Abstract

Background

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic, relapsing condition wherein biologics have improved disease prognosis but introduced elevated infection susceptibility. Vedolizumab (VDZ) demonstrates unique safety advantages; however, a comprehensive systematic comparison regarding the risk of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) between vedolizumab and alternative medications remains absent.

Method

Medline, Embase, Cochrane, and clinicaltrials.gov registry were comprehensively searched. Pooled estimates of CDI proportion, incidence, pooled risk ratio between ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), vedolizumab and other medications were calculated. Data synthesis was completed in R using the package “meta”.

Results

Of the 338 studies initially identified, 30 met the inclusion/exclusion criteria. For CDI risk, the pooled proportion was 0.013 (95% CI 0.010–0.017), as well as the pooled proportion of serious CDI was 0.004 (95% CI 0.002–0.008). The comparative pooled risk ratios revealed: UC versus CD at 2.25 (95% CI 1.73–2.92), vedolizumab versus anti-TNF agents at 0.15 (95% CI 0.04–0.63) for UC and 1.29 (95% CI 0.41–4.04) for CD.

Conclusion

The overall CDI risk in IBD patients exposed to vedolizumab was estimated to be 0.013. An increased risk of CDI was noted in UC patients receiving vedolizumab compared to those with CD. Vedolizumab potentially offers an advantage over anti-TNF agents for UC regarding CDI risk, but not for CD.

Trial registration

The study was registered on the PROSPERO registry (CRD42023465986).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12876-024-03460-z.

Keywords: Vedolizumab, Clostridioides difficile infection, Inflammatory bowel disease, Systematic review

Background

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), encompassing ulcerative colitis (UC), and Crohn’s disease (CD), are a group of disorders characterized by chronic, relapsing, and remitting, or progressive inflammation along the gastrointestinal tract. These progressive diseases can lead to structural bowel damage, loss of function, disability and increase the potential for hospitalization and surgery. The advent of biologics has markedly improved the prognosis for individuals suffering from moderate to severe IBD and has been prominently recommended in clinical guidelines [1, 2]. However, the immunosuppressive nature of biologics also gives rise to certain safety concerns, particularly regarding malignancies and the risk of infections [3]. Vedolizumab is a monoclonal antibody binding to the α4β7 integrin that is expressed on activated gut-homing T lymphocytes and blocks the interaction of the α4β7 integrin and the mucosal addressing cell adhesion molecule 1 (MAdCAM-1) [4], and is regarded as a gut-specific immunosuppressive agent, which offering unique safety advantages compared to other biologics [3]. However, based on safety data from phase III trials, vedolizumab posed an increased risk of gastrointestinal infections compared to the placebo group [5]. And the risk of severe gastrointestinal infections associated with vedolizumab is similar to that of tumor necrosis factor antagonists (anti-TNF) [6]. However, the comparative aspects of vedolizumab concerning gastrointestinal opportunistic infections remain unclear in comparison to other drugs.

Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) is the leading cause for gastrointestinal infections and opportunistic infection in patients with IBD [7]. Studies showed that the risk of CDI was eight times higher in IBD than in non-IBD patients, and the lifetime infection rate was found around 10% [8]. Some studies investigated whether IBD medications increase the risk of CDI, found that patients on maintenance immunomodulators (6-mercaptopurine, azathioprine, or methotrexate) and corticosteroids had an increased risk of CDI, whereas those on anti-TNF did not [9, 10]. Based on the existing evidence, only one systematic review has summarized the risk of CDI in UC patients exposed to vedolizumab [11]. This review reported only the pooled proportion of CDI cases, suggesting that vedolizumab does not increase the CDI risk in UC patients. However, due to the lack of a control group, the applicability of this conclusion remains uncertain. Additionally, the review did not analyze the risk of severe CDI, compare the CDI risk between different medications, or include data on Crohn’s disease patients. Further studies are needed to provide a comprehensive understanding of CDI risk in IBD patients treated with vedolizumab.

Therefore, our study aimed to compile existing evidence and conduct a meta-analysis on the incidence of CDI in patients with IBD receiving vedolizumab, while also making comparisons with other pharmaceutical interventions.

Methods

The methods of our analysis and inclusion criteria were based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations [12, 13]. The study was registered on the PROSPERO registry (CRD42023465986).

Study inclusion and exclusion

Studies fulfilling the criteria listed in the sections of “Design of eligible studies”, “Eligible participants”, “Types of Interventions” and reporting at least one of interested outcomes listed in the section of “Primary and secondary outcomes” were included, without limitation in sample size, follow-up period, and reporting forms (full-text or abstract). Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were listed below.

Type of eligible studies

Eligible studies included retrospective or prospective cohort studies. Given that our primary research objective is to reflect the CDI risk in IBD patients exposed to VDZ in real-world settings, the results from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with strict inclusion and exclusion criteria were excluded [14, 15]. Besides, we excluded cross-sectional studies, meta-analyses, reviews, case reports, editorials, preclinical or otherwise irrelevant studies. Studies with duplicated cohorts were excluded.

Eligible participants

We included adults, adolescent, or both with IBD (including ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, IBD unclassified or any of the three) based on clinical, histological and endoscopic criteria in this review. We excluded the study in which vedolizumab was used specifically for the treatment of refractory pouchitis or prevention/treatment of postoperative recurrence of IBD. Besides, patients after liver transplantation were also excluded as concomitant anti-rejection drugs were used [16].

Types of interventions

We included studies using vedolizumab as medication for inflammatory bowel disease at any dose, frequency and route of administration (subcutaneous [17] and intravenous). studies where VDZ was used as part of a combination therapy with more than one biologic (such as dual biological therapy) were excluded.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome in our systematic review was the incidence of Clostridioides difficile infection. The secondary outcomes were the incidence of serious Clostridioides difficile infection (white blood cells > 15,000 or serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL [18] or requiring hospitalization [19–21]), risk ratio of Clostridioides difficile infection in patients treated with vedolizumab and other drugs. We excluded study with infection data in ambiguous descriptions, such as clostridial infection, because it contains infections other than Clostridioides difficile infection [5].

Search methods for identification of studies

Potentially relevant studies were searched using Medline via Ovid, Embase via Embase.com, the Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials (CENTRAL) and clinicaltrials.gov registry from database inception up to September 2023. Detailed literature search strategy with each free text and MeSH terms used in Medline is shown in the supplementary Table e1. Hand search of the bibliographies of relevant review and systematic review articles were also conducted.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (CW and LYH) independently assessed the eligibility of the citations using the title and abstract, and full texts of potentially eligible studies were used to judge the final eligibility. Any disagreement between reviewers was resolved by discussion with a methodologist (ZYL) and the senior author (ZY).

Data extraction and management

Data were extracted into an Excel extraction form by one investigator and double checked by another:

Characteristics of the study: title, first author, publication year, country, study design, reporting forms, sample size.

Population characteristics: IBD subtype (UC and CD), Montreal type, disease activity, age, disease duration, smoking status, prior exposure to anti-TNF agents, abdominal surgery history.

Intervention characteristics: concomitant medications (corticosteroids, other immunomodulators).

Follow-up: endpoint of follow-up (CDI or non-CDI), length of follow‐up.

Comparisons: anti-TNF agents, 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), corticoid.

Outcomes: definition or examination of CDI, number of CDI and serious CDI.

We made the largest use of all the available materials of the relevant studies, including but not limited to the publication of the main results and the study design, unpublished report, information about study registry, and online appendices. If the key information was not reported in the above sources, study investigators were contacted through email to get the relevant data.

Assessment of risk of bias of eligible studies

Two review authors (CW and LYH) independently evaluated the methodological quality of the included studies. For double-arm studies, the assessment was conducted using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale(NOS) [22]. For all studies including single-arm studies, a modified tool derived from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) instrument [23, 24] (Supplementary Table 2) was used. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion with a methodologist (ZYL) and a senior investigator (ZY). Supplementary Tables 3 and 4 showed the detailed criteria to assess the risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We analyzed the data using R (version 4.2.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2022, https://www.R-proje ct.org/). Random-effects model was used to combine the estimates as we anticipated significant heterogeneity in the studies. Summary estimates are presented as risk ratio for double-arm studies and incidence for single-arm studies, both with 95% confidence intervals [CIs].

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity by calculating the τ2 estimation, I2 statistics and Chi-square test. We considered that I2 values greater than 50% indicated substantial heterogeneity. For the Chi2 test, a two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Meta regression and subgroup analysis were used to explore the source of heterogeneity.

Meta regression

We performed univariate meta regression with covariate of post-marketing, sample size, age, UC proportion, disease duration, E3 proportion, TNF-exposure proportion, Concomitant corticoid proportion, Concomitant immune inhibitors proportion, Smoking proportion, Abdominal surgery history proportion, Follow-up time, Study Design and the use of vedolizumab (VDZ) as first-, or second-, or third-line therapy.

Subgroup analysis

We performed the following subgroup analyses on our primary outcome, where there was at least one study within each subgroup: [i] type of disease[UC patients versus CD patients], [ii] sample size [less than 100, between 100 and 999,vs. larger than 1000], [iii] post-marketing data only vs. other cohort studies, [iv] age subgroup [< 65 years vs. ≥ 65 years], [v] proportion of previous TNF antagonist exposure[< 0.6 vs. ≥ 0.6], [vi] proportion of concomitant corticosteroids[<0.5 vs. ≥ 0.5], [vii] disease duration[<10 years vs. ≥ 10 years], [viii] E3 proportion for UC[< 0.5 vs. ≥ 0.5], [ix] proportion of concomitant immunomodulator[<0.4 vs. ≥ 0.4], [x] proportion of current smokers[<0.1 vs. ≥ 0.1], [xi] proportion of previous abdominal surgery[<0.25 vs. ≥ 0.25], [xii] study design[Prospective Cohort, Retrospective Cohort vs. RCT], [xiii] the use of vedolizumab (VDZ) as first-, second-, or third-line therapy [we categorized studies where the proportion of patients with prior biologic use was less than 50% as the first-line therapy group, and those with more than 50% as the second/third-line therapy group]. In addition to the above subgroup analyses, we also performed subgroup analyses for UC and CD when comparing the CDI risk of vedolizumab with anti-TNF agents.

Sensitivity analysis

Different transformation methods for the proportions in the data combination were conducted to check if the main findings were robust. Besides, sensitivity analysis of studies with full-text only and NOS score more than 3 were also implemented if possible.

Assessment of reporting bias

For pooled estimates from single-arm studies, there is no planned assessment for reporting bias, since the hypothesis behind the commonly applied methods for detecting reporting bias may not be satisfied in the meta-analysis for incidence rate or proportion. For pooled risk ratio from double-arm studies, funnel plot and egger’s test would be implemented, provided that at least 10 studies were included.

Assessment of the certainty of the evidence

The certainty of the evidence was evaluated by GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) using GRADEpro GDT (https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/#projects).

Results

Description of studies

We implemented a comprehensive literature search on 25 September 2023 and identified 338 citations. After exclusion of duplications, there were 305 studies remaining for screening. We excluded 241 studies after review of the titles and abstracts. Full texts were retrieved for the remaining 78 studies, of which 30 studies [17–21, 25–49] met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram showing the flow and final inclusion of studies

The included studies consisted of 26 retrospective cohort studies and 4 prospective cohort studies (Table 1). Of these cohort studies, 15 studies were based on single-armed cohort design. And 21 were published study reports and 9 were abstracts. 12 studies provided separate data for UC or CD, while the other 18 studies only provided combined data for IBD. Additionally, one of the included studies utilized subcutaneous administration of vedolizumab, while the other studies all employed intravenous infusion. Most studies focused on the treatment efficacy of vedolizumab and only reported the number of CDI as the secondary outcome without detailed information of the examination methods for CDI and severity. Only 3 studies set the follow-up endpoint as the occurrence of CDI and reported CDI as the primary outcome. Besides, ten studies made comparison of vedolizumab and other drugs including anti-TNF, 5-ASA and corticoid. The average follow-up time was unknown because 11 studies did not report the detailed data, for the reported ones, the average follow-up time was 1.48 years.

Table 1.

Basic information of included studies

| Author (year) | Study design | Country | Participants | Sample size* | Age, mean | Follow-up (years) | CDI | Serious CDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wiken (2023) | Prospective Cohort | Norway | IBD | 108 | 40 | > 0.5 | √ | NA |

| Reddy (2020) | Retrospective Cohort | Australia and UK | UC | 303 | 35 | NA | √ | NA |

| Perin (2019). | Retrospective Cohort | Brazil | IBD | 90 | 42 | 0.9 | √ | NA |

| O’Regan (2015) | Retrospective Cohort | North America | IBD | 40 | 34 | 2.8 | √ | NA |

| Narula (2018) | Retrospective Cohort | North America | UC | 321 | 38 | 0.8 | √ | NA |

| Morrison (2019) | Retrospective Cohort | UK | IBD | 53 | 43 | NA | √ | NA |

| Meserve (2019) | Retrospective Cohort | NA | IBD | 1087 | 37 | 0.8 | √ | NA |

| Macaluso (2020) | Retrospective Cohort | Italy | IBD | 543 | 66 | 1.1 | √ | NA |

| Leung (2020) | Retrospective Cohort | North America | IBD | 17 | 71 | 2.4 | √ | NA |

| Lawlor (2018) | Retrospective Cohort | NA | IBD | 9 | NA | NA | √ | NA |

| Kopylov (2017) | Prospective Cohort | Israel | IBD | 204 | 40 | 0.3 | √ | NA |

| Kochar (2018) | Retrospective Cohort | USA | IBD | 639 | 41 | 0.5 | √ | NA |

| Kochar (2019) | Retrospective Cohort | USA | IBD | 456 | 43 | 0.6 | √ | NA |

| Hupé (2020) | Retrospective Cohort | France | UC | 71 | 43 | 1.6 | √ | NA |

| Garay (2017) | Retrospective Cohort | NA | IBD | 10 | 48 | NA | √ | NA |

| Gan (2019) | Retrospective Cohort | Singapore | IBD | 53 | 30 | 1.2 | √ | NA |

| Dalal (2023) | Retrospective Cohort | USA | UC | 195 | 48 | 1.8 | √ | √ |

| Conrad (2016) | Prospective Cohort | USA | IBD | 21 | 17 | 0.4 | √ | NA |

| Cohen (2020) | Retrospective Cohort | USA | IBD | 32,752 | NA | 6.4 | √ | √ |

| Cohen (2020) | Retrospective Cohort | Multi-countries | IBD | 284 | 50 | 0.7 | √ | NA |

| Chaudrey (2016) | Retrospective Cohort | Israel and UK | IBD | 326 | 38 | 0.7 | √ | NA |

| Chaparro (2018) | Retrospective Cohort | NA | IBD | 521 | 42 | 0.8 | √ | NA |

| Buisson (2022) | Retrospective Cohort | Spain | UC | 178 | NA | NA | √ | NA |

| Bohm (2020) | Retrospective Cohort | USA | CD | 659 | 40 | > 1 | √ | √ |

| Baumgart (2016) | Retrospective Cohort | Germany | IBD | 212 | 39 | NA | √ | NA |

| Amiot (2017) | Prospective Cohort | France | IBD | 294 | 38 | NA | √ | NA |

| Alshahrani (2023) | Retrospective Cohort | Canada | IBD | 228 | 35 | > 2 | √ | NA |

| Adar (2019) | Retrospective Cohort | USA | IBD | 103 | 68 | NA | √ | NA |

| Ng, S. C (2018) | Retrospective Cohort | Multi-countries | IBD | 2243 | NA | 2.4 | √ | √ |

| Khan (2021) | Retrospective Cohort | USA | IBD | 213 | 72 | 1.9 | √ | √ |

Abbreviations: IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; UC, Ulcerative Colitis; CD, Crohn’s Disease; VDZ, Vedolizumab; TNF, anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor; ASA, 5- Aminosalicylic Acid; NA, Not Available

*: Number of patients in treatment of vedolizumab

Risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias in eligible studies was evaluated by modified AHRQ for all studies (including single-arm cohort studies) and by NOS for double-arm studies. The results were listed in Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Table 4 respectively.

Risk of C. difficile infection in IBD patients in treatment of vedolizumab

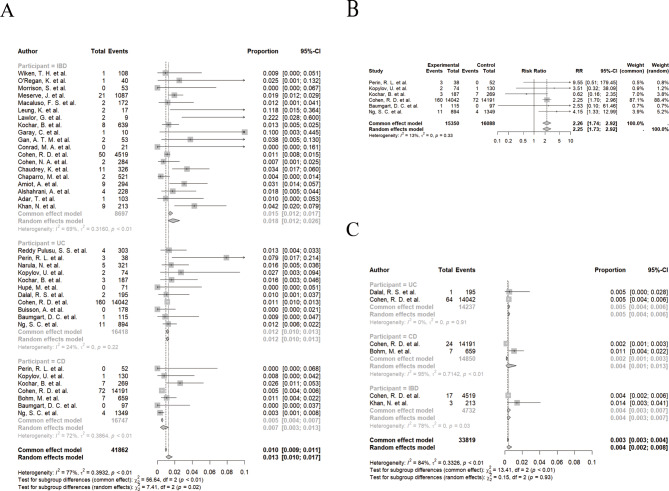

A total of 41,862 patients were included, with 410 IBD patients reporting of C. difficile infection, the pooled proportion was 0.013 (95% CI 0.010 to 0.017; I2 = 77%, Fig. 2A; low certainty evidence). For 16,418 UC patients, the pooled proportion of CDI was 0.012 (95% CI 0.010 to 0.013; I2 = 24%, Fig. 2A; low certainty evidence); for 16,747 CD patients, the pooled proportion was 0.007 (95% CI 0.003 to 0.013; I2 = 72%, Fig. 2A; low certainty evidence). There was a significant subgroup difference in the risk of CDI when using VDZ among different IBD subtypes (P = 0.02, Fig. 2A). In addition, for six cohort studies reporting the CDI risk of both UC and CD, the pooled risk ratio was 2.25 (UC vs. CD, 95% CI 1.73 to 2.92, I2 = 13%, Fig. 2B; low certainty evidence).

Fig. 2.

Risk of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients in treatment of vedolizumab. A Pooled proportion of CDI for all included studies; B Pooled proportion of serious CDI; C Pooled rate of CDI for studies with follow-up endpoint of CDI; D Pooled rate of serious CDI

Four studies with 33,819 patients reported the risk of serious C. difficile infection, the pooled proportion was 0.004 (95% CI 0.002 to 0.008; I2 = 84%, Fig. 2C; low certainty evidence). There is no statistically significant difference between the IBD subgroups (P = 0.93, Fig. 2C).

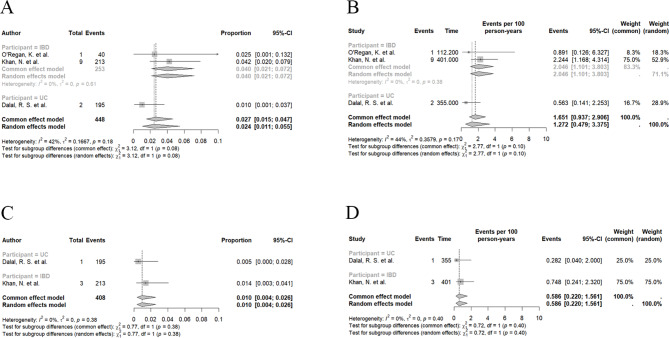

Across three studies where the follow-up endpoint was the occurrence of C. difficile infection, the pooled proportion and incidence for IBD were 0.024 (95% CI 0.011 to 0.055; I2 = 42%, Fig. 3A; low certainty evidence) and 1.27 per 100 person-years (95% CI 0.48 to 3.37; I2 = 44%, Fig. 3B; low certainty evidence), respectively. For UC, the pooled proportion and incidence were 0.010 (95% CI 0.001 to 0.037; Fig. 3A; low certainty evidence) and 0.56 per 100 person-years (95% CI 0.14 to 2.25; Fig. 3B; low certainty evidence). The pooled proportion and incidence rate for serious CDI risk, based on two studies, were 0.010 (95% CI 0.004 to 0.026; I2 = 0%, Fig. 3C; low certainty evidence) and 0.59 per 100 person-years (95% CI 0.22 to 1.56; I2 = 0%, Fig. 3D; low certainty evidence), respectively. For UC, the pooled proportion and incidence were 0.005 (95% CI 0.000 to 0.028; Fig. 3C; low certainty evidence) and 0.28 per 100 person-years (95% CI 0.14 to 2.25; Fig. 3D; low certainty evidence).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) risk between ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). A Pooled proportion of CDI between UC and CD according to subgroup analysis, P = 0.10. B Risk Ratio of CDI between UC and CD from 6 eligible cohort studies

Investigation of heterogeneity

Given the considerable heterogeneity (I² = 77%) in the pooled CDI risk among IBD patients treated with vedolizumab, meta-regressions (Supplementary Table 5) and subgroup analyses (Supplementary Table 6) were conducted for all included studies. Besides IBD subtypes (as mentioned above), no other available variables showed significant differences.

Sensitivity analysis

The pooled values of CDI risk in IBD patients using different transformation methods are shown in Supplementary Table 7; no significant differences were discovered among these results.

Comparison of CDI risk in IBD patients in treatment of vedolizumab and other drugs

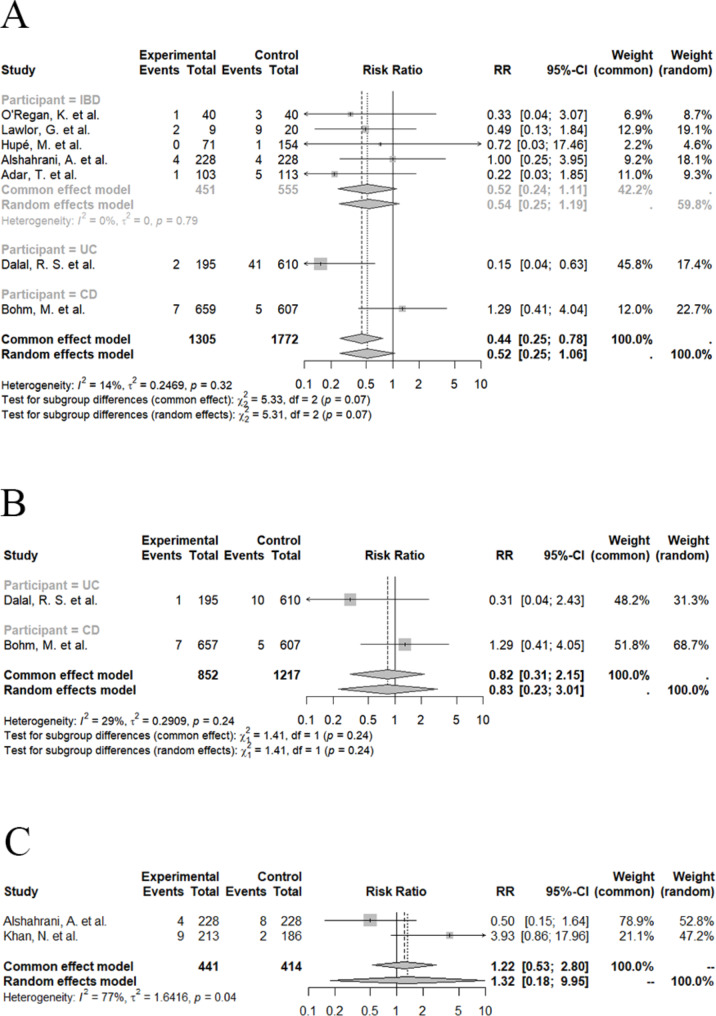

Vedolizumab versus anti-TNF agents

Seven studies compared the risk of C. difficile infection of patients in treatment of vedolizumab and anti-TNF agents, the pooled risk ratio was 0.52 (VDZ vs. anti-TNF, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.06, I2 = 14%, Fig. 4A; low certainty evidence). In detail, 610 UC patients showed a pooled risk ratio of 0.15 (VDZ vs. anti-TNF, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.63, Fig. 4A; low certainty evidence). In contrast, 607 CD patients exhibited a pooled risk ratio of 1.29 (VDZ vs. anti-TNF, 95% CI 0.41 to 4.04, Fig. 4A; low certainty evidence). However, there was no significant difference in pooled risk ratio of CDI between VDZ and anti-TNF among different subtypes of IBD (P = 0.07, Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) risk in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients in treatment of vedolizumab and other drugs. A Pooled risk ratio of CDI risk between vedolizumab and anti-TNF from 8 eligible studies; B Pooled risk ratio of serious CDI risk between vedolizumab and anti-TNF from 2 eligible studies; C Pooled risk ratio of CDI risk between vedolizumab and 5-ASA from 2 eligible studies

Sensitivity analysis excluding studies reported as abstracts showed a pooled value of 0.53 (VDZ vs. anti-TNF, 95% CI 0.20 to 1.43, I2 = 41%; low certainty evidence). Among these studies, two also provided the data of serious CDI, the pooled risk ratio was 0.83 (VDZ vs. anti-TNF, 95% CI 0.23 to 3.01, I2 = 29%, Fig. 4B; low certainty evidence). Sensitivity analysis by excluding studies of high risk of bias according to NOS showed no significant difference (RR = 0.57, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.94, I2 = 63%; low certainty evidence).

Vedolizumab versus 5-ASA

Two studies compared vedolizumab with 5-ASA, the pooled risk ratio was 1.32 (VDZ vs. 5-ASA, 95% CI 0.18 to 9.95, I2 = 77%, Fig. 4C; low certainty evidence) without detailed information on IBD subtypes.

Vedolizumab versus corticoid

Only one study reported the CDI risk of both vedolizumab and corticoid, the calculated risk ratio was 1.38 (VDZ vs. Corticoid, 95% CI 0.33 to 8.09, P = 0.76; low certainty evidence).

However, we found no studies that compared the CDI risk of vedolizumab with immunomodulators, ustekinumab and small molecules.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Our systematic review focused on the CDI risk in IBD patients receiving vedolizumab. With an average follow-up of 1.48 years, we found pooled CDI proportions of 0.013 for all IBD patients, 0.012 for UC, and 0.007 for CD. The pooled incidence was 1.27 per 100 person-years for all IBD patients and 0.56 per 100 person-years for UC, but detailed data for CD were unavailable. For serious CDI, the pooled proportion was 0.004, and the pooled incidence was 0.59 per 100 person-years. Ananthakrishnan et al. reported an annual incidence range of 0.014 to 0.020 for serious CDI (hospitalized cases) in patients with IBD during the period spanning from 1998 to 2004 [50]. Besides, Singh et al. reported the incidence of CDI in a population-based cohort of patients with IBD (2005–2014) and found the mean incidence of CDI was approximately 1.5 per 100 person-years in the first year after IBD diagnosis [51]. Since these national data only encompassed patients up to 2014, and vedolizumab received FDA approval for IBD treatment in 2014, these data primarily portray the CDI risk among IBD patients receiving treatment regimens rather than vedolizumab. Based on our findings and an indirect comparison with previous literatures, vedolizumab, compared to other treatments, does not appear to present additional CDI risk and might even serve as a protective factor against severe CDI infections.

Additionally, meta-analysis of safety data from six RCTs involving vedolizumab showed that the exposure-adjusted incidence rate of CDI among patients treated with vedolizumab was 0.7 per 100 person-years, in contrast to 0.0 per 100 person-years among those treated with placebo [5]. The generalizability of this assertion is brought into question due to the significantly lower incidence of CDI in the placebo group than in the broader population of IBD patients [50, 51]. Besides, we observed a disparity in follow-up durations between the vedolizumab intervention group and the placebo control group aggregated in this meta-analysis. The average follow-up period for the vedolizumab intervention group was approximately one year, whereas the control group had only six months of follow-up. This discrepancy might have led to an underestimation of the CDI risk within the control group, even after adjusting for the exposure time in calculating the incidence rate.

A significant difference in CDI risk between UC and CD exposed to VDZ was shown by both subgroup analysis of pooled proportion (P = 0.02) and pooled risk ratio (RR = 2.25). This finding aligns with previous studies on IBD patients treated with other medications [52, 53]. UC patients exhibit higher CDI rates than CD patients, primarily due to the higher prevalence of colonic involvement in UC [54]. Notably, our study provides the first quantitative depiction of this issue in VDZ-exposed IBD patients.

Furthermore, we conducted a meta-analysis comparing CDI risk between vedolizumab and other treatments. Our results showed no significant difference in CDI risk for IBD patients using vedolizumab compared to those using TNF inhibitors, 5-ASA, or steroids. However, in the UC subgroup, vedolizumab was associated with a lower CDI risk compared to TNF inhibitors (RR = 0.15, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.63). The difference between UC and CD (RR = 1.29) was close to statistical significance (P = 0.07). To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis on this topic, with no similar systematic review available for comparison.

The limited number of studies and small sample sizes distinguishing between UC and CD may explain the lack of statistical significance. And differences in the efficacy of VDZ for UC and CD may help explain the potential variations observed in our data. Current network meta-analyses show no significant difference in efficacy between VDZ and anti-TNF for UC [55]. With similar mucosal healing rates, varying levels of immunosuppression between these drugs might account for differences in CDI risk. For CD, VDZ is less effective than anti-TNF [56], leading to poorer mucosal healing and potentially increasing CDI risk. These hypotheses require further research for confirmation.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Our study represents the inaugural meta-analysis investigating the incidence of CDI in patients with IBD treated with vedolizumab. The literature search was aimed to encompass studies globally, irrespective of languages, reporting formats, or publication dates. Hence, it was conceived to be comprehensive, portraying the available evidence. We consider our meta-analysis results to be generalizable to individuals with IBD exposed to vedolizumab.

Among the included studies, a subset of IBD patients concurrently used steroids or immunosuppressants during vedolizumab treatment, which could potentially confound the study outcomes, although neither meta-regression nor subgroup analyses indicated significant effects on heterogeneity. The majority of studies considered CDI as a secondary outcome, with only one paper [18] detailing the diagnostic criteria for CDI, possibly leading to detection biases. There is presently a limited number of comparative studies evaluating the risk of Clostridioides difficile infection between vedolizumab and 5-ASA, alongside steroids, potentially resulting in less precise estimations of outcomes. Additionally, the grades for all synthesized estimates are presently rated as low.

Implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research

This is the most comprehensive meta-analysis to date on this topic. Our research results indicate the necessity for attention to the risk of CDI among IBD patients treated with vedolizumab. Based on existing evidence, VDZ showed a potential advantage over anti-TNF for UC in terms of CDI risk, but not for CD.

This review has highlighted areas for further research. Prospective studies and studies controlling for potential confounding factors such as disease severity and concomitant medications are required to generate higher-quality evidence. Furthermore, considering the independent risk posed by colonic involvement in CDI [57], there is speculation that despite exposure to identical medications, the risk of CDI might differ between active-phase patients and those in remission especially for UC. Nevertheless, there remains a paucity of comprehensive studies investigating this hypothesis, and further studies specifically addressing this topic are required.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the risk of CDI during vedolizumab therapy in IBD patients requires attention. UC patients on vedolizumab exhibited a higher CDI risk compared to CD patients. Vedolizumab potentially offers an advantage over anti-TNF for UC regarding CDI risk, but not for CD. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to show any superiority or inferiority of vedolizumab compared to other treatments, such as corticosteroids and 5-ASA, in terms of CDI risk.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- 5-ASA

5-aminosalicylic acid

- AHRQ

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- anti-TNF

Tumor necrosis factor antagonists

- CD

Crohn’s disease

- CDI

Clostridioides difficile infection

- CI

Confidence interval

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- NOS

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and meta-analyses

- RCTs

Randomized controlled trials

- RR

Risk ratio

- UC

Ulcerative Colitis

- VDZ

Vedolizumab

Author contributions

WC and YZ conceptualized and designed the study. WC and YHL were responsible for data acquisition and interpretation. WC, YHL, YLZ, HZ, CYC, SYZ, YHZ, HYZ, and YZ collaborated on drafting and revising the manuscript. WC and YLZ conducted the statistical analysis. YZ contributed to the critical revision and finalization of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC2507300) and Beijing Friendship Hospital (YYZZ202215) .

Data availability

Please contact author for data requests.

Declarations

Human Ethics and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Wei Chen and Yuhang Liu share co-first authorship.

References

- 1.Feuerstein JD, Isaacs KL, Schneider Y, Siddique SM, Falck-Ytter Y, Singh S. AGA Clinical Practice guidelines on the management of moderate to severe Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(5):1450–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torres J, Bonovas S, Doherty G, Kucharzik T, Gisbert JP, Raine T, Adamina M, Armuzzi A, Bachmann O, Bager P, et al. ECCO Guidelines on therapeutics in Crohn’s Disease: Medical Treatment. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2020;14(1):4–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Click B, Regueiro M. A practical guide to the Safety and Monitoring of New IBD therapies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(5):831–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, Hanauer S, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Van Assche G, Axler J, Kim HJ, Danese S, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(8):699–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colombel J-F, Sands BE, Rutgeerts P, Sandborn W, Danese S, D’Haens G, Panaccione R, Loftus EV, Sankoh S, Fox I, et al. The safety of vedolizumab for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2017;66(5):839–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirchgesner J, Desai RJ, Beaugerie L, Schneeweiss S, Kim SC. Risk of serious infections with Vedolizumab Versus Tumor necrosis factor antagonists in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(2):314–e324316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kucharzik T, Ellul P, Greuter T, Rahier JF, Verstockt B, Abreu C, Albuquerque A, Allocca M, Esteve M, Farraye FA, et al. ECCO Guidelines on the Prevention, diagnosis, and management of infections in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15(6):879–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Razik R, Rumman A, Bahreini Z, McGeer A, Nguyen GC. Recurrence of Clostridium difficile infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: the RECIDIVISM Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(8):1141–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Issa M, Vijayapal A, Graham MB, Beaulieu DB, Otterson MF, Lundeen S, Skaros S, Weber LR, Komorowski RA, Knox JF, et al. Impact of Clostridium difficile on inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(3):345–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bossuyt P, Verhaegen J, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P, Vermeire S. Increasing incidence of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2009;3(1):4–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alghamdi M, Alyousfi D, Mukhtar MS, Mosli M. Association between Vedolizumab and risk of clostridium difficile infection in patients with ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Saudi J Gastroenterol 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg 2021, 88. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ha C, Ullman TA, Siegel CA, Kornbluth A. Patients enrolled in randomized controlled trials do not represent the inflammatory bowel disease patient population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(9):1002–7. quiz e1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson C, Barnes EL, Zhang X, Long MD. Trends and characteristics of clinical trials participation for inflammatory bowel disease in the United States: a Report from IBD partners. Crohns Colitis. 2020;360(2):otaa023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spadaccini M, Aghemo A, Caprioli F, Lleo A, Invernizzi F, Danese S, Donato MF. Safety of vedolizumab in liver transplant recipients: a systematic review. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2019;7(7):875–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiken TH, Høivik ML, Buer L, Warren DJ, Bolstad N, Moum BA, Anisdahl K, Småstuen MC, Medhus AW. Switching from intravenous to subcutaneous vedolizumab maintenance treatment in patients with inflammatory bowel disease followed by therapeutic drug monitoring. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2023;58(8):863–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dalal RS, Mitri J, Goodrick H, Allegretti JR. Risk of gastrointestinal infections after initiating Vedolizumab and Anti-TNF agents for Ulcerative Colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023;57(7):714–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen RD, Bhayat F, Blake A, Travis S. The Safety Profile of Vedolizumab in Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease: 4 years of global post-marketing data. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2020;14(2):192–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adar T, Faleck D, Sasidharan S, Cushing K, Borren NZ, Nalagatla N, Ungaro R, Sy W, Owen SC, Patel A, et al. Comparative safety and effectiveness of tumor necrosis factor α antagonists and vedolizumab in elderly IBD patients: a multicentre study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(7):873–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan N, Pernes T, Weiss A, Trivedi C, Patel M, Xie D, Yang YX. Incidence of infections and Malignancy among Elderly Male patients with IBD exposed to Vedolizumab, Prednisone, and 5-ASA medications: a Nationwide Retrospective Cohort Study. Adv Therapy. 2021;38(5):2586–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell PT. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analys analysis http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.Accessed 01/09/2023.

- 23.Viswanathan M, Ansari MT, Berkman ND, Chang S, Hartling L, McPheeters M, Santaguida PL, Shamliyan T, Singh K, Tsertsvadze A, et al. : AHRQ methods for Effective Health Care:assessing the risk of Bias of Individual Studies in systematic reviews of Health Care interventions. Methods Guide for Effectiveness and comparative effectiveness reviews. edn. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen W, Zhang YL, Zhao Y, Yang AM, Qian JM, Wu D. Endoscopic resection for non-polypoid dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2021;35(4):1534–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hupé M, Rivière P, Nancey S, Roblin X, Altwegg R, Filippi J, Fumery M, Bouguen G, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Bourreille A, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of vedolizumab and infliximab in ulcerative colitis after failure of a first subcutaneous anti-TNF agent: a multicentre cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51(9):852–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bohm M, Xu R, Zhang Y, Varma S, Fischer M, Kochhar G, Boland B, Singh S, Hirten R, Ungaro R, et al. Comparative safety and effectiveness of vedolizumab to tumour necrosis factor antagonist therapy for Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52(4):669–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kochar B, Jiang Y, Winn A, Barnes EL, Martin CF, Long MD, Kappelman MD. The early experience with vedolizumab in the United States. Crohn’s Colitis 360 2019;1(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Macaluso FS, Fries W, Renna S, Viola A, Muscianisi M, Cappello M, Guida L, Siringo S, Camilleri S, Garufi S, et al. Effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab in biologically naïve patients: a real-world multi-centre study. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2020;8(9):1045–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kopylov U, Ron Y, Avni-Biron I, Koslowsky B, Waterman M, Daher S, Ungar B, Yanai H, Maharshak N, Ben-Bassat O, et al. Efficacy and safety of Vedolizumab for induction of Remission in Inflammatory Bowel Disease-the Israeli Real-World experience. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(3):404–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ng SC, Hilmi IN, Blake A, Bhayat F, Adsul S, Khan QR, Wu DC. Low frequency of opportunistic infections in patients receiving vedolizumab in clinical trials and post-marketing setting. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(11):2431–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kochar B, Winn A, Barnes EL, Long MD, Kappelman M. The National Experience with Vedolizumab. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(6):S-67-S-68. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amiot A, Serrero M, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Filippi J, Pariente B, Roblin X, Buisson A, Stefanescu C, Trang-Poisson C, Altwegg R, et al. One-year effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective multicentre cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46(3):310–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gan ATM, Chan WPW, Ling KL, Hartono LJ, Ong DE, Gowans M, Lin H, Lim WC, Tan MTK, Ong JPL, et al. Real-world data on the efficacy and safety of vedolizumab therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a retrospective nation-wide cohort study in Singapore. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2019;13:S434–5. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buisson A, Nachury M, Guilmoteau T, Altwegg R, Treton X, Fumery M, Serrero M, Leclerc E, Caillo L, Pereira B, et al. Real-world multicenter comparison of short and long-term effectiveness and safety between Tofacitinib and Vedolizumab in patients with Ulcerative Colitis after failure to at least one Anti-TNF Agent. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2022;10:364–5. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meserve J, Aniwan S, Koliani-Pace JL, Shashi P, Weiss A, Faleck D, Winters A, Chablaney S, Kochhar G, Boland BS, et al. Retrospective analysis of Safety of Vedolizumab in patients with inflammatory Bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(8):1533–e15401532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Regan K, Kroeker K, Halloran BP, Dieleman LA, Peterson A, Haynes K, Fedorak RN. A retrospective cohort study of rates of clostridium difficile infection in moderate-to-severe inflammatory bowel disease patients treated with vedolizumab vs. infliximab at a Canadian tertiary hospital. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(4):S235. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lawlor G, Bohm M, Advani R, Tricomi B, Gutta A, Phipps M, Adlakha N, Rosen MH, Malter L, Hudesman D, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Biologic therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Disease in patients with primary sclerosing Cholangitis: an IBD Remedy Study. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(6):S–843. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morrison S, Edwards G, Foster R, Daley A, Lawrence O, Goodsall T. The safety and efficacy of vedolizumab for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the Hunter New England region. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:157. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chaparro M, Garre A, Ricart E, Iborra M, Mesonero F, Vera I, Riestra S, García-Sánchez V, Luisa De Castro M, Martin-Cardona A, et al. Short and long-term effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab in inflammatory bowel disease: results from the ENEIDA registry. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48(8):839–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alshahrani A, Alzahrani DMMA, Narula N. Vedolizumab does not increase risk of clostridium difficile infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease using vedolizumab: a retrospective cohort study. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2022;16:i326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reddy Pulusu SS, Srinivasan A, Krishnaprasad K, Cheng D, Begun J, Keung C, Van Langenberg D, Thin L, Mogilevski T, de Cruz P, et al. Vedolizumab for ulcerative colitis: real world outcomes from a multicenter observational cohort of Australia and Oxford. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26(30):4428–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Narula N, Peerani F, Meserve J, Kochhar G, Chaudrey K, Hartke J, Chilukuri P, Koliani-Pace J, Winters A, Katta L, et al. Vedolizumab for Ulcerative Colitis: treatment outcomes from the VICTORY Consortium. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(9):1345–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perin RL, Damião AOMC, Flores C, Ludvig JC, Magro DO, Miranda EF, de Moraes AC, Nones RB, Teixeira FV, Zeroncio M, et al. Vedolizumab in the management of inflammatory bowel diseases: a Brazilian observational multicentric study. Arq Gastroenterol. 2019;56(3):312–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baumgart DC, Bokemeyer B, Drabik A, Stallmach A, Schreiber S, Atreya R, Bachmann O, Busse K, Bläker M, Börner N, et al. Vedolizumab induction therapy for inflammatory bowel disease in clinical practice - A nationwide consecutive German cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43(10):1090–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen NA, Plevris N, Kopylov U, Grinman A, Ungar B, Yanai H, Leibovitzh H, Isakov NF, Hirsch A, Ritter E, et al. Vedolizumab is effective and safe in elderly inflammatory bowel disease patients: a binational, multicenter, retrospective cohort study. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2020;8(9):1076–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leung K, Jackson CS, Hammami MB. Vedolizumab is safe in veteran patients with inflammatory bowel Disease over Age 65: Retrospective Cohort. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):S–680. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Conrad MA, Stein RE, Maxwell EC, Albenberg L, Baldassano RN, Dawany N, Grossman AB, Mamula P, Piccoli DA, Kelsen JR. Vedolizumab Therapy in severe Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(10):2425–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garay C, Oro M, Senra L, Gómez M, Fernández A, De Ilarduya EM, Lizama N, Gómez A, Martínez JJ, Valero M. Vedolizumab treatment for inflammatory bowel disease: clinical practice. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2017;24:A188–9. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chaudrey K, Whitehead D, Dulai PS, Peerani F, Narula N, Hudesman D, Shmidt E, Lukin DJ, Swaminath A, Nguyen N, et al. Safety of vedolizumab in inflammatory bowel disease in a multi-center real world consortium. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(4):S974. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ananthakrishnan AN, McGinley EL, Binion DG. Excess hospitalisation burden associated with Clostridium difficile in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2008;57(2):205–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh H, Nugent Z, Yu BN, Lix LM, Targownik LE, Bernstein CN. Higher incidence of Clostridium difficile infection among individuals with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(2):430–e438432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barber GE, Hendler S, Okafor P, Limsui D, Limketkai BN. Rising incidence of intestinal infections in inflammatory bowel disease: a nationwide analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(8):1849–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsai L, Nguyen NH, Ma C, Prokop LJ, Sandborn WJ, Singh S. Systematic review and Meta-analysis: risk of hospitalization in patients with Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease in Population-based Cohort studies. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67(6):2451–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rodemann JF, Dubberke ER, Reske KA, Seo DH, Stone CD. Incidence of Clostridium difficile infection in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(3):339–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lasa JS, Olivera PA, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Efficacy and safety of biologics and small molecule drugs for patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(2):161–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barberio B, Gracie DJ, Black CJ, Ford AC. Efficacy of biological therapies and small molecules in induction and maintenance of remission in luminal Crohn’s disease: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gut. 2023;72(2):264–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Balram B, Battat R, Al-Khoury A, D’Aoust J, Afif W, Bitton A, Lakatos PL, Bessissow T. Risk factors Associated with Clostridium difficile infection in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13(1):27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Please contact author for data requests.