Abstract

Background and Objectives

A quarter of ischemic strokes are of lacunar clinical subtype and have an underlying recent small subcortical infarct (RSSI), but their long-term outcomes remain poorly characterized. Hemosiderin deposits (HDs) have been noted in RSSIs at chronic stages and might mimic primary hemorrhage. We characterized HDs' morphology, frequency, and clinical relevance.

Methods

Participants with RSSIs were identified from a prospective longitudinal study and evaluated on 3T MRI including susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) from stroke diagnosis to 12 months. We categorized HDs in RSSIs on SWI at all available time points into 4 types (spots, smudge, rim, cluster) and assessed their associations with demographic factors, stroke-related factors, and image markers with adjusted logistic regression.

Results

HDs were observed in 43 (55.0%) of 108 participants within 3 months and 83 (76.9%) of 108 within 12 months after stroke onset. The mean time to first detection of HDs was 87 (interquartile range 53–164) days. A “rim” pattern (similar to late appearance of primary hemorrhage) occurred in at least 26.5% of RSSIs at all follow-up time points, mainly those located in the lentiform/internal capsule (50.0%) or thalamus (36.4%). Infarct volume (odds ratio [OR] 1.003, 95% CI 1.001–1.006; p = 0.004) and the total small vessel disease (SVD) score at baseline (OR 2.50, 95% CI 1.28–4.86, p = 0.007) independently predicted HDs at 12 months. HDs were positively associated with more lacunes (OR 1.60, 95% CI 1.13–2.26, p < 0.01), but not the Fazekas score, number of microbleeds, basal ganglia mineral deposit score, or clinical outcomes.

Discussion

HDs occur commonly in RSSIs and may be associated with infarct volume and SVD score. Hemosiderin “rim” is common in RSSIs, urging caution to avoid mistaking ischemic RSSI for primary hemorrhage in subacute and chronic stages.

Introduction

Recent small subcortical infarcts (RSSIs), also known as lacunar ischemic strokes, account for approximately 25% of ischemic strokes.1-3 The long-term evolution of RSSIs is not fully understood. Previous studies suggest that RSSIs could undergo various long-term transformations seen on brain imaging with MRI or CT scanning, including partial or complete cavitation (lacune formation), remaining hyperintense on MRI or hypointense on CT, thus resembling a white matter hyperintensity (WMH), or even disappearing.4-6

Recently, with increasing use of 3T MRI scanners and blood-sensitive sequences such as susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI), new features indicating hemosiderin deposition have been reported during the long-term evolution of RSSIs. These features appear as “rim” or “smudge” patterns.3 One study identified hemosiderin foci in 10% of RSSIs during long-term follow-up MRI (mean time 33.5 months), suggesting it might represent hemorrhagic transformation.7 Another study found that hemorrhagic foci occurred in 44.6% of RSSIs on SWI at approximately 12 months (median 449 days) after stroke.8 We noted similar hemosiderin deposits (HDs) in RSSIs during follow-up in a longitudinal study of participants with lacunar ischemic stroke, the Mild Stroke Study 3 (MSS3).9 However, the morphology, prevalence, and underlying mechanisms of HDs remain incompletely understood and warrant further exploration.

Because some HDs can resemble a rim as seen in end-stage small subcortical hemorrhages, it is important to investigate the frequency and factors associated with HDs to reduce potential confusion of lacunar ischemic stroke with small previous hemorrhage in clinical practice. Hence, we aimed to characterize the appearance and evolution of HDs in RSSI, to determine the morphology, frequency, and stage of hemosiderin appearance and identify potential predictors, risk factors, and associations.

Methods

Study Participants

We identified participants from the prospective observational MSS3 that started recruitment in August 2018 and completed 1-year follow-up in October 2021 (ISRCTN 12113543). The MSS3 study protocol is published.9 In brief, MSS3 prospectively recruited participants with ischemic stroke who presented to the Lothian Stroke Service in Edinburgh and surrounding areas, United Kingdom, with symptoms of mild stroke (i.e., NIH Stroke Scale [NIHSS] score ≤7 and modified Rankin Scale [mRS] score ≤2) due to either a lacunar or cortical stroke subtype. All participants were evaluated for cardiac and carotid sources of embolism, with fewer than 10% of those with lacunar strokes found to have either. All participants had a thorough clinical examination by dedicated stroke physicians and detailed diagnostic workup including diagnostic brain MRI or CT at presentation.9 Study 3T brain MRI scans were then obtained at baseline (1–3 months after stroke) and within 6-month and 12-month visits to assess changes in vascular brain lesions.

For this analysis, we considered all MSS3 study participants with clinical lacunar syndrome and a RSSI on MRI. We excluded study participants (N = 122) with cortical syndrome/infarct (N = 99), obvious early (i.e., within the first few days of stroke) hemorrhagic transformation (N = 2), missed scanning at 6-month or 6–12 month follow-ups (N = 9), poor image quality caused by motion artifact (N = 1), and other reasons (N = 11) (eFigure 1).

All participants received usual guideline stroke prevention therapies, including antiplatelet therapy or anticoagulation for those with atrial fibrillation, as well as antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatments. Thrombolysis with guideline-based alteplase was administered in the acute phase when appropriate.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

The study was approved by the Southeast Scotland Regional Ethics Committee (18/SS/0044). Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Data Collection and Management

Patient demographics, vascular risk factors (i.e., hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, smoking status, and history of stroke or transient ischemic attack [TIA]), and medications were collected systematically at each follow-up visit. The NIHSS score at baseline and the mRS score and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test score at 12-month follow-up were also collected. Therapy was categorized as antiplatelet therapy or anticoagulation prescribed at the date of the baseline visit, within 3 months of stroke onset. Smoking status was classified as never smoked or ever smoker (current or ex-smokers). The poor functional outcome at 12-month follow-up was defined as an mRS score ≥2, and the cognitive outcome at 12-month follow-up was assessed using the MoCA.

MRI Acquisition and Analysis

All participants underwent research MRI on a 3T Siemens PRISMA scanner with a 32-channel head coil (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) throughout to acquire sagittal 3D fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images, axial 3D T2-weighted images, sagittal 3D T1-weighted images, and axial 3D SWI sequences. 3D SWI acquisition parameters were as follows: TR = 28 milliseconds; TE = 20 milliseconds; acquired voxel size = 0.63 × 0.63 × 3 mm. Full details of the brain imaging scanning protocol are published.9

The assessment of RSSIs involved more than 5 raters who were blinded to clinical details. Old infarcts and all small vessel disease (SVD) features were recorded, as defined by the STRIVE criteria.2,9 These features included lacunes, white matter hyperintensities, Fazekas scores, cerebral microbleeds, perivascular spaces, iron deposits in the basal ganglia, and the total SVD score.10 All HDs on SWI were assessed by Y.-Y.X., blinded to the participants' clinical details. All the image assessment was checked by a senior neuroradiologist (J.M.W.).

When assessing the features of HDs in RSSIs, only the index infarcts were analyzed at each follow-up MR scanning. The index infarct refers to the acute infarct causing the primary stroke symptoms and physical signs consistent with a clinical stroke syndrome leading to initial presentation to stroke services. All follow-up scans were thoroughly reviewed. HDs observed at any visit within the first 6 months were recorded as positive at the 6-month follow-up. Similarly, all HDs observed from the 6-month visit to 12-month visit were recorded as positive at the 12-month follow-up. The time duration from the index RSSI onset to the follow-up imaging capturing the initial appearance of HDs was recorded.

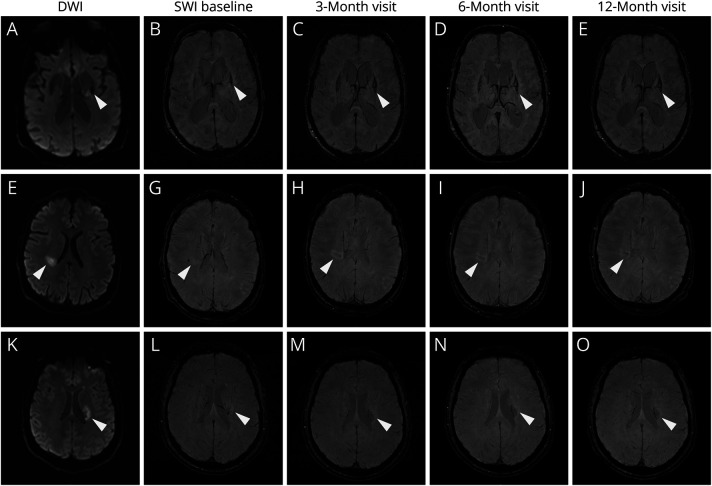

Using SWI, we categorized HDs in SSI into 4 types, spots, smudge, rim, and cluster (Figure 1), with none as a fifth type. The location of RSSI was categorized as anterior circulation (blood supply from internal carotid arteries) and posterior circulation (blood supply from vertebral arteries) regions and further divided into 4 regions to examine the HD distribution: basal ganglia region (internal capsule, caudate, and putamen), thalamus, white matter region (centrum semiovale, including subcortical and periventricular, optic radiation, and corpus callosum), and subtentorial region (brain stem and cerebellum).9 The volume of index RSSIs was calculated according to the following formula: 0.5 × the maximum R-L axial width × the maximum A-P axial width × the vertical height (mm3).11

Figure 1. Morphologies and Description of Hemosiderin Deposits.

CMB = cerebral microbleed; SWI = susceptibility-weighted imaging.

Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were conducted using SPSS 22 (IBM SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Categorical variables were reported as absolute numbers with percentages, and continuous variables were reported as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median with the interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were compared by the χ2 test while the t test (normally distributed variables) or Mann-Whitney U test (non-normally distributed data) was used to compare continuous variables between the HD and non-HD groups.

The binary logistic regression model was used to investigate the associations between RSSI location/volume and HD presence at the 12-month follow-up. Adjustment factors included age, sex, NIHSS, vascular risk factors, and therapy (antiplatelet or anticoagulant), chosen for their clinically plausible relationship with HDs. Because the total SVD score was significantly correlated with individual SVD features, they were incorporated separately into the prediction models (model 1 and model 2). The collinearity of individual SVD features was also tested. The receiver operating characteristic curve was used to evaluate the fit of the logistic regression models.12

Moreover, 2 separate analyses were conducted: one examining the relationship between HDs and poor functional outcomes (defined as mRS score ≥2) using binary logistic regression and another assessing the association between cognitive outcomes (measured by MoCA) using multiple linear regression. Cases with missing data for mRS or MoCA were excluded. To ensure robust estimates, we dichotomized the mRS score into 2 groups: <2 and ≥2. The covariates included age, sex, NIHSS, vascular risk factors, and total SVD scores.

A quantile-quantile plot and a histogram of residuals were used to verify the normality assumptions of the linear regression model (eFigure 2). In addition, to evaluate the agreement between predicted and observed values, we used calibration plots and statistical metrics for 3 logistic regression models (eFigure 3) with R 3.4.2, rms package.13,14

Data Availability

Supporting data of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

Participant Characteristics at Recruitment

108 of 230 participants with stroke recruited to the MSS3 (mean age 63.76 ± 11.45 years, 68.5% male, median NIHSS 1.57 ± 1.38) with symptomatic RSSIs meeting the inclusion criteria were included in this analysis (eFigure 1). The main reason for exclusion was having a cortical stroke.

Among the 108 with RSSIs, 83 (76.9%) developed HDs at some point during the 12-month study period. Table 1 presents the demographic, clinical, and imaging characteristics based on the presence or absence of HDs. Participants with HDs were less likely to have diabetes (19.3% vs 44.0%, p = 0.01). There was no difference in history of stroke or TIA, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and smoking between presence and absence of HDs. Only 2 of 108 participants received alteplase treatment in the acute phase, both of whom developed HDs (Table 1). Participants received either single antiplatelet therapy (aspirin or clopidogrel, n = 98, 90.7%) or anticoagulant therapy (n = 10, 9.3%) after the stroke onset, with no difference between HD and non-HD groups (antiplatelet 84.0% vs 92.8%, anticoagulant 16.0% vs 7.2%, p = 0.19) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Total (N = 108) | Non-HDs (N = 25, 23.1%) | HDs (N = 83, 76.9%) | p Value | |

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 63.76 ± 11.45 | 65.81 ± 9.39 | 63.15 ± 11.99 | 0.31 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 74 (68.5) | 16 (64.0) | 58 (69.9) | 0.58 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 28.29 ± 4.92 | 29.40 ± 4.79 | 27.95 ± 4.93 | 0.14 |

| NIHSS score, median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (0–2) | 0.99 |

| History | ||||

| Stroke or TIA, n (%) | 20 (18.5) | 7 (28.0) | 13 (15.7) | 0.16 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 27 (25.0) | 11 (44.0) | 16 (19.3) | 0.01 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 84 (77.8) | 20 (80.0) | 64 (77.1) | 0.76 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 81 (75.0) | 21 (84.0) | 60 (72.3) | 0.24 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 57 (54.3) | 11 (44.0) | 46 (57.5) | 0.24 |

| Thrombolysis, n (%) | 2 (1.9) | 0 | 2 (1.7) | 0.43 |

| Second prevention therapy | ||||

| Anticoagulant, n (%) | 10 (9.3) | 4 (16.0) | 6 (7.2) | 0.19 |

| Antiplatelet, n (%) | 98 (90.7) | 21 (84.0) | 77 (92.8) | |

| Image features | ||||

| Total SVD score, median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | 0.04 |

| No. of microbleeds, median (IQR) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–1) | 0.11 |

| No. of lacunes, median (IQR) | 2 (0–5) | 0 (0–2) | 2 (0–5) | 0.01 |

| Basal ganglia iron deposit score, median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | 0.72 |

| Fazekas score, median (IQR) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–5) | 0.69 |

| RSSI volume, mm3, mean ± SD | 736.3 ± 1325.6 | 171.2 ± 277.2 | 906.6 ± 1464.1 | <0.001 |

| WMH volume, mL, mean ± SD | 16.64 ± 18.45 | 19.54 ± 24.14 | 15.76 ± 16.43 | 0.74 |

| Location category | ||||

| Anterior circulation, n (%) | 66 (61.1) | 9 (36.0) | 57 (68.7) | 0.03 |

| Posterior circulation, n (%) | 42 (38.9) | 16 (64.0) | 26 (31.3) | |

| Clinical outcome | ||||

| mRS score ≥2, n (%) | 21 (19.4) | 7 (29.2) | 14 (16.9) | 0.18 |

| MoCA score, median (IQR) | 27 (25–29) | 27 (24–28) | 27 (25.5–29) | 0.92 |

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; mRS = modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS = NIH Stroke Scale; SVD = small vessel disease; TIA = transient ischemic attack; WMH = white matter hyperintensity.

Compared with those without HDs, participants with HDs had a higher total SVD score at baseline (2.33 ± 1.28 vs 1.72 ± 1.28, p = 0.04) and more lacunes (3.40 ± 3.94 vs 1.48 ± 2.62, p = 0.006). The index RSSIs that developed HDs were more likely to be large in volume (906.6 ± 1464.1 mm3 vs 171.2 ± 277.2 mm3, p < 0.001) and located in the anterior circulation region (68.7% vs 36.0%, p = 0.03). There were no significant differences in the number of microbleeds (0 [IQR 0–0] vs 0 [IQR 0–1], p = 0.11) or in WMH volume (19.54 ± 24.14 vs 15.76 ± 16.43, p = 0.74) between the groups with and without HDs (Table 1).

Categories and Evolution of HDs

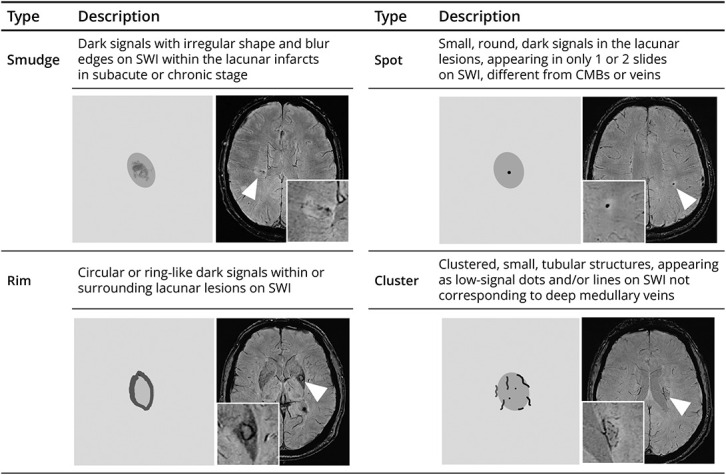

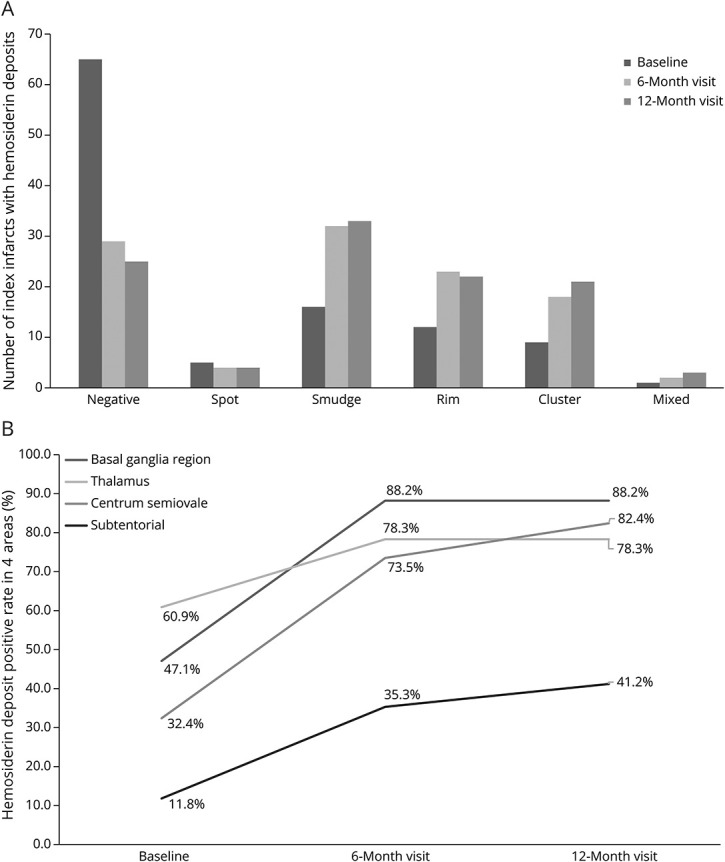

The categories and morphologies of HDs are illustrated in Figure 2 and given in eTable 1. HDs were observed in 43 (55.0%) of 108 within 6 months and 83 (76.9%) of 108 within 12 months of follow-up, with the mean time to first HD detection being 87 (IQR 53–164) days. Of the 83 participants who developed HDs, 43 (55.0%) had appeared by the baseline scan (1–3 months) and 82 (98.8%) by the 6-month follow-up scan (eTable 1), mainly due to the increase in “smudge,” “rim,” and “cluster” patterns (Figure 3). Among all the HD types, the predominant one was “smudge” from the baseline to the 12-month follow-up. The “smudge” could become smaller and darker, diminish over time (eFigure 2), or transform into another pattern during the 12-month follow-up (Figure 3). The “rim” pattern (i.e., similar to long-term sequelae of a primary hemorrhage) occurred in 26.5% of RSSIs by the 6-month visit and 31.7% by the 12-month visit, mainly in RSSIs in the lentiform/internal capsule region (50.0%) or thalamus (36.4%) (eTable 1). The “rim” could be partial or total and appeared approximately at mean 123 (SD 94) days after stroke onset, with 23.1% manifesting at 6 months or later. The “cluster” pattern appeared in 20.9% of RSSIs at baseline and gradually increased, accounting for 25.3% at 12-month follow-up (eTable 1), presenting as lines/dots within the infarct, primarily seen in RSSIs located in white matter regions (Figure 3, K–O). The “rim” and “cluster” tended to become more obvious over time. Three participants developed a mixed type of “rim” and “cluster.” The “spot” pattern was the rarest and most stable (Figures 2A and 3, F–J).

Figure 2. Categories and Evolution of HDs.

Figure 2A illustrates the quantity change of different HD patterns at the baseline, 6-month, and 12-month follow-ups. Figure 2B shows the increased positive rates of HDs in 4 areas at 3 time-point visits. HD = hemosiderin deposit.

Figure 3. Morphology and Evolution of Hemosiderin Deposits.

(A–E) In a patient with an infarct in the basal ganglia, the “rim” pattern developed and became more obvious and thicker along the follow-ups. (F–J) In a patient with a RSSI adjacent to the lateral ventricle, the “smudge” became larger at 3-month and 6-month visits but shrank and turned darker, “condensed,” at the 12-month visit. (K–O) A “cluster” pattern in another RSSI adjacent to the lateral ventricle and the number of dots and lines became more visible inside and around the infarct during follow-up. DWI = diffusion-weighted imaging; RSSI = recent small subcortical infarct.

Factors Influencing Occurrence of HDs

A binary logistic regression model (Table 2) was constructed to include RSSI volume; location; total SVD score; NIHSS score; and demographic variables including age, sex, stroke or TIA, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and smoking. RSSI volume (odds ratio [OR] 1.003, 95% CI 1.001–1.006 per cubic millimeter increase; p = 0.004) and total SVD score (OR 2.35, 95% CI 1.20–4.61, p = 0.01) independently predicted HD occurrence at 12 months, but not RSSI location or prescribed stroke prevention medication (antiplatelet vs anticoagulant therapy) (Table 2, model 1). In a second logistic regression model including individual SVD imaging markers, the number of lacunes showed an association with the occurrence of HDs (OR 1.60, 95% CI 1.13–2.26, p < 0.01). No statistically significant relationships were observed for Fazekas score, number of microbleeds, and basal ganglia mineral deposit score (Table 2, model 2). In addition, no significant association was found between WMH volume and HDs (eTable 2). No collinearity was observed among the individual SVD features (eTable 3). Regarding clinical outcomes, we did not find strong evidence of a link between HDs and mRS score ≥2 at the 12-month follow-up (Table 3), nor between HDs and MoCA scores at the 12-month follow-up (Table 4). Linear regression model assumptions were met as shown by the normality of residuals (eFigure 3). The logistic regression models showed good discrimination (area under the curve >0.88) and calibration (eFigure 4).

Table 2.

Factors Predicting Hemosiderin Deposits: Adjusted Binary Logistic Regression Models

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

| Model 1 | ||

| Age | 0.98 (0.92–1.04) | 0.43 |

| Sex | 2.12 (0.60–7.47) | 0.24 |

| NIHSS score | 0.87 (0.58–1.29) | 0.48 |

| Stroke or TIA history | 0.33 (0.07–1.59) | 0.17 |

| Diabetes | 0.36 (0.10–1.31) | 0.12 |

| Smoking | 2.18 (0.68–6.99) | 0.19 |

| Therapy | 0.36 (0.06–2.24) | 0.28 |

| Volume of index RSSIs, mm3 | 1.003 (1.001–1.006) | 0.005 |

| Location of hemosiderin deposits | 0.71 (0.19–2.61) | 0.60 |

| Total SVD score at baseline | 2.17 (1.13–4.18) | 0.02 |

| Model 2 | ||

| Age | 1.03 (0.96–1.11) | 0.36 |

| Sex | 2.42 (0.64–9.14) | 0.19 |

| NIHSS | 0.78 (0.45–1.14) | 0.27 |

| Stroke or TIA history | 0.22 (0.04–1.22) | 0.08 |

| Diabetes | 0.29 (0.07–1.20) | 0.09 |

| Smoking | 2.07 (0.60–7.20) | 0.25 |

| Therapy | 0.30 (0.05–1.95) | 0.21 |

| Volume of index RSSIs, mm3 | 1.003 (1.001–1.006) | 0.004 |

| Location of hemosiderin deposits | 0.73 (0.19–2.82) | 0.65 |

| Iron deposits in the basal ganglia | 0.61 (0.28–1.34) | 0.22 |

| Fazekas score | 0.90 (0.57–1.44) | 0.67 |

| No. of microbleeds | 1.03 (0.90–1.18) | 0.70 |

| No. of lacunes | 1.52 (1.07–2.16) | 0.02 |

Abbreviations: NIHSS = NIH Stroke Scale; OR = odds ratio; RSSI = recent small subcortical infarct; SVD = small vessel disease; TIA = transient ischemic attack.

Receiver operating characteristic curves: model 1: the area under the curve was 0.87 with 95% CI 0.79–0.95 (p < 0.001); model 2: the area under the curve was 0.89 with 95% CI 0.82–0.96 (p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Association Between Hemosiderin Deposits and mRS: Adjusted Binary Logistic Regression Model (N = 104, Smoking Status Missing = 3, mRS Score Missing = 1)

| mRS score ≥2 | ||

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Age | 0.96 (0.90–1.03) | 0.22 |

| Sex | 0.76 (0.18–3.17) | 0.71 |

| NIHSS | 2.15 (1.35–3.43) | 0.001 |

| BMI | 1.15 (1.00–1.33) | 0.049 |

| History of stroke or TIA | 0.29 (0.04–1.93) | 0.20 |

| Diabetes | 4.57 (0.98–21.34) | 0.05 |

| Hypertension | 0.29 (0.05–1.77) | 0.18 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 1.27 (0.20–7.90) | 0.80 |

| Smoking | 2.79 (0.66–11.76) | 0.16 |

| Hemosiderin deposits | 0.21 (0.04–1.07) | 0.06 |

| Total SVD score at baseline | 2.10 (1.09–4.07) | 0.03 |

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; mRS = modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS = NIH Stroke Scale; OR = odds ratio; SVD = small vessel disease; TIA = transient ischemic attack.

Receiver operating characteristic curves: the area under the curve was 0.88 with 95% CI 0.79–0.96 (p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Association Between Hemosiderin Deposits and MoCA: Multiple Linear Regression Model (N = 97, MoCA Missing = 11)

| Unstandardized B | Standardized coefficient beta | 95% CI for unstandardized B | p Value | |

| Age | −0.04 | −0.15 | −0.10 to 0.10 | 0.11 |

| Sex | −0.52 | −0.07 | −1.81 to 0.77 | 0.42 |

| BMI | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.15 to 0.10 | 0.68 |

| NIHSS | −0.98 | −0.44 | −1.37 to −0.58 | <0.001 |

| Stroke or TIA history | −1.72 | −0.20 | −3.33 to −0.12 | 0.04 |

| Diabetes | −0.95 | −0.12 | −2.36 to 0.47 | 0.19 |

| Hypertension | 0.14 | 0.02 | −1.27 to 1.55 | 0.84 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 1.29 | 0.17 | −0.08 to 2.67 | 0.07 |

| Smoking | 0.77 | 0.12 | −0.36 to 1.89 | 0.18 |

| Hemosiderin deposits | −0.33 | −0.04 | −1.77 to 1.10 | 0.64 |

| Total SVD score at baseline | −0.10 | −0.04 | −0.61 to 0.40 | 0.68 |

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; NIHSS = NIH Stroke Scale; OR = odds ratio; SVD = small vessel disease; TIA = transient ischemic attack.

The result of the linear regression indicated that the regression model is statistically significant in explaining the variance in the dependent variable (F = 4.756, p < 0.001). Assumptions of linear regression were checked graphically and were broadly met.

Discussion

We describe the morphology and evolution of HDs as a long-term imaging marker of RSSIs on SWI sequences in 108 participants over the first year after clinically evident lacunar ischemic stroke. HDs were observed in 43 (55.0%) of 108 within 6 months and 83 (76.9%) of 108 within 12 months of stroke. Of the 4 different patterns of HDs identified, the initial and prevailing type was the “smudge” pattern (Figure 1) while the “rim” pattern that could be mistaken for primary hemorrhage was present in over 25% of RSSIs from 6-month follow-up onward. HDs were independently associated with larger RSSI volumes at the acute stage and with a higher total SVD score.

Our study may have important clinical implications. First, we describe and subcategorize in detail a distinctive image marker on SWI, HDs in RSSIs, providing additional insights beyond degrees of cavitation or disappearance of RSSI after lacunar ischemic stroke. The predominant “smudge” type persisted throughout the year of follow-up while “rim” and “cluster” patterns demonstrated characteristic distributions, primarily in basal ganglia gray matter and in white matter regions, respectively. Our study also indicated that the HD appearance changed over time. The smudge could become darker, diminish (eFigure 2), or evolve into a rim or cluster while “rim” and “cluster” patterns often combined with “smudge.” There were also a few cases developing into the “rim and cluster mixed” type. The rare “spot” pattern remained stable over time, emphasizing the stability of this particular HD type.

Second, the identification of the “rim” pattern in over 25% of SSIs at all follow-up time points holds clinical importance and research interest. Some hemosiderin rims were striking, potentially leading to misinterpretation as sequelae of a primary hemorrhage rather than an infarct had the initial diagnostic imaging not shown that the lesion was ischemic. Contrary to previous studies suggesting hemorrhagic foci as indicative of hemorrhagic transformation in high-risk populations,7 our findings suggest that the “rim” pattern could evolve from the “smudge” pattern over time. It is important to note that HDs, including the “rim” pattern, were not associated with the number of microbleeds, other types of bleeding, or prescribed antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy in adjusted analyses, reducing the likelihood of attributing HD patterns solely to hemorrhagic transformation due to antiplatelet or anticoagulant treatment. The “rim” pattern typically was detected approximately at mean 123 (SD 94) days after stroke onset, with 23.1% manifesting at 6 months or later, indicating its association with chronic, slowly evolving, pathologic changes in RSSIs. Therefore, the presence of HDs should not be a contraindication for antithrombotic therapy.

Third, different HD patterns may stem from distinct mechanisms. Given the heterogeneity of SVD involving arterioles, capillaries, and venules,1 SWI findings could reflect red blood cell leakage from vessels due to blood-brain barrier damage, leading to hemosiderin visibility and accumulation.15-18 This might explain why the “smudge” predominated among the RSSIs. Possibly, it might indicate neovascularization into the damaged tissue, with newly forming vessels typically being leaky leading to HDs. Moreover, the location of infarcts might determine HD categorization, with “rim” patterns more common in lenticulostriate artery (LSA) territories such as the basal ganglia and thalamus while “cluster” patterns prevail in white matter regions such as the corona radiata and centrum semiovale. This might reflect a similar process to the vessel clusters seen in WMH tending to cavitate,19 possibly to arteriole to venule shunting,20 venous collagenosis,21,22 or arteriolar tortuosity.23

Finally, infarct volume, total SVD score, and number of lacunes were identified as potential predictive image markers of HDs, highlighting the significance of the initial infarct severity and chronic SVD pathology. Our findings align with previous studies, suggesting that HDs may be widespread but underrecognized in participants with SVD. Among participants with noncardioembolic stroke or TIA, 10.4% showed hemorrhagic dark signal at the RSSI lesion on follow-up. The large lesion size and anterior circulation location were associated with hemorrhagic foci, rather than the number of CMBs, history of intracranial hemorrhage, cavitary change, and antiplatelet type.7 Furthermore, another study revealed that 44.6% of RSSIs in the territory of LSA (the basal ganglia) exhibited hemorrhagic foci. These foci were linked to larger lesion volumes, increased cavitation formation, shorter total LSA length, higher baseline NIHSS scores, and poorer functional outcomes.8 Of interest, a vessel cluster sign was observed in the white matter region of 33.33% of participants with sporadic SVD. This sign correlated with more lacunes, higher WMH volume, and lower cerebrovascular reactivity in normal-appearing white matter.21 Our findings supported that the size of infarcts and the number of lacunes had an impact on HDs. In our study, each additional cubic millimeter increase in infarct volume was associated with a 0.3% increase in the odds of having HDs and no specific cutoff value was identified. However, divergent results were observed for WMH volume, treatment, and clinical outcomes. This inconsistency could be attributed to differences in the study population and sample size. One strength of our study was the more frequent follow-up scanning, allowing us to track the formation and evolution of HDs more comprehensively than previous studies. Given the varied pathologies associated with different HD patterns, further longitudinal studies are warranted to explore the intricate relationship between HDs and SVD image markers, as well as clinical outcomes.

Our study has limitations. Owing to varying frequencies and time intervals of follow-up scans among participants in our study, the mean time from stroke onset to the first detection of HDs may not accurately reflect the duration of HD formation. In addition, further investigation into the relationship between HDs and therapy is warranted, particularly considering the absence of patients receiving thrombolysis in our study. While the individual subgroups are relatively small, the overall study encompasses a large sample size. Future studies could benefit from expansion to examine the frequency, location, influencing factors, and the association with clinical outcomes in larger cohorts. Moreover, caution is advised when identifying and interpreting HDs in clinical practice because distinguishing them from primary hemorrhage can be challenging without imaging from the acute stage and periodic follow-up. Our study is exploratory; hence, studies with larger sample sizes and longer term follow-ups are warranted to better characterize the evolution of HDs and the relationship with patient characteristics. The pathophysiologic significance of this new feature should also be confirmed through pathology studies and higher resolution imaging, such as 7T MRI.

In conclusion, HDs may occur in up to three-quarters of participants with RSSIs, and their presence on SWI may be associated with RSSI volume and the total SVD score. Caution is advised when identifying HDs to distinguish them from primary hemorrhage, particularly the “rim” pattern. This new imaging marker warrants further confirmation in future research to assess its evolution and contribution to SVD burden.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Xue Man (Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada) and Dr. Yulu Shi (Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, China) for their helpful comments to the article. The authors appreciate all the patients who took part in the MSS3.

Glossary

- HD

hemosiderin deposit

- IQR

interquartile range

- LSA

lenticulostriate artery

- MoCA

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- mRS

modified Rankin Scale

- MSS3

Mild Stroke Study 3

- NIHSS

NIH Stroke Scale

- OR

odds ratio

- RSSI

recent small subcortical infarct

- SVD

small vessel disease

- SWI

susceptibility-weighted imaging

- TIA

transient ischemic attack

- WMH

white matter hyperintensity

Appendix 1. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| Yu-Yuan Xu, MD | China National Clinical Research Center for Neurological Diseases, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Francesca M. Chappell, PhD | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Maria Del C. Valdés Hernández, PhD | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, UK Dementia Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Carmen Arteaga-Reyes, PhD | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, UK Dementia Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Una Clancy, PhD | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, UK Dementia Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Daniela Jaime Garcia, PhD | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, UK Dementia Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Stewart Wiseman, PhD | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, UK Dementia Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Michael S. Stringer, PhD | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, UK Dementia Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Michael Thrippleton, PhD | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, UK Dementia Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Yajun Cheng, PhD | Department of Neurology, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Junfang Zhang, PhD | Department of Neurology & Institute of Neurology, Ruijin Hospital affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, China | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Xiaodi Liu, PhD | Division of Neurology, Department of Medicine, LKS Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, China | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Angela C.C. Jochems, PhD | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, UK Dementia Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Fergus Doubal, MBChB, PhD | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, UK Dementia Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Joanna M. Wardlaw, MD, FRCR, FMedSci | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, UK Dementia Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

Appendix 2. Coinvestigators

| Name | Location | Role | Contribution |

| Ian Marshall, PhD | University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Emeritus Chair of Magnetic Resonance Physics | Medical physics |

| Susana Muñoz Maniega, PhD | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Research Fellow | Image analysis |

| Eleni Sakka, PhD | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Research Fellow | Image analysis |

| Rosalind Brown, PhD | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, UK Dementia Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Research Manager | Study administration |

| Olivia K.L. Hamilton, PhD | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, UK Dementia Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Research Fellow | Data acquisition |

| Ellen Backhouse, PhD | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, UK Dementia Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Research Fellow | Data acquisition and analysis |

| Will Hewins, BSc, MSc | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, UK Dementia Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Assistant Psychologist | Study co-ordination; data acquisition |

| Rachel Locherty | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, UK Dementia Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Research Nurse | Study co-ordination; data acquisition |

| Emilie Sleight, PhD | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, UK Dementia Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | PhD Student (VRS) | MRI vascular function acquisition/analysis |

| Alasdair G. Morgan, MD | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, UK Dementia Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | PhD Student (VRS) | MRI vascular function acquisition/analysis |

| Iona Hamilton | Edinburgh Imaging Facility (Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh), University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Senior Radiographer | Radiographers |

| Gayle Barclay | Edinburgh Imaging Facility (Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh), University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Senior Research MRI Radiographer | Radiographers |

| Donna McIntyre | Edinburgh Imaging Facility (Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh), University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | MRI Research Radiographer | Radiographers |

| Charlotte Jardine | Edinburgh Imaging Facility (Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh), University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | MRI Research Radiographer | Radiographers |

| Dominic Job, PhD | University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Senior Research Data Manager | Programming/data management |

| David Perry, PhD | University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Research Technology Manager | Programming/data management |

| Tom MacGillivray, PgCAP | Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Senior Research Fellow & Image Analysis Core Laboratory Manager | Retinal studies |

| Charlene Hamid | University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom | Lead Ophthalmic Imager and Analysist | Retinal data acquisition and analysis |

| Salvatore Rudilosso, PhD, MB ChB | Comprehensive Stroke Center, Department of Neuroscience, Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, Spain | Visiting Neurology Fellow | DTI+ve lesion analysis |

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Ian Marshall, Susana Muñoz Maniega, Eleni Sakka, Rosalind Brown, Olivia K.L. Hamilton, Ellen Backhouse, Will Hewins, Rachel Locherty, Emilie Sleight, Alasdair G. Morgan, Iona Hamilton, Gayle Barclay, Donna McIntyre, Charlotte Jardine, Dominic Job, David Perry, Tom MacGillivray, Charlene Hamid, and Salvatore Rudilosso

Study Funding

This research was funded by the UK Dementia Research Institute, which receives its funding from DRI Ltd. funded by the UK Medical Research Council, Alzheimer's Society, and Alzheimer's Research UK; the Fondation Leducq Network for the Study of Perivascular Spaces in Small Vessel Disease (16 CVD 05); Stroke Association Small Vessel Disease-Spotlight on Symptoms (SAPG 19n100068); British Heart Foundation Edinburgh Centre for Research Excellence (RE/18/5/34216); the Row Fogo Charitable Trust Centre for Research into Aging and the Brain. A.C.C. Jochems was funded by the Alzheimer's Society (ref 486 [AS-CP-18b-001]), University of Edinburgh College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine, and the UK Dementia Research Institute, which receives funding from UK DRI Ltd. M.S. Stringer was funded by the Fondation Leducq and UK DRI as above and Stroke Association (SA PDF 23\100007). M. Thrippleton received funding from the National Health Service Lothian Research and Development Office. U. Clancy was funded by a Chief Scientist Office Clinical Academic Fellowship (CA/18) and is funded by the Scottish Clinical Excellence Research Development Scheme at the University of Edinburgh. D.J. Garcia is funded by the Wellcome Trust. C. Arteaga-Reyes receives funding from Mexican Council of Humanities Science and Technology, Anne Rowling Regenerative Neurology Clinic, and the Row Fogo Charitable Trust Centre into Aging and the Brain. F. Doubal received funding from the Stroke Association and Garfield Weston Foundation, NHS Research Scotland and the University of Edinburgh. The University 3T MRI Research scanner in the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh is supported by the Scottish Funding Council through the Scottish Imaging Network, a Platform for Scientific Excellence (SINAPSE) collaboration; the Wellcome Trust (104916/Z/14/Z), Dunhill Trust (R380R/1114), Edinburgh and Lothians Health Foundation (2012/17), Muir Maxwell Research Fund, Edinburgh Imaging, and the University of Edinburgh.

Disclosure

The authors report no relevant disclosures. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Wardlaw JM, Smith C, Dichgans M. Mechanisms of sporadic cerebral small vessel disease: insights from neuroimaging. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(5):483-497. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70060-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(8):822-838. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70124-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duering M, Biessels GJ, Brodtmann A, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease-advances since 2013. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22(7):602-618. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00131-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinter D, Gattringer T, Enzinger C, et al. Longitudinal MRI dynamics of recent small subcortical infarcts and possible predictors. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2019;39(9):1669-1677. doi: 10.1177/0271678X18775215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duering M, Adam R, Wollenweber FA, et al. Within-lesion heterogeneity of subcortical DWI lesion evolution, and stroke outcome: a voxel-based analysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2020;40(7):1482-1491. doi: 10.1177/0271678X19865916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loos CMJ, Makin SDJ, Staals J, Dennis MS, van Oostenbrugge RJ, Wardlaw JM. Long-term morphological changes of symptomatic lacunar infarcts and surrounding white matter on structural magnetic resonance imaging. Stroke. 2018;49(5):1183-1188. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.020495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho AH, Kwon HS, Lee MH, et al. Hemorrhagic focus within the recent small subcortical infarcts on long-term follow-up magnetic resonance imaging. Stroke. 2022;53(4):e139-e140. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.037939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang S, Shang WZ, Cui JY, et al. Prevalence and predictors of hemorrhagic foci on long-term follow-up MRI of recent single subcortical infarcts. Transl Stroke Res. Published online December 14, 2023. doi: 10.1007/s12975-023-01224-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clancy U, Garcia DJ, Stringer MS, et al. Rationale and design of a longitudinal study of cerebral small vessel diseases, clinical and imaging outcomes in patients presenting with mild ischaemic stroke: Mild Stroke Study 3. Eur stroke J. 2021;6(1):81-88. doi: 10.1177/2396987320929617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staals J, Makin SDJ, Doubal FN, Dennis MS, Wardlaw JM. Stroke subtype, vascular risk factors, and total MRI brain small-vessel disease burden. Neurology. 2014;83(14):1228-1234. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khoury N, Dargazanli C, Zuber K, et al. Diffusion-weighted-imaging infarct volume measurement tools show discrepancies leading to diverging thrombectomy decisions. J Neuroradiol. 2021;48(4):305-310. doi: 10.1016/j.neurad.2020.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Austin PC, Steyerberg EW. Interpreting the concordance statistic of a logistic regression model: relation to the variance and odds ratio of a continuous explanatory variable. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrell FE. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. 1st ed. Springer-Verlag; 2001. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-3462-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Comprehensive R Archive Network. Updated October 31, 2023. Accessed November 6, 2023. https://cran.r-project.org/

- 15.Challa VR, Bell MA, Moody DM. A combined hematoxylin-eosin, alkaline phosphatase and high-resolution microradiographic study of lacunes. Clin Neuropathol. 1990;9(4):196-204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher M, French S, Ji P, Kim RC. Cerebral microbleeds in the elderly: a pathological analysis. Stroke. 2010;41(12):2782-2785. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.593657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang DD, Cao Y, Mu JY, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers and cerebral small vessel disease: a community-based cohort study. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2022;7(4):302-309. doi: 10.1136/svn-2021-001102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofer E, Pirpamer L, Langkammer C, et al. Heritability of R2* iron in the basal ganglia and cortex. Aging (Albany NY). 2022;14(16):6415-6426. doi: 10.18632/aging.204212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rudilosso S, Olivera M, Esteller D, et al. Susceptibility vessel sign in deep perforating arteries in patients with recent small subcortical infarcts. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021;30(1):105415. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.105415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Østergaard L, Engedal TS, Moreton F, et al. Cerebral small vessel disease: capillary pathways to stroke and cognitive decline. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36(2):302-325. doi: 10.1177/0271678X15606723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rudilosso S, Chui E, Stringer MS, et al. Prevalence and significance of the vessel-cluster sign on susceptibility-weighted imaging in patients with severe small vessel disease. Neurology. 2022;99(5):e440-e452. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown WR, Moody DM, Challa VR, Thore CR, Anstrom JA. Venous collagenosis and arteriolar tortuosity in leukoaraiosis. J Neurol Sci. 2002;203-204:159-163. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00283-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keith J, Gao FQ, Noor R, et al. Collagenosis of the deep medullary veins: an underrecognized pathologic correlate of white matter hyperintensities and periventricular infarction? J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2017;76(4):299-312. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlx009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Supporting data of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.