Abstract

Adhesive type 1 pili from uropathogenic Escherichia coli are filamentous protein complexes that are attached to the assembly platform FimD in the outer membrane. During pilus assembly, FimD binds complexes between the chaperone FimC and type 1 pilus subunits in the periplasm and mediates subunit translocation to the cell surface. Here we report nuclear magnetic resonance and X-ray protein structures of the N-terminal substrate recognition domain of FimD (FimDN) before and after binding of a chaperone–subunit complex. FimDN consists of a flexible N-terminal segment of 24 residues, a structured core with a novel fold, and a C-terminal hinge segment. In the ternary complex, residues 1–24 of FimDN specifically interact with both FimC and the subunit, acting as a sensor for loaded FimC molecules. Together with in vivo complementation studies, we show how this mechanism enables recognition and discrimination of different chaperone–subunit complexes by bacterial pilus assembly platforms.

Keywords: chaperone–usher pathway, Escherichia coli, FimD, protein structure, type 1 pili

Introduction

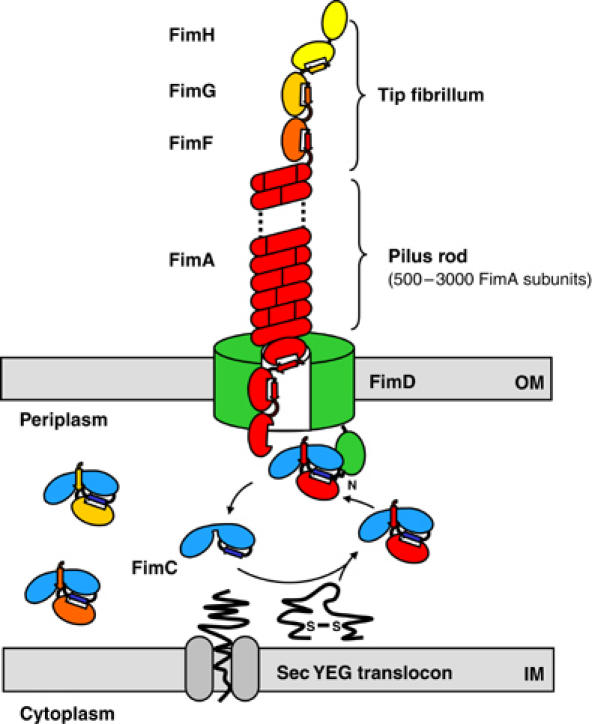

A wide variety of pathogenic bacteria possess adhesive surface organelles (‘pili') that mediate binding to host tissue. These highly oligomeric, filamentous protein complexes are anchored to the outer bacterial membrane (Jones et al, 1995). Type 1 pili from uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains are required for bacterial attachment to mannose units of the glycoprotein receptor uroplakin Ia on the surface of urinary epithelium cells, and thus mediate the first critical step in the infection process (Mulvey et al, 1998; Zhou et al, 2001). In addition, type 1 pili are responsible for bacterial invasion and persistence in target cells (Baorto et al, 1997; Martinez et al, 2000). The quaternary structure of type 1 pili is characterized by a 6.9-nm wide pilus rod consisting of a right-handed, helical array of 500–3000 copies of the most abundant structural subunit FimA, and a linear tip fibrillum composed of the adhesin FimH and several copies of the subunits FimG and FimF (Jones et al, 1995; Hahn et al, 2002) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic model of type 1 pilus assembly by the chaperone–usher pathway. The periplasmic chaperone FimC forms stoichiometric complexes with the newly translocated pilus subunits (FimA, FimG, FimF, FimH). In these complexes, FimC donates its G1 donor strand to the individual subunits, thereby completing the immunoglobulin-like fold of the subunits. FimC–subunit complexes diffuse to the assembly platform (usher) FimD, which specifically recognizes FimC–subunit complexes via its periplasmic, N-terminal segment of residues 1–139. Subsequently, FimC is released to the periplasm, and the subunit is delivered to the translocation pore of FimD, where it is supposed to interact with the previously incorporated subunit via donor strand exchange. The pilus rod, composed of FimA subunits, assembles into its helical quaternary structure on the cell surface. IM, inner membrane; OM, outer membrane.

Biogenesis of type 1 pili is governed by the chaperone–usher pathway (Thanassi and Hultgren, 2000; Sauer et al, 2004). The assembly machinery is composed of two specialized classes of proteins: a periplasmic chaperone and an outer membrane assembly platform, which is also referred to as the usher. The periplasmic type 1 pilus chaperone FimC forms stoichiometric complexes with pilus subunits, catalyzes their folding, and transports them to the assembly platform FimD in the outer membrane (Jones et al, 1993; Vetsch et al, 2004) (Figure 1). The X-ray structure of the FimC–FimH complex (Choudhury et al, 1999) as well as the structures of the related chaperone–subunit complexes PapD–PapK (Sauer et al, 1999), PapD–PapE (Sauer et al, 2002), and Caf1M–Caf1 (Zavialov et al, 2003) have shown that pilus subunits have an incomplete immunoglobulin-like fold that lacks the seventh, C-terminal β-strand (referred to hereafter as ‘pilin fold'). In chaperone–subunit complexes, the missing β-strand is provided by a polypeptide segment of the chaperone, the ‘donor strand', which is inserted parallel to the sixth strand of the subunit (Choudhury et al, 1999; Sauer et al, 1999, 2002; Zavialov et al, 2003). In the assembled pilus, an N-terminal extension of about 15 residues, preceding the pilin fold, acts as the donor strand and complements the pilin fold of the adjacent pilus subunit (Sauer et al, 2002; Zavialov et al, 2003). In this way, each subunit provides its own donor strand to the preceding subunit and accepts a donor strand from the following subunit. In contrast to the chaperone–subunit complexes, the orientation of the inserted donor strand in the pilus is antiparallel to the sixth β-strand of the preceding subunit. Structure comparison of a chaperone-bound subunit and the same subunit in complex with another subunit indicates that a conformational transition of the pilin fold occurs upon exchange of the donor strand during subunit assembly (Sauer et al, 2002; Zavialov et al, 2003). It has been proposed that this conformational change is the driving force for pilus assembly (Sauer et al, 2002; Zavialov et al, 2003). This hypothesis is further supported by the observations that pilus assembly is independent of ATP and of an electrochemical gradient (Jacob-Dubuisson et al, 1994), and that subunit–subunit complexes are thermodynamically more stable than chaperone–subunit complexes (Vetsch et al, 2004).

The type 1 pilus assembly platform FimD is a multifunctional outer membrane protein of 833 residues (Klemm and Christiansen, 1990), which not only anchors the pilus to the cell surface but also recognizes FimC–subunit complexes in the periplasm and mediates translocation of folded subunits through the outer membrane (Saulino et al, 1998, 2000). In spite of the fundamental role of assembly platforms in pilus biogenesis, no structural information on the atomic level is available to date. Based on electron microscopy data on its P pilus homologue PapC, FimD is supposed to form a pore of about 2 nm diameter into the outer membrane (Saulino et al, 2000; Li et al, 2004). This pore size would be wide enough for translocation of individual folded subunits from the periplasm to the cell surface, but not for translocation of the helical pilus rod, which appears to attain its final quaternary structure only on the cell surface (Bullitt and Makowski, 1995).

In a previous study, we showed that FimD possesses an N-terminal periplasmic domain, FimDN, comprising residues 1–139. FimDN is soluble in the absence of detergents, folds autonomously, and specifically binds FimC–subunit complexes with micromolar affinities although FimC or pilus subunits alone are not recognized (Nishiyama et al, 2003). In accordance with these data, the recognition site of chaperone–subunit complexes in PapC was also localized to the N-terminal 124 residues (Ng et al, 2004). Nevertheless, it has been discussed controversially whether the N-terminal chaperone–subunit-binding region of pilus assembly platforms is an independent periplasmic domain (Harms et al, 1999; Nishiyama et al, 2003), or belongs to the porin-like β-barrel transmembrane domain of FimD (Henderson et al, 2004; Ng et al, 2004).

Here we report nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and X-ray protein structures that provide snapshots of the initial step of pilus formation at the site of the assembly platform, that is, the chaperone–subunit recognition domain of an assembly platform before and after binding of a chaperone–subunit complex. The NMR structure of isolated FimDN reveals that this domain consists of a flexible, N-terminal ‘tail' (residues 1–24), a structured ‘core' (residues 25–125) with a novel polypeptide fold, and a potential hinge segment (residues 126–135) that connects the structured core to the transmembrane region of FimD. The most remarkable feature of FimDN is its flexible N-terminal tail, which adopts a defined conformation only upon binding to the complex between FimC and the pilin domain of FimH (FimHP, residues 158–279 of FimH), as revealed by the 1.8 Å crystal structure of the ternary FimDN–FimC–FimHP complex. The structural data, in conjunction with biochemical experiments and in vivo complementation studies, suggest a mechanism in which the assembly platform utilizes its flexible N-terminal segment 1–24 to accomplish specific recognition of different chaperone–subunit complexes.

Results and discussion

The NMR solution structure of free FimDN reveals a previously unknown fold with mobile chain ends

Initial NMR experiments with FimDN(1–139) (residues 1–139 of FimD) showed that this construct is susceptible to N-terminal degradation when incubated for several days at 25°C and at a concentration of 1 mM, most likely due to minute protease contaminations. Edman sequencing and mass spectrometry revealed nonspecific N-terminal degradation of FimDN(1–139) with cleavage after residues Leu9, Ala10, Gln13, and Ser20 (data not shown). Moreover, measurement of [15N,1H]NOEs showed that the segment 1–24 of the polypeptide chain is flexibly disordered (Supplementary Figure S1). We then incubated the ternary complex formed by FimDN(1–139), FimC, and the pilin domain of FimH (FimHP) under identical conditions. In the complex, we observed specific and quantitative cleavage of FimDN(1–139) at a single site close to the C-terminus (Ala125), but no N-terminal degradation was observed. Comparison of the thermal stabilities of FimDN(1–139) and its truncated variants FimDN(25–139) and FimDN(1–125) at pH 7.4, which were monitored by the far-UV circular dichroism signal at 218 nm, showed identical transition midpoints (Tm) of 67.6±0.5°C for all the constructs (Supplementary Table S1). Combined with the aforementioned NMR data, the thermal denaturation data show that the segment 25–125 of FimDN(1–139) adopts a stable tertiary structure, independent of whether or not the terminal chain segments are present.

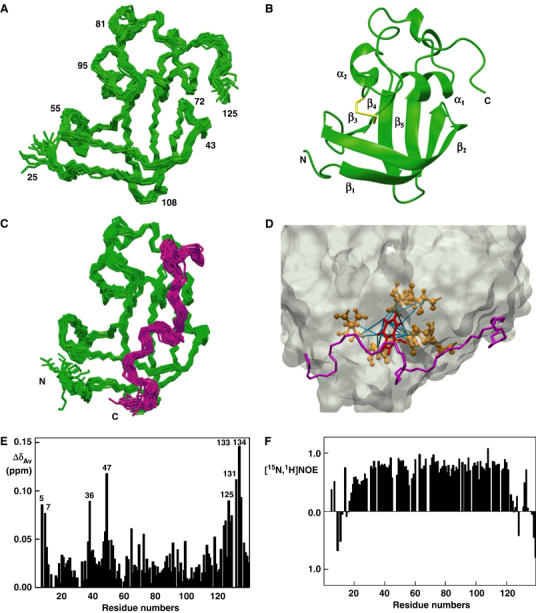

Based on these data, we decided to perform a NMR structure determination of the N- and C-terminally truncated protein fragment FimDN(25–125) (Figure 2A and B; Table I). The scaffold of the tertiary structure is formed by a three-stranded, antiparallel β-sheet (β1–β3) consisting of residues 31–39, 42–53, and 60–62, and a two-stranded, antiparallel β-sheet (β4 and β5) comprising residues 101–105 and 110–114, respectively. The two β-sheets are connected by a peptide segment comprising a single-turn 310-helix (residues 76–78), and the α-helices α1 (residues 66–72) and α2 (residues 93–96). The invariant cysteine pair (Cys63 and Cys90; cf. Figure 4) forms a disulfide bond stabilizing this peptide segment. A second 310-helix (residues 117–119) is located close to the C-terminus. The helices α1 and α2 are packed tightly against the β-sheets, with Met72 of α1 in direct contact with Met44 and Leu39 of β2 and Leu113 of β5, and Leu93 of α2 in contact with Ala102 of β4 and Leu113 of β5. The helices α1 and α2 pack at an angle of 50° to each other, with pronounced hydrophobic interactions between Leu69 and Leu93. A comparison of the structure of FimDN(25–125) with the structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (Berman et al, 2000) using the DALI server (Holm and Sander, 1998) identified no structural homologues. The two structurally most closely related proteins, PDB entries 1SFO and 1T0Y, exhibited Z-scores of 2.1 and 2.0, respectively, with r.m.s.d. values for the Cα atoms of 3.8 and 3.6 Å over 51 and 58 aligned residues, respectively. This shows that FimDN(25–125) represents a previously unknown polypeptide fold. In addition, the NMR data confirm that FimDN(25–125) forms a self-folding periplasmic domain that precedes the transmembrane domain of FimD, and they are in clear-cut contrast with models predicting that the N-terminal region of the assembly platform belongs to the β-barrel transmembrane domain (Henderson et al, 2004; Ng et al, 2004).

Figure 2.

NMR studies on FimDN. (A) Polypeptide backbone of FimDN(25–125) represented by a bundle of 20 energy-minimized DYANA conformers. Selected positions along the polypeptide chain are identified with sequence positions. (B) Ribbon drawing of one of the 20 energy-minimized conformers. β1–β5 and α1–α2 indicate five β-strands and two α-helices, respectively. The disulfide bridge Cys63–Cys90 is drawn in yellow. The chain ends are identified by the letters N and C. (C) NMR structure of FimDN(25–139) represented by a bundle of 20 energy-minimized DYANA conformers showing only the polypeptide backbone. The chain ends are identified by the letters N and C. The C-terminal residues 125–139 are shown in magenta. (D) Close-up view of the surface of one of the 20 energy-minimized conformers of FimDN(25–139). Relative to (C), the structure has been rotated by approximately 90° about a vertical axis. The backbone of the C-terminal stretch 125–139 is drawn in magenta, and the side chain of Trp133 is indicated in red. Those side chains which show long-range NOE connectivities with Trp133 are drawn in bronze. In total, 14 long-range upper-distance limits between Trp133 and the rest of the protein (shown in cyan) define the position of the aromatic ring of Trp133. (E) Chemical shift variations of FimDN upon binding to FimC–FimHP. ΔδAv is the weighted average of the 15N and 1H chemical shifts,  (Pellecchia et al, 1999). (F) Heteronuclear [15N,1H]NOE measurements of FimDN(1–139) in the FimDN–FimC–FimHP ternary complex. Values between 0.5 and 1 indicate well-structured parts of the protein; values<0.5 manifest increased flexibility.

(Pellecchia et al, 1999). (F) Heteronuclear [15N,1H]NOE measurements of FimDN(1–139) in the FimDN–FimC–FimHP ternary complex. Values between 0.5 and 1 indicate well-structured parts of the protein; values<0.5 manifest increased flexibility.

Table 1.

Input for the structure calculation and characterization of the energy-minimized NMR structures of FimDN(25–139) and FimDN(25–125)

| Quantitya | FimDN(25–139) | FimDN(25–125) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOE upper distance limits | 2928 | 2953 | ||||||

| Dihedral angle constraints | 94 | 94 | ||||||

| Residual target function (Å2) | 1.57±0.33 | 1.20±0.43 | ||||||

| Residual NOE violations | ||||||||

| Number ⩾0.1 Å | 31±6 (24–45) | 22±5 (5–29) | ||||||

| Maximum (Å) | 0.14±0.01 (0.12–0.15) | 0.14±0.01 (0.12–0.17) | ||||||

| Residual dihedral angle violations | ||||||||

| Number ⩾2.5 deg | 0±1 (0–2) | 1±1 (0–3) | ||||||

| Maximum (deg) | 1.82±1.12 (0.35–4.54) | 2.89±1.32 (1.57–7.44) | ||||||

| Amber energies (kcal/mol) | ||||||||

| Total | −4323.89±76.56 | −4129.35±55.45 | ||||||

| Van der Waals | −327.64±13.24 | −292.04±16.14 | ||||||

| Electrostatic | −4948.89±74.37 | −4673.08±52.16 | ||||||

| R.m.s.d. from ideal geometry | ||||||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.0078±0.0001 | 0.0079±0.0002 | ||||||

| Bond angles (deg) | 2.035±0.044 | 2.022±0.067 | ||||||

| R.m.s.d. to the mean coordinates (Åb) | ||||||||

| bb (35–120) | 0.43±0.06 (0.33–0.54) | 0.40±0.06 (0.28–0.54) | ||||||

| ha (35–120) | 0.74±0.07 (0.62–0.95) | 0.74±0.06 (0.67–0.90) | ||||||

| Ramachandran plot statisticsc | ||||||||

| Most favored regions (%) | 72 | 71 | ||||||

| Additional allowed regions (%) | 25 | 26 | ||||||

| Generously allowed regions (%) | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Disallowed regions (%) | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| aExcept for the three top entries, the average value for the 20 energy-minimized conformers with the lowest residual DYANA target function values and the standard deviation among them are given. For the residual violations and the r.m.s.d. values, the range from the minimum to the maximum value is given in parentheses. | bbb indicates the backbone atoms N, Cα, Cγ; ha stands for ‘all heavy atoms'. The numbers in parentheses indicate the residues for which the r.m.s.d. was calculated. | cAs determined by PROCHECK (Laskowski et al, 1993). | ||||||

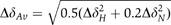

Figure 4.

Multiple sequence alignments of N-terminal domains of assembly platforms (A) and periplasmic chaperones (B). Sequences are identified by their SWISS-PROT IDs. Residue numbering refers to mature FimD (A) and FimC (B). Identical residues are boxed in red, conserved ones are highlighted in yellow. Secondary structure elements derived from the X-ray structure of the ternary complex are shown in green (FimDN(1–125)) and cyan (FimC). Residues of FimDN(1–125) interacting (5.0 Å distance cutoff) with FimC and FimHP are indicated with cyan and yellow triangles, respectively. Residues interacting with both FimC and FimHP are indicated with black triangles. FimC residues involved in contacts (5.0 Å distance cutoff) with FimDN(1–125) are indicated with green triangles. The alignment was generated using CLUSTAL W (Thompson et al, 1994) and displayed with ALSCRIPT (Barton, 1993).

In order to study the role of the segment 126–139, which is supposed to connect FimDN(25–125) to the transmembrane domain of FimD (according to a topology prediction program by Martelli et al (2002), residue 138 is the first residue of a transmembrane β-barrel of FimD), we further solved the NMR structure of FimDN(25–139) (Figure 2C). Except for the additional C-terminal residues, the structure of FimDN(25–139) is in very close agreement with that of FimDN(25–125), with an r.m.s.d. of 1.0 Å for the Cα atoms of the residues 30–120. Interestingly, the segment 126–135 is not disordered in FimDN(25–139), even though it does not adopt a regular secondary structure (Figure 2C). Although the residues 136–139 show negative [15N,1H]NOE values indicative of high-frequency internal motions, those of the residues 121–135 are positive, suggesting rotational tumbling with an effective rotational correlation time similar to that for overall tumbling of the globular domain (Supplementary Figure S1). In addition, we identified a network of long-range NOEs connecting side-chain protons of Trp133 with Val49, Leu64, Thr65, Gln68, and Met72 of the globular domain. These NOEs define a unique position of the aromatic ring of Trp133 in a binding pocket on the surface of the folded domain FimDN(25–125) (Figure 2D). We interpret these observations in terms of a rapid, intramolecular association/dissociation equilibrium between the domain FimDN(25–125) and the segment 126–135. The fact that FimDN(25–139) and FimDN(25–125) have identical Tm values indicates that the C-terminal segment 126–135 dissociates in a spectroscopically silent fashion from the folded core of FimDN, presumably at a temperature below the observed Tm value (Supplementary Table S1). As will be discussed below, there are indications that the intramolecular association/dissociation equilibrium between the domain FimDN(25–125) and the polypeptide segment 126–135 might be related to a spatial rearrangement of residues 1–125 relative to the transmembrane domain of FimD when chaperone–subunit complexes are bound.

X-ray structure determination of the FimDN(1–125)–FimC–FimHP ternary complex

The search for optimal crystallization conditions of a ternary complex between FimDN, FimC, and a bound pilus subunit led us to use protein constructs without disordered segments that might impair crystallization. We therefore investigated the requirement of the flexible segment 1–24 and the C-terminal region 126–139 of FimD for the recognition of FimC–subunit complexes. In addition, we used the C-terminal pilin domain of FimH (FimHP, residues 158–279 of FimH) instead of full-length FimH, because the structure of the FimC–FimH complex (Choudhury et al, 1999) had revealed that FimC interacts exclusively with FimHP. Moreover, the interaction between FimC and FimHP through donor strand complementation is representative for all FimC–pilus subunit complexes (Choudhury et al, 1999), and the lectin domain is not required for recognition of the FimC–FimH complex by FimDN(1–139) (Nishiyama et al, 2003). Taking these facts into account, we tested the ability of the truncated FimDN variants FimDN(12–139), FimDN(25–139), and FimDN(1–125) to bind the FimC–FimHP complex in vitro. Analytical gel filtration revealed that residues 1–24 are strictly required for the formation of the FimDN–FimC–FimHP ternary complex (Figure 5B), although they are disordered in the NMR structure of isolated FimDN(1–139) (Supplementary Figure S1). The requirement of segment 1–24 was confirmed by the observation that deletion of residues 1–12 or residues 1–24 in full-length FimD completely abolished the ability of plasmid-encoded FimD to restore type 1 pilus formation in an E. coli fimD deletion strain (W3110ΔfimD) (Figure 5A). In contrast, residues 126–139 in FimDN are not needed for the formation of the ternary complex in vitro, since the variant FimDN(1–125) exhibits the same affinity towards the FimC–FimHP complex as full-length FimDN(1–139) (Supplementary Table S2).

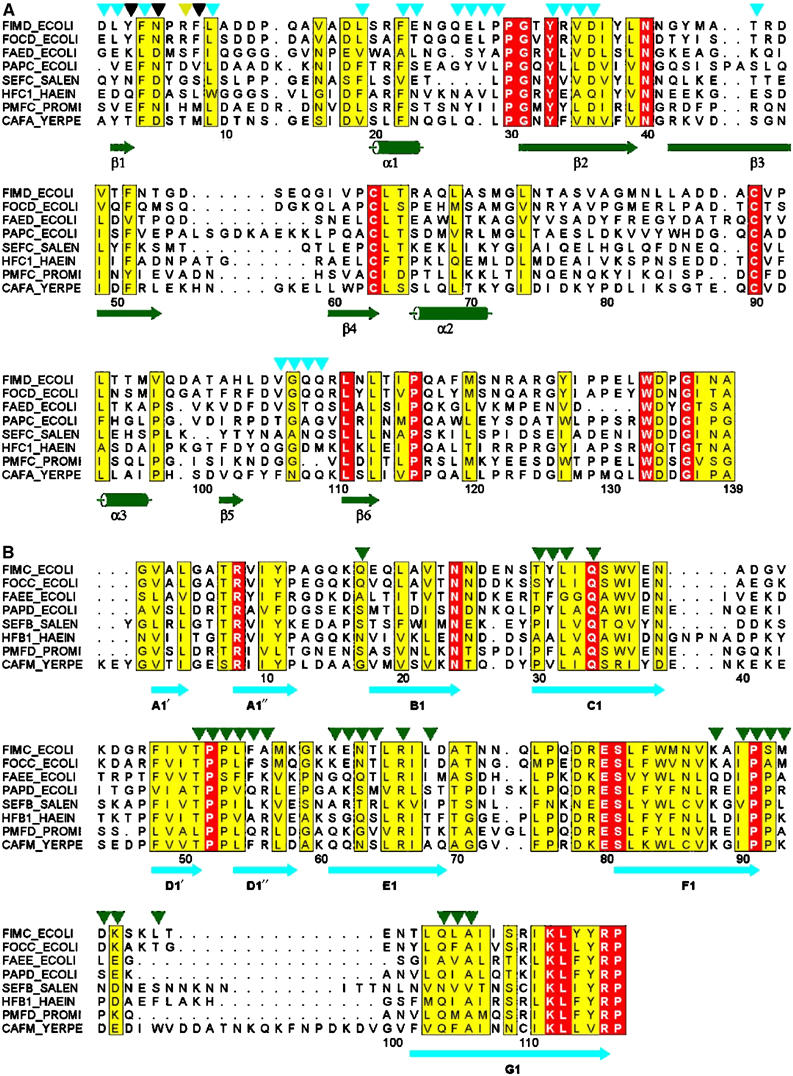

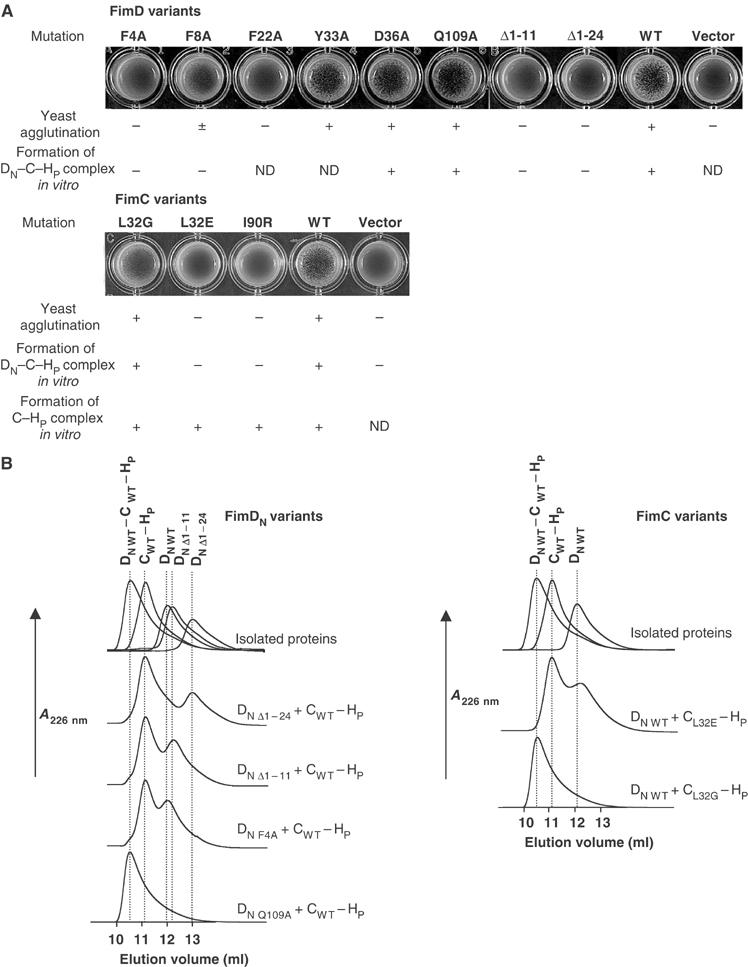

Figure 5.

Analysis of amino-acid replacements and deletions in FimD, FimDN(1–139), and replacements in FimC with respect to type 1 pilus biogenesis in vivo and formation of ternary FimDN(1–139)–FimC–FimHP complexes in vitro. (A) Yeast agglutination assays, probing the formation of functional type 1 pili through agglutination with yeast cells. The E. coli strains W3110ΔfimD and W3110ΔfimC were transformed with expression plasmids carrying the indicated FimD and FimC variants, respectively. Agglutination intensities are indicated as (−) no agglutination, (±) weak or (+) strong. The ability of FimDN(1–139) and FimC variants to form the ternary complex as well as the ability of FimC variants to bind FimHP in vitro are indicated as ‘yes' (+) or ‘no' (–). ND, not determined. (B) Analytical gel filtration at pH 7.4 and 25°C, probing the effect of mutations in FimDN(1–139) or FimC on the formation of the FimDN(1–139)–FimC–FimHP complex.

Based on these results, we crystallized the ternary complex between FimDN(1–125), FimC, and FimHP, and obtained two different crystal forms, A and B, with space groups P63 and P212121, respectively. The structure of the ternary complex was solved with data collected from a single crystal of form B at 1.8 Å resolution through molecular replacement based on the structure of the FimC–FimH complex (Choudhury et al, 1999). Structure refinement resulted in R-factor and free R-factor values of 0.19 and 0.22, respectively (Table II). The final model encompasses residues 1–205 of FimC, residues 158–279 of FimHP, and residues 1–9 and 19–125 of FimDN(1–125) (Figure 3). Residues 10–18 of FimDN(1–125) were not included in the model due to missing electron density. The lack of electron density in this region was confirmed by computation of a simulated-annealing omit map. As the FimDN segment 10–18 is also disordered in the electron density map obtained from crystal form A, the lack of density in this region appears to be an intrinsic property of the FimDN–FimC–FimHP complex. The nature of the structural disorder was further investigated by measurements of heteronuclear [15N,1H]NOEs for FimDN in the ternary complex (Figure 2F), which showed that the effective rotational correlation time of the residues 10–18 is significantly shorter than that for the structured parts of the protein. Interestingly, the residues Asn5 and Arg7 have positive [15N,1H]NOE values, which is an indication that these residues get immobilized upon complex formation.

Table 2.

Summary of crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics

| Data collection | |

| Radiation source | SLS Villigen, CH beamline X06SA |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.900 |

| Space group | P212121 |

| Unit cell | a=54.82 Å, b=83.32 Å, c=110.23 Å |

| Resolution range (Å) | 33.7–1.84 |

| No. of reflections | 284810 |

| No. of unique reflections | 44185 |

| Redundancy | 6.4 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (99.5)a |

| Rsym (%) | 8.8 (36.3)a |

| Average I/σ | 15.0 (3.1)a |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 33.7–1.84 |

| No. of reflections (test) | 44185 (895) |

| No. of atoms | |

| Protein | 3375 |

| Ligands (ethylene glycole) | 48 |

| Water molecules | 510 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |

| Most favored | 92.8 |

| Additional allowed | 7.2 |

| R-factor | 0.190 (0.247)a |

| Free R-factor | 0.216 (0.266)a |

| R.m.s.d. bonds (Å) | 0.005 |

| R.m.s.d. angles (deg) | 1.33 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | 18.8 |

| aLast shell: 1.91–1.84 Å. | |

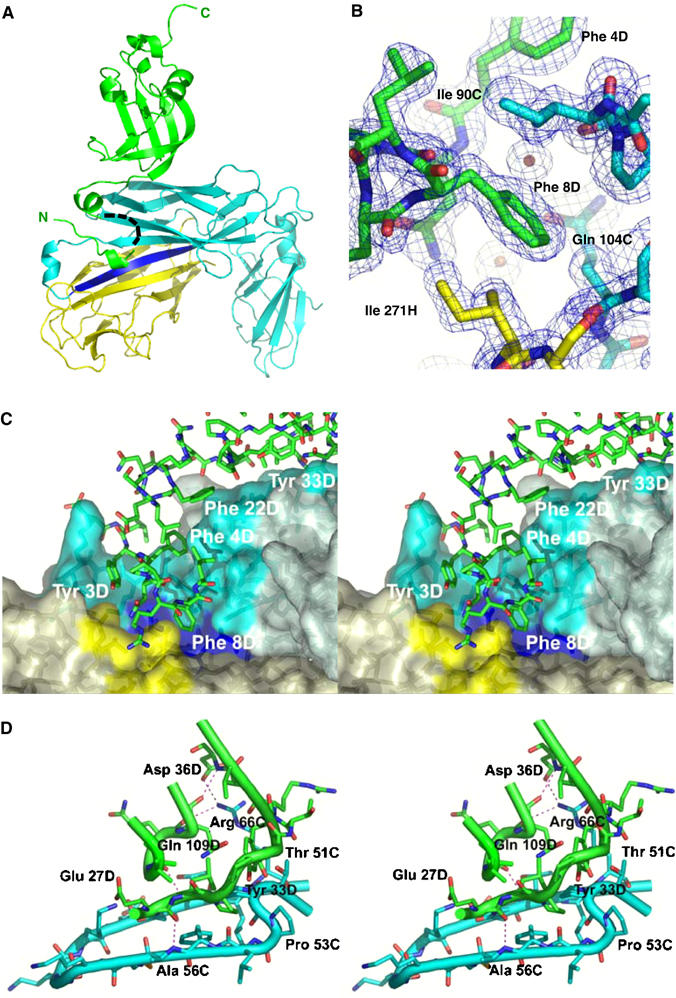

Figure 3.

X-ray structure of the ternary FimDN(1–125)–FimC–FimHP complex. (A) Ribbon diagram of the ternary complex, with FimDN(1–125) depicted in green, FimC in cyan and the pilin domain FimHP in yellow. The G1 donor strand of FimC is colored in blue. A black dashed line indicates residues 10–18 of FimDN, for which no electron density was observed. The N- and C-termini of FimDN are labeled in green. (B) Close-up view of the hydrophobic contacts between Phe8 of the N-terminal FimDN tail (green) and residues from FimC (cyan) and FimHP (yellow). The final 2mFo−DFc electron density map is contoured at 1σ level. (C) Stereo representation of the tail interface. Residues from FimDN, in stick model, are shown in green. The molecular surfaces of FimC (slate-grey) and FimHP (light yellow) are shown in semitransparent mode. Residues contributing to the FimC and FimHP surfaces and interacting with FimDN are shown in more intense color: cyan for FimC and yellow for FimHP residues, respectively. Residues from the G1 donor strand of FimC contributing to the molecular surface appear in blue. (D) Stereo representation of the interface between FimC and the folded FimDN core 25–125. Some hydrogen bonds between FimC and the FimDN core are depicted as thin dashed lines. Color coding is as in (A). The figure was prepared with Pymol (www.pymol.org).

Both the N-terminal tail 1–24 and the structured core 25–125 of FimDN contribute to recognition of FimC–subunit complexes

The crystal structure of the FimDN–FimC–FimHP complex reveals a unique mechanism for recognition of the chaperone–subunit complex by the bacterial pilus assembly platform. FimC interacts via its N-terminal domain (residues 1–116) with both the pilin domain of FimH, through donor strand complementation, and with the globular core of FimDN (residues 25–125). The FimDN core thereby forms no direct contacts with the pilin domain (Figure 3A). Comparison of the NMR structure of isolated FimDN(25–125) and the crystal structure of FimDN(1–125) in the ternary complex reveals that the core of FimDN does not undergo significant conformational changes upon binding to the FimC–FimHP complex (r.m.s.d.=1.2 Å for the Cα atoms of residues 28–121) (Supplementary Figure S2A). Moreover, the structures of FimC and FimHP in the ternary complex are closely similar to those in the previously published FimC–FimH binary complex, with some local differences (see Supplementary data). Importantly, the residues 1–24 of the N-terminal ‘tail', which are completely unstructured in free FimDN, become ordered upon complex formation and specifically interact with both FimC and the bound pilin domain (Figure 3A). The interactions formed by the N-terminal FimDN tail comprise 60% of the total interface area of 1260 Å2 between FimDN(1–125) and the FimC–FimHP complex. The other 40% of the contact area is contributed by the folded core FimDN(25–125), which exhibits a complementary surface to FimC. The total interface area of FimDN(1–125) in the ternary complex is in good agreement with the average value of 1210 Å2 that was calculated for a set of protein–protein complexes with dissociation constants in the micromolar range (Nooren and Thornton, 2003) (KD=1.2 μM for the interaction between FimDN and the FimC–FimHP complex (Nishiyama et al, 2003)).

The N-terminal tail 1–24 of FimDN thus serves as a sensor that selectively detects loaded FimC molecules. As the tail is the only FimDN region that forms contacts with the chaperone-bound subunit, it may be exclusively responsible for the discrimination of the different FimC–subunit complexes by the assembly platform (Saulino et al, 1998). FimD binds to different FimC–subunit complexes with different affinities, which is a key element for correct initiation of pilus assembly and for the correct ordering of the subunit incorporation into the pilus (Saulino et al, 1998; Nishiyama et al, 2003). In the case of the FimC–FimH complex, which is bound by FimD with highest affinity (Saulino et al, 1998), additional contacts between the FimH lectin domain and other FimD regions could contribute to binding, as FimD has been shown to recognize the isolated FimH lectin domain (Barnhart et al, 2003), which is not bound by FimDN (Nishiyama et al, 2003).

The X-ray structure of the FimDN(1–125)–FimC–FimHP complex thus predicts that the common element of the interactions of FimDN with the four different FimC–subunit complexes (Figure 1) is the contact area between the N-terminal FimC domain and the structured domain 25–125 (Figure 3D). This contact area alone is, however, neither sufficient for binding of FimC–subunit complexes to FimDN (cf. Figure 5), nor for stable binding of the free chaperone to the assembly platform (Saulino et al, 1998; Nishiyama et al, 2003). The fact that FimC alone is not bound by FimD ensures that FimC is released to the periplasm for another reaction cycle as soon as the bound subunit dissociates from the ternary complex and is delivered to the translocation pore.

Conserved hydrophobic interactions dominate the recognition of the FimC–FimHP complex by FimDN(1–125)

A striking feature of the N-terminal FimDN tail is the crowding of the three aromatic residues Phe4, Phe8, and Phe22 in the sequence, which make hydrophobic contacts with the FimC–FimHP complex. As shown in Figures 3B and C, Phe8 protrudes deeply into the hydrophobic core of the FimC–FimHP interface and interacts with residues Ile90 and Gln104 of FimC. Specific contacts from FimDN to FimHP are formed to the FimHP residues Gln269 and Ile271 (Figure 3B). The interaction between the globular domain FimDN(25–125) and the N-terminal FimC domain is stabilized by hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds, as well as by a salt bridge between Asp36 of FimDN and Arg66 of FimC (Figure 3D). Sequence alignment shows that the corresponding salt bridge is also present in the PapD–PapC contact area (Arg68 in PapD and Asp35 in PapC), which provides a rationale for the finding that the Arg68 in PapD is required for P pilus biogenesis in vivo (Hung et al, 1999) (see also Figure 4). In addition to specific side-chain contacts, there are also main-chain hydrogen bonds between FimC and the FimDN core (Figure 3D). Furthermore, a hydrophobic cluster is formed by Leu28 and Tyr33 of FimDN and Pro52 of FimC, and Gly107 of FimDN makes hydrophobic contact with Asn63 of FimC. Overall, multiple interactions in the protein–protein interface thus define the specificity of the FimC–FimD contact, making FimC and FimD a functional chaperone/assembly platform pair (Jones et al, 1993).

Biological significance of the recognition of FimC–subunit complexes by FimDN

In order to test the biological significance of the molecular interactions between FimDN and the chaperone–subunit complex observed in the X-ray structure of the FimDN–FimC–FimHP complex, we performed functional tests after replacing individual amino acids in FimD (Phe4Ala, Phe8Ala, Phe22Ala, Tyr33Ala, Asp36Ala, Gln109Ala) or FimC (Leu32Gly, Leu32Glu, Ile90Arg) that form specific contacts in the interface between FimDN and the FimC–FimHP complex (cf. Figure 3). The FimD mutations were first introduced into full-length FimD, and the mutant proteins were tested for their ability to complement FimD deficiency in an E. coli fimD deletion strain through agglutination assays with yeast cells (Mirelman et al, 1980). We then introduced the same mutations into FimDN(1–139), expressed and purified the mutant proteins, and tested them for their ability to form ternary complexes with the FimC–FimHP complex in vitro. Similarly, the FimC variants Leu32Gly, Leu32Glu, and Ile90Arg were analyzed for FimC complementation in the fimC deletion strain W3110ΔfimC, and the corresponding purified variants were tested for formation of a ternary complex with wild-type FimDN(1–139) and FimHP. The results from these experiments are summarized in Figure 5, which shows that all the mutations leading to the loss of formation of the ternary complex in vitro also lead to the complete or partial loss of the formation of functional type 1 pili in vivo (cf. also Supplementary Figure S3A).

The FimC variants Leu32Glu and Ile90Arg completely lost biological activity and no longer formed ternary complexes in vitro (Figure 5), showing that the conserved residues Leu32 and Ile90 are required for recognition of chaperone–subunit complexes by FimDN. Only the FimC variant Leu32Gly was active, which provides a rationale for the fact that residue 32 is either Leu or Gly in the entire chaperone family (cf. Figure 4). All FimC variants retained the ability to form the binary complex with FimHP (Figure 5B), which was expected given the fact that the FimC residue exchanges are located opposite to the subunit-binding site (Figure 3A). In FimD variants, all amino-acid replacements and truncations in the tail 1–24 completely abolished FimD function, although the variant proteins were expressed at the same level as wild-type FimD (Supplementary Figure S3B). These data explain the finding of Ng et al (2004) that alanine substitution of Phe3 in the N-terminal segment of the P pilus assembly platform PapC and deletion of residues 3–12 in FimD or residues 2–11 in PapC abolish pilus biogenesis (cf. also Figure 4). In contrast, the FimD replacements Tyr33Ala, Asp36Ala, and Gln109Ala in the contact area of FimDN(25–125) did not disrupt FimD function in vivo. However, isothermal titration calorimetry showed that the affinity of the corresponding FimDN(1–139) variants for the FimC–FimHP complex was lowered (KD=7.1 and 4.2 μM for the variants Asp36Ala and Gln109Ala, respectively, as compared to 1.2 μM for the wild-type protein; Supplementary Table S2). Overall, the FimD mutagenesis experiments indicate that the contacts formed by the N-terminal FimD tail of residues 1–24 make the dominant energetic contributions to the recognition of chaperone–subunit complexes, and are thus crucial for the function of assembly platforms. In particular, the hydrophobic interactions formed by the aromatic residues Phe4 and Phe22 in the N-terminal tail of FimD are indispensable for ternary complex formation. Intriguingly, the positions 4 and 22 of homologous assembly platforms are strongly conserved (Figure 4).

TROSY-NMR chemical shift mapping indicates a movement of the C-terminal hinge segment of FimDN upon binding of the FimC–FimHP complex

To further analyze the conformational changes associated with the formation of the ternary FimDN–FimC–FimHP complex, we mapped chemical shift variations between isolated FimDN(1–139) and FimDN(1–139) in the ternary complex with [15N,1H]TROSY-NMR, using 15N,2H-labeled FimDN(1–139) and unlabeled FimC–FimHP complex. Figure 2E shows that only eight residues in FimDN(1–139) have [15N,1H]-chemical shift variations, ΔδAv, larger than 0.075, namely Asn5, Arg7, Asp36, Arg47, Arg125, Glu131, Trp133, and Asp134. Large chemical shift changes for Asn5, Arg7, and Asp36 can readily be rationalized by the X-ray structure of the ternary FimDN(1–125)–FimC–FimHP complex, since these residues form specific contacts either with FimC or the FimH pilin domain. The extensive chemical shift changes observed for Arg125, Glu131, Trp133, and Asp134 suggest a movement of the C-terminal hinge segment upon binding of the FimC–FimHP complex. When we modeled the C-terminal hinge segment 126–139 of the NMR structure of FimDN(25–139) into the X-ray structure of the ternary complex, we observed steric clashes between the side chain of Asn138 in FimD and the surface of FimC for all calculated NMR conformers (Supplementary Figure S2B). Particularly significant is the large chemical shift change of Arg47. In the NMR structure of FimDN(25–125) (shown in red in Supplementary Figure S2C) and in the X-ray structure of the ternary complex (shown in green in Supplementary Figure S2C), the side chain of Arg47 adopts a bent conformation. In the X-ray structure and in some of the NMR conformers of FimDN(25–125), the guanidinium group acts as a hydrogen bond donor to the main-chain carbonyl oxygen of Asp48. This conformation of Arg47 is not observed in the NMR structure of FimDN(25–139) (shown in blue in Supplementary Figure S2C), since it would lead to clashes with the residues Pro130, Trp133, and Pro135 of the C-terminal hinge segment. Instead, the side chain of Arg47 protrudes into the bulk solvent (Supplementary Figure S2C). These observations suggest that, upon binding of the FimC–FimHP complex, the side chain of Arg47 is set free to move, and most likely assumes again the hydrogen-bonded conformation observed in the absence of the C-terminal hinge segment (i.e., in the X-ray structure, and in the NMR structure of FimDN(25–125)). Most importantly, the above-mentioned model considerations reveal that FimC and the bound subunit would collide with the hydrophobic part of the outer membrane, if one assumes that the first β-strand of the transmembrane β-barrel of FimD starts with residue 138, as indicated by the topology prediction program described by Martelli et al (2002). Taken together with the observation that segment 126–139 of FimDN(1–139) was proteolytically degraded only when complexed with FimC–FimHP, this observation provides convincing evidence for a model in which a partial or complete displacement of the C-terminal hinge segment of FimDN relative to the folded core (residues 1–125) occurs upon formation of the ternary complex. FimDN(1–139) would thus exist in an ‘open' conformation capable of binding chaperone–subunit complexes, and a ‘closed' conformation in which Trp133 is bound to its pocket on the surface of the FimDN core 25–125. A movement of FimDN(1–139) could also be related to the delivery of pilus subunits to the translocation pore and to the release of the free chaperone to the periplasm for the next assembly cycle.

Concluding remarks

The E. coli type 1 pilus system serves as a prototype for adhesive surface organelles produced by a large number of pathogenic bacteria. The presently described structural studies on FimDN, with and without bound chaperone-subunit complex, shed light on the molecular basis of the initial interaction of the assembly platform with the chaperone–subunit complex. To further elucidate the cascade of reaction steps following this initial binding event, additional biochemical and structural information on the full-length outer membrane assembly platform will be required. Understanding the molecular details of the mode of action of assembly platforms can be expected to provide a basis for the development of novel antimicrobial agents that would block the assembly of the virulence determinants and hence their adhesion to host tissue.

Materials and methods

Plasmids

Mutations corresponding to amino-acid replacements were introduced into the following plasmids, using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). For FimD variants, plasmid pfimDhis was used, which contains the entire fimD gene with a C-terminal hexahistidine tag. This plasmid was generated by cloning the genetic fimD sequence into pBAD30 (Guzman et al, 1995) via the KpnI and HindIII restriction sites. The plasmid pfimC-T7term served as template for mutagenesis of fimC. It contains the fimC gene under the control of the T7 promoter. Amino-acid replacements for in vitro mutagenesis experiments were introduced into the following plasmids: pfimDN (Nishiyama et al, 2003), encoding residues 1–139 of mature FimD, was used as the template for N-terminal FimD constructs, and for the construction of the truncated FimDN variants FimDN(25–139), FimDN(1–125), and FimDN(25–125). pCT–FimH–FimC (Vetsch et al, 2002) was used for mutagenesis of the fimC gene. The nucleotide sequences of all the plasmids used in this study are available upon request.

NMR sample preparation and data collection

13C,15N-labeled FimDN constructs were obtained by growing E. coli strain HM125 carrying the appropriate plasmids in minimal medium containing 13C6-β-glucose and 15NH4Cl as the sole carbon and nitrogen sources, respectively. Uniformly deuterated and 15N-labeled FimDN(1–139) was obtained by growing cells in minimal medium containing 99% 2H2O, 12C6-β-glucose, and 15NH4Cl. All NMR measurements were performed at 20°C and pH 7.0, either on a Bruker DRX 500 spectrometer equipped with a cryogenic probe head, or on Bruker DRX 750 and 900 spectrometers.

For the backbone resonance assignment, the following experiments were recorded: 3D HNCA, 3D HNCACB, 3D CBCA(CO)NH, 3D HNCO, 3D HC(C)H-TOCSY, and 3D HC(C)H-COSY (Wider, 1998). Distance constraints were obtained from three NOE experiments with mixing times of 50 ms, that is, 3D 15N-resolved [1H,1H]NOESY, and two 3D 13C-resolved [1H,1H]NOESY spectra with the 13C carrier frequency in the aliphatic or aromatic regions, respectively. The data sets used for obtaining the sequence-specific resonance assignments were interactively peak picked using the programs XEASY (Bartels et al, 1995) and CARA (R Keller et al, unpublished).

The assignments of the cross-peaks in the 2D [15N,1H]TROSY spectra (Pervushin et al, 1998) of FimDN(1–139) in the ternary complex with FimC and FimHP were obtained in two steps: First, the backbone 15N,1HN chemical shift assignments from free FimDN were mapped onto the 2D [15N,1H]TROSY spectrum of FimDN(1–139) in the complex. Second, the resulting tentative assignments were confirmed by sequential 1HN–1HN connectivities obtained from a 3D 15N-resolved [15N,1H]NOESY spectrum.

Measurements of heteronuclear NOEs were performed at 20°C on a Bruker DRX 750 spectrometer. The NOE spectra and the reference spectra were integrated using XEASY.

NMR structure calculation

The NOESY spectra were automatically analyzed with the new in-house software packages ATNOS (Herrmann et al, 2002b) for automated peak picking and NOE identification in 2D homonuclear and 3D heteronuclear-resolved NOESY spectra, and CANDID (Herrmann et al, 2002a) for automated NOE assignment of NOESY cross-peaks. The program DYANA (Guntert et al, 1997) was used to perform simulated annealing in torsion angle space. The input for ANTOS/CANDID/DYANA consisted of the chemical shifts obtained from the sequence-specific resonance assignment, and of the three aforementioned NOESY spectra. The standard protocol with seven cycles of peak picking, NOE assignment, and 3D structure calculation was applied (Herrmann et al, 2002a, 2002b). During the first six cycles of computation, ambiguous constraints (Nilges, 1997) were used. At the outset of the spectral analysis, highly permissive criteria were used to identify a comprehensive set of peaks in the NOESY spectra, and only the knowledge of the covalent polypeptide structure and the chemical shifts were exploited to guide NOE cross-peak identification and NOE assignment. In the second and subsequent cycles, the intermediate protein three-dimensional structures served as an additional guide for the interpretation of the NOESY data. The output of ANTOS/CANDID/DYANA consisted of assigned NOE peak lists for each input spectrum, and a final set of meaningful upper limit distance constraints that constituted the input for the DYANA 3D structure calculation algorithm. For each cycle of 3D structure calculation, torsion angle constraints for the backbone dihedral angles derived from Cα chemical shifts (Spera and Bax, 1991) were added to the CANDID output. For the final structure calculation in cycle 7, only those distance constraints were retained that could be unambiguously assigned based on the protein three-dimensional structure from cycle 6. The 20 conformers with the lowest residual DYANA target function values obtained from cycle 7 were energy-refined in a water shell with the program OPALp (Luginbuhl et al, 1996; Koradi et al, 2000), using the AMBER force field. The program MOLMOL (Koradi et al, 1996) was used to analyze the protein structure and to prepare the figures of the NMR structures. The atomic coordinates of 20 energy-minimized DYANA conformers each of FimDN(25–125) and FimDN(25–139) have been deposited in the PDB, with entry codes 1ZDX and 1ZDV, respectively.

Crystallization and X-ray structure determination of the ternary complex

FimDN(1–125) and the FimC–FimHP complex were expressed and purified as described (Nishiyama et al, 2003). The ternary complex was obtained by mixing equimolar amounts of FimDN(1–125) and FimC–FimHP, and subsequent purification on a Superdex 75 26/60 size-exclusion column (Amersham Biosciences) equilibrated in 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4), 115 mM NaCl. The homogenous complex was dialyzed against 10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.0) and concentrated. Using the sitting drop vapor diffusion method, we obtained two different crystal forms. Crystals with space group P63 (form A) with three complexes per asymmetric unit were obtained using a reservoir solution containing 0.02 M TAPS/NaOH (pH 9.2) and 18% PEG 5000 MME. Crystals with space group P212121 (form B) with one complex per asymmetric unit were obtained using a reservoir solution containing 0.1 M MES/NaOH (pH 6.5) and 15% PEG 6000.

Diffraction data were collected using synchrotron radiation at the Swiss Light Source and the structure of the ternary complex was solved by molecular replacement with AMoRe (Navaza, 1994) and refined with CNS (Brunger et al, 1998). The data collection and refinement statistics are given in Table II. Details of data collection, structure solution, and refinement are given in Supplementary data. The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the PDB with entry code 1ZE3.

Characterization of FimC and FimD variants

All variants of FimDN were expressed in E. coli strain HM125 and purified as described previously for wild-type FimDN (Nishiyama et al, 2003). Periplasmic expression and purification of complexes between FimC variants and FimHP was carried out as described (Vetsch et al, 2002).

Yeast agglutination assays were performed as previously described (Nishiyama et al, 2003) with E. coli strains W3110ΔfimC and W3110ΔfimD transformed with plasmids encoding the respective wild-type proteins or variants. W3110ΔfimC and W3110ΔfimD were constructed from E. coli K12 wild-type strain W3110 by allelic exchange (Hamilton et al, 1989) and the Red disruption system (Datsenko and Wanner, 2000), respectively.

Analytical gel-filtration experiments were carried out at pH 7.4 and 25°C with initial protein concentrations of 60 μM as described (Nishiyama et al, 2003).

Protein concentrations were determined via the specific protein absorbance at 280 nm.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the beamline X06SA at the Swiss Light Source (Villigen, Switzerland), especially Takashi Tomizaki, for support in X-ray data collection. We are also grateful to Beat Blattmann (University of Zurich) for help in protein crystallization, René Brunisholz (Protein Service Laboratory, ETHZ) for Edman sequencing, and Peter Tittmann for assistance with electron microscopy. MN thanks Kaspar Hollenstein for his valuable comments on the manuscript. This project was funded by the Schweizerische Nationalfonds (grant 3100AO-100787 to RG), the ETH Zurich, and the University of Zurich within the framework of the NCCR Structural Biology program.

References

- Baorto DM, Gao Z, Malaviya R, Dustin ML, van der Merwe A, Lublin DM, Abraham SN (1997) Survival of FimH-expressing enterobacteria in macrophages relies on glycolipid traffic. Nature 389: 636–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnhart MM, Sauer FG, Pinkner JS, Hultgren SJ (2003) Chaperone–subunit–usher interactions required for donor strand exchange during bacterial pilus assembly. J Bacteriol 185: 2723–2730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels C, Xia TH, Billeter M, Guntert P, Wuthrich K (1995) The program XEASY for computer-supported NMR spectral-analysis of biological macromolecules. J Biomol NMR 6: 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton GJ (1993) ALSCRIPT: a tool to format multiple sequence alignments. Protein Eng 6: 37–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE (2000) The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res 28: 235–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL (1998) Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D 54: 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullitt E, Makowski L (1995) Structural polymorphism of bacterial adhesion pili. Nature 373: 164–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury D, Thompson A, Stojanoff V, Langermann S, Pinkner J, Hultgren SJ, Knight SD (1999) X-ray structure of the FimC–FimH chaperone–adhesin complex from uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Science 285: 1061–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko KA, Wanner BL (2000) One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guntert P, Mumenthaler C, Wuthrich K (1997) Torsion angle dynamics for NMR structure calculation with the new program DYANA. J Mol Biol 273: 283–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J (1995) Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J Bacteriol 177: 4121–4130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn E, Wild P, Hermanns U, Sebbel P, Glockshuber R, Haner M, Taschner N, Burkhard P, Aebi U, Muller SA (2002) Exploring the 3D molecular architecture of Escherichia coli type 1 pili. J Mol Biol 323: 845–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton CM, Aldea M, Washburn BK, Babitzke P, Kushner SR (1989) New method for generating deletions and gene replacements in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 171: 4617–4622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms N, Oudhuis WC, Eppens EA, Valent QA, Koster M, Luirink J, Oudega B (1999) Epitope tagging analysis of the outer membrane folding of the molecular usher FaeD involved in K88 fimbriae biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 1: 319–325 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson NS, So SS, Martin C, Kulkarni R, Thanassi DG (2004) Topology of the outer membrane usher PapC determined by site-directed fluorescence labeling. J Biol Chem 279: 53747–53754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann T, Guntert P, Wuthrich K (2002a) Protein NMR structure determination with automated NOE assignment using the new software CANDID and the torsion angle dynamics algorithm DYANA. J Mol Biol 319: 209–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann T, Guntert P, Wuthrich K (2002b) Protein NMR structure determination with automated NOE-identification in the NOESY spectra using the new software ATNOS. J Biomol NMR 24: 171–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L, Sander C (1998) Touring protein fold space with Dali/FSSP. Nucleic Acids Res 26: 316–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung DL, Knight SD, Hultgren SJ (1999) Probing conserved surfaces on PapD. Mol Microbiol 31: 773–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob-Dubuisson F, Striker RT, Hultgren SJ (1994) Chaperone-assisted self-assembly of pili independent of cellular energy. J Biol Chem 269: 12447–12455 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CH, Pinkner JS, Nicholes AV, Slonim LN, Abraham SN, Hultgren SJ (1993) FimC is a periplasmic PapD-like chaperone that directs assembly of type 1 pili in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 8397–8401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CH, Pinkner JS, Roth R, Heuser J, Nicholes AV, Abraham SN, Hultgren SJ (1995) FimH adhesin of type 1 pili is assembled into a fibrillar tip structure in the Enterobacteriaceae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 2081–2085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemm P, Christiansen G (1990) The fimD gene required for cell surface localization of Escherichia coli type 1 fimbriae. Mol Gen Genet 220: 334–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koradi R, Billeter M, Guntert P (2000) Point-centered domain decomposition for parallel molecular dynamics simulation. Comput Phys Commun 124: 139–147 [Google Scholar]

- Koradi R, Billeter M, Wuthrich K (1996) MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J Mol Graph 14: 51–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM (1993) PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structure. J Appl Crystallogr 26: 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Qian L, Chen Z, Thibault D, Liu G, Liu T, Thanassi DG (2004) The outer membrane usher forms a twin-pore secretion complex. J Mol Biol 344: 1397–1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luginbuhl P, Guntert P, Billeter M, Wuthrich K (1996) The new program OPAL for molecular dynamics simulations and energy refinements of biological macromolecules. J Biomol NMR 8: 136–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelli PL, Fariselli P, Krogh A, Casadio R (2002) A sequence-profile-based HMM for predicting and discriminating beta barrel membrane proteins. Bioinformatics 18 (Suppl 1): S46–S53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez JJ, Mulvey MA, Schilling JD, Pinkner JS, Hultgren SJ (2000) Type 1 pilus-mediated bacterial invasion of bladder epithelial cells. EMBO J 19: 2803–2812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirelman D, Altmann G, Eshdat Y (1980) Screening of bacterial isolates for mannose-specific lectin activity by agglutination of yeasts. J Clin Microbiol 11: 328–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey MA, Lopez-Boado YS, Wilson CL, Roth R, Parks WC, Heuser J, Hultgren SJ (1998) Induction and evasion of host defenses by type 1-piliated uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Science 282: 1494–1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaza J (1994) AMoRe: an automated package for molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr A 50: 157–163 [Google Scholar]

- Ng TW, Akman L, Osisami M, Thanassi DG (2004) The usher N terminus is the initial targeting site for chaperone-subunit complexes and participates in subsequent pilus biogenesis events. J Bacteriol 186: 5321–5331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilges M (1997) Ambiguous distance data in the calculation of NMR structures. Fold Des 2: S53–S57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama M, Vetsch M, Puorger C, Jelesarov I, Glockshuber R (2003) Identification and characterization of the chaperone-subunit complex-binding domain from the type 1 pilus assembly platform FimD. J Mol Biol 330: 513–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nooren IM, Thornton JM (2003) Structural characterisation and functional significance of transient protein–protein interactions. J Mol Biol 325: 991–1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellecchia M, Sebbel P, Hermanns U, Wuthrich K, Glockshuber R (1999) Pilus chaperone FimC–adhesin FimH interactions mapped by TROSY-NMR. Nat Struct Biol 6: 336–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pervushin K, Riek R, Wider G, Wüthrich K (1998) Attenuated T2 relaxation by mutual cancellation of dipole–dipole coupling and chemical shift anisotropy indicates an avenue to NMR structures of very large biological macromolecules in solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 12366–12371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer FG, Futterer K, Pinkner JS, Dodson KW, Hultgren SJ, Waksman G (1999) Structural basis of chaperone function and pilus biogenesis. Science 285: 1058–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer FG, Pinkner JS, Waksman G, Hultgren SJ (2002) Chaperone priming of pilus subunits facilitates a topological transition that drives fiber formation. Cell 111: 543–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer FG, Remaut H, Hultgren SJ, Waksman G (2004) Fiber assembly by the chaperone–usher pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta 1694: 259–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saulino ET, Bullitt E, Hultgren SJ (2000) Snapshots of usher-mediated protein secretion and ordered pilus assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 9240–9245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saulino ET, Thanassi DG, Pinkner JS, Hultgren SJ (1998) Ramifications of kinetic partitioning on usher-mediated pilus biogenesis. EMBO J 17: 2177–2185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spera S, Bax A (1991) Empirical correlation between protein backbone conformation and Cα and Cα 13C nuclear magnetic resonance chemical-shifts. J Am Chem Soc 113: 5490–5492 [Google Scholar]

- Thanassi DG, Hultgren SJ (2000) Multiple pathways allow protein secretion across the bacterial outer membrane. Curr Opin Cell Biol 12: 420–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ (1994) CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 22: 4673–4680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetsch M, Puorger C, Spirig T, Grauschopf U, Weber-Ban EU, Glockshuber R (2004) Pilus chaperones represent a new type of protein-folding catalyst. Nature 431: 329–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetsch M, Sebbel P, Glockshuber R (2002) Chaperone-independent folding of type 1 pilus domains. J Mol Biol 322: 827–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wider G (1998) Technical aspects of NMR spectroscopy with biological macromolecules and studies of hydration in solution. Prog NMR Spectrosc 32: 132–275 [Google Scholar]

- Zavialov AV, Berglund J, Pudney AF, Fooks LJ, Ibrahim TM, MacIntyre S, Knight SD (2003) Structure and biogenesis of the capsular F1 antigen from Yersinia pestis: preserved folding energy drives fiber formation. Cell 113: 587–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G, Mo WJ, Sebbel P, Min G, Neubert TA, Glockshuber R, Wu XR, Sun TT, Kong XP (2001) Uroplakin Ia is the urothelial receptor for uropathogenic Escherichia coli: evidence from in vitro FimH binding. J Cell Sci 114: 4095–4103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data