Abstract

It is widely held that the penetration of cells by alphaviruses is dependent on exposure to the acid environment of an endosome. The alphavirus Sindbis virus replicates in both vertebrate and invertebrate cell cultures. We have found that exposure to an acid environment may not be required for infection of cells of the insect host. In this work, we investigated the effects of two agents (NH4Cl and chloroquine), which raise the pH of intracellular compartments (lysosomotropic weak bases) on the infection and replication of Sindbis virus in cells of the insect host Aedes albopictus. The results show that both of these agents increase the pH of endosomes, as indicated by protection against diphtheria toxin intoxication. NH4Cl blocked the production of infectious virus and blocked virus RNA synthesis when added prior to infection. Chloroquine, in contrast to its effect on vertebrate cells, had no inhibitory effect on infectious virus production in mosquito cells even when added prior to infection. Treatment with NH4Cl did not prevent the penetration of virus RNA into the cell cytoplasm or translation of the RNA to produce a precursor to virus nonstructural proteins. These data suggest that while these two drugs raise the pH of endosomes, they do not block insect cell penetration. These data support previous results published by our laboratory suggesting that exposure to an acid environment within the cell may not be an obligatory step in the process of infection of cells by alphaviruses.

Sindbis virus (the prototype of alphaviruses) is a plus-polarity, single-stranded, enveloped RNA virus. Sindbis virus produces high titers of progeny virus in both vertebrate and invertebrate cells. Experimental evidence suggests that host proteins are also involved in Sindbis virus RNA replication (13, 21, 40). Host proteins, in association with viral replicase components, recognize an RNA sequence or structure and interact with it to initiate viral RNA synthesis. The roles of the host in the production of virus differ dramatically in the two cell types. Participation of host functions in RNA replication is essential in mosquito cells. Enucleated mosquito cells or mosquito cells treated with actinomycin D are incapable of replicating Sindbis virus (13, 45). Similarly treated vertebrate cells produce normal amounts of virus (5, 6). Thus, dramatic differences exist regarding the interaction of alphaviruses with vertebrate and invertebrate hosts.

It is generally accepted that alphaviruses, like some other enveloped viruses, execute the process of virus-cell membrane fusion via protein conformational changes induced in, and dependent on, the low-pH environment of endosomes (24, 25, 34). In the case of Sindbis virus, we have provided experimental evidence that the process of penetration of cells may not be dependent on exposure to low pH (1, 10, 14, 18, 19, 33). The data supporting the contention that alphaviruses enter via an acidic compartment is derived in large part from studies which examine the synthesis of virus RNA in mammalian cells exposed, during the process of penetration, to agents which raise the pH of normally acidic intracellular compartments (24, 25, 34).

The ability of lysosomotropic weak bases such as chloroquine and ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) to prevent the synthesis of virus RNA when present during infection has been widely used to indicate that the route of cell penetration by Sindbis virus required exposure to the acid environment of an endosome (24, 25, 30, 31). This protocol makes two fundamental assumptions: (i) that lysosomotropic weak bases affect no processes related to virus replication or cellular function other than preventing the acidification of intracellular compartments, and (ii) that failure to synthesize virus RNA is an accurate indicator that cell penetration has not taken place. The first assumption would be incorrect if other cellular functions are altered by the presence of these agents. These other cellular functions may play critical roles in virus RNA synthesis. The second assumption may be incorrect, as many viruses such as the alphaviruses require viral protein synthesis and involvement of host cell components before RNA synthesis can take place (2, 7, 8, 12, 13, 21, 40, 41, 45). It is possible that the presence of lysosomotropic weak bases prevents the function of expressed proteins required for viral RNA synthesis without blocking penetration of virus.

To further determine the effects of weak bases on infection of cells by alphaviruses, we examined the effects of the weak bases ammonium chloride and chloroquine on the production of Sindbis virus in BHK and Aedes albopictus cells. Cells were pretreated with either 15 mM NH4Cl or 5 mM chloroquine 5 min prior to infection, and drug was present throughout a subsequent 18-h incubation period. Untreated infected cells served as controls. The medium was collected, and the progeny virus titer was determined on BHK-21 cells. The result of this experiment is presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Effects of weak basic compounds on Sindbis virus replicationa

| Cell type | Yield (PFU)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| No-drug control | 15 mM NH4Cl (% of control) | 5.0 mM chloroquine (% of control) | |

| BHK-21 | 4.8 × 109 | 8.0 × 108 (0.1%) | 2.6 × 106 (0.05%) |

| A. albopictus | 2.4 × 109 | 2.3 × 107 (0.9%) | 3.8 × 109 (158%) |

Cells were infected and drug treated as described in the text. Virus was harvested 18 h after infection. U4.4 cells cloned in this laboratory from A. albopictus cells were cultured at 28°C in Mitsuhashi-Maramorosch medium (36) supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum. The heat-resistant strain of Sindbis virus (SVHR), which serves as wild-type virus, was originally obtained from Elmer Pfefferkorn (Dartmouth Medical College, Hanover, N.H.). Virus stocks were grown in BHK cells at 37°C for 18 h following infection at a multiplicity of infection of 0.01. Virus titers were determined by plaque assay on BHK monolayers.

NH4Cl was found to reduce virus yields by 2 orders of magnitude when applied to either BHK or mosquito cells. Chloroquine dramatically reduced virus yields in BHK cells but in contrast actually increased the virus production in mosquito cells. Increased concentrations of chloroquine (up to 30 mM) produced similar results (data not shown). These results were found to be reproducible and were similar in outcome to results published by Coombs et al. (14).

The results presented in Table 1 have two possible explanations: (i) chloroquine does not impair the ability of mosquito cells to acidify endosomes, and (ii) chloroquine blocks the acidification of endosomes but does not block the infection of the insect cells by Sindbis virus. The ability of such drugs to block the acidification of endosomes can be tested by examining their ability to protect cells from intoxication by diphtheria toxin, a process which is toxin dependent and well documented to require the acidification of endosomes to less than pH 5.5 for entry of the toxin into the cell cytoplasm (44).

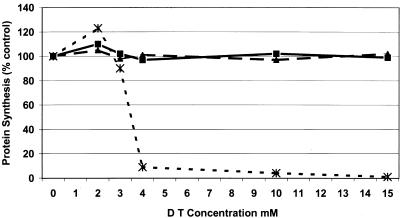

A. albopictus cells were tested for the ability to translocate diphtheria toxin to the cell cytoplasm in the presence or absence of chloroquine or NH4Cl. Cells were treated for 5 min with either 15 mM NH4Cl or 5 mM chloroquine and then challenged with increasing concentrations of diphtheria toxin. Protein synthesis in the cells was measured by the incorporation of [35S]methionine into cellular proteins during a 60-min incubation. In a typical experiment (Fig. 1), we found that both ammonium chloride and chloroquine protected mosquito cells from intoxication at diphtheria toxin concentrations of up to 15 mM. In the absence of drug, host protein synthesis was significantly reduced at a toxin concentration of 4 mM. Similar results were obtained with BHK cells (data not shown). These results suggest that acidification of mosquito cell endosomes is blocked by both ammonium chloride and chloroquine. Diphtheria toxin requires a pH of 5.4 to 5.5 to penetrate endosomal membranes (44); our strain of Sindbis virus requires transient exposure to pH 5.3 to fuse cells in a low-pH-mediated fusion assay (18). Treatment of cells with these agents must, therefore, prevent acidification of endosomes to the level required by Sindbis virus for membrane fusion.

FIG. 1.

Protein synthesis in diphtheria toxin-treated A. albopictus cells. Cellular protein synthesis was measured in the presence (▴) and absence (∗) of 15 mM NH4Cl (▵) or 5.0 mM chloroquine (■). Diphtheria toxin (List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, Calif.) was nicked with trypsin (17). Cells were treated with various concentrations of diphtheria toxin for 2 h and then labeled with Tran35S-label (cysteine-methionine; ICN, Costa Mesa, Calif.) for 1 h. Monolayers were then washed with PBS, and radioactivity incorporated into trichloroacetic acid-precipitable material was quantitated as described previously (18).

In tissue-cultured vertebrate cells, treatment with either chloroquine or NH4Cl has been shown to raise the pH of endosomes and lysosomes (35), to protect from diphtheria toxin intoxication (see above), and to prevent the replication of alphavirus RNA when added prior to infection (25). The data presented above show that although both NH4Cl and chloroquine protect mosquito cells from diphtheria toxin intoxication (by preventing endosome acidification), they have very different effects on the outcome of infection of cells by Sindbis virus. These data suggest that chloroquine has a unique effect, raising the endosome pH but allowing infection to proceed, and that exposure to low pH is not essential for the penetration of mosquito cells by Sindbis virus. NH4Cl must, therefore, have multiple effects on the host cell, blocking some aspect of Sindbis virus replication other than penetration. Alternatively, mosquito cells may have different classes of endosomes: one-class that is sensitive to chloroquine and NH4Cl with respect to acidification and serves as the route of cell penetration by diphtheria toxin, and a second class that is affected only by NH4Cl and provides the route of infection by Sindbis virus.

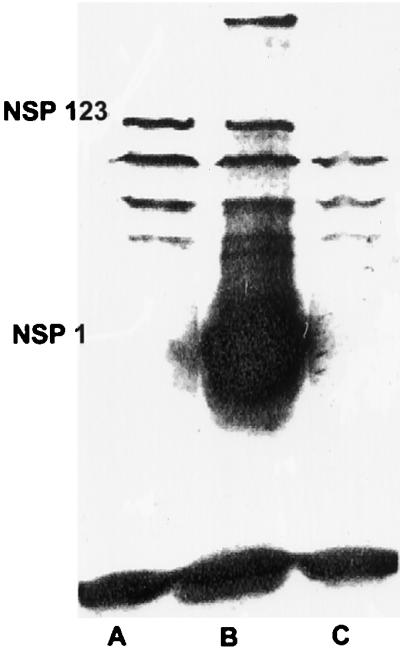

To further elucidate the effects of the weak bases on early events during Sindbis virus infection of insect cells, we examined the expression of Sindbis virus nonstructural proteins in the presence and absence of NH4Cl. Cells were treated, or not treated, with 15 mM NH4Cl for 5 min prior to infection and then infected with 50 to 100 PFU of Sindbis virus per cell. Infection was continued for 4 h at 34°C in the presence or absence of drug at which time the monolayers of equal numbers of cells were processed for analysis by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The resulting gel was probed with iodinated monoclonal antibody specific for rabbit immunoglobulin G as the secondary antibody recognizing the primary polyclonal monospecific anti-Sindbis virus nsP1 antibody. The resulting Western blot is shown in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Production and processing of Sindbis virus nonstructural proteins in A. albopictus cells infected in the presence (lane A) and absence (lane B) of 15 mM NH4Cl. Sindbis virus-infected or mock-infected (lane C) mosquito cells were solubilized with lysis buffer as described previously (42). Proteins separated by SDS-PAGE on a 10.8% gel were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane as described by Burnette (9). The membrane was air dried for 30 min at room temperature and then soaked in blocking solution (10% Carnation instant nonfat dry milk in PBS) with 1% goat serum for 1 h with constant, moderate agitation. The membrane was then incubated in 10% Carnation instant nonfat dry milk–0.05% Tween 20 in PBS–1% goat serum (incubation solution) containing a 1:100 dilution of rabbit anti-Sindbis virus nonstructural protein nsP1 antibody (provided by J. H. Strauss, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena) at room temperature for 1 h with constant, moderate agitation. After three 5-min washes at room temperature with 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS–1% goat serum (washing solution), the membrane was incubated for 1 h at room temperature in 100 ml of incubation solution containing 10 μCi of 125I-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (DuPont New England Nuclear, Boston, Mass.). The membrane was then carefully washed four times with washing solution, air dried for 30 min at room temperature, and exposed to Kodak XAR-5 film.

In the absence of drug, bands corresponding in molecular weight to P123 and nsP1 can be identified (Fig. 2, lane B). A band migrating with a molecular weight roughly equivalent to that of P12 may also be present just above nsP1. We have found that the precursor P1234 cannot be detected in Sindbis virus-infected mosquito cells under the conditions of infection used here (33). In the absence of drug, nsP1 is the major protein species detected in these cells, exhibiting greatly overexposed 125I in the blot (equal numbers of lysed cells in each lane) (Fig. 2, lane B). In the presence of NH4Cl, P123 is detected at levels roughly equivalent to that seen in untreated cells; however, no nsP1 is detected (Fig. 2, lane A). These results indicate that in the presence of NH4Cl, the precursor of the nonstructural proteins of Sindbis virus is produced but is not proteolytically processed into the single gene products; as a result, no progeny RNA is produced. The fact that only low amounts of P123 are detected in drug-treated cells may reflect the fact that protein is produced only from the RNA of the infecting virus. This parental RNA is in low copy number and may also be degraded in the absence of extensive replication. In the absence of drug, progeny RNA is produced and translated into the processed individual proteins, resulting in the production of large amounts of nsP1. Little P1234 remains in these cells after processing. These data suggest that in the presence of NH4Cl, Sindbis virus RNA gains access to the cell cytoplasm and can undergo translation.

The experiments presented above lead to several significant conclusions. (i) The drug chloroquine, which has been shown to block alphavirus RNA synthesis when applied to mammalian cells before and during infection, has no deleterious effects on Sindbis virus replication in similarly treated insect cells (Table 1). (ii) Treatment of insect cells with chloroquine or ammonium chloride protected these cells from diphtheria toxin (Fig. 1). This indicates that these drugs prevented acidification of endosomes to the acid pH threshold (5.3 to 5.5) required for translocation of the toxin across the endosomal membrane. The pH threshold for Sindbis virus-mediated low-pH fusion of cells is 5.3, indicating that in the presence of chloroquine, penetration of insect cells took place in the absence of endosome acidification. (iii) Insect cells infected with Sindbis virus in the presence of ammonium chloride produce a precursor to the virus nonstructural proteins (Fig. 2).

The data presented in this study suggest that in the presence of drugs which block endosome acidification, Sindbis virus infection is blocked at the point of nonstructural protein processing. The mechanism by which this block occurs is unclear. We have previously shown that in A. albopictus (mosquito) cells as in mammalian cells (23, 33), the Sindbis virus nonstructural proteins are associated with lysosomes, suggesting that the cytoplasmic surfaces of lysosomes are the site for Sindbis virus RNA replication in insect cells. The weak basic compounds used in these studies cause the contents of lysosomes to be changed from acid to near neutral pH (35). It is possible that this drastic alteration in chemistry affects the membranes of the lysosomes and directly or indirectly alters the interaction of virus proteins with these structures.

Collectively these data suggest that treatment of cells with agents which impair the process of acidification of intracellular compartments and interfere with lysosomal function also prevents the replication of alphavirus RNA. We propose that the inability to replicate RNA in the insect host is not due to a failure to penetrate cells (as is commonly accepted) but may be due to a failure of the host cells to effectively participate in the establishment of a functional viral replicase.

The conclusions presented above are consistent with previously published observations that Sindbis virus can infect cells that are defective in the ability to acidify endosomes (18) and with the observation that homologous interference (the process by which an initial infecting virus blocks the replication of a second infecting virus), which requires the synthesis of nonstructural proteins (27, 28), is established in the presence of drugs that block endosome acidification (10). Our results are consistent with the morphological observations of Houk et al. (26), which show the fusion of western equine encephalitis virus with the surface of cells lining the alkaline midgut of the mosquito host.

It has been suggested that exposure of virus to low pH prior to cell attachment can “preprime” the virus for membrane fusion such that exposure to the low-pH environment of an endosome is not required for infection (16, 22). These reports also suggested that storing virus frozen in weak buffers such as phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) would result in the exposure to the low pH required to preactivate the virus. DeTulleo and Kirchhausen (16) and Ferlenghi et al. (22) suggested that our practice of storing virus frozen in PBS would account for our published data suggesting that exposure to low pH is not a prerequisite for cell penetration by alphaviruses. The references to publications from our laboratory cited in support of this contention (3, 4, 43) do not, in fact, allude to freezing virus in PBS. We do not store virus used for experimentation either frozen or in PBS, as we have known since the early 1960s that the practice of freezing and thawing virus renders a large percentage of the virus population noninfectious. Furthermore, an experiment published by our laboratory (20) that directly tested the effects of exposure of virus to low pH prior to addition to cells revealed that exposure to low pH rapidly and irreversibly eliminates Sindbis virus infectivity and any possibility for virus prepriming.

It is possible that alphaviruses use different routes of penetration in vertebrate and invertebrate hosts. There are dramatic biochemical and genetic differences between mammalian and mosquito cells. Most noteworthy for this discussion are the differences in composition of the membranes of mammalian and insect cells, as these membranes are the targets of the virus fusion motors. The Insecta do not have the capacity to produce cholesterol (11, 37), and it is not known if cholesterol obtained by dietary routes is incorporated in any significant amount into insect cell membranes. In the case of transovarial transmission of these agents from parent to progeny, dietary cholesterol likely plays no role in the proliferation of these viruses in the organs of male progeny. Insect cell membranes also differ in the composition of phospholipids that have been implicated as essential for fusion of virus with mammalian cells (15, 38, 39). It has been suggested that low-pH-mediated membrane fusion by alphaviruses is absolutely dependent on cholesterol (29, 32, 46). It is therefore possible that a route of infection not requiring low pH or cholesterol exists in the insect host.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Foundation for Research, Carson City, Nev., and by funds from the North Carolina Agricultural Research Station.

We thank Christy McDowell for help with the diphtheria toxin experiments and Jim and Ellen Strauss for providing antibodies to Sindbis virus nonstructural proteins.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abell B A, Brown D T. Sindbis virus membrane fusion is mediated by reduction of glycoprotein disulfide bridges at the cell surface. J Virol. 1993;67:5496–5501. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5496-5501.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams R H, Brown D T. Inhibition of Sindbis virus maturation after treatment of infected cells with trypsin. J Virol. 1982;41:692–702. doi: 10.1128/jvi.41.2.692-702.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anthony R P, Brown D T. Protein-protein interactions in an alphavirus membrane. J Virol. 1991;65:1187–1194. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1187-1194.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anthony R P, Paredes A M, Brown D T. Disulfide bonds are essential for the stability of the Sindbis virus envelope. Virology. 1992;190:330–336. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)91219-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baric R S, Carlin L J, Johnston R E. Requirement for host transcription in the replication of Sindbis virus. J Virol. 1983;45:200–205. doi: 10.1128/jvi.45.1.200-205.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baric R S, Lineberger D W, Johnston R E. Reduced synthesis of Sindbis virus negative-strand RNA in cultures treated with host transcription inhibitors. J Virol. 1983;47:46–54. doi: 10.1128/jvi.47.1.46-54.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barton D J, Sawicki S G, Sawicki D L. Solubilization and immunoprecipitation of alphavirus replication complexes. J Virol. 1991;65:1496–1506. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1496-1506.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burge B W, Pfefferkorn E R. Complementation between temperature-sensitive mutants of Sindbis virus. Virology. 1966;30:214–223. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(66)90097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burnette W M. Western blotting: electrophoretic transfer of proteins from sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels to unmodified nitrocellulose, and radiographic detection with antibody and radioiodinated protein A. Anal Biochem. 1981;112:195–203. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cassell S, Edwards J, Brown D T. Effects of lysosomotropic weak bases on infection of BHK-21 cells by Sindbis virus. J Virol. 1984;52:857–864. doi: 10.1128/jvi.52.3.857-864.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cleverley D, Geller H, Lenard J. Characterization of cholesterol-free insect cells infectible by baculoviruses: effects of cholesterol on VSV fusion and infectivity and on cytotoxicity induced by influenza M2 protein. Exp Cell Res. 1997;233:288–296. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Condreay L D, Adams R H, Edwards J, Brown D T. Effect of actinomycin D and cycloheximide on replication of Sindbis virus in Aedes albopictus (mosquito) cells. J Virol. 1988;62:2629–2635. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2629-2635.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Condreay L D, Brown D T. Suppression of RNA synthesis by a specific antiviral activity in Sindbis virus-infected Aedes albopictus cells. J Virol. 1988;62:346–348. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.1.346-348.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coombs K, Mann E, Edwards J, Brown D T. Effects of chloroquine and cytochalasin B on the infection of cells by Sindbis virus and vesicular stomatitis virus. J Virol. 1981;37:1060–1065. doi: 10.1128/jvi.37.3.1060-1065.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corver J, Moesby L, Erukulla R K, Reddy K C, Bittman R, Wilschut J. Sphingolipid-dependent fusion of Semliki Forest virus with cholesterol-containing liposomes requires both the 3-hydroxyl group and the double bond of the sphingolipid backbone. J Virol. 1995;69:3220–3223. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.3220-3223.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeTulleo L, Kirchhausen T. The clathrin endocytic pathway in viral infection. EMBO J. 1998;17:4585–4593. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drazin R, Kandel J, Collier R J. Structure and activity of diphtheria toxin. II. Attack by trypsin at a specific site in the intact toxin molicule. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:1504–1510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwards J, Brown D T. Sindbis virus infection of a Chinese hamster ovary cell mutant defective in the acidification of endosomes. Virology. 1991;182:28–33. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90644-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edwards J, Brown D T. Sindbis virus-mediated cell fusion from without is a two-step event. J Gen Virol. 1986;67:377–380. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-2-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards J, Mann E, Brown D T. Conformational changes in Sindbis virus envelope proteins accompanying exposure to low pH. J Virol. 1983;45:1090–1907. doi: 10.1128/jvi.45.3.1090-1097.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erwin C, Brown D T. Requirement of cell nucleus for Sindbis virus replication in cultured Aedes albopictus cells. J Virol. 1983;45:792–799. doi: 10.1128/jvi.45.2.792-799.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferlenghi I, Gowen B, de Haas F, Mancini E J, Garoff H, Sjoberg M, Fuller S D. The first step: activation of the Semliki Forest virus spike protein precursor causes a localized conformational change in the trimeric spike. J Mol Biol. 1998;283:71–81. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Froshauer S, Kartenbeck J, Helenius A. Alphavirus RNA replicase is located on the cytoplasmic surface of endosomes and lysosomes. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:2075–2086. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glomb-Reinmund S, Kielian M. The role of low pH and disulfide shuffling in the entry and fusion of Semliki Forest virus and Sindbis virus. Virology. 1998;248:372–381. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helenius A, Marsh M, White J. Inhibition of Semliki Forest virus penetration by lysosomotropic weak bases. J Gen Virol. 1982;58 Pt 1:47–61. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-58-1-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Houk E J, Kramer L D, Hardy J L, Chiles R E. Western equine encephalomyelitis virus: in vivo infection and morphogenesis in mosquito mesenteronal epithelial cells. Virus Res. 1985;2:123–138. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(85)90243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnston R E, Wan K, Bose H R. Homologous interference induced by Sindbis virus. J Virol. 1974;14:1076–1082. doi: 10.1128/jvi.14.5.1076-1082.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karpf A R, Lenches E, Strauss E G, Strauss J H, Brown D T. Superinfection exclusion of alphaviruses in three mosquito cell lines persistently infected with Sindbis virus. J Virol. 1997;71:7119–7123. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.7119-7123.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kielian M. Membrane fusion and the alphavirus life cycle. Adv Virus Res. 1995;45:113–151. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kielian M, Jungerwirth S. Mechanisms of enveloped virus entry into cells. Mol Biol Med. 1990;7:17–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kielian M, Jungerwirth S, Sayad K U, DeCandido S. Biosynthesis, maturation, and acid activation of the Semliki Forest virus fusion protein. J Virol. 1990;64:4614–4624. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.10.4614-4624.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kielian M C, Helenius A. Role of cholesterol in fusion of Semliki Forest virus with membranes. J Virol. 1984;52:281–283. doi: 10.1128/jvi.52.1.281-283.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo T, Brown D T. A 55-kDa protein induced in Aedes albopictus (mosquito) cells by antiviral protein. Virology. 1994;200:200–206. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marsh M, Wellsteed J, Kern H, Harms E, Helenius A. Monensin inhibits Semliki Forest virus penetration into culture cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:5297–5301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.17.5297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maxfield F R. Weak bases and ionophores rapidly and reversably raise the pH of endocytic vesicles in cultured mouse fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1982;95:676–681. doi: 10.1083/jcb.95.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitsuhashi J, Maramorosch K. Leafhopper tissue culture: embryonic, nymphal and imaginal tissues from aseptic insects. Contrib Boyce Thompson Inst. 1964;22:435. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitsuhashi J, Nakasone S, Horie Y. Sterol-free eukaryotic cells from continuous cell lines of insects. Cell Biol Int Rep. 1983;7:1057–1062. doi: 10.1016/0309-1651(83)90011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moesby L, Corver J, Erukulla R K, Bittman R, Wilschut J. Sphingolipids activate membrane fusion of Semliki Forest virus in a stereospecific manner. Biochemistry. 1995;34:10319–10324. doi: 10.1021/bi00033a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nieva J L, Bron R, Corver J, Wilschut J. Membrane fusion of Semliki Forest virus requires sphingolipids in the target membrane. EMBO J. 1994;13:2797–2804. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06573.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pardigon N, Strauss J H. Cellular proteins bind to the 3′ end of Sindbis virus minus-strand RNA. J Virol. 1992;66:1007–1015. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.1007-1015.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pardigon N, Strauss J H. Mosquito homolog of the La autoantigen binds to Sindbis virus RNA. J Virol. 1996;70:1173–1181. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1173-1181.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Presely J F, Brown D T. The proteolytic cleavage of PE2 to envelope glycoprotein E2 is not strictly required for the maturation of Sindbis virus. J Virol. 1989;63:1975–1980. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.1975-1980.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Renz D, Brown D T. Characteristics of Sindbis virus temperature-sensitive mutants in cultured BHK-21 and Aedes albopictus (mosquito) cells. J Virol. 1976;19:775–781. doi: 10.1128/jvi.19.3.775-781.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sandvig K, Tommessen T I, Sand O, Olsnes S. Requirement of a transmembrane pH gradient for the entry of diphtheria toxin into cells at low pH. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:11639–11644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scheefers-Borchel U, Scheefers H, Edwards J, Brown D T. Sindbis virus maturation in cultured mosquito cells is sensitive to actinomycin D. Virology. 1981;110:292–301. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilschut J, Corver J, Nieva J L, Bron R, Moesby L, Reddy K C, Bittman R. Fusion of Semliki Forest virus with cholesterol-containing liposomes at low pH: a specific requirement for sphingolipids. Mol Membr Biol. 1995;12:143–149. doi: 10.3109/09687689509038510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]