ABSTRACT

Verrucous carcinomas are rare tumors that predominantly affect the head and neck region. A paradox of slow, aggressive invasion, apparent lymphadenopathy, yet seemingly bland histopathology, they can beguile unwary clinicians into multiple diagnostic biopsies and regional lymphadenectomy. We report a rare verrucous carcinoma of the temporal bone associated with extensive destruction around the skull base. Placed in the context of the few reports involving this site, extratemporal spread may be associated with a uniformly poor prognosis regardless of the treatment modality. Given new insights into the pathophysiology of this tumor, palliative radiotherapy may be a more appropriate primary treatment compared with the significant local morbidity associated with surgery.

Keywords: Carcinoma, verrucous, temporal bone, otitis media

Verrucous carcinomas are unusual, well-differentiated squamous neoplasms that most frequently arise on the mucous membranes of the oral cavity and larynx.1,2 Carcinomas of the middle ear and mastoid are rare3,4,5,6; verrucous carcinomas at this site are exceptionally rare.7,8,9,10,11,12,13 Neglected, these tumors may manifest with extensive local invasion and apparent spread to the regional lymph node basin. We present a patient with an advanced verrucous carcinoma that arose within the temporal bones and caused confusion about its diagnosis and treatment.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

An otherwise healthy 69-year-old woman sought treatment for a mass in the right external auditory meatus and postauricular areas. Its growth had been slow and progressive for at least 1 year. Right-sided otalgia intensified and was associated with a frequent, serosanguinous otorrhoea. She reported undergoing an operation on the right mastoid area at the age of 12 years but was unsure of its relevance. Since then she had noted relative deafness on this side and an episodic discharge of a small volume of purulent fluid for a couple of weeks every year. She had smoked heavily for most of her adult life, quitting years before this episode.

Examination revealed a gray-white, friable mass protruding from the right external auditory meatus (Fig. 1). The postauricular mass was polypoidal with areas of moist ulceration. A retracted tympanic membrane exhibited a dry posterior perforation. Her oropharyngeal examination was unremarkable. She exhibited no cranial nerve deficits or lymphadenopathy.

Figure 1.

Tumor posterior to the right ear and at the external auditory meatus.

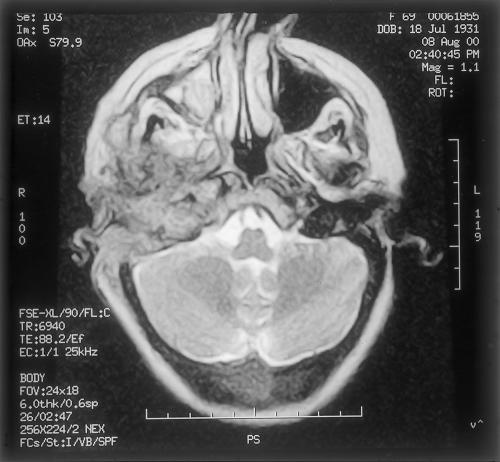

Initial biopsy of both the meatal and postauricular masses revealed severe inflammation with a single, small focus of dysplastic squamous epithelium. One week later another biopsy exhibited similar indefinite features. Computed tomography (CT) (Picker MX8000 multislice; Fig. 2) with and without contrast showed widespread bony destruction on the right side. A soft tissue mass invaded the temporal bone with areas of destruction. The middle ear and inner ear were completely destroyed. The tumor had eroded into the middle and posterior cranial fossae. At the skull base, parapharyngeal spread into the carotid space had encased the carotid artery and jugular vein to the level of the second cervical vertebra. The tumor had also spread anteriorly to the infratemporal fossa and parotid space. There were jugulodigastric and carotid nodal enlargements on the right with a maximum short axis diameter of 1cm. Magnetic resonance imaging (GE Signa 1.5T) using axial T1-weighted, T2-weighted with coronal T1-weighted, 6 mm STIR (short-tau inversion recovery) slices suggested encroachment upon the dura but not into brain tissue (Figs. 3,4,5,6). A posteroanterior chest radiograph showed no evidence of lung metastasis. Liver function tests were normal.

Figure 2.

Axial computed tomography showing middle and inner ear destruction.

Figure 3.

Coronal T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging showing inferomedial extent of tumor.

Figure 4.

Coronal STIR (short-tau inversion recovery) magnetic resonance imaging indicating extracranial extension of tumor into the right posterior neck and small nodal enlargement.

Figure 5.

Axial T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging showing tumor involvement of skull base, petrous temporal ridge, pterygoid fossa, and intracranial extent along the right cerebellum.

Figure 6.

Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging showing tumor's increased and heterogeneous signal indicative of its solid nature.

A definitive histological diagnosis was not obtained before surgery. Given the radiographic findings and site, however, the overriding suspicion favored the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma. In the absence of brain involvement in a relatively healthy patient, it was decided to attempt radical clearance, reconstruction with a muscle flap, and postoperative radiotherapy.

One month after the patient's presentation, a right-sided wide-field petrosectomy and neck dissection were undertaken. Tumor and small abscesses had replaced the temporal bone. Extensive spread along cranial nerves VII, IX, and X at the level of the jugular foramen prevented complete macroscopic clearance. The tumor impinged on the middle and posterior cranial fossae, but intraoperative frozen-section biopsies were reported as inflamed, keratinizing squamous epithelium with no evidence of malignancy. A radical dural clearance was not undertaken. The upper cervical nodes of levels II to V were removed. The en bloc resection specimen revealed verrucous cell carcinoma. Reconstruction was undertaken with a right-sided free rectus abdominis muscle flap that was surfaced with a split skin graft.

As expected the patient exhibited a new facial nerve palsy and a deficient gag and swallow reflex after surgery. Initially, the flap was well perfused but by the seventh day the patient had a prolonged period of septic hypotension. Despite treatment with intravenous antibiotics and vigorous fluid resuscitation, the flap became ischemic and eventually necrotic. After the area was debrided, alternative cover was provided with a right-sided pedicled pectoralis major myocutaneous flap.

The patient's discharge was delayed by two problems. First, her swallowing reflex did not improve and she needed percutaneous gastrostomy feeding. The flap also developed a localized anterior sinus. The persistent discharge of pus prevented healing and hence radiotherapy.

Two months later, the patient was readmitted with severe aspiration pneumonia. She died shortly thereafter. A postmortem examination revealed that tumor had spread into the cerebellum.

HISTOLOGY

The macroscopic specimen was composed of the right pinna with an oval portion of skin (90 × 80 mm). Papillary, thickened white tissue emerged from both the external auditory meatus and posterior to the pinna. Sectioning the specimen revealed a warty white tumor 30 mm in diameter extending into the external auditory meatus.

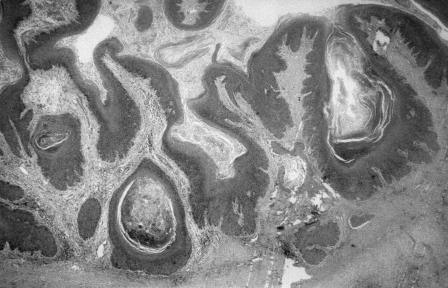

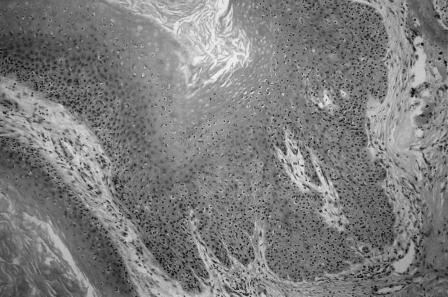

Histologically, the tumor showed markedly papillomatous and hyperkeratotic squamous epithelium (Fig. 7). The tumor extended down into the subepithelial tissue as broad, pushing tongues of atypical squamous epithelium. The epithelium showed moderate cytological atypia with occasional mitoses (Fig. 8). Focal infiltration, bone destruction, peritumoral inflammation, and abscess formation were evident. The histological diagnosis was a well-differentiated verrucous squamous cell carcinoma. The tumor extended to the deep margin of the specimen. Overall, 25 lymph nodes (8 from the fat at the margins of the specimen and 17 from the associated neck dissection) were retrieved. All showed reactive changes with no evidence of metastatic carcinoma.

Figure 7.

Histological features. Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 75×.

Figure 8.

Histological features. Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 220×.

DISCUSSION

Verrucous carcinomas are rare neoplasms with contradictory, benign histology and cytology but markedly invasive clinical behavior. They were first described by Ackerman in 1948.14 They have a predilection for squamous mucosae, particularly those of the head and neck region. They occur most frequently in the larynx and oral mucosa1 but have been found around the genitalia15 and at other cutaneous sites.16 Of the 11 reports of tumor around the ear and temporal bone,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 all but three involved the middle ear or mastoid bone.

Where noted in previous reports, the mean age of patients was 63 years (standard deviation ±12 years) and both sexes were equally affected. As in our case, the most frequently cited symptoms were chronic discharge in seven, deafness in six, and otalgia in four. Facial paralysis was a presenting symptom in two patients. Two patients had other cranial nerve deficits at their initial assessment.7,10 The array of symptoms and signs largely matches those exhibited by all types of cancer of the middle ear,4,6 the predominant type being conventional, nonverrucous squamous cell carcinoma.

The history of our patient is notable for a probable mastoidectomy in childhood followed by lifelong otorrhoea. This sequence occurs in other reports of verrucous carcinoma: six patients had a chronic ear discharge that followed mastoid surgery in three. The mean preceding duration of otorrhoea was 32 years, a duration similar to its occurrence in all types of middle ear cancer.4 Repetitive mechanical trauma such as poorly fitting hearing aids or “picking” at the ear10 may contribute to verrucous carcinoma. This mechanism may parallel the trauma of poorly fitting dentures for oral lesions.14,15 Although our patient had been a longstanding smoker, no previous report of verrucous carcinoma of the ear has detailed cigarette or tobacco usage. However, chewing tobacco seems to be strongly associated with verrucous carcinoma at other sites.15 More recent theories concerning the pathogenesis of verrucous carcinoma include nullification of a tumor suppressor gene17 by types of human papillomavirus.18

The macroscopic appearance of verrucous carcinoma is, “virtually pathognomic.”2 Clearly invasive but not ulcerative, they are typically white-to-gray and warty. These features probably represent the latter stages of a prolonged natural history; for example, oral verrucous carcinomas seem to progress from indolent, circumscribed plaques.1 This report is the first to document marked lymphadenopathy detected by CT. In two other cases of verrucous carcinoma of the ear10,13 and at other sites,15 there was no histological or cytological evidence for metastasis before treatment. Unlike conventional squamous cell carcinomas, verrucous carcinomas do not tend to metastasize. Nevertheless, regional lymphadenopathy may be present as a marker of the florid inflammatory reaction to the tumor.1 Recently, the inflammatory stimulus has been proposed to be tumor-derived cytokines.19 Yet, metastasis from verrucous carcinoma is rare and may be a sequel to radiotherapy20 or even develop de novo.8 Hypothetically, the latter may indicate unrepresentative sampling of a typical squamous cell carcinoma with a verrucoid component, or a genuine anaplastic change.

The microscopic findings for verrucous carcinoma are broadly benign in sharp contrast to its local macroscopic aggressivity. Table 1 compares the reported frequency in the literature of various features thought to characterize verrucous carcinomas.1,2 Often described as a well-differentiated, hyperplastic, and hyperkeratotic squamous epithelium exhibiting little cellular atypia, verrucous carcinomas often mimic reactive or virally induced lesions. This profile may lead to a benign diagnosis and further biopsies by the incredulous surgeon.15 In the 11 reported cases of verrucous carcinoma of the ear, the exact diagnosis was not made from the first pathology specimen in seven. It behooves surgeons to convey to the pathologist both the invasiveness of the lesion and a suitable full-thickness biopsy.

Table 1.

Features* Characterizing All Verrucous Carcinomas Compared with Those of Verrucous Carcinomas Arising around the Ear and Temporal Bone1,2

| Features* | No. of Reports in 11 Cases |

|---|---|

| Macroscopically excessive keratin or microscopic hyper- and parakeratosis | 9 |

| Macroscopically exophytic or fungating | 7 |

| Absent or few cytological features of malignancy | 6 |

| Invading border blunt and “pushing” | 5 |

| Hyperplastic squamous epithelium | 5 |

| Pronounced filiform projections (“spires”) | 5 |

| Inflammatory stromal reaction | 4 |

| Well-differentiated cells | 3 |

| Keratin-filled, deep cleftlike spaces or cysts | 2 |

| Microabscesses | 1 |

All features were manifest in the present case report.

Treatment options for verrucous carcinomas have become clearer. A review by Ferlito and colleagues21 of tumors around the head and neck supported the theory that verrucous carcinomas are less radiosensitive than typical squamous carcinomas; primary radiotherapy achieved local control in 43% of reported cases. In contrast, primary surgery may achieve local control in 81 to 92%.20 Regardless of the initial treatment modality, salvage radiotherapy or surgery still accomplishes local control in at least 84% of cases.20 Recent studies infer that radioresistance may reflect the low rate of proliferation of verrucous carcinoma cells in all but the deepest, advancing margin.22

However, these data largely pertain to oral and laryngeal verrucous carcinomas. For all carcinomas, infiltration into or out of the temporal bone is notoriously difficult to extirpate with adequate margins, not least due to the proximity of the brain and great vessels.3 Regardless of treatment, the 5-year survival rate for those with deep temporal involvement may be as low as 29%.5 Our patient's tumor was extensive with extratemporal involvement of the skull base, infratemporal fossa, and middle and posterior cranial fossae. There was destruction of the inner ear structures, a feature reported exceptionally for squamous cell carcinomas23 and verrucous carcinomas.7,9 The decision to pursue radical resection followed by radiotherapy was based on the clinical picture of a relatively fit individual with a locally aggressive tumor and radiographic evidence of nodal enlargement. With hindsight, it could be argued that regional lymphadenectomy could have been avoided by prior nodal sampling. However, with stereotypical multiple failed attempts at definitive histological diagnosis of the main tumor, the most likely diagnosis was a conventional squamous cell carcinoma.3,5,6 Furthermore, nodal sampling may be nonrepresentative.

A more central question was the choice of surgery as the primary treatment. Conley believes that any treatment is palliative in patients with widespread local invasion at presentation.3 Based on comparisons with previous cases of verrucous carcinoma of the temporal bone, two groups emerge on the basis of site and prognosis (Table 2). Extratemporal spread with or without treatment is associated with a grave prognosis compared with verrucous carcinoma confined to the middle ear or external auditory canal. At least three patients in the extratemporal group who were treated surgically developed early postoperative morbidity such as fistulae. Interestingly, the survival of the one patient with extratemporal spread without major intervention13 was not dramatically worse than that of the treated group. This finding is consistent with the suggested slow propagation of the disease.14,15 Consequently, assuming verrucous carcinoma has already been diagnosed, radiographic information may help make the decision to advance to primary surgery. If there is extratemporal spread with clear involvement of structures likely to result in significant postoperative morbidity if damaged during extirpation (e.g., encasement of cranial nerves), radiographic information might encourage an alternative approach.

Table 2.

Case Reports of Verrucous Carcinoma of the Ear and Temporal Bone

| Case Report | Site | Treatment | Survival Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Woodson et al (1981)7 | Extratemporal | Temporal bone resection, radiotherapy | Not stated |

| Proops et al (1984)9 | Extratemporal | Revision mastoidectomy, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy | At least 18 months |

| Edelstein et al (1986)10; five cases reported | Middle ear, external auditory canal | Mastoidectomy | At least 10 years |

| External auditory canal | Local resection | At least 5 years | |

| External auditory canal | Local resection | At least 4 years | |

| Extratemporal | Mastoidectomy, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy | 1 year | |

| Extratemporal | Mastoidectomy, chemotherapy | 1 year | |

| Diengdoh et al (1990)11 | Extratemporal | Mastoidectomy | 8 months |

| Farrell and Dowe (1995)12 | Extratemporal | Palliative radiotherapy | 8 months |

| Hagiwara et al (2000)13 | Extratemporal | Refused major intervention | 20 months |

The main alternative to surgery would have been primary radiotherapy. Aside from the suggested radioresistance of verrucous carcinoma, the literature traditionally has warned of potential “de-differentation” of the tumor to a more aggressive variant after radiotherapy. This phenomenon is rare and occurs after both surgery and no treatment.20,21 For predominantly typical squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone, radiotherapy has been effective at controlling symptoms and associated with few cases of osteoradionecrosis. However, it has not been advantageous for survival.6 In advanced cases, radiotherapy should be considered as an alternative to surgery based on the patient's likely longevity with either option, general health, and opinion of “acceptable morbidity.”20

CONCLUSIONS

Verrucous carcinomas are squamous neoplasms that rarely occur in the temporal bone. They have similar clinical features and suggested etiology as conventional squamous cell carcinomas of the temporal bone. However, apparently bland cytology and histology frequently delay diagnosis. A full-thickness biopsy is essential. Reactive lymphadenopathy is a common finding. Although relatively radioresistant, radiotherapy may be preferable to surgery for lesions with extratemporal spread due to reduced morbidity and little difference in longevity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Department of Medical Illustration at Frenchay Hospital for their help in preparing the photographs.

REFERENCES

- Batsakis J G, Hybels R, Crissman J D, Rice D H. The pathology of head and neck tumours: verrucous carcinoma, part 15. Head Neck Surg. 1982;5:29–38. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890050107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlito A, Devaney K O, Rinaldo A, Putzi M J. Papillary squamous cell carcinoma versus verrucous squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999;108:318–322. doi: 10.1177/000348949910800318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley J. Cancer of the middle ear. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1965;74:555–572. doi: 10.1177/000348946507400222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker W N. Cancer of the middle ear. Cancer. 1965;18:642–650. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196505)18:5<642::aid-cncr2820180513>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin W J, Jesse R H. Malignant neoplasms of the external auditory canal and temporal bone. Arch Otolaryngol. 1980;106:675–679. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1980.00790350017006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha P P, Aziz H I. Treatment of carcinoma of the middle ear. Radiology. 1978;126:485–487. doi: 10.1148/126.2.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodson G E, Jurco S, Alford B R, McGavaran M H. Verrucous carcinoma of the middle ear. Arch Otolaryngol. 1981;107:63–65. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1981.00790370065015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlito A, Recher G. Ackerman's tumour (verrucous carcinoma) of the larynx: a clinicopathological study of 77 cases. Cancer. 1980;46:1617–1630. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19801001)46:7<1617::aid-cncr2820460722>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proops D W, Hawke W M, Nostrand A WP van, Harwood A R, Lunan M. Verrucous carcinoma of the ear. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1984;93:385–388. doi: 10.1177/000348948409300420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein D R, Smouha E, Sacks S H, Biller H F, Kaneko M, Parisier S C. Verrucous carcinoma of the temporal bone. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1986;95:447–453. doi: 10.1177/000348948609500503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diengdoh J V, Leeming R D, Shaw M DM. Verrucous carcinoma of the base of the skull. Br J Neurosurg. 1990;4:73–76. doi: 10.3109/02688699009000686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell M L, Dowe A C. Verrucous carcinoma of the temporal bone. Aust N Z J Surg. 1995;65:214–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1995.tb00610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara H, Kanazawa T, Ishikawa K, et al. Invasive verrucous carcinoma: a temporal bone histopathology report. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2000;27:179–183. doi: 10.1016/s0385-8146(99)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman L V. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus F T, Perez-Mesa C. Verrucous carinoma: clinical and pathological study of 105 cases involving oral cavity, larynx and genitalia. Cancer. 1966;19:26–38. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196601)19:1<26::aid-cncr2820190103>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandeweyer E F, Sales F, Deraemaecker R. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:168–170. doi: 10.1054/bjps.2000.3440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel J C, Peny M O, Dobbeleer G De, et al. p53 Protein overexpression in verrucous carcinoma of the skin. Dermatology. 1996;192:12–15. doi: 10.1159/000246305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubbe J, Kormann A, Adams V, et al. HPV-11- and HPV-16-associated oral verrucous carcinoma. Dermatology. 1996;192:217–221. doi: 10.1159/000246369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takematsu H, Watanabe M, Matsunaga J, Tagami H. Verrucous carcinoma of the face with a massive neutrophil infiltrate: analysis of leucocyte chemotactic activity in the tumour extract. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:26–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tharp M E, Shidnia H. Radiotherapy in the treatment of verrucous carcinoma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 1995;105(4 Pt 1):391–396. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199504000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlito A, Rinaldo A, Mannara G M. Is primary radiotherapy an appropriate option for the treatment of verrucous carcinoma of the head and neck? J Laryngol Otol. 1998;112:132–139. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100140137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel J C, Heenen M, Peny M O, et al. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen distribution in verrucous carcinoma of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:868–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb06918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraide F, Inouye T, Ishii T. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the middle ear invading the cochlea. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1983;92:290–294. doi: 10.1177/000348948309200315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]