Abstract

Background

Short-term exposure to ozone (O3) has been associated with higher stroke mortality, but it is unclear whether this association differs between urban and rural areas. The study aimed to compare the association between short-term exposure to O3 and ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke mortality across rural and urban areas and further investigate the potential impacts of modifiers, such as greenness, on this association.

Methods

A multi-county time-series analysis was carried out in 19 counties of Shandong Province from 2013 to 2019. First, we employed generalized additive models (GAMs) to assess the effects of O3 on stroke mortality in each county. We performed random-effects meta-analyses to pool estimates to counties and compare differences in rural and urban areas. Furthermore, a meta-regression model was utilized to assess the moderating effects of county-level features.

Results

Short-term O3 exposure was found to be associated with increased mortality for both stroke subtypes. For each 10-µg/m3 (lag0-3) rise in O3, ischaemic stroke mortality rose by 1.472% in rural areas and 1.279% in urban areas. For each 0.1-unit increase in the Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) per county, the ischaemic stroke mortality caused by a 10-µg/m3 rise in O3 decreased by 0.60% overall and 1.50% in urban areas.

Conclusions

Our findings add to the evidence that short-term O3 exposure increases ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke mortality and has adverse effects in urban and rural areas. However, improving greenness levels may contribute to mitigating the detrimental effects of O3 on ischaemic stroke mortality.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-024-20454-4.

Keywords: Ozone, Greenness, Rural, Urban, Stroke, Mortality

Background

Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) concentrations have declined, but ozone (O3), another widely recognised significant air pollutant, has remained stable or increased in recent years with global warming and the proliferation of motoring, particularly in central and eastern China [1, 2]. Thus, O3 pollution causes public health problems that need to be taken seriously.

More and more studies have suggested that O3 exposure increases excess mortality, particularly cardiovascular disease mortality [3, 4]. Stroke is a significant subtype of cardiovascular disease, which frequently leads to death and significantly contributes to disability, particularly bearing a substantial burden in China [5]. In China, 2.19 million stroke-related deaths occurred in 2019, accounting for more than 22% of all deaths [6]. As two major subtypes of stroke, ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke have distinct aetiologies and prognoses, and thus, O3 exposure may have different acute effects on them. Several studies have explored whether short-term O3 exposure increases two major subtypes of stroke mortality risk. For example, research on 272 cities nationwide found that increases in the daily maximum 8-hour average (DMA8) O3 by 10-µg/m3 resulted in a 0.29% higher stroke mortality [7]. Similarly, research conducted in Jiangsu Province, China, revealed that a 10-µg/m3 increase in DMA8 O3 raised the mortality from ischaemic and haemorrhagic strokes by 0.54% and 0.10%, respectively [8]. Nevertheless, most of this research has been conducted at the urban or rural-urban level as a whole, with relatively fewer studies separately analysing urban and rural areas and comparing the variances between them. This is mainly due to the relatively few monitoring sites for air pollution exposure concentrations in rural areas and the lack of high-quality cause-of-death monitoring data [9, 10]. The structural variances in urban-rural areas have led to variations in environmental exposure and healthcare resource distribution in China, thereby indirectly resulting in significant disparities in stroke mortality [11–13]. Hence, it is imperative to examine the relationship between O3 and the mortality of two-stroke subtypes individually in urban and rural areas.

It is also crucial to examine whether and how regional features can influence the short-term effects of O3 on different subtype stroke mortality, whereas there is a need for epidemiological evidence in urban-rural planning to create optimal natural and health benefits, as well as the importance of stroke management for individual patients. In particular, growing evidence has suggested that long-term greenness exposure is advantageous for health, including reducing stroke mortality, and it has prompted an increasing focus on the importance of greenness [14–16]. We still do not fully understand the mechanisms underpinning greenness’s beneficial effects on stroke. In addition to direct health benefits from greenness, epidemiological evidence suggests that greenness may produce indirect health benefits by reducing particulate matter (PM) pollution, including sedimentation, dispersion, and modifications [17–19]. However, it is unknown how greenness affects the mortality of the O3-related stroke subtype. As urban and rural areas have different motives for developing greenness and different types and ranges of greenness, we also need to explore the role of greenness in O3-related stroke mortality separately in urban and rural areas.

Thus, we examined whether short-term exposure to O3 had distinct effects on ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke mortality in rural and urban areas, using satellite inversion data on O3 concentrations and stroke mortality surveillance data provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Additionally, we explored whether county-level characteristics such as greenness, population density, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, and road density would modify these effects.

Methods

Study sites

Shandong Province is in eastern China, in the warm-temperate monsoon climate zone. We randomly selected 19 counties in Shandong Province using random stratified sampling, including 10 counties (classified as rural areas) and 9 municipal districts (classified as urban areas) [11, 20]. Fig.S1 shows the study area’s geographical location.

Mortality data collection

Daily stroke mortality cases in 19 counties/districts between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2019 were sourced from the mortality surveillance system of the CDC in Shandong Province. Data quality is strictly regulated, starting with cause-of-death classification using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) and the issuance of death certificates by hospital physicians that are then reported to the local county CDC in real-time, whose professionals verify the information on each certificate within a limit of 7 days and periodically check the integrity of the data and the correctness of the coding. Finally, each county CDC uploads the complete data to the provincial CDC for aggregation through the web-based reporting system. In our research, we concentrated on ischaemic stroke (ICD-10 code: I63-I67) and haemorrhagic stroke (ICD-10 code: I60-I62), and the mortality information primarily included age, sex, date of death, and cause of death of the stroke patients [21].

Environmental data and other covariates

Daily air pollutants data, such as DMA8 O3, PM2.5, SO2, NO2, and CO, were extracted for each county/district from the China High Air Pollutants (CHAP, https://wei-jing-rs.github.io/product.html), with a spatial resolution of 10 km × 10 km (PM2.5, 1 km × 1 km). The estimation of these pollutants employed the enhanced space-time extremely randomized trees model, with the detailed procedural framework for these estimations published separately [22, 23]. The results of the final predictions were reliable, with cross-validation coefficients of determination (CV-R2) of 0.87 for O3, 0.92 for PM2.5, 0.80 for CO, 0.84 for NO2, and 0.84 for SO2, respectively [22–25].

The meteorological variables were collected during the study period from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) Reanalysis product, including temperature (°C) and relative humidity (RH, %) [26]. The product is a grid reanalysis dataset covering common meteorological indicators around the world from 1979 to the present. The dataset has a time-frequency of hours and a resolution of 0.25° (≈ 28 km2) in space, i.e., a high temporal and spatial resolution; therefore, it has been extensively applied in recent research [27]. Hourly RH was calculated for 19 counties in Shandong Province based on hourly temperature (T) and dew point temperature (DT) [28]. Ultimately, the hourly data within each location grid were converted to daily average temperature and RH.

Although the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) is the most widely utilized globally due to its ratio properties that eliminate some of the noise resulting from solar angle, topography, and cloud shadows, it is nevertheless subject to large errors and uncertainties due to variations in the atmosphere and canopy backgrounds, and it is highly sensitive to soil backgrounds [29, 30]. Therefore, the enhanced vegetation index (EVI) was used as a measure of greenness in this research. The EVI is regarded as a modified NDVI with enhanced vegetation monitoring capabilities, achieved by separating the canopy background signal and minimizing the impact of atmospheric noise [31]. The EVI is based on Landsat 8 Operational Land Imager (OLI) satellite imagery (http://earthexplorer.usgs.gov) with less than 10% cloudiness at a resolution of 30 m × 30 m, and its range is from (-1, 1), with larger values representing larger vegetation density and negative values indicating water bodies [31]. The county-specific EVI was extracted by taking the average summer (June-August) EVI data in each county from 2013 to 2019. In the sensitivity analysis, we continued to calculate the annual average EVI, annual average NDVI, and summer NDVI using the same technical method as indicators of green exposure.

Moreover, population density and GDP per capita data for 2013–2019 were acquired from county-specific statistical yearbooks [32], and the road density of each county was calculated using real-time updated road vector data from Open Street Map (https://www.openstreetmap.org/).

Statistical analysis

We utilised a two-stage analytical approach to assess the impact of short-term O3 exposure on ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke daily mortality, as well as to further assess potential modifications of county-level characteristics on this effect.

In the first stage, generalized additive models (GAMs) using quasi-Poisson regression were used for time-series analysis to estimate county-level effect values. GAMs can control linear cross-correlation with smooth functions instead of parameter relationships to provide flexible response specifications [33]. In line with previous research, the different lag patterns of O3 were examined, including four single-day lags: lag 0 to lag 3, and five moving average lags: lag 0–1 (i.e., an average of lag 0 and lag 1) to lag 0–5 (i.e., a 6-day moving average of the current and previous 5 days) [34]. The model equations are as follows:

|

Log [E(Yt)] = α + β × Zt + nst (calendar time, df = 7 per year) + nst (temperaturelag0−7, df = 6) + nst (RHlag0−7, df = 3) + as.factor (dow) + as.factor (ph).

where E (Yt) is the expected number of stroke deaths on day t; α represents the intercept; Zt indicates the O3 concentration on day t, µg/m3; β is the regression coefficient for Zt; ns (calendar time) is represented as a natural cubic spline function across calendar time, utilizing 7 degrees of freedom (df) annually to account for long-term trends and seasonal variations [35]; ns(temperaturelag0−7) and ns(RHlag0−7) are natural cubic splines for the same lag period (lag 0–7) with 6 df and 3 df, respectively, to control for nonlinear and lagged effects of meteorological factors [36]; and the factor variables for days of the week (dow) and public holidays (ph) were incorporated to adjust for the difference in baseline mortality for each day [10].

During the second stage, we applied restricted maximum likelihood estimation for the random effects meta-analysis to pool results from 19 counties as well as rural and urban areas separately to generate the average estimates [37]. Subgroup analyses were based on sex, age (0–64 years old and ≥ 65 years old), and season (warm season: May to October, cool season: November to April). Two-sample z-tests were used to assess the differences between subgroup estimates [38]. We primarily presented the results about lag 0–2 and lag 0–3, respectively, as our findings showed that the cumulative effects of O3 on outcomes stabilized and were strongest at these two lag periods. For each 10-µg/m3 rise in O3, we gave point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for changes in the relative risk (RR) and excess risk (ER) [39].

Moreover, we used a multivariate meta-regression model to determine whether the following county-level characteristics modified the associations of O3 with stroke subtype mortality: annual average concentrations of air pollutants (such as PM2.5), summer greenness (EVI), population density, GDP per capita, and road density [40]. The overall exposure-response relationships between O3 and mortality for both stroke subtypes were evaluated utilizing the same approach as in a prior study, including a natural spline with a df of 3 for the pollutant in the model [41].

Finally, several sensitivity analyses were carried out on the main models to assess their robustness: (1) building two-pollutant models with an additional pollutant (i.e., PM2.5, CO, NO2, and SO2); (2) employing substitute df for the smooth functions of the long-term trends (6 to 9), temperature, and RH (3 to 6); (3) changing the lag pattern (lag 0–3, lag 0–14) for temperature and RH; and (4) using annual average EVI, annual average NDVI, and summer NDVI as indicators of greenness exposure.

All statistical analyses were conducted utilizing R version 4.0.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) with the “mgcv” and “metafor” packages. Statistical significance was determined with a two-sided P value < 0.05.

Results

Descriptive results

From 2013 to 2019, a total of 86,873 deaths due to ischaemic stroke were recorded in 19 counties in Shandong Province (51,175 in rural and 35,698 in urban), while 51,876 deaths due to haemorrhagic stroke were recorded (32,821 in rural and 19,055 in urban). A total of 54.4% were male, and 81.7% were over 65 years of age; sex and age exhibited similar distributions in the rural and urban areas, with the highest proportion of males (rural: 60.2%, urban: 39.8%) and older adults (rural: 60.4%, urban: 39.6%) (Table 1). On average, the rural area had higher air pollutant levels、temperature, RH, and greenness, with an average DMA8 O3 concentration (standard deviation [SD]) of 105.22 (48.49) µg/m3, an average temperature of 14.60 (10.40) ℃, a RH of 64.27 (16.18) % and an EVI of 16.18 (0.10). Table S1 details the exposure to air pollution in each of the 19 counties. O3 was found to be significantly negatively correlated with PM2.5 (rs = -0.32), CO (rs = -0.41), NO2 (rs = -0.44), SO2 (rs = -0.36), and RH (rs = -0.02), and significantly positively correlated with temperature (rs = 0.8) (all pairwise P values < 0.001; Fig. S2).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of stroke death counts and environmental variables in 19 counties of Shandong Province, 2013–2019

| Variable | Overall | Rural | Urban |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death counts | |||

| Ischaemic stroke | 86,873 | 51,175 | 35,698 |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 51,876 | 32,821 | 19,055 |

| Sex | |||

| Male (%) | 75,540 (54.4) | 45,463 (60.2) | 30,077 (39.8) |

| Female (%) | 63,209 (45.6) | 38,533 (61.0) | 24,676 (39.0) |

| Age (years) | |||

| 0–64 (%) | 25,414 (18.3) | 15,526 (61.1) | 9888 (38.9) |

| ≥ 65 (%) | 113,335 (81.7) | 68,470 (60.4) | 44,865 (39.6) |

| DMA8 O3 (µg/m3) | 104.98 ± 48.02 | 105.22 ± 48.49 | 104.71 ± 47.49 |

| PM2.5 (µg/m3) | 70.31 ± 45.14 | 73.86 ± 44.75 | 66.37 ± 45.24 |

| Temperature (℃) | 14.44 ± 10.36 | 14.60 ± 10.40 | 14.26 ± 10.31 |

| Relative humidity (%) | 64.12 ± 16.40 | 64.27 ± 16.18 | 63.95 ± 16.64 |

| Greenness (EVI) | 0.54 ± 0.09 | 0.57 ± 0.10 | 0.50 ± 0.06 |

Abbreviations DMA8 O3, daily maximum 8-hour average ozone; PM2.5, particulate matter with a diameter ≤ 2.5 μm; NO2, nitrogen dioxide; CO, carbon monoxide; SO2, sulfur dioxide; EVI, enhanced vegetation index. Environmental variables data are expressed as (mean ± standard deviation)

Relationships of short-term O3 exposure with mortality from two subtypes of stroke

Fig. S3 and Table S2 illustrate the association between O3 and two-stroke subtypes at different lag periods. The association between a 10-µg/m3 increase in O3 and ischaemic stroke mortality was stronger at lag 0–3 (1.344%, 95% CI: 0.782%, 1.908%), while a stronger association was shown with haemorrhagic stroke mortality at lag 0–2 (0.610%, 95% CI: 0.089%, 1.134%). Furthermore, the percentage change seemed to be consistently greater in ischaemic stroke than in haemorrhagic stroke mortality during all considered lag times and in both rural and urban areas (Table S2, Fig. S3, and Fig. S4). Additionally, for every 10-µg/m3 increase in O3 (lag 0–3), the mortality of ischaemic stroke increased more in rural areas (1.472%, 95% CI: 0.859%, 2.088%) than in urban areas (1.279%, 95% CI:0.314%,2.253%), but the difference was not significant (P = 0.743) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Percentage change (95% CI) in mortality for ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke associated with increase of per 10 µg/m3 in O3 concentration

| Ischaemic stroke | Haemorrhagic stroke | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 1.344 (0.782,1.908) | 0.610 (0.089,1.134) |

| By residence | ||

| Rural | 1.472 (0.859,2.088) | 0.525 (-0.149,1.203) |

| Urban | 1.279 (0.314,2.253) | 0.735 (-0.146,1.623) |

| p-value | 0.743 | 0.710 |

Abbreviations O3, ozone; CI, confidence interval. The results reported the impact of O3 on ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke at lag0-3 and lag0-2, respectively

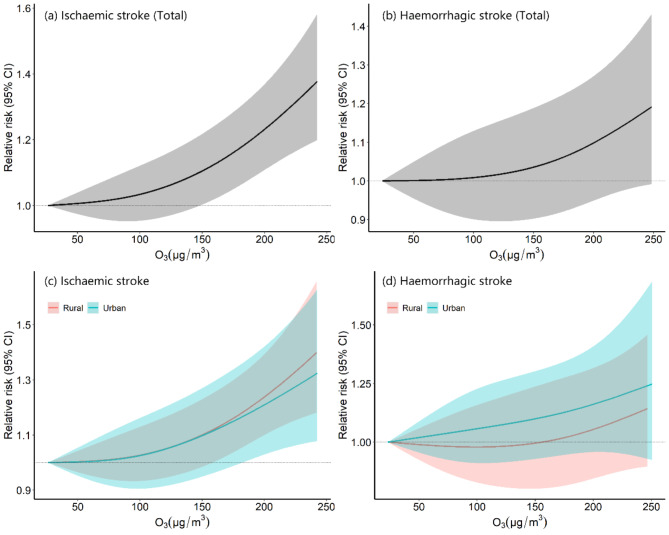

The overall exposure-response relationships between O3 and the mortality for ischaemic stroke (lag 0–3) and haemorrhagic stroke (lag 0–2) are shown in Fig. 1. Generally, we did not observe significant thresholds, implying that even low concentrations of O3 may have health effects, but the relationship was steadier at low concentrations. There was no significant difference between urban and rural areas in terms of ischaemic stroke, but the relationship between O3 and haemorrhagic stroke mortality was consistently higher in urban areas.

Fig. 1.

Concentration-response curves between exposure to ambient O3 and relative risks of mortality for ischaemic (lag 0–3) and for haemorrhagic stroke (lag 0–2)

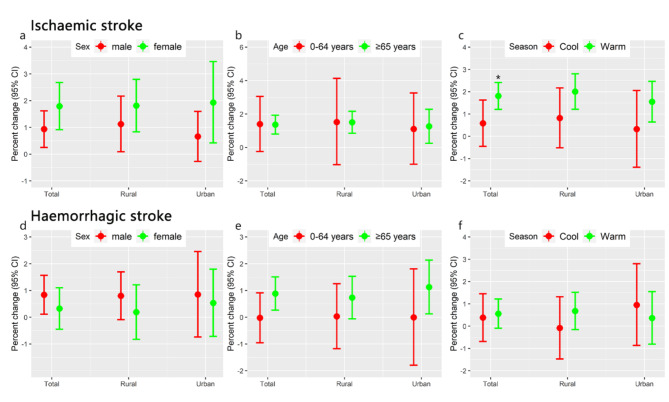

Fig. 2 displays the relationships between O3 and mortality from two stroke subtypes, stratified according to sex, age, and season. In the warm season (1.810%, 95% CI: 1.208%, 2.415%), O3 (lag 0–3) had a significantly higher effect estimates on ischaemic stroke mortality than it did in the cold season (0.581%, 95% CI: -0.453%, 1.626%) (P = 0.047). There was no significant change in effect by age or sex for both stroke subtypes.

Fig. 2.

Percentage change (with 95% CI) in mortality for ischaemic (lag0-3) and haemorrhagic stroke (lag0-2) per 10 µg/m3 increase in short-term O3 exposure, classified by sex, age and season. Abbreviations: O3, ozone; CI, confidence interval. * p-value < 0.05

Modification effects of greenness

Table 3 shows how county-specific characteristics modified the relationship of O3-related stroke subtype mortality. There was a negative correlation between greenness and RRs of mortality from O3-related ischaemic stroke at lag 0–3 days. For every 0.1-unit rise in the average summer EVI, there was an additional 0.60% [-0.60% (95% CI: -1.14% to -0.05%)] decrease in ischaemic stroke mortality associated with O3. In urban areas, this negative association also existed, but it was not significant in rural areas (-0.003, 95%CI: -0.009,0.003). We found no evidence for effect modifications by PM2.5, population density, GDP per capita, or road density.

Table 3.

Meta-regression results of the moderating effect of county-level characteristics on the relationship between O3 and ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke mortality

| Total | Rural | Urban | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ischaemic stroke | |||

| PM2.5 | -0.004 (-0.009, 0.000) | -0.007 (-0.016, 0.001) | -0.003 (-0.009, 0.003) |

| EVI | -0.006 (-0.011, -0.001) | -0.003 (-0.009,0.003) | -0.015 (-0.025, -0.005) |

| GDP per capita | 0.002 (-0.000,0.003) | 0.002 (-0.001,0.005) | 0.002 (-0.001,0.006) |

| Population density | 0.003 (-0.004 0.009) | 0.002 (-0.004,0.009) | 0.003 (-0.013,0.019) |

| Road density | 0.000 (-0.001,0.003) | 0.001 (-0.001,0.002) | 0.001 (-0.006,0.009) |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | |||

| PM2.5 | -0.000 (-0.006,0.005) | -0.008 (-0.017,0.001) | 0.003 (-0.003,0.009) |

| EVI | -0.000 (-0.006,0.006) | -0.001 (-0.008,0.006) | 0.002 (-0.012,0.015) |

| GDP per capita | 0.000 (-0.002,0.002) | 0.002 (-0.002,0.005) | -0.001 (-0.005,0.002) |

| Population density | 0.001 (-0.005,0.007) | 0.002 (-0.006,0.009) | 0.000 (-0.016,0.016) |

| Road density | 0.001 (-0.001,0.003) | 0.001 (-0.001,0.003) | 0.001 (-0.006,0.008) |

Abbreviations O3, ozone; PM2.5, particulate matter with a diameter ≤ 2.5 μm; EVI, enhanced vegetation index; GDP, gross domestic product

Sensitivity analyses

We carried out a set of sensitivity analyses, and Table S3 indicates that after controlling for another pollutant, the impact of O3 on stroke mortality slightly decreased after adjusting for another pollutant (i.e., PM2.5, CO, NO2, and SO2). Findings remained relatively robust based on the variation in confounding parameters (i.e., df and lag structure) in the models for ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke (Table S4; Table S5). When utilising the annual average EVI, annual average NDVI, and summer NDVI as indicators of greenness exposure, a similar association was observed: an increase in greenness exposure resulted in a decrease in ischaemic stroke mortality related to O3. However, this impact was insignificant across total and rural areas (Table S6).

Discussion

This study discovered that short-term O3 exposure was related to higher mortality of ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke. We found a positive association with O3 in rural and urban areas for ischaemic stroke, while the difference between rural and urban areas was not statistically significant. A greater estimated impact was noted for mortality from ischaemic stroke during the warm season. Furthermore, our analysis provided evidence that greenness significantly mitigated the adverse influence of O3 on ischaemic stroke mortality, which also holds for urban areas.

In our study, we discovered that short-term rise in O3 levels was independently related to increased mortality from both subtypes of stroke, which mirrors the previous research findings [42, 43]. For instance, an analysis of 48 major Chinese cities indicated that for every 10-µg/m3 rise in O3, the mortality for ischaemic and haemorrhagic strokes increased by 0.76% and 0.40%, respectively [4]. An additional study conducted in Jiangsu Province calculated that there was a respective 0.54% rise in mortality for ischaemic stroke for each 10-µg/m3 increase in O3 [44]. Another Boston, US study also found a positive association between O3 and lobar cerebral haemorrhage [45]. However, other studies in Jiangsu Province in China, Japan, and Korea did not identify that O3 significantly increased haemorrhagic stroke mortality [44, 46, 47]. Although the two types of stroke have similar levels of O3 exposure and clinical presentations, they are different clinical entities, which means that the biomechanisms underlying the effects of O3 on ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke may be distinct [42]. And it is also possible that the higher mortality of haemorrhagic stroke masks the damaging effects of O3 [44]. In light of this, it is imperative for future studies to collect data from different regions, use diverse analytical strategies, and utilize different model parameters to explore the association between O3 and haemorrhagic stroke. Furthermore, it is important to compare the similarities and differences in the effects of short-term O3 exposure on different types of stroke.

The biomechanisms of the effects of O3 on stroke subtypes, particularly on haemorrhagic stroke risk, are not fully understood, although some seemingly plausible hypotheses have been postulated. It has been proposed that O3 activates local and global inflammation and stimulates the release of blood clotting factors and further peripheral arterial thrombosis, which is strongly associated with ischaemic stroke [48, 49]. Additionally, O3 exposure may be associated with oxidative stress, vascular endothelial dysfunction, and vascular damage, which may cause a range of vascular responses, platelet aggregation, and increased plasma viscosity that directly or indirectly accelerate the atherosclerotic process and may ultimately cause death from ischaemic stroke [50–52]. For haemorrhagic stroke, O3 may lead to direct ischaemic injury, vasoconstriction, and elevated blood pressure [45, 53]. Furthermore, O3 is related to acute endothelial dysfunction (atherosclerosis), which could result in cerebral vascular rupture resulting in death from haemorrhagic stroke [51]. Notably, the potential biomechanisms regarding the associations of O3 with stroke subtypes are relatively complex, as they are all primarily related to the onset and development of vascular ischaemia. However, the exact mechanisms need to be further elucidated, as the current findings lack consistency, and their clinical implications remain uncertain. For instance, some studies concluded short-term O3 exposure did not cause increased blood pressure, vascular dysfunction or affect bidirectional variability in heart rate [54].

Our research also revealed that short-term exposure to O3 was linked to higher ischaemic stroke mortality across rural and urban areas, with the former showing a stronger correlation, but the variance in this link was not statistically significant. This discovery contradicted the previous notion that urbanization has significantly detrimental effects on the health of residents in developing countries [55]. Several research has similar findings to ours [8, 11, 56]. For example, the mortality of stroke rose by 0.87% with every 10-µg/m3 rise in O3 in 43 rural areas of Jiangsu Province, while in 43 urban areas, the mortality of stroke increased by 0.48%, again with no statistically significant difference between the two [8]. Another study that categorised rural and urban areas according to population density found that for every 10-µg/m3 rise in O3, non-accidental mortality rose by 0.37% in rural and 0.23% in urban areas [57]. Although these studies used different criteria to classify rural and urban areas, such as administrative boundaries, population density, and the median percentage of urban residents, the association patterns were consistent with our findings. This may be due to increased exposure to the outdoor environment in rural areas, coupled with a relatively weaker sense of self-protection against air pollution, as well as lower economic and healthcare conditions; rural residents may exhibit greater sensitivity to O3 compared to their urban counterparts [11, 58, 59]. Also, in our research, the average O3 concentration was slightly higher in rural areas. This may be because, in China, rural areas have higher levels of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and the concentration of NOx was lower, resulting in the generation of more O3 [8, 60]. Additional research also suggested that O3 concentrations in rural areas are not only directly affected by local O3 emissions, but that O3 may also spread to neighbouring rural areas as winds change direction when there are headwinds in urban areas [61]. Nevertheless, other studies conducted in Stockholm [62] and Copenhagen [63] have reached the opposite conclusion that residents of urban areas are more susceptible to air pollution. This may be because rural residents in many developed countries can access the same high living conditions and medical services as their urban counterparts. However, due to the unequal allocation of medical resources in China, more advanced medical technology is available only in urban areas [11]. Therefore, rural residents need to raise their awareness of protection against air pollutants and reduce their exposure to high-pollutant environments by adopting appropriate protective measures (e.g., wearing masks). The government should increase investment in governance to improve the rural environment, take measures to enhance the sharing and collaboration of medical resources between urban and rural areas and improve the standard of medical care in rural areas [59].

We discovered a significant effect modification of season on the O3-related ischaemic stroke mortality. In line with the majority of prior research, our findings demonstrated a greater relationship between O3 and ischaemic stroke mortality during the warm season in all areas of our research [7, 64]. From one perspective, the distribution of O3 concentrations is distinctly seasonal, usually higher in summer, and may cause a greater risk of death. From another perspective, since the average temperature in northern China, including Shandong Province, is lower during the winter, residents commonly use home heating, which leads to less opportunity for outdoor activities and less time for natural ventilation, thus further reducing exposure to outdoor O3. In addition, the synergistic effect of O3 and high temperatures may exacerbate the adverse effect of O3 [65]. We also found that the association of O3-related ischaemic stroke mortality was greater among women and younger patients, the difference was not significant. Thus, the susceptibility subgroups for O3-related stroke risk remain to be further identified.

Higher greenness was significantly associated with lower O3-related ischaemic stroke mortality, showing that counties with denser vegetation have a lower risk of O3-related ischaemic stroke mortality. According to an increasing body of evidence, increasing greenness levels significantly reduces particulate matter’s health impacts, including cerebrovascular disease [66–68]. Nevertheless, due to the intricate association between O3 and greenness, limited exploration has been made of the potential moderating role of greenness on the linkage between O3 and health [69, 70]. An individual-level study in the US observed that O3 was positively associated with the atherosclerosis index in areas with less greenness, but this association disappeared in areas with more greenness [19]; a study in Italy also found that 3673 ha of urban parks removed 1.42 kg of O3 per ha per year, which was mainly related to urban tree species [71]; and a study from Mexico estimated that park vegetation removed 1% of O3 pollution per year [72]; these findings were to some extent similar to our findings. We obtained the same findings in urban areas, but this modifying effect of greenness was not found in rural areas. This finding was inconsistent with past research, which has suggested that mortality due to air pollution is lower in rural areas with more greenness, possibly because sufficient vegetation is needed to clean the air of pollutants effectively [73, 74]. Perhaps because our study used cumulative greenness exposure, which to some extent reflects the level of urbanisation, although greenness is lower in urban, the level of healthcare, education, etc., may be higher in urban, which reduces the burden of stroke deaths due to O3 [73]. The presence of greenness did not have a moderating effect on O3-related haemorrhagic stroke mortality. This could be due to the relatively weak association between short-term O3 exposure and haemorrhagic stroke, which made any impact from greenness mitigation insignificant. On the other hand, changes in greenness were also more strongly associated with ischaemic stroke [75, 76]. The small sample size of haemorrhagic stroke may also have affected the accuracy of the results.

Combined with the available evidence, the mechanisms linking greenness and O3 were quite complex, as greenness may not only act as a sink for O3 but also contribute to O3 formation. On the one hand, greenness, especially tree canopies, can be involved in O3 deposition processes through absorption and sorption functions, and the rate of O3 deposition is mainly related to the stomatal conductance of the canopy and leaves as well as the species-dependent gas absorption rate [77, 78]. On the other hand, research has suggested that greenery emits over 1 billion tons of BVOCs annually, especially during droughts, and a greater accumulation of green patches may enhance the concentration of BVOCs emitted from vegetation, which could lead to accelerated O3 formation [79, 80]. Processes of BVOC production and vegetation stomatal deposition may be simultaneous, and how vegetation ultimately affects O3 remains to be investigated further. However, evidence reveals that selecting tree species with low BVOC emissions, such as aspen and birch, in urban planning may yield greater environmental benefits, while greenness in rural areas is mostly from primary forests and agricultural areas [81, 82]. Apart from natural benefits, greenness may modify indoor and outdoor activity patterns, subsequently impacting exposure to a specific air pollution level. For example, higher levels of greenness can promote chances for exercise and social engagement, reduce stress, and improve well-being, among other things, which may mitigate the O3-related stroke burden [83, 84]. Yet some research claims that the greenery in urban areas consists mainly of recreational areas such as parks, which provide residents with more opportunities for exercise [82]. Compared to people living in cities, residents of rural areas engaged in physical exercise far less frequently [85]. In light of the extensive greenness in rural areas, the government should pay more attention to the rational planning and selection of green vegetation. At the same time, rural residents should make full use of the surrounding greenness resources to actively engage in physical exercise and relaxation to promote physical and mental health.

During the study period, China experienced severe and still increasing O3 pollution, with Shandong Province being an agricultural behemoth characterized by a complex urban-rural structure. This offered an opportunity to investigate the relationship between mortality from both subtypes of stroke and short-term O3 exposure in urban and rural areas. Datasets with higher spatial resolutions instead of single-monitoring station measurements may provide more accurate exposure and effect estimates. Furthermore, to our knowledge, our study estimated the crucial role of greenness in the relationship between O3 and stroke subtype mortality in urban and rural areas separately for the first time, which informs the development of adaptive strategies related to stroke prevention. However, several limitations should be noted. First, ecological bias is inherent to time-series studies, and using of O3 concentrations calculated by weighted averaging of gridded data instead of individual exposure levels could have caused exposure measurement errors, which may have caused a downward skewing of risk estimates. Second, the lack of data prevented us from detecting individual-level potential confounding, such as smoking, hypertension, and physical activity; however, these variables do not change substantially in the short term and therefore were unlikely to have a significant confounding effect on our estimates. Third, our method of categorizing rural and urban areas based on administrative divisions was rather crude, and in the future, more precise rural-urban delineation should be done based on individuals’ residential addresses. Finally, our study was based on a province with a high level of O3 pollution, although it has a population of more than 100 million. The generalizability of the results requires caution, given the differences in population vulnerability and exposure levels.

Conclusion

In summary, short-term O3 exposure was found to increase ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke mortality. In both rural and urban areas, we identified a positive correlation between O3 and ischaemic stroke mortality, but there was no significant difference between them. Moreover, the present investigation found that areas with higher greenness had smaller O3 effects on ischaemic stroke mortality, as well as in urban areas, which might provide an important guide for stroke-related public health prevention and urban and rural construction.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Shandong Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Dr. Jing Wei’s team, the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), and the U.S. Geological, providing data on disease, air pollutants, meteorology and greenness, respectively, for all analyses in present study. And, we thank Fernanda T for editing the language of a draft of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- O3

Ozone

- DMA8

Daily Maximum 8-hour Average

- PM2.5

Particulate Matter with a diameter ≤ 2.5 μm

- NO2

Nitrogen Dioxide

- CO

Carbon Monoxide

- SO2

Sulfur Dioxide

- EVI

Enhanced Vegetation Index

- NDVI

Normalized Difference Vegetation Index

- RH

Relative Humidity

- GDP

Gross Domestic Product

- CI

Confidence Interval

- SD

Standard Deviation

- GAM

Generalized Additive Model

- ER

Excess Risk

- RR

Relative Risk

- Df

Degree of freedom

Author contributions

K. Z. and F. H.: Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing-Original draft, Visualization. B. Z.: Resources, Project administration. C. L., H. Y., Y. D., P. Z., and C. L.: Investigation, Software, Data Curation. J. W.: Investigation, Resources. Z. L. and X. G.: Supervision, Project administration. Q. H.: Supervision, Funding acquisition. X. J. and J. M.: Conceptualization, Writing-Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the Natural Science Key Project of the Anhui Provincial Education Department [grant numbers KJ2021A0710], the Natural Science Research Program for Universities in Anhui Province [grant numbers 2023AH040288], Bengbu Medical College Postgraduate Innovation Programme Project [grant numbers Byycx22072] and the Natural Science Research Program for Universities in Anhui Province [grant numbers 2023AH051915].

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of Shandong Province but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the CDC of Shangdong Province.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Review Committees of Bengbu Medical College (Ref. Number: 2022 − 109). A waiver of informed consent was taken by Institutional Review Board of Bengbu Medical College as the data analyzed in this study were at the secondary aggregated level, and no participants were contacted.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Disclosure summary

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ke Zhao and Fenfen He contributed equally to this work and should be considered as co-first authors

Contributor Information

Xianjie Jia, Email: jiaxianjie@bbmc.edu.cn.

Jing Mi, Email: mijing@bbmc.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Lu X, Zhang L, Wang X, Gao M, Li K, Zhang Y, Yue X, Zhang Y. Rapid Increases in Warm-Season Surface Ozone and resulting Health Impact in China since 2013. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 2020;7(4):240–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meng X, Wang W, Shi S, Zhu S, Wang P, Chen R, Xiao Q, Xue T, Geng G, Zhang Q et al. Evaluating the spatiotemporal ozone characteristics with high-resolution predictions in mainland China, 2013–2019. Environ Pollut 2022, 299. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Guo Y, Xie X, Lei L, Zhou H, Deng S, Xu Y, Liu Z, Bao J, Peng J, Huang C. Short-term associations between ambient air pollution and stroke hospitalisations: time-series study in Shenzhen, China. BMJ Open 2020, 10(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Li M, Dong H, Wang B, Zhao W, Zare Sakhvidi MJ, Li L, Lin G, Yang J. Association between ambient ozone pollution and mortality from a spectrum of causes in Guangzhou, China. Sci Total Environ 2021, 754. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Tu W-J, Zhao Z, Yin P, Cao L, Zeng J, Chen H, Fan D, Fang Q, Gao P, Gu Y et al. Estimated Burden of Stroke in China in 2020. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Ma Q, Li R, Wang L, Yin P, Wang Y, Yan C, Ren Y, Qian Z, Vaughn MG, McMillin SE, et al. Temporal trend and attributable risk factors of stroke burden in China, 1990–2019: an analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(12):e897–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yin P, Chen R, Wang L, Meng X, Liu C, Niu Y, Lin Z, Liu Y, Liu J, Qi J et al. Ambient ozone Pollution and Daily Mortality: a nationwide study in 272 Chinese cities. Environ Health Perspect 2017, 125(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Lin C, Ma Y, Liu R, Shao Y, Ma Z, Zhou L, Jing Y, Bell ML, Chen K. Associations between short-term ambient ozone exposure and cause-specific mortality in rural and urban areas of Jiangsu, China. Environ Res 2022, 211. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Qi J, Ruan Z, Qian ZM, Yin P, Yang Y, Acharya BK, Wang L, Lin H. Potential gains in life expectancy by attaining daily ambient fine particulate matter pollution standards in mainland China: a modeling study based on nationwide data. PLoS Med. 2020;17(1):e1003027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang W, Liu C, Ying Z, Lei X, Wang C, Huo J, Zhao Q, Zhang Y, Duan Y, Chen R et al. Particulate air pollution and ischemic stroke hospitalization: how the associations vary by constituents in Shanghai, China. Sci Total Environ 2019, 695. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Zhao S, Liu S, Hou X, Sun Y, Beazley R. Air pollution and cause-specific mortality: a comparative study of urban and rural areas in China. Chemosphere 2021, 262. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Wang H, Gao Z, Ren J, Liu Y, Chang LT-C, Cheung K, Feng Y, Li Y. An urban-rural and sex differences in cancer incidence and mortality and the relationship with PM2.5 exposure: an ecological study in the southeastern side of Hu line. Chemosphere. 2019;216:766–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mueller N, Rojas-Rueda D, Basagaña X, Cirach M, Cole-Hunter T, Dadvand P, Donaire-Gonzalez D, Foraster M, Gascon M, Martinez D, et al. Urban and Transport Planning related exposures and mortality: a Health Impact Assessment for cities. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(1):89–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bauwelinck M, Casas L, Nawrot TS, Nemery B, Trabelsi S, Thomas I, Aerts R, Lefebvre W, Vanpoucke C, Van Nieuwenhuyse A et al. Residing in urban areas with higher green space is associated with lower mortality risk: a census-based cohort study with ten years of follow-up. Environ Int 2021, 148. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Liu X-X, Ma X-L, Huang W-Z, Luo Y-N, He C-J, Zhong X-M, Dadvand P, Browning MHEM, Li L, Zou X-G et al. Green space and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Environ Pollut 2022, 301. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Yu W, Liu Z, La Y, Feng C, Yu B, Wang Q, Liu M, Li Z, Feng Y, Ciren L, et al. Associations between residential greenness and the predicted 10-year risk for atherosclerosis cardiovascular disease among Chinese adults. Sci Total Environ. 2023;868:161643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diener A, Mudu P. How can vegetation protect us from air pollution? A critical review on green spaces’ mitigation abilities for air-borne particles from a public health perspective - with implications for urban planning. Sci Total Environ 2021, 796. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Klompmaker JO, Hart JE, James P, Sabath MB, Wu X, Zanobetti A, Dominici F, Laden F. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease hospitalization – are associations modified by greenness, temperature and humidity? Environ Int 2021, 156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Riggs DW, Yeager R, Conklin DJ, DeJarnett N, Keith RJ, DeFilippis AP, Rai SN, Bhatnagar A. Residential proximity to greenness mitigates the hemodynamic effects of ambient air pollution. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021;320(3):H1102–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He F, Wei J, Dong Y, Liu C, Zhao K, Peng W, Lu Z, Zhang B, Xue F, Guo X et al. Associations of ambient temperature with mortality for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke and the modification effects of greenness in Shandong Province, China. Sci Total Environ 2022, 851. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Zhou L, Chen K, Chen X, Jing Y, Ma Z, Bi J, Kinney PL. Heat and mortality for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke in 12 cities of Jiangsu Province, China. Sci Total Environ. 2017;601–602:271–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei J, Li Z, Li K, Dickerson RR, Pinker RT, Wang J, Liu X, Sun L, Xue W, Cribb M. Full-coverage mapping and spatiotemporal variations of ground-level ozone (O3) pollution from 2013 to 2020 across China. Remote Sens Environ 2022, 270.

- 23.Wei J, Liu S, Li Z, Liu C, Qin K, Liu X, Pinker RT, Dickerson RR, Lin J, Boersma KF, et al. Ground-Level NO2 Surveillance from Space across China for High Resolution using interpretable Spatiotemporally Weighted Artificial Intelligence. Environ Sci Technol. 2022;56(14):9988–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei J, Li Z, Lyapustin A, Sun L, Peng Y, Xue W, Su T, Cribb M. Reconstructing 1-km-resolution high-quality PM2.5 data records from 2000 to 2018 in China: spatiotemporal variations and policy implications. Remote Sens Environ 2021, 252.

- 25.Wei J, Li Z, Cribb M, Huang W, Xue W, Sun L, Guo J, Peng Y, Li J, Lyapustin A, et al. Improved 1 km resolution PM2.5 estimates across China using enhanced space–time extremely randomized trees. Atmos Chem Phys. 2020;20(6):3273–89. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Day JJ, Sandu I, Magnusson L, Rodwell MJ, Lawrence H, Bormann N, Jung T. Increased Arctic influence on the midlatitude flow during scandinavian blocking episodes. Q J R Meteorol Soc. 2019;145(725):3846–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burkart KG, Brauer M, Aravkin AY, Godwin WW, Hay SI, He J, Iannucci VC, Larson SL, Lim SS, Liu J, et al. Estimating the cause-specific relative risks of non-optimal temperature on daily mortality: a two-part modelling approach applied to the global burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2021;398(10301):685–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alduchov OA, Eskridge RE. Improved Magnus Form Approximation of Saturation Vapor pressure. J Appl Meteorol. 1996;35(4):601–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu H, Huete A. A feedback based modification of the NDVI to minimize canopy background and atmospheric noise. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 1995;33:457–65. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rhew IC, Vander Stoep A, Kearney A, Smith NL, Dunbar MD. Validation of the normalized difference Vegetation Index as a measure of Neighborhood Greenness. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21(12):946–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huete A, Didan K, Miura T, Rodriguez EP, Gao X, Ferreira LG. Overview of the radiometric and biophysical performance of the MODIS vegetation indices. Remote Sens Environ. 2002;83(1):195–213. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu L, Wang X, Guo Y, Xu J, Xue F, Liu Y. Assessment of temperature effect on childhood hand, foot and mouth disease incidence (0–5 years) and associated effect modifiers: a 17 cities study in Shandong Province, China, 2007–2012. Sci Total Environ. 2016;551–552:452–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dominici F, McDermott A, Zeger SL, Samet JM. On the use of generalized additive models in time-series studies of air pollution and health. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(3):193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gu J, Shi Y, Chen N, Wang H, Chen T. Ambient fine particulate matter and hospital admissions for ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes and transient ischemic attack in 248 Chinese cities. Sci Total Environ 2020, 715. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Li J, Huang J, Wang Y, Yin P, Wang L, Liu Y, Pan X, Zhou M, Li G. Years of life lost from ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke related to ambient nitrogen dioxide exposure: a multicity study in China. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2020, 203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Lin H, Tao J, Du Y, Liu T, Qian Z, Tian L, Di Q, Zeng W, Xiao J, Guo L, et al. Differentiating the effects of characteristics of PM pollution on mortality from ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2016;219(2):204–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Viechtbauer W. Bias and Efficiency of Meta-Analytic Variance Estimators in the Random-effects Model. 2005, 30(3):261–93.

- 38.Altman DG, Bland JM. Interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. 2003, 326(7382):219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Chen C, Zhu P, Lan L, Zhou L, Liu R, Sun Q, Ban J, Wang W, Xu D, Li T. Short-term exposures to PM2.5 and cause-specific mortality of cardiovascular health in China. Environ Res. 2018;161:188–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Viechtbauer W. Conducting Meta-analyses in R with the metafor Package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36(3):1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tian F, Qi J, Qian Z, Li H, Wang L, Wang C, Geiger SD, McMillin SE, Yin P, Lin H et al. Differentiating the effects of air pollution on daily mortality counts and years of life lost in six Chinese megacities. Sci Total Environ 2022, 827. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Verhoeven JI, Allach Y, Vaartjes ICH, Klijn CJM, de Leeuw F-E. Ambient air pollution and the risk of ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke. Lancet Planet Health. 2021;5(8):e542–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin W, Pan J, Li J, Zhou X, Liu X. Short-term exposure to Air Pollution and the incidence and mortality of stroke. The Neurologist 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Xu R, Wang Q, Wei J, Lu W, Wang R, Liu T, Wang Y, Fan Z, Li Y, Xu L, et al. Association of short-term exposure to ambient air pollution with mortality from ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2022;29(7):1994–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilker EH, Mostofsky E, Fossa A, Koutrakis P, Warren A, Charidimou A, Mittleman MA, Viswanathan A. Ambient pollutants and spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage in Greater Boston. Stroke. 2018;49(11):2764–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turin TC, Kita Y, Rumana N, Nakamura Y, Ueda K, Takashima N, Sugihara H, Morita Y, Ichikawa M, Hirose K, et al. Ambient air pollutants and acute case-fatality of cerebro-cardiovascular events: Takashima Stroke and AMI Registry, Japan (1988–2004). Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;34(2):130–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hong Y-C, Lee J-T, Kim H, Kwon H-J. Air Pollution Stroke. 2002;33(9):2165–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goodman JE, Prueitt RL, Sax SN, Pizzurro DM, Lynch HN, Zu K, Venditti FJ. Ozone exposure and systemic biomarkers: evaluation of evidence for adverse cardiovascular health impacts. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2015;45(5):412–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robertson S, Miller MR. Ambient air pollution and thrombosis. Part Fibre Toxicol 2018, 15(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Franchini M, Mannucci PM. Thrombogenicity and cardiovascular effects of ambient air pollution. Blood. 2011;118(9):2405–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Münzel T, Gori T, Al-Kindi S, Deanfield J, Lelieveld J, Daiber A, Rajagopalan S. Effects of gaseous and solid constituents of air pollution on endothelial function. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(38):3543–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rajagopalan S, Al-Kindi SG, Brook RD. Air Pollution and Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(17):2054–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hahad O, Lelieveld J, Birklein F, Lieb K, Daiber A, Münzel T. Ambient air Pollution increases the risk of Cerebrovascular and Neuropsychiatric disorders through induction of inflammation and oxidative stress. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Barath S, Langrish JP, Lundbäck M, Bosson JA, Goudie C, Newby DE, Sandström T, Mills NL, Blomberg A. Short-term exposure to ozone does not impair vascular function or affect Heart Rate Variability in Healthy Young men. Toxicol Sci. 2013;135(2):292–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu M, Huang Y, Jin Z, Ma Z, Liu X, Zhang B, Liu Y, Yu Y, Wang J, Bi J, et al. The nexus between urbanization and PM2.5 related mortality in China. Environ Pollut. 2017;227:15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang G, Liu X, Zhai S, Song G, Song H, Liang L, Kong Y, Ma R, He X. Rural-urban differences in associations between air pollution and cardiovascular hospital admissions in Guangxi, Southwest China. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29(27):40711–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Madrigano J, Jack D, Anderson GB, Bell ML, Kinney PL. Temperature, ozone, and mortality in urban and non-urban counties in the northeastern United States. Environ Health. 2015;14:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matz CJ, Stieb DM, Brion O. Urban-rural differences in daily time-activity patterns, occupational activity and housing characteristics. Environ Health 2015, 14(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Zhang X, Dupre ME, Qiu L, Zhou W, Zhao Y, Gu D. Urban-rural differences in the association between access to healthcare and health outcomes among older adults in China. BMC Geriatr 2017, 17(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Tong L, Zhang H, Yu J, He M, Xu N, Zhang J, Qian F, Feng J, Xiao H. Characteristics of surface ozone and nitrogen oxides at urban, suburban and rural sites in Ningbo, China. Atmos Res. 2017;187:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zong R, Yang X, Wen L, Xu C, Zhu Y, Chen T, Yao L, Wang L, Zhang J, Yang L, et al. Strong ozone production at a rural site in theNorth China Plain: mixed effects of urban plumesand biogenic emissions. J Environ Sci. 2018;71:261–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stafoggia M, Bellander T. Short-term effects of air pollutants on daily mortality in the Stockholm county - A spatiotemporal analysis. Environ Res. 2020;188:109854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brønnum-Hansen H, Bender AM, Andersen ZJ, Sørensen J, Bønløkke JH, Boshuizen H, Becker T, Diderichsen F, Loft S. Assessment of impact of traffic-related air pollution on morbidity and mortality in Copenhagen Municipality and the health gain of reduced exposure. Environ Int. 2018;121:973–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen R, Cai J, Meng X, Kim H, Honda Y, Guo YL, Samoli E, Yang X, Kan H. Ozone and daily mortality rate in 21 cities of East Asia: how does season modify the Association? Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(7):729–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shi W, Sun Q, Du P, Tang S, Chen C, Sun Z, Wang J, Li T, Shi X. Modification effects of temperature on the ozone–mortality relationship: a Nationwide Multicounty Study in China. Environ Sci Technol. 2020;54(5):2859–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barboza EP, Cirach M, Khomenko S, Iungman T, Mueller N, Barrera-Gómez J, Rojas-Rueda D, Kondo M, Nieuwenhuijsen M. Green space and mortality in European cities: a health impact assessment study. Lancet Planet Health. 2021;5(10):e718–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen H, Burnett RT, Bai L, Kwong JC, Crouse DL, Lavigne E, Goldberg MS, Copes R, Benmarhnia T, Ilango SD et al. Residential greenness and Cardiovascular Disease incidence, readmission, and Mortality. Environ Health Perspect 2020, 128(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Wang R, Dong P, Dong G, Xiao X, Huang J, Yang L, Yu Y, Dong G-H. Exploring the impacts of street-level greenspace on stroke and cardiovascular diseases in Chinese adults. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2022, 243. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Crouse DL, Pinault L, Balram A, Brauer M, Burnett RT, Martin RV, van Donkelaar A, Villeneuve PJ, Weichenthal S. Complex relationships between greenness, air pollution, and mortality in a population-based Canadian cohort. Environ Int. 2019;128:292–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Meo SA, Almutairi FJ, Abukhalaf AA, Usmani AM. Effect of Green Space Environment on Air pollutants PM2.5, PM10, CO, O3, and incidence and mortality of SARS-CoV-2 in highly Green and Less-Green Countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18(24). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Fares S, Conte A, Alivernini A, Chianucci F, Grotti M, Zappitelli I, Petrella F, Corona P. Testing removal of Carbon Dioxide, ozone, and Atmospheric particles by Urban Parks in Italy. Environ Sci Technol. 2020;54(23):14910–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baumgardner D, Varela S, Escobedo FJ, Chacalo A, Ochoa C. The role of a peri-urban forest on air quality improvement in the Mexico City megalopolis. Environ Pollut. 2012;163:174–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ji JS, Zhu A, Lv Y, Shi X. Interaction between residential greenness and air pollution mortality: analysis of the Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey. Lancet Planet Health. 2020;4(3):e107–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shen Y-S, Lung S-CC. Mediation pathways and effects of green structures on respiratory mortality via reducing air pollution. Sci Rep 2017, 7(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Seo S, Choi S, Kim K, Kim SM, Park SM. Association between urban green space and the risk of cardiovascular disease: a longitudinal study in seven Korean metropolitan areas. Environ Int. 2019;125:51–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Whyte M, Douwes J, Ranta A. Green space and stroke: a scoping review of the evidence. J Neurol Sci 2024, 457. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Alonso R, Vivanco MG, González-Fernández I, Bermejo V, Palomino I, Garrido JL, Elvira S, Salvador P, Artíñano B. Modelling the influence of peri-urban trees in the air quality of Madrid region (Spain). Environ Pollut. 2011;159(8–9):2138–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Harris TB, Manning WJ. Nitrogen dioxide and ozone levels in urban tree canopies. Environ Pollut. 2010;158(7):2384–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lin M, Horowitz LW, Xie Y, Paulot F, Malyshev S, Shevliakova E, Finco A, Gerosa G, Kubistin D, Pilegaard K. Vegetation feedbacks during drought exacerbate ozone air pollution extremes in Europe. Nat Clim Change. 2020;10(5):444–51. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sicard P, Agathokleous E, Araminiene V, Carrari E, Hoshika Y, De Marco A, Paoletti E. Should we see urban trees as effective solutions to reduce increasing ozone levels in cities? Environ Pollut. 2018;243:163–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yu M, Zhou W, Zhao X, Liang X, Wang Y, Tang G. Is Urban Greening an effective solution to Enhance Environmental Comfort and Improve Air Quality? Environ Sci Technol. 2022;56(9):5390–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vieira J, Matos P, Mexia T, Silva P, Lopes N, Freitas C, Correia O, Santos-Reis M, Branquinho C, Pinho P. Green spaces are not all the same for the provision of air purification and climate regulation services: the case of urban parks. Environ Res. 2018;160:306–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.James P, Banay RF, Hart JE, Laden F. A review of the Health benefits of greenness. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2015;2(2):131–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wolf KL, Lam ST, McKeen JK, Richardson GRA, van den Bosch M, Bardekjian AC. Urban Trees and Human Health: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Liu W, Zheng R, Zhang Y, Zhang W. Differences in the influence of daily behavior on health among older adults in urban and rural areas: evidence from China. Front Public Health 2023, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of Shandong Province but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the CDC of Shangdong Province.