Abstract

Spinal cord injury (SCI) often accompanies impairment of motor function, yet there is currently no highly effective treatment method specifically for this condition. Oxidative stress and inflammation are pivotal factors contributing to severe neurological deficits after SCI. In this study, a type of curcumin (Cur) nanoparticle (HA-CurNPs) was developed to address this challenge by alleviating oxidative stress and inflammation. Through non-covalent interactions, curcumin (Cur) and poly (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (pEGCG) are co-encapsulated within hyaluronic acid (HA), resulting in nanoparticles termed HA-CurNPs. These nanoparticles gradually release curcumin and pEGCG at the SCI site. The released pEGCG and curcumin not only scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) and prevents apoptosis, thereby improving the neuronal microenvironment, but also regulate CD74 to promote microglial polarization toward an M2 phenotype, and inhibits M1 polarization, thereby suppressing the inflammatory response and fostering neuronal regeneration. Moreover, in vivo experiments on SCI mice demonstrate that HA-CurNPs effectively protect neuronal cells and myelin, reduce glial scar formation, thereby facilitating the repair of damaged spinal cord tissues, restoring electrical signaling at the injury site, and improving motor functions. Overall, this study demonstrates that HA-CurNPs significantly reduce oxidative stress and inflammation following SCI, markedly improving motor function in SCI mice. This provides a promising therapeutic approach for the treatment of SCI.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12951-024-02916-4.

Keywords: SCI, ROS, Curcumin, Mice, CD74

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a central nervous system disorder characterized by diminished motor and sensory functions following neural damage. Currently, no effective treatments are available, imposing significant psychological and economic burdens on patients [1, 2]. Based on SCI pathophysiology, it is categorized into primary and secondary injuries [3]. Primary injuries are those resulting from external forces directly, often leading to irreparable damage [4]. Secondary damage comprises a sequence of internal cascades set off by the initial damage, such as inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, free radical production, cellular apoptosis, and glial scar formation [5]. Intervening in the biochemical processes during the secondary injury phase can mitigate further damage, protect intact neural tissue, and promote neurological recovery [6]. The substantial production of ROS, leading to oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, is a key characteristic of the secondary injury phase [7], ROS includes superoxide anions, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals. Excessive ROS leads to cellular dysfunction and death [8]. Microglia are critical players in the inflammatory response that occurs after SCI [9], exhibiting two phenotypic states during neuroinflammation [10]. M1 microglia release pro-inflammatory cytokines and mediators, which contribute to neuronal damage, whereas M2 microglia reduce inflammation and facilitate tissue repair through anti-inflammatory cytokines and neurotrophic factors [11]. CD74 is a chaperone protein for major histocompatibility complex class II molecules [12]. CD74 expression is typically increased after SCI, and the regulation of CD74 expression plays a critical role in M1/M2 polarization [13, 14]. Previous studies have shown that after a SCI, M1 microglia dominate and induce inflammation, causing neuronal damage. Enhancing the population of M2 microglia post-injury offers neuroprotection [15]. Therefore, regulating the expression of CD74 and subsequently modulating M1/M2 polarization is crucial for the recovery of SCI. Sustained oxidative stress and inflammatory responses exacerbate neural tissue damage and impede its repair and regeneration [16]. Therefore, eliminating ROS and mitigating inflammatory responses are crucial for spinal cord injury repair. Currently, methylprednisolone, commonly used in clinical settings, improves spinal cord injury by clearing ROS. However, its severe side effects, such as increased infection risk, gastrointestinal reactions, and hyperglycemia, limit its utility [17, 18]. The clinical use of high dose methylprednisolone has become more cautious recently [19]. Therefore, developing a biocompatible drug that efficiently clears ROS is essential for spinal cord injury treatment.

Polyphenols are a class of organic compounds. Their primary biological activity is antioxidant capacity [20, 21]. Curcumin is a natural polyphenolic compound, belonging to the ginger family [22]. Curcumin is highly regarded for its therapeutic potential in treating oxidative stress-related diseases due to its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antitumor. This includes conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease [23], atherosclerosis [24], cancer [25] and spinal cord injuries [26]. Additionally, Curcumin is known for its neuroprotective effects that shield neuronal cells from damage and its capacity to breach the blood-brain barrier [27, 28], These properties make curcumin a promising candidate for treating spinal cord injuries. Despite considerable efforts in research and development, the clinical applications of curcumin are substantially constrained by its low water solubility, stability, and bioavailability [29]. To enhance its solubility and bioavailability, curcumin has been encapsulated in various formulations such as liposomes [30], polymer nanoparticles [31], biodegradable microspheres [32], and hydrogels [33], maximizing its therapeutic efficacy. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) is another polyphenolic compound. It demonstrates multiple biological activities, such as antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, antimicrobial, antiviral, and antitumor properties [34, 35]. However, like curcumin, EGCG is relatively unstable and poorly absorbed, resulting in low bioavailability [36]. The poly (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (pEGCG) formed through the polymerization reaction exhibited better stability and higher bioavailability compared to EGCG. Consequently, the pEGCG can be used as an alternative to the commonly studied EGCG [21]. Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a naturally occurring polymer widely utilized in drug delivery systems owing to its easily modifiable chemical structure, biodegradable and non-toxic properties, and excellent biocompatibility [37, 38]. Hyaluronic acid (HA) targets CD44, a cell molecule widely expressed on leukocytes, the core of this targeted delivery mechanism lies in the specific binding between HA and CD44 [39]. CD44 expression is significantly upregulated at sites of inflammation [40–42], allowing nanoparticles to specifically target these inflamed areas.

In this study, a type of curcumin nanoparticle (HA-CurNPs) was designed and synthesized to function through dual mechanisms: mitigating oxidative stress by scavenging ROS and exerting anti-inflammatory effects by regulating CD74 to promote M2 polarization of microglia, ultimately facilitating spinal cord injury repair (Scheme 1). HA-CurNPs were prepared by non-covalently binding curcumin and pEGCG, followed by encapsulation within HA. Curcumin is a hydrophobic molecule, and its poor water solubility and chemical stability limit its application [43]. However, when combined with pEGCG, curcumin not only exhibits excellent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties but also gains improved water solubility and stability [44]. Finally, the CurNPs are encapsulated by HA, forming a highly stable nanoparticle structure. This encapsulation process not only enhances nanoparticle stability but also improves targeting efficiency [45]. On the one hand, by targeting CD44 to accumulate at the SCI site, the released pEGCG and curcumin can improve the environment around damaged neurons through its antioxidant and anti-apoptotic properties. On the other hand, HA-CurNPs can promote M2 polarization of microglia while inhibiting M1 polarization by regulating CD74, thereby exerting anti-inflammatory effects and promoting neuronal survival and regeneration. Additionally, HA-CurNPs significantly promote neural cell regeneration and reduce glial scar formation while protecting myelin cells and exhibiting good biocompatibility. HA-CurNPs effectively enhance electrophysiological conduction recovery and tissue repair in the damaged spinal cord, facilitating motor function restoration in SCI mice. Therefore, HA-CurNPs represent a safe and effective treatment for spinal cord injuries.

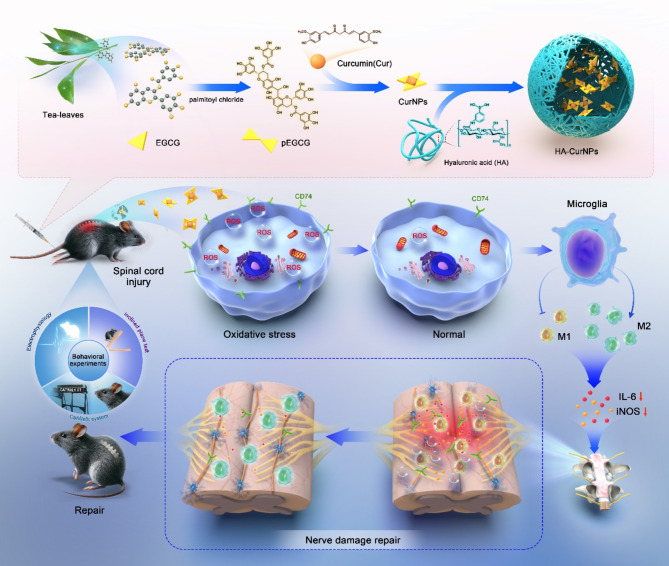

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of the mechanism by which HA-CurNPs promote spinal cord injury repair by alleviating oxidative stress and inflammation

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization of HA-CurNPs

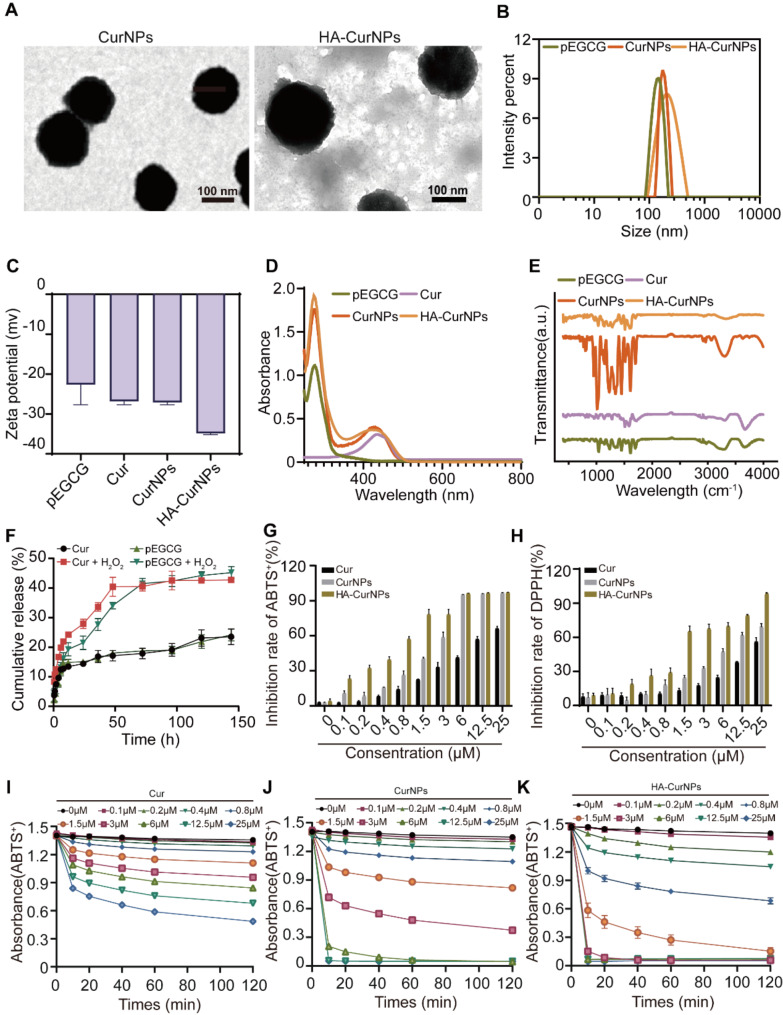

In this research, EGCG was transformed into pEGCG through a polymerization reaction (Fig. S1, S2, S3). Subsequently, the particles formed by the non-covalent interaction between curcumin and pEGCG are referred to as CurNPs. These are encapsulated within hyaluronic acid (HA) to create nanoparticles, named HA-CurNPs. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) showed that CurNPs and HA-CurNPs were uniformly spherical, with average diameter of 157.67 ± 16.87 nm for CurNPs and 217.15 ± 18.68 nm for HA-CurNPs (Fig. 1A), the slightly smaller size of CurNPs compared to HA-CurNPs is mainly because the encapsulation by HA increases the nanoparticle size [46]. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements showed that the average particle size of pEGCG was 148.80 ± 18.37 nm with a PDI of 20.26%; CurNPs had an average particle size of 178.00 ± 16.60 nm with a PDI of 17.40%; and HA-CurNPs had an average particle size of 269.00 ± 31.62 nm with a PDI of 36.11% (Fig. 1B). As shown in Fig. 1C, the progressive reduction in the Zeta potential indicates the successful encapsulation of pEGCG and Cur within HA. A UV-visible spectrophotometer was utilized to measure the absorption spectrum of pEGCG, Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs (Fig. 1D). Characteristic absorption peaks of pEGCG at 280 nm and Cur at 430 nm were observed. HA-CurNPs exhibited characteristic absorption peaks at both 280 nm and 430 nm, indicating the presence of both pEGCG and Cur. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) recorded the spectra (Fig. 1E), showing rich phenolic hydroxyl stretching vibrations near 3400 cm− 1 for pEGCG and C = O stretching vibrations near 1710 cm− 1 for Cur. Both pEGCG and Cur exhibited C = C stretching vibrations in the aromatic ring structures between 1500 cm− 1 and 1600 cm− 1. The FTIR spectrum of HA-CurNPs shared characteristic peaks of pEGCG and Cur and displayed carboxylic (COOH) stretching vibrations in the range of 1600 cm− 1 to 1700 cm− 1, which may shift or change in intensity due to interactions with Cur or pEGCG. To simulate the drug release rate of HA-CurNPs at the spinal cord injury site, their release rate under acidic conditions was measured. As shown in Fig. 1F, the release rate of pEGCG and Cur from HA-CurNPs were significantly increased in acidic conditions, demonstrating pronounced pH-responsive release capabilities. Given the increased local inflammatory response and decreased pH following SCI [47], HA-CurNPs can effectively release curcumin and pEGCG at the site of SCI for therapeutic intervention. Furthermore, to verify the antioxidant effects of HA-CurNPs, their ability to scavenge 2,2′-azinobis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonate (ABTS) radicals was tested extracellularly. At various concentrations, Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs suppressed the formation of ABTS+ radicals in a manner dependent on both dose and concentration, with HA-CurNPs showing stronger scavenging abilities at lower drug concentrations (Fig. 1G, I, J, K). Similarly, the ability of Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs to scavenge 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radicals was tested at different concentrations. HA-CurNPs were more effective than Cur and CurNPs in inhibiting DPPH radical formation at various concentrations (Fig. 1H, S4). This may be attributed to the enhanced drug stability achieved by encapsulating CurNPs in HA, thereby enabling sustained drug release [48]. In summary, HA-CurNPs efficiently neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby preventing neuronal damage induced by oxidative stress.

Fig. 1.

Synthesis and characterization of HA-CurNPs. (A) Representative TEM images of CurNPs and HA-CurNPs (scale bar = 100 nm). (B) Particle size of pEGCG, CurNPs and HA-CurNPs determined using dynamic light scattering (DLS). (C) Zeta potential of pEGCG, Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs. (D) UV-visible absorption spectrum of pEGCG, Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs measured using a UV-visible spectrophotometer. (E) Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) of pEGCG, Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs. (F) The release rates of pEGCG and Cur from HA-CurNPs in environments with and without H₂O₂. (G) Quantitative analysis of the scavenging rate of ABTS+ radicals by Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs. (H) Quantitative analysis of the scavenging rate of DPPH radicals by Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs. (I) Scavenging ability of Cur against reactive oxygen species measured at different concentrations and times through the ABTS+ radical scavenging assay. (J) Scavenging ability of CurNPs against reactive oxygen species measured at different concentrations and times through the ABTS+ radical scavenging assay. (K) Scavenging ability of HA-CurNPs against reactive oxygen species measured at different concentrations and times through the ABTS+ radical scavenging assay

The evaluation of antioxidant activity of HA-CurNPs in vitro and vivo

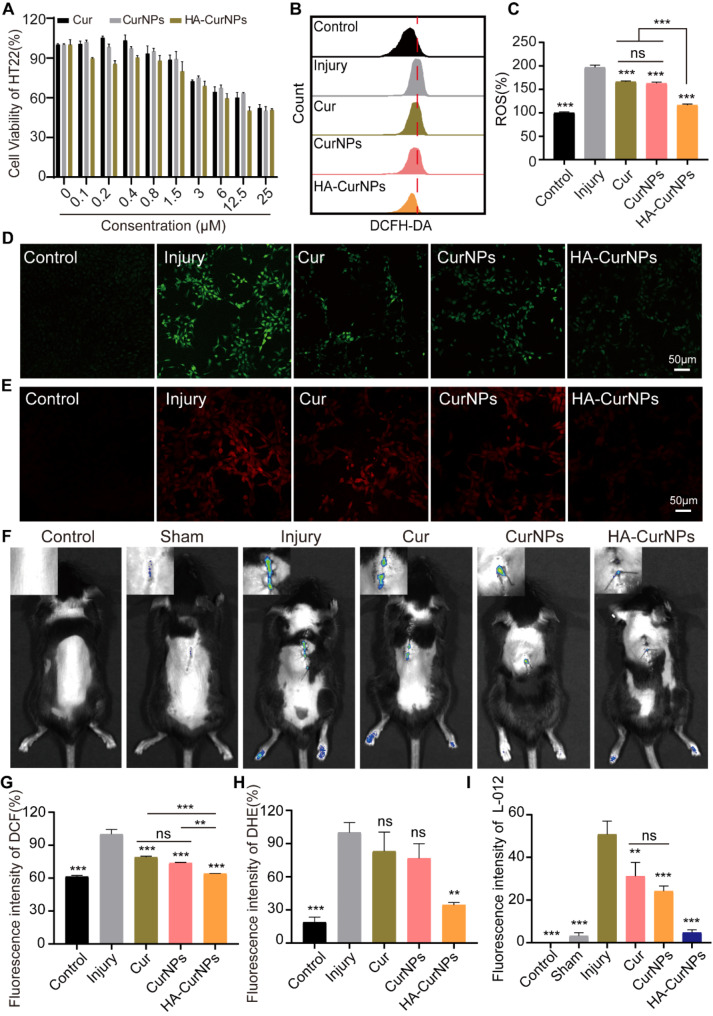

Given the significant ability of HA-CurNPs to scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) in vitro, their potential to clear ROS in vivo was also investigated. To assess the antioxidant activity of HA-CurNPs within cells, toxicity experiments on Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs were conducted using the CCK-8 method on HT22 cells. HT22 cells, a classic model for studying oxidative stress, can be induced into oxidative stress by treating with glutamate [1, 49]. As shown in Fig. 2A, the cytotoxic effects of Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs on HT22 cells were negligible at drug concentrations below 0.8 µM. Therefore, all subsequent experiments involving drug treatment were conducted at a concentration of 0.8 µM. At a drug concentration of 0.8 µM, the ability of Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs to scavenge ROS within HT22 cells was measured. The 2’,7’-dihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) fluorescent probe kit, used to determine intracellular ROS levels, was employed [50]. DCFH-DA is non-fluorescent and can freely cross cell membranes, being hydrolyzed inside the cell to form DCFH, which remains inside because it cannot cross the cell membrane. Intracellular ROS then transforms DCFH, a non-fluorescent molecule, into fluorescent DCF, indicating ROS levels within cells [51]. When HT22 cells were subjected to oxidative stress injury induced by glutamate and co-incubated with Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs for 24 h, flow cytometry revealed that Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs exhibited antioxidant activity. HA-CurNPs showed the strongest antioxidant activity, clearing most ROS and bringing intracellular ROS levels nearly to those observed in the control group (Fig. 2B, C). Intracellular ROS fluorescence analysis (Fig. 2D, G), yielded similar results, showing that HA-CurNPs significantly cleared ROS in HT22 cells induced by glutamate, with better ROS scavenging activity than Cur and CurNPs. Additionally, the dihydroethidium (DHE) kit was used to assess the scavenging activity of Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs against superoxide anions (O2•−), a type of ROS [52]. Dihydroethidium, when taken up by live cells, is dehydrogenated by O2•− within the cell, and the resulting ethidium attaches to RNA or DNA to generate red fluorescence [53]. At the same drug concentration, treatment with Cur and CurNPs did not significantly reduce red fluorescence within cells, but treatment with HA-CurNPs significantly reduced red fluorescence intensity, indicating a reduction in O2•− produced by glutamate induction (Fig. 2E, H). After SCI, a significant quantity of ROS is produced at the injury site [2], Given the excellent antioxidant activity of HA-CurNPs both inside and outside cells, it remains to be seen whether HA-CurNPs can alleviate ROS at the injury site. The L-012 chemiluminescence probe was used to measure ROS production in mice after SCI. After SCI, ROS levels at the injury site in injury group significantly increased than control group. After treatment with Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs, ROS levels decreased to varying degrees, with the HA-CurNPs group showing the most significant decrease in bioluminescence intensity at the same drug concentration, indicating the best treatment effect of HA-CurNPs (Fig. 2F, I). Although the antioxidant capacity of CurNPs is comparable to that of free curcumin, suggesting that the combination of pEGCG and curcumin does not significantly enhance antioxidant activity, this is consistent with previous research findings [26]. However, encapsulating CurNPs in HA to form HA-CurNPs significantly enhances antioxidant activity. Given that HA-CurNPs exhibit stronger antioxidant effects both intracellularly and in vivo, in addition to HA enhancing the stability of nanoparticles, HA also significantly improves the bioavailability of the drug [54]. These results suggest that HA-CurNPs can be used as a ROS scavenger for spinal cord injury repair.

Fig. 2.

Evaluation of the antioxidant stress efficacy of HA-CurNPs. (A) Cytotoxic effects of Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs on HT22 cells. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of the ROS scavenging ability of Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs in cells. (C) Quantitative analysis of ROS levels using flow cytometry (n = 3). (D) Measurement of intracellular ROS levels in cells treated with Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs using DCFH-DA (scale bar = 50 μm). (E) Measurement of intracellular ROS levels in cells treated with Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs using DHE (scale bar = 50 μm). (F) Evaluation of ROS levels at the site of spinal cord injury in mice treated with Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs using the L-012 chemiluminescence probe. (G) Quantitative evaluation of DCF fluorescence intensity in cells from different groups (n = 3). (H) Quantitative evaluation of DHE fluorescence intensity in cells from different groups (n = 3). (I) Quantitative evaluation of ROS fluorescence levels at the site of spinal cord injury in mice treated with Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs. All data are presented as the mean ± SEM (ns, not statistically significant; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 vs. Injury)

Effects of HA-CurNPs on microglial polarization

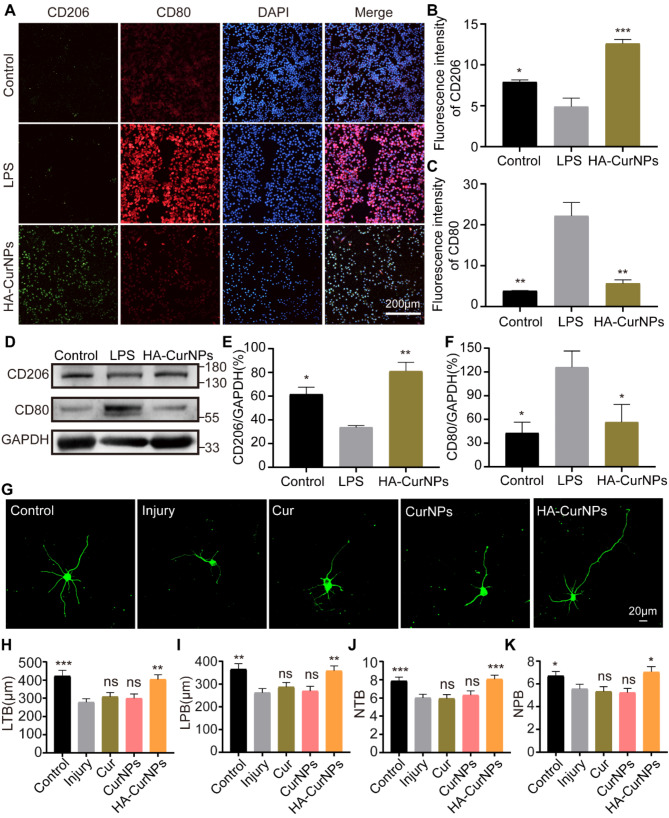

In addition to clearing excessive ROS, enhancing M2 polarization of microglial cells is crucial for SCI repair [15]. Post-SCI, M1 polarized microglia release large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines, exacerbating inflammation and damaging healthy tissue. In contrast, M2 polarized microglia release anti-inflammatory cytokines, inhibiting the inflammatory response and protecting neural tissue [55]. Furthermore, M2 microglia produce various growth factors essential for the survival, regeneration, and axonal growth of damaged neurons [56]. Therefore, the involvement of HA-CurNPs in the polarization process of microglial cells was evaluated. BV2 cells were treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) and co-cultured with HA-CurNPs for 24 h. Immunofluorescence staining was performed using M1 (anti-CD80) and M2 (anti-CD206) microglial markers (Fig. 3A). Results indicated that LPS induction significantly increased CD80 expression and decreased CD206 expression, promoting M1 polarization and inhibiting M2 polarization of microglia, consistent with previous studies [57]. However, treatment with HA-CurNPs markedly increased CD206 expression and decreased CD80 expression, suggesting HA-CurNPs can reverse the effects of LPS by promoting M2 polarization of microglia while inhibiting M1 polarization (Fig. 3B, C). Furthermore, these findings were further validated through western blot analysis, confirming that HA-CurNPs counteract LPS-induced M1 polarization, ultimately promoting M2 polarization of microglia (Fig. 3D, E, F). This conclusion was also validated in vivo. In a mouse model of SCI, HA-CurNPs were administered via tail vein injection once daily for 3 consecutive days following the injury. Immunostaining of the spinal cord injury site revealed a significant presence of M1 microglia post-injury on day 5. However, HA-CurNP treatment significantly promoted M2 microglia formation and inhibited M1 microglia formation (Fig. S5). A favorable microenvironment is crucial for tissue regeneration following SCI [58]. An environment that supports regeneration is often characterized by the response and phenotype of microglia [59]. Additionally, the impact of HA-CurNPs on the expression of inflammatory factors was examined. Findings indicate that HA-CurNPs significantly reduce the expression of IL-6 and iNOS (Fig. S6). These results indicate that HA-CurNPs create a beneficial microenvironment for SCI repair by promoting M2 polarization of microglia and suppressing inflammation.

Fig. 3.

Effects of HA-CurNPs on microglial polarization and injured neuron repair. (A) Immunocytochemistry staining with anti-CD80 and anti-CD206 antibodies was performed to investigate HA-CurNPs’ effects on microglial polarization (scale bar = 200 μm). (B) Quantitative evaluation of CD206 fluorescence intensity in Fig. A (n = 3). (C) Quantitative evaluation of CD80 fluorescence intensity in Fig. A (n = 3). (D) Western blot analysis with anti-CD80 and anti-CD206 antibodies to explore HA-CurNPs’ effects on microglial polarization. (E) Quantitative evaluation of the relative gray value of CD206 in Fig. D (n = 3). (F) Quantitative evaluation of the relative gray value of CD80 in Fig. D (n = 3). (G) Representative images of primary hippocampal neurons after oxidative stress induced by glutamate, treated with Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs in different groups (scale bar = 20 μm). (H) Statistical evaluation of the length of total branches (LTB) in hippocampal neurons (n = 30). (I) Statistical evaluation of the length of primary branches (LPB) in hippocampal neurons (n = 30). (J) Statistical evaluation of the number of total branches (NTB) in hippocampal neurons (n = 30). (K) Statistical evaluation of the number of primary branches (NPB) in hippocampal neurons (n = 30). All data are presented as the mean ± SEM (ns, not statistically significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 vs. LPS/Injury)

Evaluation of HA-CurNPs’ neuroprotective and anti-apoptotic abilities

Promoting neuronal repair is crucial for enhancing SCI recovery. Previous experiments demonstrated that HA-CurNPs exhibit excellent antioxidative stress capabilities and promote M2 polarization while inhibiting M1 polarization of microglia, thereby suppressing inflammatory responses. This led to further investigation into whether HA-CurNPs facilitate the repair of injured neurons. First, the cytotoxicity of Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs on primary hippocampal neurons was assessed using the CCK-8 assay. As shown in Fig. S7, at a concentration of 0.8 µM, Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs exhibited low toxicity, consistent with results observed in HT22 cells. Therefore, glutamate-damaged hippocampal neurons were treated with these compounds at a concentration of 0.8 µM. The results indicated that, compared to the injury group, neurons treated with Cur and CurNPs showed no significant changes in neurite length and branch number. However, with HA-CurNPs intervention, notable increases in total neurite length, primary neurite length, total branch number, and primary branch number were observed, suggesting that HA-CurNPs significantly promote neurite length extension and branch formation in injured neurons (Fig. 3G-K). This effect is attributed to HA-CurNPs’ ROS scavenging activity and ability to promote M2 polarization of microglia. It is noteworthy that, at low concentrations, although Cur and CurNPs have some antioxidant activity, this relatively weak antioxidative stress capability is insufficient to facilitate the repair of damaged neurons. The production of inflammation and ROS is a mutually reinforcing process [60], where excessive ROS and inflammation exacerbate neuronal damage. Conversely, clearing excessive ROS and inhibiting inflammation can significantly promote neurite extension and facilitate neural circuit recovery [61]. Excessive oxidative stress can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction, resulting in neuronal apoptosis [62]. Therefore, flow cytometry was employed to assess the effects of Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs on cell apoptosis. The results indicated that following glutamate induction, the apoptosis rate significantly increased, whereas treatment with Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs reduced apoptosis rates to varying extents, with HA-CurNPs showing the most pronounced effect (Fig. S8). This is consistent with previous results on antioxidative stress. In conclusion, HA-CurNPs demonstrate significant anti-apoptotic properties and the ability to promote injured neuron repair.

Evaluation of HA-CurNPs treatment on motor function recovery in SCI mice

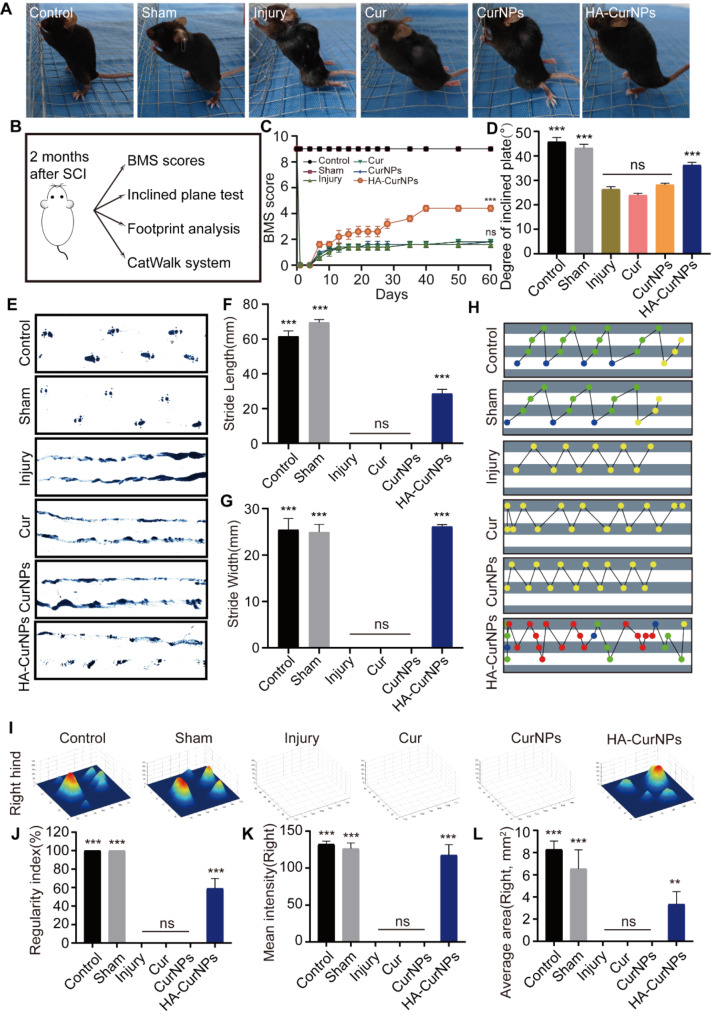

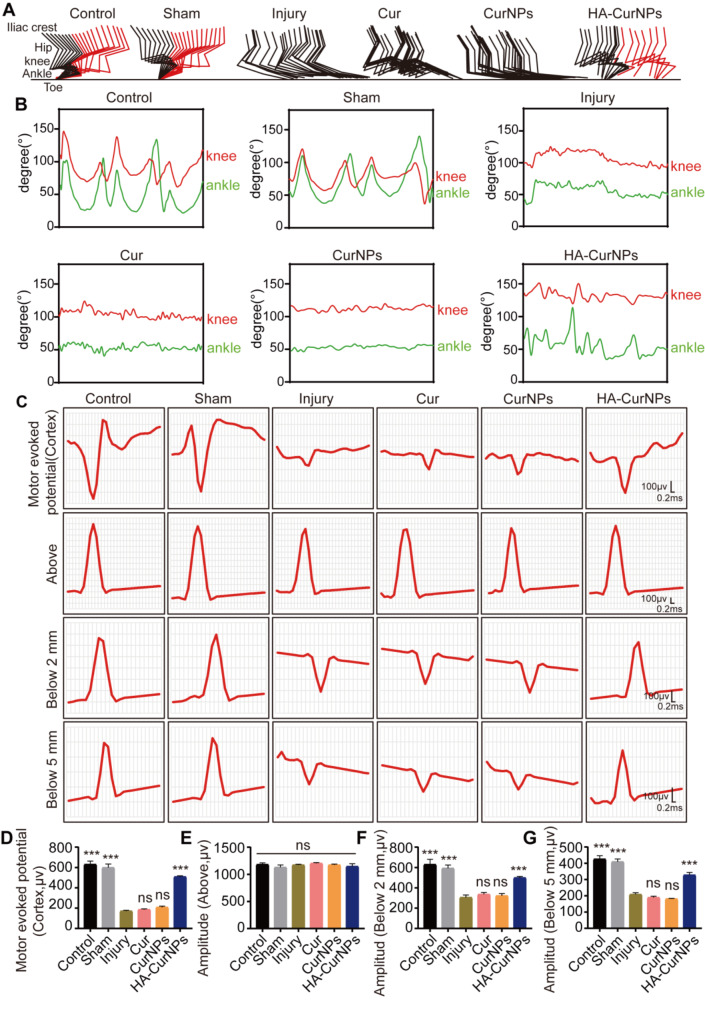

In our study, it was demonstrated that HA-CurNPs protect hippocampal neurons and promote neural circuit formation by scavenging ROS and promoting M2 polarization of microglia in vitro. The subsequent analysis focused on whether HA-CurNPs could improve motor function recovery in SCI mice. Two months after treatment with the same drug concentration, the posture of mice in each group when standing was observed. It was found that mice in the injury, Cur, and CurNPs groups were unable to stand due to poor recovery of hind limb strength. However, the mice in the HA-CurNPs group could stand, although their paw strength was not as strong as in the control and sham groups (Fig. 4A). Motor function of the mice was evaluated through various experimental methods (Fig. 4B). First, hind limb function recovery in SCI mice was evaluated over two months by regularly calculating the BMS score. Results showed that hind limb motor function of SCI mice was completely limited initially. By the 7th day, motor function improved to varying degrees, particularly in the HA-CurNPs group. The BMS score gradually increased, and by the end of two months, scores stabilized. The HA-CurNPs group demonstrated a notable improvement in BMS scores relative to the injury group, while the Cur and CurNPs groups did not show significant differences from the injury group (Fig. 4C). Inclined plane test results indicated that the maximum angle at which SCI mice could maintain balance was significantly reduced. No significant improvement was observed following Cur or CurNPs treatment. However, HA-CurNPs treatment significantly increased the maximum angle, suggesting that HA-CurNPs effectively improved motor function and balance in mice, though not to the levels of the control and sham groups (Fig. 4D). Footprint analysis revealed that mice in the injury, Cur, and CurNPs groups could not effectively form ground contact prints, while the HA-CurNPs group showed significant improvements in stride length and width (Fig. 4E-G). Furthermore, CatWalk system analysis showed a significant improvement in the regularity index of the HA-CurNPs-treated mice compared to the injury group, whereas Cur and CurNPs treatments did not yield significant effects (Fig. 4H, J). The average intensity and area of ground contact for the right hind paw in each group were also analyzed. The HA-CurNPs group showed significant improvements in both parameters compared to the injury group, while the Cur and CurNPs groups did not show notable improvements (Fig. 4I, K, L). Similar conclusions were drawn from the analysis of the left hind paw (Fig. S9). To further assess motor function improvement, joint activity of mice in each group was tracked. Results indicated that mice treated with HA-CurNPs were able to partially support their body weight during walking (Fig. 5A). Analysis of the range of motion of the knee and ankle joints revealed significant improvements in these joints in the HA-CurNPs-treated mice, whereas the Cur and CurNPs-treated mice did not show significant improvements (Fig. 5B). Given that stepping involves rhythmic movement of the lower limbs, including the knee and ankle joints [63], measuring the range of motion of these joints is crucial for evaluating motor function recovery in mice. These findings suggest that although motor function recovery in SCI mice is limited, HA-CurNPs treatment facilitates motor function recovery.

Fig. 4.

Evaluation of HA-CurNPs on motor function recovery in SCI mice. (A) Appearance of mice standing. (B) Methods for evaluating motor function in SCI mice. (C) Changes in BMS scores of SCI mice over two months. (D) Inclined plane test to assess motor ability and balance in SCI mice. (E) Footprint analysis to assess hind limb motor function in mice. (F) Statistical analysis of stride length in (E) (n = 5). (G) Statistical analysis of stride width in (E) (n = 5). (H) CatWalk system analysis of the regularity index of motor function in SCI mice. (I) CatWalk system analysis of the average ground contact intensity and area for the right hind paw in SCI mice. (J) Quantitative evaluation of the regularity index of motor function in SCI mice (n = 5). (K) Quantitative evaluation of the average ground contact intensity for the right hind paw in SCI mice (n = 5). (L) Quantitative evaluation of the average ground contact area for the right hind paw in SCI mice (n = 5). All data are presented as the mean ± SEM (ns, not statistically significant; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 vs. Injury)

Fig. 5.

Evaluation of HA-CurNPs on hind limb joint activity and neural electrical conductivity in SCI mice. (A) Color-coded stick figures of joint activity during mice locomotion. (B) Analysis of knee and ankle joint activity in each group. (C) Representative electrophysiological images at different stimulation sites. (D) Quantitative evaluation of motor evoked potential (MEP) amplitudes (n = 3). (E) Quantitative evaluation of potential amplitudes at 0.5 mm rostral to the injury site (n = 3). (F) Quantitative evaluation of potential amplitudes at 2 mm caudal to the injury site (n = 3). (G) Quantitative evaluation of potential amplitudes at 5 mm caudal to the injury site (n = 3). All data are presented as the mean ± SEM (ns, not statistically significant; ***, P < 0.001 vs. Injury)

The impact of HA-CurNPs on the electrical conductivity of injured nerves

The disruption of spinal cord neural pathways is a major cause of impaired motor function following SCI. After SCI, the amplitude of motor evoked potentials (MEPs) significantly reduces and may completely vanish in severe instances [64]. Therefore, monitoring changes in neural electrical conductivity is critical and valuable for SCI treatment evaluation. This study assessed MEPs and spinal cord neural electrical conductivity (Fig. 5C). The motor cortex on the left side of the brain was stimulated, and electrical signals were recorded in the right gastrocnemius muscle. Results showed that after HA-CurNPs treatment, the amplitude of MEPs was significantly higher than in the injury group, while the amplitudes in the Cur and CurNPs groups did not differ significantly from the injury group (Fig. 5D). This indicates that HA-CurNPs treatment aids in the recovery of MEP amplitude, thereby promoting neuromuscular function recovery. Additionally, spinal cord neural electrical conductivity was evaluated. The spinal cord was stimulated 1 mm rostral to the injury site, and responses were recorded at 0.5 mm rostral, 2 mm caudal, and 5 mm caudal to the injury site. Results showed no significant differences in potential amplitude among the groups at 0.5 mm rostral, indicating that neural impulses were unaffected when not passing through the injury site (Fig. 5E). However, at 2 mm caudal to the injury site, the injury group’s potential amplitude significantly decreased, while HA-CurNPs treatment significantly improved the amplitude. The Cur and CurNPs groups showed no improvement compared to the injury group (Fig. 5F). A similar trend was observed at 5 mm caudal to the injury site (Fig. 5G). These findings suggest that HA-CurNPs help restore spinal cord electrical conductivity following SCI, thereby promoting neural conduction capacity recovery in mice.

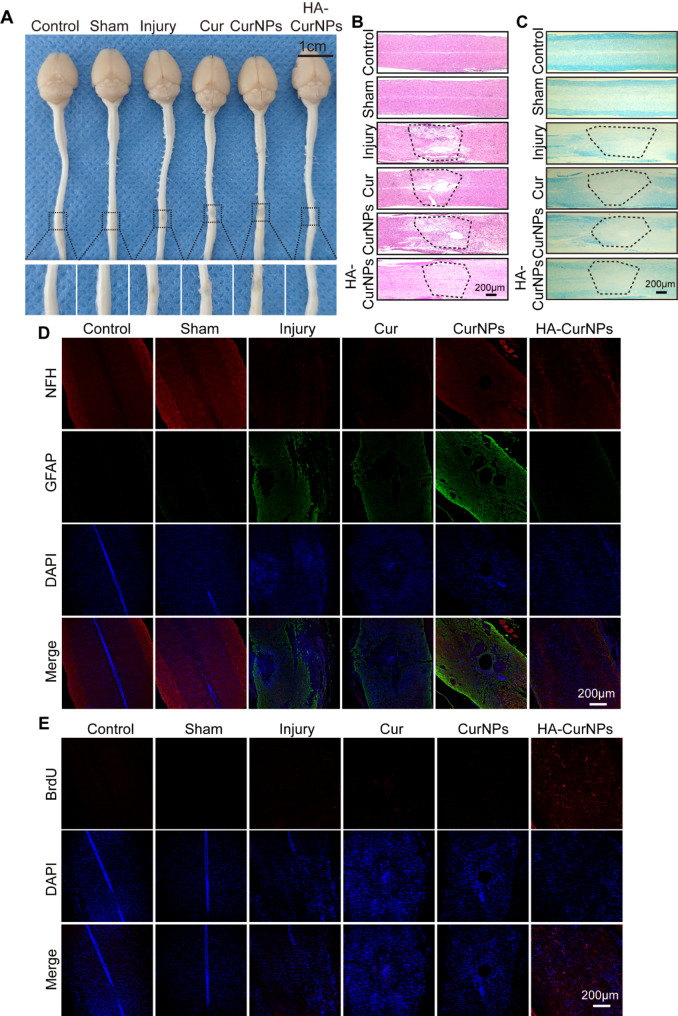

Evaluation of HA-CurNPs on spinal cord tissue repair

To assess whether HA-CurNPs can promote tissue repair following SCI, spinal cord tissue samples were first isolated from mice two months after SCI induction to observe their gross morphology. As shown in Fig. 6A, after HA-CurNPs treatment, the cavities at the injury site were significantly reduced, and the continuity of the spinal cord was markedly improved. In contrast, treatments with Cur and CurNPs did not show significant changes compared to the injury group, with the spinal cord continuity remaining disrupted. Following HE staining, it was further observed that the spinal cords in the injury group exhibited high levels of discontinuity and incompleteness. Post-treatment, the integrity and continuity of the spinal cord improved to varying degrees, but the Cur and CurNPs groups still displayed visible cavities. In the HA-CurNPs group, spinal cord integrity and continuity were significantly enhanced, although not to the levels seen in the control and sham groups (Fig. 6B). SCI often leads to myelin damage, resulting in severe functional impairment, given that intact myelin is essential for nerve impulse conduction [65]. Therefore, LFB staining was conducted on the spinal cord tissues. Results showed that the HA-CurNPs group exhibited significantly better myelin preservation, with increased staining indicating myelin repair, compared to the injury group. The Cur and CurNPs treatments offered minimal myelin protection (Fig. 6C). These findings suggest that HA-CurNPs protect nerve fibers by preserving myelin. To investigate the effect of HA-CurNPs on nerve fibers and glial scar formation, anti-NFH and anti-GFAP were used to label nerve fibers and glial scars, respectively. Results showed decreased NFH expression in the injury group, which increased to varying extents following treatment. Notably, HA-CurNPs treatment significantly increased NFH expression, spanning the injury site, indicating substantial promotion of nerve fiber preservation and regeneration. In the injury, Cur, and CurNPs groups, GFAP expression was significantly elevated, while in the HA-CurNPs group, GFAP expression was markedly reduced, indicating effective inhibition of glial scar formation by HA-CurNPs (Fig. 6D). To determine whether HA-CurNPs treatment induced cell proliferation at the injury site, anti-BrdU was used to label proliferating cells. Results showed that, although cell proliferation occurred to varying degrees following spinal cord injury, the injury, Cur, and CurNPs groups had significantly fewer proliferating cells. HA-CurNPs treatment significantly increased cell proliferation at the injury site (Fig. 6E). Additionally, to assess the biosafety of Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs, HE staining was performed on the heart, liver, spleen, lungs, kidneys, and brain of the mice. Results showed no significant tissue abnormalities in these organs (Fig. S10). These findings indicate that HA-CurNPs not only promote spinal cord tissue repair but also ensure biosafety.

Fig. 6.

The impact of HA-CurNPs on spinal cord tissue repair. (A) Gross morphology of spinal cord tissue (scale bar = 1 cm). (B) HE staining of spinal cord tissue, with the dashed lines indicate the site of spinal cord injury. (C) LFB staining of spinal cord tissue, with the dashed lines indicate the site of spinal cord injury. (D) Immunohistochemical staining of spinal cord tissue with anti-NFH (red) and anti-GFAP (green) (scale bar = 200 μm). (E) Immunohistochemical staining of spinal cord tissue with anti-BrdU (red) (scale bar = 200 μm)

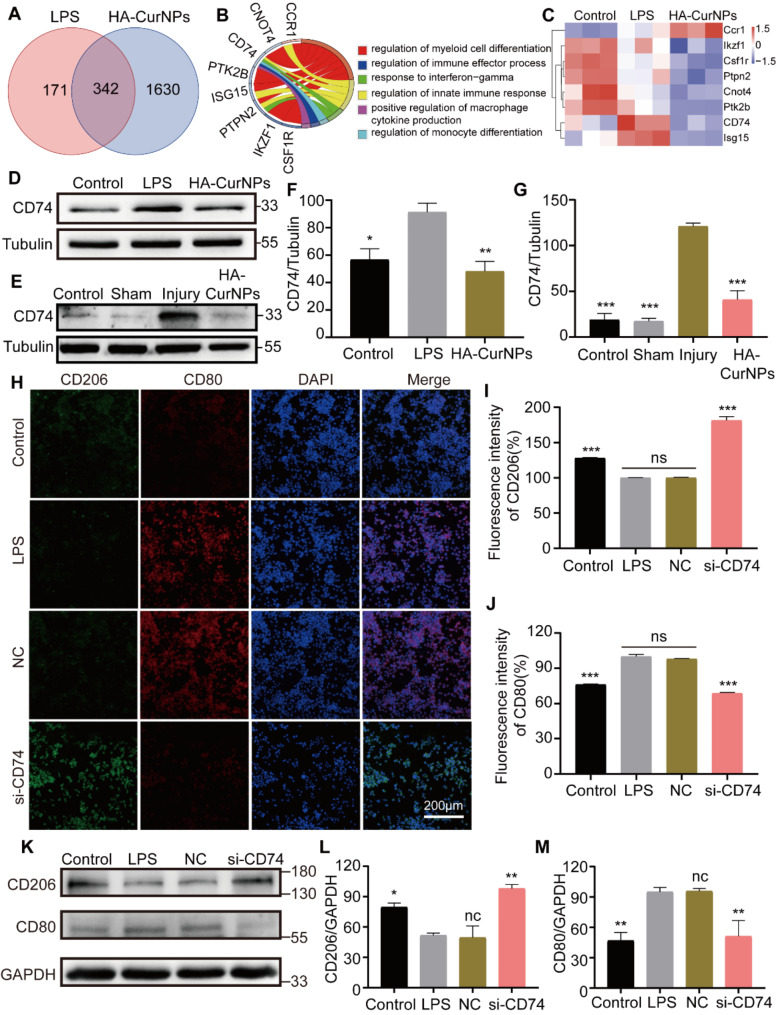

Mechanism of HA-CurNPs in promoting M2 polarization of microglia

Previous studies have demonstrated that HA-CurNPs scavenged various extracellular free radicals, eliminate intracellular ROS, and promote M2 polarization of microglia, thereby exerting anti-inflammatory effects and facilitating neuronal injury repair. In vivo, HA-CurNPs have been shown to improve improvement in motor function and spinal cord tissue repair in SCI mice. To further investigate the mechanisms of HA-CurNPs, a proteomics analysis was conducted following LPS (100 ng/mL) treatment of BV2 cells for 24 h, followed by co-culture with HA-CurNPs for another 24 h, and then cell proteins were collected for analysis. As shown in Fig. 7A, there were 513 differentially expressed proteins between the control and LPS groups, and 1972 differentially expressed proteins between the LPS and HA-CurNPs groups. Among these, 342 were common differentially expressed proteins. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed on these 342 proteins, and proteins associated with microglial polarization were identified and represented using a chord diagram. It was found that CD74 is involved in pathways such as myeloid cell differentiation regulation, positive regulation of macrophage cytokine production, and monocyte differentiation regulation (Fig. 7B). Microglia serve as the resident macrophages or myeloid cells within the central nervous system (CNS) [66, 67], and are also a type of monocyte [68], Thus, the pathways of myeloid cell differentiation, macrophage cytokine production, and monocyte differentiation are closely related to microglia polarization. The heatmap of enrichment analysis showed that CD74 expression increased after LPS stimulation, consistent with previous findings [69], and decreased after HA-CurNPs treatment (Fig. 7C). Previous studies have shown that inhibiting the exression of CD74 in adipose tissue suppresses macrophage M1 polarization while enhancing M2 polarization [13, 70]. Although the role of CD74 in microglia polarization and spinal cord injury repair is less reported, our study suggests that HA-CurNPs likely promote M2 polarization of microglia by inhibiting the expression of CD74, ultimately facilitating spinal cord injury repair.

Fig. 7.

Mechanism of HA-CurNPs in promoting M2 polarization of microglia. (A) The number of differentially expressed proteins between groups. (B) Circos plot showing enriched pathways and proteins. (C) Heatmap of protein expression identified by enrichment analysis. (D) Western blot analysis of CD74 expression in different groups after LPS and HA-CurNPs treatment. (E) Western blot analysis of CD74 expression in spinal cord protein from different groups of mice after spinal cord injury and HA-CurNPs treatment. (F) Quantitative evaluation of CD74 relative gray value in Fig. D (n = 3). (G) Quantitative evaluation of CD74 relative gray value in Fig. E (n = 3). (H) Immunocytochemical detection of CD80 (red) and CD206 (green) expression in BV2 cells after LPS treatment and transfection with si-NC and si-CD74. (I) Quantitative evaluation of CD206 fluorescence intensity in Fig. H (n = 3). (J) Quantitative evaluation of CD80 fluorescence intensity in Fig. H (n = 3). (K) Western blot analysis of CD80 and CD206 expression in different groups of BV2 cells after LPS treatment and transfection with si-NC and si-CD74. (L) Quantitative evaluation of CD206 relative gray value in Fig. K (n = 3). (M) Quantitative evaluation of CD80 relative gray value in Fig. K (n = 3). All data are presented as the mean ± SEM (ns, not statistically significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 vs. LPS/Injury)

To further validate the proteomics results, BV2 cells were stimulated with LPS, then co-cultured with HA-CurNPs, and cell proteins were collected for western blot analysis. Results showed that CD74 expression significantly increased after LPS stimulation but significantly decreased after HA-CurNPs treatment (Fig. 7D, F), further confirming the proteomics findings. On the third day post-spinal cord injury, spinal cord tissues were lysed and proteins collected for western blot analysis, showing that CD74 expression significantly increased in the injury group, but HA-CurNPs treatment markedly reduced this increase (Fig. 7E, G). Similar results were obtained from immunofluorescence staining of spinal cord sections collected on the third day post-injury (Fig. S11). CD74 small interfering RNA (si-CD74) was then constructed and its interference efficiency verified (Fig. S12). After LPS stimulation, cells transfected with si-CD74 underwent immunocytochemistry, showing that CD80 expression increased while CD206 expression decreased in the LPS and si-NC groups. In contrast, in the si-CD74 group, CD80 expression decreased while CD206 expression increased, indicating that inhibiting CD74 expression promoted microglia M2 polarization and suppressed M1 polarization (Fig. 7H-J). Western blot analysis yielded similar results (Fig. 7K-M). Overall, these findings indicate that HA-CurNPs promote microglia M2 polarization and inhibit M1 polarization by suppressing CD74 expression.

Conclusion

Effective treatment of SCI requires drugs with strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. In this study, we designed and synthesized curcumin nanoparticles (HA-CurNPs) with excellent biocompatibility. HA-CurNPs exhibit better antioxidant performance compared to both Cur and CurNPs. HA-CurNPs not only effectively scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) both inside and outside cells, but also eliminate ROS within the animal body, and further reduce cellular apoptosis. Additionally, HA-CurNPs promote M2 polarization of microglia and inhibit M1 polarization by suppressing the expression of CD74, thereby alleviating the inflammatory response and promoting the repair of injured neurons, ultimately facilitating the recovery of motor function in SCI mice. Furthermore, HA-CurNPs enhance the recovery of neural electrical conductivity, promote the preservation and regeneration of neurofilaments, inhibit the formation of glial scars, and protect the structure of myelin sheaths post-SCI. In summary, HA-CurNPs present a promising therapeutic approach for the treatment of SCI.

Experimental section

Materials

Curcumin (HY-N0005) was sourced from MedChemExpress (Shanghai, China). EGCG was obtained from Aladdin (Shanghai, China). Hyaluronic acid (HA, 10 kDa) and the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, MA0218) were procured from Meilunbio (China). Tribromoethanol (T48402), Glutamic acid (49621) and Lipopolysaccharide (LPS, L2880) were purchased from Sigma (USA). The L-012 chemiluminescent probe (120–04891) was purchased from FUJIFILM Wako (Japan). All chemicals employed in this research were of analytical grade and did not require additional purification. ABTS (HY-15902) and DPPH (HY-112053) were obtained from MCE (Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA). 2’,7’-dihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, S0033S) and dihydroethidium (DHE, S0063) were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology (Jiangsu, China). Anti-CD80 (14292-1-AP) and anti-CD206 (60143-1-Ig) were obtained from Proteintech (Wuhan, China). Anti-CD74 (ab289885), anti-IL-6 (ab290735), anti-iNOS (ab178945), anti-NFH (ab315203), anti-GFAP (ab7260), anti-BrdU (ab8955), anti-beta-III tubulin (ab18207), anti-tubulin (ab6160), and anti-GAPDH (ab8245) were sourced from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from ABclonal Technology, and fluorescent secondary antibodies were obtained from Abcam. Unless noted differently, all cell culture reagents were obtained from Gibco Technologies.

Synthesis of HA-CurNPs

In brief, EGCG (1 g) was dissolved in a mixture of deionized water and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 9:1, v/v). The polymerization reaction was initiated by adding acetaldehyde (7.2 mL) and maintained at 30 °C under nitrogen for 24 h. The resulting solution was dialyzed and freeze-dried to obtain pEGCG. CurNPs were prepared using a nanoprecipitation method. 3 mg of pEGCG was mixed with 25 µL of curcumin solution (20 mg/mL) under light-shielded conditions for 10 min. Water was slowly added to the pEGCG and curcumin mixture to induce nanoparticle formation. During this process, self-assembly occurred, with pEGCG and curcumin repolymerizing through intermolecular hydrogen bonding or hydrophobic interactions, forming a stable nanostructure. The resulting particles were collected by centrifugation (12000 rpm, 20 min), redissolved in water, and termed CurNPs. Preparation of HA-CurNPs involved dispersing 3 mg of CurNPs in 1 mL of 1% HA-PBA aqueous solution, followed by 10 min of sonication and centrifugation (12000 rpm, 20 min) to collect the particles, which were then redissolved in water to obtain HA-CurNPs.

Characterization

The structural properties and morphology of HA-CurNPs were characterized using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The average size of the HA-CurNPs was measured using a Litesizer 500 analyzer. The absorbance of HA-CurNPs was recorded using a UV-Visible spectrophotometer (Lambda 365). The infrared spectrum of HA-CurNPs was measured using a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (INVENIO R). Additionally, the zeta potential of HA-CurNPs was determined using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano analyzer.

ABTS and DPPH scavenging assay

To assess the antioxidant capabilities of Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs, the ABTS•+ was produced from an ABTS stock solution (5 mM in PBS) through the use of manganese dioxide, following a protocol outlined in our earlier research [1]. Various concentrations of Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs were introduced into the ABTS•+ solution, and the absorbance at 734 nm was quantified using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Microplate Reader 550). Similarly, the DPPH radical scavenging ability of Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs were evaluated using a DPPH solution (1 mM in ethanol). Various concentrations of Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs were introduced into the DPPH solution, and the absorbance at 517 nm was quantified using a microplate reader.

Cell viability assay

To assess cell viability, a CCK-8 assay was conducted. Initially, HT22 cells and hippocampal neurons were cultured in 96-well plates for 24 h. The cells were then treated with varying concentrations of Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs for 24 h. Following this incubation, the cells were exposed to CCK-8 solution for 1 h, and the absorbance at 450 nm was subsequently quantified using a microplate reader.

Detection of intracellular ROS levels

This study evaluated the ability of HA-CurNPs to scavenge intracellular ROS using flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy. Briefly, HT22 cells were cultured and seeded into 6-well plates, and after 24 h, glutamate (120 mM) was added to induce oxidative stress. After 12 h, the medium was replaced with media containing Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs, and the cells were cultured for an additional 24 h. Cells were subsequently collected and incubated with DCFH-DA for 30 min in darkness at room temperature, before being analyzed by flow cytometry (BD, Canto) to measure DCF fluorescence intensity. Similarly, HT22 cells were seeded in 24-well plates. After induction with glutamate, the cells were treated with Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs for 24 h. Post-treatment, they were incubated with DCFH-DA or DHE for 30 min in darkness at room temperature, and fluorescence changes were observed under a confocal fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems, USA). DCFH-DA was employed to assess total ROS levels within the cells, while DHE was used to evaluate the levels of superoxide anion radicals.

si-RNA transfection

For siRNA transfection, the Lipo8000 transfection reagent (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was utilized. Prior to transfection, BV2 cells were seeded in culture dishes and after the cells adhered, they were treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 24 h. Following this, the transfection was carried out according to the Lipo8000 reagent protocol. Specifically, 5 µL of si-CD74 (20 µM) and 5 µL of si-NC (20 µM) were each mixed with 5 µL of Lipo8000 transfection reagent in 125 µL of DMEM. After incubating the transfection mixture at room temperature for 20 min, it was added dropwise to the cell culture plate and co-incubated with cell for 24 h. Subsequent to the transfection, the cells were subjected to immunocytochemical staining or Western blot analysis to assess the outcomes. siRNA (si-CD74) fragments (sense:5ʼ-ACUAAUGGGUCAGAAAUGGGG-3ʼ; antisense: 5ʼ-CCAUUUCUGACCCAUUAGUAG-3ʼ) was synthesized by Guangzhou IGE Co., Ltd.

Culturing primary neurons and immunofluorescence staining of cells

The culturing of primary neurons was conducted as previously described [71]. Briefly, hippocampal tissue from one-day-old Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats was treated with papain (10 mM) at 37 °C for 25 min. The cells were then seeded onto slides pre-coated with poly-D-lysine (PDL) and cultured in Neurobasal medium supplemented with 10% B27 for 48 h. Following oxidative stress induction with glutamate, the cells were co-incubated with Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs for 24 h. Cells were subsequently fixed, permeabilized, and blocked with 3% BSA for one hour before overnight incubation with anti-beta-III tubulin. This was followed by a one-hour incubation with secondary antibodies and stained the cell nuclei with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Finally, neuronal morphology was analyzed using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Leica, Germany).

Establishment of SCI mouse model

Initially, the mice were anesthetized with a 3% solution of tribromoethanol (Sigma) via intraperitoneal injection [7]. After depilating the dorsal area, a 2 cm longitudinal incision was made on the back, muscles were gently separated, and the T8-T10 vertebrae were revealed. A SCI model was created by delivering an impact to the T8-T10 spinal cord using the louisville injury system apparatus (LISA, Louisville, KY, USA). The muscle and skin layers were subsequently sutured with 4 − 0 silk thread. Postoperatively, all mice received subcutaneous injections of gentamicin (8 mg/kg) for three consecutive days to prevent infection. In the treatment group, drugs were administered via tail vein injection for seven consecutive days post-surgery, while the control group received saline injections for the same duration. Postoperative care included massaging the bladders of the mice every 12 h to assist in urination until reflexive bladder control was restored. Unless otherwise specified, drug treatment in the mouse SCI model was administered via tail vein injection once daily for 7 consecutive days following the induction of the injury.

Measurement of ROS levels in mouse

The measurement of ROS in mice was primarily conducted using the L-012 chemiluminescent probe. This probe is highly sensitive and is particularly useful in studies of oxidative stress and inflammation, as it can effectively detect the generation of ROS [72]. As previously described [1], briefly, three days post-injury, mice were anesthetized, followed by an intraperitoneal injection of the L-012 chemiluminescent probe (50 mg/kg). Finally, the luminescent signals were captured and analyzed using an animal in vivo imaging system (AniView 600, BLT).

Western blotting

Briefly, after collecting cell or spinal cord proteins using lysis buffer, the proteins were loaded into gel wells for electrophoresis. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane by electroblotting. Subsequently, the membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat milk at room temperature for 1 h, followed by incubation with primary antibody at 4 °C for 12 h, then the membrane was incubated with secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. Finally, the protein bands were exposed and data were collected using an imaging system (Azure Biosystems, USA).

Assessment of motor function in mice

Mice were divided into six groups: control, sham, injury, Cur, CurNPs, and HA-CurNPs, with five mice per group. Following successful SCI modeling, the basso mouse scale (BMS) scoring system was used to assess mice until the scores stabilized [73].

After two months, when the scores stabilized, an inclined plane test was conducted to assess the balance capabilities of the mice. An adjustable inclined plane with a rubber-matted surface was used to increase traction. Mice were placed in the middle of the inclined plane, perpendicular to the direction of inclination. The angle was gradually increased from a horizontal position, and the maximum angle at which each mouse could remain on the inclined plane without sliding was recorded. Each mouse underwent multiple tests (typically 3 to 5 times) to ensure data consistency and reliability, and the results were compiled for each group.

Additionally, footprint analysis was used to assess and record the coordination and gait of the mice. A long corridor with walls on both sides was prepared to ensure straight movement, and a clean sheet of paper was laid at the bottom. The hind paws of the mice were dipped in blue non-toxic paint, and as the mice walked from one end of the corridor to the other, they left colored footprints on the paper. The footprints were analyzed for gait continuity and symmetry, as well as the stride length and width of the forelimbs and hindlimbs. Changes and recovery in motor function were assessed by comparing pre- and post-injury footprints.

Furthermore, the CatWalk system was used to perform a detailed and precise gait analysis to evaluate the recovery of motor function in the mice. The CatWalk system consists of a long walkway equipped with a high-resolution camera underneath to capture the fluorescent footprints made by the mice as they walked on a transparent surface. The CatWalk system automatically recorded various parameters of each step taken by the mice, including footprint contact area, stance intensity, and movement regularity. These parameters were analyzed to assess the recovery of motor capabilities and gait.

Lastly, high-speed video cameras were used to capture side-view videos of the mice walking. Small markers were placed on major joints such as the hips, knees, and ankles before video analysis to aid in more accurately tracking joint movement. The phase, coordination, and other dynamic characteristics of the gait were analyzed by calculating changes in the position and angles of each joint during walking.

Measurement of neural electrical conduction function

To assess the recovery of neural impulse conduction following SCI, neural electrical conduction function was measured two months post-SCI modeling. In brief, the fur was removed from the head and right gastrocnemius muscle areas after anesthetizing the mice. A small incision was made along the midline of the skull to reveal the cranial bone, and a stimulating electrode was implanted in the left motor area. A receiving electrode was then implanted in the right gastrocnemius muscle. Motor evoked potentials were recorded using the biosignal acquisition and analysis system (BL-420 N, Chengdu Taimeng Software Co., Ltd., China), focusing on the amplitude of the evoked potentials.

Additionally, an incision was made along the surgical scar on the mouse’s back, and a 1 cm section of the vertebra above and below the SCI site was removed to expose the spinal cord. The stimulating electrode was implanted 1 mm cranial to the SCI site, and recording electrodes were placed at 0.5 mm cranial, 2 mm caudal, and 5 mm caudal to the injury site to capture the electrical potentials.

The histopathological staining of the spinal cord

In brief, tissue samples were taken from 0.5 mm above and below the spinal cord injury site in mice. Following fixation in formaldehyde, the tissues underwent dehydration, clearing, paraffin embedding, sectioning, deparaffinization, and staining. Both HE and LFB staining were performed. Additionally, immunohistochemical staining was conducted using primary antibodies against CD74, CD206/CD80, GFAP/NFH, and BrdU. Corresponding secondary antibodies were then applied, followed by nuclear staining with DAPI. The prepared slides were examined under a confocal fluorescence microscope to capture images.

Liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry for proteomics

BV2 cells were seeded in six-well plates and assigned to three groups: control, LPS, and HA-CurNPs, with each group having three replicates. All groups except the control were treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 24 h. Subsequently, the medium was replaced with fresh complete culture medium across all groups. The treatment group received an additional incubation with HA-CurNPs for 24 h. Following this, cellular proteins were harvested using previously established methods. Briefly, proteins were digested into peptides using trypsin, and these peptides were then loaded onto a liquid chromatography column for separation. The peptides were identified via mass spectrometry, which inferred the source proteins. The data obtained were analyzed using bioinformatics tools to elucidate the protein profiles.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software (version 23.0). The Shapiro-Wilk test was utilized to assess the normality of continuous variables. Group differences were evaluated with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Data are displayed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). All experiments were conducted in triplicate unless otherwise specified, and statistical significance is indicated as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 vs. LPS/Injury.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Nos. 82102314 (to ZSJ), and 32170977 (to HSL) and Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, Nos. 2022A1515010438 (to ZSJ) and 2022A1515012306 (to HSL). This study was supported by the Clinical Frontier Technology Program of the First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University, China, Nos. JNU1AF-CFTP- 2022- a01206 (to HSL); This study was supported by Guangzhou Science and TechnologyPlan Project, 2023A04J1284 (to ZSJ), 2023A03J1024 (to HSL) and 202201020018 (to HSL); This study was supported by Young Talent Support Project of Guangzhou Association for Science and Technology, QT2024-39 (to ZSJ). This study was supported by The Open Fund of Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Laboratory of Spine and Spinal Cord Reconstruction, 2023B121203001 (to Guodong Sun).

Author contributions

ZSJ, HSL and XJ designed the project and experiments. TJC, LW and YCX performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. KW, PW, CL, XGL and CQH involved in the data analysis. HSL, XJ, and ZSJ provided the funds of research. WX, and GDS participated in the supervision of this research. And HSL, XJ and ZSJ revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were approved and performed following the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee of Jinan University and also in accordance with the policy of the National Institute of Health (China).

Consent for publication

All authors agree for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Authors’ information

1 Department of Orthopedics, The First Afffliated Hospital, Jinan University, Guangzhou, Guangdong, 510632, China.

2 Key Laboratory of Biomaterials of Guangdong Higher Education Institutes, Engineering Technology Research Center of Drug Carrier of Guangdong, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Jinan University, Guangzhou, 510632, China.

3 The First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University, Guangzhou 510630, China; Guandgong Provincial Key Laboratory of Spine and Spinal Cord Reconstruction, The Fifth Affiliated Hospital (Heyuan Shenhe People’s Hospital), Jinan University Heyuan 517000, China.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Tianjun Chen, Li Wan and Yongchun Xiao contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Xin Ji, Email: jixin@jnu.edu.cn.

Hongsheng Lin, Email: tlinhsh@jnu.edu.cn.

Zhisheng Ji, Email: tzhishengji@jnu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Zheng J, Chen T, Wang K, Peng C, Zhao M, Xie Q, Li B, Lin H, Zhao Z, Ji Z, Tang BZ, Liao Y. Engineered Multifunctional Zinc-Organic Framework-Based Aggregation-Induced Emission Nanozyme for accelerating spinal cord Injury Recovery. ACS Nano. 2024;18:2355–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen L, Wang W, Lin Z, Lu Y, Chen H, Li B, Li Z, Xia H, Li L, Zhang T. Conducting molybdenum sulfide/graphene oxide/polyvinyl alcohol nanocomposite hydrogel for repairing spinal cord injury. J Nanobiotechnol. 2022;20:210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishida N, Sakuramoto I, Fujii Y, Hutama RY, Jiang F, Ohgi J, Imajo Y, Suzuki H, Funaba M, Chen X, Sakai T. Tensile mechanical analysis of anisotropy and velocity dependence of the spinal cord white matter: a biomechanical study. Neural Regen Res. 2021;16:2557–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang J, Chen J, Jin H, Lin D, Chen Y, Chen X, Wang B, Hu S, Wu Y, Wu Y, Zhou Y, Tian N, Gao W, Wang X, Zhang X. BRD4 inhibition attenuates inflammatory response in microglia and facilitates recovery after spinal cord injury in rats. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23:3214–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo WL, Qi ZP, Yu L, Sun TW, Qu WR, Liu QQ, Zhu Z, Li R. Melatonin combined with chondroitin sulfate ABC promotes nerve regeneration after root-avulsion brachial plexus injury. Neural Regen Res. 2019;14:328–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiao S, Wang C, Yang Q, Xu H, Lu J, Xu K. Rea regulates microglial polarization and attenuates neuronal apoptosis via inhibition of the NF-κB and MAPK signalings for spinal cord injury repair. J Cell Mol Med. 2021;25:1371–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng C, Luo J, Wang K, Li J, Ma Y, Li J, Yang H, Chen T, Zhang G, Ji X, Liao Y, Lin H, Ji Z. Iridium metal complex targeting oxidation resistance 1 protein attenuates spinal cord injury by inhibiting oxidative stress-associated reactive oxygen species. Redox Biol. 2023;67:102913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu C, Hu F, Jiao G, Guo Y, Zhou P, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Yi J, You Y, Li Z, Wang H, Zhang X. Dental pulp stem cell-derived exosomes suppress M1 macrophage polarization through the ROS-MAPK-NFκB P65 signaling pathway after spinal cord injury. J Nanobiotechnol. 2022;20:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin Z, Song J, Lin A, Yang W, Zhang W, Zhong F, Huang L, Lü Y, Yu W. GPR120 modulates epileptic seizure and neuroinflammation mediated by NLRP3 inflammasome. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lang GP, Li C, Han YY. Rutin pretreatment promotes microglial M1 to M2 phenotype polarization. Neural Regen Res. 2021;16:2499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobashi S, Terashima T, Katagi M, Nakae Y, Okano J, Suzuki Y, Urushitani M, Kojima H. Transplantation of M2-Deviated Microglia promotes recovery of motor function after spinal cord Injury in mice. Mol Ther. 2020;28:254–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukuda Y, Bustos MA, Cho SN, Roszik J, Ryu S, Lopez VM, Burks JK, Lee JE, Grimm EA, Hoon DSB, Ekmekcioglu S. Interplay between soluble CD74 and macrophage-migration inhibitory factor drives tumor growth and influences patient survival in melanoma. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guan D, Li Y, Cui Y, Zhao H, Dong N, Wang K, Ren D, Song T, Wang X, Jin S, Gao Y, Wang M. 5-HMF attenuates inflammation and demyelination in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice by inhibiting the MIF-CD74 interaction. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2023;55:1222–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu J, Zhao J, Chen H, Tan X, Zhang W, Xia Z, Yao D, Lei Y, Xu B, Wei Z, Hu J. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes protect against abdominal aortic aneurysm formation through CD74 modulation of macrophage polarization in mice. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2024;15:242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CH, Chen NF, Feng CW, Cheng SY, Hung HC, Tsui KH, Hsu CH, Sung PJ, Chen WF, Wen ZH. A coral-derived compound improves functional recovery after Spinal Cord Injury through its antiapoptotic and anti-inflammatory effects. Mar Drugs 2016; 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Liu Q, Zhou S, Wang X, Gu C, Guo Q, Li X, Zhang C, Zhang N, Zhang L, Huang F. Apelin alleviated neuroinflammation and promoted endogenous neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation after spinal cord injury in rats. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19:160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jo MJ, Kumar H, Joshi HP, Choi H, Ko WK, Kim JM, Hwang SSS, Park SY, Sohn S, Bello AB, Kim KT, Lee SH, Zeng X, Han I. Oral administration of α-Asarone promotes functional recovery in rats with spinal cord Injury. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polderman JA, Farhang-Razi V, Van Dieren S, Kranke P, DeVries JH, Hollmann MW, Preckel B, Hermanides J. Adverse side effects of dexamethasone in surgical patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;8:Cd011940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowers CA, Kundu B, Hawryluk GW. Methylprednisolone for acute spinal cord injury: an increasingly philosophical debate. Neural Regen Res. 2016;11:882–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma Q, Cai S, Jia Y, Sun X, Yi J, Du J. Effects of Hot-Water Extract from Vine Tea (Ampelopsis grossedentata) on acrylamide formation, Quality and Consumer Acceptability of Bread. Foods. 2020; 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Piwowarczyk L, Kucinska M, Tomczak S, Mlynarczyk DT, Piskorz J, Goslinski T, Murias M, Jelinska A. Liposomal Nanoformulation as a carrier for Curcumin and pEGCG-Study on Stability and Anticancer potential. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2022; 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Wang H, Du Z, Zhang C, Tang Z, He Y, Zhang Q, Zhao J, Zheng X. Biological evaluation and 3D-QSAR studies of curcumin analogues as aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:8795–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Binion DG, Otterson MF, Rafiee P. Curcumin inhibits VEGF-mediated angiogenesis in human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells through COX-2 and MAPK inhibition. Gut. 2008;57:1509–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiang D, Li Y, Cao Y, Huang Y, Zhou L, Lin X, Qiao Y, Li X, Liao D. Different effects of endothelial extracellular vesicles and LPS-Induced endothelial extracellular vesicles on vascular smooth muscle cells: role of Curcumin and its derivatives. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:649352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kundu M, Sadhukhan P, Ghosh N, Chatterjee S, Manna P, Das J, Sil PC. pH-responsive and targeted delivery of curcumin via phenylboronic acid-functionalized ZnO nanoparticles for breast cancer therapy. J Adv Res. 2019;18:161–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruzicka J, Urdzikova LM, Svobodova B, Amin AG, Karova K, Dubisova J, Zaviskova K, Kubinova S, Schmidt M, Jhanwar-Uniyal M, Jendelova P. Does combined therapy of curcumin and epigallocatechin gallate have a synergistic neuroprotective effect against spinal cord injury? Neural Regen Res. 2018;13:119–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.I EL-D, Manai M, Neili NE, Marzouki S, Sahraoui G, Ben Achour W, Zouaghi S, BenAhmed M, Doghri R, Srairi-Abid N. Dual Mechanism of Action of Curcumin in Experimental models of multiple sclerosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Dei Cas M, Ghidoni R. Dietary Curcumin: Correlation between Bioavailability and Health Potential. Nutrients. 2019; 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Zhang T, Chen Y, Ge Y, Hu Y, Li M, Jin Y. Inhalation treatment of primary lung cancer using liposomal curcumin dry powder inhalers. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2018;8:440–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dhule SS, Penfornis P, He J, Harris MR, Terry T, John V, Pochampally R. The combined effect of encapsulating curcumin and C6 ceramide in liposomal nanoparticles against osteosarcoma. Mol Pharm. 2014;11:417–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans AC, Martin KA, Saxena M, Bicher S, Wheeler E, Cordova EJ, Porada CD, Almeida-Porada G, Kato TA, Wilson PF, Coleman MA. Curcumin Nanodiscs improve solubility and serve as Radiological protectants against Ionizing Radiation exposures in a cell-cycle Dependent Manner. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2022; 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Montalbán MG, Coburn JM, Lozano-Pérez AA, Cenis JL, Víllora G, Kaplan DL. Production of Curcumin-Loaded Silk Fibroin nanoparticles for Cancer Therapy. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2018; 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Sharma M, Inbaraj BS, Dikkala PK, Sridhar K, Mude AN, Narsaiah K. Preparation of Curcumin Hydrogel Beads for the Development of Functional Kulfi: A Tailoring Delivery System. Foods. 2022; 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Zhang X, He J, Qiao L, Wang Z, Zheng Q, Xiong C, Yang H, Li K, Lu C, Li S, Chen H, Hu X. 3D printed PCLA scaffold with nano-hydroxyapatite coating doped green tea EGCG promotes bone growth and inhibits multidrug-resistant bacteria colonization. Cell Prolif. 2022;55:e13289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajabi S, Maresca M, Yumashev AV, Choopani R, Hajimehdipoor H. The Most Competent Plant-Derived Natural Products for Targeting Apoptosis in Cancer Therapy. Biomolecules. 2021; 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Jin J, Liu C, Tong H, Sun Y, Huang M, Ren G, Xie H. Encapsulation of EGCG by Zein-Gum Arabic Complex Nanoparticles and In Vitro Simulated Digestion of Complex Nanoparticles. Foods. 2022; 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Cañibano-Hernández A, Del Saenz L, Espona-Noguera A, Orive G, Hernández RM, Ciriza J, Pedraz JL. Hyaluronic acid enhances cell survival of encapsulated insulin-producing cells in alginate-based microcapsules. Int J Pharm. 2019;557:192–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang R, Jiang Y, Hao L, Yang Y, Gao Y, Zhang N, Zhang X, Song Y. CD44/Folate dual targeting receptor reductive response PLGA-Based micelles for Cancer Therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:829590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li W, Zhou C, Fu Y, Chen T, Liu X, Zhang Z, Gong T. Targeted delivery of hyaluronic acid nanomicelles to hepatic stellate cells in hepatic fibrosis rats. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:693–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Puré E, Cuff CA. A crucial role for CD44 in inflammation. Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:213–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao Y, Zhang T, Duan S, Davies NM, Forrest ML. CD44-tropic polymeric nanocarrier for breast cancer targeted rapamycin chemotherapy. Nanomedicine. 2014;10:1221–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campo GM, Avenoso A, Campo S, D’Ascola A, Nastasi G, Calatroni A. Small hyaluronan oligosaccharides induce inflammation by engaging both toll-like-4 and CD44 receptors in human chondrocytes. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:480–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leiva-Vega J, Villalobos-Carvajal R, Ferrari G, Donsì F, Zúñiga RN, Shene C, Beldarraín-Iznaga T. Influence of interfacial structure on physical stability and antioxidant activity of curcumin multilayer emulsions. Food Bioprod Process. 2020;121:65–75. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu B, Kang Z, Yan W. Synthesis, stability, and antidiabetic activity evaluation of (–)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) palmitate derived from natural tea polyphenols. Molecules. 2021;26:393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marinho A, Nunes C, Reis S. Hyaluronic acid: a key ingredient in the therapy of inflammation. Biomolecules. 2021;11:1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mansoori B, Mohammadi A, Abedi-Gaballu F, Abbaspour S, Ghasabi M, Yekta R, Shirjang S, Dehghan G, Hamblin MR, Baradaran B. Hyaluronic acid-decorated liposomal nanoparticles for targeted delivery of 5-fluorouracil into HT-29 colorectal cancer cells. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235:6817–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu H, Kong L, Zhu X, Ran T, Ji X. pH-Responsive nanoparticles for delivery of Paclitaxel to the Injury Site for inhibiting vascular restenosis. Pharmaceutics. 2022; 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Zeng S, Liu S, Lan Y, Qiu T, Zhou M, Gao W, Huang W, Ge L, Zhang J. Combined photothermotherapy and chemotherapy of oral squamous cell Carcinoma guided by multifunctional nanomaterials enhanced Photoacoustic Tomography. Int J Nanomed. 2021;16:7373–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kittimongkolsuk P, Pattarachotanant N, Chuchawankul S, Wink M, Tencomnao T. Neuroprotective effects of extracts from Tiger milk mushroom Lignosus Rhinocerus against Glutamate-Induced toxicity in HT22 hippocampal neuronal cells and neurodegenerative diseases in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biology (Basel). 2021; 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Li Q, Qin M, Tan Q, Li T, Gu Z, Huang P, Ren L. MicroRNA-129-1-3p protects cardiomyocytes from pirarubicin-induced apoptosis by down-regulating the GRIN2D-mediated ca(2+) signalling pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:2260–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feng Y, Wu JJ, Sun ZL, Liu SY, Zou ML, Yuan ZD, Yu S, Lv GZ, Yuan FL. Targeted apoptosis of myofibroblasts by elesclomol inhibits hypertrophic scar formation. EBioMedicine. 2020;54:102715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huynh DTN, Jin Y, Myung CS, Heo KS. Ginsenoside Rh1 induces MCF-7 cell apoptosis and autophagic cell death through ROS-Mediated akt signaling. Cancers (Basel). 2021; 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Huang S, Zhou C, Zeng T, Li Y, Lai Y, Mo C, Chen Y, Huang S, Lv Z, Gao L. P-Hydroxyacetophenone ameliorates Alcohol-Induced steatosis and oxidative stress via the NF-κB Signaling Pathway in zebrafish and hepatocytes. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen TY, Tseng CL, Lin CA, Lin HY, Venkatesan P, Lai PS. Effects of Eye drops containing Hyaluronic Acid-Nimesulide conjugates in a Benzalkonium Chloride-Induced Experimental Dry Eye rabbit model. Pharmaceutics. 2021; 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Arioz BI, Tastan B, Tarakcioglu E, Tufekci KU, Olcum M, Ersoy N, Bagriyanik A, Genc K, Genc S. Melatonin attenuates LPS-Induced Acute Depressive-Like behaviors and Microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation through the SIRT1/Nrf2 pathway. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seitz M, Köster C, Dzietko M, Sabir H, Serdar M, Felderhoff-Müser U, Bendix I, Herz J. Hypothermia modulates myeloid cell polarization in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. J Neuroinflammation. 2021;18:266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou Q, Lin L, Li H, Wang H, Jiang S, Huang P, Lin Q, Chen X, Deng Y. Melatonin reduces Neuroinflammation and improves axonal hypomyelination by modulating M1/M2 Microglia polarization via JAK2-STAT3-Telomerase pathway in postnatal rats exposed to Lipopolysaccharide. Mol Neurobiol. 2021;58:6552–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang T, Li B, Wang Z, Yuan X, Chen C, Zhang Y, Xia Z, Wang X, Yu M, Tao W, Zhang L, Wang X, Zhang Z, Guo X, Ning G, Feng S, Chen X. Mir-155-5p promotes dorsal Root Ganglion Neuron Axonal Growth in an Inhibitory Microenvironment via the cAMP/PKA pathway. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:1557–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhu Q, Hong Y, Huang Y, Zhang Y, Xie C, Liang R, Li C, Zhang T, Wu H, Ye J, Zhang X, Zhang S, Zou X, Ouyang H. Polyglutamic Acid-Based Elastic and tough Adhesive Patch promotes tissue regeneration through in situ macrophage modulation. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2022;9:e2106115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zha Z, Chen Q, Xiao D, Pan C, Xu W, Shen L, Shen J, Chen W. Mussel-inspired Microgel Encapsulated NLRP3 inhibitor as a synergistic strategy against Dry Eye. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:913648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tang JJ, Huang LF, Deng JL, Wang YM, Guo C, Peng XN, Liu Z, Gao JM. Cognitive enhancement and neuroprotective effects of OABL, a sesquiterpene lactone in 5xFAD Alzheimer’s disease mice model. Redox Biol. 2022;50:102229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu J, Lu Y, Tang M, Shao F, Yang D, Chen S, Xu Z, Zhai L, Chen J, Li Q, Wu W, Chen H. Fucoxanthin Prevents Long-Term Administration l-DOPA-Induced neurotoxicity through the ERK/JNK-c-Jun System in 6-OHDA-Lesioned mice and PC12 cells. Mar Drugs. 2022; 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Eungpinichpong W, Sitthiracha P, GROUND REACTION FORCE OF. STEP MARCHING: A PILOT STUDY. GEOMATE J. 2020;19:104–9. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li Z, Zhao W, Liu W, Zhou Y, Jia J, Yang L. Transplantation of placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cell-induced neural stem cells to treat spinal cord injury. Neural Regen Res. 2014;9:2197–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Santos EN, Fields RD. Regulation of myelination by microglia. Sci Adv. 2021;7:eabk1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Villa A, Klein B, Janssen B, Pedragosa J, Pepe G, Zinnhardt B, Vugts DJ, Gelosa P, Sironi L, Beaino W, Damont A, Dollé F, Jego B, Winkeler A, Ory D, Solin O, Vercouillie J, Funke U, Laner-Plamberger S, Blomster LV, Christophersen P, Vegeto E, Aigner L, Jacobs A, Planas AM, Maggi A, Windhorst AD. Identification of new molecular targets for PET imaging of the microglial anti-inflammatory activation state. Theranostics. 2018;8:5400–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhan L, Fan L, Kodama L, Sohn PD, Wong MY, Mousa GA, Zhou Y, Li Y, Gan L. A MAC2-positive progenitor-like microglial population is resistant to CSF1R inhibition in adult mouse brain. Elife. 2020; 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]