Abstract

Cell wall-anchored surface proteins of gram-positive pathogens play important roles during the establishment of many infectious diseases, but the contributions of surface proteins to the pathogenesis of anthrax have not yet been revealed. Cell wall anchoring in Staphylococcus aureus occurs by a transpeptidation mechanism requiring surface proteins with C-terminal sorting signals as well as sortase enzymes. The genome sequence of Bacillus anthracis encodes three sortase genes and eleven surface proteins with different types of cell wall sorting signals. Purified B. anthracis sortase A cleaved peptides encompassing LPXTG motif-type sorting signals between the threonine (T) and the glycine (G) residues in vitro. Sortase A activity could be inhibited by thiol-reactive reagents, similar to staphylococcal sortases. B. anthracis parent strain Sterne 34F2, but not variants lacking the srtA gene, anchored the collagen-binding MSCRAMM (microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules) BasC (BA5258/BAS4884) to the bacterial cell wall. These results suggest that B. anthracis SrtA anchors surface proteins bearing LPXTG motif sorting signals to the cell wall envelope of vegetative bacilli.

Sortase enzymes catalyze transpeptidation reactions on the bacterial surface, utilizing protein precursors with C-terminal sorting signals as substrates (60). Staphylococcus aureus sortase A (SrtA), the prototypic transpeptidase of this class of enzyme (31, 32), cleaves LPXTG motif-type sorting signals between the threonine (T) and the glycine (G) residues to generate an acyl enzyme intermediate (30, 38, 58). Nucleophilic attack of the amino group of cell wall crossbridges resolves the acyl enzyme (62), forming an amide bond between the carboxyl group of the C-terminal threonine of surface proteins and the cell wall crossbridge of lipid II precursor molecules (45, 61). The product of this reaction, surface protein linked to lipid II, is then incorporated into the cell wall envelope via the transpeptidation and transglycosylation reactions of peptidoglycan biosynthesis (39, 51, 57). Twenty different surface proteins with LPXTG motif-type sorting signals have been identified in the staphylococcal genome sequence (34), and deletion of the srtA gene abolishes the cell wall anchoring and surface display of all sortase A substrates (31). As a result, staphylococcal srtA mutants display significant defects in the pathogenesis of murine organ abscesses, infectious arthritis, or endocarditis (25, 26, 31, 66).

The genomes of most gram-positive bacteria encode two or more sortase enzymes, which fulfill different functions (12, 42). For example, S. aureus sortase B is involved in anchoring IsdC (iron-regulated surface determinant C), a polypeptide with an NPQTN motif sorting signal, to the cell wall envelope (29, 33, 35). Streptococcus pyogenes sortases A and B both anchor surface proteins with LPXTG motif sequences to the envelope. These two sortases appear to recognize unique surface protein substrates using the LPXTG motif as well as other features of cell wall sorting signals (2). Streptococcal SrtC2 recognizes surface protein substrates with QVPTGV motif sorting signals, consistent with the view that different sortases recognize unique sets of substrates (1).

Perhaps the most astonishing sortase-catalyzed reaction is the assembly of pili on the surface of corynebacteria, actinomycetales, enterococci, group B streptococci, and pneumococci (64, 72). For example, corynebacterial sortases cleave precursor proteins in a manner that leads to the assembly of pili, high-molecular-weight polymerization products several microns long on the bacterial surface (65). Two domains of pilus surface proteins, the sorting signal and the pilin motif, are required for this reaction, which occurs in a sortase-specific manner. This results in the assembly of different types of pili by dedicated pairs of sortase enzymes and pilin subunit proteins (59, 65).

The 5.2-Mb genome of B. anthracis strain Ames, a fully virulent isolate, and those of its two virulence plasmids, pXO1 and pXO2, have been sequenced (40, 41, 49). Analysis of the genome sequence identified nine predicted surface protein genes encoding sorting signals with LPXTG motif sequences and three sortase genes (49). One of these genes, BA0688 (srtA), displays striking similarity to the srtA gene of S. aureus, whereas BA4783 (srtB) more closely resembles S. aureus srtB. A third gene, BA5069 (srtC), is homologous to sortase genes in other bacilli (B. cereus, B. halodurans, and B. subtilis) but is not found in staphylococci, listeriae, or corynebacteria (12).

We wondered whether B. anthracis surface proteins are anchored to the cell wall envelope by sortases in a manner similar to that observed for staphylococci, streptococci, and listeriae (2-5, 14, 31). If so, analysis of the phenotypic defects of sortase mutants during animal infections may reveal the relative contribution of all of these surface molecules to the pathogenesis of anthrax disease. Herein, we achieved a first step towards this goal by reporting the requirement of the srtA gene for the cell wall anchoring of BasC, an LPXTG motif-type surface protein (71). Furthermore, purified SrtA catalyzed a sortase A-type cleavage reaction with LPETG and LPATG peptides, consistent with the notion that B. anthracis srtA is responsible for the cell wall anchoring of surface proteins with an LPXTG motif.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are summarized in Table 1. All cultures of bacilli were grown overnight in Luria broth with 0.5% glucose at 30°C and, after dilution, were incubated in fresh medium at 37°C. Antibiotics were added to cultures for plasmid selection as follows: 100 μg/ml ampicillin (E. coli), 5 μg/ml erythromycin (B. anthracis), and 10 μg/ml chloramphenicol (B. anthracis). B. anthracis Sterne 34F2 (56) was used as a parent strain in this study.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and phages used in this study

| Strain plasmid, or phage | Property | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli XL-1 Blue | Expression of srtAΔN | 8 |

| E. coli DH5α | Plasmid transformation | 21 |

| E. coli K1077 | dam dcm mutant, plasmid purification for B. anthracis transformation | P. Model/M. Russel collection |

| B. anthracis Sterne 34F2 | Vaccine strain, pXO1+ and pXO2− | 56 |

| B. anthracis AHG188 | ermC replacement of srtA (BA0688/BAS0654) in strain Sterne | This work |

| B. anthracis AHG263 | Δ(srtA)::ermC CP-51 transduced into strain Sterne | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pOS1 | Multicopy shuttle vector | 52 |

| pAHG279 | Full-length srtA cloned in pOS1 | This work |

| pAHG277 | basCFLAG/MH6 cloned in pOS1 | This work |

| pAHG322 | basCFLAG/MH6 and srtA cloned in pOS1 | This work |

| pTS1 | Temperature-sensitive shuttle vector | 36 |

| pAHG107 | 5′-srtA-ermC-3′-srtA cassette in pTS1 | This work |

| pQE30 | Vector for expression cloning of His6 fusions | Qiagen |

| pAHG316 | srtAΔN cloned in pQE30 | This work |

| Phage | ||

| CP-51 | B. anthracis transducing phage | 20 |

The srtA mutant AHG263 was obtained by allelic replacement, introducing an erythromycin resistance gene (ermC) (54) into the srtA locus. Briefly, bacillus template DNA was isolated using the Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit (Promega) after 2 h of vegetative cell treatment with 10 mg/ml lysozyme at 37°C. 5′ and 3′ srtA-flanking sequences were PCR amplified from B. anthracis Sterne template DNA using the primer pairs SrtA-51-PstI (AACTGCAGGCCAGATAAAGCTTCGTCTAG) and SrtA-31-XmaI (TCCCCCCGGGTTCAGTCTGTTTCTTTTCAGC) as well as SrtA-52-XmaI (TCCCCCCGGGAAAGGTGTTTTATTTAGTGATATAGCTTC) and SrtA-32-NotI (ATTTGCGGCCGCAACATTATCAAATCGCTTCC). The srtA 5′-flanking (PstI/XmaI), ermC (released from pErmC with XmaI digestion) (35) and srtA 3′-flanking sequences (XmaI/NotI) were cloned, in that order, into pLC28 (10) to generate pAHG71. The 3.2-kb 5′-srtA-ermC-3′-srtA cassette was excised with PstI and NotI restriction, and the ends were filled with Klenow polymerase and then cloned into the SmaI site of the temperature-sensitive shuttle vector pTS1 (36), thereby generating pAHG107. The plasmid was transformed into B. anthracis Sterne using a previously developed protocol (53) and transformants were selected on LB agar with chloramphenicol. Allelic exchange was induced with a temperature shift to 43°C and erythromycin selection. The mutant allele obtained with this procedure (B. anthracis AHG188) was transduced using the CP-51 phage (20) and verified by Southern blot and Western blot.

For Southern blots, chromosomal DNA from both the wild-type and AHG263 strains was digested with ClaI, which cleaves srtA-flanking sequences as well as the ermC coding sequence. The products of the digestion were separated by electrophoresis, transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane (Roche), and probed with either srtA or ermC nucleic acid sequences. Probes were generated by PCR in the presence of digoxigenin-dUTP (DIG System, Roche Molecular Biochemicals) to label the reaction products. The srtA probe was amplified using primers SrtA-5-EcoRI and SrtA-3-PstI (see below), whereas primers Erm5 (TACACCTCCGGATAATAAA) and Erm3 (CACAAGACACTCTTTTTTC) were used to generate the ermC probe. Hybridization products were detected by chemiluminescence.

To analyze bacilli for the presence of sortase A in immunoblot assays, wild-type and mutant strains were grown in 4-ml cultures to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) 0.8. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 5 minutes and suspended in 1 ml TSM (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 500 mM sucrose, 10 mM MgCl2) and treated with 10 mg/ml lysozyme at 37°C for 2 h. Proteins were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and subjected to immunoblotting with anti-SrtA rabbit antibody raised from purified SrtAΔN (see below).

Purification of SrtAΔN protein.

Primers SrtA-N-BamHI (CGGGATCCAAGCCATTTTATGATGGATATCA) and SrtA-C-BamHI (CGGGATCCTTATTTCTTCGCCTTCGTTCCT) were used to PCR amplify the srtA gene from B. anthracis Sterne template DNA. The DNA fragment was digested with BamHI and cloned into pQE30 (QIAGEN) to generate pAHG316, which was then transformed into Escherichia coli XL1-Blue. Overnight cultures grown in the presence of 100 μg/ml ampicillin were diluted into 1 liter of fresh culture and then induced for expression with 1 mM isopropylthiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). When the culture reached an OD600 1.2, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 20 min, washed, and suspended in 20 ml of buffer A [50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl (pH 7.5)]. Bacteria were lysed in a French pressure cell at 14,000 lb/in2 and extracts were centrifuged twice at 32,600 x g for 15 min. The supernatant was applied to 1 ml of Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) Sepharose (QIAGEN), pre-equilibrated with buffer A. After two 10-ml washes with buffer A and one 10-ml wash with buffer B (buffer A supplemented with 10 mM imidazole), SrtAΔN was eluted in 4 ml of buffer A containing 0.5 M imidazole. The purified polypeptides were detected on Coomassie-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE).

In vitro analysis of sortase A activity.

Sortase activity was assayed in buffer A at 37°C for 15 h. The 2-aminobenzoyl (Abz)-LPETG-diaminopropionic acid (Dpn), Abz-LPATG-Dpn, Abz-LGATG-Dpn, Abz-NPKTG-Dpn, and Abz-LPNTA-Dpn peptides were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and added to the reaction at a final concentration of 10 μM. Purified SrtAΔN was added to the reaction at a final concentration of 15 μM. Reactions were quenched by boiling the samples for 5 min and peptide cleavage was monitored by fluorescence at 420 nm after excitation at 320 nm. The mean and standard deviation of three independent measurements are reported. Inhibition of SrtAΔN activity was achieved by addition of MTSET [2-(trimethylammonium)ethyl]methanethiosulfonate at a concentration of 5 mM. This inhibition was relieved by supplementing the reaction with 10 mM dithiothreitol.

Characterization of sortase A cleavage products.

Sortase reactions containing 10 μM of Abz-LPETG-Dnp and 15 μM of recombinant enzyme in a final volume of 1 ml of buffer A were incubated at 37°C for 15 h. The enzyme was removed by centrifugation on Centricon-10 (Millipore) at 7,500 x g and the filtrate was subjected to reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromotography purification on a C-18 column (2 by 250-mm, C18 Hypersil, Keystone Scientific). Cleaved products were eluted following the application of a linear gradient of acetonitrile from 1 to 100%. Eluted peptides were monitored at 215 nm.

Cell wall anchoring of BasCFLAG/MH6.

Plasmids used throughout this study were generated by ligating PCR-amplified DNA fragments at unique restriction sites into the shuttle vector pOS1 (52). To generate pAHG279, the srtA gene was amplified using primers SrtA-5-EcoRI (AAGAATTCTGTATCGACTGTTCTTTATAAAG) and SrtA-3-PstI (AACTGCAGTATTAATGGGAGTATGGTTAGC). For the construction of pAHG227, basC sequences specifying promoter nd Flag-tagged N-terminal portions of the polypeptide were amplified with the primers BasC-51-E (AAGAATTCTTGTATTAAGATGGGTTCGTTT) and BasC-31-K-Flag (CGGGATCCTTTGTCATCGTCGTCCTTGTAGTCATTATGAGTACTAGGTTGTTGCA). Amplification of C-terminal basC coding sequence with a six-His-tag and cell wall sorting signal required the primers BasC-52-K-MH6 (GGGGTACCATGCACCATCACCATCACCATGAAGTGCGTTTACCAGCTACT) and BasC-32-B (CGGGATCCCTACATTTCTTTTCTATTTTTCAT). pAHG322 was generated after insertion of the srtA sequence pAHG227. All ligation products were transformed into E. coli DH5α, and plasmid DNA of isolated transformants was analyzed by restriction analysis and DNA sequencing. Plasmids were then transformed into the dam dcm E. coli K1077 strain, DNA was purified without methylation products and finally transformed into B. anthracis cells (53).

Isolation of BasCFLAG/MH6 was achieved by growing 400 ml of cells harboring either pAHG227 or pAHG322 to an OD600 of 1.0. Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation, suspended in TSM-lysozyme buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.5 M sucrose, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mg/ml lysozyme), incubated for 5 h at 37°C, and sedimented by centrifugation at 32,600 x g for 15 min. To purify lysozyme-solubilized cell wall-anchored BasCFlag/MH6, cleared lysates were applied to 0.5 ml of Ni-NTA-Sepharose pre-equilibrated with buffer A and bound proteins were washed once with 10 ml of buffer A followed by a second wash with 10 ml buffer B. Proteins were eluted in 4 ml of buffer C. For the preparation of whole-cell sample extracts, sedimented cells were treated with TSM-lysozyme and lysed in a French pressure cell at 14,000 lb/in2. The lysate was centrifuged at 32,600 x g for 15 min. Proteins in the supernatant (cleared lysate) were purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography as described above. All purified proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and BasCFLAG/MH6 was detected using a FLAG-specific monoclonal antibody (Stratagene) and chemiluminescence.

Infection of A/J mice with B. anthracis spores.

B. anthracis Sterne as well as AHG263 mutant spores were obtained by transferring 2 ml of an overnight culture grown in LB-0.5% glucose to 30 ml of 2× SG medium (28). Cells were incubated for 4 days at 37°C with vigorous shaking, and the development of spores was examined by microscopic inspection of culture aliquots. Residual vegetative cells were heat killed by incubation at 65°C for one hour. Spores were sedimented by centrifugation at 6,000 x g, washed three times with 50 ml of sterile distilled water, and suspended in 1 ml of sterile distilled water. CFU were enumerated after serial dilution, plating on agar medium, and colony formation of spore preparations. Inbred A/J mice (Harlan) were used to investigate the virulence of the srtA mutant strain AHG263. Mice were infected subcutaneously with 1.56 × 102, 1.27 × 103, 2.03 × 104 and 1.98 × 105 wild-type spores or 1.36 × 102, 1.67 × 103, 1.93 × 104 and 1.66 × 105 mutant spores. Ten mice per dose and strain were infected, and the 50% lethal dose (LD50) for each strain was calculated following the Reed and Muench method (50).

RESULTS

Sortase genes in the genomes of B. anthracis strains Ames and Sterne.

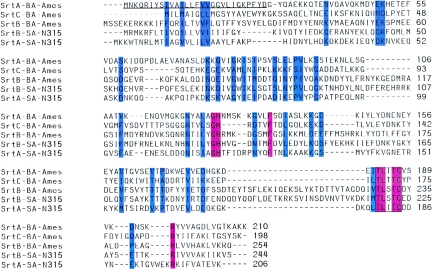

A bioinformatic approach was used to identify homologs of S. aureus srtA in the genome of B. anthracis strain Ames. BLAST searches identified BA0688, BA4783, and BA5069 as homologs of staphylococcal srtA (Fig. 1). BLAST searches were also used for pairwise comparison between the three B. anthracis sortases and S. aureus SrtA and SrtB (Fig. 1). BA0688, here putatively assigned as sortase A (SrtA), displayed 27% amino acid identity with S. aureus SrtA and 25% identity with S. aureus SrtB, whereas BA4783 [sortase B (SrtB)] encompasses 21% identity with staphylococcal SrtA and 42% identity with S. aureus sortase B. The third homolog, BA5069, displayed 27% identity with S. aureus SrtA and 29% identity with SrtB, but significantly higher degrees of identity were observed with homologs from B. subtilis, B. halodurans, or B. cereus (12). BA5069 was assigned as sortase C (SrtC).

FIG. 1.

Multiple sequence alignment of Staphylococcus aureus N315 (SA-N315) sortase A (SrtA) and sortase B (SrtB) and Bacillus anthracis Ames (BA-Ames) BA0688 (SrtA), BA4783 (SrtB), and BA5069 (SrtC). Identical residues are highlighted in red and conserved residues are in blue. The active-site signature sequence is boxed. The N-terminal residues encompassing the deletion of B. anthracis SrtAΔN generated for affinity chromatography purification of soluble sortase enzyme are underlined.

The genome sequence of the vaccine strain B. anthracis strain Sterne 34F2 has been completed (NCBI). As the present work focused on characterizing sortase genes in the attenuated vaccine strain, we examined the Sterne genome for sortase genes using BLAST searches. Again, three sortases were identified, BAS0654 (SrtA), BAS4438 (SrtB), and BAS4708 (SrtC), and their amino acid sequences were identical to those of B. anthracis strain Ames (Fig. 1).

Purified B. anthracis sortase A cleaves LPXTG peptides between the threonine and the glycine residues.

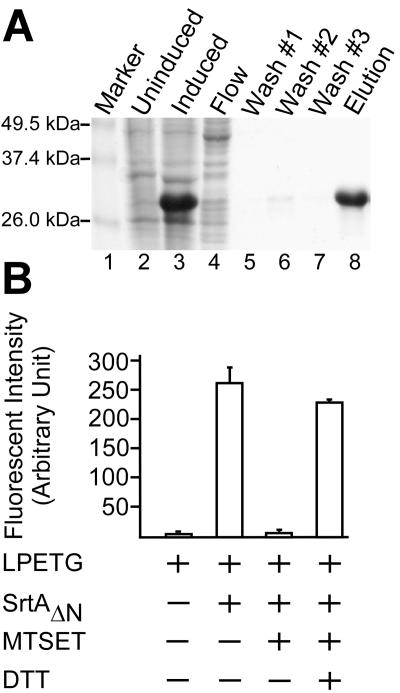

To characterize the gene product of BA0688, the coding sequence of B. anthracis srtA was PCR amplified with oligonucleotide primers in a manner that deleted the first 27 amino acid residues, encoding the signal peptide/membrane anchor of sortase A (Fig. 1). The DNA fragment was cloned into the plasmid vector pQE30 (QIAGEN), and expression was induced with IPTG via the lacuv5 promoter. The resulting hexahistidyl gene fusion product, B. anthracis SrtAΔN, was purified from cleared lysates via affinity chromatography on nickel-NTA-Sepharose and eluted with imidazole. After dialysis, protein concentration was determined and purity was assessed by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2A). The identity of the purified protein was verified by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) mass spectrometry (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Purification and characterization of B. anthracis sortase A (SrtA). (A) E. coli XL-1 Blue(pAHG316) expressing B. anthracis SrtAΔN, in which the N-terminal membrane anchor of sortase had been replaced with a six-histidyl tag, was lysed by French press. SrtAΔN was purified by affinity chromatography on Ni-NTA and analyzed on Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE. Lanes: 1, molecular weight markers; 2, French press extract of uninduced culture; 3, French press extract of 1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside-induced culture; 4, cleared lysate of French press extract of 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside-induced culture was loaded on the Ni-NTA column and flowthrough was collected; 5 to 7, wash buffer was used to remove contaminating protein; and 8, 1-ml fraction was eluted with 0.5 M imidazole. (B) Purified SrtAΔN was incubated with Abz-LPETG-Dpn substrate (LPETG), and cleavage was monitored as an increase in fluorescence. The reaction was inhibited by the addition of 1 mM MTSET. MTSET-treated SrtAΔN could be rescued by incubation with 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT).

Fluorescence of the Abz fluorophore (a) within the peptide a-LPETG-d is quenched by the close proximity to Dpn (d), a fluorescence quencher (58). When the peptide is cleaved by S. aureus sortase A and the Abz fluorophore is separated from Dpn, an increase in fluorescence is observed (22). Incubation of purified B. anthracis SrtAΔN with a-LPETG-d substrate resulted in an increase in fluorescence similar to that observed for purified S. aureus sortase A (58) (Fig. 2B). To test whether cleavage required the only thiol moiety (Cys187) of B. anthracis SrtA, the enzyme was incubated with [2-(trimethylammonium)-ethyl] methane-thiosulfonate (MTSET), a reagent that reacts rapidly with the active-site thiol of S. aureus SrtA (63, 74). Indeed, MTSET treatment abolished all B. anthracis SrtA cleavage of a-LPETG-d substrate. Methanethiosulfonate forms disulfide with sulfhydryl groups, and this product of inhibition can be resolved by reducing agents such as dithiothreitol. MTSET-inactivated B. anthracis SrtAΔN was incubated in the presence of 10 mM dithiothreitol, which restored most of the enzymatic activity (Fig. 2B). Together with the observation that B. anthracis SrtAΔN failed to cleave scrambled peptide sequence (GLETP) or S. aureus sortase B substrate (NPQTN) (data not shown), these observations suggest that B. anthracis sortase A cleaves the LPXTG motif of surface protein sorting signals in vitro. The specific activity of B. anthracis SrtAΔN is similar to that of S. aureus sortase A, which should render this enzyme useful for future biochemical studies (30, data not shown).

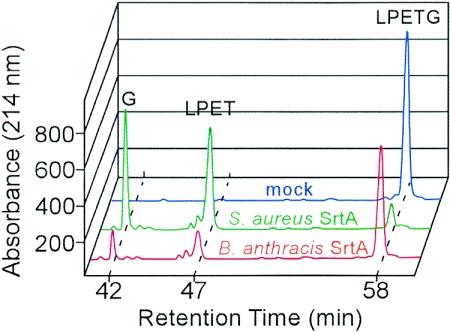

The B. anthracis SrtA cleavage product of the a-LPETG-d substrate was analyzed in an effort to ascertain whether sortase cleaved between the threonine and the glycine residues, similar to S. aureus SrtA. Reaction products were separated by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography, and absorbance at 215 nm was recorded (62). Eluted peaks were retrieved from collected fractions, and the molecular identity of compounds was verified by mass spectrometry. Mock-treated a-LPETG-d eluted at 58 min, but incubation of substrate with S. aureus SrtAΔN generated two product peaks, which eluted at 42 min (G-d) and 47 min (a-LPET) from reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (Fig. 3). Incubation of a-LPETG-d substrate with B. anthracis SrtAΔN generated product species identical to those observed for S. aureus SrtAΔN by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry (Fig. 3). Together these data reveal that B. anthracis SrtA cleaves LPETG peptides between the threonine and glycine residues.

FIG. 3.

B. anthracis sortase A (SrtA) cleaves the LPETG peptide between the threonine and glycine residues. Purified B. anthracis SrtAΔN was incubated with LPETG peptide (Abz-LPETG-Dpn), and cleavage products were separated by reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography. Sortase substrates and products were detected by absorbance at 215 nm and characterized by mass spectrometry. As a control, mock-treated and S. aureus SrtAΔN-treated peptides were separated by reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography. Data generated from three independent experiments were averaged and standard deviations were calculated.

B. anthracis vegetative cells express sortase A.

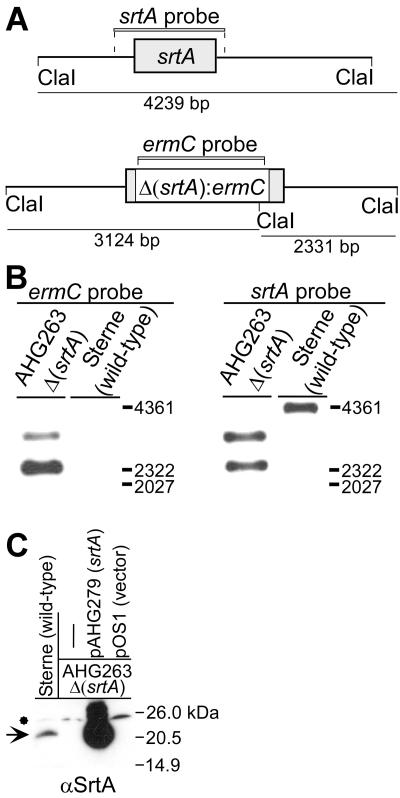

Purified B. anthracis SrtAΔN was injected subscapularly into rabbits to raise specific antibodies and the immune sera were used in immunoblotting experiments of bacterial extracts obtained from vegetative cells of B. anthracis strain Sterne. An immune-reactive species with an estimated mobility of 23 kDa was detected on 15% SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4). Further, detection of the 23-kDa species occurred by immune but not by preimmune sera, consistent with the notion that this species may represent sortase A (BA0688).

FIG. 4.

B. anthracis vegetative cells express sortase A (srtA). (A) Drawing depicts the srtA gene (211-codon open reading frame with a predicted molecular mass of 23.1 kDa for the SrtA polypeptide) on the chromosome of B. anthracis strain Sterne, flanked by ClaI restriction sites that release a 4,239-bp srtA probe-hybridizing fragment. A srtA mutant was generated by allelic replacement with the ermC gene, thereby generating two ClaI restriction fragments (3,124 and 2,331 bp in size), each of which hybridize with the ermC probe and with the srtA probe. (B) Southern blot hybridization of ClaI-restricted chromosomal DNA fragments and their hybridization signals with labeled srtA and ermC probes. (C) The cell wall envelope of vegetative cells of B. anthracis strain Sterne 34F2 and its isogenic Δ(srtA)::ermC mutant, strain AHG263, were cleaved with lysozyme, and proteins were solubilized in sample buffer prior to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis. The arrow denotes the SrtA immune-reactive species, whereas the asterisk indicates a cross-reactive species. Strain AHG263 was transformed with multicopy vector pOS1 or pAHG279, i.e., recombinant pOS1 harboring the srtA gene.

To confirm the identity on the 23-kDa immune-reactive species, the sortase A gene was deleted by allelic replacement with the ermC marker, and the mutation was then transduced into B. anthracis strain Sterne with bacteriophage CP-51 (20), generating strain AHG263. DNA extracted from parent strain Sterne was subjected to nucleotide hybridization (Southern blot) analysis with the srtA probe, spanning gene coding and flanking sequences (Fig. 4A). A 4,361-bp ClaI fragment was detected with the srtA probe, whereas Southern blotting of ClaI-restricted DNA from the mutant strain AHG263 detected 2,331- and 3,124-bp fragments. Probing ClaI-digested chromosomal DNA with labeled ermC DNA also revealed the 2,331- and 3,124-bp Δ(srtA):ermC fragments. As expected, the ermC probe did not detect hybridizing species in the chromosomal DNA of B. anthracis strain Sterne (Fig. 4B). These data demonstrate that the srtA coding sequence in strain AHG263 had been replaced with ermC.

Immunoblotting with anti-SrtA failed to detect the 23-kDa immune reactive species in strain AHG263, but transformation of the mutant strain with plasmid encoded sortase A (pAHG279) not only restored the appearance of the 23-kDa immune-reactive species but also led to the overexpression of sortase A (48) (Fig. 4C). As a control, transformation of strain AHG263 with pOS1 vector DNA did not affect the expression of the 23-kDa immune-reactive species (Fig. 4C). Together these results indicate that anti-SrtA detects sortase A expression in B. anthracis strain Sterne vegetative cells.

B. anthracis strain Sterne encodes eleven putative surface protein genes.

Previous work used amino acid sequences of mature, anchored surface proteins or their cell wall sorting signals as queries in BLAST searches to identify protein genes in newly sequenced genomes of Gram-positive bacteria (12, 49). Höök and colleagues used a similar approach to identify two B. anthracis homologs (BA0871 and BA5258) of S. aureus CNA, a collagen-binding MSCRAMM (microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules) expressed by S. aureus strains that have been isolated from osteomyelitis and connective tissue infections (43, 44). Recently published work demonstrated that purified recombinant surface proteins BA0871 and BA5258 indeed bind collagen in a manner that resembles collagen binding of S. aureus CNA (70).

A bioinformatics approach was used here for the preliminary identification of surface protein genes in B. anthracis strains Ames and Sterne. In addition to BA0871 and BA5258, BLAST searches with the sorting signals from 20 known staphylococcal surface protein genes identified nine other genes in the genome of strain Sterne. Table 2 summarizes the identified surface protein genes of B. anthracis, their sorting signal motif sequences, predicted functions, and NCBI identification numbers. In addition to the nine known surface protein genes from the Ames strain, B. anthracis strain Sterne encodes a collagen adhesin gene (BAS5207) and BAS4798, a gene with unknown function. Of note, BA3254/BAS3021 (LPNAG motif) was assigned as the sortase A substrate, because amino acid substitution of threonine with alanine in the LPXTG motif does not interfere with S. aureus sortase A substrate recognition (22, 61).

TABLE 2.

Bioinformatic identification of B. anthracis surface proteins

| Proteina | Amesb | Sterneb | Function | No. of amino acidsc | Motif | Predicted sortased | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BasA | BA4346 | BAS4031 | 2′,3′ cyclic nucleotide 2′ phosphodiesterase | 774 | LPKTG | SrtA | 49 |

| BasB | BA0871 | BAS0828 | Collagen adhesin | 969 | LPATG | SrtA | 49 |

| BasC | BA5258 | BAS4884 | Collagen adhesin | 627 | LPATG | SrtA | 49 |

| BasD | BA3367 | BAS3121 | Unknown | 595 | LPKTG | SrtA | 49 |

| BasE | BA3254 | BAS3021 | Unknown | 372 | LPNAG | SrtA | 49 |

| BasF | BAS5207 | Collagen adhesin | 882 | LPNTG | SrtA | This work | |

| BasG | BAS4798 | Unknown | 2,025 | LPKTG | SrtA | This work | |

| BasH | BA0397 | BAS0383 | Unknown | 257 | LPNTA | SrtC | 12, 49 |

| BasI | BA5070 | BAS4709 | Unknown | 148 | LPNTA | SrtC | 12, 49 |

| BasJ | BA0552 | BAS0520 | Internalin/LRRe | 1,070 | LGATG | ? | 49 |

| BasK | BA4789 | BAS4444 | Heme transport | 237 | NPKTG | SrtB | 49 |

BAS, Bacillus anthracis surface protein.

NCBI identification number.

Number of codons in the entire open reading frame.

See text for details on the assignment of sortase substrates.

LRR, leucine-rich repeats.

The B. anthracis isd locus encodes IsdC, the heme-binding protein substrate of S. aureus sortase B (33, 35, 55). However, in contrast to S. aureus IsdC substrate with an NPQTN motif, B. anthracis SrtB is presumed to cleave its substrate at an NPKTG motif (73). Two predicted surface proteins encompass C-terminal sorting signals with LPNTA motifs (BA0397 and BA5070) and were assigned as putative sortase C substrates, as one of the two genes is positioned immediately adjacent to srtC (BA5069) (12). The surface protein gene BA0552, with an LGATG motif sorting signal, displays homology to the leucine rich domain of Listeria monocytogenes internalins (19). A prediction for sortase recognition of this presumed gene product has thus far not been achieved (12, 17) (Table 2).

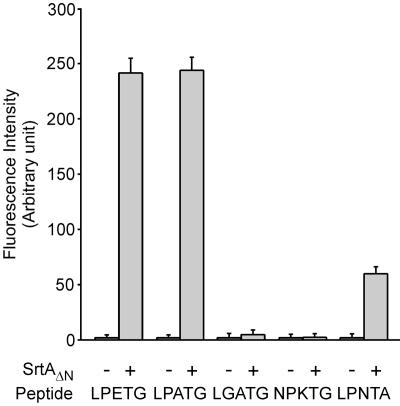

To examine substrate recognition by B. anthracis sortase A in vitro, purified SrtAΔN was incubated with a-LPETG-d, a-LPATG-d, a-LGATG-d, a-NPKTG-d, and a-LPNTA-d peptides and substrate cleavage was measured by fluroescence resonance energy transfer analysis (Fig. 5). B. anthracis sortase A cleaved the LPETG and LPATG peptides with equal efficiency, whereas the LGATG and NPKTG peptides were not cleaved. Further, only a small amount of cleavage of LPNTA peptide was observed, suggesting that the preferred substrates of B. anthracis sortase A are surface protein sorting signals with LPXTG motifs.

FIG. 5.

Substrate specificity of B. anthracis sortase A (SrtA). B. anthracis SrtAΔN was purified as described in the legend to Fig. 2 and incubated with presumed substrate peptides Abz-LPETG-Dpn (LPETG), Abz-LPATG-Dpn (LPATG), Abz-LGATG-Dpn (LGATG), Abz-NPKTG-Dpn (NPKTG), and Abz-LPNTA-Dpn (LPNTA). Substrate cleavage was monitored as an increase in fluorescence. Data generated from three independent experiments were averaged and standard deviations were calculated.

B. anthracis srtA is required for the cell wall anchoring of BasC (BA5258).

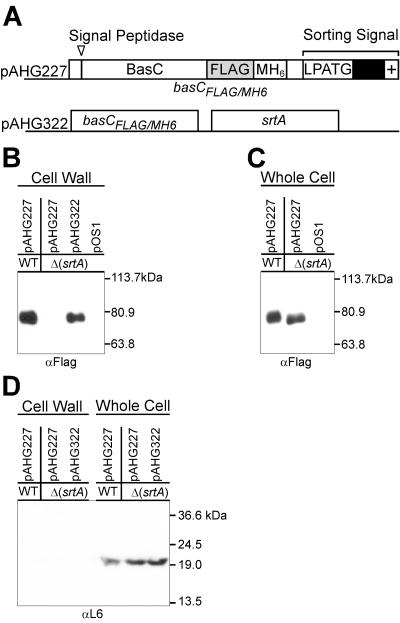

To test whether B. anthracis sortase A is required for the cell wall anchoring of surface proteins in vivo, we focused on BasC (BA5258). Our experimental design employed a recombinant basC gene, modified by in-frame insertion of a short nucleotide sequence encoding the FLAG epitope and a six-histidyl tag (BasCFLAG/MH6) (35) (Fig. 6A). Plasmid pAHG227 encoding BasCFLAG/MH6 was transformed into B. anthracis strain Sterne or its isogenic variant AHG239 (ΔsrtA). Whole-cell extracts of the transformants were subjected to affinity chromatography on Ni-NTA and eluted fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody, revealing immune-reactive BasCFLAG/MH6species. B. anthracis parent strain Sterne immune-reactive species migrated more slowly on SDS-PAGE than BasCFLAG/MH6 expressed by AHG239, an observation that is consistent with the posttranslational anchoring of surface protein to the cell wall envelope (39) (Fig. 6). As a control, transformation of strain AHG239 with the plasmid vector pOS1 did not generate anti-FLAG immune-reactive species.

FIG. 6.

B. anthracis srtA gene is required for cell wall anchoring of BasC. (A) Plasmid pAHG227 expresses the basCFLAG/MH6 gene. A FLAG epitope tag and methionyl-six-histidyl (MH6) affinity chromatography tag were inserted upstream of the cell wall sorting signal (pAHG227). (B) After transformation of vegetative cells with pAHG227 or empty vector plasmid (pOS1), mid-log-phase bacilli were harvested by centrifugation and washed, and the cell wall envelope was digested with lysozyme. Cleared crude lysate of B. anthracis vegetative cell extracts was subjected to affinity chromatography, and eluates were analyzed for the presence of BasCFLAG/MH6 using FLAG monoclonal antibodies and immunoblotting. As a control, bacilli were transformed with pOS1 vector or with pAHG322, which carries an insertion of the B. anthracis srtA gene into pAHG227 and was used for complementation studies. (C) The cell wall envelope of mid-log-phase bacilli was digested with lysozyme. After sedimentation of the resulting protoplasts, the cell wall lysate was applied to affinity chromatography on Ni-NTA and eluted with imidazole. Proteins in the eluate were then subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibodies. (D) Ribosomal protein L6 was detected by immunoblotting in whole-cell lysates but not in the cell wall compartment of bacilli.

To further examine the cell wall anchoring of BasCFLAG/MH6,the cell wall envelope was digested with muramidase under conditions that stabilized the resulting protoplasts. Following sedimentation of bacilli via centrifugation, the cell wall lysate was removed with the supernatant and subjected to affinity chromatography on Ni-NTA. Immunoblotting of eluted fractions revealed the presence of BasCFLAG/MH6 in the cell wall fraction of B. anthracis strain Sterne but not in the cell wall envelope of the sortase mutant strain AHG239 (Fig. 6B). However, transformation of strain AHG239 with pAHG322 (wild-type srtA) restored the cell wall anchoring of BasCFLAG/MH6, as immuno-reactive species could be purified from cell wall lysates of pAHG316 transformants, but not from lysates of strains harboring the vector control plasmid pOS1 (Fig. 6B). As a control for proper fractionation, ribosomal protein L6 was detected by immuno-blotting in whole-cell lysates but not in the cell wall compartment of bacilli (Fig. 6D).

srtA gene of B. anthracis strain Sterne is not required for the development of acute anthrax disease in A/J mice.

B. anthracis secretes lethal toxin and edema toxin to cause anthrax disease (11). Three pXO1 virulence plasmid genes encode subunits for both toxins, pag (protective antigen), lef (lethal factor), and cya (edema factor), as protective antigen performs binding and host cell transport functions for both lethal factor and edema factor (11). The toxin genes are known to be essential for disease progression in multiple animal models of anthrax cutaneous infection, including guinea pigs and A/J mice (6, 7, 46). Further, antibodies against protective antigen appear to be a critical factor in protective immunity (23, 67).

B. anthracis strain Sterne lacks the pXO2 virulence plasmid, encoding the capABCD genes responsible for synthesis of the poly-d-glutamic acid capsule (18, 40, 56). The glutamate capsule of B. anthracis is essential for the pathogenesis of cutaneous anthrax infections in mice and presumably in many other animal infections (16), but strain Sterne retains significant virulence in the A/J mouse model, as these animals display significant defects in phagocytic killing of bacterial pathogens (68, 69).

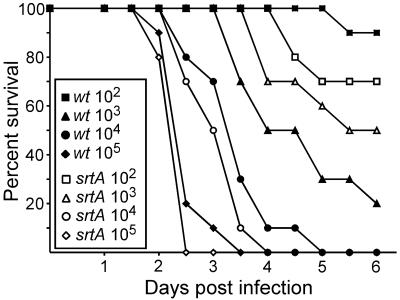

B. anthracis strain Ames LD50 doses of 50 spores are required for the development of lethal anthrax disease in mice (46), whereas a subcutaneous LD50 dose of 106 Sterne spores is required to generate a similar disease (46). Welkos, Friedlander and colleagues showed that subcutaneous infection of A/J mice with B. anthracis strain Sterne spores leads to an acute lethal disease at a dose of 102 to 103 spores (68). To test whether sortase A and therefore sortase A-anchored surface proteins play a role in the pathogenesis of anthrax disease, A/J mice were infected subcutaneously with 1.56 × 102, 1.27 × 103, 2.03 × 104 and 1.98 × 105 spores of B. anthracis strain Sterne or 1.36 × 102, 1.67 × 103, 1.93 × 104 and 1.66 × 105 spores of its isogenic variant AHG239. Figure 7 displays the data of a time-to-death analysis for both strains. Death occurred between days 2 and 4 following inoculation with a calculated LD50 dose of 632 spores for B. anthracis Sterne and 1,110 spores for strain AHG239. The observed difference in LD50 doses between the two strains was not statistically significant. We also analyzed the replication of anthrax bacilli in infected tissues (liver, spleen, brain, and blood) and observed no significant difference in replication between strain Sterne and AHG239 (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Sortase A gene of B. anthracis strain Sterne is not required for anthrax disease in the A/J mouse model. A/J mice, 10 per group, were infected by subcutaneous injection of 0.1 ml of spore suspension in phosphate-buffered saline and observed for a lethal infection over a period of 14 days (data points did not change after day 6). Both death and time-to-death were recorded and analyzed for spore infection doses of 1.56 × 102, 1.27 × 103, 2.03 × 104 and 1.98 × 105 for B. anthracis Sterne and 1.36 × 102, 1.67 × 103, 1.93 × 104 and 1.66 × 105 for strain AHG263 (determined by enumerating colonies on Luria agar after incubation at 37°C). The legend identifies data points for parent strain Sterne 34F2 (open symbols) and the isogenic ΔsrtA variant (solid symbols). Using these data and the Reed and Muench method (50), LD50 doses for strain Sterne 34F2 (632 spores) and the ΔsrtA strain AHG239 variant (1,110 spores) were calculated.

DISCUSSION

Secretion of lethal toxin and edema toxin by vegetative bacilli is critical in the pathogenesis of anthrax disease and crucial for toxin-mediated killing of infected hosts (11). Early events in anthrax pathogenesis are much less understood (37). For example, the genetic requirement for entry of spores across respiratory or intestinal epithelia has not been fully explored (16). Other fundamental questions, whether spores specifically bind to host cell receptors to mediate entry and germination or use surface proteins on vegetative cells for binding to specific tissues or invasion of host cells, have not been addressed (37). Bioinformatic analysis of the B. anthracis genome sequence identified surface proteins such as the collagen adhesin BasC that may function as MSCRAMMs in binding to connective tissues, and an internalin-like molecule that could mediate host cell invasion of anthrax bacilli (49, 71). Although bioinformatic analysis provides a guide for physiological function, the relative contribution of various surface proteins to disease pathogenesis cannot be gleaned from the sum of all putative binding activities.

Recent work in S. aureus suggests that sortase A and sortase B mutations abolish the cell wall anchoring and surface display of all proteins bearing sorting signals with LPXTG or NPQTN motifs (34). The relative contribution of cell wall-anchored surface proteins to disease pathogenesis can therefore be examined by comparing the virulence of sortase mutant strains with the wild-type parent. In S. aureus, sortase mutants display a three log reduction in the ability to form abscesses, a dramatic defect that remains the largest reduction in virulence for staphylococcal knockout mutants (26, 31, 66). Sortase A mutations in L. monocytogenes on the other hand displayed only a modest defect in the pathogenesis of acute listeriosis in mice, although the cell wall anchoring of about 20 different internalins is thought to be abrogated (3, 4). It is presumed that a second anchoring mechanisms of listerial surface proteins, binding of internalin B to lipoteichoic acids, plays a critical role in bacterial invasion of mouse cells and is responsible for the manifestation of disease (13, 15, 24). Presumably, sortase A-anchored proteins may play a much larger role during the pathogenesis of listerial infections in humans (27).

In this report we have characterized sortase A of B. anthracis and examined srtA mutants for their ability to cause disease in the A/J mouse model. Similar to srtA mutations in L. monocytogenes, we observed no significant defect in the ability to cause acute lethal disease. Does this indicate that sortase A-anchored surface proteins are dispensable for anthrax disease in animals or humans? We think not. Mice are not a physiological host for B. anthracis, and mice in fact appear hypersensitive to anthrax disease following the injection of spores (46, 47). For example, mutants lacking the gene for protective antigen, an essential component for the delivery of lethal and edema toxins, do not display a phenotype in a murine infection model with virulent B. anthracis strains (9, 46). In contrast, a dramatic defect for protective antigen mutants can be observed in a guinea pig infection model (47). Thus, although our data provide evidence that srtA is not required for B. anthracis strain Sterne pathogenesis in the A/J mouse model of disease, additional work is needed to reveal the contribution of LPXTG-type surface proteins in other models of anthrax disease.

While the studies here can presumptively assign five or seven surface protein substrates to sortase A in strains Ames and Sterne, the substrates of B. anthracis sortases B and C remain unknown. In fact, the identification of four different types of sorting signal motifs and their relationship with three sortases remains an enigma that can only be resolved experimentally. Future work must therefore focus on the identification of surface protein substrates for sortases and their contribution to anthrax disease in several different animal models of infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christina Tam for help with transduction experiments and members of our laboratory for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by United States Public Health awards from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Infectious Diseases Branch (AI38897 and AI52474 to Olaf Schneewind). E. M. Glass, K. L. DeBord, and O. Schneewind acknowledge membership within and support from the Region V “Great Lakes” Regional Center of Excellence in Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases Consortium (GLRCE, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Award 1-U54-AI-057153).

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnett, T. C., A. R. Patel, and J. R. Scott. 2004. A novel sortase, SrtC2, from Streptococcus pyogenes anchors a surface protein containing a QVPTGV motif to the cell wall. J. Bacteriol. 186:5865-5875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnett, T. C., and J. R. Scott. 2002. Differential recognition of surface proteins in Streptococcus pyogenes by two sortase gene homologs. J. Bacteriol. 184:2181-2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bierne, H., C. Garandeau, M. G. Pucciarelli, C. Sabet, S. Newton, F. Garcia-del Portillo, P. Cossart, and A. Charbit. 2004. Sortase B, a new class of sortase in Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacteriol. 186:1972-1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bierne, H., S. K. Mazmanian, M. Trost, M. G. Pucciarelli, P. Dehoux, L. Jansch, F. G. Portillo, L. G., O. Schneewind, and P. Cossart. 2002. Inactivation of the srtA gene in Listeria monocytogenes inhibits anchoring of surface proteins and affects virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 43:869-881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolken, T. C., C. A. Franke, K. F. Jones, G. O. Zeller, C. H. Jones, E. K. Dutton, and D. E. Hruby. 2001. Inactivation of the srtA gene in Streptococcus gordonii inhibits cell wall anchoring of surface proteins and decreases in vitro and in vivo adhesion. Infect. Immun. 69:75-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brossier, F., and M. Mock. 2001. Toxins of Bacillus anthracis. Toxicon 39:1747-1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brossier, F., M. Weber-Levy, M. Mock, and J.-C. Sirard. 2000. Role of toxin functional domains in anthrax pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 68:1781-1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bullock, W. O., J. M. Fernandez, and J. M. Short. 1987. XL-1 Blue: a high efficiency plasmid transforming recA Escherichia coli strain with b-galactosidase selection. BioTechniques 5:376. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cataldi, A., E. Labruyère, and M. Mock. 1990. Construction and characterization of a protective antigen-deficient Bacillus anthracis strain. Mol. Microbiol. 4:1111-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng, L. W., D. M. Anderson, and O. Schneewind. 1997. Two independent type III secretion mechanisms for YopE in Yersinia enterocolitica. Mol. Microbiol. 24:757-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collier, R. J., and J. A. Young. 2003. Anthrax toxin. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 19:45-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Comfort, D., and R. T. Clubb. 2004. A comparative genome analysis idenitifies distinct sorting pathways in gram-positive bacteria. Infect. Immun. 72:2710-2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cossart, P., and R. Jonquieres. 2000. Sortase, a universal target for therapeutic agents against gram-positive bacteria? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:5013-5015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhar, G., K. F. Faull, and O. Schneewind. 2000. Anchor structure of cell wall surface proteins in Listeria monocytogenes. Biochemistry 39:3725-3733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dramsi, S., P. Dehoux, M. Lebrun, P. Goossens, and P. Cossart. 1995. Identification of four new members of the internalin multigene family of Listeria monocytogenes EGD. Infect. Immun. 65:1615-1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drysdale, M., S. Heninger, J. Hutt, Y. Chen, C. R. Lyons, and T. M. Koehler. 2005. Capsule synthesis by Bacillus anthracis is required for dissemination in murine inhalation anthrax. EMBO J. 24:221-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dussurget, O., J. Pizarro-Cerda, and P. Cossart. 2004. Molecular determinants of Listeria monocytogenes virulence. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58:587-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ezzel, J. W., and S. L. Welkos. 1999. The capsule of Bacillus anthracis, a review. J. Appl. Microbiol. 87:250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaillard, J.-L., P. Berche, C. Frehel, E. Gouin, and P. Cossart. 1991. Entry of L. monocytogenes into cells is mediated by internalin, a repeat protein reminiscent of surface antigens from gram-positive cocci. Cell 65:1127-1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green, B. D., L. Battisti, T. M. Koehler, C. B. Thorne, and B. E. Ivins. 1985. Demonstration of a capsule plasmid in Bacillus anthracis. Infect. Immun. 49:291-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanahan, D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang, X., A. Aulabaugh, W. Ding, B. Kapoor, L. Alksne, K. Tabei, and G. Ellestad. 2003. Kinetic mechanism of Staphylococcus aureus sortase SrtA. Biochemistry 42:11307-11315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ivins, B. E., S. L. Welkos, S. F. Little, M. H. Crumrine, and G. O. Nelson. 1992. Immunization against anthrax with Bacillus anthracis protective antigen combined with adjuvants. Infect. Immun. 60:662-668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jonquieres, R., H. Bierne, F. Fiedler, P. Gounon, and P. Cossart. 1999. Interaction between the protein InlB of Listeria monocytogenes and lipoteichoic acid: a novel mechanism of protein association at the surface of gram-positive bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 34:902-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jonsson, I. M., S. K. Mazamanian, O. Schneewind, M. Vendrengh, T. Bremell, and A. Tarkowski. 2002. On the role of Staphylococcus aureus sortase and sortase-catalyzed surface protein anchoring in murine septic arthritis. J. Infect. Dis. 185:1417-1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jonsson, I. M., S. K. Mazmanian, O. Schneewind, T. Bremell, and A. Tarkowski. 2003. The role of Staphylococcus aureus sortase A and sortase B in murine arthritis. Microb. Infect. 5:775-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lecuit, M., S. Vandormael-Pournin, J. Lefort, M. Huerre, P. Gounon, C. Dupuy, C. Babinet, and P. Cossart. 2001. A transgenic model for listeriosis: role of internalin in crossing the intestinal barrier. Science 292:1722-1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leighton, T. J., and R. H. Doi. 1971. The stability of messenger ribonucleic acid during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 246:3189-3195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marraffini, L. A., and O. Schneewind. 2005. Anchor structure of staphylococcal surface proteins. V. Anchor structure of the sortase B substrate IsdC. J. Biol. Chem. 280:16263-16271. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Marraffini, L. A., H. Ton-That, Y. Zong, S. V. L. Narayana, and O. Schneewind. 2004. Anchoring of surface proteins to the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus. IV. A conserved arginine residue is required for efficient catalysis of sortase A. J. Biol. Chem. 279:37763-37770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mazmanian, S. K., G. Liu, E. R. Jensen, E. Lenoy, and O. Schneewind. 2000. Staphylococcus aureus mutants defective in the display of surface proteins and in the pathogenesis of animal infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:5510-5515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mazmanian, S. K., G. Liu, H. Ton-That, and O. Schneewind. 1999. Staphylococcus aureus sortase, an enzyme that anchors surface proteins to the cell wall. Science 285:760-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazmanian, S. K., E. P. Skaar, A. H. Gasper, M. Humayun, P. Gornicki, J. Jelenska, A. Joachimiak, D. M. Missiakas, and O. Schneewind. 2003. Passage of heme-iron across the envelope of Staphylococcus aureus. Science 299:906-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mazmanian, S. K., H. Ton-That, and O. Schneewind. 2001. Sortase-catalyzed anchoring of surface proteins to the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1049-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazmanian, S. K., H. Ton-That, K. Su, and O. Schneewind. 2002. An iron-regulated sortase enzyme anchors a class of surface protein during Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:2293-2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDevitt, D., P. Francois, P. Vaudaux, and T. J. Foster. 1994. Molecular characterization of the clumping factor (fibrinogen receptor) of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 11:237-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mock, M., and A. Fouet. 2001. Anthrax. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:647-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Navarre, W. W., and O. Schneewind. 1994. Proteolytic cleavage and cell wall anchoring at the LPXTG motif of surface proteins in gram-positive bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 14:115-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Navarre, W. W., H. Ton-That, K. F. Faull, and O. Schneewind. 1998. Anchor structure of staphylococcal surface proteins. II. COOH-terminal structure of muramidase and amidase-solubilized surface protein. J. Biol. Chem. 273:29135-29142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okinaka, R., K. Cloud, O. Hampton, A. Hoffmaster, K. Hill, P. Keim, T. Koehler, G. Lamke, S. Kumano, D. Manter, Y. Martinez, D. Ricke, R. Svensson, and P. Jackson. 1999. Sequence, assembly and analysis of pX01 and pX02. J. Appl. Microbiol. 87:261-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okinaka, R. T., K. Cloud, O. Hampton, A. R. Hoffmaster, K. K. Hill, P. Keim, T. M. Koehler, G. Lamke, S. Kumano, J. Mahillon, D. Manter, Y. Martinez, D. Ricke, R. Svensson, and P. J. Jackson. 1999. Sequence and organization of pXO1, the large Bacillus anthracis plasmid harboring the anthrax toxin genes. J. Bacteriol. 181:6509-6515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pallen, M. J., A. C. Lam, M. Antonio, and K. Dunbar. 2001. An embarrassment of sortases-a richness of substrates. Trends Microbiol. 9:97-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patti, J. M., T. Bremell, D. Krajewska-Pietrasik, A. Abdelnour, A. Tarkowski, C. Ryden, and M. Höök. 1994. The Staphylococcus aureus collagen adhesin is a virulence determinant in experimental septic arthritis. Infect. Immun. 62:152-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patti, J. M., H. Jonsson, B. Guss, L. M. Switalski, K. Wiberg, M. Lindberg, and M. Höök. 1992. Molecular characterization and expression of a gene encoding a Staphylococcus aureus collagen adhesin. J. Biol. Chem. 267:4766-4772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perry, A. M., H. Ton-That, S. K. Mazmanian, and O. Schneewind. 2002. Anchoring of surface proteins to the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus. III. Lipid II is an in vivo peptidoglycan substrate for sortase-catalyzed surface protein anchoring. J. Biol. Chem. 277:16241-16248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pezard, C., P. Berche, and M. Mock. 1991. Contribution of individual toxin components to virulence of Bacillus anthracis. Infect. Immun. 59:3472-3477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pezard, C., M. Weber, J.-C. Sirard, P. Berche, and M. Mock. 1995. Protective immunity induced by Bacillus anthracis toxin-deficient strains. Infect. Immun. 63:1369-1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Quinn, C. P., and B. N. Dancer. 1990. Transformation of vegetative cells of Bacillus anthracis with plasmid DNA. J. Gen. Microbiol. 136:1211-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Read, T. D., S. N. Peterson, N. Tourasse, L. W. Baille, I. T. Paulsen, K. E. Nelson, H. Tettelin, D. E. Fouts, J. A. Eisen, S. R. Gill, E. K. Holtzapple, O. A. Okstad, E. Helgason, J. Rilstone, M. Wu, J. F. Kolonay, M. J. Beanan, R. J. Dodson, L. M. Brinkac, M. Gwinn, R. T. DeBoy, R. Madpu, S. C. Daugherty, A. S. Durkin, D. H. Haft, W. C. Nelson, J. D. Peterson, M. Pop, H. M. Khouri, D. Radune, J. L. Benton, Y. Mahamoud, L. Jiang, I. R. Hance, J. F. Weidman, K. J. Berry, R. D. Plaut, A. M. Wolf, K. L. Watkins, W. C. Nierman, A. Hazen, R. T. Cline, C. Redmond, J. E. Thwaite, O. WHite, S. L. Salzberg, B. Thomason, A. M. Friedlander, T. M. Koehler, P. C. Hanna, A. B. Kolsto, and C. M. Fraser. 2003. The genome sequence of Bacillus anthracis Ames and comparison to closely related bacteria. Nature 423:81-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reed, L. J., and H. Muench. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 27:493-497. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schneewind, O., A. Fowler, and K. F. Faull. 1995. Structure of the cell wall anchor of surface proteins in Staphylococcus aureus. Science 268:103-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schneewind, O., P. Model, and V. A. Fischetti. 1992. Sorting of protein A to the staphylococcal cell wall. Cell 70:267-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schurter, W., M. Geiser, and D. Mathe. 1989. Efficient transformation of Bacillus thuringiensis and B. cereus via electroporation: transformation of acrystalliferous strains with a cloned delta-endotoxin gene. Mol. Gen. Genet. 218:177-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shivakumar, A. G., and D. Dubnau. 1981. Characterization of a plasmid-specified ribosome methylase associated with macrolide resistance. Nucleic Acids Res. 9:2549-2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Skaar, E. P., and O. Schneewind. 2004. Iron-regulated surface determinants (Isd) of Staphylococcus aureus: stealing iron from heme. Microbes Infect. 6:390-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sterne, M. 1937. Avirulent anthrax vaccine. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Sci. Anim. Ind. 21:41-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ton-That, H., K. F. Faull, and O. Schneewind. 1997. Anchor structure of staphylococcal surface proteins. I. A branched peptide that links the carboxyl terminus of proteins to the cell wall. J. Biol. Chem. 272:22285-22292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ton-That, H., G. Liu, S. K. Mazmanian, K. F. Faull, and O. Schneewind. 1999. Purification and characterization of sortase, the transpeptidase that cleaves surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus at the LPXTG motif. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:12424-12429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ton-That, H., L. Marraffini, and O. Schneewind. 2004. Sortases and pilin elements involved in pilus assembly of Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Mol. Microbiol. 53:1147-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ton-That, H., L. A. Marraffini, and O. Schneewind. 2004. Protein sorting to the cell wall envelope of Gram-positive bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1694:269-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ton-That, H., S. K. Mazmanian, L. Alksne, and O. Schneewind. 2002. Anchoring of surface proteins to the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus. II. Cysteine 184 and histidine 120 of sortase A form a thiolate imidazolium ion pair for catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 277:7447-7452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ton-That, H., S. K. Mazmanian, K. F. Faull, and O. Schneewind. 2000. Anchoring of surface proteins to the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus. I. Sortase catalyzed in vitro transpeptidation reaction using LPXTG peptide and NH2-Gly3 substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 275:9876-9881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ton-That, H., and O. Schneewind. 1999. Anchor structure of staphylococcal surface proteins. IV. Inhibitors of the cell wall sorting reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 274:24316-24320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ton-That, H., and O. Schneewind. 2004. Assembly of pili in gram-positive bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 12:251-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ton-That, H., and O. Schneewind. 2003. Assembly of pili on the surface of C. diphtheriae. Mol. Microbiol. 50:1429-1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weiss, W. J., E. Lenoy, T. Murphy, L. Tardio, P. Burgio, S. J. Projan, O. Schneewind, and L. Alksne. 2004. Effect of srtA and srtB gene expression on the virulence of Staphylococcus aureus in animal infection. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:480-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Welkos, S., S. Little, A. Friedlander, D. Fritz, and P. Fellows. 2001. The role of antibodies to Bacillus anthracis and anthrax toxin components in inhibiting the early stages of infection by anthrax spores. Microbiology 147:1677-1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Welkos, S. L., T. J. Keener, and P. H. Gibbs. 1986. Differences in susceptibility of inbred mice to Bacillus anthracis. Infect. Immun. 51:795-800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Welkos, S. L., R. W. Trotter, D. M. Becker, and G. O. Nelson. 1989. Resistance to the Sterne strain of B. anthracis: phagocytic cell responses of resistant and susceptible mice. Microb. Pathog. 7:15-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xu, L., A. Sanchez, Z. Yang, S. R. Zaki, E. G. Nabel, S. T. Nichol, and G. J. Nabel. 1998. Immunization for Ebola virus infection. Nat. Med. 4:37-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xu, Y., X. Liang, Y. Chen, T. M. Koehler, and M. Höök. 2004. Identification and biochemical characterization of two novel collagen binding MSCRAMMS of Bacillus anthracis. J. Biol. Chem. 279:51760-51768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yeung, M. K. 2000. Actinomyces: surface macromolecules and bacteria-host interactions, p. 583-593. In V. A. Fischetti, R. P. Novick, J. J. Ferretti, D. A. Portnoy, and J. I. Rood (ed.), Gram-positive pathogens. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 73.Zhang, R.-g., G. Joachimiak, R.-y. Wu, S. K. Mazmanian, D. M. Missiakas, O. Schneewind, and A. Joachimiak. 2004. Structures of sortase B from Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus anthracis reveal catalytic amino acid triad in the active site. Structure 12:1147-1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zong, Y., T. W. Bice, H. Ton-That, O. Schneewind, and S. V. L. Narayana. 2004. Crystal structures of Staphylococcus aureus sortase A and its substrate complex. J. Biol. Chem. 279:31383-31389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]