Abstract

Social prescribing has become a global phenomenon. A Delphi study was recently conducted with 48 social prescribing experts from 26 countries to establish global agreement on the definition of social prescribing. We reflect on the use and utility of the outputs of this work, and where we go from here.

Keywords: Commentary, Global definition, Social prescribing

Introduction

Across the globe, pressures on health systems are increasing and organisations are grappling with common challenges, including the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic [1], the health impacts of climate change [2], the sharp rise in inequities [3], the consequences of an aging global population [4], and the effects of a healthcare workforce crisis that is on track to reach an estimated global shortage of 18 million health workers (20% of the workforce) by 2030 [5], to name but a few. The combined effects of these challenges have given rise to a global healthcare crisis. Time is of the essence for health systems to move beyond the biomedical model [6]. In the words of Sir Michael Marmot: “Why treat people and send them back to the conditions that made them sick?” [7, p. 1]. Indeed, health systems must shift towards a holistic approach that addresses the fundamental causes of illness and prioritises health creation [6]. There is growing interest and investment in the role of social prescribing as a tool to support this transformation of health systems, and ultimately, to achieve global goals for health and wellbeing [6, 8].

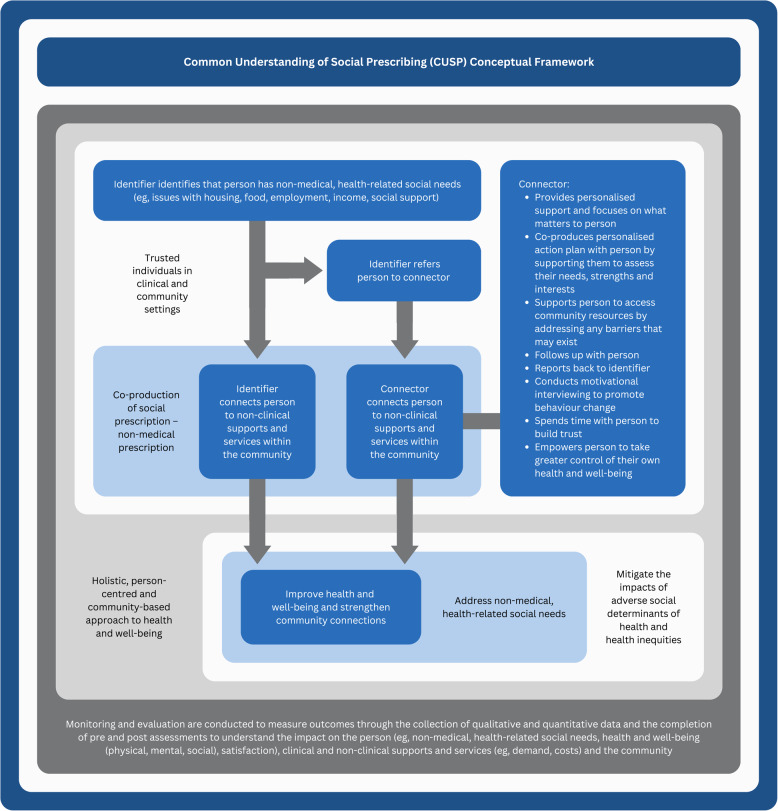

Social prescribing is “a means for trusted individuals in clinical and community settings to identify that a person has non-medical, health-related social needs and to subsequently connect them to non-clinical supports and services within the community by co-producing a social prescription – a non-medical prescription, to improve health and wellbeing and to strengthen community connections” [9, p. 9]. This holistic approach to health and wellbeing offers a way to transform health systems to address non-medical factors through individual and collective health promotion by increasing our capacity to take control of our health and wellbeing [10].

Social prescribing is an innovation that is built on a foundation of long-standing approaches to health and wellbeing, with particularly close ties to Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and doing [11]. Over the past decade, the practice of social prescribing and the usage of the term have gained widespread interest globally. Social prescribing has been integrated into practice in more than 30 countries [6, 8, 9], and this number continues to grow. This concept is increasingly being incorporated into policy, often as a tool to realize policy goals for related global healthcare trends, such as integrated care and person-centred care [8]. England was the first country in the world to introduce social prescribing into national health policy, for example, where it was seen as a core component of efforts to achieve person-centred care [6]. There is consistent evidence showing that social prescribing can improve health and wellbeing, and there is promising, albeit emerging, evidence suggesting that social prescribing can reduce healthcare demand and costs [6, 8, 12–18]. It is thought that social prescribing can also advance health equity and support community capacity and self-determination, although more evidence is needed on this [11, 19, 20]. To move the field forward, researchers, policymakers, practitioners, and community partners are coming together through local, national, and international communities of practice, such as the International Social Prescribing Collaborative.

These global developments in social prescribing have taken place against the backdrop of growing criticism surrounding its effectiveness [21–26]. Much of this criticism points to the need to understand what works, for whom, and in what circumstances, particularly as it relates to health equity in terms of ensuring that social prescribing programmes mitigate, rather than perpetuate or exacerbate, health inequities [21–23]. Criticism also points to widespread misunderstanding of what social prescribing is and misguided judgment of its value as a midstream solution [24–26]. A root cause of these issues is the historical lack of agreement on the definition of social prescribing, which has resulted in different interpretations and manifestations of this concept, both within and across countries [6, 8, 9, 15–17, 27, 28].

Why a global definition is useful

Whilst the breadth in understanding of social prescribing has allowed for diversity and flexibility of practice, the lack of consensus on the definition has been problematic. This has hindered efforts to generate robust, aggregable, and comparable evidence on social prescribing [15, 16], inhibited policy and practice development related to social prescribing [15, 27], and contributed to low public awareness of social prescribing [17]. This has also limited the advancement of social prescribing by causing confusion and disengagement of both providers and communities.

The Delphi study

The need to achieve consensus on the definition of social prescribing was the focus of a recent Delphi study, which brought together 48 social prescribing experts from 26 countries to establish global agreement on the definition [9]. Through this work, internationally accepted conceptual and operational definitions of social prescribing were established and transformed into the Common Understanding of Social Prescribing (CUSP) conceptual framework (see Fig. 1). As researchers, policymakers, practitioners, and community partners with an interest in social prescribing, we reflect on the use and utility of the outputs of this work, and where we go from here.

Fig. 1.

Common Understanding of Social Prescribing (CUSP) conceptual framework. Reproduced from Muhl C, Mulligan K, Bayoumi I, et al. Establishing internationally accepted conceptual and operational definitions of social prescribing through expert consensus: a Delphi study. BMJ Open 2023;13:e070184. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-070184, with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Use and utility

We believe the outputs of this work are helpful for several reasons. Both the definitions and framework make a novel contribution to the field by offering a global perspective on what social prescribing is, derived using robust methods. The outputs support efforts to integrate health, social, and community services through common understanding, and in doing so, better enable appropriate use of these pathways. From a practical standpoint, the definitions and framework provide useful tools to be used in social prescribing research, policy, and practice. For researchers, the outputs offer a roadmap to guide empirical inquiries; for policymakers, they provide the infrastructure that is needed to build social prescribing policies and to integrate this concept into wider health strategies; for practitioners, they offer the scaffolding that is needed to structure social prescribing programmes; and for the public, they provide the foundation that is needed to understand this concept and to experience this phenomenon in a way that is consistent yet customised. Importantly, there is intentional openness around aspects of social prescribing that are context specific, such as where it takes place (e.g., clinical setting, community setting), who is involved (e.g., clinical professional, non-clinical professional, volunteer), what labels are used (e.g., social prescriber, link worker, community connector), and what degree of support is offered (e.g., light, medium, holistic), yet there is also structure around the core components of social prescribing (e.g., identifying and connecting stages).

We also note inherent limitations of this work, with one of them being that the outputs represent the perspectives of one group of stakeholders at one point in time. Given that the value of social prescribing rests in large part on co-production with participants, it is imperative to acknowledge that there was only one person in this study who self-identified as a patient representative. This study also drew heavily from countries already engaged in social prescribing and using the label, with less representation from countries where social prescribing is taking place under different names. We note that there is a lack of representation from Africa and the Middle East, which have a rich tradition of community health initiatives. There are also deeper, relevant criticisms of generating both a global definition and framework of social prescribing. Firstly, the breadth, diversity, and flexibility of approaches are considered strengths of social prescribing programmes and attempts to concretely define or bound this concept are arguably constraining, which may not be useful. Conversely, it is also true that in order to fund, implement, and generate robust evidence a more constrained definition would be more useful and so the flexibility left in the outputs might be problematic. Despite these limitations, on balance, we feel the outputs are useful, allowing interested parties to coalesce around some shared understanding of social prescribing and offering a launch pad for further development as the field evolves.

Where we go from here

Social prescribing is being implemented as a pragmatic intervention, in which feedback and learning cycles generate improvement. A similar approach is necessary for scaling and spreading common understanding of social prescribing, with the work described offering a starting point. Ongoing input and iterative learning will lead to further refinements and deeper understanding. We encourage stakeholders across the globe to use and engage critically with the outputs of this work and to build on the outputs by working towards the development of a theoretical framework. It is through constructive criticism and incorporation of unique perspectives from different contexts that the definitions and framework will evolve over time.

If social prescribing is to be a helpful and appropriately used tool for health, social, and community services, having common understanding of this concept is necessary but not sufficient. There is a need to understand what works, for whom, and in what circumstances [29], particularly as it relates to the role of social prescribing in mitigating health inequities [19, 30].

At a time when there is growing discussion surrounding the phenomenon of lifestyle drift [31], there is much work to be done to ensure that society not only recognises the necessity of social prescribing and other midstream solutions that address non-medical, health-related social needs at the individual level, but also understands that this must be accompanied by investment in upstream solutions that address the social determinants of health at the community level [32]. This underscores the need for adequate investment in community services, shifting of leadership and power to people and communities, and strong intersectoral community partnerships. There must also be extensive policy and structural changes related to the social determinants of health. This includes a deeper restructuring of health teams and systems to address their roles in systems of inequity and oppression as well as engagement of practitioners and teams in direct, community-guided advocacy to bring about change in social policies and structures.

Conclusion

Given the rapid scaling and rollout of social prescribing globally, the work described makes a valuable contribution to the field by helping to build common understanding of this concept. In doing so, the definitions and framework support the advancement of social prescribing research, policy, and practice.

Acknowledgements

This report is independent research supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research Applied Research Collaboration South West Peninsula. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Institute for Health and Care Research or the Department of Health and Social Care.

This report is independent research supported by the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Dalla Lana School of Public Health or the University of Toronto.

Authors’ contributions

CM, KM, BCG, and KH conceived the manuscript and wrote the initial draft. CM, KM, BCG, MJP, GB, DAN, CO-F, SH, KHL, WJH, JRB, DHJS-L, SSE, MD, IW, CF, HTS, DR, Y-DC, MLH, CW, MH, DW, MB, AHJ, SA, FH, DGD, SB, TJA, DF, MLAN, ST, AL, H-KN, KGC, DH, SS, MAE, GAP, VAW, DR, LH, NT, RØN, DV, EMM, LVH, JB, AS, AB, DA-P, JMM, and KH edited and contributed to the manuscript. CM, KM, BCG, MJP, GB, DAN, CO-F, SH, KHL, WJH, JRB, DHJS-L, SSE, MD, IW, CF, HTS, DR, Y-DC, MLH, CW, MH, DW, MB, AHJ, SA, FH, DGD, SB, TJA, DF, MLAN, ST, AL, H-KN, KGC, DH, SS, MAE, GAP, VAW, DR, LH, NT, RØN, DV, EMM, LVH, JB, AS, AB, DA-P, JMM, and KH read and approved the final version.

Funding

The authors received financial support from the National Institute for Health and Care Research Applied Research Collaboration South West Peninsula and the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto for open access publishing of this article.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

CM and KM are the lead authors on the Delphi study that this commentary relates to. All other authors are involved in social prescribing research or practice in their respective locations and so have been part of, been funded, or supported by organisations that seek to promote the practice and evidence relating to social prescribing.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Caitlin Muhl, Email: caitlin.muhl@queensu.ca.

Kate Mulligan, Email: kate.mulligan@utoronto.ca.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) [online]. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (Accessed 8 Sept 2023).

- 2.World Health Organization. Climate change and health [online]. 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health (Accessed 8 Sept 2023).

- 3.Chancel L, Piketty T, Saez E, et al. World Inequality Report 2022 [online]. 2022. https://wir2022.wid.world/www-site/uploads/2023/03/D_FINAL_WIL_RIM_RAPPORT_2303.pdf (Accessed 8 Sept 2023).

- 4.World Health Organization. Ageing and health [online]. 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (Accessed 8 Sept 2023).

- 5.Britnell M. Human: Solving the Global Workforce Crisis in Healthcare. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan H, Giurca BC, Sanderson J, et al. Social prescribing around the world - a world map of global developments in social prescribing across different health system contexts [online]. 2023. https://socialprescribingacademy.org.uk/media/1yeoktid/social-prescribing-around-the-world.pdf (Accessed 8 Sept 2023).

- 7.Marmot M. The Health Gap: The Challenge of an Unequal World. New York City, USA: Bloomsbury Publishing USA; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morse DF, Sandhu S, Mulligan K, et al. Global developments in social prescribing. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7: e008524. 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-008524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muhl C, Mulligan K, Bayoumi I, et al. Establishing internationally accepted conceptual and operational definitions of social prescribing through expert consensus: a Delphi study. BMJ Open. 2023;13: e070184. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-070184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion [online]. 1986. https://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ph-sp/docs/charter-chartre/pdf/charter.pdf (Accessed 8 Sept 2023).

- 11.Vaillancourt A, Barnstaple R, Robitaille N, et al. Nature prescribing: emerging insights about reconciliation-based and culturally inclusive approaches from a tricultural community health centre. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2024;44:284–7. 10.24095/hpcdp.44.6.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polley M, Chatterjee H, Asthana S, et al. Measuring outcomes for individuals receiving support through social prescribing [online]. 2022. https://socialprescribingacademy.org.uk/media/kp3lhrhv/evidence-review-measuring-impact-and-outcomes-for-social-prescribing.pdf (Accessed 8 Sept 2023).

- 13.Kimberlee R, Bertotti M, Dayson C, et al. The economic impact of social prescribing [online]. 2022. https://socialprescribingacademy.org.uk/media/carfrp2e/evidence-review-economic-impact.pdf (Accessed 8 Sept 2023).

- 14.Napierala H, Krüger K, Kuschick D, et al. Social prescribing: systematic review of the effectiveness of psychosocial community referral interventions in primary care. Int J Integr Care. 2022;22:11. 10.5334/ijic.6472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zurynski Y, Vedovi A, Smith K. Social prescribing: a rapid literature review to inform primary care policy in Australia [online]. 2020. https://chf.org.au/sites/default/files/sprapidreview_3-2-20_final.pdf (Accessed 8 Sept 2023).

- 16.Costa A, Sousa CJ, Seabra PRC, et al. Effectiveness of social prescribing programs in the primary health-care context: a systematic literature review. Sustainability. 2021;13:2731. 10.3390/su13052731. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lejac B. A desk review of social prescribing: from origins to opportunities [online]. 2021. https://www.rsecovidcommission.org.uk/a-desk-review-of-social-prescribing-from-origins-to-opportunities/ (Accessed 8 Sept 2023).

- 18.World Health Organization. A toolkit on how to implement social prescribing [online]. 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789290619765 (Accessed 8 Sept 2023).

- 19.Khan K, Tierney S, Owen G. Applying an equity lens to social prescribing. J Public Health 2024;fdae105. 10.1093/pubmed/fdae105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Bhatti S, Rayner J, Pinto AD, et al. Using self-determination theory to understand the social prescribing process: a qualitative study. BJGP Open 2021;5:BJGPO.2020.0153. 10.3399/BJGPO.2020.0153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Gibson K, Pollard TM, Moffatt S. Social prescribing and classed inequality: a journey of upward health mobility? Soc Sci Med. 2021;280: 114037. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibson K, Moffatt S, Pollard TM. ‘He called me out of the blue’: an ethnographic exploration of contrasting temporalities in a social prescribing intervention. Sociol Health Illn. 2022;44:1149–66. 10.1111/1467-9566.13482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pollard T, Gibson K, Griffith B, et al. Implementation and impact of a social prescribing intervention: an ethnographic exploration. Br J Gen Pract. 2023;73:e789–97. 10.3399/BJGP.2022.0638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moscrop A. Social prescribing is no remedy for health inequalities. BMJ 2023;p715. 10.1136/bmj.p715 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Dabbs C. Social prescribing: community power and the community paradigm. Clin Integr Care. 2024;25: 100222. 10.1016/j.intcar.2024.100222. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poole R, Huxley P. Social prescribing: an inadequate response to the degradation of social care in mental health. BJPsych Bull. 2024;48:30–3. 10.1192/bjb.2023.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Islam MM. Social prescribing - an effort to apply a common knowledge: impelling forces and challenges. Front Public Health. 2020;8: 515469. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.515469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malby B, Boyle D, Wildman J, et al. The asset based health inquiry: how best to develop social prescribing [online]. 2019. https://www.lsbu.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/251190/lsbu_asset-based_health_inquiry.pdf (Accessed 8 Sept 2023).

- 29.Husk K, Blockley K, Lovell R, et al. What approaches to social prescribing work, for whom, and in what circumstances? A realist review. Health Soc Care Community. 2020;28:309–24. 10.1111/hsc.12839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan K, Tierney S. The role of social prescribing in addressing health inequalities. In: Bertotti M, editor. Social Prescribing Policy, Research and Practice: Transforming Systems and Communities for Improved Health and Wellbeing. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2024. p. 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woodall J. Lifestyle drift is killing health promotion [online]. 2023. https://www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/opinion-and-blog/lifestyle-drift-killing-health-promotion (Accessed 2 Sept 2024).

- 32.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Investing in Interventions That Address Non-Medical, Health-Related Social Needs: Proceedings of a Workshop [online]. 2019. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/25544/investing-in-interventions-that-address-non-medical-health-related-social-needs (Accessed 2 Sept 2024). [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.