Abstract

Background

In mouse models of atherosclerosis, knockout of the PLA2G2A gene has been shown to reduce the volume of atherosclerotic plaques. Clinical trials have demonstrated the potential of using the sPLA2 inhibitor Varespladib in combination with statins to reduce lipid levels. However, this approach has not yielded the expected results in reducing the risk of cardiovascular events. Therefore, it is necessary to further investigate the mechanisms of PLA2G2A.

Methods

Single-cell transcriptome data from two sets of carotid plaques, combined with clinical patient information. were used to describe the expression characteristics of PLA2G2A in carotid plaques at different stages. In order to explore the mechanisms of PLA2G2A, we conducted enrichment analysis, cell–cell communication analysis and single-cell regulatory network inference and clustering analyses. We validated the above findings at the cellular level.

Results

Our findings indicate that PLA2G2A is primarily expressed in vascular fibroblasts and shows significant cell interactions with macrophages in the early-stage, especially in complement and inflammation-related pathways. We also found that serum sPLA2 levels have stronger diagnostic value in patients with mild carotid artery stenosis. Subsequent comparisons of single-cell transcriptomic data from early and late-stage carotid artery plaques corroborated these findings and predicted transcription factors that might regulate the progression of early carotid atherosclerosis (CA) and the expression of PLA2G2A.

Conclusions

Our study discovered and validated that PLA2G2A is highly expressed by vascular fibroblasts and promotes plaque progression through the activation of macrophage complement and coagulation cascade pathways in the early-stage of CA.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12967-024-05679-6.

Keywords: Carotid atherosclerosis, Single-cell transcriptome, Fibroblast, Complement and coagulation cascade pathway, Secretory phospholipase A2

Background

Carotid atherosclerosis (CA) is one of the pathological causes of cerebrovascular diseases [1]. According to a global epidemiological analysis, the prevalence of carotid plaques in the population aged 30–79 years had reached 21.15% by 2020 [2]. This condition presents numerous social issues and imposes a significant economic burden. The progression of CA includes the initiation stage, progression stage, and complication stage, each involving distinct pathophysiological processes such as endothelial injury, lipid infiltration, inflammation, foam cell formation, calcification, and plaque rupture [1]. Therefore, identifying and effectively intervening in CA during the progression stage, rather than waiting until complications arise, are crucial for prevention. This poses challenges in discovering specific biomarkers and therapeutic targets for CA during its progression stage.

Secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2), belonging to Group II of the PLA2 superfamily and encoded by the PLA2G2A, can be detected in both serum and arterial wall [3]. Studies have demonstrated that knocking out PLA2G2A in the context of atherosclerosis can reduce the volume of atherosclerotic lesions [4]. Serum sPLA2 plays a primary role in the modification of low-density lipoproteins, facilitating their retention in the subendothelial space and promoting the formation of foam cells [5]. In arterial tissues, it hydrolyzes the sn-2 ester bond of glycerophospholipids in lipoproteins and cell membranes, releasing lysophospholipids and non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) [6], which have direct pro-inflammatory effects. These products exert a wide range of cellular effects, including cytotoxicity, thereby promoting the progression of atherosclerosis [7]. Additionally, research has shown that sPLA2 can enhance the expression of MCP-1 in ox-LDL-induced human aortic smooth muscle cells through the PI3K/Akt pathway, thereby promoting inflammation and advancing atherosclerosis [8]. However, clinical studies on the use of the sPLA2 inhibitor Varespladib, combined with statins for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases and its impact on periprocedural myonecrosis following percutaneous coronary intervention, have all ended in failure [9]. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the role and mechanisms of PLA2G2A in the progression of CA.

Fibroblasts, as the main component of the arterial adventitia, have been confirmed to play a significant role in the progression of atherosclerosis. In addition to providing structural support to blood vessels, fibroblasts can secrete extracellular matrix and matrix metalloproteinases, thereby influencing the progression of atherosclerosis through adventitial remodeling [10]. Furthermore, fibroblasts can respond to various cytokine stimuli, and studies have shown that fibroblasts can secrete cytokines and interact with different cell types in the intima and media [11]. However, the precise mechanisms of these interactions remain unclear.

In this study, we recruited local residents undergoing health check-ups in the physical examination department. We assessed the degree of CA in these participants via ultrasound and measured their serum sPLA2 levels to evaluate the diagnostic value of serum sPLA2 for patients with different degrees of carotid stenosis. Additionally, we performed a comprehensive analysis of plaque samples from different stages of CA using single-cell transcriptomics, revealing the role and mechanism of PLA2G2A in the progression of CA. Finally, we validated the role of sPLA2 at the mRNA and protein levels, confirming the mechanism by which PLA2G2A contributes to the progression of carotid atherosclerosis.

Methods

Study population

Our study enrolled 369 subjects (232 males and 137 females, aged over 45 years) in the department of physical examination at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University from December 2018 to December 2020. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) complete baseline characteristics, including age, gender, clinical presentation, blood tests and drug history; (2) suffering from carotid stenosis, which was evaluated by ultrasound; (3) no treatment for carotid stenosis for 3 months prior to the study, including drugs and surgery; (4) no malignancy and other serious chronic diseases. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) good quality of carotid artery, which was evaluated by ultrasound; (2) receiving any treatment for carotid stenosis within 3 months prior, like lipid-lowering drugs or carotid endarterectomy; (3) suffering from malignancy or other serious chronic diseases.

Data collection

The medical records of the subjects were collected by our group, like age, gender, hypertension (defined as a history of hypertension and newly diagnosed hypertension), diabetes (including a history of diabetes mellitus and newly diagnosed diabetes), smoking (defined as continuous or cumulative smoking ≥ 6 months or at least 6 months every day) and alcohol drinking (defined as a daily drinking amount ≥ 180 ml). Peripheral fasting blood samples were tested within 1 h after collection, including triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), sPLA2 and Lipoprotein-associated phospholipases A2 (Lp-PLA2) (Cloud-Clone Corporation, catalog numbers SED827Hu, SEA867Hu). All subjects were given ultrasound examination of their carotid. According to the criteria of North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial [12], we divided the subjects into three groups: the mild-stenosis group (< 50% stenosis), the moderate-stenosis group (ranging from 50 to 69% stenosis), and the severe-stenosis group (ranging from 70 to 100% stenosis). All data were collected, and the inter-rater reliability between two investigators was assessed in some cases. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (2018-KY-0067-001).

Single cell data processing

The single-cell dataset for carotid plaque used in this study partly originates from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), with the accession number GSE159677. It includes calcified atherosclerotic core (AC) plaques from carotid calcification in three patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy and the matched proximal adjacent (PA) sections of their carotids. Another portion of the data was derived from samples collected from patients with mild and severe carotid stenosis at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University after carotid plaque endarterectomy. These samples were subsequently subjected to single-cell transcriptomic sequencing, with the following specific processing steps.

The tissues were dissociated using Tissue Dissociation Reagent A (Seekone K01301-30) from SeekGene as per the instructions. Cell counts and viability were estimated using fluorescence Cell Analyzer (Countstar® Rigel S2) with AO/PI reagent after removal of erythrocytes (Solarbio R1010) and then debris and dead cells removal was performed (Miltenyi 130-109-398/130-090-101). Finally fresh cells were washed twice in RPMI1640 and then resuspended at 1×106 cells per ml in 1× PBS and 0.04% bovine serum albumin. Single-cell RNA-Seq libraries were prepared using the SeekOne® Digital Droplet Single Cell 3ʹ library preparation kit (SeekGene Catalog No.K00202). The indexed sequencing libraries were purified using SPRI beads, quantified by quantitative PCR (KAPA Biosystems KK4824), and then sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 with PE150 read length or DNBSEQ-T7 platform with a PE150 read length.

The raw sequencing data were processed by Fastp firstly to trim primer sequence and low-quality bases. And then we used SeekOne®Tools to process sequence data and align them to the human GRCh38 reference genome in order to obtain a gene expression matrix. We used R package Seurat (version 4.3.1) to filter low-quality cells. Cells with a number of detected genes < 200 or > 4000 and a mitochondrial gene expression ratio exceeding 10%, were omitted. Then the R package Doubletfinder was used to remove possible doublets.

SCT was used to standardize, normalize, and remove batch effects from all single-cell data. Afterwards, the data were integrated using 3000 highly variable genes, and principal component analysis was performed. The top 30 principal components were selected for clustering. The clustering results were displayed at different resolutions using the R package clustree, setting the final resolution to 0.2. The characteristic genes for each cluster were identified using the FindAllMarkers function. Cell types were determined by referencing the automated annotations from the R package SingleR and the CellMarker website (http://bio-bigdata.hrbmu.edu.cn/CellMarker/index.html). Finally, The results were visualized using Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP).

Differentially expressed genes between groups were identified using the FindMarkers function, followed by enrichment analysis using the R package ClusterProfiler (version 4.9.0.002) for Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses, as well as gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). Cell–cell communication analysis was performed using the R package CellChat (version 1.4.0) with the mouse database, including the “Secreted Signaling”, “Cell–cell Contact”, and “ECM-Receptor” modules. The upregulated and downregulated signaling ligand-receptor pairs between two conditions were identified by comparing communication probabilities. A weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was conducted with the R package hdWGCNA (version 0.2.19) to identify modules of highly co-expressed genes. Key transcription factors were predicted using single-cell regulatory network inference and clustering (SCENIC, version 1.3.1) analysis.

Real-time PCR

RNA was extracted using the FastPure Cell/Tissue Total RNA Isolation Kit V2 (Vazyme, RC112-01), and reverse transcription was performed with HiScript III All-in-one RT SuperMix Perfect for qPCR (Vazyme, R333-01). RT-qPCR was performed using SGExcel FastSYBR Mixture (Sangon Biotech, B532955). Relative expression was calculated by the 2−△△Ct method, with normalization to ACTIN expression. The primer information is as follows: C3-F: AGTGGCCATTGCTGGGTATG, C3-R: GGATGTGGCCTCTACGTTGT; C3ar1-F: GTTACAGCCTCATCGTCTTCAG, C3ar1-R: CAATAGCAGGACTCCGACAAG; C1qa-F: CTGGCAAACCTGGCAATGTG, C1qa-R: CAAGCGTCATTGGGTTCTGC.

Western blot

Proteins were extracted from treated RAW264.7 cells using RIPA lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA method. The protein samples were then mixed with SDS-PAGE loading buffer and denatured by heating at 95 °C for 5 min. Equal amounts of protein samples were loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel and separated by electrophoresis. After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane, which was blocked with 5% non-fat milk at room temperature for 1 h. The membrane was then incubated with the primary antibody solution overnight at 4 °C. The following day, the membrane was washed five times with TBST buffer, 5 min each time. The membrane was then incubated with the secondary antibody solution at room temperature for 1 h. After incubation, the membrane was washed again five times with TBST buffer, 5 min each time. Finally, the protein bands were detected using an ECL detection kit, and images were captured using a chemiluminescent imaging system. The expression levels of the target proteins were quantified using ImageJ software.

Dil-ox-LDL uptake assay

Dil-ox-LDL (Yiyuan Biotech, Guangzhou, China) was used to track the uptake of ox-LDL. After stimulating RAW264.7 cells with different concentrations of PLA2G2A protein (MCE, Cat. No.: HY-P74628) for 24 h, 20 μg/mL of Dil-Ox-LDL was added. The cells were incubated at 37 °C for 6 h. Subsequently, the medium containing Dil-Ox-LDL was removed, and the cells were washed multiple times with probe-free medium. After DAPI staining of the nuclei, measurements were taken under a fluorescence microscope at 488/565 nm.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis of clinical data was performed using SPSS V.21.0 software. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by independent Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test as appropriate. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and were analyzed using χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the association between factors and carotid stenosis. The area under the receiver operating curve (AUC) was estimated to evaluate the ability of the two candidates in predicting the risk of different stages of CA. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

sPLA2 shows a higher predictive value for mild carotid stenosis

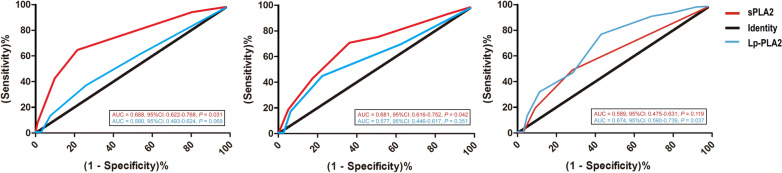

In a cohort of 369 cases with carotid stenosis (Table 1), 127 had mild stenosis, 84 had moderate stenosis, and the remaining 158 patients presented with severe stenosis[12]. The gender differences among various degrees of carotid stenosis were not statistically significant (P = 0.201). Older participants were more frequently observed in the severe stenosis group (P = 0.028), compared to those with mild and moderate stenosis. Hypertension and hyperglycemia were identified as risk factors for severe stenosis (P = 0.011 and P = 0.009, respectively). Among lipid indicators, TG (P = 0.020), TC (P = 0.041), and LDL-C (P = 0.032) were risk factors, but HDL-C levels were lower in the severe stenosis group (P = 0.015). Univariate logistic regression analysis showed that serum sPLA2 and Lp-PLA2 levels were associated with carotid stenosis (P = 0.034 and 0.028). However, only serum sPLA2 levels reached a statistical significant difference between mild-stenosis and moderate stenosis groups (P < 0.001). We further confirmed the ability of serum sPLA2 to differentiate early-stage CA through ROC analysis (Fig. 1). We found serum sPLA2 levels predicted the presence of mild stenosis more sensitively and specifically (AUC = 0.688, 95%CI 0.622–0.768, P = 0.031). In other words, it was a sensitive and specific marker for early CA.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants with different degrees of carotid stenosis

| Variable | Degrees of carotid stenosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild stenosis | Moderate stenosis | Severe stenosis | P value | |

| N | 127 | 84 | 158 | |

| Age (years) | 56.50 ± 11.12 | 63.34 ± 8.69 | 69.85 ± 13.70 | 0.028 |

| Male [n (%)] | 70 (55.1) | 52 (61.9) | 110 (69.6) | 0.201 |

| Hypertension [n (%)] | 43 (33.9) | 55 (65.5) | 121 (76.6) | 0.011 |

| Diabetes [n (%)] | 21 (16.5) | 34 (40.5) | 62 (39.2) | 0.009 |

| Smoking [n (%)] | 35 (27.6) | 18 (21.4) | 37 (23.4) | 0.218 |

| Alcohol drinking [n (%)] | 13 (10.2) | 10 (11.9) | 21 (13.3) | 0.363 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.47 ± 0.60 | 1.57 ± 0.43 | 2.41 ± 0.65 | 0.020 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 3.51 ± 1.91 | 4.89 ± 1.17 | 5.16 ± 0.69 | 0.041 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.51 ± 0.37 | 4.47 ± 0.96 | 4.90 ± 0.55 | 0.032 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.13 ± 0.74 | 0.95 ± 0.15 | 0.69 ± 0.23 | 0.015 |

| sPLA2 (ng/mL)a | 1.62 ± 0.32 | 3.79 ± 0.47 | 4.05 ± 0.69 | 0.034 |

| Lp-PLA2 (ng/mL)a | 125.82 ± 29.59 | 140.48 ± 43.82 | 182.37 ± 59.96 | 0.028 |

Subjects who received any treatment of carotid stenosis within 3 months prior were excluded

N: number; TG: Triglyceride; TC: total cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; sPLA2: secretory Phospholipases A2; Lp-PLA2: lipoprotein-associated Phospholipases A2

aThere were statistical differences in sPLA2 and Lp-PLA2 levels between the following subgroups: (1) sPLA2: mild stenosis group vs. moderate stenosis group, P < 0.001; moderate stenosis group vs. severe stenosis group, P = 0.317; mild stenosis group vs. severe stenosis group, P < 0.001. (2) Lp-PLA2: mild stenosis group vs. moderate stenosis group, P = 0.069; moderate stenosis group vs. severe stenosis group, P = 0.013; mild stenosis group vs. severe stenosis group, P < 0.001

Fig. 1.

ROC curves of serum sPLA2 and Lp-PLA2 in patients with different degrees of carotid artery stenosis. The left, middle, and right panels represent mild, moderate, and severe stenosis, respectively. ROC: Receiver Operating Curve; sPLA2: Secretory phospholipases A2; Lp-PLA2: Lipoprotein-associated phospholipases A2; AUC: Area under the Receiver Operating Curve; CI: Confidence interval

PLA2G2A is highly expressed in the fibroblasts of carotid artery plaques

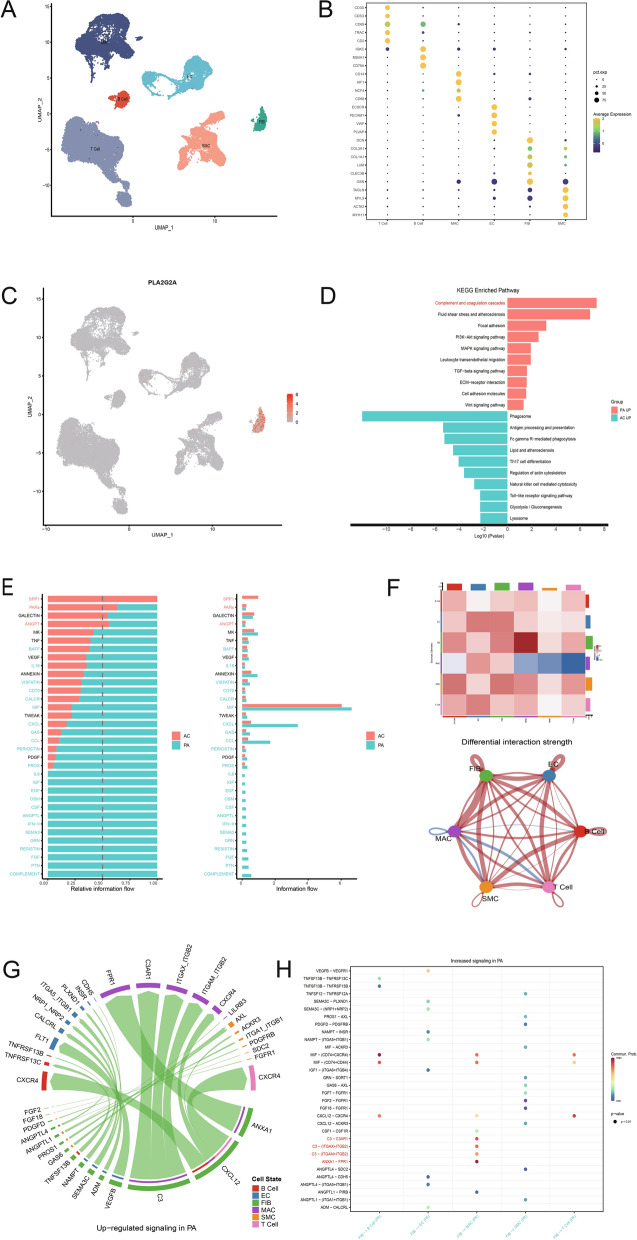

To examine the expression characteristics of PLA2G2A in CA, we analyzed the single-cell data of atherosclerotic core (AC) plaques and patient-matched proximal adjacent (PA) portions of carotid artery tissue, GSE159677. Typically, the PA region of a plaque is considered to represent the progression stage of atherosclerosis, while the AC region, which mainly contains calcified plaques and fibrous caps, is a high-risk area for plaque rupture and represents the complication stage of atherosclerosis, namely the late stage. After quality control and filtering, dimensional reduction, unsupervised clustering, marker gene comparison, and annotation were performed on 40,521 cells. This resulted in the identification of six cell types (Fig. 2A and Fig. S1A, B), including endothelial cells (TIE1, CLDN5, CDH5, VWF, PECAM1, ECSCR, PLVAP), smooth muscle cells (MYH11, ACTA2, CALD1, MYL9, TAGLN), fibroblasts (GSN, CLEC3B, LUM, COL1A1, COL3A1, DCN), macrophages (CD14, AIF1, NCF4, CD68), T cells (CD3D, CD3G, CD69, TRAC, CD2), and B cells (IGKC, MS4A1, CD79A) (Fig. 2B). In the feature plots, these marker genes displayed consistent expression characteristics (Fig. S1C). Notably, PLA2G2A was primarily expressed in fibroblasts (Fig. 2C). Enrichment analysis based on differential genes between the two groups revealed distinct biological features between the PA and AC groups. The PA group predominantly exhibited enrichment in complement and coagulation cascades, fluid shear stress and atherosclerosis, focal adhesion, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, MAPK signaling pathway, leukocyte transendothelial migration, TGF-β signaling pathway, ECM-receptor interaction, cell adhesion molecules, and the Wnt signaling pathway. The AC group primarily showed enrichment in phagosome, antigen processing and presentation, Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis, lipid and atherosclerosis, Th17 cell differentiation, regulation of the actin cytoskeleton, natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity, Toll-like receptor signaling pathway, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and the lysosome pathway (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

PLA2G2A is highly expressed in fibroblasts of carotid plaque, and the PA and AC regions have different cell–cell communication features. A UMAP plot displaying the cell types of the carotid plaque single-cell dataset GSE159677 after annotation. B Dot plot displaying the marker genes used for cell type annotation. C Visualization of PLA2G2A expression features in the UMAP plot. D Barplot showing the KEGG pathways enriched by up-regulated genes in PA (Green) and AC (Red) regions, respectively. E Bar chart ranking important signaling pathways based on differences in overall information flow in the network inferred between AC and PA regions. F Heatmap and circle plot showing differential interaction strengths among different cell populations across the two datasets, with red (or blue) representing increased (or decreased) signaling in the PA dataset compared to the AC dataset. G-H Chord diagram (G) and bubble plot (H) visualizing the identified ligand-receptor signaling pairs that are upregulated in PA compared to AC. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection; AC: atherosclerotic core; PA: patient-matched proximal adjacent; KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

Fibroblasts in the PA demonstrate stronger intercellular communication with other cells

By comparing cell–cell communications between the PA and AC groups, the results showed significant differences in the pathways involved in cell–cell communication within each group. In the PA region, in addition to enhanced interactions in many common pathways (MIF, GAS, CCL, CXCL), there were also many unique pathways, such as IL6, IGF, CSF, and COMPLEMENT, which were inactive in the late-stage AC region. In contrast, the AC region predominantly featured cell interactions in pathways related to osteopontin (SPP1), protease-activated receptors (PARs), and angiopoietin (ANGPT), which are associated with cytoskeletal proteins and angiogenesis (Fig. 2E). Additionally, compared to the late-stage AC region, the progression-stage PA area exhibited stronger cell interactions, especially between fibroblasts and macrophages (Fig. 2F). The chord diagram in Fig. 2G and the bubble chart in Fig. 2H showed that the main signaling pathways involved in the interaction between fibroblasts and macrophages in the PA region included ANXA1−FPR1, C3−C3AR1, and ITGAX + ITGB2. These pathways are associated with inflammation, macrophage activation, and activation of the complement system.

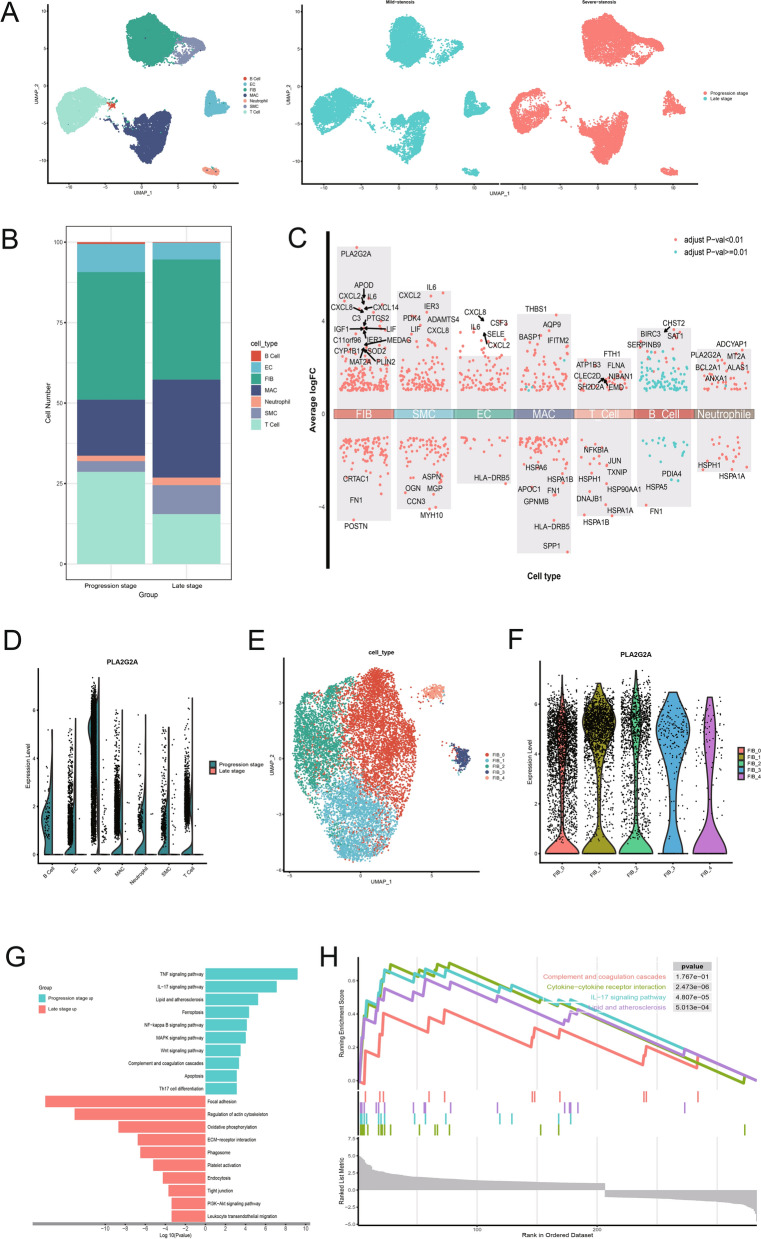

PLA2G2A is highly expressed in progression-stage carotid atherosclerotic plaques

To validate the aforementioned findings, we collected carotid atherosclerotic plaques from patients with mild stenosis and severe stenosis for single-cell transcriptome sequencing analysis, representing the progression and late stages of CA, respectively. Similar to the analysis of GSE159677, we performed batch effect removal, quality control, dimensionality reduction, clustering, and annotation of the data (Fig. 3A). Compared to progression-stage plaques, the proportion of macrophages significantly increased in late-stage plaques, while the proportions of endothelial cells and T cells markedly decreased, with a slight reduction in fibroblasts (Fig. 3B). Multiple volcano plots revealed differentially expressed genes in each cell type across the different stages of atherosclerosis, among which PLA2G2A was significantly highly expressed in fibroblasts in progression-stage carotid atherosclerotic plaques (Fig. 3C). In our data, fibroblasts within mild stenosis carotid artery plaques were also the predominant cell type expressing PLA2G2A (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Single-cell transcriptomic landscape of progression- and late-stage carotid atherosclerotic plaques. A UMAP plot illustrating the results of cell annotation following single-cell data clustering (left) and the cell distribution between the progression and late stages (right). B Stacked bar plot depicting the variation in cell proportions between the two groups. C Dot plots highlighting differentially expressed genes between cell types in the progression- and late-stage carotid atherosclerotic plaques. D Split violin plot showing the expression of PLA2G2A in different cell types in the two groups. E UMAP plot showing the clustering of fibroblasts into 5 subclusters. F Violin plot showing the expression of PLA2G2A across the five different fibroblast subclusters. G Bidirectional bar graph displaying KEGG pathway enrichment for genes upregulated in both the progression- and late-stage carotid atherosclerotic plaques. H Enrichment plots from GSEA displaying the top three normalized enrichment score-ranked pathways and the complement and coagulation cascades pathway. The colors of the dashed lines represent different pathways. GSEA: Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

We further subdivided fibroblasts into 5 distinct subclusters. Notably, the expression of PLA2G2A did not show significant differences across these subclusters (Fig. 3E, F). We conducted KEGG and GSEA enrichment analyses on the differentially expressed genes in fibroblasts between the progression and late stages ((Fig. 3G, H). The results indicated that the fibroblasts from progression-stage plaques were predominantly enriched in pathways typically associated with the progression of arterial atherosclerosis, such as the TNF signaling pathway, IL-17 signaling pathway, and lipid and atherosclerosis pathway. Interestingly, we also discovered significant enrichment of genes in the complement and coagulation cascades in fibroblasts from the progression-stage plaques (NES = 1.322), suggesting their key role in early-stage atherosclerosis.

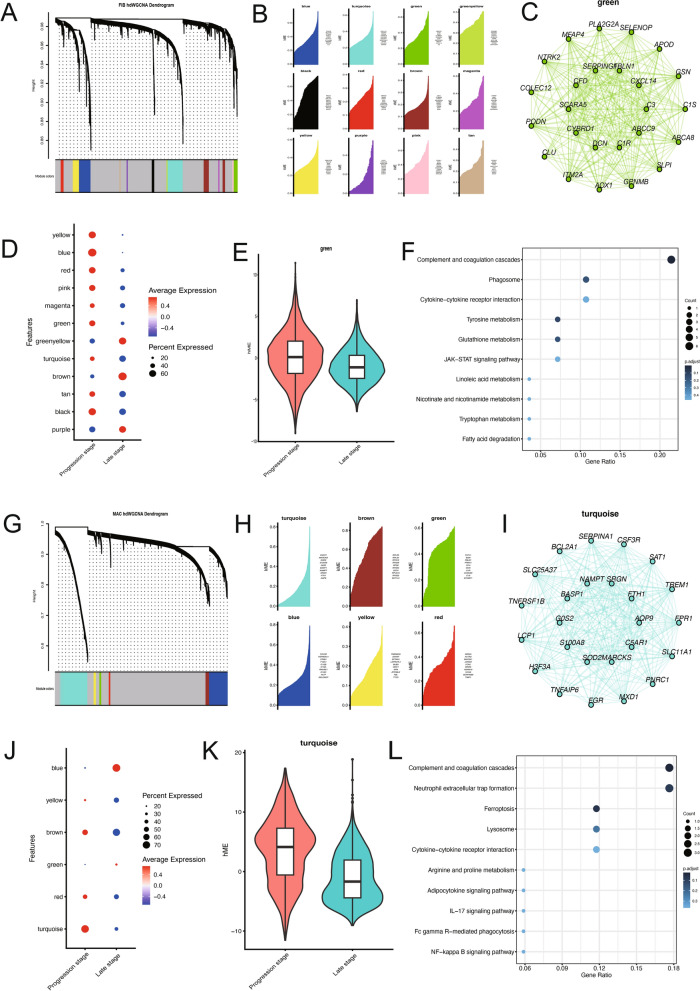

PLA2G2A is associated with the activation of complement and coagulation cascades

To investigate the role of PLA2G2A in the progression of carotid atherosclerotic plaques, we employed HDWGCNA analysis on fibroblasts to identify genes sharing an expression pattern with PLA2G2A. Under a soft-thresholding power of 7, we identified 12 gene co-expression modules, of which 9 modules exhibited relatively higher expression in progression-stage plaques (Fig. 4A, B). Notably, PLA2G2A was identified as the hub gene within the green module (Fig. 4C), which was highly expressed in progression-stage plaque group (Fig. 4D, E). Subsequent functional enrichment analysis of the hub genes in the green module revealed that the functions of these genes co-expressed with PLA2G2A were predominantly involved in inflammatory responses and the complement and coagulation cascade pathways (Fig. 4F). Similarly, we performed HDWGCNA analysis on macrophages and identified 6 modules. The turquoise module was highly expressed in progression-stage plaque group. Enrichment analysis of this module also showed that the functions of these genes were primarily enriched in the complement and coagulation cascade pathways (Fig. 4G, L). This result is consistent with the characteristics of the PA region in the previous plaque data, suggesting that in the progression stage of carotid atherosclerotic plaque formation, fibroblasts express high levels of PLA2G2A, which might activate the complement and coagulation cascade pathways in macrophages, thereby influencing the progression of CA.

Fig. 4.

PLA2G2A is associated with the activation of complement and coagulation cascade pathways. A Dendrogram showing hdWGCNA analysis of the fibroblasts. B Ridge plot showing the 12 gene modules identified by co-expression analysis. C Co-expression network plot showing PLA2G2A as the hub gene of the green module. D, E Bubble plot (D) and violin plot (E) showing genes in the green module were highly expressed in the progression stage. F KEGG analysis of the hub genes in the green module showing enrichment in pathways such as complement and coagulation cascades and cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction. G Dendrogram showing hdWGCNA analysis of the macrophages. H Ridge plot showing the 6 modules identified by co-expression analysis. I Network plot showing the hub genes of the turquoise module. J, K Bubble plot (J) and violin plot (K) showing genes in the turquoise module were highly expressed in the progression stage. L KEGG analysis of the hub genes in the turquoise module showing enrichment of pathways. WGCNA: Weighted gene co-expression network analysis

PLA2G2A promotes CA by complement and coagulation cascades in macrophages

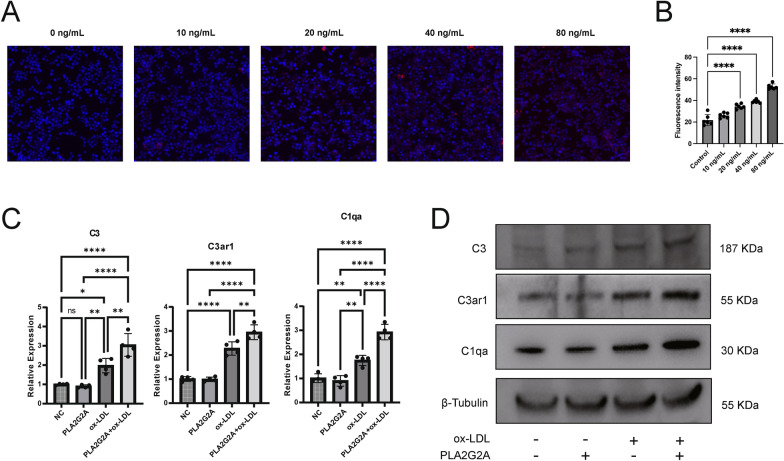

RAW264.7 cells were treated with different concentrations of PLA2G2A protein (10–80 ng/mL) for 24 h and with Dil-ox-LDL. Fluorescence microscopy revealed that as the concentration of PLA2G2A protein increased, lipid uptake by the cells also gradually increased (Fig. 5A, B). Subsequently, we examined the expression changes of key molecules in the complement and coagulation cascades at the RNA and protein levels in the macrophage atherosclerosis model (stimulated with 50 μg/mL ox-LDL for 24 h) after adding PLA2G2A protein (80 ng/mL). The results showed that the addition of PLA2G2A alone had no effect on the complement and coagulation cascades, but in the presence of ox-LDL, PLA2G2A enhanced the activation of these pathways (Fig. 5C, D).

Fig. 5.

PLA2G2A promotes the progression of CA by activating the complement and coagulation cascades in macrophages. A, B Fluorescence images and fluorescence intensity quantification showing lipid uptake in RAW264.7 cells after addition of different concentrations of PLA2G2A. C, D RNA and protein expression levels of the molecules in the complement and coagulation cascades in RAW264.7 cells after treatment with ox-LDL and PLA2G2A. (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001;****p < 0.0001)

The transcription factors of PLA2G2A play a crucial role in the progression stage of CA

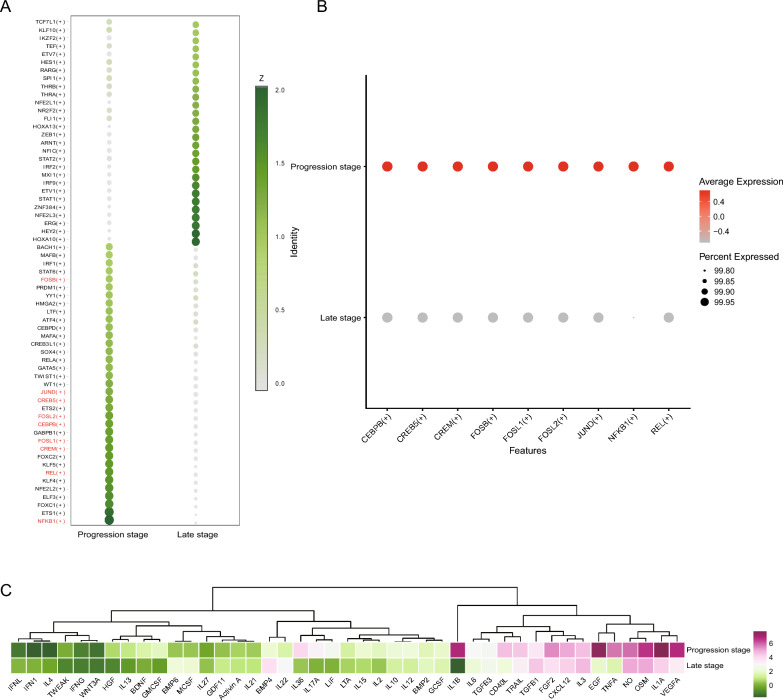

Using SCENIC analysis to identify key transcription factors in fibroblasts during the progression stage of CA, we discovered that plaque fibroblasts had distinct transcriptional regulatory networks in the progression and late stages (Fig. 6A). Additionally, we predicted transcription factors for PLA2G2A, such as CEBPB, CREB5, CREM, JUND, and REL (Table S1), and found that these transcription factors were highly expressed in the progression stage of CA (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, these transcription factors are also key regulators characteristic of the progression stage. These data suggested that the transcription factors of PLA2G2A play a critical role in regulating the function of fibroblasts in progressing CA. Furthermore, using the CytoSig platform, we predicted the activity of fibroblasts in response to various cytokines at both the progression and late stages. The results suggested that fibroblasts in the progression stage exhibit relatively higher activity in response to cytokines (Fig. 6C), which may be closely related to the more extensive pathological processes occurring in the progression stage.

Fig. 6.

Transcription factor prediction in fibroblasts by SCENIC analysis. A Heatmap showing the Z-scores of transcription factor expression between the progression and late stages of CA. B Dot plot showing that key transcription factors of PLA2G2A are highly expressed in progression-stage fibroblasts. C Dendrogram and heatmap generated by Cytosig analysis showing that the progression-stage fibroblasts have a stronger response to cytokine signaling. SCENIC: Single-Cell rEgulatory Network Inference and Clustering

Discussion

Previous research has demonstrated that PLA2G2A plays a crucial role in the development of atherosclerosis [7], but its precise mechanisms remain unclear. In this study, by comparing the serum sPLA2 levels in patients with varying degrees of carotid artery stenosis, we observed statistically significant differences between different stenosis severities, with notably higher diagnostic value in patients with mild carotid artery stenosis. Subsequently, we described the expression characteristics of PLA2G2A in atherosclerotic plaques in the PA and AC regions of the carotid artery using single-cell transcriptomic data. We found that PLA2G2A is primarily expressed in vascular fibroblasts and shows strong interactions with macrophages in the PA region, particularly in pathways related to the complement system. Finally, by comparing single-cell transcriptomic data of the progression and late stages of carotid artery plaques, we validated the aforementioned findings and identified potential transcription factors that may regulate early atherosclerotic progression and PLA2G2A expression.

CA is a chronic inflammatory disease of the arterial wall and a primary underlying cause of cerebrovascular diseases [13]. However, research on early identification of this critical event is scant. Some blood biomarkers might be associated with the biological pathways of early CA, such as C-reactive protein, troponin I, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide, copeptin, asymmetric dimethylarginine and so on [14, 15]. Yet, these markers fall short in accurately assessing early CA. Thus, there's a need for more sensitive and specific biomarkers for early assessment and timely intervention of CA.

The PLA2 superfamily can induce changes in membrane composition, activate inflammatory cascades, and alter cellular signaling pathways [3]. sPLA2, a significant member of the PLA2 superfamily, hydrolyzes phospholipids and lipoproteins on the cell membrane, producing pro-inflammatory eicosanoids [4]. Previous research indicates that serum sPLA2 is an acute-phase protein, functioning in inflammatory responses to infection and trauma [16]. This sPLA2 activity can also alter lipoprotein particles in circulation, increase lipoprotein binding to vascular wall proteoglycans, and promote foam cell formation [17]. Existing studies have identified a correlation between serum sPLA2 levels and atherosclerosis [4, 18], but clinical trials aimed at reducing inflammation by inhibiting serum sPLA2 levels to improve cardiovascular events have been disappointing [19]. The patients enrolled in these clinical trials had their serum sPLA2 levels measured after experiencing atherosclerosis-related cardiovascular events, representing late atherosclerotic lesions. It is well known that atherosclerosis becomes irreversible after the formation of a calcified core and fibrous cap. Our findings show that fibroblasts highly express PLA2G2A and interact strongly with macrophages during the progression of carotid plaques, but this phenomenon is significantly diminished in the late stages. This suggests that sPLA2 plays a crucial role in the early stages of atherosclerotic lesions, while in the late stages, despite higher serum sPLA2 levels, its impact on the existing lesions may be minimal. Moreover, sPLA2 may have multiple roles during the progression of atherosclerosis. Previous studies have confirmed that sPLA2, as an inflammatory molecule, can affect LDL levels, leading to hypotheses and interventions targeting this mechanism. However, the overall role of sPLA2 in the pathogenesis of Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease may be more complex. Our results suggest that sPLA2 may function by activating the complement and coagulation cascades in macrophages, but the concentration-dependence of sPLA2 in this process remains unknown. It is possible that even after reducing sPLA2 levels with an inhibitor, the complement and coagulation cascades may not be fully suppressed. In summary, the less-than-ideal results of these clinical trials may be due to the late timing of sPLA2 intervention or the fact that, although Varespladib effectively reduced serum sPLA2 levels, it failed to influence the cascade reactions triggered by sPLA2. Our research offers a new perspective on the mechanisms by which sPLA2 promotes atherosclerosis.

Atherosclerosis is characterized by lipid deposition, endothelial inflammation, migration of smooth muscle cells (SMCs) from the media to the newly formed plaque, and eventual plaque rupture [1]. Past research on atherosclerosis has primarily focused on the endothelial cells, SMCs, and inflammatory cells in the intima and media [20–22]. However, recent findings highlight the adventitia, the supportive tissue of arteries, as playing a crucial role in atherosclerosis, with adventitial remodeling being a key component of the disease process [10, 23]. Fibroblasts, which constitute the main component of the adventitia and account for 33% of the cellular makeup of the aorta [24], engage in crosstalk with endothelial cells and SMCs during atherosclerosis. They participate in the regulation of chemical and mechanical signals through the analysis of cytokines and the extracellular matrix (ECM), contributing to adventitial remodeling [11]. Wang et al. found that periostin activates adventitial fibroblasts, as well as focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Src phosphorylation, playing a role in the adventitial remodeling of atherosclerosis [25]. Additionally, research by Lopes et al. showed that dysfunctions in fibroblast lysosomal activity and autophagy, along with the induction of apoptosis, can accelerate the progression of atherosclerosis [26]. With the introduction of the “adventitia theory”, fibroblasts, the main components of the adventitia, have gradually gained attention. The adventitia theory particularly emphasizes that cells and molecular signals within the adventitia can regulate the progression of atherosclerosis by influencing the behavior of cells in the media and intima. This interaction suggests that the adventitia is not merely a passive supporting structure but plays an active regulatory role in the pathological process. Our research findings align with the adventitia theory, highlighting the regulatory role of fibroblasts in the adventitia during the progression stage of atherosclerosis. The American Heart Association (AHA) believes that pathological changes occurring after the atheroma stage are irreversible [27]. According to our findings, significant cell–cell interactions occur between vascular fibroblasts and macrophages in the early stages of carotid plaque development. This discovery may offer new insights for early intervention in atherosclerosis in clinical settings.

The complement system, as a cornerstone of innate immunity, plays a crucial role in maintaining homeostasis during inflammatory responses [28]. Initially, the complement system was thought to have a simple role in atherosclerosis by mediating endothelial cell activation and innate immunity, with pharmacological inhibition of plasma complement successfully reducing vascular inflammation in atherosclerosis [29]. However, as research has progressed, it has been found that the complement system also plays significant roles within the extracellular matrix and intracellularly [30]. Intracellular complement activation in monocytes and macrophages is fundamental to the sustained activation of atherosclerotic cells [31]. Macrophages, as major participants in atherosclerotic inflammatory responses, are influenced by the complement system not only through mediating M2/M1 macrophage polarization to promote atherosclerosis progression [32], but also through the findings of Kiss et al., who discovered that increased C3 levels in macrophages can inhibit atherosclerosis progression by affecting macrophage phagocytosis [33]. Therefore, understanding the various functions of the complement system during different stages of atherosclerosis progression is of paramount importance. As mentioned earlier, sPLA2 hydrolyzes glycerophospholipids in lipoproteins and cell membranes, producing pro-inflammatory lysophospholipids and non-esterified fatty acids [34]. On one hand, phospholipid hydrolysis can impair the clearance of low-density lipoproteins by damaging apolipoprotein receptors; on the other hand, the hydrolysis of high-density lipoproteins leads to a reduction in cholesterol efflux capacity, causing cholesterol crystal deposition [35]. Cholesterol crystals can then induce an inflammatory response by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome through caspase-1 [36]. Additionally, phospholipid hydrolysis generates arachidonic acid, lysophospholipids, and non-esterified fatty acids, which further increase oxidative stress and activate inflammatory pathways in various vascular cells. NLRP3 can also directly activate the intracellular complement system [37]. Therefore, we hypothesize that sPLA2 secreted by fibroblasts promotes complement and coagulation pathway activation by impairing macrophage-mediated lipoprotein clearance, leading to cholesterol deposition and subsequent activation of inflammasomes such as NLRP3.

Conclusions

In summary, by combining a clinical cohort of patients with carotid artery stenosis and single-cell transcriptomics, our study found that during the progression stage of CA, vascular fibroblasts exhibit high expression of PLA2G2A, which activates the complement and coagulation cascade pathways in macrophages, thereby promoting plaque progression. These findings highlight the significant differences in the pathophysiological processes of CA at different stages and provide new insights for the early diagnosis and intervention of CA. However, this study has certain limitations. First, the clinical data were obtained from a single center, and the sample size was relatively small, which may introduce statistical bias. Second, due to significant individual differences among patients, further validation of these conclusions will be needed in a larger cohort with more extensive single-cell data.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CA

Carotid atherosclerosis

- sPLA2

Secretory phospholipase A2

- TG

Triglyceride

- TC

Total cholesterol

- LDL-C

Low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HDL-C

High density lipoprotein cholesterol

- Lp-PLA2

Lipoprotein-associated phospholipases A2

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- AC

Atherosclerotic core

- PA

Proximal adjacent

- UMAP

Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection

- GO

Gene Ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- GSEA

Gene set enrichment analysis

- WGCNA

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis

- SCENIC

Single-cell regulatory network inference and clustering

- ROC

Receiver operating curve

- AUC

Area under the receiver operating curve

- CI

Confidence interval

Author contributions

XW, SL, YX and ZX conceived and designed research. Data analysis were performed by XW, SL, CL, GR, FZ, SC, JZ and XL. XW and ZL wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The Non-profit Central Research Institute and Major Science to Yuming Xu (Grant No. 2020-PT310-01), and Technology Projects of Henan Province in 2020 to Yuming Xu (Grant No. 201300310300).

Availability of data and materials

The single-cell dataset for carotid plaque used in this study partly originates from the GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), with the accession number GSE159677.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (2018-KY-0067-001).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Due to their equal contributions to the article, Xin Wang and Shen Li are recognized as co-first authors, while Zongping Xia and Yuming Xu are acknowledged as co-corresponding authors.

Contributor Information

Yuming Xu, Email: xuyuming@zzu.edu.cn.

Zongping Xia, Email: zxia2018@zzu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Libby P, Buring JE, Badimon L, Hansson GK, Deanfield J, Bittencourt MS, Tokgözoğlu L, Lewis EF. Atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song P, Fang Z, Wang H, Cai Y, Rahimi K, Zhu Y, Fowkes FGR, Fowkes FJI, Rudan I. Global and regional prevalence, burden, and risk factors for carotid atherosclerosis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e721–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talmud PJ, Holmes MV. Deciphering the causal role of sPLA2s and Lp-PLA2 in coronary heart disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:2281–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bostrom MA, Boyanovsky BB, Jordan CT, Wadsworth MP, Taatjes DJ, de Beer FC, Webb NR. Group v secretory phospholipase A2 promotes atherosclerosis: evidence from genetically altered mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:600–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mallat Z, Lambeau G, Tedgui A. Lipoprotein-associated and secreted phospholipases A₂ in cardiovascular disease: roles as biological effectors and biomarkers. Circulation. 2010;122:2183–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang F, Wang K, Shen J. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2: the story continues. Med Res Rev. 2020;40:79–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenson RS, Hurt-Camejo E. Phospholipase A2 enzymes and the risk of atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2899–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun S, Liu F, Fan F, Chen N, Pan X, Wei Z, Zhang Y. Exploring the mechanism of atherosclerosis and the intervention of traditional Chinese medicine combined with mesenchymal stem cells based on inflammatory targets. Heliyon. 2023;9: e22005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fras Z, Tršan J, Banach M. On the present and future role of Lp-PLA(2) in atherosclerosis-related cardiovascular risk prediction and management. Arch Med Sci. 2021;17:954–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coen M, Gabbiani G, Bochaton-Piallat ML. Myofibroblast-mediated adventitial remodeling: an underestimated player in arterial pathology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2391–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh S, Torzewski M. Fibroblasts and their pathological functions in the fibrosis of aortic valve sclerosis and atherosclerosis. Biomolecules. 2019;9:472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trial NASCE. Methods, patient characteristics, and progress. Stroke. 1991;22:711–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saigusa R, Winkels H, Ley K. T cell subsets and functions in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:387–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnabel RB, Yin X, Larson MG, Yamamoto JF, Fontes JD, Kathiresan S, Rong J, Levy D, Keaney JF Jr, Wang TJ, et al. Multiple inflammatory biomarkers in relation to cardiovascular events and mortality in the community. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:1728–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oluleye OW, Folsom AR, Nambi V, Lutsey PL, Ballantyne CM. Troponin T, B-type natriuretic peptide, C-reactive protein, and cause-specific mortality. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23:66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birts CN, Barton CH, Wilton DC. Catalytic and non-catalytic functions of human IIA phospholipase A2. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato H, Kato R, Isogai Y, Saka G, Ohtsuki M, Taketomi Y, Yamamoto K, Tsutsumi K, Yamada J, Masuda S, et al. Analyses of group III secreted phospholipase A2 transgenic mice reveal potential participation of this enzyme in plasma lipoprotein modification, macrophage foam cell formation, and atherosclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:33483–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lind L, Simon T, Johansson L, Kotti S, Hansen T, Machecourt J, Ninio E, Tedgui A, Danchin N, Ahlström H, Mallat Z. Circulating levels of secretory- and lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 activities: relation to atherosclerotic plaques and future all-cause mortality. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2946–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arsenault BJ, Boekholdt SM, Kastelein JJ. Varespladib: targeting the inflammatory face of atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:923–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett MR, Sinha S, Owens GK. Vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016;118:692–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li M, Qian M, Kyler K, Xu J. Endothelial-vascular smooth muscle cells interactions in atherosclerosis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2018;5:151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore KJ, Koplev S, Fisher EA, Tabas I, Björkegren JLM, Doran AC, Kovacic JC. Macrophage trafficking, inflammatory resolution, and genomics in atherosclerosis: JACC macrophage in CVD series (Part 2). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2181–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tinajero MG, Gotlieb AI. Recent developments in vascular adventitial pathobiology: the dynamic adventitia as a complex regulator of vascular disease. Am J Pathol. 2020;190:520–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalluri AS, Vellarikkal SK, Edelman ER, Nguyen L, Subramanian A, Ellinor PT, Regev A, Kathiresan S, Gupta RM. Single-cell analysis of the normal mouse aorta reveals functionally distinct endothelial cell populations. Circulation. 2019;140:147–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Z, Li G, Li M, Hu L, Hao Z, Li Q, Sun C. Periostin contributes to the adventitial remodeling of atherosclerosis by activating adventitial fibroblasts. Atheroscler Plus. 2022;50:57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopes E, Machado-Oliveira G, Simões CG, Ferreira IS, Ramos C, Ramalho J, Soares MIL, Melo T, Puertollano R, Marques ARA, Vieira OV. Cholesteryl hemiazelate present in cardiovascular disease patients causes lysosome dysfunction in murine fibroblasts. Cells. 2023;12:2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jebari-Benslaiman S, Galicia-García U, Larrea-Sebal A, Olaetxea JR, Alloza I, Vandenbroeck K, Benito-Vicente A, Martín C. Pathophysiology of atherosclerosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:3346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maffia P, Mauro C, Case A, Kemper C. Canonical and non-canonical roles of complement in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2024. 10.1038/s41569-024-01016-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie CB, Qin L, Li G, Fang C, Kirkiles-Smith NC, Tellides G, Pober JS, Jane-Wit D. Complement membrane attack complexes assemble NLRP3 inflammasomes triggering IL-1 activation of IFN-γ-primed human endothelium. Circ Res. 2019;124:1747–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.West EE, Kemper C. Complosome—the intracellular complement system. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2023;19:426–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niyonzima N, Rahman J, Kunz N, West EE, Freiwald T, Desai JV, Merle NS, Gidon A, Sporsheim B, Lionakis MS, et al. Mitochondrial C5aR1 activity in macrophages controls IL-1β production underlying sterile inflammation. Sci Immunol. 2021;6: eabf2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tao J, Zhao J, Qi XM, Wu YG. Complement-mediated M2/M1 macrophage polarization may be involved in crescent formation in lupus nephritis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;101:108278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiss MG, Papac-Miličević N, Porsch F, Tsiantoulas D, Hendrikx T, Takaoka M, Dinh HQ, Narzt MS, Göderle L, Ozsvár-Kozma M, et al. Cell-autonomous regulation of complement C3 by factor H limits macrophage efferocytosis and exacerbates atherosclerosis. Immunity. 2023;56:1809-1824.e1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Camejo G. Lysophospholipids: effectors mediating the contribution of dyslipidemia to calcification associated with atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2010;211:36–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sartipy P, Johansen B, Gâsvik K, Hurt-Camejo E. Molecular basis for the association of group IIA phospholipase A(2) and decorin in human atherosclerotic lesions. Circ Res. 2000;86:707–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, Sirois CM, Vladimer G, Bauernfeind FG, Abela GS, Franchi L, Nuñez G, Schnurr M, et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 2010;464:1357–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arbore G, West EE, Spolski R, Robertson AAB, Klos A, Rheinheimer C, Dutow P, Woodruff TM, Yu ZX, O’Neill LA, et al. T helper 1 immunity requires complement-driven NLRP3 inflammasome activity in CD4⁺ T cells. Science. 2016;352: aad1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The single-cell dataset for carotid plaque used in this study partly originates from the GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), with the accession number GSE159677.