Abstract

Animal models have been extensively used as a gold standard in various biological research, including immunological studies. Despite high availability and ease of handling procedure, they inadequately represent complex interactions and unique cellular properties in humans due to inter-species genetic and microenvironmental differences which have resulted in clinical-stage failures. Organoid technology has gained enormous attention as they provide sophisticated insights about tissue architecture and functionality in miniaturized organs. In this review, we describe the use of organoid system to overcome limitations in animal-based investigations, such as physiological mismatch with humans, costly, time-consuming, and low throughput screening. Immune organoids are one of the specific advancements in organogenesis ex vivo, which can reflect human adaptive immunity with more physiologically relevant aspects. We discuss how immune organoids are established from patient-derived lymphoid tissues, as well as their characteristics and functional features to understand immune mechanisms and responses. Also, some bioengineering perspectives are considered for any potential progress of immuno-engineered organoids.

Keywords: Lymphoid organ, Organoids, Human adaptive immune system, In vitro immune model

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

This work summarized the development and progress of human immune organoid generation.

-

•

Immune organoid is useful as an in vitro modelling of human adaptive immune system.

-

•

Immune organoid readouts are necessary to investigate their physiological and morphological properties.

-

•

Challenges and bioengineering solutions to improve immune organoid research are discussed comprehensively.

1. Introduction

Our knowledge of the immune system is underpinned by two major discoveries in the nineteenth century. First, the identification of phagocytes and their mechanism toward pathogens by Elie Metchnikoff in 1882 which became the basis for innate immune system [1]. The second was established by Emil Von Behring and Shibasabura Kitasato in 1890, who discovered that antibodies are capable of neutralizing microbial toxins neutralization which became the basis of acquired immunity [2]. Moreover, T lymphocyte was discovered by Jacques Miller by the 1950s throughout his study on the role of thymus development for acquired immune response [3]. Immunological research has since progressed tremendously over the years and with rapid development in sequencing methods, it is now a cutting-edge discipline to address multiple human diseases including cancer, diabetes, and autoimmune disorders (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis and lupus) which have all been found to be affected by a dysfunctional immune state.

It is a well-known fact that a variety of ailments is associated with the breakdown of immune functions. Cancer ranks as the leading cause of death worldwide and it is correlated with an impaired immune system that increases the risk of malignancy [4,5]. The hallmark of cancer is a systemic and prolonged inflammation that significantly alters the systemic immune landscape during tumour progression. An aberrant innate and adaptive immune responses are responsible for tumorigenesis by selecting aggressive clones, triggering immunosuppression, and promoting cancer cell growth and metastasis [4]. Over the last decade, immunotherapy has revolutionized the toolkit against cancer by targeting the immune system, such as immunomodulation with immune checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., anti-PD1, anti-PDL1, and anti-CTLA4) that provide durable remissions or infusion of autologous tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells to eradicate aggressive lymphomas [6].

In the past three years, the rapid spread of the coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) is another example on the importance of understanding how our immunity deals with infectious agents. Cumulative mutations at viral receptor-binding domain reduce the effectiveness of existing vaccines against new variants. The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 immune escape necessitates multidisciplinary researchers to design strategies such as next-generation vaccine or antibody therapy that targets vulnerable sites unaffected by the mutations on the virus [7]. The impact of environmental and host factors such as pollution and aging (immunosenescence) have also attracted attention to study how these factors affect human immunity [8,9].

Our immune system is the first and foremost multicellular networks which collectively defend the body against infection or biological threats [10]. Understanding the human immune functions is critical to protect lives, and increase disease diagnostics and therapeutic effectiveness. Yet, it is challenging to do so due to the complexity, high inter-individual variability, and poor accessibility to primary immune tissues. Most preclinical studies on immune response rely on animal models (e.g., inbred mouse). Although immunocompetent mice can recapitulate human immune responses through in vivo studies, they involve caveats that should be seriously considered in experiments (e.g., unavoidable inter-species genomic and immune phenotypes differences, cost, and time-consuming). In addition, imprecise immune response patterns of animal models is one of the major reasons for low success rates of clinical trials, which further affects the rising costs ranging from 314 million to 2.8 billion dollars for a new therapy or drug development [11].

The use of humanized mice such as to evaluate immune checkpoint inhibitors and CAR-T therapy overcomes some of the aforementioned challenges [12,13]. Humanized mice also has been proven to model vector-borne disease or viral infection, i.e., the development of C3-deficient NOG mice to retain human red blood cells (RBCs) for mimicking the life cycle of malaria parasites, and plethora of humanized mouse models to understand the pathogenesis and sustainability of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) [14,15]. However, it still has some limitations including low similarity towards human immune system of <50 %, the need for invasive surgical procedures to transplant human cells (e.g., hematopoietic stem cells) or organs (e.g., fetal liver or thymus) into mice, the absence of primary immune responses, no multilineage haematopoiesis, no human leukocyte antigen (HLA) restriction, and possibility of developmental failure i.e., graft versus host disease [16,17]. To facilitate translational immunological research, it is paramount to substitute animal experiments with a highly accessible, robust, and cost-effective model.

Recent progress in biomimetic microengineering offers excellent constructs, called organ-on-a-chip, to mimic human physiological responses at the organ or tissue levels with an in vitro model. It is generally built from major functional cells residing in the organ to recapitulate key aspects of human physiology, and while this is a reductionist model, it has helped to offer insights such as deciphering biological mechanisms, drug discovery and toxicity testing and for preclinical testing [18,19]. There have also been several highly successful start-up companies (e.g., Emulate, Mimetas, 4Dcell, Hesperos) translating organ-on-a-chip prototypes into commercial products. Immune-system-on-a-chip typically comprises a multiorgan system and circulating immune cells to recapitulate immunosurveillance process [20], a tumour-on-a-chip platform to evaluate cancer-immune system crosstalk in correlation with immunotherapy efficacy [[21], [22], [23]], a microfluidic device supporting lymphoid follicle (LF) assembly for vaccine and adjuvant testing [24]. While these systems have advantages over animal models, it is important to acknowledge their limitations because immune system-on-a-chip cannot fully recapitulate native multicellular architecture and topography of an immune organ, and is unable to capture the deep intricacies of the human adaptive immunity. The absence of 3D tissue microarchitectural complexity, limited cell diversity, restricted circulatory system, and the lack of standardization and scalability of organ-on-a-chip, can limit their use as translational models [[25], [26], [27]].

Organoid technology is a powerful method to recapitulate the characteristics of human physiological organs alongside their mechanisms for tissue regeneration and development [28,29]. Organoids are three-dimensional (3D) multicellular self-organised tissues that mimic the architecture, functions, and complexities of their corresponding in vivo organs [30,31]. In the last decade, immune organoids have been established for immunological studies [[32], [33], [34], [35]]. They are primarily derived from lymphoid tissues including thymus, spleen, tonsil, and lymph nodes that is consequently advantageous to producing relevant ex vivo models [34,[36], [37], [38]]. Of note, lymphoid organoids can potentially address limitations of animal models to advance human immunology research. As an example, tonsil organoids generated from discarded tonsil tissues during tonsillectomy are capable of replicating properties of the germinal centres including somatic hypermutation, antigen-specific antibody production, affinity maturation, and class-switching [35]. This is a breakthrough technology to create a physiologically relevant model of the human adaptive immune system that could tackle some limitations from other clinical approaches (Fig. 1). Notwithstanding, research trends in immune organoids have advanced rapidly such as generating immune organoids from different lymphoid organs to build the complex human immunity, assembloids consisting of immune organoids with cancer organoids, and employing genetic and biological engineering techniques to create a more physiologically-relevant model by inducing endothelial cell formation or controlling organoid morphology [[39], [40], [41], [42]].

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration representing the human lymphatic organ modelling studies and the pros and cons between each model, including the in vivo animal testing, organ-on-a-chip system, precision cut tissue slice (PCTS), and organoid culture.

This review begins with a brief overview of major lymphoid organs including thymus, bone marrow, spleen, lymph node, and tonsils, that play key roles in the human immune functions, followed by comprehensive discussions on how their biological properties can be recapitulated using in vitro models including organoids. We also compare each immune model in Table 1. To educate new to this field, we next summarize methods and high-throughput assays to identify morphological and physiological features which are critical to organoid functionalities. Compared to other organoid models, the human lymphoid organoids are at the nascent stage with only less than ten papers published thus far. At the end of this review, we highlight challenges to generate immune organoid for translational human immunology, followed by bioengineering solutions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review discussing the progress in immune organoid research and we hope that this work will motivate immunologists, material scientists and tissue engineers to create immuno-engineered organoids as a viable alternative to animal models to support the field of translational immunology.

Table 1.

Comparisons of human immune models.

| Animal model | Organ-on-a-chip | Precision cut tissue slices | Organotypic culture | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accessibility | ✓/✗ | ✓✓✓ | ✓ | ✓✓✓ |

| Physiological complexity | ✓✓✓ | ✗ | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓ |

| Immune cell diversity | ✓✓✓ | ✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓ |

| Vascularization | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✗ | ✓/✗ |

| Maturation | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓/✗ |

| Reproducibility | ✓/✗ | ✓✓✓ | ✓/✗ | ✓/✗ |

| Manipulability | ✓/✗ | ✓✓ | ✗ | ✓✓✓ |

| Scalability | ✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✗ | ✓✓ |

| Genome editing | ✓/✗ | ✓✓ | ✗ | ✓✓✓ |

| High-throughput screening | ✗ | ✓✓✓ | ✓ | ✓✓✓ |

| Biobanking | ✓✓ (Only at cellular level) | ✗ | ✓/✗ | ✓✓✓ |

| Model immune responses | ✓✓✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ |

| Model human diseases | ✓✓ (Limited to humanized mice) | ✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓ |

| Ethical and regulatory compliance | ✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ |

✓✓✓Best ✓✓Good ✓Partly applicable ✗Not applicable.

2. Comparing lymphoid organ biology and their models

Lymphoid tissues are integral parts of the human immune system where they play a central role in our defense mechanisms against infections and to maintain homeostasis. They are broadly classified into primary and secondary lymphatic organs. Primary lymphoid tissues consisting of bone marrow and thymus gland are essential to produce immune cells, named lymphocytes [43,44]. It is a place where hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) divide and nurture into B and T cells. Particularly, B cell maturation also takes place in the bone marrow, while T cells need to migrate to the thymus for its maturating stage [45]. Lymphocytes and non-lymphoid cells are coexisting in secondary lymphoid tissues to deploy immune responses to antigens. Secondary lymphoid organ development relies on homeostatic chemokines, cytokines, and growth factors (e.g., lymphotoxin-αβ, tumour necrosis factor (TNF), and interleukin (IL)-7) that orchestrate the interactions between hematopoietic cells and immature mesenchymal or stromal cells. The lymphotoxin signalling determines the morphophysiological properties of secondary lymphoid organs by maintaining those adhesion molecules and chemokines [46,47]. Spleen, lymph nodes, and mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (e.g., tonsils) are the major secondary lymphoid organ where lymphocytes activate their functions. They serve as a series of filters to sort the contents of the extracellular fluids, such as lymph, blood, and tissue fluid [48,49].

It is important to understand tissue niches, features, and critical functions attributing to in vitro organ remodelling. Table 2 shows side-by-side comparisons of lymphoid organs, which are helpful to highlight differences in their biological key functions and provide insights to bioengineering approaches to generate and characterize the physiological authenticity in vitro human organ mimicking models. This table compares tissue morphologies, organ functions and cell phenotypic markers, and existing in vitro models for lymphoid organs as an alternative to animal models.

Table 2.

Characteristics of lymphoid organs and their models.

| Primary lymphoid organ | Secondary lymphoid organ | |

|---|---|---|

| General features |

|

|

| Organ type | Bone marrow | Thymus | Spleen | Lymph Node | Tonsil | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structures |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Functions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Critical immune cell markers |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Existing models | ||||||

| Physiological properties of existing models |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Challenging features |

|

|

|

|

|

2.1. Primary lymphoid organs mimicking models

2.1.1. Thymus

As one of the primary lymphoid organs, thymus performs an essential task for the generation and maturation of T lymphocytes for the adaptive immune responses [50]. It spatially regulates T cell functions and development within the epithelial-mesenchymal tissue, while the T cell output is highly affected by age throughout the lifespan due to thymus involution with age [51]. The thymus structures are made up of particular stromal cells known as thymic epithelial cells (TECs), which are divided into cortical (cTEC) and medullar (mTEC) regions [52,53]. Both cTEC and mTEC subsets control the T cell selection process and localize the developing thymocytes for T cells efflux [54]. Another important transcription factor to maintain TEC functions is the autoimmune regulator (AIRE) protein, which is produced in mTECs to regulate tissue-restricted antigens (TRA) expression implicated in T cell processing [55].

Reflecting human T cell development in vitro and their fundamental role in immune defense would be insightful to overcome some medical conditions (e.g., congenital or acquired immune deficiency) related to the thymus functions. Numerous studies have demonstrated the phenotypic diversity of TECs and mediatory molecules that are crucial for T cell selection and maturation [[56], [57], [58]], which is believed to provide reliable concept for ex vivo thymus organ constructs. In 2020, Campinoti et al. reported the reconstruction of functional human thymus using cultivated epithelial-mesenchymal hybrid cells, thymic interstitial cells, and decellularized extracellular matrix (ECM). This natural thymic scaffold with unique 3D epithelial framework was generated by whole-organ decellularization using de novo organ perfusion approach. Their anatomical in vitro thymus model showed its functionality by the capability to support T cell development and maturation after being transplanted into humanized immunodeficient mice (Fig. 2A) [59]. Nevertheless, efforts to rebuild a functional thymus artifact have limited success so far, due to inherent organ complexity and uncertain postnatal mesenchymal- and epithelial progenitor cell fate. Humanized mice are powerful preclinical model for representing immune system and diseases, but they lack physiological properties of human thymus and thus, human T cells generated from mouse thymus are unable to engage with other human immune cell subsets and mount insufficient immune responses.

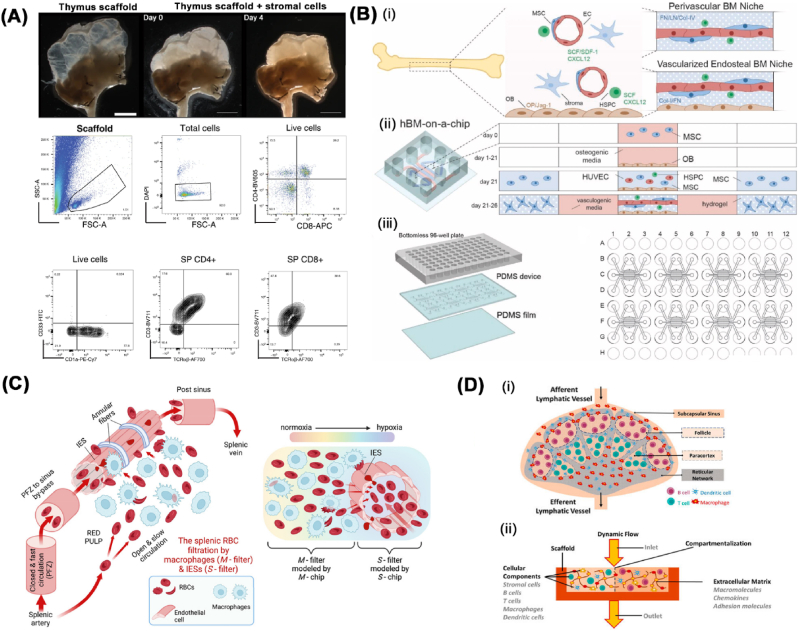

Fig. 2.

Existing lymphoid organ models. (A) Functional repopulation of whole-organ human thymus scaffolds. Gross microscopic images of a thymus scaffold after stromal cells injection (top panel) and representative flow cytometry analysis of multicellular compositions from repopulated scaffold after 8 days in culture (below panel). Reproduced under terms of the CC-BY license [59]. Copyright 2020, Nature Portfolio. (B) The design of human bone marrow-on-a-chip consisting of (i) co-culturing concept between perivascular- and vascularized endosteal bone marrow niche, (ii) an illustration of 5-channel microfluidic device and (iii) 96-well plate layout of human bone marrow-on-a-chip. In Fig. 2B(ii), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are differentiated for 21 days in the central channel of the device to generate endosteal layer, followed with human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), MSCs, and HSPCs being loaded on top of the endosteal layer and vasculogenesis occurs within 5 days to form the human bone marrow-on-a-chip. Reproduced with permission [72]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier. (C) Schematic diagram of spleen-on-a-chip platform containing macrophage rich zones (M-chip) and splenic inter-endothelial slits (IES) in the wall of sinuses (S-chip) to mimic splenic filtration of altered RBCs. Reproduced under terms of the CC-BY license [83]. Copyright 2023, The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. (D) Lymph node model in vitro. (i) Schematic illustration representing human native lymph node and (ii) requirements and compartmentalization for biomimetic lymph node-on-chip. Reproduced under terms of the CC-BY license [91]. Copyright 2021, Frontiers.

2.1.2. Bone marrow

Bone marrow is a central lymphoid organ owing to its pivotal responsibility in producing and maintaining immune cells in an antigen-independent manner. Bone marrow significantly contributes to the regulatory immune system by providing the microenvironmental framework for lymphocyte development. It is equivalent to the thymus for T cell development as bone marrow is essential for generation and maturation of B lymphocytes [[60], [61], [62]]. HSC-derived B cells are developed in bone marrow preceding their egression to secondary lymphoid organs and thus, it is responsible for humoral immune responses and maintaining long immunity [63,64]. Bone marrow is an antigen-free niche for the activated state of T lymphocytes, and it is where recruitment and retention of central memory T cells occur [65,66]. Dendritic cells (DCs) population in the bone marrow are able to evoke central memory T cell-mediated immune responses via interactions with tumour-associated antigens and thus hold essential functions in adaptive immunity [67,68]. Bone marrow is also a harbour for NK progenitor cells, due to its commitment to hematopoietic stem cells [69]. Altogether, bone marrow is not only a major hematopoietic organ, but also a primary human regulatory organ enabling fine-tuning of immunity.

A study has been reported to mimic physiological characteristics and functions of bone marrow throughout engineering approach, such as bone marrow-on-a-chip reconstruction. Torizawa et al. pioneered a method to fabricate bone marrow-on-a-chip, which recapitulates cellular diversity and complex biological functions of intact bone marrow microenvironment with its relevance to hematopoietic niches [70]. This engineered bone marrow enabled autonomous production of growth factors necessary to maintain the functions of hematopoietic system in vitro, which was advantageous over existing culture systems that require expensive growth supplements. Their proof of concept was only demonstrated in mouse model, implying that further studies are essential for human bone marrow explorations. Latterly, a vascularized human bone marrow-on-a-chip recapitulating key aspects of haematopoiesis as well as bone marrow dysfunctions has been established by the same research group [71].

In 2021, microfluidic human bone marrow-on-a-chip incorporating the endosteal, central marrow, and perivascular niches was developed in 96-well format (Fig. 2B) [72]. It exhibited complex, high-throughput, multi-niche microtissue that resembles human bone marrow composition and micro-physiological system, including maintenance of CD34+ HSCs. Although these on-chip modelling can overcome some limitations in animal study, they still cannot completely reorchestrate the 3D structures correspond to the native organ and thus, there is high possibility for some physiological and morphological functions remain absence in microfluidic settings.

2.2. Secondary lymphoid organs mimicking models

2.2.1. Spleen

Spleen is a secondary lymphoid organ that hosts a massive blood-filtering process with its critical roles in the functional immune system [73,74]. Spleen tissues are divided into the white and red pulp with marginal- or perifollicular zone between the two regions. Red pulp region is associated with blood filtration and removal of aged RBCs [75]. Additionally, red pulp is crucial for fighting against bacteria and blood-borne pathogens due in part to the high variety of residing leukocytes including monocytes, neutrophils, DCs, macrophages, and lymphocytes [[76], [77], [78]]. The splenic white pulp is considered to have primary immunological functions of the spleen, due to compartmentalization of B and T cells during germinal centre (GC) response that is analogous to the lymph node structure. Given the unique physical organization and composition of the spleen, it possesses notable roles in guiding the innate and adaptive immunity respectively [73,[78], [79], [80]].

Traditional methods of studying the spleen have been limited to post-mortem analyses or animal models, which often fail to accurately represent human physiology. In vitro spleen modelling represents a significant advancement in understanding the organ function, particularly in relation to diseases such as malaria and sickle cell disease. James et al. pioneered the spleen modelling using precision-cut tissue slice of human spleen [81]. Spleen tissue slices were able to preserve ECM configuration including certain homologous and heterologous associations found in real tissue niche. Their findings marked the differences between tissue slices and cell suspensions, in which the spleen tissue slices secreted higher levels of immunoglobulin and cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-11) rather than splenocytes culture. The increase of cytokine production in tissue slices can be due to the direct interaction between stromal cells and B cells, which is crucial for mediating important signals necessary for cytokine secretion. Nevertheless, tissue slices cannot be retained for long-term culture (>4 days), which hinders its potential for immunological investigations, such as identification the mode of action of new immunomodulatory compounds.

A study by Rigat et al. focused on replicating the human spleen's complex blood filtration and pathological functions through a precise controlled micro-engineered device [82]. It consisted of (1) two microfluidic channels to mimic the closed-fast and open-slow microcirculation that maintained a physiological flow division, (2) pillar matrix to augment haematocrit and emulated the spleen's reticular meshwork, and (3) micro-constrictions incorporation to replicate the inter-endothelial slits (IES) of the spleen, which was crucial for the organ's filtration process. Another recent work demonstrated a microfluidic system to depict the retention and elimination of RBCs in human spleen (Fig. 2C) [83]. It comprised two modules called "S chip" that mimicked the function of micro-slits between the cells to filter blood, and "M chip" that recapitulated the behaviour of macrophages. The S chip module revealed that both shape and mechanical properties of RBCs influence their retention especially under deoxygenated conditions. Meanwhile, the M chip module showed that macrophages need longer time to digest stiff sickled RBCs and thus slowing the clearing of clogs at low oxygen levels. These findings highlight the importance of a homeostatic balance between retaining and eliminating RBCs in the spleen. Although the spleen-on-a-chip model provides valuable insights into disease treatment and prevention, micro-engineering approach is still far from the in vivo 3D microenvironment of spleen, which indicates that some physiological characteristics might be diminished upon the system.

2.2.2. Lymph node

One of the specialized tissues important for the immune microenvironment is the lymph node (LN), which provide immunological venues for the crosstalk between various lymphoid cells following the antigen exposure [[84], [85], [86], [87]]. The LNs usually form clusters in certain area of the body and are interconnected through the lymphatic vessels (LVs) that facilitate lymphatic fluids (lymph) filtering and draining in the circulatory system [88]. Stromal cell subsets in LN has distinct roles in enforcing immunological response, albeit they combine to support the primary function of LNs — that is to fight pathogens in the lymph and return the filtered fluids into bloodstream [89]. Fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs) is the most heterogeneous stromal cell populations and located in T-cell zone, which have multifunctional features and systemic activity that are critical for the LN microstructural homeostasis alongside the propagation of adaptive immunity in LNs [90].

Engineering human LN model is innovative in vitro system to study its complex physiological and pathological processes in a controlled environment. For instance, lymph node-on-a-chip demonstrated dynamic conditions by using peristaltic pumps to facilitate active fluidic perfusion, including the transport of chemokines and other cell markers to induce cellular cross-talk (Fig. 2D) [91]. The use of primary cells is another important aspect in creating LN model as the immortalized cell lines fail to fully replicate humoral immunity in which naïve B cells need to proliferate, differentiate and become antibody secreting cell. However, primary LN cells are restricted due to low availability of tissue donors. Moreover, designing a biomimetic LN model that can effectively facilitate the co-culture and spatial arrangement of multiple cell types (e.g., B and T cells, DCs, and stromal cells) emulating structural organization in the native organ still remains challenging.

2.2.3. Tonsils

Tonsils are a set of secondary immune organs located in the pharynx and collectively known as one of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues [92]. These organs act as the primary site for immune protection against inhaled and ingested germs at the upper aerodigestive tract [93,94]. Palatine tonsils are considered the most easily accessible human lymphoid organ for wide immunological studies. They prominently influence tonsillar immunity since the tonsils comprise approximately 65 % of B cells, 30 % of CD3+ T cells, and 5 % of macrophages [95]. Either cellular or humoral immunological mechanisms are initiated in their different compartments (e.g., crypts, lymphoid follicles, and extrafollicular region). Moreover, the architecture of tonsils including GC in B cell follicles and extrafollicular T-cell-enriched area resembles the particular structure in LN, regardless of their lack of afferent lymphatic vessels.

Although tonsil tissues are relatively accessible, their exploration for immuno-engineering research is still minimum. Majority of tonsil studies are achieved with fresh tonsil tissue slices or ex vivo culture. For example, human tonsillar tissue block has been successfully cultured up to 4 days to investigate immune cell behaviours within their niche. Tissue block culture showed less activated T cells to express CD95 and exhibited contrasting constitutive cytokine gene expression patterns compared to the autologous tonsillar cell suspension cultures [96]. Another study reported the use of tonsil explant culture to reveal the cell-cell and cell-pathogen interactions. Tissue blocks maintain their cytoarchitecture that play the role in productive infections of pathogens without exogenous stimulation [97]. This ex vivo modelling system is widely applicable to investigate microbial and histological profile of patient-derived tonsil tissues, including their susceptibility toward viruses [98,99]. Nevertheless, live tonsil tissue slice can only be retained within a short period of time and contamination is highly likely occurred in this culture setting. Bioengineering approach can be promising to enhance the use of tonsils for immunological studies.

3. Modelling human adaptive immune system with in vitro organoid models

In the earlier section, we described the advantages of organoid technology including high accessibility, robustness, and larger quantity of material provision as compared to the use of animals. In this section, we elaborate on the use of organoids for modelling human immunological responses. Organoid technologies have emerged as a sophisticated physiological model system for various research areas, exceptionally in the field of immunology. The relevance of organoid technology for translational immunological research can be summarized through a SWOT analysis (Table 3). The SWOT table is helpful to assess multiple aspects and scientific parameters in the progress of immune organoids, particularly on how they could address the biological- and clinical issues. As an example, tonsil organoid culture was firstly reported as a groundbreaking technology to study human immunological aspects in ex vivo manner [35]. Tonsil organoid successfully tackled the difficulties to carry out the adaptive immune responses that is primarily related to B cell immunity. Meanwhile, the innate and cellular immune responses in tonsil organoids remain unresolved and thus, it could be the opportunities for further explorations.

Table 3.

The SWOT analysis of organoid technology.

| SWOT ANALYSIS | |

|---|---|

| STRENGTH | WEAKNESS |

| Biological relevance: Organoids closely mimic organs, enhancing physiological accuracy compared to traditional cell cultures. | Standardization challenge: Organoid cultures are complex and variable, hindering standardization. |

| Disease modelling: Organoids enable in vitro disease study and treatment testing. | Functional complexity limitation: Organoids mimic organ aspects but may not fully replicate functional complexity, especially aging effects. |

| Personalized medicine: Patient-derived organoids facilitate tailored drug testing and treatment optimization. | Technical expertise requirement: Establishing and maintaining organoid cultures demands specialized skills, limiting widespread adoption. |

| Reduced animal reliance: Organoids offer an ethical alternative to animal models, potentially decreasing animal testing. |

Cost and resource intensity: Organoid technology is resource-intensive, requiring specialized equipment and personnel. |

|

High-throughput screening: Organoid technology allows simultaneous testing of multiple drugs or conditions. | |

| OPPORTUNITIES | THREATS |

| Drug discovery and development: Organoids enhance preclinical drug testing, potentially reducing clinical trial failures. | Competing technologies: Emerging alternatives pose a competitive threat to organoid technology. |

| Regenerative medicine: Organoids show promise for organ transplantation and tissue repair. | Regulatory hurdles: Adaptation of regulatory frameworks is needed for organoid technology. |

| Collaboration with industry: Partnering with pharmaceutical and biotech industries accelerates organoid research translation. | Limited funding: Funding constraints may hinder organoid technology research. |

| Technological advancements: Ongoing innovations like microfabrication and bioengineering improve organoid capabilities and reproducibility. | Public perception: Acceptance of organoid technology, especially with human-derived materials, influences adoption. |

| Expansion of applications: Continuous research uncovers new organoid technology applications, extending its use. | |

Self-organizing organoids can reflect structural properties and physiological characteristics of their respective parent organs, making them highly relevant for human disease and pathophysiological studies. Recent works found that human autologous tissue-derived organoid/immune cell co-culture was favourable as in vitro models to modelling the diseases and to evaluate the efficacy of drugs or personalized clinical treatment [[110], [111], [112], [113], [114], [115]]. For instance, the immunosuppressive function of polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells toward cytotoxic T lymphocytes was revealed through the crosstalk between patient-derived pancreatic cancer organoids and co-cultured CD8+ T cells that were activated by the autologous DCs — indicating scientific rationale to the inefficient cancer immunotherapy [116]. Santos et al. recently reported air-liquid interface duodenal organoids from intact tissue biopsies that preserve epithelium with native mesenchyme and tissue-resident immune cells to model an autoimmune disease [117]. Another review discussed the potential of patient-derived cancer organoids (PDOs) to recapitulate the tumour microenvironment that is antithetical to normal immune functions to provide insights into cancer immunobiology [118]. Unfortunately, all these studies only provided 2D immune cellular environment in organoid surroundings, which might be inadequate to reflect the actual architectural and functional complexity of innate and adaptive immune systems. Building bioengineered lymphoid organoids will enable more advanced immunological investigations.

In terms of microarchitectural intricacy and physiological functions, lymphoid organoids possess superior biological attributes than conventional monolayer immune cell culture. Nevertheless, human immune organoid development is still a nascent field compared to other types of organoid generation (e.g., brain, kidney, liver), and thus researchers pioneered this study by initially using animal-derived lymphoid organ to generate immune organoid models. Numerous studies revealed successes in establishing mouse-derived immune organoids, such as immuno-engineered organoids with encapsulated naïve murine B cells and 40LB stromal cells that resembled GC-like phenotype of lymphoid tissue with an almost tenfold increase of GC B cells production compared to the 2D cell culture [33]. This increase in efficiency allows for more robust and reliable studies on the immune system, facilitating a better understanding of immune cell dynamics and responses. The other lymphoid organoids generated from mouse LN stromal progenitors and decellularized extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffold are useful in restoring lymphatic drainage and immune tissue functions after LNs surgical resection [34]. Animal-derived lymphoid organoids may closely mimic the physiological conditions of the in vivo microenvironment and provide similar representation of the organ functions with a simplistic manner. However, although mouse models have become a cornerstone for pathophysiological investigations, their transcriptional responses still poorly reflect human diseases and immunological behaviours [119]. This indicates that animal-based immune organoids might not be proper for human disease modelling and drug testing.

While human-derived immune organoids have not been extensively reported, they are favourable alternative animal models to further understanding of the human adaptive immunity. The latest breakthrough emanates from a development of human tonsil organoids that replicates key immunological features in vitro, including antigen-specific adaptive immune reactions upon live attenuated influenza vaccination [35]. The finding demonstrated the capability to build up human-based immune organoids as an innovative in vitro model that could accelerate studies on human immunological aspects. For example, the human complex immune environment is currently more accessible through lab-scale immune organoids, which have better physiological relevance than even transgenic, humanized animal models. Interaction between immune organoids and other organoid types also could be an excellent ex vivo approach to study events from cancer metastasis to tissue crosstalk and homeostasis (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Overview of the currently established human immune organoid generation methods, including (A) cell co-culturing system, (B) conventional direct cell culture in tissue culture dish, (C) disposable bioreactor system, and (D) Hydrogel scaffolds embedding method. Figure C is reproduced with permission [108]. Copyright 2010, Elsevier.

3.1. Bone marrow organoid

The bone marrow holds profound significance in the human body as a primary site for the production and regulation of hematopoietic cells, which are vital for oxygen transport, immune defense, and blood clotting. It also serves as a critical component of the immune system, housing immune cells and contributing to immune responses. Moreover, it plays a key role in various diseases, including haematological malignancies and autoimmune disorders. A long-standing need for human bone marrow modelling system for translational studies has been overcome through recent progress in organoid research.

Recently, Khan et al. successfully established a direct differentiation protocol for generating a novel 3D organoid model using human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) that mimics the human bone marrow microenvironment, thus offering a versatile platform for studying haematopoiesis, haematological diseases, and drug development to reduce the reliance on animal models [102]. The iPSCs initially formed non-adherent mesodermal aggregates, followed by commitment to vascular and hematopoietic lineages. These cell aggregates were embedded in collagen-Matrigel hydrogels to induce vascular sprouting and these organoids were observed to have vascularization resembling the native bone marrow, with intricate networks of HSPCs, megakaryocytes, and erythroid cells closely mirroring the bone marrow architecture. Single-cell RNA sequencing found that the hematopoietic and stromal cell lineages within organoids had transcriptional similarity to human hematopoietic tissues.

The above study also explored the impact of adding vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C) to the differentiation protocol and identified changes in the transcriptional phenotype of the vasculature within the organoids, including increased expression of bone marrow sinusoidal endothelial markers and upregulated signalling pathways like TGFβ-1 and CXCL12. These findings suggest that the communication networks within these organoids recapitulate key regulatory interactions in adult bone marrow. To this end, the researchers explored the potential of bone marrow organoids to support the engraftment of primary cells from patients with haematological malignancies, offering a platform for modelling interactions between cancer cells and the stromal microenvironment. These bone marrow organoids thus offer a way to investigate the cross talk that takes place in healthy haematopoiesis and how disruptions in these interactions can contribute to the development and advancement of cancers.

3.2. Thymic organoid

Bioengineering of thymus architectures has gained a lot of interest although this is still in its early developmental stages. An in vitro thymus model called artificial thymus organoids was developed using murine thymic cells dissociation that can resemble T cell selection through co-culture with fibroblasts (e.g., mesenchymal stromal cells or mouse embryonic fibroblast) under organ culture conditions. Early stages of thymopoiesis are associated with both mesenchyme and MHC class II-positive epithelium requirement, while later developmental and maturation stages can be supported by epithelial cells alone. From this study, both mesenchymal and MHC class II-positive epithelial cells were found to play roles in stage-specific T cell development, in which T cell precursors (TCR−CD4−CD8−) would turn into positive cells (TCR+ with CD4+ and/or CD8+) [120].

Another research progress has been made to facilitate in vitro human thymic modelling with its robustness to overcome some drawbacks from animal studies. For the first time, artificial thymic organoids consisting of mature T cells were successfully established from human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) under serum-free culture conditions. Instead of using primary thymic cells, mouse DLL1-transduced stromal cell lines were used to support human thymocyte development (Fig. 3A). The organoid was formed upon stromal cells aggregation with HSPCs by centrifugation and seeded on a cell culture insert at the air-liquid interface. The results demonstrated that positive selection of T cells was enhanced in thymic organoids, suggesting the ability of 3D cellular architectures to accelerate T cell precursors and specific ligands interactions.

The TECs were absent in thymic organoids and thus positive selection of CD4 single-positive cells was achieved through MHC class II presented by dendritic cells residing in organoid, while CD8 single-positive cells were selectively processed via MHC I ligand presented by HSPCs. This organoid system also can be used to develop stem cell-based TCR-engineered T cells for immunotherapeutic potential [103]. However, further attempts to induce TEC growth in thymic organoids and to overcome the challenge of HLA diversity would be essential for better modelling of real thymus organ. HLA antigens are important molecules located on the cell surface that play a critical part in the immune responses to foreign substances. The clinical significance of HLA antigens is relating to transplant rejection due to their variability from person to person [121]. Therefore, HLA polymorphisms is another important area of research that is inseparable with translational study of human diseases and immune defense.

Numerous works about generating functional TECs from pluripotent stem cells (e.g., human embryonic stem cells) have been reported [122,123]. Another recent advancement in stem cell technology has led to the generation of patient-derived TECs from multiple iPSCs to solve the thymus donor shortage. Different somatic cell sources were used for iPSCs reprogramming, such as cord-blood-derived peripheral blood mononuclear cells and neonatal dermal fibroblasts. After being successfully reprogrammed, the iPSCs gave rise to thymic epithelial progenitor cells through a direct differentiation protocol, followed by further differentiation into functional TECs during transplantation on athymic immunocompromised mice. Although the different expression level of FOXN1 in thymic differentiation stages was observed due to distinct iPSC lines, the thymic epithelial progenitor graft still interacted well with developing T cells to become mature into TECs in the absence of mesenchymal cells [124]. Overall, this finding could bridge the gap between stem cells and immunology either by allowing the possibility for stem cell-derived immune organoid culture or by improving current established thymic organoid protocol with stem cell-based approach. This will be favourable to reducing primary tissue acquirement and also provide patient-specific thymus model for improvement in cell replacement therapies.

3.3. Tonsil organoid

Taking advantages from high availability of human tonsils after tonsillectomy, an immune organoid was successfully developed from this lymphoid organ using cellular reaggregation method as described by Wagar and co-workers (Fig. 3B). This is the first attempt to establish human immune organoid that recapitulates adaptive immune features. Briefly, the cryopreserved single-cell dissociation of tonsil tissues was thawed and grown at high density along with an antigen of interest. Reaggregated cultures referred to as tonsil organoids were visible after 2–3 days of cultivation period and followed with subsequent analyses in the presence or absence of antigen. Live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) was selected as testing antigen to reveal organoid features toward human influenza. The LAIV-stimulated group showed apparent increases in B cell function and maturation as reflected by significantly higher plasmablast frequencies compared to unstimulated organoids (controls). More importantly, this in vitro model exhibited antibody class switching, affinity maturation, and antigen-specific somatic hypermutation of human B lymphocytes. The ability of tonsil organoid system to detect human immune responses variability was further evaluated, which is useful to broaden vaccine development [35]. In fact, the presence of lymphoid stromal cells in tonsil organoids have not investigated yet, while they play crucial role for immune responses. This tonsil organoid model also lacks reproducible sizes and shapes due to spontaneous cell reaggregation method, making it difficult for vaccines or drugs screening applications. Current organoid culture technique will be challenging for an industrial scale-up purpose, and thus there should be technical improvement to overcome the aforementioned drawbacks of tonsil organoid model.

Another most recent approach to generate tonsil organoids is through matrix encapsulation (Fig. 3D). The organoid was cultured from tonsil epithelial-derived cells under confined ECM microenvironment (Matrigel). The organoid formation was successfully generated as well as its expansion capability after subsequent optimisations of culture conditions. In terms of immune responsiveness, it was suppressed due to the IL-2 signalling and antigen-activated B-cell receptor downregulation caused by tonsil organoids differentiation tendency to epithelial cells rather than immune cells. Based on the data for their functional study, tonsil epithelial organoids activated their innate immunity when exposed with TLR4-stimulating pathogen-associated molecular pattern or lipopolysaccharide as same as tonsil tissues. Both molecular and morphological features of tonsil epithelial organoids were further compared to their native tissues in order to evaluate their utility as an ex vivo studies for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Remarkably, the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, transmembrane serine protease 2, and Furin were found to be expressed in tonsil epithelial organoids, suggesting that they were susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 [109]. Thus, it is desirable to use this approach as an antiviral drug screening platform and to alternate animal models in therapeutic drug efficacy testing. However, due to bias differentiation into epithelial cell lineage other than immune cell types, this tonsil organoid model did not represent adaptive immune mechanism. The crosstalk between tonsillar immune organoids, tonsil epithelial organoids, and infectious agents might be helpful to provide comprehensive investigations of host defense mechanism towards innate and adaptive immune system, including strategies to counteract host immunity.

3.4. Lymph nodes organoid

Lymph node (LN) development holds critical roles in promoting adaptive immunity, in which the process is correlating to cell-cell communications and cell-ECM microenvironment interactions [125]. The LN damage or injury due to infections or specific medical treatment (e.g., surgical resection or radiotherapy) affect immune functions and disease progression. There have been numerous studies that employ tissue engineering strategies to create artificial LN tissues. For instance, functional synthetic lympho-organoid has been generated from major constituents of secondary lymphoid organ. It consists of mouse LN stromal progenitor cells and physiological ECM scaffold obtained from decellularization of monolayer spleen stromal cell line [34]. The lympho-organoid structures were compact the same manner as native LN architecture and also supported vascularization and infiltration in the tissue graft. Incredibly, transplantation of lympho-organoid in mice at the site of resected LN showed regeneration of lymphatic and immune responses, indicating that this preclinical study could be a robust approach for organoid-based regenerative therapy. However, more investigations are needed to fill critical gaps between laboratory animal grafting and human physiological system as some immunobiological aspects in humans including somatic hypermutation, antibody affinity maturation, and class-switching are not found in mouse.

Bioengineering approach attempting to remodel lymphoid tissue-like structures in bioreactors, so-called human artificial LN mini-organoid has been reported as well (Fig. 3C) [108]. Specifically, the organoid formation relied on co-culturing human peripheral blood mononuclear cell-derived lymphocytes and mature DCs using two types of disposable perfusion bioreactor platforms (HIRIS™ III and IG-Device™) that could imitate the physiological environment of immune responses in vitro. Commercial hepatitis A vaccine and cytomegalovirus were chosen as the antigen of interest as the selected human donors were seronegative for Hepatitis A- or CMV-infection. Immunosuppressive effects were subsequently investigated by exposing the organoid culture with 1 μM of dexamethasone. Immunological testing in this LN organoid were carried out through subsequent analysis, including cytokine secretion patterns that correspond to early humoral responses, and immunohistochemical staining of organoid-containing matrix sheets to visualize organoid morphology.

The above work demonstrated that immune responses from LN organoid were monitored through several cytokines release and antigen-specific antibody (IgM) production, while the immunosuppressive drug testing was effective to reduce cytokines production, especially pro-inflammatory cytokine. Recently, researchers have also demonstrated the utility of this model for studying immune responses and drug reactions, particularly in testing glycoprotein vaccines and investigating the immunogenicity of protein aggregates from antibodies like bevacizumab and adalimumab under varying stress conditions [126]. Taken together, this organoid model provides great insight on immuno-modulation substances in dynamic culture conditions. This bioreactor system is also scalable for high-throughput testing. In fact, the complex and costly setup would be another challenge to utilise this bioreactor approach for organoid manufacturing. Further improvements are also necessary to perfectly mimic the corresponding organ as the stromal cell environment was missing, while it plays the role in lymphocytes homing and segregation, modulating the balance steady-state and inflammation, antibody class-switching, and affinity maturation [127].

Using similar protocol to generate human tonsil organoids, Wagar et al. also made attempt to establish comparable human LN organoids [35]. The LN organoids elicited GC-like structures that further led to plasma cell differentiation and antigen-priming ability to naïve antigen up to this point. However, they fell short of demonstrating some other immunological parameters that were carried out in tonsil organoids (e.g., somatic hypermutation and antibody affinity maturation). The LN organoid characterisations were accomplished only for justifying the proof-of-concept. Moreover, none of the other published reports has explained the explorations of human LN organoid culture yet, probably due to some ethical issues or limited access to the LN primary tissue samples. Despite the aforementioned concerns, further studies are still encouraged to overcome challenges in utilizing ex vivo human lymphoid-derived organoids, including LN organoids, as it will be worthy to substitute animal studies for revealing the entire human immunological features.

3.5. Spleen organoid

Spleen abnormality usually leads to either partial or complete splenectomy that is taken to prevent life-threatening haemorrhage. Complete absence of the spleen could trigger post-splenectomy risks, including immune homeostasis alteration that increases the susceptibility of patients to other infections (e.g., pneumonia, venous thromboembolism, pancreatitis) [128]. Tissue engineering development is a useful approach to restore splenic function post splenectomies as well as explore spleen immune features ex vivo. Purwada et al. engineered organoids from murine spleen through co-culture system between mouse spleen-derived B cells and transgenic 40LB stromal cell line [32,33]. These cells were further encapsulated in gelatin hydrogel incorporated with silica nanoparticles that enable the tuning of stiffness, architecture, and porosity of the scaffold to resemble native lymphoid microenvironment. The hydrogel approach also helps in maintaining organoid size and shape, which is important for a high-throughput system. This ex vivo immune organoid showed potential to overcome the limitations of 2D tissue-culture plate systems and animal models owing to its ability to recapitulate key immunological events such as GC-like reactions, differentiation of B cells, and antibody class switching. In fact, current organoid system still has limitations in antigen-specific antibody production, affinity maturation, and dark- and light zone formation in the GC-like structures. Although the organoid culture was using hydrogel polymer to achieve a Matrigel-free system, the origin of organoid source still raised a concern as it is primarily derived from murine, indicating the difficulty to carry out this study for further translational medicine. Hydrogel scaffold functional fabrication could also be complicated and its degradation properties is another concern as it might hinder the possibility of long-term organoid culture.

Another effort to build tissue-engineered spleen with more relevance to human organ has been reported (Fig. 3D) [107]. Human spleen specimens were obtained from 7 to 12-year-old patients, which further undergo subsequent downstream processing to generate proliferative spleen organoid units. Based on characterisation results, the spleen organoid units exhibited some expressions of CD4 and CD11c markers corresponding to T cells and dendritic cells, along with Lamin-positive cells. These phenomena are found to be identical to the stained human spleen regardless of its quantity expression level. The ability of human tissue-engineered spleen organoids to solve functional issues after splenectomy was further investigated. Interestingly, they recapitulated rudimentary spleen architecture after implantation in asplenic mouse and restored the damaged red blood cells within 1 month. However, some immunological aspects are not elucidated in this model such as T cell subsets characterisation, whereas the native splenic architecture leads to the functioning of cellular initiators and effectors for adaptive immune surveillance. Further evaluation must be conducted for better understanding of immune responses in organoid model, which will be beneficial for future clinical translation in the patient.

4. Assays to evaluate immune organoid functions, morphology, and compatibility for clinical applications

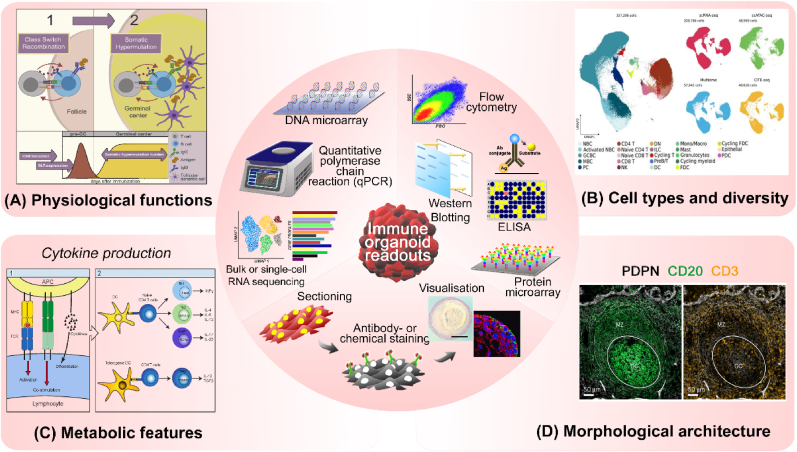

Organoid analysis has great importance to precisely evaluate their characteristics and functions to use them as translational models. Fig. 4 illustrates immune organoid readouts that are critical for assessing critical biological attributes on immune organoids, such as (1) analysing organoid multicellular diversity and phenotypic changes at the genomic and transcriptomic level using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), DNA microarray, cytometry time-of-flight (CyTOF), and bulk- or single-cell RNA sequencing, (2) revealing key surface markers, metabolic functions, and protein secretions in organoid using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), flow cytometry analysis, western blotting, and protein microarray, and (3) visualizing both physiological and morphological properties of the organoid throughout immunofluorescence or histochemical staining. Making use of these assays, we also compare the two main characteristics – stem cell-derived and ex vivo donor tissue – to generate organoids in Table 4.

Fig. 4.

Various characterization methods and readouts to evaluate immune organoids. (A) Antibody class-switching and somatic hypermutation analysis to check antibody responses representing physiological functions of immune organoids. Reproduced with permission [134]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier. (B) Multicellular composition and diversity in organoids can be revealed throughout multi-omics analysis. The UMAP projection data was reproduced under terms of the CC-BY license [129]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier. (C) Cytokine release assays could represent the metabolic functions of immune organoids. Reproduced under terms of the CC-BY license [135]. Copyright 2013, MDPI. (D) Histological-, immunohistochemistry-, and immunofluorescence staining are useful to analyse organoid morphological structures that closely resemble its native organ architecture. The immunofluorescence images showing GC formation in the presence of PDPN+ FRCs of palatine tonsils was reproduced under terms of the CC-BY license [136]. Inset histochemical- and immunofluorescence staining images within illustrative figure (centre) were reproduced with permission [109]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier.

Table 4.

Organoid cell sources and characteristics.

| Pluripotent stem cells | Human adult stem cells | Primary tissue cells | |

| Advantages |

|

|

|

| Disadvantages |

|

|

|

4.1. Physiological characteristics

It is critical to validate physiological relevance of immune organoids corresponding to their tissue origin (Fig. 4A). Gene expression analyses could reflect the organoid phenotypes and functions as it provides information of thousands of genes that encode proteins relating to cell physiological status. Multicellular compositions, cell-cell interactions, and representative cell type markers in organoid can be elucidated throughout biomolecular techniques. PCR method can detect the up- or down-regulation of few target genes in organoid, while RNA sequencing is more powerful to discover the whole genetic profiles and it provides greater sensitivity to reveal novel genes in high throughput performance compared to qPCR technologies. For this reason, either bulk- or single-cell RNA sequencing are preferable to organoid research, while qPCR analysis is typically used to validate expressions of target genes.

As an example, Seet et al. performed the deep bulk RNA sequencing to confirm physiological TCR clonotype diversity in human thymic organoids. The encoded sequences of TCR Vα and Vβ complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) in thymic organoid-derived CD3+TCR-αβ+CD8+ single-positive T cells was compared to both thymic and peripheral blood naïve CD8 single-positive T cell sequences, in which the results showed the comparable TCR diversity and functions of the organoid to the corresponding human thymus [103]. In addition, single-cell RNA sequencing was done to exhibit the GC-phenotype (CD38+CD27+) B cells in tonsil organoid. The data proved that the organoid cultures have similar transcriptional profiles within different time points. Both single-cell and bulk BCR sequencing were also obtained from LAIV-stimulated organoid cultures to investigate the diversity and affinity maturation of BCRs as both parameters are important for antibody responses. The hemagglutinin-specific BCRs were diverse in both gene and isotype level based on single-cell RNA sequencing, while the bulk sequencing of total non-naïve B cells explained how the antibody class-switching with some mutations were occurred during organoid cultures. The activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) assay also helps to confirm the somatic hypermutation and class-switching process in stimulated tonsil organoid as the AID molecule is highly expressed in GC centroblasts to initiate hypermutation of the immunoglobulin genes [35].

Revealing the multicellular types and diversity in organoid is also important along with their physiological characteristics (Fig. 4B). In 2022, the cell Atlas of human tonsil based on five different data modalities (transcriptome, epigenome, proteome, adaptive immune repertoire, and spatial arrangement) was reported [129]. This could be great reference to reveal the multicellular diversity and physiological similarity between tonsil organoid and its native organ in terms of immunological behaviours, i.e., how CD4 T follicular helper cells assist the B cells to initiate GC formation in organoids, immune landscape of CD8 and innate lymphoid cells when the organoid encounters antigen, and various B cell responses including B cell activation, GC dynamics, antibody class-switching, somatic hypermutation, plasma cell differentiation, and cell identity regulation in organoids. In the case of tonsil epithelial organoid generation, the genetic similarities study between native tissues and organoid was accomplished with DNA microarray analysis. The results suggested that overall gene expression in tonsil organoids overlapped with corresponding tissues, even some up- and down-regulated genes were mapped during SARS-CoV-2 infection and antiviral drug exposure upon the organoids.

Overall, single-cell transcriptomic analyses can meet multifarious parameters and functions in organoid, but the other research gap still remains as a challenge. For example, the samples need to be dissociated into single cells prior to the single-cell analysis, while these steps would eliminate cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions within the organoids that supposed to be critical in morphogenetic studies. The spatial transcriptomics method can tackle this issue, but it is relatively cost-consuming and thus it is not yet widely applied for organoid fields. However, some organoid studies showed promising results using spatial transcriptomic analysis, i.e., the use of spatial transcriptomics to investigate whether endometrial organoids resemble physiological pathways in vivo after hormonal treatment [130]. Flex et al. reported the use of spatial expression map and accessible chromatin landscape together with existing atlas data of developing brain to resolve characterization of organoid brain region [131]. Using spatial transcriptomics to understand the heterogeneity observed within immune organoids could be one of the great interests for their research progress. Therefore, the efforts to apply transcriptomic analysis in more effective manners are promising for its future research direction.

4.2. Metabolic functions

It is vital to quantify the levels of proteins that play key roles in metabolic activities and secretions (e.g., cytokine release) which influence organoid functions (Fig. 4C). Flow cytometry and ELISA methods are common techniques to detect protein expressions in biological samples. Cell counting, sorting, and determining cell characteristics and functions at the single-cell level can be acquired through flow cytometric analysis and thus it is a powerful method to analyse mixed cell populations in immune organoid. As an example, the immune cell type compositions and frequencies in tonsil organoids in the presence or absence of LAIV stimulation were determined by flow cytometry. This was also performed to analyse CD38 and CD27 expression patterns on LAIV-stimulated B cells and adjuvant effects, in which the data suggested pre-GC phenotype transition, followed with plasmablast differentiation within the organoid.

ELISA is another type of protein assays aiming to quantitatively detect antibodies, antigens, or specific proteins in biological specimens. This method was applied to identify the influenza-specific antibody secretion in tonsil organoids. The data exhibited that flu-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) was secreted after 7 days of stimulation with corresponding vaccine, indicating that the naïve B cells can produce hemagglutinin-specific antibodies [35]. In bioreactor-based LN organoid generation, either in-process controls or end-point evaluation were performed using standard ELISA. Immunoglobulin M (IgM) secretion was found to be enhanced during the immune suppression effects of dexamethasone, proving that this in vitro LN model can physiologically represent immune responses toward virus, vaccines, and other immuno-modulating substances [108].

ELIspot assay is an alternative way to detect specific protein or antibody signature from immune cells in a more sensitive manner, as this technique focuses on quantifying the antibody-secreting or cytokine-secreting cells. For example, the tonsil organoid stimulated with LAIV up to 7 days exhibited the influenza-specific antibody-secreting cells about 0.1–1.5 % of total B cells based on ELIspot analysis [35]. Other than two aforementioned analytical methods, western blot and protein microarray assays are also useful for immunological research and analysis. For instance, western blot analysis was performed in tonsil epithelial organoids to show their potential as the SARS-CoV-2 modelling study. Virus-infected organoids treated with remdesivir apparently showed dose-dependent antiviral activities through the significant decrease of viral spike and nucleocapsid protein expression as depicted in visualized protein band intensity [109].

In terms of protein microarray analysis, it was applied for antibody specificities evaluation against SARS-CoV-2 in tonsil organoid model by Kim et al. Upon a protein microarray results, specific IgG and IgA were produced from naïve tonsil organoid after being administered with series of vaccine candidates constructed from type 5 adenovirus vector containing full-length viral spike or nucleocapsid protein sequences [35]. Although the above protein analyzing methods are laborious and costly, their outcomes are convincible and sufficient to interpret various biological functions and characteristics of immune organoids. Additionally, it usually supports the genomic-level investigation data since protein synthesis was regulated by genes through the transcription and translational processes, and thus both transcriptomic- and proteomic analyses have mutual correlations that are powerful for biological revelations.

4.3. Morphological features

Organoid comprises the 3D multicellular compartment with complexity like its native tissue, so that the end-point morphological analysis is one of critical parameters to characterize its shape and size, spatial and compositions of multiple cell types, and whole detailed histological structures. Immunofluorescence staining or histochemistry analysis are both familiar to determine morphological characteristics of biological specimens (Fig. 4D). Both staining methods mostly require organoid samples to undergo sectioning steps and the result would represent stratified tissue-like compartments, while the whole-mount staining is considerably done only for small pieces of organoid. Fluorescent conjugated antibodies are used to detect various localized antigens in tissues or cell samples, followed by appropriate microscopy techniques to perform visualization.

The above method has been widely applied for organoid analysis, including the immune organoid. As a particular example, immunofluorescence technique was used to demonstrate the spatial organization of tonsil organoids especially the GC-like structures between unstimulated and LAIV-stimulated group. Based on confocal microscopy visualization of day-4 LAIV-stimulated organoid embedded frozen sections, the dark and light zone were apparently organized through distinctive expression of CD83 and CXCR4 markers in stained B cells that are the indicators of GC formation. This finding suggests critical features in tonsil organoid model to perform [35]. Nevertheless, large-scale screening of morphological and topographical structures of organoid system still remain as a challenge, including the acquisition of high-resolution 3D imaging and low accessibility for in-depth analysis. Ong et al. have recently incorporated the 3D confocal image analysis algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI) to quantify morphological changes at multilevel segmentations of the organoid [132]. This proof-of-concept system also enables the identification of tissue patterning and their roles in organoid micro-niches to construct a single database, which eventually could be a powerful assay for 3D organoid high-throughput screening.

For histochemistry approach, there are several types of tissue section staining depend on target elements, such as Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining, Masson Trichome staining, Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining, and so on. For instance, H&E staining was performed to indicate cellular architectures of spleen organoid unit that appear like the white pulp, red pulp, and trabeculae, which is similar to the normal construct of in vivo spleen [107]. This typical staining was also done in LN organoid to evaluate its organotypic culture, cellular organization, and plasma cell formation [108]. Regardless the types of morphological analyses that are applicable for organoid assessment, imaging technology is inseparable with those techniques in order to provide meaningful information. There is still ample space for improvement to visualize live and fixed organoid to support further applications in disease simulation, regenerative therapy, or drug screening. An automated high-speed 3D organoid imaging platform that enables multi-scale phenotypic characterizations has been recently reported [133]. From an imaging standpoint, this innovation can inspire further research explorations in organoid, including but not limited to immune organoid that are currently restricted only to fluorescence imaging.

5. Challenges and bioengineering solutions

The emergence of immune organoid generation to model and investigate human adaptive immunity is promising not only for translational immunological studies but also for clinical testing of immunotherapeutics. Nevertheless, immune organoid technology is still in the early stages and there are gaps that need to be addressed to enhance their practical use for applications such as immunobiological studies and drug screening. Based on our findings, there are only 7 papers on immune organoid originated from human. Amongst these, 3 are stem cell-derived and 4 are primary donor derived. Various types of organotypic cultures have been established to explore human pathology and disease in vitro, but their integration with immune components that play central role in the mechanism of infections and homeostatic maintenance remains poorly explored. Combining immune organoids with other organoid types will be useful to improve the degree of complexity and their relevance to human physiology. To the best of knowledge, there is no published report on this. Here, potential strategies using a bioengineering approach to improve morpho-physiological functions and address challenges on immune organoids will be described.

5.1. Organoid architecture

Poorly controlled multicellular self-organization is a major limitation of mini organs resulting in high heterogeneity of organoids with their architecture differing from their corresponding organs. This phenomenon also causes stochastic end-point morphology and physiological functions, suggesting that the efforts to reduce this variability and enhance reproducibility are necessary for basic and translational organoid research [137]. Several techniques have been employed to address these issues. For instance, scaffold-guided organoid morphogenesis can be achieved microfabrication to better control structural organization and size range of organoids. A type I collagen hydrogel-containing microfluidic chip with microcavities was constructed to mimic the native crypt geometry during intestinal organoid culture [138]. The same research group further optimized a photopatterning of synthetic hydrogel mechanics that has been favourable for fine-tuning intestinal stem cell growth and differentiation into intestinal organoids [139]. Both findings are a proof-of-concept for specific tissue-oriented topographical scaffold that guides the organoid architecture similar to that in vivo. Cell–ECM interactions are also important features to promote organotypic structures and most organoid generation protocols rely on naturally derived basement matrix (e.g., Matrigel) or synthetic polymer like polyethylene glycol (PEG) which lack naturally occurring cell adhesion motifs.

Chen et al. developed a Matrigel-free method to generate brain organoids using 3D printed PDMS microwell array coated with coating materials including poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether (mPEG), lipidure and bovine serum albumin (BSA) [140]. Their results demonstrated that both optimum surface coating material and device geometry are vital for organoid generation, and thus this work underlying microfabrication technology could pave the way to develop wide variety of organoids in ECM-free conditions. Another study has been recently reported the use of defined alginate hydrogels to support a Matrigel-free spinal cord organoid culture [141]. It was found that alginate encapsulation could reduce organoid size variability and support gliogenesis and neurogenesis in spinal cord organoids with similar efficiency to Matrigel-based organoid generation. Both studies could inspire a xeno-free culture system of other organoid types, including immune organoid. It is crucial to understand that the choice of biomaterial to construct organoids can reduce their translational potential, increase batch-to-batch variations, and heighten the risks of immunogenicity (for organoid transplants to replace in vivo organ), and should be an important consideration depending on the applications.

3D bioprinting has also been used for reconstructing organoids as it allows the design and selective cell distribution, cytokines, and bioactive molecules to form specific tissues and organ models. For example, cardiac organoids were made in a freeform embeddable collagen hydrogel suspension with a 3D bioprinting technique and it precisely reflects the anatomical structures of heart [142]. Genetic engineering approach could also provide different idea to improve the organoid research other than these technical bioengineering attempts. Recently, Legnini et al. proposed an optogenetic perturbations with spatial transcriptomics to control cellular reprogramming and tissue patterning in neural organoids [143]. This sophisticated technique could give future insights to combine it with other bioengineering methods and thus can dynamically improve the functionalities of organoids.

To the best of our knowledge, there has yet to be any bioengineering approaches to improve the generation of immune organoids. In addition, most established lymphoid tissue-derived immune organoids focus more on characterizations of their physiological functions, while the morphological aspects are poorly investigated. It might be due to the cellular reaggregation technique that was commonly used to form organoids based on primary cell culture, such as tonsil-, LN-, and thymic organoid — implying that their architectural structure is not as firm or stable like the corresponding tissue, thus limiting their morphological explorations and analysis. This remaining facet can be one of the promising cues to direct immune organoid development in the future, especially to advance its morphogenesis which is more accessible for downstream analyses.

Previous findings in bioengineered organoid will help advance immune organoid culture, as illustrated in Fig. 5A. It will be desirable to develop such a multifunctional biocompatible matrix to replace Matrigel for human immune organoid culture with physiologically relevant levels and control the spatial organoid architecture simultaneously. It can be further integrated with microwell platform to generate the immune organoid in uniform size and shape. 3D bioprinting technology or optogenetic regulation approach may also be tested. 3D bioprinting method might be useful to modulate immune organoid cellular compositions including the maturation levels, as it would allow design and spatial positioning of multiple cell types. Optogenetic system is extensively used for human iPSC-based organoid to control cell fate and differentiation and thus, it is worthwhile to explore its potential for patterning patient-derived organoids with light-inducible protein cues.

Fig. 5.

Overcoming challenges and future directions on immuno-engineered organoids. Bioengineering approaches for the improvements in (A) organoid architecture and (B) vascularization and maturation levels. (C) A fusion of immune-, cancer-, and blood vessels organoid to form in vitro assembloid model that can reorchestrate tumour microenvironment. (D) A chip-driven immunological model to mimic the whole adaptive human immune system in an in vitro fashion. Multiple types of immune organoids were grown in an integrated microfluidic device to see their synergistic functions in acquiring immune sentinels.

5.2. Organoid vasculature and maturation