Abstract

Background

This study investigated the perceived barriers and potential facilitators for culturally sensitive care among general practitioners in Flanders. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for improving healthcare quality and equity.

Methodology

Twenty-one in-depth interviews were conducted with Flemish GPs. Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis was employed to develop and interpret themes that elucidate shared underlying meanings and capture the nuanced challenges and strategies related to cultural sensitivity in healthcare.

Results

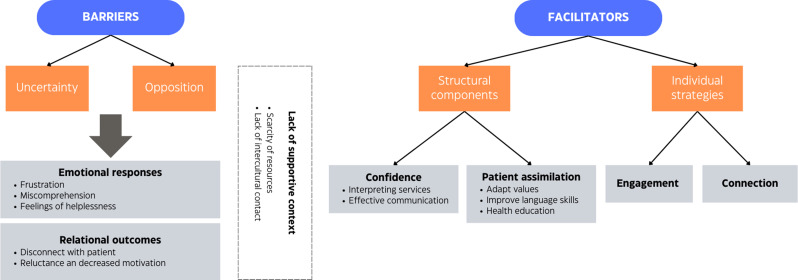

Two core themes were generated: GPs’ uncertainty and opposition. These themes manifest in emotional responses such as frustration, miscomprehension, and feelings of helplessness, influencing relational outcomes marked by patient disconnect and reduced motivation for cultural sensitivity. The barriers identified are exacerbated by resource scarcity and limited intercultural contact. Conversely, facilitators include structural elements like interpreters and individual strategies such as engagement, aimed at enhancing GPs’ confidence in culturally diverse encounters. A meta-theme of perceived lack of control underscores the challenges, particularly regarding language barriers and resource constraints, highlighting the critical role of GPs’ empowerment through enhanced intercultural communication skills.

Conclusion

Addressing GPs’ uncertainties and oppositions can mitigate related issues, thereby promoting comprehensive culturally sensitive care. Essential strategies include continuous education and policy reforms to dismantle structural barriers. Moreover, incentivizing culturally sensitive care through quality care financial incentives could bolster GP motivation. These insights are pivotal for stakeholders—practitioners, policymakers, and educators—committed to advancing culturally sensitive healthcare practices and, ultimately, for fostering more equitable care provision.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12875-024-02630-y.

Keywords: Culturally sensitive care, General practitioners, Barriers and facilitators, Reflexive thematic analysis, Health equity, Intercultural communication

Background

Ethnic healthcare disparities have consistently been documented on a global scale [1]. Patients whose ethnic background differs from the majority population face more difficulties accessing healthcare, receive a lower quality of care, and report lower satisfaction rates compared to the dominant population [2–4]. These inequalities persist even when accounting for various socio-demographic factors previously demonstrated to influence health outcomes (e.g. insurance status or ability to pay for care), highlighting the profound impact of ethnicity on health [5–7]. Recognizing the need to improve the quality of healthcare for ethnic minority patients and bridge the gap of healthcare disparities, there has been a growing recognition of the importance and benefits of cultural sensitivity in healthcare provision.

The terms ‘ethnicity’ and ‘culture’ are often used synonymously in health sciences literature, yet they are distinct concepts [8–10]. Within a healthcare context, culture encompasses shared values, norms, roles, and assumptions that shape individuals’ health beliefs and behaviors. Ethnicity, in turn, is a socially constructed category that describes individuals who identify with the same category, often characterized by cultural elements such as language, religion, sense of history, traditions, values, or dietary habits that are used to draw boundaries around in- and out-groups [8, 11].

It is important to recognize that culture is not static or fixed; adherence to cultural elements like norms, beliefs and values may vary among members of the same ethnic group based on differences in age, gender, class, personality, and other factors, highlighting the heterogeneity or within-group differences in ethnic groups [12]. Additionally, the term ‘ethnic minority groups’ refers to diverse and heterogeneous groups that practice different cultural norms and values from those of the majority culture, which is often the numerically largest group in a given society. Ethnic minority groups vary in duration of stay, including newly arrived immigrants and long-established communities.

While culture is relevant to everyone’s health and healthcare experience, its importance may be particularly pronounced for ethnic minority patients who tend to receive care within systems largely organized by and staffed with majority group members [1, 9, 13]. This is partly why healthcare providers’ cultural sensitivity has received increasing attention. Failing to account for both providers’ and patients’ culture during intercultural care encounters—interactions with patients from diverse ethnic backgrounds [14]—may result in misunderstandings, diagnostic errors, and patient perceptions of discrimination, thereby perpetuating health disparities.

‘Cultural sensitivity’, often referred to as ‘cultural competence’, emphasizes the need for healthcare providers and systems to be aware of and responsive to patients’ cultural backgrounds and perspectives [15, 16]. Despite numerous appeals for consensus in the literature [17–19], conceptual clarity remains lacking. Most definitions of cultural sensitivity and related concepts (e.g. cultural competence, cultural humility, or cultural safety) refer to a specific set of knowledge, attitudes, and skills to improve the quality of care for diverse patient populations [20, 21]. Within the domain of healthcare, cultural sensitivity necessitates an awareness of and willingness to delve into patients’ and providers’ perspectives, values, and biases. It entails a commitment to cultural desire (a genuine motivation to be culturally aware, skillful and knowledgeable [22] and continuous critical self-reflection [22–24]. Embracing this individualized and tailored approach to patient care is essential, as opposed to relying on conscious or unconscious stereotypes, which oversimplify cultures and overlook the diversity within cultural groups. In sum, culturally sensitive healthcare providers acknowledge the importance of culture in healthcare and tailor care services to meet the unique cultural needs of patients, integrating cultural sensitivity with patient-centered and shared decision-making approaches [14, 25–27]. It requires care providers to understand how both patients’ and providers’ cultural backgrounds can influence health perceptions and behaviors, within the framework of lifelong learning [21, 24, 28–30].

Research has established how cultural sensitivity in healthcare results in increased patient satisfaction and trust in providers [31–33], better therapeutic relationships [34], increased therapy adherence [35, 36] and overall improved health outcomes [17, 20]. Consequently, considerable efforts have been directed to enhancing healthcare providers’ cultural sensitivity. However, while these interventions have shown modest increases in provider knowledge and attitudes, their impact on actual provider behavior and patient outcomes remains limited [19, 37, 38].

This challenge has spurred researchers to investigate the underlying reasons for the limited adoption of culturally sensitive strategies in healthcare. Consequently, various barriers have been identified across different healthcare settings. For instance, Mohammad et al. [39] reported language barriers as the main challenge in providing culturally sensitive care in pharmacy. In dental care, affordability, negative provider experiences and language or communication issues are the most prominent barriers [40]. For nurses, the main reported barriers comprise the large diversity in patient populations, lack of appropriate resources and self-reported biases and prejudices [41, 42]. The most prominent barriers in rehabilitation services include language, limited resources, and cultural differences [43]. Such cultural differences can entail variations in gender roles, the extent of family involvement in care, and the level of patient involvement in decision-making regarding treatment, which constitute barriers to cultural sensitivity for care providers in various health settings. However, evidence remains relatively scarce in the domain of general practice despite the crucial role of general practitioners (GPs) in care provision for diverse populations [29, 44]. Existing research does highlight language barriers as the most prominent obstacle, with cultural differences and time constraints also posing significant challenges to GPs in providing culturally sensitive care [45–48].

The limited existing research is also predominantly conducted in North America and often combines GPs’ perspectives with those of other healthcare professionals. Focused research on GPs is imperative as perceived barriers may vary significantly among different healthcare providers [45]. Additionally, studies conducted in diverse geographical regions would provide valuable insights, given that healthcare providers interact with patients who use various cultural scripts. The Flemish context, the largest region of Belgium, is particularly noteworthy due to its extensive and significant history of migration [49], aligning with the concept of ‘superdiversity’ [50]. However, the ethnic diversity among Flemish GPs is noticeably lacking by comparison [51, 52]. Although the Flemish government asserts that it provides highly accessible primary care [53], several studies have revealed a higher prevalence of discriminatory and inequitable care practices compared to other European countries [49, 54].

Therefore, this study aims not only to capture GPs’ perceived barriers to providing culturally sensitive care within a Flemish context but also to identify potential facilitators or strategies that GPs recognize as instrumental in overcoming these barriers. We conducted an in-depth qualitative study of GPs’ perceptions, employing Braun and Clarke’s [55–57] reflexive thematic analysis to develop latent, implicit themes indicative of participants’ shared underlying meanings. Through this exploration, we establish a comprehensive overview of the factors impeding and potentially facilitating culturally sensitive care practices in primary care settings. The insights generated from this study can inform targeted interventions and policy adjustments, enhancing cultural sensitivity in primary care and, by doing so, promoting health equity.

Methodology

Study design

We conducted a qualitative study employing semi-structured, in-depth interviews with Flemish GPs to explore their perceived barriers and facilitators in providing culturally sensitive care in general practice. Our methodology aimed to delve into the nuanced experiences of GPs in navigating cultural diversity within their practice, seeking a detailed and comprehensive understanding of each participant’s experiences and perspectives [56].

A topic guide, developed collaboratively by all authors based on existing literature and our research objectives, underwent iterative revisions to refine its content and scope (Supplementary file 1). To ensure relevance and clarity of the interview questions, two pilot interviews were conducted involving GPs experienced in cross-cultural care and qualitative research.

Participants and setting

The participants were selected from a group of GPs who had taken part in a previous study [58] on consulting behavior and intercultural effectiveness. The selected GPs were contacted via email and invited to provide additional insights on culturally sensitive care. Participants were selected purposively, based on their gender, years of experience, frequency of encountering ethnic minority patients and practice characteristics. This selection aimed to achieve a diverse participant composition and to include GPs with both positive and negative perceptions of cultural sensitivity. Such perceptions were derived from attitudinal scales in the initial study, which captured GPs’ views and attitudes towards other cultures and ethnic minority patients [59].

We specifically sought to include a diverse range of participants with varying experiences and perspectives to capture a broad spectrum of barriers and facilitators. This approach increases the likelihood that our findings will reflect a wide array of insights. Previous studies for instance demonstrated or alluded to associations between GPs’ gender, age, and their effectiveness or ability to provide culturally sensitive care [60].

The participant composition included both GPs with exemplary, average and substandard performances in intercultural consultations and effectiveness, as measured by Leung et al.‘s intercultural effectiveness framework [61]. Specifically, the participating GPs consisted of eight female and 13 male GPs, with a mean age of 45.1 years, ranging from 27 to 64. Most respondents had not undergone any culturally sensitive training interventions or training. Further demographic details are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

GP characteristics

| General Practitioners | N/M |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| female | 8 |

| male | 13 |

| Age | 45.1 |

| min | 27 |

| max | 64 |

| Years of experience | 17.19 |

| min | 1 |

| max | 37 |

| Practice composition | |

| solo practice | 4 |

| duo practice | 8 |

| group practice | 9 |

| Frequency consulting ethnic minority patients | |

| (almost) never | 1 |

| once or a few times a month | 1 |

| weekly | 6 |

| few times a week | 6 |

| daily | 7 |

| Followed culturally sensitive training | |

| yes | 2 |

| no | 19 |

Data collection

Interviews were conducted between April and September 2020, with each session lasting between 30 and 60 min and scheduled according to respondents’ preferences. Audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed by students and interns who received targeted training on notating potential identifiers, inaudible segments, and emotional content according to consistent transcription conventions. These conventions allowed us to capture non-verbal cues and other relevant details, while the training aimed to minimize transcriptionist effects [62]. Each transcription was subsequently reviewed and checked for typographical errors before being fully anonymized.

Data analysis

Based on Braun and Clarke’s approach [55–57], a reflexive thematic analysis method was applied to analyze interview transcripts, employing version R1 of Nvivo. This method facilitated the exploration of perceived barriers and facilitators to culturally sensitive care in general practice, allowing for both deductive and inductive strategies. Drawing upon previous research conducted in general practice and other healthcare contexts, this approach can build upon established findings while accommodating the emergence of novel, inductive themes. Moreover, a reflexive thematic analysis approach allows for explicit, surface-level, and implicit, latent knowledge and theme generation, wherein our team of researchers assumes a central role in interpreting and engaging with the data.

This approach entails a recursive and analytic process, including the well-established six phases of thematic analysis: familiarizing with the data, generating initial codes, searching, reviewing and defining themes and, lastly, reporting the analysis according to the ‘Reflexive Thematic Analysis Reporting Guidelines’ [55–57]. Characterized by continuous reflexive questioning and deliberation between coders regarding coding and interpretation, themes are generated and developed rather than ‘revealed’. This collaborative and reflexive coding approach aims to develop a rich and comprehensive understanding of the data.

Initially, two coders (RV and LR) independently coded a subset of three interviews, followed by thorough discussions to compare and contrast codes, thoughts, and interpretations. The outcomes of these discussions were then shared with all co-authors, who provided their own interpretations and perspectives. Subsequently, the same two coders autonomously coded the remaining 18 interviews, followed by further discussions and comparisons among the entire research team to integrate additional insights. This collaborative, iterative and reflexive coding approach enhanced the depth of our analysis. Moreover, our research team comprises sociologists, a cultural anthropologist, a GP, and experts in health (in)equity, providing a multidisciplinary perspective on the data.

Ethical considerations

This study received approval by the Ethics Committee of University Hospital Ghent (EC registration number: BC-08924). Before conducting the interview, all GPs signed an informed consent. At the beginning of each interview, respondents were reminded of their participation’s voluntary and anonymous nature. They were assured that collected data would be securely stored and that they retained the right to end the interview at any point.

Results

In the following sections, we present the results of our reflexive thematic analysis. We start by discussing the explicit, semantic topics participants mentioned, followed by a more in-depth exploration of the latent, underlying meanings we derived from these topics. This process culminates in the development of our themes, adhering to Braun and Clarke’s methodological framework [56, 57], visualized in a thematic map (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Thematic map

First, we provide an overview of the perceived barriers encountered by GPs in delivering culturally sensitive care, along with an exploration of the additional consequences and structural complexities associated with these barriers. Next, we delineate potential facilitators, categorizing them into structural components that may assist in overcoming these barriers, and the individual strategies elucidated by GPs.

Perceived barriers

Experiencing uncertainty and opposition due to language and moral barriers

When discussing the obstacles to providing culturally sensitive care with GPs, the conversations primarily focused on two main topics: language barriers and cultural differences. In accordance with previous studies, in general practice [45, 47, 48] and other health contexts [42, 43], these notions are identified the most prominent and complex barriers for healthcare providers to overcome in providing culturally sensitive care.

Language! Language, absolutely, language is access to everything. Language is so connecting and, um, since forming relationships is the first thing that needs to happen in general practice, then language is the most important. (female GP, 53)

When patients and GPs do not share a common language, consultations become significantly more complicated. Participating GPs describe how language barriers result in a loss of “nuance”, making it harder to use intonation and show empathy. This difficulty extends to expressing emotions, demonstrating genuine concern, addressing patients’ ideas and concerns, and motivating them. Consultations involving sensitive psychological discussions are perceived as exceedingly problematic, highlighting the complexity of the issue.

Language barriers often result in miscommunication, complicating appointment scheduling and referrals. Consequently, multiple participants described how consultations, diagnostic explanations and treatment recommendations are often limited to basic medical aspects, overlooking the relational dimension of care and contributing to inferior quality of care and treatment outcomes.

If they can tell it at all. But try explaining that when you’re Afghan and don’t understand what I’m saying, and I don’t understand what he’s saying […]. It’s really a matter of searching, searching, searching. And very often being left unsatisfied. Have I actually been able to help this person? Very often, I just don’t know. (male GP, 63)

Extending beyond the explicit, surface-level topics discussed by participants, and also identified in previous studies [46–48], we developed a latent theme concerning the impact of language barriers. Specifically, we found that participants shared a common sense of uncertainty due to language barriers. GPs often seem to grapple with uncertainty about whether patients fully comprehend their explanations and instructions. This uncertainty extends to concerns about the accuracy of patients’ descriptions of their symptoms and conditions. As a result, GPs become more hesitant and confused, often questioning the reliability of their anamnesis, the appropriateness of their treatment recommendations, and whether these recommendations are fully understood by their patients.

Moreover, GPs mentioned facing significant challenges in applying the communication models they are familiar with to uncover patients’ ideas, concerns, and expectations. This difficulty heightens their uncertainty about patients’ true concerns, preferences, and broader contextual factors, often leading to misunderstandings or incomprehension. As a result, the pervasive uncertainty induced by language barriers compromises GPs’ ability to provide culturally sensitive care, as the lack of a shared language significantly complicates effective and patient-centered communication, a challenge previously documented in other health services [63, 64].

There are often language problems, making many aspects of the consultation much more difficult. Consider the medical history: understanding ‘what brings you here?’, understanding the other person’s culture, what illness means, what being sick means, what the doctor represents, what a referral means. You name it. In all its facets, it is more challenging, and we are particularly tested in this regard. (male GP, 63)

In addition to language barriers, GPs frequently discussed difficulties arising from cultural differences. Participants discussed several elements of cultural differences, including culturally specific perceptions of illness and explanatory models for symptoms and diseases. As noted by the participants, patients from diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds might conceptualize certain diseases, experience pain, and interpret symptoms in ways that reflect their cultural norms. For instance, GPs observed that patients from particular cultural backgrounds may view discussions about psychological distress as “taboo” or perceive mental health conditions as a sign of “weakness”. Culturally specific health behaviors, particularly dietary preferences, were also commonly discussed.

Finally, GPs often highlighted culturally specific aspects regarding patient-provider relationship and communication. Some GPs perceived ethnic minority patients as more dramatic in expressing symptoms. Additionally, relationships between patients and GPs may be seriously hindered by conflicting cultural views and norms about gender. For example, some GPs reported significant difficulties navigating between emancipatory values and patriarchal values, which can impede effective communication and care provision.

We also observed the underlying theme of uncertainty in GPs’ efforts to navigate cultural differences. For instance, some GPs are unsure about or do not understand why certain aspects might be culturally delicate (e.g. shaking patients’ hands or asking to remove a veil). In addition, however, a second theme was generated. When confronted with cultural differences, GPs frequently seemed to express feelings of opposition.

Culturally specific issues are more like: conducting a consultation as a man with a veiled woman or with a woman where you know that it’s sensitive. How far can and should you go? Those are things that, I think, are a bit more sensitive for me. (male GP, 61)

The theme of opposition entails that GPs often struggle with certain patient expectations, which they perceive as culturally specific. Some GPs seem reluctant to tailor care or to be culturally sensitive to these expectations or norms. This reluctance, whether conscious or unconscious, often stems from a failure to comprehend other cultural norms, leading to disagreement with these preferences and a potential clash with their personal cultural values. An actual barrier to providing culturally sensitive care may not necessarily be the practical challenges but rather GPs’ opposition to specific cultural expectations and preferences.

While the theme of opposition is most evident concerning culturally specific views on relationships and communication with care providers, it was apparent across all observed dimensions of cultural differences.

I think it’s more about the underlying things that you sense a bit, theatrical behavior, demanding behavior, the lack of trust. That it’s more difficult to deal with. Where our expectations and needs sometimes differ from theirs. For example, there are certain cultures where you notice everything just has to be solved with pills, and then it’s okay, whereas in our culture, it’s much less so. We have the idea: you start by reducing sugar intake before we start giving you pills right away. In certain cultures, sugar is consumed so heavily that it’s unthinkable for them not to eat sugar. I find that challenging. I think there are also a lot of things we don’t know. (female GP, 37)

Regarding culturally distinct perceptions of relationships with GPs, some participants opposed certain cultural gender norms and refused to tailor care accordingly. Similarly, several GPs disagreed with some culturally bound negative views on mental health issues and specific health behaviors, such as dietary habits and medication intake adjustments due to religious beliefs. Part of the barriers to cultural sensitivity can consequently involve navigating the complexity of cultural differences while maintaining an overall commitment to culturally sensitive care.

Additionally, some GPs cited their lack of knowledge and familiarity with different cultural values as a challenge. Rather than merely pointing out how different patients can be, some GPs reflected inwards, aligning more closely with the framework of culturally sensitive care provision and cultural awareness [37, 65]. This self-reported lack of intercultural knowledge further amplifies the underlying theme of uncertainty. Several GPs indicated feeling unsure about actions such as suggesting examinations or shaking hands, and the line between professional conduct and patient discomfort.

I mean, there are things I don’t know about other cultures. For example, if I have a veiled Afghan woman as a patient, I don’t know what I am or am not allowed to do. I’m not even sure if I should offer to shake her hand or not. During COVID, that question didn’t arise, and we all wore masks, so there were more similarities. But if she comes in with abdominal pain, can I suggest examining her? Or not? Would that be going too far? Those kinds of questions are related to cultural and religious aspects that I don’t fully understand. So, that plays a role for me. (male GP, 63)

Moreover, in accordance with the framework of culturally sensitive care that emphasizes critical consciousness and self-reflection, GPs, like patients, are influenced by their socio-cultural contexts and values.

We, of course, also learn medicine from a Western perspective. (male GP, 28)

Their educational backgrounds and professional training shape specific cognitive frameworks, often reflecting a Western-centric perspective on medicine, legitimizing mainstream medical knowledge while ignoring other possible perspectives [66, 67]. This perspective, which only a minority of our participants realized and discussed, can diverge significantly from the cultural contexts of diverse patients, further contributing to the uncertainty present in intercultural care encounters.

Consequently, GPs refer to challenges in evaluating patients’ overall circumstances, thoughts, expectations, potential discomfort, and health literacy. When these aspects are difficult to assess, GPs’ ability to provide well-informed recommendations and treatments diminishes, heightening their uncertainty in consultations with patients from diverse ethnic backgrounds.

The biggest problem is, for example, the expectations around technicality, the insistence, even with minor or clearly psychosomatic complaints, on all possible scans, blood tests, and hospital admissions, just to keep following that somatic trail over and over again. And actually, especially when there’s a language barrier, around that psychosomatic approach, it feels like it’s culturally sometimes really difficult to discuss with them, I feel. (male GP, 63)

Furthermore, the theme of uncertainty becomes even more pronounced when cultural differences are combined with language barriers. When GPs encounter patients from diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds, they mentioned struggling to determine whether certain cultural sensitivities are present and, consequently, how to respond appropriately. This uncertainty is exacerbated when the GP and patient do not share a common language or lack proficiency in a shared language, leading to ineffective communication. For instance, GPs may hesitate to ask sensitive or patient-centered questions regarding cultural preferences, especially when communication is hindered by language barriers, fostering reluctance to explore these preferences and involve patients in shared decision-making processes.

In conclusion, our participants acknowledge their limited intercultural knowledge in identifying recurring cultural sensitivities or preferences among patients from diverse ethnic backgrounds. We observed significant uncertainty and hesitation among GPs regarding the appropriate way of exploring patients’ expectations and preferences, particularly when compounded by language barriers. This challenge is further impeded when GPs are opposed to certain cultural values. Collectively, these factors serve as significant barriers to the provision of culturally sensitive care.

Consequences of feeling uncertain or opposed

The overarching themes of uncertainty and opposition as barriers in providing culturally sensitive care resulted in several noteworthy outcomes in GPs’ responses. We categorized these outcomes into two primary themes: GPs’ emotional responses and relational outcomes.

The first emotional reaction we observed in our data was a general frustration among participants, expressed both explicitly and implicitly. This frustration largely stems from the pervasive uncertainty that hinders GPs from providing culturally sensitive care. Feeling unable to assess or understand patients’ contexts, cultural preferences, and medical issues frustrates GPs. Additionally, the effort to ascertain these elements and the subsequent realization of being unable to fully help a patient or provide the same quality of care compounds this frustration, further complicating the provision of culturally sensitive care and possibly decreasing the desire to do so.

We try to understand what being ill means to them. But it often remains just an attempt, it remains an incredible challenge. Every time, it is particularly difficult. I can only say that: it remains difficult. I do not master Afghan; I do not master Ukrainian. If you already speak the language, it makes a world of difference. And even then, the cultural background is so different. It is a challenge every time. (male GP, 63)

Feelings of frustration also resulted from the theme of opposition. Several GPs displayed their frustration with divergent gender norms in various cultures, particularly opposing patriarchal views on gender. Furthermore, culturally specific views on communication with care providers were a common topic. Some patients from certain ethnic backgrounds may subsequently be perceived as “theatrical”, “rude”, “demanding”, or “ungrateful” due to their manner of expressing symptoms and feelings. Consequently, shared emotional responses among our participants included frustration and incomprehension, which are likely to influence GPs’ intentions or motivation to include culturally sensitive strategies in their care provision [68, 69]. Moreover, this frustration may lead GPs to rely more frequently on stereotypes, which could pose potential health risks.

Another way of expressing body language, another way of verbalizing. It is perhaps a bit more difficult to get to the heart of the matter. What is it really about? Everything is described with broad gestures and vocabulary. This makes it more challenging and also more dangerous for us, because sometimes you might underestimate it. You might say, ‘it will probably be nothing again.’ That is dangerous. (male GP, 55)

However, opposition to certain cultural values or expectations does not always result in negative emotions such as frustration. We observed variation in our participant group, especially regarding emotional responses when confronted with different cultural values. This significant variation ranged from clear and strong opposition to simple disagreement. GPs who strongly opposed certain values tended to display more negative emotional responses, such as frustration. Conversely, GPs who merely disagreed often acknowledged the cultural determinants of patient expectations and perceptions, similar to their own views. In these instances, GPs appeared better equipped to maintain perspective and engage in self-reflection.

GPs who feel more strongly about their cultural values and identity may experience more frequent conflicts with patients who reject these values. These GPs seem to be more defensive and encounter more difficulties during intercultural consultations, highlighting the importance of cultural awareness and respecting cultural differences [17].

The generated themes of uncertainty and opposition also resulted in apparent relational outcomes. According to our analysis, a major consequence of these barriers is a potential disconnect in the therapeutic relationship. Due to uncertainty and opposition, GPs report finding it increasingly challenging to effectively engage with and motivate patients from different cultural backgrounds. This impedes the establishment of rapport and meaningful connections. Such a disconnect may manifest in suboptimal and inadequately tailored care as interpretations of symptoms diverge and patients’ expectations and beliefs remain unaddressed.

Additionally, opposition to cultural norms might hinder GPs’ motivation or willingness to invest significant effort in motivating patients or connecting with them, conflicting with the essential concept of cultural desire within the framework of cultural sensitive care [14]. This reluctance can further exacerbate the disconnect in the therapeutic relationship, leading to a cycle of miscommunication and misunderstanding. As GPs become less inclined to engage deeply with patients whose cultural norms they oppose, patients may feel undervalued or misunderstood, further diminishing their trust and willingness to engage in the care process. This dynamic impacts the quality of care and has the potential to perpetuate health disparities, as patients from diverse cultural backgrounds may not receive the culturally sensitive care they require.

You first need to know what certain customs are before you can take them into account. But should you take everything into account? That’s the question. Of course, I’m not going to discard myself; I’m not going to wear a burqa [Islamic religious symbol]. If I go to that country and have to work there, and those are the rules, I will follow them. But one cannot expect me to sit behind my desk wearing a headscarf. I think there are some boundaries. (female GP, 51)

Lack of supportive context

Finally, in analyzing the perceived barriers towards culturally sensitive care, we developed two additional themes that further compound the overarching themes of uncertainty and opposition, influencing GPs’ experiences in intercultural encounters: scarcity of resources and lack of intercultural contact.

First, GPs indicated to be profoundly limited by a scarcity of resources, primarily referring to the severe time pressure under which they operate. This issue is exacerbated by a widespread shortage of GPs, as reported by participants, intensifying the challenges encountered in delivering culturally sensitive care. Cultural sensitivity requires additional “time and energy”, resources often lacking in general practice. Operating under time constraints, GPs have reduced opportunities to thoroughly assess patients’ needs and may opt for expedited medical interventions, explanations and treatments. This is particularly problematic when uncertainty regarding cultural expectations or opposition to cultural preferences impede GPs from being patient-centered and involving patients in decision-making processes. Consequently, patients are particularly vulnerable to receiving suboptimal care in this time-constrained environment, especially when cultural sensitivity is integral to their treatment.

Financial considerations also play a role in this theme. Efforts to foster cultural sensitivity were perceived as “not profitable” by some GPs who struggle in dedicating requisite time to patients without financial losses. There exists a clear distinction between GPs operating within a fee-for-service or a capitation financing system. In a fee-for-service model, GPs are compensated per consultation, whereas in a capitation model, GPs receive a fixed monthly payment per registered patient. It was contended that within a capitation model, GPs can more readily allocate time and effort towards cultivating cultural sensitivity, as this does not impinge upon their financial incentives. Conversely, in the fee-for-service system, financial constraints hinder delivering culturally sensitive care, as additional time and effort are not compensated.

And that also comes back to, yeah, if you have more of a psychological case that requires more time or, you know, communication is more difficult with a patient, that you have to allocate more time for that. That can happen, more [in a capitation system]- Well, in a fee-for-service practice you’ll do that too, but you won’t be reimbursed for it. If I have a psychological conversation for 40 minutes versus a regular consultation. Yeah, then I just earned half as much because I made the time for it. Versus a capitation practice, yeah, it’s a bit like the heavier your profile, the more money you get from the government. Which I find a slightly more logical system. (female GP, 28)

Second, we created the theme lack of intercultural contact as a structural element, increasing both feelings of uncertainty and opposition.

Yes, a doctor in, um, [rural town] who sees 89% local [ethnic majority] West-Flemish patients will have certain [ethnic] groups less in mind and will also be less able to take them into account. (male GP, 29)

The participant group often referred to the location of their practice when discussing cultural sensitivity, suggesting that if they rarely encounter patients from diverse ethnic backgrounds, they are less knowledgeable about the impact of culture on health and culturally sensitive practices. These GPs are less often required to think about culture or cultural sensitivity. We interpret these limited encounters as a potential predictor of both uncertainty and opposition.

For instance, GPs who indicate they rarely encounter patients with a migration background, which they typically attribute to their rural practice locations, deem knowledge about other cultures unnecessary and are less inclined to invest additional time and energy in enhancing their cultural sensitivity. They perceive these strategies as relevant to only a small subset of their patients. In contrast, GPs practicing in urban areas more frequently consult with patients from diverse ethnic backgrounds, which may foster greater understanding and rapport with these patients.

However, we argue that a perceived lack of intercultural contact may significantly contribute to uncertainty. Limited exposure to diverse cultures can lead to greater uncertainty about appropriate care approaches and reluctance to explore culturally specific expectations, preferences, or sensitivities.

We are also individuals, not robots. Naturally, we are shaped by our past experiences. That’s why I say: if you are in the countryside and never encounter Muslim women or veiled women, and suddenly you do, you might rely more on societal assumptions rather than your own experiences. In contrast, if you frequently deal with a lot of diversity, you may find it easier to handle. I don’t know. I work with refugees, and I can imagine other doctors might have a different perspective than mine. Doctors who do not work in a refugee center may have a different view of what makes these people different. (male GP, 37)

Moreover, this limited ability or willingness to explore patients’ cultural needs, coupled with reduced knowledge of how to do so, may lead these GPs to oppose certain cultural values different from their own. They might perceive divergent values as fundamentally different, failing to recognize that they themselves also hold cultural values and views. This lack of critical reflection and intercultural engagement can perpetuate a cycle of uncertainty and opposition, hindering the provision of culturally sensitive care [70–72].

Facilitators

To address the perceived barriers, participants discussed several facilitators and strategies that could mitigate, or at least partially address, these challenges and facilitate the provision of culturally sensitive care. These topics and subsequent themes we developed are categorized across two domains: structural components and individual strategies.

Structural components

Given that, similar to previous findings [43, 47], language barriers were considered the most prominent and challenging obstacle to culturally sensitive care, much discussion revolved around the use of interpreters. We classified the use of interpreters by GPs as a structural factor since the availability and use of interpreters typically depend on healthcare policies, institutional support, and resource allocation rather than solely on individual initiatives by GPs.

In consultations lacking a shared language between patient and provider, employing an interpreter is perceived by multiple participants as “indispensable”. Effective communication and comprehension are paramount, particularly when conveying crucial messages or medical advice.

The appointment of interpreters you can rely on if you encounter such a problem. I think that’s very important. Through a good interpreter with good communication skills and empathy, you will strengthen the trust bond, which will later enable you to establish a good doctor-patient relationship. (female GP, 39)

However, participants discussed substantial distinctions between employing professional interpreters—individuals trained in the process of interpreting—and informal interpreters, such as patients’ family members or acquaintances lacking formal training in interpreting, both types presenting unique advantages and disadvantages in line with the literature [24, 73, 74].

According to our respondents, professional interpreters offer the advantage of professionalism and competence, ensuring confidentiality and reducing emotional bias. Consequently, we noticed how GPs’ uncertainty in consultations with a language barrier is replaced by what we developed as the recurring theme of confidence. GPs share an underlying sense of confidence when they feel assured that all conveyed information will be accurately translated and patients’ feelings, thoughts, and expectations will be effectively communicated. As a result, GPs are more confident in employing communication models and in patients’ ability to understand and adhere to referrals.

Nevertheless, GPs also indicate the considerable logistical challenges in using professional interpreters, including scheduling difficulties and predicting when interpreters will be needed. Late-running consultations and cancellations add to the complexity, and the diverse linguistic needs of patients require multiple interpreters proficient in many languages.

Thus, some structural facilitators of culturally sensitive care inadvertently create additional barriers, aligning with the previously established barrier of resource scarcity and further complicating the provision of culturally sensitive care.

Calling someone ‘on the spot’, a video interpreter or telephone interpreter who is immediately available, I don’t see that happening right away. And besides, that still doesn’t mean there are no barriers for the patient. If they then get someone on the phone, they don’t know who it is, who’s listening in. I wouldn’t assume they have fewer barriers than if they call someone themselves, who they choose themselves. (male GP, 28)

Oppositely, informal interpreters were often considered significantly more convenient in practical terms. These interpreters are familiar to the patient, fostering a sense of trust that may reduce barriers compared to interactions with unfamiliar professional interpreters. However, GPs explained how relying on informal interpreters can also present significant challenges, particularly when conversations involve difficult, sensitive, or intimate subjects. GPs’ uncertainty may resurface in these instances, as they question the effective translation of information due to the emotional weight such discussions impose on both patient and interpreter.

Moreover, participants highlighted general challenges associated with using interpreting services in general practice. Consultations involving interpreters demand more time, and intimate discussions remain challenging, regardless of which type of interpreter. Some GPs also stated how interpreters, particularly those sharing a similar cultural background as the patient, might unintentionally introduce personal or cultural biases, complicating sensitive or taboo conversations, and some patients may hesitate to disclose personal matters through an intermediary, eroding the confidence GPs gain from using interpreters and opposing the expected neutral role of professional interpreters as impartial information conduits [75, 76]. Additionally, employing interpreters often results in a loss of nuance and sensitivity, making it harder to display empathy or motivate patients. GPs cannot always verify the accuracy of translations, which undermines confidence in communication and increases uncertainty. Furthermore, the relational bond between GP and patient may be compromised, leading GPs to ask fewer questions and engage less in exploring patients’ emotional states, restricting consultations to purely clinical discussions.

We are fortunate that with our Ukrainians, someone always comes along who translates. But you never know how accurately they translate, since it’s not official, but it’s someone I trust. [The accuracy] is always a bit missing. I find it very unfortunate because many nuances are lost if you don’t speak the same language or if there has to be an intermediary. Unfortunately, I don’t have a good solution. It’s always a combination of what you have at hand, which is often Google Translate, gestures, and using a website, or hoping there’s someone who can translate. (male GP, 27)

Hence, several GPs frequently opt to utilize online translation services, such as Google Translate, to address language barriers. While such resources offer partial assistance, participants acknowledged these services to be less than ideal but viable when no alternatives are available. The appeal lies in their simplicity, extensive language support, and immediate accessibility. These tools are seen as an easy way to reduce GPs’ uncertainty and increase confidence that patients understand some information. Nevertheless, for complex or psychological consultations, these tools remain insufficient.

Other than the use of interpreters, participants discussed several topics related to patient education and adaptations expected of patients. For example, GPs emphasized the importance of familiarizing patients with the primary healthcare system, including consultation procedures, the utilization of the Calgary Cambridge consultation model and the role of the GP. Additionally, GPs highlighted the necessity of enhancing patients’ understanding of medication usage, particularly antibiotics. Given the disparity between patient expectations and GPs’ norms, there appeared to be a recognized need to align patients’ expectations with clinical realities. Consequently, GPs advocated for initiatives aimed at modifying patients’ general expectations to align them with professional standards.

GPs propose disseminating materials within GP practices, such as posters, flyers, or campaigns, ideally available in patients’ respective languages to achieve these educational objectives.

Making communication materials available is certainly beneficial. Such a communication tool is definitely helpful because, as I mentioned, it rationalizes or nuances the information they have received in their country, which we assume is incorrect according to our Western science. We, as healthcare providers, can certainly use that. Platforms where the available information for Dutch-speaking people is also available in other languages or at least links to other languages. And which are reliable. (male GP, 37)

According to our analysis, however, a common underlying meaning exists in GPs’ responses, from which we generated the theme patient assimilation. Within this theme, GPs highlighted the importance of patient adjustments to enable GPs to deliver culturally sensitive care effectively. This includes patients “actually making a real effort themselves to remove barriers”, particularly regarding the acquisition or improvement of language skills by patients to enhance the quality of care they receive. The promotion of language proficiency among ethnic minority groups, encouraged by GPs during consultations and through broader societal initiatives, may then signify an important step towards fostering stronger connections and patient-provider relationships, according to our participants.

In addition, specific cultural values held by certain patients or patient groups were discussed within this theme. The implicit assumption or expectation appears to be that patients would, albeit gradually, adapt to certain local or Western values, aligning with the earlier theme of opposition. For example, patriarchal gender norms, which contrast with GPs’ self-reported emancipatory views, were explicitly mentioned as values that should be abandoned. Less apparent topics also emerged within this theme, such as differing views on healing and medicine or religion. This is illustrated by a participant’s positive reception of a patient who chose to no longer wear a religious symbol, which was interpreted by the GP as a sign of the patient’s evolving comfort and openness within the clinical setting.

Like that one woman who came veiled the first time, the third time she came without a veil. Apparently, she felt comfortable enough not to have to hide anymore, yeah, actually, she comes regularly now, she also has a child who comes regularly now. I think if you… how should I say… respect their… boundaries, they will automatically start to expand or become more flexible in them. (male GP, 64)

Notably, the two primary themes of confidence and assimilation primarily pertain to patients’ limited language proficiency. The confidence theme highlights the importance of effective communication, enhanced by interpreters and language-support mechanisms. The assimilation theme underscores the expectation, albeit largely implicit, that patients adapt to the healthcare system’s linguistic and cultural norms. Thus, addressing language barriers seems to be crucial for providing culturally sensitive care. Efforts should focus on integrating interpreter services and patient education initiatives to bridge linguistic divides and foster a more inclusive healthcare environment.

In addition to these central components, GPs highlighted the need for additional time and financial resources, although they expressed skepticism about the feasibility of such measures. They noted that longer consultations, however necessary for cultural sensitivity, often lead to financial losses in fee-for-service systems. To address this, GPs advocated for better reimbursement for challenging consultations and preferred capitation systems. They also valued practice adaptations, such as dedicated administrative support, culturally diverse staff, and intercultural mediators, to enhance care.

Individual GP strategies

Finally, GPs discussed several strategies they can implement to help overcome their perceived barriers to culturally sensitive care. These strategies either reflect assumptions about their effectiveness or are based on positive experiences. Engagement and connection are the two main, underlying themes generated in this context.

A significant portion of the discussions regarding potential facilitators focused on communication strategies. GPs emphasized the importance of active and attentive listening, employing conversational techniques to ascertain patients’ cultural needs and expectations, involving patients in decision-making, and addressing potential challenges associated with cultural elements in treatment. Additionally, GPs stressed the significance of ensuring clear communication and understanding, while also discerning subtle non-verbal cues and interpreting them appropriately.

I think it’s mainly about listening carefully. What they think about it, how they act, what their ideas are, how they practice… For example, to stick with nutrition: what they eat. And then try, how should I put it, to gain an understanding of it myself, because I don’t know it myself. (female GP, 49)

Moreover, several GPs occasionally acknowledged their role in overcoming language barriers by employing strategies such as simplifying language, speaking slowly and clearly, allocating more time, and regularly verifying patient understanding. Non-verbal cues and supporting visual aids, like illustrations and multilingual tools, are particularly important when language barriers are present and, consequently, frequently utilized by the majority of participating GPs. Notably, one GP mentioned learning Arabic himself as a proactive measure to enhance communication capabilities with a frequently encountered patient population. However, most GPs reported relying on strategies that align with the concept of “getting by” as commonly described in the literature [77], regardless of potential negative implications on quality of care.

When mentioning these strategies to provide culturally sensitive care, we found that GPs often displayed a shared, underlying theme of engagement. Engagement with patients from diverse ethnic backgrounds is a critical pillar of cultural sensitivity, as Teal and Street [70] suggested. Through active listening, effective verbal and non-verbal skills and openness to and recognition of potential cultural differences, GPs can engage with each patient as an individual, involving them in the consultation and decision-making processes, combining patient-centeredness with cultural sensitivity.

This theme of engagement also encompasses elements of cultural empathy and self-awareness, which arose in our data as well. Some GPs demonstrated how this involves recognizing how a patient’s cultural frame of reference can shape their expectations and needs, and an awareness of providers’ own cultural perspectives and potential biases. Not all GPs exhibited this level of self-awareness, but those who did acknowledged the importance of being aware of their own cultural assumptions and stereotypes—explicit or implicit—and the need for continuous reflection on these perspectives.

I believe that as a physician, you should be aware that sometimes you don’t present all options, some physicians certainly don’t, due to those presumed cultural differences, but also diversity in general. It could even be gender differences, anything really. All of that influences what you propose as a diagnosis and the ultimate goal, which is a treatment plan. If you are aware of those differences, I think you can more easily present them to a patient, and then the patient can indicate themselves. It may be that I am assuming wrongly that a veiled woman has a problem with a man conducting a genital examination. It may be that this is not the case at all. If I don’t present that option to the patient, she won’t be able to choose it either. (male GP, 37)

When GPs demonstrate engagement, they often seem to exhibit greater confidence and less uncertainty. Understanding and addressing patients’ cultural contexts not only facilitates effective communication but by engaging with patients GPs are also better equipped to provide culturally sensitive and individualized treatment plans.

I think so. That you have a sense of how those people are, where you should focus, personal things. I also try to know the names well. They find that very important. That they are addressed, get a personal touch. That you communicate a little. (male GP, 62)

When GPs effectively engage with patients from diverse backgrounds and engage these patients in the communication and care process, this may lead to the second theme we developed: the establishment of connection. Participants frequently mentioned the importance of connection and trust and how establishing a solid patient-provider relationship plays a pivotal role in providing culturally sensitive care. Fostering a welcoming environment, giving consultations a personal touch, remembering patients’ names, and demonstrating a sincere interest in patients’ lives, families and communities are important tools for establishing this connection. Also, similar to the theme of engagement, active and attentive listening is essential in achieving this relationship.

Establishing a strong connection between patient and provider might enable a deeper understanding of patients’ cultural expectations and sensitivities, thereby facilitating patient engagement and, consequently, the customization of culturally sensitive care delivery.

Yes, I think understanding the other culture already creates a sort of connection, which helps you understand that sometimes it may not be possible to conduct [a certain] examination. (female GP, 39)

Moreover, the establishment of such relationships may serve to disperse stereotypes, as GPs are allowed to perceive “the individual within the group”, recognizing the unique identities and perspectives of patients, rather than aggregating them into broader ethnic or cultural categories.

I find that very important myself. To always test the assumptions I have. Not just assuming, ‘she’s a Muslim woman, I assume she wants to see a female gynecologist, so I’ll refer her to a female gynecologist without asking’ that’s definitely important to me, to test everything I assume: ‘is that correct, should I take that into account?‘ (female GP, 39)

Feelings of connectedness may finally have the potential to motivate GPs to increase their efforts in overcoming previous barriers, such as the GPs’ uncertainty and potential opposition to certain cultural values, or the emotional responses these barriers instill, and striving to provide culturally sensitive care.

I often invest a lot of time and effort into that, and sometimes it can be frustrating, but sometimes it can also yield results. (male GP, 27)

Lastly, corresponding to the barrier GPs identified concerning their perceived lack of knowledge and familiarity with culturally divergent values, amplifying their underlying uncertainty, multiple GPs referred to increasing their intercultural knowledge as a pivotal strategy in mitigating the barriers towards culturally sensitive care.

Participants explained the potential benefits of enhancing their ability to navigate and respond to patients’ cultural differences if they understand where culturally specific expectations and needs originate from. This expanded knowledge, they argued, would enable GPs to better interpret behaviors, such as how distinct ethnic groups perceive and interpret health and illness, express symptoms, and prioritize specific pathologies. GPs underscored the importance of intercultural knowledge in understanding cultural perceptions regarding health, emphasizing the necessity of familiarizing themselves with culturally specific customs, habits, and sensitivities to effectively accommodate them in care provision, whilst still cautioning against the use of stereotypes.

If you understand those differences, that context, it makes such a significant impact because otherwise, we very easily encounter misunderstandings, as you don’t quite know why they are acting in a certain way. But if you know [those differences], it makes a big difference. (male GP, 27)

The significance of acquiring knowledge and familiarity with these variations is further underscored by the subsequent decreased uncertainty and increased ability to engage with patients and establish genuine connections, potentially diminishing opposition and facilitating the customization of care.

Participants stressed the necessity of integrating discussions on culture and diversity into the formal medical curriculum, alongside continuous supplementary training. Some GPs additionally noted the value of collaborative discourse with colleagues on complex cases involving cultural disparities, which could serve to ascertain further intercultural knowledge. Also, some participants advocated for the inclusion of experiential learning opportunities in intercultural settings as a beneficial addition to medical education.

If you encounter something, you learn a great deal from it, it sticks with you. It’s about constantly updating and refining that knowledge. (female GP, 53)

General discussion

Main results

This study aimed to explore GPs’ perceived barriers to providing culturally sensitive care and identify potential facilitators or strategies that may assist in overcoming these barriers. We developed themes that elucidate participants’ shared, underlying meanings by employing Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis [55–57]. Our analysis generated two core themes regarding perceived barriers: GPs’ uncertainty and opposition. These core elements subsequently gave rise to themes related to GPs’ emotional responses—mainly consisting of frustration, miscomprehension, and feelings of helplessness—and relational outcomes, primarily involving a disconnect with patients and reluctance and decreased motivation to be culturally sensitive. Additionally, the core themes are compounded by the scarcity of resources inherent to general practice and GPs’ lack of intercultural contact. However, GPs also discussed potential facilitators, categorized into structural elements—such as the use of interpreters, which seemed to instill some sense of confidence in GPs, alongside required or expected patient assimilation—and individual strategies, which revolved around engagement and connection with patients.

These developed themes seem to be intricately connected, reinforcing and amplifying one another. This interconnectedness suggests that addressing one aspect, in particular the core themes of GPs’ uncertainty and opposition, could alleviate related issues, promoting a comprehensive approach to overcoming barriers in culturally sensitive care.

Moreover, these themes appear to be related to a dominant meta-theme. The barriers discussed by participants, and the subsequent themes derived from these discussions, reflect a pervasive lack of control. This sentiment is particularly evident in GPs’ feelings of uncertainty and opposition, where they perceive themselves as powerless in comprehending and effectively addressing patients’ cultural needs. For instance, GPs often feel they have no control over patients’ limited proficiency in a shared language or the resulting impact on the care process, especially when constrained by resource scarcity. Additionally, some of the facilitators and strategies discussed by GPs signify attempts to regain control. Strategies such as utilizing interpreters and engaging more deeply with patients are intended to enhance GPs’ sense of control during consultations, thereby improving their capacity to deliver culturally sensitive care.

This dynamic may also partly explain GPs’ skepticism regarding structural barriers and facilitators and their perceived motivation and optimism towards individual strategies. GPs experience less control over facilitators within the structural domain, whereas they have greater influence over strategies they can personally implement.

Although the sense of control among GPs in cross-cultural care is an underexplored area, previous studies have highlighted its significance for GPs’ well-being and suggested that it can be enhanced through improved communication and relationship skills [78]. This further underscores the importance of incorporating intercultural communication skills in educational initiatives [24]. By doing so, healthcare professionals may experience an increased sense of control in intercultural care encounters, which can lead to improved well-being and enhanced cultural sensitivity [78, 79].

However, our findings also raise several notable issues regarding GPs’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators to culturally sensitive care. GPs often emphasize the importance of cultural knowledge, identifying its absence as a barrier and its acquisition as a facilitator of cultural sensitivity. However, this emphasis on cultural knowledge does not necessarily result in increased cultural sensitivity [21, 80, 81]. This perspective may inadvertently contribute to stereotyping and processes of othering [82], in which challenges are primarily attributed to cultural differences, rather than prompting GPs to reflect on their own cultural values, biases; on the heterogeneity within patient groups from similar ethnic backgrounds and on the intrinsic dynamic aspects of culture. Therefore, consistent with Claeys et al. [80, 83], our findings underscore the issue and persistence of othering, where interacting with ‘the other’ is regularly perceived as more problematic and challenging.

Furthermore, the reported need for patient adaptations or assimilation contributes to ongoing debates about the allocation of responsibility for cultural sensitivity in general practice [28, 84]. While responsibility for cultural sensitivity is multidimensional, healthcare professionals bear both legal and moral obligations to ensure clear communication and provide equitable care [28, 85]. However, expecting patients to assimilate contradicts core principles of culturally sensitive care, such as the appreciation of diverse cultures and the genuine motivation to understand and learn from a variety of patient populations within a patient-centered framework [14, 16]. This calls into question the intrinsic motivation of GPs to deliver culturally sensitive care and suggests a need for a stronger focus on attitudinal change. For instance, incorporating patient experiences into educational initiatives has been previously identified as effective [86, 87] and may be a crucial strategy for fostering such change.

Therefore, to enhance equity and cultural sensitivity in general practice, it may prove essential to prioritize efforts that foster attitudinal change among GPs, along with providing organizational support that fosters a culture of openness to diversity.

Additionally, GPs seem to exhibit a keen awareness of strategies to mitigate barriers to cultural sensitivity and potential biases. They identified methods aligned with recognized solutions and theoretical frameworks in the literature as effective for facilitating culturally sensitive care, such as exploring and acknowledging patients’ cultural contexts [24, 30], engaging in reflective practice [72], and emphasizing continuous diversity-related education [27, 37]. Despite this awareness, persistent challenges remain in everyday practice, likely due to structural impediments. Therefore, it is crucial to continue educating GPs on cultural sensitivity and to advocate for clear policy changes that address these structural barriers. Linking culturally sensitive care to quality care financial incentives could further motivate GPs to adopt these practices.

Strengths and limitations

A notable strength of this study is its use of reflexive thematic analysis, which facilitated the development of latent themes whilst also incorporating participants’ discussions of more explicit topics, providing a comprehensive understanding of the data. The diverse composition of participants, including GPs with varying levels of experience and cultural sensitivity, enabled the collection of rich data. The richness and nuance within our data and results were further amplified by our continuous analytical process, involving reflection on our data, interpretations and themes. This qualitative collaboration involved all authors, each experienced in various subfields of healthcare or qualitative research methodology.

However, the study has limitations. The self-reported nature of the data may introduce bias, as GPs might underreport or overemphasize certain barriers or facilitators. Additionally, incorporating patients’ perspectives through triangulation would have enriched this study [88]. The specific context of our participant group, all active in Flanders, may have influenced our findings; different contexts, such as primary healthcare organizations or predominant ethnicities in other regions, may yield different conclusions. Moreover, since the participants were involved in a previous study conducted by our research team, this prior involvement may have induced an awareness on the topic and influenced their responses in this study, potentially introducing a bias in how they perceived and reported barriers and facilitators. Finally, our research team is comprised exclusively of ethnic majority Flemish researchers. In the context of research on diversity, culture, and equity, a more diverse team would have benefitted this study [89].

Future research directions

Future research should investigate the effectiveness of the identified strategies and facilitators in practice, focusing on real-life intercultural health encounters and evaluating their impact on patient and GP outcomes. Exploring the effectiveness of training interventions to address the latent themes identified in GPs, specifically decreasing their uncertainty and opposition while increasing their confidence and sense of control, would also be a valuable research direction. Additionally, studies should examine the role and, more importantly, feasibility of structural interventions, such as policy changes and resource allocation, in mitigating the identified barriers.

Comparative studies across different geographical regions can provide valuable insights into the universal and context-specific challenges of culturally sensitive care, thereby informing the development of more effective, globally applicable strategies.

Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive overview of GPs’ perceived barriers to culturally sensitive care in the Flemish context and highlights the potential facilitators and strategies identified by GPs to overcome these barriers. By developing interconnected themes— such as GPs’ uncertainty and opposition, their engagement and connection with patients, and a meta-theme of control —our findings provide nuanced insights into the complexities of culturally sensitive care. Emphasizing the critical need for tailored training, the importance of fostering genuine engagement, connection, and collaboration with patients, and the role of critical self-assessment, our findings contribute to ongoing efforts to enhance cultural sensitivity in general practice. This study offers valuable insights for practitioners, policymakers, and educators striving to improve culturally sensitive care practices.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to all the general practitioners who participated in this study and shared their invaluable insights. We also acknowledge the support of the healthcare institutions and organizations that facilitated this research. Special thanks to Eva Gezels for her assistance in creating and visualizing the thematic map, which greatly enhanced the clarity and depth of our analysis. Lastly, we thank our funding agencies and administrative staff for their support throughout this project.

Abbreviations

- GP

General Practitioner

Author contributions

RV, LR, SW and SDM were responsible for study conception and design, with RV primarily leading the data extraction process, while RV, LR and PS jointly conducted data analysis frequently consulting with SW and SDM. Drafting the manuscript was completed by RV. All authors contributed significantly to the interpretation of data and provided valuable input during the manuscript revision process. SW and PS were responsible for securing funding for the study. All authors have viewed and approved the current version for submission.

Funding

The present study is part of the EdisTools project, funded by Research Foundation-Flanders (Strategic Basic Research – S004119N). The funding source had no involvement in study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the paper and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study received ethics approval from the Commission for Medical Ethics, UZ Gent: BC-08924. All participants explicitly provided informed consent to participate in the study and to publishment of deidentified data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Napier AD, Ancarno C, Butler B, Calabrese J, Chater A, Chatterjee H, et al. Culture and health. Lancet. 2014;384(9954):1607–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drewniak D, Krones T, Sauer C, Wild V. The influence of patients’ immigration background and residence permit status on treatment decisions in health care. Results of a factorial survey among general practitioners in Switzerland. Soc Sci Med. 2016;161:64–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lorant V, Van Oyen H, Thomas I. Contextual factors and immigrants’ health status: double jeopardy. Health Place. 2008;14(4):678–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paternotte E, Scheele F, Seeleman CM, Bank L, Scherpbier AJ, van Dulmen S. Intercultural doctor-patient communication in daily outpatient care: relevant communication skills. Perspect Med Educ. 2016;5:268–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson A. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(8):666. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(6):813–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Ryn M, Burgess D, Malat J, Griffin J. Physicians’ perceptions of patients’ social and behavioral characteristics and race disparities in treatment recommendations for men with coronary artery disease. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(2):351–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffith DM, Efird CR, Baskin ML, Webb Hooper M, Davis RE, Resnicow K. Cultural sensitivity and cultural tailoring: lessons learned and refinements after two decades of incorporating culture in health communication research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2024;45(1):195–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brach C, Fraserirector I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Med care Res Rev. 2000;57(1suppl):181–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egede LE. Race, ethnicity, culture, and disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alhomoud F, Dhillon S, Aslanpour Z, Smith F. Medicine use and medicine-related problems experienced by ethnic minority patients in the United Kingdom: a review. Int J Pharm Pract. 2013;21(5):277–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleinman A, Benson P. Anthropology in the clinic: the problem of cultural competency and how to fix it. Understanding and applying medical anthropology. 2016:344-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Rocque R, Leanza Y. A systematic review of patients’ experiences in communicating with primary care physicians: intercultural encounters and a balance between vulnerability and integrity. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(10):e0139577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campinha-Bacote J. The process of cultural competence in the delivery of healthcare services: a model of care. J Transcult Nurs. 2002;13(3):181–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE. Cultural competence in health care: emerging frameworks and practical approaches: Commonwealth Fund. Quality of Care for Underserved Populations New York, NY; 2002.

- 16.Stubbe DE. Practicing cultural competence and cultural humility in the care of diverse patients. Focus. 2020;18(1):49–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henderson S, Horne M, Hills R, Kendall E. Cultural competence in healthcare in the community: a concept analysis. Health Soc Care Commun. 2018;26(4):590–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Handtke O, Schilgen B, Mösko M. Culturally competent healthcare–A scoping review of strategies implemented in healthcare organizations and a model of culturally competent healthcare provision. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(7):e0219971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horvat L, Horey D, Romios P, Kis-Rigo J. Cultural competence education for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Reviews. 2014(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]