Abstract

Marked alterations in the normal female hormonal milieu in the perimenopausal period significantly affect women’s health, leading to decreased well-being, psychological distress, and impaired quality of life. Common menopausal symptoms include hot flashes, sleep and mood changes, fatigue, weight gain, and urogenital disturbances. Clinicians often neglect mood swings and disrupted sleep, although those can significantly limit the productivity of women and impair their cognitive function and mental health. Evidence-based management should include a personalized, holistic approach to alleviate symptoms and careful consideration of the risks vs benefits of hormone replacement therapy (HRT), with due consideration of personal preferences. A research paper in the recent issue of the World Journal of Psychiatry by Liu et al investigated the role of HRT in altering mood changes and impaired sleep quality in menopausal women, which helps us to understand the benefits of this treatment approach.

Keywords: Menopausal symptoms, Mood changes, Sleep quality, Hormone replacement therapy, Quality of life

Core Tip: A structured and scientifically tailored approach is needed to provide safe and effective relief from menopausal symptoms, retrieve previous quality of life, and avoid complications in menopausal women. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is an important therapeutic option not only to alleviate menopausal symptoms but also to improve general, musculoskeletal, and emotional health. Liu et al investigated the role of HRT in altering the mood changes and sleep hygiene of menopausal women in a research paper in the recent issue of the World Journal of Psychiatry, the theme of this editorial.

INTRODUCTION

Menopause is a physiological state most women attain in their middle age, with significant changes in their hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis function and the neurohormonal milieu. These biological changes are associated with a variety of clinical problems in females, including physical ill-health and alterations in emotional health. The perimenopausal state is found to be associated with significantly higher risks for mood changes and symptomatic depression, resulting in impaired physical and emotional quality of life (QoL), as reported by multiple studies[1-3].

The perimenopausal state can also grossly alter the normal sleep-wake cycles in a high proportion of females, further reducing their QoL[2,4,5]. This can be from the symptoms associated with pulsatile hormonal surges in the perimenopausal period causing hot flashes (HFs) during sleep or neuropsychological alterations in brain function. It is important to understand the pathophysiological changes associated with menopause, its clinical picture, and the evaluation algorithm to optimize therapeutic interventions, the theme of this article.

Pathobiology of perimenopausal mood changes

Estradiol receptors are broadly distributed in the brain and affect brain functions such as memory, neuroprotection, and neurogenesis through regulation of metabolism and cerebral blood flow, impact on nerve growth factors and dendritic cells, and modulation in neurotransmitter synthesis and turnover[6]. Marked reduction in estrogen production occurs at menopause as a normal physiological response in females. A decline in estrogen secretion, together with other hormonal changes and fluctuations of neurosteroids during the perimenopausal period, is believed to cause dysregulation of the gamma amino butyric acid (GABA) balance between GABA-A and GABA-B receptors in the brain, which further leads to the development of mood swings[7,8].

Prospective longitudinal studies such as study of women across the nation (SWAN)[9,10] clearly demonstrated that mood changes, distinguished by depressive symptoms and anxiety, are associated with late perimenopause and menopause. Classical menopausal symptoms complicate, co-occur, or overlap with the presentation of psychological disturbances[10]. Recently published meta-analyses showed a higher prevalence of depression among perimenopausal [47.3%; 95% confidence interval (CI): 40.89-53.76] compared to premenopausal women (36.27%; 95%CI: 30.14-42.63)[11], which expose perimenopausal women in a significantly increased risk for being diagnosed with depression[1,12].

A meta-analysis of 14 randomized clinical trials (RCT) conducted by Zhang et al[13] showed that estrogen administration in perimenopausal women with depression provides benefits, either alone or in combination with progesterone or antidepressants, primarily by reducing fluctuations in estrogen levels and providing stable hormone level. This finding is consistent with the conclusion from Lozza-Fiacco et al[14], emphasizing the predictive role of estradiol variability on perimenopausal anxiety and anhedonia, particularly within the context of stressful life events.

Pathobiology of menopausal sleep disturbances

Sleep complaints are often encountered in the perimenopausal period and comprise issues primarily related to the duration and quality of sleep. According to studies, 40%-69% of women across the menopause transition report sleep disturbances, particularly nocturnal awakenings and increased awake time after sleep onset[9,15].

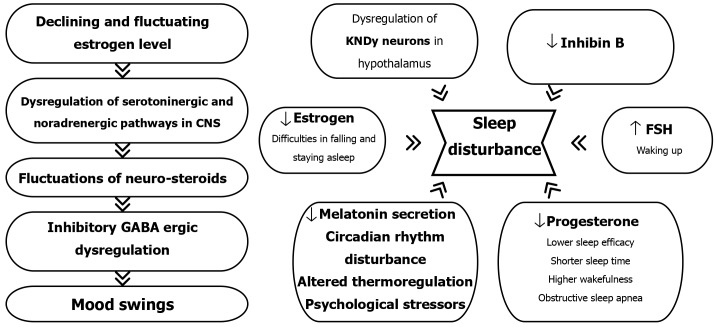

According to their role in sleep, changes in hormone levels via the hypothalamic axis could interfere with the normal sleep cycle. Increases in serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) are associated with greater odds of waking up several times, decreasing estrogen levels with difficulties staying and falling asleep[16]. At the same time, low progesterone is responsible for lower sleep efficacy, shorter sleep time, and higher wakefulness after sleep onset[15].

The neurobiology of menopausal disturbances associated with sleep is complex and includes decreased melatonin secretion, disturbance in circadian mechanisms, altered thermoregulation, and psychological stressors[15]. Additionally, evidence during the last decade suggests the key role of estrogen-sensitive kisspeptin-neurokinin B- dynorphin neurons in the hypothalamus in controlling pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone release and the pathways regulating the body temperature and other physiological processes[17].

Furthermore, since sleep is crucial for memory consolidation[18], a decline in sleep quality is probably associated with cognitive changes and reduced alertness often noticed in the perimenopausal period.

The relationship between previously mentioned mood changes, depression in particular, and sleep disturbances is bidirectional. Depressive symptoms emphasize sleep difficulties in menopausal women, and insomnia contributes to mood fluctuations and influences social aspects of life.

Figure 1 shows the neurohormonal alterations leading to perimenopausal changes in mood and sleep hygiene.

Figure 1.

Shows the neurohormonal alterations leading to perimenopausal changes in mood and sleep hygiene. GABA: Gamma amino butyric acid; KNDy: Kisspeptin-neurokinin B- dynorphin; FSH: Follicle-stimulating hormone.

Clinical presentation

The hallmark symptoms of the perimenopausal period are HFs and night sweats, affecting up to 80% of women[9]. Vasomotor symptoms (VMS) usually start before the final menstrual period (FMP) and progress in intensity and frequency during the first few years of menopause. Still, they can last for almost a decade[19], influencing women’s daily routines, social activities, and QoL. HFs usually last up to several minutes and include a rapid rise in body temperature with accompanying vasodilation. The pathophysiological basis of HFs is the physiologic narrowing of the hypothalamic thermoregulatory system that regulates core body temperature in response to a sudden reduction of estrogen levels[7]. Despite being usually perceived as a benign condition, frequent and prolonged VMS are associated with an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD)[20,21]. Since a data analysis from SWAN clearly demonstrated that sleep disruption strongly correlates with VMS[9], impaired sleep could be an easily assessed warning sign for future medical problems in menopausal women.

Genitourinary symptoms of menopause usually manifest 4-5 years after FMP with vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, irritation in the vulvovaginal region, urinary incontinence, and increased risk for urinary tract infections. Long-term consequences of estrogen deprivation are skin aging, osteoporosis, and sarcopenia. However, newer data confront the traditional correlation between low estrogen levels and diminished bone mineral density, putting a light on the role of FSH in postmenopausal bone health[22].

As previously mentioned, cognitive changes, mood fluctuations, low libido, and weight gain with redistribution of adipose tissue are also commonly found in aging women. Those symptoms and signs are often prominent, but despite their significant impact on mental and metabolic health and QoL, they frequently remain unrecognized, underrated, and, consequently, undertreated.

Diagnostic algorithm

The updated stages of reproductive aging workshop (STRAW + 10) report provide standardized criteria based on menstrual bleeding patterns and a comprehensive basis for assessing the transition from the reproductive to the postmenopausal period[23]. The menopausal transition extends over the late reproductive stage (-3), the early menopausal transition (-2), the late menopausal transition (-1), the final menopausal period [FMP] (stage 0) up to the early postmenopause (+1)[23].

FMP is preceded by a period of irregular and prolonged menstrual cycles, often marked as perimenopause. Gradual changes in serum hormonal levels reflect a decreasing estrogen production, including elevation of FSH and luteinizing hormone and decreased inhibin and anti-Müllerian hormone until they stabilize approximately 24 months after the FMP. The permanent cessation of menstrual periods, 12 months after FMP, is marked as menopause, and it occurs at a median age of 51 years[19].

Therapeutic interventions

Evidence-based approaches for menopausal symptoms include the use of hormonal replacement therapy (HRT), nonhormonal medications, and nonpharmacological treatment such as lifestyle interventions, cognitive behavioral therapy, or self-care programs[21,24]. The optimal choice of treatment is a complex decision. It requires an individualized approach, consideration of the degree of symptoms influencing everyday life and impairment of QoL, but also a risk stratification regarding CVD and estrogen-sensitive cancers (breast and endometrial).

A large debate in both the scientific and lay public has been raised concerning the appropriateness of the HRT during the past two decades despite the significant impact of menopausal symptoms on women’s daily lives[25]. HRT aims to target VMS, cognitive and mood changes, and genitourinary disturbances and to preserve BMD. It includes tailored treatment according to age and risk factors and with the lowest effective dose to control symptoms and prevent long-term consequences of hypoestrogenemia.

Estrogen is used as monotherapy or with the addition of progesterone, preferably micronized, in women with a uterus (sequential or continuous combined regimen). The route of estrogen administration is determined according to the risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE), so the peroral, transdermal, and topical preparations are available for prescription, keeping in mind the association between transdermal route and the lower risk of VTE.

Considering the “timing hypothesis’’ based on changes in estrogen receptor signaling during the time, HRT is most advantageous for menopausal women below the age of 60 and with less than 10 years spent in menopause without contraindications and with acceptable risks for breast cancer and CVD[25,26]. Data from a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Kronos Early Estrogen prevention study go along with the favorable outcomes with HRT when applied soon after FMP[27].

Absolute contraindications for HRT are estrogen-sensitive cancer (breast or endometrium), endometrial hyperplasia, severe active disease of the liver, stroke, dementia, coronary disease, high risk for thromboembolic condition, porphyria cutanea tarda and hypertriglyceridemia[19,25]. According to that, annual breast and gynecological reassessment is mandatory.

The duration of therapy is still debated; it was recommended within 10 years from the onset of menopause[28], but some authors nowadays suggest continuing HRT if it is a patient choice, as long as the benefits outweigh the risks[7,19,25,26].

When the appropriate dose is given on time to a low-risk patient, and the route of administration is carefully chosen, HRT is considered safe and effective, and the detected number of neoplasia is not significantly different from that of a placebo.[27,29] Prior et al[30] evaluated the effects of oral micronized progesterone in treating perimenopausal VMS and sleep disturbances and detected a significant improvement in symptoms after four months of the RCT period.

In a recent issue of the World Journal of Psychiatry, Liu et al[31] investigated the role of HRT in altering mood changes and impaired sleep quality in menopausal women.

After administering three courses (28 days each) of combined estrogen-progesterone therapy (estradiol valerate 1 mg plus hydroxyprogesterone acetate tablets 8 mg for 14 days per course), they found that the overall treatment effectiveness rate was higher in the treated observation group compared to the placebo (control) group (96.05% vs 86.84%, P = 0.042).

Improvement in menopausal symptoms assessed with modified Kupperman menopausal index score was detected in the treatment group in all 13 measured categories (P < 0.05), particularly regarding insomnia (P = 0.01), vertigo (P = 0.006) and sexuality (P = 0.008). The emotional state of treated menopausal women was also improved; the positive and negative affect scale score after three courses of therapy was significantly different compared to one recorded in the placebo group (P < 0.05), regarding both positive (P = 0.011) and negative emotions (P = 0.012).

The decrease in the self-rating scale of sleep score, suggesting better sleep quality, was detected in both groups after a study period. Still, the magnitude of the decrease was greater in the treatment group (P < 0.05). The effect of HRT was the most prominent in reducing the rate of insufficient sleep or wakefulness (P = 0.01).

The study from Liu et al[31] has enhanced our understanding of the short-term HRT benefits in the alleviation of menopausal symptoms and reducing mood swings and sleep disorders. The use of estrogen plus progesterone in the study is of particular value regarding mental health because while there is evidence of the antidepressant benefits of estrogen in perimenopausal women, the data on combination therapy are still sparse and inconclusive[10].

However, the main limitation of the study is the short duration since the intervention period was just 3 × 28 days. For future studies, it would be of great value to extend the trial period and establish if the reported benefits of HRT sustain or slightly diminish over time. Apart from that, the study population was not divided according to the duration of menopause or body mass index, so it remained unclear if the specific subpopulation of women showed a higher rate of relief of menopausal symptoms. Conducting future trials should also address long-term concerns, such as cancer risk. As long as the patient’s mental health issues are addressed regarding the fear of developing estrogen-sensitive cancer, the additional evidence-based safety profile of HRT along with an education of both patients and clinicians could contribute to the elimination of treatment barriers.

CONCLUSION

Despite the rising awareness regarding menopausal symptoms, there is still an unmet need for safe and widely accepted treatment options to address VMS and mood and sleep disturbances that healthcare providers frequently neglect. According to available data, HRT is an effective therapeutic strategy in women with a low risk of complications if started at an appropriate time and manner and periodically assessed. Combined estrogen-progesterone therapy in a woman with a uterus could provide relief of symptoms and lead to better QoL. Even with the limitations mentioned above, the study by Liu et al[31], published in the Journal, is a valuable piece of work adding points to our current understanding of the role of HRT in menopausal women. If there are medical contraindications, or the woman is not motivated for HRT, nonpharmacological interventions may be the treatment of choice to alleviate the symptoms and probably general health. In the future, assessing the genetic variations in estrogen metabolism and clarifying the role of kisspeptin, neurokinin B, and other neuropeptides controlling the reproductive axis could have a huge potential for developing novel treatments that target menopausal symptoms without increasing the possible risks.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Ms. Jerrin JF for providing the audio clip for the core tip of this article.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade C

Novelty: Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B

P-Reviewer: Dağ Tüzmen H S-Editor: Fan M L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

Contributor Information

Sanja Borozan, Department of Endocrinology, Clinical Centre of Montenegro, Podgorica 81000, Montenegro; Faculty of Medicine, University of Montenegro, Podgorica 81000, Montenegro.

Abul Bashar M Kamrul-Hasan, Department of Endocrinology, Mymensingh Medical College Hospital, Mymensingh 2200, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Joseph M Pappachan, Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Preston PR2 9HT, United Kingdom; Faculty of Science, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester M15 6BH, United Kingdom; Department of Endocrinology, Kathmandu Medical College, Manipal University, Manipal 576104, India. drpappachan@yahoo.co.in.

References

- 1.Badawy Y, Spector A, Li Z, Desai R. The risk of depression in the menopausal stages: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2024;357:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu H, Liu J, Li P, Liang Y. Effects of mind-body exercise on perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause. 2024;31:457–467. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000002336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jia Y, Zhou Z, Xiang F, Hu W, Cao X. Global prevalence of depression in menopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2024;358:474–482. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kingsberg SA, Schulze-Rath R, Mulligan C, Moeller C, Caetano C, Bitzer J. Global view of vasomotor symptoms and sleep disturbance in menopause: a systematic review. Climacteric. 2023;26:537–549. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2023.2256658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haufe A, Baker FC, Leeners B. The role of ovarian hormones in the pathophysiology of perimenopausal sleep disturbances: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2022;66:101710. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2022.101710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogervorst E, Craig J, O'Donnell E. Cognition and mental health in menopause: A review. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;81:69–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2021.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santoro N, Roeca C, Peters BA, Neal-Perry G. The Menopause Transition: Signs, Symptoms, and Management Options. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106:1–15. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilfarb RA, Leuner B. GABA System Modifications During Periods of Hormonal Flux Across the Female Lifespan. Front Behav Neurosci. 2022;16:802530. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2022.802530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El Khoudary SR, Greendale G, Crawford SL, Avis NE, Brooks MM, Thurston RC, Karvonen-Gutierrez C, Waetjen LE, Matthews K. The menopause transition and women's health at midlife: a progress report from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Menopause. 2019;26:1213–1227. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maki PM, Kornstein SG, Joffe H, Bromberger JT, Freeman EW, Athappilly G, Bobo WV, Rubin LH, Koleva HK, Cohen LS, Soares CN. Guidelines for the Evaluation and Treatment of Perimenopausal Depression: Summary and Recommendations. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2019;28:117–134. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.27099.mensocrec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fang Y, Liu F, Zhang X, Chen L, Liu Y, Yang L, Zheng X, Liu J, Li K, Li Z. Mapping global prevalence of menopausal symptoms among middle-aged women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:1767. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-19280-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon JL, Rubinow DR, Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Xia K, Schmidt PJ, Girdler SS. Efficacy of Transdermal Estradiol and Micronized Progesterone in the Prevention of Depressive Symptoms in the Menopause Transition: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:149–157. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J, Yin J, Song X, Lai S, Zhong S, Jia Y. The effect of exogenous estrogen on depressive mood in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Psychiatr Res. 2023;162:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lozza-Fiacco S, Gordon JL, Andersen EH, Kozik RG, Neely O, Schiller C, Munoz M, Rubinow DR, Girdler SS. Baseline anxiety-sensitivity to estradiol fluctuations predicts anxiety symptom response to transdermal estradiol treatment in perimenopausal women - A randomized clinical trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2022;143:105851. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2022.105851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maki PM, Panay N, Simon JA. Sleep disturbance associated with the menopause. Menopause. 2024;31:724–733. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000002386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker FC, Lampio L, Saaresranta T, Polo-Kantola P. Sleep and Sleep Disorders in the Menopausal Transition. Sleep Med Clin. 2018;13:443–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2018.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uenoyama Y, Nagae M, Tsuchida H, Inoue N, Tsukamura H. Role of KNDy Neurons Expressing Kisspeptin, Neurokinin B, and Dynorphin A as a GnRH Pulse Generator Controlling Mammalian Reproduction. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021;12:724632. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.724632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrington YA, Parisi JM, Duan D, Rojo-Wissar DM, Holingue C, Spira AP. Sex Hormones, Sleep, and Memory: Interrelationships Across the Adult Female Lifespan. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:800278. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.800278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duralde ER, Sobel TH, Manson JE. Management of perimenopausal and menopausal symptoms. BMJ. 2023;382:e072612. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-072612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thurston RC, Aslanidou Vlachos HE, Derby CA, Jackson EA, Brooks MM, Matthews KA, Harlow S, Joffe H, El Khoudary SR. Menopausal Vasomotor Symptoms and Risk of Incident Cardiovascular Disease Events in SWAN. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e017416. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.017416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Witkowski S, Evard R, Rickson JJ, White Q, Sievert LL. Physical activity and exercise for hot flashes: trigger or treatment? Menopause. 2023;30:218–224. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000002107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chin KY. The Relationship between Follicle-stimulating Hormone and Bone Health: Alternative Explanation for Bone Loss beyond Oestrogen? Int J Med Sci. 2018;15:1373–1383. doi: 10.7150/ijms.26571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ambikairajah A, Walsh E, Cherbuin N. A review of menopause nomenclature. Reprod Health. 2022;19:29. doi: 10.1186/s12978-022-01336-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karimi L, Mokhtari Seghaleh M, Khalili R, Vahedian-Azimi A. The effect of self-care education program on the severity of menopause symptoms and marital satisfaction in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22:71. doi: 10.1186/s12905-022-01653-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Genazzani AR, Monteleone P, Giannini A, Simoncini T. Hormone therapy in the postmenopausal years: considering benefits and risks in clinical practice. Hum Reprod Update. 2021;27:1115–1150. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmab026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cappola AR, Auchus RJ, El-Hajj Fuleihan G, Handelsman DJ, Kalyani RR, McClung M, Stuenkel CA, Thorner MO, Verbalis JG. Hormones and Aging: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108:1835–1874. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgad225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller VM, Taylor HS, Naftolin F, Manson JE, Gleason CE, Brinton EA, Kling JM, Cedars MI, Dowling NM, Kantarci K, Harman SM. Lessons from KEEPS: the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study. Climacteric. 2021;24:139–145. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2020.1804545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lambrinoudaki I, Armeni E, Goulis D, Bretz S, Ceausu I, Durmusoglu F, Erkkola R, Fistonic I, Gambacciani M, Geukes M, Hamoda H, Hartley C, Hirschberg AL, Meczekalski B, Mendoza N, Mueck A, Smetnik A, Stute P, van Trotsenburg M, Rees M. Menopause, wellbeing and health: A care pathway from the European Menopause and Andropause Society. Maturitas. 2022;163:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2022.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kissinger D. Hormone replacement therapy perspectives. Front Glob Womens Health. 2024;5:1397123. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2024.1397123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prior JC, Cameron A, Fung M, Hitchcock CL, Janssen P, Lee T, Singer J. Oral micronized progesterone for perimenopausal night sweats and hot flushes a Phase III Canada-wide randomized placebo-controlled 4 month trial. Sci Rep. 2023;13:9082. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-35826-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Q, Huang Z, Xu P. Effects of hormone replacement therapy on mood and sleep quality in menopausal women. World J Psychiatry. 2024;14:1087–1094. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i7.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]