Abstract

1. Dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the ventral mesencephalon play an important role in the regulation of the parallel basal ganglia loops.

2. We have raised affinity-purified polyclonal rabbit antibodies specific for all four members of the Kir3 family of inwardly rectifying potassium channels (Kir3.1–Kir3.4) to investigate the distribution of the channel proteins in the dopaminergic neurons of the rat mesencephalon at light and electron microscopic level. In addition, immunocytochemical double labeling with tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), a marker of dopaminergic neurons, were performed.

3. All Kir3 channels were present in this region. However, the individual proteins showed differential cellular and subcellular distributions.

4. Kir3.1 immunoreactivity was found in SNc fibers and some neurons of the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr). Few Kir3.3-positive neurons were found in the SNc. However, a strong Kir3.3 signal was identified in the SNr neuropil. Weak Kir3.4 staining was detected in neuronal somata as well as in dendritic fibers of both parts of the SN.

5. In the VTA, Kir3.1, Kir3.3, and Kir3.4 showed only weak staining of neuropil structures. The distribution of the Kir3.2 channel protein was especially striking with strong labeling in the SNc and in the lateral but not central VTA.

6. Our results suggest that the heterogeneously distributed Kir3.2 channel proteins could help to discriminate the dopaminergic neurons of VTA and SNc.

Key Words: dopamine, GIRK, VTA, ventral tegmental area, SNc, substantia nigra

INTRODUCTION

The midbrain dopaminergic systems (MDS) including the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) mediate a wide range of behavior. Integrative circuitry between SNc and VTA neurons are a central aspect of psychological regulations of motor function (Haber and Fudge, 1997). Consequently, compromised dopamine function results in motor, psychomotor, and emotional disturbances, emphasizing the presumed integrative role of the MDS. Most prominent, Parkinson's disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder affecting about 1% of the population older than 50 years (Duvoisin, 1999). PD is characterized by motor disability mainly resulting from the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the SNc that project to the striatum (Bosboom et al., 2004). Therefore, neuroprotection of dopaminergic neurons is an important therapeutic approach in PD.

Potassium channels are a major pharmacological target regarding neuroprotection (Wickenden, 2000; Liss and Roeper, 2001; Golanov and Zhou, 2003). Electrophysiological studies have shown that dopaminergic neurons, like many neuronal cells, express a type of inwardly rectifying potassium channels (Liss et al., 1999b) that opens subsequent to the activation of G-protein-coupled receptors such as D2, 5-HT1A, or GABA-B receptors. Increased potassium efflux results in neuronal inhibition and decreased release of neurotransmitters, including dopamine, which is a prominent neurotransmitter in mesostriatal, mesolimbic, and mesocortical pathways (Swanson, 1982). Only a subpopulation of approximately 10% of the dopaminergic neurons additionally contains GABA as identified recently (Gonzalez-Hernandez et al., 2001).

In mammals, G-protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channels are composed of four subunits that are individual members of the Kir3 (formerly GIRK) family and form homomeric or heteromeric complexes (Liao et al., 1996; Wischmeyer et al., 1997). Previous localization studies have shown that all four Kir3 subunits are strongly expressed in brain with partially overlapping distributions. Recent immunocytochemical and in situ hybridization data have shown that Kir3.2 is the predominant Kir3 subunit in the midbrain (Karschin et al., 1996; Chen et al., 1997; Murer et al., 1997; Schein et al., 1998). The expression of Kir3.2 in dopaminergic midbrain neurons was elegantly confirmed by single cell-PCR analysis (Liss et al., 1999b). The importance of the strong expression of Kir3.2 in midbrain neurons is documented by the fact that a point mutation in the pore of the mouse Kir3.2 channel, leading to a loss of ion selectivity, results in the weaver (wv) phenotype. Such mice suffer from aberrant postnatal development and death of several classes of neurons including the dopaminergic neurons of the SNc (Liao et al., 1996; Surmeier et al., 1996). The detailed distribution of all four Kir3 channels in the mesencephalon, however, is still not known. Remaining uncertainties involve the expression of the Kir3.4 subunit in dopaminergic neurons (Iizuka et al., 1997; Murer et al., 1997). Kir3.1 seems to be absent from the SNc (Karschin et al., 1996; Ponce et al., 1996; Chen et al., 1997). Kir3.3 in situ data indicate a robust expression in midbrain neurons, but the distribution (somatodendritic versus axonal) of the protein remains to be clarified. In the present study, we focused on the cellular and subcellular localization of the four members of the Kir3 family in the ventral mesencephalon.

Methods

Animals

All animals were handled in accordance with German animal protection laws and approved by the governmental authorities.

Molecular Biology

PCR-fragments of the less conserved carboxy terminal sequence of Kir3.1–Kir3.4 were amplified using Pfu polymerase (Stratagene) and cloned into the bacterial expression vectors pGEX-4T-1 (Pharmacia, Glutathion-S-Transferase (GST) fusion protein) and pQE-40 (Qiagen, 6His-tagged Dihydrofolat Reductase (6His-DHFR) fusion protein). Kir3.1–Kir3.4 cDNA were kindly provided by Dr. Andreas Karschin (Dissmann et al., 1996; Spauschus et al., 1996).

The following C-terminal Kir3 fragments were used to construct GST fusion proteins: (1) Kir3.1: amino acids 352–501 (rat, GenBank-Acc. No.: U01071); (2) Kir3.2: amino acids 365–423 (human, GenBank-Acc. No.: U24660); (3) Kir3.3: amino acids 329–376 (rat, GenBank-Acc. No.: L77929); and (4) Kir3.4: amino acids 375–419 (human, GenBank-Acc. No.: L47208). Kir3-GST-fusion proteins were overexpressed in the E. coli strain DH5α and purified using Glutathion-Sepharose 4B (Pharmacia Biotech) as described by the manufacturer.

The following C-terminal Kir3 fragments were used to construct a 6His-DHFR fusion protein: (1) Kir3.1: amino acids 347–501; (2) Kir3.2: amino acids 362–423; (3) Kir3.3: amino acids 324–376; and (4) Kir3.4: amino acids 353–419. Kir3–6His-DHFR proteins were overexpressed in the E. coli strain DH5α and purified using Ni2+-NTA agarose (Qiagen) as described by the manufacturer.

Antibody Production and Purification

White 4- to 5-month-old New Zealand rabbits were immunized with the Kir3-GST fusion protein derived from the pGEX expression system following standard protocols (Harlow and Lane, 1988). Two animals were used for each Kir3 subunit protein. After bleeding and decomplementation, 2 mL aliquots of individual immune sera were passed through a Superdex 200 column (Pharmacia) to remove IgMs, and fractions containing IgGs were pooled. Crude IgG-fractions were tested for cross reactivity by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) (Harlow and Lane, 1988). Cross reactivities against the fusion parts of the molecules were removed following recent protocols (Gruber and Zingales, 1995; Pompeia et al., 1996).

For every GST-free Kir3.x, antiserum low level immunoreactivities against the other Kir3 subunits were detected in subsequent ELISA assays. These were removed by adsorption to nitrocellulose strips, which previously had been loaded with the cross-reactive pQE-Kir3 fusion proteins, resulting in monospecific antisera. These antisera were finally purified by affinity chromatography using nitrocellulose membranes bearing the cognate recombinant 6His-DHFR-Kir3.x protein as a specific antigen. After elution, purified antibodies were concentrated by ion exchange chromatography on SP-Sepharose (Pharmacia) and stored in aliquots at −80°C until further use.

Western Blotting

Specificity of Kir3 antibodies was first analyzed by Western Blot analysis of recombinant proteins and brain homogenates. Pieces of carefully dissected rat brains (1 g tissue) were homogenized in 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM imidazol, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM NaN3, 1 mM PMSF containing 1 μg/mL of Aprotinin, Pepstatin A, and Leupeptin each, using a Dounce homogenizer for 5 min at 900 rpm. A total of 1 μg recombinant or 10 μg homogenate protein per lane was electrophoretically separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE and subsequently transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. For Western analysis membranes were blocked with 5% low-fat milk powder in PBS containing 1% Tween-20 for 1 h and then incubated overnight with the affinity-purified Kir3.1 (1:500), Kir3.2 (1:100), Kir3.3 (1:500), and Kir3.4 (1:100) antibodies. After incubation with the secondary antibody (alkaline-phosphatase-conjugated antirabbit IgG, 4 h at room temperature), immunolabeled bands were detected using p-nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (NBT) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate (BCIP) as the signal system.

Preparation of Rat Brains for Light and Electron Microscopy

Adult (300–400 g) Wistar rats (Charles River) were deeply anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine, xylazin, and heparin and fixed by transcardial perfusion with PGPic (4% paraformaldehyde, 0.05% glutaraldehyde, and 0.2% picric acid) in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Brains were carefully adjusted with respect to their longitudinal and binaural axis in a corresponding frame (Andres and von Düring, 1981), temporarily embedded in 2% agarose to maintain orientation, and cut at selected rostrocaudal levels into coronal blocks of 3–8 mm thickness. The blocks were freed from agarose, cryoprotected by immersion in 0.4 M (4 h) and 0.8 M (overnight) sucrose in PBS, shock-frozen in liquid pentane at −65°C, and stored at −80°C until use.

Single Labeling Light Microscopy

Freely floating 20 μm coronal cryostat sections through the rat mesencephalon were pretreated with 1% sodium borohydride in PBS for 15 min to remove excessive aldehydes. After preincubation in 0.3% Triton X-100 and 0.05% phenylhydrazine in 10% normal goat serum (NGS) for 30 min at room temperature to permeabilize cell membranes and simultaneously to block unspecific binding sites and endogenous peroxidase activity, sections were treated with affinity-purified primary antibodies (appropriately diluted in 0.3% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium azide, and 0.01% thimerosal in 10% NGS) for 36 h in a cold room, and biotinylated goat antirabbit IgG secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, 1:2000 in 0.2% bovine serum albumin in PBS) for 20 h at room temperature. Bound antibodies were detected by the Vectastain Elite ABC kit (Vector Laboratories; 6 h at room temperature) and visualized using a substrate solution of 1.4 mM 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB), 10 mM imidazole, and 0.3% ammonium nickel sulfate in 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.6), which was supplemented with 0.015% H2O2 (final concentration) to start the reaction. After 6 min, the reaction was stopped by replacing the incubation mixture with PBS. Sections were mounted on gelatin-coated slides, dehydrated, and coverslipped in entellan.

Blocking of Antibodies

In control experiments, appropriately diluted primary antibodies were blocked by preincubation with their cognate antigens (10 μg/mL for 2 h at RT) before being applied to sections.

Double Labeling Immunofluorescence Microscopy

For double labeling experiments, sections were treated correspondingly. The monoclonal mouse antityrosine hydroxylase (TH) antibody was detected with Cy3-labeled donkey antimouse IgG, and rabbit anti-Kir3 antibodies were visualized by Cy2-conjugated donkey antirabbit IgGs (both Jackson). Sections were finally washed with PBS, mounted on uncoated glass slides, and coverslipped in moviol.

Immunogold Preembedding Double Labeling for Electron Microscopy

For electron microscopy, immunocytochemical treatment with a compromised permeabilization of the sections was used to prevent complete loss of membranes. Thus, freely floating 40 μm coronal vibratome sections through the rat mesencephalon were largely treated as earlier except that Triton X-100 was added at low concentration (0.1%) to the preincubation step only and omitted in further antibody solutions.

Sections were treated simultaneously with rabbit anti-Kir3.x (dilutions, see section “Western blotting”) and mouse antityrosine hydroxylase (1:1000 in 10% NGS), followed by combined secondary antibodies (0.8 nm gold antirabbit IgG, 1:50 (Aurion) and biotinylated horse antimouse IgG, 1:1000 (Vector)). After postfixation (2% glutaraldehyde, 15 min) the gold particles were enlarged by silver enhancement (IntenSE kit, Amersham), and anti-TH antibodies were detected by the Vectastain Elite ABC kit as earlier, but omitting nickel ions. Sections were postfixed in 1% OsO4 for 30 min, dehydrated, and flat embedded in Araldite.

Ultrathin sections were cut with an ultramicrotome (Ultracut S, Reichert-Jung, Germany), mounted on uncoated 200-mesh nickel grids, counterstained with uranyl acetate and Reynold's lead citrate, and then examined with an electron microscope (EM 900, Zeiss).

Results

Characterization of Anti-Kir3 Antibodies

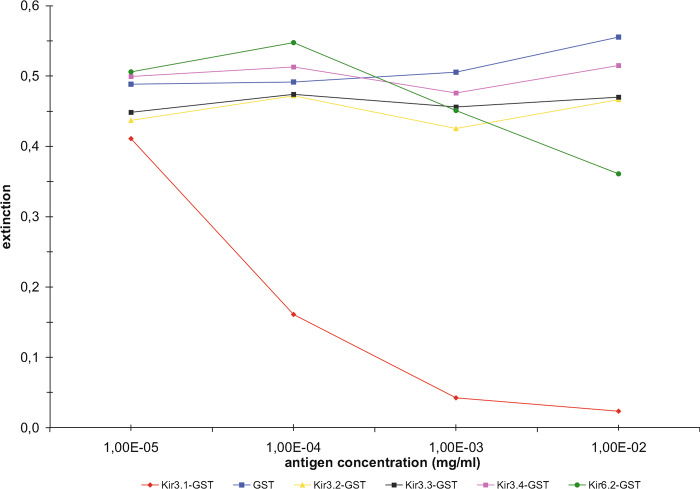

In order to produce specific antibodies against individual members of the Kir3 family, unique amino acid sequences are needed. Strong homology between the members of the Kir3 subfamily exists in the transmembrane domains, the pore regions, and the flanking cytoplasmic amino acids. Consequently, the less conserved carboxyterminal sequences (50–150 amino acids) were selected for raising polyclonal rabbit antibodies. Monospecific and affinity purified anti-Kir3 antibodies were obtained, lacking cross-reactivities to other subfamily members or to members of other related Kir-families as verified by competitive ELISA assays (as exemplified for anti-Kir3.1 in Fig. 1, for details see Methods).

Fig. 1.

Competitive ELISA assay of anti-Kir3 antibodies as exemplified by anti-Kir3.1 antibodies. Microtiter plates were coated with the respective GST-Kir3.x or GST-Kir6.2 fusion protein. Only preincubation of the antibodies with the cognate GST-Kir3 fusion protein decreased immunoreactivity in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas other GST-Kir fusion proteins had no effect.

Antibody quality was evaluated at several further levels. Specificities for their cognate primary sequences were tested by Western Blot analysis of the recombinant proteins. Reactivities of all anti-Kir3.x antibodies were restricted to their cognate proteins and blocked by preincubation with the antigen (not shown). This test, however, does not exclude cross-reactivities to other possibly unknown brain proteins.

Such possibilities were ruled out by Western Blot analysis of rat brain homogenates (Fig. 2). With the exception of Kir3.1, single bands were obtained with the expected molecular weights. The anti-Kir3.1 antibody detects three distinct bands that are completely abolished by preincubation with the cognate recombinant protein (Fig. 2(A)). The three bands may be due to the presence of several splice variants or differential posttranslational modifications of the Kir3.1 protein in the brain (Nelson et al., 1997).

Fig. 2.

Western Blot analysis of anti-Kir3 antibodies. Rat brain homogenates (10 μg/lane) were separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. (A) Anti-Kir3.1 antibodies recognize three distinct bands of ∼50, ∼53, and ∼60 kD, all other anti-Kir3 antibodies recognize single bands of 48 kD (B, Kir3.2), 44 kD (C, Kir3.3), and 53 kD (D, Kir3.4). Preincubation with the cognate recombinant GST-Kir3 fusion proteins completely abolished detection by anti-Kir3 antibodies (right lanes).

Splice variants (Kir3.2a–Kir3.2d) are also known for the Kir3.2 gene (Inanobe et al., 1999b), although Kir3.2d has been only detected in mouse testis so far (Inanobe et al., 1999a). The three other splice variants differ only in their carboxyterminal lengths. Kir3.2a and Kir3.2c differ in 11 amino acid residues in the proximal tail and may be detected simultaneously, as suggested by the broad single band in the Western Blot (Fig. 2(B)). The short splice variant Kir3.2b lacks the carboxyterminal amino acid sequence used for immunization and therefore will not be detected by our antibody.

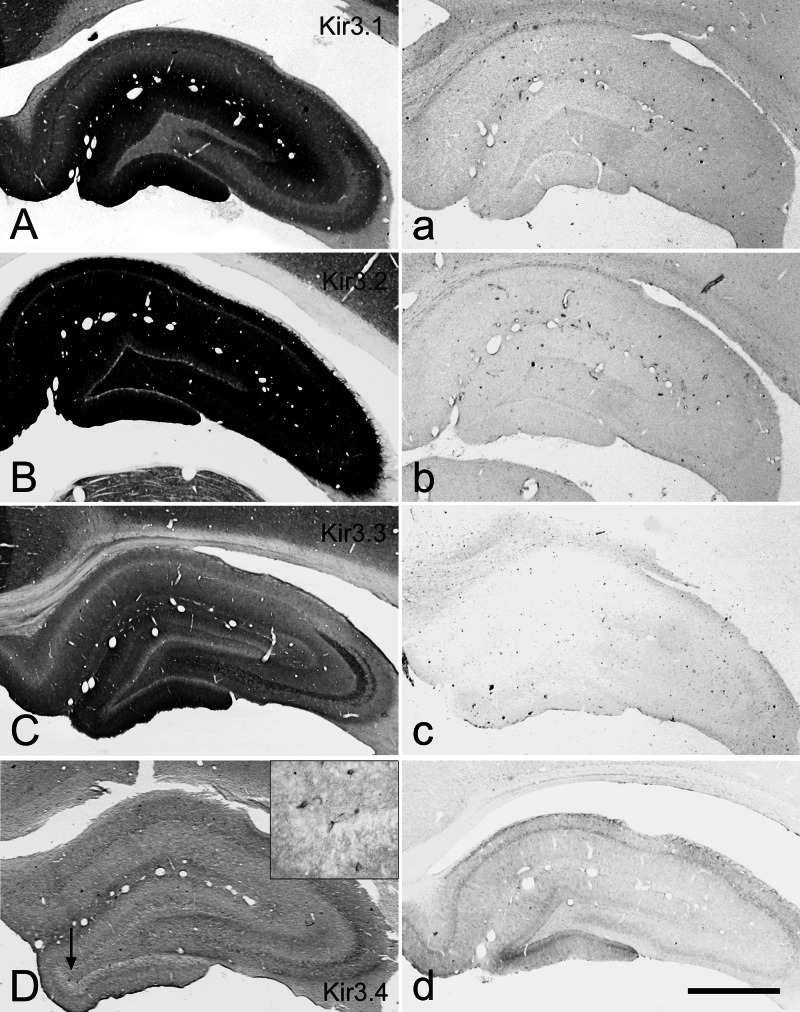

Immunocytochemical specificities of our antibodies were demonstrated using the hippocampus as model (Fig. 3(A–D)). Each antibody showed a characteristic and individual localization pattern. Note that the Kir3.2 protein was distributed over all areas of the hippocampus (not overstained in Fig. 3(B)), as staining was abolished subsequent to preincubation with the cognate recombinant protein (Fig. 3(A–D)). The present localizations of the Kir channel proteins in the hippocampus were in good agreement with earlier in situ hybridization (Karschin et al., 1996; Ponce et al., 1996; Drake et al., 1997; Iizuka et al., 1997; Wickman et al., 2000) and immunocytochemical data (Liao et al., 1996; Miyashita and Kubo, 1997; Murer et al., 1997).

Fig. 3.

Adjacent coronal sections of rat hippocampus were incubated with anti-Kir3 antibodies (left column, A–D) or with anti-Kir3 antibodies preincubated with their cognate GST-Kir3 fusion proteins (10 μg/mL, right column, a–d). Specific immunolabeling was totally repressed after preincubation. Inset in (D) shows cellular distribution of Kir3.4 channels at higher magnification in the area indicated with an arrow. Bar represents 1 mm.

Kir3 Subunits Are Differentially Distributed in the Rat Ventral Mesencephalon

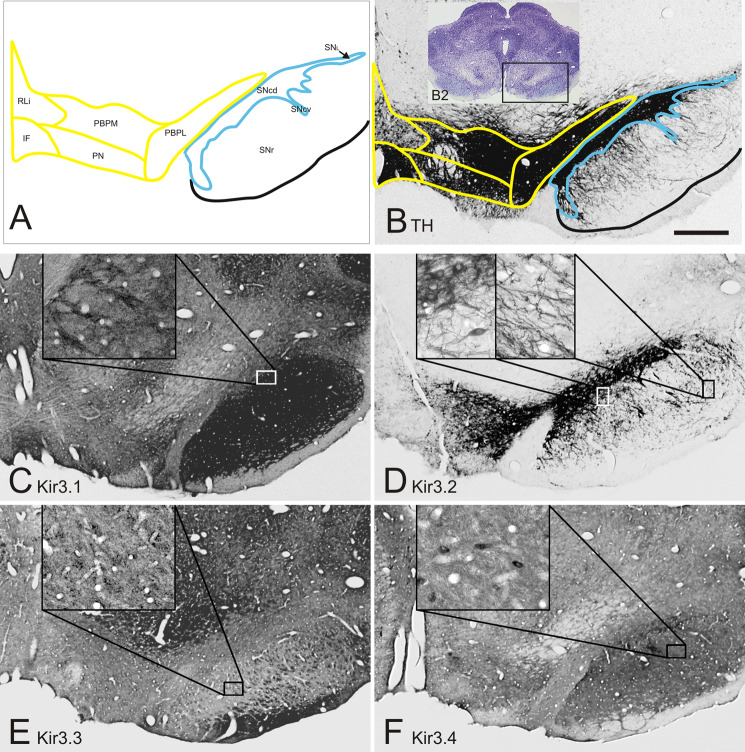

Dopaminergic neurons are heterogeneously distributed in the ventral mesencephalon and here are visualized using antityrosine hydroxylase antibodies (Fig. 4(A)). This enzyme catalyzes the formation of di-orthohydroxy-phenylalanine (DOPA) from tyrosine as the first step in the biosynthesis of catecholamines. Bearing in mind that it is also present in noradrenergic and adrenergic neurons, it is generally used as a marker for dopaminergic neurons and their axons and terminals.

Fig. 4.

Kir3 channels are differentially expressed in the ventral mesencephalon. Several subnuclei can be distinguished in SN and VTA; RLi, rostral linear raphe; IF, interfascicular nucleus; PBPM, parabrachial pigmented nucleus, medial part; PN, paranigral nucleus; PBPL, parabrachial pigmented nucleus, lateral part; SNr, substantia nigra pars reticulata; SNcd, substantia nigra pars compacta dorsal; SNcv, substantia nigra pars compacta, ventral part; SNcl, substantia nigra pars compacta, lateral part (A). Dopaminergic neurons are heterogeneously distributed in SN and VTA subnuclei (B). The Kir3.2 channel displays the most heterogeneous distribution pattern resembling the tyrosine hydroxylase staining with high expression in the SNc and the lateral VTA subnuclei and only weak immunostaining in the PN and RLi subnuclei of the VTA (D). The Kir3.1, Kir3.3, and Kir3.4 channels display a homogeneous distribution in both VTA and SN with predominant staining of the neuropil (C, E, F). Bar represents 500 μm, insets show 6-fold higher magnifications.

The dopaminergic system in the mesencephalon consists of the substantia nigra pars compacta, the ventral tegmental area, and the retrorubral region. Several subfields are recognized in the SNc and VTA (Fig. 4(A)). Thus, within the SNc, dorsal (SNcd), ventral (SNcv), lateral (SNcl), and medial (SNcm) subareas are distinguished, while the VTA consists of the rostral linear raphe (RLi), the interfascicular (IF), the paranigral (PN), and the medial (PBPM) and lateral (PBPL) aspects of the parabrachial pigmented nucleus (McRitchie et al., 1996). There is no strong morphologically defined border between the SNcd and the PBPL, which is often referred to as the dorsal tier of the SNc. Based on hodological criteria, however, it is part of the VTA and treated as such in the present report.

Our new, monospecific and affinity-purified antibodies allowed the detailed analysis of Kir3 protein distribution in all subnuclei of the ventral mesencephalic areas. Survey micrographs (Fig. 4(C–F)) suggest that the four members of the Kir3 family are abundantly expressed in the ventral mesencephalon. Nevertheless, staining intensities vary among the Kir3 subunits.

The localization of the Kir3.2 protein (Fig. 4(D)) closely resembles that of the dopaminergic cells as visualized with tyrosine hydroxylase immunocytochemistry (Fig. 4(B)). The only and remarkable exception is the IF in the medial VTA (Fig. 4(A); see also text that follows), which is largely devoid of Kir3.2 staining. Neurons of PBPM, PBPL, SNcd, and SNcv display the highest Kir3.2 signal, whereas immunoreactivity is weak in neuronal somata in PN and RLi and even absent in the IF and the SNr. Nevertheless, some fibers (most likely dendrites of SNc neurons) in the SNr display a specific Kir3.2 signal (Fig. 4(D), right inset).

Kir3.1, Kir3.3, and Kir3.4 channels are more homogeneously distributed but differences are obvious. Thus, Kir3.1 immunoreactivity is strong all about the SNr and SNc but much reduced in the VTA (Fig. 4(C)). The distribution of the Kir3.4 appears similar, but weaker (Fig. 4(F)). In contrast, Kir3.3 protein may show an axonal localization as it represents the only subunit with a positive signal in the cerebral peduncles (Fig. 4(E)).

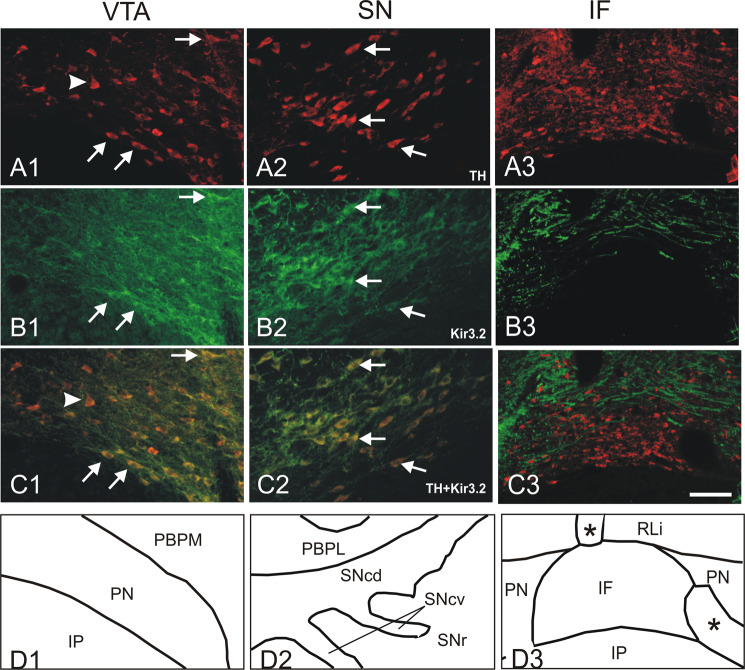

Kir3.2 Channels Are Localized in Dopaminergic Neurons

The similar distribution pattern of Kir3.2 channel protein and tyrosine hydroxylase (Fig. 4(A), (D)) suggests a coexpression at least in some subnuclei of the VTA. Double labeling experiments (Fig. 5) confirm the localization of Kir3.2 protein in dopaminergic neurons. Under red fluorescence, the micrographs display a high number of tyrosine hydroxylase-positive neurons in PN and PBPM subnuclei of the VTA (Fig. 5(A1)) as well as in the SN (A2) and IF subnucleus (A3). Green Kir3.2 immunoreactivity presents a similar distribution in both parts of the SN (B2, arrows indicate the same cells), but a heterogeneous labeling in some VTA subnuclei (B1). Expression of Kir3.2 in dopaminergic neurons is verified by the yellow color in the overlay image (C1, C2, C3). Almost all tyrosine hydroxylase-positive neurons in the SNc express the Kir3.2 protein. In the VTA, however, the Kir3.2 channel is expressed by all dopaminergic neurons only in RLi, CLi, PaP, and PBPL. In contrast, the PN and PBPM subnuclei contain dopaminergic cells that do not express Kir3.2 protein (A1, C1, arrowhead) and the IF subnucleus is even devoid of Kir3.2 despite many tyrosine hydroxylase-positive neurons as confirmed using fluorescence double labeling (B3). The latter finding is in good conformity with previous studies where the Kir3.2 protein was reported to be absent in the interfascicular nucleus in the mouse brain (Schein et al., 1998). Differential coexpression of Kir3.2 and TH was also shown in the VTA of mouse (Thompson et al., 2005) and humans (Mendez et al., 2005).

Fig. 5.

Kir3.2 channels are detected in dopaminergic neurons using fluorescence double labeling. Tyrosine hydroxylase-positive dopaminergic neurons are widely distributed in PN and PBPM subnuclei of the VTA (A1), substantia nigra (A2), and IF subnucleus (A3). Kir3.2 channels are similarly stained in the SN (B2) and some VTA subnuclei (B1) and thus show an extensive coexpression in the overlay image (C1, C2, indicated by arrows). However, some tyrosine hydroxylase-positive neurons of the PN and PBPM subnuclei of the VTA do not express the Kir3.2 channel (arrowhead in C1) and the IF subnucleus is even devoid of Kir3.2 despite many dopaminergic neurons (B3). Subnuclei are indicated in D1, D2 and D3. Bar represents 100 μm; * indicate blood vessels.

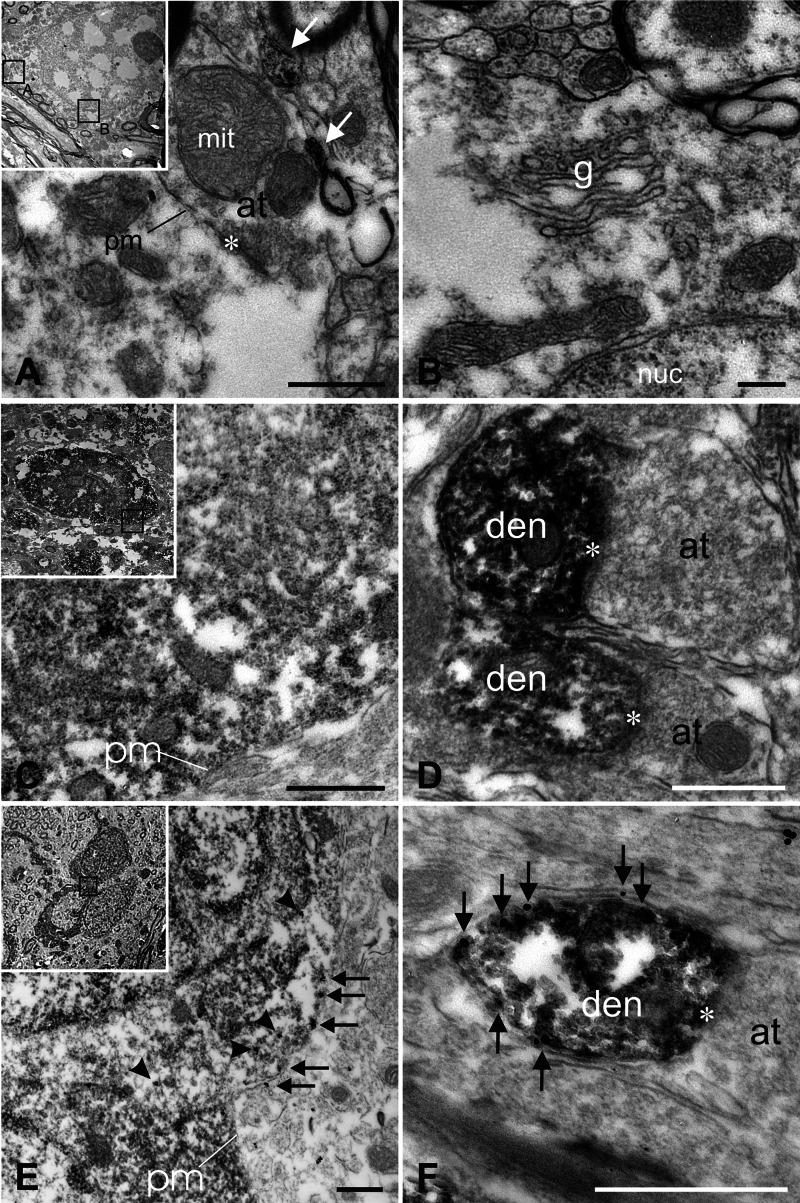

The expression of Kir3.2 in dopaminergic neurons of the ventral mesencephalon was confirmed at the electron microscopic level, focusing on subcellular channel distribution. In a first step, Kir3.2 channels were visualized via peroxidase and diaminobenzidine (Fig. 6). The neurons of the nucleus interfascicularis in the medial VTA were devoid of Kir3.2 immunoreactivity (Fig. 6(A), (B)). Nevertheless, some dendrites in the IF display Kir3.2-positive signal, although the cell bodies are not localized in this subnucleus. In a second step, double labeling experiments at the electron microscopic level show that the IF neurons lacking Kir3.2 immunoreactivity are dopaminergic (Fig. 6(C), (D)). For this purpose, dopaminergic neurons were labeled with antityrosine hydroxylase antibodies and visualized via DAB. DAB-positive dopaminergic cells are recognized by the dark cytoplasmic deposits. Anti-Kir3.2 antibodies were detected using gold-labeled secondary antibodies. Outside the medial VTA, the Kir3.2 protein is present at the plasma membrane of dopaminergic dendrites (Fig. 6(F)) and in somata of dopaminergic neurons (Fig. 6(E)). Except the IF subnucleus all subnuclei of VTA and SN display expression of the Kir3.2 channel protein in dopaminergic neurons in a homogeneous pattern.

Fig. 6.

Subcellular expression of the Kir3.2 channel subunit. The plasma membrane (A, pm) as well as the golgi apparatus (B, g) of neurons in the IF subnucleus of the VTA lack Kir3.2 immunoreactivity, thus confirming the light microscopic data. Some diaminobenzidine deposits are seen in dendrites of neurons that originate outside the IF subnucleus (arrows in A). Double labeling experiments confirm that dopaminergic IF neurons do not express the Kir3.2 channel protein (C, D). No gold-label was detected on DAB-positive cells (C) or dendrites (D). In the PN subnucleus, however, Kir3.2 channels are extensively expressed in the cytoplasm (E, arrowheads) and plasma membrane (arrows in E, F) of dopaminergic neuronal somata and dendrites. All bars represent 500 nm; pm: plasma membrane; at: axon terminal;nuc: nucleus; den: dendrite; g: golgi apparatus; mit: mitochondria; *: synapse.

Discussion

Kir3 Channels in SNc and VTA Dopaminergic Neurons

Several subnuclei of midbrain neurons differentially contribute to physiological and pathophysiological processes. We focused on Kir3 channel distribution in nuclei of ventral tegmental area and substantia nigra. The localization of the Kir3.2 protein resembles that of dopaminergic cells with the exception of the interfascicular nucleus, thus showing highest expression in neurons of PBPM, PBPL, SNcd, and SNcv. The strong Kir3.2 staining in these midbrain structures is in good agreement with recent in situ hybridization studies with particularly high labeling in SNc, VTA (Karschin et al., 1996), and immunocytochemical data (Murer et al., 1997; Schein et al., 1998; Harashima et al., 2006). However, there are some areas for which no mRNA expression has been described, but staining seems to be present, for example, Kir3.2 immunoreactivity in some fibers of the SNr. The discrepancy between mRNA and protein data may reflect the existence of neurons possessing low levels of mRNA below the in situ hybridization sensitivity, but expressing relatively high Kir3.2 levels due to slow protein turnover. However, the Kir3.2 protein may be sorted to the distal axonal or dendritic compartment while the parent cell bodies synthesizing mRNA are located outside the particular nucleus. Kir3.1 immunoreactivity is highest in the SNr and SNc but greatly reduced in the VTA. This is again in considerable difference with previous studies where no Kir3.1 cDNA (Karschin et al., 1996) or conflicting data on protein/cDNA signals (Iizuka et al., 1997) were

reported for the substantia nigra. The Kir3.4 distribution resembles the Kir3.1 pattern, but displays weaker immunosignal, thus supporting earlier in situ (Karschin et al., 1996) and antibody studies (Murer et al., 1997). The Kir3.3 protein shows axonal localization in the cerebral peduncles, but almost avoids the VTA and SN neurons. This finding again is in general agreement with recent in situ hybridization studies that report significantly lower Kir3.3 mRNA levels compared with Kir3.2 (Karschin et al., 1996).

Interestingly, the dopaminergic neurons of the interfascicular nucleus of VTA lack Kir3.2 expression, although most dopaminergic neurons of other VTA subnuclei and SNc display Kir3.2 immunoreactivity. Several VTA subnuclei are highly interconnected with dorsal raphe nuclei, amygdala, lateral septal area, prefrontal cortex, and nucleus accumbens, but it remains unclear yet whether the IF participates in neuronal circuits excluding other VTA nuclei due to differential potassium channel content. Thus, it is of further interest to investigate the detailed ion channel pattern of all VTA and SN subnuclei as well as discrepancies in afferents and efferents of these nuclei.

Other Kir Channels in SNc and VTA Dopaminergic Neurons

The distribution of other potassium channel families in midbrain neurons should also be considered. All four subunits of the strongly inwardly rectifying Kir2 channels are expressed by substantia nigra cells in a differential pattern (Prüss et al., 2005). The Kir2.1 and Kir2.4 subunits are detected only in the SNc, whereas the Kir2.2 and Kir2.3 proteins are expressed in both parts of SN with markedly elevated levels in the neuropil of SNr. The VTA expresses only the Kir2.1 channel protein (Prüss et al., 2005).

The Kir6 family displays ATP-dependent activity, thus coupling energy metabolism to cellular excitability. The open probability of Kir6 channels is increased with decreasing energy levels resulting in hyperpolarization of neurons and reduction of electrical activity. The SNr seems to be a seizure gate by controlling the seizure threshold in the brain with dynamic control of the number of active neuronal KATP channels (Liss and Roeper, 2001; Yamada et al., 2001).

The relevance of overlapping and coactivated potassium channels is elegantly demonstrated in the weaver mouse that possesses a missense mutation in the Kir3.2 channel gene. The phenotype of dopaminergic SN neurons is mediated by coactivation of Kir3.2 and Kir6.2-containing ATP channels (Liss et al., 1999a,b).

Kir3 Channels as Potential Therapeutic Targets

Potassium channels are important candidates for pharmacological interventions (Wickenden, 2002). Good examples for this strategy are the well-known sulfonylurea therapy in diabetic patients and diazoxide treatment in hypertension, both targeting ATP-dependent potassium channels (Sturgess et al., 1985; Standen et al., 1989). Other well established and clinically relevant drugs are activators of KCNQ-type channels such as the anticonvulsant agent retigabine (Wickenden et al., 2000) and openers of the BK-type Ca2+-activated channels, such as BMS-204352, showing neuroprotective properties during ischemia (Cheney et al., 2001). Beside the benefits described by potassium channel openers, several blockers of potassium channels, such as the nonspecific voltage-gated potassium channel blocker 4-aminopyridine, might be of valuable use when increased excitability is desired (Shi and Blight, 1997). Several findings also support the possible role of G protein-dependent Kir3 channels as targets for future drugs. For example, various antidepressant drugs inhibit Kir3 channels in the Xenopus oocyte expression system and may contribute to the therapeutic or adverse side effects observed (Kobayashi et al., 2004). Moreover, Kir3.2 and Kir3.3 knockout mice show decreased cocaine self-administration (Morgan et al., 2003). Kir3 channels are under the control of a variety of signalling molecules that regulate channel sorting, assembly, and activity. Activity further depends on combination of channel subunits among various cell types. Kir3 channels play an important role in the inhibitory regulation of neuronal excitability in most brain regions. Each Kir3 channel possesses one G protein binding site and thus Gβγ binding increases the number of functional Kir3 channels. Considering the Kir3 channel distribution, therapeutically targeting Kir3 channels alone should barely improve clinical disturbances. However, impressive therapeutic results and avoidance of side effects can be obtained only if K+ channels are expressed at high concentrations on functionally important neuron groups. As proposed earlier (Prüss et al., 2003; Thomzig et al., 2005), several classes of channels, transporters and receptors could be targeted at subthreshold doses to converge in relevant neuronal populations with extensive subcellular coexpression.

Regarding the earlier-mentioned example of Kir3.2 and Kir6.2, hypothetically targeting both channels simultaneously might highly affect the common subsystem of mesostriatal neurons but might not involve other brain regions with Kir3.2 channel expression. Considering the subpopulation-selective degeneration within the SN in Parkinson's disease resembling the weaver animal model (Adelbrecht et al., 1997; Hirsch et al., 1997), targeting several potassium channel classes including Kir3 might also influence neurodegenerative conditions.

CONCLUSION

The detailed localization study of potassium channel subunits on important neuronal structures could identify potential target cells for pharmacotherapy. In this sense, the present work describes the differential distribution of Kir3 channels in the rat mesencephalon. Our results suggest that the heterogeneously distributed Kir3.2 channel proteins could help to discriminate the dopaminergic neurons of VTA and SNc. Ongoing research aims to add more potassium channel candidates by analyzing comprehensive localization patterns of all known potassium channels in the dopaminergic cells of the mesencephalon.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are indebted to Prof. Andreas Karschin for providing Kir3.1–3.4 cDNAs. The excellent technical assistance of Dr. Mareike Wenzel and Petra Loge is gratefully acknowledged. In addition, we would like to thank Annett Kaphahn for editorial help.

References

- Adelbrecht, C., Murer, M. G., Lauritzen, I., Lesage, F., Ladzunski, M., Agid, Y., and Raisman-Vozari, R. (1997). An immunocytochemical study of a G-protein-gated inward rectifier K+ channel (GIRK2) in the weaver mouse mesencephalon. Neuroreport8:969–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres, K. H., and von Düring, M. (1981). General methods for characterization of brain regions. In Heym, C. H., and Forssmann, W. G. (eds.), Techniques in Neuroanatomical Research, Springer, Heidelberg Berlin New York, pp. 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Bosboom, J. L., Stoffers, D., and Wolters, E. C. (2004). Cognitive dysfunction and dementia in Parkinson's disease. J. Neural. Transm.111:1303–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S. C., Ehrhard, P., Goldowitz, D., and Smeyne, R. J. (1997). Developmental expression of the GIRK family of inward rectifying potassium channels: Implications for abnormalities in the weaver mutant mouse. Brain Res.778:251–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheney, J. A., Weisser, J. D., Bareyre, F. M., Laurer, H. L., Saatman, K. E., Raghupathi, R., Gribkoff, V., Starrett, J. E.,Jr., and McIntosh, T. K. (2001). The maxi-K channel opener BMS-204352 attenuates regional cerebral edema and neurologic motor impairment after experimental brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab.21:396–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dissmann, E., Wischmeyer, E., Spauschus, A., von Pfeil, D., Karschin, C., and Karschin, A. (1996). Functional expression and cellular mRNA localization of a G protein-activated K+ inward rectifier isolated from rat brain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.223:474–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake, C. T., Bausch, S. B., Milner, T. A., and Chavkin, C. (1997). GIRK1 immunoreactivity is present predominantly in dendrites, dendritic spines, and somata in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.94:1007–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvoisin, R. C. (1999). Genetic and environmental factors in Parkinson's disease. Adv. Neurol.80:161–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golanov, E. V., and Zhou, P. (2003). Neurogenic neuroprotection. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol.23:651–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Hernandez, T., Barroso-Chinea, P., Acevedo, A., Salido, E., and Rodriguez, M. (2001). Colocalization of tyrosine hydroxylase and GAD65 mRNA in mesostriatal neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci.13:57–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, A., and Zingales, B. (1995). Alternative method to remove antibacterial antibodies from antisera used for screening of expression libraries. Biotechniques19:28–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber, S. N., and Fudge, J. L. (1997). The primate substantia nigra and VTA: Integrative circuitry and function. Crit. Rev. Neurobiol.11:323–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harashima, C., Jacobowitz, D. M., Witta, J., Borke, R. C., Best, T. K., Siarey, R. J., and Galdzicki, Z. (2006). Abnormal expression of the G-protein-activated inwardly rectifying potassium channel 2 (GIRK2) in hippocampus, frontal cortex, and substantia nigra of Ts65Dn mouse: A model of Down syndrome. J. Comp. Neurol.494:815–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow, E., and Lane, D. (eds.) (1988). Antibodies: A Laboratory Manual, CSH Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Hirsch, E. C., Faucheux, B., Damier, P., Mouatt-Prigent, A., and Agid, Y. (1997). Neuronal vulnerability in Parkinson's disease. J. Neural. Transm. Suppl.50:79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka, M., Tsunenari, I., Momota, Y., Akiba, I., and Kono, T. (1997). Localization of a G-protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+ channel, CIR, in the rat brain. Neuroscience77:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inanobe, A., Horio, Y., Fujita, A., Tanemoto, M., Hibino, H., Inageda, K., and Kurachi, Y. (1999a). Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel splicing variant of the Kir3.2 subunit predominantly expressed in mouse testis. J. Physiol.521:19–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inanobe, A., Yoshimoto, Y., Horio, Y., Morishige, K. I., Hibino, H., Matsumoto, S., Tokunaga, Y., Maeda, T., Hata, Y., Takai, Y., and Kurachi, Y. (1999b). Characterization of G-protein-gated K+ channels composed of Kir3.2 subunits in dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra. J. Neurosci.19:1006–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karschin, C., Dissmann, E., Stuhmer, W., and Karschin, A. (1996). IRK(1–3) and GIRK(1–4) inwardly rectifying K+ channel mRNAs are differentially expressed in the adult rat brain. J. Neurosci.16:3559–3570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, T., Washiyama, K., and Ikeda, K. (2004). Inhibition of G protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channels by various antidepressant drugs. Neuropsychopharmacology29:1841–1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y. J., Jan, Y. N., and Jan, L. Y. (1996). Heteromultimerization of G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channel proteins GIRK1 and GIRK2 and their altered expression in weaver brain. J. Neurosci.16:7137–7150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liss, B., Neu, A., and Roeper, J. (1999b). The weaver mouse gain-of-function phenotype of dopaminergic midbrain neurons is determined by coactivation of wvGirk2 and K-ATP channels. J. Neurosci.19:8839–8848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liss, B., Bruns, R., and Roeper, J. (1999a). Alternative sulfonylurea receptor expression defines metabolic sensitivity of K-ATP channels in dopaminergic midbrain neurons. EMBO J.18:833–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liss, B., and Roeper, J. (2001). Molecular physiology of neuronal K-ATP channels. Mol. Membr. Biol. 18:117–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRitchie, D. A., Hardman, C. D., and Halliday, G. M. (1996). Cytoarchitectural distribution of calcium binding proteins in midbrain dopaminergic regions of rats and humans. J. Comp. Neurol.364:121–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez, I., Sanchez-Pernaute, R., Cooper, O., Vinuela, A., Ferrari, D., Bjorklund, L., Dagher, A., and Isacson, O. (2005). Cell type analysis of functional fetal dopamine cell suspension transplants in the striatum and substantia nigra of patients with Parkinson's disease. Brain128:1498–1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita, T., and Kubo, Y. (1997). Localization and developmental changes of the expression of two inward rectifying K(+)-channel proteins in the rat brain. Brain Res.750:251–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, A. D., Carroll, M. E., Loth, A. K., Stoffel, M., and Wickman, K. (2003). Decreased cocaine self-administration in Kir3 potassium channel subunit knockout mice. Neuropsychopharmacology28:932–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murer, G., Adelbrecht, C., Lauritzen, I., Lesage, F., Lazdunski, M., Agid, Y., and Raisman-Vozari, R. (1997). An immunocytochemical study on the distribution of two G-protein-gated inward rectifier potassium channels (GIRK2 and GIRK4) in the adult rat brain. Neuroscience80:345–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, C. S., Marinoand, J. L., and Allen, C. N. (1997). Cloning and characterization of Kir3.1 (GIRK1) C-terminal alternative splice variants. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res.46:185–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompeia, C., Ortis, F., and Armelin, M. C. (1996). Immunopurification of polyclonal antibodies to recombinant proteins of the same gene family. Biotechniques21:986–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponce, A., Bueno, E., Kentros, C., Vega-Saenz de Miera, E., Chow, A., Hillman, D., Chen, S., Zhu, L., Wu, M. B., Wu, X., Rudy, B., and Thornhill, W. B. (1996). G-protein-gated inward rectifier K+ channel proteins (GIRK1) are present in the soma and dendrites as well as in nerve terminals of specific neurons in the brain. J. Neurosci.16:1990–2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prüss, H., Derst, C., Lommel, R., and Veh, R. W. (2005). Differential distribution of individual subunits of strongly inwardly rectifying potassium channels (Kir2 family) in rat brain. Mol. Brain Res.139:63–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prüss, H., Wenzel, M., Eulitz, D., Thomzig, A., Karschin, A., and Veh, R. W. (2003). Kir2 potassium channels in rat striatum are strategically localized to control basal ganglia function. Mol. Brain Res.110:203–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schein, J. C., Hunter, D. D., and Roffler-Tarlov, S. (1998). Girk2 expression in the ventral midbrain, cerebellum, and olfactory bulb and its relationship to the murine mutation weaver. Dev. Biol.204:432–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, R., and Blight, A. R. (1997). Differential effects of low and high concentrations of 4-aminopyridine on axonal conduction in normal and injured spinal cord. Neuroscience77:553–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spauschus, A., Lentes, K. U., Wischmeyer, E., Dissmann, E., Karschin, C., and Karschin, A. (1996). A G-protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channel (GIRK4) from human hippocampus associates with other GIRK channels. J. Neurosci.16:930–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standen, N. B., Quayle, J. M., Davies, N. W., Brayden, J. E., Huang, Y., and Nelson, M. T. (1989). Hyperpolarizing vasodilators activate ATP-sensitive K+ channels in arterial smooth muscle. Science245:177–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturgess, N. C., Ashford, M. L., Cook, D. L., and Hales, C. N. (1985). The sulphonylurea receptor may be an ATP-sensitive potassium channel. Lancet2:474–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surmeier, D. J., Mermelstein, P. G., and Goldowitz, D. (1996). The weaver mutation of GIRK2 results in a loss of inwardly rectifying K+ current in cerebellar granule cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.93:11191–11195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, L. W. (1982). The projections of the ventral tegmental area and adjacent regions: A combined fluorescent retrograde tracer and immunofluorescence study in the rat. Brain Res. Bull.9:321–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, L., Barraud, P., Andersson, E., Kirik, D., and Bjorklund, A. (2005). Identification of dopaminergic neurons of nigral and ventral tegmental area subtypes in grafts of fetal ventral mesencephalon based on cell morphology, protein expression, and efferent projections. J. Neurosci.25:6467–6477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomzig, A., Laube, G., Pruss, H., and Veh, R. W. (2005). Pore-forming subunits of K-ATP channels, Kir6.1 and Kir6.2, display prominent differences in regional and cellular distribution in the rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol.484:313–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickenden, A. (2002). K(+) channels as therapeutic drug targets. Pharmacol. Ther.94:157–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickenden, A. D., Yu, W., Zou, A., Jegla, T., and Wagoner, P. K. (2000). Retigabine, a novel anti-convulsant, enhances activation of KCNQ2/Q3 potassium channels. Mol. Pharmacol.58:591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickman, K., Karschin, C., Karschin, A., Picciotto, M. R., and Clapham, D. E. (2000). Brain localization and behavioral impact of the G-protein-gated K+ channel subunit GIRK4. J. Neurosci.20:5608–5615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wischmeyer, E., Döring, F., Wischmeyer, E., Spauschus, A., Thomzig, A., Veh, R. W., and Karschin, A. (1997). Subunit interactions in the assembly of neuronal Kir3.0 inwardly rectifying K+ channels. Mol. Cell. Neurosci.9:194–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, K., Ji, J. J., Yuan, H., Miki, T., Sato, S., Horimoto, N., Shimizu, T., Seino, S., and Inagaki, N. (2001). Protective role of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in hypoxia-induced generalized seizure. Science292:1543–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]