in reading for beginning and intermediate readers, respectively. Phonological awareness, however, did not significantly predict reading performance either at the syllable level or at the onset-rime level, for both groups.

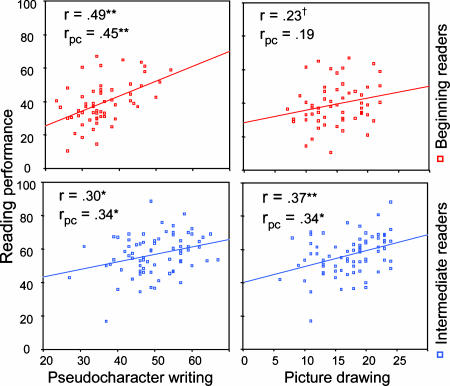

Experiment 2: The Mechanisms Mediating the Effect of Writing on Reading Acquisition. In the next study, the two groups of children were required to perform two tasks: copying samples of printed pseudocharacters and copying simple line objects. Scores from these two tasks were analyzed to determine their relationships with reading performance. Correlation analyses indicated that after the effect of nonverbal IQ was removed, pseudocharacter copying was strongly related to reading ability for beginning readers (r = 0.45, P < 0.001) as well as for intermediate readers (r = 0.34, P < 0.005), whereas object copying was significantly associated with reading acquisition for intermediate readers (r = 0.34, P < 0.005), but not for beginning readers (r = 0.19, P = 0.172) (Fig. 2). Hierarchical multiple regressions show that after nonverbal IQ was controlled, pseudocharacter writing and picture drawing, respectively, explained 18.3% (ΔF = 13.78, P < 0.001) and 3% (ΔF = 1.89, P = 0.175) of variance for beginning readers. In intermediate readers, pseudocharacter writing and picture drawing contributed 11.7% (ΔF = 9.51, P < 0.005) and 10.8% (ΔF = 8.68, P < 0.005) to the variance of reading performance. After the effect of picture drawing was removed, pseudocharacter writing still accounted for 15.4% (ΔF = 11.38, P < 0.001) and 3.6% (ΔF = 2.96, P = 0.09) in the two groups of readers, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Scatter plots of reading performance. rpc, partial correlation. †, P < 0.10; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005.

Discussion

This study was conducted to determine the important diagnostic indicator and predictor of Chinese reading ability. Experiment 1 demonstrated that writing performance was strongly associated with Chinese reading in beginning as well as intermediate readers. The robust and unique predictive power of writing was clearly seen when the effects of general processing speed and phonological awareness were partialed out. Experiment 2 revealed that the contribution of writing to Chinese reading is mediated by at least two mechanisms operating in parallel. One, orthographic awareness, is engaged by the analysis of internal structures of printed characters. This analysis is manifested by the predictive power of character and pseudocharacter writing. The second mechanism, motor programming, serves the formation of long-term motor memory of Chinese characters. The strong association between picture drawing and Chinese reading acquisition, particularly for intermediate readers, provides evidence for the motor programming proposal.

Our motor memory hypothesis is supported by recent neuroimaging studies that found that written Chinese character recognition is critically mediated by the posterior portion of the left middle frontal gyrus, a region just anterior to the premotor cortex (24, 33, 34). In addition, functional connectivity analyses of neural pathways involved in language processing indicated that reading in Chinese recruits a neural circuit linking Broca's area in the prefrontal cortex and the supplementary motor area, whereas reading in alphabetic (Western) scripts recruits a neural circuit connecting Broca's area and Wernicke's area (35). These imaging investigations revealed that the left dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex and premotor cortex, regions for working memory and writing functions (36, 37), are crucially relevant to Chinese reading.

Another important result from this study is that naming speed was strongly related to reading ability, although its predictive power was lower for beginning readers than for intermediate readers. Because naming speed is known to be highly predictive in different types of written language, its contribution to reading development seems to be universal (38). Theoretically, rapid naming may involve several cognitive components such as general processing speed (26), phonological process (39), and speed-sensitive visual and visual motion processes (40). All these componential skills may be relevant to the orthography-to-phonology and orthography-to-semantics mappings that are crucial in the development of Chinese reading (21-23).

Finally, our results indicated that the unique contribution of phonological awareness to Chinese reading ability is minor and fragile, depending on age, grain size of sound units, and their interactions with other factors. Phonological awareness developed earlier at a coarse-grained level (as indexed by the syllable deletion test) than at the fine-grained level (as indexed by the oddity test). When phonological sensitivity was entered in the multiple regression analysis only after nonverbal intelligence was controlled, syllable level awareness predicted reading acquisition across the two reader groups, and subsyllable level awareness was related to reading only in intermediate readers. However, neither syllable level nor subsyllable level phonological awareness predicted Chinese children's reading performance when the variance due to writing and rapid naming was partialed out. This pattern of results suggests that the predictive power of phonological awareness is secondary and complex.

Our findings are important because they challenge the widely assumed universal and preeminent status of phonological awareness in explanations of reading development. In learning to read alphabetic languages, phonological awareness is well known to be highly predictive of children's reading performances. Children's writing (copying) (41, 42) and geometric line drawing skills (13, 41, 42), however, do not predict reading outcomes. For instance, in copying tasks, the performance of disabled English readers (7-15 years of age) in the graphic reproduction of words and letters was equivalent to that of normal readers (41, 42). With similar reproduction tasks, our present study revealed an opposite pattern of findings: in learning to read Chinese, writing skills are clearly more related to reading fluency than is phonological awareness.

In conclusion, the present results indicated that writing, along with naming speed, plays a central role in Chinese reading acquisition. Our results are encouraging with respect to both understanding and remediating Chinese dyslexia. With the two complementary mechanisms of orthographic awareness and motor programming, character writing facilitates and predicts Chinese reading development. Writing and phonological awareness appear to provide two different developmental paths to reading in different languages.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. K. Leong, K. K. Luke, and the teachers of Beijing Yong Tai Elementary school for support and comments. Parts of the study were carried out during L.H.T.'s sabbatical at the National Institute of Mental Health. This study was supported by Hong Kong Government Research Grants Council Central Allocation Vote Grant HKU 3/02C, University of Hong Kong Grant SFPBR-10205790, and National Institute for Child Health and Human Development Grant HD40095.

Abbreviation: RAN, rapid automatized naming.

References

- 1.Chall, J. S. (1967) Learning to Read: The Great Debate (Harcourt Brace, Fort Worth, TX).

- 2.Perfetti, C. A. (1985) Reading Ability (Oxford Univ. Press, New York).

- 3.Vellutino, F. R. & Scanlon, D. M. (1987) Merrill Palmer Q. 33, 321-363. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley, L. & Bryant, P. E. (1983) Nature 301, 419-421. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shankweiler, D. P. & Liberman, I. Y. (1972) in Language by Ear and by Eye: The Relationships between Speech and Reading, eds. Kavanagh, J. F. & Mattingly, I. G. (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA), pp. 293-329.

- 6.Bruck, M. (1992) Dev. Psychol. 28, 874-886. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goswami, U. (1993) J. Exp. Child Psychol. 56, 443-475. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foorman, B. R. & Francis, D. J. (1994) Read. Writ. Interdisc. J. 6, 1-26. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner, R. K., Torgesen, J. K., Rashotte, C., Hecht, S. A., Barker, T. A., Burgess, S. R., Donahue, J. & Garton, T. (1997) Dev. Psychol. 33, 468-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vellutino, F. R., Fletcher, J. M., Snowling, M. J. & Scanlon, D. M. (2004) J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 45, 2-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eden, G. & Moats, L. (2002) Nat. Neurosci. 5, 1080-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Temple, E., Deutsch, G. K., Poldrack, R. A., Miller, S., Tallal, P., Merzenich, M. M. & Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 2860-2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schatschneider, C., Fletcher, J. M., Francis, D. J., Carlson, C. D. & Foorman, B. R. (2004) J. Educ. Psychol. 96, 265-282. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ziegler, J. & Goswami, U. (2005) Psychol. Bull. 131, 3-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho, C. S. H. & Bryant, P. (1997) Dev. Psychol. 33, 946-951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siok, W. T. & Fletcher, P. (2001) Dev. Psychol. 36, 887-899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McBride-Chang, C. & Kail, R. V. (2002) Child Dev. 73, 1392-1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goswami, U. (1999) in Learning to Read and Write: A Cross-Linguistic Perspective, eds. Harris, M. & Hatano, G. (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, U.K.), pp. 134-156.

- 19.Tan, L. H., Hoosain, R. & Siok, W. T. (1996) J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cognit. 22, 865-882. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan, L. H. & Siok, W. T. (2005) in Chinese, Handbook of East Asian Psycholinguistics, eds. Li, P., Tan, L. H., Bates, O. & Tzeng, O. (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, U.K.), Vol. 1, in press.

- 21.Perfetti, C. A., Liu, Y. & Tan, L. H. (2005) Psychol. Rev. 112, 43-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan, L. H. & Perfetti, C. A. (1998) Read. Writ. Interdisc. J. 10, 165-220. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perfetti, C. A. & Tan, L. H. (1998) J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cognit. 24, 101-118. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siok, W. T., Perfetti, C. A., Jin, Z. & Tan, L. H. (2004) Nature 431, 71-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shu, H. (2003) Int. J. Psychol. 38, 274-285. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolf, M. & Bowers, P. G. (1999) J. Educ. Psychol. 91, 415-438. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham, S., Harris, K. & Fink, B. (2000) J. Educ. Psychol. 92, 620-633. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reeve, T. G. & Proctor, R. W. (1983) J. Mot. Behav. 15, 386-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Broussard, D. M. & Kassardjian, C. D. (2004) Learn. Mem. 11, 127-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snyder, P. J. & Harris, L. J. (1993) Cortex 29, 115-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liberman, I. Y. & Shankweiler, D. (1979) in Theory and Practice of Early Reading, eds. Resnick, L. B. & Weaver, P. A. (Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ), Vol. 2, pp. 109-134. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Treiman, R. (1985) J. Exp. Child Psychol. 39, 161-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan, L. H., Spinks, J. A., Feng, C. M., Siok, W. T., Perfetti, C. A., Xiong, J., Fox, P. T. & Gao, J. H. (2003) Hum. Brain Mapp. 18, 158-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan, L. H., Laird, A., Li, K. & Fox, P. T. (2005) Hum. Brain Mapp. 25, 83-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He, A. G., Tan, L. H., Tang, Y., James, A., Wright, P., Eckert, M. A., Fox, P. T. & Liu, Y. J. (2003) Hum. Brain Mapp. 18, 222-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Longcamp, M., Anton, J., Roth, M. & Velay, J. (2003) NeuroImage 19, 1492-1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsuo, K., Kato, K., Okada, T., Moriya, T., Glover, G. H. & Nakai, T. (2003) Cognit. Brain Res. 17, 263-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolf, M. (1999) Ann. Dyslexia 49, 3-28. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torgesen, J. K., Wagner, R. K., Rashotte, C. A., Burgess, S. & Hecht, S. (1997) Sci. Stud. Read. 1, 161-185. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eden, G. & Zeffiro, T. (1998) Neuron 21, 279-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vellutino, F. R., Steger, J. A. & Kandel, G. (1972) Cortex 8, 106-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vellutino, F. R., Smith, H., Steger, J. A. & Kaman, M. (1975) Child Dev. 46, 487-493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]