Summary

Accurate, non-invasive, and cost-effective tools are needed to assist pulmonary nodule diagnosis and management due to increasing detection by low-dose computed tomography (LDCT). We perform genome-wide methylation sequencing on malignant and non-malignant lung tissues and designed a panel of 263 differential DNA methylation regions, which is used for targeted methylation sequencing on blood cell-free DNA (cfDNA) in two prospectively collected and retrospectively analyzed multicenter cohorts. We develop and optimize an integrative model for risk stratification of pulmonary nodules based on 40 cfDNA methylation biomarkers, age, and five simple computed tomography (CT) imaging features using machine learning approaches and validate its good performance in two cohorts. Using the two-threshold strategy can effectively reduce unnecessary invasive surgeries, overtreatment costs, and injury for patients with benign nodules while advising immediate treatment for patients with lung cancer, which can potentially improve the overall diagnosis of lung cancer following LDCT/CT screening.

Keywords: pulmonary nodules, plasma cell-free DNA, methylation model, risk stratification, low-dose computed tomography

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

A concise methylation biomarker panel can non-invasively classify pulmonary nodules

-

•

The methylation model outperforms clinical tools in classifying pulmonary nodules

-

•

Five simple CT features and age significantly improve the diagnostic performance

-

•

Two-threshold strategy enables accurate risk stratification of pulmonary nodules

Liang et al. present an integrated model consisting of 40 lung-cancer-specific cfDNA methylation markers, one clinical feature, and five CT imaging features for non-invasively accurate diagnosis and management of pulmonary nodules. The two-threshold strategy of the model can reduce unnecessary invasive surgeries and improve the overall diagnosis of lung cancer.

Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide, as many as around 1.8 million in 2020.1 Though many advances in therapies and treatments have been made in lung cancer, an overall 5-year survival rate is only 10%–20% in different countries,2 because most lung cancers are at advanced stages and not curable when they are first diagnosed.3 Early detection and treatment are the most effective ways to reduce the mortality of cancers. For lung cancer, adenocarcinoma in situ and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (i.e., stage 0) have 100% 10-year survival rate, stage IA to IB have 92%–68% 5-year survival rate, while it drops to 36% and 10% for stage III and IV.3,4 The advent of low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) for tumor detection had been proved to alter the landscape of lung cancer screening and reduce about 20% mortality from lung cancer in high-risk populations.5,6

Millions of pulmonary nodules are detected annually due to high-sensitivity LDCT, which has been widely adopted for lung cancer screening, but only less than 5% pulmonary nodules are malignant,7,8 making this method meeting a challenge on how to accurately assess malignant risk in such a large number of pulmonary nodules, particularly in small-sized nodules and stage I nodules, which compose more than half of all nodules screened by LDCT.9,10 On the other hand, patients screened for pulmonary nodules are often anxious and may undergo excessive physician examinations or tissue biopsies, causing unnecessary pulmonary injury and fiscal waste.11 In order to reduce invasive diagnostic injury and overtreatment, cancer risk estimation methods are recommended before invasive approaches. The Mayo Clinic, Brock, Veterans Affairs (VA), and Herder clinical models are commonly used for pulmonary nodule risk prediction based on lung cancer risk factors, such as age, smoking history, and cancer history and computed tomography (CT) imaging features including nodule diameter, morphology, and locations.12,13 However, their accuracies vary from 0.6 to 0.9 in different populations composing of different disease stages and races. Some studies reported that about 30%–40% of benign nodules existed in those with high suspicion of malignancy based on imaging and clinical judgment.14 Therefore, the accuracy of lung cancer risk prediction methods still needs to be improved.

Aberrant DNA methylation pattern in tumor tissues is one of the leading characteristics of most cancers.15 Furthermore, DNA methylation patterns in some genes are correlated with different histological stages and can serve as hallmarks during cancer progression, particularly for indication of the early molecular events of tumor initiation.16,17

Liquid biopsy allows a minimally invasive method for molecular characterization of cancers for diagnosis, patient stratification to therapy, and longitudinal monitoring.18 With the improvement of the next-generation sequencing technology, tumor cell-shed abnormal DNA methylation signals can be detected from plasma cell-free DNA (cfDNA) in blood samples by deep sequencing.19 Nowadays, cfDNA methylation test has been widely accepted as a promising ultrasensitive and non-invasive method for early cancer detection, including lung cancer. Our previous study reported a 100-feature cfDNA methylation model (PulmoSeek) with a superior performance in accurately distinguishing malignant pulmonary nodules from benign nodules, compared with positron emission tomography (PET)-CT and two clinical prediction models (Mayo Clinic and VA).20 We also reported that a combination of CT imaging biomarkers with the 100 cfDNA methylation markers (PulmoSeek Plus model) improved the PulmoSeek model performance by 0.05 in the area under the curve (AUC) of receiver operating characteristic.21 However, different radiologists usually give different CT imaging feature extraction results and may introduce variations for biomarkers of the model in different hospitals, which made its standardization difficult and impeded its clinical accessibility.

In this study, we developed a concise cfDNA methylation marker panel distinct from that in our prior publications20,21 using different computational approaches. We optimized the cfDNA methylation marker model integrated with six common lung cancer risk factors, including age and five easily accessible CT imaging features, for identifying malignant nodules from screening individuals in a prospective multicenter cohort, and validated its performance in an independent and prospective multicenter cohort, with the aim to improve the robustness and accessibility of the risk prediction model in clinical practice, beyond accuracy.

Results

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics

In total, we included 963 participants with 5–30 mm pulmonary nodules from two multicenter cohorts (n = 620, NCT03181490; n = 343, NCT03651986) (Table 1; Figure 1). The two cohorts were the same as previously reported in our former studies.20,21 However, there was no overlap between the participants in this study and those in the previous studies as they were enrolled in separate dates sequentially. In this study, the patients in the development cohort and the external validation cohort were at a median age of 53.0 [18.0, 85.0] and 54.0 [18.0, 84.0] and were composed of 44.8% and 52.5% females, respectively. Never smokers (71.6% and 74.6%) and patients with small pulmonary nodules (70% and 78.1%, ≤ 20 mm in diameters), non-solid nodules (51.8% and 59.2%), and without family history of lung cancer (94.5% and 93.3%) were predominant in the two cohorts, respectively. The pathological-confirmed malignant nodules accounted for 69.5% and 67.1% in the two cohorts, simulating the proportion of benign nodules existing in the nodules with high-suspicion malignancy based on imaging and clinical judgment.14 The main proportion of malignant nodules was adenocarcinoma (65.0% and 61.2%) and at an early stage (0-I, 93.5% and 94.4%), respectively. The benign nodules were mainly composed of inflammation (12.9% and 11.1%), tuberculosis (3.1% and 4.4%), and hamartoma (3.5% and 2.9%), respectively.

Table 1.

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohorts used in this study

| Subjects | Development cohort (N = 620) | External validation cohort (N = 343) | Overall (N = 963) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age – yr | |||

| Mean (SD) | 52.7 (11.6) | 54.3 (10.3) | 53.3 (11.2) |

| Median (Min, Max) | 53.0 (18.0, 85.0) | 54.0 (18.0, 84.0) | 54.0 (18.0, 85.0) |

| Gender – n (%) | |||

| M | 342 (55.2%) | 163 (47.5%) | 505 (52.4%) |

| F | 278 (44.8%) | 180 (52.5%) | 458 (47.6%) |

| Smoking history – n (%) | |||

| Never smoker | 444 (71.6%) | 256 (74.6%) | 700 (72.7%) |

| Former smoker | 59 (9.5%) | 22 (6.4%) | 81 (8.4%) |

| Smoker | 117 (18.9%) | 65 (19.0%) | 182 (18.9%) |

| Family history of lung cancer – n (%) | |||

| No | 586 (94.5%) | 320 (93.3%) | 906 (94.1%) |

| Yes | 34 (5.5%) | 23 (6.7%) | 57 (5.9%) |

| Nodules | |||

| Size – n (%) | |||

| 5–10 mm | 142 (22.9%) | 106 (30.9%) | 248 (25.8%) |

| 10–20 mm | 292 (47.1%) | 162 (47.2%) | 454 (47.1%) |

| 20–30 mm | 186 (30.0%) | 75 (21.9%) | 261 (27.1%) |

| Location – n (%) | |||

| Right upper lobe | 153 (24.7%) | 84 (24.5%) | 237 (24.6%) |

| Right middle lobe | 102 (16.5%) | 56 (16.3%) | 158 (16.4%) |

| Right lower lobe | 203 (32.7%) | 102 (29.7%) | 305 (31.7%) |

| Left upper lobe | 55 (8.9%) | 28 (8.2%) | 83 (8.6%) |

| Left lower lobe | 107 (17.3%) | 73 (21.3%) | 180 (18.7%) |

| Type – n (%) | |||

| Ground-glass opacity | 111 (17.9%) | 84 (24.5%) | 195 (20.2%) |

| Part solid | 210 (33.9%) | 119 (34.7%) | 329 (34.2%) |

| Solid | 299 (48.2%) | 140 (40.8%) | 439 (45.6%) |

| Histopathology | |||

| Benign – n (%) | 189 (30.5%) | 113 (32.9%) | 302 (31.4%) |

| Inflammation | 80 (12.9%) | 38 (11.1%) | 118 (12.3%) |

| Tuberculosis | 19 (3.1%) | 15 (4.4%) | 34 (3.5%) |

| Hamartoma | 22 (3.5%) | 10 (2.9%) | 32 (3.3%) |

| Other | 68 (11.0%) | 50 (14.6%) | 118 (12.3%) |

| Malignant – n (%) | 431 (69.5%) | 230 (67.1%) | 661 (68.6%) |

| Small cell | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (0.2%) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 403 (65.0%) | 210 (61.2%) | 613 (63.7%) |

| Squamous cell | 16 (2.6%) | 7 (2.0%) | 23 (2.4%) |

| Other | 11 (1.8%) | 12 (3.5%) | 23 (2.4%) |

| AJCC stage | |||

| 0 | 21 (4.9%) | 11 (4.8%) | 32 (4.8%) |

| I | 382 (88.6%) | 206 (89.6%) | 588 (89.0%) |

| II | 11 (2.6%) | 3 (1.3%) | 14 (2.1%) |

| III | 12 (2.8%) | 5 (2.2%) | 17 (2.6%) |

| IV | 1 (0.2%) | 4 (1.7%) | 5 (0.8%) |

| Unknown | 4 (0.9%) | 1 (0.4%) | 5 (0.8%) |

yr, year; mm, millimeter; n and N, number of participants.

Figure 1.

Framework of model development and validation

In the discovery phase, to identify diagnostic methylation markers as well as a multi-marker methylation panel, the DNA methylation levels were measured in 128 fresh frozen tissue samples, including 52 lung cancer tissues, 16 adjacent normal tissues, and 60 benign tissues, using a genome-wide platform of more than 3,000,000 CpG sites in a cohort of 112 subjects from 3 hospitals. A methylation panel of 263 differentially methylated regions (DMRs) were created using a stepwise statistical feature selection procedure. Resected tissues from 64 patients (44 malignant and 20 benign) with high-risk pulmonary nodules were used to validate the methylation panel. In the model development and internal validation phase, we enrolled a prospective cohort of 623 participants including 433 malignant and 190 benign plasma samples from 10 hospitals in 2017–2019 (NCT03181490). Three samples were failed in bioinformatics QC. The remaining 620 samples were divided into a model development sub-cohort containing 236 malignant and 105 benign samples at five randomly selected hospitals, and an internal validation sub-cohort containing 194 malignant and 85 benign samples from the remaining five hospitals. A 40-marker methylation panel was finally decided. In the external validation phase, a prospective cohort of 345 participants from 18 hospitals in 2018–2020 (NCT03651986) was enrolled to independently validate the performance of the methylation model. Two samples were failed in bioinformatics QC. The remaining 231 malignant and 112 benign samples were included finally. See also Figure S1 and Table S1.

Differential DNA methylation biomarker discovery and validation

By comparing the genome-wide methylation profiles of malignant tissues with those of adjacent normal tissues and benign tissues, we were able to identify 28,052 differentially methylated regions (DMRs), of which 16,223 were hypomethylated and 11,829 were hypermethylated. As shown in Figure S1A, the DMRs clearly separated malignant tissues from adjacent normal tissues and benign tissues irrespective of smoking history or histological type. After a series of filtering process as described in the STAR Methods, a total of 263 DMRs spanning 79,872 bp of the human genome and covering 6,869 CpG sites were selected to be included in a targeted methylation panel (Table S2). Prior to being employed in the cfDNA samples, the targeted panel was validated using independent tissue samples, comprising 20 benign and 44 malignant tissues. As expected, the methylation profiles of malignant and benign tissues were apparently separated (Figure S1B). Moreover, we inspected the methylation patterns of the CpG sites located at these 263 DMRs in patients with lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov) and revealed that they clearly separated tumor from normal samples in both cohorts irrespective of smoking history either, which further demonstrates the discriminative ability of the DMRs we selected (Figures S2A and S2B). Collectively, these findings indicated that we developed a compact customized panel of 263 DMRs, which showed high accuracy and reliability in classifying malignant tissue samples from pulmonary nodules.

To further reveal the functional relevance of the methylation markers with lung cancer biology, we conducted some functional explorations. First, we examined the enriched canonical pathways for the genes located at those 28,052 DMRs using Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Reactome databases. A total of 97 and 55 pathways were significantly enriched in KEGG and Reactome databases, respectively (false discovery rate <0.05). In KEGG, the top enriched pathways included pathways that are directly related to cancer, such as proteoglycans in cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma (Figure S2E). In addition, signaling transduction pathways associated with cancer initiation and progression, such as Rap1 signaling pathway, mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, Ras signaling pathway, and others, were also significantly enriched (Figure S2E). Similarly, in Reactome, among the top enriched pathways, in addition to the neuron system, most of them also play essential roles in cancer, such as the GTPase cycles of RHO, RHOA, RHOB, RHOC, CDC42, and RAC1; O-linked glycosylation; extracellular matrix organization; and others (Figure S2F). Next, since we had narrowed down the methylation markers into a concise panel of 263 DMRs, we inspected the expression profiles of the genes overlapping these DMRs in an independent lung adenocarcinoma patient cohort from the TCGA dataset. Differential expression analysis revealed that 80 (41.5%) of these genes were differently expressed between tumors and normal tissues (Figure S2G), indicating that a considerable proportion of these selected methylation markers played essential roles in tumor transcriptional dysregulation. Collectively, these results suggested that the DMRs we identified played essential roles in the initiation and progression of lung cancer.

A cfDNA-methylation model performance

Given that we had designed a customized panel and validated its discriminative ability using independent in-house pulmonary nodule tissue samples and external lung cancer patient cohorts from the TCGA project, we then investigated whether the selected methylation markers could non-invasively classify pulmonary nodules. Consequently, we performed targeted methylation sequencing on cfDNA from plasma samples in a prospective multicenter cohort (NCT03181490) of 623 participants with 5–30 mm pulmonary nodules from 10 hospitals in China. Principal component analysis showed there were no hospital-specific features based on plasma cfDNA sequencing of the customized panel (Figures S3A and S3B). As previously mentioned, the participants were split into two groups: a training set (n = 341) and an internal validation set (n = 279). For 66 out of 341 training set patients, as we obtained the methylation profiles on both the plasma and tissue samples, we assessed the association between plasma cfDNA methylation and tissue DNA methylation and revealed a significant positive correlation (Pearson’s correlation = 0.4, p = 2.1 × 10−11) between them (Figure S3C). This suggests that our methylation panel can capture tumor-tissue-derived DNA methylation signals in circulating tumor DNA, which we believe is essential for developing a highly sensitive and specific test for non-invasively classifying pulmonary nodules.

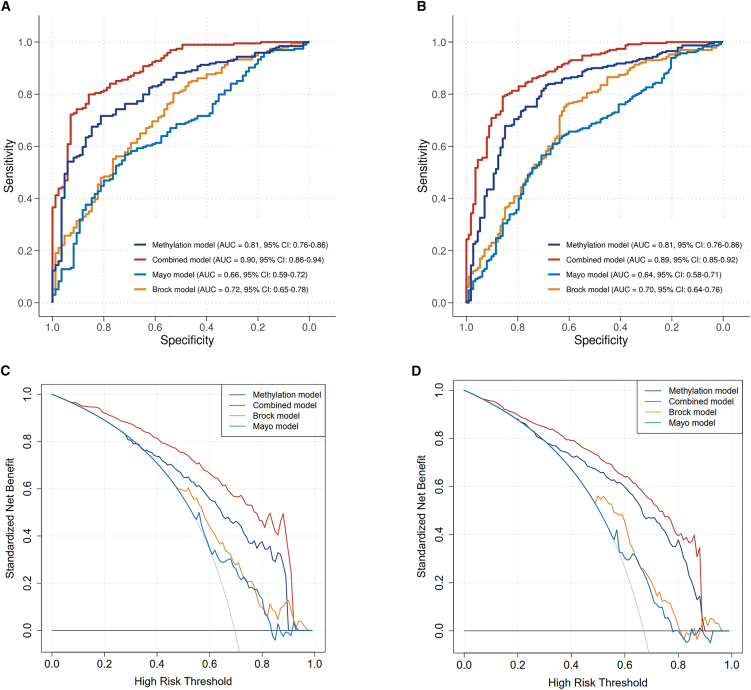

After a multistep process of feature selection (see the STAR Methods), we eventually obtained a minimum set of 40 methylation markers (Table S2) to build a stable and generalizable model in the training cohort (236 malignant vs. 105 benign). The CpG sites located at the 40 DMRs could also distinguish patients with lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma from normal samples in the TCGA project (Figures S2C and S2D). Although less distinct than in tissue samples, these markers still showed notably different cfDNA methylation patterns between malignant- and benign-nodule plasma samples in both the training cohort and the internal validation cohort (Figures 2A and 2B). We then fit a logistic regression model using these 40 methylation markers in the training cohort and validate the performance in the internal validation cohort (194 malignant and 85 benign) (Figure 3A). Compared to the conventional Mayo Clinic model and Brock model regularly used for risk prediction of lung cancer in Western clinics,22,23 our methylation model exhibited superior performance in discriminating malignant from benign nodules in the internal validation cohort, yielding an AUC of 0.81 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.76–0.86), compared with the AUC of 0.66 (95% CI: 0.59–0.72) (p = 0.0004) for the Mayo Clinic model and 0.72 (95% CI 0.65–0.78) (p = 0.03) for the Brock model (Figure 3A).

Figure 2.

Heatmap of differential methylation signatures between malignant and benign pulmonary nodule subjects in the training and validation cohorts

(A) The training cohort.

(B) The internal validation cohort.

(C) The external validation cohort. See also Tables S1, S2, and Figure S2.

Figure 3.

The combined model integrating methylation signatures, one clinical feature, and five imaging features showed superior performance than the methylation model and the two clinical models. p value lower than 0.05 indicates significant when comparing the difference of AUCs between two models

(A) AUC curves in the internal validation cohort.

(B) AUC curves in the external validation cohort.

(C) Decision curve in the internal validation cohort.

(D) Decision curve in the external validation cohort. AUC, area under the curve. See also Table S1 and Figure S4.

To further evaluate the methylation model performance, we used an independent prospective specimen collection and a retrospective masked analysis cohort as an external validation cohort (NCT03651986, 231 malignant vs. 112 benign from 18 hospitals in China) (Table S1). The cfDNA methylation profiles in the external validation cohort exhibited similar methylation signal patterns as those in the training cohort and internal validation cohort (Figure 2C). The AUC of the methylation model in the external validation cohort also achieved 0.81 (95% CI: 0.76–0.86), again significantly higher than the estimates of 0.64 (95% CI: 0.58–0.71; p < 0.0001) for the Mayo Clinic model and 0.70 (95% CI: 0.64–0.76; p = 0.006) for the Brock model (Figure 3B).

We conducted covariate analyses to determine whether demographic factors such as sex, age groups, and smoking status or pulmonary nodule features like nodule size and type, as well as pathological type, affected the methylation model’s performances. We discovered that none of them had a significant impact on the model’s performances (DeLong’s test, p > 0.05, Figures S4A–S4F). These findings indicated that our methylation model’s performances remained robust regardless of patient or nodule characteristics.

A combined model improving performance

Many studies proved that clinical factors (such as age, smoking, and family history of cancers) and radiological features (such as spiculation, lobulation, spinous, blood vessel convergence, etc.) were closely related to lung cancer.21,24 However, radiological features are not unified or easily obtained in clinical practice due to the varying experience of radiologists and various CT instruments and parameters used in different hospitals. Whereas, age and some objective CT imaging features such as long diameter, short diameter, nodule size (a quantity of the size of a nodule defined as the long diameter multiplied by the short diameter.), nodule types based on density (i.e., solid nodules [SNs], partial SNs, ground-glass opacity), and mean nodule attenuation value are easily obtained from routine CT examination, and a large quantity of research has shown their correlations with the risk of malignancy of pulmonary nodules. We therefore integrated these 6 factors with the risk score of the methylation model to form a combined model. The combined model significantly improved the AUC to 0.90 (95% CI: 0.86–0.94) in the internal cohort and 0.89 (95% CI: 0.85–0.92) in the external validation cohort, with increases of 0.09 and 0.08 in AUC (95% CI 0.05–0.12, p < 0.0001; 95% CI 0.04–0.11, p < 0.0001), respectively, compared with the methylation model (0.81, 95% CI: 0.76–0.86) (Figures 3A and 3B). In addition, covariate analyses showed that the combined model maintained consistently high performances irrespective of patient or nodule characteristics (Figures S4G–S4L).

Next, decision curve analysis (DCA) was used to facilitate the comparison between different prediction models. It can reflect the range of valuable risk threshold probabilities and the magnitude of net benefit to do treatment on the patients with risk scores higher than a certain threshold. The net benefit is a weighted combination of true and false positives, where the weight is derived from the threshold probability. The curve for treat none is fixed at a net benefit of 0. The curve for treat all crosses the y axis and the line of treat none at the malignant prevalence.25,26 In this analysis, the combined model provided a larger net benefit than the methylation model alone and the two clinical models nearly across almost all threshold probabilities (Figures 3C and 3D), except for the threshold values between 0.92 and 0.97 in the internal validation set (Figure 3C) and 0.89 and 0.96 in the external validation set (Figure 3D), where the Brock model had slightly higher net benefits than the combined model. For instance, in the external validation set, if to consider an invasive procedure for a patient with a risk score more than the threshold of 0.40, the combined model would provide a standardized net benefit of 79.1% (Figure 3D), which means the model could correctly identify approximately 79 individuals with malignant nodules from 100 people with lung cancer. At the same risk threshold, the methylation model would only provide a standardized net benefit of 72.6% and the Mayo Clinic and Brock models would both provide a benefit of 67.2%, corresponding to correctly identifying approximately 73 individuals with malignant nodules for the methylation model and 67 individuals with malignant nodules for the Mayo Clinic and Brock model in 100 people with lung cancer (Figure 3D). These findings indicated that the combined model can serve as a clinically useful tool for the management of pulmonary nodules.

Finally, to identify benign lung nodules and reduce the number of invasive procedures, a high sensitivity and a high negative predictive value are required to rule out lung cancer confidently; hence, the specificity is typically 30%–55%.14,21 We fixed the specificity at a moderate level of 50% and compared the sensitivities across different predictive models. The findings indicated that across both the internal validation cohort and the external validation cohort, the combined model exhibited the highest performance, followed by the methylation model in second place, the Brock model in third place, and the Mayo Clinic model performing least effectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Performance metrics of the Mayo Clinic model, Brock model, methylation model, and combined model in internal and external validation cohorts

| Internal validation set |

External validation set |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brock model | Mayo Clinic model | Methylation model | Combined model | Brock model | Mayo Clinic model | Methylation model | Combined model | |

| AUC | 0.72 (0.65–0.78) | 0.66 (0.59–0.72) | 0.81 (0.76–0.86) | 0.90 (0.86–0.94) | 0.70 (0.64–0.76) | 0.64 (0.58–0.71) | 0.81 (0.76–0.86) | 0.89 (0.85–0.92) |

| Specificity | 0.51 (0.45–0.56) | 0.51 (0.45–0.56) | 0.51 (0.45–0.56) | 0.51 (0.45–0.56) | 0.50 (0.45–0.56) | 0.50 (0.45–0.56) | 0.50 (0.45–0.56) | 0.50 (0.45–0.56) |

| Sensitivity | 0.81 (0.76–0.85) | 0.69 (0.63–0.74) | 0.88 (0.84–0.91) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 0.81 (0.76–0.85) | 0.69 (0.64–0.73) | 0.90 (0.86–0.93) | 0.95 (0.92–0.97) |

| Accuracy | 0.72 (0.66–0.77) | 0.63 (0.57–0.69) | 0.77 (0.71–0.81) | 0.83 (0.78–0.87) | 0.71 (0.66–0.75) | 0.63 (0.57–0.68) | 0.77 (0.72–0.81) | 0.80 (0.76–0.84) |

| PPV | 0.79 (0.74–0.83) | 0.76 (0.71–0.81) | 0.80 (0.75–0.85) | 0.82 (0.77–0.86) | 0.77 (0.72–0.81) | 0.74 (0.69–0.78) | 0.79 (0.74–0.83) | 0.80 (0.75–0.84) |

| NPV | 0.54 (0.48–0.60) | 0.41 (0.36–0.47) | 0.65 (0.59–0.71) | 0.90 (0.85–0.93) | 0.56 (0.51–0.62) | 0.44 (0.39–0.49) | 0.71 (0.66–0.76) | 0.84 (0.80–0.87) |

| NPV at 10% prevalence | 0.96 (0.93–0.98) | 0.94 (0.90–0.96) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.96 (0.93–0.98) | 0.94 (0.90–0.96) | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 0.99 (0.97–1.00) |

| NPV at 20% prevalence | 0.91 (0.88–0.94) | 0.87 (0.82–0.90) | 0.94 (0.91–0.97) | 0.99 (0.97–1.00) | 0.91 (0.88–0.94) | 0.87 (0.83–0.90) | 0.95 (0.92–0.97) | 0.98 (0.95–0.99) |

Data presented as estimate (95% CI). AUC, area under the curve; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

Two-threshold strategy for accurate risk stratification of pulmonary nodules by the combined model

Pulmonary nodule risk assessment is not a simple binary classification. Often, a three-class classifying system, based on malignancy risk thresholds, is recommended by guidelines.27,28 Therefore, we established a two-threshold strategy for risk stratification of pulmonary nodules by the combined model. In detail, we defined a lower probability threshold of 0.22 with 98% sensitivity (to avoid missing detection of malignant nodules) and a higher probability threshold of 0.94 with 90% specificity (to avoid misclassifying benign nodules as “high risk”), to classify pulmonary nodules into low-risk (risk score <0.22), intermediate-risk (risk score 0.22–0.94), and high-risk (risk score ≥0.94) groups. As the combined model displayed consistent performances in two validation cohorts, probability thresholds were derived for the combined internal validation and external validation dataset (n = 622). Predicted probabilities of the combined model and the resulting thresholds are shown in Figure 4A. By using the two-threshold stratification strategy, 49.7% of total validation individuals were classified as high risk and would be recommended to have direct surgery or invasive biopsy; 15.6% of individuals were classified as low risk and suggested to have routine LDCT surveillance; and 34.7% of individuals were classified as intermediate risk, who would be assigned to active LDCT surveillance (Figure 4B). Using the low-risk group in a rule-out strategy yielded a sensitivity of 98.1% (n = 416/424) and a negative predictive value of 91.8% (n = 89/97). Using high-risk class for a rule-in strategy yielded a specificity of 90.4% (n = 179/198) and a positive predictive value of 93.9% (n = 290/309) (Figure 4B). Such decision-making strategy could reduce 90.4% (n = 179/198) unnecessary invasive biopsies and surgeries (for low and intermediate risk, which is not suggested to undergo surgery immediately) on the whole (Figure 4C). Only 1.9% (n = 8/424) of malignant nodules classified to the low-risk group and 9.6% (n = 19/198) of benign nodules classified to the high-risk group were incorrectly classified, which might fall into the standard surveillance procedures or undergo invasive surgeries (Figure 4C). These findings suggest that the three-class classifying system provided by the combined model holds promise for the accurate risk stratification of pulmonary nodules.

Figure 4.

Two-cutoff strategy for risk stratification used in the combined model helps clinical decisions

(A) Risk score distribution and stratification of pulmonary nodules by the combined model in different cohorts.

(B) Risk stratification in the combined cohorts.

(C) Reclassification of the combined model on subsequent clinical decisions. Sp, specificity, Se, sensitivity. See also Table S1.

Discussion

It has been widely accepted that early screening, diagnosis, and treatment at an early stage are the most effective approaches for improving long-term survival of lung cancer. Highly sensitive, accurate, robust, and cost-effective screening strategies and tools are needed and are being actively explored. The first-generation screening tools are radiological methods.29 Since the introduction of LDCT screening from 2002 when the National Lung Screening Trial started, it remarkably improved pulmonary nodule detection efficiency and led to a nodule detection rate of around 20% on the prevalence screen in different countries or areas with different recruitment criteria.5,6,29 Due to the high sensitivity (90%) of LDCT, there were millions of small-size nodules detected (80% of 5–10 mm).29 However, only about 3.6% nodules were malignant.5,8 On the other hand, for pulmonary nodules being predicted to be high risk of malignancy, there were approximately 20% nodules after surgery and even as high as 38% nodules after invasive-biopsy diagnosis being confirmed to be benign, which led to overtreatment and patients’ psychological and physical burden.30,31 Therefore, exploring feasible strategies and tools for accurately distinguishing malignant nodules and simultaneously preventing overtreatment becomes an increasingly urgent issue that needs to be addressed in clinical practice.

To date, the majority of cancer risk estimation methods developed are based exclusively on clinical risk factors, imaging technology, or molecular markers. Some commonly used risk predictors, including the Mayo Clinic, Brock, VA, and Herder clinical models, were only composed of lung cancer risk factors, such as age, smoking history, cancer history, and CT imaging factors or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), among others. These models showed variable risk prediction accuracy, with AUCs from 0.6 to 0.9 in different populations.12 In our cohort study, the AUCs of the Mayo Clinic and Brock clinical models in two validation cohorts were only 0.64–0.66 and 0.70–0.72, respectively (Figure 3). Even PET/CT, a common imaging technique and clinically valuable tool in cancer diagnosis by detecting abnormal levels of cellular metabolism, was also reported not to perform well in assessing small-size (<10 mm) pulmonary nodules by PET/CT imaging alone.12 Therefore, classifying pulmonary nodules only based on clinical and imaging factors has a large deviation from the practical needs, and the accuracy of lung cancer risk prediction methods still needs to be improved.

Molecular biomarkers were then developed to improve the accuracy of the risk prediction. A 13-protein biomarker panel-based blood test was first developed and proved to reduce 32% invasive procedures for benign nodules by comparing with physician decisions according to the clinical guidelines.32 DNA genetic biomarkers based on SNPs and motifs of cfDNA fragments and DNA methylation biomarkers were also developed for early cancer detection. DNA methylation biomarkers were proved superior to the genetic risk scores based on SNPs identified from genome-wide association studies based on a 1,600-patient cohort study, with AUCs of 0.777 and 0.587, respectively.33 A PCR-based six-methylation-marker panel achieved an AUC of 0.797 for stage I and 0.830 for stage I and II non-small cell lung cancer in a European retrospective cohort with 683 high-risk individuals.34 Single gene’s methylation alteration was also attempted for lung cancer detection. For example, SHOX2 gene promoter methylation alteration in blood showed a sensitivity of 60% and specificity of 90% in the diagnosis of lung cancer.35 PTGER4-combined SHOX2 DNA methylation alterations could distinguish malignant and nonmalignant lung disease with an AUC value of 0.88.36 RASSF1A aberrant methylations frequently occur in small-cell lung cancer.37 However, these reports were retrospective studies based on small populations and need to be evaluated in large and prospective clinical trial studies, especially for early-stage lung cancer trial studies. Moreover, lung cancer is a highly heterogeneous disease. A few biomarkers might not be enough to represent the majority of lung cancer populations across complex and diverse genetic backgrounds. In this study, using different computational approaches, we selected 263 DMRs between malignant and benign pulmonary nodules. The subset of 40 DMRs was finally determined in the targeted cfDNA methylation panel for the discrimination of malignancy and benign conditions. These DMRs have almost no overlap (only 2 regions) with our previously reported DMRs identified in persons at the highest risk of having a malignant nodule.20,21 Thus, this report has a significantly different concise methylation panel. The exact genes and regions that are tested in the 263 DMRs and 40 DMRs subset are presented in Table S2, which contain several genes previously reported for lung cancer diagnosis, including SHOX2, PTGER4, and CDO1, in addition to some unreported genes. Most DMRs of these genes are located in the gene body and 6 out of 40 DMRs are in intergenic regions. These genes may play roles in the regulation of lung cancer-related gene and proximal gene expression, which calls for further investigation.

Tumor size, tumor morphology, smoking history, age, and some lung diseases are risk factors of lung cancer according to clinical guidelines. Many studies reported that the integration of risk factors with molecular biomarkers significantly improved the performance of risk classifiers. The integration of two plasma protein biomarkers (LG3BP and C163A) with the validated risk models (Mayo Clinic and VA) significantly improved the AUC from 0.69 and 0.60 to 0.76, which was also superior to PET and physician assignments.24 The risk factors of age, gender, smoking status, quit years, pack-years, and COPD together yielded an AUC of 0.852. Adding six methylation biomarkers significantly increased the AUC to 0.942.34 In this study, using different participants and their biosamples from two previously reported multicenter cohorts,20,21 we developed a blood-based risk prediction model by integrating 40 cfDNA methylation markers and the six risk factors, which can be easily obtained from CT reports, for distinguishing malignant from benign nodules. We internally and externally validated its good performance in two prospective multicenter clinical trial studies, respectively. The first highlight of this study was the combination of six common lung cancer risk factors with cfDNA methylation markers, which significantly improved the performance of the model, with ∼36.9% and ∼25.4% increase of AUC when compared with the Mayo Clinic and Brock model (p < 0.0001). These six factors are easily obtained from CT examination. Thus, the integrated model is much suitable to extend its accessibility in clinical practice. Second, our cfDNA methylation model and combined model have higher accuracy compared with the Mayo Clinic and Brock clinical models, which are commonly used by physician. The two clinical models were established based on the Western population with the major composition of older patients (average age >60 years) and smokers (including current smokers and former smokers) with SNs.12,22,23 However, the epidemiological characteristics and clinical behaviors of Chinese patients with pulmonary nodule and lung cancer are quite different from those of the Caucasian population, with more non-smokers (67.6%), more younger females (33.3% vs. 23.2% of males under 50 years old), and a higher prevalence of adenocarcinoma (92.2%) reported in lung cancer screening studies in China.10,38 The cohort composition of this study is in accordance with Chinese reports: 72.7% (700 out of 963) of participants were never smokers, and 92.7% (613 out of 661) of participants with malignant nodules were diagnosed with adenocarcinoma (Table 1). Therefore, the 40 DMRs and risk factors established on Chinese lung cancer epidemiological characteristics had better performance on Chinese patients than the Mayo Clinic and Brock clinical models did. Notably, our DMRs had similar performance in identifying high risk of malignant nodules among patients with different smoking status (i.e., smokers and never smokers) (Figures S4E and S4K) and different pathological types (i.e., lung adenocarcinomas and lung squamous cell cancer) (Figures S4F and S4L). The reason should be that our DNA methylation biomarker selection and model development cohort (NCT03181490) consisted of both smoker patient subgroup (9.5% former and 18.9% current smokers) and never smoker patient subgroup (71.6%), both lung adenocarcinomas (65%) and lung squamous cell cancer (2.6%) (Table 1). The selected methylation biomarkers and the established models covered the malignant and/or benign features of these subgroups of patients. Thus, they may all benefit from this model, to which we would pay more attention in future work. Estimated by the DCA, if to consider an invasive procedure for a patient with a risk score higher than the threshold of 0.40, the combined model had a significantly larger net benefit than the methylation model alone and the two clinical models, by increasing approximately 8.2% and 17.9% accuracy in correctly identifying the malignant patients (Figures 3C and 3D). Our third highlight of this study is using the two-threshold strategy in the combined model to stratify pulmonary nodules, which is consistent with current pulmonary nodule management guidelines.27,28 This approach enables physicians to recategorize patients with nodules into three groups instead of the strategy of one threshold used in many previous reports.12,22,23 Using the high-risk threshold (≥0.94), 49.7% of individuals in the pooled validation cohorts were classified as high risk for lung cancer with high accuracy (93.9%) and high specificity (90.4%), and should be suggested for direct surgery (Figures 4B and 4C). Using the low-risk threshold (<0.22), 15.6% of individuals were classified as low risk with high accuracy (91.8%) and high sensitivity (98.1%). Those with risk scores between 0.22 and 0.94 were classified into medium risk and occupied 34.6% individuals. The low and medium-risk individuals would be suggested to do routine surveillance or other diagnosis. This strategy could reduce 90.4% unnecessary invasive surgeries. Therefore, if the model was incorporated into the current LDCT/CT screening for managing nodules in clinical practice, the test may reduce patients’ exposure to the morbidity and cost of avoidable invasive procedures.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the sample number used in the independent evaluation set was only 345 participants. More participants should be used in the future study to get more evidence of the model performance in different subgroups, particularly in early-stage (stage I and II), small-size nodules. Second, the blood samples used in this study were all baseline samples when they were recruited. All the participants of the prospective multicenter trial (NCT03651986) were followed up 2 to 3 years and not yet finished. An extensive population-based validation study and incorporation of samples from follow-up patients are needed to help to optimize the cutoff values for more accurately stratifying pulmonary nodules in future studies. Third, our study cohorts are 100% Asian Chinese origin, with 72.7% never smokers and 92.7% with adenocarcinoma of lung cancer (Table 1). Though the CpG sites located at the DMRs discovered in this study could distinguish tumor and normal tissues of patients with lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma and with variable smoking histories from the TCGA project, which are composed almost entirely of European Caucasians, it is unknown whether the methylation-marker panel that we discovered will perform equally well in other populations. Future studies recruiting diverse non-Asian populations such as European Caucasians are needed to answer this question. Fourth, as this is an observational study, to further evaluate the clinical utilities of the prediction model in real-world settings, a randomized controlled trial is required to assess its impact on guiding physician decisions to improve the preoperative diagnosis of malignant nodules and reduce unnecessary invasive procedures in patients with benign nodules.

Limitations of the study

On experimental and technical aspects, we have not compared the performance of identification of patients with malignant pulmonary nodule between our former and current 40-gene panel. Therefore, currently we do not know which is better or whether it would be better to use both combined at such identification. A head-to-head comparative study might be needed in our next study. Though a spike-in control of tumor cell line DNA into normal blood samples was tested for the detection capability of the DMR markers at different times after storage (data not shown), we have not tested sequential samples collected from the same patient over any period of time to know how reproducible the DMR detection is for the same patient, though we collected blood samples from each participant at the baseline of enrollment and during 2–3 years follow-up. All of the blood specimens were collected using the exact same protocol (i.e., the Streck tube protocol) in this study. Thus, we have no idea whether blood specimens collected by other protocols would give the same or even similar DMR scores. Therefore, more experiments to compare the effects of various sampling time and sampling methods on the feasibility of the assays would be explored in the future work in order to extend its usability. Finally, we have not studied a patient’s blood sample before and after an attempt at curative resection to know if the DMR score that is positive at the time of diagnosis becomes negative (normal) some time after resection. Such information would be important because it would indicate that the DMRs found both came from the tumor and also would represent an important way for following patients to determine the presence of minimal residual disease and/or recurrence, which would be our next attempt.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Jianxing He, drjianxing.he@gmail.com.

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

-

•

Data: Raw data of whole-genome DNA methylation sequencing of genomic DNA and targeted methylation sequencing of cfDNA derived from human samples in this study have been deposited at the China National Center for Bioinformation (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human),39,40 and the accession number (HRA007804) is listed in the key resources table. Local law prohibits depositing raw whole-genome methylation sequencing datasets derived from human samples outside of the country of origin. To request access, please contact the lead contact and the Office of Human Genetic Resource Administration of the Ministry of Science and Technology for the Regulation of the People’s Republic of China on the Administration of Human Genetic Resources. AnchorDx Medical provides access to the study protocol, the statistical analysis plan, the clinical study report, and all individual participant data except genetic data with academic researchers 6 months after the trial is completed. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed Data Use Agreement. Proposals should be directed to contact-us@anchordx.com. The requestor must describe his purpose of using the DNA methylation sequencing data. Data access will be considered for academic and/or non-profit purpose. The following restrictions apply to get access to the data: commercial and profit-making purpose.

-

•

This paper does not report original code. The software used in this study is described in the aforementioned section and the key resources table in detail.

-

•

Any additional information required the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Major Project of Guangzhou National Laboratory (no. SRPG22-017), National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 82022048 and 82373121), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangzhou (no. 202206080013), the National Key Research & Development Programme (no. 2022YFC2505100), Scheme of Guangzhou Economic and Technological Development District for Leading Talents in Innovation and Entrepreneurship (no. 2017-L152), Scheme of Guangzhou for Leading Team in Innovation (no. 201909010010), Guangdong Science and Technology (2021A1515012), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82173182), Science and Technology Program of Sichuan (2023NSFSC1939), and 1.3.5 Project for Disciplines of Excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (ZYJC 21054). We also thank all the project investigators of the clinic trials of NCT03181490 and NCT03651986.

Author contributions

J.H. and J.-B.F. conceived the study. W.L., J.T., Z.Y., J.-B.F., and J.H. designed the experiments. Z.Y. performed the experiments. J.T. and J.-B.F. performed the data modeling. N.Z., W.L., C.C., H.S., Y.G., J.Z., Q.C., D.L., L.L., H.T., and L.T. contributed to sample and data acquisition. J.T. contributed to data visualization. S.W. and J.T. wrote and J.-B.F. and W.L. reviewed the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Declaration of interests

J.T., Z.Y., S.W., L.T., and J.-B.F. are current employees of AnchorDx Medical or AnchorDx.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Biological samples | ||

| Lung tumor tissues | This study | This study |

| Adjacent non-cancerous lung tissues | This study | This study |

| Benign pulmonary nodules | This study | This study |

| Peripheral blood samples | This study | This study |

| Development cohort (including training and internal validation cohort) (NCT03181490) | ClinicalTrials.gov | https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03181490 |

| External validation cohort (NCT03651986) | ClinicalTrials.gov | https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03651986 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Cell-Free DNA BCT® blood collection tube | Streck, Inc. USA. | Cat# 218962 |

| Qiagen AIIPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit | Qiagen, USA | Cat# 80204 |

| Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | Qiagen, USA | Cat# 69504 |

| QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit | Qiagen, USA | Cat# 55114 |

| Zymo Lightning Conversion Reagent | Zymo Research, USA | Cat# D5031 |

| AnchorDx EpiVisioTM Methylation Library Prep Kit | AnchorDx, China | Cat# A0UX00019 |

| AnchorDx EpiVisioTM Indexing PCR Kit | AnchorDx, China | Cat# A2DX00025 |

| Qubit™ dsDNA HS Assay Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA | Cat# Q32854 |

| Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit | Agilent, USA | Cat# 5067-4626 |

| TruSeq Methyl Capture EPIC Library Kit | Illumina, USA | Cat# FC-151-1002 |

| An in-house 263 DMRs methylation panel | AnchorDx, China | This study |

| Deposited data | ||

| Genome-wide DNA methylation sequencing data of lung cancer and benign tissues | This study | HRA007804 in the China National Center for Bioinformation (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/) |

| Plasma cfDNA targeted methylation sequencing data of pulmonary nodule patients | This study | HRA007804 in the China National Center for Bioinformation (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/) |

| Genomic DNA targeted methylation sequencing data of pulmonary nodule tissues | This study | HRA007804 in the China National Center for Bioinformation (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/) |

| TCGA cohort data of DNA methylation sequencing and RNA sequencing of lung cancer | N/A | https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| R/Bioconductor software packages | N/A | http://www.bioconductor.org/ |

| R package DSS (v2.14.0) | SciCrunch Registry | Bioconductor (RRID:SCR_006442) |

| R package clusterProfiler (v4.9.2) | SciCrunch Registry | clusterProfiler (RRID:SCR_016884) |

| R package limma (v3.30.13) | SciCrunch Registry | Bioconductor (RRID:SCR_006442) |

| R package glmnet (v2.0-5) | SciCrunch Registry | glmnet (RRID:SCR_015505) |

| R package ggplot2 (version 2.3.3.6) | SciCrunch Registry | ggplot2 (RRID:SCR_014601) |

| R Project for Statistical Computing (version 4.3.0) (RRID:SCR_001905) | SciCrunch Registry | R Project for Statistical Computing |

| rmda R package | Vickers et al.41 | https://cran.r-project.org/package=rmda |

| Other | ||

| M220 Focused-ultrasonicator | Covaris, Inc. USA | SKU500295 |

| Qubit® 4.0 Fluorometer | Life Technologies, USA | Cat# Q33238 |

| Fragment Analyzer | Agilent Technologies, USA | Cat# G2938C |

| Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | Illumina, USA | Cat# 20012850 |

| KEGG | https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/pathway.html | |

| Reactome | https://reactome.org/PathwayBrowser/ | |

Experimental model and study participants details

The study was a multi-center, prospective, observational, case-control study intended to develop and validate a blood-based test based on cell-free DNA methylation markers for the diagnosis and management of pulmonary nodules detected by LDCT screening. The study comprised three phases: (1) marker discovery, panel design and validation, (2) model development and internal validation, (3) model external validation (Figure 1).

For the marker discovery, panel design and validation, we collected 128 fresh frozen tissue samples, including 52 lung cancer tissues, 16 adjacent normal tissues, and 60 benign tissues, from the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, and Zhujiang Hospital of Southern Medical University. The patient inclusion criteria were (1) Aged ≥18 years with no malignant tumor history within the past 5 years; (2) With history of chest computed tomography (CT) scans, abdominal and adrenal gland ultrasonography or CT, brain magnetic resonance imaging and bone scans, or PET/CT before surgery; (3) No neoadjuvant therapy was administered before surgery; (4) Received surgery resection. In addition to tissue samples, we also profiled the methylomes of white blood cells from 30 age- and sex-matched healthy controls collected from the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University using the same platform.

For the model development and evaluation, we used a prospective-specimen-collection, retrospective-blinded-evaluation (PRoBE) design. In this cross-sectional and case-control study, we included patients from two independent cohorts which were previously reported in our former studies.20,21 However, there was no overlap between the participants in this study and those in the previous studies as they were enrolled in separate dates sequentially. Moreover, the remaining biospecimens from participants in previous studies were insufficient for conducting additional targeted methylation sequencing. Our model training and internal validation cohort (NCT03181490) recruited patients between July 7, 2017 and February 12, 2019 and our external validation cohort (NCT03651986) recruited patients between October 26, 2018 and March 20, 2020. In both cohorts, the patients with pulmonary nodules detected by LDCT/CT screening were consecutively recruited from the participating hospitals. Those with 5–30 mm non-calcified and solitary pulmonary nodules, including ground-glass opacity (GGO), solid nodules (SN) and partial SN, were selected to use in this study (Tables 1 and S1). In the former cohort, we also collected resected tissue samples from a subset of participants. For 66 out of 341 training-set participants, in addition to plasma samples, tissue samples from the same patients were used for panel validation.

All enrolled participants with pulmonary nodules had undergone surgical resection with definitive pathologically diagnostic results at the participating institutions due to being assessed by a physician as high risk for lung cancer. The staging of lung cancer was judged based on the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer and the American Joint Committee on Cancer Stage Classification of non-small-cell lung cancer, eighth edition42 (Tables 1 and S1). A full list of the inclusion and exclusion criteria is provided in our previous study.21 The study was proved by the institutional review boards in corresponding hospitals. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and conducted before the study started. The two clinical trial studies had been registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03181490, NCT03651986).

Method details

Tissue and blood sample collection

This study included fresh frozen tissue samples and blood samples from patients screened positive for pulmonary nodules (PNs, <3 cm in diameter) by CT/LDCT scan and subsequently underwent surgical resections. The fresh frozen tissue samples were surgically resected, immediately cut into small pieces (<5mm in diameter) and frozen in liquid nitrogen for an hour before stored at −80° C until DNA isolation. 8–10 mL of blood was drawn 1–3 days prior to surgery and stored and shipped in Cell-Free DNA BCT blood collection tubes (Streck, Inc. USA. Cat# 218962) at room temperature according to the manufacture’s protocol. Plasma and while blood cells were separated from blood (no apparent hemolysis) within 72 h after blood draw, and then stored at −80° C until DNA isolation.43

DNA isolation

DNA isolation was performed according to our previous publication.43 Briefly, for genomic DNA (gDNA), it was isolated from frozen tissue samples using the Qiagen AIIPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, USA) or from the white blood cells using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, USA) according to the manufacture’s protocol. Purified gDNA was fragmented to 200 bp using the M220 Focused-ultrasonicator (Covaris, Inc. USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol and 100 ng of fragmented DNA was used for library construction.

For plasma samples collected using Streck BCT, cfDNA was isolated using the QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Repeated freezing and thawing of plasma were avoided to prevent cfDNA degradation and gDNA contamination from white blood cells (WBC). The concentration of cfDNA was measured using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and quality was examined using the Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent, USA) on a Qubit 4.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, USA) and a Fragment Analyzer (Agilent, USA), respectively. cfDNA with yield greater than 3 ng without overly genomic DNA contamination was proceeded to library construction.

DNA library construction and methylation sequencing

A genome-wide DNA methylation sequencing (GWMS) was performed on 128 fresh frozen tissue samples, including 52 lung cancer tissues, 16 adjacent normal tissues, 60 benign tissues, and 30 white blood cells from sex- and age-matched healthy control individuals based on a bisulfite conversion method according to the previous report.43 Briefly, DNA bisulfite conversion for an aliquot of DNA sample was performed using the Zymo Lightning Conversion Reagent (Zymo Research, Cat# D5031) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The bisulfite-converted DNA was then used to constructed pre-library using AnchorDx EpiVisioTM Methylation Library Prep Kit (AnchorDx, Cat# A0UX00019). The concentration of the library was determined using Qubit dsDNA HS Assay kit. Pre-libraries containing more than 400 ng DNA were considered qualified for target enrichment.

For the pre-library from gDNA of 128 fresh frozen tissue samples and 30 white blood cells, target enrichment for final library construction was performed by using the TruSeq Methyl Capture EPIC Library Kit (Illumina, USA).43 For the pre-library from cfDNA and gDNA of 64 validation tissue samples from the development cohort (NCT03181490), target enrichment for final library construction was performed by using our customized panel of 263 DMRs for lung cancer-specific methylation sequencing. The sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform.

Methylation marker discovery for a targeted panel design

Our goal was to find a parsimonious panel of cfDNA methylation markers that would enable accurately discriminating between malignant and benign pulmonary nodules. To that end, we applied a series of filtering steps to narrow down the methylation marker candidates. First, we looked for differentially methylated regions (DMRs) by comparing genome-wide methylome profiles among 52 malignant, 16 adjacent normal, and 60 benign tissues (methylation difference ≥0.05, p < 0.01). Second, to ensure the reliability of the selected DMRs, we required that the DMRs should contain at least 5 differentially methylated CpG sites. Third, to achieve high signal-to-noise ratio in cfDNA samples, we chose DMRs whose mean methylation levels were less than 5% (low noise) in benign tissues and more than 10% (high signal) in malignant tissues. Fourth, we needed the area under the curve (AUC) of receiver operating characteristic of the chosen DMRs in discriminating between malignant and benign tissues to be larger than 90% in order to guarantee the strong discriminative capability. Fifth, to minimize the background noise from white blood cells which were reported to be the primary source of the cfDNA, we removed DMRs with high methylation levels in white blood cells (β-value ≤0.2 in 30 healthy controls). Finally, we eliminated DMRs that were located on X or Y chromosomes. Following the aforementioned multi-step filtering process, a customized panel of 263 DMRs was designed and validated in 44 malignant and 20 benign tissue samples (left part of Figures 1, S1 and Table S2). All technicians who performed laboratory assays were blinded to all clinical information about participants.

Due to the locally coordinated activities of the DNA methyltransferases (DNMT1, DNMT3A, DNMT3B) and the TET methylcytosine dioxygenase proteins (TET1, TET2 and TET3), adjacent CpG sites on the same DNA molecules can share similar methylation status, which is also known as co-methylation. As co-methylation based metric was reported to have higher signal-to-noise ratio than average methylation level which is defined by the ratio of methylated CpG sites to the total CpG sites across all sequenced DNA fragments in a specific genomic region, we defined a co-methylation metric called co-methylation score as follows as previously reported43:

For a given DMR, co-methylated DNA fragments were defined as those fragments having at least 3 methylated CpGs within a sliding window of 5 CpGs. The number of DNA fragments in this DMR was used to normalize the depth difference, bounding the metric between 0 and 1. We used co-methylation score of each DMR as our methylation feature in marker selection and model building and evaluation.

Differentially methylated regions identification

Differentially methylated CpG sites were identified using R package DSS (v2.14.0) by comparing malignant tissues with benign and normal tissues (p value <0.01, beta difference >0.05). The differentially methylated CpG sites were then assembled into DMRs, which should meet the following criteria: (1) a minimum length of 10 base pairs; (2) a minimum of 3 CpG sites; and (3) a percentage of differentially methylated CpG sites in the region greater than 50%.

Gene functional exploration

Functional relevance of the genes overlapping with differentially methylated regions between malignant and benign pulmonary nodule tissue samples were investigated for enrichment of canonical pathways maintained by the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Reactome pathway databases using the R package clusterProfiler (v4.9.2) (Figures S2E and S2F). In addition, we downloaded the RNA-seq data for lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD tumors, n = 514; normal tissues, n = 59) from the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov) and analyzed the expression levels of genes that overlapped the final cell-free DNA methylation model markers (Figure S2G). Differentially expressed genes between TCGA lung adenocarcinoma tumors and normal tissues were identified by the R package limma (v3.30.13) if the FDR was less than 0.05.

cfDNA-methylation model development and validation

A prospective multicenter cohort (NCT03181490; n = 620) was divided into a training set (n = 341) and an internal validation set (n = 279). The training set consisted of all participants enrolled at five randomly selected hospitals. The internal validation set comprised all participants from the remaining five hospitals. We used a multistep approach to define a minimal set of methylation markers that could be used to build a stable and generalizable model. To select the features forming the minimum set, we applied a variable selection method suitable for high-dimensionality on the training set: Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO). The use of the LASSO ensured the sparsity of the selected markers, avoiding the simultaneous selection of correlated markers. As results can depend strongly on the arbitrary choice of a random sample split for sparse high-dimensional data, we subsampled 80 percent of the training set without replacement 1000 times and selected the markers with non-zero coefficients frequency more than 800. The parameters were determined according to the expected generalization error estimated from 10-fold cross-validation, and we selected the value of lambda such that the error was within one standard error of the minimum, known as “1-se” lambda. We used the R package glmnet (v2.0-5) as the LASSO implementation. After this multistep process, we eventually obtained a minimum set of 40 methylation markers. We then fit a logistic regression model using the selected 40 methylation markers in the training set. We chose logistic regression algorithm for model building because of its good performance, simplicity and interpretability. The diagnostic performance of the methylation model was then assessed in the internal validation set and a prospective external validation cohort (NCT03651986; n = 343) (See middle and right parts of Figures 1, 3A and 3B).

Correlation analysis of methylation biomarkers from different samples

A principal component analysis (PCA) was carried out using the cell-free DNA targeted methylation sequencing dataset comprising participants from 10 hospitals in the model developing cohort (NCT03181490) to confirm that our methylation biomarkers are derived from lung cancer-associated features rather than hospital-specific features. PCA was performed using “prcomp” function from R stat package. The PCA plots were generated using R package ggplot2 (version 2.3.3.6) (Figures S3A and S3B).

For 66 out of 341 patients in the training set, their methylation profiles were obtained on both the plasma and tissue samples. The association of the selected DNA methylation biomarkers between plasma cfDNA methylation and tissue genomic DNA methylation were calculated using Pearson’s correlation analysis (Figure S3C). p < 0.05 means significancy.

Developing a combined model of clinical, imaging, and cfDNA methylation biomarkers

To assess whether a combined model of clinical, imaging and cell-free DNA methylation features could further improve the diagnostic performance, we fit a logistic regression based multimodal predictive model by integrating the clinical, CT imaging features and methylation model risk score in the training cohort. For clinical features, age, gender, smoking history, and family history of lung cancer were assessed on their statistical significance in differentiating benign and malignant groups in the training cohort. Of these, only age was found to be significant different (p = 0.01) and thus was included in the combined model. In terms of imaging features, we only consider those easily accessible features or features that are quantitative on the basis of features identified in the clinical practice and guidelines for pulmonary nodule management. We selected large diameter, short diameter, nodule size (defined by large diameter × short diameter), nodule type (GGO, partial SN, SN), mean attenuation value (MAV) in our combined model. The combined model was built in the training cohort (n = 341) and assessed in two independent multicenter prospective cohorts (n1 = 279, n2 = 343) (Figures 3, 4, and S4).

Quantification and statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using R Project for Statistical Computing (version 4.3.0). Descriptive statistics were reported as mean ± s.d. or n (%). Comparisons between groups were performed using the chi-square test (for categorical variables) and independent samples t-test or the Mann-Whitney U-test (for continuous variables). Where applicable, the alpha threshold for significance in two-tailed hypothesis testing was set at 0.05. The Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD) guidelines were followed in reporting all diagnostic accuracy values. We reported diagnostic performance using the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value and negative predictive value, along with 95% CI where applicable. The sample size calculation was reported previously.21,44 Briefly, to achieve a margin of error of 5% for a point estimate of 90% sensitivity, at a 0.05 p value α level and 70% prevalence, at least 197 patients (138 patients with a malignant nodule and 59 with a benign nodule) were needed. The clinical utilities of the model were evaluated by decision curve analysis (DCA) using the rmda R package, which quantified the net benefits for participants at different threshold probabilities.41

Published: September 27, 2024

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101750.

Contributor Information

Wenhua Liang, Email: liangwh1987@163.com.

Jian-Bing Fan, Email: jianbingfan1115@smu.edu.cn.

Jianxing He, Email: drjianxing.he@gmail.com.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Giaquinto A.N., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2024;74:12–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y., Luo G., Etxeberria J., Hao Y. Global Patterns and Trends in Lung Cancer Incidence: A Population-Based Study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021;16:933–944. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.01.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blandin Knight S., Crosbie P.A., Balata H., Chudziak J., Hussell T., Dive C. Progress and prospects of early detection in lung cancer. Open Biol. 2017;7 doi: 10.1098/rsob.170070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yotsukura M., Asamura H., Motoi N., Kashima J., Yoshida Y., Nakagawa K., Shiraishi K., Kohno T., Yatabe Y., Watanabe S.I. Long-Term Prognosis of Patients With Resected Adenocarcinoma In Situ and Minimally Invasive Adenocarcinoma of the Lung. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021;16:1312–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Aberle D.R., Adams A.M., Berg C.D., Black W.C., Clapp J.D., Fagerstrom R.M., Gareen I.F., Gatsonis C., Marcus P.M., Sicks J.D. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Koning H.J., van der Aalst C.M., de Jong P.A., Scholten E.T., Nackaerts K., Heuvelmans M.A., Lammers J.W.J., Weenink C., Yousaf-Khan U., Horeweg N., et al. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Volume CT Screening in a Randomized Trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:503–513. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aberle D.R., DeMello S., Berg C.D., Black W.C., Brewer B., Church T.R., Clingan K.L., Duan F., Fagerstrom R.M., Gareen I.F., et al. Results of the two incidence screenings in the National Lung Screening Trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:920–931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazzone P.J., Lam L. Evaluating the Patient With a Pulmonary Nodule: A Review. JAMA. 2022;327:264–273. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.24287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Church T.R., Black W.C., Aberle D.R., Berg C.D., Clingan K.L., Duan F., Fagerstrom R.M., Gareen I.F., Gierada D.S., et al. Results of initial low-dose computed tomographic screening for lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:1980–1991. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang W., Qian F., Teng J., Wang H., Manegold C., Pilz L.R., Voigt W., Zhang Y., Ye J., Chen Q., et al. Community-based lung cancer screening with low-dose CT in China: Results of the baseline screening. Lung Cancer. 2018;117:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li L., Zhao Y., Li H. Assessment of anxiety and depression in patients with incidental pulmonary nodules and analysis of its related impact factors. Thorac. Cancer. 2020;11:1433–1442. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nair V.S., Sundaram V., Desai M., Gould M.K. Accuracy of Models to Identify Lung Nodule Cancer Risk in the National Lung Screening Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018;197:1220–1223. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201708-1632LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi H.K., Ghobrial M., Mazzone P.J. Models to Estimate the Probability of Malignancy in Patients with Pulmonary Nodules. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2018;15:1117–1126. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201803-173CME. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silvestri G.A., Vachani A., Whitney D., Elashoff M., Porta Smith K., Ferguson J.S., Parsons E., Mitra N., Brody J., Lenburg M.E., et al. A Bronchial Genomic Classifier for the Diagnostic Evaluation of Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:243–251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Widschwendter M., Jones A., Evans I., Reisel D., Dillner J., Sundström K., Steyerberg E.W., Vergouwe Y., Wegwarth O., Rebitschek F.G., et al. Epigenome-based cancer risk prediction: rationale, opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018;15:292–309. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerr K.M., Galler J.S., Hagen J.A., Laird P.W., Laird-Offringa I.A. The role of DNA methylation in the development and progression of lung adenocarcinoma. Dis. Markers. 2007;23:5–30. doi: 10.1155/2007/985474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skvortsova K., Stirzaker C., Taberlay P. The DNA methylation landscape in cancer. Essays Biochem. 2019;63:797–811. doi: 10.1042/EBC20190037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Batool S.M., Yekula A., Khanna P., Hsia T., Gamblin A.S., Ekanayake E., Escobedo A.K., You D.G., Castro C.M., Im H., et al. The Liquid Biopsy Consortium: Challenges and opportunities for early cancer detection and monitoring. Cell Rep. Med. 2023;4 doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.101198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen S.Y., Singhania R., Fehringer G., Chakravarthy A., Roehrl M.H.A., Chadwick D., Zuzarte P.C., Borgida A., Wang T.T., Li T., et al. Sensitive tumour detection and classification using plasma cell-free DNA methylomes. Nature. 2018;563:579–583. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0703-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang W., Chen Z., Li C., Liu J., Tao J., Liu X., Zhao D., Yin W., Chen H., Cheng C., et al. Accurate diagnosis of pulmonary nodules using a noninvasive DNA methylation test. J. Clin. Invest. 2021;131 doi: 10.1172/JCI145973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He J., Wang B., Tao J., Liu Q., Peng M., Xiong S., Li J., Cheng B., Li C., Jiang S., et al. Accurate classification of pulmonary nodules by a combined model of clinical, imaging, and cell-free DNA methylation biomarkers: a model development and external validation study. Lancet. Digit. Health. 2023;5:e647–e656. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(23)00125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swensen S.J., Silverstein M.D., Ilstrup D.M., Schleck C.D., Edell E.S. The probability of malignancy in solitary pulmonary nodules. Application to small radiologically indeterminate nodules. Arch. Intern. Med. 1997;157:849–855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McWilliams A., Tammemagi M.C., Mayo J.R., Roberts H., Liu G., Soghrati K., Yasufuku K., Martel S., Laberge F., Gingras M., et al. Probability of cancer in pulmonary nodules detected on first screening CT. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:910–919. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vachani A., Zheng C., Amy Liu I.L., Huang B.Z., Osuji T.A., Gould M.K. The Probability of Lung Cancer in Patients With Incidentally Detected Pulmonary Nodules: Clinical Characteristics and Accuracy of Prediction Models. Chest. 2022;161:562–571. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vickers A.J., van Calster B., Steyerberg E.W. A simple, step-by-step guide to interpreting decision curve analysis. Diagn. Progn. Res. 2019;3:18. doi: 10.1186/s41512-019-0064-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Calster B., Wynants L., Verbeek J.F.M., Verbakel J.Y., Christodoulou E., Vickers A.J., Roobol M.J., Steyerberg E.W. Reporting and Interpreting Decision Curve Analysis: A Guide for Investigators. Eur. Urol. 2018;74:796–804. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bai C., Choi C.M., Chu C.M., Anantham D., Chung-Man Ho J., Khan A.Z., Lee J.M., Li S.Y., Saenghirunvattana S., Yim A. Evaluation of Pulmonary Nodules: Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines for Asia. Chest. 2016;150:877–893. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.02.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gould M.K., Donington J., Lynch W.R., Mazzone P.J., Midthun D.E., Naidich D.P., Wiener R.S. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143:e93S–e120S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li C., Wang H., Jiang Y., Fu W., Liu X., Zhong R., Cheng B., Zhu F., Xiang Y., He J., Liang W. Advances in lung cancer screening and early detection. Cancer Biol. Med. 2022;19:591–608. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2021.0690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madariaga M.L., Lennes I.T., Best T., Shepard J.A.O., Fintelmann F.J., Mathisen D.J., Gaissert H.A., MGH Pulmonary Nodule Clinic Collaborative Multidisciplinary selection of pulmonary nodules for surgical resection: Diagnostic results and long-term outcomes. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020;159:1558–1566.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang W., Duan X., Zhang Z., Yang Z., Zhao C., Liang C., Liu Z., Cheng S., Zhang K. Combination of CT and telomerase+ circulating tumor cells improves diagnosis of small pulmonary nodules. JCI Insight. 2021;6 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.148182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li X.J., Hayward C., Fong P.Y., Dominguez M., Hunsucker S.W., Lee L.W., McLean M., Law S., Butler H., Schirm M., et al. A blood-based proteomic classifier for the molecular characterization of pulmonary nodules. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013;5 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu H., Raut J.R., Schöttker B., Holleczek B., Zhang Y., Brenner H. Individual and joint contributions of genetic and methylation risk scores for enhancing lung cancer risk stratification: data from a population-based cohort in Germany. Clin. Epigenet. 2020;12:89. doi: 10.1186/s13148-020-00872-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]