Abstract

Post-COVID-19 syndrome (PCS) is an emerging health problem in people recovering from COVID-19 infection within the past 3–6 months. The current study aimed to define the predictive factors of PCS development by assessing the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) levels in blood leukocytes, inflammatory markers and HbA1c in type 2 diabetes patients (T2D) with regard to clinical phenotype, gender, and biological age. In this case-control study, 65 T2D patients were selected. Patients were divided into 2 groups depending on PCS presence: the PCS group (n = 44) and patients who did not develop PCS (n = 21) for up to 6 months after COVID-19 infection. HbA1c and mtDNA levels were the primary factors linked to PCS in different models. We observed significantly lower mtDNA content in T2D patients with PCS compared to those without PCS (1.26 ± 0.25 vs. 1.44 ± 0.24; p = 0.011). In gender-specific and age-related analyses, the mt-DNA amount did not differ significantly between the subgroups. According to the stepwise multivariate logistic regression analysis, low mtDNA content and HbA1c were independent variables associated with PCS development, regardless of oxygen, glucocorticoid therapy and COVID-19 severity. The top-performing model for PCS prediction was the gradient boosting machine (GBM). HbA1c and mtDNA had a notably greater influence than the other variables, indicating their potential as prognostic biomarkers.

Subject terms: Endocrinology, Endocrine system and metabolic diseases, Predictive markers

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has seriously impacted the health and prognosis of patients with metabolic disorders1. Although the COVID-19 pandemic has mostly subsided, there are emerging threats of infectious diseases in the near future, that define the need for primary and secondary preventive measures2. Studying the effects of COVID-19 in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) requires an explanation of the changes associated with metabolic dysfunction and many complications3. Post-COVID-19 syndrome (PCS; long COVID-19, post-acute COVID-19, long-term effects of COVID-19) is an emerging health problem in people recovering from COVID-19 infection within the past 3–6 months. It is characterized by symptoms such as fatigue, muscle pain, cough, drowsiness, and headaches4. The regulation of vital cellular processes, including basic energy metabolism and mitochondrial function, is vulnerable in the PCS at the genomic level5. The study of COVID-19 severity markers and the assessment of PCS prognosis have encouraged the discovery of the molecular mechanisms responsible for PCS and inevitable pathological conditions.

Mitochondria are involved in oxidative phosphorylation and redox homeostasis. They can be in a “cell-free” state and reside in extracellular vesicles, and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) circulates in the extracellular space6. Mitochondria have already been shown to be involved in the replication of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, affecting their membrane integrity and resulting in activation of the proinflammatory signals7. On the other hand, SARS-CoV-2 can affect mitochondrial function, facilitating the progression of pathological conditions6. Evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 infection is closely associated with endothelial dysfunction and microthrombosis caused by pulmonary coagulopathy, inflammation, oxidative stress, hypoxia, changes in mitochondrial function, and DNA damage8. In addition, platelet damage and cell apoptosis due to many processes can be associated with mitochondrial dysfunction9. Previous studies have demonstrated the role of the inflammatory response, the NLRP3 inflammasome, which increases its expression due to mitochondrial dysfunction, enhanced production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mtROS) and circulating free mtDNA (cf-mtDNA). These changes lead to an excessive macrophage response, especially in elderly individuals5, provoking a cascade of inflammation-driven events and severe tissue damage. In addition to this systemic effect, mitochondria damage and cf-mtDNA release was shown to be prognostic for COVID-19 severity prediction10.

When studying biological material from the respiratory tract and blood of patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, significantly reduced expression of the mtDNA genes was found in the blood but not in respiratory tract samples. Increased glycolysis and the expression of ROS response genes and glycolytic enzymes are associated with enhanced replication of SARS-CoV-211. In addition, the structural proteins NSP4 and ORF9b of the SARS-CoV-2 virus are involved in mitochondrial damage, leading to cell apoptosis. These events are accompanied by the formation of outer membrane macropores and the release of inner membrane vesicles containing mtDNA12.

In clinical settings, a recent study suggested that elevated cf-mtDNA may be used as a possible marker of COVID-19 severity and is associated with poor prognosis, adverse outcomes (hospital admission, admission to the intensive care unit, respiratory support), and mortality10,13–15. However, only few studies discovered the role of mtDNA levels in blood cells, demonstrating the relationship between mtDNA and fatigue or mental disorders in patients after COVID-1916,17. Thus, the prognostic factors of PCS and predictive role of mtDNA are still uncovered.

In this study, we aimed to define the predictive factors for early detection of PCS by assessing the mtDNA levels in blood leukocytes, inflammatory markers and HbA1c in T2D with regard to clinical phenotype, gender, and biological age. The ability of mtDNA to serve as a prognostic biomarker of PCS development was also tested.

Results

Characteristics of the study participants

The study involved 65 patients with T2D who had a history of COVID-19. According to the outcome, the patients were subdivided into two groups: those who did not have PCS (comparison group, n = 21) and those assigned to group 1, the patients with PCS (main group/group 2, n = 44).

The main basic characteristics of the groups are presented in Table 1. The average ages of the patients were comparable − 62.09 ± 9.69 and 61.86 ± 11.32 years in groups 1 and 2, respectively (p = 0.962). All patients had T2D for approximately 10 years (group 1–10.66 ± 8.26 years; group 2–9.72 ± 7.19 years; p = 0.641). There were no statistically significant differences in the BMI of PCS patients (30.77 ± 5.89 kg/m2) compared to the comparison group (29.57 ± 4.71 kg/m2; p = 0.417). However, HbA1c levels were significantly greater in group 2 (8.70 ± 1.52%) than in group 1 (7.86 ± 1.28%; p = 0.033). These data indicate an association between T2D glycemic control and the PCS. Additionally, a greater number of cardiorenal disorders were observed in the PCS group, resulting in more frequent prescriptions of iSGLT-2 to patients with PCS − 15.9%, which was three times more often than in patients from the comparison group prescribed this antidiabetic drug (ADD) in only 4.8% of cases, though these differences were insignificant (p = 0.201).

Table 1.

The general participant characteristics.

| Parameter | PCS absent (n = 21) |

PCS present (n = 44) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 62.00 ± 9.69 | 61.86 ± 11.32 | 0.962 |

| T2D duration, years | 10.66 ± 8.26 | 9.72 ± 7.19 | 0.641 |

| Weight, kg | 86.14 ± 12.24 | 88.84 ± 16.32 | 0.504 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.57 ± 4.71 | 30.77 ± 5.89 | 0.417 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 97.47 ± 12.41 | 99.93 ± 12.98 | 0.472 |

| Metformin, % (n) | 81.0 (17) | 70.5 (31) | 0.368 |

| SUs, % (n) | 28.6 (6) | 31.8 (14) | 0.791 |

| DPP-4 inhibitors, % (n) | 4.8 (1) | 2.3 (1) | 0.587 |

| GLP-1 agonists, % (n) | 4.8 (1) | 2.3 (1) | 0.587 |

| SGLT-2 antagonists, % (n) | 4.8 (1) | 15.9 (7) | 0.201 |

| Insulin human, % (n) | 9.5 (2) | 11.4 (5) | 0.823 |

| Insulin analogs, % (n) | 28.6 (6) | 20.5 (9) | 0.468 |

| Diet only, % (n) | 4.8 (1) | 6.8 (3) | 0.543 |

| Diabetic nephropathy, % (n) | 9.5 (2) | 25.0 (11) | 0.145 |

| Diabetic peripheral neuropathy, % (n) | 66.7 (14) | 65.9 (29) | 0.952 |

| Diabetic autonomic neuropathy, % (n) | - | 4.5 (2) | 0.321 |

| Diabetic retinopathy, % (n) | 23.8 (5) | 31.8 (14) | 0.507 |

| Diabetic foot, % (n) | 14.3 (3) | 9.1 (4) | 0.527 |

| No complication, % (n) | 28.6 (6) | 29.5 (13) | 0.936 |

| Myocardial infarction, % (n) | - | 4.5 (2) | 0.321 |

| Stroke, % (n) | 9.5 (2) | 6.8 (3) | 0.702 |

| HbA1c, % | 7.86 ± 1.28 | 8.70 ± 1.52 | 0.033 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 5.88 ± 1.70 | 5.65 ± 1.61 | 0.599 |

| Apolipoprotein B, g/L | 0.95 ± 0.32 | 0.97 ± 0.35 | 0.855 |

| Apolipoprotein A1, g/L | 1.79 ± 0.55 | 1.59 ± 0.42 | 0.114 |

| Vitamin D3, ng/mL | 22.24 ± 12.87 | 17.49 ± 7.94 | 0.072 |

| D3 deficiency, % (n) | 61.9 (13) | 68.2 (30) | 0.409 |

| hs-CRP, mg/L | 3.90 ± 2.11 | 5.22 ± 4.28 | 0.188 |

| IL-6, pg/mL | 2.74 ± 2.47 | 3.72 ± 3.43 | 0.249 |

The data are presented as percentages (frequency) and means ± SDs; BMI, body mass index; SUs, sulfonylureas; ADD, antidiabetic drugs; PCS, post-COVID-19 syndrome.

According to laboratory data, more than 60% of patients in both groups were deficient in vitamin D3 (25OH) (Table 1). In the PCS group, a tendency toward lower mean vitamin D3 levels was observed (17.49 ± 7.94 vs. 22.24 ± 12.87 ng/mL, respectively), although these differences were not significant (p = 0.072).

COVID-19-related anamnesis of the study participants

The levels of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and hs-CRP were not significantly greater in group 2 than in group 1 (3.72 ± 3.43 vs. 2.74 ± 2.47 pg/mL (p = 0.249) and 5.22 ± 4.28 vs. 3.90 ± 2.11 mg/L (p = 0.188)), respectively (Table 1).

According to the WHO classification, COVID-19 infection was classified as mild, moderate, or severe18. The main characteristics of the COVID-19 patients are presented in Table 2. In our study, patients who suffered from PCS had a more severe course of COVID-19, though these differences were insignificant. In general, the prevalence of moderate-to-severe COVID-19 infection was 2-fold greater in the PCS group than in the non-PCS group (54.5% vs. 28.6%, p = 0.271; Table 2). Overall, 27.3% of patients needed oxygen support, and 36.4% of patients received glucocorticoids during the acute COVID-19 period, while 9.5% (p = 0.104) and 14.3% (p = 0.067) of patients in the group without PCS, respectively, needed oxygen support. The use of supplements such as zinc, vitamin D3, NSAIDs (76.2% vs. 86.4%; p = 0.306) and/or antibiotics (42.9% vs. 54.5%; p = 0.378) was approximately the same and did not significantly differ between the groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

COVID-19 course and treatment characteristics.

| Parameter | PCS absent (n = 21) |

PCS present (n = 44) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| No treatment, % (n) | 23.8 (5) | 13.6 (6) | 0.306 |

| Supplements/NSAIDs, % (n) | 76.2 (16) | 86.4 (38) | 0.306 |

| Antibiotics, % (n) | 42.9 (9) | 54.5 (24) | 0.378 |

| O2 therapy, % (n) | 9.5 (2) | 27.3 (12) | 0.104 |

| Steroids, % (n) | 14.3 (3) | 36.4 (16) | 0.067 |

| Mechanical ventilation, % (n) | 4.8 (1) | 4.5 (2) | 0.969 |

| COVID-19 severity (WHO), % (n) | 0.271 | ||

| Mild, % (n) | 71.4 (15) | 45.5 (20) | |

| Moderate without hospitalization, % (n) | 14.3 (3) | 27.3 (12) | |

| Moderate with hospitalization, % (n) | 9.5 (2) | 15.9 (7) | |

| Severe, % (n) | 4.8 (1) | 11.3 (5) | |

The data are presented as percentages (frequency); NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; WHO, World Health Organization; PCS, post-COVID-19 syndrome.

Analysis of the mtDNA levels

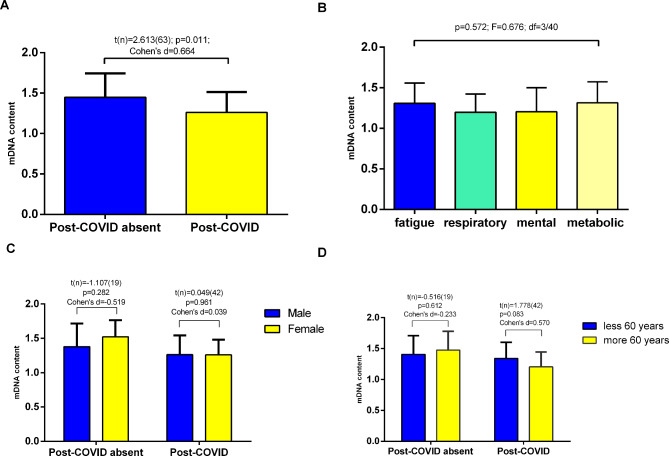

Our results showed that the amount of mtDNA was significantly lower in the PCS than in the comparison group (1.26 ± 0.25 vs. 1.44 ± 0.24 respectively; p = 0.011; Fig. 1A). ANOVA revealed that the content of mtDNA did not differ significantly between the clinical phenotype subgroups (p = 0.572; Fig. 1B). The lowest level of mtDNA (1.19 ± 0.22) was found in patients with the cardio-respiratory disoders. The average amount of mtDNA tended to increase in the following subgroups with the corresponding dominant symptoms: mental (n = 9; 1.20 ± 0.29), fatigue (n = 13; 1.30 ± 0.24) and metabolic (n = 11; 1.31 ± 0.25) disorders (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the mtDNA content in the study participants. Bar plots represent the mean ± standard deviation. A depending on PCS present; B difference between main clinical phenotypes of PCS; C gender-specific analysis (male to female ratio in PCS absent group – 11/10 and in PCS group – 24/20 respectively); D age-dependent analysis (the ratio of younger and older than 60 years in PCS absent group – 9/12 and in PCS group – 18/26 respectively). A, C, D independent Student’s t test; B - One-way ANOVA was used for comparison. *p < 0.05.

According to the gender-specific subanalysis, the mtDNA content was greater in women than in men (1.52 ± 0.24 vs. 1.37 ± 0.33; p = 0.282) among patients without PCS (Fig. 1C). In the PCS group, the mtDNA content did not differ significantly between sexes and was almost the same (1.25 ± 0.22 vs. 1.26 ± 0.28, p = 0.961).

In a comparative age-related assessment, we did not find differences in mtDNA levels among patients younger and older than 60 years (p = 0.612). Notably, in the PCS group, patients older than 60 years demonstrated a lower mtDNA content in leucocytes; however, the difference was not significant (1.20 ± 0.23 vs. 1.34 ± 0.26; p = 0.083) (Fig. 1D).

Uncovering the potential biomarkers of PCS

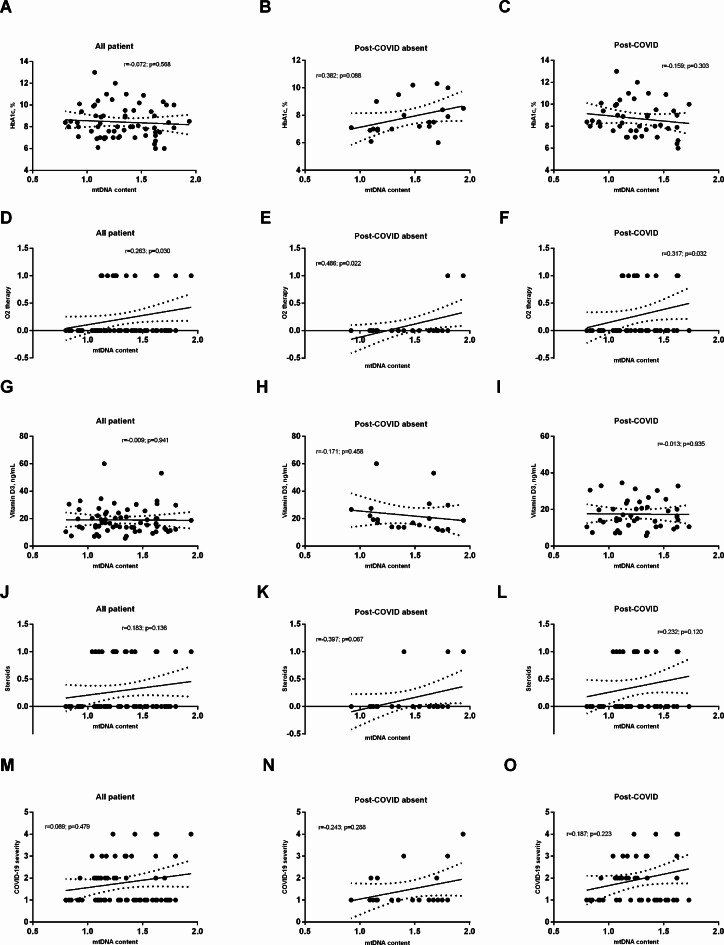

The correlation analysis results are presented in Table 3; Fig. 2. There was a positive correlation between the average amount of mtDNA and weight (r = 0.333; p = 0.027) and apolipoprotein B (r = 0.373; p = 0.013) in patients with PCS. In addition, the mtDNA level moderately correlated with O2 therapy during SARS-CoV-2 infection, especially in patients without PCS (r = 0.486; p = 0.022). Additionally, in this group, a direct correlation was found between mtDNA and antibiotic use (r = 0.562; p = 0.007).

Table 3.

Correlation analysis between mtDNA content and other parameters.

| Parameter | All patients (n = 65) | PCS absent (n = 21) |

PCS present (n = 44) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | -0.192 (0.126) | -0.044 (0.849) | -0.282 (0.064) |

| T2D duration, years | -0.052 (0.682) | 0.233 (0.309) | -0.267 (0.080) |

| HbA1c, % | -0.072 (0.568) | 0.382 (0.088) | -0.159 (0.303) |

| Weight, kg | 0.147 (0.243) | -0.171 (0.460) | 0.333 (0.027)× |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.150 (0.233) | -0.028 (0.903) | 0.293 (0.053) |

| Waist circumference, cm | 0.233 (0.062) | 0.267 (0.242) | 0.283 (0.062) |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 0.143 (0.254) | -0.040 (0.862) | 0.228 (0.137) |

| Apolipoprotein B, g/L | 0.232 (0.063) | 0.013 (0.954) | 0.373 (0.013) |

| Apolipoprotein A1, g/L | -0.023 (0.856) | -0.083 (0.720) | -0.097 (0.531) |

| Vitamin D3, ng/mL | -0.009 (0.941) | -0.171 (0.458) | -0.013 (0.935) |

| hs-CRP, mg/L | 0.025 (0.844) | 0.349 (0.121) | 0.016 (0.916) |

| IL-6, pg/mL | -0.244 (0.049)× | -0.343 (0.128) | -0.166 (0.280) |

| Metformin, % (n) | 0.100 (0.415) | -0.009 (0.967) | 0.116 (0.441) |

| SUs, % (n) | 0.015 (0.901) | 0.322 (0.144) | -0.152 (0.313) |

| DPP-4 inhibitors, % (n) | -0.231 (0.058) | 0.293 (0.186) | -0.242 (0.106) |

| GLP-1 agonists, % (n) | -0.124 (0.313) | -0.138 (0.541) | -0.112 (0.457) |

| SGLT-2 antagonists, % (n) | -0.110 (0.370) | 0.224 (0.317) | -0.173 (0.249) |

| Insulin human, % (n) | -0.158 (0.199) | -0.150 (0.506) | -0.174 (0.248) |

| Insulin analogs, % (n) | 0.098 (0.426) | 0.048 (0.831) | 0.129 (0.393) |

| Supplements/NSAIDs, % (n) | 0.045 (0.717) | 0.001 (0.987) | 0.109 (0.469) |

| Antibiotics, % (n) | 0.118 (0.336) | 0.562 (0.007)× | 0.072 (0.633) |

| O2 therapy, % (n) | 0.263 (0.030)× | 0.486 (0.022)× | 0.317 (0.032)× |

| Steroids, % (n) | 0.183 (0.136) | 0.397 (0.067) | 0.232 (0.120) |

| Mechanical ventilation, % (n) | 0.186 (0.129) | 0.361 (0.098) | -0.141 (0.351) |

The data are presented as r (p); BMI, body mass index; SUs, sulfonylureas; ADD, antidiabetic drugs; PCS, post-COVID-19 syndrome. ×indicates significant changes.

Fig. 2.

Correlation between mtDNA content and most important factors that were included in regression models: HbA1c (A-C); O2 therapy (D-F; 1 - defined as receive treatment); vitamin D3 (J-I); steroid therapy (J-L; 1 - defined as receive treatment) and COVID-19 severity (M-O; 1 defined as mild; 2 - moderate; COVID-19 pneumonia with 10–20% lung damage; 3 - moderate; COVID-19 pneumonia with more than 20% lung damage; 4 - severe).

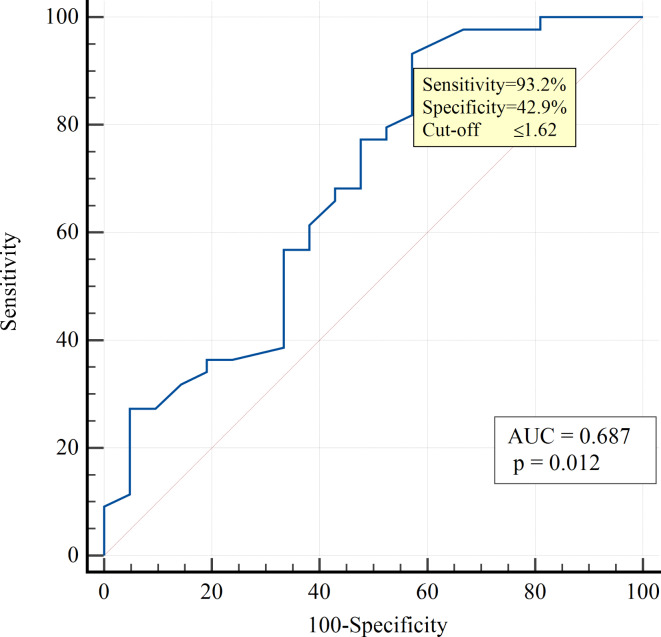

Proinflammatory molecules such as IL-6 and hs-CRP, as well as vitamin D3, may be important markers of COVID-19 severity and poor prognosis and could contribute to the mechanisms of PCS development. In our study, we tested the accuracy of these biomarkers in complex with mtDNA content (Table 4). Univariate logistic regression analysis revealed that mtDNA was an independent predictor associated with the development of PCS in patients with T2D (OR 0.077; 95% CI 0.010–0.612; p = 0.015). From the above-tested biomarkers, the significant AUROC was observed only for mtDNA – 0.687 (95% CI 0.541–0.832; p = 0.012) (Fig. 3). A mtDNA level lower than the cutoff value of ≤ 1.62 was defined as a diagnostic marker of PCS demonstrating high sensitivity (93.2%) and moderate specificity (42.9%), with NPV of 75% and PPV of 77.3%. The overall diagnostic accuracy was 76.9%.

Table 4.

Diagnostic accuracy of mtDNA, vitamin D3, and proinflammatory markers for the prediction of PCS development in patients with T2D.

| Parameter | AUROC | 95% CІ | p (AUROC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| mtDNA content | 0.687 | 0.541–0.832 | 0.012 |

| Vitamin D3, ng/mL | 0.600 | 0.458–0.741 | 0.197 |

| hs-CRP, mg/L | 0.568 | 0.426–0.709 | 0.381 |

| IL-6, pg/mL | 0.586 | 0.443–0.729 | 0.265 |

AUROC, area under the ROC curve; 95% CІ, 95% confidence interval.

Fig. 3.

ROC curves demonstrating the predictive significance of mtDNA for PCS development in T2D patients.

To determine the role of various factors in PCS development after COVID-19 in T2D patients, stepwise multivariate logistic regression analysis was applied (Table 5). The rationale for selecting the variables included in our models was based on previosly published reports which found that lower 25(OH) vitamin D levels were with COVID-19 severity as well as with long COVID-1919. As a result, four different models were built. Model 1 (Nagelkerke R2 = 0,331) and Model 2 (Nagelkerke R2 = 0,334) revealed three main factors linked to PCS, namely, low mtDNA and high HbA1c levels, in combination with either steroid therapy or O2 therapy in the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection. In Model 3, the severity of COVID-19 was the variable of personal history combined with mtDNA and HbA1c, while in the fourth model, oxygen support in the acute phase of COVID-19, current vitamin D3 deficiency, and low mtDNA were linked to PCS (Nagelkerke R2 = 0,316) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Multiple stepwise logistic regression analysis for post-COVID-19 prediction.

| Models | b ± SE | OR (95% CІ) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||

| (Nagelkerke R2 = 0,331) | |||

| Constant | 0.453 ± 2.319 | ||

| mDNA content | -3.371 ± 1.210 | 0.034 (0.003–0.368) | 0.005 |

| HbA1c | 0.537 ± 0.251 | 1.711 (1.047–2.796) | 0.032 |

| Steroids therapy | 1.913 ± 0.844 | 6.774 (1.295–35.426) | 0.023 |

| Model 2 | |||

| (Nagelkerke R2 = 0,334) | |||

| Constant | 0.915 ± 2.335 | ||

| mDNA content | -3.687 ± 1.299 | 0.025 (0.002–0.319) | 0.005 |

| HbA1c | 0.543 ± 0.258 | 1.722 (1.039–2.854) | 0.035 |

| O2 therapy | 2.279 ± 1.016 | 9.764 (1.334–71.452) | 0.025 |

| Model 3 | |||

| (Nagelkerke R2 = 0,335) | |||

| Constant | -0.837 ± 2.415 | ||

| mDNA content | -3.369 ± 1.215 | 0.034 (0.003–0.372) | 0.006 |

| HbA1c | 0.580 ± 0.259 | 1.786 (1.076–2.954) | 0.025 |

| COVID-19 severity | 0.805 ± 0.337 | 2.237 (1.156–4.329) | 0.017 |

| Model 4 | |||

| (Nagelkerke R2 = 0,316) | |||

| Constant | 6.598 ± 1.982 | ||

| mDNA content | -3.648 ± 1.238 | 0.026 (0.002-0.295) | 0.003 |

| O2 therapy | 2.145 ± 0.973 | 8.543 (1.268–57.574) | 0.028 |

| Vitamin D3 | -0.066 ± 0.036 | 0.937 (0.873–1.004) | 0.066 |

PCS prediction modeling results using machine learning

The top 10 models included 7 GBMs, 1 stacked ensemble model, 1 XRT model, and 2 XGBoost models, showing a gradual decline in AUROC values. Among the models tested, GBM was the most effective, with an AUROC of 0.811. The lowest-performing model within the top 10 was another GBM variant with different hyperparameters, with an AUROC of 0.738.

Due to the modest size of our dataset, creating a generalized model for PCS prediction seemed to be not feasible. However, the dataset remains valuable for identifying key variables that warrant further investigation in future studies. To this end, we used permutation feature importance and SHAP values for our analyses.

Permutation feature importance evaluates the impact of individual features on model performance by measuring the decrease in accuracy when the values of a specific feature are randomly shuffled. This disruption of the feature-target relationship reveals the model’s reliance on each feature. This technique is model-agnostic and can be applied iteratively with various permutations, providing robust insights into feature importance. SHAP values determine the significance of each feature by analyzing model predictions both including and excluding the feature for every observation in the training data. This technique provides in-depth insight into the role each feature plays in the model’s predictions.

The hierarchy of permutation feature importance for PCS prediction by the leading model is illustrated in Fig. 4A. A total of 59 features were utilized to develop a model to identify factors associated with PCS. The analysis evaluates the overall impact of each feature, with a specific focus on the top 20 features (Fig. 4B). It not only outlines the significance of these features but also illustrates how this significance varies. HbA1c and mtDNA levels were the primary factors linked to PCS, especially when reviewing the variables vaues across the top 10 models, as illustrated in Fig. 5. The top-performing model identified HbA1c and mtDNA as the most critical factors, followed closely by COVID-19 severity, T2D duration, vitamin D level, and other variables. Lower HbA1c levels were closely associated with a significant reduction in the likelihood of PCS development. For mtDNA, individuals with higher mtDNA levels exhibited a lower probability of PCS, while those with minimal mtDNA content faced an increased risk.

Fig. 4.

The ranking of variables linked to PCS. The figure displays the importance of the top 20 features as determined by permutation analysis (A) and SHAP analysis (B) within the most effective classification model (GBM). In Fig. 2B, the variables are displayed in descending order of impact, with each patient’s representation depicted by a dot on the respective variable line. The position of the dot along the horizontal axis signifies whether a variable’s impact is linked to a higher or lower probability of developing PCS. SHAP values specific to each variable that exceed 0 indicate an elevated risk of PCS. Each row in the figure corresponds to a particular feature, while the x-axis represents the SHAP value. Each data point represents a sample, with colors closer to red indicating higher values and those closer to blue indicating lower values.

Fig. 5.

The permutation importance of the top features was assessed across the top 10 models for PCS identification. Box plots were generated to illustrate the permutation importance of each feature in each model.

Thus, mtDNA and HbA1c were identified as crucial features with contrasting associations with PCS, with mtDNA showing a negative association and HbA1c exhibiting a positive link to PCS. Alternatively, higher mt-DNA values combined with lower HbA1c levels were related to a decreased likelihood of PCS.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the relationship between mt-DNA isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes and PCS development in T2D patients. The results of our study revealed a lower level of mtDNA in the leukocytes of PCS patients with diabetes than in those of the controls. These data reveal the important role of mitochondrial dysfunction in T2D patients after COVID-19 in the development of health-threatening long-term PCS.

Our data demonstrated that decrease of mtDNA was associated with poor prognosis and PCS development. Notably that the changes of mtDNA are alternative to cf-mtDNA dynamics. It is well known that mitochondria are involved in the replication of SARS-CoV-2, which forms double-membrane vesicles and is not detected by the cell defense system. These mitochondrial-entrapped vesicles damage the integrity of the mitochondrial membrane, releasing mt-DNA into the circulation and triggering activation of the host innate immune system, which can aggravate the proinflammatory state7. The results of research conducted during the pandemic illustrated a link between elevated cf-mtDNA and COVID-19 severity and poor prognosis. Notably, cf-mtDNA was eight times greater in patient samples admitted to the intensive care unit due to COVID-19 than in healthy control samples10 reflecting the intensity of mitochondria damage and therefore, mitochondrial function loss. Recent studies demonstrated that cf-mtDNA levels were highly elevated in COVID-19 patients, and adjusting for age, sex, and comorbidities was associated with poor outcomes (death, required ICU admission, intubation, vasopressor use, or renal replacement therapy)15,20. Moreover, cf-mtDNA levels showed excellent predictive performance for in-hospital mortality in COVID-19 patients (AUROC 0.90; 95% CI 0.75–0.90)14. In contrast, Shoraka et al. reported that cf-mtDNA levels were significantly lower in symptomatic COVID-19 patients than in asymptomatic patients21. In contrast, little was known about cellular levels of mtDNA specifically in leucocytes which are essential for immune defense and future tissues repair regulation. With respect to the involvement of mt-DNA in PCS development, scientific data are limited to a few reports showing elevated oxidative mt-DNA damage in patients with fatigue16 and in those experiencing brain fog with decreased concentrations of proteins involved in DNA repair and maintenance of mitochondrial quality during oxidative stress17. Our data are also consistent with the results of a recent study22, which revealed lower PBMC mt-DNA concentrations in patients with severe COVID-19 as compared to patients with mild (p = 0.005) or moderate (p = 0.011) COVID-1922. Moreover, mtDNA levels were significantly lower in patients with lethal outcomes than in survivors22. Thus, a decrease in mtDNA in leukocytes is associated with poor prognosis in patients with COVID-19 and the development of long-term consequences. In our work we revealed the link between white mtDNA decline and PCS development in patients with T2D, and also demonstrated the synergy between glycemic control figures and mitochondrial DNA levels in leucocytes.

The low level of mtDNA in leukocytes may reflect mitochondrial damage induced by inflammation and oxidative stress during SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition to the hypermetabolic response and cell disruption caused by SARS-CoV-2 hijacks mitochondria for replication, causing an alteration in its permeability and leakage of mtDNA into the circulation6,7 and promoting the activation of the immune system, which increases the inflammatory response22. Additionally, mt-DNA is more vulnerable to ROS damage than is nuclear DNA23 because of the lack of effective mt-DNA repair and lack of histone protection24. Once mt-DNA is damaged, the levels of mtDNA are altered and decreased, increasing mitochondrial dysfunction and exacerbating the disease through a positive feedback cycle22,25. Therefore, the detection of a decrease in mtDNA may reflect primary mtDNA damage caused by the COVID-19 inflammatory response and in a prolonged state leading to PCS development.

Moreover, factors such as aging and metabolic reprogramming can deplete mtDNA copy number and reduce mitochondrial biogenesis in T2D patients26. The age-associated decrease in mitochondrial function contributes to various systemic changes, increasing vulnerability to pathological processes and creating a vicious cycle for metabolic disturbances and immune-mediated disorders27. In fact, low mtDNA quantity can reflect mitochondrial dysfunction since mitochondrial DNA encodes 13 proteins involved in the respiratory chain and some proteins regulating the expression of some nuclear genes, including antioxidant response elements (AREs) and ARE-regulating stress-responsive transcription factors, such as nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NFE2L2/NRF2)28,29. Therefore, a decrease in mtDNA can affect not only ATP production but also mitonuclear integration in response to various factors. On the other hand, decreases in mtDNA levels and mitochondrial dysfunction can define the failure of leucocyte activity and therefore altered inflammatory and immune reactions, contributing to the development of PCS after severe COVID-19.

In our study, we were the first to analyze the mtDNA content in terms of different PCS presentations. However, we did not find significant differences in mtDNA levels between the clinical phenotype subgroups (p = 0.572). It is possible that the failure to find links with different functional phenotypes of PCS could be related to the limited sample size.

The multifunctionality of mitochondria contributes to the protection of cells from viral aggression by activating mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS) and mitochondrial DNA-dependent immune activation30. The SARS-CoV-2 virus disrupts mitochondrial function by increasing mitochondrial superoxide anion levels, mitochondrial membrane potential, and mtDNA release31. mtDNA leakage out of cells results in increased cell-free mtDNA content32. The latter can prolong inflammation and promote the aggressiveness of proinflammatory cytokines, as extracellular DNA is detected by immune cells as a pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) that initiates the activation of TLRs and the innate immune response27. For instance, TLR9 triggers inflammatory reactions that lead to endothelial dysfunction and have an impact on the severity of the clinical manifestations of COVID-1931. Clinically, hs-CRP and inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, may be important markers of COVID-19 severity and the development of PCS syndrome. We observed a reverse mild correlation between mtDNA content and IL-6 in all patient analyses.

By defining the possible mechanisms of PCSD development, four multifactorial logistic regression models were built. Importantly, all models defined low mtDNA levels as one of the most significant factors contributing to PCS in diabetic patients. Other biomarkers linked to PCS outcome included HbA1c, which reflects the metabolic control of T2D, and the vitamin D concentration in serum. Vitamin D is one of the key controllers of systemic inflammation, oxidative stress and mitochondrial respiratory function and thus the aging process in humans33. Vitamin D deficiency has been associated with the severity and mortality of COVID-19 patients19, and lower 25(OH) vitamin D levels were also observed in subjects with long COVID-19 than in those without34. In our study, a low serum level of vitamin D3, independent of mtDNA, was a predictor of PCS. Importantly, other predictive factors of PCS development include either clinical features of COVID-19 or Q2 therapy or steroid therapy as a hallmark of SARS-CoV-2 infection severity. These findings support the previously reported link between PCS development and a previous history of COVID-19. Such a link can reflect long-term immune cell dysfunction and possible metabolic reprogramming, revealing the postponed consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection35.

While previous studies have demonstrated the predictive value of HbA1c in evaluating COVID-19 severity in patients with T2D36, our research is among the pioneers in emphasizing the importance of pre-COVID-19 HbA1c levels in predicting PCS. Moreover, HbA1c has been recognized as a potent indicator of biological age, reinforcing the concept that accelerated biological aging may play a crucial role in the onset of PCS37. Further exploration of the regulatory characteristics of HbA1c and mitochondrial damage markers is crucial, as it may aid in identifying effective therapeutic targets and improving the prognosis of patients with a history of PCS. To achieve this goal, various strategies need to be considered for the long-term management of this condition. Combining antidiabetic therapy with mitochondrial therapy, including the antioxidant CoQ10, glycolysis inhibitors, vitamin E, and minerals, as well as regular exercise, may assist patients with PCS symptoms in achieving a faster recovery38,39.

Limitations of the study

This study has several limitations, including its retrospective case‒control design and the limited number of research participants. In addition, we did not have data about COVID-19 vaccination, viral load during the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection or levels of immunoglobulins against SARS-CoV-2.

Conclusion

Various models revealed the most significant links of PCS with mtDNA and HbA1C levels. According to the stepwise multivariate logistic regression analysis, low mtDNA content was associated with PCS development independently of oxygen, glucocorticoid therapy and COVID-19 severity. mtDNA content with a cutoff value ≤ 1.62 can be considered a prognostic biomarker of PCS development in T2D patients.

Methods

Ethics Statement. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee at Bogomolets National Medical University (protocol number: 171/2023) and was conducted according to the guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. The purpose and methodology of the study were fully explained to the participants by the researchers, and all patients were asked to provide informed consent before any study procedures were initiated.

Study design. In this case‒control pilot study, 65 T2D patients from the University Hospitals of Bogomolets National Medical University and Kyiv City Clinical Endocrinology Center were selected. The inclusion criteria were as follows: age over 18 years and the presence of T2D and SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by a positive RT‒PCR test. Patients were subsequently divided into 2 groups depending on PCS presence: the PCS group (main group, n = 44) and the non-PCS group (comparison group, n = 21) at 6 months after COVID-19. PCS was defined according to WHO criteria as the continuation or development of new symptoms 3 months after the initial SARS-CoV-2 infection. Patients with the following PCS clinical phenotypes were included in the study: a predominance of fatigue and/or pain, mental disorders, and cardio-respiratory and metabolic-associated symptoms (which are defined as new-onset T2D or fluctuating, increasing, persistent, relapsing of preexisting chronic complications or a natural course of T2D). Exclusion criteria included type 1 diabetes, secondary diabetes, any type of malignancy, acute infections and chronic failure of visceral organs.

The following information about the patients was collected: anthropometric indicators, T2D duration, existing T2D complications, history of SARS-CoV-2 infection, COVID-19 severity and treatment, post-COVID-19 phenotype and symptoms, duration of post-COVID-19 syndrome and hypoglycemic therapy. According to the WHO classification, SARS-CoV-2 infection was categorized as mild, moderate or severe18. Mild COVID-19 was defined as respiratory symptoms without evidence of pneumonia or hypoxia, while moderate or severe infection corresponded to the presence of clinical and radiological evidence of pneumonia with subsequent assessment of SpO2. In moderate cases, SpO2 was ≥ 90% on room air, while severe COVID-19 was diagnosed when the respiratory rate reached more than 30 breaths/min or SpO2 was < 90% on room air40,41.

Anthropometric data, including weight and height, were measured to the nearest 100 g and 0.5 cm, respectively. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as body weight in kilograms divided by the square of the participant’s height in meters (weight/height2). The waist (narrowest diameter between the xiphoid process and iliac crest) circumference (WC) was also measured.

Laboratory measurements. In the main group, blood samples were drawn from patients admitted to the hospital during the active PCS phase. In the comparison group, blood was collected during the standard follow-up visit during the same period. Venous blood was collected after a 12-h overnight fast in EDTA tubes (with a final concentration of 0.1% EDTA) and in serum separator gel blood collection tubes.

The blood samples were analyzed for complete blood count (Sysmex 550), basic metabolic panel (AU-480, Beckman Coulter), HbA1c level (G8 HPLC Analyzer, Tosoh), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), apolipoprotein A and apolipoprotein B (AU-480, Beckman Coulter), vitamin D, and IL-6 (Maglumi X8, China) in an ISO 15,189 certified laboratory (CSD LAB) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and SOPs. The deficiency of vitamin D3 was determined according to the Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline when the serum vitamin D was less than 20 ng/ml42,43.

mtDNA assessment. DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leucocytes using the phenol–chloroform purification method. The quality of the DNA was assessed using an ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, United States) within the wavelength range of λ220–λ300. To determine the relative mt-DNA content, a standardized quantitative monochrome multiplex real-time polymerase chain reaction (MM-qPCR) method, as proposed by Hsieh44, was employed. This reaction utilized HOT FIREPol® Probe qPCR Mix (Solis BioDyne) with SYBR Green I intercalating dye, following the manufacturer’s instructions, on a Bio-Rad Chromo4 amplifier. For each sample, 10 ng of DNA, a pair of primers for D-loop (D-loop_MPLX_F 5′–ACGCTCGACACACAGCACTTAAACACATCTCTGC–3′ and D-loop_MPLX_R 5′–GCTCAGGTCATACAGTATGGGAGTGRGAGGGRAAAA–3′, final concentration 450 nmol each), and a pair of albumin primers (albu 5′–CGGCGGCGGGCGGGCGGCCGGGGCTGGGCGGCTTCATCCACGTTCACCTTG–3′ and albd 5′–GCCCGGCCCGCCGCGCCCGTCCCGCCGGAGGAGAAGTCTGCCGTT–3′, final concentration 250 nmol each) were added to 18 µL of the reaction mixture, which included betaine at a final concentration of 1 M. All experimental DNA samples were analyzed in triplicate. Instead of Ct values, Cy0 values were used as described by Guescini et al.45. Two standard curves were created: one for the mtDNA signal and another for the single-copy gene signal. The Cy0 values were applied to the calibration curve to evaluate the amount of mtDNA (M) relative to the reference DNA. Similarly, the amount of albumin DNA (S) was assessed. The relative mtDNA content was expressed as the M/S ratio.

Statistical analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using the standard software SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois) and GraphPad Prism, version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) for creating diagrams. The data distribution was analyzed using the Kolmogorov‒Smirnov normality test and for homogeneity of variances Levene’s test. All continuous values are expressed as the mean ± SD, and categorical variables are presented as %. PCS analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to compare the mtDNA content between different clinical phenotypes. The independent samples t test was used to compare differences between groups. If the variances were not homogeneous, we apply Welch’s correction method for the t-test. For comparisons of categorical variables, we conducted a χ2 test. Associations between the mtDNA content and the main parameters were assessed with univariate Pearson’s and Spearman`s correlation analyses. Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine whether mtDNA can predict PCS development in patients with T2D.

To assess the diagnostic accuracy of mtDNA for predicting PCS, we used receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. The ROC curve is a plot of sensitivity (Se) vs. 1-specificity (Sp) for all possible cutoff values. The most commonly used index of accuracy is the area under the ROC curve (AUROC). AUROC values close to 1.0 indicated high diagnostic accuracy. Optimal cutoff values were chosen to maximize the sum of the sensitivity and specificity, and positive predictive values (PPVs) and negative predictive values (NPVs) were computed for these cutoff values46.

Models development. We utilized the open-source H2O.ai autoML package for Python47 on a local device to ensure the confidentiality of patient data. This package allows for the training and cross-validation of several common machine learning algorithms, including gradient boosting machine (GBM), extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), general linear models (GLMs), extremely randomized trees (XRT), distributed random forest (DRF), and deep learning (DL). It also produces two types of stacked ensemble models: one that includes all previously trained models and another that selects the best model from each model family. For further information on model construction and hyperparameter tuning through autoML, refer to the H2O.ai documentation47. Before training, continuous features were transformed via quantile transformation. We then used autoML to train 50 models with 5-fold cross-validation and ranked them based on performance. Permutation importance and Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) were computed for the top 10 models. To address potential overfitting concerns, we examined feature importance across the top-performing models. The rationale behind this approach is that features with a consistently high impact are expected to show high permutation importance across the majority of the top 10 models.

Acknowledgements

none to declare.

Author contributions

N.K., A.M., T.F., V.Y., Y.I., O.S collected and analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. D.K., O.G., A.S., P.B. contributed with data collection. N.K., A.M., O.S. contributed to the study concept and design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The work resulting in this publication was funded by the National Research Foundation of Ukraine under grant agreement No. 2021.01/0213 “Study of the course and consequences of COVID-19 in patients with diabetes and the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the rate of biological aging”.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request to the corresponding author/s.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Falalyeyeva, T. et al. Vitamin D in the prevention and treatment of type-2 diabetes and associated diseases: a critical view during COVID-19 time. Minerva Biotechnol. Biomol. Res.33, (2021).

- 2.Frutos, R., Gavotte, L., Serra-Cobo, J., Chen, T. & Devaux, C. COVID-19 and emerging infectious diseases: the society is still unprepared for the next pandemic. Environ. Res.202, 111676 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petakh, P., Kobyliak, N. & Kamyshnyi, A. Gut microbiota in patients with COVID-19 and type 2 diabetes: a culture-based method. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.13, 1142578 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mittal, J. et al. High prevalence of post COVID-19 fatigue in patients with type 2 diabetes: a case-control study. Diabetes Metabolic Syndrome. 15, 102302 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhowal, C., Ghosh, S., Ghatak, D. & De, R. Pathophysiological involvement of host mitochondria in SARS-CoV-2 infection that causes COVID-19: a comprehensive evidential insight. Mol. Cell. Biochem.478, 1325–1343 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saleh, J., Peyssonnaux, C., Singh, K. K. & Edeas, M. Mitochondria and microbiota dysfunction in COVID-19 pathogenesis. Mitochondrion. 54, 1–7 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valdés-Aguayo, J. J. et al. Mitochondria and mitochondrial DNA: key elements in the Pathogenesis and exacerbation of the inflammatory state caused by COVID-19. Med. (Kaunas Lithuania). 57, 928 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Potus, F. et al. Novel insights on the pulmonary vascular consequences of COVID-19. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol.319, L277–L288 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melchinger, H., Jain, K., Tyagi, T. & Hwa, J. Role of platelet mitochondria: life in a nucleus-free zone. Front. Cardiovasc. Med.6, 153 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Streng, L. W. J. M. et al. In vivo and Ex vivo mitochondrial function in COVID-19 patients on the Intensive Care Unit. Biomedicines. 10, 7161 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medini, H., Zirman, A. & Mishmar, D. Immune system cells from COVID-19 patients display compromised mitochondrial-nuclear expression co-regulation and rewiring toward glycolysis. iScience. 24, 103471 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faizan, M. I. et al. NSP4 and ORF9b of SARS-CoV-2 induce pro-inflammatory mitochondrial DNA release in inner membrane-derived vesicles. Cells. 11, 2969 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andargie, T. E. et al. Cell-free DNA maps COVID-19 tissue injury and risk of death and can cause tissue injury. JCI Insight. 6, e147610 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edinger, F. et al. Peak plasma levels of mtDNA serve as a predictive biomarker for COVID-19 in-hospital mortality. J. Clin. Med.11, 7161 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahmoodpoor, A. et al. Prognostic potential of circulating cell free mitochondrial DNA levels in COVID-19 patients. Mol. Biol. Rep.50, 10249–10255 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofmann, H. et al. Markers of oxidative stress during post-COVID-19 fatigue: a hypothesis-generating, exploratory pilot study on hospital employees. Front. Med.10, 1305009 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanson, B. A. et al. Plasma proteomics show altered inflammatory and mitochondrial proteins in patients with neurologic symptoms of post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Brain. Behav. Immun.114, 462–474 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Living guidance for clinical management of COVID-19. October (2024). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-clinical-2021-2. (Accessed: 3rd.

- 19.Barrea, L. et al. Vitamin D: a role also in long COVID-19? Nutrients. 14, 1625 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scozzi, D. et al. Circulating mitochondrial DNA is an early indicator of severe illness and mortality from COVID-19. JCI Insight. 6, e143299 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shoraka, S., Mohebbi, S. R., Hosseini, S. M. & Zali, M. R. Comparison of plasma mitochondrial DNA copy number in asymptomatic and symptomatic COVID-19 patients. Front. Microbiol.14, 1256042 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valdés-Aguayo, J. J. et al. Peripheral blood mitochondrial DNA levels were modulated by SARS-CoV-2 infection severity and its lessening was Associated with Mortality among hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.11, 754708 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yakes, F. M. & Van Houten, B. Mitochondrial DNA damage is more extensive and persists longer than nuclear DNA damage in human cells following oxidative stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.94, 514–519 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Croteau, D. L., Stierum, R. H. & Bohr, V. A. Mitochondrial DNA repair pathways. Mutat. Res.434, 137–148 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dai, D. F., Rabinovitch, P. S. & Ungvari, Z. Mitochondria and cardiovascular aging. Circul. Res.110, 1109–1124 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boengler, K., Heusch, G. & Schulz, R. Nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins and their role in cardioprotection. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1813, 1286–1294 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan, D. X. Mitochondrial dysfunction, a weakest link of network of aging, relation to innate intramitochondrial immunity of DNA recognition receptors. Mitochondrion. 76, 101886 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mangalhara, K. C. & Shadel, G. S. A mitochondrial-derived peptide exercises the Nuclear option. Cell Metabol.28, 330–331 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pfanner, N., Warscheid, B. & Wiedemann, N. Mitochondrial proteins: from biogenesis to functional networks. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.20, 267–284 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gatti, P., Ilamathi, H. S., Todkar, K. & Germain, M. Mitochondria targeted viral replication and survival strategies-prospective on SARS-CoV-2. Front. Pharmacol.11, 578599 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Costa, T. J. et al. Mitochondrial DNA and TLR9 activation contribute to SARS-CoV-2-induced endothelial cell damage. Vascul. Pharmacol.142, 106946 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang, Y. & McLean, A. S. The role of Mitochondria in the Immune response in critical illness. Crit. Care. (London, England). 26, 80 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wimalawansa, S. J. & Vitamin, D. deficiency: Effects on oxidative stress, epigenetics, gene regulation, and aging. Biology 8, 30 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.di Filippo, L. et al. Low vitamin D levels are Associated with Long COVID Syndrome in COVID-19 survivors. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.108, e1106–e1116 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang, T. et al. COVID-19 metabolism: mechanisms and therapeutic targets. MedComm. 3, e157 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merzon, E. et al. Haemoglobin A1c is a predictor of COVID-19 severity in patients with diabetes. Diab./Metab. Res. Rev.37, e3398 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Belsky, D. W. et al. Quantification of biological aging in young adults. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.112, E4104–E4110 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wood, E., Hall, K. H. & Tate, W. Role of mitochondria, oxidative stress and the response to antioxidants in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: a possible approach to SARS-CoV-2 ‘long-haulers’? Chronic Dis. Translational Med.7, 14–26 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh, I. et al. Persistent Exertional Intolerance after COVID-19: insights from Invasive Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing. Chest. 161, 54–63 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clinical management of COVID-19. https://www.who.int/teams/health-care-readiness/covid-19. (Accessed: 27th March 2024).

- 41.Hegazy, M. A. et al. COVID-19 Disease outcomes: does gastrointestinal Burden play a role? Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol.14, 199–207 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holick, M. F. et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.96, 1911–1930 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aludwan, M. et al. Vitamin D3 deficiency is associated with more severe insulin resistance and metformin use in patients with type 2 diabetes. Minerva Endocrinol.45, 172–180 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsieh, A. Y. Y., Budd, M., Deng, D., Gadawska, I. & Côté, H. C. F. A monochrome Multiplex Real-Time quantitative PCR assay for the measurement of mitochondrial DNA content. J. Mol. Diagnostics: JMD. 20, 612–620 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guescini, M., Sisti, D., Rocchi, M. B. L., Stocchi, L. & Stocchi, V. A new real-time PCR method to overcome significant quantitative inaccuracy due to slight amplification inhibition. BMC Bioinform.9, 326 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mykhalchyshyn, G., Kobyliak, N. & Bodnar, P. Diagnostic accuracy of acyl-ghrelin and it association with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in type 2 diabetic patients. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord.14, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.7th ICML Workshop on Automated Machine Learning. AutoML (2020). https://icml.cc/virtual/2020/workshop/5725. (Accessed: 17th May 2024).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request to the corresponding author/s.