Abstract

Introduction

Early prediction of functional outcome after rtPA helps clinicians in prognostic conversations with stroke patients and their families. Three prognostic tools have been developed in this regard: DRAGON, MRI-DRAGON, and S-TPI scales. These tools, all performing with comparable accuracy, have been internally and externally validated in tertiary care centers. However, their performance in rural areas remains uncertain. This study addresses this gap in the literature by evaluating the effectiveness of those prognostic tools in stroke patients treated in a rural area of the Midwest.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of stroke patients treated with thrombolytics at Southern Illinois Healthcare Stroke Network from July 2017 to June 2024. Data on demographics, clinical presentations, laboratory values, neuroimaging, and stroke metrics were collected. Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) at 1 month, classified into good (mRS ≤2) and poor (mRS ≥5) outcomes were noted. DRAGON and MRI-DRAGON scores were calculated. S-TPI model was built. Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) with its 95% confidence interval was calculated for each prognostic model.

Results

A total of 279 patients were included in this study. Of those, 43% (n = 119) were male. Median age (interquartile range [IQR]) was 69 (57–80) years. NIHSS at presentation (IQR) was 7 (4–13). 12% of the cohort (n = 34) had posterior circulation stroke. At 1 month, 66% of patients (n = 185) had mRS ≤2, whereas 14% of patients (n = 39) had mRS ≥5. MRI-DRAGON showed the highest accuracy in predicting both good (AUC = 0.86, 95% CI: 0.81–0.90) and poor outcomes (AUC = 0.84, 95% CI: 0.76–0.91). DRAGON also demonstrated high accuracy for good (AUC = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.80–0.89) and poor (AUC = 0.82, 95% CI: 0.75–0.90) outcomes. Conversely, in our population, the S-TPI model had the lowest accuracy for good (AUC = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.49–0.63) and poor (AUC = 0.68, 95% CI: 0.61–0.76) outcomes.

Conclusion

Among the available grading scores, MRI-DRAGON score can be considered the more accurate short-term prognostic tool for stroke patients treated with rtPA in the rural setting.

Keywords: Tpa, Rural setting, Acute ischemic stroke, Grading scales, Functional outcome

Introduction

The use of thrombolytic therapy is the standard of care for suspected acute ischemic stroke within 4.5 h from symptom onset recognition [1]. Recently, the indication for thrombolytic therapy has extended to wake-up stroke with DWI-FLAIR mismatch on MRI [2]. When treated with thrombolytic therapy, patients are at least 30 percent more likely to have less disability at 3 months [3]. Two ten-point grading scales have been designed to stratify the likelihood of good and poor outcomes in patients who are eligible to receive thrombolytics: the DRAGON scale and MRI-DRAGON scale [4, 5]. The DRAGON scale encompasses five clinical variables (baseline mRS, age, blood glucose level, symptoms onset-to-treatment time, and NIHSS), and radiographic findings on head CT (hyperdense cerebral artery or early signs of infarct) [4]. A variation of it, called MRI-DRAGON, substituted the CT findings with two findings on MR: occlusion of the first segment of the middle cerebral artery, and presence of ischemia on DWI sequences, quantified based on the ASPECT score [5]. The two scales range from 0 to 10 with an incremental likelihood of poor outcome by point increase. A third tool, called S-TPI, modeled on age, diabetes, stroke severity, sex, previous stroke, systolic blood pressure, and time from symptom onset, was also developed to predict good functional outcomes [6]. Different variables, including age, stroke severity, serum glucose, and ASPECT score were used in the S-TPI model to forecast poor outcomes [6]. To date, the accuracy of those prognostic tools has not been determined in stroke patients treated in the rural setting. The purpose of this study was to assess the performance of the aforementioned scales in a patient population in a rural area of the Midwest.

Methods

Study Design

A retrospective study was designed to evaluate the accuracy of prognostic grading scales in stroke patients treated with thrombolytics at the Southern Illinois Healthcare stroke network between July 2017 and June 2024. Pediatric patients and patients with incomplete electronic medical records were excluded. This study was a subgroup analysis of a larger research project regarding telemedicine in stroke patients, for which ethics approval was obtained from the Local Institutional Review Board of Southern Illinois Healthcare (IRB-24-0040). Written informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Data Collection

Patients were screened in our local stroke registry. Demographics, past medical history, baseline modified Rankin Scale (mRS), clinical presentation including the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), and laboratory values were reviewed. Last-known well-to-treatment time was determined. Pertinent radiographic images were also reviewed: head CT at presentation to determine the presence of hyperdense cerebral artery or early infarct signs; CT angiogram of the head to determine occlusion of the proximal segment of the middle cerebral artery; brain MRI that was obtained within 24 h from the administration of thrombolytics will also be reviewed to determine the presence of DWI changes. ASPECT score was calculated for both CT and MRI [7]. Each neuroimaging was independently reviewed by lead research members (A.L., Jo.H., A.H.) to assess intra- and interobserver agreements.

Grading Scales

Three grading scales were investigated: DRAGON, MRI-DRAGON, and S-TPI. DRAGON and MRI-DRAGON scales were calculated for each patient [4, 5]. S-TPI model was built for both good outcomes (age, diabetes, stroke severity, sex, previous stroke, systolic blood pressure, and time from symptom onset) and poor outcome (age, stroke severity, serum glucose, and ASPECT score) based on the variables from its original study [6]. Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) from each original study, in the derivation and validation cohorts, for good and poor outcomes were reviewed.

Outcome Metric

The outcome measure was determined as mRS at 1 month after the ischemic event [8]. The outcome was dichotomized into good outcome (mRS ≤2) and poor outcome (mRS ≥5).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented as means with standard deviations (SD) or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables and as percentages for categorical variables. In univariate analyses, categorical variables were compared by Fisher’s exact test or Chi Square test, and continuous variables were compared by t test or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. The sensitivity and specificity of the grading scales for each predetermined outcome were computed and expressed in percentage. Logistic regression analyses were computed for each predetermined outcome, and AUC with its 95% confidence interval was calculated as a measure of the predictive ability of each prognostic model. The significance level for all statistical analyses was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were computed with the statistical software R version 4.4.0.

Results

General Characteristics of the Cohort

The characteristics of the cohort are summarized in Table 1. A total of 279 patients were included in the study. Median age (IQR) was 69 (57–80) years. 43% of the subjects (n = 119) were male. Median last known well to treatment (IQR) was 128 (91–180). Median NIHSS (IQR) was 7 (4–13). 10% of patients (n = 28) underwent mechanical thrombectomy. Stroke in the posterior circulation was 12% of the cohort (n = 34). At 1 month, mRS ≤2 was observed in 66% of patients (n = 185), whereas mRS ≥5 in 14% of patients (n = 39).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the cohort

| Variable | Cohort (n = 279) |

|---|---|

| Demographics and baseline characteristics of the cohort | |

| Age (IQR), years | 69 (57–80) |

| Male, n (%) | 119 (43) |

| White, n (%) | 253 (91) |

| BMI (IQR) | 30 (25–34) |

| History of HTN, n (%) | 213 (76) |

| History of DM, n (%) | 83 (70) |

| History of stroke, n (%) | 53 (19) |

| History of cardiac disease, n (%) | 98 (35) |

| History of CKD, n (%) | 37 (13) |

| Baseline mRS (IQR) | 0 (0–0) |

| PTA antithrombotics, n (%) | 95 (34) |

| Evaluation and stroke metrics | |

| Nighttime 7 p.m.–7 a.m., n (%) | 87 (31) |

| Initial GCS (IQR) | 15 (13–15) |

| Initial NIHSS (IQR) | 7 (4–13) |

| Initial SBP (IQR), mm Hg | 157 (136–173) |

| Initial glucose (IQR), mg/dL | 114 (99–149) |

| Last known well to treatment (IQR), min | 128 (91–180) |

| Door to needle time (IQR), min | 51 (39–69) |

| ASPECT score (IQR) | 10 (10–10) |

| Hyperdense MCA sign, n (%) | 30 (11) |

| M1 occlusion on CTA, n (%) | 36 (13) |

| tPA complications, n (%) | |

| Symptomatic ICH | 8 (3) |

| Systemic bleeding | 7 (2.5) |

| Allergy/angioedema | 3 (1) |

| Thrombectomy | 28 (10) |

| Posterior circulation stroke | 34 (12) |

| Outcome measures | |

| Median LOS (IQR) | 3 (2–5) |

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 19 (7) |

| Discharge home or inpatient rehab, n (%) | 233 (83) |

| mRS 0–2 at 30 days, n (%) | 185 (66) |

| mRS 5–6 at 30 days, n (%) | 39 (14) |

Clinical and Radiographic Variables

The variables that comprise the three grading scales were compared in univariate analyses for good outcome (mRS ≤2) and poor outcome (mRS ≥5) and are presented in Table 2. Radiographic variables, including dense cerebral artery signs, early infarct signs on CT scan, presence of M1 occlusion, DWI ASPECT score ≤5, and ASPECT score were significantly different for good and poor outcomes, p value <0.01 for all. Median age and NIHSS were also significantly different among the groups, p value <0.01.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis for good outcome (mRS ≤2), first p value, and poor outcome (mRS ≥5), second p value relative to the variables that comprise the grading scales

| mRS ≤2 (n = 186) | mRS >2 (n = 93) | p value | mRS <5 (n = 238) | mRS ≥5 (n = 41) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRAGON variables | ||||||

| Dense cerebral artery sign | 5 (3) | 25 (27) | <0.01 | 13 (6) | 17 (42) | <0.01 |

| Early infarct signs on admission CT scan | 8 (4) | 20 (22) | <0.01 | 17 (7) | 11 (27) | <0.01 |

| Prestroke mRS >1 | 1 (1) | 27 (29) | <0.01 | 14 (6) | 14 (34) | <0.01 |

| Age | ||||||

| ≥80 | 31 (17) | 39 (42) | <0.01 | 49 (21) | 21 (51) | <0.01 |

| 65–79 | 61 (33) | 34 (36) | 0.532 | 82 (34) | 13 (32) | 0.732 |

| <65 | 94 (50) | 20 (22) | <0.01 | 107 (45) | 7 (17) | <0.01 |

| Glucose level at baseline >144 mg/dL | 44 (24) | 27 (29) | 0.331 | 56 (24) | 15 (37) | 0.076 |

| Onset-to-treatment time >90 min | 140 (76) | 74 (81) | 0.291 | 181 (76) | 33 (85) | 0.253 |

| NIHSS | ||||||

| >15 | 16 (9) | 34 (37) | <0.01 | 31 (13) | 19 (46) | <0.01 |

| 10–15 | 25 (13) | 19 (20) | 0.426 | 37 (16) | 7 (19) | 0.804 |

| 5–9 | 69 (37) | 30 (32) | 0.131 | 91 (38) | 8 (19) | 0.021 |

| 0–4 | 76 (41) | 10 (11) | <0.01 | 79 (33) | 7 (19) | 0.039 |

| MRI-DRAGON additional variables | ||||||

| M1 occlusion | 7 (4) | 29 (31) | <0.01 | 20 (8) | 16 (39) | <0.01 |

| DWI ASPECTS ≤5 | 0 (0) | 29 (32) | <0.01 | 7 (3) | 22 (55) | <0.01 |

| S-TPI variables | ||||||

| Median age (IQR), years | 64 (51–74) | 78 (66–87) | <0.01 | 66 (55–78) | 80 (69–90) | <0.01 |

| Male, n (%) | 82 (44) | 37 (40) | 0.493 | – | – | – |

| History of diabetes, n (%) | 54 (29) | 29 (32) | 0.628 | – | – | – |

| History of stroke, n (%) | 33 (18) | 20 (22) | 0.45 | – | – | – |

| Median NIHSS (IQR) | 6 (3–9) | 13 (7–18) | <0.01 | 6 (4–11) | 15 (7–19) | <0.01 |

| Median SBP (IQR), mm Hg | 157 (137–174) | 155 (131–165) | 0.173 | – | – | – |

| Median onset-to-treatment (IQR), min | 128 (89–181) | 125 (95–175) | 0.964 | – | – | – |

| Median glucose (IQR), mg/dL | – | – | – | 115 (100–141) | 117 (96–162) | 0.517 |

| Median ASPECTS (IQR) | – | – | – | 10 (10–10) | 10 (9–10) | <0.01 |

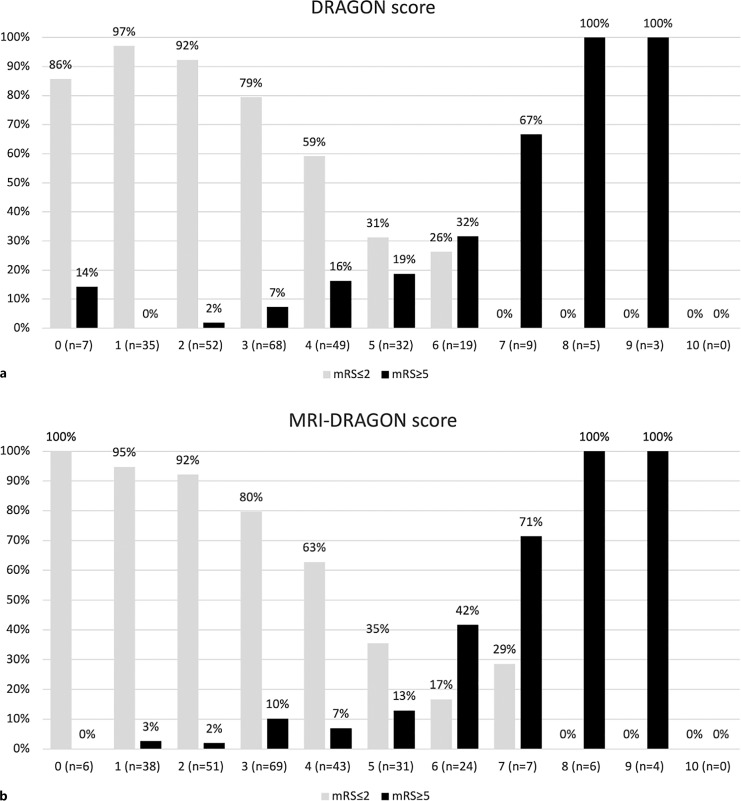

DRAGON and MRI-DRAGON Scales

DRAGON score and MRI-DRAGON score were computed for each patient, reported in percentage, and plotted against good outcome and bad outcome (Fig. 1a, b). No patient had a score of 10.

Fig. 1.

a DRAGON score by outcome. b MRI-DRAGON score by outcome.

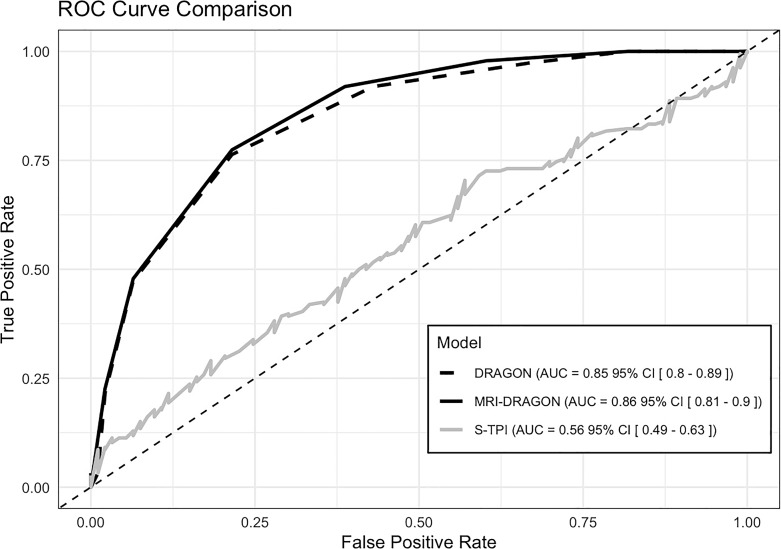

Accuracy of Prognostic Scales for Good Functional Outcome

Receiver operating characteristic curve for each model was computed and is graphed in Figure 2. MRI-DRAGON score performed with an AUC = 0.86 (95% CI: 0.81–0.90), DRAGON score had an AUC = 0.85 (95% CI: 0.80–0.89), whereas S-TPI had an AUC = 0.56 (95% CI: 0.49–0.63). Both MRI-DRAGON and DRAGON scores were significantly more accurate in predicting good functional outcome compared to S-TPI model, p < 0.01 for both. There was no statistical difference between the accuracy of MRI-DRAGON and DRAGON scores, p = 0.147.

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curve for good outcome (mRS ≤2).

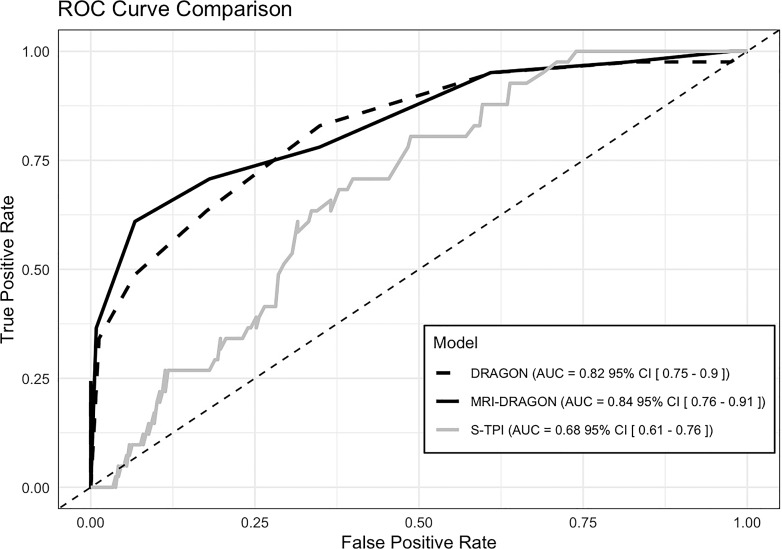

Accuracy of Prognostic Scales for Poor Functional Outcome

Receiver operating characteristic curve for each model was computed and is graphed in Figure 3. MRI-DRAGON score performed with AUC = 0.84 (95% CI: 0.76–0.91), DRAGON score had an AUC = 0.82 (95% CI: 0.75–0.90), whereas S-TPI had an AUC = 0.68 (95% CI: 0.61–0.76). Both MRI-DRAGON and DRAGON scores were significantly more accurate in predicting good functional outcomes compared to the S-TPI model, p < 0.01 for both. There was no statistical difference between the accuracy of MRI-DRAGON and DRAGON scores, p = 0.268.

Fig. 3.

Receiver operating characteristic curve for poor outcome (mRS ≥5).

Comparison of Prognostic Scales against Their Original Performance

Compared to the original study, MRI-DRAGON had a similar AUC for poor outcomes 0.84 (0.76–0.91) versus 0.83 (0.78–0.88). The AUC of S-TPI was lower compared to its original study for both good outcome 0.56 (0.49–0.63) versus 0.793 (0.786–0.799) and poor outcome 0.68 (0.61–0.76) versus 0.784 (0.774–0.794) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Area under the curve for each grading scale in its original study and in the current study

| Scale | Sample size original cohort | AUC – derivation original study (95% CI) | AUC – validation original study (95% CI) | Sample size current study | AUC – current study (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good outcome (mRS ≤2) | |||||

| DRAGON | 1,319 | – | – | 279 | 0.85 (0.80–0.89) |

| MRI-DRAGON | 228 | – | – | 279 | 0.86 (0.81–0.90) |

| S-TPI | 2,184 | 0.793 (0.786–0.799) | 0.772 (0.763–0.782) | 279 | 0.56 (0.49–0.63) |

| Poor outcome (mRS ≥5) | |||||

| DRAGON | 1,319 | 0.84 (0.80–0.87) | 0.80 (0.74–0.86) | 279 | 0.82 (0.75–0.90) |

| MRI-DRAGON | 228 | 0.83 (0.78–0.88) | – | 279 | 0.84 (0.76–0.91) |

| S-TPI | 2,184 | 0.784 (0.774–0.794) | 0.762 (0.749–0.776) | 279 | 0.68 (0.61–0.76) |

Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated the performance of three prognostic grading scales in stroke and we found that MRI-DRAGON was the most accurate prognostic tool to predict good and poor outcome in patients who receive rtPA. The availability of accurate and reliable grading scales that predict which patients have the higher likelihood of benefiting the most or the least from thrombolytic therapy is much needed in clinical practice as an aiding tool in the discussion with patients and family regarding the benefits of thrombolytics, as well as guiding the prognostic conversation and setting reliable expectations regarding the short-term outcome.

Three grading tools were developed over the last decade that took into consideration a combination of clinical, laboratoristic, and radiographic variables: DRAGON score, MRI-DRAGON score, and S-TPI model. Those tools, all performing with comparable accuracy, were internally and externally validated in large tertiary care centers [9–13]. However, their performance in rural areas remained uncertain. In this work, we tackle this gap in the literature.

Some considerations need to be made regarding the MRI-DRAGON tool. This tool utilizes MRI and MRA as first-line imaging before thrombolytic therapy is administered. The ten-point score takes into account DWI changes on MRI and occlusion of M1 segment on MRA. The availability of resources in the rural setting is scarce, especially regarding the accessibility of advanced neuroimaging in the emergency department. A dedicated and continuously operating MRI scanner for acute stroke in the emergency department is a luxury that only larger institutions can afford. In rural areas, when available, MRI and MR angiogram are usually obtained once the patient is admitted to the hospital. Moreover, as a practical consideration, obtaining MRI/MRA before thrombolytics can significantly delay the administration of rtPA. For all of the above reasons, in our external validatory study we applied two variations to the MRI-DRAGON model. First, the occlusion of M1 segment was determined on CT angiogram that, per internal protocol, was obtained immediately after administration of rtPA. Second, the DWI changes on MRI were considered within 24 h after administration of thrombolytics. In the face of these two adjustments, MRI-DRAGON maintained an excellent performance in the rural setting for both good outcome, AUC = 0.86 (95% CI: 0.81–0.90), and poor outcome, AUC = 0.84 (95% CI: 0.76–0.91).

DRAGON score performed with high accuracy in predicting poor short-term outcome AUC = 0.82 (95% CI: 0.75–0.90), albeit inferior compared to MRI-DRAGON score. DRAGON score retains a highly important value in the rural setting as it can offer an accurate prognostic tool in those centers where MRI is not always available.

In our population, the S-TPI model performed poorly in both predicting poor outcome AUC = 0.68 (95% CI: 0.61–0.76) and good outcome AUC = 0.56 (95% CI: 0.49–0.63). Its applicability in the rural setting is uncertain at this time and its use could be reserved for when it is not feasible to use the former two grading scales.

Noticeably, several changes in stroke care occurred after the development of all those prognostic scales, including the extension of the time window for thrombolytics and thrombectomy, the introduction of thrombolytic therapy for wake-up stroke, and transition from alteplase to tenecteplase [1, 2, 14]. In this landscape, some of the variables that were considered in the original grading scales have modified their clinical relevance. Onset of symptoms to treatment (OTT) has intrinsically increased in recent years because of the above consideration regarding the extension of the therapeutic window for thrombolytic therapy up to 4.5 h from the last known well. S-TPI considered OTT a continuous variable; hence, the decrease in its accuracy could be at least partially attributed to it. On the other hand, DRAGON and MRI-DRAGON scores used a dichotomous outcome of OTT >90 min, retaining prognostic accuracy. The second relevant variable that merits consideration is the occlusion of M1 segment. DRAGON and MRI-DRAGON scores preceded the landmark MR CLEAN and SWIFT PRIME studies that proved better functional outcomes at 90 days in patients with large vessel occlusion treated with thrombectomy within 6 h [15, 16]. Data regarding thrombectomy is not available for both DRAGON and MRI-DRAGON studies, but it is reasonable to conclude that at least some of their patients with evidence of M1 occlusion did not undergo recanalization, based on standard clinical practice over 10 years ago. Despite this, the accuracy of both scales has not appeared to be affected by it. Another important factor influencing the accuracy of the S-TPI model is the inclusion of variables related to prior stroke and diabetes. The difference in cerebrovascular risk factors and incidence of stroke in rural areas is not only higher compared to urban areas, but the gap has also been widening throughout the years [17, 18]. This further explains the lack of accuracy of the S-TPI model in rural populations.

Finally, our study was meant to be a pragmatic validation of the grading scales, reflecting a real-world experience of stroke care in the rural setting. Deliberately, our inclusion criteria were very wide and posterior circulation strokes were also included. Notwithstanding an obvious bias in the lack of validity of ASPECT score for posterior circulation stroke, retaining these patients maintained an excellent prognostic accuracy for both DRAGON and MRI-DRAGON scores. The decision to include posterior circulation stroke is also based on the fact that the greatest utility of a prediction model occurs before the thrombolytics are administered, in order to aid the decision-making process of thrombolytic administration with the patient and family regarding projected functional outcome. In that scenario, the location of the cerebrovascular lesion is not yet determined, hence our choice to include all patients who receive thrombolytics in our study.

In conclusion, among the available grading scores, the MRI-DRAGON score can be considered the more accurate short-term prognostic tool for stroke patients treated with rtPA in the rural setting. As the care of acute stroke patients changes, other clinical and radiographic variables, such as laboratory biomarkers and CT perfusion data, could become relevant in forecasting short-term outcomes after rtPA. Established prognostic tools should be updated, and newer ones developed in order to aid clinicians who practice in all settings, including rural areas, in guiding prognostic conversations with patients and their families. The novelty of our work lies in the applicability of existing prognostic tools in rural populations and lays the groundwork for improving those models and developing new ones that take into account advancements in technology and clinical practice for acute stroke care.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First and foremost, it is a single-center retrospective study, with the intrinsic biases that this type of study design naturally has. Second, the short-term outcome considered in this study was mRS at 1 month, which differed from the 3-month mRS outcome for which the three grading scales were originally built. This difference may have affected the comparability of our study with the original ones. The choice of the short-term outcome was limited by our dataset. Finally, our results are restricted to rural population of the Midwest, and they may not be generalizable to different patient populations.

Conclusion

Among the available grading scores, MRI-DRAGON score can be considered the more accurate short-term prognostic tool for stroke patients treated with rtPA in the rural setting. As the care of acute stroke patients changes, prognostic tools should be updated and newer ones developed to aid clinicians in guiding prognostic conversations with patients and their families.

Statement of Ethics

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Local Institutional Review Board of Southern Illinois Healthcare (IRB-24-0040). The need for written informed consent was waived by the Local Institutional Review Board of Southern Illinois Healthcare.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None of the authors has any conflict of interest or financial disclosures to declare.

Funding Sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions

A.L. was responsible for study concept, study design, data collection, data analysis, and drafting the manuscript. Je.H. was responsible for data collection. J.W. was responsible for data collection and editing the manuscript. F.S.V., Jo.H., and A.H. were responsible for study concept, study design, editing the manuscript, and approving the final version of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants but are available from the corresponding author (A.L.) upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50(12):e344–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thomalla G, Simonsen CZ, Boutitie F, Andersen G, Berthezene Y, Cheng B, et al. MRI-guided thrombolysis for stroke with unknown time of onset. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(7):611–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group . Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(24):1581–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Strbian D, Meretoja A, Ahlhelm FJ, Pitkäniemi J, Lyrer P, Kaste M, et al. Predicting outcome of IV thrombolysis-treated ischemic stroke patients: the DRAGON score. Neurology. 2012;78(6):427–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Turc G, Apoil M, Naggara O, Calvet D, Lamy C, Tataru AM, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-DRAGON score: 3-month outcome prediction after intravenous thrombolysis for anterior circulation stroke. Stroke. 2013;44(5):1323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kent DM, Selker HP, Ruthazer R, Bluhmki E, Hacke W. The stroke-thrombolytic predictive instrument: a predictive instrument for intravenous thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2006;37(12):2957–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pexman JH, Barber PA, Hill MD, Sevick RJ, Demchuk AM, Hudon ME, et al. Use of the alberta stroke program early CT score (ASPECTS) for assessing CT scans in patients with acute stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(8):1534–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Saver JL, Chaisinanunkul N, Campbell BCV, Grotta JC, Hill MD, Khatri P, et al. Standardized nomenclature for modified Rankin scale global disability outcomes: consensus recommendations from stroke therapy academic industry roundtable XI. Stroke. 2021;52(9):3054–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ntaios G, Gioulekas F, Papavasileiou V, Strbian D, Michel P. ASTRAL, DRAGON and SEDAN scores predict stroke outcome more accurately than physicians. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23(11):1651–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ovesen C, Christensen A, Nielsen JK, Christensen H. External validation of the ability of the DRAGON score to predict outcome after thrombolysis treatment. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20(11):1635–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Giralt-Steinhauer E, Rodríguez-Campello A, Cuadrado-Godia E, Ois Á, Jiménez-Conde J, Soriano-Tárraga C, et al. External validation of the DRAGON score in an elderly Spanish population: prediction of stroke prognosis after IV thrombolysis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;36(2):110–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang A, Pednekar N, Lehrer R, Todo A, Sahni R, Marks S, et al. DRAGON score predicts functional outcomes in acute ischemic stroke patients receiving both intravenous tissue plasminogen activator and endovascular therapy. Surg Neurol Int. 2017;8:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang X, Liao X, Wang C, Liu L, Wang C, Zhao X, et al. Validation of the DRAGON score in a Chinese population to predict functional outcome of intravenous thrombolysis-treated stroke patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24(8):1755–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Warach SJ, Dula AN, Milling TJ. Tenecteplase thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2020;51(11):3440–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, Diener H-C, Levy EI, Pereira VM, et al. Stent-retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA alone in stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(24):2285–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Berkhemer OA, Fransen PSS, Beumer D, van den Berg LA, Lingsma HF, Yoo AJ, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(1):11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Howard G. Rural-urban differences in stroke risk. Prev Med. 2021;152(Pt 2):106661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kapral MK, Austin PC, Jeyakumar G, Hall R, Chu A, Khan AM, et al. Rural-urban differences in stroke risk factors, incidence, and mortality in people with and without prior stroke: the CANHEART stroke study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(2):e004973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants but are available from the corresponding author (A.L.) upon reasonable request.