Abstract

As a potent and convenient genome-editing tool, Cas9 has been widely used in biomedical research and evaluated in treating human diseases. Numerous engineered variants of Cas9, dCas9 and other related prokaryotic endonucleases have been identified. However, as these bacterial enzymes are not naturally present in mammalian cells, whether and how bacterial Cas9 proteins are recognized and regulated by mammalian hosts remain poorly understood. Here, we identify Keap1 as a mammalian endogenous E3 ligase that targets Cas9/dCas9/Fanzor for ubiquitination and degradation in an ‘ETGE’-like degron-dependent manner. Cas9-‘ETGE’-like degron mutants evading Keap1 recognition display enhanced gene editing ability in cells. dCas9-‘ETGE’-like degron mutants exert extended protein half-life and protein retention on chromatin, leading to improved CRISPRa and CRISPRi efficacy. Moreover, Cas9 binding to Keap1 also impairs Keap1 function by competing with Keap1 substrates or binding partners for Keap1 binding, while engineered Cas9 mutants show less perturbation of Keap1 biology. Thus, our study reveals a mammalian specific Cas9 regulation and provides new Cas9 designs not only with enhanced gene regulatory capacity but also with minimal effects on disrupting endogenous Keap1 signaling.

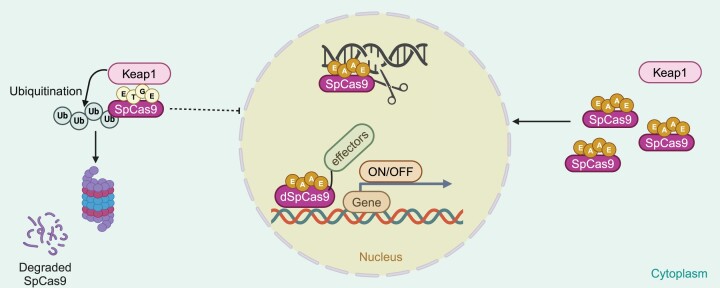

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) and CRISPR-associated proteins (Cas) provide an adaptive immune defense mechanism against phage for many bacteria. Cas proteins, especially Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) and Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 (SaCas9), have been repurposed to provide a potent and convenient mammalian genome-editing tool (1,2). Cas protein-driven gene editing has been widely used in biomedical research as a loss-of-function approach to study the function of genes (3) and enhancer elements (4), and to screen for new drug targets (5,6). More recently, it has been increasingly investigated for the treatment of human diseases (see (7) for review), including Barth Syndrome (8), Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (9,10), blindness (11), deafness (12), cancer (13), HIV infection (14), transthyretin amyloidosis (15), heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (16), and many others. Notably, Cas protein-driven gene editing has also been used to generate murine models by replacing traditional gene knockout and knockin approaches to recapitulate human genetic diseases (17), and more importantly, has demonstrated the ability to correct the disease mutation(s) in mouse (9,17–19) and dog (20). Excitingly, Cas-induced gene editing has been initiated in human clinical trials, including edited T cells for enhanced immune-therapies (7) to treat β-thalassemia (NCT03655678) and sickle cell disorders (NCT03745287). Recently, FDA approved the first therapeutic usage of CRISPR to correct the genetic defect causing sickle cell disease.

Although CRISPR is the source of many breakthroughs in both biomedical research and disease therapy, technical limitations still exist. These limitations include the restrictions imposed by availabilities of specific PAM (protospacer adjacent motif) sequences for Cas9 recognition, unexpected DNA damage caused by Cas9 (21), Cas9 off-target effects, instability of the sgRNAs (single guide RNA) in cells, unwanted sustained Cas9 activity and others. To overcome these drawbacks, extensive efforts have been devoted to further improving and broadening the power and applications of Cas9 in both biomedical research and clinical settings. These efforts include but not limited to finding new Cas9 species with altered and expanded PAM sequence recognition (22), additional prokaryotic endonucleases such as Cpf1 (also named Cas12a) (23), CasY (24) and CasX (25) or the eukaryotic endonuclease Fanzor (26), engineered Cas9 enzymes with improved fidelity (27–29), base editors to rewrite the genome by directly editing DNA bases (30), dCas9 (catalytic-dead Cas9)-fusions to modulate epigenome (31,32), natural Cas9 inhibitors (33), controlled Cas by small molecules (34) and others. In addition, manipulating DNA damage responses by inhibiting NHEJ (non-homologous end joining) (35) via inhibiting DNAPK (36), or enhancing HDR (homology directed repair) by small molecules (37) led to improved and enhanced CRISPR techniques. Modifying sgRNAs by engineering a tRNA–gRNA architecture (38) also further expanded the capacity for CRISPR-mediated gene editing. There are also other efforts we have not covered here. However, as Cas9 is originally identified in prokaryotes and naturally it does not express in mammalian cells, whether and how mammalian hosts recognize and respond to the foreign bacterial Cas9 protein remains unclear. This is an important topic for the safe and effective application of Cas enzymes in gene therapies.

Materials and methods

Materials

MG132 (S2619), cycloheximide (S6611), bortezomib (S1013) and sulforaphane (S5771) were purchased from Selleckchem. Puromycin (P8833), anti-Flag agarose beads (A-2220), anti-HA agarose beads (A-2095), glutathione agarose beads (G4510), Tris Base (648311), NaCl (S9888) and the Keap1 inhibitors tBHQ (112941) and CDDO (SMB00376) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Nickel-NTA agarose beads (H-350-5) were purchased from Goldbio. Polyethylenimine (PEI, 23966) was purchased from Polysciences. NP-40 (AAJ61055AP) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Antibodies

All antibodies were used at a 1:2000 dilution in the TBST (1× Tris-buffered saline, 0.1% Tween 20) buffer with 5% non-fat milk for western blotting analyses. Anti-HA antibody (3724), anti-Keap1 antibody (8047), anti-IKKβ-antibody (8943), anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked antibody (7074) and anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked antibody (7076) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-NRF2 antibody (ab62352) was purchased from Abcam, Inc. Anti-p27-antibody (sc1641) and anti-GFP-antibody (sc4304) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Polyclonal anti-Flag antibody (F-2425), monoclonal anti-Flag antibody (F-3165, clone M2) and anti-Tubulin antibody (T-5168) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cell culture and transfection

HEK293, HEK293T, MEF (mouse embryonic fibroblast), BPH1, HeLa, HBE (human bronchial epithelial cell) and H520 (lung cancer) cells were cultured in DMEM medium (Gibco 11965092) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco 16000044), 100 units of penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco 15140122). HEK293, HEK293T and HeLa cells were purchased from UNC Lineberger TCF (tissue culture facility). MEF cells were obtained from Dr. Wenyi Wei Lab (BIDMC, Harvard Medical School). HBE (transformed by Bmi-1/hTERT as described in (39)) and H520 (human epithelial lung squamous cell carcinoma, as ATCC-HTB-182) cells were obtained from Dr Gang Greg Wang Lab (Duke University). BPH1 cells (a benign hyperplastic prostatic epithelial cell line, as Sigma-Aldrich SCC256) were obtained from Dr Haojie Huang Lab (Mayo Clinic). Cell transfection was performed by polyethylenimine (PEI) as described previously (40,41). Briefly, 100 ng to 3 μg indicated DNA plasmids were mixed with PEI (1:3 ratio) in Opti-MEM medium and vortexed, followed by incubation at room temperature (RT) for 15 min before gently dropping into cell culture media. Packaging of lentiviral shKeap1 viruses and subsequent infection of various cell lines to generate stable endogenous Keap1 depleted cells were performed according to the protocols described previously (42,43). Briefly, 2.5 μg shKeap1 plasmid, 1.25 μg VSVG and 1.25 μg Δ8.9 plasmids were co-transfected into HEK293T cells in 10 cm dishes to package virus. Medium was refreshed 24 h post-transfection. 10 ml medium from each transfection was collected each day for two consecutive days. Collected virus-containing media was pooled and filtered through 0.45 μM filter. Indicated Cells were infected with indicated virus in the presence of polybrene for 24 h followed by a recovery period of 24 h with fresh medium. Then, cells were selected for 3 days using 1 μg/ml puromycin to eliminate non-infected cells.

Plasmid construction

pLenti-V2-Flag-SpCas9 (52961), eSpCas9 (71814), HF1-SpCas9 (92012) and Flag-PALB2 (71114) were purchased from Addgene. The parental HA-SaCas9 vector was generated in Dr. Charles Gersbach Lab (Duke University) (44). Flag-Fanzor1 was cloned into pLenti-GFP-puro vector (Addgene 17448) by AgeI and XhoI sites. HA-dSpCas9-WT-CRAB, HA-dSpCas9-WT-p300, HA-dSpCas9-WT-VPR, HA-dSpCas9-WT-FKBP and HA-dSpCas9-WT-suntagx10 were generated by Nate Hathaway Lab (UNC-Chapel Hill) (45). All the Cas9-related mutations were generated using the QuikChange XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (200516,Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. HA-Keap1 was cloned into the pCDNA3.0-HA vector with BamHI and XhoI sites. HA-Keap1-C151S, C273S and C288S mutants were generated using the QuikChange XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (200516,Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. HA-Keap1-G423V, D422N, G333C, Kelch and ΔKelch plasmids were cloned into pCDNA3.0-HA vector with BamHI and XhoI using a Flag-Keap1 plasmid as the template published in a previous study (46). Flag-NRF2 was cloned into pCDN3.0 backbone with BamHI and XhoI sites. shRNA vectors for depleting endogenous Keap1 including shKeap1-7, -11 and -83 were generated in a previous study (46). sgRNAs for CRISPR-SpCas9 mediated deletion of target genes were generated by cloning the annealed sgRNA oligos into BbsI-digested phU6-sg vector (addgene 53188) as described previously (41). sgRNAs for CRISPR-SaCas9 mediated deletion of target genes were generated by cloning the annealed sgRNA oligos into BbsI-digested phU6-sg vector for SaCas9 (pDO240-pZDonor-SaCas9-hU6-gRNA, from Dr Charles Gersbach Lab, Duke University). Primers used for all vector constructions were listed in Supplementary Table S1. The vector sequence for pDO240-pZDonor-SaCas9-hU6-gRNA is listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation analyses

Cells were washed with sterile 1× PBS and lysed in EBC buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40) supplemented with protease inhibitors (B14002, Selleckchem) and phosphatase inhibitors (B15002, Selleckchem). The protein concentrations of whole cell lysates were determined by NanoDrop OneC (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the Bio-Rad protein Bradford assay reagent (5000006, Bio-Rad) as described previously (40). Equal amounts of whole cell lysates (WCLs) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with indicated antibodies. For immunoprecipitation analyses, 1 mg WCLs were incubated with indicated antibody-conjugated agarose beads for 3–4 h at 4°C with rotations. Then immuno-complexes were washed three times with NETN buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 0.5% NP-40), resuspended in 3xSDS sample buffers, and boiled at 95°C on heat block before resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with indicated antibodies. Uncropped and unprocessed original scans for all western blotting images were provided in Supplementary Figure S8.

RMSD measurements

The structure for SpCas9’s ‘ETGE’ motif was obtained from PDB: 2flu and the NRF2’s ‘ETGE’ motif was obtained from PDB: 4oo8. RMSD calculations were made using an in-house python script which takes the average distance between optimal rigid body superpositions of each protein's Cα backbone carbons. Calculations were made using the ‘ETGE’ motif and the following three C-terminal and N-terminal flanking amino acids. Each structure was then compared to their respective full-length AlphFold2 generated structures; these were then compared in a similar fashion wherein similar values were obtained.

Mass spectrometry analyses to identify flag-SpCas9 interacting proteins

EV (empty vector) and Flag-SpCas9 constructs were transfected into HEK293T cells, respectively. 48 h post-transfection, cells were harvested with EBC buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40) with PI (protease inhibitor cocktail) and PPI (protein phosphatase inhibitor cocktail). 3 mg of WCL was used for Flag-M2 agarose beads mediated immunoprecipitations with gentle rotations at 4°C for 4 h. Flag-immunoprecipitants were washed with NETN buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 0.5% NP-40) for 4 times. Proteins were diluted using 8 M urea (U4883, Sigma-Aldrich) to 100 μg/μl and then subjected to FASP trypsin digestion protocol. Briefly, proteins were reduced using 50 mM DTT (A39255, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 15 min at 65°C and diluted with 200 μl of 8 M urea. Then samples were transferred into 30K MWCO spin filter (14‐558‐349, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for centrifuging at 10 000 × g for 30 min at room temperature. The proteins were washed twice using 200 μl of 8 M urea at 10 000 × g for 30 min at room temperature. Then, proteins were alkylated using 100 μl of 15 mM 2‐chloroacetamide (148415000, Thermo Fisher Scientific) diluted in 8 M urea for 20 min in the dark at room temperature. The spin filter was washed twice at 10 000 × g for 20 min at room temperature. Then, the buffer was exchanged with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (ABC) pH 8.0 at 10 000 × g for 15 min at room temperature. 100 μl of 50 mM ABC was added into the spin filter with 2.5 μg of trypsin (V511C, Promega). Samples were trypsinized overnight at 37°C for 18 h. Following trypsinization, peptides were recovered in a new receiver tube by centrifugation at 10 000 × g for 15 min. Peptides were eluted twice using 50 μl 0.5% TFA in water at 10 000 × g for 10 min. Samples were then concentrated to 100 μl using a Savant™ SPD131DDA SpeedVac Concentrator (Thermo Fisher Scientific) followed by C18 column desalting (89870, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples were then concentrated and resolubilized in 100 μl of LC‐Optima MS‐grade water using Savant™ SPD131DDA SpeedVac Concentrator. Ethyl acetate extraction followed by Savant™ SPD131DDA SpeedVac Concentrator was performed to remove residual detergents. QFP (quantitative peptide assays and standards) (23290, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was performed for peptide quantification.Detailed liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry methods and data filtering methods were described previously (47). Data was searched using MaxQuant (version 1.6.6.7), and all statistical analyses were done in Perseus (version 1.6.3.4). The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE (48) partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD050935.

T7E1 gene editing assays

Three-day post-transfection with indicated DNA constructs, cells were washed with sterile 1× PBS and collected by trypsinization and centrifugation. Genomic DNA was extracted from cell pellets using QuickExtract™ DNA Extraction Solution (Biosearch technology SS000035-D2) following manufacturer's instructions. End-point PCR was performed using 10 μl genomic DNA as the template with indicated primers in the presence of high-fidelity Taq DNA polymerase (M7122, Promega). PCR products were verified by DNA electrophoresis in 1× TAE buffer and purified by PCR cleanup kits (BS664, Bio Basic, Inc). 600–800 ng PCR products from control or indicated Cas9-expressing cells were mixed, denatured and then annealed to generate small indels in hybridization products. 1 μl T7 Endonuclease I (NEB M0689) was added and the reactions were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Digested PCR products were resolved by 2% TAE DNA agarose gel electrophoresis. Indels were calculated using the intensities of T7 digested bands normalized to the sum of both full-length and digested bands quantified by ImageJ.

Sanger sequencing and TIDE analyses for gene knockout efficacy

Three-day post-transfection with indicated DNA constructs, genomic DNA was extracted using QuickExtract™ DNA Extraction Solution following manufacturer's instructions. A region of ∼500 bp flanking the target site was amplified by PCR with indicated primer pairs. PCR amplicons were purified and subjected to Sanger sequencing by GENEWIZ, Inc. TIDE analyses (https://tide.nki.nl/) was performed to calculate the total gene editing efficiency. Biological duplicates were used to generate error bars. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA tests. Primers used for all sanger sequencing were listed in the Supplementary Table S3.

CRISPRa (dCas9-fusion CRISPR) assays and flow cytometry analyses

500000 cells per well were plated in a 6-well plate and 24 h later, cells were transfected with 3 μg DNA and 9 μl PEI mixed in 200 μl Opti-MEM medium. For experiments using p300 fusion plasmids, 1.5 μg dCas9-p300, 1 μg sgRNA and 0.5 μg tre3g-GFP plasmids were transfected into cells. 16-h post-transfection, the medium was refreshed. For CRISPRa assays targeting endogenous genes, 2 μg dCas9-p300 plasmid and 1 μg sgRNA vector (0.25 μg per gRNA) were used. The medium was refreshed 16-hour post-transfection. Alternatively, 100 000 cells per well were plated into a 12-well plate and transfected with 1 μg DNA and 3 μl PEI mixed in 100 μl Opti-MEM medium. For each transfection, 0.35 μg sgRNA, 0.15 μg tre3g-BFP vector, and 0.5 μg dCas9 plasmid were used (except for dCas9-SunTag, where 0.35 μg dCas9 and 0.15 μg scFv-VP64 plasmids were used). The indicated time course experiments started 24 h post-media change. To quantify the BFP or GFP expression, cells were dissociated with 0.05% Trypsin for 8 min, quenched by media with 10% FBS and spun down at 1700 RPM for 5 min. The pellet was washed with 1× PBS and resuspended in FACS buffer (1 mM EDTA and 0.2% BSA in 1× PBS). Flow cytometry was performed with the Thermo Fisher Attune NxT and the data was analyzed with the Flow Jo Software.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

Three days post-transfection, total RNA was extracted using RNA extraction kits (BS584, Bio Basic) following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were washed with sterile 1× PBS and resuspended in RLT solution and passed through QIAshredder columns for homogenization (QIAGEN 79656). Equal volume of 70% ethanol was added and mixed. Mixtures were transferred to EZ-10 columns with 2 ml collection tubes and spun at 6000 × g for 1 min. 500 ul RW and RPE solutions were added to the columns, respectively, to clean up the RNA. Total RNA was collected in a RNase-free 1.5 ml microtube with 50 μl RNase-free water with centrifugation at 8000 × g for 1 min. The RNA concentrations were determined by Nanodrop OneC Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). cDNA was synthesis using iScriptTM cDNA Synthesis Kit (1708890, Bio-Rad) following manufacturer's instructions. qRT-PCR was performed with QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using iTaq universal SYBR green supermix (1725124, Bio-Rad). Briefly, the PCR reaction was composed of 4 μl cDNA template (20 X dilution after cDNA synthesis), 5 μl iTaq Mix and 1 μl 5 μM primer mix in a 10 μl volume. The comparative Ct method was used to calculate fold changes in gene expression, which was normalized to U6 snRNA as a house-keeping gene. Biological triplicates were used to generate error bar. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA tests. Primers used for testing gene expression were listed in the Supplementary Table S4.

DMD mouse model study

ITR-containing plasmids, AAV-2XgRNA (9), AAV-WT-SaCas9 (9) and AAV-AEGA-SaCas9 were generated in Dr Charles Gersbach‘s Lab (Duke University). Intact ITRs were verified by SmaI digest on all vectors before AAV production. AAV9 was produced by the Duke University Viral Vector Core and titers were measured by qPCR with a plasmid standard curve. Animal studies were conducted with strict adherence to the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Duke University. Neonatal 2-day-old (P2) mdx mice (Jackson Labs) were administered AAV by intravenous injection through the facial vein with 40ul AAV vector per mouse (7.2e11vg AAV-2XgRNA and 2.2e11vg AAV-WT-SaCas9 or AAV-AEGA-SaCas9. At 8 weeks post-injection, mice were euthanized and tibialis anterior muscle tissue was collected. Protein analysis with western blot and genomic DNA analysis with endpoint PCR were performed as described previously (9). In brief, protein lysate was loaded onto NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen) with MOPS buffer (Invitrogen), transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and blocked overnight. Blots were probed with anti-HA (abcam) for Cas9 detection, MANDYs8 (Sigma D8168) for dystrophin detection, and rabbit anti-GAPDH (Cell Signaling), followed by mouse or rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz) and visualized using Western-C ECL substrate (Biorad) on a ChemiDoc chemiluminescence system (Biorad). In brief, genomic DNA was isolated using the DNeasy kit (Qiagen) and endpoint PCR was performed with primers flanking the Cas9 cut sites (5′-TACACTAACACGCATATTTG, 5′-CATTGCATCCATGTCTGACT) to amplify a 1638 bp unedited region or the expected 467 bp deletion product. PCR products were electrophoresed in a 1% agarose gel and viewed on a BioRad GelDoc imager.

Statistics

Differences between control and experimental conditions were evaluated by Student's t test or One-way ANOVA. These analyses were performed using the SPSS 11.5 Statistical Software and P≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Keap1 is a mammalian endogenous SpCas9 binding protein.

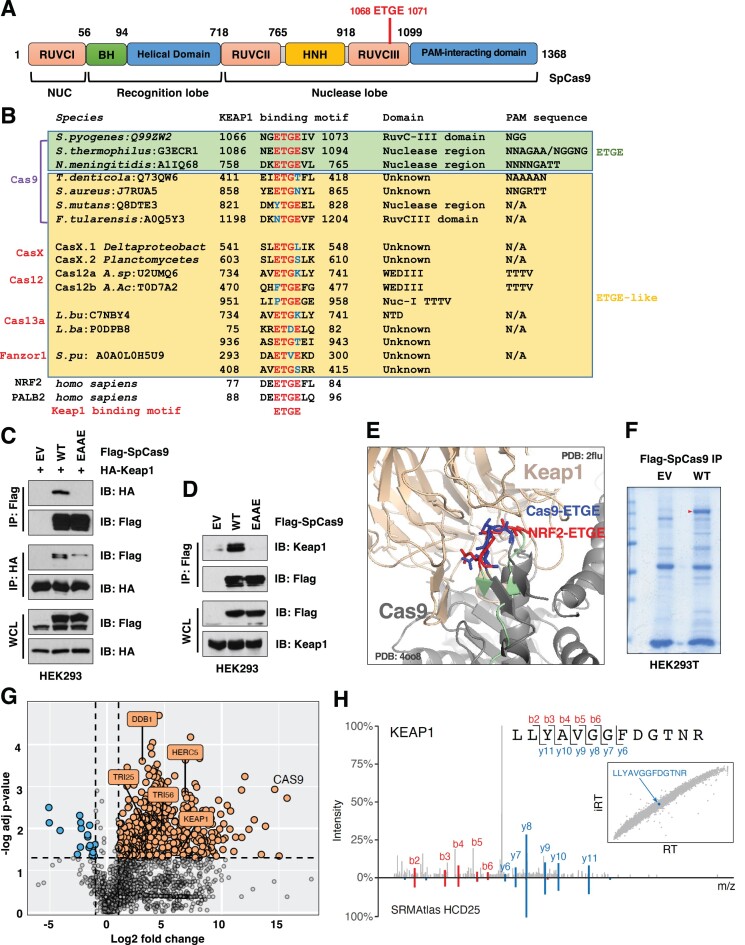

We reasoned that understanding mammalian specific Cas9 recognition and regulation mechanisms will provide the guidance to engineering Cas9 variants with enhanced gene modulating ability, including improved robustness and/or fidelity. This will also help understand how this bacterial protein may interfere with mammalian signaling networks. Cas9 has been found to undergo sumoylation in mammalian cells, which stabilizes Cas9 proteins and enhances DNA binding (49). A close examination of SpCas9 protein sequence led us to find a canonical E3 ligase Keap1 (Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1) degron sequence (1068ETGE1071) located in its RuvC III domain critical for SpCas9 enzyme activity (Figure 1A). Interestingly, an ‘ETGE’-like motif is present in most bacterial Cas9 species such as CasX, Cas12, Cas13a and the eukaryotic enzyme Fanzor (26) (Figure 1B). Mutating the Keap1 degron ‘ETGE’ to ‘EAAE’ in SpCas9 led to reduced Keap1 binding in human cells (Figure 1C, D), suggesting that Keap1 is largely reliant on the degron sequence for SpCas9 recognition. Notably, co-expression of sgRNAs did not affect SpCas9 binding to Keap1 (Supplementary Figure S1A), nor SpCas9 expression (Supplementary Figure S1B). The notion that ‘ETGE’ is the key motif in SpCas9 for Keap1 recognition was further supported by a structure simulation demonstrating that structurally the ‘ETGE’ motif in SpCas9 resembled the conformation of the ‘ETGE’ domain in a well-characterized Keap1 substrate NRF2 (50) (Figure 1E). We further calculated the RMSD (root mean square deviation) between SpCas9 ‘ETGEIV’ and NRF2 ‘ETGEFL’ structures as 1.078 Å (Supplementary Figure S1C), which further confirms the structural similarity between these two motifs. Moreover, we established the SpCas9 interactome in HEK293T cells by proteomics (Figure 1F, G) and found unique Keap1 peptides (Figure 1H) along with other E3-related proteins (Supplementary Figure S1D) as potential SpCas9 interacting partners. Together, these data indicate Keap1 is a putative endogenous mammalian protein interacting with SpCas9.

Figure 1.

Keap1 interacts with SpCas9 in an ‘ETGE’ degron-dependent manner. (A) A cartoon illustration of SpCas9 protein domain structures with the putative Keap1 degron ‘ETGE’ labeled in red. (B) A protein sequence alignment for indicated Cas9 or Cas9-like proteins from indicated species with UniProt numbers. Potential Keap1 ‘ETGE’ or ‘ETGE’-like motifs are indicated. (C, D) Immunoblot (IB) analysis of whole cell lysates (WCL) and Flag-immunoprecipitants (IP) derived from HEK293 cells transfected with HA-Keap1 and/or indicated Flag-SpCas9 constructs for 48 h. (E) A structure simulation by PyMOL indicating that the SpCas9-ETGE motif (blue, PDB: 4oo8) exerts a similar structure topology as NRF2-ETGE motif (red, PDB: 2flu). (F) A representative Coomassie staining image for SDS-PAGE for Flag-IPs derived from HEK293T cells transfected with EV or WT-SpCas9 for 48 h. (G) A volcano plot indicating that multiple E3 ubiquitin ligases were identified from a proteomic analysis using samples from (F) to establish a SpCas9 interactome. (H) A representative tandem mass spectrum indicating identification of the KEAP1 peptide from SpCas9 interactome along with a reference spectrum from the SRMAtlas (80) database. Inset: Correlation between observed retention times (RT) and Chronologer (81) predicted retention times (iRT).

Keap1 targets SpCas9 for ubiquitination and degradation in an ‘ETGE’ degron-dependent manner.

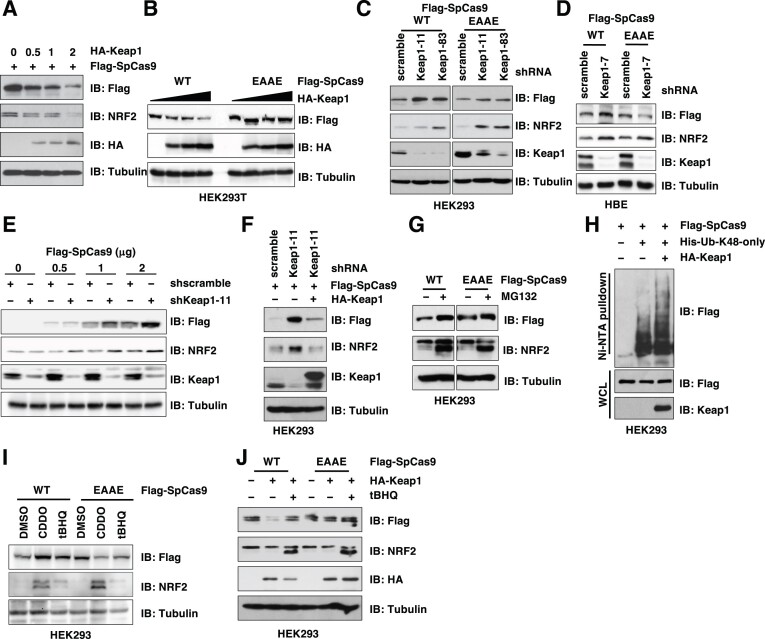

Given that Keap1 either binds and earmarks protein substrates for destruction such as NRF2 (nuclear factor erythroid-related factor 2) (51), or binds and suppresses its binding partner's function such as PALB2 (partner and localizer of BRCA2) (52), we next examined whether and how Keap1 controls SpCas9 protein function. We found that SpCas9 bound the Keap1-Kelch domain (Supplementary Figure S2A, B) responsible for Keap1 substrates binding (53). As a result, Keap1 targeted SpCas9 for degradation in a Keap1 dose-dependent (Figure 2A and Supplementary Figure S2C) and SpCas9 ‘ETGE’ degron-dependent manners in cells (Figure 2B and Supplementary Figure S2D). More importantly, depletion of endogenous Keap1 led to accumulated WT-SpCas9, but not EAAE-SpCas9 proteins (Figure 2C, D and Supplementary Figure S2E). Interestingly, increased SpCas9 expression upon Keap1 depletion was observed even at conditions where the quantity of SpCas9 used was significantly exceeded the standard recommendations for gene editing (54) (Figure 2E). Notably, Keap1 depletion did not significantly affect mRNA levels of these transfected SpCas9s in cells (Supplementary Figure S2F). Together, these data suggest that depletion of endogenous Keap1 is likely to cause SpCas9 protein accumulation. Notably, re-introducing an shKeap1-resistant version of WT-Keap1 reduced expression of SpCas9 (Figure 2F), alleviating concerns from off-target effects derived from shKeap1. To further support a role of proteasome-mediated SpCas9 protein stability control, we found that blocking the 26S proteasome by either MG132 or bortezomib increased SpCas9 protein levels in a Cas9 ‘ETGE’ degron-dependent manner (Figure 2G and Supplementary Figure S2G, H). Given that poly-ubiquitination occurs via eight distinctive ubiquitin linkages that determine the fate of poly-ubiquitinated proteins (55), we found that SpCas9 was mainly modified by K48-linked poly-ubiquitination in cells (Supplementary Figure S2I) and Keap1 robustly promoted this K48-linked poly-ubiquitination (Figure 2H) to facilitate its degradation. As such, ectopic Keap1expression significantly shortened WT-SpCas9 protein half-life (Supplementary Figure S2J), while SpCas9-EAAE displayed extended protein half-life (Supplementary Figure S2K), presumably due to its inability to be recognized and degraded by Keap1.

Figure 2.

Keap1 targets SpCas9 for ubiquitination and degradation. (A, B) IB analysis of WCL derived from HEK293T cells transfected with indicated Flag-SpCas9 and indicated doses of HA-Keap1 cDNA (μg) for 48 hrs. (C) IB analysis of WCL derived from control or endogenous Keap1-depleted HEK293 cells by shRNAs transfected with either WT- or EAAE-SpCas9 constructs for 48 h. (D) IB analysis of WCL derived from control or endogenous Keap1-depleted HBE cells by shRNAs transfected with either WT- or EAAE-SpCas9 constructs for 48 h. (E) IB analysis of WCL derived from control or endogenous Keap1-depleted HEK293 cells by shRNAs transfected with indicated doses of WT-SpCas9 construct (μg) for 48 h. (F) IB analysis of WCL derived from control or endogenous Keap1-depleted HEK293 cells by shRNAs transfected with indicated Flag-SpCas9 and HA-Keap1 (resistant to shKeap1) constructs for 48 h. (G) IB analysis of WCL derived from HEK293 cells transfected with either WT- or EAAE-SpCas9 constructs for 48 h. Where indicated, 10 μM MG132 was added to cell culture media overnight before cell collection. (H) IB analysis of Ni-NTA pulldowns and WCL from HEK293 cells transfected with indicated DNA constructs for 48 h. 10 μM MG132 was added to cell culture media overnight before cell collection. (I, J) IB analysis of WCL derived from HEK293 cells transfected with either WT- or EAAE-SpCas9 constructs and treated with indicated compounds. Where indicated, DMSO, CDDO (50 nM) or tBHQ (10 μM) was added to cell culture media for 16 h before cell collection.

In addition to Keap1 knockdown, inactivating Keap1 by pharmacological inhibitors including Keap1 cysteine modifying agents tert-butyl hydroxyquinone (tBHQ) and sulforaphane, or chemicals blocking Keap1 binding to cullin 3 such as CDDO (2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9(11)-dien-28-oic acid), similarly led to accumulation of WT, but not EAAE-SpCas9 proteins in cells (Figure 2I and Supplementary Figure S2L, M). Moreover, tBHQ treatment blocked Keap1-mediated WT-SpCas9 degradation (Figure 2J and Supplementary Figure S2N) presumably by attenuating Keap1 binding to SpCas9 (Supplementary Figure S2O). These data further support the notion that SpCas9 is a Keap1 substrate.

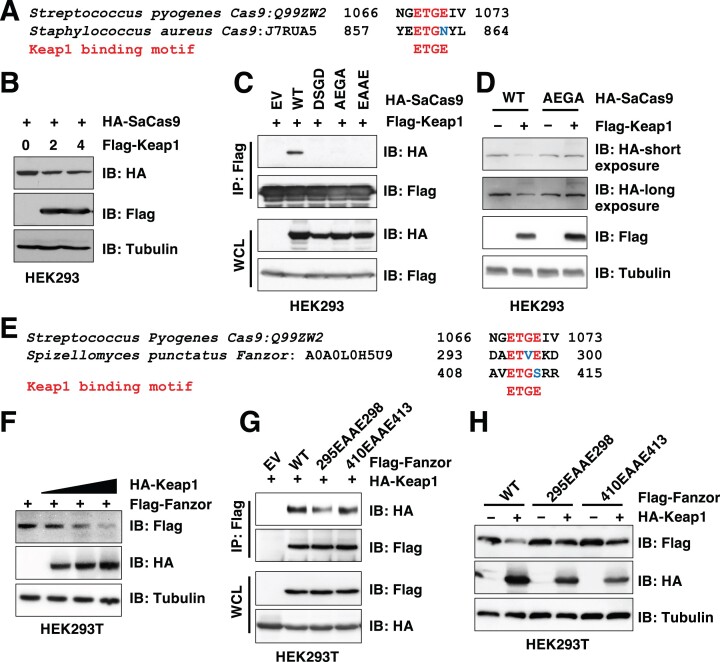

Keap1 also targets Cas9s from other bacteria species and eukaryotic fanzor for degradation.

Given that the ‘ETGE’-like motif is present in multiple Cas9 species (Figure 1B) used for gene editing, next we examined if protein stability of other Cas proteins is also regulated by Keap1. To this end, we found that similar to WT-SpCas9, versions of SpCas9s engineered for higher fidelity (including HF1-SpCas9 (28) and eSpCas9 (27)) were also subjected to Keap1-mediated degradation (Supplementary Figure S3A). Moreover, S. aureus Cas9 (SaCas9) with an ‘ETGN’ motif (Figure 3A), that has been widely used in in vivo CRISPR gene editing due to its smaller size than SpCas9 for adenovirus packaging, could be targeted by Keap1 for degradation as well (Figure 3B). We found that mutating the first conserved Keap1 degron ‘ETGN’ to either ‘DSGD’, ‘AEGA’ or ‘EAAE’ efficiently reduced its binding to Keap1 (Figure 3C). Notably, both DSGD- and EAAE-SaCas9 mutants displayed reduced protein expression levels in cells, while the AEGA-SaCas9 mutant expressed comparably to WT-SaCas9 (Supplementary Figure S3B–D). Thus, we focused on AEGA-SaCas9 in this study. Consistent with AEGA-SaCas9 being deficient in binding Keap1 (Figure 3C), this mutant was resistant to Keap1-mediated degradation in cells (Figure 3D). Like SpCas9, Keap1 also robustly promoted K48-linked SaCas9 poly-ubiquitination in cells (Supplementary Figure S3E, F), confirming that Keap1 targets SaCas9 for ubiquitination and destruction (Supplementary Figure S3G). Recently, a eukaryotic programmable RNA-guided endonuclease Fanzor was discovered as an OMEGA system with a genome engineering capacity (26). Fanzor proteins also contain two ‘ETGE’-like motifs, including ‘ETVE’ and ‘ETGS’ (Figure 3E). In cells, Fanzor was degraded by Keap1 in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3F). Mutating the ‘ETVE’ but not the ‘ETGS’ motif to ‘EAAE’ led to reduced Fanzor binding to Keap1 (Figure 3G) and subsequent resistance to Keap1-mediated degradation in cells (Figure 3H). Together, these data suggest that Keap1 may function as a mammalian E3 ligase recognizing and targeting Cas9 and Fanzor for degradation in cells.

Figure 3.

Keap1 binds and targets SaCas9 and Fanzor for degradation. (A, E) The protein sequence alignment for potential ‘ETGE’-like motifs from SaCas9 (A) and Fanzor (E) to SpCas9. (B, D) IB analyses of WCL from HEK293 cells transfected with HA-SaCas9 and indicated amounts of Flag-Keap1 constructs (μg) for 48 h. (C) IB analyses of Flag-IP and WCL from HEK293 cells transfected with indicated HA-SaCas9 constructs with Flag-Keap1 for 48 h. (F) IB analyses of WCL from HEK293T cells transfected with Flag-Fanzor with increasing doses of HA-Keap1 constructs for 48 h. (G) IB analyses of Flag-IPs and WCL from HEK293T cells transfected with HA-Keap1 and indicated Flag-Fanzor constructs for 48 h. (H) IB analyses of WCL from HEK293T cells transfected with indicated Flag-Fanzor constructs with or without HA-Keap1 for 48 h.

Engineered Cas9 mutants evading Keap1 recognition exert enhanced gene editing ability in cells.

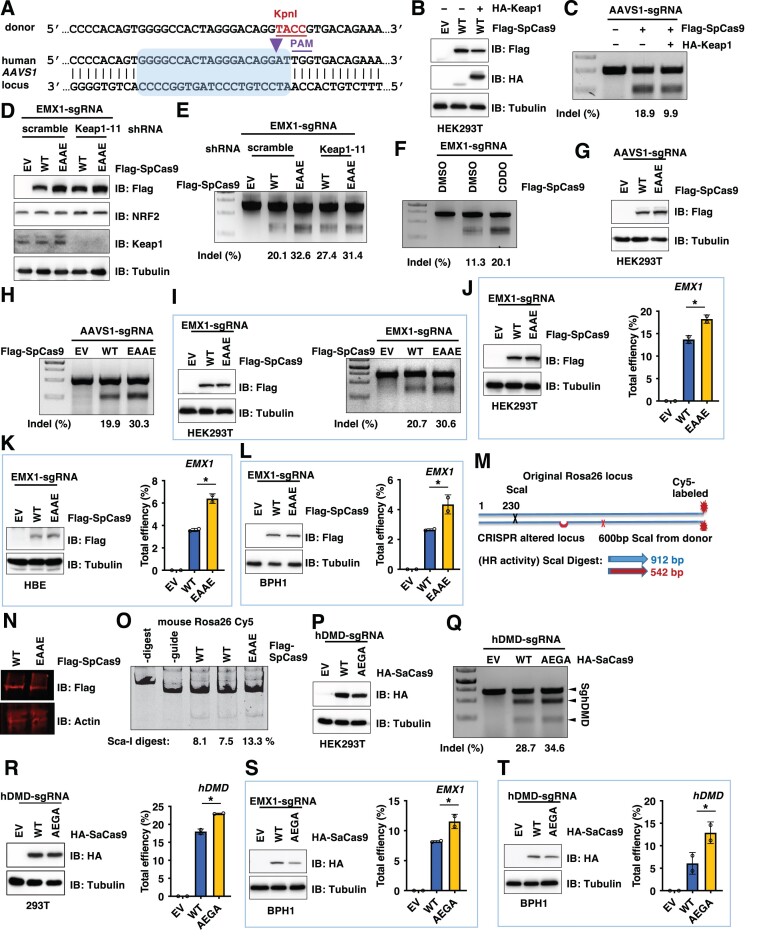

Next, we examined if evading Keap1-mediated Cas9 protein degradation leads to enhanced gene editing ability. Hereafter we will use SpCas9 and SaCas9 for in-cell and in vivo gene editing tests, respectively, due to their size differences. To test the in-cell gene editing efficiency, we engineered sgRNAs and donor DNA to target the safe human endogenous AAVS1 locus to measure both gene knockout (CRISPRko) and knockin (CRISPRki) efficiency (Figure 4A). Consistent with SpCas9 being degraded by Keap1 (Figure 2A), introducing exogenous Keap1 reduced SpCas9 protein levels (Figure 4B) and subsequently attenuated Cas9-mediated AAVS1 editing efficiency in HEK293T cells using T7E1 assays for indel measurements (Figure 4C). On the other hand, depletion of endogenous Keap1 in HEK293 cells resulted in protein accumulation of WT-, but not EAAE-SpCas9 (Figure 4D). As a result, Keap1 depletion led to increased EMX1 and AAVS1 gene editing efficiency in WT-SpCas9, but not in EAAE-SpCas9 expressing cells (Figure 4E and Supplementary Figure S4A), which positively correlated with SpCas9 protein levels. Consistent with Keap1 being a gene editing suppressor, pharmacological Keap1 inhibition by CDDO increased SpCas9-mediated EMX1 gene editing in HEK293T cells (Figure 4F).

Figure 4.

Engineered Keap1-degron mutated SpCas9 or SaCas9 variants display enhanced Cas9-mediated genome editing ability in vitro. (A) An illustration of the sgRNA sequence targeting the human AAVS1 locus used in CRISPR-mediated knockout efficiency tests and the guide RNA sequence used in this study to introduce a KpnI site for knockin efficacy tests. (B) IB analysis of WCL derived from HEK293T cells transfected with Flag-SpCas9 with or without HA-Keap1 constructs for 72 h. (C, E, F, H, Q) Representative DNA agarose gel images of standard T7E1 assays derived from HEK293T cells transfected with indicated Cas9 and sgRNA performed 3-day post-transfection. Indel% was calculated and presented to indicate target gene editing efficiency. (D) IB analysis of WCL derived from control or endogenous Keap1-depleted HEK293T cells transfected with indicated Cas9 constructs and EMX1-sgRNAs. Where indicated, lentiviruses for shscramble or shKeap1-11 were used to infect HEK293 cells for 24 h followed by 72 h selection with 1 μg/ml puromycin to eliminate non-infected cells. (G) IB analysis of WCL derived from HEK293T cells transfected with EV (empty vector), WT- or EAAE-SpCas9-Flag and AAVS1-sgRNAs for 72 h. (I) Left: IB analysis of WCL derived from HEK293T cells transfected with EV (empty vector), WT- or EAAE-SpCas9-Flag and EMX1-sgRNAs for 72 h; Right: representative DNA agarose gel images of standard T7E1 assays derived from HEK293T cells transfected with indicated Cas9 and sgRNA performed 3-day post-transfection. Indel% was calculated and presented to indicate target gene editing efficiency. (J–L) Left: IB analysis of WCL derived from HEK293T (J), HBE (K) or BPH1 (L) cells transfected with EV (empty vector), WT- or EAAE-SpCas9-Flag and EMX1-sgRNAs for 72 h; Right: calculations of EMX-1 gene editing efficiency derived from DNA sanger sequencing of PCR products of targeted EMX-1 genomic regions from HEK293T cells transfected with indicated Cas9 and sgRNA performed 3-day post-transfection. n = 2 (biological duplicates). *P< 0.05 (one-way ANOVA test). (M) The scheme to test CRISPRki efficiency by introducing a new Sca-I site in the mouse Rosa26 locus. (N) IB analysis of WCL derived from MEF cells transfected with WT or EAAE-SpCas9-Flag constructs for 48 h. (O) A representative DNA agarose gel image of Sca-I digestion of PCR products using genomic DNA from cells from (N) to measure CRISPRki efficiency. (P) IB analysis of WCL derived from HEK293T cells transfected with EV (empty vector), WT- or AEGA-SaCas9-Flag and hDMD-sgRNAs for 72 h. (R) Calculations of hDMD gene editing efficiency derived from DNA sanger sequencing of PCR products of targeted hDMD genomic regions from HEK293T cells transfected with indicated Cas9 and sgRNA performed 3-day post-transfection. n = 2 (biological duplicates). *P< 0.05 (one-way ANOVA test). (S, T) Left: IB analysis of WCL derived from BPH1 cells transfected with EV (empty vector), WT- or AEGA-SaCas9-HA and indicated sgRNAs for 48 h; Right: calculations of indicated gene editing efficiency derived from DNA sanger sequencing of PCR products of targeted genomic regions from BPH1 cells transfected with indicated Cas9 and sgRNA performed 3-day post-transfection. n = 2 (biological duplicates). *P< 0.05 (one-way ANOVA test).

When expressed to a comparable protein level to WT-SpCas9, EAAE-SpCas9 displayed an enhanced AAVS1 gene editing efficiency at either the 2-day (Supplementary Figure S4B) or 3-day period post-transfection (Figure 4G, H). Similarly enhanced gene editing ability was also observed using EMX1-sgRNA in either E7T1 assays (Figure 4I) or DNA sanger sequencing coupled TIDE analyses (Figure 4J) that are commonly used to analyze indels generated by CRISPR. In addition to HEK293T cells, we also observed that compared to WT-SpCas9, EAAE-SpCas9 generated more indels guided by EMX1-sgRNA in HBE (human bronchial epithelial) (Figure 4K) or BPH1 (benign prostatic hyperplasia) cells (Figure 4L). Together these data support that EAAE-SpCas9 displays an enhanced CRISPRko efficiency than WT-SpCas9 in cells.

To examine effects of SpCas9 mutants on CRISPRki efficiency, we used a guide RNA to introduce a KpnI site into the human AAVS1 locus (Figure 4A). Notably, EAAE-SpCas9, when expressed to a similar level to WT-SpCas9, also displayed an increased ability in AAVS1 gene knockin efficiency (Supplementary Figure S4C) evidenced by KpnI digestion. To further reinforce this conclusion, we also designed unique primers targeting only KpnI inserted genomic DNA regions to measure the knockin efficacy by qPCR. This approach also indicated that EAAE-SpCas9 displayed an increased knockin efficiency compared with WT-SpCas9 (Supplementary Figure S4D, E). Moreover, depletion of endogenous Keap1 resulted in increased AAVS1 indel generation and knockin efficiencies in WT-, but not EAAE-SpCas9 expressing cells (Supplementary Figure S4F). To further reinforce this conclusion, we utilized sgRNAs targeting the mouse Rosa26 locus and a donor template (Figure 4M) to measure the knockin efficiency in MEFs (mouse embryonic fibroblasts). To this end, we found that when WT and EAAE-SpCas9 were expressed to a comparable protein level (Figure 4N), EAAE-SpCas9 exerted an increased ability to facilitate CRISPRki (Figure 4O).

For SaCas9, we identified an AEGA-SaCas9 mutant bypassing Keap1 recognition and degradation (Figure 3C, D). Thus, we further examined if evading the Keap1 negative regulation facilitates SaCas9-mediated gene editing. We found that AEGA-SaCas9 exerted an increased gene editing efficiency in HEK293T cells using sgRNAs targeting either DMD (Duchenne muscular dystrophy) (Figure 4P–R), FANCF (FA complementation group F) (Supplementary Figure S4G, H) or EMX1 (empty spiracles homeobox 1) gene (Supplementary Figure S4I, J). Considering in clinic CRISPR-mediated gene editing would be more applicable to primary cells, we further compared effects of SaCas9-AEGA with SaCas9-WT in BPH1 cells and observed that AEGA exerted a significantly increased indel generation ability using sgRNAs either targeting endogenous EMX-1 locus (Figure 4S) or the DMD related DMD locus (Figure 4T). Together, these data support the notion that SpCas9-EAAE or SaCas9-AEGA mutant evading Keap1 recognition displays enhanced gene editing ability in cells.

To further examine whether AEGA-SaCas9 displays enhanced gene editing ability in vivo, we utilized an established DMD mouse model (9). First, we observed an increased dystrophin exon deletion efficiency in C2C12 mouse myoblast cells using AEGA-SaCas9, compared with WT-SaCas9 (Supplementary Figure S5A). This prompted us to further evaluate the efficacy of either AAV-SaCas9-WT or AAV-SaCas9-AEGA to remove the mutated exon 23 from the dystrophin gene in live DMD mice. 8-weeks post-AAV injection, we harvested muscle and other tissues from mice to examine exon deletion efficiency (Supplementary Figure S5B). We found that although less AEGA-SaCas9 proteins were detected than WT-SaCas9 in distinct organs from these animals (Supplementary Figure S5C-E: 0.52-fold, 0.37-fold and 0.88 fold compared with WT-SaCas9 in Supplementary Figure S5C-E, respectively), a slightly increased dystrophin gene deletion efficiency was observed in tibialis anterior (Supplementary Figure S5C), as well as a comparable dystrophin gene deletion efficiency in liver (Supplementary Figure S5D) and heart (Supplementary Figure S5E). Cumulatively, these data indicate that although Cas9-mutants evading Keap1-mediated degradation exert enhanced gene editing ability in cells, its effects on in vivo gene editing effects remain to be further determined.

One possible concern for increased protein half-life of Cas9 variants by evading Keap1 recognition is the build-up of off-target effects. We relied on previously characterized off-target sites for sgEMX-1 (27) to test this possibility. By DNA sanger sequencing coupled TIDE analysis, we observed that although EAAE-SpCas9 improved on-target gene editing efficiency compared with WT-SpCas9 (Supplementary Figure S6A, B), it also increased the off-target frequency at 7 characterized off-target regions tested (Supplementary Figure S6C-I). eSpCas9 has been reported with improved on-target specificity (27). Next, we engineered an eSpCas9-EAAE mutant and found compared with SpCas9, eSpCas9 indeed reduced off-target effects on all 7 known off-target sites we tested (Supplementary Figure S6C-I). Moreover, compared with EAAE-SpCas9, EAAE-eSpCas9 significantly decreased 6 out of 7 off-target indels (Supplementary Figure S6C–I). Compared with WT-eSpCas9, EAAE-eSpCas9 didn’t generate more indels on 2 off-target sites (Supplementary Figure S6C–I). Together, these data suggest that cautions would need to be taken into consideration for off-target effects for SpCas9-EAAE mutant, while the eSpCas9-EAAE variant is a relatively ‘safer’ candidate not only evading Keap1 recognition with improved gene editing ability, but also with less off-target effects.

Engineered EAAE-dSpCas9-fusions exert increased CRISPRa or CRISPRi ability.

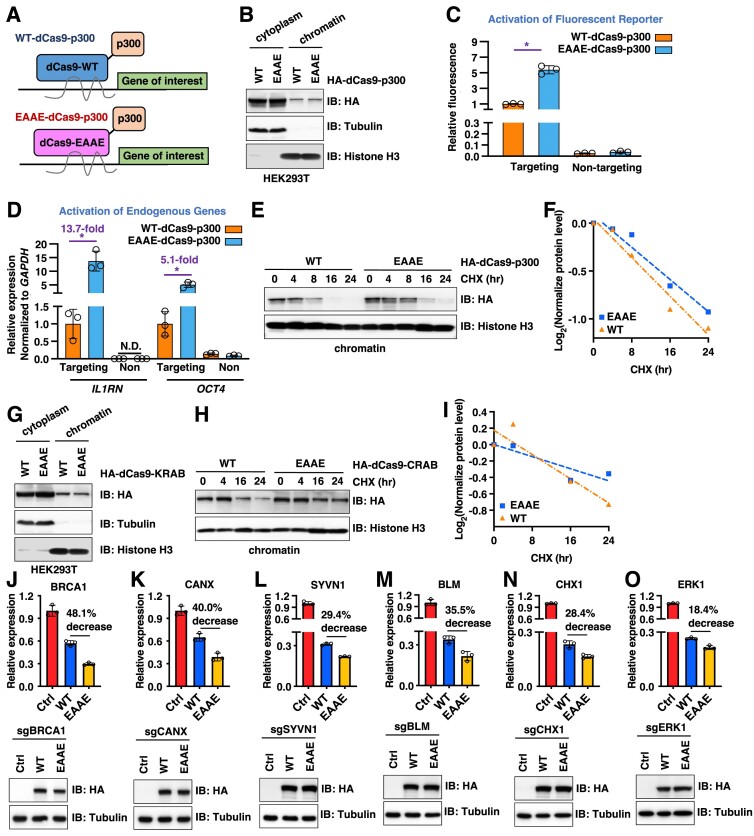

In addition to Cas9-mediated gene editing, catalytic-dead versions of Cas9 (dCas9) have been widely used in epigenetic regulation, taking advantage of the anchoring of dCas9 (and its fusion partners) by a specific sgRNA to a designated chromatin locus (56). Given that our identified Cas9 mutants display extended protein half-lives (Supplementary Figure S2J), we next examined if EAAE-dSpCas9-fusions similarly enhances dCas9-governed transcriptional modulation. To this end, we found that like SpCas9, dSpCas9 was also subjected to Keap1-mediated protein degradation control (Supplementary Figure S7A). We then created a series of dSpCas9 fusions with distinct well-defined epigenetic regulators, including dSpCas9-VPR (a tripartite fusion of 3 heterologous viral trans-activation domains), dSpCas9-p300 (E1A binding protein p300) and dCas9-SunTagx10 for transcription activation, as well as dSpCas9-KRAB (kruppel associated box) for transcription inactivation (57). All the fusions were designed to have the same dSpCas9 sequence and promoter. We also created a similar set with the ‘EAAE-dSpCas9’ counterpart mutation (Figure 5A). We found WT-dSpCas9-p300 was targeted by Keap1 for degradation (Supplementary Figure S7B). Protein expression of EAAE-dSpCas9-p300 was comparable to WT-dSpCas9-p300 in cells (Supplementary Figure S7C), regardless of transfection periods (Supplementary Figure S7D) and cellular locations (either cytoplasm or chromatin, Figure 5B). Importantly, compared with WT-dSpCas9-p300, EAAE-dSpCas9-p300 exerted a significantly increased ability to activate transcription of either an exogenous fluorescent reporter (58) (Figure 5C), or endogenous genes such as OCT4 (POU5F1, POU class5 homobox1) (5.1-fold) and IL1RN (interleukin 1 receptor antagonist) (13.7-fold) (Figure 5D). This was largely due to that EAAE-dSpCas9-p300 proteins remained on chromatin for a longer duration compared to dSpCas9-WT, evidenced by an extended EAAE-dSpCas9-p300 protein half-life on chromatin (Figure 5E, F). Notably, cytoplasmic EAAE-dSpCas9-p300 proteins also exerted an extended protein half-life (Supplementary Figure S7E). Similarly, even the EAAE-dSpCas9-VPR fusion and EAAE-dSpCas9-SunTag fusion showed less expression to their WT counterparts in cells (Supplementary Figure S7F), mutant versions displayed an enhanced ability to increase transcription of an exogenous fluorescent reporter (Supplementary Figure S7G, H). Together, these data suggest that EAAE-dSpCas9 fusions with epigenetic activators evading Keap1-mediated degradation display an increased CRISPRa ability in vitro.

Figure 5.

dCas9-EAAE-fusions exert enhanced epigenome regulation ability in cells. (A) A cartoon illustration of both dCas9-WT-p300 fusion and dCas9-EAAE-p300 fusion proteins in bringing the p300 transcription activator to a given site determined by sgRNA in regulating expression of genes of interests. (B) IB analyses of cytoplasm or chromatin fractions from HEK293T cells transfected with WT- or EAAE-dCas9-p300 constructs for 48 h. (C) Fluorescent reporter assays derived from HEK293T cells transfected with WT-dCas9-p300 or EAAE-dCas9-p300 constructs with a fluorescence reporter indicating that dSpCas9-EAAE-p300 fusion proteins displays an increase in activating targeted exogenous gene expression compared with dSpCas9-WT-p300. Fluorescent signals were detected by FACS analyses against GFP. n = 3 (biological triplicates). *P< 0.05 (one-way ANOVA test). (D) RT-PCR analyses of expression of indicated mRNA targets from HEK293T cells transfected with WT-dCas9-p300 or EAAE-dCas9-p300 with sgRNAs targeting either OCT4 or IL1RN, which indicates that dSpCas9-EAAE-p300 fusion proteins displays a significantly increased efficiency in activating targeted endogenous gene expression compared with dSpCas9-WT-p300. n = 3 (biological triplicates). (E) IB analysis of chromatin fractions of HEK293T cells transfected with indicated WT- or EAAE-HA-dCas9-p300 constructs for 48 h. Where indicated, 200 μg/ml CHX was added to culture and cells were harvested at indicated time periods. Quantifications of HA-dCas9-p300 protein half-life were presented in (F). (G) IB analyses cytoplasm and chromatin fractions from HEK293T cells transfected with either WT- or EAAE-dCas9-CRAB for 48 h. (H) IB analysis of chromatin fractions of HEK293T cells transfected with indicated WT- or EAAE-HA-dCas9-CRAB constructs for 48 h. Where indicated, 200 μg/ml CHX was added to culture and cells were harvested at indicated time periods. Quantifications of HA-dCas9-CRAB protein half-life were presented in (I). (J–O) Lower panels: IB analyses of WCL from HEK293T cells transfected with indicated dCas9-CRAB and sgRNAs. Upper panels: RT-PCR analyses of mRNAs from cells in lower panels expressing either WT- or EAAE-dCas9-CRAB for indicated target gene expression. Notably, U6 snRNA is used as an internal normalization control. n = 3 (biological triplicates). *P< 0.05 (one-way ANOVA test).

We next investigated if evading Keap1-mediated dSpCas9 degradation also increases CRISPRi efficiency. We engineered WT- or EAAE-dSpCas9-KRAB fusions with comparable protein expression levels both in cytoplasm and on chromatin (Figure 5G). Compared with WT-dSpCas9-KRAB, EAAE-dSpCas9-KRAB showed an extended protein half-life in cytoplasm (Supplementary Figure S7I) and more importantly, on chromatin (Figure 5H, I). As a result, EAAE-dSpCas9-KRAB exerted an enhanced ability to suppress expression of endogenous genes including BRCA1 (Figure 5J), CANX (calnexin) (Figure 5K), SYVN1 (synoviolin 1) (Figure 5L), BLM (BLM RecQ like helicase) (Figure 5M), CHX1 (IRE2, immediate early response 2) (Figure 5N) and ERK1 (mitogen activated protein kinase 3) (Figure 5O) using U6 or actin as a normalization control (Supplementary Figure S7J-L). These data suggest that EAAE-dSpCas9 fusions also enhance the CRISPRi ability in cells.

Cas9 is a Keap1 inhibitor

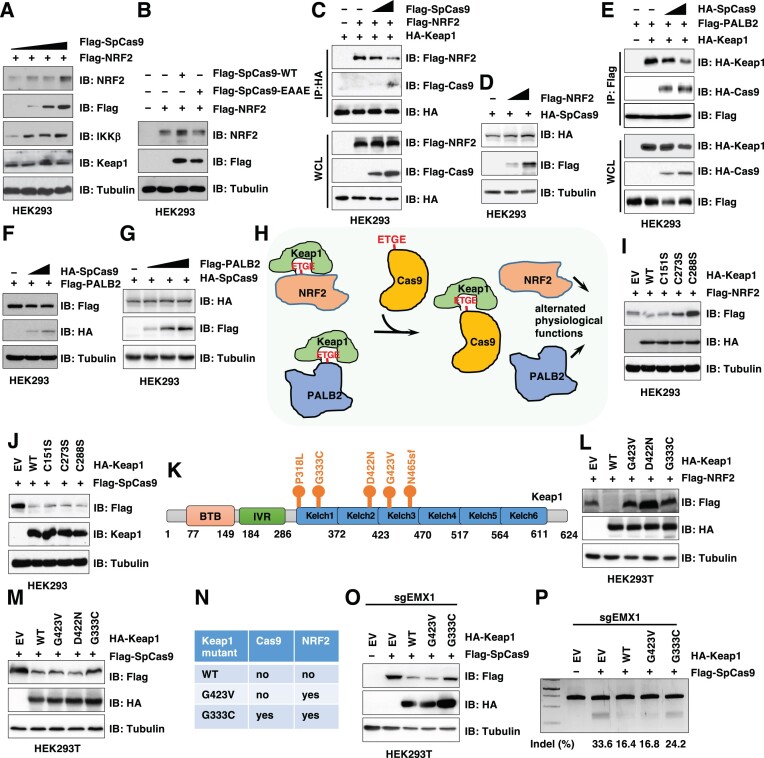

Given that Cas9 proteins are not naturally present in mammalian cells, we speculate that introducing bacterial Cas9 proteins into mammalian systems may trigger immune responses and/or perturb mammalian signaling. Indeed, anti-Cas9 antibodies or Cas9 immune-reactive T cells were detected in human serum (59–62) but not in the eye (63). Whether and how Cas9 specifically modulate intrinsic cellular programs remain unclear. We found that expression of SpCas9 led to stabilization of Keap1 substrates including NRF2 and IKKβ (64) (Figure 6A) in an ‘ETGE’ degron-dependent manner (Figure 6B). This was largely due to the SpCas9 proteins sequestering Keap1 from its endogenous substrates (such as NRF2) (Figure 6C). On the other hand, increasing NRF2 expression didn’t significantly affect SpCas9 protein levels (Figure 6D). In addition to Keap1 substrates, SpCas9 binding to Keap1 also blocked binding of other Keap1 binding partners that are not Keap1 substrates, including PALB2 (52) (Figure 6E). Expression of SpCas9 didn’t affect PALB2 protein stability (Figure 6F) and vice versa (Figure 6G). Together, these data suggest that SpCas9 may function as a Keap1 inhibitor, expression of which titrates Keap1 away from endogenous Keap1 substrates and Keap1 binding partners, leading to stabilization of Keap1 substrates and attenuated Keap1-mediated regulation of cellular processes. On the other hand, EAAE-SpCas9 does not inhibit Keap1 function due to its inability to interact with Keap1, thus may have minimal effects on Keap1 biology.

Figure 6.

SpCas9 stabilizes endogenous Keap1 substrates by competitively binding Keap1 to modulate its cellular functions. (A) IB analysis of WCL derived from HEK293 cells transfected with Flag-NRF2 and increasing doses of Flag-SpCas9 constructs for 48 h. (B) IB analysis of WCL derived from HEK293 cells transfected with Flag-NRF2 and indicated WT-Cas9 or EAAE-Cas9 constructs for 48 h. (C) IB analysis of WCL and HA-IPs derived from HEK293 cells transfected with HA-Keap1, Flag-NRF2 or Flag-SpCas9 constructs for 48 h. (D) IB analysis of WCL derived from HEK293 cells transfected with HA-SpCas9 with increasing doses of Flag-NRF2 constructs for 48 h. (E) IB analysis of WCL and Flag-IPs derived from HEK293 cells transfected with Flag-PALB2, HA-Keap1 and increasing doses of HA-SpCas9 constructs for 48 h. (F) IB analysis of WCL derived from HEK293 cells transfected with Flag-PALB2 and increasing doses of HA-SpCas9 constructs for 48 h. (G) IB analysis of WCL derived from HEK293 cells transfected with HA-SpCas9 and increasing doses of Flag-PALB2 constructs for 48 h. (H) A proposed model for how SpCas9 expression modulates cellular function. Specifically, SpCas9 binds and titrates Keap1 away from endogenous Keap1 substrates, leading to stabilization of Keap1 substrates including NRF2 and subsequently altered cellular signaling. (I) IB analysis of WCL derived from HEK293 cells transfected with Flag-NRF2 with indicated HA-Keap1 constructs for 48 h. (J) IB analysis of WCL derived from HEK293 cells transfected with Flag-SpCas9 with indicated HA-Keap1 constructs for 48 h. (K) A schematic illustration of cancer patient derived Kelch domain mutations in Keap1. (L) IB analysis of WCL from HEK293T cells transfected with Flag-NRF2 with indicated HA-Keap1 constructs. (M) IB analysis of WCL from HEK293T cells transfected with Flag-SpCas9 with indicated HA-Keap1 constructs. (N) A table summarizing various Keap1 mutants used in this study with impaired function in either degrading NRF2 or Cas9. (O) IB analysis of WCL from HEK293T cells transfected with Flag-SpCas9 with indicated HA-Keap1 constructs and EMX1-sgRNA for 72 h. (P) A representative DNA agarose gel image of the standard T7E1 assays using cells from (O).

Keap1 mutations are frequently observed in human cancers, especially lung cancer, where these cancerous Keap1 mutants are deficient in degrading oncogenic substrates including NRF2 (46). Next, we examined if cancer-associated Keap1 mutants are also deficient in degrading Cas9, thus CRISPR-mediated gene editing may exhibit higher activity in these Keap1-mutant tumors. To this end, we found that Keap1-C273S and C288S inactivation mutants (to mimic electrophiles-stimulated states) that are deficient in degrading NRF2 (65) (Figure 6I) were still capable of degrading SpCas9 (Figure 6J). Given that these two critical cysteines are modified in response to oxidative and electrophilic stresses to suppress Keap1-mediated degradation of NRF2 (65), these data suggest that Keap1 may utilize distinct mechanisms to target NRF2 and SpCas9 for degradation, respectively. Thus, we aimed to identify possible Keap1 cancer-associated mutations that are deficient in degrading Cas9 to further understand how possible environmental cues may modulate Keap1-mediated Cas9 protein stability control. Querying a panel of commonly observed Keap1-Kelch domain cancerous mutations including G423V, D422N and G333C (Figure 6K), we found that although all these Keap1 mutants were deficient in degrading NRF2 (Figure 6L), only the G333C-Keap1 mutant was unable to degrade SpCas9 in cells (Figure 6M, N). As a result, we found that ectopic expression of WT- or G423V-Keap1, but not G333C-Keap1 (Figure 6O), significantly impaired SpCas9-guided AAVS1 gene editing (Figure 6P). These data suggest that not all Keap1 mutant-expressing cells with NRF2 accumulation would necessarily result in enhanced CRISPR efficiency, and that effects of Keap1 mutants on NRF2 signaling and Cas9/dCas9 mediated gene modulation can be separated. Thus, Keap1 expression, but not Keap1 somatic mutation nor activity, may be a more faithful marker to predict gene /epigenome editing efficacy by CRISPR-Cas9/dCas9.

Discussion

In this study, we find that an endogenous mammalian E3 ligase Keap1 earmarks Cas9s and dCas9s for ubiquitination and degradation to restrain CRISPR-mediated gene editing efficiency. Engineered Cas9s and dCas9s with mutated Keap1 degrons that evade Keap1-mediated suppression display improved Cas9 and dCas9 protein stability, as well as gene editing and epigenome regulation efficiency, respectively, in cells. However, the minimal effects of AEGA-SaCas9 in improving DMD gene editing efficacy compared with WT-SaCas9 in our DMD mouse model may be due to lower mutated Cas9 expression levels, or that this mutant exerts additional functions in vivo. Thus, if Cas9 variants evading Keap1 recognition and regulation exert enhanced gene editing ability in vivo requires further in-depth investigations using additional animal models. Nonetheless, evading Keap1-mediated protein degradation leads to sustained dCas9 deposition on chromatin, leading to enhanced dCas9-mediated transcriptional regulation. These results provide a rationale to utilize engineered dCas9 variants in further improving CRISPRi and CRISPRa capability. Notably, whether dCas9 variants bypassing Keap1 recognition improves in vivo CRISPRi or CRISPRa efficacy warrants further investigations.

In addition to bacterial Cas9 proteins, Keap1 also targets the eukaryotic enzyme Fanzor for degradation. These data suggest that mammalian Keap1 may serve as a regulator for these bacterial/eukaryotic endonucleases bearing potential Keap1 degrons as a general host defense mechanism. Further in-depth investigations are warranted to examine Keap1 recognition of additional endonucleases.

On the other hand, Cas9 also functions as a Keap1 suppressor in cells by competing with bona fide Keap1 substrates or binding proteins to inactivate Keap1 function. Inducible or constitutive Cas9 expression in various mouse tissues didn’t lead to morphological and breeding abnormalities (66); however, two reports demonstrate that Cas9 may induce a cellular toxic effect by triggering p53-dependent DNA damage response, which indirectly enriches p53-mutated cells (67,68). Considering the tight connection of p53 mutations with cancer, these studies may connect Cas9 activity with tumorigenesis. Notably, the Keap1/NRF2 signaling exerts context-dependent roles in tumorigenesis (69). For example, NRF2 is an oncogene in lung cancer (70) and breast cancer (71), while it functions as a tumor suppressor by exerting chemo-preventive activities or in established Nrf2 knockout murine models in skin (72), stomach (73), colon (74) and bladder (75) cancer. Given that SpCas9 perturbs the Keap1/NRF2 signaling to cause NRF2 accumulation, how Cas9 affects cell behaviors may be largely determined by the pathophysiological settings. Elevated NRF2 protein levels have also been reported to contribute to resistance to anti-cancer drugs and cause metabolic reprogramming (76), suggesting the application of the CRISPR-Cas9 system in non-biased screens for drug resistant genes or metabolic vulnerability would be undertaken cautiously with considerations from the impact of Cas9 on NRF2 activity. To this end, Cas9 is not the only protein known to affect the Keap1/NRF2 signaling. A handful of mammalian proteins have been shown to compete with NRF2 to bind Keap1, leading to NRF2 accumulation, including HBXIP (71), CDK20 (77), P62/sqstm1 (78) and p21 (79). Thus, it is plausible that in addition to Keap1/NRF2, expression of the bacterial Cas9 proteins in mammalian cells may also affect other mammalian signaling networks, through which Cas9 modulates cellular functions and behaviors. This knowledge will provide a further guide to improve the safe applications of CRISPR-Cas9 technique in gene therapies in humans.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Liu, Major, Hathaway and Gersbach lab members for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful discussions. The graphic abstract is generated using Biorender.

Contributor Information

Jianfeng Chen, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA; Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, School of Medicine, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

Siyuan Su, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA; Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, School of Medicine, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

Adrian Pickar-Oliver, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Duke University, Durham, NC 27710, USA; Center for Advanced Genomic Technologies, Duke University, Durham, NC 27710, USA.

Anna M Chiarella, Division of Chemical Biology and Medicinal Chemistry, Center for Integrative Chemical Biology and Drug Discovery, Eshelman School of Pharmacy, The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA; Curriculum in Genetics and Molecular Biology, The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

Quentin Hahn, Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, School of Medicine, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

Dennis Goldfarb, Department of Cell Biology and Physiology, Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63110, USA; Institute for Informatics, Data Science & Biostatistics, Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63110, USA.

Erica W Cloer, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA; Department of Cell Biology and Physiology, School of Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

George W Small, Center for Pharmacogenomics and Individualized Therapy, Eshelman School of Pharmacy, The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

Smaran Sivashankar, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

Dale A Ramsden, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA; Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, School of Medicine, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

Michael B Major, Department of Cell Biology and Physiology, Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63110, USA.

Nathaniel A Hathaway, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA; Division of Chemical Biology and Medicinal Chemistry, Center for Integrative Chemical Biology and Drug Discovery, Eshelman School of Pharmacy, The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA; Curriculum in Genetics and Molecular Biology, The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

Charles A Gersbach, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Duke University, Durham, NC 27710, USA; Center for Advanced Genomic Technologies, Duke University, Durham, NC 27710, USA.

Pengda Liu, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA; Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, School of Medicine, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD050935.

Supplementary data

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

Funding

NIH [R21CA270967 P.L.]; Andrew McDonough B + Foundation Childhood Cancer Research Grant (to P.L.); UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center Development Award (to P.L. and B. M.); UNC University Cancer Research Fund (to P.L.) [R35GM148365 to N.H.]; NIH [R01AR069085, U01AI146356, U01EB028901 to C.A.G.]; A.P.-O. was supported by a Pfizer-NCBiotech Distinguished Postdoctoral Fellowship. Funding for open access charge: NIH [R21CA270967].

Conflict of interest statement. C.A.G. is a co-founder and advisor to Tune Therapeutics, an advisor to Sarepta Therapeutics, and a co-founder of Locus Biosciences. C.A.G. and A.P-O. are inventors on patents or patent applications related to CRISPR technologies. J.C., S.S., B.M. and P.L. are inventors on patent applications related to CRISPR technologies.

References

- 1. Mali P., Yang L., Esvelt K.M., Aach J., Guell M., DiCarlo J.E., Norville J.E., Church G.M.. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013; 339:823–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cong L., Ran F.A., Cox D., Lin S., Barretto R., Habib N., Hsu P.D., Wu X., Jiang W., Marraffini L.A.et al.. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013; 339:819–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen S., Sanjana N.E., Zheng K., Shalem O., Lee K., Shi X., Scott D.A., Song J., Pan J.Q., Weissleder R.et al.. Genome-wide CRISPR screen in a mouse model of tumor growth and metastasis. Cell. 2015; 160:1246–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Korkmaz G., Lopes R., Ugalde A.P., Nevedomskaya E., Han R., Myacheva K., Zwart W., Elkon R., Agami R.. Functional genetic screens for enhancer elements in the human genome using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016; 34:192–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huang A., Garraway L.A., Ashworth A., Weber B.. Synthetic lethality as an engine for cancer drug target discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020; 19:23–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kurata M., Yamamoto K., Moriarity B.S., Kitagawa M., Largaespada D.A.. CRISPR/Cas9 library screening for drug target discovery. J. Hum. Genet. 2018; 63:179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Xiao-Jie L., Hui-Ying X., Zun-Ping K., Jin-Lian C., Li-Juan J.. CRISPR-Cas9: a new and promising player in gene therapy. J. Med. Genet. 2015; 52:289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang G., McCain M.L., Yang L., He A., Pasqualini F.S., Agarwal A., Yuan H., Jiang D., Zhang D., Zangi L.et al.. Modeling the mitochondrial cardiomyopathy of Barth syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cell and heart-on-chip technologies. Nat. Med. 2014; 20:616–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nelson C.E., Hakim C.H., Ousterout D.G., Thakore P.I., Moreb E.A., Castellanos Rivera R.M., Madhavan S., Pan X., Ran F.A., Yan W.X.et al.. In vivo genome editing improves muscle function in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Science. 2016; 351:403–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tabebordbar M., Zhu K., Cheng J.K.W., Chew W.L., Widrick J.J., Yan W.X., Maesner C., Wu E.Y., Xiao R., Ran F.A.et al.. In vivo gene editing in dystrophic mouse muscle and muscle stem cells. Science. 2016; 351:407–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim K., Park S.W., Kim J.H., Lee S.H., Kim D., Koo T., Kim K.E., Kim J.H., Kim J.S.. Genome surgery using Cas9 ribonucleoproteins for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Genome Res. 2017; 27:419–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gao X., Tao Y., Lamas V., Huang M., Yeh W.H., Pan B., Hu Y.J., Hu J.H., Thompson D.B., Shu Y.et al.. Treatment of autosomal dominant hearing loss by in vivo delivery of genome editing agents. Nature. 2018; 553:217–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen Z.H., Yu Y.P., Zuo Z.H., Nelson J.B., Michalopoulos G.K., Monga S., Liu S., Tseng G., Luo J.H.. Targeting genomic rearrangements in tumor cells through Cas9-mediated insertion of a suicide gene. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017; 35:543–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaminski R., Bella R., Yin C., Otte J., Ferrante P., Gendelman H.E., Li H., Booze R., Gordon J., Hu W.et al.. Excision of HIV-1 DNA by gene editing: a proof-of-concept in vivo study. Gene Ther. 2016; 23:696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gillmore J.D., Gane E., Taubel J., Kao J., Fontana M., Maitland M.L., Seitzer J., O’Connell D., Walsh K.R., Wood K.et al.. CRISPR-Cas9 In Vivo gene editing for transthyretin amyloidosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021; 385:493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee R.G., Mazzola A.M., Braun M.C., Platt C., Vafai S.B., Kathiresan S., Rohde E., Bellinger A.M., Khera A.V.. Efficacy and safety of an investigational single-course CRISPR base-editing therapy targeting PCSK9 in nonhuman primate and mouse models. Circulation. 2023; 147:242–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yin H., Xue W., Chen S., Bogorad R.L., Benedetti E., Grompe M., Koteliansky V., Sharp P.A., Jacks T., Anderson D.G.. Genome editing with Cas9 in adult mice corrects a disease mutation and phenotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014; 32:551–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Long C., Amoasii L., Mireault A.A., McAnally J.R., Li H., Sanchez-Ortiz E., Bhattacharyya S., Shelton J.M., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E.N.. Postnatal genome editing partially restores dystrophin expression in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy. Science. 2016; 351:400–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tabebordbar M., Zhu K., Cheng J.K., Chew W.L., Widrick J.J., Yan W.X., Maesner C., Wu E.Y., Xiao R., Ran F.A.et al.. In vivo gene editing in dystrophic mouse muscle and muscle stem cells. Science. 2016; 351:407–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Amoasii L., Hildyard J.C.W., Li H., Sanchez-Ortiz E., Mireault A., Caballero D., Harron R., Stathopoulou T.R., Massey C., Shelton J.M.et al.. Gene editing restores dystrophin expression in a canine model of duchenne muscular dystrophy. Science. 2018; 362:86–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kosicki M., Tomberg K., Bradley A.. Repair of double-strand breaks induced by CRISPR-Cas9 leads to large deletions and complex rearrangements. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018; 36:765–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kleinstiver B.P., Prew M.S., Tsai S.Q., Topkar V.V., Nguyen N.T., Zheng Z., Gonzales A.P., Li Z., Peterson R.T., Yeh J.R.et al.. Engineered CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with altered PAM specificities. Nature. 2015; 523:481–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zetsche B., Gootenberg J.S., Abudayyeh O.O., Slaymaker I.M., Makarova K.S., Essletzbichler P., Volz S.E., Joung J., van der Oost J., Regev A.et al.. Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell. 2015; 163:759–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Burstein D., Harrington L.B., Strutt S.C., Probst A.J., Anantharaman K., Thomas B.C., Doudna J.A., Banfield J.F.. New CRISPR-Cas systems from uncultivated microbes. Nature. 2017; 542:237–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu J.J., Orlova N., Oakes B.L., Ma E., Spinner H.B., Baney K.L.M., Chuck J., Tan D., Knott G.J., Harrington L.B.et al.. CasX enzymes comprise a distinct family of RNA-guided genome editors. Nature. 2019; 566:218–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saito M., Xu P., Faure G., Maguire S., Kannan S., Altae-Tran H., Vo S., Desimone A., Macrae R.K., Zhang F.. Fanzor is a eukaryotic programmable RNA-guided endonuclease. Nature. 2023; 620:660–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Slaymaker I.M., Gao L., Zetsche B., Scott D.A., Yan W.X., Zhang F.. Rationally engineered Cas9 nucleases with improved specificity. Science. 2016; 351:84–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kleinstiver B.P., Pattanayak V., Prew M.S., Tsai S.Q., Nguyen N.T., Zheng Z., Joung J.K.. High-fidelity CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects. Nature. 2016; 529:490–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Casini A., Olivieri M., Petris G., Montagna C., Reginato G., Maule G., Lorenzin F., Prandi D., Romanel A., Demichelis F.et al.. A highly specific SpCas9 variant is identified by in vivo screening in yeast. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018; 36:265–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gaudelli N.M., Komor A.C., Rees H.A., Packer M.S., Badran A.H., Bryson D.I., Liu D.R.. Programmable base editing of A*T to G*C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature. 2017; 551:464–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dominguez A.A., Lim W.A., Qi L.S.. Beyond editing: repurposing CRISPR-Cas9 for precision genome regulation and interrogation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016; 17:5–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nishida K., Arazoe T., Yachie N., Banno S., Kakimoto M., Tabata M., Mochizuki M., Miyabe A., Araki M., Hara K.Y.et al.. Targeted nucleotide editing using hybrid prokaryotic and vertebrate adaptive immune systems. Science. 2016; 353:aaf8279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pawluk A., Amrani N., Zhang Y., Garcia B., Hidalgo-Reyes Y., Lee J., Edraki A., Shah M., Sontheimer E.J., Maxwell K.L.et al.. Naturally occurring off-switches for CRISPR-Cas9. Cell. 2016; 167:1829–1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Khajanchi N., Saha K.. Controlling CRISPR with small molecule regulation for somatic cell genome editing. Mol. Ther. 2022; 30:17–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chu V.T., Weber T., Wefers B., Wurst W., Sander S., Rajewsky K., Kuhn R.. Increasing the efficiency of homology-directed repair for CRISPR-Cas9-induced precise gene editing in mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015; 33:543–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Robert F., Barbeau M., Ethier S., Dostie J., Pelletier J.. Pharmacological inhibition of DNA-PK stimulates Cas9-mediated genome editing. Genome Med. 2015; 7:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yu C., Liu Y., Ma T., Liu K., Xu S., Zhang Y., Liu H., La Russa M., Xie M., Ding S.et al.. Small molecules enhance CRISPR genome editing in pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2015; 16:142–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xie K., Minkenberg B., Yang Y.. Boosting CRISPR/Cas9 multiplex editing capability with the endogenous tRNA-processing system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015; 112:3570–3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fulcher M.L., Gabriel S.E., Olsen J.C., Tatreau J.R., Gentzsch M., Livanos E., Saavedra M.T., Salmon P., Randell S.H.. Novel human bronchial epithelial cell lines for cystic fibrosis research. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2009; 296:L82–L91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liu P., Begley M., Michowski W., Inuzuka H., Ginzberg M., Gao D., Tsou P., Gan W., Papa A., Kim B.M.et al.. Cell-cycle-regulated activation of akt kinase by phosphorylation at its carboxyl terminus. Nature. 2014; 508:541–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu P., Gan W., Chin Y.R., Ogura K., Guo J., Zhang J., Wang B., Blenis J., Cantley L.C., Toker A.et al.. PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-dependent activation of the mTORC2 kinase complex. Cancer Discov. 2015; 5:1194–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liu P., Gan W., Guo C., Xie A., Gao D., Guo J., Zhang J., Willis N., Su A., Asara J.M.et al.. Akt-mediated phosphorylation of XLF impairs non-homologous end-joining DNA repair. Mol. Cell. 2015; 57:648–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Guo J., Chakraborty A.A., Liu P., Gan W., Zheng X., Inuzuka H., Wang B., Zhang J., Zhang L., Yuan M.et al.. pVHL suppresses kinase activity of Akt in a proline-hydroxylation-dependent manner. Science. 2016; 353:929–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thakore P.I., Kwon J.B., Nelson C.E., Rouse D.C., Gemberling M.P., Oliver M.L., Gersbach C.A.. RNA-guided transcriptional silencing in vivo with S. aureus CRISPR-Cas9 repressors. Nat. Commun. 2018; 9:1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chiarella A.M., Butler K.V., Gryder B.E., Lu D., Wang T.A., Yu X., Pomella S., Khan J., Jin J., Hathaway N.A.. Dose-dependent activation of gene expression is achieved using CRISPR and small molecules that recruit endogenous chromatin machinery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020; 38:50–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hast B.E., Cloer E.W., Goldfarb D., Li H., Siesser P.F., Yan F., Walter V., Zheng N., Hayes D.N., Major M.B.. Cancer-derived mutations in KEAP1 impair NRF2 degradation but not ubiquitination. Cancer Res. 2014; 74:808–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhu Z., Zhou X., Du H., Cloer E.W., Zhang J., Mei L., Wang Y., Tan X., Hepperla A.J., Simon J.M.et al.. STING suppresses mitochondrial VDAC2 to govern RCC growth independent of innate immunity. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2023; 10:e2203718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Perez-Riverol Y., Bai J., Bandla C., Garcia-Seisdedos D., Hewapathirana S., Kamatchinathan S., Kundu D.J., Prakash A., Frericks-Zipper A., Eisenacher M.et al.. The PRIDE database resources in 2022: a hub for mass spectrometry-based proteomics evidences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022; 50:D543–D552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ergunay T., Ayhan O., Celen A.B., Georgiadou P., Pekbilir E., Abaci Y.T., Yesildag D., Rettel M., Sobhiafshar U., Ogmen A.et al.. Sumoylation of Cas9 at lysine 848 regulates protein stability and DNA binding. Life Sci. Alliance. 2022; 5:e202101078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Baird L., Yamamoto M.. The molecular mechanisms regulating the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2020; 40:e00099-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kansanen E., Kuosmanen S.M., Leinonen H., Levonen A.L.. The Keap1-Nrf2 pathway: mechanisms of activation and dysregulation in cancer. Redox. Biol. 2013; 1:45–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Orthwein A., Noordermeer S.M., Wilson M.D., Landry S., Enchev R.I., Sherker A., Munro M., Pinder J., Salsman J., Dellaire G.et al.. A mechanism for the suppression of homologous recombination in G1 cells. Nature. 2015; 528:422–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Li X., Zhang D., Hannink M., Beamer L.J.. Crystal structure of the Kelch domain of human Keap1. J. Biol. Chem. 2004; 279:54750–54758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ran F.A., Hsu P.D., Wright J., Agarwala V., Scott D.A., Zhang F.. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Protoc. 2013; 8:2281–2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Akutsu M., Dikic I., Bremm A.. Ubiquitin chain diversity at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2016; 129:875–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kampmann M. CRISPRi and CRISPRa screens in mammalian cells for precision biology and medicine. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018; 13:406–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chavez A., Tuttle M., Pruitt B.W., Ewen-Campen B., Chari R., Ter-Ovanesyan D., Haque S.J., Cecchi R.J., Kowal E.J.K., Buchthal J.et al.. Comparison of Cas9 activators in multiple species. Nat. Methods. 2016; 13:563–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Butler K.V., Chiarella A.M., Jin J., Hathaway N.A.. Targeted gene repression using novel bifunctional molecules to harness endogenous histone deacetylation activity. ACS Synth. Biol. 2018; 7:38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Simhadri V.L., McGill J., McMahon S., Wang J., Jiang H., Sauna Z.E.. Prevalence of pre-existing antibodies to CRISPR-associated nuclease Cas9 in the USA population. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2018; 10:105–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Charlesworth C.T., Deshpande P.S., Dever D.P., Camarena J., Lemgart V.T., Cromer M.K., Vakulskas C.A., Collingwood M.A., Zhang L., Bode N.M.et al.. Identification of preexisting adaptive immunity to Cas9 proteins in humans. Nat. Med. 2019; 25:249–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ferdosi S.R., Ewaisha R., Moghadam F., Krishna S., Park J.G., Ebrahimkhani M.R., Kiani S., Anderson K.S.. Multifunctional CRISPR-Cas9 with engineered immunosilenced human T cell epitopes. Nat. Commun. 2019; 10:1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]