Abstract

In recent years, following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a significant increase in cases of SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2) and related deaths worldwide. Despite the pandemic nearing its end due to the introduction of mass-produced vaccines against SARS-CoV-2, early detection and diagnosis of the virus remain crucial in preventing disease progression. This article explores the rapid identification of SARS-CoV-2 by implementing a multimode plasmonic refractive index (MMRI) optical sensor, developed based on the split ring resonator (SRR) design. The Finite Difference Time Domain (FDTD) numerical solution method simulates the sensor. The studied sensor demonstrates three resonance modes within the reflection spectrum ranging from 800 nm to 1400 nm. Its material composition and dimensional parameters are optimized to enhance the sensor’s performance. The research indicates that all three resonance modes exhibit strong performance with high sensitivity and figures of merit. Notably, the first mode achieves an exceptional sensitivity of 557 nm/RIU, while the third mode exhibits a commendable sensitivity of 453 nm/RIU and a Figure of Merit (FOM) of 45 RIU−1. These findings suggest that the developed MMRI optical sensor holds significant potential for the early and accurate detection of SARS-CoV-2, contributing to improved disease management and control efforts.

Keywords: Optical sensor, Sensitivity, SARS-CoV-2, Multimode refractive index (MMRI), Split ring resonator (SRR)

Subject terms: Optics and photonics, Nanoscience and technology, Nanobiotechnology

Introduction

In the early 21st century, the emergence of respiratory infection syndromes became a significant concern. In 2003, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV) emerged, followed by the H1N1 influenza (Vienna flu) in 2009, and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in 2012, all of which were identified as deadly pandemics globally1–3. After these respiratory infection syndromes, the sudden onset of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) began in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, also referred to as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)4,5. This naming choice was made due to its striking similarities to SARS-CoV6. In 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the rapid and exponential spread of SARS-CoV-2 as a pandemic7,8. SARS-CoV is a strain of human coronavirus known to affect the human respiratory system9. This virus is highly contagious and can spread through direct human-to-human contact or indirectly through air or contaminated surfaces10. Covid-19 has caused widespread impact across various countries globally11. As per the most recent WHO report dated January 7, 2024, there have been more than 774 million confirmed cases and over seven million deaths reported worldwide12.

Moreover, it is noteworthy to highlight the emergence of distinct and malignant SARS-CoV-2 variants, including alpha (B.1.1.7), beta (B.1.351), gamma (P.1), delta (B.1.617.2), delta-plus (B.1.617.2.1/ (AY.1)), and omicron (B.1.1.529), each exhibiting unique characteristics. However, there exists a common feature among all these variants13–16. Specifically, they are all composed of a single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA)15. Additionally, their structure encompasses four essential components: spike glycoprotein (S), nucleocapsid protein (N), envelope protein (E), and membrane protein (M)17–19. The spike glycoprotein plays a pivotal role in binding to human receptor cells and facilitating the replication of SARS-CoV-2’s genetic code20. Consequently, the primary focus of clinical research revolves around neutralizing the spike glycoprotein of the virus21. With the commencement of authorized vaccination, the transmission and outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 have been significantly diminished. However, there remains a lingering risk of contracting this virus and experiencing its potentially fatal complications. Throughout the course of this pandemic, numerous approaches have been employed to assess and diagnose SARS-CoV-2, as well as to implement quarantine and treatment measures aimed at impeding its progression. One such method is the utilization of reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), which has been established as a standard technique for the early detection of COVID-19 due to its remarkable sensitivity22–26. Nevertheless, the RT-PCR method does possess certain drawbacks. It necessitates the amplification of RNA, a process that is slow, time-consuming, and costly27,28. Furthermore, there are instances where erroneous results may be obtained29. According to the investigation conducted by Murugan Divagar et al30., out of 167 patients who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 via RT-PCR, 3% were confirmed to be positive through CT scans. Another means of diagnosing SARS-CoV-2 involves the imaging of the lungs in symptomatic individuals using medical technologies based on computed tomography (CT)6. The CT scan of the chest exhibits characteristic features of COVID-19, which can sometimes overlap with similar respiratory syndromes such as SARS-CoV and H1N1 flu. Hence, despite its high sensitivity, the CT method is not recommended31. Another method that can be employed is the utilization of the virus’s optical properties for detection32. This technique is based on the premise that when the virus attaches itself to a human host cell, there is a change in its refractive index and other optical properties. Consequently, this alteration in refractive index leads to a modification in the resonance frequency or wavelength within the reflection spectrum, which can be detected using optical sensors33,34. In light of the rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2, a multitude of optical sensors based on surface plasmon resonance (SPR) have been developed to enable the timely detection of SARS-CoV-235–40. Within the domain of SPR sensors, there exists a pressing demand for the development of economically viable sensors that retain high levels of sensitivity. One effective strategy to lower the costs associated with grating fabrication for phase matching is the use of a one-dimensional grating sourced from a digital video disc (DVD), thus eliminating the necessity for lithography41. Additionally, the introduction of suitable intermediate materials, like SrTiO3, can markedly improve the sensitivity and functionality of standard SPR sensors configured in the Kretschmann arrangement42,43. The SPR technology has proven to be a more time and cost-efficient method for analyzing biological samples compared to the methods mentioned earlier44. Hence, the use of the SPR technique serves as a rapid screening method for numerous blood samples from individuals suspected of SARS-CoV-2 contamination45. In their research, Saadatmand et al46,47. explore the potential of perovskite materials in the development of superstructures, with a particular focus on their stability, flexibility, and refractive index properties. The designs they propose are applicable in the terahertz (THz) spectrum, paving the way for innovations such as polarization-dependent filters, bidirectional optical switches, and wearable photonic devices. Additionally, they introduced an all-dielectric metasurface that utilizes silicon disks to measure refractive index and temperature48. This work provides a vital foundation for various THz applications, including optical modulators, biochemical assays, and optical switches. Moreover, extensive research has recently focused on metal-insulator-metal (MIM) configurations for their application in multifunctional optical filters, capable of operating across various wavelengths, including the visible and near-infrared (NIR) regions. The high sensitivity of these MIM structures has also made them particularly suitable for medical science applications, where they are used to measure biological samples and evaluate different pathogenic agents49–52.

This paper presents a multimode plasmonic refractive index (MMRI) optical sensor based on a split ring resonator (SRR), which overcomes the limitations of previously mentioned methods, including high cost and time-consuming detection processes. The proposed sensor features a simple structure with higher sensitivity compared to earlier surface plasmon resonance (SPR) sensors and exhibits a higher figure of merit (FOM) than traditional SPR structures. By optimizing the material composition and dimensional parameters, our sensor achieves higher sensitivity and FOM. Therefore, the development of this simple, portable, and cost-effective system with rapid detection sensitivity and high FOM is of utmost importance for the timely assessment and diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2. These promising results highlight the MMRI optical sensor’s potential as a powerful tool in the ongoing battle against COVID-19 and similar viral outbreaks, contributing to improved disease management and control efforts.

Structure and method

Materials

The advent of metamaterials has led to the development of Split Ring Resonator (SRR) structures53. These structures, composed of subwavelength metallic components, exhibit an exceptionally robust electromagnetic response. Metamaterials possess extraordinary characteristics, including electrical conductivity and negative magnetic permeability, which make them highly suitable for the design of SRR structures. Among the various metamaterials, gold and silver have been identified as the most significant ones for constructing SRR structures54. In this research endeavor, gold and silver are employed as metamaterials to fabricate a plasmonic multimode refractive index (MMRI) optical sensor based on SRR. The dielectric substrate consists of a layer of SiO2 and GeO2. Furthermore, to enhance the performance of the structure, two different back reflectors are considered, one made of gold and the other made of silver. The optical properties of gold and silver are derived from the data provided by Johnson and Christy55and Palick56, respectively. The refractive coefficients of SiO2 and GeO2are also obtained from57.

Structure design mechanism

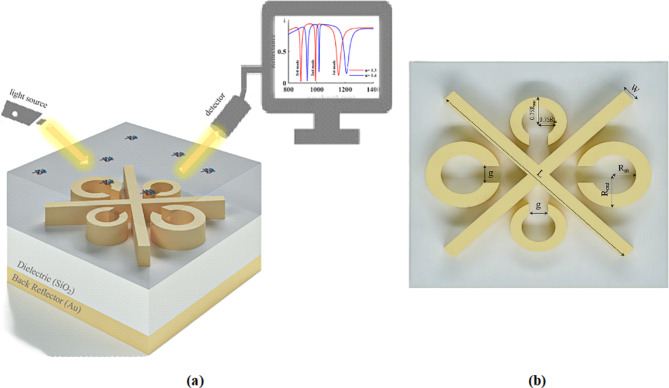

The utilization of Split ring resonator (SRR) technology in optical sensors offers a straightforward structure and convenient design. Furthermore, these sensors exhibit superior performance in comparison to other plasmonic sensors, which has prompted scientists and engineers to conduct further research and analysis on this specific type of sensor. This section aims to provide an explanation of the plasmonic multimode refractive index (MMRI) optical sensor’s structure, which is based on the Split ring resonator (SRR), as well as its dimensional parameters. The design of SRRs typically involves the use of single or multiple metal rings, available in various geometric shapes such as squares or circles, with or without air gaps. Gold is predominantly employed as the material for constructing SRRs. When the rings are surrounded by a time-varying magnetic field, an annular electric current is induced within the metal rings, resulting in the creation of a magnetic dipole moment that is perpendicular to the SRR. The three and two dimentional schematic representation of the designed structure, illustrated in Fig. 1(a) and 1(b), respectivily, exhibits four SRRs and two perpendicular crossed arms positioned at angles of 45 and 135 degrees with respect to the x-axis. This specific arrangement aims to optimize the sensor’s performance. The rings facing each other possess equal sizes, resulting in the outer and inner radii of the two SRRs facing each other being Rout and Rin respectively. Conversely, the other two SRRs have outer and inner radii of 0.75 (Rout) and 0.75 (Rin) respectively. It is worth noting that the width ratio of the mentioned rings can be expressed as Wr1,2=0.75, Wr3,4. All four SRRs incorporate an air gap of length g, while the thickness of SRRs and cross arms is denoted as hr. Furthermore, it is important to highlight the utilization of a dielectric layer as a substrate for the SRRs, which possesses a side length of P and a thickness of hd. Furthermore, to enhance the sensor’s performance parameters, a back reflector layer is incorporated beneath the dielectric layer, with a thickness denoted as hb. Subsequently, the layers responsible for generating the reflection spectrum are scrutinized to determine the optimal resonance. The impact of plasmonic loss and defects arising from manufacturing tolerances on the functionality of plasmonic systems is profound. Metals, as plasmonic materials, are subject to intrinsic energy losses primarily due to ohmic heating. Such energy dissipation limits the strength of local electric fields generated by these materials, which in turn affects their application in biosensing technologies. The degree of loss is contingent upon the selected material. Notably, innovative plasmonic materials like graphene exhibit lower loss characteristics in their responses relative to traditional metals such as gold and silver58. The presence of manufacturing tolerance defects introduces significant challenges, as flaws in the production process can elevate scattering losses and compromise the efficiency of these systems. For example, increased surface roughness on metals can intensify scattering during state transitions, leading to heightened losses. Furthermore, such defects can interfere with the accurate alignment and dimensions of plasmonic structures, resulting in inconsistencies between experimental findings and theoretical models. By meticulously assessing geometric dimensions, choosing appropriate materials, and refining manufacturing processes, it is possible to enhance the efficiency and utility of plasmonic devices, thus unlocking new applications in diverse technological fields59.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the designed sensor (a) 3D and (b) from the top view.

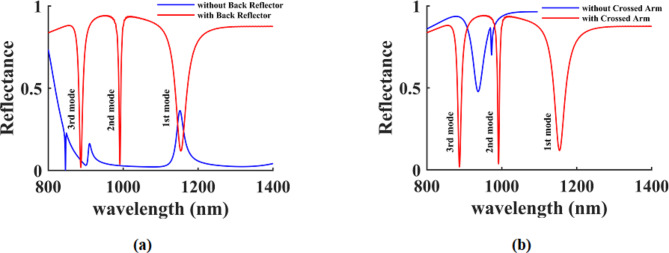

The reflection spectrum of the structure, both with and without the back reflector, is illustrated in Fig. 2(a), while Fig. 2(b) showcases the reflection spectrum with and without the cross arm, as inferred from the aforementioned spectrum. By employing a sensor design that incorporates both the back reflector and cross arm, more favorable results and resonances are achieved within the reflection spectrum. Consequently, the materials utilized and the dimensional parameters of the structure will be analyzed in order to optimize the sensor’s performance. Table 1displays the dimensional characteristics of the structure following the optimization process. The process of implementing SRR configurations, which are versatile systems designed for the detection of diverse medical samples, including viruses, in laboratory settings, begins with their conceptualization and production. To fabricate these structures, a range of nanofabrication techniques, including electron beam nanolithography (EBL), focused ion beam lithography (FBL), and nanoimprint lithography, are utilized60. Additionally, SRR structures are coupled with microfluidic systems to examine the complex permeability characteristics of liquid medical samples. The interaction of various biological samples with the SRR system results in modifications to the optical properties of the sensing environment, leading to a resonance frequency shift that is analyzed through the measurement of these changes61.

Fig. 2.

(a) The reflection spectrum of the proposed sensor without and with back reflector and (b) The reflection spectrum of the proposed sensor without and with cross-arm.

Table 1.

Dimensional parameters of the sensor after optimization.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Dielectric length | P | 680 nm |

| Air gap length | g | 50 nm |

| The outer radius of the ring | Rout | 100 nm |

| The inner radius of the ring | Rin | 60 nm |

| Cross Arm length | L | 676 nm |

| The distance of the ring from the center | Lr | 160 nm |

| Crossed Arm width | W | 40 nm |

| Back Reflector thickness | hb | 60 nm |

| Dielectric thickness | hd | 170 nm |

| Ring thickness | hr | 70 nm |

| Analyte thickness | ha | 200 nm |

Analysis method

The proposed configuration is examined through the implementation of the finite difference time domain (FDTD) numerical solution method, employing the Yee algorithm to solve Maxwell’s governing equations. To accomplish this, the widely recognized and commercially available software, Lumerical FDTD analyzer, is utilized within the realms of optics, photonics, and nanoelectronics. In the FDTD approach, the mesh is defined as auto-non-uniform, and the Conformal0 mode is selected to modify the mesh. The mesh accuracy is established at a value of ‘5’. To ensure a timely convergence of the simulation to the desired response, while maintaining an adequate level of precision, a separate mesh with elements of dx = dy = dz = 10−4 nm is incorporated specifically for the structure-sensitive regions (SRRs). It is noteworthy that the refractive index of the background is equivalent to that of air, which is denoted as 1. Additionally, the simulation time is set to 1000 fS at a temperature of 300k, employing the Field Time monitor. The z-axis direction is equipped with Perfectly matched layer (PML) boundary conditions, and the x and y directions have periodic boundary conditions. Light is emitted from a flat wave source with wavelengths ranging from 800 nm to 1400 nm. The reflection spectrum is analyzed using the Frequency-domain field and power monitor, while the distribution of the electromagnetic field is visualized using the Frequency-domain field profile monitor. To evaluate sensor performance metrics such as sensitivity and FOM, a layer acting as a target analyte can be positioned on the SRR structure. By adjusting the refractive index of the analyte ( ), a shift in the reflection spectrum for the resonance wavelength (

), a shift in the reflection spectrum for the resonance wavelength ( ) is observed. The sensor sensitivity is mathematically defined as Eq. 162.

) is observed. The sensor sensitivity is mathematically defined as Eq. 162.

|

1 |

The FOM is a quantitative indicator utilized to assess and represent the comprehensive performance of an optical sensor. This metric often consolidates various performance parameters, such as sensitivity and response time, into a single value, which aids in the comparative analysis of sensors or other technological designs. The sensor’s FOM can be mathematically represented using the Eq. 263.

|

2 |

Where FWHM represents the full width at half maximum. Within optical sensor technology, the FWHM is a critical parameter that characterizes the quality of resonances in the reflection spectrum. This metric provides valuable information regarding the sensor’s overall quality and sensitivity. A narrower FWHM is considered advantageous, as it signifies enhanced resolution in the resonance detection of biological samples. In addition, the least quantitative value that the sensor is capable of detecting is known as the Limit of Detection (LoD), and it is defined as Eq. 364.

|

3 |

Results and discussion

Structure optimization

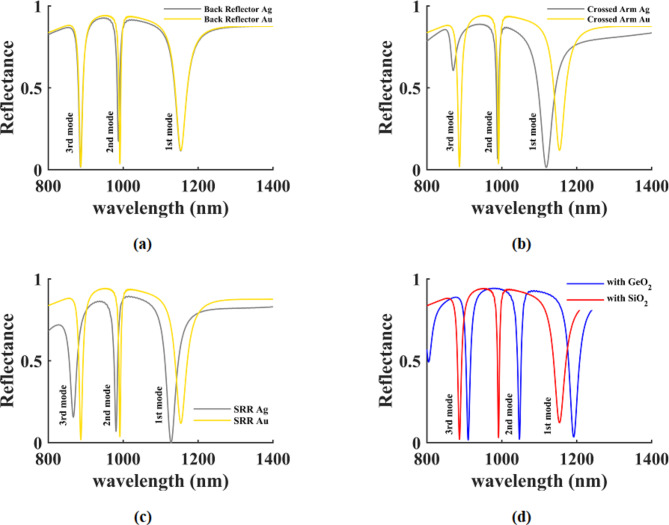

The performance parameters of the sensor were analyzed in this section to optimize its functionality. The examination focused on the material composition and dimensional characteristics of each layer in the three resonance modes. Metamaterials based on gold and silver were employed for the back reflector, crossed arm, and SRRs. The reflection spectrum for each material is depicted in Fig. 3 (a)-(c), revealing that gold exhibits more favorable resonance structures for all three components. Furthermore, Fig. 3 (d) displays the reflection spectrum of the structure with dielectrics composed of SiO2 and GeO2, demonstrating that SiO2 yields superior resonances. The investigations conducted encompass all three resonance modes.

Fig. 3.

Structure reflection spectrum for, (a) gold and silver metals for back reflector, (b) gold and silver metals for cross arm, (c) gold and silver metals for SRRs, and (d) dielectric substrate made of SiO2 and GeO2.

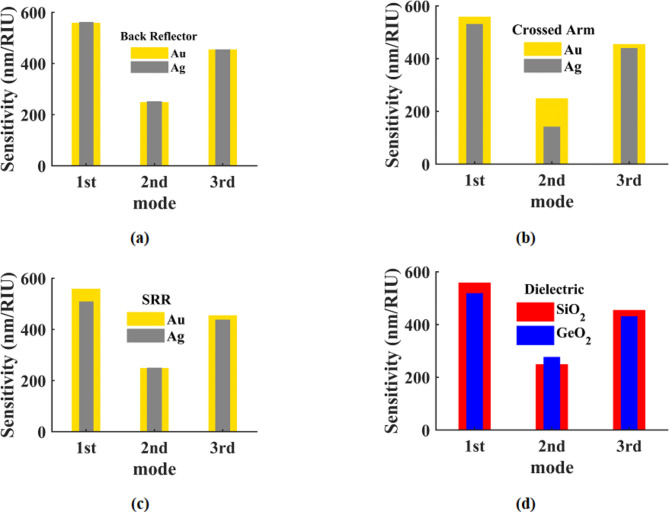

The present study investigates the sensitivity and FOM of the proposed sensor by utilizing gold and silver metals as back reflectors, crossed arms, and split ring resonators (SRRs). The sensitivity and FOM as the outcomes of these investigations are illustrated in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively. Sensor sensitivity in three resonance modes for gold and silver metals are depicted in Fig. 4 (a)-(d) for the back reflector, cross arm, SRRs, and dielectric materials SiO2 and GeO2, respectively. Also, their FOMs are depicted in Fig. 5 (a)-(d) for the back reflector, cross arm, SRRs, and dielectric materials SiO2 and GeO2, respectively. The results obtained reveal that gold provides more optimal values for the mentioned components, while SiO2 demonstrates superior performance as a dielectric material for sensitivity and FOM across all three resonance modes. The ferromagnetic properties of gold render it a more suitable metal for this structure compared to silver. Additionally, the dielectric coefficient of SiO2 surpasses that of GeO2, making SiO2 the preferred choice for the back reflector, crossed arm, and SRRs, as well as the dielectric substrate. We also explored the impact of varying the geometric parameters of the SRRs on the sensor’s performance. By adjusting the dimensions of the SRRs, including the arm length, gap width, and ring diameter, we observed significant changes in both sensitivity and FOM.

Fig. 4.

Sensor sensitivity in three resonance modes for, (a) gold and silver metals back reflector, (b) gold and silver metals cross arm, (c) gold and silver metals SRRs and (d) dielectric substrate made of SiO2 and GeO2.

Fig. 5.

FOM of the sensor in three resonance modes, (a) for gold and silver metals back reflector, (b) for gold and silver metals cross arm, (c) for gold and silver metals SRRs, and (d) dielectric substrate made of SiO2 and GeO2.

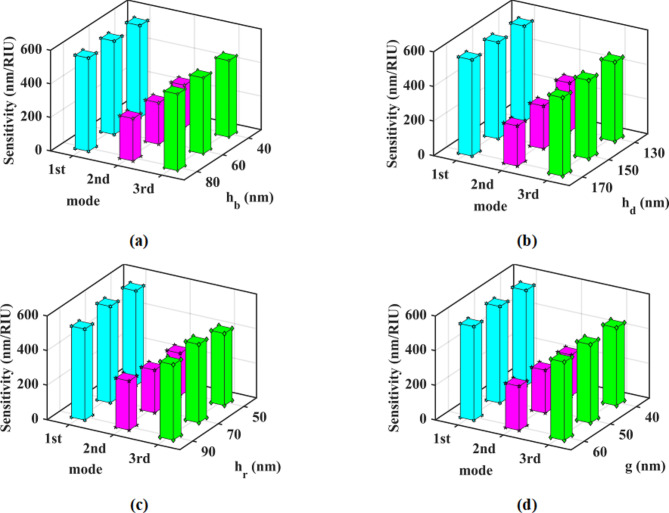

The subsequent step involves the evaluation of dimensional parameters to attain the optimal state of performance parameters across all resonance modes of the sensor. The sensitivity of the sensor was analyzed for different values of hb, hd, hr, and g. The outcomes of the tests conducted for these parameters are depicted in Fig. 6 (a)-(d), revealing that modifications in these parameters do not significantly impact the sensor’s sensitivity in all three resonance modes. Subsequently, the FOM of the structure is assessed using the same values for hb, hd, hr, and g. Figure 7 (a) illustrates that the FOM initially increases and then decreases with an increase in hb. Moreover, irregular fluctuations in FOM are observed with an increase in hd (Fig. 7(b)). The FOM increases with an increase in hr for the first and third modes, while in the second mode, it initially rises and then declines (Fig. 7(c)). The alteration in g has minimal influence on the change in FOM (Fig. 7(d)).

Fig. 6.

The sensitivity of the proposed sensor in three resonance modes, (a) versus dimensional parameter changes hb, (b) versus dimensional parameter changes hd, (c) versus dimensional parameter changes hr, and (d) versus dimensional parameter changes g.

Fig. 7.

FOM of the sensor in three resonance modes, (a) versus dimensional parameter changes hb, (b) versus dimensional parameter changes hd, (c) versus dimensional parameter changes hr, and (d) versus dimensional parameter changes g.

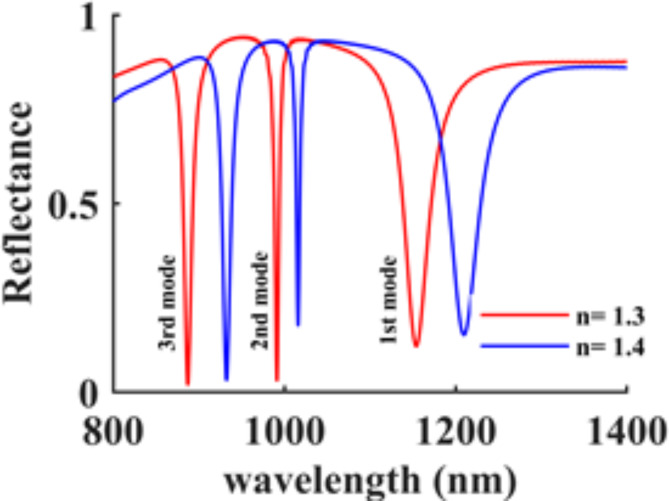

Following the optimization of the structure’s dimensions, a reanalysis of its reflection spectrum is conducted. Figure 8 depicts the reflection spectrum at two different refractive indices for n = 1.3 and n = 1.4. The sensor’s sensitivity was evaluated across all three resonance modes using Eq. 1. The maximum sensitivity of 557 nm/RIU was observed in the first mode. Additionally, the FoM was determined for all modes using Eq. 2, resulting in a remarkable value of 45.3 1/RIU in the third mode. The third mode also exhibited a relatively good sensitivity of 453 nm/RIU.

Fig. 8.

Reflectance spectrum of the designed structure in three resonance modes for n = 1.3 and n = 1.4.

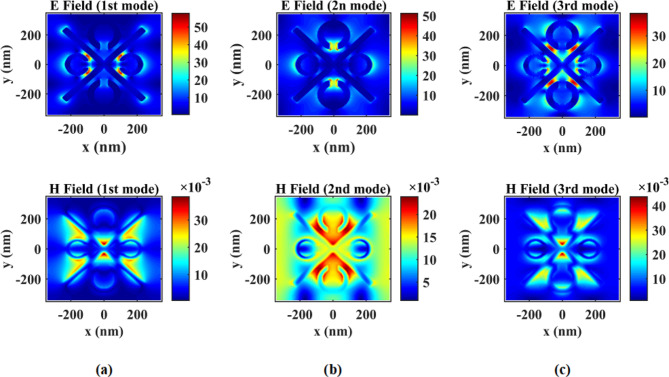

The analysis of the electromagnetic response of the proposed sensor encompasses an examination of all resonant modes when observed from the top view. In the first mode, the distribution of electric and magnetic fields can be observed between the cross arm and two smaller SRRs. Conversely, in the second mode, the electric and magnetic fields are distributed within the gaps of two larger SRRs. Notably, in the second mode, the magnetic field extends slightly further and occupies the space between the walls of the cross arm. Finally, in the third mode, the electric and magnetic fields spread between the cross arm and the two larger SRRs, as well as near the gap of the two smaller SRRs. These findings are visually presented in Fig. 9 (a)-(c). The increased field strength is a result of resonance and field localization, and not a creation of additional energy. These phenomena occur naturally in nanostructures with plasmonic or resonant behavior and are fully consistent with the conservation of energy principles.

Fig. 9.

(a) Distribution of electric and magnetic fields from the top view in the first mode, (b) Distribution of electric and magnetic fields from the top view in the second mode, and (c) Distribution of electric and magnetic fields from the top view in the third mode.

In this section, a detailed analysis of the structural response to beams with limited width is conducted, focusing on the sensor’s performance as a function of the radiation angle. The results demonstrate that both the sensitivity and the FOM of the sensor exhibit relatively consistent behavior across all resonant modes, even as the radiation angle increases. Reflectance spectrum of the structure for different radiation angle are depicted in Fig. 10 (a) and 10 (b) for n = 1.3 and n = 1.4, respectively. However, as shown in these figures, there is a significant change in the shape of the reflection spectrum with increasing radiation angle. Additionally, Fig. 11 highlights the influence of substrate and metaatom losses on the transition curve of the structure. In Fig. 11a, it is observed that the light transmittance peaks remain stable despite variations in the thickness of the quartz substrate. As shown in Fig. 11(b), an increase in the thickness of the gold substrate, used as a back reflector, results in a noticeable attenuation of the light transmittance curve. This behavior suggests that as the thickness of the individual sub-layers increases, the associated losses become more pronounced, leading to an expected degradation in transmittance.

Fig. 10.

Reflectance spectrum of the structure, (a) for different angles of radiation per n = 1.3 and (b) for different angles of radiation per n = 1.4.

Fig. 11.

The impact of losses in both the sublayer and the meta-atoms on the transmittance curve of the sensor, (a) effect of dielectric substrate and (b) effect of a back reflector.

Utilizing the sensor for the measurement of SARS-CoV-2

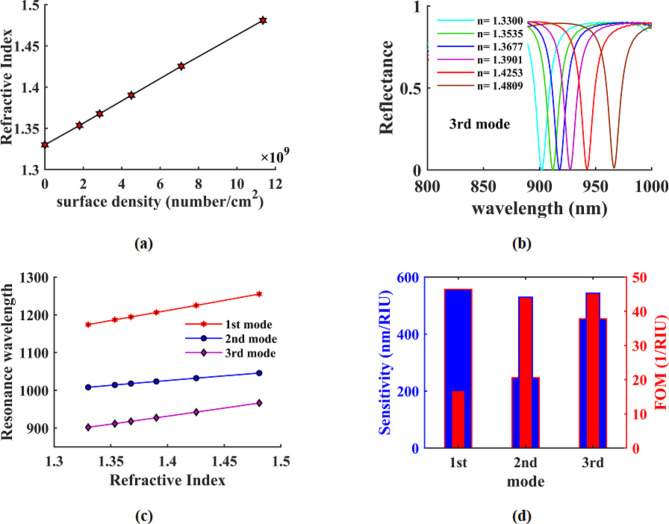

The sensor for corona detection in the terminal layer after SRR was modeled by attaching DNA to thiol65. The SARS-CoV-2 virus can be characterized as a solid sphere core containing RNA, with a radius denoted as r1, surrounded by a protein membrane with a radius denoted as r266. As a result, the effective refractive indices of the virus are computed by summing the weight and volume according to the given in Eq. 467.

|

4 |

where n1V1 and n2V2 respectively represent the refractive index of total RNA and membrane protein with its corresponding volume.

Typically, the refractive index is more influenced by the composition of a material rather than its geometric size. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, the refractive index (denoted as η) remains constant at a value of 1.2566. Additionally, the average refractive index of RNA is measured to be 1.5468. The refractive index of membrane protein exhibits slight variations within the range of 1.46 ± 0.00669. As for the viral load, it is quantified as an average of 7 × 106 per mL, with the highest recorded value reaching 2.35 × 109per mL70. When the sample is applied to the assay area, the COVID-19 RNA binds to the thiol-linked DNA, resulting in a gradual accumulation of the virus on the surface. This process takes a short amount of time, adhering to the standard expected time. Consequently, the effective refractive index of the virus is graphed against the surface density in Fig. 12(a). Thus, employing the suggested optical sensor and its modeling technique for the virus’s refractive index, the prompt detection of SARS-CoV-2 can be accomplished with utmost efficiency. The reflection spectrum of the sensor, as depicted in Fig. 12(b), showcases distinct variations corresponding to different values of the modeled effective refractive index. Figure 12(c) presents the resonance wavelength for all three resonance modes of the sensor against the mentioned refractive index. Additionally, Fig. 12(d) provides a comprehensive comparison of sensitivity and FOM among the three resonance modes. The proposed optical sensor, characterized by its straightforward and cost-effective structural design, exhibits remarkable sensitivity and FOM. Its ability to rapidly detect SARS-CoV-2 holds the promise of advancing scientific and technological advancements, thereby offering valuable support to the medical community and treatment personnel during critical periods.

Fig. 12.

(a) effective refractive index of the virus against the surface density, (b) the reflection spectrum of the sensor in the third mode as a function of the refractive index of the virus, (c) Resonance wavelength in three resonance modes as a function of the refractive index of the virus and (d) Sensitivity and FOM structure in all three modes for SARS-CoV-2 detection.

Table 2 presents a comparative analysis of the performance parameters—sensitivity, FWHM, and FOM—of three resonance modes of the proposed structure in comparison to previously reported works. The sensitivity measures the response to changes in the refractive index, where the proposed first mode exhibits the highest sensitivity of 557 nm/RIU. The FWHM, indicating the sharpness of the resonance peak, is notably low for the second mode at 5.6 nm, suggesting a very sharp peak. The FOM, which combines both sensitivity and sharpness, highlights the performances of each resonance mode. Here, the third mode of the proposed structure achieves the highest FOM of 45.3, demonstrating superior performance in balancing sensitivity and peak sharpness. Geometry optimization, using materials with superior plasmonic properties, advanced nanofabrication techniques, and other enhancements can further improve the confinement of electromagnetic fields. These improvements can lead to sharper resonance peaks, enhanced sensitivity, and an increased FOM for the biosensor. Overall, the proposed structure shows significant enhancements in resonance performance, marking a substantial improvement over the existing technologies referenced.

Table 2.

Comparison of performance parameters of three resonance modes of the proposed structure with previously reported works.

| References | Sensitivity | FWHM | FOM (1/RIU) | LoD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 38 | 293 deg/RIU | 5.5 deg | 22 | --- |

| 71 | 75 deg/RIU | 17 deg | 44.2 | --- |

| 72 | 66 nm/RIU | 0.9 nm | 7.7 | --- |

| 73 | 225 nm/RIU | --- | --- | --- |

| 74 | 300 nm/RIU | --- | --- | --- |

| 75 | 313 nm/RIU | 39.1 nm | 4 | --- |

| 64 | 153.85 GHz/RIU | 38.6 GHz | 3.98 | 0.025 |

| 76 | 570.4 nm/RIU | 139.22 nm | 4.1 | --- |

| 77 | 500 GHz/RIU | 47 GHz | 10.638 | --- |

| 78 | 274.37 deg/RIU | 6.76 deg | 40.6 | --- |

| 79 | 403 nm/RIU | --- | --- | --- |

| This work (1st mode) | 557 nm/RIU | 33.2 nm | 16.8 | 0.035 |

| This work (2nd mode) | 247 nm/RIU | 5.6 nm | 44.1 | 0.01 |

| This work (3rd mode) | 453 nm/RIU | 10 nm | 45.3 | 0.01 |

Conclusion

In this study, an investigation was conducted on a plasmonic multi-mode refractive index (MMRI) optical sensor utilizing a Split ring resonator (SRR) to detect the COVID-19 virus. The simulation of this structure was carried out using the finite difference time domain (FDTD) numerical solution method. To enhance the performance of the proposed sensor, various materials were employed and the dimensional parameters were thoroughly examined. The results obtained indicate that the designed sensor exhibits three resonance modes within the reflection spectrum ranging from 800 nm to 1400 nm. All three modes demonstrate higher sensitivity and FOM. The first mode exhibits the highest reported sensitivity of 557 nm/RIU, while the third mode achieves the highest figure of merit (FOM) of 45.3 1/RIU. Moreover, the third mode demonstrates a favorable sensitivity of 453 nm/RIU. In recent years, the significance of analyzing SARS-CoV-2 has significantly increased due to its exponential prevalence and global fatality rates. Although it can be argued that the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic is nearing its conclusion, it remains crucial to promptly detect this disease to impede its progression. This is particularly important as it can often be mistaken for other seasonal infectious diseases such as the common cold or influenza. Therefore, the objective of this research is to design and simulate a plasmonic multi-mode refractive index (MMRI) optical sensor that enables swift detection of the COVID-19 virus. The ultimate goal of this study is to provide substantial assistance to the medical community and healthcare personnel.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wrapp, D. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 367 (6483), 1260–1263 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsieh, C. L. et al. Structure-based design of prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 spikes. Science. 369 (6510), 1501–1505 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss, C. et al. Toward nanotechnology-enabled approaches against the COVID-19 pandemic. ACS nano. 14 (6), 6383–6406 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chamola, V. et al. A comprehensive review of the COVID-19 pandemic and the role of IoT, drones, AI, blockchain, and 5G in managing its impact. Ieee Access.8, 90225–90265 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bajaj, A. et al. Synthesis of molecularly imprinted polymer nanoparticles for SARS-CoV-2 virus detection using surface plasmon resonance. Chemosensors. 10 (11), 459 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kabir, M. A. et al. Diagnosis for COVID-19: current status and future prospects. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 21 (3), 269–288 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Douedi, S. & Miskoff, J. Novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19): a case report and review of treatments. Medicine. 99 (19), e20207 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maleki, M., Norouzi, Z. & Maleki, A. COVID-19 Infection: A Novel Fatal Pandemic of the World in 2020, in Practical Cardiologyp. 731–735 (Elsevier, 2022).

- 9.Alhalaili, B. et al. Nanobiosensors for the detection of novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV and other pandemic/epidemic respiratory viruses: a review. Sensors. 20 (22), 6591 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lotfi, M., Hamblin, M. R. & Rezaei, N. COVID-19: transmission, prevention, and potential therapeutic opportunities. Clin. Chim. Acta. 508, 254–266 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weckbach, L. T. et al. [COVID-19: a cardiological point-of-view]. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 145 (15), 1063–1067 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization (WHO): Novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland (2024).

- 13.Yang, M. et al. Focus on characteristics of COVID-19 with the Special reference to the impact of COVID-19 on the Urogenital System. Curr. Urol. 14 (2), 79–84 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexandar, S. et al. A comprehensive review on Covid-19 Delta variant. Int. J. Pharmacol. Clin. Res. (IJPCR). 5 (83–85), 7 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Astuti, I. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): An Overview of Viral Structure and host Response14p. 407–412 (Clinical Research & Reviews, 2020). 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Hassanpour, S. H. & Nikbakht, J. A comprehensive review on covid-19. Zahedan J. Res. Med. Sci., 23(4). (2021).

- 17.Feng, W. et al. Molecular diagnosis of COVID-19: challenges and research needs. Anal. Chem. 92 (15), 10196–10209 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taha, B. A. et al. An analysis review of detection coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) based on biosensor application. Sensors. 20 (23), 6764 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mousavizadeh, L. & Ghasemi, S. Genotype and phenotype of COVID-19: their roles in pathogenesis. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 54 (2), 159–163 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mostufa, S. et al. Numerical approach to design the graphene-based multilayered surface plasmon resonance biosensor for the rapid detection of the novel coronavirus. Opt. Continuum. 1 (3), 494–515 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akib, T. B. A. et al. A performance comparison of heterostructure surface plasmon resonance biosensor for the diagnosis of novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Opt. Quant. Electron. 55 (5), 448 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corman, V. M. et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Eurosurveillance. 25 (3), 2000045 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaibun, T. et al. Rapid electrochemical detection of coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Commun. 12 (1), 802 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fabiani, L. et al. Magnetic beads combined with carbon black-based screen-printed electrodes for COVID-19: a reliable and miniaturized electrochemical immunosensor for SARS-CoV-2 detection in saliva. Biosens. Bioelectron. 171, 112686 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo, K. et al. Rapid single-molecule detection of COVID-19 and MERS antigens via nanobody-functionalized organic electrochemical transistors. Nat. Biomedical Eng. 5 (7), 666–677 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yousefi, H. et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 viral particles using direct, reagent-free electrochemical sensing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (4), 1722–1727 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corman, V. et al. Assays for laboratory confirmation of novel human coronavirus (hCoV-EMC) infections. Eurosurveillance. 17 (49), 20334 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mukherjee, R. Global efforts on vaccines for COVID-19: since, sooner or later, we all will catch the coronavirus. J. Biosci. 45 (1), 68 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qiu, G. et al. Dual-functional plasmonic photothermal biosensors for highly accurate severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 detection. ACS nano. 14 (5), 5268–5277 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murugan, D. et al. P-FAB: a fiber-optic biosensor device for rapid detection of COVID-19. Trans. Indian Natl. Acad. Eng. 5, 211–215 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pokhrel, P., Hu, C. & Mao, H. Detecting the coronavirus (COVID-19). ACS Sens. 5 (8), 2283–2296 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luan, E. et al. Silicon photonic biosensors using label-free detection. Sensors. 18 (10), 3519 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nisha, A. et al. Sensitivity enhancement of surface plasmon resonance sensor with 2D material covered noble and magnetic material (ni). Opt. Quant. Electron. 51, 1–12 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dey, B., Islam, M. S. & Park, J. Numerical design of high-performance WS2/metal/WS2/graphene heterostructure based surface plasmon resonance refractive index sensor. Results Phys. 23, 104021 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pandey, P. S. et al. SPR based biosensing chip for COVID-19 diagnosis—A review. IEEE Sens. J. 22 (14), 13800–13810 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trzaskowski, M. et al. Portable surface plasmon resonance detector for COVID-19 infection. Sensors. 23 (8), 3946 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yano, T. et al. Ultrasensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein using large gold nanoparticle-enhanced surface plasmon resonance. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 1060 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taya, S. A. et al. Detection of virus SARS-CoV-2 using a surface plasmon resonance device based on BiFeO3-graphene layers. Plasmonics. 18 (4), 1441–1448 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar, A., Kumar, A. & Srivastava, S. Silicon nitride-BP-based surface plasmon resonance highly sensitive biosensor for virus SARS-CoV-2 detection. Plasmonics. 17 (3), 1065–1077 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Srivastava, S. et al. Numerical study of titanium dioxide and MXene nanomaterial-based surface plasmon resonance biosensor for virus SARS-CoV-2 detection. Plasmonics. 18 (4), 1477–1488 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saadatmand, S. B. et al. Metastructure Engineering with Ruddlesden–Popper 2D Perovskites: Stability, Flexibility, and Quality Factor Trade-Offs (ACS omega, 2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Saadatmand, S. B., Ahmadi, V. & Hamidi, S. M. Quasi-BIC based all-dielectric metasurfaces for ultra-sensitive refractive index and temperature sensing. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 20625 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saadatmand, S. B. et al. Design and analysis of a flexible ruddlesden–Popper 2D perovskite metastructure based on symmetry-protected THz-bound states in the continuum. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 22411 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin, M. et al. Multi-channel prismatic localized surface plasmon resonance biosensor for real-time competitive assay multiple COVID-19 characteristic miRNAs. Talanta. 275, 126142 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Uniyal, A. et al. Fluorinated graphene and CNT-based surface plasmon resonance sensor for detecting the viral particles of SARS-CoV-2. Phys. B: Condens. Matter. 669, 415282 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saadatmand, S. B. et al. Graphene-based integrated plasmonic sensor with application in biomolecule detection. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B. 40 (1), 1–10 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saadatmand, S. B. et al. Design and analysis of highly sensitive Plasmonic Sensor based on 2-D Inorganic Ti-MXene and SrTiO 3 Interlayer. IEEE Sens. J. 23 (12), 12727–12735 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chemerkouh, M. J. H. N., Saadatmand, S. B. & Hamidi, S. M. Ultra-high-sensitive biosensor based on SrTiO 3 and two-dimensional materials: Ellipsometric concepts. Opt. Mater. Express. 12 (7), 2609–2622 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ebadi, S. M. et al. A multipurpose and highly-compact plasmonic filter based on metal-insulator-metal waveguides. IEEE Photonics J. 12 (3), 1–9 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lai, W. et al. Plasmonic filter and sensor based on a subwavelength end-coupled hexagonal resonator. Appl. Opt. 57 (22), 6369–6374 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zegaar, I. & Hocini, A. Modeling and analysis of the RI sensitivity of plasmonic sensor based on MIM waveguide-coupled structure. in Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing. (2021).

- 52.Mao, J. et al. Numerical analysis of near-infrared plasmonic filter with high figure of merit based on Fano resonance. Appl. Phys. Express. 10 (8), 082201 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pendry, J. B. et al. Magnetism from conductors and enhanced nonlinear phenomena. IEEE Trans. Microwave Theory Tech. 47 (11), 2075–2084 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang, Z. et al. Mechanism of the metallic metamaterials coupled to the gain material. Opt. Express. 22 (23), 28596–28605 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson, P. B. & Christy, R. W. Optical constants of the noble metals. Phys. Rev. B. 6 (12), 4370 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Palik, E. D. Handbook of Optical Constants of SolidsVol. 3 (Academic, 1998).

- 57.https://refractiveindex.info/.

- 58.Cherqui, C. et al. Plasmonic Surface Lattice resonances: theory and computation. Acc. Chem. Res. 52 (9), 2548–2558 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang, J. et al. Plasmonic metasurfaces with 42.3% transmission efficiency in the visible. Light Sci. Appl. 8, 53 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kannegulla, A. & Cheng, L. J. Metal assisted focused-ion beam nanopatterning. Nanotechnology. 27 (36), 36lt01 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ma, L. et al. Thermally tunable high-Q metamaterial and sensing application based on liquid metals. Opt. Express. 29 (4), 6069–6079 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tang, Y., Zeng, X. & Liang, J. Surface plasmon resonance: an introduction to a surface spectroscopy technique. J. Chem. Educ. 87 (7), 742–746 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mostufa, S., Paul, A. K. & Chakrabarti, K. Detection of hemoglobin in blood and urine glucose level samples using a graphene-coated SPR based biosensor. OSA Continuum. 4 (8), 2164–2176 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alsalman, O. et al. Design of split ring resonator graphene metasurface sensor for efficient detection of brain tumor. Plasmonics. 19 (1), 523–532 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peterlinz, K. A. et al. Observation of hybridization and dehybridization of thiol-tethered DNA using two-color surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119 (14), 3401–3402 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Asghari, A. et al. Fast, accurate, point-of-care COVID-19 pandemic diagnosis enabled through advanced lab-on-chip optical biosensors: opportunities and challenges. Appl. Phys. Reviews, 8(3). (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Uddin, S. M. A., Chowdhury, S. S. & Kabir, E. Numerical analysis of a highly sensitive surface plasmon resonance sensor for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Plasmonics. 16 (6), 2025–2037 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang, Q. et al. Quantitative refractive index distribution of single cell by combining phase-shifting interferometry and AFM imaging. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 2532 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Van Manen, H. J. et al. Refractive index sensing of green fluorescent proteins in living cells using fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy. Biophys. J. 94 (8), L67–L69 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wölfel, R. et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 581 (7809), 465–469 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chowdhury, S. S., Uddin, S. M. A. & Kabir, E. Numerical analysis of sensitivity enhancement of surface plasmon resonance biosensors using a mirrored bilayer structure. Photonics Nanostructures-Fundamentals Appl. 41, 100815 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chorsi, H. T., Zhu, Y. & Zhang, J. X. Patterned plasmonic surfaces—theory, fabrication, and applications in biosensing. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 26 (4), 718–739 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vafapour, Z. Polarization-independent perfect optical metamaterial absorber as a glucose sensor in food industry applications. IEEE Trans. Nanobiosci. 18 (4), 622–627 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vafapour, Z. et al. The potential of refractive index nanobiosensing using a multi-band optically tuned perfect light metamaterial absorber. IEEE Sens. J. 21 (12), 13786–13793 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Taghipour, A. & Heidarzadeh, H. Design and analysis of highly sensitive LSPR-based metal–insulator–metal nano-discs as a biosensor for fast detection of SARS-CoV-2. in Photonics. MDPI. (2022).

- 76.Khodaie, A. & Heidarzadeh, H. Design and analysis of a multi-modal refractive index plasmonic biosensor based on split ring resonator for detection of the various cancer cells. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56 (9), 1439 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wekalao, J. et al. Optical-Based Aqueous Solution Detection by Graphene Metasurface Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor with Behavior Prediction Using Polynomial Regression. Plasmonics, : pp. 1–22. (2024).

- 78.Pandiaraj, S. et al. Ultra-sensitive and selective surface Plasmon Resonance using Ag Metal, Carbon Nanotube, and Selenium Based biosensors for the detection of ascorbic acid. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 13 (8), 087002 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shi, B. et al. Compact slot microring resonator for sensitive and label-free optical sensing. Sensors. 22 (17), 6467 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.