Abstract

The importance of conjugation as a mechanism to spread biofilm determinants among microbial populations was illustrated with the gram-positive bacterium Lactococcus lactis. Conjugation triggered the enhanced expression of the clumping protein CluA, which is a main biofilm attribute in lactococci. Clumping transconjugants further transmitted the biofilm-forming elements among the lactococcal population at a much higher frequency than the parental nonclumping donor. This cell-clumping-associated high-frequency conjugation system also appeared to serve as an internal enhancer facilitating the dissemination of the broad-host-range drug resistance gene-encoding plasmid pAMβ1 within L. lactis, at frequencies more than 10,000 times higher than those for the nonclumping parental donor strain. The implications of this finding for antibiotic resistance gene dissemination are discussed.

Lactococci are important fermentation starter cultures. As commensal organisms, they are widely distributed (19, 37) and can be found coexisting with many other organisms, including pathogens, in natural and food-processing environments, most commonly in the form of mixed-culture ecosystems. However, to date information regarding lactococcal biofilm formation is very limited (30). The contribution of commensal organisms in mixed-culture biofilm development involving pathogens and other risks associated with these biofilms have not been fully explored.

Lactococci are susceptible to various gene transfer mechanisms (13). Many important traits, including lactose utilization, the proteolytic system, bacterial phage resistance, and nisin production and immunity, are associated with mobile elements. Of particular interest, a cell-clumping-associated high-frequency conjugal gene transfer system has been reported in two similar settings involving Lactococcus lactis strains ML3 and 712. In both cases, the conjugative elements, i.e., the sex factor in 712 and pRS01 in ML3, mobilized the transfer of the Lac plasmid to the recipient cells by forming plasmid cointegrates. Some of the conjugation progenies exhibited cell autoaggregation. When these clumping cells served as donors in the second round of mating, they transferred the Lac plasmid 102 to 107 times more efficiently than the original donor strain (1, 10, 40). Divalent ions were required for autoaggregation, and proteinase treatments significantly decreased both cell clumping (Clu+) and high-frequency conjugation (41). Strain MG1363 is a nonclumping, plasmid-cured derivative of strain 712 with the sex factor retained in the chromosome. A cluA gene, which encoded a putative cell surface protein containing the well-conserved hexapeptide LPXTGE, was cloned from the sex factor. Expression of the CluA protein through upstream fusion of a lactococcal heat shock promoter in MG1363 partially restored cell aggregation (16).

It is anticipated that the biofilm environment would be suitable for gene transfer events such as conjugation and transformation. However, a two-way relationship was recently demonstrated in Escherichia coli, showing that conjugation also served as an important mechanism for biofilm development, independent from quorum sensing (15, 31, 34). Meanwhile, bacterial surface ligand-receptor interaction-mediated cell aggregation was found to be essential in oral bacteria biofilm assembly (21, 22, 36). Therefore, it is of particular interest to see whether there is a correlation between cell aggregation, high-frequency conjugation, and biofilm formation in lactococci.

The main objective of this study was to examine the possible relationship between conjugation and biofilm development in L. lactis. Since cell aggregation-associated high-frequency conjugation systems have been reported to exist in other organisms, including Bacillus thuringiensis (3, 20), Lactobacillus plantarum (35), and Enterococcus faecalis (9), revealing such a biofilm-forming mechanism may have broader implications. A hidden risk associated with organisms carrying such inherited high-frequency conjugation systems is also discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study and their relevant characteristics are listed in Table 1. Bacterial strains were stored at 4°C and maintained by biweekly transfers in appropriate media. Lactococcal strains were grown in M17 broth containing 0.5% glucose or lactose (M17-G or M17-L, respectively; Becton Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD) as the sole carbohydrate source at 30°C. The final concentrations of antibiotics used for screening L. lactis derivatives were 500 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ), 5 μg/ml erythromycin (Fisher Scientific), and 5 μg/ml tetracycline (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO). Escherichia coli strains DH5α (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and INVαF′ (Invitrogen) were propagated in Miller LB broth (Fisher Scientific) at 37°C with aeration.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in the study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant phenotypea | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| pCRCluA | Ampr | CluA cloned in pCR2.1 | This study |

| pMSP3535 | Emr | Nisin-inducible expression vector | 5 |

| p3535CluA | Emr CluA+ | pMSP 3535 with cloned cluA, nisin inducible | This study |

| pAMβ1 | Emr | Broad-host-range drug-resistant plasmid from E. faecalis | 7 |

| L. lactis ML3 | Lac+ Clu− Strs Ems | Parental Lac+ donor | 24 |

| L. lactis MG1363 | Lac− Clu− | Plasmid-cured derivative of 712 | 12 |

| L. lactis LM2301 | Lac− Strr Ems | Plasmid-cured, Strr derivative of L. lactis strain C2 | 29 |

| L. lactis LM2302 | Lac− Strr Emr | Plasmid-cured, Emr derivative of LM2301 | 41 |

| L. lactis HW002 | Lac+ Clu+ Strr Ems | Clumping transconjugant from ML3 × LM2301 | This study |

| L. lactis HL2301A | Lac− Strr Emr | LM2301 transformed with p3535CluA | This study |

| L. lactis HL2301V | Lac− Strr Emr | LM2301 transformed with pMSP3535 | This study |

| L. lactis HL3A | Lac+ Strs Emr | ML3 transformed with p3535 CluA | This study |

| L. lactis HL3V | Lac+ Strr Emr | ML3 transformed with pMSP3535 | This study |

| L. lactis HL01Te | Lac− Strr Ems Ter | Spontaneous 2301 mutant, tetracycline resistant | This study |

| L. lactis JK2301β | Lac− Strr Emr | Transformant of LM2301 received pAMβ1 | 23 |

| L. lactis HW401 | Lac+ Strr Emr | Clumping transconjugant from HW002 × JK2301β | This study |

| L. lactis HL421 | Lac+ Strr Ter | Clumping transconjugant from HW401 × HL01Te | This study |

| L. lactis HL221 | Lac+ Strr Emr | Clumping transconjugant from HW002 × LM2302 | This study |

| L. lactis HL222 | Lac+ Strr Ter | Clumping transconjugant from HL221 × HL01Te | This study |

| L. lactis HL331 | Lac+ Strr Ter | Clumping transconjugant from HW002 × HL01Te | This study |

| L. lactis HL332 | Lac+ Strr Emr | Clumping transconjugant from HL331 × LM2302 | This study |

Clu+, ability to self-aggregate; Ampr, ampicillin resistant; Strr, streptomycin resistant; Emr, erythromycin resistant; Ter, tetracycline resistant; Lac+, ability to ferment lactose.

Mutant isolation.

The tetracycline-resistant mutant HL01Te was isolated by following the procedures described by McKay et al. (29). Basically, 5 ml of fresh M17-G broth containing 0.5 μg/ml of tetracycline was inoculated with 250 μl of an overnight culture of L. lactis LM2301 and incubated at 30°C for 2 to 3 days until growth was evident. Successive transfers were then made into M17-G broth with tetracycline concentrations of 2, 5, and 10 μg/ml, consecutively. The isolated mutant was maintained in M17-G broth containing 5 μg/ml of tetracycline.

DNA manipulation.

For bacterial genomic DNA extraction, cells were collected from 1 ml of overnight culture by microcentrifugation at 5,400 × g for 10 min. Collected cells were treated with 20 mg/ml of lysozyme (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) in enzymatic lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA, and 1.2% Triton X-100) for 45 min at 37°C. Genomic DNA was extracted using a commercial isolation kit (DNeasy Tissue Kit; QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) and eluted with 100 μl of elution buffer by following the manufacturer's instructions.

A 4,133-bp cluA fragment, including the 3,729-bp structural gene, 301 bp upstream sequence, and 103 bp downstream sequence, was amplified by conventional PCR using primer pair 5′CAGCTGTGGTTGATTTCAAC3′ and 5′GATATCAATAAGGTAATGAG 3′ and the genomic DNA from MG1363 as the template. PCR products were purified using a commercial purification kit (QIAquick; QIAGEN). Purified PCR products were cloned into the pCR 2.1 vector, and the recombinant plasmid was transformed into E. coli INVαF′ competent cells using a cloning kit (TA Cloning; Invitrogen). The recombinant plasmid pCRCluA was recovered from the ampicillin-resistant transformant. A second PCR primer pair, 5′CGCGGATCCGTCTGATAAGGCAGTTTTTTTGTTTC3′ and 5′TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG3′, was used to amplify a second 3.9-kb cluA fragment, using the above-described recombinant plasmid pCRCluA as the template. This new PCR amplicon contained the 3,729-bp cluA structural gene, 48 bp upstream sequence, and 103 bp downstream sequence from MG1363, as well as flanking sequences from the vector pCR2.1. The fragment was digested with BamHI and XbaI, cloned into pMSP3535, and electroporated into E. coli DH5α. The transformants were screened on a brain heart infusion agar plate containing 100 μg/ml of erythromycin. The recombinant plasmid pMSP3535CluA was recovered from E. coli by using a miniprep kit (QIAprep; QIAGEN). The DNA sequence of the cloned cluA gene was partially confirmed using a DNA analyzer (ABI PRISM 3700; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) at the Plant Genome Sequence Facility of the Ohio State University. The recombinant plasmid pMSP3535CluA and the vector pMSP3535 were electroporated into L. lactis strains by following the procedures described previously (42).

Expression of CluA.

Nisin stock solutions were prepared by dissolving nisin (2.5% [wt/wt] in milk solids) (Sigma-Aldrich Co., catalog number N-5764-5G) in sterilized, distilled water to a final concentration of 4 μg/ml nisin. The stock solution was stored at 4°C for up to 1 week. M17 broth supplemented with 5 μg/ml of erythromycin and appropriate carbohydrate was inoculated with an overnight culture of HL2301A or HL3A (5% of the final volume) and incubated at 30°C for 3 h. To induce CluA expression, nisin stock solution was added to the above-described cultures to a final nisin concentration of 25 ng/ml. The cultures were then incubated at 30°C for an additional 15 h (making the total incubation time 18 h) for cell aggregation observation or for an additional 33 h (making the total incubation time 36 h) for microtiter plate attachment assay, confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis. L. lactis strains HL2301V and HL3V were used as vector controls following the nisin induction procedures as described above. Furthermore, a parallel set of HL2301A and HL3A were incubated as CluA expression controls under the same conditions for the same period of time, except without adding nisin for induction.

RT-PCR.

Five milliliters of M17-G or M17-L broth was inoculated with 250 μl of the overnight L. lactis cultures and incubated at 30°C for 6 h until the optical density at 600 nm reached 0.8. RNA was extracted from 0.5 ml of such cultures by using a commercial RNA extraction kit (RNeasy; QIAGEN). RNA was eluted with 50 μl of RNase-free water and treated with amplification-grade DNase I (Invitrogen), following the instructions from the manufacturers. The pair of primers 5′ATGAAAAAAACATTGAGAGACCAG3′ and 5′AAGTCCTGTCATTCCGTCG3′ amplified a 636-bp fragment of the cluA gene (GenBank accession number U04468). The expression of the L. lactis ribosomal protein L4 (GenBank accession number AE006438) was included as an internal standard. The primer pairs 5′CATGGCGTCAAAAAGG3′ and 5′TGCAAGAACCTCCTC3′ amplified a 434-bp region of the rl4 gene. The 50-μl reaction mixture in the setup for reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) contained 25 μl of 2× SuperScript one-step RT-PCR buffer (a buffer containing 0.4 mM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate and 2.4 mM MgSO4 [Invitrogen]), 0.2 μM of each of the four primers, 1 μl of SuperScript II RT/Platinum Taq mix (Invitrogen), and 5 μl of the treated RNA sample. The RT-PCR cycling conditions and product gel electrophoresis were according to standard procedures. The gel image was captured using a Bio-Rad Quantity One Gel Doc system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Two units of Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) instead of the RT/Platinum Taq mix were used in the RT-PCR controls to ensure the absence of DNA contamination.

Cell aggregation.

To aid in visualization of aggregation, cells from 10 ml of overnight culture of L. lactis strains with or without nisin induction were collected by centrifugation at 4,300 × g for 10 min. The cell pellets were resuspended in the same volume of 0.85% saline and vortexed at maximum speed for 1 min. Nonclumping strains formed uniform solutions after resuspension. Within minutes, clumping strains formed aggregates that could be observed visually.

Biofilm cultivation and evaluation.

A rapid microtiter plate adherence test (8) was conducted with modification to measure bacterial attachment on the surface. Each well, containing 2 ml of appropriate M17 broth (24-well microtiter plate; Becton Dickinson and Company), was inoculated with 100 μl of an overnight L. lactis culture and incubated at 30°C for 36 h. After incubation, 500 μl of 0.21% crystal violet staining solution (Fisher Diagnostic, Middletown, PA) was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Microtiter plate wells were rinsed with 2 ml distilled water to remove unattached cells and residual dye. The images of attached cells were captured with a Bio-Rad Quantity One Gel Doc system.

CLSM was used to examine the biofilm-forming potentials of L. lactis strains on Lab-Tek Permanox plastic chamber slides (Nalgene Nunc International Corp., Naperville, IL). Each chamber was filled with 1 ml of either M17-G or M17-L broth with appropriate antibiotics and was inoculated with 50 μl of an overnight L. lactis culture. The slide was incubated at 30°C for 36 h in the presence or absence of nisin. A chamber containing 1 ml of uninoculated broth was used as a medium control. Unattached cells and culture medium were washed off using 2 ml phosphate-buffered saline (containing, per liter, 8 g NaCl, 0.2 g KCl, 1.44 g Na2HPO4, 0.24 g KH2PO4, pH 7.4) after the incubation. Surface-attached cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 20 min at 4°C and then stained with 0.01% acridine orange (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) for 10 min at room temperature. The acridine orange was poured off, and excess stain was removed by washing the slides one time with 2 ml phosphate-buffered saline. After slides were mounted with coverslips, samples were observed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (model LSM 510 META; Carl Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, NY). A Hene1 laser at 543 nm was used for excitation, and Long Path LP560 nm was used for an emission filter. The biofilms were examined with a 63× oil immersion objective lens, and the images were collected and analyzed using the packaged LSM 510 imaging software.

SEM was used to observe L. lactis biofilm structures. Lactococcal biofilms were cultivated by inoculating 100 μl of an overnight L. lactis culture into 2 ml of M17-G or M17-L broth per well in 24-well microtiter plates (Becton Dickinson and Company) and incubating at 30°C in the presence or absence of nisin. SEM sample preparation was conducted based on procedures as described by Li et al. (26) and Marsh et al. (27) with modification. Basically, biofilms formed on the surfaces of the microtiter plate wells were washed once with 2 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (containing, per liter, 8 g NaCl, 0.2 g KCl, 1.44 g Na2HPO4, 0.24 g KH2PO4, pH 7.4) and fixed with 2 ml of 3.7% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 24 h at room temperature. The samples were then dehydrated with a graded 100% ethanol:hexamethyldisilazane (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, CA) series (3:1 for 15 min, 1:1 for 15 min, 1:3 for 15 min, and 100% hexamethyldisilazane three times for 15 min each) and left covered by hexamethyldisilazane to dehydrate overnight. After dehydration, the bottom surface of the well was cut off, mounted, and sputter coated for 180 s with gold palladium (Pelco model 3 sputter coater; Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, CA). Samples were observed using a scanning electron microscope (FEI XL30; FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR). Images were captured at low magnification for biofilm network overview and at high magnification to show detailed biofilm structure.

Conjugal matings.

Conjugal matings were performed using the direct plating method described previously, with modification (41). Cells from 1.7 ml of 18-h cultures, including strains HL2301V, HL2301A, HL3V, and HL3A with nisin induction and HL2301 and HL3A without nisin induction, were harvested by centrifugation at 5,400 × g for 5 min. The cell pellets were resuspended in 5 ml of fresh medium and inoculated for 1.5 h at 30°C before harvesting. For the rest of the strains, 0.1 ml of an overnight culture was inoculated into 5 ml of M17 broth and incubated at 30°C for 4 h (optical density at 600 nm of around 0.6, approximately 108 to 109 CFU/ml). Cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 4,300 × g for 10 min and resuspended in 0.5 ml of saline. Donor and recipient cells were mixed at a 1:2 ratio, and 0.2 ml of the cell mixture or its dilution was plated directly on BCP-lactose indicator agar (28) that contained 500 μg/ml of streptomycin sulfate, 5 μg/ml of erythromycin, or 5 μg/ml of tetracycline. Lactose-positive transconjugants were verified by phenotypic characterization. BCP-glucose indicator agar that contained 5 μg/ml of erythromycin and 5 μg/ml of tetracycline was used to screen for transconjugants containing pAMβ1, using HW401 as donor and HL01Te as recipient. Transfer frequencies were expressed as the number of transconjugants per CFU of the donor, and the values reported are the mean values from three separate experiments.

RESULTS

Involvement of conjugation in lactococcal biofilm development.

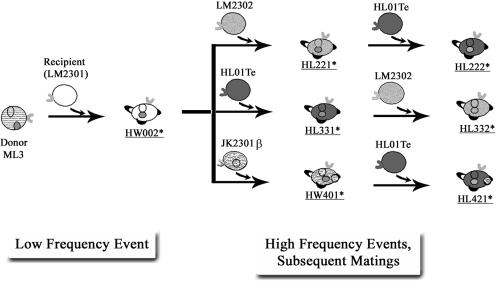

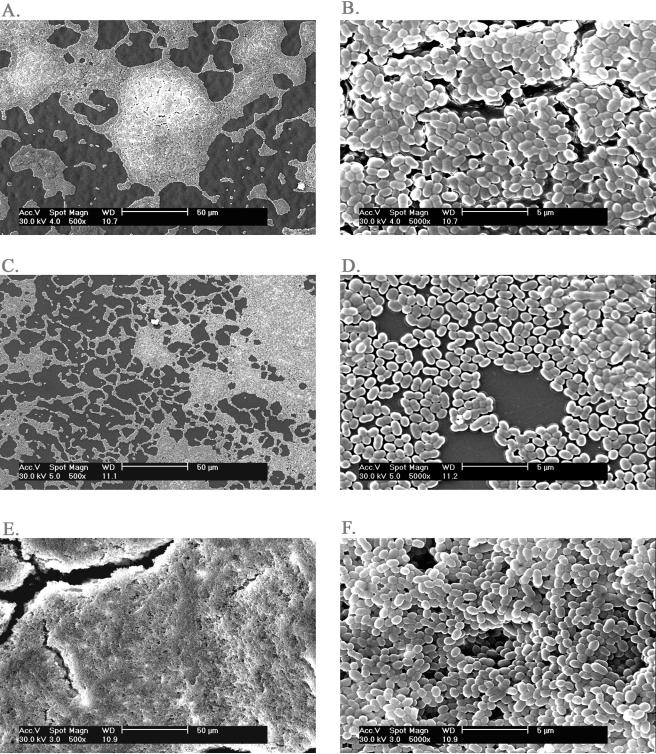

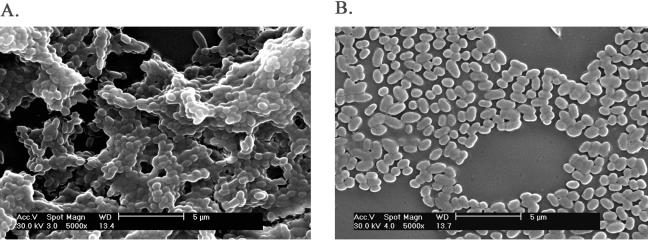

The transmission of Lac plasmid among L. lactis strains is illustrated in Fig. 1. Biofilm formations by the initial donor ML3, the recipient LM2301, and the Clu+ transconjugant HW002 were examined. The Clu+ strain HW002 was found to be more efficient in forming biofilms than both the nonclumping donor ML3 and the recipient LM2301. A thick, three-dimensional biofilm structure formed by the Clu+ strain HW002, after 36 h of incubation at 30°C, was evident by SEM. However, under the same conditions, the parental strains ML3 and LM2301 developed attachment only on limited surface areas, with mostly single layer of cells (Fig. 2A to F). In the subsequent matings, the plasmids were transferred from HW002 to various lactococcal recipients at high frequencies (Fig. 1). The majority of these transconjugants exhibited the Clu+ phenotype. As expected, clumping strains HL221, HL331, HW401, HL421, HL332, and HL222 all exhibited enhanced biofilm-forming ability (Fig. 3). These results indicated that cell aggregation and enhanced biofilm formation were correlated in L. lactis and that these phenotypes were transferable by conjugation. The Clu+ strains could transfer the plasmids at frequencies 102 to 107 times higher than for the nonclumping donor and were therefore much more efficient in disseminating the biofilm-forming attributes among the population than was the initial parental strain.

FIG. 1.

Conjugal transfer of the Lac plasmid among L. lactis strains. Asterisks indicate clumping transconjugants that served as “super donors,” transferring the Lac plasmid at 10−2 to 10−3 transconjugants/donor CFU in subsequent matings.

FIG. 2.

SEM pictures of 36-h biofilms formed by L. lactis strains involved in conjugation. A: Overview of the biofilm formed by the donor strain ML3. B: Regional magnification of A showing biofilm details. C: Overview of the biofilm formed by the recipient strain LM2301. D: Regional magnification of C showing biofilm details. E: Overview of the biofilm formed by the clumping transconjugant HW002. F: Regional magnification of E showing biofilm details. The bars in A, C, and E represent 50 μm; the bars in B, D, and F represent 5 μm.

FIG. 3.

Biofilm formation and conjugal transfer of enhanced biofilm-forming phenotype by L. lactis clumping strains, using the rapid microtiter plate adherence test. ML3 was the initial donor for the Lac plasmid. LM2301, JK2301β, LM2302, and HL01Te were conjugation recipients. HW002, HL221, HL331, and HW401 were clumping transconjugants, and they also served as donors for the Lac plasmid in the subsequent matings. HL421, HL332, and HL222 were clumping transconjugants.

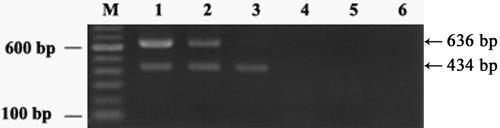

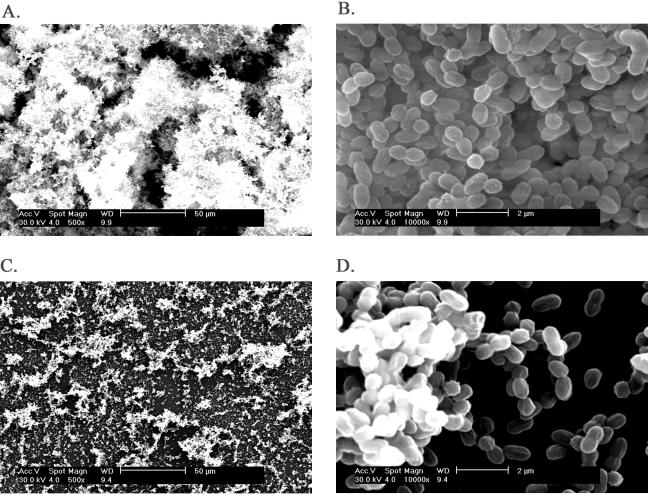

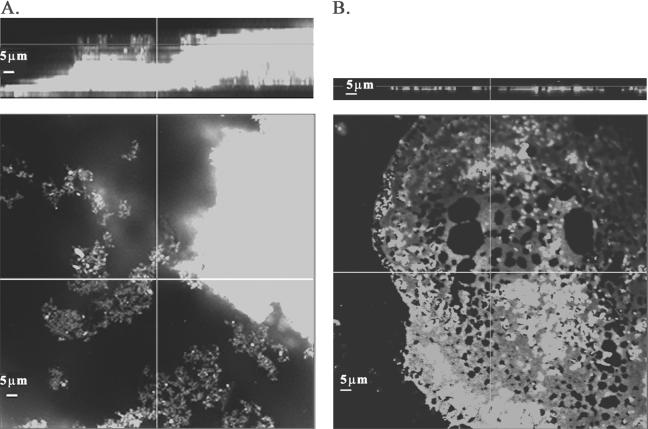

While ML3 contained multiple plasmids and was the donor for the Lac plasmid pSK08 and the conjugative plasmid pRS01 in the conjugal mating, it was a much slower biofilm former and did not exhibit cell clumping. A logical interpretation would be that the plasmid recombination event during cointegrate formation triggered the expression of a certain protein(s) which was involved in biofilm development. To test this hypothesis, the expressions of CluA in ML3, LM2301, and the clumping transconjugant HW002 were compared. As expected, the transcription of the cluA gene in HW002 was found to be much higher than that in ML3, and no transcription was observed in the plasmid-cured recipient strain LM2301 by RT-PCR (Fig. 4). To further confirm the role of CluA in lactococcal biofilm formation, the cluA gene was cloned into the expression vector pMSP3535, downstream of the nisA promoter. The expression of CluA protein was induced by an external nisin signal and confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (data not shown). Strains HL3A and HL2301A both exhibited cell aggregation with nisin induction. SEM showed that both strains also exhibited enhanced biofilm formation with nisin induction rather than without nisin induction (Fig. 5 and 6). The biofilm formed by CluA-expressing HL3A with nisin induction was seven to eight times thicker than that formed by the same strain without induction (Fig. 7). However, although clumping strain HL2301A developed a localized biofilm structure with nisin induction, which was absent in the same strain without the inducer (Fig. 6A and B), its structure was much less complex than that of the clumping strains HL3A (Fig. 5A and B) and HW002 (Fig. 2E and F). These results suggested that CluA was the clumping factor as well as a key biofilm determinant. Increased expression of CluA facilitated biofilm formation, which was triggered by the conjugation event in L. lactis. Nevertheless, ML3 might carry an additional plasmid-encoded element(s), other than CluA, which also contributed to biofilm structure development.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of CluA expression in L. lactis strains by RT-PCR. Lane M: 100-bp DNA ladder. Lane 1: HW002. Lane 2: ML3. Lane 3: LM2301. Lane 4 through 6: DNA amplification controls using the same RNA samples of HW002, ML3, and LM2301, respectively, but without reverse transcriptase. The arrows indicate the positions of the 434-bp internal standard rl4 gene amplicons and the 636-bp cluA gene amplification products.

FIG. 5.

SEM pictures of biofilm formation by L. lactis HL3A. A: With nisin induction. B: Regional magnification of A showing biofilm details. C: Without nisin induction. D: Regional magnification of C showing attachment details. The bars in A and C represent 50 μm, and those in B and D represent 2 μm.

FIG. 6.

SEM pictures of biofilm formation by L. lactis HL2301A. A: With nisin induction. B: Without nisin induction. The bars represent 5 μm.

FIG. 7.

CLSM pictures of biofilm formation by L. lactis HL3A. A: With nisin induction. B: Without nisin induction. Top panels are the xz plane, and bottom panels are the xy plane. The bars represent 5 μm.

Role of CluA in conjugal gene transfer.

It was anticipated that the high-frequency conjugal gene transfer ability illustrated by Clu+ strains, such as HW002, was largely due to the close proximity between the donor and recipient cells within cell aggregates. Therefore, experiments were conducted to examine the role of CluA expression in conjugal gene transfer by using the direct plate conjugation method. The expression of CluA was induced in either donor or recipient, and the frequencies of conjugal transfer of the Lac plasmid were compared. As illustrated in Table 2, the frequency of conjugation between the nonclumping donor ML3 and the clumping recipient HL2301A with nisin induction was significantly higher than the frequency in the control setting without nisin induction (P < 0.05); the difference between the mean values was about threefold. Likewise, the frequency of conjugation between the clumping donor HL3A with nisin induction and LM2301 was significantly higher than that in the control setting without nisin induction (P < 0.05); the difference in mean values was about eightfold. These results suggested that the expression of CluA enhanced the conjugal gene transfer event, regardless of whether the CluA expression was associated with donor or recipient. However, induced expression of CluA in donor or recipient did not restore high-frequency conjugation (102 to 107 times higher than that of the parental strain) exhibited by some of the clumping transconjugants. The contribution of cell aggregation to high-frequency conjugation was rather limited, indicating the involvement of an additional factor(s) in such high-frequency conjugal gene transfer events. This is in agreement with a proposed conjugal gene transfer model in which at least two protein complexes are required, involving DNA preparation and mating-pair formation (18). The lactococcal inherited system should carry all the essential elements required for high-frequency gene transfer. CluA is likely involved in mating-pair formation.

TABLE 2.

Lactococcus lactis conjugal matinga

| Set | Donor | Recipient | Nisin induction | Conjugation frequencyb | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | ML3 | LM2301 | 1.5 × 10−8 ± 6 × 10−9 | Original setting | |

| B | HW002 | LM2302 | 2.5 × 10−2 ± 7 × 10−3 | “Super donor I” | |

| C | ML3 | HL2301A | Yes | 7.2 × 10−8 ± 2.9 × 10−8 | CluA induced in recipient |

| D | ML3 | HL2301A | No | 2.1 × 10−8 ± 1.9 × 10−8 | Control without CluA induction |

| E | ML3 | HL2301V | Yes | 2.6 × 10−8 ± 1.8 × 10−8 | Control with cloning vector only |

| F | HL3A | LM2301 | Yes | 3.3 × 10−7 ± 2.0 × 10−7 | CluA induced in donor |

| G | HL3A | LM2301 | No | 4.3 × 10−8 ± 2.2 × 10−8 | Control without CluA induction |

| H | HL3V | LM2301 | Yes | 2.7 × 10−8 ± 1.1 × 10−8 | Control with cloning vector only |

All strains are derivatives of ML3 and C2, and therefore all contain the Agg factor.

Values for conjugation frequency are means of three replicates ± standard deviations.

Facilitated transfer of pAMβ1 by the lactococcal high-frequency conjugation system.

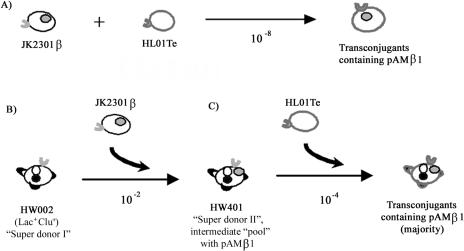

While the lactococcal high-frequency conjugation system was known for the transfer of beneficial fermentation traits, its potential involvement in antibiotic resistance gene transmission was investigated. As illustrated in Fig. 1, HW002 served as a “super donor,” transferring the Lac plasmid in the second round of mating at frequencies of up to 10−2 transconjugants per donor CFU, which is about 106 times more efficient than transfer by the parental strain. Although the major contributor(s) for the high-frequency conjugation system is yet to be identified, the potential role of such an intrinsic mechanism in transmitting the antibiotic resistance genes was examined (Fig. 8). The direct transfer of pAMβ1 from the donor strain JK2301β to the recipient HL01Te was a low-efficiency event (Fig. 8A). However, when JK2301β mated with HW002, a pool of clumping “super donor II” transconjugants containing pAMβ1 was generated at 10−2 transconjugants/donor CFU (Fig. 8B). These “super donor II” cells (HW401-like) further transferred pAMβ1 to the HL01Te at frequencies 10,000 times higher than those with the original donor JK2301β (Fig. 8C).

FIG. 8.

Conjugal transfer of plasmid pAMβ1 among L. lactis strains. A: JK2301β transferred the plasmid pAMβ1 to the recipient HL01Te at a frequency of 10−8 transconjugants/donor CFU. B: Conjugation between JK2301β and the clumping strain HW002 generated the clumping, Lac+ Emr transconjugants (HW401-like) at a frequency of 10−2 transconjugants/donor CFU. C: HW401 transferred pAMβ1 to HL01Te at a frequency of 10−4 transconjugants/donor CFU.

DISCUSSION

The relationship between gene transfer and biofilm is of great interest to the scientific community. In this study, we have demonstrated that in L. lactis, the sex factor-encoded cell surface component CluA is the key factor in cell aggregation and biofilm development; enhanced expression of CluA and the subsequently facilitated biofilm formation are the direct result of a conjugation event. Furthermore, this enhanced biofilm-forming trait is transmissible by conjugation. Evidence in the past showed that gene transfer might be facilitated in cell clumps or in the biofilm environment through a better donor-recipient interaction. Our study is significant because it illustrates a new relationship between conjugation and biofilms in gram-positive bacteria: gene transfer events such as conjugation further enable these organisms to disseminate biofilm attributes effectively within the community to enhance the ecosystem development. This result is consistent with the discovery that conjugation in E. coli is an independent mechanism for biofilm development.

It is anticipated that cell clumping is directly correlated to high-frequency conjugation. However, while nisin-induced expression of CluA, in either donor or recipient, increased the conjugation frequency, the scale of improvement was much less than expected. Conjugation frequencies with mating sets C and F (Table 2) clearly showed that cell clumping is not the major contributor for high-frequency gene transfer in lactococci. Limited biofilm enhancement by strain HL2301A with nisin induction further suggested that another plasmid-encoded factor(s) was involved in facilitating the development of a well-connected biofilm network, as exhibited by the clumping strains (Fig. 2E and F). Characterization of these additional factors involved in both the high-frequency conjugal gene transfer and enhanced biofilm formation is currently under way.

Increased pathogen resistance to antibiotic treatment is a major threat to human health. The roles of commensals, especially food-borne microbes, in transmitting resistance genes are becoming a concern to the scientific community (2). In the past, various mobile elements encoding antibiotic resistance determinants had been identified and characterized in both food-borne pathogens and commensals isolated from foods, animals, and humans (4, 6, 14, 17, 25, 32). These data suggest that food can be an important carrier introducing antibiotic resistance genes into humans and that antibiotic-resistant pathogens and commensals have emerged in the food chain. However, the picture is still incomplete.

The broad-host-range, erythromycin resistance gene-carrying plasmid pAMβ1 was initially identified in E. faecalis (7). The transmission of this plasmid between E. faecalis, L. lactis, and Lactobacillus strains by conjugation was documented (11, 33, 38, 39). Therefore, monitoring the transfer of this plasmid in ecosystems has practical implications for understanding the transmission of antibiotic resistance genes among commensals and pathogens.

In this study, using L. lactis as a model organism, we have demonstrated two concepts: first, a pool of clumping lactococcal progenies with the broad-host-range, erythromycin resistance gene-carrying plasmid pAMβ1 can be generated very efficiently by strains carrying the intrinsic high-frequency conjugation mechanism (Fig. 8B); second, this inherited mechanism, previously known for the transfer of fermentation traits such as lactose utilization and the proteolytic system, can serve as an enhancer facilitating the subsequent transfer of pAMβ1 among lactococcal populations (Fig. 8C). Therefore, we have demonstrated not only that organisms carrying such intrinsic mechanisms have the potential to become an important reservoir for antibiotic resistance genes but, more importantly, that these intermediate organisms can disseminate antibiotic resistance genes (at least pAMβ1) in subsequent events much more effectively than the parental donor strain. Currently, these concepts are illustrated in lactococci, which are found mostly in the dairy fermentation environment. However, inherited high-frequency conjugation systems have also been reported to occur in several other bacteria, including lactobacilli, enterococci, and bacilli, which are commonly found in food production and processing environments, as well as in animal and human host ecosystems. Some of these organisms are consumed in large quantities as probiotics, and screening for the presence of inherited gene transfer mechanisms is not routinely conducted. It is therefore of great interest to investigate whether such “enhancing” mechanisms also function similarly in these organisms and what kind of roles these organisms, particularly commensals, could have played in disseminating antibiotic resistance and other microbial “survival-friendly” genes in both the environment and hosts.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Gary Dunny (University of Minnesota) and Lauren Bakenlaz, John Reeve, and Ahmed Yousef (The Ohio State University) for helpful discussions. Gary Dunny also kindly provided pMSP3535. L. lactis strains ML3, LM2301, LM2302, and JK2301β were from Larry McKay (University of Minnesota). We also thank Brian Kemmenoe and Kathy Wolken from the Campus Microscopy and Imaging Facility at The Ohio State University for assisting with the microscopy study.

This project was sponsored by OARDC seed grant 2002-012 and OSU startup funds for H. H. Wang.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, D. G., and L. L. McKay. 1984. Genetic and physical characterization of recombinant plasmids associated with cell aggregation and high-frequency conjugal transfer in Streptococcus lactis ML3. J. Bacteriol. 158:954-962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andremont, A. 2003. Commensal flora may play key role in spreading antibiotic resistance. ASM News 69:601-607. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrup, L., J. Damgaard, and K. Wassermann. 1993. Mobilization of small plasmids in Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis is accompanied by specific aggregation. J. Bacteriol. 175:6530-6536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blake, D. P., K. Hillman, D. R. Fenlon, and J. C. Low. 2003. Transfer of antibiotic resistance between commensal and pathogenic members of the Enterobacteriaceae under ileal conditions. J. Appl. Microbiol. 95:428-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryan, E. M., T. Bae, M. Kleerebezem, and G. M. Dunny. 2000. Improved vectors for nisin-controlled expression in gram-positive bacteria. Plasmid 44:183-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, S., S. Zhao, D. G. White, C. M. Schroeder, R. Lu, H. Yang, P. F. McDermott, S. Ayers, and J. Meng. 2004. Characterization of multiple-antimicrobial-resistant Salmonella serovars isolated from retail meats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clewell, D. B., Y. Yagi, G. M. Dunny, and S. K. Schultz. 1974. Characterization of three plasmid deoxyribonucleic acid molecules in a strain of Streptococcus faecalis: identification of a plasmid determining erythromycin resistance. J. Bacteriol. 117:283-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deighton, M. A., J. Capstick, E. Domalewski, and T. van Nguyen. 2001. Methods for studying biofilms produced by Staphylococcus epidermidis. Methods Enzymol. 336:177-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunny, G. M., B. L. Brown, and D. B. Clewell. 1978. Induced cell aggregation and mating in Streptococcus faecalis: evidence for a bacterial sex pheromone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 75:3479-3483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gasson, M. J., and F. L. Davies. 1980. High-frequency conjugation associated with Streptococcus lactis donor cell aggregation. J. Bacteriol. 143:1260-1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gasson, M. J., and F. L. Davies. 1980. Conjugal transfer of the drug resistance plasmid pAMβ1 in the lactic streptococci. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 7:51-53. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gasson, M. J. 1983. Plasmid complements of Streptococcus lactis NCDO 712 and other lactic streptococci after protoplast-induced curing. J. Bacteriol. 154:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gasson, M. J. 1990. In vivo genetic systems in lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 87:43-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gevers, D., G. Huys, and J. Swings. 2003. In vitro conjugal transfer of tetracycline resistance from Lactobacillus isolates to other Gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 225:125-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghigo, J. M. 2001. Natural conjugative plasmids induce bacterial biofilm development. Nature 412:442-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Godon, J. J., K. Jury, C. A. Shearman, and M. J. Gasson. 1994. The Lactococcus lactis sex-factor aggregation gene cluA. Mol. Microbiol. 12:655-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein, C., M. D. Lee, S. Sanchez, C. Hudson, B. Phillips, B. Register, M. Grady, C. Liebert, A. O. Summers, D. G. White, and J. J. Maurer. 2001. Incidence of class 1 and 2 integrases in clinical and commensal bacteria from livestock, companion animals, and exotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:723-726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grohmann, E., G. Muth, and M. Espinosa. 2003. Conjugative plasmid transfer in gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:277-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heilig, H. G., E. G. Zoetendal, E. E. Vaughan, P. Marteau, A. D. Akkermans, and W. M. de Vos. 2002. Molecular diversity of Lactobacillus spp. and other lactic acid bacteria in the human intestine as determined by specific amplification of 16S ribosomal DNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:114-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen, G. B., A. Wilcks, S. S. Petersen, J. Damgaad, J. S. Baum, and L. Andrup. 1995. The genetic basis of the aggregation system in Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis is located on the large conjugative plasmid pXO16. J. Bacteriol. 177:2914-2917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolenbrander, P. E. 1988. Intergeneric coaggregation among human oral bacteria and ecology of dental plaque. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 42:627-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kolenbrander, P. E. 2000. Oral microbial communities: biofilms, interactions, and genetic systems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:413-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kondo, J. K., and L. L. McKay. 1984. Plasmid transformation of Streptococcus lactis protoplasts: optimization and use in molecular cloning. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 48:252-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuhl, S. A., L. D. Larsen, and L. L. Mckay. 1979. Plasmid profiles of lactose-negative and proteinase-deficient mutants of Streptococcus lactis C10, ML3, and M18. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 37:1193-1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levy, S. B., G. B. FitzGerald, and A. B. Macone. 1976. Spread of antibiotic-resistant plasmids from chicken to chicken and from chicken to man. Nature 260:40-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, Y. H., P. C. Y. Lau, J. H. Lee, R. P. Ellen, and D. G. Cvitkovitch. 2001. Natural genetic transformation of Streptococcus mutans growing in biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 183:897-908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marsh, E. J., H. Luo, and H. Wang. 2003. A three-tiered approach to differentiate Listeria monocytogenes biofilm-forming abilities. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 228:203-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKay, L. L., K. A. Baldwin, and E. A. Zottola. 1972. Loss of lactose metabolism in lactic streptococci. Appl. Microbiol. 23:1090-1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKay, L. L., K. A. Baldwin, and P. M. Walsh. 1980. Conjugal transfer of genetic information in group N streptococci. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 40:84-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mercier, C., C. Durrieu, R. Briandet, E. Domakova, J. Tremblay, G. Buist, and S. Kulakauskas. 2002. Positive role of peptidoglycan breaks in lactococcal biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 46:235-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molin, S., and T. Tolker-Nielsen. 2003. Gene transfer occurs with enhanced efficiency in biofilms and induces enhanced stabilisation of the biofilm structure. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 14:255-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nandi, S., J. J. Maurer, C. Hofacre, and A. O. Summers. 2004. Gram-positive bacteria are a major reservoir of class 1 antibiotic resistance integrons in poultry litter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:7118-7122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pucci, M. J., M. E. Monteschio, and C. L. Kemker. 1988. Intergeneric and intrageneric conjugal transfer of plasmid-encoded antibiotic resistance determinants in Leuconostoc spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:281-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reisner, A., J. A. Haagensen, M. A. Schembri, E. L. Zechner, and S. Molin. 2003. Development and maturation of Escherichia coli K-12 biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 48:933-946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reniero, R., P. Cocconcell, P., V. Bottazzi, and L. Morelli. 1992. High frequency of conjugation in Lactobacillus mediated by an aggregation-promoting factor. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138:763-768. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rickard, A. H., P. Gilbert, N. J. High, P. E. Kolenbrander, and P. S. Handley. 2003. Bacterial coaggregation: an integral process in the development of multi-species biofilms. Trends Microbiol. 11:94-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salama, M. S., W. E. Sandine, and S. J. Giovannoni. 1993. Isolation of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris from nature by colony hybridization with rRNA probes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:3941-3945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tannock, G. W. 1987. Conjugal transfer of plasmid pAMbeta1 in Lactobacillus reuteri and between lactobacilli and Enterococcus faecalis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53:2693-2695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vescovo, M., L. Morelli, V. Bottazzi, and M. J. Gasson. 1983. Conjugal transfer of broad-host-range plasmid pAMβ1 into enteric species of lactic acid bacteria. Appl. Envrion. Micrbiol. 46:753-755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walsh, P. M., and L. L. McKay. 1981. Recombinant plasmid-associated cell aggregation and high-frequency conjugation of Streptococcus lactis ML3. J. Bacteriol. 146:937-944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, H., J. R. Broadbent, and J. K. Kondo. 1994. Analysis of the physical and functional characteristics of cell clumping in lactose positive transconjugants of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis ML3. J. Dairy Sci. 77:375-384. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, H., K. Baldwin, D. J. O'Sullivan, and L. L. McKay. 2000. Identification, gene cloning, nucleotide sequencing, and expression of pyruvate carboxylase in fast milk coagulating Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis C2. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1223-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]