Abstract

1. The cholinergic system is important in cognition and behavior as well as in the function of the cerebral vasculature.

2. Hyperhomocysteinemia is a risk factor for development of both dementia and cerebrovascular disease.

3. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE) are serine hydrolase enzymes that catalyze the hydrolysis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, a key process in the regulation of the cholinergic system.

4. It has been hypothesized that the deleterious effects of elevated homocysteine may, in part, be due to its actions on cholinesterases.

5. To further test this hypothesis, homocysteine and a number of its metabolites and analogues were examined for effects on the activity of human cholinesterases.

6. Homocysteine itself did not have any measurable effect on the activity of these enzymes.

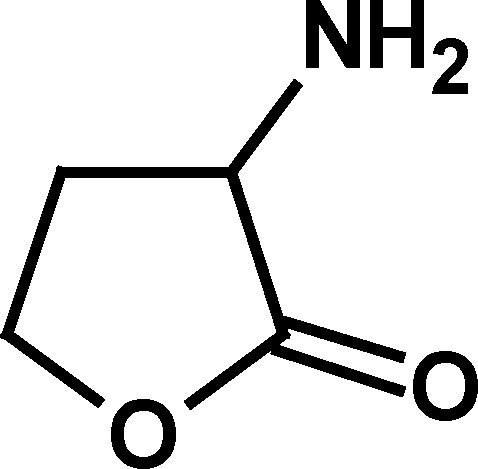

7. Homocysteine thiolactone, the cyclic metabolite of homocysteine, slowly and irreversibly inhibited the activity of human AChE.

8. Conversely, this metabolite and some of its analogues significantly enhanced the activity of human BuChE.

9. Structure–activity studies indicated that the unprotonated amino group of homocysteine thiolactone and related compounds represents the essential feature for activation of BuChE, whereas the thioester linkage appears to be responsible for the slow AChE inactivation.

10. It is concluded that hyperhomocysteinemia may exert its adverse effects, in part, through the metabolite of homocysteine, homocysteine thiolactone, which is capable of altering the activity of human cholinesterases, the most pronounced effect being BuChE activation.

KEY WORDS: acetylcholinesterase, butyrylcholinesterase, acetylcholine, homocysteine, Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia

INTRODUCTION

Homocysteinuria has been linked to mental impairment and vascular disease for almost a half century (Carson and Neill, 1962; Gibson et al., 1964) and hyperhomocysteinemia has come to be recognized as a common risk factor for the development of both Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and vascular disease (McCaddon et al., 2001; Budge et al., 2002; Seshadri et al., 2002; Elias et al., 2005). Cholinergic dysfunction is associated with both these disorders (Whitehouse et al., 1981; Coyle et al., 1983; Court and Perry, 2003; Román and Kalaria, in press).

In the cholinergic system, acetylcholinesterase (AChE, E.C. 3.1.1.7) and butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE, E.C. 3.1.1.8) catalyze the hydrolysis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (Silver, 1974), thereby regulating its duration of action (Giacobini, 2003; Darvesh et al., 2003a). A low acetylcholine level in the brain is associated with cognitive dysfunction (Bartus et al., 1982). Induced hyperhomocysteinemia in the rat was reported to result in memory loss in these animals (Reis et al., 2002). It has been speculated that this effect may be due to inhibition of BuChE by homocysteine (Stefanello et al., 2003a,b, 2005). However, BuChE-specific inhibitors have been shown to improve memory in rats (Greig et al., 2005). Furthermore, drugs used to treat cognitive and behavioral symptoms in dementia inhibit cholinesterases (Greig et al., 2002; Giacobini, 2000). The effect of homocysteine and its metabolites on human cholinesterases is not well understood. The association between homocysteine and dementia prompted the present study, which examines the in vitro effect of homocysteine and related compounds on human cholinesterases.

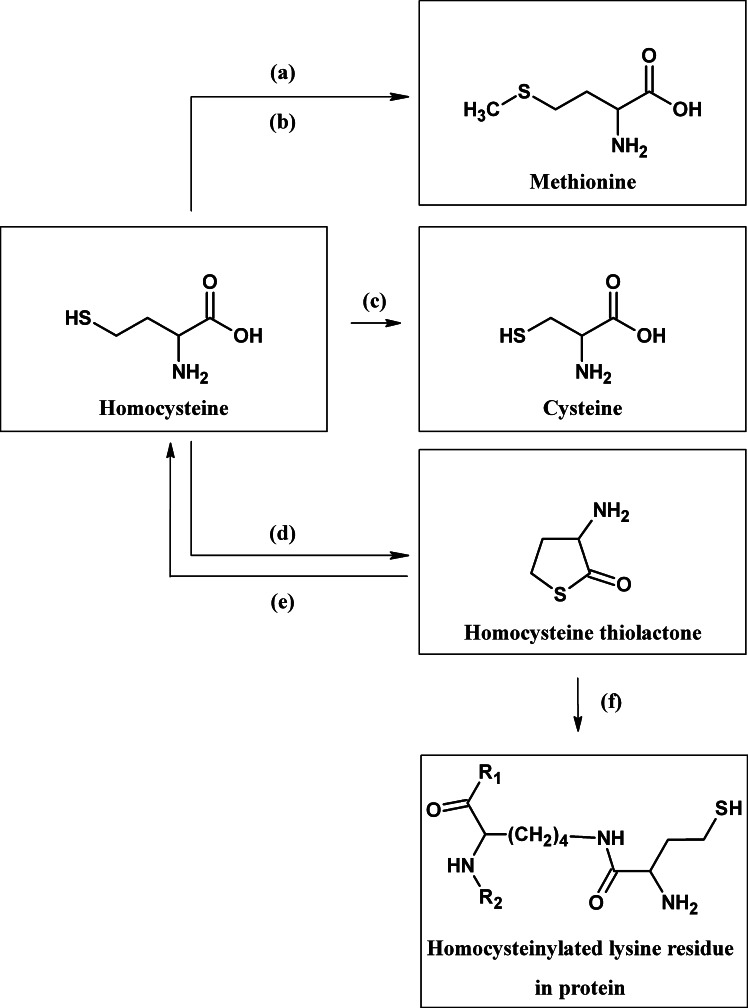

Homocysteine, a nonprotein amino acid, is an important intermediate in a number of pathways such as the metabolism of cysteine and methionine (Fig. 1). Within this system, homocysteine can be converted to the cyclic thioester, homocysteine thiolactone, through the action of methionyl tRNA synthase (Jakubowski and Goldman, 1993) (Fig. 1). Homocysteine thiolactone, in turn, is converted back to homocysteine by the enzyme paraoxonase (homocysteine thiolactone hydrolase; Jakubowski, 2000) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Metabolism of homocysteine (a) methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; (b) coenzymes: vitamin B12 and methylenetetrahydrofolate from folic acid; (c) cystathione β-synthase and cystathionase; (d) methionyl t-RNA synthase; (e) paraoxonase also know as homocysteine thiolactonase); (f) lysine residue on a protein.

Homocysteine thiolactone has been shown to have adverse effects on proteins (Jakubowski, 1999, 2000; Sauls et al., 2006; Garel and Tawfik, 2006). Furthermore, it has been observed that in AD and vascular diseases, genetic polymorphisms that decrease paraoxonase activity also constitute a risk factor for these diseases (McCully et al., 1988; Imai et al., 2000; Malin et al., 2001; Paragh et al., 2002; Shi et al., 2004). Decreased paraoxonase activity could lead to higher levels of homocysteine thiolactone, implicating this metabolite in disease mechanisms.

In light of the foregoing considerations we hypothesized that the risk for AD and vascular diseases presented by homocysteine could be due, in part, to its derivative, homocysteine thiolactone. Therefore, homocysteine, its cyclic thioester and a number of related compounds were tested for effects on human cholinesterases. Portions of this work have been presented in abstract form (Darvesh et al., 2003b).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE, EC 3.1.1.8) purified from human plasma (10 units = 0.16 nmol) and the recombinant D70G mutant were a gift from Dr. Oksana Lockridge (University of Nebraska Medical Center). Recombinant human acetylcholinesterase (AChE, EC 3.1.1.7) (2000 units/mg), acetylthiocholine, alanine ethyl ester, γ-butyrolactone, butyrylthiocholine, cyclopentylamine, cycloserine, 5,5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), glycine ethyl ester, homocysteine, and γ-thiobutyrolactone were from Sigma–Aldrich. 2-Acetylbutyrolactone, N-acetylhomocysteine thiolactone, alanine, γ-aminobutyric acid, homocysteine thiolactone, homoserine, and homoserine lactone were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Aniline was from BDH and glycine was from Caledon.

Esterase Activity

The esterase activity of AChE or BuChE was determined using acetylthiocholine or butyrylthiocholine, respectively, by a modification of the method described by Ellman et al. (1961). Homocysteine thiolactone and its analogues were dissolved in distilled water or buffer to produce neutral stock solutions up to 0.3 M. The working DTNB solution was prepared by mixing 3.6 mL of a solution containing 10 mM DTNB and 20 mM NaHCO3 in 0.1 M phosphate buffer at pH 7.0 with 96.4 mL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer at pH 8.0. The assays were carried out by mixing 1.35 mL of buffered DTNB working solution (pH 8.0), 0.05 mL (0.04 unit) of BuChE or AChE stock solution in 0.1% gelatin and 0.05 mL of distilled water or 0.05 mL of test compound in a quartz cuvette of 1 cm path-length. Absorbance of this solution was calibrated to zero and the reaction was commenced by adding 0.05 mL of aqueous acetylthiocholine or butyrylthiocholine solution of concentrations varying between 2.0×10−4 and 3.0×10−5 M, giving a final volume of 1.5 mL. The reactions were performed at 22°C. The rate of change of absorbance (ΔA/min), reflecting the rate of hydrolysis of acetylthiocholine or butyrylthiocholine was recorded every 5 s for 1 min, using a Milton-Roy UV–Vis spectrophotometer, set at λ=412 nm. All reactions were carried out at least in triplicate and the values were averaged.

As control experiments, reactions were carried out with each enzyme and test compounds as well as DTNB, but in the absence of thiocholine substrates. No change in absorbance was observed. This indicated that none of the test compounds were substrates for the enzymes, nor did they react with DTNB.

A total of 0.1 unit of BuChE or AChE is defined as the amount of enzyme that produces a ΔA/min of 1.0 absorbance units under standard conditions using 1.6×10−4 M of substrate.

Sample Dialysis

The dialysis experiments were carried out to determine whether the interaction between homocysteine thiolactone with cholinesterases was reversible or irreversible. Enzyme samples that had been incubated with homocysteine thiolactone were dialyzed, to remove this compound, against 2 L of 0.01 M Tris buffer pH 8, at 4°C for 4 h followed by dialysis overnight against a further 2 L of buffer. In order to determine whether the compound had a reversible or irreversible effect on the enzyme, the dialyzed samples were then reexamined for esterase enzyme activity as before.

DATA ANALYSIS

Analysis of Irreversible Enzyme Inhibition

The second order rate constant (k a), describing the irreversible inactivation of AChE over time, was calculated by plotting ln(e 0/e t)/[I] versus time. In this expression, e 0 is the enzyme activity at time zero, without pre-incubation of the enzyme and the inhibitor and e t is the enzymatic activity at time “t” minutes of pre-incubation; [I] is the inhibitor concentration. The slope of this plot gave the k a value (Webb, 1963; Reiner and Radić, 2000).

Analysis of Reversible Enzyme Activation

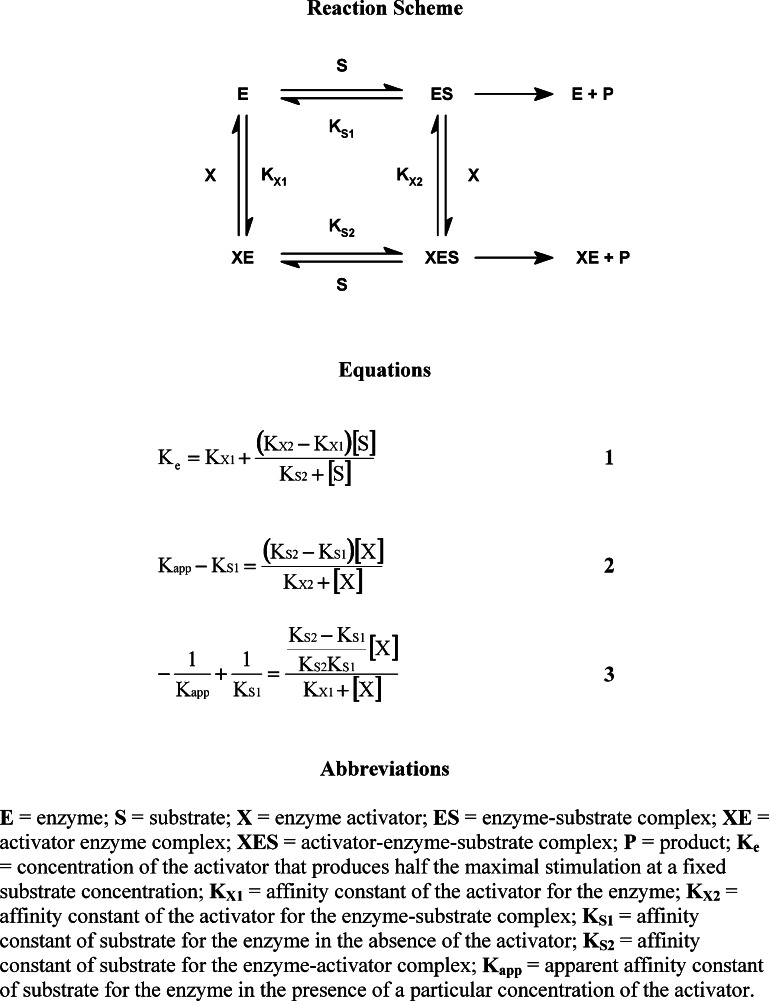

Some enzymes show improved catalysis in the presence of molecules that are termed activators, although the enzymes are able to function in the absence of such compounds. Therefore, these molecules have been termed “nonessential” activators (Dixon and Webb, 1979). Stimulation of an enzyme by a nonessential activator characteristically increases with increasing substrate concentration (Kruger-Thiemer, 1969; Dixon and Webb, 1979). Thus, the activation “constant” (K e), as defined by Fontes et al. (2000), is only constant at fixed substrate concentration as shown in Eq. (1) (Fig. 2). In order to compare the activation constants of different compounds with each other, it was essential to determine this value at a common fixed substrate concentration. Activation constants (K act) were therefore calculated at infinite substrate concentration for all activators studied.

Fig. 2.

Reaction scheme and equations describing the activation of butyrylcholinest-erase for substrate hydrolysis.

To determine K act values, BuChE activity was examined in the presence and absence of each activator. A modified direct linear plot (1/v versus [s]/v, where v is reaction velocity and [s] is substrate concentration) (Cornish-Bowden, 1995) was utilized to determine the substrate affinity constant (K m) and maximum velocity (V max), in the absence of the activator, as well as apparent K m and V max values in the presence of different concentrations of the activator. Changes in the kinetic parameters induced by the activator allowed determination of binding constants K X 1 and K X 2 (Fig. 2) for each activator. A direct linear plot (1/ΔK m versus [X], where ΔK m is the change in substrate affinity constant and [X] is the activator concentration) (Cornish-Bowden, 1995) of change in substrate affinity (K m values) versus activator concentration gave K X 2 and K S 2 values in Eq. (2) (Fontes et al., 2000).

The K

X

1 value was determined by a direct linear plot ([X] versus  , where K

app is the apparent substrate affinity in the presence of activator and K

S1 is the substrate affinity constant) (Cornish-Bowden, 1995

), as described in Eq. (3) (Fig. 3; Fontes et al., 2000).

, where K

app is the apparent substrate affinity in the presence of activator and K

S1 is the substrate affinity constant) (Cornish-Bowden, 1995

), as described in Eq. (3) (Fig. 3; Fontes et al., 2000).

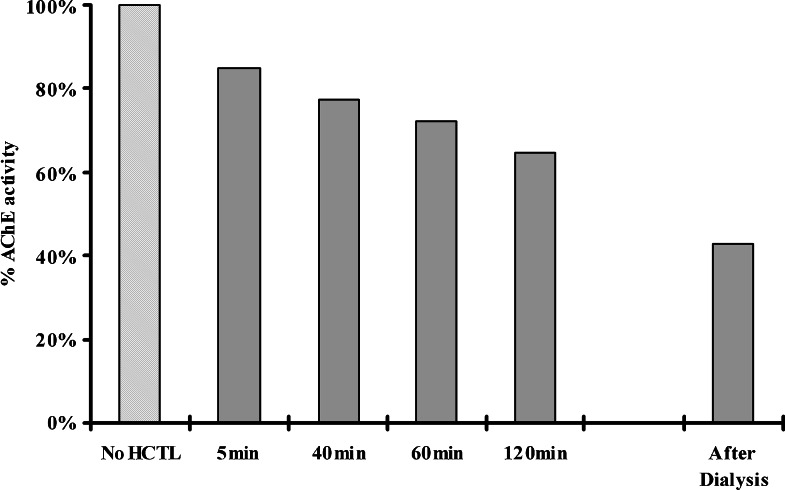

Fig. 3.

Irreversible inhibition of the activity of human acetylcholinesterase (0.04 unit) by homocysteine thiolactone (HCTL, 1 mM). Removal of homocysteine thiolactone by dialysis did not restore the activity of the enzyme.

Determined disassociation constants (K X 1 and K X 2) and induced changes in enzyme substrate affinity (K S2 values) allowed for the generation of K e values (Eq. (1), Fig. 2). Finally, a plot of the reciprocal of calculated K e values versus the reciprocals of corresponding substrate concentrations (Eq. (1), Fig. 2) gave the K act value from the y-intercept, a theoretical activator disassociation constant at infinite substrate concentration.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Homocysteine did not have any effect on the esterase activity of human AChE or BuChE. On the other hand, the cyclic thioester of this amino acid, homocysteine thiolactone, was observed to alter the rate of substrate hydrolysis by human cholinesterases, inhibiting AChE but stimulating BuChE.

Effect of Homocysteine Thiolactone on Acetylcholinesterase

Homocysteine thiolactone exhibited a time-dependent deactivation of AChE (Fig. 3). The inhibitory effect of the thiolactone on AChE could not be reversed by dialysis of the incubation mixture, indicating an irreversible interaction with the enzyme (Fig. 3). The inactivation of AChE was a relatively slow process, with a second-order rate constant (k a value) of only 11 M−1 min−1. This rate of deactivation of AChE is about 100,000-fold less than that produced by the pseudo-irreversible inhibitor, physostigmine, with a k a value of 6.2×105 M−1 min−1 (Darvesh et al., 2003c). The nature of the interaction that produces slow inactivation with AChE may well involve covalent bond formation between the reactive thioester moiety of homocysteine thiolatone and AChE amino acid residues having a basic side chain. A similar reaction of this compound has been observed before with other proteins, such as trypsin (Jakubowski, 1999) and fibrinogen (Sauls et al., 2006). This reaction (Fig. 1), called “homocysteinylation” (Jakubowski, 1999), involves formation of an amide bond by reaction of homocysteine thiolactone with lysine residues. This process of “homocysteinylation” is thought to result in protein denaturation. Since the process of inactivation of AChE is very slow, it is unlikely that the interaction between homocysteine thiolactone and this enzyme would have any significant impact on the cholinergic system.

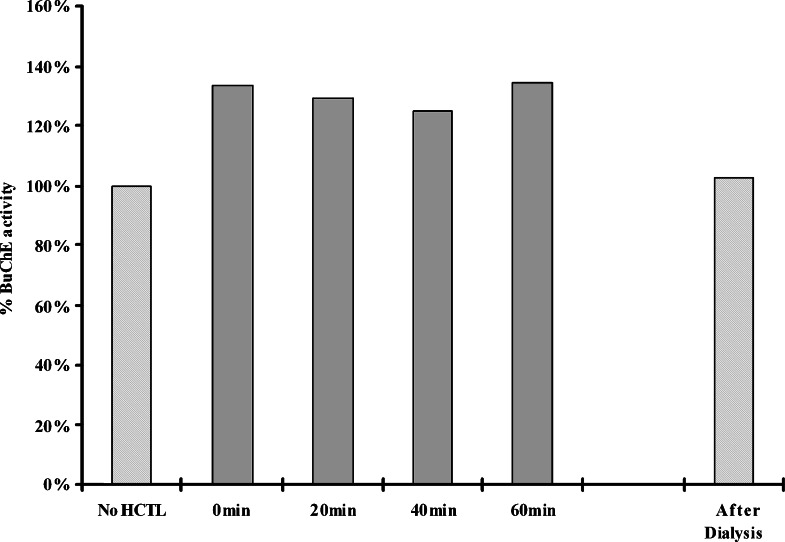

Effects of Homocysteine Thiolactone on Butyrylcholinesterase

Incubation of homocysteine thiolactone with BuChE produced an immediate stimulation of the activity of this enzyme, an effect that remained unchanged with longer pre-incubation (Fig. 4). In addition, BuChE stimulation by homocysteine thiolactone was reversible since dialysis of the incubation mixture restored the enzyme to the original level of activity. Detailed analysis of the effect of homocysteine thiolactone concentration on BuChE catalysis produced Lineweaver–Burke plots typical of a nonessential activator (Kruger-Thiemer, 1969; Dixon and Webb, 1979). That is, increasing substrate concentration increased the effect of homocysteine thiolactone on BuChE catalysis. Based on these observations, the activation of BuChE by the thiolactone appears to be non-covalent in nature. Why covalent bond formation should occur with AChE, which has only six surface lysine residues (Kryger et al., 2000; DeLano, 2002; Berman et al., 2000), and not with BuChE, which has 28 such residues (Nicolet et al., 2003; DeLano, 2002; Berman et al., 2000), is not immediately apparent. However, the general environment in which the lysine residues are located (hydrophobic or hydrophilic) and what other amino acid residues are nearby, could have a profound effect on the availability of lysine residues of BuChE for covalent reaction with homocysteine thiolactone (Garel and Tawfik, 2006). In addition, the extent of glycosylation, higher in BuChE (Lockridge et al., 1979; Lockridge et al., 1987) than in AChE (Kronman et al., 1995) may influence the susceptibility of the enzyme to “homocysteinylation.”

Fig. 4.

Reversible enhancement of the activity of human butyrylcholinesterase (0.04 unit) by homocysteine thiolactone (HCTL, 1 mM). Removal of homocysteine thiolactone by dialysis restored the activity of the enzyme.

Structure–Activity Relationships

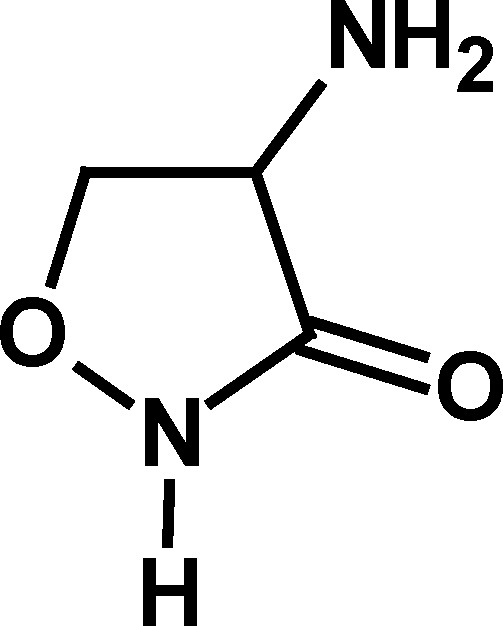

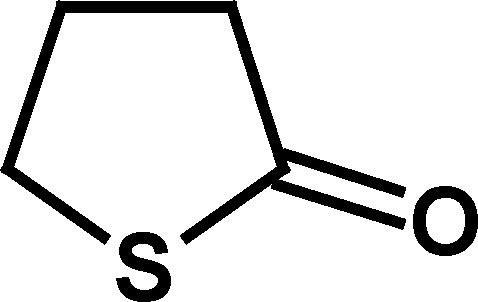

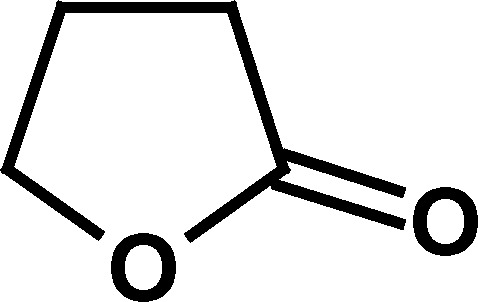

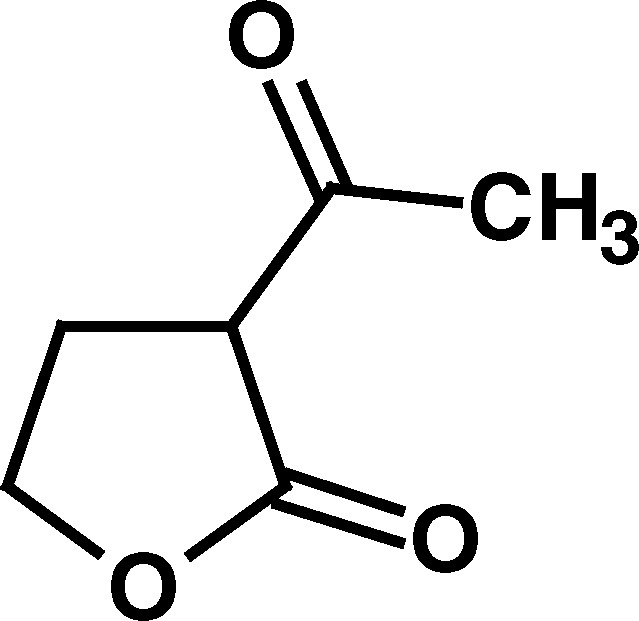

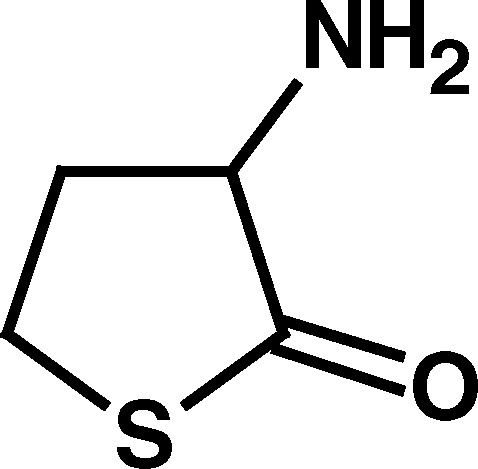

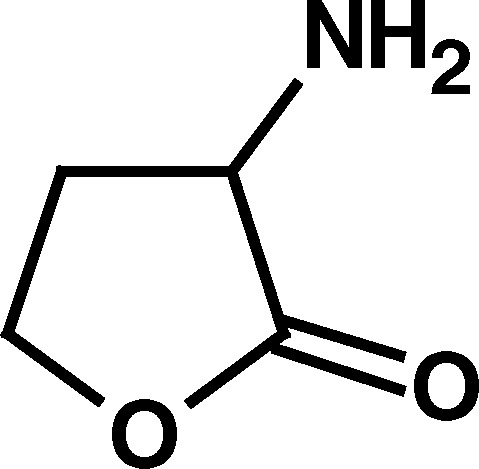

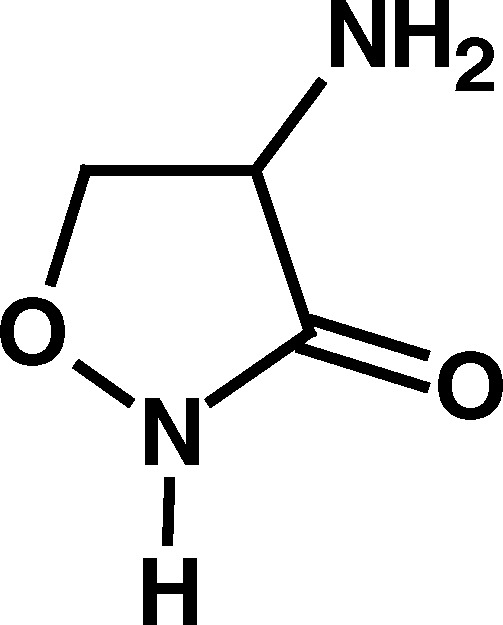

To determine the salient structural features of homocysteine thiolactone (1) that affected the activity of cholinesterases, a series of its analogues were examined (Table I).

Table I.

Effect of Homocysteine Thiolactone and its Analogues on Human Butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE) and Acetylcholinesterase (AChE)

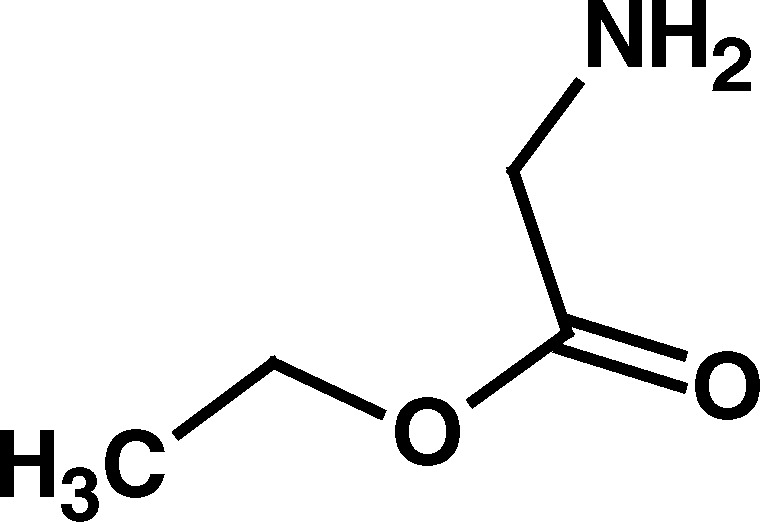

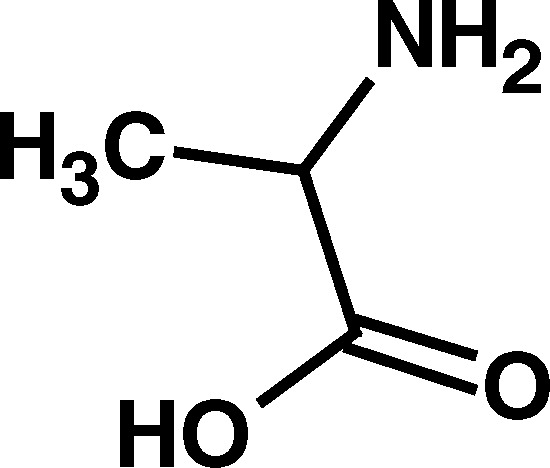

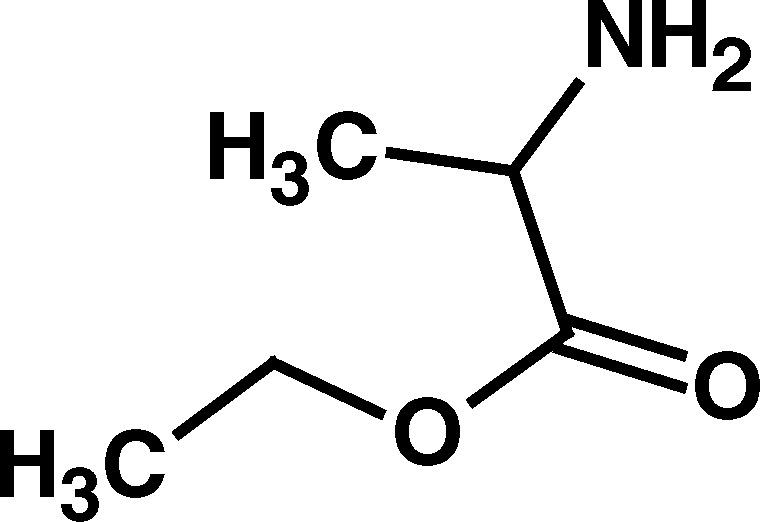

| Compound | Structure | BuChE (K act, μM) | AChE (k a, M−1 min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Homocysteine thiolactone | 368±43 | 11.5±3.3 | |

| 2. Homoserine lactone | 40.4±2.8 | No effect | |

| 3. Cycloserine | 877±231 | No effect | |

| 4. γ-Thiobutyrolactone | No effect | 3.11±0.90 | |

| 5. γ –Butyrolactone | No effect | No effect | |

| 6. 2-Acetylbutyrolactone | No effect | No effect | |

| 7. N-Acetylhomocysteine thiolactone | No effect | Slight inhibition | |

Only compounds with a thiolactone ring such as homocysteine thiolactone (1), γ-thiobutyrolactone (4), and N-acetylhomocysteine lactone (7) exhibited the time-dependent deactivation of AChE (Table I). For all of these compounds, the inhibitory effect on AChE was slow, with relatively small second-order rate constants (k a values, Table I), and required high concentrations of compounds (1–100 mM) and long incubation periods to produce an effect. The observation that the oxygen analogue of 1, homoserine lactone (2), and the analogous cycloserine (3) did not produce any effect on AChE supports the notion that the ring opening of the more labile thiolactone moiety in compounds 1, 4, and 7 is what leads to AChE inactivation. As indicated above, deactivation of AChE by these thioesters was many orders of magnitude slower than that produced for the same enzyme by the carbamate physostigmine (Darvesh et al., 2003c), further indicating that inhibition of AChE by homocysteine thiolactone or its analogues may not be important in affecting changes to cholinergic function.

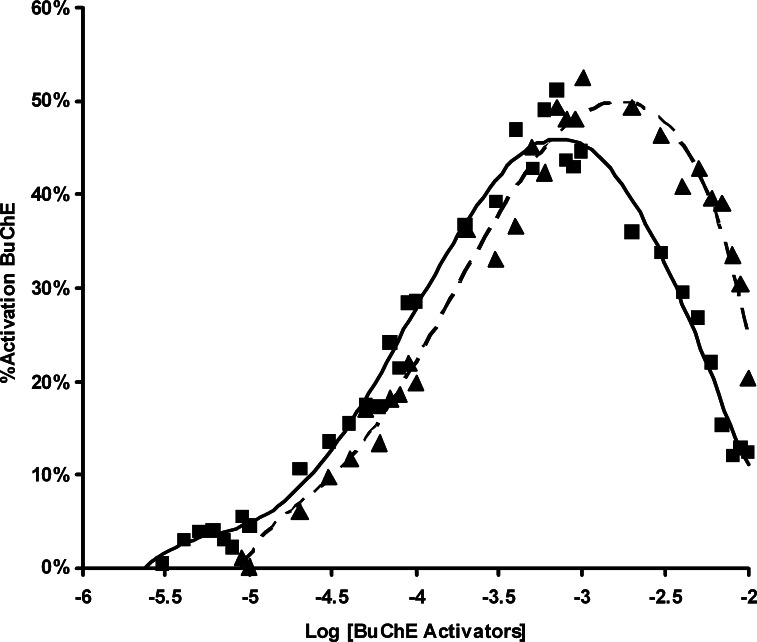

Homoserine lactone (2), like homocysteine thiolactone (1), stimulated the activity of BuChE (Table I, Fig. 5). As seen in Fig. 5, both homocysteine thiolactone (1) and homoserine lactone (2) begin BuChE stimulation in the 1–10 μM range and increase to a maximum stimulation with 1 mM of the lactone. Although the serum concentration of homocysteine thiolactone is uncertain, its level would be expected to increase with elevated homocysteine, a level of 10 μM being considered a health risk (Budge et al., 2002).

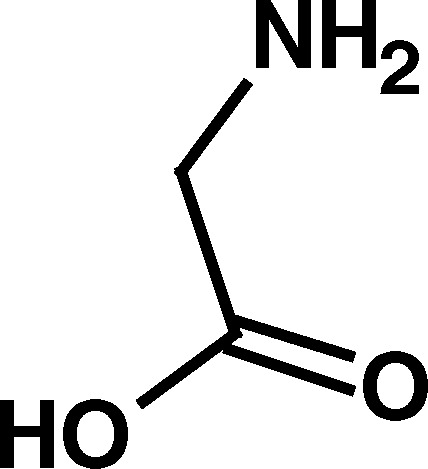

Of the compounds initially examined (Table I), the BuChE activators were compounds with a five-membered heterocyclic ring system and with a primary amino group outside the ring in the α-position to the ring carbonyl (i.e., compounds 1–3; Table I). This primary amino group appeared to be of major importance to BuChE activation since the absence of this α-amino substituent, as with γ-thiobutyrolactone (4) and γ-butyrolactone (5), abolished the BuChE-stimulatory effect. Furthermore, replacing the α-amino group with α-acetyl group, as in 2-acetyl butyrolactone (6), or derivatizing the primary amino group, in N-acetyl homocysteine thiolactone (7), also abolished BuChE stimulation (Table I). However, homocysteine, homoserine, glycine, alanine, and cyclopentyl amine, all with a primary amino group did not produce BuChE stimulation. This suggested that the α-amino group of the compounds that stimulated BuChE (compounds 1–3) may have some unique chemical properties not found in the compounds that did not stimulate BuChE. As a first approach, the acid–base properties of the three BuChE activators were compared with corresponding nonactivators (Table II).

Table II.

Effect of pK a of the Primary Amino Group on BuChE Stimulation

| Compound | Structure | pK a | BuChE interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Homocysteine thiolactone | 6.5 | Stimulation | |

| 2. Homoserine lactone | 6.3 | Stimulation | |

| 3. Cycloserine | 7.2 | Stimulation | |

| 8. Glycine | 9.64a | No stimulation | |

| 9. Glycine ethyl ester | 7.5 | Stimulation | |

| 10. Alanine | 9.61a | No stimulation | |

| 11. Alanine ethyl ester | 7.7 | Stimulation | |

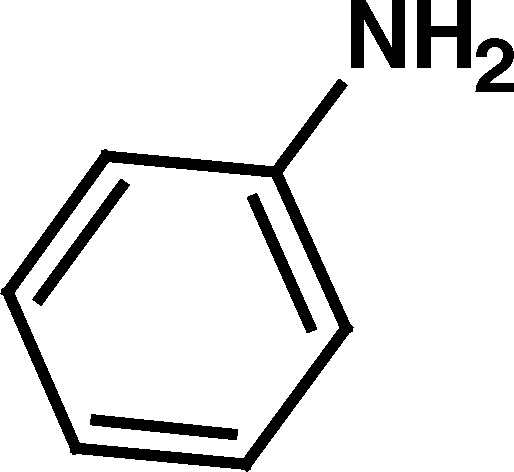

| 12. Aniline | 4.61a | Stimulation | |

| 13. Cyclopentylamine | 10.2 | No stimulation | |

aCalculated using Advanced Chemistry Development (ACD/Labs) Software Solaris V4.67 ((C) 1994-2005 ACD/Labs).

Titrimetric determination of the pK

a (the pH where [R-+NH3]=[R-NH2]) of homocysteine thiolactone indicated that unlike most primary amino groups, such as that of cyclopentylamine (13) (pK

a=10.2) and most α-amino acids (pK

a range 9–11), the pK

a of homocysteine thiolactone was 6.5 (Table II). Furthermore, homoserine lactone (2) and cycloserine (3) were also found to have low pK

a values for primary amines, with the best activator (2) having the lowest pK

a value (Table II). At pH 8, under the conditions utilized for these studies, the BuChE-stimulating compounds (1–3) would be predominantly in the unprotonated form (i.e., R-NH2

R-+NH3). Additionally, for the most potent BuChE activators (compounds 1 and 2) the concentration of the apparently non-stimulatory cationic form (R-+NH3) would be very small. It was considered that the relatively low amino pK

a value of homocysteine thiolactone (1) and similar BuChE activators (2 and 3) was related to the proximity of the nitrogen to the esterified carbonyl group. To test this notion, structurally different molecules with primary amino groups next to esterified carbonyls were also examined (Table II). As can be seen from this table, the ethyl esters of glycine (9, pK

a 7.56) and alanine (11; pK

a 8.03) also stimulated BuChE, while the corresponding unesterified amino acids (pK

a 9.64 and 9.61, compounds 8 and 10, respectively) showed no stimulation of BuChE. On the other hand, the aromatic primary amine, aniline, with a low pK

a value (4.61), was also found to stimulate BuChE (Table II). The low pK

a value of aniline can be attributed to conjugation of the lone pair of electrons on the amino group into the aromatic ring (Clayden et al., 2001

). A similar, but more limited, withdrawal of this nitrogen lone pair might be expected to occur into the adjacent carbonyl of the thioester (1) or esters (2, 3, 9, and 11), lowering the pK

a to an extent not possible with a corresponding amino acid (8 or 10), or a simple alkyl amine (13). Therefore, for compounds such as homocysteine thiolactone (1), the major requirement for BuChE interaction, causing stimulation, appears to be the neutral primary amino function.

R-+NH3). Additionally, for the most potent BuChE activators (compounds 1 and 2) the concentration of the apparently non-stimulatory cationic form (R-+NH3) would be very small. It was considered that the relatively low amino pK

a value of homocysteine thiolactone (1) and similar BuChE activators (2 and 3) was related to the proximity of the nitrogen to the esterified carbonyl group. To test this notion, structurally different molecules with primary amino groups next to esterified carbonyls were also examined (Table II). As can be seen from this table, the ethyl esters of glycine (9, pK

a 7.56) and alanine (11; pK

a 8.03) also stimulated BuChE, while the corresponding unesterified amino acids (pK

a 9.64 and 9.61, compounds 8 and 10, respectively) showed no stimulation of BuChE. On the other hand, the aromatic primary amine, aniline, with a low pK

a value (4.61), was also found to stimulate BuChE (Table II). The low pK

a value of aniline can be attributed to conjugation of the lone pair of electrons on the amino group into the aromatic ring (Clayden et al., 2001

). A similar, but more limited, withdrawal of this nitrogen lone pair might be expected to occur into the adjacent carbonyl of the thioester (1) or esters (2, 3, 9, and 11), lowering the pK

a to an extent not possible with a corresponding amino acid (8 or 10), or a simple alkyl amine (13). Therefore, for compounds such as homocysteine thiolactone (1), the major requirement for BuChE interaction, causing stimulation, appears to be the neutral primary amino function.

Fig. 5.

Activation of BuChE by increasing concentrations of homocysteine thiolactone (1) and homoserine lactone (2). Stimulation profile of BuChE (0.04 unit) hydrolysis of butyrylthiocholine (0.16 mM), by homocysteine thiolactone (▪) and homoserine lactone (▴).

Stimulation of BuChE by neutral amines is in contrast with observations made with other BuChE activators, such as choline esters and other tetraalkylammonium salts, compounds that have a permanent cationic moiety (Masson et al., 1999; Stojan et al., 2002). These latter compounds are known to effect activation of BuChE by conformational changes resulting from binding of these cationic compounds to a peripheral anionic site (Masson et al., 1999).

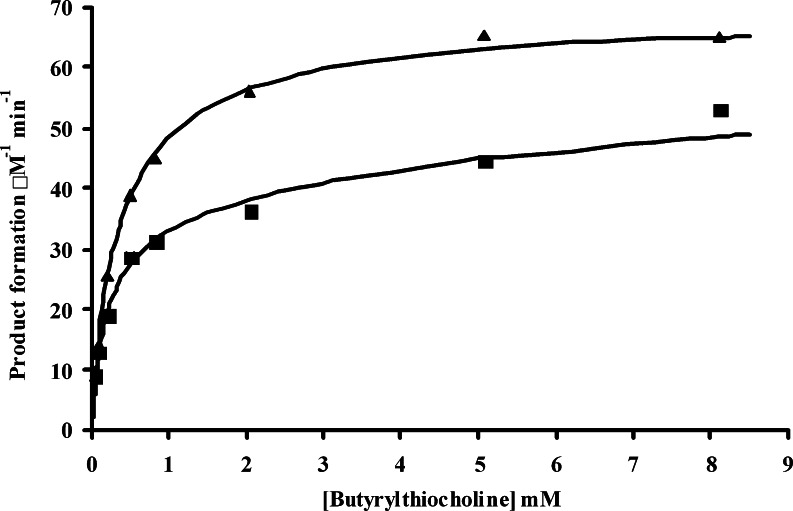

The crystal structures of AChE (Sussman et al., 1991; Kryger et al., 2000) and BuChE (Nicolet et al., 2003) show that active site in these enzymes is found at the bottom of a 20Å gorge, and is composed of a catalytic triad of serine, histidine, and glutamate. Also within the active site gorge there is an acyl pocket where the acyl group of the choline ester is held, and a tryptophan cation-binding site where the positive nitrogen of the choline moiety is held, through π-cation interaction. Prior to entry into the active site gorge, the substrate may first interact with an anionic site at the lip of the gorge. This peripheral anionic site consists of aspartate (D70) and tyrosine (Y332) residues in BuChE (Masson et al., 1999). It is well established that higher concentrations of acetylcholine lead to activation of BuChE (Erikson and Augustinsson, 1979) by interaction of this cationic substrate with the peripheral anionic site (Masson et al., 1999). In contrast, our observations have indicated that BuChE activators like homocysteine thiolactone are neutral rather than cationic, under the conditions (Table II). This implied that homocysteine thiolactone activates BuChE by a mechanism that does not require an anionic residue for interacting with the enzyme. This notion was further explored by employing a variant of human BuChE (D70G) that does not have an anionic residue at the peripheral site. This mutant enzyme is not activated by cationic substrate molecules (Masson et al., 1999). However, the presence of 1 mM homocysteine thiolactone was observed to stimulate the activity of D70G BuChE (Fig. 6). This activation is comparable to that produced in wild-type BuChE. This implies that the binding mechanism of homocysteine thiolactone does not require an anionic amino acid residue. Thus, binding of the homocysteine thiolactone to BuChE produces a conformational change that increases the activity of BuChE to an extent comparable to substrate activation of wild-type BuChE.

CONCLUSIONS

Homocysteine itself does not have any effect on human cholinesterases but its metabolite, homocysteine thiolactone affects the activity of these enzymes. Homocysteine thiolactone inhibits AChE but this process is slow and might not be expected to influence the natural turnover of this enzyme. On the other hand, homocysteine thiolactone stimulates the activity of BuChE. Constant stimulation of BuChE by homocysteine thiolactone could be expected to decrease acetylcholine levels. Low acetylcholine levels are known to be responsible for symptoms in Alzheimer and vascular diseases.

Fig. 6.

Hydrolysis of butyrylthiocholine (0.01–8 mM) by D70G BuChE in the absence (▪) and presence (▴) of 1 mM homocysteine thiolactone.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation, Capital District Health Authority Research Fund, Brain Tumour Foundation of Canada, the Natural Sciences Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Committee on Research and Publications of Mount Saint Vincent University, and Alzheimer Society of Nova Scotia for Phyllis Horton Bursary (RW).

REFERENCES

- Bartus, R. T., Dean, R. L., III, Beer, B., and Lippa, A. S. (1982). The cholinergic hypothesis of geriatric memory dysfunction. Science217:408–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman, H. M., Westbrook, J., Feng, Z., Gilliland, G., Bhat, T. N., Weissig, H., Shindyalov, I. N., and Bourne P. E. (2000). The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res.28:235–242. Retrieved from (http://www.pdb.org/). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Budge, M. M., de Jager, C., Hogervorst, E., and Smith, A. D. (2002). Oxford Project to Investigate Memory and Ageing (OPTIMA). Total plasma homocysteine, age, systolic blood pressure, and cognitive performance in older people. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc.50:2014–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson, N. A., and Neill, D. W. (1962). Metabolic abnormalities detected in a survey of mentally backward individuals in Northern Ireland. Arch. Dis. Child.37:505–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayden, J., Greeves, N., Warren, S., and Wothers, P. (2001). Organic Chemistry. Oxford University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Cornish-Bowden, A. (1995). Fundamentals of Enzyme Kinetics, 2nd edn. Portland Press, London.

- Court, J. A., and Perry, E. K. (2003). Neurotransmitter abnormalities in vascular dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr.15:81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle, J. T., Price, D. L., and DeLong, M. R. (1983). Alzheimer’s disease: A disorder of cortical cholinergic innervation. Science219:1184–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvesh, S., Hopkins, D. A., and Geula, C. (2003a). Neurobiology of butyrylcholinesterase. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.4:131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvesh, S., Walsh, R., and Martin, E. (2003b). Interaction of homocysteine metabolites with butyrylcholinesterase: A risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Can. J. Neurol. Sci.30:S48. [Google Scholar]

- Darvesh, S., Walsh, R., Kumar, R., Caines, A., Roberts, S., Magee, D., Rockwood, K., and Martin, E. (2003c). Inhibition of human cholinesterases by drugs used to treat Alzheimer disease. Alz. Dis. Assoc. Disord.17:117–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano, W. L. (2002). The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA Retrieved from http://www.pymol.org.

- Dixon, M., and Webb, E. C. (1979). Enzymes, 3rd edn. Academic Press, New York.

- Elias, M. F., Sullivan, L. M., D’Agostino, R. B., Elias, P. K., Jacques, P. F., Selhub, J., Seshadri, S., Au, R., Beiser, A., and Wolf, P. A. (2005). Homocysteine and cognitive performance in the Framingham offspring study: Age is important. Am. J. Epidemiol.162:644–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellman, G. L., Courtney, K. D., Andres, V., Jr., and Feather-Stone, R. M. (1961). A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem. Pharmacol.7:88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, H., and Augustinsson, K. B. (1979). A mechanistic model for butyrylcholinesterase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta567:161–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontes, R., Ribeiro, J. M., and Sillero, A. (2000). Inhibition and activation of enzymes. The effect of a modifier on the reaction rate and on kinetic parameters. Acta Biochim. Pol.47:233–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garel, J., and Tawfik, D. S. (2006). Mechanism of hydrolysis and aminolysis of homocysteine thiolactone. Chemistry.12:4144–4152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacobini, E.(2000). Cholinesterases and Cholinesterase Inhibitors. Martin Dunitz, London.

- Giacobini, E. (2003). Butyrylcholinesterase: Its Function and Inhibitors. Martin Dunitz, London. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J. B., Carson A. J., and Neill, D. W. (1964). Pathological findings in homocystinuria. J. Clin. Pathol.17: 427–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greig, N. H., Lahiri, D. K., and Sambamurti, K. (2002). Butyrylcholinesterase: An important new target in Alzheimer’s disease therapy. Int. Psychogeriatr.14:77–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greig, N. H., Utsuki, T., Ingram, D. K., Wang, Y., Pepeu, G., Scali, C., Yu, Q. S., Mamczarz, J., Holloway, H. W., Giordano, T., Chen, D., Furukawa, K., Sambamurti, K., Brossi, A., and Lahiri, D. K. (2005). Selective butyrylcholinesterase inhibition elevates brain acetylcholine, augments learning and lowers Alzheimer beta-amyloid peptide in rodent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.102:17213– 17218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai, Y., Morita, H., Kurihara, H., Sugiyama, T., Kato, N., Ebihara, A., Hamada, C., Kurihara, Y., Shindo, T., Oh-hashi, Y., and Yazaki, Y. (2000). Evidence for association between paraoxonase gene polymorphisms and atherosclerotic diseases. Atherosclerosis149:435–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski, H. (1999). Protein homocysteinylation: Possible mechanism underlying pathological consequences of elevated homocysteine levels. FASEB J.13:2277–2283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski, H. (2000). Calcium-dependent human serum homocysteine thiolactone hydrolase. A protective mechanism against protein N-homocysteinylation. J. Biol. Chem.275:3957–3962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski, H., and Goldman, E. (1993). Synthesis of homocysteine thiolactone by methionyl-tRNA synthetase in cultured mammalian cells. FEBS Lett.317:237–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronman, C., Velan, B., Marcus, D., Ordentlich, A., Reuveny, S., and Shafferman, A. (1995). Involvement of oligomerization, N-glycosylation and sialylation in the clearance of cholinesterases from the circulation. Biochem. J.311:959–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger-Thiemer, E. (1969). Generalized kinetics of reversible inhibition and activation. Eur. J. Pharmacol.6:357–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kryger, G., Harel, M., Giles, K., Toker, L., Velan, B., Lazar, A., Kronman, C., Barak, D., Ariel, N., Shafferman, A., Silman, I., and Sussman, J. L. (2000). Structures of recombinant native and E202Q mutant human acetylcholinesterase complexed with the snake-venom toxin fasciculin-II. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr.56:1385–1394 (PDB ID: 1B41). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockridge, O., Eckerson, H. W., and La Du, B. N. (1979). Interchain disulfide bonds and subunit organization in human serum cholinesterase. J. Biol. Chem.254:8324–8330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockridge, O., Bartels, C. F., Vaughan, T. A., Wong, C. K., Norton, S. E., and Johnson, L. L. (1987). Complete amino acid sequence of human serum cholinesterase. J. Biol. Chem.262:549–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malin, R., Jarvinen, O., Sisto, T., Koivula, T., and Lehtimaki, T. (2001). Paraoxonase producing PON1 gene M/L55 polymorphism is related to autopsy-verified artery-wall atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis157:301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson, P., Xie, W., Froment, M. T., Levitsky, V., Fortier, P. L., Albaret, C., and Lockridge, O. (1999). Interaction between the peripheral site residues of human butyrylcholinesterase, D70 and Y332, in binding and hydrolysis of substrates. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1433:281–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaddon, A., Hudson, P., Davies, G., Hughes, A., Williams, J. H., and Wilkinson, C. (2001). Homocysteine and cognitive decline in healthy elderly. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord.12:309–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCully, K. S., and Vezeridis, M. P. (1988). Homocysteine thiolactone in arteriosclerosis and cancer. Res. Commun. Chem. Pathol. Pharmacol.59:107–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolet, Y., Lockridge, O., Masson, P., Fontecilla-Camps, J. C., and Nachon, F. (2003). Crystal structure of human butyrylcholinesterase and of its complexes with substrate and products. J. Biol. Chem.278:41141–41147 (PDB ID: 1POP). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paragh, G., Balla, P., Katona, E., Seres, I., Egerhazi, A., and Degrell, I. (2002). Serum paraoxonase activity changes in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci.252:63–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner, E., and Radić, Z. (2000). Mechanism of action of cholinesterase inhibitors. In Giacobini, E. (ed.), Cholinesterases and Cholinesterase Inhibitors. Martin Dunitz, London, pp. 103–119. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, E. A., Zugno, A. I., Franzon, R., Tagliari, B., Matté, C., Lamers, M. L., Netto, C. A., and Wyse, A. T. S. (2002). Pretreatment with vitamins E and C prevent the impairment of memory caused by homocysteine administration in rats. Metab. Brain Dis.17:211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Román, G. C., and Kalaria, R. N. (in press). Vascular determinants of cholinergic deficits in Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Neurobiol. Aging. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sauls, D. L., Lockhart, E., Warren, M. E., Lenkowski, A., Wilhelm, S. E., and Hoffman, M. (2006). Modification of fibrinogen by homocysteine thiolactone increases resistance to fibrinolysis: A potential mechanism of the thrombotic tendency in hyperhomocysteinemia. Biochemistry45:2480–2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshadri, S., Beiser, A., Selhub, J., Jacques, P. F., Rosenberg, I. H., D’Agostino, R. B., Wilson, P. W., and Wolf, P. A. (2002). Plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med.346:476–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J., Zhang, S., Tang, M., Liu, X., Li, T., Han, H., Wang, Y., Guo, Y., Zhao, J., Li, H., and Ma, C. (2004). Possible association between Cys311Ser polymorphism of paraoxonase 2 gene and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease in Chinese. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res.120:201–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman, J. L., Harel, M., Frolow, F., Oefner, C., Goldman, A., Toker, L., and Silman, I. (1991). Atomic structure of acetylcholinesterase from Torpedo californica: A prototypic acetylcholine-binding protein. Science253:872–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanello, F. M., Franzon, R., Tagliari, B., Wannmacher, C., Wajner, M., and Wyse, A. T. (2005). Reduction of butyrylcholinesterase activity in rat serum subjected to hyperhomocysteinemia. Metab. Brain Dis.20:97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanello, F. M., Franzon, R., Wannmacher, C. M., Wajner, M., and Wyse, A. T. (2003b). In vitro homocysteine inhibits platelet Na+, K+-ATPase and serum butyrylcholinesterase activities of young rats. Metab. Brain Dis.18:273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanello, F. M., Zugno, A. I., Wannmacher, C. M., Wajner, M., and Wyse, A. T. (2003a). Homocysteine inhibits butyrylcholinesterase activity in rat serum. Metab. Brain Dis.18:187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojan, J., Golicnik, M., Froment, M. T., Estour, F., and Masson, P. (2002). Concentration-dependent reversible activation–inhibition of human butyrylcholinesterase by tetraethylammonium ion. Eur. J. Biochem.269:1154–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb, J. L. (1963). Enzyme and Metabolic Inhibitors, Vol. I. Academic Press, New York, pp. 535–603.

- Whitehouse, P. J., Price, D. L., Clark, A. W., Coyle, J. T., and DeLong, M. R. (1981). Alzheimer disease: Evidence for selective loss of cholinergic neurons in the nucleus basalis. Ann. Neurol.10:122–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]