Abstract

Background

Depression is common in primary care and is associated with marked personal, social and economic morbidity, thus creating significant demands on service providers. The antidepressant fluoxetine has been studied in many randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in comparison with other conventional and unconventional antidepressants. However, these studies have produced conflicting findings. Other systematic reviews have considered selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRIs) as a group which limits the applicability of the findings for fluoxetine alone. Therefore, this review intends to provide specific and clinically useful information regarding the effects of fluoxetine for depression compared with tricyclics (TCAs), SSRIs, serotonin‐noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and newer agents, and other conventional and unconventional agents.

Objectives

To assess the effects of fluoxetine in comparison with all other antidepressive agents for depression in adult individuals with unipolar major depressive disorder.

Search methods

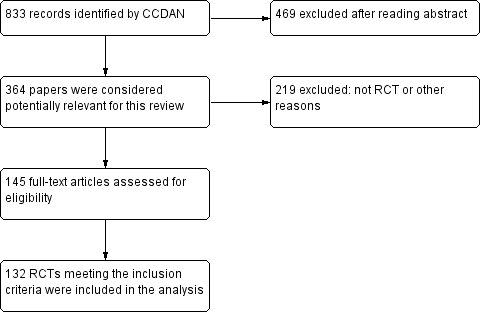

We searched the Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Review Group Controlled Trials Register (CCDANCTR) to 11 May 2012. This register includes relevant RCTs from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (all years), MEDLINE (1950 to date), EMBASE (1974 to date) and PsycINFO (1967 to date). No language restriction was applied. Reference lists of relevant papers and previous systematic reviews were handsearched. The pharmaceutical company marketing fluoxetine and experts in this field were contacted for supplemental data.

Selection criteria

All RCTs comparing fluoxetine with any other AD (including non‐conventional agents such as hypericum) for patients with unipolar major depressive disorder (regardless of the diagnostic criteria used) were included. For trials that had a cross‐over design only results from the first randomisation period were considered.

Data collection and analysis

Data were independently extracted by two review authors using a standard form. Responders to treatment were calculated on an intention‐to‐treat basis: dropouts were always included in this analysis. When data on dropouts were carried forward and included in the efficacy evaluation, they were analysed according to the primary studies; when dropouts were excluded from any assessment in the primary studies, they were considered as treatment failures. Scores from continuous outcomes were analysed by including patients with a final assessment or with the last observation carried forward. Tolerability data were analysed by calculating the proportion of patients who failed to complete the study due to any causes and due to side effects or inefficacy. For dichotomous data, odds ratios (ORs) were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using the random‐effects model. Continuous data were analysed using standardised mean differences (SMD) with 95% CI.

Main results

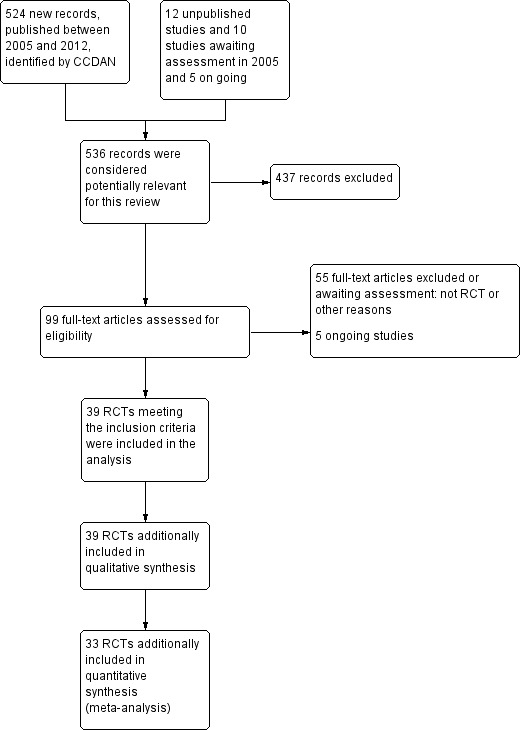

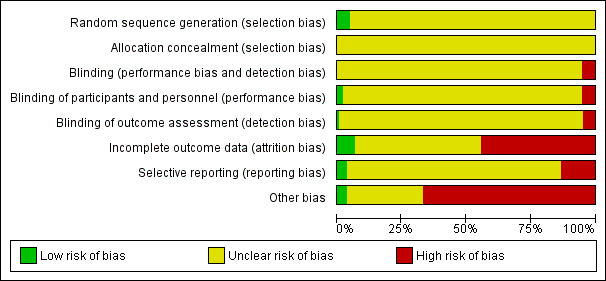

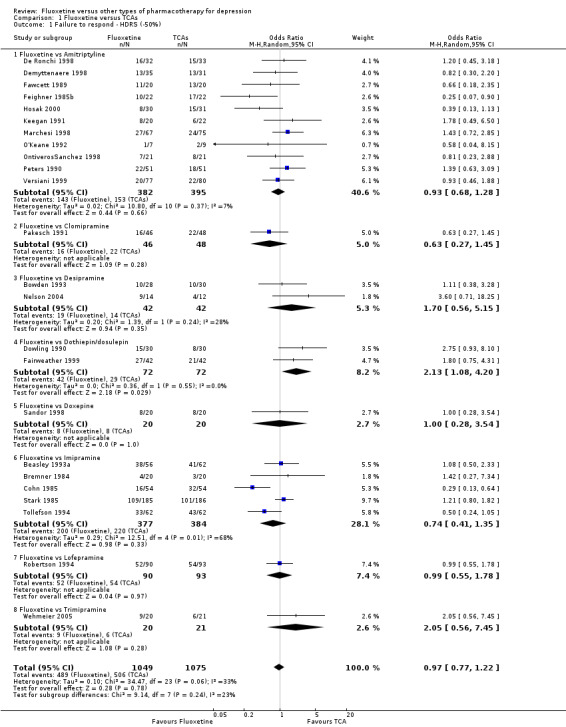

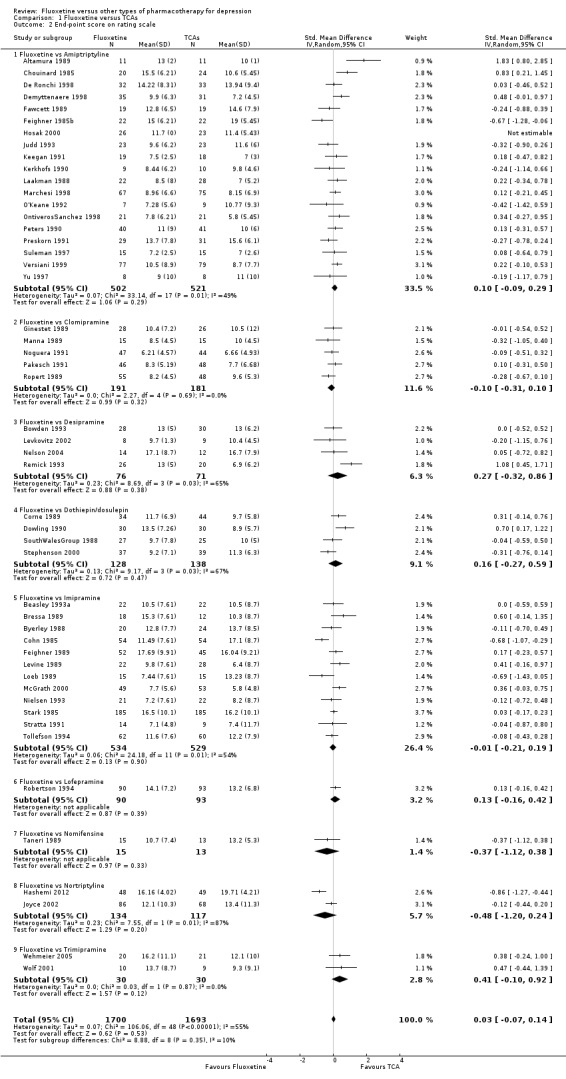

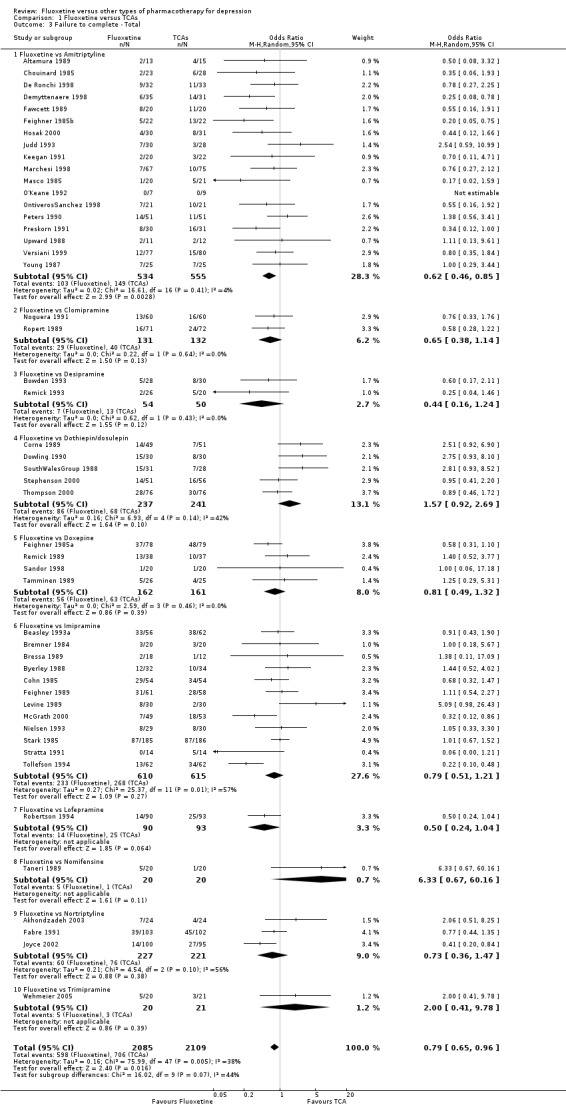

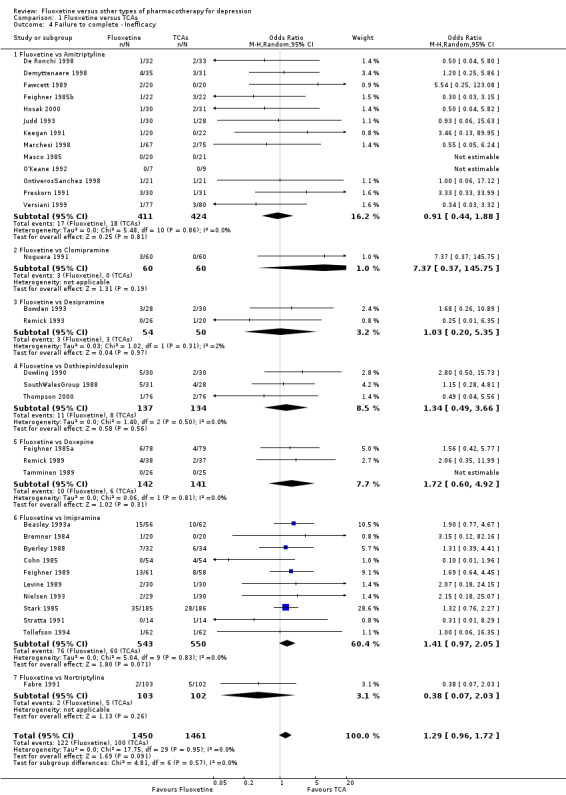

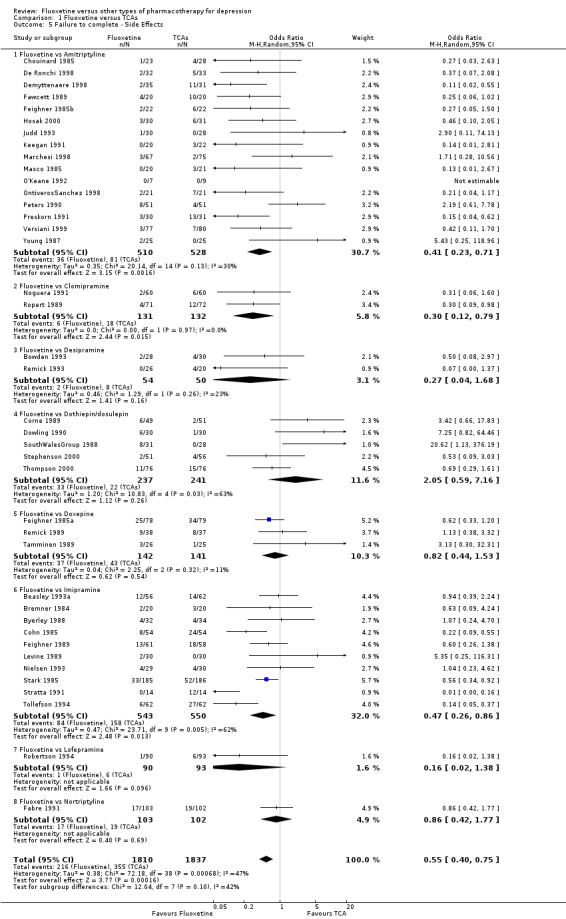

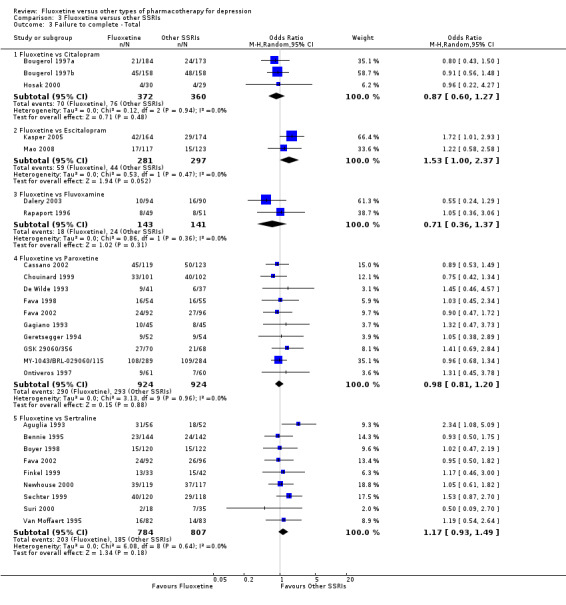

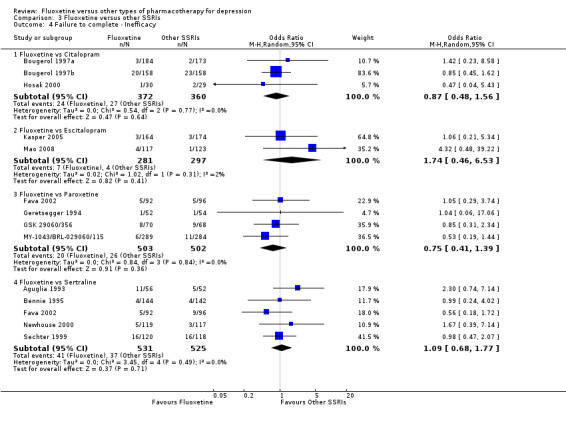

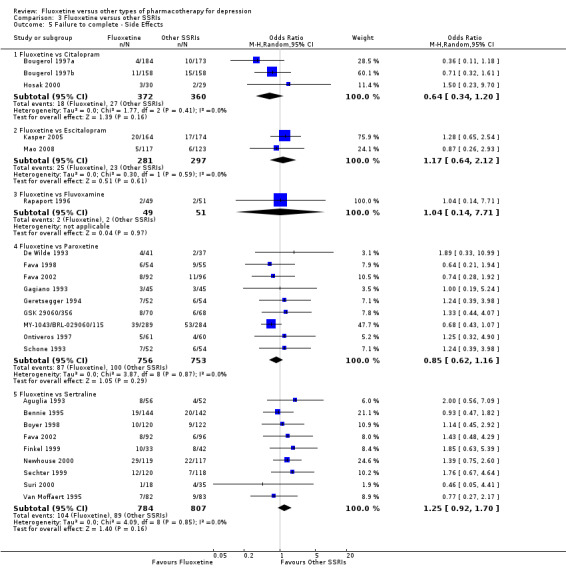

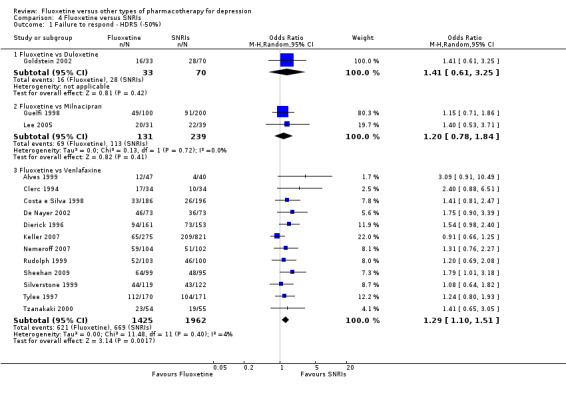

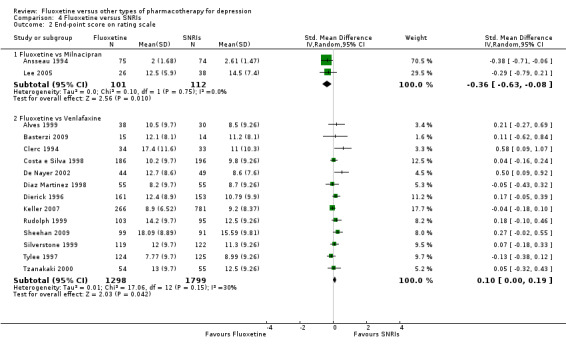

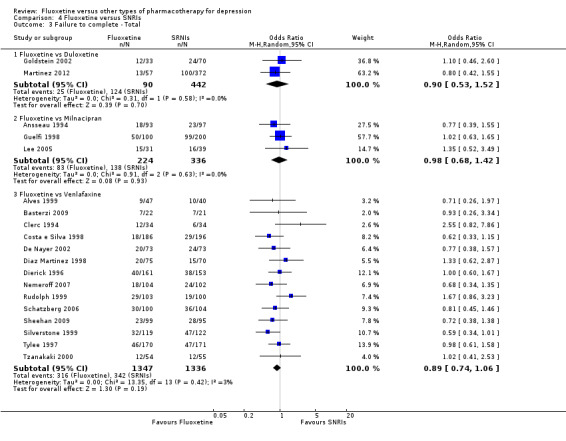

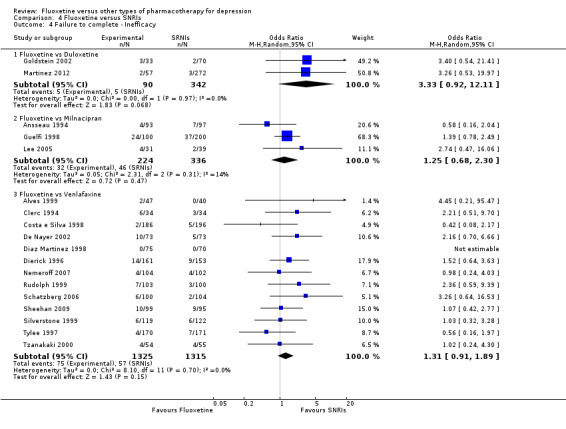

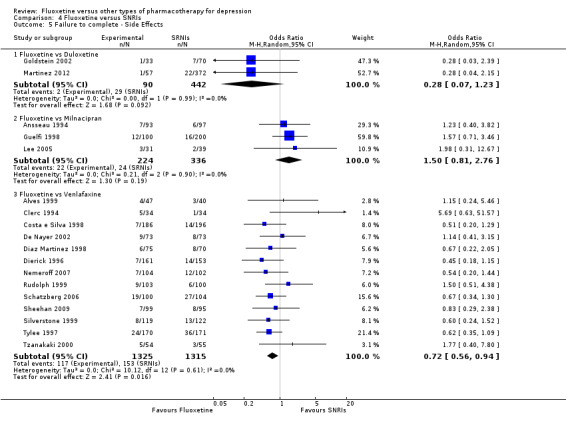

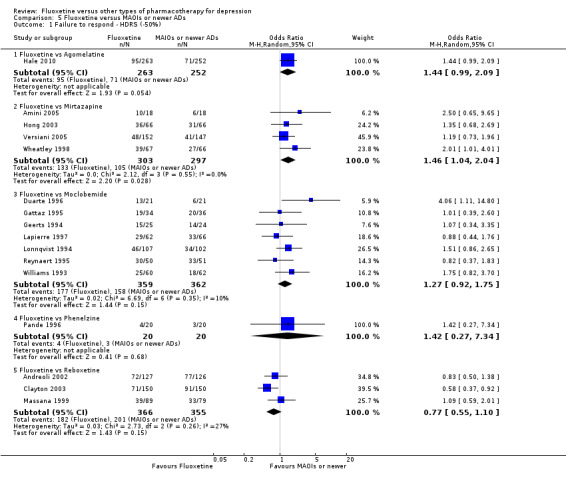

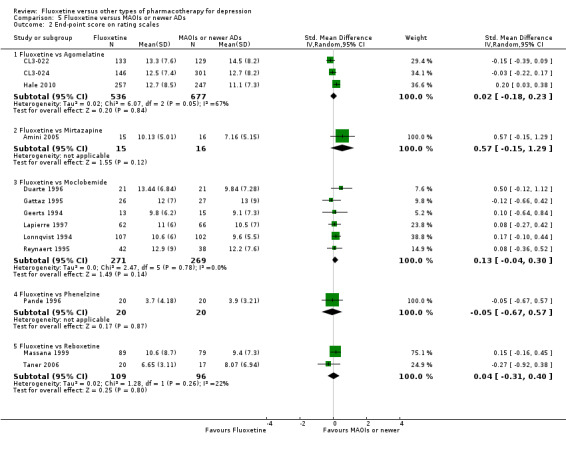

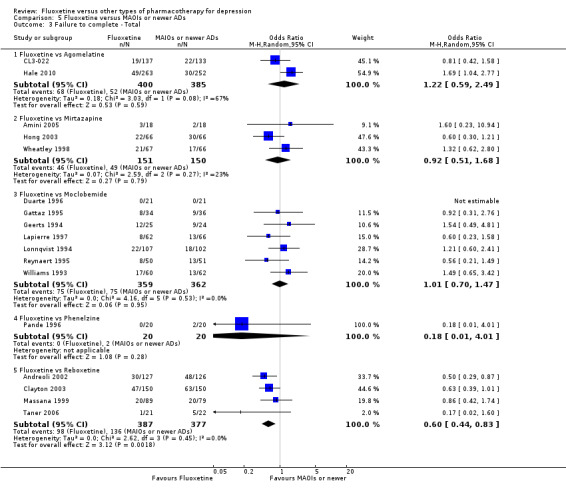

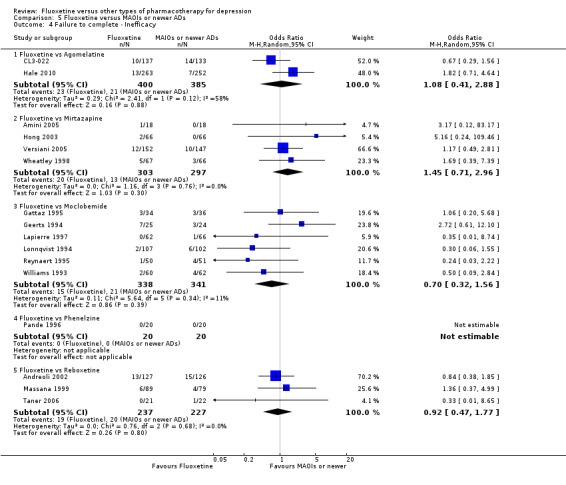

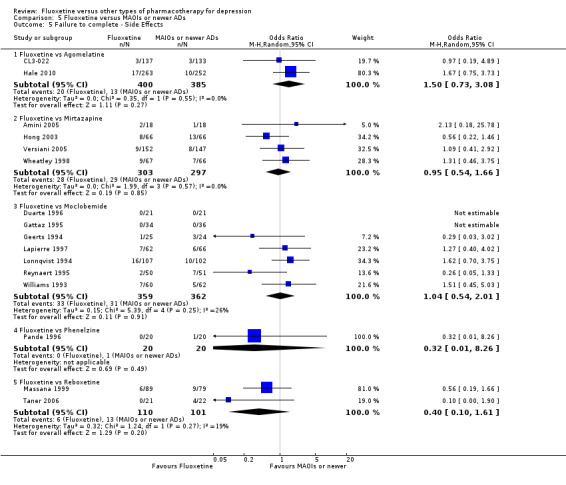

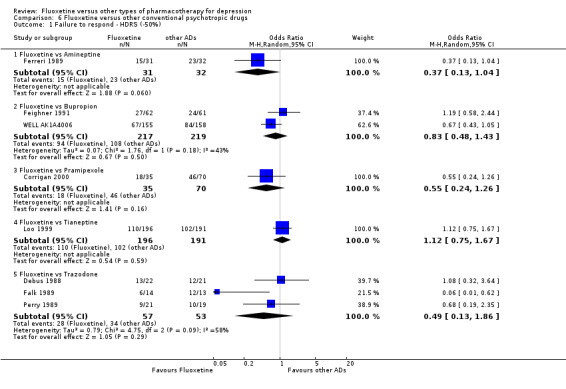

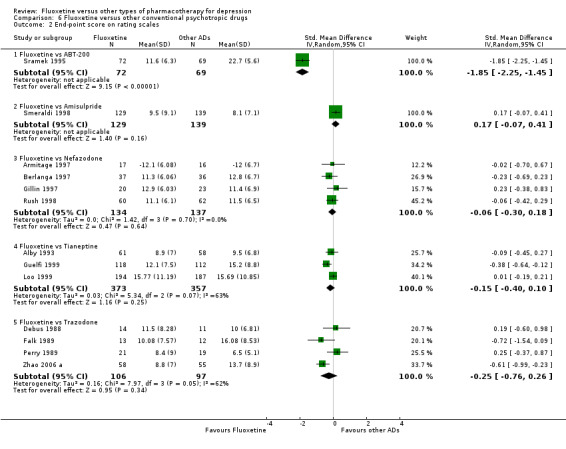

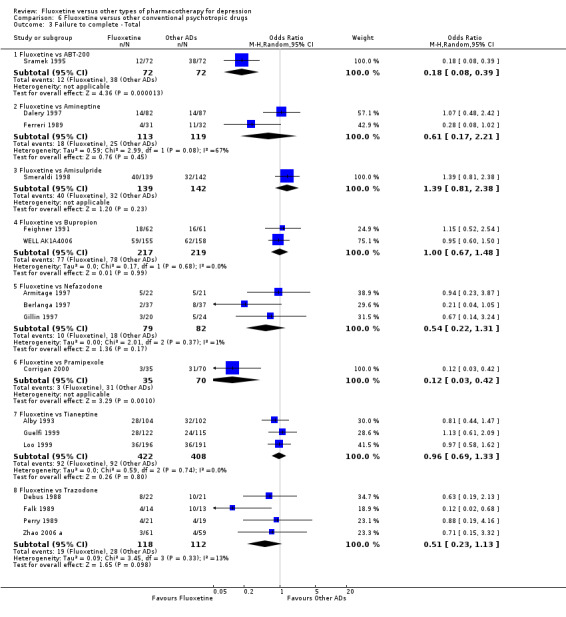

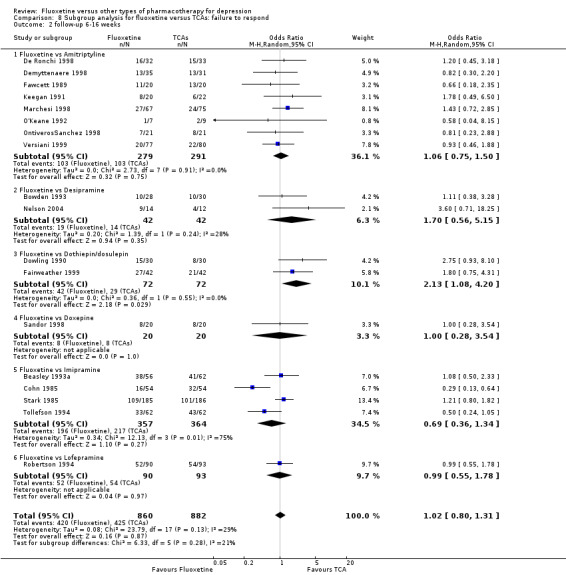

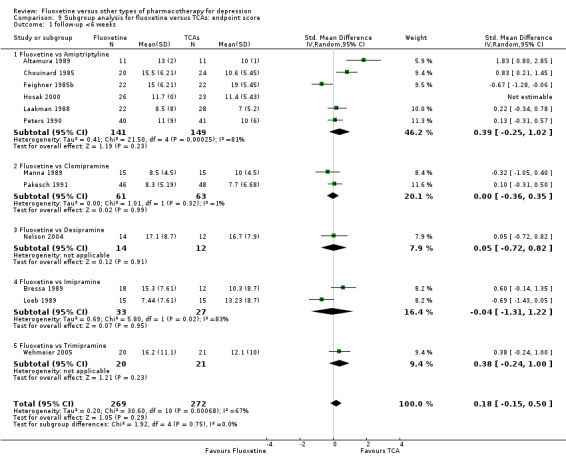

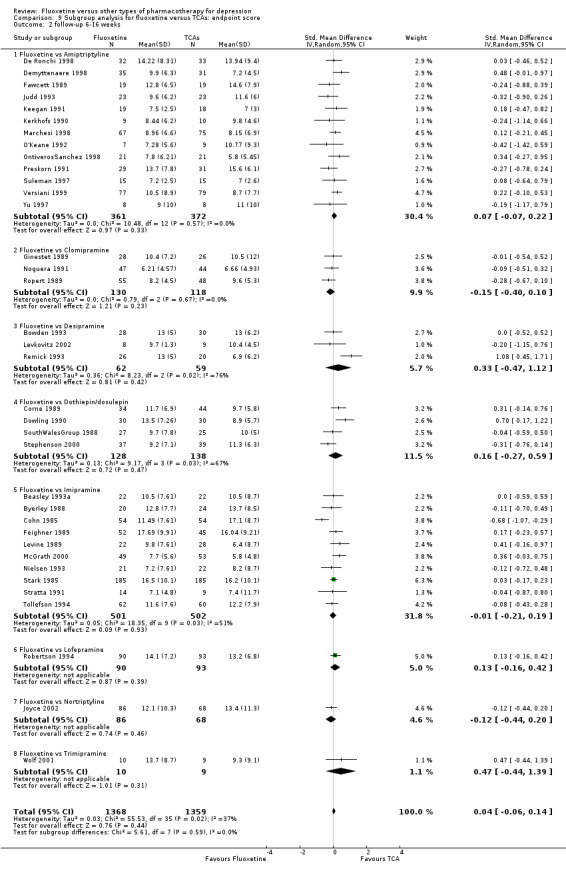

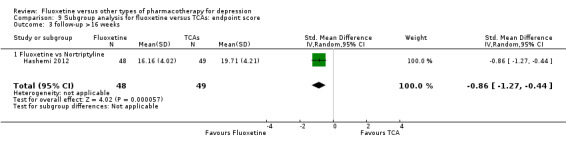

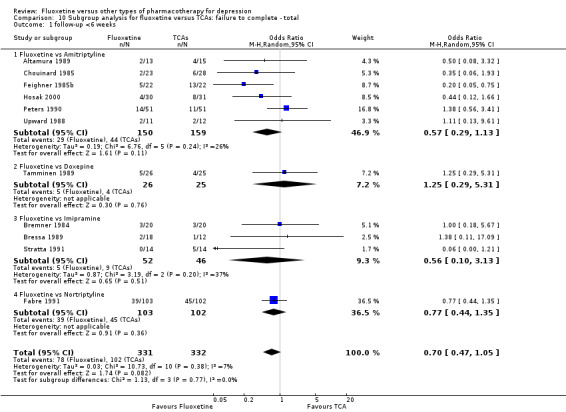

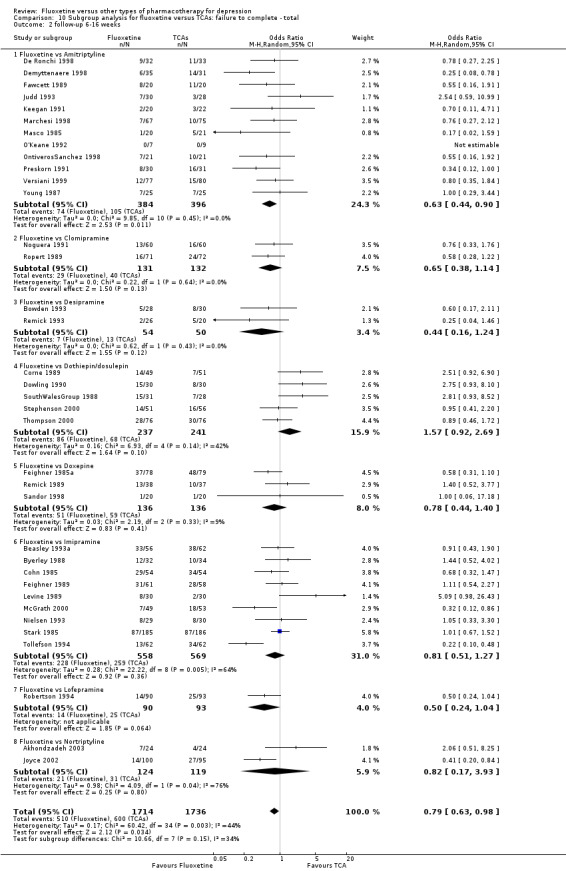

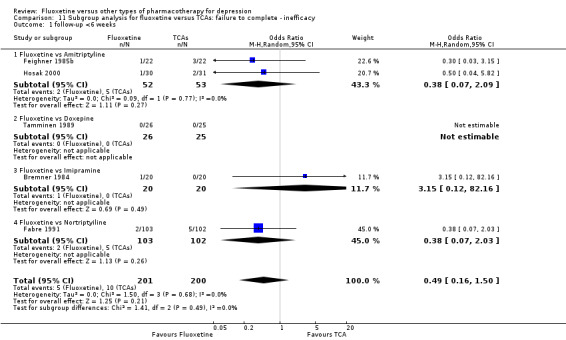

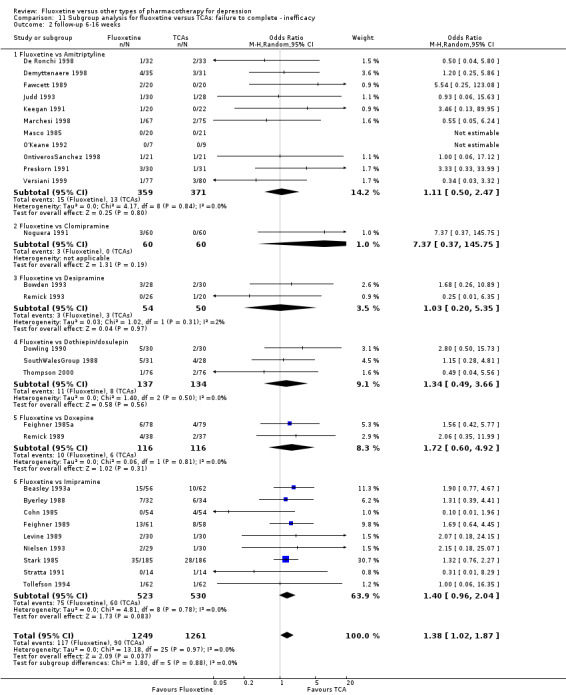

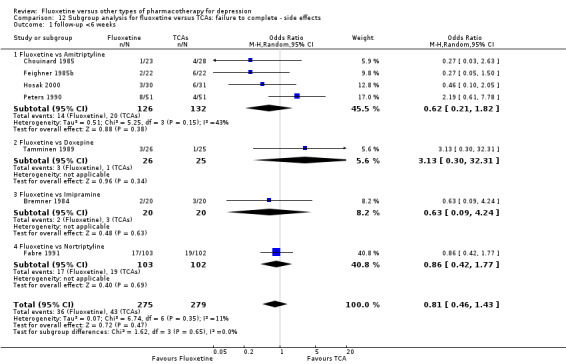

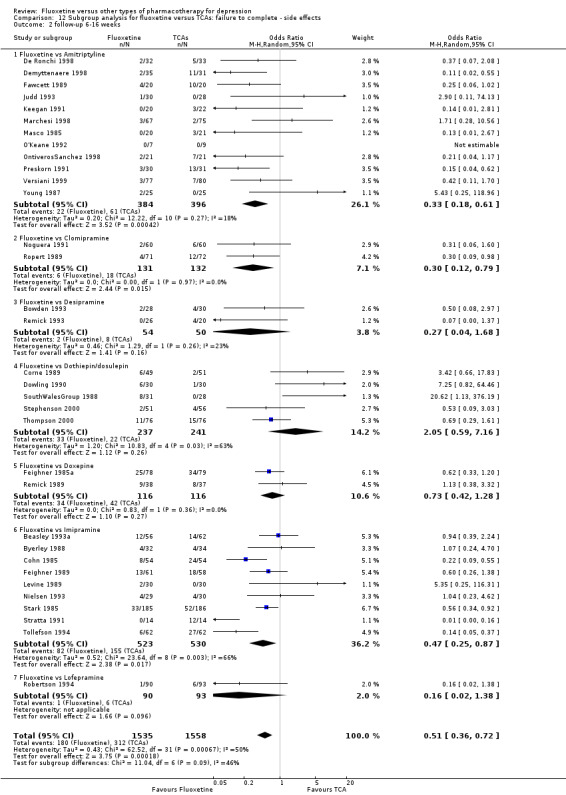

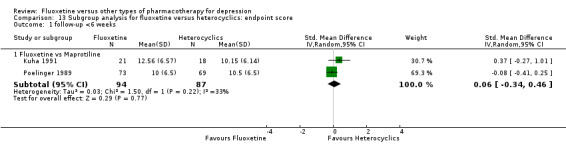

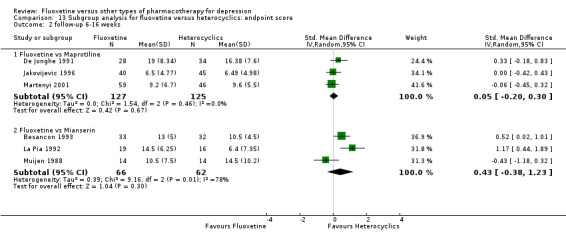

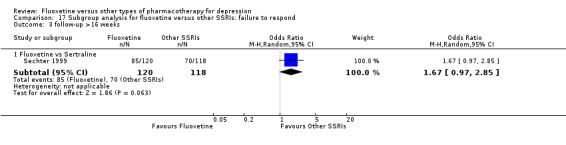

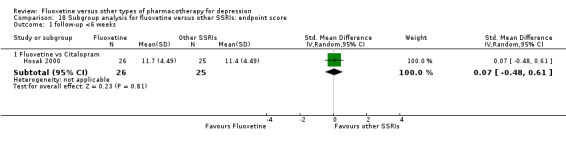

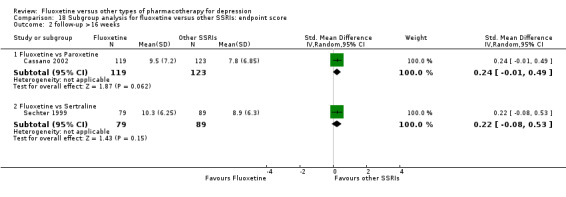

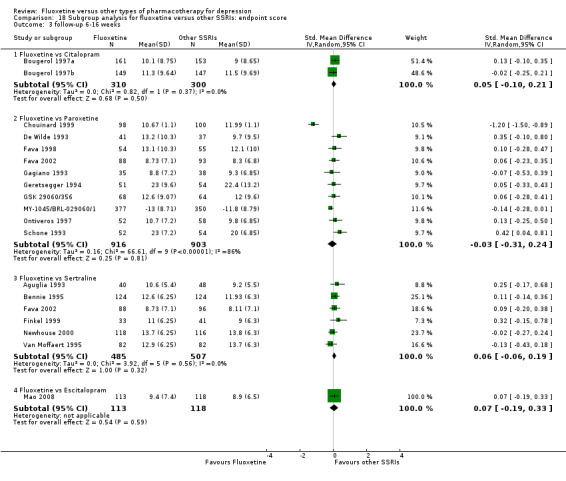

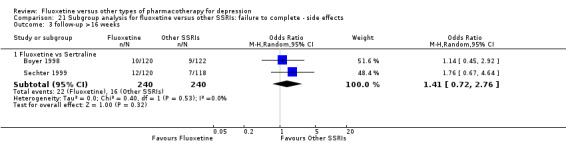

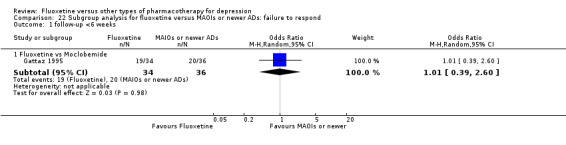

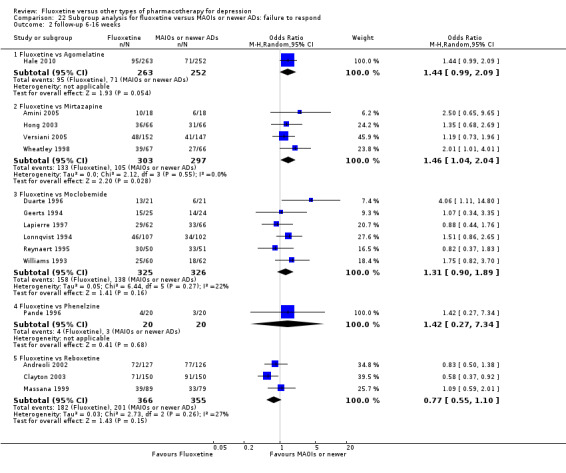

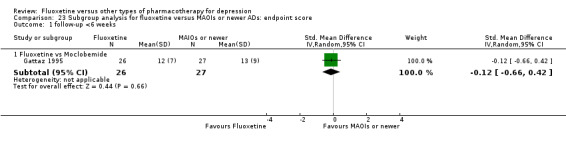

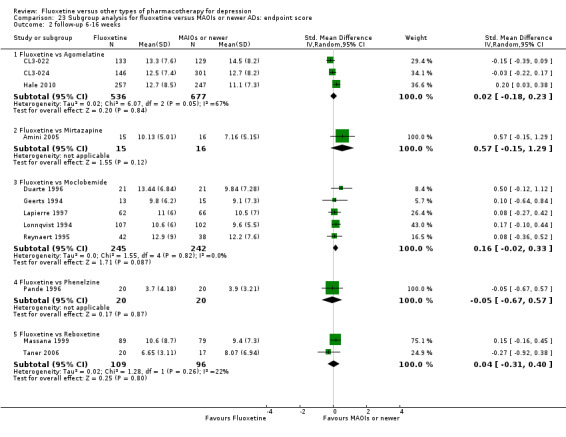

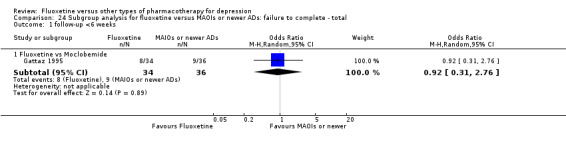

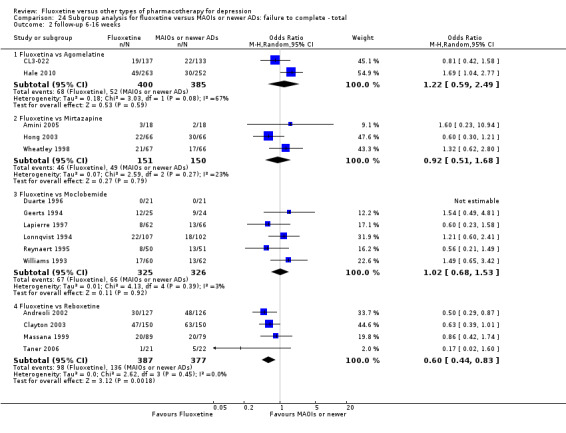

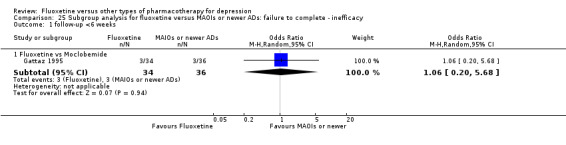

A total of 171 studies were included in the analysis (24,868 participants). The included studies were undertaken between 1984 and 2012. Studies had homogenous characteristics in terms of design, intervention and outcome measures. The assessment of quality with the risk of bias tool revealed that the great majority of them failed to report methodological details, like the method of random sequence generation, the allocation concealment and blinding. Moreover, most of the included studies were sponsored by drug companies, so the potential for overestimation of treatment effect due to sponsorship bias should be considered in interpreting the results. Fluoxetine was as effective as the TCAs when considered as a group both on a dichotomous outcome (reduction of at least 50% on the Hamilton Depression Scale) (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.22, 24 RCTs, 2124 participants) and a continuous outcome (mean scores at the end of the trial or change score on depression measures) (SMD 0.03, 95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.14, 50 RCTs, 3393 participants). On a dichotomous outcome, fluoxetine was less effective than dothiepin or dosulepin (OR 2.13, 95% CI 1.08 to 4.20; number needed to treat (NNT) = 6, 95% CI 3 to 50, 2 RCTs, 144 participants), sertraline (OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.74; NNT = 13, 95% CI 7 to 58, 6 RCTs, 1188 participants), mirtazapine (OR 1.46, 95% CI 1.04 to 2.04; NNT = 12, 95% CI 6 to 134, 4 RCTs, 600 participants) and venlafaxine (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.51; NNT = 11, 95% CI 8 to 16, 12 RCTs, 3387 participants). On a continuous outcome, fluoxetine was more effective than ABT‐200 (SMD ‐1.85, 95% CI ‐2.25 to ‐1.45, 1 RCT, 141 participants) and milnacipran (SMD ‐0.36, 95% CI ‐0.63 to ‐0.08, 2 RCTs, 213 participants); conversely, it was less effective than venlafaxine (SMD 0.10, 95% CI 0 to 0.19, 13 RCTs, 3097 participants). Fluoxetine was better tolerated than TCAs considered as a group (total dropout OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.96; NNT = 20, 95% CI 13 to 48, 49 RCTs, 4194 participants) and was better tolerated in comparison with individual ADs, in particular amitriptyline (total dropout OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.85; NNT = 13, 95% CI 8 to 39, 18 RCTs, 1089 participants), and among the newer ADs ABT‐200 (total dropout OR 0.18, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.39; NNT = 3, 95% CI 2 to 5, 1 RCT, 144 participants), pramipexole (total dropout OR 0.12, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.42, NNT = 3, 95% CI 2 to 5, 1 RCT, 105 participants), and reboxetine (total dropout OR 0.60, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.82, NNT = 9, 95% CI 6 to 24, 4 RCTs, 764 participants).

Authors' conclusions

The present study detected differences in terms of efficacy and tolerability between fluoxetine and certain ADs, but the clinical meaning of these differences is uncertain. Moreover, the assessment of quality with the risk of bias tool showed that the great majority of included studies failed to report details on methodological procedures. Of consequence, no definitive implications can be drawn from the studies' results. The better efficacy profile of sertraline and venlafaxine (and possibly other ADs) over fluoxetine may be clinically meaningful, as already suggested by other systematic reviews. In addition to efficacy data, treatment decisions should also be based on considerations of drug toxicity, patient acceptability and cost.

Keywords: Humans; Antidepressive Agents; Antidepressive Agents/therapeutic use; Antidepressive Agents, Second‐Generation; Antidepressive Agents, Second‐Generation/therapeutic use; Antidepressive Agents, Tricyclic; Antidepressive Agents, Tricyclic/therapeutic use; Depression; Depression/drug therapy; Fluoxetine; Fluoxetine/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors; Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Fluoxetine compared with other antidepressants for depression in adults

Depression is a severe mental illness characterised by a persistent low mood and loss of all interest and pleasure, usually accompanied by a range of symptoms such as appetite change, sleep disturbance and poor concentration. The predominant treatment options for depression are drugs and psychological therapies, but antidepressant drugs are the most common treatment for moderate to severe depression. Fluoxetine, one of the first new generation antidepressants, is an extremely popular drug treatment for depression. However, findings from studies comparing fluoxetine with other antidepressants are controversial. In this systematic review, the efficacy and tolerability of fluoxetine was compared with other antidepressants for the acute treatment of depression.

In May 2012 we searched, in a wide‐ranging way, for all the useful studies (randomised controlled trials, or RCTs) we could find which compared fluoxetine with any other antidepressant in treating people with depression. One hundred and seventy‐one RCTs were included, with 24,868 people in the analyses. Combining the results from all the trials, fluoxetine was similarly effective, but better tolerated, than older generation (tricyclic) antidepressants. In comparison with other new generation antidepressants, important differences in efficacy and in tolerability were found between fluoxetine and some of the antidepressants, for example, fluoxetine was less effective than sertraline and mirtazapine but better tolerated than reboxetine. These differences might have a clinical impact in everyday practice. However, when interpreting these differences it is important to bear in mind that the studies were short in duration (eight weeks or less) and that the average size of each trial was small (each included around 100 people). Moreover, most of the included studies were sponsored by drug companies, which could potentially have led to an overestimation of treatment effect. As a consequence, it is difficult to draw clear, clinically meaningful conclusions. More reliable information is needed about the respective safety profiles of antidepressants.

Summary of findings

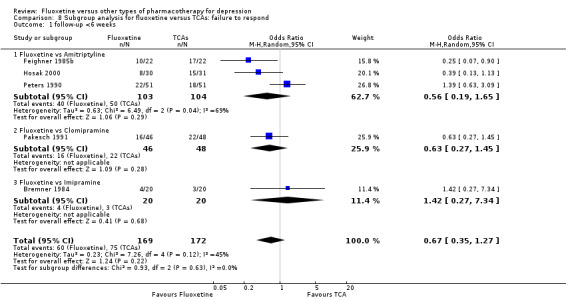

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Fluoxetine compared to TCAs.

| Fluoxetine compared to TCAs | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: TCAs | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| TCAs | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

471 per 1000 | 463 per 1000 (406 to 520) | OR 0.97 (0.77 to 1.22) | 2124 (24 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.03 higher (0.07 lower to 0.14 higher) | 3393 (50 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | This effect approaches zero | ||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 335 per 1000 | 284 per 1000 (246 to 326) | OR 0.79 (0.65 to 0.96) | 4194 (49 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 193 per 1000 | 116 per 1000 (87 to 152) | OR 0.55 (0.40 to 0.75) | 3647 (40 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 68 per 1000 | 87 per 1000 (66 to 112) | OR 1.29 (0.96 to 1.72) | 2911 (33 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in study design: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

Summary of findings 2. Fluoxetine compared to ABT‐200.

| Fluoxetine compared to ABT 200 | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: ABT 200 | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| ABT 200 | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | Not estimable | 0 (0) | |||

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 1.85 standard deviations lower (2.25 to 1.45 lower) | 141 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | This corresponds to a large effect according to conventions proposed by Cohen 1992. However, only one study contributed to this analysis | ||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 528 per 1000 | 167 per 1000 (82 to 304) | OR 0.18 (0.08 to 0.39) | 144 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

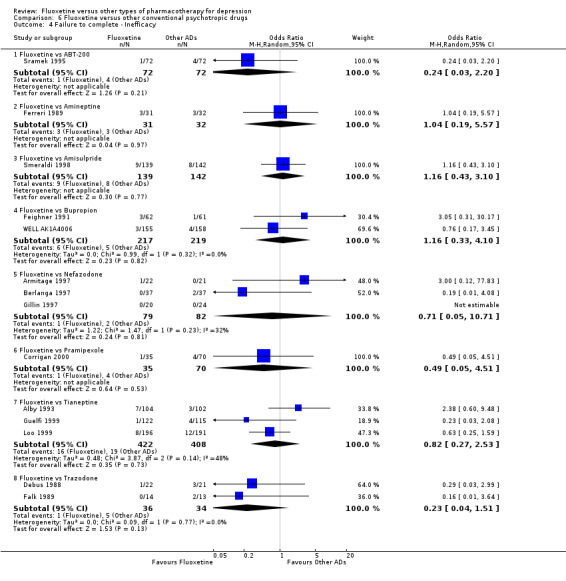

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 56 per 1000 | 14 per 1000 (2 to 115) | OR 0.24 (0.03 to 2.20) | 144 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

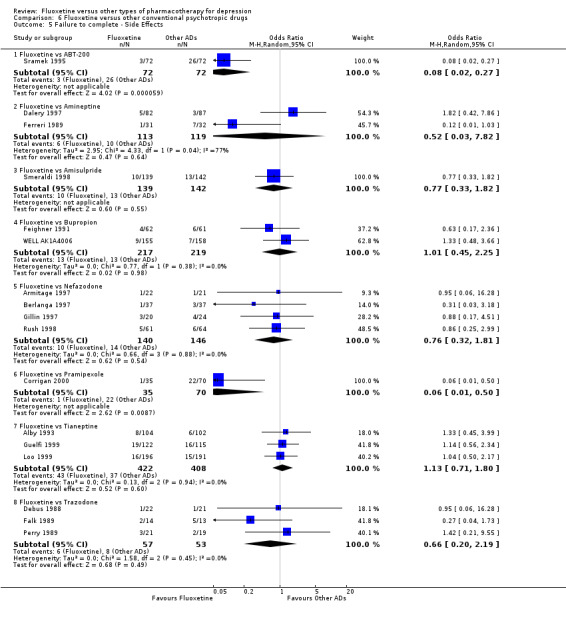

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 361 per 1000 | 43 per 1000 (11 to 132) | OR 0.08 (0.02 to 0.27) | 144 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in study design: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested. Only one study included in the analysis.

Summary of findings 3. Fluoxetine compared to agomelatine.

| Fluoxetine compared to agomelatine | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: agomelatine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Agomelatine | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

282 per 1000 | 361 per 1000 (280 to 450) | OR 1.44 (0.99 to 2.09) | 515 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.02 standard deviations higher (0.18 lower to 0.23 higher) | 1213 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | This effect approaches zero | ||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 135 per 1000 | 170 per 1000 (122 to 233) | OR 1.31 (0.89 to 1.94) | 785 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 55 per 1000 | 59 per 1000 (23 to 142) | OR 1.08 (0.41 to 2.88) | 785 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 34 per 1000 | 50 per 1000 (25 to 97) | OR 1.51 (0.74 to 3.07) | 785 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

2 Only one study included in this analysis.

Summary of findings 4. Fluoxetine compared to amineptine.

| Fluoxetine compared to amineptine | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: amineptine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Amineptine | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

719 per 1000 | 486 per 1000 (249 to 727) | OR 0.37 (0.13 to 1.04) | 63 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0 standard deviations higher (0 to 0 higher) | 0 (0) | No data available on this outcome | |||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 210 per 1000 | 140 per 1000 (43 to 370) | OR 0.61 (0.17 to 2.21) | 232 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 94 per 1000 | 97 per 1000 (19 to 366) | OR 1.04 (0.19 to 5.57) | 63 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ (Copy) | 84 per 1000 | 46 per 1000 (3 to 418) | OR 0.52 (0.03 to 7.82) | 232 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

Summary of findings 5. Fluoxetine compared to amisulpride.

| Fluoxetine compared to amisulpride | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: amisulpride | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Amisulpride | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | Not estimable | 0 (0) | |||

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.17 standard deviations higher (0.07 lower to 0.41 higher) | 268 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | This corresponds to a very small effect according to conventions proposed by Cohen 1992 | ||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 225 per 1000 | 288 per 1000 (191 to 409) | OR 1.39 (0.81 to 2.38) | 281 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 56 per 1000 | 65 per 1000 (25 to 156) | OR 1.16 (0.43 to 3.10) | 281 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 92 per 1000 | 72 per 1000 (32 to 155) | OR 0.77 (0.33 to 1.82) | 281 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested. Only one study included in the analysis.

Summary of findings 6. Fluoxetine compared to bupropion.

| Fluoxetine compared to bupropion | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: bupropion | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Bupropion | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

493 per 1000 | 447 per 1000 (318 to 582) | OR 0.83 (0.48 to 1.43) | 436 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0 standard deviations higher (0 to 0 higher) | 0 (0) | No data available on this outcome | |||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 356 per 1000 | 356 per 1000 (270 to 450) | OR 1.00 (0.67 to 1.48) | 436 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 23 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 87) | OR 1.16 (0.33 to 4.10) | 436 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 59 per 1000 | 60 per 1000 (28 to 124) | OR 1.01 (0.45 to 2.25) | 436 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

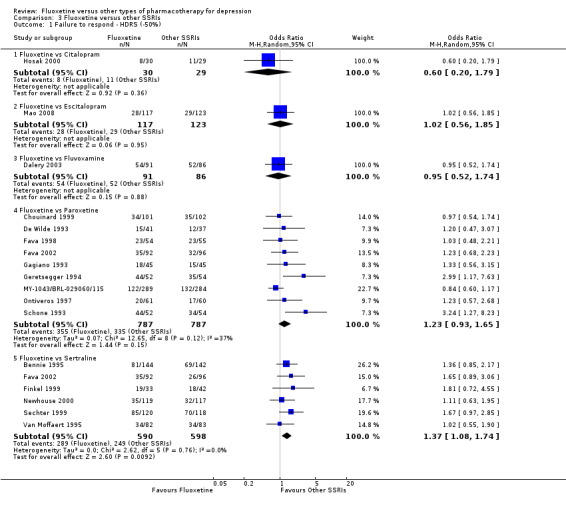

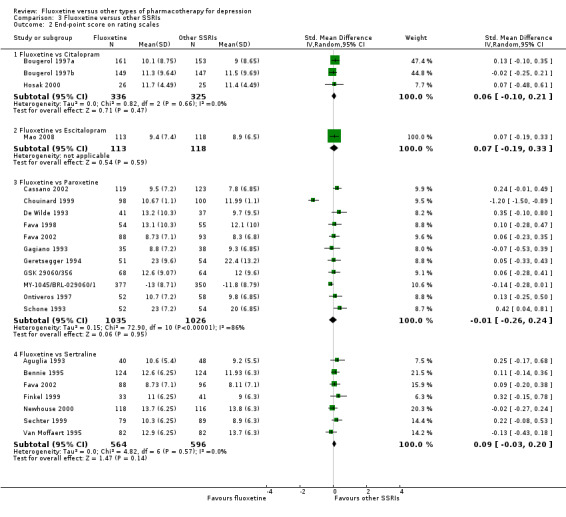

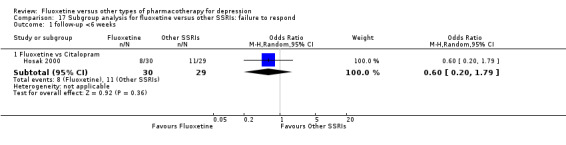

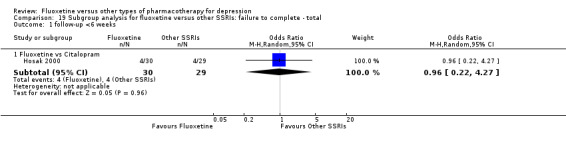

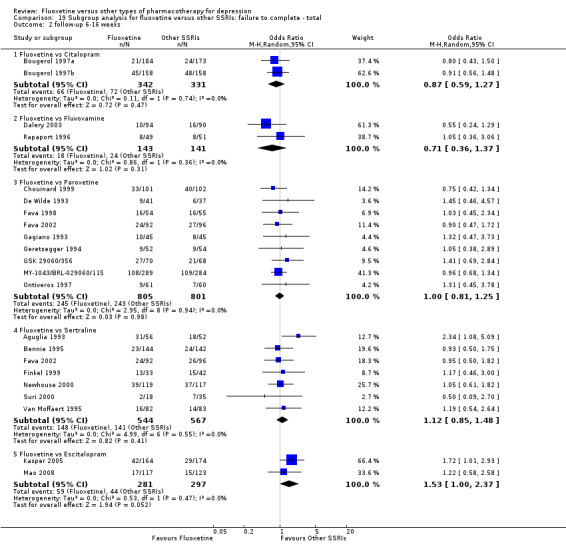

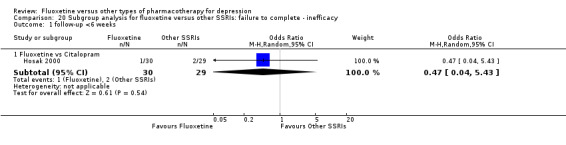

Summary of findings 7. Fluoxetine compared to citalopram.

| Fluoxetine compared to citalopram | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: citalopram | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Citalopram | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

379 per 1000 | 268 per 1000 (109 to 522) | OR 0.60 (0.20 to 1.79) | 59 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.06 standard deviations higher (0.10 lower to 0.21 higher) | 661 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | This effect approaches zero | ||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 211 per 1000 | 189 per 1000 (138 to 254) | OR 0.87 (0.60 to 1.27) | 732 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 75 per 1000 | 66 per 1000 (37 to 112) | OR 0.87 (0.48 to 1.56) | 732 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

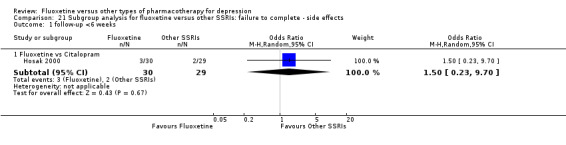

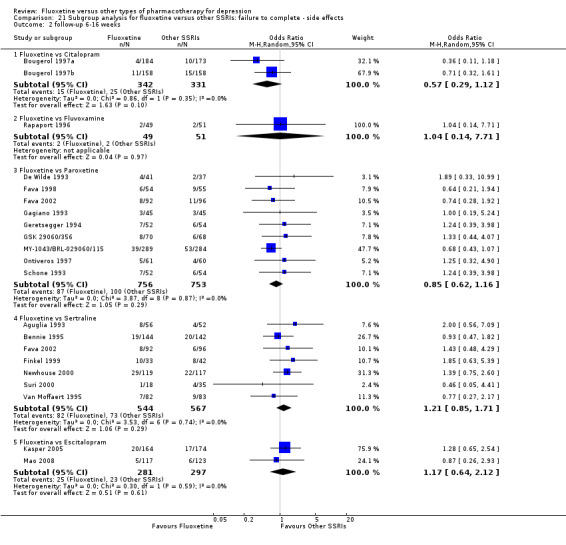

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 75 per 1000 | 49 per 1000 (27 to 89) | OR 0.64 (0.34 to 1.20) | 732 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

2 Only one study included in the analysis and less than 100 patients.

Summary of findings 8. Fluoxetine compared to Crocus sativus.

| Fluoxetine compared to Crocus sativus | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison:Crocus sativus | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Crocus sativus | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

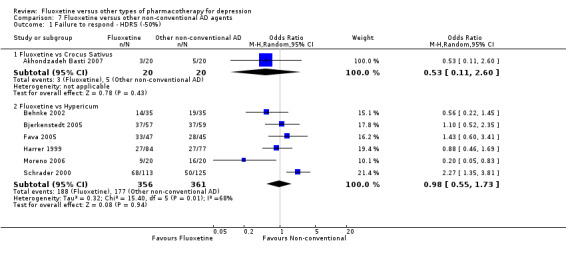

250 per 1000 | 150 per 1000 (35 to 464) | OR 0.53 (0.11 to 2.60) | 40 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0 standard deviations higher (0 to 0 higher) | 0 (0) | No data available on this outcome | |||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 50 per 1000 | 50 per 1000 (3 to 475) | OR 1.00 (0.06 to 17.18) | 40 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | Not estimable | 0 (0) | |||

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | Not estimable | 0 (0) | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested. Only one study included in the analysis and less than 50 patients.

Summary of findings 9. Fluoxetine compared to duloxetine.

| Fluoxetine compared to for duloxetine | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: duloxetine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Fluoxetine | ||||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

400 per 1000 | 485 per 1000 (289 to 684) | OR 1.41 (0.61 to 3.25) | 103 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0 standard deviations higher (0 to 0 higher) | 0 (0) | No data available on this outcome | |||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 281 per 1000 | 260 per 1000 (171 to 372) | OR 0.90 (0.53 to 1.52) | 532 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 15 per 1000 | 47 per 1000 (14 to 152) | OR 3.33 (0.93 to 12.11) | 432 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 66 per 1000 | 19 per 1000 (5 to 80) | OR 0.28 (0.07 to 1.23) | 532 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

2 Only one study included in the analysis.

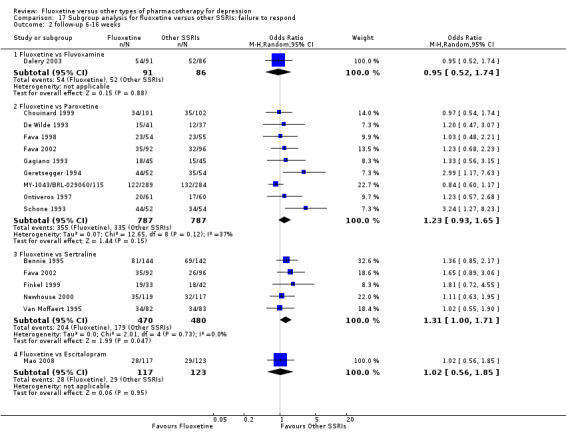

Summary of findings 10. Fluoxetine compared to escitalopram.

| Fluoxetine compared to escitalopram | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: escitalopram | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Escitalopram | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

236 per 1000 | 239 per 1000 (147 to 363) | OR 1.02 (0.56 to 1.85) | 240 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.07 standard deviations higher (0.19 lower to 0.33 higher) | 231 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | This effect approaches zero | ||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 148 per 1000 | 210 per 1000 (148 to 292) | OR 1.53 (1.00 to 2.37) | 578 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

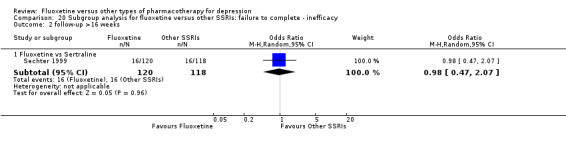

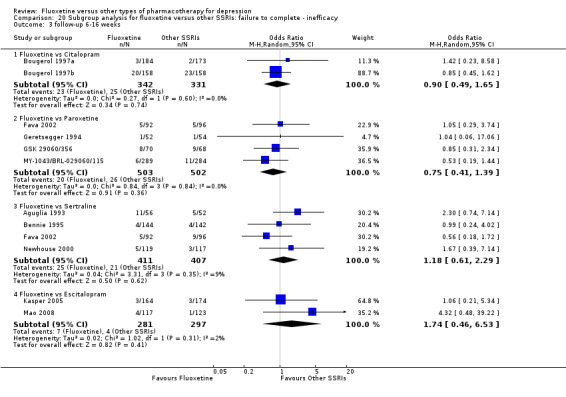

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 13 per 1000 | 23 per 1000 (6 to 82) | OR 1.74 (0.46 to 6.53) | 578 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 77 per 1000 | 89 per 1000 (51 to 151) | OR 1.17 (0.64 to 2.12) | 578 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

2 Only one study included in the analysis.

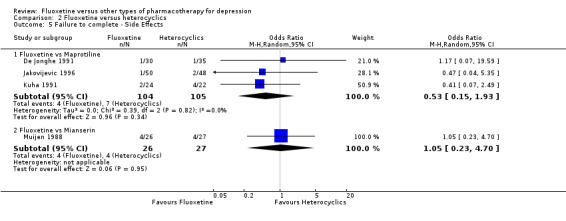

Summary of findings 11. Fluoxetine compared to fluvoxamine.

| Fluoxetine compared to fluvoxamine | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: fluvoxamine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Fluvoxamine | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

605 per 1000 | 592 per 1000 (443 to 727) | OR 0.95 (0.52 to 1.74) | 177 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0 standard deviations higher (0 to 0 higher) | 0 (0) | No data available on this outcome | |||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 170 per 1000 | 936 per 1000 (69 to 219) | OR 071 (0.36 to 1.37) | 284 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | Not estimable | 0 (0) | |||

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 39 per 1000 | 41 per 1000 (6 to 239) | OR 1.04 (0.14 to 7.71) | 100 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

2 Only one study included in the analysis.

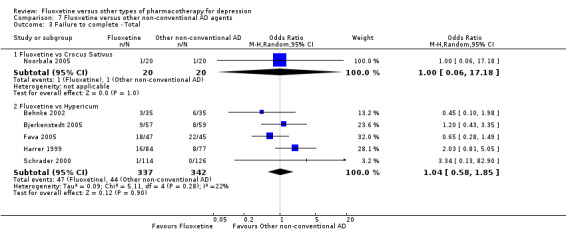

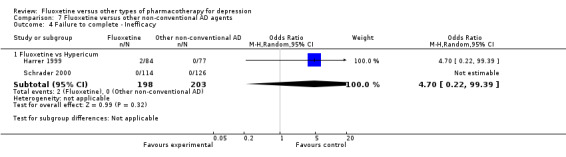

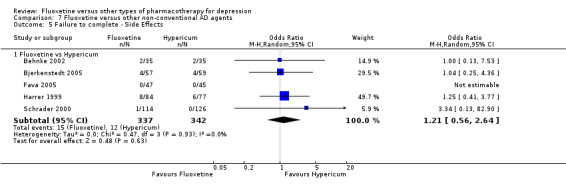

Summary of findings 12. Fluoxetine compared to hypericum.

| Fluoxetine compared to hypericum | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: hypericum | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Hypericum | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

490 per 1000 | 485 per 1000 (346 to 625) | OR 0.98 (0.55 to 1.73) | 717 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

|

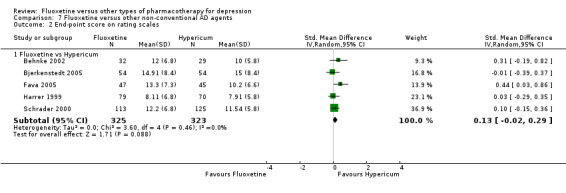

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.13 standard deviations higher (0.02 lower to 0.29 higher) | 648 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | This corresponds to a very small effect according to conventions proposed by Cohen 1992 | ||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 129 per 1000 | 133 per 1000 (88 to 189) | OR 1.04 (0.65 to 1. 68) | 679 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | OR 4.70 (0.22 to 99.39) | 401 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |||

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 35 per 1000 | 42 per 1000 (20 to 88) | OR 1.21 (0.56 to 2.64) | 679 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

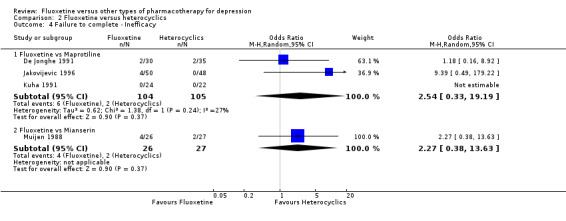

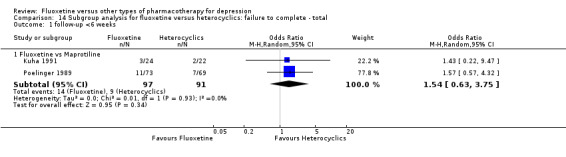

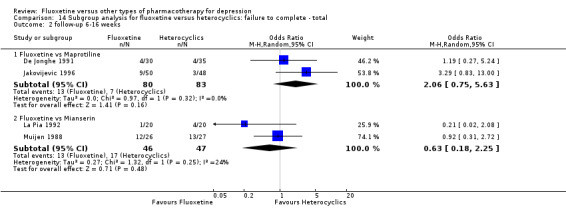

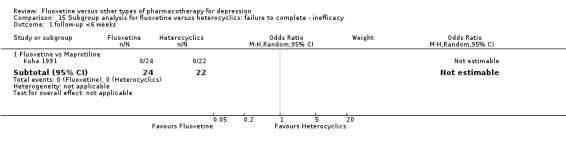

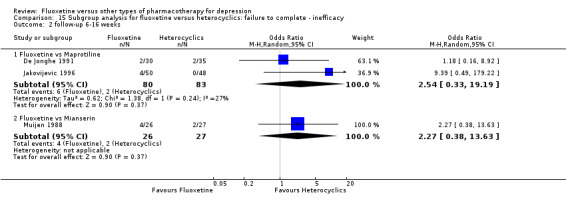

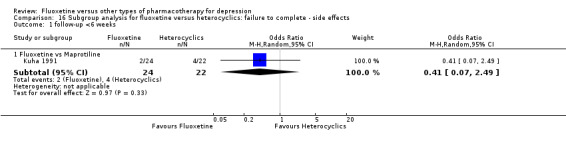

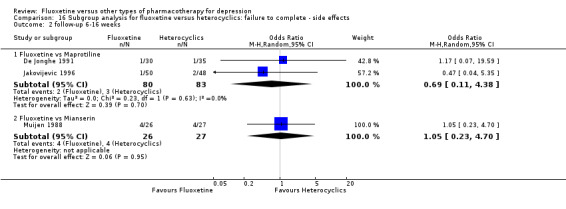

Summary of findings 13. Fluoxetine compared to maprotiline.

| Fluoxetine compared to maprotiline | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: maprotiline | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Maprotiline | Fluoxetine | |||||

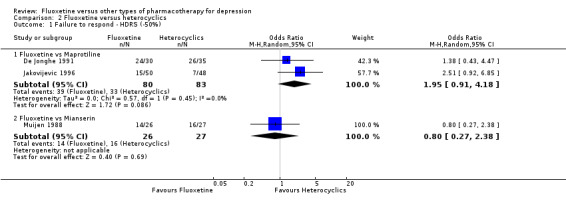

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

398 per 1000 | 563 per 1000 (984 to 734) | OR 1.95 (0.91 to 4.18) | 163 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | |

|

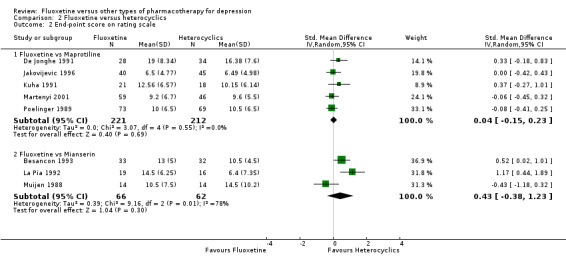

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.04 standard deviations higher (0.15 lower to 0.23 higher) | 433 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | This effect approaches zero | ||

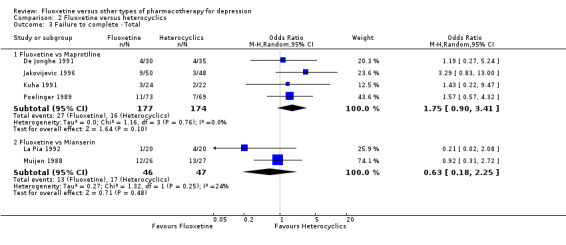

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 92 per 1000 | 151 per 1000 (84 to 257) | OR 1.75 (0.90 to 3.41) | 351 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 67 per 1000 | 36 per 1000 (11 to 121) | OR 0.53 (0.15 to 1.93) | 209 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 19 per 1000 | 47 per 1000 (6 to 279) | OR 2.54 (0.33 to 19.9) | 209 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

Summary of findings 14. Fluoxetine compared to mianserin.

| Fluoxetine compared to mianserin | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: mianserin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Mianserin | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

593 per 1000 | 538 per 1000 (282 to 776) | OR 0.80 (0.27 to 2.38) | 53 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.43 standard deviations higher (0.38 lower to 1.23 higher) | 128 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | This corresponds to a small effect according to conventions proposed by Cohen 1992 | ||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 362 per 1000 | 263 per 1000 (93 to 560) | OR 0.63 (0.18 to 2.25) | 93 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 74 per 1000 | 154 per 1000 (30 to 522) | OR 2.27 (0.38 to 13.63) | 53 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 148 per 1000 | 154 per 1000 (38 to 450) | OR 1.05 (0.23 to 4.70) | 53 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

2 Only one study included in the analysis and less than 100 patients.

Summary of findings 15. Fluoxetine compared to milnacipran.

| Fluoxetine compared to milnacipran | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: milnacipran | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Milnacipran | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

473 per 1000 | 518 per 1000 (412 to 623) | OR 1.20 (0.78 to 1.84) | 370 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.36 standard deviations lower (0.63 to 0.08 lower) | 213 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | This corresponds to a small effect according to conventions proposed by Cohen 1992 | ||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 411 per 1000 | 406 per 1000 (322 to 497) | OR 0.98 (0.68 to 1.42) | 560 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 137 per 1000 | 165 per 1000 (97 to 267) | OR 1.25 (0.68 to 2.30) | 560 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 71 per 1000 | 103 per 1000 (59 to 175) | OR 1.50 (0.81 to 2.76) | 560 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

Summary of findings 16. Fluoxetine compared to mirtazapine.

| Fluoxetine compared to mirtazapine | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: Fluoxetine Comparison: mirtazapine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Mirtazapine | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

354 per 1000 | 444 per 1000 (363 to 527) | OR 1.46 (1.04 to 2.04) | 600 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.57 standard deviations higher (0.15 lower to 1.29 higher) | 31 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | This corresponds to a medium effect according to conventions proposed by Cohen 1992 | ||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 327 per 1000 | 304 per 1000 (211 to 416) | OR 0.90 (0.55 to 1.47) | 301 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

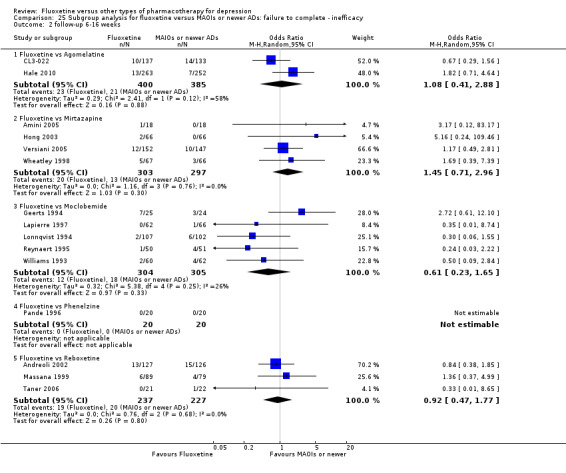

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 44 per 1000 | 62 per 1000 (31 to 119) | OR 1.45 (0.71 to 2.96) | 600 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

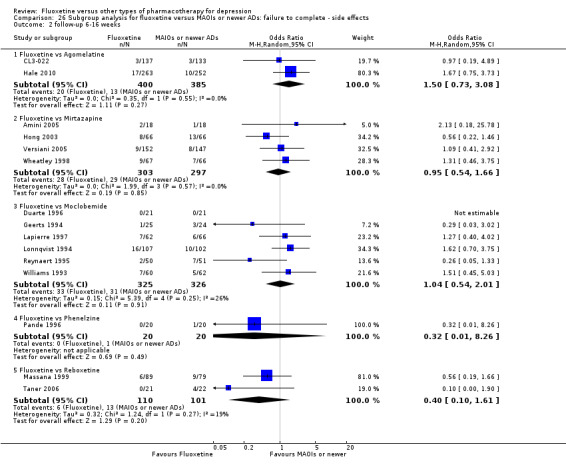

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 98 per 1000 | 93 per 1000 (56 to 151) | OR 0.95 (0.55 to 1.64) | 600 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

2 Only one study included in the analysis and less than 100 patients.

Summary of findings 17. Fluoxetine compared to moclobemide.

| Fluoxetine compared to moclobemide | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: moclobemide | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Moclobemide | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

436 per 1000 | 496 per 1000 (416 to 575) | OR 1.27 (0.92 to 1.75) | 721 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.13 standard deviations higher (0.04 lower to 0.30 higher) | 540 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | This corresponds to a very small effect according to conventions proposed by Cohen 1992 | ||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 207 per 1000 | 209 per 1000 (155 to 275) | OR 1.01 (0.70 to 1.45) | 721 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 62 per 1000 | 44 per 1000 (21 to 93) | OR 0.70 (0.32 to 1.56) | 679 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 86 per 1000 | 91 per 1000 (57 to 144) | OR 1.07 (0.64 to 1.80) | 721 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

Summary of findings 18. Fluoxetine compared to nefazodone.

| Fluoxetine compared to nefazodone | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: nefazodone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Nefazodone | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | Not estimable | 0 (0) | |||

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.06 standard deviations lower (0.30 lower to 0.18 higher) | 271 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | This effects approaches zero | ||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 220 per 1000 | 132 per 1000 (58 to 269) | OR 0.54 (0.22 to 1.31) | 161 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 24 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 (1 to 211) | OR 0.71 (0.05 to 10.71) | 161 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 96 per 1000 | 75 per 1000 (33 to 161) | OR 0.76 (0.32 to 1.81) | 286 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

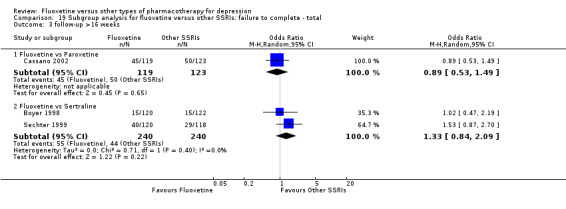

Summary of findings 19. Fluoxetine compared to paroxetine.

| Fluoxetine compared to paroxetine | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: paroxetine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Paroxetine | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

426 per 1000 | 477 per 1000 (408 to 550) | OR 1.23 (0.93 to 1.65) | 1574 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.01 standard deviations lower (0.25 lower to 0.24 higher) | 2061 (11 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | This effect approaches zero | ||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 317 per 1000 | 313 per 1000 (273 to 358) | OR 0.98 (0.81 to 1.20) | 1848 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 52 per 1000 | 39 per 1000 (22 to 71) | OR 0.75 (0.41 to 1.39) | 1005 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 133 per 1000 | 115 per 1000 (87 to 151) | OR 0.85 (0.62 to 1.16) | 1509 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

Summary of findings 20. Fluoxetine compared to phenelzine.

| Fluoxetine compared to phenelzine | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: phenelzine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Phenelzine | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

150 per 1000 | 200 per 1000 (45 to 564) | OR 1.42 (0.27 to 7.34) | 40 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.05 standard deviations lower (0.67 lower to 0.57 higher) | 40 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | This effect approaches zero | ||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 100 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (1 to 308) | OR 0.18 (0.01 to 4.01) | 40 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | Not estimable | 0 (0) | |||

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 50 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 (1 to 303) | OR 0.32 (0.01 to 8.26) | 40 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested. Only one study included in the analysis and less than 50 patients.

Summary of findings 21. Fluoxetine compared to pramipexole.

| Fluoxetine compared to pramipexole | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: pramipexole | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Pramipexole | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

657 per 1000 | 513 per 1000 (315 to 707) | OR 0.55 (0.24 to 1.26) | 105 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0 standard deviations higher (0 to 0 higher) | 0 (0) | No data available on this outcome | |||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 443 per 1000 | 87 per 1000 (23 to 250) | OR 0.12 (0.03 to 0.42) | 105 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 57 per 1000 | 29 per 1000 (3 to 215) | OR 0.49 (0.05 to 4.51) | 105 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 314 per 1000 | 27 per 1000 (5 to 186) | OR 0.06 (0.01 to 0.50) | 105 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested. Only one study included in the analysis.

Summary of findings 22. Fluoxetine compared to reboxetine.

| Fluoxetine compared to reboxetine | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: reboxetine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Reboxetine | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

566 per 1000 | 501 per 1000 (418 to 589) | OR 0.77 (0.55 to 1.10) | 721 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.04 standard deviations higher (0.31 lower to 0.40 higher) | 205 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | This effect approaches zero | ||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 361 per 1000 | 253 per 1000 (199 to 316) | OR 0.60 (0.44 to 0.82) | 764 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 88 per 1000 | 82 per 1000 (43 to 146) | OR 0.92 (0.47 to 1.77) | 464 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 129 per 1000 | 57 per 1000 (22 to 139) | OR 0.41 (0.15 to 1.09) | 211 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

Summary of findings 23. Fluoxetine compared to sertraline.

| Fluoxetine compared to sertraline | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: sertraline | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Sertraline | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

416 per 1000 | 494 per 1000 (435 to 554) | OR 1.37 (1.08 to 1.74) | 1188 (6 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.09 standard deviations higher (0.03 lower to 0.20 higher) | 1160 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | This corresponds to a very small effect according to conventions proposed by Cohen 1992 | ||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 229 per 1000 | 258 per 1000 (217 to 307) | OR 1.17 (0.93 to 1.49) | 1591 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 70 per 1000 | 76 per 1000 (49 to 118) | OR 1.09 (0.68 to 1.77) | 1056 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 110 per 1000 | 134 per 1000 (102 to 174) | OR 1.25 (0.92 to 1.70) | 1591 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

Summary of findings 24. Fluoxetine compared to tianeptine.

| Fluoxetine compared to tianeptine | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: tianeptine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Tianeptine | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

534 per 1000 | 562 per 1000 (462 to 657) | OR 1.12 (0.75 to 1.67) | 387 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.15 standard deviations lower (0.40 lower to 0.10 higher) | 730 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | This corresponds to a very small effect according to conventions proposed by Cohen 1992 | ||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 225 per 1000 | 218 per 1000 (167 to 279) | OR 0.96 (0.69 to 1.33) | 830 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 47 per 1000 | 39 per 1000 (13 to 110) | OR 0.82 (0.27 to 2.53) | 830 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 91 per 1000 | 101 per 1000 (66 to 152) | OR 1.13 (0.71 to 1.80) | 830 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

Summary of findings 25. Fluoxetine compared to trazodone.

| Fluoxetine compared to trazodone | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: trazodone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Trazodone | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

642 per 1000 | 467 per 1000 (189 to 769) | OR 0.49 (0.13 to 1.86) | 110 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.25 standard deviations lower (0.76 lower to 0.26 higher) | 203 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | This corresponds to a small effect according to conventions proposed by Cohen 1992 | ||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 250 per 1000 | 145 per 1000 (71 to 274) | OR 0.51 (0.23 to 1.13) | 230 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 147 per 1000 | 38 per 1000 (7 to 207) | OR 0.23 (0.04 to 1.51) | 70 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 151 per 1000 | 105 per 1000 (34 to 280) | OR 0.66 (0.20 to 2.19) | 110 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

Summary of findings 26. Fluoxetine compared to venlafaxine.

| Fluoxetine compared to venlafaxine | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: fluoxetine Comparison: venlafaxine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Venlafaxine | Fluoxetine | |||||

|

Failure to respond (reduction ≥ 50% on HDRS) |

341 per 1000 | 400 per 1000 (363 to 439) | OR 1.29 (1.10 to 1.51) | 3387 (12 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

|

Endpoint score (HDRS or MADRS) |

The mean endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.10 standard deviations higher (0.0 to 0.19 higher) | 3097 (13 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | This corresponds to a very small effect according to conventions proposed by Cohen 1992 | ||

| Failure to complete ‐ total ‐ | 256 per 1000 | 234 per 1000 (203 to 267) | OR 0.89 (0.74 to 1.06) | 2683 (14 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ inefficacy ‐ | 43 per 1000 | 56 per 1000 (40 to 79) | OR 1.31 (0.91 to 1.89) | 2640 (13 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Failure to complete ‐ side effects ‐ | 116 per 1000 | 87 per 1000 (69 to 110) | OR 0.72 (0.56 to 0.94) | 2640 (13 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations in studies designs: no details on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment. Blinding stated but not tested.

Background

Description of the condition

Major depression is generally diagnosed when a persistent and unreactive low mood or loss of interest and pleasure, or both, are accompanied by a range of symptoms including appetite loss, insomnia, fatigue, loss of energy, poor concentration, psychomotor symptoms, inappropriate guilt and morbid thoughts of death (APA 1994). It was the third leading cause of burden among all diseases in the year 2004 and it is expected to be the greatest cause in 2030 (WHO 2006). This condition is associated with marked personal, social and economic morbidity, loss of functioning and productivity, and creates significant demands on service providers in terms of workload (APA 2000; NICE 2010). Although pharmacological and psychological interventions are both effective for major depression, in primary and secondary care settings antidepressant (AD) drugs remain the mainstay of treatment in moderate to severe major depression (APA 2006; NICE 2010). Amongst ADs many different agents are available, including tricyclics (TCAs); monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs); selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs); serotonin‐noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) such as venlafaxine, duloxetine and milnacipran; and other agents (mirtazapine, reboxetine, bupropion). Over the last 20 years prescribing ADs has dramatically risen in Western countries, mainly because of the increasing number of prescriptions for SSRIs, which have progressively become the most commonly prescribed ADs (Ciuna 2004). The selective action of SSRIs is purported to be the rationale for potential advantages over other existing therapies. Rather than a breakthrough in pharmacology, the development of SSRIs may be seen as a process of refining the action of existing and commonly used alternatives and this process may be clinically important (Freemantle 2000). SSRIs are generally more acceptable than TCAs, and there is evidence of similar efficacy (NICE 2010). However, head‐to‐head comparisons have provided contrasting findings (Cipriani 2006a).

Description of the intervention

Fluoxetine hydrochloride (3‐(p‐trifluoromethylphenoxy)‐N‐methyl‐3‐phenylpropylamine HCl; Lilly (LY) 110140) was first described in a scientific journal in 1974 as a selective serotonin (5‐hydroxytryptamine or 5‐HT)‐uptake inhibitor (Wong 2005). It was marketed as an AD in December 1987 and went off patent in August 2001. From its marketing fluoxetine quickly became the most prescribed AD in the United States (Marshall 2009) and, despite the availability of newer agents, it remains extremely popular in the pharmacological treatment of major depression and in the treatment of several anxiety disorders.

How the intervention might work

Fluoxetine’s presumed mechanism of action is through inhibiting the reuptake of serotonin. It is not clear, however, if reuptake inhibition correlates with clinical effect, either between patients or over time.

The bioavailability of fluoxetine is relatively high, and peak plasma concentrations are reached in six to eight hours. It is highly bound to plasma proteins, mostly albumin. Fluoxetine is metabolised in the liver by isoenzymes of the cytochrome P450 system, including CYP2D6. Only one metabolite of fluoxetine, norfluoxetine (N‐demethylated fluoxetine), is biologically active. The extremely slow elimination of fluoxetine and its active metabolite norfluoxetine from the body distinguishes it from other ADs. With time, fluoxetine and norfluoxetine inhibit their own metabolism so the fluoxetine elimination half‐life changes from one to three days after a single dose to four to six days after long‐term use.

Why it is important to do this review

In 2000 Geddes and colleagues (Geddes 2000) completed a Cochrane systematic review comparing the group of SSRIs with all other ADs and concluded that there were no large differences between the AD drug classes; however it was suggested that differences may emerge when single, head‐to‐head drug comparisons were considered. Starting from this consideration, and with the aim to shed light on the field of AD trials and treatment of major depression, a group of researchers agreed to join forces under the rubric of the Meta‐Analyses of New Generation Antidepressants Study Group (MANGA Study Group) to systematically review all available evidence for each specific newer AD. We have up to now completed individual reviews on sertraline (Cipriani 2009a), escitalopram (Cipriani 2009b), milnacipran (Nagakawa 2009), fluvoxamine (Omori 2010), mirtazapine (Watanabe 2011), duloxetine (Cipriani 2012a) and citalopram (Cipriani 2012b), and a number of other reviews are now underway. A systematic review comparing fluoxetine with TCAs, heterocyclics, MAOIs, SSRIs, SNRIs and other antidepressants was first published in 2005 (Cipriani 2005) but since then new randomised evidence has been produced. We therefore sought to update that review with the aim of providing the ‘best available’ and most up‐to‐date evidence on the efficacy and acceptability of fluoxetine in individuals with unipolar major depression.

Objectives

To assess the effects of fluoxetine in comparison with all other antidepressive agents for depression in adult individuals with unipolar major depressive disorder. Specifically:

To determine the efficacy of fluoxetine in comparison with other ADs in alleviating the acute symptoms of unipolar major depressive disorder in adults; and

Review the acceptability of treatment with fluoxetine in comparison with other ADs.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing fluoxetine with all other active ADs as monotherapy in the acute phase treatment of unipolar depression were included. We included RCTs with a cross‐over design but only used the results from the first randomisation period.

We excluded quasi‐randomised trials, such as those allocating participants by using alternate days of the week.

Types of participants

The review included participants 18 years or older, of both sexes, with a primary diagnosis of unipolar major depression according to standardised criteria, DSM‐III, DSM‐III‐R, DSM‐IV (APA 2000), ICD‐10 (WHO 1992), Feighner criteria (Feighner 1972) or Research Diagnostic Criteria (Spitzer 1972). Studies using ICD‐9 were excluded as it only lists disease names and does not have diagnostic criteria.

We included participants with the following subtypes of depression: chronic, with catatonic features, with melancholic features, with atypical features, with postpartum onset, and with a seasonal pattern. We included studies in which up to 20% of participants presented with depressive episodes in bipolar affective disorder. We also included participants with a concurrent secondary diagnosis of another psychiatric disorder.

We excluded participants with a concurrent primary diagnosis of Axis I or II disorders and participants with a serious concomitant medical illness.

Types of interventions

We examined fluoxetine in comparison with conventional pharmacological treatments for acute depression. We also examined fluoxetine in comparison with non‐conventional ADs (hypericum or other non‐conventional ADs). We excluded trials in which fluoxetine was compared to another type of psychopharmacological agent (that is anxiolytics, anticonvulsants, antipsychotics or mood‐stabilisers) and trials in which fluoxetine was used as an augmentation strategy.

Experimental intervention

Fluoxetine (as monotherapy). No restrictions on dose, frequency, intensity and duration were applied.

Comparator interventions

Conventional antidepressive agents:

tricyclics (TCAs);

heterocyclics;

SSRIs;

SNRIs;

MAOIs or newer ADs; and

other conventional psychotropic drugs.

Non‐conventional antidepressive agents:

hypericum; and

other non‐conventional antidepressive agents (e.g. Crocus sativus).

No restrictions on dose, frequency, intensity and duration were applied.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Efficacy

Efficacy was evaluated using the following outcome measures.

(1) Dichotomous outcome

Number of participants who responded to treatment at the end of the trial by showing a reduction of at least 50% on the Hamilton Depression Scale (HDRS) (Hamilton 1960) out of the total number of randomised participants (intention‐to‐treat analysis).

(2) Continuous outcome

Group mean scores at the end of the trial or change scores on HDRS, or Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery 1979), or any other depression scale. If both endpoint and change scores were available, we considered endpoint scores.