Abstract

Objective

Left bundle branch area pacing (LBBAP) is a novel physiological pacing method for treating left ventricular dyssynchrony. LBBAP is often delivered using lumenless leads (LLL). However, recent studies have also reported the use of style-driven leads (SDL). This study is the first systematic review comparing the outcomes of LBBAP with SDL vs. LLL.

Methods

The review and meta-analysis included all available comparative studies published on Embase, PubMed, Web of Science, CENTRAL, and Scopus up to 6th March 2024.

Results

Eight observational studies were included in the review. Meta-analysis showed that success rates of LBBAP performed with LLL and SDL were comparable (OR: 1.72 95% CI: 0.94, 3.17 I2 = 38%). Duration of implantation and total procedural duration were significantly lower in LBBAP performed with SDL. The pacing threshold was significantly higher, while pacing impedance was significantly lower in the SDL compared to the LLL group. Pacing QRS interval, R-wave amplitude, and stimulus to peak left ventricular activation time were similar in the two groups. Intra-operative and post-operative dislodgement were significantly higher in the SDL group, but no difference was noted in intra-operative perforation and pneumothorax risk.

Conclusion

Limited evidence from observational studies with inherent selection bias shows that success rates for LBBAP may not differ between SDL and LLL. While implantation of SDL may be significantly faster, it carries a higher risk of lead dislodgement. Both SDL and LLL are associated with comparable pacing characteristics except for reduced pacing impedance with SDL.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12872-024-04273-4.

Keywords: Conduction-system pacing, Lead, LBBAP, Physiologic pacing

Introduction

Right ventricular pacing has been the established treatment modality for patients requiring continuous ventricular pacing [1]. However, concerns regarding reduced left ventricular synchrony, decreased left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and the risk of pacemaker-induced cardiomyopathy have led to the development of other pacing strategies, such as His bundle pacing [2, 3]. However, His bundle pacing is technically difficult, requires longer procedural duration, high pacing thresholds, and has a high risk of early battery depletion as well as lead dislodgement [4, 5]. Huang et al [6] in 2017 reported that left bundle branch area pacing (LBBAP) could be an alternative pacing strategy to His bundle pacing that may overcome the limitations of other pacing methods. LBBAP includes left bundle branch pacing, left fascicular pacing, and left ventricular septal pacing and has been included in the recent 2021 ESC guidelines [1]. Long-term research shows that LBBAP is a safe strategy with high success rates and low complications. It also requires a low pacing threshold and produces a narrow QRS interval [7].

LBBAP is commonly performed using lumenless leads (LLL), such as Medtronic 3830 lead, in combination with the Medtronic C315HIS and C304-HIS delivery systems [6]. However, with rapidly advancing technology, several new delivery systems with style-driven leads (SDL) have become increasingly popular. SDL has the advantages of greater stiffness, allowing septal penetration and the possibility of continuous pacing via the stylet to estimate the depth of the lead while screwing it in position [8]. However, SDL have larger diameters and a retractable helix design which is not as robust as LLL [9]. Recently, several studies have attempted to compare the efficiency of LBBAP with SDL and LLL [10–12]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no review has collated such data to examine the difference in outcomes between the two leads. This study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis comparing outcomes of LBBAP performed with SDL vs LLL.

Material and methods

Search methodology

This PRISMA-compliant and PROSPERO registered review (CRD42024520050) began with a detailed and systematic search of the Embase, PubMed, Web of Science, CENTRAL, and Scopus databases. The search was concluded by two reviewers with the help of an experienced medical librarian. All peer-reviewed articles, irrespective of publication date, were searched provided they were available online until 6th March 2024. Additionally, https://clinicaltrials.gov and Google Scholar were searched for gray literature. The following keywords were used: left bundle branch area pacing, stylet, lumenless, and leads. The following two search queries were used across databases: 1) (Left bundle branch area pacing) AND (leads) and 2) ((stylet) AND (lumenless)) AND (left bundle branch area pacing).

The search outcomes of all repositories were collated and then deduplicated using reference manager software (EndNote). Primary eligibility was assessed by reading the titles and abstracts of the unique articles. Screening of the studies was done by the two investigators who eliminated the irrelevant publications. Potentially eligible studies were acquired for further full-text review. Finally, eligible articles were selected for this review. The literature search was further supplemented by reading the bibliography of included studies for additional publications.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

All study designs.

Conducted on patients undergoing LBBAP for any indication.

Comparing outcomes of SDL and LLL.

Assessed success rates, pacing parameters, procedure duration, duration of implantation, and/or complications.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

Abstracts, non-comparative studies, review articles.

Duplicate studies.

Studies not reporting data on LBBAP.

Criteria for LBBAP were not predefined, and all definitions provided by the studies were accepted. If overlapping data were encountered, the article with a greater number of patients was included.

Quality of studies

The Newcastle Ottawa Scale was used to examine the risk of bias due to the observational nature of included studies [13]. The scale ranged from zero to nine points. Studies with 8–9 points were considered high quality, studies with 6–7 were of medium quality, and studies with < 6 points were of poor quality.

Data management

The following information was extracted from studies: name of author, study type, location, indication of LBBAP, criteria for LBBAP, kind of lead, sample size, demographic details, comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation), LVEF, baseline QRS interval, left atrial diameter, intraventricular conduction delay, left bundle branch block, and follow-up.

Data on study outcomes: success rate, procedural duration (mins), duration of implantation of leads mins), pacing parameters [QRS duration (ms), pacing impedance (ohm), pacing threshold (V), and R-wave amplitudes (mV), stimulus to peak left ventricular activation time (stim-LVAT) (ms)], and complications [intraoperative perforation, intraoperative and postoperative lead dislodgement, pneumothorax] were extracted by two authors. Study outcomes were chosen based on data reporting from the included studies. Meta-analysis was performed for analyzable outcomes reported in at least three studies. Additional data were not sought from the corresponding authors. Data on pacing characteristics was obtained immediately following lead implantation. As follow-up duration varied, final follow-up data could not be pooled.

Statistical analysis

Random-effects meta-analysis was conducted using Review Manager 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). Ordinal and continuous data were combined to obtain the odds ratio (OR) and mean difference (MD), respectively. Heterogeneity among studies was quantified using the I2 statistics and the Chi-square test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and an I2 value of 50% or more indicated the presence of heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding one study at a time and reanalyzing the data. The funnel plot on success rates assessed publication bias.

Results

Search results

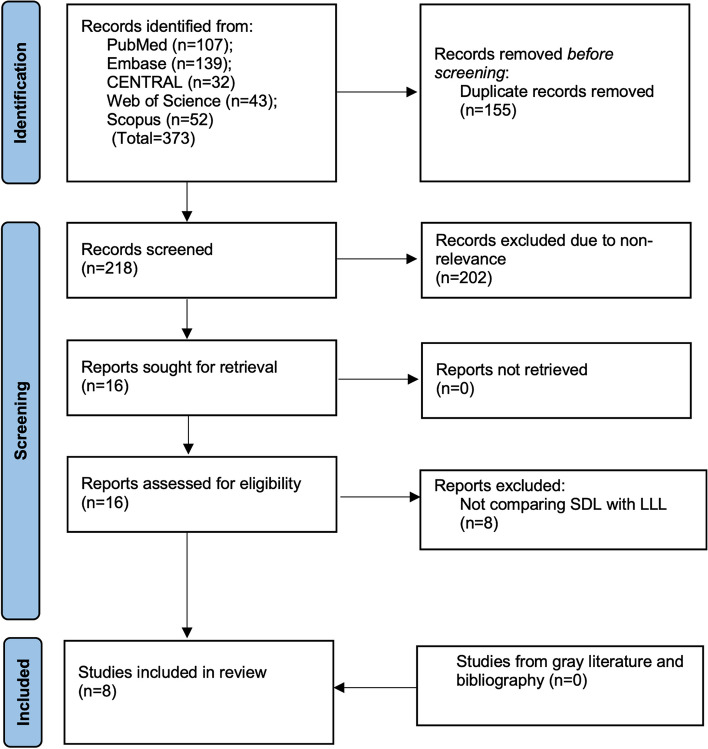

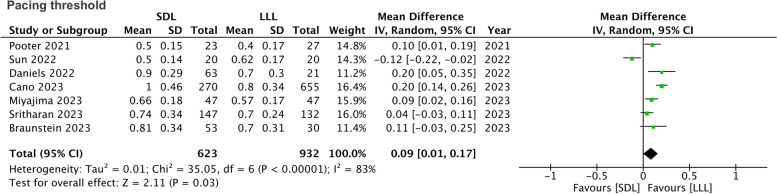

A systematic search of the databases identified 373 articles. Of them, 155 were removed as duplicates. Titles and abstracts of the remaining 218 studies were screened, and 16 full texts were selected for further analysis. Eight studies finally met the inclusion criteria [10–12, 14–18] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Details of study selection

Baseline information

All included studies were observational studies, either retrospective or prospective in design (Table 1). All data was published between the years 2021 to 2023. While all studies were from single countries, one was a multi-national study. The study by Jastrzębski et al(11) included data from 14 European hospitals. Two other studies included in this review, Pooter et al(12) and Cano et al. (16), may have contributed their data for the study of Jastrzębski et al(11) as the enrollment periods of the studies overlapped. Hence, to avoid duplication of data in the meta-analysis, we included the studies of Pooter et al. (12) and Cano et al. (16) only for outcomes that were not reported by Jastrzębski et al. (11). This was done as the study of Jastrzębski et al(11) had a significantly larger sample size as compared to the other two studies.

Table 1.

Study details

| Study | Location | Type | Indication | Type of SDL | Type of LLL | LBBP confirmation | Follow-up | NOS score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sritharan 2023(18) | Switzerland | P | AVB |

Solia S 60, Tendril STS, Ingevity, Vega delivered through Selectra 3D 55 or 65 curve |

3830-69 SelectSecure delivered through C-315 His sheath or Selectra 3D | Presence of a clear QRS transition with decrementing output during unipolar pacing, V6RWPT < 75 ms (or < 80 ms in case of left bundle or bifascicular block, non-specific intra-ventricular conduction delay, wide escape rhythm or paced rhythm), or V6-V1 interpeak interval > 44 ms | 7.7 ± 5.8 months | 5 |

| Miyajima 2023(15) | Japan | R | Bradycardia | Solia S 60 delivered through Selectra 3D | 3830 SelectSecure delivered through C-315 His sheath | (I) paced QRS morphology with an RBBB- like pattern (qR or rSR’ morphology in V1) and (II) stim-LVAT that prolonged abruptly with decreasing output or remained constantly short at the threshold test in different outputs. | 12 months | 6 |

| Cano 2023(16) | Spain, USA | R | Bradycardia or CRT | Solia S60, Ingevity, Tendril 2088TC delivered through Selectra 42–55, SPSCC 2/3, or His-Pro | 3830 SelectSecure delivered through C-315 His sheath | Presence of a paced QRS with RBBB morphology and at least 1 of the following criteria: (1) QRS transition (nonselective-LBBP to selective-LBBP or nonselective -LBBP to LVSP) during threshold testing or programmed stimulation; (2) presence of LBB potential with current of injury; (3) retrograde His-bundle potential with stim-His ,35 ms; or (4) left bundle potential–V6 R-wave peak time (RWPT) 5 stim– V6 RWPT (610 ms) | 16.4 [9.6–24.6] months | 6 |

| Braunstein 2023(10) | USA | R | Heart block, Sick sinus or tachy-brady syndrome | SSPC 1,2,3,4; Selectra 3D | Medtronic C315HIS, 310HS | RBBB morphology during unipolar pacing and at least 1 of the following criteria (1) a left bundle branch potential recording, (2) a transition from nonselective to selective LBB capture, (3) a transition from nonselective LBB capture to LV septal capture, (4) a peak LVAT < 90 msec, (5) a V6–V1 interpeak interval > 40msec | 42.2 ± 62.6 days | 5 |

| Sun 2022(17) | China | R | AVB, sinus node dysfunction, reflex syncope | FINELINE II 4471 lead | 3830 SelectSecure delivered through C-315 His sheath | Presence of a paced QRS with RBBB morphology | 6 months | 4 |

| Jastrzębski 2022(11) | Multinational | R | Sick sinus syndrome, AVB, atrial fibrillation, bradycardia, heart failure | Solia S 60, Tendril STS, Ingevity | 3830 SelectSecure | With any one of the following criteria: (1) Diagnostic QRS morphology transition during threshold test. (2) Diagnostic QRS morphology transition during programmed stimulation. (3) Pacing stimulus to V6RWPT < 80 ms in patients with narrow QRS/isolated right bundle branch block patients or < 90 ms in patients with more advanced ventricular conduction system disease (4) LBB potential to V6RWPT interval equal to the stimulus to V6RWP interval (± 10 ms) (5) V6-V1 interpeak interval > 40 ms | 6.4 ± 5.7 months | 6 |

| Daniels 2022(14) | The Netherlands | P | Sick sinus syndrome, AVB, atrial fibrillation, correction left bundle branch block, pacing induced cardiomyopathy | Tendril STS delivered through Selectra 3D | 3830 SelectSecure delivered through C-315 His sheath | Paced morphology of RBBB pattern in leads V1 and V2, identification of the LBB potential at the local EGM recorded with the septal pacing lead, pacing stimulus to LVAT in leads V4–V6 shortening abruptly with increasing output or remaining short and constant at low and high outputs, and maneuvers used for the determination of selective or nonselective LBBP | 30 weeks | 6 |

| Pooter 2021(12) | Belgium | P | Sinus node disease, AVB, heart failure | Solia S delivered through Selectra 3D | 3830 SelectSecure delivered through C-315 His sheath | Incomplete RBBB morphology in lead V1 and a shortened stimulus to peak LVAT among leads V5–V6, which remained constant and short at both low- and high‐output pacing | 3 ± 2.1 months | 6 |

AVB, atrio-ventricular block; SDL, stylet-driven leads; LLL, lumenless leads; P, prospective; R, retrospective; RBBB, right bundle branch block; LV, left ventricular; LVAT, left ventricular activation time; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; LVSB, left ventricular septal block; LBBP, left bundle branch area pacing; V6RWPT, V6 R-wave peak time

The indications of LBBAP varied between studies and mainly included atrioventricular block, sinus node disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, reflex syncope, bradycardia, and tachybrady syndrome. All studies used the 3830 SelectSecure lead (Medtronic, Minnesota, MN, USA), mainly delivered using the C-315 His sheath in the LLL group. The type of SDL varied and included leads like Solia S 60, Tendril STS, Ingevity, Vega, SSPC, and FINELINE II 4471. Follow-up ranged from a mean of 42 days to a median of 16.4 months. Detailed criteria of LBBAP are shown in Table 1. Based on the NOS scale, all studies were of low quality, with a score of 4–6.

Table 2 presents baseline details on sample size, demographics, comorbidities, LVEF, baseline QRS intervals, and other values. In all eight studies, 1025 patients underwent LBBAP using SDL, and 3100 patients underwent LBBAP using LLL. The mean age of the cohort was > 65 years in all studies.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients in the included studies

| Study | Groups | Sample size | Male gender | Mean age (years) | DM (%) | HTN (%) | CKD (%) | CAD (%) | AF (%) | LVEF | Baseline QRS duration (ms) | LAD (mm) | IVCD (%) | LBBB (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sritharan 2023(18) |

SDL LLL |

153 153 |

91 92 |

80 74 |

32 31 |

81 73 |

33 29 |

41 28 |

30 30 |

54.8 ± 2.1 53 ± 2.3 |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Miyajima 2023(15) |

SDL LLL |

47 47 |

16 28 |

80 79 |

30 19 |

70 62 |

36 40 |

28 19 |

32 34 |

66 ± 8.7 66 ± 8.6 |

NR |

35 ± 5.3 36 ± 8.9 |

NR | NR |

| Cano 2023(16) |

SDL LLL |

270 655 |

NR |

76 74 |

34 37 |

76 73 |

34 38 |

13 24 |

NR |

57 ± 12 53 ± 15 |

132 ± 36 141 ± 37 |

NR |

6 4 |

17 24 |

| Braunstein 2023(10) |

SDL LLL |

53 30 |

38 18 |

74.5 73.4 |

23 20 |

66 67 |

71 57 |

44 47 |

38 33 |

59.6 ± 11.9 59.1 ± 11.0 |

NR |

42 ± 11 47 ± 10 |

NR | NR |

| Sun 2022(17) |

SDL LLL |

20 20 |

11 11 |

70.4 70.8 |

15 25 |

70 65 |

NR |

20 30 |

25 25 |

66.3 ± 10.2 64.1 ± 8.9 |

121.1 ± 30.8 126.9 ± 28.7 |

NR |

5 0 |

15 25 |

| Jastrzębski 2022(11) |

SDL LLL |

396 2137 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Daniels 2022(14) |

SDL LLL |

63 31 |

35 12 |

74 75 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

122 ± 36.5 108 ± 26.4 |

NR |

11.1 3.2 |

17.5 9.7 |

| Pooter 2021(12) |

SDL LLL |

23 27 |

17 11 |

72 68 |

NR |

65 52 |

NR |

39 11 |

NR |

53 ± 13.4 53 ± 14.3 |

124 ± 36.9 128 ± 30.9 |

NR |

0 7 |

13 19 |

LAD, left atrial dimension; LBBB, left bundle branch block; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; CKD, chromic kidney disease; CAD, coronary artery disease; AF, atrial fibrillation; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LAD, left atrial diameter; IVCD, intraventricular conduction delay; NR, not reported; SDL, stylet-driven leads; LLL, lumenless leads

Meta-analysis

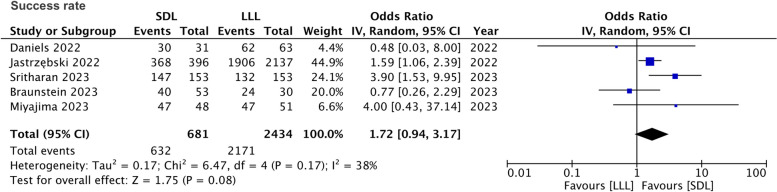

Meta-analysis of success rates based on criteria mentioned in Table 1 indicated no statistically significant difference between SDL and LLL (OR: 1.72 95% CI: 0.94, 3.17 I2 = 38%) (Fig. 2). No publication bias was detected on the funnel plot (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, during sensitivity analysis, the exclusion of the studies of Sritharan et al(18) (OR: 1.47 95% CI: 1.01, 2.13 I2 = 0%) and Braunstein et al(10) (OR: 2.08 95% CI: 1.10, 3.94 I2 = 30%) changed the significance of the results, indicating better success rates for SDL than LDL.

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis comparing success rates between SDL and LLL for LBBAP

Meta-analysis also showed that duration of implantation (MD: -3.29 95% CI: -3.79, -2.79 I2 = 0%) and total procedural duration (MD: -15.59 95% CI: -23.54, -7.65 I2 = 0%) were significantly lower with the use of SDL as compared to LLL (Fig. 3). This significance remained unchanged on sensitivity analysis.

Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis comparing the duration of implantation and procedural duration between SDL and LLL for LBBAP

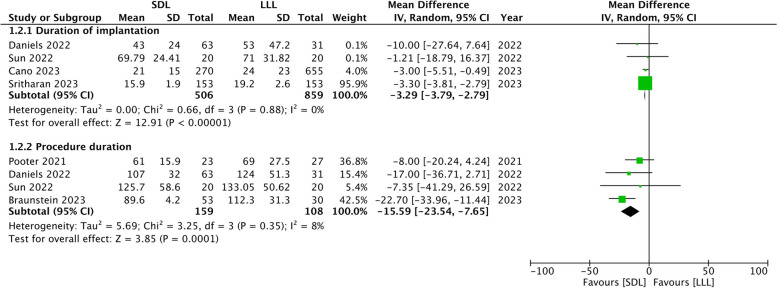

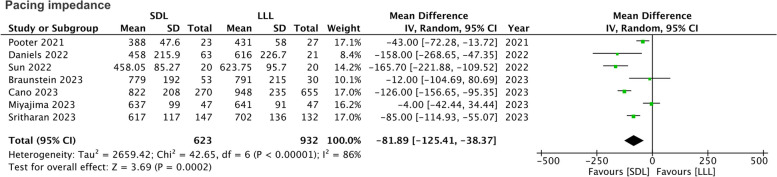

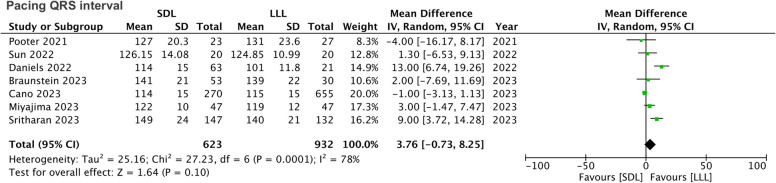

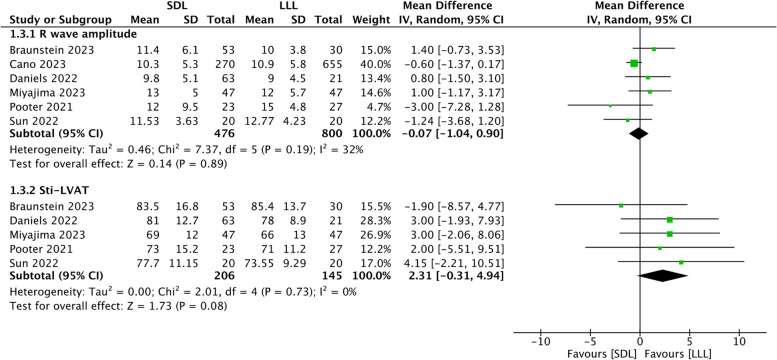

The pacing threshold was significantly higher in the SDL group compared to LLL (MD: 0.09 95% CI: 0.01, 0.17 I2 = 0%) (Fig. 4). These results were not stable on sensitivity analysis, and the association became non-significant after excluding several studies (results not shown). Pacing impedance was significantly lower in the SDL group (MD: -81.89 95% CI: -125.41, -38.37 I2 = 86%) (Fig. 5). Results did not change in significance on sensitivity analysis. The pacing QRS interval was comparable in the two groups (MD: 3.76 95% CI: -0.73, 8.25 I2 = 78%) (Fig. 6). Similarly, no significant intergroup difference was detected in the R wave amplitude (MD: -0.07 95% CI: -1.04, 0.90 I2 = 32%) and sti-LVAT (MD: 2.31 95% CI: -0.31, 8.25 I2 = 78%) (Fig. 7). On the exclusion of the study by Braunstein et al [10], the meta-analysis results on sti-LVTA indicated that LLL was associated with significantly shorter intervals (MD: 3.09 95% CI: 0.23, 5.94 I2 = 0%).

Fig. 4.

Meta-analysis comparing pacing threshold between SDL and LLL for LBBAP

Fig. 5.

Meta-analysis comparing pacing impedance between SDL and LLL for LBBAP

Fig. 6.

Meta-analysis comparing pacing QRS interval between SDL and LLL for LBBAP

Fig. 7.

Meta-analysis comparing R-wave amplitude and sti-LVAT between SDL and LLL for LBBAP

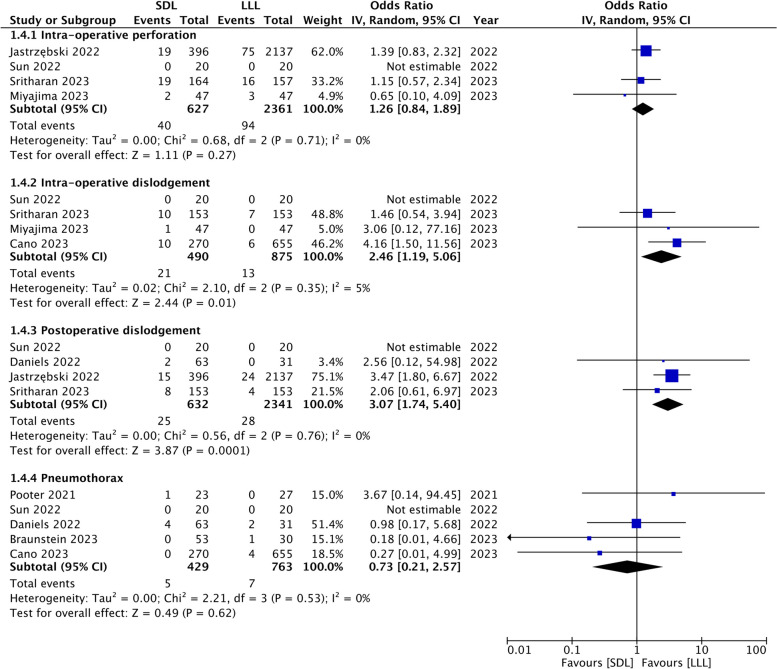

Meta-analysis showed that the risk of intra-operative perforation (OR: 1.26 95% CI: 0.84, 1.89 I2 = 0%) was similar in the two groups. However, intraoperative (OR: 2.46 95% CI: 1.19, 5.06 I2 = 5%) and post-operative dislodgement (OR: 2.76 95% CI: 1.64, 4.63 I2 = 0%) were significantly higher in the SDL group. Both methods were associated with a comparable risk of pneumothorax (OR: 0.73 95% CI: 0.21, 2.57 I2 = 0%) (Fig. 8). Due to the limited number of events per complication and scarce data, sensitivity analysis was not conducted.

Fig. 8.

Meta-analysis comparing complication rates between SDL and LLL for LBBAP

Discussion

This review showed that SDL and LLL were associated with similar success rates of LBBAP, but the delivery time of LBBAP using SDL is shorter. SDL and LLL had comparable pacing characteristics except for reduced pacing impedance with SDL. While the use of SDL may carry a higher risk of intra-operative and postoperative lead dislodgement, no difference was noted in the risk of other complications. Our results should be interpreted cautiously as all included studies were observational with limited sample sizes.

During the early period of conduction system pacing, His bundle pacing was performed with SDL. However, it was associated with low success rates and unstable and high-pacing thresholds. The learning curve associated with the technique, less use of specific sheaths, and His bundle area anatomy were recognized as the major causes for such results with SDL [9, 19]. Later, several studies reported that using LLL with a long preshaped delivery sheath had the advantages of precise catheter delivery and superior contact of pacing lead with the His bundle [20, 21]. Since then, the Medtronic model 3830 pacing lead has been widely embraced due to its unique LLL design, which eliminates the central lumen and reduces the diameter by 40% to only 4.1F [21]. This has led to an increase in the success of His bundle pacing to over 90% and LLL has become the gold standard approach for conduction system pacing, including LBBAP [22]. Nevertheless, the ability of a single delivery system to adapt to all anatomical variations is limited [23]. In this context, the use of SDL has become increasingly popular for LBBAP. Therefore, assessing any differences in LBBAP clinical outcomes with these delivery systems is crucial.

Our review demonstrates that the success rates of LBBAP do not differ with either delivery system. The pooled success rate of SDL in our review was 92.8%, while that of LLL was 89.2%. A comparative study of SDL and LLL by Orlov et al [23] has also reported comparable success rates of the two systems, even for His bundle pacing. Single-arm studies have also demonstrated success rates of > 90% with the use of SDL for LBBAP [12, 24]. The efficacy of SDL for LBBAP thereby eliminates the dependability on a single manufacturer widening the utility of LBBAP. More importantly, the sequential exclusion of two studies on sensitivity analysis showed that SDL may result in significantly better LBBAP success rates. Nevertheless, this observation needs to be viewed with caution due to the small number of studies in the meta-analysis and the observational nature of the data. Without further high-quality evidence, the superiority of SDL over LLL cannot be gauged at this stage.

An interesting finding of our review was the shorter total procedural time and lead implantation time with SDL. SDL was associated with a 3-minute faster lead implantation and around 16-minute shorter total procedure time. The significantly larger reduction in procedural time with SDL is difficult to explain as most of the other steps are similar. It is possible that unmeasured factors like operator experience may have played a role that needs further research. The reduction in implantation time may be attributed to the SDL allowing for continuous pacing during lead insertion, as opposed to intermittent pacing using LLL. The larger diameter of SDL due to the presence of the stylet results in enhanced stiffness that facilitates higher torque and push during lead placement, which may, in turn, reduce implantation time. However, two studies that reported the number of lead penetration attempts showed that there was no significant difference between SDL and LLL [16, 18]. This indicates that the same features of SDL (larger diameter and increased stiffness) may also contribute to difficulty in the sheath and lead alignment with the septum and lead instability at the time of penetration, resulting in an increased number of attempts.

Our review showed that pacing characteristics were not substantially different between the SDL and LLL groups. No significant variation was noted in post-implantation pacing QRS interval, R-wave amplitude, and sti-LVAT between the two groups. A modest, significantly increased pacing threshold was noted with SDL, which lost significance when multiple studies were excluded on sensitivity analysis. A higher acute pacing threshold with SDL could be due to increased local trauma by the larger tip size of the system. Also, the clinical significance of a 0.09 V difference is questionable. Secondly, the meta-analysis found a significantly reduced post-implantation pacing impedance in the SDL group. Pacing impedance depends on the length of the conductor and is inversely related to the contact area. With the use of SDL, such as FINELINE II which has a larger contact area, a lower pacing impedance can be expected.

We have demonstrated that SDL was associated with 2.5 times increased risk of intraoperative dislodgement and three times increased risk of postoperative dislodgement as compared to LLL. However, there was no difference in intra-operative perforation or pneumothorax risk. Such higher risk of dislodgement may be due to the higher diameter of SDL: as compared to the 4.1F diameter of LLL, the larger head diameter is 5.6F, 5.7F, and 6F for the Solia S, Tendril, and Ingevity leads, respectively [18]. The sudden transition between the helix and lead tip diameters and greater overall stiffness can result in larger tension forces within the septum during the beating of the heart, increasing the risk of potential complications [16]. The risk of dislodgement with SDL may also be due to the drill effect that results from the attempts to achieve the best electrocardiogram. Sritharan et al [18] have reported that releasing inner coil tension can cause a backspin of the lead body, resulting in destabilization. Secondly, the risk of complications may be partly influenced by the learning curve. Most clinicians are trained to use the LLL system but differences in the rotation of the lead for achieving adequate depth with SDL may have affected the results. Importantly, due to limited data, we could not thoroughly examine all possible adverse events associated with using SDL. Studies have reported cases of SDL entrapment wherein the helix fails to grip the septal tissue but gets entangled in the septal subendocardial tissue [25, 26]. Further rotation of lead with advancing into the septum can cause complete entrapment, helix fracture, and elongation during the attempts to reposition or remove the lead [26]. Entrapment can be prevented by avoiding continued lead rotation in case of serious torque build-up during lead fixation. If there are signs of entrapment, lead counterclockwise turns should be applied with mild traction on the SDL, and the inner lead coil tension should be maintained to entangle the lead [25]. LLL and SDL have significantly different designs and characteristics, which should be factored in.

This review has several limitations. The predominance of observational studies in literature and the lack of randomized controlled trials is a definite drawback in the comparison of SDL and LLL. Given the overall higher experience of the authors with LLL, there is a risk of selection bias, with less complex cases selected for SDL. Furthermore, an imbalance in the baseline characteristics due to a lack of propensity score matching exacerbates the inherent selection bias of the included observational studies. Secondly, the number of studies and the sample sizes were small. Despite including eight studies, the review could not conduct a quantitative analysis for important outcomes like LVEF, long-term pacing characteristics, and all complications. Variations in the reporting of data and follow-up durations were major limitations for such analyses. Thirdly, there were methodological variations between studies regarding the indications for LBBAP, the SDL system used, and operator experience. The indication of LBBAP can impact the success rates of the procedure. Heart failure patients have reduced success rates compared to patients with normal left ventricular function and dimensions [5]. However, a detailed subgroup analysis could not be conducted for such variables due to the lack of adequate data. Additionally, while most studies used the criteria of Huang et al [6] for identifying LBBAP capture, minor variations could have impacted the results.

Nevertheless, despite limitations, the outcomes of our review are clinically important. We present the first collated literature comparison of SDL vs LLL for LBBAP. All evidence was from recently published studies identified after a thorough literature search. A rigorous analysis of reported data analyzed the maximum possible outcomes. We believe our results would provide a broad perspective to clinicians and allow evidence-based decisions while selecting the system for LBBAP. Current randomized, non-blinded, multicenter clinical trial (https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT06049992) that compares the efficacy and safety of two types of available pacing leads in conduction system pacing may obtain the highest-quality evidence after its completion in September 2025.

Conclusions

Limited evidence from observational studies with inherent selection bias shows that success rates for LBBAP may not differ between SDL and LLL. While the implantation of SDL may be significantly faster, it is linked to a higher risk of lead dislodgement. Pacing characteristics of LBBAP with SDL and LLL were comparable except for reduced pacing impedance with SDL. Given the limitation of the review, our results must be interpreted with caution. Robust randomized controlled trials are needed to further decipher the difference in outcomes between the two systems.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

Not applicable

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design: XC. Data collection and Analysis and interpretation of data: XC, JD. Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: XC.

Funding

Peking University International Hospital Research Funds(YN2022ZD05)

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Glikson M, Nielsen JC, Kronborg MB, Michowitz Y, Auricchio A, Barbash IM, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:3427–520. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tops LF, Schalij MJ, Holman ER, van Erven L, van der Wall EE, Bax JJ. Right ventricular pacing can induce ventricular dyssynchrony in patients with atrial fibrillation after atrioventricular node ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1642–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khurshid S, Epstein AE, Verdino RJ, Lin D, Goldberg LR, Marchlinski FE, et al. Incidence and predictors of right ventricular pacing-induced cardiomyopathy. Hear Rhythm. 2014;11:1619–25. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vijayaraman P, Naperkowski A, Subzposh FA, Abdelrahman M, Sharma PS, Oren JW, et al. Permanent His-bundle pacing: Long-term lead performance and clinical outcomes. Hear Rhythm. 2018;15:696–702. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vijayaraman P, Bordachar P, Ellenbogen KA. The Continued Search for Physiological Pacing: Where Are We Now? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:3099–114. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang W, Su L, Wu S, Xu L, Xiao F, Zhou X, et al. A Novel Pacing Strategy With Low and Stable Output: Pacing the Left Bundle Branch Immediately Beyond the Conduction Block. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33:1736e1. 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Su L, Wang S, Wu S, Xu L, Huang Z, Chen X, et al. Long-Term Safety and Feasibility of Left Bundle Branch Pacing in a Large Single-Center Study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2021;14:e009261. 10.1161/CIRCEP.120.009261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burri H, Jastrzebski M, Cano Ó, Čurila K, de Pooter J, Huang W, et al. EHRA clinical consensus statement on conduction system pacing implantation: executive summary. Endorsed by the Asia-Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS) and Latin-American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS). Europace. 2023;25:1237–48. 10.1093/europace/euad044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Pooter J, Wauters A, Van Heuverswyn F, Le Polain de Waroux J-B. A Guide to Left Bundle Branch Area Pacing Using Stylet-Driven Pacing Leads. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:844152. 10.3389/fcvm.2022.844152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braunstein ED, Kagan RD, Olshan DS, Gabriels JK, Thomas G, Ip JE, et al. Initial experience with stylet-driven versus lumenless lead delivery systems for left bundle branch area pacing. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2023;34:710–7. 10.1111/jce.15789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jastrzębski M, Kiełbasa G, Cano O, Curila K, Heckman L, De Pooter J, et al. Left bundle branch area pacing outcomes: the multicentre European MELOS study. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:4161–73. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Pooter J, Ozpak E, Calle S, Peytchev P, Heggermont W, Marchandise S, et al. Initial experience of left bundle branch area pacing using stylet-driven pacing leads: A multicenter study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2022;33:1540–9. 10.1111/jce.15558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M et al. Oct. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 30 2020.

- 14.Daniëls F, Adiyaman A, Aarnink KM, Oosterwerff FJ, Verbakel JRA, Ghani A, et al. The Zwolle experience with left bundle branch area pacing using stylet-driven active fixation leads. Clin Res Cardiol. 2023;112:1738–47. 10.1007/s00392-022-02048-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyajima K, Urushida T, Tomida Y, Tamura T, Masuda S, Okazaki A, et al. Comparison of the left ventricular dyssynchrony between stylet-driven and lumen-less lead technique in left bundle branch area pacing using myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2023;13:6840–53. 10.21037/qims-23-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cano Ó, Navarrete-Navarro J, Zalavadia D, Jover P, Osca J, Bahadur R, et al. Acute performance of stylet driven leads for left bundle branch area pacing: A comparison with lumenless leads. Hear Rhythm O2. 2023;4:765–76. 10.1016/j.hroo.2023.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun Y, Yao X, Zhou X, Jiang C, Zhang J, Sheng X, et al. Preliminary experience of permanent left bundle branch area pacing using stylet-directed pacing lead without delivery sheath. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2022;45:993–1003. 10.1111/pace.14504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sritharan A, Kozhuharov N, Masson N, Bakelants E, Valiton V, Burri H. Procedural outcome and follow-up of stylet-driven leads compared with lumenless leads for left bundle branch area pacing. Europace. 2023;25. 10.1093/europace/euad295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Deshmukh P, Casavant DA, Romanyshyn M, Anderson K. Permanent, direct His-bundle pacing: a novel approach to cardiac pacing in patients with normal His-Purkinje activation. Circulation. 2000;101:869–77. 10.1161/01.cir.101.8.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zanon F, Baracca E, Aggio S, Pastore G, Boaretto G, Cardano P, et al. A feasible approach for direct his-bundle pacing using a new steerable catheter to facilitate precise lead placement. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:29–33. 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gammage MD, Lieberman RA, Yee R, Manolis AS, Compton SJ, Khazen C, et al. Multi-center clinical experience with a lumenless, catheter-delivered, bipolar, permanent pacemaker lead: implant safety and electrical performance. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2006;29:858–65. 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2006.00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richardson TD, Himes A, Marshall M, Crossley GH. Rationale for and use of the lumenless 3830 pacing lead. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2023;34:769–74. 10.1111/jce.15828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orlov MV, Casavant D, Koulouridis I, Maslov M, Erez A, Hicks A, et al. Permanent His-bundle pacing using stylet-directed, active-fixation leads placed via coronary sinus sheaths compared to conventional lumen-less system. Hear Rhythm. 2019;16:1825–31. 10.1016/J.HRTHM.2019.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu G-I, Kim T-H, Yu HT, Joung B, Pak H-N, Lee M-H. Learning Curve Analyses for Left Bundle Branch Area Pacing with Conventional Stylet-Driven Pacing Leads. J Interv Cardiol. 2023;2023:3632257. 10.1155/2023/3632257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burri H, Jastrzebski M, Cano Ó, Čurila K, De Pooter J, Huang W, et al. EHRA DOCUMENT EHRA clinical consensus statement on conduction system pacing implantation: endorsed by the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS), and Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS) Keywords Conduction system pacing • His bundle pacing • Left bundle branch area pacing • Device implantation. Europace. 2023;25:1208–36. 10.1093/europace/euad043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.le Polain de Waroux J-B, Wielandts J-Y, Gillis K, Hilfiker G, Sorgente A, Capulzini L, et al. Repositioning and extraction of stylet-driven pacing leads with extendable helix used for left bundle branch area pacing. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2021;32:1464–6. 10.1111/jce.15030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.