ABSTRACT

The authors present guidelines for the ligation of the transverse or sigmoid sinus during the surgical removal of petroclival meningiomas. The medical records and venograms of 14 patients with a petroclival meningioma requiring transverse or sigmoid sinus ligation treated in the Department of Neurosurgery, Seoul National University Hospital between 1986 and 1999 were reviewed. All patients successfully received a sinus trial clamping during the operation. The drainage pattern of the confluens of Herophili was classified into four types: Type A, confluens and equal on both transverse sinuses; Type B, confluens and nondominant transverse sinus on the tumor side; Type C, confluens and dominant transverse sinus on the tumor side; and Type D, unilateral transverse sinus only. Of the 14 cases, four were Type A, five were Type B, and two were Type C. There was no brain swelling after intraoperative test clamping of the sinus for more than 30 minutes. None of the cases developed postoperative complications related to the sinus ligation.

Patients with Type A, B, or C drainage patterns were ideal candidates for sinus ligation, especially transverse sinus ligation, if the test clamping proved to be safe. The sinus was cut proximal to the superior petrosal sinus, distal to the vein of Labbé.

Keywords: Meningioma, transverse sinus, sigmoid sinus

During the past few decades, marked advances have been made in the development of the petrosal approach to petroclival meningiomas. Integral to the application of the petrosal approach to petroclival meningiomas are the manipulation, management, and sacrifice of the transverse or sigmoid sinus. Petroclival meningiomas often become very large before they are diagnosed because they occur relatively infrequently and their growth pattern is insidious. Total resection of these large tumors requires ligation and resection of the sinus to obtain a sufficiently wide exposure of the tumor. Some authors have stated that the transverse or sigmoid sinus should not be ligated due to venous complications.1 The technical difficulty of using the petrosal approach and the likelihood of encountering venous complications depend on the individual's venous anatomy and its variations. We present a guideline for the safe ligation and resection of the sinus.

CLINICAL MATERIALS AND METHODS

We retrospectively analyzed the venograms of 14 patients who underwent transverse or sigmoid sinus ligation (Table 1), a subset of 60 cases diagnosed with petroclival meningiomas between 1986 and 1999. Mean age of the 14 patients (three males, 11 females) was 43 years (range 15–61 years). The mean tumor size was 48 mm (range, 25–90 mm).

Table 1.

Clinical Summary of 14 Patients Undergoing Sinus Ligation

| Patient No./Sex | Age (years) | Approach | Sinus | TCT (min) | Confluens Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1*/F | 50 | ST-IT,TC | S | 30 | B |

| 2/F | 52 | PS-RS,TL | S | 45 | A |

| 3/F | 36 | PS-RS,RR | S | 80 | B |

| 4/M | 50 | PS-RS,RR | S | 60 | B |

| 5/F | 15 | PS-RS,RR | S | — | B |

| 6/M | 38 | PS-RS,TC | S | 60 | A |

| 7/F | 47 | ST-IT,TL | T | 30 | B |

| 8/F | 61 | PS-RS,TL | T | C | |

| 9/F | 44 | ST-IT,TL | T | B | |

| 10/F | 49 | PS-RS,TL | T | 30 | A |

| 11/F | 38 | PS-RS,TL | T | C | |

| 12**/M | 36 | ST-IT,TL | T | ||

| 13**/F | 41 | ST-IT,TL | T | ||

| 14**/F | 51 | PS-RS,TL | T |

F, female; M, male; ST-IT, supratentorial–infratentorial; PS-RS, presigmoid–retrosigmoid; TL, translabyrinth; RR, retrolabyrinth; TC, transcochlear; S, sigmoid; T, transverse; TCT, temporary clipping time.

Reoperation.

Venography is not available.

Surgical Approach

One patient required reoperation for a recurrent tumor. The trans-sigmoid sinus approach was used in six cases, and the trans-transverse sinus approach in eight cases. In all 14 patients, the sinus was ligated and resected. Three types of transpetrosal approaches were performed by an otologist based on the extent of the mastectomy and petrosectomy needed. Three patients underwent a retrolabyrinthine approach, nine underwent a translabyrinthine approach, and two underwent a transcochlear approach. A combined supratentorial–infratentorial approach was performed in five cases, and a combined presigmoid and retrosigmoid approach was performed in nine cases.

Classification of Drainage Patterns

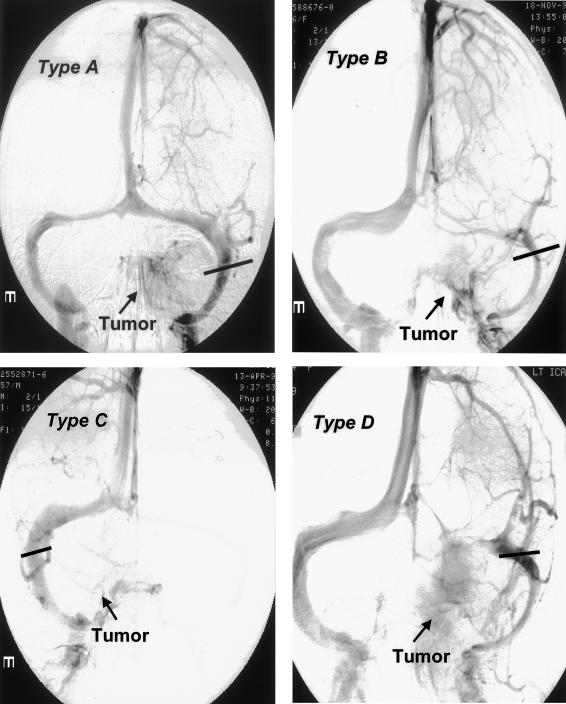

Venograms were reviewed to identify the relative tumor locations and the drainage patterns of the confluens of Herophili. The drainage patterns of the confluens of Herophili were classified into four types (Fig. 1): Type A, confluence and equal on both transverse sinuses; Type B, confluence and nondominant transverse sinus on the tumor side; Type C, confluence and dominant transverse sinus on the tumor side; and Type D unilateral transverse sinus only. Type A was associated with an equal drainage pattern of the transverse sinuses at the confluens of Herophili, irrelevant of tumor location. Type B was associated with a nondominant drainage pattern of the transverse sinuses on the tumor side. Type C was associated with a dominant drainage pattern of the transverse sinuses on the tumor side, and Type D was associated with unilateral drainage only at the confluens of Herophili (i.e., transverse sinus agenesis or hypogenesis). The relationship between the type of drainage pattern and the outcome of ligation and resection of sinus was evaluated.

Figure 1.

Venograms demonstrating the types of confluens of Herophili. Type A: confluence on both transverse sinuses; Type B: confluens and nondominant transverse sinus; Type C: confluens and dominant transverse sinus on tumor side; and Type D: unilateral transverse sinus only. Bars indicate the sinus ligation.

Intraoperative Test Clamping

All of the transverse sinuses were ligated and cut proximal to the superior petrosal sinus, distal to the vein of Labbé. Test clamping was performed with a Yasargil temporary clip. Brain swelling was monitored intraoperatively. The neurological deficits associated with sinus ligation, which were not related to petroclival meningioma resection, were evaluated in all patients. Postoperative computed tomography (CT) was obtained routinely to identify swelling, hemorrhage, and infarction.

RESULTS

Drainage Pattern of the Confluens of Herophili

Of the 14 cases of sinus ligation and resection, four patients had Type A drainage, five had Type B, and two had Type C. Venography was unavailable in three cases. The sigmoid was ligated and resected in six patients, five of whom underwent intraoperative test clamping (see Table 1). The mean test clamping time was 55 minutes (range, 30–80 minutes). No evidence of brain swelling was observed, and no postoperative complications related to sigmoid sinus ligation and resection developed. Of the eight patients who underwent ligation of the transverse sinus, two cases also underwent intraoperative test clamping. The test clamping time was 30 minutes, and no postoperative complications related to sinus ligation and resection were observed.

The transverse sinus was sacrificed proximal to the superior petrosal sinus and distal to the vein of Labbé. Any point in the sigmoid sinus distal to the superior petrosal sinus and vein of Labbé is suitable for ligation.

Illustrative Case

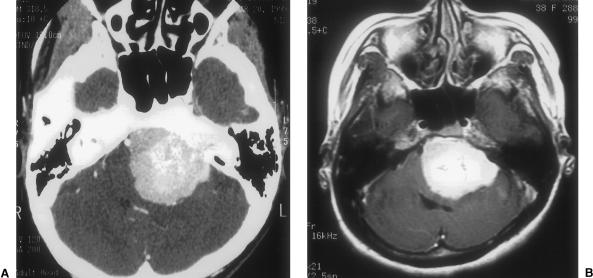

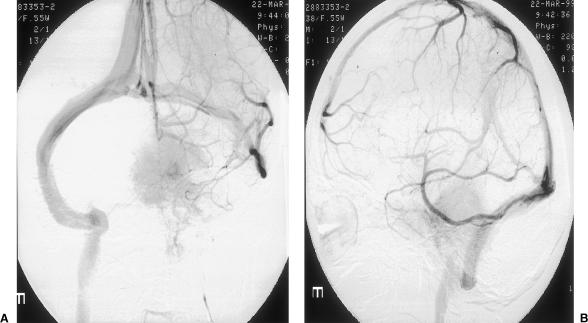

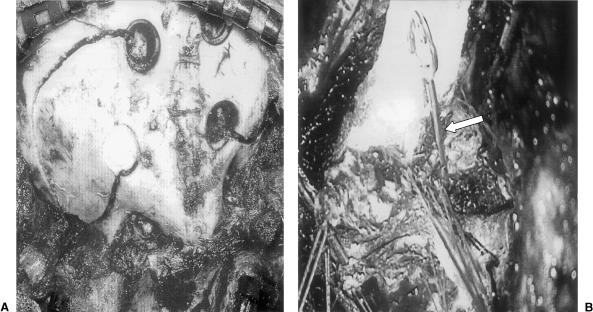

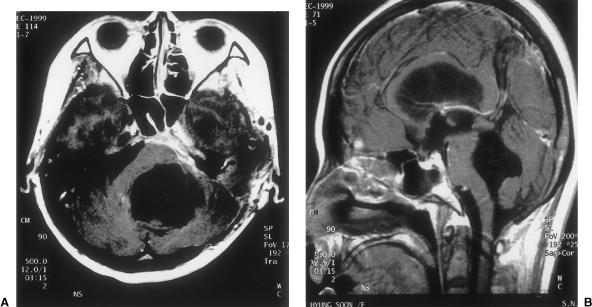

A 37-year-old woman had experienced a gait disturbance for 4 months. On neurological examination, she exhibited hypesthesia on the right side of the face and hearing loss. Preoperative audiometry showed a pure tone threshold of 22 dB and a speech reception threshold of 88% (Gardner-Robertson hearing classification class I). CT and magnetic resonance imaging showed a 5 cm tumor located in the left cerebellopontine angle and extending to the middle and posterior fossae (Fig. 2). Based on the relative location of the tumor and the drainage pattern of the confluens of Herophili on preoperative venography, the patient had a type B (confluens and nondominant tumor side) pattern (Fig. 3). A combined supra- and infratemporal craniotomy and retrolabyrinthine petrosectomy were performed. The sigmoid sinus was ligated and resected after a 30-minute temporary clamp test (Fig. 4). The tumor was resected totally and the patient developed no postoperative neurological deficits (Karnofsky performance scale = 100 [Fig. 5]).

Figure 2.

Temporal bone computed tomography (A) and T1-weighted axial gadolium-enhanced magnetic resonance image (B) showing a 5 cm large tumor located in left cerebellopontine angle and extending to the middle and posterior fossae.

Figure 3.

Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) venograms demonstrating type B pattern (confluens and nondominant on tumor side). The relative location of the tumor and drainage pattern of the confluens of Herophili are good indications for sinus ligation and resection.

Figure 4.

Operative photographs. A combined supra- and infratemporal craniotomy (A) and retrolabyrinth petrosectomy were performed, and the sigmoid sinus was ligated and resected after 30 minutes of temporary clamp testing (B). Arrow indicates a Yasargil temporary clip. Also indicated are the proximal and distal ligation points.

Figure 5.

T1-weighted axial (A) and sagittal (B) gadolium-enhanced magnetic resonance images 1 year after surgery confirming complete resection of the tumor from the right cerebellopontine angle and middle and posterior fossae.

DISCUSSION

Petroclival meningiomas constitute 10% of all meningiomas.1,2 Meningiomas in this region pose a formidable challenge for skull base surgeons because surgical exposure is limited, the anatomy is difficult, and vital neurovascular structures, especially venous structures, are at risk of injury.3,4,5,6,7 Another factor that affects surgical outcome is tumor size. Tumors developing in this region can become very large and spread to multiple compartments before they are diagnosed. Their clinical manifestation can be relatively innocuous.1,8,9

In 1905 Brochardt reported that the sigmoid sinus could be divided to expose cerebellopontine tumors. In 1915 Quix described ligation of the sigmoid sinus to gain additional access to large tumors in the posterior fossa tumor.10 In 1913, Marx used a similar approach; at autopsy, thrombus in the transverse sinus was noted to extend medially from the point of ligature to the confluens of the venous sinus. In 1928 Naffziger mentioned a modification in which the supratentorial occipital craniotomy could be incorporated with a previous suboccipital craniectomy and the transverse sinus ligated to obtain a wide exposure. In 1980 Malis reported his combined suboccipital subtemporal or petrosal approach. He emphasized ligation of the transverse sinus and preservation of blood flow through the vein of Labbé via the contralateral side.1,11

Ligation of the Transverse or Sigmoid Sinus

Indications for ligation and resection of the transverse or sigmoid sinus are controversial. The sigmoid and transverse sinuses can exhibit considerable anatomic variability, especially in terms of being larger than normal or located more anteriorly than normal.8 Some authors have reported immediate or delayed complications (24–48 hours later) caused by sinus ligation and resection. Complications have included infarction and hemorrhage based on intraoperative monitoring systems.10,12 Accordingly, many surgeons have a negative opinion about ligation of the transverse and sigmoid sinuses.

In our experience, however, safe ligation of the sinus can be achieved if the transverse sinus is ligated and cut proximal to the superior petrosal sinus and distal to the vein of Labbé,8,10,11,13,14 and the following conditions are satisfied. First, the contralateral sinus must be patent.1,8,14,15,16 Given equally patent sinuses, the relative size of the sinuses should be assessed by venography or enhanced CT. The smaller sinus should be ligated and resected.10,13,17,18 Finally, patients must pass a preoperative balloon occlusion test or jugular vein compression test as demonstrated by carotid and vertebral artery angiography.9 The first two situations reflect the concept underlying our classification of the drainage pattern of the confluens of Herophili.

Intraoperative Monitoring and Prevention of Complications

Intraoperative monitoring aimed at preventing postoperative deficits has been used as an adjunct to a variety of neurosurgical operations. Intraoperatively, brain stem evoked potentials (BAEPs) and somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs) have been monitored in this region during tumor resection. Bejjani et al monitored intraoperative SSEPs during the resection of cranial base tumors and found that changes in intraoperative SSEPs had a high predictive value. However, the absence of changes in SSEPs did not eliminate the possibility of deficits. The return of SSEPs to baseline predicted neurological recovery in 90% of cases, but not all postoperative deficits were detected.19

Another method of intraoperative monitoring, described by Spetzler and coworkers,14 involved measuring sigmoid sinus pressure after test clamping of the sinus to assess contralateral venous drainage before cutting the sinus. When patency was demonstrated angiographically, intravascular pressure increased no more than 7 mm Hg with ligation of the sigmoid sinus. If pressure in the sigmoid sinus increases more than 10 mm Hg by temporary occlusion testing, the sinus should be kept intact.

Day et al used the transsigmoidal approach to access a basal tip aneurysm. They found that intravascular pressure no greater than 5 mm H2O was safe during test clamping.20 The authors believe that the clinical detection of brain swelling reflects a simulation of the hemodynamics of the venous system after sinus ligation.

In our series, five sigmoid sinuses were ligated after successful test clamping. The maximum test clamping time was 80 minutes. There was no evidence of brain swelling during ligation and no postoperative complications related to sigmoid sinus ligation. Furthermore, there were no complications related to ligation of the transverse sinus in the two patients who also underwent test clamping for 30 minutes during the operation. These results suggest that sinus ligation after test clamping for at least 30 minutes, followed by an intraoperative evaluation of brain swelling is a reliable and safe technique.

CONCLUSIONS

When a wide operative field is needed to access large petroclival meningiomas, the transverse or sigmoid sinus is often ligated. In such cases, we found that the patients with drainage patterns of the confluens of Herophilli of Types A, B, and C were suitable candidates for sinus ligation, if test clamping proved to be safe. In the case of transverse sinus ligation, the sinus was sacrificed proximal to the superior petrosal sinus and distal to the vein of Labbé. Type D drainage pattern at the confluens of Herophili is unsuitable for sinus ligation. Moreover, the identification of brain swelling after intraoperative test clamping of the sigmoid or transverse sinus for more than 30 minutes was a reliable indicator.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by a Seoul National University Hospital Grant and by a Korea Brain and Spinal Cord Research Foundation Grant. The authors are grateful to Miss Mi Sun Park for her assistance with the preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Al-Mefty O, Fox J L, Smith R R. Petrosal approach for petroclival meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1988;22:510–517. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198803000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couldwell W T, Fukushima T, Giannotta S L, Weiss M H. Petroclival meningiomas: surgical experience in 109 cases. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:20–28. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.84.1.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canalis R F, Black K, Martin N, Becker D. Extended retrolabyrinthine transtentorial approach to petroclival lesions. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:6–13. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199101000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C G, Loveren H R van, Keller J T, Pensak M, El-Kalliny M, Tew J M., Jr Transpetrosal approach: surgical anatomy and technique. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:461–469. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199309000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata K, Al-Mefty O, Yamamoto I. Venous consideration in petrosal approach: microsurgical anatomy of the temporal bridging vein. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:153–161. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200007000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanna M, Mazzoni A, Saleh E A, Taibah A K, Russo A. Lateral approaches to the median skull base through the petrous bone: the system of the modified transcochlear approach. J Laryngol Otol. 1994;108:1036–1044. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100128841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhar L N, Wright D C, Richardson R, Monacci W. Petroclival and foramen magnum meningiomas: surgical approaches and pitfalls. J Neurooncol. 1996;29:249–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00165655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantore G, Delfini R, Ciappetta P. Surgical treatment of petroclival meningiomas: experience with 16 cases. Surg Neurol. 1994;42:105–111. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(94)90368-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass S P, Sekhar L N, Pomeranz S, Hirsch B E, Snyderman C H. Excision of petroclival tumors by a total petrosectomy approach. Am J Otol. 1994;15:474–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megerian C A, Chiocca E A, McKenna M J, Harsh G F IV, Ojemann R G. The subtemporal–transpetrous approach for excision of petroclival tumors. Am J Otol. 1996;17:773–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samii M, Tatagiba M. Experience with 36 surgical cases of petroclival meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1992;118:27–32. doi: 10.1007/BF01400723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberg M R, Symon L. Meningiomas of the clivus and apical petrous bone: report of 35 cases. J Neurosurg. 1986;65:160–167. doi: 10.3171/jns.1986.65.2.0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samii M, Ammirati M, Mahran A, Bini W, Sepehrnia A. Surgery of petroclival meningiomas: report of 24 cases. Neurosurgery. 1989;24:12–17. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198901000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spetzler R F, Daspit C P, Pappas C T. The combined supra- and infratentorial approach for lesions of the petrous and clival regions: experience with 46 cases. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:588–599. doi: 10.3171/jns.1992.76.4.0588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhar L N, Pomeranz S, Janecka I P, Hirsch B, Ramasastry S. Temporal bone neoplasms: a report on 20 surgically treated cases. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:578–587. doi: 10.3171/jns.1992.76.4.0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi H, Rhoton A L., Jr Lateral approaches to the petroclival region. Surg Neurol. 1994;41:180–216. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(94)90123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannotta S L, Maceri D R. Retrolabyrinthine transsigmoid approach to basilar trunk and vertebrobasilar artery junction aneurysms. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:461–466. doi: 10.3171/jns.1988.69.3.0461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhar L N, Jannetta P J, Burkhart L E, Janosky J E. Meningiomas involving the clivus: a six-year experience with 41 patients. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:764–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejjani G K, Nora P C, Vera P L, Broemling L, Sekhar L N. The predictive value of intraoperative somatosensory evoked potential monitoring: review of 244 procedures. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:491–500. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199809000-00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day J D, Fukushima T, Giannotta S L. Cranial base approaches to posterior circulation aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:544–554. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.4.0544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]