Abstract

Ectomycorrhizal fungi (EMF) are key symbiotic microbial components for the growth and health of trees in urban greenspace habitats (UGSHs). However, the current understanding of EMF diversity in UGSHs remains poor. Therefore, in this study, using morphological classification and molecular identification, we aimed to investigate EMF diversity in three EMF host plants: Cedrus deodara in the roadside green belt, and C. deodara, Pinus massoniana, and Salix babylonica in the park roadside green belt, in Guiyang, China. A total of 62 EMF Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) were identified, including 13 EMF OTUs in the C. deodara roadside green belt, and 23, 31, and 9 EMF OTUs in the park green belts. C. deodara, P. massoniana, and S. babylonica were respectively identified in park green belts. Ascomycota and Basidiomycota were the dominant phylum in the EMF communities in roadside and park green habitat, respectively. The Shannon and Simpson indexes of the C. deodara EMF community in the park green belt were higher than those in the roadside green belt. EMF diversity of the tree species in the park green belt was P. massoniana > C. deodara > S. babylonica. Differences in EMF community diversity was observed among the different greening tree species in the UGSHs. UGSHs with different disturbance gradients had a significant impact on the EMF diversity of the same greening tree species. These results can be used as a scientific reference for optimizing the design and scientific management of UGSHs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-74448-8.

Keywords: Diversity, Ectomycorrhizal fungi, Greening trees, Urban greenspace habitats, Urbanization

Subject terms: Ecology, Ecology, Environmental sciences

Introduction

Urbanization has changed the human living environment and played a “filter” role to microbial diversity1,2. Often, alien plant species are introduced in urban areas to increase the beauty of urban landscapes, leading to ecosystem convergence. This convergence phenomenon leads to biodiversity decline, and homogenization of habitats lead to homogenization of urban soil microorganisms3. A reduction in contact with natural biodiversity weakens the microbiome and immune system of the human body, thereby affecting human health. Thus, rapid urbanization negatively impacts microbial biodiversity and consequently, human health4–7. Exposure to diverse urban greenspace habitats (UGSHs) can reduce blood pressure, relieve pain, and reduce mortality8–10. Although the mechanisms associated with these positive effects remain unclear, the effects may be due to the interaction of plants and soil microbial communities with humans and the soil microbiome can transfer to the residents, altering human microbiome composition, influencing immune function and health outcomes11–13. Therefore, it is necessary to improve our understanding of soil microbial diversity among different UGSHs.

UGSHs allow pollution degradation and remediation for human survival14,15, water resource management, carbon maintenance, nutrient cycling, and a series of basic ecosystem services16–18, such as promoting biochemical cycles and soil processes19,20; therefore, they are key in modern urban ecosystems21. “The microbiome rewilding hypothesis” proposes that microbial diversity in urban green spaces can effectively improve urban population health by providing a “natural” microbiome to urban residents22,23. However, owing to environmental characteristics, artificial management, and maintenance types, different UGSHs differ considerably in structure and function. Urban roadside and park green belts are common UGSHs types. Roadside green belts promote isolation, safety, and ecological protection; these soils become relatively isolated habitats surrounded by concrete fences and are subject to multiple disturbances (for example, automobile exhaust emissions, dust fall, road management, and maintenance), which can influence soil enzyme activity and organic carbon content, affecting soil microbial diversity24,25. Urban parks provide important ecological services such as air purification, climate regulation, environment beautification, and physical and mental health promotion of residents26,27. Parks are often affected by human activities, and the soil surface is trampled and compacted28,29, which affects soil pore connectivity, permeability, air permeability, temperature, rooting space, nutrient flow, and biological activity30–32. Human disturbance is the main factor affecting soil microbial diversity33,34. Soil microbiomes in UGSHs play an important role in the sustainable and stable development of urban ecological environments by alleviating psychological pressure and physical health27. Therefore, strengthening the monitoring, evaluation, and research of soil microorganisms in UGSHs is of great scientific and practical significance.

Ectomycorrhizal fungi (EMF) play an important role in maintaining biodiversity and plant community succession35. Pinaceae, Fagaceae, Salicaceae, and other major tree species are EMF host plants that are widely distributed in most forest ecosystems36. EMF help host plants absorb nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and other elements) and alleviate heavy metal pollution stress and antagonize diseases37,38. Some EMF can form fruiting bodies during the completion of their life cycle and are often used as indicators of changes in UGSHs39. EMF allows for rapid establishment or promotion of early tree species colonization in disturbed areas40. Considering that many ectomycorrhizal host trees such as Pinus, Populus, and Salix are distributed in cities, UGSHs are characteristic of habitat isolation and long-term artificial perturbations (for example, exposed pollutants, artificial disturbance, and management activities) and obstruct the interspecies interactions of fungi, resulting in lower EMF diversity in UGSHs41,42. Therefore, a deeper understanding of EMF diversity in UGSHs will allow for improved scientific management.

A large majority of studies on EMF diversity has focused on natural ecosystem habitats such as different forest types and grasslands43,44, reporting changes in soil microbial communities45, whereas few studies have focused on EMF diversity, in UGSHs. Therefore, our research focused on the EMF diversity in UGSHs. In this study, we selected C. deodara, P. massoniana, and S. babylonica in the urban park roadside green belt and C. deodara in the urban roadside green belt as the research objects. We compared the effects of different habitats (park and roadside green belt) on the same EMF host plant and the same habitat (park roadside green belt) on the EMF diversity of different host plants. We hypothesized that, under different UGSHs: (1) EMF diversity would differ among different tree species within the same environment; and (2) EMF diversity would vary for the same tree species under different environments. The present study aimed to provide a scientific reference for optimizing the design and scientific management of UGSHs.

Results

EMF infestation rate

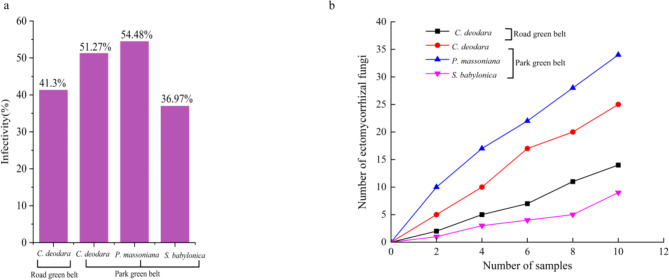

In the two UGSHs, significant differences (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1a) in EMF infestation rates were observed among three greening tree species; EMF infestation rate of S. babylonica in park green belts was the lowest, whereas no significant difference (P > 0.05) in the C. deodara EMF infestation rate was observed. The EMF infection rates were as follows: P. massoniana in parks (54.48%) > C. deodara in parks (51.27%) > C. deodara on roads (41.3%) > S. babylonica in parks (36.97%).

Fig. 1.

Ectomycorrhizal fungi (EMF) infection rate (a) and dilution curves (b) of different greening tree species. The height of the purple bars in (a) represents the extent of EMF infection in the greening tree species.  represents Cedrus deodara in the roadside green belts;

represents Cedrus deodara in the roadside green belts;  represent Cedrus deodara in the park roadside green belts;

represent Cedrus deodara in the park roadside green belts;  represent Pinus massoniana in the park roadside green belts;

represent Pinus massoniana in the park roadside green belts;  represent Salix babylonica in the park roadside green belts.

represent Salix babylonica in the park roadside green belts.

EMF community composition and structure

EMF OTUs (Table 1) was as follows: P. massoniana in parks (31) > C. deodara in parks (23) > C. deodara on roads (13) > S. babylonica in parks (9), which indicated that EMF richness was obviously different among the diverse greening trees in the different UGSHs. EMF species dilution curve (Fig. 1b) showed that with an increase in the sampling amount, the number of EMF OTUs gradually increased but did not tend to stabilize, which indicated that the sampling amount did not fully or accurately reflect EMF diversity in the study sites, suggesting large spatial variation in the EMF community in UGSHs. Therefore, increasing the number of EMF samples in subsequent related investigations is necessary.

Table 1.

Ectomycorrhizal fungi colonizing greening tree species root from different green belts association habitats were identified based on morphotyping and sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) rDNA.

| Number | OTUs | Genbank ID | Sequence length/bp | EMF hosts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Amphinema sp.1 | PQ049667 | 645 | ▽△ |

| 2 | Amphinema sp.2 | PQ049668 | 682 | ▽ |

| 3 | Archaeorhizomyces borealis | PQ049669 | 530 | ▽ |

| 4 | Basidiomycota sp. | PQ049670 | 680 | ▽ |

| 5 | Cenococcum geophilum | PQ049671 | 511 | ▽○ |

| 6 | Cenococcum sp.1 | PQ049672 | 570 | △ |

| 7 | Ceratobasidiaceae sp. | PQ049673 | 697 | ▽ |

| 8 | Clavulicium delectabile | PQ049674 | 670 | ▽ |

| 9 | Clavulina sp. | PQ049675 | 672 | △ |

| 10 | Clavulina sp.1 | PQ049676 | 618 | ▽ |

| 11 | Clavulina sp.2 | PQ049677 | 706 | ▽ |

| 12 | Clavulinaceae sp.1 | PQ049678 | 672 | ▽ |

| 13 | Cortinarius sp. | PQ049679 | 522 | ▽ |

| 14 | Cortinarius sp.1 | PQ049680 | 634 | △ |

| 15 | Dothideomycetes sp. | PQ049681 | 542 | △ |

| 16 | Eurotiomycetes sp.1 | PQ049682 | 644 | ▲ |

| 17 | Helvellosebacina sp. | PQ049683 | 640 | △ |

| 18 | Hypomyces luteovirens | PQ049684 | 684 | ▽ |

| 19 | Ilyonectria macrodidyma | PQ049685 | 584 | △ |

| 20 | Ilyonectria sp.1 | PQ049686 | 574 | △ |

| 21 | Inocybe pseudoreducta | PQ049687 | 716 | ○ |

| 22 | Lactarius akahatsu | PQ049688 | 597 | ○ |

| 23 | Lactarius hatsudake | PQ049689 | 597 | ○ |

| 24 | Lactarius kesiyae | PQ049690 | 762 | ▽ |

| 25 | Lactarius salmonicolor | PQ049691 | 760 | ▽ |

| 26 | Lophiostoma corticola | PQ049692 | 552 | ▲ |

| 27 | Massarina sp.1 | PQ049693 | 554 | ▲ |

| 28 | Oidiodendron citrinum | PQ049694 | 540 | ▲△ |

| 29 | Oidiodendron maius | PQ049695 | 576 | ▲△ |

| 30 | Oidiodendron sp.1 | PQ049696 | 585 | ▲△ |

| 31 | Oidiodendron sp.2 | PQ049697 | 599 | △ |

| 32 | Otidea bicolor | PQ049698 | 648 | ▽ |

| 33 | Otidea bufonia | PQ049699 | 672 | ▽ |

| 34 | Otidea subpurpurea | PQ049700 | 647 | ▽ |

| 35 | Pseudotomentella sp.1 | PQ049701 | 758 | △ |

| 36 | Russula brevispora | PQ049702 | 608 | ▲○ |

| 37 | Russula catillus | PQ049703 | 648 | ▽△ |

| 38 | Russula cremicolor | PQ049704 | 716 | ▽△ |

| 39 | Russula indocatillus | PQ049705 | 701 | ▽ |

| 40 | Russula sp.1 | PQ049706 | 585 | ▽ |

| 41 | Sebacina dimitica | PQ049707 | 636 | ▽ |

| 42 | Sebacina incrustans | PQ049708 | 534 | ▽ |

| 43 | Sebacina sp. | PQ049709 | 652 | ▽ |

| 44 | Sebacina sp.1 | PQ049710 | 537 | ▽○ |

| 45 | Sebacina sparassoidea | PQ049711 | 652 | △ |

| 46 | Thelephora sp.1 | PQ049712 | 653 | ○ |

| 47 | Thelephoraceae sp.1 | PQ049713 | 685 | △ |

| 48 | Thelephoraceae sp.2 | PQ049714 | 584 | ▽ |

| 49 | Tomentella sp. | PQ049715 | 695 | ▽ |

| 50 | Tomentella sp.1 | PQ049716 | 683 | ▽ |

| 51 | Tomentella sp.2 | PQ049717 | 683 | ▽ |

| 52 | Tomentella sp.3 | PQ049718 | 698 | △ |

| 53 | Tomentella sp.4 | PQ049719 | 686 | ○ |

| 54 | Tomentella stuposa | PQ049720 | 686 | ▽○ |

| 55 | Trichophaea sp. | PQ049721 | 613 | ▲ |

| 56 | Trichophaea sp.1 | PQ049722 | 595 | ▲△ |

| 57 | Trichophaea sp.2 | PQ049723 | 614 | ▲△ |

| 58 | Tylospora sp. | PQ049724 | 463 | ▽ |

| 59 | Venturia sp.1 | PQ049725 | 591 | △ |

| 60 | Wilcoxina sp. | PQ049726 | 616 | ▲ |

| 61 | Wilcoxina sp.1 | PQ049727 | 617 | ▲△ |

| 62 | Wilcoxina sp.2 | PQ049728 | 611 | ▲△ |

Note: ▲ represents the C. deodara on roads; △ represents the C. deodara in parks; ▽ represents the P. massoniana in parks; ○ represents the S. babylonica in parks.

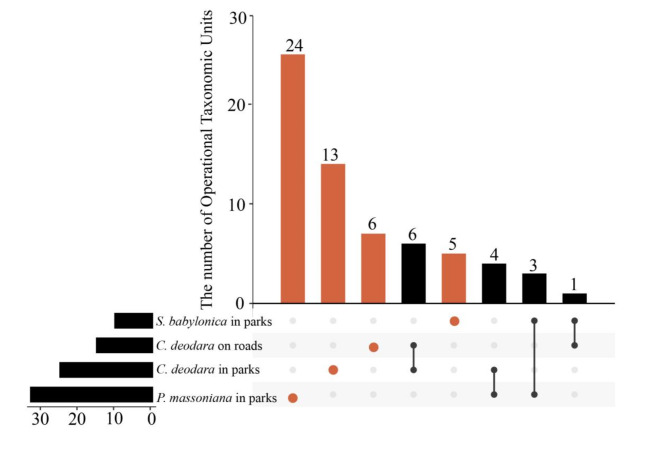

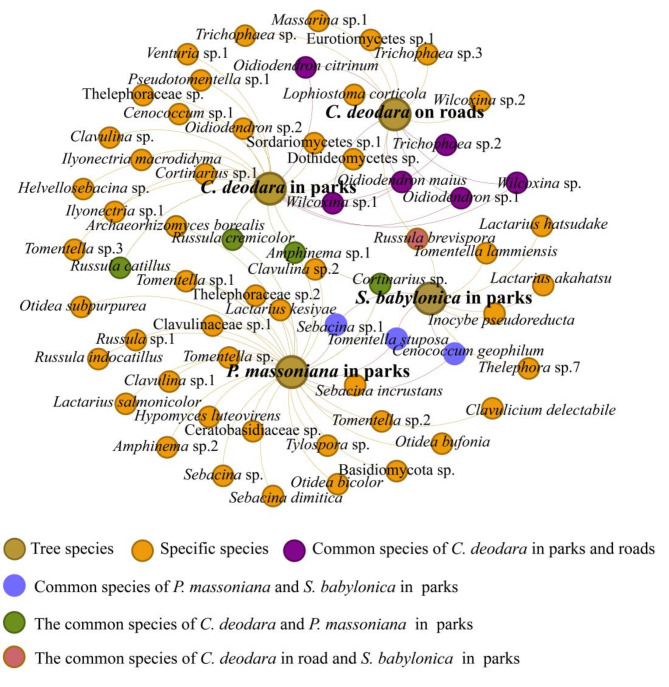

EMF community in each greening tree showed that the number of specific OTUs was higher than that of common OTUs (Fig. 2), and the common OTUs were mainly Oidiodendron, Wilcoxina, and Russula (Fig. 3). No common OTUs were observed among the three greening trees, including C. deodara and S. babylonica in the park green belt.

Fig. 2.

UpSet Venn diagram of Ectomycorrhizal fungi in different greening tree species. Orange-red dots and the height of the column represent the corresponding tree species and the number of unique Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) occupied, respectively. The line connected by the black dots indicates that the tree species corresponding at the two endpoints share common OTUs, while the height of the black column represents the number of common OTUs between the corresponding two greening tree species.

Fig. 3.

Co-occurrence network of greening tree species ectomycorrhizal fungi communities in different green belt.

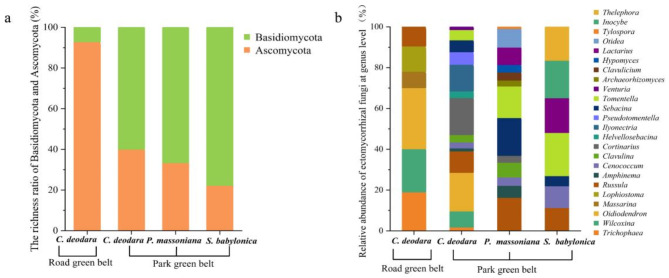

Ascomycota and Basidiomycota were the dominant phylum in the roadside and park green belts, respectively (Fig. 4a). The EMF community structures in different UGSHs differed significantly (Fig. 4b). Trichophaea, Wilcoxina, and Oidiodendron were the dominant genus in roadside green belts. Tomentella, Russula, and Genocococcum were the dominant genus in park green belts. Both Wilcoxina and Oidiodendron were the most common dominant genus of C. deodara in the two UGSHs but were more abundant in the roadside green belt (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Ratios of Ascomycota to Basidiomycota fungal phylum (a) and relative abundance at the ectomycorrhizal fungi (EMF) genus level (b) in different greening tree species. The small squares of different colors represent the classification of EMF at the phylum (a) and genus levels (b) with each color corresponding to the color of the column in the figure. The height of the corresponding color column represents the richness or relative abundance of the EMF in the phylum or genus in the greening tree species.

EMF community diversity and similarity

The EMF diversity (Table 2) among greening trees was as follows: P. massoniana in parks > C. deodara in parks > C. deodara on roads > S. babylonica in parks. This shows that UGSHs disturbance tends to reduce EMF diversity in C. deodara, and EMF host plants might have an important influence on EMF diversity. The Jaccard and Sørenson similarity indices of the EMF communities among different host plants was low, and C. deodara and S. babylonica EMF communities differed (Table 3).

Table 2.

EMF diversity of urban greening tree species.

| Plots | EMF hosts | OTUs | Shannon index | Simpson index | Pielou index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roadside green belt | C. deodara | 13 | 2.57 | 0.92 | 0.97 |

| Park green belt | C. deodara | 23 | 3.18 | 0.96 | 0.99 |

| S. babylonica | 9 | 2.20 | 0.89 | 0.96 | |

| P. massoniana | 31 | 3.43 | 0.97 | 0.98 |

Table 3.

The Jaccard (lower left) and Sørenson (upper right) similarity index of EMF community of greening tree species in different UGSHs.

| Tree species for parks and roads greening habitat | Similarity index | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. deodara on roads | C. deodara in parks | P. massoniana in parks | S. babylonica in parks | |

| C. deodara on roads | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.09 | |

| C. deodara in parks | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.00 | |

| P. massoniana in parks | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.13 | |

| S. babylonica in parks | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.08 | |

Discussion

EMF is highly sensitive to soil nutrient and pollutant levels46. EMF plays a vital role in UGSHs and serves as an indicator of environmental quality. In this study, 62 EMF OTUs related to the two UGSHs were identified in three greening tree species. The decline in EMF OTU number showed the following pattern: P. massoniana in parks (31) > C. deodara in parks (23) > C. deodara on roads (13) > S. babylonica in parks (9). Among these, EMF OTU richness of P. massoniana was the highest, which might be related to the fact that P. massoniana is an native tree in China with relatively higher EMF richness (76 ~ 138 OTUs)38 in natural forest habitats. EMF richness in S. babylonica and C. deodara was lower, which is consistent with previous reports (S. babylonica and C. deodara had 7 and 19 EMF OTUs, respectively40,46). In addition, the species dilution curve of the number of samples (Fig. 1b) showed that the sampling amount in this study was insufficient to estimate the true EMF richness of each greening tree species. Therefore, further studies with adequate greening tree species sampling volumes in different UGSHs are required.

Basidiomycota richness in park green belts was significantly higher than that in roadside green belts, which might be due to the higher forest coverage and diversity in the park47, resulting in plant litter rich in lignin and cellulose. Basidiomycota can be effectively degraded and utilized to meet their own growth and reproduction needs48. This reflects the dominant position and important role of Basidiomycota in these habitats. Ascomycota richness in the roadside green belt was higher than that of Basidiomycota, which is consistent with P. sylvestris EMF diversity in sandy land49. Ascomycota EMF species is more adaptable to various environmental stresses50 and is likely the reason for Wilcoxina and Trichophaea dominance. In this study, EMF community composition was different among the different greening tree species. Habitats with high plant richness drives EMF richness25. EMF community structures in park green belts with higher plant diversity were more complex than those in roadside green belts. Although there are more common EMF among greening tree species at the genus or higher classification level, the OTU level is host-specific51,52. The spatial homogeneity of soil and vegetation increases with tourism disturbance53. Therefore, tourist disturbances might promote C. deodara and P. massoniana EMF community composition similarity at the genus level (seven common genus). Russula richness negatively correlated with the soil compaction gradient54. However, Russula was widespread in this study, and its richness was highest in P. massoniana, indicating that P. massoniana in the rhizosphere soil was less compacted and disturbed by tourist activities. The relative abundance of Wilcoxina and Oidiodendron in the roadside green belt was significantly higher than that in the park C. deodara, probably owing to enhanced adaptability to stressful environments, becoming the dominant species in this habitat.

Studying the EMF species diversity in urban greening trees enhance the public understanding of the ecological interactions between urban and natural environments. Such research can also aid in managing and improving urban ecological quality, and promote the diversity of ecological functions55. EMF diversity is mainly affected by the host plant type and soil environment8. EMF diversity in the park green habitat was P. massoniana > C. deodara > S. babylonica, and EMF diversity in park green belts was higher than that in roadside green belts, which might be due to the more complex composition and structure of vegetation communities in parks33 with higher diversity of cultivated non-native species and frequent conservation management (including regular fertilization, tillage, and watering). These human disturbances provide heterogeneous conditions for the greening tree species. The geographical environment and soil matrix of the parks are different and are also affected by the root exudates of adjacent plants56. This might selectively affect specific microbial communities in the rhizosphere of plants57, indirectly increasing nutrient availability for EMF, providing a broader niche for EMF growth and diversity, and shaping EMF diversity. Additionally, diversity was associated with high plant species richness58. A small number of unique EMF groups were observed in the non-native host plants C. deodara. This result is likely attributed to the wide compatibility between non-native host plants and native EMF59,60. Notably, EMF is the only group that tends to lose diversity owing to changes in urban land use61. In our study, C. deodara exhibited varying EMF diversity across different habitats owing to differences in land use and management patterns. This result suggests that the habitats conversion of host plants may be an important driving factor for the loss of EMF diversity. However, EMF in roadside green belts might be limited by other related factors such as single vegetation species (only C. deodara), shallow roots, nitrogen deposition caused by automobile exhaust emissions, and changes in temperature and humidity conditions62,63, which lead to EMF growth inhibition. C. deodara in the roadside greening habitat requires more frequent fertilization and irrigation, which reduces the dependence of plants on the absorption of nutrients and water by mycorrhizal fungi64,65. With the increase in soil compaction and the serious impact of human activities, the soil carbon deposition rate and the soil animals’ species (for example earthworms) content are affected, resulting in decreases in EMF diversity and host root infestation rate of C. deodara in roadside greening habitats38. In this study, the similarity of EMF communities among different greening tree species was low, due to the construction of EMF community dependence on both random and deterministic processes, and the diffusion limitation in the random process is the primary influencing factor; that is, the geographical distance hinders the diffusion of fungal propagules (spores and hyphae)35.

Conclusions

Overall, our study demonstrated significant differences in the composition and diversity of EMF communities among different greening tree species in two UGSHs. In addition, EMF diversity in the same greening tree species (C. deodara) was significantly affected in different UGSHs. UGSHs are urban functional lands and important habitats for urban biodiversity maintenance. Further studies that examine EMF diversity changes of other greening tree species from different perspectives of habitat interference are required to provide a scientific basis for healthy development of UGSHs ecology and the development of EMF agents for urban greening trees management.

Materials and methods

Study area

The study area is located in Huaxi District (106° 27–106° 52′ E, 26°11′–26° 34′ W), Guiyang City, Guizhou Province, China, which terrain is mainly mountainous and hilly, located in the east of Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau and the middle of Miaoling Mountains and belonged to the typical karst landform area. The area belongs to subtropical monsoon humid climate zone, the average annual rainfall approximately is 1178.3 mm, the average annual temperature is 15.7 °C, and the soil type is yellow. Zone vegetation type is evergreen broad-leaved mixed and coniferous forest. The tree species include P. massoniana, C. deodara, S. babylonica, Camphor and Ginkgo.

Sample collection and processing

In April 2023, the following tree species and sample plots were selected for analysis: three greening tree species in the Huaxi park green belt–C. deodara, P. massoniana, and S. babylonica, and one species in the roadside green belts of Jiaxiu South Road–C. deodara. The site conditions information was recorded and presented in Table 4. In the survey site, a total of 40 root samples were collected, 10 healthy host plants with relatively uniform diameters at breast height and separated by a minimum spatial distance of 3 m were randomly selected as sampling objects. For each greening tree, mycorrhizal root tips were collected using a root-cutting knife within a 1–1.5 m radius around the base of the tree trunk. Moreover, samples 15–20 cm in length from a 0–20 cm deep soil layer in two directions were traced from the trunk of the selected trees. Each root sample was placed in a plastic bag, stored on ice at 4 °C and transported to the laboratory. In the laboratory, samples were combined with dry silica gel and stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C until further analysis.

Table 4.

Basic information of different greening tree species in the plot.

| Plots | EMF hosts | Altitude | Longitude | Latitude | Diameter | Height |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roadside green belt | C. deodara | 1093 | 106° 39′ 39″ E | 26° 27′ 4″ N | 16.48 | 7.57 |

| Park green belt | C. deodara | 1098 | 106° 40′ 8″ E | 26° 26′ 1″ N | 20.16 | 8.24 |

| S. babylonica | 1088 | 106° 40′ 5″ E | 26° 26′ 9″ N | 19.98 | 6.97 | |

| P. massoniana | 1078 | 106° 40′ 29″ E | 26° 26′ 37″ N | 20.89 | 9.64 |

The collection of plant material in our study is licensed. This materials not stored in a publicly available herbarium.

Morphological and molecular identification of EMF

The root samples were extracted with tweezers and cut into 3–5 cm segments using scissors. After being washed repeatedly with tap water, the samples were transferred into a clean Petri dish with a small amount of water. Under the stereomicroscope (Mac Audi SMZ-171, Xiamen, China), the morphological classification was based on characteristics such as shape, size, branching, color and presence or absence of mycelium in mycorrhizal root tips66. The morphology and quantity of the mycorrhizal roots were recorded and photographed. Two to three root tips of each mycorrhizal were selected, placed into a centrifuge tube containing 200 µL of sterile water (3 replicates), and stored in a -20 °C freezer. Subsequently, two or three robust root tips were selected for extraction for species identification67. EMF DNA was extracted by modified cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) method. The primers ITS1-F (5′-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATATATGC-3′) were used to amplify the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products. The PCR system volume was 25 µL68. The PCR reaction conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min; denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s; annealing at 55 °C for 30 s; and extension at 72 °C for 60 s. This cycle was repeated for a total of 34 cycles, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. All PCR amplifications were analyzed using 2 µL of the sample through 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. After passing the test, the amplified products were sent to Sangon Bioengineering (Shanghai, China) Co., Ltd. for sequencing.

Data processing

The obtained DNA sequence was analyzed using Chromas (https://technelysium.com.au), and the low-quality sequence ends were trimmed and corrected. The two effective sequences of the same PCR product were spliced using SeqMan (https://www.dnastar.com). To preliminarily identify the relevant species, the spliced DNA sequence was compared against the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) database using BLAST, with a 97% sequence similarity threshold for OTUs classification. Then, phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining method in MEGA-X software (https://www.megasoftware.net), with a bootstrap value of 1000. Phylogenetic analysis was carried out to further determine its OTUs. OriginPro 2022 (https://www.originlab.com) was used to draw the cumulative curve of OTU sampling number and the histogram of mycorrhizal infestation rate, and the relative abundance diagram for the phylum and genus levels was drawn. Co-occurrence network analysis of EMF was conducted at the OTU level using Gephi 0.10.2 software (https://gephi.org), and the diversity index of EMF was calculated with R version 4.3.2. (https://cran.rstudio.com). The Jaccard and Sørenson indexes were used to evaluate the EMF diversity among host plants. The simplified calculation formula is as follows:

|

J and S represents Jaccard and Sørenson indexes, respectively; a and b represent two sets, respectively, and f represents the intersection between the two sets “a” and “b”. In this study, a and b refer to two greening tree species, respectively, and f represents the OTUs shared between the two greening tree species.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions for improving our manuscript. This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (NSFC) project (Grant Numbers 31660150 and 31960234).

Author contributions

Q.C.L. was responsible for article writing and data collation. Y.Q.C. was responsible for data collection. D.D.J. was responsible for experimental and data processing technical guidance. M.X. was responsible for revising the article, approving the final version, and acquiring funding. J.Z. was responsible for conceiving and designing the experiment, analyzing data, writing and revising the article, approving the final version, and acquiring funding.

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) with the primary accession code SUB14603063.

Code availability

The code used in this study is available in the supplementary material published online by the paper.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bosso, L. et al. Plant pathogens but not antagonists change in soil fungal communities across a land abandonment gradient in a Mediterranean landscape. Acta Oecol.78, 1–6 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassett, B. A. et al. Pulling apart the urbanization axis: Patterns of physiochemical degradation and biological response across stream ecosystems. Freshw. Sci.37, 653–672 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKinney, M. L. & Lockwood, J. L. Biotic homogenization: A few winners replacing many losers in the next mass extinction. Trends Ecol. Evol.14, 450–453 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haahtela, T. et al. The biodiversity hypothesis and allergic disease: World allergy organization position statement. World Allergy Organ.6, 3 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanski, I. et al. Environmental biodiversity, human microbiota, and allergy are interrelated. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.109, 8334–8339 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald, R. I. et al. Research gaps in knowledge of the impact of urban growth on biodiversity. Nat. Sustain.3, 16–24 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heinz, A., Deserno, L. & Reininghaus, U. Urbanicity, social adversity and psychosis. World Psychiatry12, 187–197 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aerts, R., Honnay, O. & Nieuwenhuyse, A. V. Biodiversity and human health: Mechanisms and evidence of the positive health effects of diversity in nature and green spaces. Br. Med. Bull.127, 5–22 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanhope, J., Breed, M. F. & Weinstein, P. Exposure to greenspaces could reduce the high global burden of pain. Environ. Res.187, 109641 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Twohig-Bennett, C. & Jones, A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environ. Res.166, 628–637 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grönroos, M. et al. Short-term direct contact with soil and plant materials leads to an immediate increase in diversity of skin microbiota. MicrobiologyOpen8, e645 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mckinney, M. L. Effects of urbanization on species richness: A review of plants and animals. Urban Ecosyst.11, 161–176 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selway, C. A. et al. Transfer of environmental microbes to the skin and respiratory tract of humans after urban green space exposure. Environ. Int.145, 106084 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Escobedo, F. J., Kroeger, T. & Wagner, J. E. Urban forests and pollution mitigation: Analyzing ecosystem services and disservices. Environ. Pollut.159, 2078–2087 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang, H. & Tassinary, L. G. Association between greenspace morphology and prevalence of non-communicable diseases mediated by air pollution and physical activity. Landsc. Urban Plan.242, 104934 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cusack, D. F., Silver, W. L., Torn, M. S., Burton, S. D. & Firestone, M. K. Changes in microbial community characteristics and soil organic matter with nitrogen additions in two tropical forests. Ecology.92, 621–632 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo, Y. et al. Impact of suburban cropland intensification and afforestation on microbial biodiversity and C sequestration in paddy soils. Land Degrad. Dev.35, 1234–1247 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strohbach, M. W. & Haase, D. Above-ground carbon storage by urban trees in Leipzig, Germany: Analysis of patterns in a European city. Landsc. Urban Plan.104, 95–104 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrios, E. Soil biota, ecosystem services and land productivity. Ecol. Econ.64, 269–285 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang, L., Zhang, L., Li, Y. & Wu, S. Water-related ecosystem services provided by urban green space: A case study in Yixing City (China). Landsc. Urban Plan.136, 40–51 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kabisch, N. Ecosystem service implementation and governance challenges in urban green space planning—The case of Berlin, Germany. Land Use Policy42, 557–567 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mills, J. G. et al. Urban habitat restoration provides a human health benefit through microbiome rewilding: The microbiome rewilding hypothesis. Restor. Ecol.25, 866–872 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mills, J. G. et al. Revegetation of urban green space rewilds soil microbiotas with implications for human health and urban design. Restor. Ecol.28, S322–S334 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pengthamkeerati, P., Motavalli, P. P. & Kremer, R. J. Soil microbial activity and functional diversity changed by compaction, poultry litter and cropping in a claypan soil. Appl. Soil Ecol.48, 71–80 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nugent, A. & Allison, S. D. A framework for soil microbial ecology in urban ecosystems. Ecosphere13, e3968 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiesura, A. The role of urban parks for the sustainable city. Landsc. Urban Plan.68, 129–138 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walter, V. R., Stephen, R. C. & Harold, A. M. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis. (ed. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment) 534 (Island, 2005).

- 28.Grigal, D. F. Effects of extensive forest management on soil productivity. For. Ecol. Manag.138, 167–185 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marshall, V. G. Impacts of forest harvesting on biological processes in northern forest soils. For. Ecol. Manag.133, 43–60 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mooney, S. J. & Nipattasuk, W. Quantification of the effects of soil compaction on water flow using dye tracers and image analysis. Soil Use Manag.19, 356–363 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romano, N., Lignola, G. P., Brigante, M., Bosso, L. & Chirico, G. B. Residual life and degradation assessment of wood elements used in soil bioengineering structures for slope protection. Ecol. Eng.90, 498–509 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore, T. L., Rodak, C. M. & Vogel, J. R. Urban stormwater characterization, control, and treatment. Water Environ. Res.89, 1876–1927 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nielsen, U. N., Osler, G. H. R., Campbell, C. D., Burslem, D. & Wal, R. V. The influence of vegetation type, soil properties and precipitation on the composition of soil mite and microbial communities at the landscape scale. J. Biogeogr.37, 1317–1328 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chazal, J. & Rounsevell, M. D. A. Land-use and climate change within assessments of biodiversity change: A review. Glob. Environ. Change19, 306–315 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang, Y. et al. Community assembly of endophytic fungi in ectomycorrhizae of betulaceae plants at a regional scale. Front. Microbiol.10, 3105 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar, J. & Atri, N. S. Studies on ectomycorrhiza: An appraisal. Bot. Rev.84, 108–155 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anthony, M. A. et al. Forest tree growth is linked to mycorrhizal fungal composition and function across Europe. ISME J.16, 1327–1336 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li, X. et al. Diversity of ectomycorrhizal fungal communities in four types of stands in Pinus massoniana plantation in the west of China. Forests.12, 719 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Azul, A. M., Castro, P., Sousa, J. P. & Freitas, H. Diversity and fruiting patterns of ectomycorrhizal and saprobic fungi as indicators of land-use severity in managed woodlands dominated by Quercus suber—A case study from southern Portugal. Can. J. For. Res.39, 2404–2417 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hrynkiewicz, K., Furtado, B. U., Szydɫo, J. & Baum, C. Ectomycorrhizal diversity and exploration types in Salix caprea. Int. J. Plant Biol.15, 340–357 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bainard, L. D., Klironomos, J. N. & Gordon, A. M. The mycorrhizal status and colonization of 26 tree species growing in urban and rural environments. Mycorrhiza.21, 91–96 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jumpponen, A., Jones, K., David Attox, J. & Yaege, C. Massively parallel 454-sequencing of fungal communities in Quercus spp. ectomycorrhizas indicates seasonal dynamics in urban and rural sites. Mol. Ecol.19, 41–53 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Otsing, E., Anslan, S., Ambrosio, E., Koricheva, J. & Tedersoo, L. Tree species richness and neighborhood effects on ectomycorrhizal fungal richness and community structure in boreal forest. Front. Microbiol.12, 264 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao, Q. & Yang, Z. L. Ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with two species of Kobresia in an alpine meadow in the eastern Himalaya. Mycorrhiza20, 281–287 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grierson, J., Flies, E. J., Bissett, A., Ammitzboll, H. & Jones, P. Which soil microbiome? Bacteria, fungi, and protozoa communities show different relationships with urban green space type and use-intensity. Sci. Total Environ.863, 160468 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wen, Z. et al. Ectomycorrhizal community associated with Cedrus deodara in four urban forests of Nantong in East China. Front. Plant Sci.14, 1226720 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lindahl, B. D. et al. Spatial separation of litter decomposition and mycorrhizal nitrogen uptake in a boreal forest. New Phytol.173, 611–620 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sánchez, C. Lignocellulosic residues: Biodegradation and bioconversion by fungi. Biotechnol. Adv.27, 185–194 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo, M. et al. Community composition of ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with Pinus sylvestris var Mongolica plantations of various ages in the horqin sandy land. Ecol. Indic.110, 105860–105861 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun, Q., Liu, Y., Huatao, Y. & Lian, B. The effect of environmental contamination on the community structure and fructification of ectomycorrhizal fungi. MicrobiologyOpen6, 396 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Linde, S. V. et al. Environment and host as large-scale controls of ectomycorrhizal fungi. Nature558, 243–248 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang, T. et al. Saprotrophic fungal diversity predicts ectomycorrhizal fungal diversity along the timberline in the framework of island biogeography theory. ISME Commun.1, 15 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarah, P. & Zhevelev, H. M. Effect of visitors’ pressure on soil and vegetation in several different micro-environments in urban parks in Tel Aviv. Landsc. Urban Plan.83, 284–293 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hartmann, M. et al. Resistance and resilience of the forest soil microbiome to logging-associated compaction. ISME J.8, 226–244 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Newbound, M., Mccarthy, M. A. & Lebel, T. Fungi and the urban environment: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan.96, 138–145 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eisenhauer, N. et al. Root biomass and exudates link plant diversity with soil bacterial and fungal biomass. Sci Rep.7, 44641 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vranova, V., Rejsek, K., Skene, K. R., Janous, D. & Formanek, P. Methods of collection of plant root exudates in relation to plant metabolism and purpose: A review. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci.176, 175–199 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fei, S. et al. Coupling of plant and mycorrhizal fungal diversity: Its occurrence, relevance, and possible implications under global change. New Phytol.234, 1960–1966 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.O’Hanlon, R. & Harrington, T. J. Similar taxonomic richness but different communities of ectomycorrhizas in native forests and non-native plantation forests. Mycorrhiza.22, 371–382 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ohanlon, R., Harrington, T., Berch, S. & Outerbridge, R. Comparisons of macrofungi in plantations of sitka spruce (Picea Sitchensis) in its native range (British Columbia, Canada) versus non-native range (Ireland and Britain) show similar richness but different species composition. Can. J. For. Res.43, 450–458 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schmidt, D. J. et al. Urbanization erodes ectomycorrhizal fungal diversity and may cause microbial communities to converge. Nat. Ecol. Evol.1, 123 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ahn, J. et al. Characterization of the bacterial and archaeal communities in rice field soils subjected to long-term fertilization practices. J. Microbiol.50, 754–765 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Holden, S. R. & Treseder, K. K. A meta-analysis of soil microbial biomass responses to forest disturbances. Front. Microbiol.4, 163 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Augé, R. Water relations, drought and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Mycorrhiza11, 3–42 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zheng, Y., Hu, H., Guo, L., Anderson, I. C. & Powell, J. R. Dryland forest management alters fungal community composition and decouples assembly of root- and soil-associated fungal communities. Soil Biol. Biochem.109, 14–22 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Agerer, R. Colour Atlas of Ectomycorrhizae. (ed. Agerer, R.) 58 (Einhorn-Verlag, 1997).

- 67.White, T. et al. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications (ed. Michael, A. I.) 315–322 (Academic, 1990).

- 68.Gardes, M. & Bruns, T. D. Its primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes-application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Ecol.2, 113–118 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) with the primary accession code SUB14603063.

The code used in this study is available in the supplementary material published online by the paper.