Nerve injuries about the shoulder can cause significant pain and dysfunction. Patients with these injuries suffer not only from reduced strength and active range of motion but also reduced ability to work, lower quality of life, and higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression.8,16,19

Given its intimate anatomic relationship to the humeral neck, the axillary nerve is the most common peripheral nerve injury affecting the shoulder and is the most common nerve to be injured after a glenohumeral joint dislocation.15,24 The axillary nerve can also be injured from other trauma including proximal humerus fractures or iatrogenic injury after shoulder surgery.24 In isolation, axillary nerve injuries can produce weakness in forward flexion and abduction of the shoulder, but typically a functioning rotator cuff can compensate to permit near full range of motion.1,20 Axillary nerve dysfunction can also result from C5 nerve root pathology and brachial plexus injury. When combined with rotator cuff dysfunction, however, axillary nerve palsy results in a flail shoulder.

The most common indication for reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) is rotator cuff arthropathy.23 More recently, RSAs have been utilized in patients suffering from irreparable rotator cuff tears without glenohumeral arthritis, acute or malunited proximal humerus fractures, glenohumeral arthritis with severe glenoid bone loss, shoulder dysplasia, immunological glenohumeral arthritis, and chronic fixed shoulder dislocations.17 RSAs biomechanically require a functioning deltoid muscle, although there remains a paucity of literature regarding how much deltoid function and strength are required to power a RSA. Therefore, axillary nerve and deltoid muscle impairment have historically been a contraindication to RSA.4,11 This combination of rotator cuff dysfunction coupled with an axillary nerve palsy presents a significant clinical dilemma.

In 2003, Leechavengvongs et al first reported their series of patients who underwent long head of the triceps nerve branch transfer to the axillary nerve to restore deltoid function after brachial plexus injury.21,31 Numerous studies have demonstrated improved clinical outcomes after this procedure including improved deltoid function, shoulder abduction and strength testing.5, 6, 7,10,20,21 It remains unclear, however, if this nerve transfer confers sufficient clinical strength to power an RSA in patients with rotator cuff deficiency. If so, the optimal timing of RSA after axillary nerve function restoration needs to be determined as well.

To our knowledge, there are no prior reports of successful RSA after end-to-end triceps to axillary nerve transfer. Previous case reports do note success of RSA following reverse end-to-side (RETS) triceps to axillary nerve transfer.25,27 However, in RETS, it is difficult to know if the deltoid recovery is due to the nerve transfer, clinical recovery of the axillary nerve, or a combination of the 2. With an end-to-end nerve transfer, however, the deltoid recovery is solely a result of reinnervation from the triceps nerve transfer. This case series describes RSA after end-to-end triceps to axillary nerve transfer and examines the sequence, timing, and outcomes of this novel technique for a challenging clinical conundrum.

Methods

Approval was granted by our Institutional Review Board and consent was obtained from each patient. Before nerve transfer, all patients demonstrated 0/5 deltoid strength and 0° of active shoulder forward flexion and abduction. Muscle strength was characterized using the Medical Research Council grading system. For each patient, electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction study (NCS) testing performed at 4-5 months from initial injury confirmed complete axillary nerve palsy without evidence of nerve recovery, as evidenced by 0 or 1+ polyphasic potential, and lack of deltoid muscle function. Time from initial injury to nerve transfer procedure ranged from 5-6 months. The end-to-end triceps to axillary nerve transfer was performed via a posterior approach as described by Leechavengvongs et al21,31 Intraoperatively, the branch of the axillary nerve to teres minor and the anterior and posterior divisions of the axillary nerve were identified, neurolysed, and stimulated on 0.5 milliamps and 2.0 milliamps settings without deltoid contracture. Stimulation with 20 milliamps demonstrated minimal deltoid contraction. Before transfer, vigorous contraction of the medial and lateral heads of the triceps was confirmed with stimulation of the respective radial nerve branches with 0.5 milliamps. For all 3 patients, end-to-end nerve transfer was performed into the anterior division of the axillary nerve. Other than the anterior division of the axillary nerve which is transected for nerve transfer, the remainder of the axillary nerve was left in continuity. In 2 patients, nerve to the lateral head of triceps was utilized as the nerve donor, while in 1 patient nerve to medial head of triceps served as the donor (Table I). Nerve transfer was performed by 1 of the 3 most senior authors, all of whom are fellowship-trained hand and upper extremity orthopedic surgeons. Postoperatively, the patient was placed into a sling and instructed to limit shoulder range of motion for 2 weeks then allowed to perform shoulder range of motion as tolerated.

Table I.

Nerve donor and recipient of 3 patients in case series.

| Nerve donor | Nerve recipient | Repair fashion | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | Lateral head triceps | Anterior axillary | End-to-end |

| Patient 2 | Lateral head triceps | Anterior axillary | End-to-end |

| Patient 3 | Medial head triceps | Anterior axillary | End-to-end |

At approximately 6 months postoperatively from triceps to axillary nerve transfer, EMG and NCS testing was performed. For all patients in this series, EMG and NCS confirmed reinnervation of the deltoid muscle with polyphasics and recruitment in the anterior, middle, and posterior heads of the deltoid muscle (Table II). Before RSA, all patients demonstrated moderate to strong palpable deltoid contraction but continued difficulty with active forward elevation and abduction of the arm (Table III).

Table II.

Electromyography testing for each patient, performed after triceps to axillary nerve transfer but prior to reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

| Fibrillation potential | Positive sharp waves | Motor unit amplitude | Polyphasic potential | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | ||||

| Anterior deltoid | 2+ | 2+ | Increased | 1+ |

| Middle deltoid | 2+ | 2+ | Increased | 1+ |

| Posterior deltoid | 2+ | 2+ | Increased | 1+ |

| Patient 2 | ||||

| Anterior deltoid | 2+ | 2+ | Normal | 1+ |

| Middle deltoid | 2+ | 2+ | Increased | 1+ |

| Posterior deltoid | 2+ | 2+ | Normal | 1+ |

| Patient 3 | ||||

| Deltoid | 2+ | 2+ | Increased | 1+ |

Passive motion is documented when present.

Table III.

Active shoulder range of motion (degrees) and deltoid strength testing for each patient at time of presentation, after triceps to axillary nerve transfer, and after reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

| Presentation | After nerve transfer | After RSA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | |||

| Deltoid strength | 0/5 | moderate | 4/5 |

| Forward flexion | 0 | 40 | 120 |

| Abduction | 0 | 45 | 100 |

| External rotation | 0 | 10 | 40 |

| Internal rotation | - | - | Lumbar level 1 |

| Patient 2 | |||

| Deltoid strength | 0/5 | strong | 4/5 |

| Forward flexion | 0 | 40 | 95 (105 passive) |

| Abduction | 0 | 40 | 70 (90 passive) |

| External rotation | - | 0 | 70 |

| Internal rotation | - | - | Posterolateral buttock |

| Patient 3 | |||

| Deltoid strength | 0/5 | moderate | 4/5 |

| Forward flexion | 0 | 60 | 110 (140 passive) |

| Abduction | 0 | 0 | 75 (80 passive) |

| External rotation | 0 | Neutral | Neutral (10 passive) |

| Internal rotation | - | 0 | Iliac crest |

Passive motion is documented when present. RSA, reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

At a minimum of 1 year postoperative from triceps to axillary nerve transfer, RSA was performed using a standard deltopectoral approach. Postoperatively, patients were placed into a sling and instructed to limit shoulder range of motion for 2 weeks before weaning out of the sling. The patient then followed our standard RSA rehabilitation protocol, working with physical therapy from 2 to 16 weeks postoperatively.

Cases

Patient 1

A 58-year-old male presented with shoulder weakness after falling from a porch. He underwent an arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (RCR) performed by an outside surgeon. He had persistent shoulder dysfunction and lateral shoulder numbness postoperatively prompting an EMG/NCS at 5 months after injury which revealed an axillary nerve injury. Six months after the initial injury, on physical exam he had deltoid atrophy, 0/5 deltoid and teres minor strength, 0/5 supraspinatus and infraspinatus strength, and 4/5 subscapularis strength and numbness in the axillary nerve distribution. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) arthrogram revealed a massive rotator cuff tear retracted medial to the glenoid rim. Six months after initial injury, the patient underwent an open massive RCR of the infraspinatus with superior capsular reconstruction (SCR) for the irreparable supraspinatus. He also underwent end-to-end transfer of the lateral head triceps branch of radial nerve to anterior branch of the axillary nerve. The patient participated in physical therapy, and at 2 years status after open RCR and nerve transfer was noted to have active firing of anterior, middle, and posterior deltoid with moderate deltoid strength, active shoulder forward flexion to 40°, abduction to 45°, extension to 50°, and external rotation to 10° with a 20° external rotation lag. EMG confirmed significant but incomplete recovery of deltoid muscle with 2+ fibrillation potentials, 2+ positive sharp waves and 1+ polyphasic potentials. Repeat MRI demonstrated healing of the repaired infraspinatus, and no definite visualization of the SCR. At 2 years following revision RCR with SCR and triceps to axillary nerve transfer, deltoid contraction and muscle bulk had improved but active shoulder motion had not. Therefore, RSA was performed to give the patient improved forward elevation and abduction. At 3.5 years status after RSA, the patient had no shoulder pain and reported continued improvement in shoulder strength. On physical exam, he had active shoulder forward flexion to 120°, abduction to 100°, external rotation to 40°, and internal rotation to the upper lumbar spine (Fig. 1). He had 4/5 strength in testing of the anterior, middle, and posterior heads of the deltoid muscles. He had returned to his prior job as a truck driver.

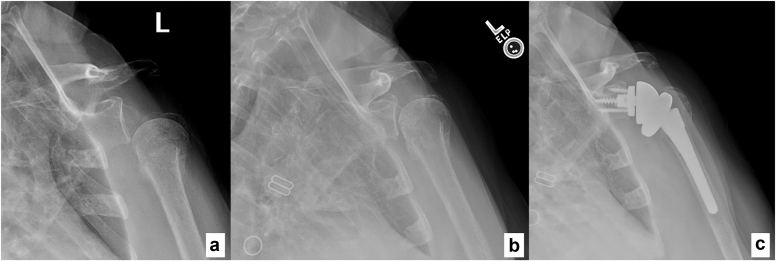

Figure 1.

Patient 1 shoulder range of motion, 5 years status after triceps to axillary nerve transfer and 3 years after reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

Patient 2

An otherwise healthy 65-year-old male presented with right shoulder weakness due to C5 nerve root palsy after cervical spine surgery performed by an outside provider. On physical exam, the patient was found to have 0/5 deltoid strength, 0/5 elbow flexion strength, a significant external rotation lag sign and positive drop arm sign. He did have 5/5 strength in elbow extension, wrist extension, wrist flexion, and grip strength. At 5 months postoperatively after spine surgery, EMG/NCS demonstrated no polyphasics or signs of any electrodiagnostic evidence of recovery to the deltoid, biceps, or brachialis. Six months after the cervical spine procedure, the patient underwent lateral triceps nerve end-to-end transfer to anterior axillary nerve branch. In the same procedure he also underwent ulnar nerve fascicle of the flexor carpi ulnaris transfer to brachialis nerve branch of the musculocutaneous nerve as well as median nerve flexor carpi radialis branch transfer to the biceps branch of the musculocutaneous nerve. Six months after nerve transfer, the patient continued to have rotator cuff weakness, and MRI demonstrated complete, retracted supraspinatus and subscapularis tears. It became evident that he had been compensating for a massive, chronic anterosuperior rotator cuff tear before his C5 palsy, but with complete deltoid paralysis and impaired suprascapular nerve function he could no longer compensate. He underwent open subscapularis repair and arthroscopic supraspinatus repair to maximize his potential for recovery. Eighteen months status after nerve transfer and 1 year status after RCR, patient had continued rotator cuff weakness and MRI revealed retearing of his rotator cuff. On physical exam the patient had strong palpable deltoid contraction and EMG showed reinnervation of deltoid muscle with 2+ fibrillation potentials, 2+ positive sharp waves and 1+ polyphasic potentials. Almost 2 years after the nerve transfer surgery, the patient underwent RSA. Five years after RSA, the patient demonstrated improved shoulder range of motion and strength. He was able to actively forward flex his shoulder to 95° with passive forward flexion to 105°, abduct to 70° actively and 90° passively, externally rotate with arm adducted to 70°, internally rotate to posterolateral buttock and had a negative external rotation lag sign (Fig. 2). He had 4/5 strength in anterior, middle, and posterior heads of the deltoid and excellent deltoid muscle bulk. He was overall pleased with his progress and with his ability to participate in hobbies such as fishing and lawncare. His patient reported outcomes included an American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons score of 20 (compared to 48 on contralateral side), Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) score of 48 and Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation score of 50.

Figure 2.

Patient 2 shoulder range of motion, 7 years after triceps to axillary nerve transfer and 5 years after reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

Patient 3

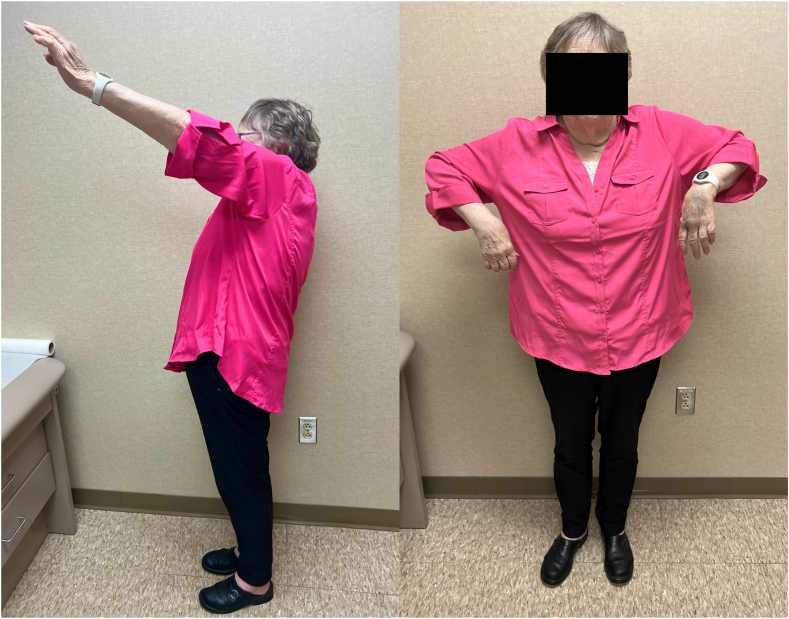

A 71-year-old female with past medical history of diabetes mellitus type II presented with a global brachial plexopathy after falling down a flight of stairs and sustaining a proximal humerus fracture treated nonoperatively by an outside provider. Her global plexopathy gradually improved with recovery of the lower plexus, but she was left with no active shoulder forward flexion, abduction, external rotation, or elbow flexion. She had no palpable deltoid, brachialis, supraspinatus, or infraspinatus function. Radiographs of the shoulder showed a proximal humerus fracture with complete inferior subluxation at the glenohumeral joint (Fig. 3). Four months after initial injury, EMG/NCS demonstrated 1+ polyphasics in all upper-extremity muscles including the deltoid muscle, as well as 2+ fibrillations in the biceps and triceps, and 3+ fibrillations in upper plexus muscles including the deltoid and infraspinatus. However, on physical exam, the patient demonstrated 4/5 strength with elbow flexion, but 0/5 strength in deltoid, supraspinatus, and infraspinatus muscles. Given she had no evidence of spontaneous reinnervation of the upper plexus on EMG/NCS and physical exam, she underwent medial head of the triceps end-to-end nerve transfer to the anterior division of the axillary nerve 5 months after initial injury. At 8 months postoperative, she had recovering axillary nerve function with moderate palpable deltoid contraction on physical exam and 2+ fibrillation potentials, 2+ positive sharp waves, and 1+ polyphasic potentials of deltoid muscle on EMG. Radiographs of the shoulder at this time revealed recentering of the humeral head in relation to the glenohumeral joint (Fig. 3). However, she did have post-traumatic arthritis of the proximal humerus in the setting of her prior proximal humerus fracture and prolonged inferior subluxation of the glenohumeral joint. Given the partial recovery of the deltoid with persistent rotator cuff dysfunction, she was offered and underwent RSA at 1 year after nerve transfer procedure. At 2.5 years status after RSA, she had regained active shoulder forward flexion to 110° (140° passive), active abduction to 75° (80° passive), external rotation to neutral (10° passive), and internal rotation to iliac crest (Fig. 4). Shoulder strength was 4/5 with deltoid testing as well as with testing of shoulder forward flexion, abduction, and internal and external rotation. Radiographs demonstrated stable arthroplasty components. She reported her shoulder strength and range of motion were much improved compared to preoperatively, although she does have some difficulty with overhead activities. Her patient reported outcomes included an American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons score of 43 (compared to 42 on contralateral side, on which she had history of proximal humerus fracture), DASH score of 35 and Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation score of 50.

Figure 3.

Shoulder radiographs of patient 3 taken (a) before triceps to axillary nerve transfer, (b) 8 months status after nerve transfer and (c) after reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

Figure 4.

Patient 3 shoulder range of motion (Left operative side), 3 years after triceps to axillary nerve transfer and 2 years status after reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

Results

Two of our 3 patients presented with axillary nerve injury after a trauma while 1 patient presented with C5 palsy after cervical spine surgery. Rotator cuff dysfunction was due to chronic rotator cuff tear in 2 patients and suprascapular nerve palsy in one patient.

After triceps to axillary nerve transfer, all patients experienced return of deltoid contraction at 6-12 months postoperative. Before RSA, patients demonstrated moderate to strong palpable deltoid contraction and evidence of reinnervation on EMG deltoid testing (Tables II and III). Of note, it is difficult to accurately grade deltoid strength in the setting of pseudoparalysis from rotator cuff dysfunction. When clinically able, i.e. in the 2 patients without suprascapular nerve palsy, deltoid strength testing was also performed in the “akimbo” position with hands on iliac crest, shoulder abduction and internal rotation.12 All 3 patients had improvement in active shoulder forward flexion and abduction after RSA (Table III). Subjectively, all patients reported improved shoulder strength and range of motion and are pleased with their progress. DASH scores obtained for 2 of the 3 patients were 35 and 48. No patients experienced postoperative shoulder instability or dislocation. There were no complications including infection or hardware failure.

Discussion

We report 3 successful cases of RSA after end-to-end triceps to axillary nerve transfer in the setting of axillary nerve palsy combined with rotator cuff dysfunction. Our study includes nerve transfers performed from both the medial and lateral branches of the triceps. Two prior case reports describe patients who underwent RSA after RETS radial to axillary nerve transfer.25,27 With RETS transfer, sometimes called “supercharged” nerve transfer, it is not possible to know whether the reinnervation of the recipient muscle (the deltoid in this case) is a result of the nerve transfer, from spontaneous recovery, or from a combination of the two. With end-to-end transfer, all reinnervation comes from the donor triceps nerve.

All patients in this series achieved improved shoulder range of motion from RSA following triceps to axillary nerve transfer. The patients generally demonstrated stepwise improvement in range of motion after nerve transfer then again after RSA.

Complete deltoid muscle impairment has traditionally been a contraindication to RSA.4,11 However, more recent studies question if partial deltoid impairment is a contraindication to RSA.18,28 Ladermann et al described successful RSA in patients with moderate deltoid impairment,18 while Tay et al described good outcomes after RSA in a patient with rupture of middle third of the deltoid.28 In the setting of deltoid impairment or axillary nerve injury, nerve transfer from triceps to axillary nerve can improve deltoid function and potentially allow for future RSA.

Regarding donor nerve branch selection, we utilized either the branch of radial nerve to lateral head of triceps or branch of radial nerve to medial head of triceps. The initial description of triceps to axillary nerve transfer employed the branch to long head of the triceps, noting that the branch to long head was a favorable donor due to its diameter, number of axons, and anatomic proximity to axillary nerve.21,31 Alternatively, some prefer the branch to the medial head of triceps given its ease of identification and increased length.6,9 Bertelli et al reported improved strength, endurance, and volume of deltoid after transfer of nerve to triceps medial head to deltoid for axillary nerve palsy.6 When comparing branch to triceps long head vs. branch to triceps lateral head for axillary nerve reanimation, no significant differences have been observed.5 Desai et al found no differences in outcomes when comparing transfer of long, lateral, and medial branches to triceps to axillary nerve.10 Ultimately, patient anatomy and donor nerve response to intraoperative stimulation should dictate which branch of radial nerve is selected for transfer.

The timing of nerve transfer is vital to success. Transfer of the nerve in a timely manner allows for regeneration before motor endplate involution. Though this process occurs in a linear fashion, motor endplates are generally considered to be involuted to the point of limiting clinically meaningful recovery at time points well beyond 6-7 months postinjury depending on the length of nerve recovery.2,3,14,22 Depending on etiology of the nerve injury, this timing must be balanced with clinical observation for potential spontaneous recovery of nerve function. All patients in our case series underwent nerve transfer between 5-6 months from initial injury. The optimal window for nerve-related intervention should be a careful consideration of any shoulder surgeon treating these complex patients.

Transfer of a radial nerve branch to triceps carries the potential risk of triceps weakening. After transfer of triceps to axillary nerve, 1 study noted severe loss of triceps strength but without subjective impact on activities of daily life,26 while another study found no donor site complications and preserved triceps strength.10 None of our 3 patients suffered from objective triceps weakness and none subjectively noted triceps weakness that affected their daily life.

This study also provides insight into the question of optimal timing of RSA after deltoid reanimation. In each case, patients were at least 12 months status post–nerve transfer before performing RSA. Triceps to axillary nerve transfer is successful in achieving grade 3 or higher deltoid strength in approximately 70%-100% of cases.10,20,21,29 In this case series, each patient reached moderate to strong palpable deltoid contraction by 1-2 years after nerve transfer. We advocate waiting to determine the clinical effect of the reinnervated deltoid before considering RSA—which was after 1-2 years in our case series. If RSA is performed with a denervated or weak deltoid, clinical function may not improve and the patient is at high risk for shoulder instability and dislocation.13,18,30 While the nerve transfer procedure is time sensitive from time of injury, the arthroplasty procedure is not. Contraindications to both nerve transfer and arthroplasty include open wounds or infection and active radiation therapy.

Conclusion

This case series of 3 patients who underwent RSA after end-to-end triceps to axillary nerve transfer demonstrates favorable outcomes. Our 3 patients represent a broad spectrum of indications for both the initial triceps-to-axillary nerve transfer as well as the subsequent RSA. All 3 patients achieved improved shoulder range of motion and function. Patients with concomitant axillary nerve dysfunction and rotator cuff dysfunction represent a formidable clincal challenge. Triceps to axillary nerve transfer with delayed RSA is a viable option for treating these complex patients.

Disclaimers:

Funding: No grants or funding were used to complete this work.

Conflicts of interest: R. Glenn Gaston reported receiving royalties from Zimmer Biomet and Stryker and works as a paid consultant for Endo, Restor3d, Hanger clinic, Stryker, and BME. Bryan J. Loeffler reported working as a paid consultant and speaker for Checkpoint Surgical and Hanger clinic. The other authors, their immediate families, and any research foundations with which they are affiliated have not received any financial payments or other benefits from any commercial entity related to the subject of this article.

Patient consent: Consent was obtained from each patient for this study.

Footnotes

Atrium/Carolinas Healthcare System approved this study, IRB00092553.

References

- 1.Alnot J., Liverneaux P., Silberman O. Lesions to the axillary nerve. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1996;82:579–589. [in French] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belsh J.M. Denervation. Encycl Neurol Sci. 2003:851–853. doi: 10.1016/B0-12-226870-9/00887-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentolila V., Nizard R., Bizot P., Sedel L. Complete traumatic brachial plexus palsy. Treatment and outcome after repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:20–28. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199901000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berliner J.L., Regalado-Magdos A., Ma C.B., Feeley B.T. Biomechanics of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24:150–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertelli J.A., Ghizoni M.F. Reconstruction of C5 and C6 brachial plexus avulsion injury by multiple nerve transfers: Spinal accessory to suprascapular, ulnar fascicles to biceps branch, and triceps long or lateral head branch to axillary nerve. J Hand Surg. 2004;29:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertelli J.A., Ghizoni M.F. Nerve transfer from triceps medial head and anconeus to deltoid for axillary nerve palsy. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39:940–947. doi: 10.1016/J.JHSA.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chim H., Kircher M.F., Spinner R.J., Bishop A.T., Shin A.Y. Triceps motor branch transfer for isolated traumatic pediatric axillary nerve injuries. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015;15:107–111. doi: 10.3171/2014.9.PEDS14245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi P.D., Novak C.B., Mackinnon S.E., Kline D.G. Quality of life and functional outcome following brachial plexus injury. J Hand Surg Am. 1997;22:605–612. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(97)80116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colbert S.H., Mackinnon S. Posterior approach for double nerve transfer for restoration of shoulder function in upper brachial plexus palsy. Hand (N Y) 2006;1:71–77. doi: 10.1007/S11552-006-9004-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desai M.J., Daly C.A., Seiler J.G., Wray W.H., Ruch D.S., Leversedge F.J. Radial to axillary nerve transfers: a combined case series. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41:1128–1134. doi: 10.1016/J.JHSA.2016.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drake G.N., O’Connor D.P., Edwards T.B. Indications for reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in rotator cuff disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:1526–1533. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1188-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujihara Y., Doi K., Dodakundi C., Hattori Y., Sakamoto S., Takagi T. Simple clinical test to detect deltoid muscle dysfunction causing weakness of abduction"Akimbo" test. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2012;28:375–379. doi: 10.1055/S-0032-1313772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallo R.A., Gamradt S.C., Mattern C.J., Cordasco F.A., Craig E.V., Dines D.M., et al. Instability after reverse total shoulder replacement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:584–590. doi: 10.1016/J.JSE.2010.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta R., Chan J.P., Uong J., Palispis W.A., Wright D.J., Shah S.B., et al. Human motor endplate remodeling after traumatic nerve injury. J Neurosurg. 2020;135:220–227. doi: 10.3171/2020.8.JNS201461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutkowska O., Martynkiewicz J., Urban M., Gosk J. Brachial plexus injury after shoulder dislocation: a literature review. Neurosurg Rev. 2020;43:407–423. doi: 10.1007/s10143-018-1001-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong T.S., Tian A., Sachar R., Ray W.Z., Brogan D.M., Dy C.J. Indirect cost of traumatic brachial plexus injuries in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101 doi: 10.2106/JBJS.18.00658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyun Y.S., Huri G., Garbis N.G., McFarland E.G. Uncommon indications for reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Surg. 2013;5:243–255. doi: 10.4055/cios.2013.5.4.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lädermann A., Walch G., Denard P.J., Collin P., Sirveaux F., Favard L., et al. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty in patients with pre-operative impairment of the deltoid muscle. Bone Joint Lett J. 2013;95-B:1106–1113. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B8.31173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landers Z.A., Jethanandani R., Lee S.K., Mancuso C.A., Seehaus M., Wolfe S.W. The psychological impact of adult traumatic brachial plexus injury. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43:950.e1–950.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2018.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee J.Y., Kircher M.F., Spinner R.J., Bishop A.T., Shin A.Y. Factors affecting outcome of triceps motor branch transfer for isolated axillary nerve injury. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:2350–2356. doi: 10.1016/J.JHSA.2012.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leechavengvongs S., Witoonchart K., Uerpairojkit C., Thuvasethakul P. Nerve transfer to deltoid muscle using the nerve to the long head of the triceps, part II: a report of 7 cases. J Hand Surg Am. 2003;28:633–638. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(03)00199-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Narakas A.O. The surgical treatment of traumatic brachial plexus lesions. Int Surg. 1980;65:521–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nolan B.M., Ankerson E., Wiater J.M. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty improves function in cuff tear arthropathy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:2476–2482. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1683-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perlmutter G.S. Axillary nerve injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;368:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Protzuk O., Schmidt R.C., Craig J.M., Weber M., Isaacs J., O’Connell R. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for irreparable rotator cuff tear after radial to axillary end-to-side transfer: a case report. JBJS Case Connect. 2024;14 doi: 10.2106/JBJS.CC.23.00526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richard E., Coulet B., Chammas M., Lazerges C. Morbidity of long head of the triceps motor branch neurotization to the axillary nerve: retrospective subjective and objective assessment of triceps brachii strength after transfer. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2022;24 doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2022.103280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salazar D.H., Chalmers P.N., Mackinnon S.E., Keener J.D. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty after radial-to-axillary nerve transfer for axillary nerve palsy with concomitant irreparable rotator cuff tear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26:e23–e28. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2016.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tay A.K.L., Collin P. Irreparable spontaneous deltoid rupture in rotator cuff arthropathy: the use of a reverse total shoulder replacement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:e5. doi: 10.1016/J.JSE.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tôrres Jácome D., Henrique Uchôa de Alencar F., Vinícius Vieira de Lemos M., Nunes Kobig R., Francisco Recalde Rocha J. Axillary nerve neurotization by a triceps motor branch: comparison between axillary and posterior arm approaches. Rev Bras Ortop. 2018;53:15. doi: 10.1016/j.rboe.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiater B.P., Koueiter D.M., Maerz T., Moravek J.E., Yonan S., Marcantonio D.R., et al. Preoperative deltoid size and fatty infiltration of the deltoid and rotator cuff correlate to outcomes after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:663. doi: 10.1007/S11999-014-4047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Witoonchart K., Leechavengvongs S., Uerpairojkit C., Thuvasethakul P., Wongnopsuwan V. Nerve transfer to deltoid muscle using the nerve to the long head of the triceps, part I: an anatomic feasibility study. J Hand Surg Am. 2003;28:628–632. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(03)00200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]