Abstract

Introduction

Ensuring optimal blood transfusion practices relies on a robust expertise base that is indispensable across various professional fields. Recognizing this imperative, the current study aims to assess the knowledge levels of healthcare personnel and enhance transfusion quality through targeted continuing training initiatives.

Methods

The preliminary survey was based on an anonymous questionnaire and we used correct response rate (CRR) as the main parameter evaluating the baseline level of knowledge. Then blood transfusion education sessions which focused on transfusion shortcomings were carried out. Finally, we assessed the impact of this training on the baseline education.

Results

From the total of 789 questionnaires distributed, we garnered 331 responses 23 from healthcare staff. The overall CRR for questions related to transfusion procedure knowledge was 33%. Notably, the per-transfusion step exhibited the highest control with CRR of 55% while noticeable gaps were observed in the pre-transfusion (CRR = 22%) and post-transfusion (CRR = 13%) phases. Profession wise variations in CRR were evident, with nurses recording the lowest percentage (CRR = 29%) compared to physicians (CRR = 39%) and technicians (CRR = 34%). Substantial differences were observed in the interpretation of Ultimate Control in the Patient's Bed (UCPB) among professions, especially affecting ABO identity, compatibility, and incompatibility cases. Following the blood transfusion training, attended by 105 participants, only 99 participants responded to the questionnaire post-training, expressing high satisfaction with the covered modules (80%). The knowledge enhancement encompassed all transfusion phases and the interpretation of clinical cases, notably ABO compatibility. Overall, there was a significant improvement in CRR from 33 to 53% (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the evaluation of knowledge should be carried out on a continuous manner in order to detect gaps in the professional sector and to ensure the effectiveness of training through well-targeted educational programs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12288-024-01778-y.

Keywords: Blood Transfusion, Knowledge, Education, Health Personnel

Introduction

Blood transfusion is a complex therapy, essential to patient's care and recognised as an important part of clinical practice worldwide. Therefore, the strict application of recommendations regarding good transfusion practice as well as the appropriate organisation of the different elements of the transfusion process, are fundamental to ensure patient safety [1].

Although the administration of blood components is a life-saving therapeutic tool, it is always associated with risks and human errors can be life-threatening or lead to death [2–5].Despite efforts and strict security measures, incidents during the blood transfusion still occur and some serious reactions identified were preventable, suggesting additional awareness may be beneficial [6, 7]. Therefore, a good level of expertise is an obligatory condition for any type of professional activity in order to apply good blood transfusion practices and prevent transfusion accidents [8, 9].

The present study aims to assess the knowledge of healthcare staff in order to document the level of basic formation with the goal of improving the quality of transfusions and the well-being of patients throughout a targeted continuing training.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Data Collection

This study was a descriptive research conducted at Fattouma Bourguiba Hospital in Monastir in Tunisia to evaluate knowledge related to blood transfusion before and after training.

In the first step, a preliminary survey aimed at evaluating the baseline level of blood transfusion knowledge of the health personnel. This survey was based on an anonymous questionnaire (annexe 1) which was distributed manually for individual response within 48 h. The participation was voluntary and the respondents were physicians, anaesthetic technicians and nurses implicated in blood transfusion.

The questionnaire consisted on 34 questions:

Section I (questions 1 to 3) referred to the professional status of participants, the training received and their satisfaction level;

Section II (questions 4 to 26) concerned the basic knowledge of transfusion procedures (pre-, per- and post-transfusion phases): The pre-transfusion phase comprises patient assessment, blood product selection and consent. During the per-transfusion phase, patient identification, blood product compatibility verification, and continuous monitoring take place. The post-transfusion phase involves monitoring for adverse reactions and documenting transfusion details.

Section III (questions 27 to 34) was related to eight clinical situations of which ultimate control in the patient’s bed was interpreted.

We used correct response rate (CRR) as the main evaluation parameter for each question and the answer was considered correct if all items were exact.

Blood transfusion education sessions were carried out by the laboratory and blood bank team in the light of the pre-training knowledge results. It focused on transfusion shortcomings, identified at the end of the first assessment step.

The training sessions included two main sections:

The first sectionconsisted on blood transfusion education related to transfusion procedure;

The second section was practical and comprised demonstrations of Ultimate control in the patient’s bed (UCPB) and interpretations of clinical cases regarding ABO blood groups.

In the last step we assessed the impact of the blood transfusion training on the baseline knowledge through the same questionnaire (annexe 1).The health care staff who participated in pre-training knowledge assessment was excluded. Thus we compared responses of two different groups of participants before and after training.

Data Analysis

After receiving the responses, data were entered in SPSS 20.0 software to be statistically analysed. The results were expressed in number and percentages. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov was used to test the distribution of quantitative variables which compared to the normal distribution.

If the distribution was Gaussian comparison between groups was carried out by Student Test (2groups) and ANOVA Test (> 2 groups). If the distribution was non-Gaussian, the differences between the groups were analysed by U Mann Whitney’s test (2groups) and Kruskall Wallis test (> 2 groups).

A p value less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Pre-Training Knowledge Assessment

Of the 789 questionnaires which were distributed, only 331 responded to the questionnaire with an overall return rate of 42%. The participants were 99 physicians (30%), 210 nurses (63%) and 22 anaesthetic technicians (7%).

The overall correct response rate (CRR) for questions about the basic knowledge of transfusion procedure (pre-, per- and post-transfusion phases) was 33%. The per-transfusion step was the most controlled by health care staff with CRR of 55%. The CRR for the pre-transfusion and post-transfusion phases were 22% and 13% respectively.

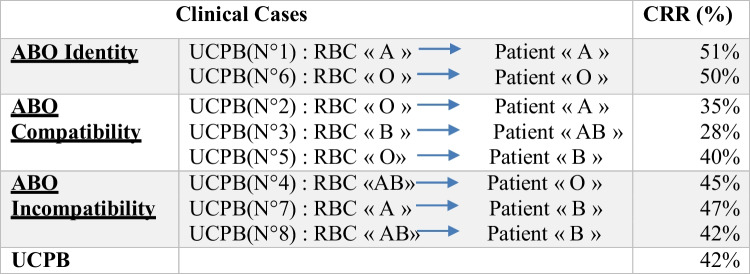

Results of interpretations of the ultimate control in the patient's bed (UCPB) are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pre-training CRR in the interpretation of the ultimate control in the patient's bed (UCPB)

The CRR of questions varied by profession, nurses reported the lowest percentage of 29% versus 39% and 34% respectively for physicians and technicians, this difference was statistically significant (p < 0.001) for the pre- and per-transfusion steps. But the variation between the CRR of the post-transfusion step was not different (p = 0.433). Thus the baseline knowledge for the post transfusion step highlights overall gaps for physicians (CRR = 18%), technicians (9%) and nurses (11%).Besides, there was a statistically significant difference (p = 0.001) in the interpretation of Ultimate control in the patient’s bed (UCPB) between professions with lower CRR for nurses (30% versus 64% for physicians and 70% for anaesthetic technicians). Indeed, this difference in UCPB interpretation was noted in ABO identity (p = 0.001), ABO compatibility (p = 0.001) and ABO incompatibility (p = 0.001) cases.

Impact of Blood Transfusion Training

A total of 105 attended to the blood transfusion training which covered the UCPB and the different steps of transfusion, with an emphasis on the pre- and post-transfusion phases. Only 99 participants answered the questionnaire after the training session. The participants were 45physicians (45.5%), 47nurses (47.5%) and 7 technicians (7%).The participants were mostly satisfied with the modules covered (80%). The comparison of CRRs before and after training showed an overall change in CRR from 33 to 53% (p < 0.001).

This improvement in blood transfusion knowledge included the pre, per and post transfusion phases, the results of which are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of CRR before and after training

| Phases | CRR Before training | CRR After training | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-transfusion phase | 22% | 46% | < 0.001 |

| Per-transfusion phase | 55% | 71% | < 0.001 |

| Post-transfusion phase | 13% | 30% | < 0.001 |

CRR: correct response rate.

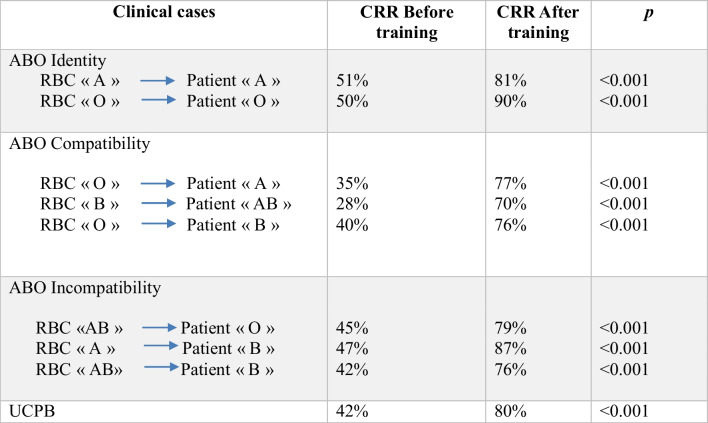

The improvement included also the interpretation of clinical cases concerning the ABO compatibility as mentioned in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of CRR about the ABO compatibility before and after training

CRR: correct response rate; RBC: Red Blood Cells; UCPB: ultimate control in the patient's bed.

Discussion

To assess the baseline knowledge of blood transfusion, an anonymous questionnaire was distributed manually to medical and paramedical staff. The questionnaire is one of the tools used usually for assessment and improvement of professional practices.

In the present study, the questionnaires were distributed leaving participants 48 h to respond. This given time has double advantage, it gives the opportunity to reflect on the different questions and increase the cooperation of the participants.

However, the lack of control of filling out the questionnaire may have limitations as the respondents could look for information before responding to questions, this may overestimate the baseline knowledge. However according to Gouëzec et al. [8], this point is not a limiting factor, contrarily, the return to the resource documents before answering questions should highlight the availability of documentation.

The questionnaires in our study were distributed manually, this increased the rate of return which was 42% compared to 16% in the study done by Gouëzec et al. during which the distribution of questionnaire was mixed [8].

Because we believe that the assessment of the baseline knowledge should concern all the team involved directly or indirectly in blood transfusion, we included in this survey, physicians, nurses and technicians in order to improve our transfusion practice. Other studies which interested to the baseline knowledge included either physicians or nurses only; this approach gives a partial idea of the shortcoming in transfusion [10–12].

The assessment of blood transfusion baseline knowledge is a necessary step before any training in order to highlight the gaps and improve the different shortcoming. In our study we found a general lack of transfusion knowledge, thus the mean overall CRR was 33%, this finding are consistent with the study of Arinsburg et al. [13], which had an overall CRR of 31.4%, and the team of Salem-Schatz et al. [14] which interviewed only physicians, their mean score of correct answers was between 30 and 40%.

The per-transfusion stage was the most controlled part by all the staff with a CRR of the order of 55%, this finding can be explain by the fact that the participants have a better handle on the blood transfusion experience and the routine and they are more focused on the process of transfusion itself and neglected both pre-transfusion and post-transfusion steps.

Our survey have shown that there is a definite difference between professions of which nurses reported the lowest CRR of 29% versus 39% for physicians, this difference was statistically significant (p < 0.001).Such study has also highlighted a lack of nursing staff in blood transfusion [11, 12].

ABO-incompatible blood transfusion is a rare life-threatening event which should be prevented by transfusion training. In the present study, respondents performed poorly in the interpretation of clinical cases concerning ABO incompatibility as only 45% of them stated that a patient with blood group "O" cannot be transfused with type "AB" RBCs, 47% of the respondents mentioned that a patient with blood group "B" cannot be transfused with type "A" RBCs and 42% of the participants answered that a patient with blood group "B" cannot be transfused with "AB" RBCs i.e. more than half of the respondents validate an ABO incompatibility which exposes to a serious incident putting the patients' life in danger; This catastrophic result is largely due to inadequate transfusion training [6, 7].

Of the 99 participants included in the after training survey, 53% performed best on overall questions. Thus the comparison of CRRs before and after training shows an overall improvement from 33 to 53% (p < 0.001), including the three steps of transfusion among other, the interpretation of ABO compatibility clinical cases of which the CRR almost doubled. This finding emphasis the contribution and the efficacy of transfusion education and training already proved by different studies [10, 15–18].

The finding of our study demonstrate that transfusion knowledge of medical and nursing staffing in our hospital is likely to be improved by continuing training and transfusion education programs. This point was shared also by many studies [15–18]. It should therefore be noted that special attention should be given to young physicians and nurses, the most active group in institutions [15–18].

Conclusion

In order to improve the transfusion knowledge of medical and nursing staff in our institution, transfusion education should be started at the university and continued along the professional life. These courses should consist of complete, specific and well-targeted educational programs prepared by experts. In another hand, the evaluation of knowledge should be carried out on a continuous manner in order to detect gaps and orient the trainers through theoretical and practical assessments carried out in the professional sector to ensure the effectiveness of their training [10].

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Authors Contributions

BS and SC wrote the manuscript. SC designed the study. MG performed the research. MR and EAR reviewed the manuscript. SN and MZ supervised results.

BW, LK and SM conducted the statistical analysis. LMA and MH revised critically the intellectual content of the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Highlights

• Rigorous application of the recommendations on good transfusion practice is fundamental to patient safety.

• A good level of expertise is a condition for all types of transfusion activities, in order to ensure the correct use of blood and to prevent transfusion accidents.

• Knowledge must be continually evaluated in order to detect any weaknesses, to guide trainers and to improve the effectiveness of training programs.

References

- 1.Letaief M, Hassine M, Bejia I, Ben Romdhane F, Ben Salem K, Soltani MS (2005) Paramedical staff knowledge and practice related to the blood transfusion safety. Transfus Clin Biol 12:25–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franklin IM (2012) Blood transfusion safety: a new philosophy. Transfuse Med 22(6):377–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Vries RR, Faber JC, Strengers PF (2011) Board of the International Haemovigilance Network. Haemovigilance: an effective tool for improving transfusion practice. Vox Sang 100(1):60–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Biasio L (2016) Blood safety in the OR: The bloody truth. ORNAC J 34(4):17–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasudev R, Sawhney V, Dogra M, Raina TR (2016) Transfusion-related adverse reactions: From institutional hemovigilance effort to National Hemovigilance program. Asian J Transfus Sci 10(1):31–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vossoughi S, Perez G, Whitaker BI, Fung MK, Rajbhandary S, Crews N et al (2019) Safety incident reports associated with blood transfusions. Transfusion 59(9):2827–2832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kracalik I, Mowla S, Basavaraju SV, Sapiano MRP (2021) Transfusion-related adverse reactions: Data from the National Healthcare Safety Network Hemovigilance Module - United States, 2013–2018. Transfusion 61(5):1424–1434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gouëzec H, Bergoin V, Betbèze V, Bourcier V, Damais A, Drouet N et al (2007) Assessment of knowledge in blood transfusion of medical staff in 14 state-run hospitals. Transfus Clin Biol 14(4):407–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Bartolomeo E, Merolle L, Marraccini C, Canovi L, Berni P, Guberti M et al (2019) Patient Blood Management: transfusion appropriateness in the post-operative period. Blood Transfus 17(6):459–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Champion C, Saidenberg E, Lampron J, Pugh D (2017) Blood transfusion knowledge of surgical residents: is an educational intervention effective? Transfusion 57(4):965–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hijji B, Parahoo K, Hussein MM, Barr O (2013) Knowledge of blood transfusion among nurses. J Clin Nurs 22(17–18):2536–2550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hijji B, Parahoo K, Hossain MM, Barr O, Murray S (2010) Nurses’ practice of blood transfusion in the United Arab Emirates: an observational study. J Clin Nurs 19(23–24):3347–3357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arinsburg SA, Skerrett DL, Friedman MT, Cushing MM (2012) A survey to assess transfusion medicine education needs for clinicians. Transfus Med 22(1):44–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salem-Schatz SR, Avorn J, Soumerai SB (1993) Influence of knowledge and attitudes on the quality of physicians’ transfusion practice. Med Care 31(10):868–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gharehbaghian A, JavadzadehShahshahani H, Attar M, RahbariBonab M, Mehran M, TabriziNamini M (2009) Assessment of physicians knowledge in transfusion medicine, Iran, 2007. Transfus Med 19(3):132–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diakité M, Diawara SI, Tchogang NT, Fofana DB, Diakité SA, Doumbia S et al (2012) Knowledge and attitudes of medical personnel in blood transfusion in Bamako. Mali Transfus Clin Biol 19(2):74–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayadi A, Ben Hamed L, Hmida S (2017) Assessment of the theoretical and practical knowledge of health care staff in relation to blood transfusion. Transfus Clin Biol 24(3S):364 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell SA, Strauss RG, Albanese MA, Case DE (1989) A survey to identify deficiencies in transfusion medicine education. Acad Med 64(4):217–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.