Abstract

Recent studies have shown that base editing, even with single-strand breaks, could result in large deletions of the interstitial regions while targeting homologous regions. Several therapeutically relevant genes such as HBG, HBB, CCR5, and CD33 have homologous sites and are prone for large deletion with base editing. Although the deletion frequency and indels observed are lesser than what is obtained with Cas9, they could still diminish therapeutic efficacy. We sought to evaluate whether these deletions could be overcome while maintaining editing efficiency by using dCas9 fusion of ABE8e in the place of nickaseCas9. Using guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting the γ-globin promoter and the β-globin exon, we evaluated the editing outcome and frequency of large deletion using nABE8e and dABE8e in human HSPCs. We show that dABE8e can edit efficiently while abolishing the formation of large interstitial deletions. Furthermore, this approach enabled efficient multiplexed base editing on complementary strands without generating insertions and deletions. Removal of nickase activity improves the precision of base editing, thus making it a safer approach for therapeutic genome editing.

Keywords: MT: RNA/DNA Editing, base editing, CRISPR-Cas9, gamma globin, hemoglobinopathies, large deletions, multiplexed editing, beta globin, gene editing

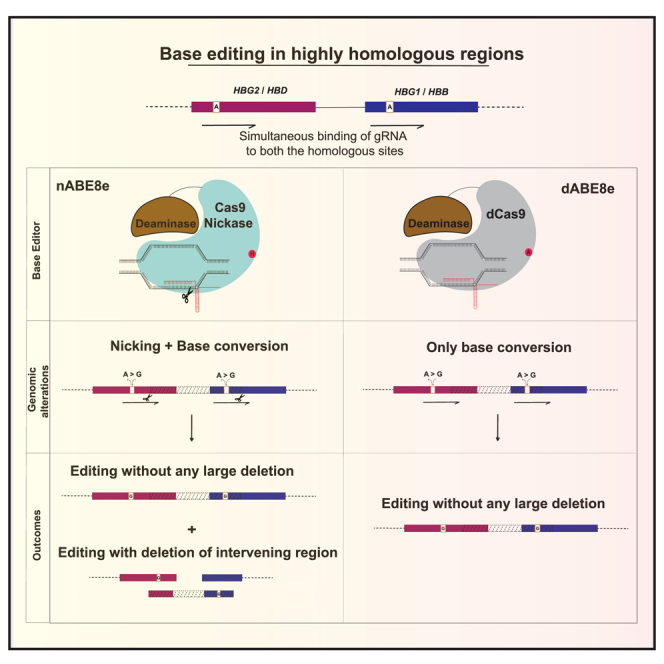

Graphical abstract

Mohankumar and colleagues show that DNA nicks are the main cause for the formation of indels and large deletions while using base editors in homologous regions. They describe the use of a nickase-deficient base editor for efficient editing at these regions without inducing large deletions in human HSPCs.

Introduction

Base editing in the γ-globin promoter for the reactivation of fetal hemoglobin (HbF) or in the β-globin gene for direct correction of mutations is a promising approach for the treatment of β-hemoglobinopathies.1,2,3,4,5 Unlike other loci, the globin locus is highly homologous with the probability of guide RNA (gRNA) binding simultaneously at two or more sites in the locus. Consequently, while using double-strand break (DSB)-mediated approaches, large deletions involving the intervening regions occur in addition to the intended edits.6,7 Although base editing was expected not to cause large deletions due to the absence of DSBs, we and others have observed the occurrence of unintended large deletions in both gamma- and beta-globin genes, possibly because of simultaneous nicking at homologous sites.6,8,9 Recent work also showed that even with a 15% large deletion in input cells, upon long-term engraftment, 50% of the mice harbored large deletions of one of the globin genes, which would mean less hemoglobin production per cell.10 Additionally, the indirect consequences of large deletions such as chromothripsis, translocations, and p53 activation have not been investigated extensively.11,12 Hence, it is important to develop genome editing strategies that generate minimal changes in the genome while achieving therapeutic benefits. Here, we sought to evaluate whether fusing dCas9 (dead Cas9) to ABE8e could overcome deletions generated because of DNA nicks. We show that it not only overcomes large deletions while editing homologous regions but also prevents the formation of insertions or deletions (indels) while base editing in complementary strands.

Results

Frequency of 4.9-kb deletion in the γ-globin locus varies with gRNAs

Base editors were designed to introduce point mutations in the target region while avoiding the DSBs caused by Cas9 nucleases. The initial design of base editors using deaminase fused to a dCas9, however, was less efficient.13,14 The use of D10A nCas9 (nickase Cas9) allowed the nicking of non-edited strands, thereby facilitating the effective installation of edits that resulted in significantly higher editing efficiency. Base editors were subsequently evolved to improve the activity, and the recently described hyperactive variant ABE8e was shown to edit, with conversion reaching ∼100% in many target sites.15 However, the use of nCas9 base editors in highly homologous regions resulted in the deletion of intervening regions.8,9 We hypothesized that with its high processivity, ABE8e would be able to install mutations even when fused to catalytically dCas9 and thus can be used for base editing in homologous regions without risking deletion of the intervening region.

Using previously validated gRNAs8 targeting the γ-globin locus (G2, G3, G11) with the potential for therapeutic applications, we sought to evaluate whether the frequency of 4.9-kb deletion varies between the gRNAs, irrespective of the base editor used (Figure S1). These gRNAs were delivered as lentivirus to D10A nickase HUDEP-2 stables, and the genomic alterations were evaluated. There was no appreciable base conversion or indels except in G11, which showed a very small percentage of indels (Figures S2A and S2D). However, by quantitative real-time PCR we detected large deletions occurring with the use of G2 and G11 but not with G3 (Figure 1A). We believe that gRNA efficiency might be a driving factor in determining the deletion frequency (Figures S2E and S2F; Note S1). While this level of deletion might not be reflected during base editing, it shows the potential for large deletion when the base editing components (gRNA and Base Editor mRNA) are available in excess as in therapeutic ex vivo editing of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs).

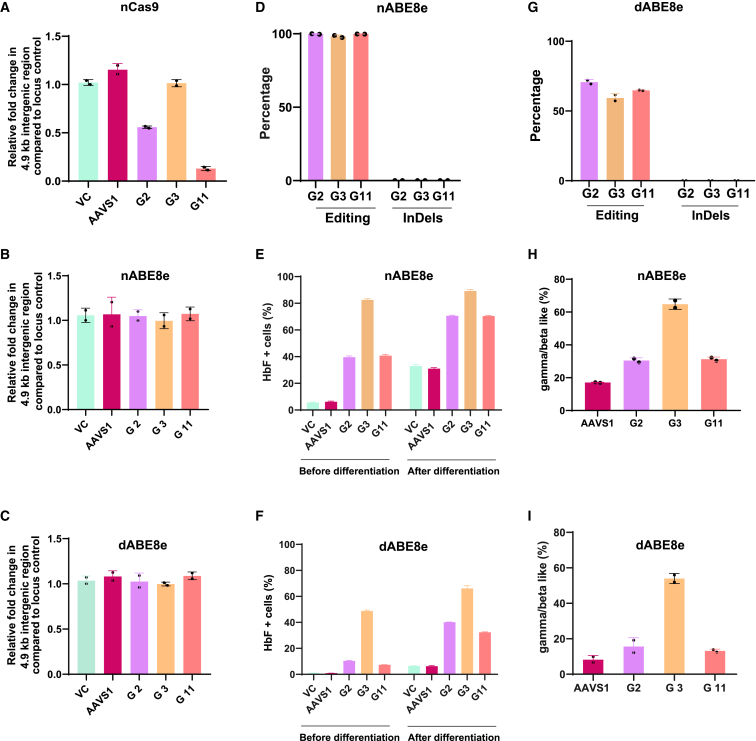

Figure 1.

DNA nickases can introduce large interstitial deletions in homologous regions

(A–C) Quantification of changes in the 4.9-kb intergenic region upon targeting the γ-globin promoter by nCas9 (A), nABE8e (B), and dABE8e (C) in HUDEP 2 cells (by lentiviral delivery), measured as relative fold change compared to locus control by quantitative real-time PCR. (D and G) Editing efficiency and indels generated by nABE8e (D) and dABE8e (G) using gRNAs targeting γ-globin promoter evaluated by next-generation sequencing. (E and F) Percentage of HbF+ cells evaluated by intracellular staining, followed by flow cytometry upon base editing with nABE8e (E) and dABE8e (F) measured before and after erythroid differentiation. (H and I) Measurement of globin chains after base editing in the γ-globin promoter using RP-HPLC in nABE8e (H) and dABE8e (I). All experiments were performed as biological duplicates. Data represented as mean ± SD. VC, vector control.

Nickase-deficient ABE8e can edit efficiently in human erythroid cells

We introduced H840A mutation in nABE8e and tested whether it can edit efficiently to achieve therapeutic benefits. We tested this in HUDEP-2 cells stably expressing nABE8e or dABE8e using the same gRNAs. As expected, all three gRNAs resulted in >90% editing with nABE8e, while the efficiency was ∼60%–70% with dABE8e (Figures 1D, 1G, S2B, and S2C). No indels were detected with either construct, and there was no alteration in the editing window (Figure S2G). We did not observe any significant 4.9-kb deletion in any of the samples by quantitative real-time PCR (Figures 1B and 1C). This suggests that even with nickase activity in nABE8e, rapid kinetics of deaminase resulting in accelerated editing in HUDEP-2 cells likely reduced the deletion frequency, which was not picked up in the quantitative real-time PCR. Corresponding to the editing efficiency, we also observed a drop in HbF levels while editing with dABE8e, but the levels would be sufficient for therapeutic applications in β-hemoglobinopathies (Figures 1E, 1F, 1H, and 1I).

dABE8e can efficiently edit in human CD34+ HSPCs and prevent the formation of interstitial deletions

As nicking by itself can generate large deletions in homologous regions, we evaluated whether the formation of large deletions during base editing in HSPCs can be overcome using dABE8e. We first tested base editing efficiency and the resulting large deletions in CD34+ HSPCs in the therapeutically relevant HBB gene using gRNAs targeting exon-1 with (HBB1) and without (HBB2) homology to HBD gene (Figure S3A). Cells were nucleofected with nABE8e/dABE8e mRNA and the respective single-guide RNA, and as expected, the editing efficiency was slightly reduced while targeting with dABE8e (Figure 2A). Base conversion in HBD and resulting large deletion with nABE8e was observed only in HBB1 gRNA, which had binding sites at both genes and not with HBB2, which had binding sites only in HBB (Figure S3B). However, with dABE8e, large deletion was absent even when very high levels of editing were observed at both genes using HBB1 (Figure 2C). Quantitative real-time PCR with primers specific to large deletion between HBD and HBB showed that nABE8e had a 10-fold increase in amplicons with large deletion compared to unedited control and dABE8e edited samples (Figure 2B).

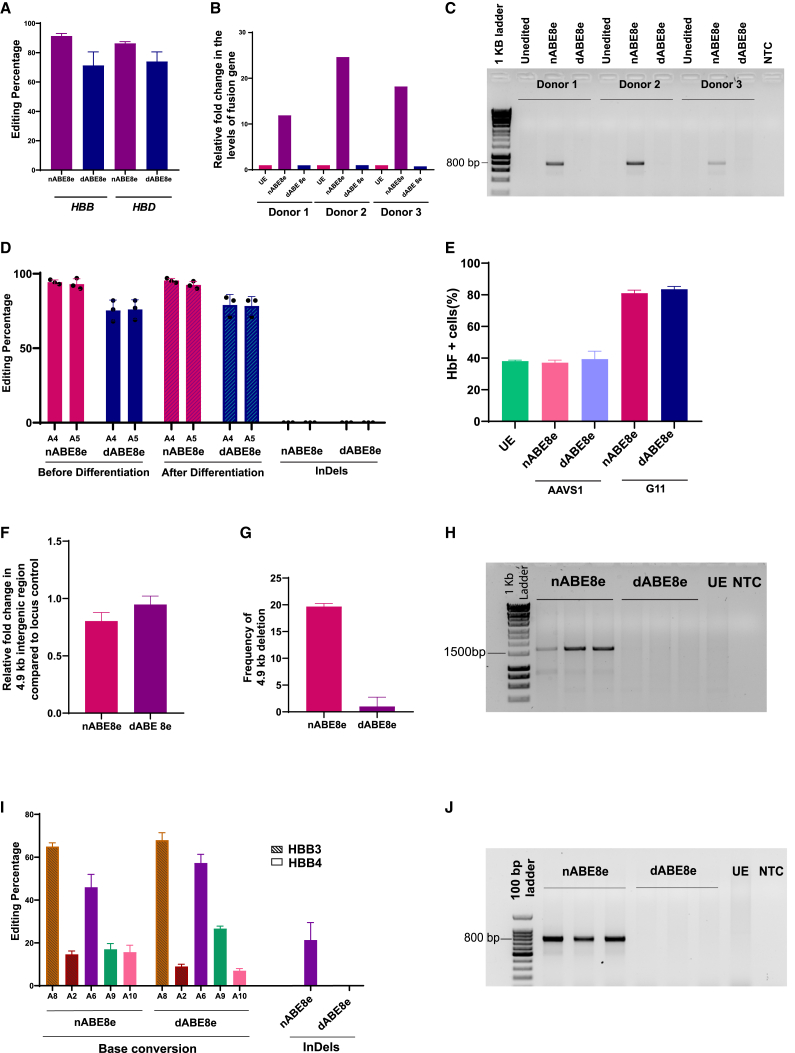

Figure 2.

dABE8e can edit efficiently in HSPCs without generating large deletions

(A) Base editing efficiency of HBB1 gRNA in HBB and HBD genes using ABE8e and dABE8e (by mRNA delivery) measured by Sanger sequencing (n = 3 individual donors). (B) Relative increase in HBD/HBB fusion gene generated by large deletions upon editing with nABE8e and dABE8e compared to unedited control measured by quantitative real-time PCR (performed in three individual donors). (C) Formation of fusion gene (HBD-HBB) due to large deletion upon base editing detected by agarose gel electrophoresis after PCR. A band at ∼800 bp indicates large deletion. (D) Editing efficiency of nABE8e and dABE8e using G11 in γ-globin promoter measured by Sanger sequencing before and after erythroid differentiation. (E) Percentage of HbF+ cells evaluated by flow cytometry after intracellular staining of samples edited with G11 using nABE8e and dABE8e after erythroid differentiation. (F) Reduction in 4.9-kb intergenic region caused by interstitial deletions while targeting the γ-globin promoter using G11 measured as relative fold change compared to locus control by quantitative real-time PCR and normalized using unedited control. (G) Frequency of 4.9-kb deletion created by base editors while targeting the γ-globin promoter by G11 measured by probe-based droplet digital (ddPCR) and compared to unedited control. (H) Formation of fusion gene (HBG2-HBG1) due to large deletion on base editing detected by agarose gel electrophoresis following PCR. A band at ∼1,700 bp indicates large deletion. (I) Editing efficiency and indel formation upon multiplex editing with two sgRNAs targeting the complementary strands in β-globin exon 1(HBB3/HBB4) measured by Sanger sequencing. (J) Formation of fusion gene (HBD-HBB) due to large deletion after multiplexed base editing detected by agarose gel electrophoresis after PCR. A band at ∼800 bp indicates large deletion. (n= 3 for all experiments. Data represented as mean ± SD. NTC, non-templated control; UE, unedited control).

We further compared both of the editors in the HBG promoter. G11 was used along with AAVS1 targeting gRNA as the negative control. While the editing efficiency reached >90% in nABE8e, it was slightly lower in dABE8e (Figures 2D and S3C). As expected, we observed the 4.9-kb deletion with nABE8e but not in dABE8e (Figures 2F–2H). The edited cells upon differentiation showed similar elevation in F+ cells reaching close to 80% in both nABE8e and dABE8e, suggesting that editing by dABE8e would be sufficient for therapeutically relevant HbF elevation (Figure 2E). We also tested two other gRNAs in the HBG promoter that were shown to elevate HbF to therapeutic levels and found that while editing efficiency with dABE8e was slightly lower than what was observed with nABE8e, it abolished the creation of the 4.9-kb deletion (Figures S3D–S3G).

Additionally, we tested the utility of dABE8e in preventing indel formation during multiplexed editing in complementary strands using two sgRNAs targeting the HBB gene (HBB3 and HBB4) (Figure S4A). While nABE8e resulted in indel formation due to nicking on opposite strands, dABE8e resulted in pure base conversion without any indels/large deletions (Figures 2I, 2J, and S4B). These data suggest that simultaneous nicking in the homologous site during base editing with nABE8e is responsible for large deletions and can be overcome using dABE8e.

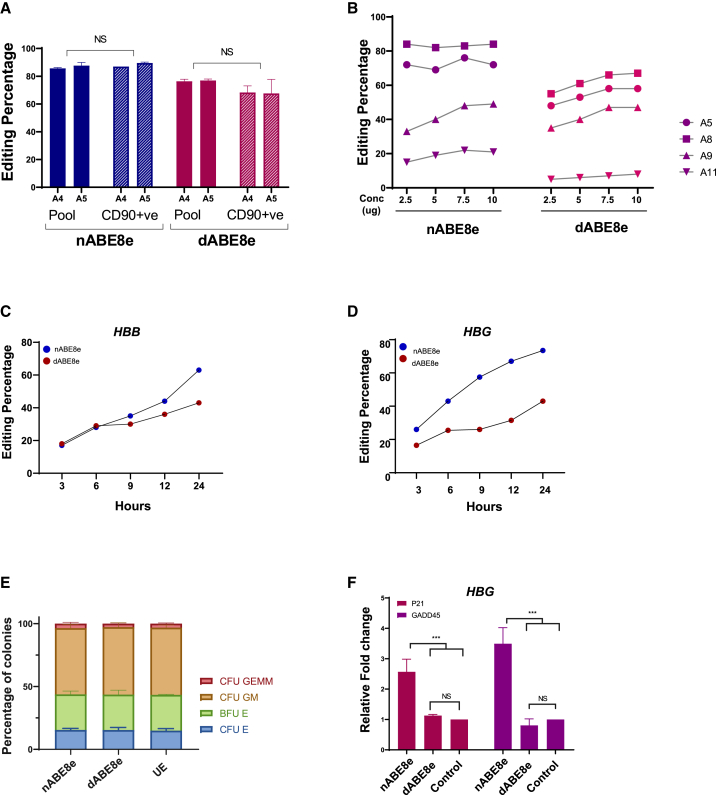

Characterization of dABE8e activity in CD34+ HSPCs

As dABE8e showed slightly reduced editing compared to nABE8e at all the sites, we evaluated whether this was due to the limited editing efficiency of dABE8e in the more primitive quiescent cells. The editing efficiency of nABE8e and dABE8e was compared in CD90+ primitive HSPCs with that of bulk edited cells, and no significant difference was observed (Figures 3A and S5). We also tested whether increasing the base editor cargo would improve the editing efficiency in target sites that showed moderate editing efficiency, but we did not observe any appreciable improvement in editing, even with a 4-fold increase in the cargo, suggesting that reagent availability is not the limiting factor for editing at these sites (Figures 3B and S3H). It was also noted that both nABE8e and dABE8e started editing within 3 h of nucleofection, but the editing kinetics is much faster in nABE8e (Figures 3C and 3D). The edited cells were also subjected to clonogenic assay, and we observed no difference in colony-forming potential between the samples (Figure 3E). Finally, we tested the levels of P21 and GADD45, both markers of DNA damage response and observed that while nABE8e showed a slight elevation in RNA levels, dABE8e and the mock electroporated sample showed similar levels (Figure 3F). Thus, dABE8e would be a better approach, in terms of purity of outcomes, while editing regions that are highly homologous and during multiplexed editing for therapeutic applications.

Figure 3.

Characterization of nABE8e and dABE8e activity in HSPCs

(A) Base editing efficiency of nABE8e and dABE8e (by mRNA delivery) in a pool of HSPCs and in a primitive (CD90+) population, with G11 targeting γ-globin promoter measured by Sanger sequencing (n = 3). Student t test was used for comparison between the groups. (B) Comparison of base editing efficiency with escalating doses of base editors in HSPCs using G2 targeting γ-globin promoter after 48 h of electroporation measured by Sanger sequencing (n = 1). (C and D) Evaluation of base editing efficiency over time after electroporation in HSPCs using HBB1 (C) and HBG G11 (D) gRNAs measured by Sanger sequencing (n = 1). (E) Percentage of colonies formed from base edited HSPCs compared to unedited (mock electroporated) control after 14 days of seeding in MethoCult medium (n = 3). (F) Relative fold change in mRNA expression of P21 and GADD45 genes after 48 h of electroporation (mRNA) by HBG G4 measured by quantitative real-time PCR. Data are normalized to mock electroporated control (G4 gRNA, n = 3). (ANOVA with multiple comparisons was used for evaluating statistical significance.) Data represented as mean ± SD. ∗∗∗p < 0.001. NS, nonsignificant; UE, unedited control.

Discussion

As base editors are entering into clinical trials for the treatment of various disorders, there is an increasing interest in improving the precision of genome editing while minimizing undesired genomic alterations.16,17 With precision genome engineering, there is often a very limited number of available gRNAs to generate the desired mutation, and hence the base editors must be precise, with minimal undesired outcomes.3,18,19,20 It has been reported that base editors generate undesired genotoxic effects due to DNA nicking11 and that single-strand breaks can have detrimental effects on cell fitness.21 In this study, we show that large deletions are generated in homologous regions during base editing in a gRNA-dependent manner. These deletions can be overcome using nickase-deficient dABE8e that can edit efficiently even in CD34+ HSPCs. The editing occurs even in CD90+ HSPCs, and the edited cells show no lineage bias, suggesting the potential for long-term engraftment and repopulation. The editing efficiency by dABE8e is, however, lower than nABE8e by 20%–30% in all target sites tested. Hence, in non-homologous regions or sites that do not cause the formation of indels, nABE8e can be used because it would provide better editing efficiency. While here we demonstrate only the use of dABE8e, it is similarly possible to develop nickase-deficient cytosine base editors (CBEs) using hyperactive variants of CBEs.22 A recent study has shown the proof of concept for overcoming indels using nickase-deficient CBEs.23 In addition to targeting the homologous regions, dABE8e can be used for multiplexed editing in a single locus or simultaneous editing in complementary strands without risking the generation of large deletions or indels.

There are, however, certain limitations to our study. First, the approach was tested in two sites in the globin locus (HBG and HBB genes) to evaluate the abolishment of large deletions. There are other homologous loci such as CCR5 and CD33 that can be tested for the same. Additionally, cell-cycle dependence of dABE8e-mediated editing was not directly tested, and only an engraftment study would show the long-term repopulation potential of the cells edited with dABE8e. Considering the in vitro data, we believe that nABE8e is still a better option in non-homologous sites as the editing efficiency is evidently higher compared to dABE8e. However, dABE8e would be a suitable approach in terms of purity of outcomes while base editing in situations where two or more nicks are introduced in the same locus as in homologous regions or during multiplexed editing.

Materials and methods

Details of materials and methods used in the study can be found in the supplemental information.

Data and code availability

All data generated from this study have been made available in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the Mohankumar lab members for helpful suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript. HUDEP2 cells were a gift from Yukio Nakamura and Ryo Kurita. The study was funded by the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India (BT/PR45683/MED/31/465/2022). A.G. is supported by a senior research fellowship from the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, India. We would like to acknowledge the Centre For Stem Cell Research (CSCR) core facility for supporting us with all the necessary instrumentation to carry out this work. We also thank Dr. Aswin Pai and Dr. Poonkuzhali B for helping with reversed-phase-high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) and Dr. Rekha Pai and Mr. Dhananjayan for helping with the droplet digital PCR.

Author contributions

A.G.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, visualization, data curation, and writing – original draft. P.S., N.S.R., and B.V.: methodology. S.M., S.T., and S.R.V.: resources. A.S.: resources and project administration. M.K.M.M.: conceptualization, supervision, formal analysis, funding acquisition, project administration, resources, and writing – review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version of the paper.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2024.102347.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Newby G.A., Yen J.S., Woodard K.J., Mayuranathan T., Lazzarotto C.R., Li Y., Sheppard-Tillman H., Porter S.N., Yao Y., Mayberry K., et al. Base editing of haematopoietic stem cells rescues sickle cell disease in mice. Nature. 2021;595:295–302. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03609-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liao J., Chen S., Hsiao S., Jiang Y., Yang Y., Zhang Y., Wang X., Lai Y., Bauer D.E., Wu Y. Therapeutic adenine base editing of human hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:207. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-35508-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayuranathan T., Newby G.A., Feng R., Yao Y., Mayberry K.D., Lazzarotto C.R., Li Y., Levine R.M., Nimmagadda N., Dempsey E., et al. Potent and uniform fetal hemoglobin induction via base editing. Nat. Genet. 2023;55:1210–1220. doi: 10.1038/s41588-023-01434-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbarani G., Łabedz A., Ronchi A.E. β-Hemoglobinopathies: The Test Bench for Genome Editing-Based Therapeutic Strategies. Front. Genome Ed. 2020;2 doi: 10.3389/fgeed.2020.571239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martyn G.E., Wienert B., Yang L., Shah M., Norton L.J., Burdach J., Kurita R., Nakamura Y., Pearson R.C.M., Funnell A.P.W., et al. Natural regulatory mutations elevate the fetal globin gene via disruption of BCL11A or ZBTB7A binding. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:498–503. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li C., Georgakopoulou A., Mishra A., Gil S., Hawkins R.D., Yannaki E., Lieber A. In vivo HSPC gene therapy with base editors allows for efficient reactivation of fetal γ-globin in β-YAC mice. Blood Adv. 2021;5:1122–1135. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park S.H., Cao M., Pan Y., Davis T.H., Saxena L., Deshmukh H., Fu Y., Treangen T., Sheehan V.A., Bao G. Comprehensive analysis and accurate quantification of unintended large gene modifications induced by CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. Sci. Adv. 2022;8 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abo7676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravi N.S., Wienert B., Wyman S.K., Bell H.W., George A., Mahalingam G., Vu J.T., Prasad K., Bandlamudi B.P., Devaraju N., et al. Identification of novel HPFH-like mutations by CRISPR base editing that elevate the expression of fetal hemoglobin. Elife. 2022;11 doi: 10.7554/eLife.65421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prasad K., Devaraju N., George A., Ravi N.S., Paul J., Mahalingam G., Rajendiran V., Panigrahi L., Venkatesan V., Lakhotiya K., et al. Precise correction of a spectrum of β-thalassemia mutations in coding and non-coding regions by base editors. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2024;35 doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2024.102205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antoniou P., Hardouin G., Martinucci P., Frati G., Felix T., Chalumeau A., Fontana L., Martin J., Masson C., Brusson M., et al. Base-editing-mediated dissection of a γ-globin cis-regulatory element for the therapeutic reactivation of fetal hemoglobin expression. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:6618. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34493-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiumara M., Ferrari S., Omer-Javed A., Beretta S., Albano L., Canarutto D., Varesi A., Gaddoni C., Brombin C., Cugnata F., et al. Genotoxic effects of base and prime editing in human hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024;42:877–891. doi: 10.1038/s41587-023-01915-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enache O.M., Rendo V., Abdusamad M., Lam D., Davison D., Pal S., Currimjee N., Hess J., Pantel S., Nag A., et al. Cas9 activates the p53 pathway and selects for p53-inactivating mutations. Nat. Genet. 2020;52:662–668. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0623-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Komor A.C., Kim Y.B., Packer M.S., Zuris J.A., Liu D.R. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature. 2016;533:420–424. doi: 10.1038/nature17946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaudelli N.M., Komor A.C., Rees H.A., Packer M.S., Badran A.H., Bryson D.I., Liu D.R. Programmable base editing of A·T to G·C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature. 2017;551:464–471. doi: 10.1038/nature24644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richter M.F., Zhao K.T., Eton E., Lapinaite A., Newby G.A., Thuronyi B.W., Wilson C., Koblan L.W., Zeng J., Bauer D.E., et al. Phage-assisted evolution of an adenine base editor with improved Cas domain compatibility and activity. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:883–891. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0453-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naddaf M. First trial of ‘base editing’ in humans lowers cholesterol — but raises safety concerns. Nature. 2023;623:671–672. doi: 10.1038/d41586-023-03543-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robert C., Christos G., Farhatullah S., Hong Z., Annie E., Athina G.S., Roland P., Giorgio O., Toni B., Jan C., et al. Base-Edited CAR7 T Cells for Relapsed T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023;389:899–910. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2300709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Badat M., Ejaz A., Hua P., Rice S., Zhang W., Hentges L.D., Fisher C.A., Denny N., Schwessinger R., Yasara N., et al. Direct correction of haemoglobin E β-thalassaemia using base editors. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:2238. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-37604-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardouin G., Antoniou P., Martinucci P., Felix T., Manceau S., Joseph L., Masson C., Scaramuzza S., Ferrari G., Cavazzana M., Miccio A. Adenine base editor–mediated correction of the common and severe IVS1-110 (G>A) β-thalassemia mutation. Blood. 2023;141:1169–1179. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022016629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naiisseh B., Papasavva P.L., Papaioannou N.Y., Tomazou M., Koniali L., Felekis X., Constantinou C.G., Sitarou M., Christou S., Kleanthous M., et al. Context base editing for splice correction of IVSI-110 β-thalassemia. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2024;35 doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2024.102183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caldecott K.W. Causes and consequences of DNA single-strand breaks. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2024;49:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2023.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neugebauer M.E., Hsu A., Arbab M., Krasnow N.A., McElroy A.N., Pandey S., Doman J.L., Huang T.P., Raguram A., Banskota S., et al. Evolution of an adenine base editor into a small, efficient cytosine base editor with low off-target activity. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023;41:673–685. doi: 10.1038/s41587-022-01533-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoon D.E., Kim N.-R., Park S.-J., Jeong T.Y., Eun B., Cho Y., Lim S.-Y., Lee H., Seong J.K., Kim K. Precise base editing without unintended indels in human cells and mouse primary myoblasts. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023;55:2586–2595. doi: 10.1038/s12276-023-01128-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated from this study have been made available in this paper.