Abstract

Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) encodes a 30-kDa movement protein (MP) which enables viral movement from cell to cell. It is, however, unclear whether the 126- and 183-kDa replicase proteins are involved in the cell-to-cell movement of TMV. In the course of our studies into TMV-R, a strain with a host range different from that of TMV-U1, we have obtained an interesting chimeric virus, UR-hel. The amino acid sequence differences between UR-hel and TMV-U1 are located only in the helicase-like domain of the replicase. Interestingly, UR-hel has a defect in its cell-to-cell movement. The replication of UR-hel showed a level of replication of the genome, synthesis, and accumulation of MP similar to that observed in TMV-U1-inoculated protoplasts. Such observations support the hypothesis that the replicase coding region may in some fashion be involved in cell-to-cell movement of TMV.

Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) has a positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome that encodes four proteins (7). The 126- and 183-kDa replicases are translated directly from the genomic RNA using the same first initiation codon. The movement protein (MP) and the coat protein (CP) are translated from their respective subgenomic mRNAs, which are synthesized during the replication cycle. Functions have been assigned to the genes mainly according to the phenotypic lesions of deletion or substitution mutants of each protein. It has been shown that the 126- and 183-kDa replicases are involved in intracellular replication (12), that the MP is involved in cell-to-cell movement (5, 18), and that the CP is involved in long-distance movement (9, 19). TMV requires MP but not CP for cell-to-cell movement. It is as yet unclear whether or not replicase directly takes part in cell-to-cell movement, since cell-to-cell movement prior to replication has not been observed.

TMV-R, the rakkyo strain, which exhibits distinct host range differences from the common strain of TMV-U1, was recently reported (14). TMV-R infects rakkyo (Allium chinense), a monocot host that TMV-U1 is unable to infect. TMV-R causes only latent infection of Nicotiana tabacum cv. Bright Yellow (BY) in inoculated leaves, whereas TMV-U1 infects BY tobacco plants systemically and induces mosaic virus symptoms (14). The overall sequence homologies between TMV-U1 and TMV-R are 94% at the nucleotide level and 96 to 98% at the amino acid sequence level of the encoded proteins (3). Chen et al. constructed a series of chimeric viruses between the two strains (4). When chimeric viruses in which the replicase domain was derived from TMV-U1 were used, mosaic virus symptoms were observed on BY tobacco plants. In contrast, infection using chimeric viruses in which the replicase proteins had been derived from TMV-R resulted in only latent infection in BY tobacco plants with inoculated leaves. The phenotypes of all the chimeric viruses on BY tobacco plants were shown to be unaffected by the mixed origins of MP or CP sequences, whether the sequence was TMV-U1 or TMV-R derived. The difference in the pathogenicity of TMV-U1 and TMV-R for BY tobacco plants was determined by the replicase protein (4).

The 126-kDa replicase protein contains two domains showing similarities to the methyltransferase (1, 2) and helicase (1, 6) domains commonly recognized in replicases of various RNA viruses (Fig. 1). There is a relatively nonconserved region between the two domains (Fig. 1). The 183-kDa replicase is translated by read-through of the amber termination codon of the 126-kDa protein. The read-through region contains so-called polymerase domains (11), which can also be found in replicase proteins of various RNA viruses (Fig. 1). To understand the involvement of each domain in host range determination, we constructed various viruses which would express chimeric replicases of TMV-U1 and TMV-R. The chimeric viruses possess different combinations of such domains in addition to the nonconserved regions from TMV-U1 or TMV-R.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the genomic organization of the viruses studied. (A). TMV-U1 and TMV-R parental viruses and derived chimeric viruses. (B) Viruses in which CPs were replaced with GFP. Gray boxes in the chimeric viruses indicate portions of sequence derived from the TMV-R genome. Vertical lines in the open reading frames indicate the locations of amino acid differences between TMV-U1 and TMV-R. Hatched boxes in panel B indicate inserted GFP genes.

The genomic organization of the constructed chimeric viruses (UR-met, UR-var, UR-hel, and UR-pol) is shown in Fig. 1. TMV-U1 and TMV-R were obtained from previously described sources (3, 10). cDNA clones of chimeric viruses were constructed by replacing the SmaI (nucleotide [nt] 258)-MluI (nt 811), MluI-NsiI (nt 2354), NsiI-BamHI (nt 3332), and BamHI-HindIII (nt 5080) fragments of TMV-U1 with corresponding fragments from TMV-R. The sequences of the fragments contain 5, 15, 12, and 7 amino acid differences in comparison to those of TMV-U1, respectively. Transcription (10), protoplast handling, and RNA inoculation into protoplasts (20, 23) or plants (12, 17) were performed essentially as described previously.

The infectivity of the four viruses was verified by sodium dodecyl sulfate–12.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis detection of CP in inoculated BY-2 protoplasts (22) at 16 h postinoculation (hpi). Staining with Coomassie brilliant blue revealed that these chimeric viruses accumulated CP to levels similar to those of TMV-U1 (data not shown), demonstrating that chimeric viruses did not lose infectivity in protoplasts.

Inability of cell-to-cell movement of UR-hel.

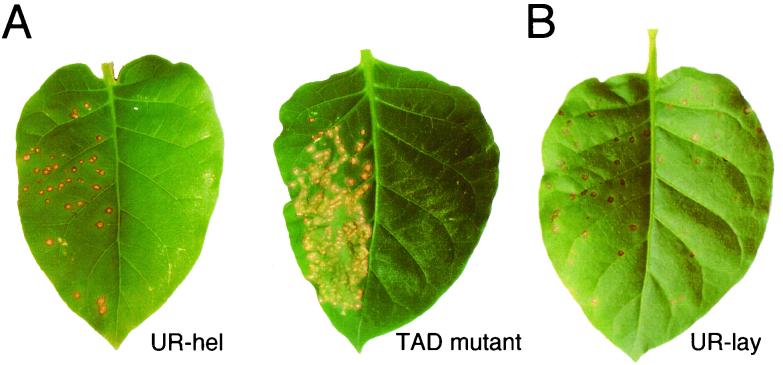

The infectivity of chimeric viruses in plants was checked by noting the formation of local lesions on N. tabacum cv. Xanthi-nc leaves. Xanthi-nc has a dominant inherited gene, N, which confers resistance against tobamoviruses by triggering a hypersensitive response, while the virus retains viability. Analysis of many artificially constructed MP mutants showed that the appearance of local lesions reflects cell-to-cell movement of the virus (18). Contrary to expectations, UR-hel caused no local lesions, whereas TMV-U1 did cause local lesions (4 days postinoculation [dpi]) (Fig. 2A), as did UR-met, UR-var, and UR-pol (data not shown). Our observations suggest that the cell-to-cell movement of UR-hel was very low or defective.

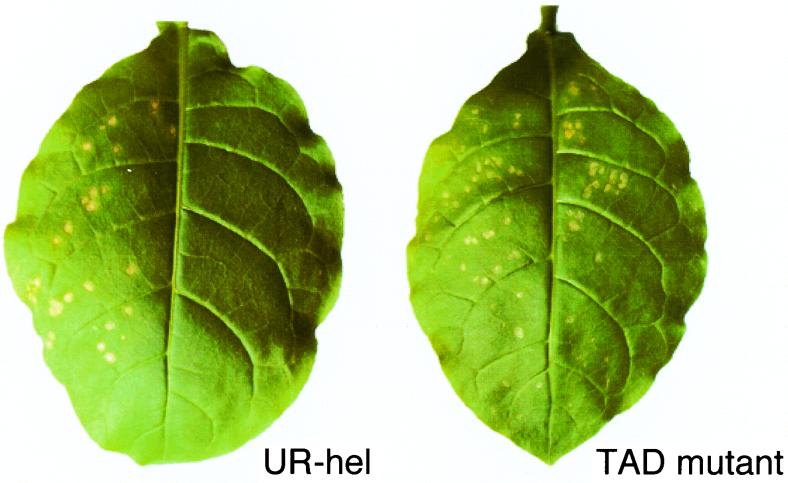

FIG. 2.

Assay of the ability for cell-to-cell movement of viruses on Xanthi-nc leaves carrying the N gene (4 dpi). All left halves of the leaves were inoculated with TMV-U1 (positive control). (A) Right halves of each Xanthi-nc leaf were inoculated with UR-hel or the TAD 16 mutant (13). TMV-U1 caused local lesions on the left sides, but no local lesions appeared on the right halves of both leaves. (B) The right half of a Xanthi-nc leaf was inoculated with UR-lay. Local lesions appeared on both halves of the leaf.

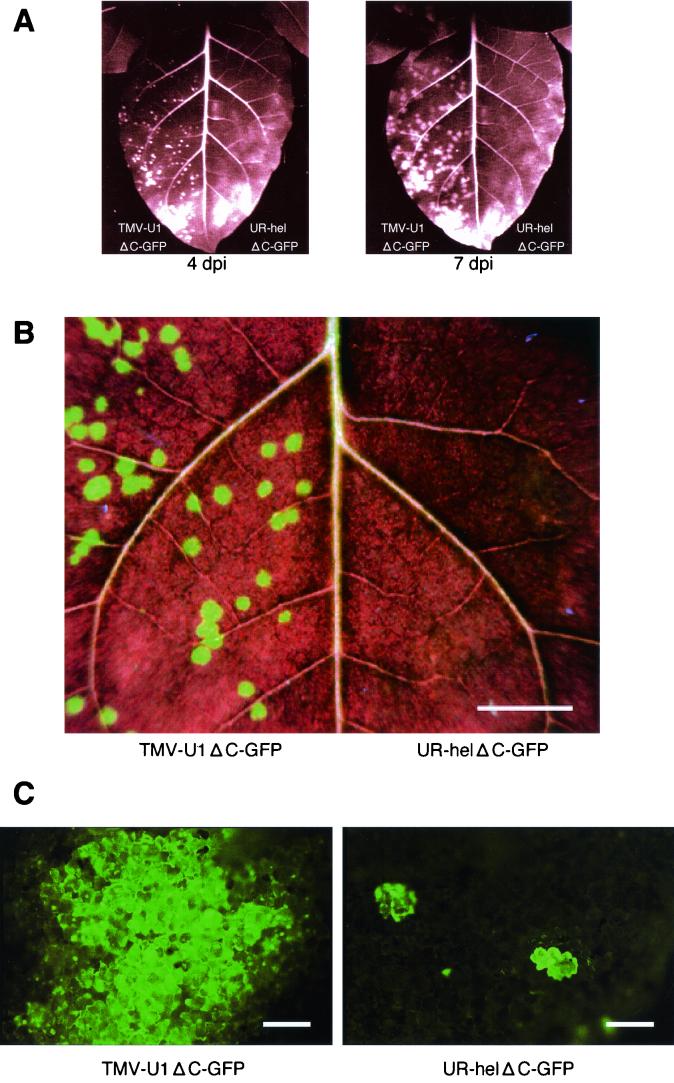

A detailed analysis, focusing on cell-to-cell movement, was carried out on UR-hel. To monitor viral movement in planta, the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene was inserted in place of the CP gene, creating a UR-helΔC-GFP construct (Fig. 1B). We already had a counterpart construct, U1ΔC-GFP (8), from the TMV-U1 genome in which the CP gene had been replaced with the GFP gene. Tobamovirus can move from one cell to another on inoculated leaves without CP; thus, these viruses would express GFP and show the spread of fluorescent cells following infection. GFP expression was observed on U1ΔC-GFP-inoculated Samsun-nn tobacco leaves (the systemic host) as circles with diameters of approximately 1 mm (Fig. 3A and B). Fluorescent areas were seen to expand thereafter. In contrast, UR-helΔC-GFP did not show any visible fluorescent circles or spots (4 and 7 dpi) (Fig. 3A and B). Subsequently, we observed UR-hel-inoculated leaves using fluorescence microscopy. Wright et al. reported that a mutant deficient in cell-to-cell movement, TMV-GFPΔMP, in which the CP gene had been replaced with a GFP gene, showed GFP expression only in initially infected cells on inoculated leaves (23). GFP expression of UR-helΔC-GFP was barely detected in a single cell (or in a couple of cells at most) (Fig. 3C). The shapes and the areas of fluorescence-positive parts were almost the same as those reported by Wright et al. (23). Taken together with the available experimental data (Fig. 2A), these results showed that UR-helΔC-GFP can replicate in initially infected cells but cannot move out of the cells. It is likely that UR-helΔC-GFP (and UR-hel) has little, if any, cell-to-cell movement ability.

FIG. 3.

Viral movement demonstrated by GFP expression on systemic hosts. (A) Photos of the same inoculated leaf were taken at 4 and at 7 dpi. The left half of the Samsun-nn leaf was inoculated with U1ΔC-GFP, and the right half was inoculated with UR-helΔC-GFP. (B) Detached leaf (treated as described for panel A) was observed at 4 dpi at a higher magnification. The left half of the Samsun-nn leaf was inoculated with U1ΔC-GFP, and the right half was inoculated with UR-helΔC-GFP. Bar, 10 mm. (C) Visualization of each leaf half by fluorescence microscopy at 4 dpi. GFP induced by UR-helΔC-GFP challenge was observed only in a single cell (or in a couple of cells at most). Bars, 200 μm.

We made as many as eight independent clones of UR-hel, none of which caused any local lesions on Xanthi-nc tobacco leaves (data not shown). In addition, we constructed UR-lay, the “true revertant” clone, by replacing the NsiI-BamHI restriction fragment of UR-hel with that of the corresponding fragment of TMV-U1. UR-lay caused local lesions, as did TMV-U1, on Xanthi-nc tobacco leaves (Fig. 2B). This result confirmed that UR-hel possessed no other substitutions outside the NsiI-BamHI fragment. The novel phenotype of UR-hel is not caused by a change in the MP sequence.

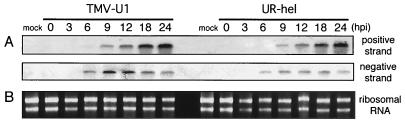

UR-hel and TMV-U1 have similar protoplast replication levels.

It is conceivable that UR-hel contains amino acid sequence changes in the replicase that may cause low levels of replication and inefficient cell-to-cell movement. We thus checked the replication level of UR-hel in protoplasts and compared it to that of TMV-U1 by employing Northern analysis. Total RNA was extracted from protoplasts with the RNeasy plant minikit (Qiagen) at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 hpi. RNA blotting was performed with formaldehyde-agarose gels and Hybond N+ (Amersham). For RNA detection, digoxigenin-labeled hybridization probes were employed for positive- and negative-strand RNA (nt 5713 to 6191), generated using the DIG-RNA labeling kit (Roche). Bands were detected by anti-digoxigenin-alkaline phosphatase Fab fragments (Roche) and a BCIP-NBT (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate–nitroblue tetrazolium) phosphatase substrate system (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories). Northern analysis showed that UR-hel replicated to levels similar to those of TMV-U1 during the time period studied (Fig. 4). We infer that the defect in cell-to-cell movement of UR-hel was not caused by a low level of replication.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of replication efficiencies of TMV-U1 and UR-hel. The total RNA (0.2 μg/lane) extracted from protoplasts was separated, blotted, and analyzed. (A) Northern analysis of replication of TMV-U1 and UR-hel in inoculated protoplasts using RNA probes for positive- and negative-strand TMV RNA (nt 5713 to 6191). The replication level of UR-hel was similar to that of TMV-U1. (B) rRNA detected by ethidium bromide staining.

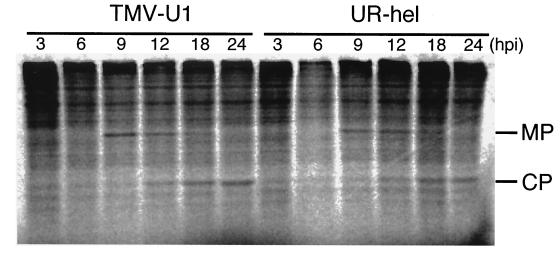

There are several reports which have shown that a low level of MP synthesis reduces the cell-to-cell movement ability of TMV (15, 16, 21). Due to the low level of synthesis and accumulation, MP mRNA of TMV-U1 and UR-hel was not detected by Northern analysis. Whether the synthesis of UR-hel MP differs from that of TMV-U1 needed to be determined. Therefore, we analyzed the synthesis of MP and CP in protoplasts and focused on the level of MP production. Protoplasts inoculated with TMV-U1 or UR-hel were pulse-labeled with a [35S]methionine-[35S]cysteine protein-labeling mixture (NEN) at 0.1 MBq/ml for 30 min at 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 hpi. Proteins were extracted from protoplasts and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate–12.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. 35S-labeled MP and CP bands were detected and traced quantitatively using a Fuji Image Analyzer. UR-hel synthesized both MP and CP to levels similar to those of TMV-U1 at each of the times investigated (Fig. 5). If the CP of each virus accumulated to similar levels at the same times postinoculation, then the data would further support the MP data suggesting that the subgenomic RNAs were likely synthesized to similar levels by both viruses during replication. We can exclude the possibility that defects in the cell-to-cell movement of UR-hel were caused by the low production of MP.

FIG. 5.

Pulse-labeling analysis of the synthesis of MP and CP in TMV-U1- and UR-hel-inoculated protoplasts over time. Inoculated protoplasts were metabolically labeled with a [35S]methionine-[35S]cysteine protein-labeling mixture (NEN) at 0.1 MBq/ml for 30 min, starting from the time indicated at the top of each lane. UR-hel synthesized MP and CP at levels similar to those of TMV-U1.

UR-hel could not be rescued by MP supply in trans

We have investigated whether defects in cell-to-cell movement of UR-hel can be complemented by MP supplied in trans. Since the transgenic tobacco line 2005 expresses TMV-U1 MP from the transgene, we attempted to complement in trans the defect in the cell-to-cell movement of mutants. For example, the TAD 16 mutant (13), a virus that has a three-amino-acid deletion in the MP coding region, caused local lesions on tobacco line 2005 leaves but not on Xanthi-nc leaves (Fig. 2A and 6). On the other hand, UR-hel caused local lesions neither on Xanthi-nc nor on tobacco line 2005 plants (Fig. 2A and 6). This result indicates that the defect of cell-to-cell movement in UR-hel cannot be rescued by MP supplied in trans.

FIG. 6.

In trans supply of MP from tobacco line 2005 plant carrying the N gene cannot complement the UR-hel defect in cell-to-cell movement (4 dpi). The left half of each leaf was inoculated with TMV-U1. The right half of each leaf was inoculated with UR-hel or the TAD 16 mutant (13). The transgenic line 2005 expresses TMV-U1 MP constitutively. Leaves inoculated with the TAD 16 mutant showed local lesions, but leaves inoculated with UR-hel showed no local lesions.

Additionally, we found a unique virus, designated UR-hel, among these chimeric viruses. We have confirmed that the MP sequence or production of UR-hel is identical to that of TMV-U1. Also, UR-hel could replicate to levels similar to those of U1 in protoplasts. Moreover, UR-hel did not cause local lesions even on tobacco line 2005 leaves, which constitutively expressed MP. The defect in cell-to-cell movement was not caused by MP, but it is reasonable to suspect that TMV replicase is involved in cell-to-cell movement. We plan to investigate how the replicase acts in cell-to-cell movement.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Kawakami for critically reviewing and L. Knight for reading the manuscript. We also thank R. N. Beachy for providing pU3/12-4, pU1ΔC-GFP, the TAD mutant, and the tobacco line 2005 expressing a TMV MP.

This work was supported in part by “Molecular Mechanisms of Plant-Pathogenic Microbe Interaction,” a grant-in-aid for scientific research on priority area (A) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (no. 08680733) to Y.W., and by a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (RFTF96L00603) to Y.W.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahola T, den Boon J A, Ahiquist P. Helicase and capping enzyme active site mutations in brome mosaic virus protein 1a cause defects in template recruitment, negative-strand RNA synthesis, and viral RNA capping J. Virol. 2000;74:8803–8811. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.19.8803-8811.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahola T, Laakkonan P, Vlhinen H, Kääriälnen L. Critical residues of Semliki Forest virus RNA capping enzyme involved in methyltransferase and guanylyltransferase-like activities. J Virol. 1997;71:392–397. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.392-397.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen J, Watanabe Y, Sako N, Ohshima K, Okada Y. Complete nucleotide sequence and synthesis of infectious in vitro transcripts from a full-length cDNA clone of a rakkyo strain of tobacco mosaic virus. Arch Virol. 1996;141:885–900. doi: 10.1007/BF01718163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen J, Watanabe Y, Sako N, Ohshima K, Okada Y. Mapping of host range restriction of the rakkyo strain of tobacco mosaic virus in Nicotiana tabacum cv. Bright Yellow. Virology. 1996;226:198–204. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deom C M, Oliver M J, Beachy R N. The 30-kilodalton gene product of tobacco mosaic virus potentiates virus movement. Science. 1987;237:389–394. doi: 10.1126/science.237.4813.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez A, Lain S, Garcia J. RNA helicase activity of the plum pox potyvirus Cl protein expressed in Escherichia coli. Mapping of an RNA binding domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:1327–1332. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.8.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goelet P, Lomonossoff G P, Butler P J G, Akam M E, Galt M J, Karn J. Nucleotide sequence of tobacco mosaic virus RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:5818–5822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.19.5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helnlein M, Epel B L, Padgett H S, Beachy R N. Interaction of tobamovirus movement proteins with the plant cytoskeleton. Science. 1995;270:1983–1985. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5244.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hilf M E, Dawson W O. The tobamovirus capsid protein functions as a host-specific determinant of long-distance movement. Virology. 1993;193:106–114. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holt C A, Beachy R N. In vivo complementation of infectious transcripts from mutant tobacco mosaic virus cDNAs in transgenic plants. Virology. 1991;181:109–117. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90475-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong Y, Hunt A. RNA polymerase activity catalyzed by a potyvirus-encoded RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Virology. 1996;226:146–151. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishikawa M, Meshi T, Motoyoshi F, Takamatsu N, Okada Y. In vitro mutagenesis of the putative replicase genes of tobacco mosaic virus. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:8291–8305. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.21.8291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahn T W, Lapidot M, Heinlein M, Reichel C, Cooper B, Gafny R, Beachy R N. Domains of the TMV movement protein involved in subcellular localization. Plant J. 1998;15:15–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwon S-B, Sako N. A new strain of tobacco mosaic virus infecting rakkyo (Allium chinense G. don) Ann Phytopathol Soc Jpn. 1994;60:36–44. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehto K, Dawson W O. Replication, stability, and gene expression of tobacco mosaic virus mutants with a second 30K ORF. Virology. 1990;175:30–40. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90183-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehto K, Grantham G L, Dawson W O. Insertion of sequences containing the coat protein subgenomic RNA promoter and leader in front of the tobacco mosaic virus 30K ORF delays its expression and causes defective cell-to-cell movement. Virology. 1990;174:145–157. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90063-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meshi T, Watanabe Y, Saito T, Sugimoto A, Maeda T, Okada Y. Function of the 30kd protein of tobacco mosaic virus: involvement in cell-to-cell movement and dispensability for replication. EMBO J. 1987;6:2557–2563. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02544.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meshi T, Ohno T, Okada Y. Nucleotide sequence and its character of cistron coding for the 30K protein of tobacco mosaic virus (OM strain) J Biochem. 1982;91:1441–1444. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a133833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saito T, Yamanaka K, Okada Y. Long-distance movement and viral assembly of tobacco mosaic virus mutants. Virology. 1990;176:329–336. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe Y, Meshi T, Okada Y. Infection of tobacco protoplasts with in vitro transcribed tobacco mosaic virus RNA using an improved electroporation method. FEBS Lett. 1987;219:65–69. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watanabe Y, Morita N, Nishiguchi M, Okada Y. Attenuated strains of tobacco mosaic virus reduced synthesis of a viral protein with a cell-to-cell movement function. J Mol Biol. 1987;194:699–704. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanabe Y, Ohno T, Okada Y. Virus multiplication in tobacco protoplasts inoculated with tobacco mosaic virus RNA encapsulated in large unilamellar vesicle liposomes. Virology. 1982;120:478–480. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(82)90048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wright K M, Duncan G H, Pradel K S, Carr F, Wood S, Oparka K J, Kruz S S. Analysis of the N gene hypersensitive response induced by a fluorescently tagged tobacco mosaic virus. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:1375–1385. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.4.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]