Abstract

(1) Presenilin (PS) expression is regulated by several cellular and extracellular factors which change with age and sex. Both age and sex are key risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which is linked to mutations in PS genes. (2) We have analyzed the effect of age and sex on PS expression by northern hybridization and western blot analysis using the cerebral cortex of adult (24 ± 2 weeks) and old (65 ± 5 weeks) mice. (3) Our results demonstrate that PS1 was downregulated and PS 2 was upregulated in old mice of both sexes. The level of PS 1 was relatively higher and that of PS 2 was lower in female than male mice of same age group. Taken together, these findings show age and sex dependent alteration in PS expression, which in turn may influence the signal transduction pathways and consequently brain functions.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Presenilin, Gene expression, Cerebral cortex, Mouse, Age, Sex, Northern hybridization, Western blotting

Introduction

Mutations in presenilin (PS)1 and PS2 genes are associated with the majority of early onset (<65 years) Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Levy-Lahad et al. 1995; Sherrington et al. 1995). The brain of AD patients contains characteristic ‘senile’ plaques, which consist of aggregated β-amyloid peptides. These peptides are produced through proteolytic cleavage of the β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) by γ-secretase, a member of the novel class of intramembranous proteases. PS1 and PS2 are integral membrane proteins, sharing 67% amino acid identity and expressed ubiquitously throughout the brain. They are synthesized as 50–55 kDa holoproteins, which have a short half life (∼30 min). They are endoproteolytically cleaved by a yet uncharacterized enzyme to yield N-terminal fragments (NTF) and C-terminal fragments (CTF) (Thinakaran et al. 1996; De Strooper et al. 1997). These fragments have relatively longer half life. They interact with cofactors namely, nicastrin, APH1, and PEN2 to form stable and functional high molecular weight covalent complexes (Capell et al. 1998; Iwatsubo et al. 2004).

Apart from their role in AD, PS proteins interact with other membrane and cytosolic proteins. These interacting proteins are involved in crucial cellular functions like neuronal differentiation, migration and cortical lamination, neuronal survival, synaptic plasticity, synaptogenesis, memory, protein trafficking, cell adhesion and calcium homeostasis (Parks and Curtis 2007).

Presenilins are widely expressed in the central nervous system and peripheral tissues. In brain, PS expression shows some degree of regional variation and is primarily neuronal. PS1 is expressed more in mouse hippocampus and cerebellum than cerebral cortex (Kovacs et al. 1996; Lee et al. 1996). PS expression is regulated by various factors like development, injury, and AD (Bazan and Lukiw 2002; Renbaum et al. 2003; Ribaut-Barassin et al. 2003; Higashide et al. 2004). In cell culture, PS expression is modulated by various neurotrophic and neuromodulatory factors, like TGF-β, glial cell-neurotrophic factor, retinoic acid, nerve growth factor, cytokines, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Tokuhiro et al. 1998; Ren et al. 1999; Satoh and Kuroda 1999; Counts et al. 2001; Mitsuda et al. 2001). Moreover, the stability of PS protein depends on its post-translational modification by phosphorylation (Walter et al. 1999; Fluhrer et al. 2004; Massey et al. 2004), suggesting a multi-factorial control of the steady state level of PS protein in a tissue.

Though the extracellular factors that regulate PS expression were known, the impact of sex on PS expression during aging was not studied. Most of the workers have studied the expression analysis of PS genes from AD patients. However, due to diverse roles of PS, the study of its expression with normal aging is also important. We have analyzed the expression of PS1 and PS2 as a function of age and sex, which are known risk factors for AD pathogenesis. We have examined whether aging modulates the PS expression at both mRNA and protein levels, and whether this change is sex dependent. The 2.9 kb PS1 and 2.3 kb PS2 transcripts were analyzed by northern hybridization using specific probes, and the expression at protein level was analyzed by western blotting using specific antibodies against PS1NTF and PS2CTF. Our results demonstrate differential regulation of PS1 and PS2 expression with age. PS1 is downregulated, but PS2 is upregulated in the cerebral cortex during aging. Moreover, the expression of PS protein is modulated with sex in adult only. The level of PS1 protein is higher and that of PS2 is lower in males than females. These findings will help in understanding the role of PS in brain functions during aging.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Reagents

AKR strain mice were maintained in the animal house of Zoology Department, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India. The mice were kept under 12 h light and dark schedule and provided with ad libitum standard mice feed and drinking water. The average life span of AKR mice under our laboratory conditions is about 70 ± 5 weeks. Adult (24 ± 2 weeks) and old (65 ± 5 weeks) mice of both sexes were used according to guidelines of the institutional animal ethical committee. The plasmid constructs with murine PS1cDNA insert (pSG5-PS1) and PS2 cDNA insert (pCDNA3-PS2) were kind gift from Bart De Strooper, Belgium. The antiserum Ab14 (against PS1 N-terminal, 1–25 amino acids) [Samuel E Gandy, USA] and PST18 (against the C-terminal loop domain of human PS2) [Helmut Jacobsen, Basel, Switzerland] were used for western blot analysis. Analytical and molecular biology grade chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich India Ltd., β-tubulin type III antibody from Sigma (USA), alpha 32P dCTP (sp. act. 3000Ci/mmol) from the Board of Radiation and Isotope Technology (Hyderabad, India), positively charged nylon membrane from Roche Applied Sciences (Germany), and polyvinyl difluoride (PVDF) membrane from Amersham Biosciences (UK).

RNA Isolation and Northern Hybridization

Adult and old mice of both sexes were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and cerebral cortices were collected on ice. Total RNA from the tissue was isolated by the method of Chomczynski and Sacchi (1987). RNA samples with A260/280 ≥ 1.8 were used further. For northern hybridization, 20 μg total RNA was fractionated by 1.2% agarose-formaldehyde gel electrophoresis. To ensure equal loading of total RNA, the gel was stained with ethidium bromide and photographed by AlphaImager imaging system [(for Windows 2000/XP), Alpha Innotech Corporation, USA]. The gel was transferred onto positively charged nylon membrane by 20 × SSC using a VacuGene XL transfer apparatus (Amersham Biosciences, UK). RNA was fixed by baking the membrane at 120°C for 30 min in a vacuum oven (Heraeus, Germany). Transfer efficiency was checked by staining the membrane with methylene blue. The position of 28S and 18S RNA was marked for measuring the size of PS1 and PS2 mRNAs. Blocking was done in formamide prehybridization buffer (5 × SSC, 5 × Denhardt’s reagent, 50% formamide, 1% SDS, 100 μg/ml salmon sperm DNA) at 42°C for 4 h. Hybridization was carried out at 42°C for 16 h in buffer containing α32P [dCTP] labeled 814 bp KpnI/BamHI (3′UTR) fragment of PS1 cDNA or 535 bp BglII/EcoRV (3′UTR) of PS2 cDNA (5 × 106cpm/ml). Post-hybridization washing was done in 2 × SSC and 0.1% SDS at room temperature for 15 min, followed by stringent washing in pre warmed 0.2 × SSC and 0.1% SDS for 15 min at 42°C, and then in 0.1 × SSC and 0.1% SDS at 42°C for 15 min. The membrane was processed for autoradiography by exposing to X-ray film (Kodak X-OmatTM) between intensifying screens at −70°C for 72 h.

Isolation of Protein and Western Blotting

The membrane enriched protein lysate was prepared from the mouse cerebral cortex. For this purpose, 5% homogenate was prepared in 1 × PBS, 10% sucrose, 0.25 mM PMSF and 10 μg/ml complete mini protease inhibitor cocktail. The homogenate was centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The post-nuclear supernatant was spun at 100,000 × g at 4°C for 1 h using SW28 rotor (Beckman, USA). The pellet was resuspended in protein lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–Cl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, 0.25% deoxycholate, 0.25% NP-40) on ice for 30 min. Then the protein sample was aliquoted and stored at −70°C until further use. The amount of protein in the membrane enriched preparation was estimated by bicinchoninic acid method (Smith et al. 1985).

For western blotting, 50 μg protein sample was mixed with 2X protein loading dye and denatured at 37°C for 10 min (denaturation of sample with SDS by boiling at 95°C was avoided as it enhances the formation of PS aggregate). The proteins were separated by 10% tris–glycine SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membrane by wet transfer method. The membrane was reversibly stained with Ponceau S to check the efficiency of transfer. Then it was blocked in 1X PBS (135 mM NaCl, 8 mM Na2HPO4, 5 mM KCl, and 7 mM KH2PO4), 0.5% BSA (v/v), 0.5% Tween 20 (v/v), and 5% (w/v) nonfat milk for 2 h. The incubation with primary antibody was done at 4°C overnight and then with secondary antibody at room temperature for 2 h. The Ab14 (dilution 1:2000) was used as primary antibody for PS1 and PST18 (dilution 1:2000) for PS2. The β-tubulin type III (dilution 1:4000) was used as an internal control. The secondary antibodies used were HRPO-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (1:4000 for Ab14 antiserum) and HRPO-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (1:4000 for PST18 antiserum and β-tubulin type III). The immunoreactive bands were visualized by ECL method (Amersham Biosciences, Hong Kong).

Densitometry and Statistical Analysis

Both northern hybridization and western blotting experiments were repeated three times (n = 6/group/experiment). The X-ray film exposures were documented by AlphaImager system consisting of 10 bit CCD camera (Alpha Innotech Corp, USA). The band intensities were measured by spot densitometry tool of AlphaEaseFC software (Alpha Innotech Corp, USA). For northern hybridization, the signal of the specific transcript was densitometrically estimated and for western blots, the signal intensity of the band of interest was measured after normalization with β-tubulin. The statistical difference was calculated using one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) followed by paired sample t-test for comparison between two selected groups having one variable. The P values < 0.05 were considered significant (95% confidence interval). Results represent the mean ± SEM of three data for each group.

Results

Effect of Age and Sex on PS1 Expression

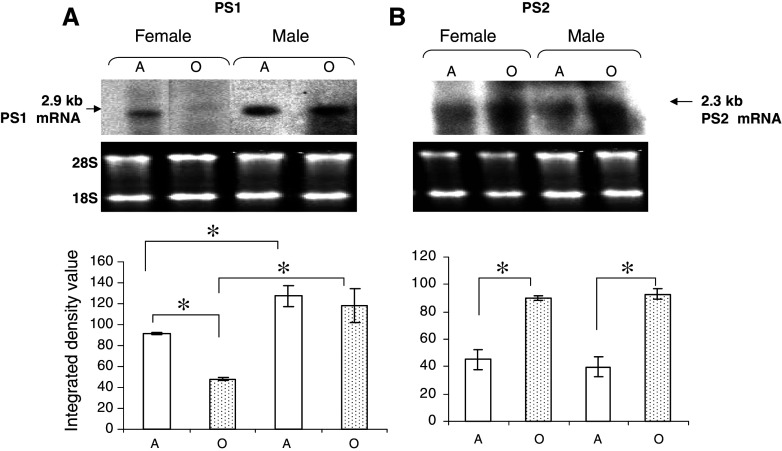

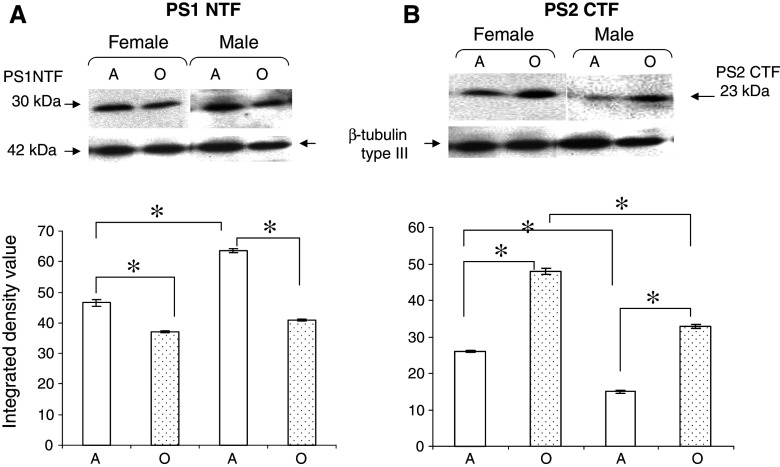

To know the effect of age, values from intact adult mice of both sexes were considered as 100%. The level of PS1 mRNA showed no significant change with age in male, but it decreased to 50% in old female as compared to adult (Fig. 1A). Western blot analysis revealed reduction in the level of PS1NTF in female (20%, P < 0.05) and male (36%, P < 0.05) mice of old age as compared to adult counterparts (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 1.

Effect of age and sex on PS1 and PS2 mRNA level: Northern hybridization analysis of (A) 2.9 kb PS1 and (B) 2.3 kb PS2 mRNA. Lower panel shows ethidium bromide picture of 20 μg total RNA fractionated on 1.2% agarose-formaldehyde gel. Histograms represent integrated density value (IDV) ± SEM (n = 6) of the band intensity quantified densitometrically using AlphaEase software. * denotes significant differences between adult and old age groups, and between female and male groups (P < 0.05). A—adult; O—Old age groups

Fig. 2.

Effect of age and sex on PS1NTF and PS2CTF: Western blot analysis using 50 μg membrane protein solubilized in lysis buffer and resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred onto PVDF membranes and (A) detected with Ab14 anti-PS1 NTF antiserum and (B) PST18 anti-PS2 CTF antiserum. Lower panel shows 42 kDa β-tubulin type III band. Histograms represent integrated density value (IDV) ± SEM (n = 6) of PS1NTF or PS2CTF/ β-tubulin type III band intensity ratio quantified using AlphaEase software. * denotes significant differences between adult and old age groups, and between female and male groups (P < 0.05). A—adult; O—Old age groups

To know the effect of sex, the values from intact male mice were considered as 100%. Northern analysis showed lower level of PS1 mRNA in adult (43%) and old (58%) female as compared with male mice of corresponding age (Fig. 1A). Western blot analysis revealed relatively lower level of PS1 protein (27%, P < 0.05) in adult female than male, but no significant effect of sex in old age (Fig. 2A).

Effect of Age and Sex on PS2 Expression

To know the effect of age, values from intact adult mice were considered as 100%. As compared to adult female and male, the level of PS2 mRNA increased twice in old age (Fig. 1B). Similarly, PS2 protein level increased remarkably in old by 85% (P < 0.05) in female and by 120% (P < 0.05) in male as compared to adult counterparts (Fig. 2B).

To know the effect of sex, values in males were considered 100% and compared with values in females of same age group. No significant difference was observed in the mRNA levels of female and male mice of both ages (Fig. 1B). However, PS2 protein level was higher in adult (72%, P < 0.05) and old (46%, P < 0.05) female as compared to male mice of corresponding ages (Fig. 2B).

Discussion

In the present study, comparison was done for PS1 and PS2 expression at mRNA and protein levels using the cerebral cortex of adult and old mice. Our results revealed age dependent decrease in PS1 but increase in PS2 expression. Although PS1 and PS2 are homologous proteins, their regulation differs with age, suggesting distinct roles of PS1 and PS2, as also reported by Hashimoto-Gotoh et al. (2003). The effect of age and sex on PS expression at mRNA and protein level showed a similar pattern in most groups.

Presenilin 1 expression was significantly lower in old age as compared to adult, which suggests a mechanism to downregulate PS1 dependent signaling pathway. The decrease in PS1 protein level in old female might result from decline in PS1 transcript level. However, in male mice, PS1 mRNA did not show any age dependent difference, though the protein level decreased in old. Such variations between mRNA and protein levels might arise due to differences in the rate of synthesis and stability of transcript as well as protein. Our findings are partially supported by an earlier observation that the steady state levels of PS1 and PS2 mRNA decline with age in human and murine brain (Lee et al. 1996). Age-related changes in the expression and localization of PS1 in monkey brain have also been reported by Kimura et al. (2001). They found increased localization of PS1 in nuclear regions than in other sub-cellular regions. These data suggest a diminished transportation of PS1 with advancing age, which results in increased accumulation of PS1 in endoplasmic reticulum associated with nuclear membrane. Since we used the protein preparation from post-nuclear fraction, it can be safely concluded that the age dependent decrease observed in present investigation results from a decline in the synthesis or stability of PS1 protein.

Presenilin 1 is the catalytic core of the γ-secretase enzyme, which cleaves many transmembrane proteins, and later these cleaved fragments are transported to the nucleus where they interact with the transcription machinery. This signaling pathway regulates the transcription of crucial genes which are implicated in neuronal survival and function. Thus the decline in PS1 might act as a mechanism to downregulate the associated transcription machinery and dependent functions. Kern et al. (2006) reported that APP processing by γ-secretase is reduced during aging due to progressively lower levels of two important protein constituents, namely PS1 and nicastrin. Earlier studies on PS1 expression in the developing brain and the impaired neuronal development in PS1 null mice suggested that factors involved in neuronal differentiation and survival influence the PS1 protein level (Ribaut-Barassin et al. 2003; Saura et al. 2004). Some of these factors (TGF-β, NGF, BDNF) are neurotrophic in nature and show age dependent expression (Silhot et al. 2005; Williams et al. 2007).

In contrast to PS1, the expression of PS2 shows a different pattern with aging. PS2 mRNA and protein levels are significantly higher in old mice of both sexes. Similar observation was reported by Lee et al. (1996) on the relative level of PS1 and PS2 mRNA in cerebral cortex from embryonic to adult stage. They found relatively higher level (5.5-fold) of PS1 mRNA than PS2 mRNA during embryonic stage. However, during postnatal development, the level of PS2 mRNA increased relative to PS1. These results suggest that differential regulation of PS1 and PS2 is not limited to early brain development. As reported earlier, ischemic and hypoxic conditions, which are high during aging and AD, upregulate both PS2 mRNA and protein levels. This upregulation is mediated by the change in binding affinity of transcription factors to PS2 promoter (Lukiw et al. 2001). Such stress and other age dependent changes act at transcriptional step to modulate the protein level. Further, cell culture studies have suggested a very prominent pro-apoptotic role of PS2 CTF (Da Costa et al. 2003). The expression of PS2 rises during stages when cellular apoptosis is required. Age dependent increase in apoptosis, as observed by others, may act as additive factor for increase in PS2 level (Nixon 2003). Age-related changes in synapse may also account for alteration in PS protein levels (Bertoni-Freddari et al. 1986; Scheibel et al. 1990).

Our results showed that PS1 and PS2 levels are differentially regulated with sex. PS1 expression is significantly higher at both transcript and protein levels in male than female mice. In contrast, PS2 protein level is higher in female than male mice in both age groups. Variations in transcriptional regulation and sex dependent factors might account for the abundance of two mRNAs. The sex-dependent difference in PS1 and PS2 expression may also be attributed to variations in the level of gonadal hormones. The decreased level of sex steroids, especially estrogen in postmenopausal women, makes them vulnerable to the onset of AD. Thus it is likely that the lower level of PS1 and higher level of PS2 in adult female than adult male might provide some insight into the differential prevalence of AD between two sexes.

Besides the regulation of PS during AD pathogenesis, there are other age-related factors which influence its expression. Recently we have reported the regulation of PS expression by sex steroids (Ghosh and Thakur, 2007 a, b). Our present study emphasizes the possible role of age and sex in the regulation of expression of PS, which interacts with many protein partners to mediate its functions. Thus PS proteins are tightly regulated, though they are less abundant in the brain. As their functions affect neuronal activities, the decline in PS1 expression with age may be a mechanism to regulate the downstream signal transduction pathway.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bart de Strooper (Belgium) for the generous gift of PS1 and PS2 cDNA constructs, Sam Gandy (Philadelphia, USA) for PS1 antiserum, and Helmut Jacobsen (Basel, Switzerland) for PS2 antiserum. This work was supported by a research fellowship from the University Grants commission to SG, and grants from the Department of Biotechnology (P-07/311/2004) and Department of Science and Technology (P-07/317/2005), Government of India, to MKT.

References

- Bazan NG, Lukiw WJ (2002) Cyclooxygenase-2 and presenilin-1 gene expression induced by interleukin-1 beta and amyloid beta 42 peptide is potentiated by hypoxia in primary human neural cells. J Biol Chem 277:30359–30367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoni-Freddari C, Giuli C, Pieri C, Paci D (1986) Age-related morphological rearrangements of synaptic junctions in the rat cerebellum and hippocampus. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 5:297–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capell A, Grunberg J, Pesold B, Diehlmann A, Citron M, Nixon R, Beyreuther K, Selkoe DJ, Haass C (1998) The proteolytic fragments of the Alzheimer’s disease-associated presenilin 1 form heterodimers and occurs as a 100–150 kDa molecular mass complex. J Biol Chem 273:3205–3211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counts SE, Lah JJ, Levey AI (2001) The regulation of presenilin 1 by nerve growth factor. J Neurochem 76:679–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N (1987) Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem 162:156–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa CA, Mattson MP, Ancolio K, Checler F (2003) The C-terminal fragment of presenilin-2 triggers p53-mediated staurosporine-induced apoptosis, a function independent of the presenilinase-derived N-terminal counterpart. J Biol Chem 278:12064–12069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Strooper B, Beullens M, Contreras B, Levesque L, Craessaerts K, Cordell B, Moechars D, Bollen M, Fraser P, St. George-Hyslop P, Leuven FV (1997) Phosphorylation, subcellular localization, and membrane orientation of the Alzhermer’s disease-associated presenilins. J Biol Chem 272:3590–3598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluhrer R, Friedlein A, Haass C, Walter J (2004) Phosphorylation of presenilin1 at the caspase recognition site regulates its proteolytic processing and the progression of apoptosis. J Biol Chem 279:1585–1593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Thakur MK (2007a) PS1 Expression is downregulated by gonadal steroids in adult mouse brain. Neurochem Res. doi:10.1007/s11064-007-9424-8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ghosh S, Thakur MK (2007b) PS2 protein expression is upregulated by sex steroids in the cerebral cortex of aging mice. Neurochem Res. doi:10.1016/j.neuint. 2007.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto-Gotoh T, Tsujimura A, Watanabe Y, Iwabe N, Miyata T, Tabira T (2003) A unifying model for functional difference and redundancy of presenilin-1 and -2 in cell apoptosis and differentiation. Gene 323:115–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashide S, Morikawa K, Okumura M, Kondo S, Ogata M, Murakami T, Yamashita A, Kanemoto S, Manabe T, Imaizumi K (2004) Identification of cis-acting element for alternative splicing of presenilin 2 exon 5 under hypoxic stress conditions. J Neurochem 91:1191–1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwatsubo T (2004). The γ-secretase complex: machinery for intramembrane proteolysis. Curr Opin Neurobiol 14:379–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern A, Roempp B, Prager K, Walter J, Behl C (2006) Down-regulation of endogenous amyloid precursor protein processing due to cellular aging. J Biol Chem 281:2405–2457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura N, Nakamura S-I, Honda T, Takashima A, Nakayama H, Ono F, Sakakibara I, Doi K, Kawamura S, Yoshikawa Y (2001) Age related changes in the localization of presenilin-1 in cynomolgus monkey brain. Brain Res 922:30–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs DM, Fausett HJ, Page KJ, Kim T-W, Mori RD (1996) Alzheimer associated presenilins 1 and 2: neuronal expression in brain and localization to intracellular membranes in mammalian cells. Nat Med 2:224–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MK, Slunt HH, Martin LJ, Thinakaran G, Kim G, Gandy SE, Seeger M, Koo E, Price DL, Sisodia SS (1996). Expression of presenilin 1 and 2 (PS1 and PS2) in human and murine tissues. J Neurosci 16:7513–7525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Lahad E, Wijsman EM, Nemens E, Anderson L, Goddard KAB, Weber JL, Bird TD, Schellenberg GD (1995) A familial Alzheimer’s disease locus on chromosome1. Science 269:970–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukiw WJ, Gordon WC, Rogaev EI, Thompson H, Bazan NG (2001) Presenilin-2 (PS2) expression up-regulation in a model of retinopathy of prematurity and pathoangiogenesis. Neuroreport 12:53–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey LK, Mah AL, Ford DL, Miller J, Liang J, Doong H, Monteiro MJ (2004) Overexpression of ubiquilin decreases ubiquitination and degradation of presenilin proteins. J Alzheimers Dis 6:79–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuda N, Ohkubo N, Tamatani M, Lee Y, Taniguchi M, Namikawa K, Kiyama H, Yamaguchi A, Sato N, Sakata K, Ogihara T, Vitek MP, Tohyama M (2001) Activated cAMP-response element-binding protein regulates neuronal expression of presenilin 1. J Biol Chem 276:9688–9698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon RA (2003) The calpains in aging and age related diseases. Aging Res Rev 2:407–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks AL, Curtis D (2007) Presenilin diversifies its portfolio. Trends Genet 23:140–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren RF, Lah JJ, Diehlmann A, Kim ES, Hawver DB, Levey AI, Beyreuther K, Flanders KC (1999) Differential effects of transforming growth factor-beta (s) and glial-cell line derived neurotrophic factor on gene expression of presenilin-1 in human post-mitotic neurons and astrocytes. Neuroscience 93:1041–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renbaum P, Beeri R, Gabai E, Amiel M, Gal M, Ehrengruber MU, Levy-Lahad E (2003) Egr-1 upregulates the Alzheiemr’s disease presenilin-2 gene in neuronal cells. Gene 318:113–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribaut-Barassin C, Dupont JL, Haeberle AM, Bombarde G, Huber G, Moussaoui S, Mariani J, Bailly Y (2003) Alzheimer’s disease proteins in cerebellar and hippocampal synapses during postnatal development and aging of the rat. Neuroscience 120:405–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh J, Kuroda Y (1999) Constitutive and cytokine—regulated expression of presenilin-1 and presenilin-2 genes in human neural cell lines. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 25:492–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saura CA, Choi S, Beglopoulos V, Malkani S, Zhang D, Rao BSS, Chattarji S, Kelleher RL, Kandel ER, Duff K, Kirkwood A, Shen J (2004) Loss of presenilin function causes impairments of memory and synaptic plasticity followed by age-dependent neurodegeneration. Neuron 42:23–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheibel A, Conrad T, Perdue S, Tomiyasu U, Wechsler A (1990) A quantitative study of dendrite complexity in selected areas of the human cerebral cortex. Brain Cognition 12:85–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrington R, Rogaev EI, Liang Y, Rogaeva EA, Levesque G, Ikeda M, Chi H, Lin C, Li G, Holman K, Tsuda T, Mar L, Foncin JF, Bruni AC, Montesi MP, Sorbi S, Rainero I, Pinessi L, Nee L, Chumakov I, Pollen D, Brookes A, Sanseau P, Polinsky RJ, Wasco W, Da Silva HAR, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Tanzi RE, Roses AD, Fraser PE, Rommens JM, St. George-Hyslop PH (1995) Cloning of a gene bearing missense mutations in early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 375:754–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silhot M, Bonnichon V, Rage F, Tapia-Arancibia L (2005) Age related changes in brain derived neurotrophic factor and tyrosine kinase receptor isoforms in the hippocampus and hypothalamus in male rats. Neuroscience 132:613–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PK, Krohn RI, Hermanson GT, Mallia AK, Gartner FH, Provenzano MD, Fujimoto EK, Goeke NM, Olson BJ, Klenk DC (1985). Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal Biochem 150:76–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thinakaran G, Borchelt DR, Lee MK, Slunt HH, Spitzer L, Kim G, Ratovitski T, Davenport F, Nordstedt C, Seeger M, Hardy J, Levey AI, Gandy S, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Price DL, Sisodia SS (1996). Endoproteolysis of presenilin 1 and accumulation of processed derivatives in vivo. Neuron 17:181–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuhiro S, Tomita T, Iwata H, Kosaka T, Saido TC, Maruyama K, Iwatsubo T (1998) The presenilin 1 mutation (M146 V) linked to familial Alzheimer disease attenuates the neuronal differentiation of NTera 2 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 244:751–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter J, Schindzielorz A, Grunberg J, Haass C (1999). Phosphorylation of presenilin 2 regulates its cleavage by caspases and retards progression of apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:1391–1396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B, Granholm AC, Sambamurti K (2007) Age dependent loss of NGF signaling in the rat basal forebrain is due to disrupted MAPK activation. Neurosci Lett 413:110–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]