Abstract

Photosystem II (PSII) represents the most vulnerable component of the photosynthetic machinery and its response in plants subjected to abiotic stress has been widely studied over many years. PSII is a thylakoid membrane-located multiprotein pigment complex that catalyses the light-induced electron transfer from water to plastoquinone with the concomitant production of oxygen. PSII is rich in intrinsic (PsbA and PsbD, namely D1 and D2, CP47 or PsbB and CP43 or PsbC) but also extrinsic proteins. The first ones are more largely conserved from cyanobacteria to higher plants while the extrinsic proteins are different among species. It has been found that extrinsic proteins involved in oxygen evolution change dramatically the PSII efficiency and PSII repair systems. However, little information is available on the effects of abiotic stress on their function and structure.

Keywords: abiotic stress, extrinsic protein, intrinsic protein, photosynthesis, photosystem II

Highlights

Intrinsic and extrinsic proteins of PSII help counteract light stress

Abiotic stressors strongly influence PSII proteins dynamics

Role of extrinsic proteins in PSII repairing cycle

Introduction

Photosynthesis is the process that converts sunlight into chemical energy utilized to synthesize organic compounds. It represents the most important process on the Earth carried out by higher plants, algae, and cyanobacteria. The process exploits solar radiation to induce a charge separation from chlorophyll (electron donor) to pheophytin (electron acceptor) which represents the key phenomenon of the whole process. This chemical event occurs in two complexes located inside the thylakoid membranes, photosystem II (PSII) and I (PSI). Briefly, a photosystem is a supramolecular protein that absorbs the sunlight through a light-harvesting complex (LHC), chlorophyll (Chl)–protein complex that absorbs light and funnels the energy to the reaction centre Chl a molecule(s), using Foster resonance energy transfer. The reaction centre is the place where light energy is collected and used to power photosynthetic redox reactions, leading to the synthesis of ATP and NADPH. In higher plants, two photosystems show some differences such as (Caffarri et al. 2014):

-

-

location in the thylakoid membranes: PSI is located in the non-appressed grana region and stroma lamellae while PSII is in the appressed grana region;

-

-

different reaction centre: PSI is an iron–sulphur type reaction centre (type I) while PSII has a quinone type reaction centre (type II or Q-type). In addition, the core complex of PSI is made up of about 15 protein subunits while that of PSII is a multi-subunit complex with about 25–30 subunits;

-

-

the peak in light absorption: PSI has maximum absorption close to 682 nm, while PSII at 677 nm. In addition, due to the higher LHC complement of PSI as compared to PSII, the PSII supercomplex has a lower Chl a/b ratio and shows a higher Chl b peak near 650 nm. Finally, the presence of low-energy Chls which absorb at wavelengths above those of P700 is unique in PSI (Croce et al. 1996);

-

-

involvement in water splitting: this process is only associated with PSII, as it generates a strong oxidant (P680+) necessary to carry out the thermodynamically not favoured process of water oxidation.

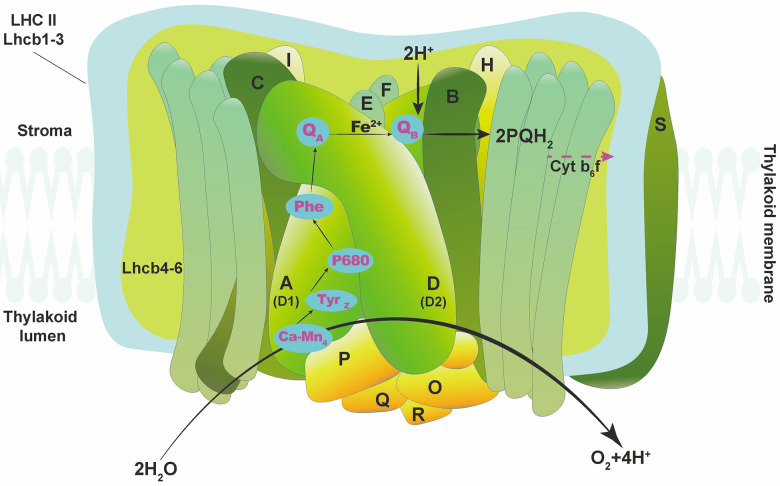

PSII is a large membrane–protein complex located in the thylakoids of the chloroplast of many organisms, from cyanobacteria to higher plants. It is a very organized complex that contains 20 subunits (17 transmembrane subunits and three membrane-peripheral extrinsic subunits) (Müh and Zouni 2020). Among the transmembrane subunits, proteins D1 and D2 constitute the reaction centre core of PSII directly associated with all cofactors involved in electron-transfer and water-splitting reactions (Ferreira et al. 2004, Umena et al. 2011, Büchel 2015, Müh and Zouni 2020). Other subunits surround the D1 (also known as photosystem A or PsbA) and D2 subunits and in particular, CP47 and CP43 in which the acronyms CP stands for Chl–protein complex having an important role in binding Chl molecules with the function of an inner light-harvesting complex. All these intrinsic proteins are encoded by chloroplast DNA. The proteins D1 and D2 bind Chls, pheophytin, plastoquinones, β-carotenes, and Fe whereas CP43 and CP47 bind only Chls and β-carotenes (Pospíšil and Yamamoto 2017, Müh and Zouni 2020). The other 13 transmembrane subunits with low molecular mass are PsbE, PsbF, PsbH, PsbI, PsbJ, PsbK, PsbL, PsbM, PsbT, PsbX, PsbY, PsbZ, and Psb30 (Shen et al. 2008, Umena et al. 2011, Müh and Zouni 2020). Finally, in plants and algae the three membrane-peripheral extrinsic proteins (PsbO, PsbP, and PsbQ), associated with the luminal side of PSII, are necessary to maintain the water-splitting reactions (Roose et al. 2007, Enami et al. 2008, Ifuku 2014, Shen 2015). The basic structure of PSII is reported in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Simplified structure of photosystem II (PSII) intrinsic and extrinsic proteins. Ca-Mn4 – calcium-manganese cluster of oxygen evolving complex; Cyt b6f – cytochrome b6f; D1 – D1 protein; D2 – D2 protein; LHC II – light-harvesting complex of photosystem II; protein TyrZ – tyrosine-161 of D1 protein; Phe – pheophytin; PQH2 – mobile plastoquinone molecule; QA, QB – primary and secondary plastoquinone electron acceptors; P680 – core of photosystem II reaction center; A, B, C, D – intrinsic proteins of photosystem II; E, F, H, O, P, Q, R – extrinsic proteins of photosystem II.

Associated with the core complex, there is a peripheral-antenna system represented by a trimeric light-harvesting complex, the major antenna of PSII, and three monomers, the minor light-harvesting complex, named CP29, CP26, and CP24. These LHC complexes coordinate Chl a and b and several xanthophylls (Xu et al. 2017) and are associated with dimeric PSII cores to form PSII supra-complexes. Finally, a nucleus-encoded PsbS protein is a ΔpH-dependent kinetic modulator of the energy dissipation process in the LHCII, namely qE suggested to be the major component of NPQ under high-light conditions (Li et al. 2000) The supercomplexes PSII–LHCII form semi-crystalline arrays in the thylakoid membrane (Dekker and Boekema 2005, Rantala et al. 2020) and are abundant in the stacked grana, but absent in the unstacked thylakoid membranes.

Alteration of PSII components under stress

Light represents the pivotal factor in driving photosynthesis but, the irony of fate, an excess of light can also cause damage to the photosynthetic apparatus (Barber and Andersson 1992). Excess light induces a decline in photosynthetic performance, thus resulting in an excess of excitation energy at the chloroplast level (Bassi and Dall'Osto 2021). Therefore, plants must continuously balance the energy absorbed and utilized, basically adjusting the leaf light interception and dissipation by the photosynthetic pigment. The energy excess leads to a reduction in PSII activity and the electron transport chain becomes over-reduced (Nishiyama et al. 2001, Roach and Kreiger-Liszkay 2014, Alric and Johnson 2017, Barbato et al. 2020).

However, plants have evolved several photoprotective mechanisms against situations of light excess. One of these mechanisms is the nonphotochemical energy dissipation associated with the nonphotochemical quenching (NPQ) of Chl fluorescence, which absolves the key role of reducing the amount of excited PSII Chl molecules under stressful conditions (Cazzaniga et al. 2013, Gururani et al. 2013, Murchie and Ruban 2020). NPQ consists of three components, described by the relaxation kinetics in dark conditions following an illumination period (Horton et al. 1996, Kress and Jahns 2017). The major and fast-released (within seconds to minutes) component is qE, which is related to the increase in the ΔpH across the thylakoid membrane in the presence of PsbS and zeaxanthin (Horton et al. 1996, Ruban and Wilson 2021). The second component that relaxes slower than qE, qT, is attributable to the reversible phosphorylation of the LHCII that determines the state transition II–I (Quick and Stitt 1989, Kress and Jahns 2017). Finally, the third component, qI, relaxes very slowly in time due to photoinhibition (Matsubara and Chow 2004, Nawrocki et al. 2021). There is another component, the long-lasting zeaxanthin-dependent quenching that occurs under certain environmental conditions (Demmig-Adams et al. 1998). This component, named qZ, has been directly attributed to zeaxanthin accumulation and in particular to its binding to LHC protein specifically LHCb5 (Dall'Osto et al. 2005, Bassi and Dall'Osto 2021) and this component does not require a low lumen pH nor PsbS and thus does not represent a zeaxanthin-dependent qE component (Nilkens et al. 2010, Kress and Jahns 2017).

As above reported, the nuclear-encoded PsbS protein plays a crucial role in the dissipation of excess light energy absorbed by PSII–LHCII into heat and, in this way, in the formation of nonphotochemical quenching qE (Li et al. 2000, Bassi and Dall'Osto 2021). Kereïche et al. (2010) reported that this role is induced by the ability to control the macro-organization of the grana membranes in the chloroplast of higher plants. It has been also reported that PsbS, with the location of this protein in thylakoid membranes, is a mobile protein in the membranes (Teardo et al. 2007) and that its location is due to a reversible dimerization (Bergantino et al. 2003). However, Nicol et al. (2019) using an Arabidopsis mutant lacking LHCII trimers (NoLHCII), observed a decrease in NPQ of around 60% but the authors did not observe significant changes to the levels of PsbS, zeaxanthin or grana stacking and attributed the decrease in NPQ to the observed lack of upregulation of the minor antenna complexes and the absence of LHC trimers in the NoLHCII plants. From their results, the authors concluded that the majority of NPQ occurs in LHCII, but there is an additional site of PsbS-dependent quenching in the PSII core, most likely in the core antenna complexes CP43 and/or CP47.

During abiotic stress conditions, when the absorbed light exceeds that utilized by the biosynthetic pathways, another negative process is the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the chloroplasts because the electron transport chain (ETC) fails to generate NADPH, whilst directing electrons towards dioxygen in the photorespiration and the Mehler peroxidase reaction (Baker 2008, Bhattacharjee 2019). ROS induces lipid peroxidation and damages PSII proteins at the reaction centre, antenna, and in the membrane near lipid molecules (Sasi et al. 2018). One of the most important adverse effects of ROS generation (and in particular of singlet oxygen) is the damage to the D1 protein; in particular, ROS may not directly damage PSII, but inactivate the repairing mechanisms of PSII (Allakhverdiev and Murata 2004, Nishiyama et al. 2004, Pinnola and Bassi 2018, Zavafer 2021). Indeed, in addition to the NPQ photoprotective mechanism, plants have developed an efficient PSII repairing mechanism aimed to preserve PSII from irreversible damage in conditions of excessive excitation energy (Nath et al. 2013a, Weisz et al. 2019). The PSII repairing cycle is a process in which the D1 protein is phosphorylated, dephosphorylated, and degraded by the action of a specific kinase (STN8; Nath et al. 2013b), phosphatase (PBCP; Samol et al. 2012), and protease (FtsHs and DEGs; Sun et al. 2007, Edelman and Mattoo 2008), respectively, and finally D1 is newly resynthesized and reassembled in the PSII (Tikkanen and Aro 2014, Weisz et al. 2019).

In addition to excess light, other environmental stresses can lead to photoinhibition, even though not directly, but rather by facilitating the inhibition of the PSII repairing mechanisms (Murata et al. 2007, Nishiyama and Murata 2014, Li et al. 2018). It has been widely reported as both photoinhibition and ROS, such as superoxide anion and singlet oxygen, induced by different abiotic stresses, e.g., high or low temperature (Allakhverdiev and Murata 2004, Takahashi et al. 2009, Mattila et al. 2020), salinity (Allakhverdiev and Murata 2004, He et al. 2021, Pan et al. 2021), and constrained CO2 fixation (Wang et al. 2014, Foyer 2018), can inhibit the translation of psbA mRNA and inactivate in this way the PSII repairing process. Finally, ROS can irreversibly alter the protein structure through the carbonylation process (Johansson et al. 2004, Akagawa 2021). Although photoprotective mechanisms can scavenge ROS, when the stress overcomes the protection mechanisms, protein oxidation can induce PSII protein cleavage and aggregation (Kale et al. 2017, Pospíšil and Yamamoto 2017).

In photoinhibition conditions, slight phosphorylation of PSII results in efficient photochemistry of LHCII and slower damage to PSII (Tikkanen et al. 2010, Tikkanen and Aro 2014, Wu et al. 2021a). In fact, in these conditions, no net damage to PSII occurs and a moderate amount of energy is transferred to PSI because phosphorylated LHCIIs move to the grana margins. However, when light is in excess and PSII proteins are phosphorylated at a very high rate, the PSII–LHCII supercomplex loses its structural integrity and the energy transfer toward PSI is unregulated (Tikkanen et al. 2010, Tikkanen and Aro 2014, Grinzato et al. 2020).

In addition, the PSII photoinhibition represents also a mechanism by which PSII can protect PSI from irreversible damage; Tikkanen et al. (2014) proposed that the regulation of PSII photoinhibition is the ultimate regulator of the photosynthetic electron transfer chain and provides a photoprotection mechanism against the formation of ROS and photodamage in PSI. In a general way, it is possible that slowing down PSII photochemistry but also the redox chemistry can function as a protection system for the photosynthetic machinery against photodamage (Tikkanen et al. 2012).

An important aspect is a balance between the damage and repair of PSII, which represents the most dynamically regulated part of the light reactions in the thylakoid membrane (Tikkanen et al. 2008, Rantala et al. 2020). In addition to the phosphorylation process of LHCII, the PSII core proteins D1, D2, CP43, PsbH, and TSP9 can also be subjected to dynamic phosphorylation (Rochaix 2007, Johnson and Wientjes 2020), strictly related to the regulation of PSII turnover upon photodamage (Aro et al. 1993, Longoni and Goldschmidt-Clermont 2021). Even in moderate light conditions, the high oxidant power of P680+ can induce photodamage to the D1 protein; so, the dynamic degradation of the damaged D1 protein and its de novo synthesis and insertion in the PSII core is one of the prerequisites for aerobic organisms (Aro et al. 2005, Chen et al. 2020). In the past, it was postulated that the phosphorylation of the damaged D1 protein represents in plants a signal for migration of the damaged PSII from the grana to stroma lamellae where D1 is degraded, resynthesized, and inserted in the PSII (Aro et al. 1993). More recently it has been reported that the processes of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation in plants are not a key element for the D1 turnover (Bonardi et al. 2005) even though the PSII core phosphorylation facilitates the disassembly of the PSII–LHCII supercomplexes (Tikkanen et al. 2008, Fristedt et al. 2009) to increase the mobility of the PSII from grana to stroma lamellae under photoinhibition conditions (Rantala et al. 2020).

Using the Arabidopsis mutants with impaired capacity (stn8) or complete lack (stn7 stn8) in phosphorylation of PSII core proteins, Tikkanen et al. (2008) concluded that after the migration towards stroma thylakoids of the phosphorylated PSII core, a phosphatase, activated by the release of the CYP38 protein, dephosphorylates the damaged D1. In turn, D1 resulted as more susceptible to the degradation operated by a D1-specific protease. The protease FtsH (Adam and Sakamoto 2014) and DEG (Sun et al. 2007, Kato et al. 2012) are the two possible candidates for degradation of the D1 protein. Opposing this view, Fristedt et al. (2009) argued that the PSII core phosphorylation instead induces macroscopic rearrangements to the thylakoid membrane and allows the PSII repair cycle by decreasing the membrane cohesion. The different hypotheses on the roles of PSII core protein phosphorylation are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

PSII repair cycle: the role of extrinsic proteins PsbO, PsbP, PsbQ, and PsbR

The extrinsic proteins PsbO, PsbP, PsbQ, and PsbR (33, 23, 18, and 10 kDa, respectively) play a key role in maintaining the cluster of oxygen-evolving complex (OEC) represented by four Mn atoms, one Ca atom and five oxygen atoms (CaMn4O5). This structure is evolutionary conserved and identical from cyanobacteria to various algae and higher plants and dates back to 2.4 billion years ago (Vinyard et al. 2013). An important role of the extrinsic protein PsbO, PsbP, and PsbQ, located at the luminal side, is the protection of the OEC under stress (Roose et al. 2007). For example, salinity harms the Mn cluster of OEC which induces a reduction of PSII activity (Allakhverdiev and Murata 2004). PsbO is very important in stabilizing the OEC (Popelkova and Yocum 2011) while the PsbP protein plays a role in optimizing Ca2+ and Cl− availability for maintaining the Mn–Ca2+–Cl− cluster of OEC (Bricker et al. 2013). In addition, the correct functioning of PsbQ requires the presence of Cl– ions at low concentrations (< 3 mM) (Tomita et al. 2009). In addition to PsbO, PsbP, PsbQ, another protein, the 10-kDa PsbR protein, has been found in green algae structures and plant PSII and is involved in the protection of OEC in high-light conditions maintaining the standard rate of oxygen evolution (Suorsa et al. 2006). Its absence induces a strong decrease in oxygen evolution particularly in plants grown in low-light conditions (Suorsa et al. 2006).

In both high and low-temperature conditions, the PSII complex is the most susceptible part of the photosynthetic apparatus and in these stressed conditions, the extrinsic proteins PsbP, PsbQ, and PsbR disassociate from the OEC complex of PSII (Gupta et al. 2021).

Many other stresses can alter the structure and functionality of PSII proteins. For example, Wu et al. (2021b) recorded the inhibition of the photosynthetic process in plants of Phragmites australis grown at high Cu concentrations related to a reduction in both Chl a and b contents but also a downregulation in the expression of PsbD, PsbO, and PsaA. Other trace elements such as Cd and Cr at toxic concentration induced negative effects on the structure of thylakoid complexes in Chlorella variabilis attributable to the generated oxidative stress (Zsiros et al. 2020). However, the mechanisms involved for the two elements are different: Cd induced the inhibition of PSII activity via degradation of PsbO (and also PsbA) proteins while the negative effects of Cr were due to the inhibition on the PSII side.

In addition, in the repair cycle of PSII, i.e., in the D1 turnover, a key role is played by the extrinsic PSII proteins PsbO, PsbP, and PsbQ (Bricker et al. 2012). The mutation and absence of the PsbO subunit render PSII more vulnerable to photoinhibition (Henmi et al. 2004, Sasi et al. 2018), and Yamamoto et al. (2008) reported that PsbO is of utmost importance in protecting the structure of D1 from ROS production.

Some plant species only possess one PsbO isoform (Oryza sativa and Pisum sativum) whereas other species such as potato and Arabidopsis have two isoforms of PsbO (Sasi et al. 2018). The role of PsbO protein against photodamage during different abiotic stress has been reported. In particular, PsbO preserved and stabilized the PSII during drought stress (Pawłowicz et al. 2012) but this protein was partially degraded during cold treatment (Kosmala et al. 2009). Many researchers used PsbO mutants under abiotic stress conditions and sometimes they obtained contrasting results (Murakami et al. 2005, Dwyer et al. 2012, Gururani et al. 2012, 2013); in addition, there were also contrasting results between PsbO expression and plant growth under stress conditions (Pawłowicz et al. 2012, Gururani et al. 2013) likely attributable to the presence of different isoforms of PsbO in different plant species (Sasi et al. 2018). PsbO has also a function as a putative enzymatic GTPase regulating the phosphorylation state of the D1 process, the event associated with an efficient turnover of the D1 protein during the repairing mechanism (Bricker and Frankel 2011).In addition to PsbO, the other extrinsic proteins, PsbP and PsbQ play an important role in stabilizing the architecture of LHCII supercomplexes in higher plants; in particular, PsbO and PsbP under normal growth conditions (Ifuku et al. 2005, Che et al. 2020) and PsbQ during growth at low light intensity (Yi et al. 2006). The protein PsbP is important to maintain the Mn–Ca2+–Cl– cluster within PSII (Seidler 1996, Ifuku and Nagao 2021) and some homologs of this protein are present in the thylakoid lumen (e.g., the PsbP-like proteins PPL1 and 2) (Ishihara et al. 2007, Matsui et al. 2013). These PPL1 and 2 of PSII are involved in the response of photosynthesis under stress conditions. For example, Ishihara et al. (2007) reported that a ppl1 mutant of Arabidopsis was more sensitive to high-intensity light than the wild type, and the recovery of PSII activity after photoinhibition was delayed in ppl1 plants. On the other hand, Ishihara et al. (2007) also demonstrated that PPL2 is a novel thylakoid lumenal factor required for the accumulation of the chloroplast NADH dehydrogenase complex.

PsbP with PsbQ proteins are strictly involved in the association of peripheral antennae to PSII, a process extremely dynamic that adjusts the photosynthetic light reactions to environmental changes (Cao et al. 2018). In particular, PsbP protein represents an assembly and/or stability factor for PSII in cyanobacteria (Knoppová et al. 2016) but also in higher plants (Bricker et al. 2012, 2013).

Extrinsic protein PsbQ, together with PsbP, are responsible for the interactions with both PSII intrinsic and light-harvesting complex (Ido et al. 2014, Cao et al. 2018) and other studies revealed that PsbQ can replace the N-terminal PsbP functional defect and in this way is involved in the PsbP stabilization in PSII (Ifuku et al. 2005). On the other hand, the PsbQ is required at low Cl− concentrations (< 3 mM) for oxygen evolution (Miyao and Murata 1985, Gupta 2020).

In conclusion, the extrinsic proteins in PSII play a major role to protect the oxygen-evolving complex and, until now, few reports have indicated the possible role of abiotic stresses on these proteins. It is, however, underlined as changes in the expression of these extrinsic proteins dramatically decrease the PSII efficiency or change the repair PSII mechanisms (Sasi et al. 2018).

In addition, it has been proposed that PsbP is involved in binding manganese which is essential for photoactivation (Bondarava et al. 2007, Schmidt and Husted 2019) and, together with PsbQ protein, participates in grana stack formation (Anderson et al. 2008). Finally, the removal of PsbP protein induces defects at the reducing side of the PSII because significantly slows the rate of electron transport from QA to QB (Roose et al. 2010).

Other low-molecular-mass proteins associated with PSII

In addition to the above reported in the PSII, there is a large number of proteins for which not much information about their role has been reported. Close to D2 protein, the PsbE and PsbF, α- and β-subunits of Cyt b559, function as a safety valve to remove the excessive oxidative hole from the PSII donor side (Shevela et al. 2021). Cyt b559 plays a protective role for the donor and acceptor side of PSII reaction centres against photoinhibition as evidenced by Chu and Chiu (2016) in site-direct mutagenesis studies that provide evidence for a possible physiological role of Cyt b559 in the assembly and stability of PSII, protecting PSII against photoinhibition and modulating photosynthetic light harvesting.

Another plastome-encoded protein PsbH is reported in higher plants; it contributes to Chl-binding protein 43 kDa (CP43) in the formation of the inner LHC (Barber et al. 1997). This protein is a determinant of PSII activity but plays also a role in regulating PSII assembly/stability and repair of photodamaged PSII (Shi and Schröder 2004) and in protecting the PSII core and the thylakoid membrane from oxidative damage (Huang et al. 2016).

The PsbI protein, again a plastome-encoded protein, is located at the periphery of the reaction centre and strictly related to the core antenna protein CP43, is close to ChlZ(D1) and binds to D1 (Nield and Barber 2006, Pagliano et al. 2013). Studies with tobacco plants, in which the PsbI gene was deleted, demonstrated the importance of the PsbI protein for PSII functioning and the stabilization of PSII dimers and supercomplexes (Schwenkert et al. 2006). This seems to indicate that this subunit can play a role in the connection between the inner antenna CP43 and the outer antenna CP29 (Dekker and Boekema 2005).

Adjacent to the PsbE and PsbF proteins of Cyt b559 is located also the PsbJ protein; altogether these proteins form a channel for the diffusion of PQ/PQH2 involved in the PQ pool (Guskov et al. 2009).

Concluding remarks

Photosynthetic light absorption generates the P680+, a strong oxidant able to oxidize water in the OEC, a complex that is protected and stabilized by extrinsic proteins. These proteins play a key role in stabilizing the PSII that represents the most vulnerable components in the photosynthetic machinery. Nevertheless, little information is on the role of these proteins in the plant abiotic stress responses. In this review, the state of the art about the information on the effects of abiotic stresses on PSII protein is reported in an attempt to summarize existing information on the topic and stimulate further research on the matter.

Acknowledgements

The authors are extremely thankful to Prof. Claudia Büchel for the critical revision of the manuscript and her insightful comments and suggestions. The authors are also thankful to Dr. Ermes Lo Piccolo for the graphical support in figure realization.

Abbreviations

- Chl

chlorophyll

- ETC

electron transport chain

- LHC

light-harvesting complex

- NPQ

nonphotochemical quenching

- OEC

oxygen-evolving complex

- qE

energy gradient quenching

- qI

photoinhibition quenching

- qT

state II–I transition quenching

- qZ

zeaxanthin-dependent quenching

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Adam Z., Sakamoto W.: Plastid proteases. – In: Theg S., Wollman F.A. (ed.): Plastid Biology. Advances in Plant Biology. Pp. 359-389. Springer, New York: 2014. 10.1007/978-1-4939-1136-3_14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akagawa M.: Protein carbonylation: molecular mechanisms, biological implications, and analytical approaches. – Free Radic. Res. 55: 307-320, 2021. 10.1080/10715762.2020.1851027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allakhverdiev S.I., Murata N.: Environmental stress inhibits the synthesis de novo proteins involved in the photodamage–repair cycle of photosystem II in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. – BBA-Bioenergetics 1657: 23-32, 2004. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alric J., Johnson X.: Alternative electron transport pathways in photosynthesis: a confluence of regulation. – Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 37: 78-86, 2017. 10.1016/j.pbi.2017.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J.M., Chow W.S., De Las Rivas J.: Dynamic flexibility in the structure and function of Photosystem II in higher plant thylakoid membranes: the grana enigma. – Photosynth. Res. 98: 575-587, 2008. 10.1007/s11120-008-9381-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aro E.-M., Suorsa M., Rokka A. et al.: Dynamics of photo-system II: a proteomic approach to thylakoid protein complexes. – J. Exp. Bot. 56: 347-356, 2005. 10.1093/jxb/eri041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aro E.-M., Virgin I., Andersson B.: Photoinhibition of Photosystem II. Inactivation, protein damage and turn over. – BBA-Bioenergetics 1143: 113-134, 1993. 10.1016/0005-2728(93)90134-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker N.R.: Chlorophyll fluorescence. A probe of photosyntheis in vivo. – Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59: 89-113, 2008. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbato R., Tadini L., Cannata R. et al.: Higher order photoprotection mutants reveal the importance of ΔpH-dependent photosynthesis-control in preventing light induced damage to both photosystem II and photosystem I. – Sci. Rep.-UK 10: 6770, 2020. 10.1038/s41598-020-62717-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber J., Andersson B.: Too much of a good thing: light can be bad for photosynthesis. – Trends Biochem. Sci. 17: 61-66, 1992. 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90503-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber J., Nield J., Morris E.P. et al.: The structure, function and dynamics of photosystem two. – Physiol. Plantarum 100: 817-827, 1997. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1997.tb00008.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bassi R., Dall'Osto L.: Dissipation of light energy absorbed in excess: the molecular mechanisms. – Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 72: 47-76, 2021. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-071720-015522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergantino E., Segalla A., Brunetta A. et al.: Light- and pH-dependent structural changes in the PsbS subunit of photosystem II. – P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 15265-15270, 2003. 10.1073/pnas.2533072100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee S.: ROS and oxidative stress: origin and implication. – In: Bhattacharjee S. (ed.): Reactive Oxygen Species in Plant Biology. Pp. 1-31. Springer, New Delhi: 2019. 10.1007/978-81-322-3941-3_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonardi V., Pesaresi P., Becker T. et al.: Photosystem II core phosphorylation and photosynthetic acclimation require two different protein kinases. – Nature 437: 1179-1182, 2005. 10.1038/nature04016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondarava N., Un S., Krieger-Liszkay A.: Manganese binding to the 23 kDa extrinsic protein of Photosystem II. – BBA-Bioenergetics 1767: 583-588, 2007. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker T.M., Frankel L.K.: Auxiliary functions of the PsbO, PsbP and PsbQ proteins of higher plant Photosystem II: A critical analysis. – J. Photoch. Photobio. B 104: 165-178, 2011. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2011.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker T.M., Roose J.L., Fagerlund R.D. et al.: The extrinsic proteins of Photosystem II. – BBA-Bioenergetics 1817: 121-142, 2012. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker T.M., Roose J.L., Zhang P., Frankel L.K.: The PsbP family of proteins. – Photosynth. Res. 116: 235-250, 2013. 10.1007/s11120-013-9820-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büchel C.: Evolution and function of light harvesting proteins. – J. Plant Physiol. 172: 62-75, 2015. 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffarri S., Tibiletti T., Jennings R.C., Santabarbara S.: A comparison between plant photosystem I and photosystem II architecture and functioning. – Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 15: 296-331, 2014. 10.2174/1389203715666140327102218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao P., Su X., Pan X. et al.: Structure, assembly and energy transfer of plant photosystem II supercomplex. – BBA-Bioenergetics 1859: 633-644, 2018. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazzaniga S., Dall'Osto L., Kong S.G. et al.: Interaction between avoidance of photon absorption, excess energy dissipation and zeaxanthin synthesis against ohotooxidative stress in Arabidopsis. – Plant J. 76: 568-579, 2013. 10.1111/tpj.12314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che Y., Kusama S., Matsui S. et al.: Arabidopsis PsbP-like protein 1 facilitates the assembly of the Photosystem II supercomplexes and optimizes plant fitness under fluctuating light. – Plant Cell Physiol. 61: 1168-1180, 2020. 10.1093/pcp/pcaa045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.-H., Chen S.-T., He N.-Y. et al.: Nuclear-encoded synthesis of the D1 subunit of photosystem II increases photosynthetic efficiency and crop yield. – Nat. Plants 6: 570-580, 2020. 10.1038/s41477-020-0629-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu H.-A., Chiu Y.-F.: The roles of cytochrome b559 in assembly and photoprotection of Photosystem II revealed by site-directed mutagenesis studies. – Front. Plant Sci. 6: 1261, 2016. 10.3389/fpls.2015.01261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croce R., Zucchelli G., Garlaschi F.M. et al.: Excited state equilibration in the photosystem I-light-harvesting I complex: P700 is almost isoenergetic with its antenna. – Biochemistry-US 35: 8572-8579, 1996. 10.1021/bi960214m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dall'Osto L., Caffarri S., Bassi R.: A mechanism of nonphotochemical energy dissipation, independent from PsbS, revealed by a conformational change in the antenna protein CP26. – Plant Cell 17: 1217-1232, 2005. 10.1105/tpc.104.030601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker J.P., Boekema E.J.: Supramolecular organization of thylakoid membrane proteins in green plants. – BBA-Bioenergetics 1706: 12-39, 2005. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demmig-Adams B., Moeller D.L., Logan B.A., Adams III W.W.: Positive correlation between levels of retained zeaxanthin + antheraxanthin and degree of photoinhibition in shade leaves of Schefflera arboricola (Hayata) Merrill. – Planta 205: 367-374, 1998. 10.1007/s004250050332 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer S., Chow W., Yamori W. et al.: Antisense reductions in the PsbO protein of photosystem II leads to decreased quantum yield but similar maximal photosynthetic rates. – J. Exp. Bot. 63: 4781-4795, 2012. 10.1093/jxb/ers156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman M., Mattoo A.K.: D1-protein dynamics in photosystem II: the lingering enigma. – Photosynth. Res. 98: 609-620, 2008. 10.1007/s11120-008-9342-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enami I., Okumura A., Nagao R. et al.: Structures and functions of the extrinsic proteins of photosystem II from different species. – Photosynth. Res. 98: 349-363, 2008. 10.1007/s11120-008-9343-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira K.N., Iverson T.M., Maghlaoui K. et al.: Architecture of the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving center. – Science 303: 1831-1838, 2004. 10.1126/science.1093087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyer C.H.: Reactive oxygen species, oxidative signaling and the regulation of photosynthesis. – Environ. Exp. Bot. 154: 134-142, 2018. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristedt R., Willig A., Granath P. et al.: Phosphorylation of photosystem II controls functional macroscopic folding of photosynthetic membranes in Arabidopsis. – Plant Cell 21: 3950-3964, 2009. 10.1105/tpc.109.069435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinzato A., Albanese P., Marotta R. et al.: High-light versus low-light: effects on paired Photosystem II supercomplex structural rearrangement in pea plants. – Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21: 8643, 2020. 10.3390/ijms21228643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R.: The oxygen-evolving complex: a super catalyst for life on earth, in response to abiotic stresses. – Plant Signal. Behav. 15: 1824721, 2020. 10.1080/15592324.2020.1824721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R., Sharma R.D., Rao Y.R. et al.: Acclimation potential of Noni (Morinda citrifolia L.) plant to temperature stress is mediated through photosynthetic electron transport rate. – Plant Signal. Behav. 16: 1865687, 2021. 10.1080/15592324.2020.1865687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gururani M.A., Upadhyaya C.P., Strasser R.J. et al.: Physiological and biochemical responses of transgenic potato plants with altered expression of PSII manganese stabilizing protein. – Plant Physiol. Bioch. 58: 182-194, 2012. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2012.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gururani M.A., Upadhyaya C.P., Strasser R.J. et al.: Evaluation of abiotic stress tolerance in transgenic potato plants with reduced expression of PSII manganese stabilizing protein. – Plant Sci. 198: 7-16, 2013. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guskov A., Kern J., Gabdulkhakov A. et al.: Cyanobacterial photosystem II at 2.9 Å-resolution and the role of quinones, lipids, channels and chloride. – Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16: 334-342, 2009. 10.1038/nsmb.1559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W., Yan K., Zhang Y. et al.: Contrasting photosynthesis, photoinhibition and oxidative damage in honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica Thunb.) under iso-osmotic salt and drought stresses. – Environ. Exp. Bot. 182: 104313, 2021. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2020.104313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henmi T., Miyao M., Yamamoto Y.: Release and reactive-oxygen-mediated damage of the oxygen-evolving complex subunits of PSII during photoinhibition. – Plant Cell Physiol. 45: 243-250, 2004. 10.1093/pcp/pch027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton P., Ruban A.V., Walters R.G.: Regulation of light harvesting in green plants. – Annu. Rev. Plant Phys. 47: 655-684, 1996. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W., Yang Y.J., Hu H. et al.: Evidence for the role of cyclic electron flow in photoprotection for oxygen-evolving complex. – J. Plant Physiol. 194: 54-60, 2016. 10.1016/j.jplph.2016.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ido K., Nield J., Fukao Y. et al.: Cross-linking evidence for multiple interactions of the PsbP and PsbQ proteins in a higher plant photosystem II supercomplex. – J. Biol. Chem. 289: 20150-20157, 2014. 10.1074/jbc.M114.574822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ifuku K.: The PsbP and PsbQ family proteins in the photosynthetic machinery of chloroplasts. – Plant Physiol. Bioch. 81: 108-114, 2014. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ifuku K., Nagao R.: Evolution and function of the extrinsic subunits of Photosystem II. – In: Shen J.R.., Satoh K., Allakhverdiev S.I. (ed.): Photosynthesis: Molecular Approaches to Solar Energy Conversion. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration. Pp. 429-446. Springer, Cham: 2021. 10.1007/978-3-030-67407-6_16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ifuku K., Yamamoto J., Ono T. et al.: PsbP protein, but not PsbQ protein, is essential for the regulation and stabilization of Photosystem II in higher plants. – Plant Physiol. 139: 1175-1184, 2005. 10.1104/pp.105.068643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara S., Takabayashi A., Ido K. et al.: Distinct function for the two PsbP-like proteins PPL1 and PPl2 in the chloroplast thylakoid lumen. – Plant Physiol. 145: 668-679, 2007. 10.1104/pp.107.105866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson E., Olsson O., Nyström T.: Progression and specificity of protein oxidation in the life cycle of Arabidopsis thaliana. – J. Biol. Chem. 279: 22204-22208, 2004. 10.1074/jbc.M402652200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M.P., Wientjes E.: The relevance of dynamic thylakoid organisation to photosynthetic regulation. – BBA-Bioenergetics 1861: 148039, 2020. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2019.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kale R., Hebert A.E., Frankel L.K. et al.: Amino acid oxidation of the D1 and D2 proteins by oxygen radicals during photoinhibition of Photosystem II. – P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114: 2988-2993, 2017. 10.1073/pnas.1618922114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y., Sun X., Zhang L., Sakamoto W.: Cooperative D1 degradation in the Photosystem II repair mediated by chloroplastic proteases in Arabidopsis. – Plant Physiol. 159: 1428-1439, 2012. 10.1104/pp.112.199042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kereïche S., Kiss A.Z., Kouřil R. et al.: The PsbS protein controls the macro-organisation of photosystem II complexes in the grana membranes of higher plant chloroplasts. – FEBS Lett. 584: 759-764, 2010. 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoppová J., Yu J., Konik P. et al.: CyanoP is involved in the early steps of Photosystem II assembly in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. – Plant Cell Physiol. 57: 1921-1931, 2016. 10.1093/pcp/pcw115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosmala A., Bocian A., Rapacz M. et al.: Identification of leaf proteins differentially accumulated during cold acclimation between Festuca pratensis plants with distinct levels of frost tolerance. – J. Exp. Bot. 60: 3595-3609, 2009. 10.1093/jxb/erp205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress E., Jahns P.: The dynamics of energy dissipation and xanthophyll conversion in Arabidopsis indicate an indirect photoprotective role of zeaxanthin in slowly inducible and relaxing components of non-photochemical quenching of excitation energy. – Front. Plant Sci. 8: 2094, 2017. 10.3389/fpls.2017.02094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Aro E.-M., Millar A.H.: Mechanisms of photodamage and protein turnover in photoinhibition. – Trends Plant Sci. 23: 667-676, 2018. 10.1016/j.tplants.2018.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.P., Björkman O., Shih C. et al.: A pigment-binding protein essential for regulation of photosynthetic light harvesting. – Nature 403: 391-395, 2000. 10.1038/35000131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longoni F.P., Goldschmidt-Clermont M.: Thylakoid protein phosphorylation in chloroplasts. – Plant Cell Physiol. 62: 1094-1107, 2021. 10.1093/pcp/pcab043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui S., Ishihara S., Ido K. et al.: Functional analysis of PsbP-like protein 1 (PPL1) in Arabidopsis. – In: Kuang T., Lu C., Zhang L. (ed.): Photosynthesis Research for Food, Fuel and the Future. Advanced Topics in Science and Technology in China. Pp. 415-417. Springer, Berlin-Heidelberg: 2013. 10.1007/978-3-642-32034-7_86 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara S., Chow W.S.: Populations of photoinactivated photosystem II characterized by Chl fluorescence lifetime in vivo. – P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 18234-18239, 2004. 10.1073/pnas.0403857102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattila H., Mishra K.B., Kuusisto I. et al.: Effects of low temperature on photoinhibition and singlet oxygen production in four natural accessions of Arabidopsis. – Planta 252: 19, 2020. 10.1007/s00425-020-03423-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyao M., Murata N.: The Cl− effect on photosynthetic oxygen evolution: interaction of Cl− with 18-kDa, 24-kDa and 33-kDa proteins. – FEBS Lett. 180: 303-308, 1985. 10.1016/0014-5793(85)81091-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Müh F., Zouni A.: Structural basis of light-harvesting in the photosystem II core complex. – Protein Sci. 29: 1090-1119, 2020. 10.1002/pro.3841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami R., Ifuku K., Takabayashi A. et al.: Functional dissection of two Arabidopsis PsbO proteins: PsbO1 and PsbO2. – FEBS J. 272: 2165-2175, 2005. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04636.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata N., Takahashi S., Nishiyama Y., Allakhverdiev S.I.: Photoinhibition of photosystem II under environmental stress. – Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1767: 414-421, 2007. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murchie E.H., Ruban A.V.: Dynamic non-photochemical quenching in plants: from molecular mechanism to productivity. – Plant J. 101: 885-896, 2020. 10.1111/tpj.14601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath K., Jajoo A., Poudyal R.S. et al.: Towards a critical understanding of the photosystem II repair mechanism and its regulation during stress conditions. – FEBS Lett. 587: 3372-3381, 2013a. 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath K., Poudyal R.S., Eom J.S. et al.: Loss-of-function of OsSTN8 suppresses the photosystem II core protein phosphorylation and interferes with the photosystem II repair mechanism in rice (Oryza sativa). – Plant J. 76: 675-686, 2013b. 10.1111/tpj.12331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrocki W.J., Liu X., Raber B. et al.: Molecular origins of induction and loss of photoinhibition-related energy dissipation qI. – Sci. Adv. 7: eabj0055, 2021. 10.1126/sciadv.abj0055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicol L., Nawrocki W.J., Croce R.: Disentangling the sites of non-photochemical quenching in vascular plants. – Nat. Plants 5: 1177-1183, 2019. 10.1038/s41477-019-0526-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nield J., Barber J.: Refinement of the structural model for the Photosystem II supercomplex of higher plants. – BBA-Bioenergetics 1757: 353-361, 2006. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilkens M., Kress E., Lambrev P. et al.: Identification of a slowly inducible zeaxanthin-dependent component of non-photochemical quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence generated under steady-state conditions in Arabidopsis. – BBA-Bioenergetics 1797: 466-475, 2010. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama Y., Allakhverdiev S.I., Yamamoto H. et al.: Singlet oxygen inhibits the repair of photosystem II by suppressing the translation elongation of the D1 protein in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. – Biochemistry-US 43: 11321-11330, 2004. 10.1021/bi036178q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama Y., Murata N.: Revised scheme for the mechanism of photoinhibition and its application to enhance the abiotic stress tolerance of the photosynthetic machinery. – Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 98: 8777-8796, 2014. 10.1007/s00253-014-6020-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama Y., Yamamoto H., Allakhverdiev S.I. et al.: Oxidative stress inhibits the repair of photodamage to the photosynthetic machinery. – EMBO J. 20: 5587-5594, 2001. 10.1093/emboj/20.20.5587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliano C., Saracco G., Barber J.: Structural, functional and auxiliary proteins of photosystem II. – Photosynth. Res. 116: 167-188, 2013. 10.1007/s11120-013-9803-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan T., Liu M., Kreslavski V.D. et al.: Non-stomatal limitation of photosynthesis by soil salinity. – Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51: 791-825, 2021. 10.1080/10643389.2020.1735231 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pawłowicz I., Kosmala A., Rapacz M.: Expression pattern of the psbO gene and its involvement in acclimation of the photosynthetic apparatus during abiotic stresses in Festuca arundinacea and F. pratensis. – Acta Physiol. Plant. 34: 1915-1924, 2012. 10.1007/s11738-012-0992-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinnola A., Bassi R.: Molecular mechanisms involved in plant photoprotection. – Biochem. Soc. T. 46: 467-482, 2018. 10.1042/BST20170307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popelkova H., Yocum C.F.: PsbO, the manganese-stabilizing protein: Analysis of the structure–function relations that provide insights into its role in photosystem II. – J. Photoch. Photobio. B 104: 179-190, 2011. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2011.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pospíšil P., Yamamoto Y.: Damage to photosystem II by lipid peroxidation products. – BBA-Gen. Subjects 1861: 457-466, 2017. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick W.P., Stitt M.: An examination of the factors contributing to non-photochemical quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence in barley leaves. – BBA-Bioenergetics 977: 287-296, 1989. 10.1016/S0005-2728(89)80082-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rantala M., Rantala S., Aro E.-M.: Composition, phosphorylation and dynamic organization of photosynthetic protein complexes in plant thylakoid membrane. – Photoch. Photobio. Sci. 19: 604-619, 2020. 10.1039/D0PP00025F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach T., Kreiger-Liszkay A.: Regulation of photosynthetic electron transport and photoinhibition. – Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 15: 351-362, 2014. 10.2174/1389203715666140327105143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochaix J.D.: Role of thylakoid protein kinases in photosynthetic acclimation. – FEBS Lett. 581: 2768-2775, 2007. 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roose J.L., Frankel L.K., Bricker T.M.: Documentation of significant electron transport defects on the reducing side of Photosystem II upon removal of the PsbP and PsbQ extrinsic proteins. – Biochemistry-US 49: 36-41, 2010. 10.1021/bi9017818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roose J.L., Wegener K.M., Pakrasi H.B.: The extrinsic proteins of Photosystem II. – Photosynth. Res. 92: 369-387, 2007. 10.1007/s11120-006-9117-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruban A.V., Wilson S.: The mechanism of non-photochemical quenching in plants: localization and driving forces. – Plant Cell Physiol. 62: 1063-1072, 2021. 10.1093/pcp/pcaa155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samol I., Shapiguzov A., Ingelsson B. et al.: Identification of a photosystem II phosphatase involved in light acclimation in Arabidopsis. – Plant Cell 24: 2596-2609, 2012. 10.1105/tpc.112.095703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasi S., Venkatesh J., Daneshi R.F. et al.: Photosystem II extrinsic proteins and their putative role in abiotic stress tolerance in higher plants. – Plants-Basel 7: 100, 2018. 10.3390/plants7040100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S.B., Husted S.: The biochemical properties of manganese in plants. – Plants-Basel 8: 381, 2019. 10.3390/plants8100381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenkert S., Umate P., Dal Bosco C. et al.: PsbI affects the stability, function, and phosphorylation patterns of photosystem II assemblies in tobacco. – J. Biol. Chem. 281: 34227-34238, 2006. 10.1074/jbc.M604888200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler A.: The extrinsic polypeptides of Photosystem II. – BBA-Bioenergetics 1277: 35-60, 1996. 10.1016/S0005-2728(96)00102-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J.R.: The structure of Photosystem II and the mechanism of water oxidation in photosynthesis. – Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 66: 23-48, 2015. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J.R., Henmi T., Kamiya N.: Structure and function of photosystem II. – In: Fromme P. (ed.): Photosynthetic Protein Complexes: A Structural Approach. Pp. 83-106. Wiley-Blackwell, Weinheim: 2008. 10.1002/9783527623464.ch4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shevela D., Kern J.F., Govindjee et al.: Photosystem II. – eLS 2: 1-20, 2021. 10.1002/9780470015902.a0029372 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L.X., Schröder W.P.: The low molecular mass subunits of the photosynthetic supracomplex, photosystem II. – BBA-Bioenergetics 1608: 75-96, 2004. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.W., Peng L.W., Guo J.K. et al.: Formation of DEG5 and DEG8 complexes and their involvement in the degradation of photodamaged photosystem II reaction center D1 protein in Arabidopsis. – Plant Cell 19: 1347-1361, 2007. 10.1105/tpc.106.049510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suorsa M., Sirpiö S., Allahverdiyeva Y. et al.: PsbR, a missing link in the assembly of the oxygen-evolving complex of plant photosystem II. – J. Biol. Chem. 281: 145-150, 2006. 10.1074/jbc.M510600200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S., Whitney S.M., Badger M.R.: Different thermal sensitivity of the repair of photodamaged photosynthetic machinery in cultured Symbiodinium species. – P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106: 3237-3242, 2009. 10.1073/pnas.0808363106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teardo E., de Laureto P.P., Bergantino E. et al.: Evidences for interaction of PsbS with photosynthetic complexes in maize thylakoids. – BBA-Bioenergetics 1767: 703-711, 2007. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikkanen M., Aro E.-M.: Integrative regulatory network of plant thylakoid energy transduction. – Trends Plant Sci. 19: 10-17, 2014. 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikkanen M., Grieco M., Kangasjärvi S., Aro E.-M.: Thylakoid protein phosphorylation in higher plant chloroplasts optimizes electron transfer under fluctuating light. – Plant Physiol. 152: 723-735, 2010. 10.1104/pp.109.150250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikkanen M., Grieco M., Nurmi M. et al.: Regulation of the photosynthetic apparatus under fluctuating growth light. – Philos. T. Roy. Soc. B 367: 3486-3493, 2012. 10.1098/rstb.2012.0067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikkanen M., Mekala N.R., Aro E.-M.: Photosystem II photoinhibition-repair cycle protects Photosystem I from irreversible damage. – BBA-Bioenergetics 1837: 210-215, 2014. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikkanen M., Nurmi M., Kangasjärvi S., Aro E.-M.: Core protein phosphorylation facilitates the repair of photodamaged photosystem II at high light. – BBA-Bioenergetics 1777: 1432-1437, 2008. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita M., Ifuku K., Sato F., Noguchi T.: FTIR evidence that the PsbP extrinsic protein induces protein conformational changes around the oxygen-evolving Mn cluster in Photosystem II. – Biochemistry-US 48: 6318-6325, 2009. 10.1021/bi9006308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umena Y., Kawakami K., Shen J.R., Kamiya N.: Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II at a resolution of 1.9 Å. – Nature 473: 55-60, 2011. 10.1038/nature09913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinyard D.J., Ananyev G.M., Dismukes G.C.: Photosystem II: the reaction center of oxygenic photosynthesis. – Annu. Rev. Biochem. 82: 577-606, 2013. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-070511-100425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Noguchi K., Ono N. et al.: Overexpression of plasma membrane H+-ATPase in guard cells promotes light-induced stomatal opening and enhances plant growth. – P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111: 533-538, 2014. 10.1073/pnas.1305438111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz D.A., Johnson V.M., Niedzwiedzki D.M. et al.: A novel chlorophyll protein complex in the repair cycle of photosystem II. – P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116: 21907-21913, 2019. 10.1073/pnas.1909644116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Ma L., Yuan C. et al.: Formation of light-harvesting complex II aggregates from LHCII–PSI–LHCI complexes in rice plants under high light. – J. Exp. Bot. 72: 4938-4948, 2021a. 10.1093/jxb/erab188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Hu J., Wang L. et al.: Responses of Phragmites australis to copper stress: A combined analysis of plant morphology, physiology and proteomics. – Plant Biol. 23: 351-362, 2021b. 10.1111/plb.13175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P., Roy L.M., Croce R.: Functional organization of photosystem II antenna complexes: CP29 under the spotlight. – BBA-Bioenergetics 858: 815-822, 2017. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2017.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y., Aminaka R., Yoshioka M. et al.: Quality control of photosystem II: impact of light and heat stresses. – Photosynth. Res. 98: 589-608, 2008. 10.1007/s11120-008-9372-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi X., Hargett S.R., Frankel L.K., Brickel T.M.: The PsbQ protein is required in Arabidopsis for Photosystem II assembly/stability and photoautotrophy under low light conditions. – J. Biol. Chem. 281: 26260-26267, 2006. 10.1074/jbc.M603582200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavafer A.: A theoretical framework of the hybrid mechanism of photosystem II photodamage. – Photosynth. Res. 149: 107-120, 2021. 10.1007/s11120-021-00843-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zsiros O., Nagy G., Patai R. et al.: Similarities and differences in the effects of toxic concentrations of cadmium and chromium on the structure and functions of thylakoid membranes in Chlorella variabilis. – Front. Plant Sci. 11: 1006, 2020. 10.3389/fpls.2020.01006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]