Abstract

(1) A new human glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) cell line, WJ1, was established from the tissue derived from a 29-year-old patient diagnosed with a grade IV GBM. (2) The WJ1 cell line has been subcultured for more than 80 passages in standard culture media without feeder layer or collagen coatings. (3) GBM cells grow in vitro with distinct morphological appearance. Ultrastructural examination revealed large irregular nuclei and pseudo-inclusion bodies in nuclei. The cytoplasm contained numerous immature organelles and a few glia filaments. Growth kinetic studies demonstrated an approximate population doubling time of 60 h and a colony forming efficiency of 4.04%. The karyotype of the cells was hyperdiploid, with a large subpopulation of polyploid cells. Drug sensitivities of DDP, VP-16, tanshinone IIA of this cell line were assayed. They showed a dose- and time-dependent growth inhibition effect on the cells. (4) Orthotopic transplantation of GBM cells into athymic nude mice induced the formation of solid tumor masses about 6 weeks. The cells obtained from mouse tumor masses when cultivated in vitro had the same morphology and ultrastructure as those of the initial cultures. (5) This cell line may provide a useful model in vitro and in vivo in the cellular and molecular studies as well as in testing novel therapies for human glioblastoma multiforme.

Keywords: Glioblastoma multiforme, Brain neoplasm, Human glioma cell lines

Introduction

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common primary malignant neoplasm of the adult brain (Jost et al. 2007), which is highly invasive and virtually incurable. Despite recent advances in the understanding of the pathophysiology of this neoplasm and over several decades of technological advances in neurosurgery, radiation therapy, and clinical trials of conventional and novel therapeutics, little progress has been made in treatment for GBMs (Maher et al. 2001), the treatment outcomes are poor (Jost et al. 2007). The limitations of current treatments make the development of new therapies imperative. Such advances depend, in part, on animal models that accurately mimic human glioblastomas (Jost et al. 2007; Gutmann et al. 2003).

Permanent glioma cell lines are invaluable tools in understanding the biology of glioblastomas (Di Tomaso et al. 2000). Besides, cultured cells still can be serially transplanted into nude mice supplying a trustworthy model for the study of behavior of human tumors, such as metabolism, relapse, drug sensitivity, and resistance (Horiguchi et al. 1998).

Mouse models, in turn, increased our understanding of brain tumor initiation, formation, progression, and metastasis, providing an experimental system to discover novel therapeutic targets and test various therapeutic agents (Fomchenko et al. 2006). Recently, remarkable strides have been made in the generation of mouse models of the diffuse gliomas that provide unparalleled opportunities for advancing our knowledge of the etiology, maintenance, and treatment of this lethal class of tumors (Begemann et al. 2002; Holland et al. 2001). Animal models are important not only for the testing of novel therapeutics but also as a means to understand the molecular explanations for treatment success and failure in humans (Lyustikman and Lassman 2006). Therefore, The high rate of engraftment, the similarity to the high-grade malignant glioma of origin, and the rapid, locally invasive growth of these tumors should make murine model useful in testing novel therapies for human malignant gliomas (Smilowitz et al. 2007). However, brain tumor cells, unlike other cell types, are not easily established in tissue culture, although some success has been reported in establishing cell lines from primary ex-plants of malignant gliomas (Selvakumaran et al. 2003), the useful cell lines and animal models of GBM are limited.

To enrich the bank of cell lines and animal models of GBM, a new human GBM cell line (WJ1) was established, and its basic information of morphologic and biological characteristics and tumorigenicity in vivo were described in this experimental study, which may provide a useful model in vitro and in vivo in the cellular and molecular studies as well as in testing novel therapies for human glioblastoma multiforme.

Material and Methods

Tumor Tissue

The tumor tissue was kindly provided by the Department of Neurosurgery, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (China), shortly after surgery of a 29-year-old male patient diagnosed with glioblastoma multiforme of the right temporal parietal lobe. Histological examination revealed a grade IV astrocytoma according to the WHO classification, and expressing GFAP immunohistocheomically.

Tissue Culture

The tumor was washed with Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS; Sigma) and minced to 1–2 mm fragments with scissors. The fragments were dissociated by mechanical means and placed into 25 cm2 tissue culture flasks with DMEM/F12 supplemented 10% inactivated fetal calf serum (FBS) containing 100 IU/ml penicillin G and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. The culture was incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. When the primary culture reached confluence the cells were transferred by treatment with 0.05% trypsin and 0.02% EDTA, and maintained in the same medium. Subsequently, the cultures were serially transferred in the same procedure once or twice a week. Large quantities of GBM cells were routinely frozen at various passage levels in medium plus 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, v/v) for later use.

Morphologic and Ultrastructural Studies

The morphology of cultured GBM cells were observed with phase contrast microscope. At passage 30, the cells were trypsinized and washed in HBSS, fixed in 0.5% glutaraldehyde (pH 7.2) at 4°C for ultrastructural study. After three rinses in HBSS, the cell pellets were postfixed for 2 h at 4°C in 3% glutaraldehyde. Subsequently, the pellets were rinsed in HBSS for 5 mins at 4°C, dehydrated with a graded series of ethanol, and embedded in Epon 812. Thin sections were cut with a glass knife and stainde with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Semithin sections were stained with toluidine blue and examined with a transmission electron microscope.

Doubling Time and Colony-forming Efficiency

Cultures of GBM cells were collected after the 30th passage for determination of growth curves by the tetrazolium (MTT) assay. Semiconfluent cultures were trypsinized and cells were counted with a hemocytometer. Cells (2 × 103 /well) were plated in 100 μl of medium/well in 96-well plates. After incubation overnight, 5 wells were determined, 20 μl of 5 mg/ml MTT (pH 4.7) was added to each well and cultivated for another 4 h, the supernatant was removed, 100 μl/well DMSO was added and shaken for 15 min. The absorbance at 570 nm was measured with microplate reader (Bio-Rad), using wells without cells as blanks. All experiments were performed in triplicate for 9 days. Population doubling time was determined from the linear phase of the growth curve.

To determine colony-forming efficiency (CFE), 500 cells were plated into each well of 6-well plates. Fresh medium was added for 12 days, after then the discrete colonies were fixed, stained with crystal violet, and counted. CFE was determined by using the following formula: CFE = Number of colonies counted/number of cells inoculated × 100.

Karyotypic Analysis

Confluent monolayer cells were treated with clochicine (0.05 mg/ml) for 4 h and then dispersed with 0.5% trypsin and 0.02 EDTA. After having been washed with a 0.075 mol/L KCL solution for 30 min at 37°C. The cells were then fixed in a mixture of acetic acide and methanol (1:3, v/v). The cell suspension was dropped on a glass slide. Ten metaphases with approximately 300 chromosomes were imaged and analyzed.

Drug Sensitivity (MTT assay)

The drug sensitivity of the cells was determined by the MTT assay (Selvakumaran et al. 2003). Cells (2 × 103/well) in 100 μl of medium were plated in 96-well plates. After incubation overnight, various concentrations DDP (0.3125, 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10 mg/l), VP-16 (5, 10, 20, 40, 80, 160 mg/l), tanshinone IIA (6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200 ng/l) were added respectively; 5 wells were included in each concentration of each drug. After treatment with drugs for 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 days, 20 μl/well of MTT (5 mg/ml, pH 4.7) was added and cultivated for another 4 h, the supernatant was removed, 100 μl DMSO was added into each well and shaken for 15 min, absorbance at 570 nm was measured with microplate reader, using wells without cells as blanks. All experiments were performed in triplicate. The effect of drug on the proliferation of this cell line was expressed as the percentage cell viability, using the following formula: percentage cell viability = A570 of treated cells/A570 of control cells × 100%.

Tumorigenicity of Orthotopic Transplantation

Five 6-week-old male nude mice (Experimental Animal Center, Sichuan University) were xenotransplanted with this GBM cell line, briefly, the mice were aneathetized with chloral hydrate and stereotactically implanted with 1 × 105 of adherent monolaye cells at passage 33 suspended in 6 μl PBS (pH 7.2) in the frontal cortex. The injection coordinates were 3 mm to the right of the midline, 2 mm anterior to the coronal suture and 3 mm deep (Singh et al. 2003; Singh et al. 2004). The experiment was repeated once with identical situations. All procedures were carried out in accordance with the guidelines of Animal Care proposed by Sichuan University.

After 10–12 weeks, the implanted mice were killed; tumorigenicity was determined by gross and pathological examination conventionally.

Immunohistochemical Study

Tumor samples from mice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. GFAP and nestin protein expression were detected immunohitochemically with SP kit (Zymed Laboratories, USA), briefly, tissue sections were deparafnized and rehydrated through graded alcohols. Antigen retrieval was performed by microwaveoven heating in 0.1 mM citrate buffer (pH 6). Then, endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% H2O2, and after treatment with normal goat serum, the tissue sections were incubated with GFAP or nestin rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Zymed Laboratories, USA), respectively, at a dilution of 1:100, overnight at 4°C, with biotylated second antibody 20 min, and with streptavidin/peroxidase 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the sections were subjected to color reaction with 0.02% 3,3 diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride containing 0.005% H2O2 in PBS (pH 7.4), and were counterstained with hematoxylin lightly. GFAP and nestin protein expression were determined by the intensity of GFAP and nestin staining.

Subculture of GBM Cells derived from Mice

Tumor cells derived from mice were subcultivated in vitro as described above for the initial cells.

Morphologic and Ultrastructural Studies of Subcultivated Mouse Tumor Cells

The morphology and ultrastructure of subcultivated mouse tumor cells were examined with phase contrast microscope and transmission electron microscope as described for the initial cells above.

Results

Morphologic Characterization

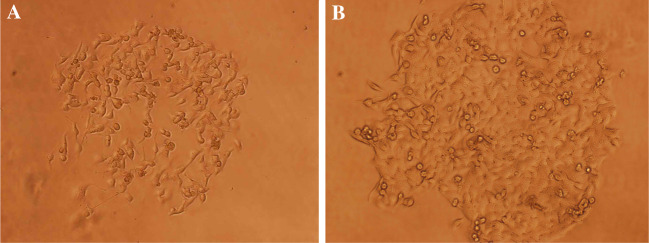

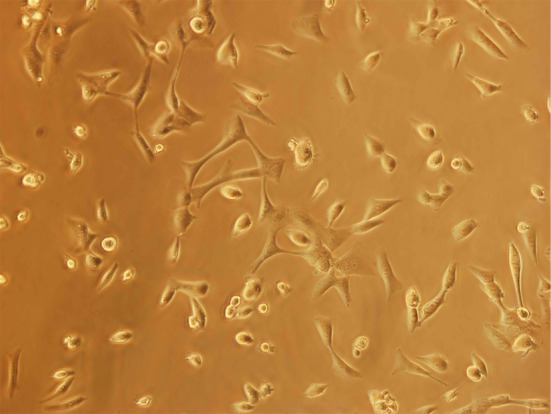

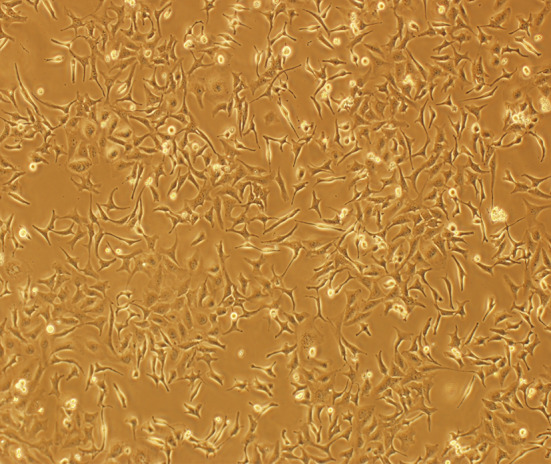

The cells were adherent and tend to form monolayers. Many morphologically distinct populations were found, such as small rounded cells and spindle, dendritic-like cells. Such heterogeneous cell types were observed since the first passage in culture. Morphology of cells remained unchanged even after 30 passages (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Morphology of GBM cell line: passage 30. (×200)

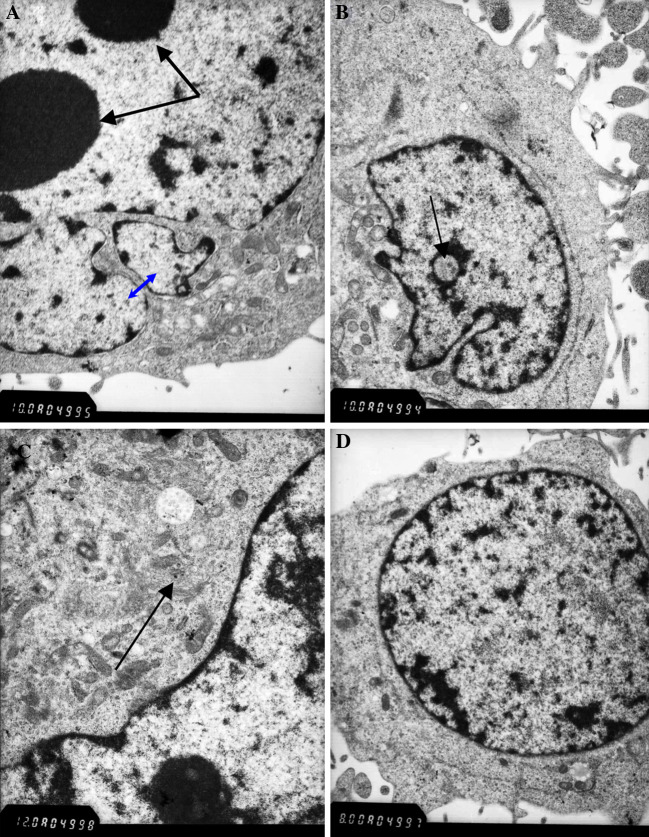

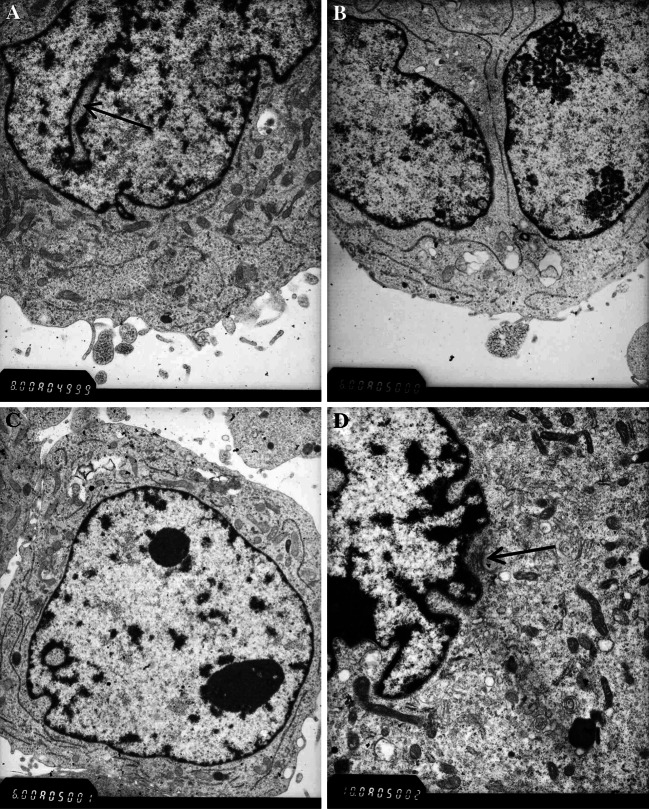

Ultrastructural examination by electron microscopy revealed large irregular nuclei (Fig. 2A) and pseudo-inclusion GBM cells (Fig 2B). The cytoplasm of the cells contained numerous immature organelles and a few glia filaments (Fig. 2C). The cell line consisted of poorly differentiated cells (Fig 2D) showing high nuclear–cytoplasmic ratio and inconspicuous cytoplasmic filaments.

Fig. 2.

Electron micrograph of the cell line showing cytological pleomorphism: (A) Pseudo-inclusion body (black arrow) × 10,000; (B) Large irregular nuclei (blue arrow) and two prominent nucleoli (black arrow) × 10,000; (C) Poorly differentiated cell × 8,000; (D) Glia filaments (black arrow) × 12000

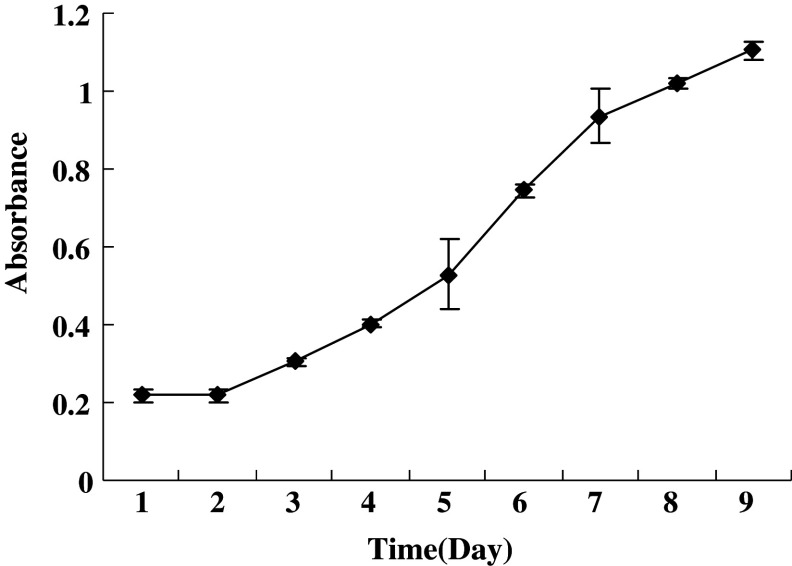

Doubling Time and CFE

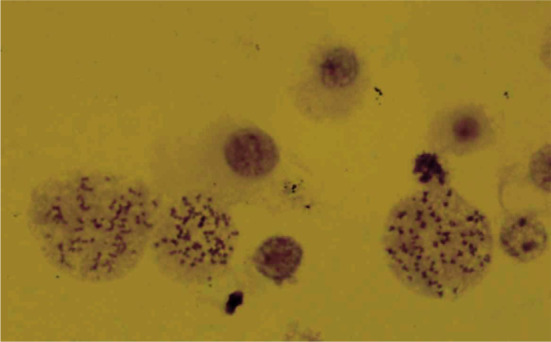

Figure 3 shows the population doubling time that was obtained from the growth curves. The analyzed cells were within the 28–32 passages. The population doubling time of GBM cells was about 60 h. CFE was determined with the same preparations that were used to establish the growth curves. The colonies were counted 12 days after plating. CFE was calculated to be 4.04%. Various sizes of colonies were observed (Fig. 4A, B).

Fig. 3.

Growth curve of GBM cell line

Fig. 4.

Colony formation of GBM cell line. (A) At day 5(×100); (B) At day 10(×100)

Karyotypic Analysis

The cell line at passage 15 was hyperdipoid, with a large subpopulation of polyploid cells (Fig. 5). Chromosome counts for hyperdiploid metaphases fell into a modal range of 50-80 chromosomes per cell.

Fig. 5.

Karyotype of GBM cell line,showing the hyperdipoid and polyploid cells

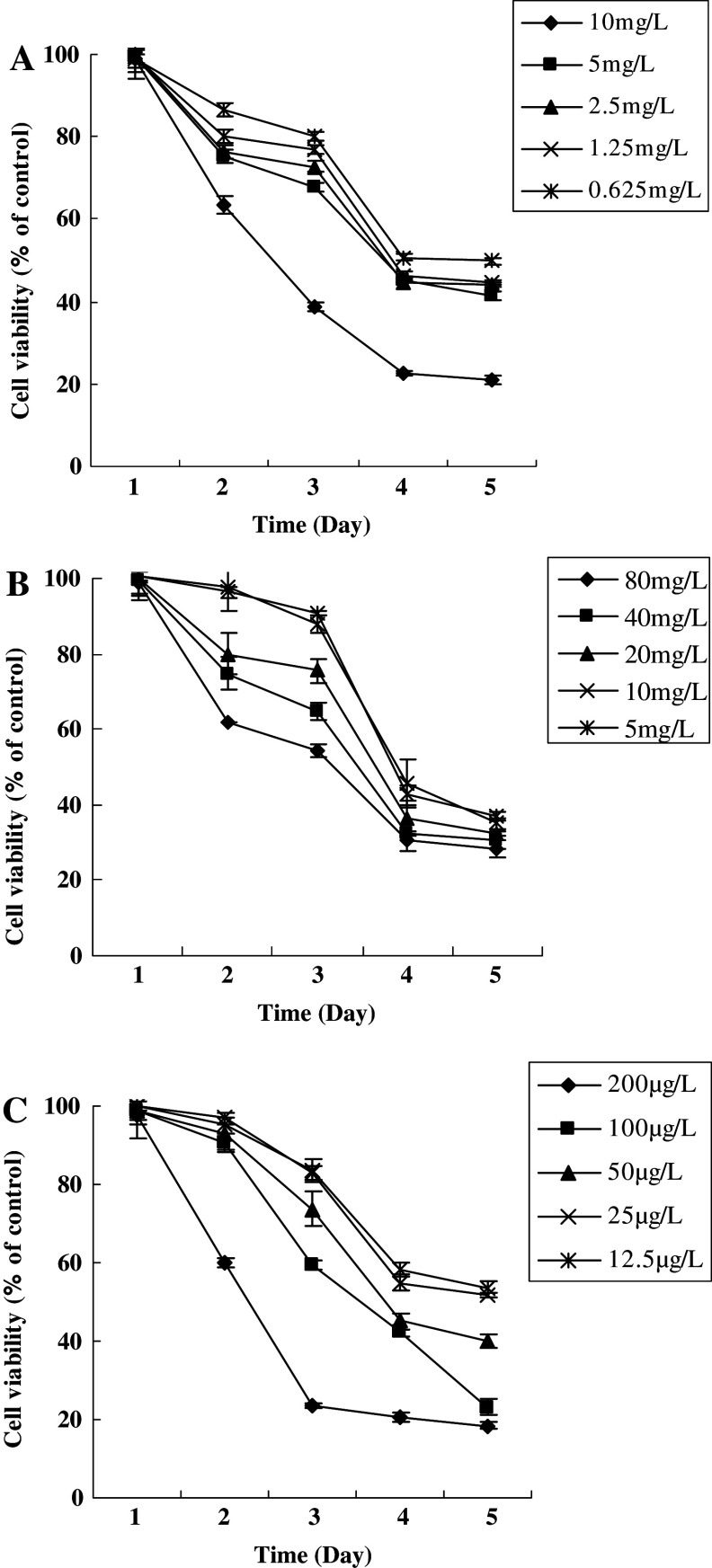

Drug Sensitivity

The growth inhibition effect of DDP, VP-16, tanshinone IIA on GBM cells was assayed. It showed a dose- and time-dependent inhibitory effect on the cell growth (P < 0.05). IC50 of DDP, VP-16, tanshinone IIA was 7.5 mg/l, 85 mg/l and 0.12 mg/l, respectively (P < 0.01). This cell line was hypersensitive to tanshinone IIA. The results of drug sensitivity of this cell line are shown in Fig. 6A–C.

Fig. 6.

Growth inhibition of DDP, VP-16 and tanshinone IIA on GBM cell line. (A) A dose- and time-dependent growth inhibition of DDP against GBM cells (P < 0.05); (B) A dose- and time-dependent growth inhibition of VP-16 against GBM cells (P < 0.05); (C) A dose- and time-dependent growth inhibition of tanshinone IIA against GBM cells (P < 0.05). Results are mean values ± SD of independent experiments performed in triplicate

Tumorigenicity

To examine the tumorigenicity of the GBM cells, 1 × 105 of adherent monolaye cells at passage 33 suspended in 6 μl PBS (pH 7.2) were inoculated into the mice orthotopicly. 5 of 5 inoculated mice developed tumor (100%) after 10–12 weeks (Fig. 7B).

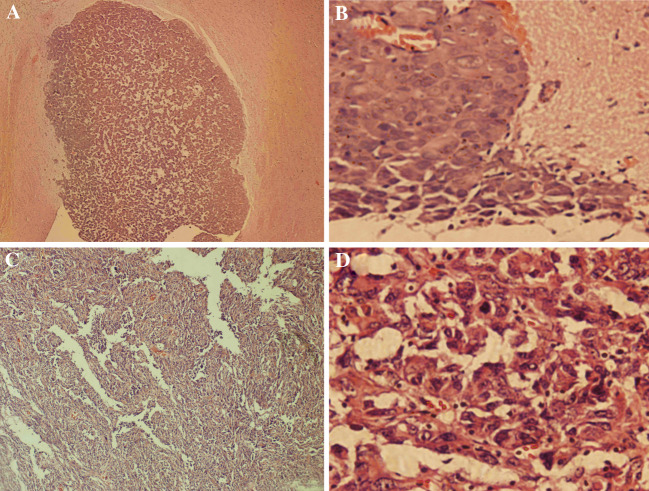

Fig. 7.

Histopathology of xenograft tumor and human GBM. (A) Xenograft tumor (HE × 100); (B) Xenograft tumor (HE × 400); (C) Human GBM (HE × 100); (D) Human GBM (HE × 400)

Pathological Characteristics

Heterogeneity of xenograft tumor was observed under microscopy (Fig. 7A, B), which is the same as that of human primary GBM (Fig. 7C, D). In addition, frequent local invasion and angiogenesis were found (Fig. 7B).

GFAP and Nestin expression

Immunohistochemical study showed that xenograft tumor cells recapitulated the phenotype of human primary GBM, expressing GFAP and Nestin (data not shown).

Morphology and Ultrastructure of Subcultivated Mouse Tumor Cells

Cells derived from tumor mass developed in nude mice were subcultivated in vitro and showed capacity of full growth. The morphology and ultrastructure of the cells cultivated after heterotransplatation in mouse did not differ from that of the initial culture (Fig. 8). Many morphologically distinct populations were observed: majority of the cells were flat polygonal, small rounded cells and spindle, dendritic-like cells were also observed.

Fig. 8.

The morphology of the GBM cells subcultivated from mouse xenograft tumor (×100)

By electron microscopy study, subcultivated xenograft tumor cells were of pleomorphism, including polynucleated giant tumor cells and poorly differentiated tumor cells mainly, irregular large nuclei and pseudo-inclusion body were also observed (Fig. 9A–D).

Fig. 9.

Ultrastructure of the GBM cells subcultivated from mouse xenograft tumor, showing cytological pleomorphism: (A) Pseudo-inclusion body (black arrow) × 8,000; (B) Polynucleation tumor giant cell × 6,000; (C) poorly differentiated cell × 6,000; (D) glia filaments (black arrow) × 10,000

Discussion

Glioblastoma multiforme is the most malignant of the primary brain tumours and is almost always fatal. The treatment strategies for this disease have not changed appreciably for many years and most are based on a limited understanding of the biology of the disease (Holland 2001). As the treatment of this malignant neoplasm remains challenging, the prognosis of patients with glioblastoma is poor (Jost et al. 2007; Surawicz et al. 1998; Davis et al. 1998). Although recent modelling experiments in mice are helping to delineate the molecular aetiology of this disease and are providing systems to identify and test novel and rational therapeutic strategies (Holland 2001), the limitations of current treatments calls for the development of new therapeutic modalities. The successful therapeutic progress depends, in part, on panels of in vitro cell lines and human xenograft models in predicting the clinical trial performance of anticancer agents (Voskoglou-Nomikos et al. 2003), therefore, the cell lines and human xenograft models that accurately mimic human glioblastomas are needed (Jost et al. 2007; Gutmann et al. 2003).

Permanent glioma cell lines are invaluable tools in understanding the biology of glioblastomas (Di Tomaso et al. 2000; Bakir et al. 1998). In this experimentl study, a new human glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) cell line, WJ1, was established from the tissue derived from a 29-year-old patient diagnosed with a grade IV GBM according to the WHO classification. Until now, this cell line was maintained for more than 80 passages, and kept growth potential well.

Cells with variable morphological features, such as, small rounded cells and spindle, dendritic-like cells were observed, the main two types of cells described in a former study using phase contrast microscopy of culture monolayer (Grippo et al. 2001). Ultrastructural examination revealed cells with a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, multiple nucleoli, pseudo-inclusion body, numerous immature organelles, a few glia filaments and poorly differentiated cells. The nucleolar hypertrophy and numerous organelles were presumably associated with an increased energy metabolism and linked to the proliferative activity of the cells (Bacciocchi et al. 1992).

Although the analysed cells for population doubling time and colony-forming efficiency (CFE) were within the 28–32 passages, lower than those (74–100 passages) of NG-97 cell line reported (Grippo et al. 2001), the population doubling time (62 h) is shorter than that of NG-97 (72 h), and higher CFE (4.04%) than NG-97 (1%).This fact could indicate a perfect adaptation of cells to the culture conditions (Grippo et al. 2001).

Karyotypic analysis showed that the GBM cell line established in this experiment contained a mixed population of hyperdiploid and polyploid cells, which indicated the phenotypic and genotypic heterogeneity of this cell line (Bakir et al. 1998). The heterogeneity was also observed in xenograft tumor tissues and subcultivated mouse tumor cells.

The drug sentivity of this cell line was the same as that of human glioma cell line U251 reported (Wang et al. 2007), it is indicated that this cell line might be useful in screenning the anticancer agents for GBMs.

Tumorigenicity heterotransplanted in nude mice was generally accepted as a criterion of malignancy. Compared with other establishment of glioma cell line (Grippo et al. 2001), 1 × 105 of adherent monolaye GBM cells were inoculated into mouse in situ rather than 2 × 106 cells were inoculated subcutaneously into the flank of nude mice (Grippo et al. 2001), all (5/5) mice developed tumor masses in the brain. Combined with the findings of a shorter population doubling time and higher colony-forming efficiency in vitro, and frequent local invasion and angiogenesis in vivo, it was indicated that this established GBM cell line exhibited more malignant potential.

In summary, a new human glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) cell line, WJ1, was established in this experiment, its drug sentivity is the same as that of the current available glioma cell line (Wang et al. 2007); the histopathological characterestics of xenograft tumor is similar to human primary GBM; GFAP and Nestin expressions were detected in xenograft tumor cells; The morphology and ultrastructure of subcultivated mouse tumor cells did not differ from those of the initial culture cells. All of these features suggested that WJ1 cell line could accurately mimic human glioblastomas in vitro and in vivo, it would be useful in the cellular and molecular studies as well as in testing novel therapies for human glioblastoma multiforme in vitro and in vivo.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China; Grant Number: 30471779.

Reference

- Bacciocchi G, Gibelli N, Zibera C, Pedrazolli P, Bergamaschi G, Polver PDP, Danova M, Mazzini G, Palomba L, Tupler R, Cuna GRD (1992) Establishment and characterization of two cell lines derived from human glioblastoma multiforme. Anticancer Res 12:853–862 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakir A, Gezen F, Yildiz O, Ayhan A, Kahraman S, Kruse CA, Varella-Garcia M, Yildiz F, Kubar A (1998) Establishment and characterization of a human glioblastoma multiforme cell line. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 103:46–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begemann M, Fuller GN, Holland EC (2002) Genetic modeling of glioma formation in mice. Brain Pathol 12:117–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis FG, Freels S, Grutsch J, Barlas S, Brem S (1998) Survival rates in patients with primary malignant brain tumors stratified by patient age and tumor histological type: An analysis based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data, 1973-1991. J Neurosurg 88:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Tomaso E, Pang JCS, Ng HK, Lam PYP, Tian XX, Suen KW, Hui ABY, Hjelm N M (2000) Establishment and characterization of a human cell line from paedriatic cerebellar glioblastoma multiform. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 26:22–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomchenko EI, Holland EC (2006) Mouse models of brain tumors and their applications in preclinical trials. Clin Cancer Res 12:5288–5297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippo MC, Penteado PF, Carelli EF, Cruz-Holfing MA, Verinaud L (2001) Establishment and partial characterization of a continuous human malignant glioma cell line: NG97. Cell Mol Neurobiol 21:421–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann DH, Baker SJ, Giovannini M, Garbow J, Weiss W (2003) Mouse models of human cancer consortium symposium on nervous system tumors. Cancer Res 63:3001–3004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland EC (2001) Gliomagenesis: genetic alterations and mouse models. Nat Rev Genet 2:120–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiguchi H, Matsui M, Ahtsubo R, Ogata T, Kaneko M, Fujiwara M, Kamma H (1998) Establishment and characterization of a typical primitive neuroectodermal tumor cell line. In vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 34:439–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost SC, Wanebo JE, Song SK, Chicoine MR, Rich KM, Woolsey TA, Lewis JS, Mach RH, Xu J, Garbow JR (2007) In vivo imaging in a murine model of glioblastoma. Neurosurgery 60:360–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyustikman Y, Lassman AB (2006) Glioma oncogenesis and animal models of glioma formation. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 20:1193–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher EA, Furnari FB, Bachoo RM, Rowitch DH, Louis DN, Cavenee WK, De Pinho RA (2001) Malignant glioma:genetics and biology of a grave matter. Genes Dev 15:1311–1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvakumaran M, Pisarcik DA, Bao R, Yeung AT, Hamilton TC (2003) Enhanced cisplatin cytotoxicity by disturbing the nucleotide excision repair pathway in ovarian cancer cell lines. Cancer Res 63:1311–1316 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, Bone VE, Hawkins CH, Squire J, Dirks PB (2003). Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res 63:5821–5828 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, Squire JA, TakuichiroHide BA, Henkelman RM, Cusimano MD, Dirks PB (2004) Identification of human brain tumors initiating cells. Nature 432:396–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smilowitz HM, Weissenberger J, Weis J, Brown JD, O’Neill RJ, Laissue JA (2007) Orthotopic transplantation of v-src-expressing glioma cell lines into immunocompetent mice: establishment of a new transplantable in vivo model for malignant glioma. J Neurosurg 106:652–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surawicz TS, Davis F, Freels S, Laws ER Jr, Menck HR (1998) Brain tumor survival: results from the National Cancer Data Base. J Neurooncol 40:151–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voskoglou-Nomikos T, Pater JL, Seymour L (2003) Clinical predictive value of the in vitro cell line, human xenograft, and mouse allograft preclinical cancer models. Clin Cancer Res 9:4227–4239 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Wang XJ, Jiang S, Yuan SL, Lin P, Zhang J, Lu YR, Wang Q, Xiong ZJ, Wu YY, Ren JJ, Yong HL (2007) rowth inhibition and induction of apoptosis and differentiation of tanshinone IIA in human glioma cells. J Neuro-oncol 82:11–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]