Abstract

The effects of nine common food industry stresses on the times to the turbidity (Td) distribution of Listeria monocytogenes were determined. It was established that the main source of the variability of Td for stressed cells was the variability of individual lag times. The distributions of Td revealed that there was a noticeable difference in response to the stresses encountered by the L. monocytogenes cells. The applied stresses led to significant changes of the shape, the mean, and the variance of the distributions. The variance of Td of wells inoculated with single cells issued from a culture in the exponential growth phase was multiplied by at least 6 and up to 355 for wells inoculated with stressed cells. These results suggest stress-induced variability may be important in determining the reliability of predictive microbiological models.

Listeria monocytogenes has been recognized as an important food-borne pathogen that causes listeriosis. Outbreaks of listeriosis have been associated with milk, cheese, vegetables and salads, and meat products. The organism is particularly problematic for the food industry because it is widespread in the environment (17) and because of its ability to grow within a wide range of temperatures (−1.5 to 45°C), pH values (4.39 to 9.4), and osmotic pressures (NaCl concentrations up to 10%).

So, extensive research was carried out on predictive models describing the behavior of this pathogen in foods. Today, the models describing the environment effect on growth rate of L. monocytogenes are sufficiently accurate to be used by manufacturers, regulators, and scientists to assess microbial risks associated with the consumption of foods or to evaluate the relevance of risk management options (1, 2). On the other hand, the models describing the lag time must be improved to make the prediction more reliable (22, 29).

Some secondary models have been published to describe the influence of the environment on the bacterial lag time (5, 14, 41). Many reviews and discussions concerning their applicability have been published (28, 32, 35, 38). But the prediction of the lag time in foods still seems difficult to obtain and it is necessary to improve predictions (20, 37). As natural contaminations of foods occur with very few cells which are occasionally stressed by the food processing and the industry environment, it is essential to improve models by taking into account injuries encountered by the cells before they contaminate the foods and by using a stochastic approach dealing with the variability of the individual behavior of microbial cells. Models have been developed to take the effect of injuries on the bacterial lag times into account (11, 12, 39). Similarly, the individual response was also tackled by some authors such as Baranyi (6), who showed the relationship between the individual lag time distributions and the lag time of the bacterial population. Recently, some individual lag time distributions have been characterized (23, 33). The variability of individual lag times seems to be wider as microorganisms are injured (4, 33, 34, 39) or as growth conditions are unfavorable (23, 24, 27).

The aim of this study was to investigate and to compare the impacts of nine stresses usually met in the food industry on the distributions of individual lag times of L. monocytogenes. For this, the distributions of times to the turbidity (Td) of microplate wells inoculated with single L. monocytogenes cells previously subjected to stress were characterized in optimal growth conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

L. monocytogenes 14 (serotype 4b, industrial environment origin) was maintained at −25°C in 50% glycerol. The strain 14 is a reference strain of the French program in predictive microbiology Sym'Previus. Prior to each experiment, a culture was incubated at 30°C for 24 h in tryptone soy broth (Oxoid, Unipath Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom) supplemented with 0.6% yeast extract (AES Laboratoire, Combourg, France) (TSBye). The first bacterial culture was diluted as needed to obtain an initial bacterial suspension of approximately 103 cells ml−1 in TSBye. That initial bacterial concentration was further incubated in TSBye for 20 h at 25°C to obtain 108 cells ml−1 in the exponential growth phase.

Stress experiments.

Nine different stresses were applied on cultures in the exponential growth phase. First, before each stress, once TSBye had been eliminated by centrifugation (5,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C), L. monocytogenes cells were washed in 0.85% of NaCl (Prolabo, Paris, France) (diluent) at 25°C, pH 7, and centrifuged again (5,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C). Centrifugation did not have any influence on the individual lag time distribution of L. monocytogenes cells in the exponential growth phase (data not shown); this stage did not modify the physiological state of the cells. Secondly, the supernatant was eliminated and cells were recovered in the following conditions: (i) for mineral acid stress, in diluent at 25°C adjusted to pH 3 with HCl (Prolabo) for 34 min; (ii) for organic acid stress, in diluent at 25°C adjusted to pH 4.6 with lactic acid (Prolabo) for 48 h; (iii) for alkali stress, in diluent at 25°C adjusted to pH 12 with NaOH (Prolabo) for 22 min; (iv) for the first disinfectant stress, in diluent at 25°C supplemented with 4 mg liter−1 of benzalkonium chloride (BAC) (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) for 13 min; (v) for the second one, in diluent at 25°C supplemented with chlorine at 2.4 ppm for 1.5 min; (vi) for cold stress, in diluent dispatched in 1-ml aliquots directly placed at −25°C for 48 h; (vii) for heat stress, in diluent then diluted (1:100) in physiologic water at 55°C for 3 min; (viii) for osmotic stress, in pH 7 salt solution at 25% (wt/vol) at 25°C for 25 h; and (ix) for starvation stress, a second washing was realized in diluent to ensure the complete elimination of nutrient and the cells were recovered in diluent at 30°C for 24 h. The time of exposure to each stress was the necessary time to obtain a 1.5 log10 CFU ml−1 loss by enumeration on tryptone soy agar (Oxoid, Unipath Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom) supplemented with yeast extract at 0.6 g liter−1 (AES Laboratoire) (TSAye). The loss of 1.5 log10 CFU ml−1 was chosen because of the shape of the inactivation curve observed for the starvation stress. For this stress, a more significant loss would have been more difficult to achieve. This loss of cultivability also presented the advantage of being significantly higher than the error of the viable count enumeration method.

Bioscreen growth experiments.

Turbidity growth curves were generated with an automatic Bioscreen C (Labsystem France SA, Les Ulis, France) reader. From L. monocytogenes cells in the exponential growth phase and stressed cells, serial dilutions were made in tryptone salt (Oxoid) broth in order to reach in the final dilution a maximum concentration of 1.4 cells ml−1 in TSBye preheated at 30°C. Wells of two Bioscreen plates were inoculated with 300 μl of this suspension to obtain a target value of 0.42 cells well−1, increasing the probability of having one cell in wells showing growth. Assuming a Poisson distribution of the cells in the wells (18), the maximum concentration of 0.42 cells well−1 corresponds to a maximum of 35% of wells showing growth and allowed us to say that less than 20% of these wells contained more than one cell. Then the plates were placed in the Bioscreen C reader at the incubation temperature of 30°C. The increase in turbidity was monitored at 600 nm (optical density [OD]). Measurements were taken every 10 min, and the plates were shaken at the medium intensity for 30 s/min. For each stress experiment, 150 wells were kept for stressed cells, and the 50 left over were dedicated to L. monocytogenes cells in the exponential growth phase. Each experiment was replicated at least three times.

Relation between turbidity growth curves and individual lag times.

The individual lag times of L. monocytogenes cells were estimated through the time of detection (Td), which is the time required for the microbial population to generate a 0.05 increase of the initial baseline value of OD (OD0). This optical density corresponds to a cell density estimated by a viable count of approximately 1.8 × 107 L. monocytogenes cells well−1.

Assuming an exponential bacterial growth at a constant specific growth rate (μ) until the detection time, Td is related to the lag time of the culture (lag) by the following formula proposed by Baranyi and Pin (7):

|

(1) |

where Nd is the bacterial number at Td and N0 the number of cells initiating growth in the considered well.

Components of the variance of detection times.

In order to estimate the part of the variability of Td explained by the variability of lag, we tried to estimate the components of the variance of Td. From equation 1, we can write

|

(2) |

where  is the covariance term and ɛ is an error term corresponding to the reading inaccuracy of the Bioscreen C reader. The Bioscreen C reading inaccuracy was assumed negligible.

is the covariance term and ɛ is an error term corresponding to the reading inaccuracy of the Bioscreen C reader. The Bioscreen C reading inaccuracy was assumed negligible.

When the initial number of cell N0 is high, we can assume that lag and N0 are independent (6), and then the term of covariance is negligible as Nd, μ, and lag are independent. In this case, equation 2 can be written

|

(3) |

Moreover we have

|

(4) |

where K is a constant quantifying the “physiological state” of the initial population (42); and then we have

|

(5) |

From an experiment carried out with a high inoculum of cells in the exponential growth phase (3.3 × 104 cells well−1 instead of 0.42), we estimated from viable count and OD curves (3) a maximum specific growth rate, μ, of 0.90 h−1 and a lag time, lag, of 0.32 h. K was found to be equal to 0.29. As K is greatly smaller than 1,

|

(6) |

Equation 3 becomes

|

(7) |

The Taylor's series approximation allows us to write for two independent variables A and B

|

(8) |

Therefore we have for a high initial number of cells

|

(9) |

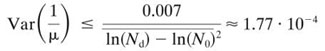

It was checked experimentally that Var(Td) = 0.007. Nd was found to correspond by viable count to a concentration of 1.77 × 107 CFU well−1. Yet, it was not possible to identify precisely which part of the observed Td is explained by the terms of equation 9. Indeed we had estimations of N0, Nd, and μ from viable counts but no sufficiently reliable information on their variance. Nevertheless, we were able to estimate the maximum possible value of Var and Var(ln(Nd)) from the experimental result. Var

and Var(ln(Nd)) from the experimental result. Var is maximum if Var(ln(Nd)) = Var(ln(N0)) = 0, so

is maximum if Var(ln(Nd)) = Var(ln(N0)) = 0, so

|

(10) |

and Var(ln(Nd)) is maximum when Var(ln(N0)) = Var = 0, so

= 0, so

|

(11) |

As the covariance term in equation 2 is negative, we have

|

(12) |

For experiments with single cells, N0 was assumed to follow a Poisson distribution with an average of 0.42 cells well−1. For the estimation of Var(ln(N0)),we used the positive values of the random samples generated by this distribution (10,000 iterations). It was found that Var(ln(N0)) ≈ 0.0934. Var(ln(Nd)) and Var were assumed to be independent of the inoculum's size and the initial physiological state. So, from the values previously obtained it was possible to estimate the minimum part of Var(Td) explained by Var(lag) for experiments with single cells.

were assumed to be independent of the inoculum's size and the initial physiological state. So, from the values previously obtained it was possible to estimate the minimum part of Var(Td) explained by Var(lag) for experiments with single cells.

With equation 12 and our results we have

|

(13) |

Standardization of the datasets.

As we aimed at characterizing the statistical distribution of Td values, the datasets of replicates needed to be cumulated and their standardization was necessary. The standardization was carried out in two steps in order to correct the sources of variability between experiments (VarBE). VarBE has two sources of variability: the variability between experiments due to the differences in the conditions of growth VarBE1 and the variability between experiments due to the reproducibility variability in the preparation of the stressed cells VarBE2. VarBE was estimated through the variance of means of Td in replicates.

Standardization to correct VarBE1.

For wells inoculated with stressed cells, the mean and the variance of Td values were very dependent on extreme values in a data set. So, the impact of growth conditions was corrected by using Td values of the wells inoculated with cells in the exponential growth phase, included in the same plate. It consisted of a transformation of the Td values by centering the mean of each data set for the cell in the exponential growth phase.

|

(14) |

where tij is the standardized value of Td,ij, the ith value of Td for the jth experiment; Tex, · j is the mean of Td values of the wells inoculated with cells in the exponential growth phase of the jth experiment; and Tex, · · is the mean of Tex, · j.

Standardization to correct VarBE2.

A second step was proposed for the standardization of Td values for wells inoculated with stressed cells. This step aimed at correcting the heterogeneity between experiments of the preparation of the stressed cells. This step was carried out by using the 5th percentile of the distribution of tij values. Indeed, the 5th percentile was preferred to the mean, which is too much dependent on extreme values, particularly when datasets are small.

|

(15) |

where t′ij is the standardized value of tij (equation 14), t5j is the 5th percentile of tij values of the jth experiment, and t5 · is the mean of t5j.

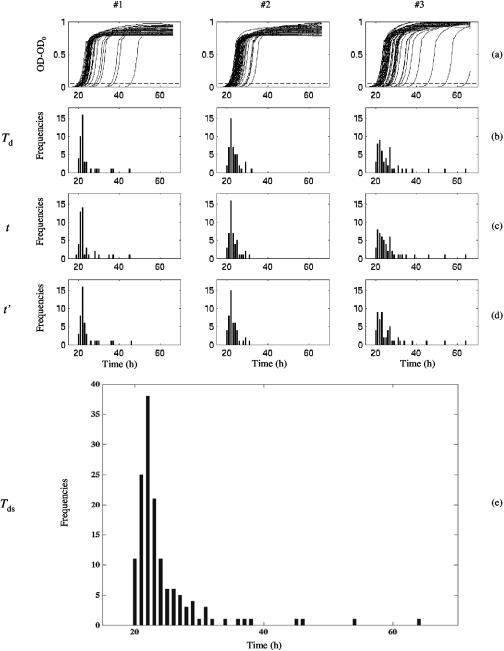

An example of the standardization process is shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Standardization steps of detection time values for the three datasets (#1, #2, and #3) of L. monocytogenes cells stressed by chlorine. (a) Optical density growth curves at 600 nm (OD-OD0) in TSBye at 30°C of the wells showing growth. Dashed line: limit of detection (OD0 + 0.05). (b) Histogram of observed detection times (Td) issued from OD growth curves. (c) Histogram of transformed detection times after the first step of standardization (t). (d) Histogram of transformed detection times after the second step of standardization (t′). (e) Histogram of the cumulated values of t′ of the three datasets (Tds).

Fitting data.

The standardized detection times (Tds), t for cells in the exponential growth phase and t′ for stressed cells, were fitted to various parametric distributions using Regress+ (version 2.5.1 by Michael P. McLaughlin; http://www.causaScientia.org/software/Regress_plus.html) or the nlinfit subroutine of MATLAB software (version 6.5.1; The Math Works Inc., Natick, MA). The cumulative distribution functions were issued from Regress+. The log-likelihood criterion was chosen to select the theoretical distribution functions fitting the best observed Tds distributions. Quantile-quantile plots were also edited to check visually the goodness of fit of Tds distributions.

RESULTS

Detection time distribution for L. monocytogenes cells in the exponential growth phase.

Taking into account the components of the variance of Td allowed us to say that only 11% of the observed variability is explained by the lag time variability (Table 1). An extreme value type I distribution (or extreme value distribution with an upper bound) was fitted to the 544 values of Tds obtained from 37 datasets (Fig. 2).

TABLE 1.

Means and variances of observed (Td) and standardized (Tds) detection times of single cells of L. monocytogenes in different physiological states

| Physiological state | No. of values |

Td

|

Tds

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (h) | Var(Td) (h2) | Mean (h) | Var(Tds) (h2) | Var(lag) (h2) | Var(lag)/Var(Tds) (%)a | ||

| Exponential growth phase | 544 | 18.41 | 0.385 | 18.50 | 0.208 | 0.023 | 11.1 |

| HCl | 92 | 20.43 | 1.219 | 20.45 | 1.211 | 1.026 | 84.7 |

| Cold | 109 | 21.16 | 12.385 | 21.13 | 12.412 | 12.227 | 98.5 |

| Lactic acid | 108 | 23.91 | 7.372 | 22.74 | 7.320 | 7.135 | 97.5 |

| Chlorine | 143 | 24.38 | 36.173 | 24.30 | 36.001 | 35.816 | 99.5 |

| NaOH | 137 | 25.50 | 13.244 | 25.52 | 13.110 | 12.925 | 98.6 |

| NaCl | 108 | 26.05 | 36.149 | 26.23 | 34.762 | 34.577 | 99.5 |

| Starvation | 84 | 26.37 | 28.083 | 26.84 | 27.112 | 26.927 | 99.3 |

| BAC | 170 | 30.06 | 75.805 | 30.51 | 73.916 | 73.731 | 99.7 |

| Heat | 89 | 33.59 | 39.132 | 34.48 | 38.103 | 37.918 | 99.5 |

Minimum percentage of the variance explained by individual lag time variability as Var(lag) ≥ Var(Td) − 0.185 h2.

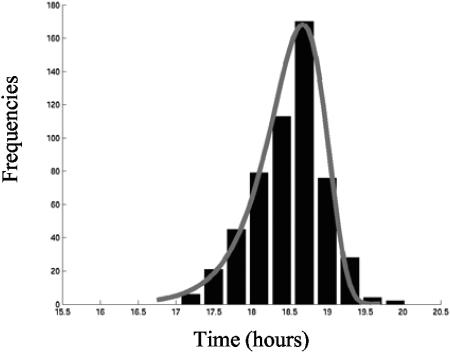

FIG. 2.

Observed and fitted density distributions of the standardized detection times Tds (in hours) of wells inoculated with L. monocytogenes cells in the exponential growth phase. Continuous curve: fitted extreme value type I distribution (cumulative density function and parameters in Table 2). Histogram: observed frequencies of Tds.

Influence of the stresses on detection time distributions.

Using the standardization method for Td values of stressed cells makes it possible to take into account the variance between experiments and to group datasets. Table 1 depicts the means and variances of Td before and after standardization. The results of the standardization support the conclusion that the observed variability was mainly explained by individual lag time variability. No effect of the physiological state of the cells was noticed on the growth rate. The distributions of detection times revealed the importance of the increase of lag time for stressed L. monocytogenes cells. By using the mean of Tds to compare the impacts of the nine stresses, the following classification was obtained (ascending impact): HCl, cold, lactic acid, chlorine, NaOH, NaCl, starvation, BAC, and heat. Undoubtedly BAC and heat stresses had the greatest impact on the lag time duration in our experimental conditions. The mean of Tds was multiplied by 1.65 for BAC stress and by 1.87 for heat stress in comparison with the mean of Tds values for cells in the exponential growth phase. On the other hand, acid and cold stresses didn't seem to have the same influence and the mean was multiplied by a factor of 1.1.

The distributions of detection times revealed the importance of the increase of cellular variability for stressed L. monocytogenes cells. Variance was also used to compare the impacts of the nine stresses applied. By using this parameter, the following classification was obtained (ascending impact): HCl, lactic acid, cold, NaOH, starvation, NaCl, chlorine, heat, and BAC. For example, the variance of Tds for L. monocytogenes cells in the exponential growth phase was multiplied by 355 compared to wells inoculated with BAC-stressed cells. The mineral acid stress, which had the smaller impact on the mean of detection times, generated a multiplication of the variance by 6.

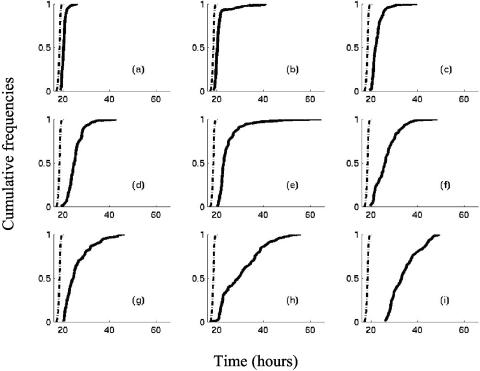

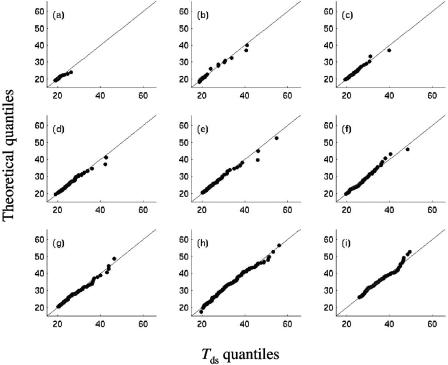

Figure 3 shows that the cumulative distribution of Tds values turns into heterogeneous shapes. Theoretical distributions have been fitted to Tds values. Six different theoretical distributions were found (Table 2) for the nine stresses. Figure 4 clearly reveals that they fit well the Tds distributions. Extreme value type II distribution was fitted for acids, alkali, and chlorine stresses, a gamma distribution for starvation stress, and a Weibull distribution for heat-stressed cells. For cold and BAC stresses, bimodal distributions were found to be suitable to fit Tds. There is no a priori reason to choose a bimodal distribution for cold-stressed L. monocytogenes cells, but the presence of a few (10%) cells with very long detection times (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4) suggests that a mixture of two distributions might be acceptable.

FIG. 3.

Observed cumulative distributions of the standardized detection times of L. monocytogenes in TSBye at 30°C. Dashed line: cumulative distribution of Tds (in hours) for wells inoculated with cells in the exponential growth phase. Continuous curves: cumulative distributions of observed Tds for wells inoculated with cells previously stressed by (a) HCl, (b) cold, (c) lactic acid, (d) NaOH, (e) chlorine, (f) starvation, (g) NaCl, (h) BAC, and (i) heat.

TABLE 2.

Theoretical distributions fitted to standardized detection time values of L. monocytogenesa

| Physiological state | Distribution | Cumulative density function | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exponential growth phase | Extreme value type I | 1 − exp(−exp((y − a)/b)) | a = 18.678 (18.674, 18.682) |

| b = 0.372 (0.367, 0.376) | |||

| HCl | Extreme value type II | exp(−((y − a)/b)−c) | a = 14.02 (−49.2, 17.80) |

| b = 5.95 (2.13, 60.70) | |||

| c = 8.74 (3.38, 100) | |||

| Cold | Mixture of normal and Laplace | p · Φ((y − a)/b) + (1 − p) · stdLaplaceCDF((y − c)/d) | a = 20.26 (20.11, 20.40) |

| b = 0.74 (0.64, 0.85) | |||

| c = 30.39 (26.06, 35.18) | |||

| d = 4.52 (1.69, 7.76) | |||

| p = 0.92 (0.87, 0.97) | |||

| Lactic acid | Extreme value type II | exp(−((y − a)/b)−c) | a = 15.13 (8.61, 18.30) |

| b = 6.42 (3.11, 13.10) | |||

| c = 4.80 (2.49, 9.71) | |||

| Chlorine | Extreme value type II | exp(−((y − a)/b)−c) | a = 18.02 (16.41, 19.06) |

| b = 3.80 (2.64, 5.59) | |||

| c = 2.15 (1.52, 3.10) | |||

| NaOH | Extreme value type II | exp(−((y − a)/b)−c) | a = −29.54 (−252.61, 106.88) |

| b = 53.47 (12.80, 276.65) | |||

| c = 21.03 (4.72, 100.00) | |||

| NaCl | Exponential | 1 − exp((a − y)/b) | a = 20.31 (20.31, 20.31) |

| b = 5.95 (4.87, 7.09) | |||

| Starvation | Gamma | Γ(c,(y − a)/b) | a = 19.49 (18.96, 19.66) |

| b = 3.98 (2.65, 5.60) | |||

| c = 1.93 (1.21, 3.33) | |||

| BAC | Mixture of 2 normal | p · Φ((y − a)/b) + (1 − p) · Φ((y − c)/d) | a = 21.89 (21.16, 22.15) |

| b = 0.78 (0.56, 1.04) | |||

| c = 33.99 (32.49, 35.60) | |||

| d = 7.75 (6.61, 8.78) | |||

| p = 0.29 (0.19, 0.39) | |||

| Heat | Weibull | 1 − exp(−((y − a)/b)a) | a = 25.86 (25.63, 25.91) |

| b = 9.45 (8.02, 10.03) | |||

| c = 1.41 (1.13, 1.76) |

For the cumulative density function, Φ(x) is the standard cumulative normal distribution, stdLaplaceCDF(z) is the standard cumulative Laplace distribution, and Φ(w,x) is the incomplete gamma function. For the parameters, the 95% confidence limits are in parentheses.

FIG. 4.

Quantile-quantile plots of the sample quantiles of the standardized detection times (Tds) versus theoretical quantiles from the fitted distributions for L. monocytogenes cells stressed by (a) HCl, (b) cold, (c) lactic acid, (d) NaOH, (e) chlorine, (f) starvation, (g) NaCl, (h) BAC, and (i) heat.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to compare the impacts of nine different stresses on the individual lag times of L. monocytogenes. A small number of previous studies have sought to examine this phenomenon of the historical impact of stress on individual lag times; furthermore, they have essentially concerned one stress (4, 33, 34). By using a similar physiological parameter, the loss of cultivability, for each stress, we succeeded in classifying the impacts of nine different stresses on the individual lag time distributions.

After observation of the sources of variability of detection times (Table 2), it can be advanced that the method of turbidity detection times produced by single cells is suitable to characterize lag time distributions of stressed cells. With a maximum of 35% of positive wells on the microplates, it can be asserted that the probability of having more than one cell in the wells did not have a deep impact on the distributions (Table 2). The observed variability cannot be explained by the presence of more than two cells in the same well. Indeed by choosing a maximum of 35% of positive wells, this results in an 80% probability of having a single cell. Other authors used an inoculation level resulting in a 70% probability of having a single cell, for Robinson et al. (27), and a 60% probability, for Métris et al. (23).

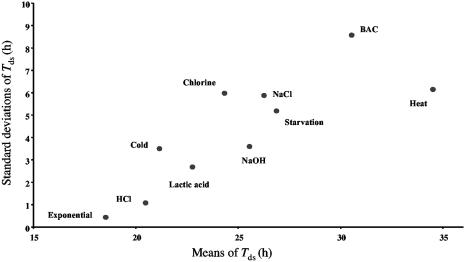

The presence of cells in the exponential growth phase on the same microplates with stressed cells allowed us to correct the variability between experiments due to the differences in the conditions of growth. For the same loss of cultivability on TSAye, the mean of Tds was multiplied by a factor between 1.1 and 1.87. Heat and BAC stresses induced the greatest increase of the mean of Tds (Fig. 5). After observation of the variances of Tds (Table 1), the nine stresses can be classified in four groups. The first includes HCl stress, which has the weakest impact on the total variance of Tds. The second group is composed of lactic acid, NaOH, and cold stresses; their variance of Tds is approximately 30 times more important than the variance of Tds for cells in the exponential growth phase. Starvation, NaCl, and chlorine stresses form the third group. The factor of multiplication of the variance of Tds for cells in the exponential growth phase is 140 for this group. The last group is composed of heat and BAC stresses. For this last group the variance of Tds is multiplied by 180 and 355, respectively, in comparison to the variance of Tds for cells in the exponential growth phase.

FIG. 5.

Standard deviations versus mean values of the standardized detection time (Tds) distributions of L. monocytogenes cells for all the studied stresses.

With about 100 standardized data issued from at least three replicates, we obtained suitable distributions. Regarding the variability of lag time presented here, it can be noticed that 100 values are often enough to precisely characterize a distribution, but when the variability becomes high, more than 100 values should be obtained. That was the case with BAC stress and its high variance of detection time values (Table 1).

With cells subjected to nine different stresses and cells in the exponential growth phase, we obtained seven different shapes of distribution of detection times. The distributions fitted were strongly adjusted to data (Fig. 4).

In our study, the distribution of detection times for inoculated single cells in the exponential growth phase is skewed on the left. That is not in agreement with the results of Wu et al. (40), who fitted a normal distribution to individual lag times of cells in the exponential growth phase. However, their 40 values are insufficient to properly characterize a distribution. Smelt et al. (33) also used cells in the exponential growth phase (Lactobacillus plantarum), and their detection time values followed, as our results, a left-skewed extreme value distribution. However, as we focused on the sources of variances of detection times for cells in the exponential growth phase (Table 1), it is obvious that the variance of individual lag times is not the main source of variability and their distribution cannot be reached.

The gamma distribution that we obtained (Table 2) for starved L. monocytogenes cells confirmed the findings of Métris et al. (23) who also fitted a gamma distribution to Listeria innocua cells issued from a stationary-phase culture. These cells can be considered as undergoing a starvation stress and thus it should be considered that individual lag times for starved cells of the main strains of Listeria may be gamma distributed.

For the three stresses involving a modification of pH (both acid and alkali stresses), the same distribution was fitted on the standardized detection times: the extreme value type II distribution. More generally, for the nine stresses presented in our communication, right-skewed distributions were obtained like Smelt et al. and Stephens et al. (33, 34) obtained with heat-injured Salmonella and L. plantarum.

Contrary to the findings of Métris et al. (23) who found a good linear correlation relationship (r2 = 0.94) between the means and the standard deviations of the detection time values by studying the effect of environmental growth conditions, the linear correlation between the means and the standard deviations was weak (r2 = 0.68) in our experiments (Fig. 5). The coefficient of variation of detection times for Métris et al. (23) rose from 5 to 10% as the growth conditions became less favorable. Treatments, which generated bacterial stress, appeared to have more influence on the variability of individual lag times than the growth conditions. Indeed, the coefficient of variation of detection times in our study was between 5 and 28% for stressed cells.

The variability of lag times presented in this study confirms the findings of other fields of microbiology. Indeed, marked heterogeneity occurs between individual cells within a clonal population. Such heterogeneity has already been revealed in almost any phenotype which is determinable at the single cell level, e.g., in the intracellular pH (13, 25, 31) or cell morphology (15, 16, 30, 36).

Because there are so many factors having an influence on the individual lag behavior (35), accurate physiological explanations of lag time heterogeneity are very difficult to obtain. An important general working hypothesis, formulated by Robinson et al. (26), states that lag is determined by two (hypothetical) quantities. The first quantity is the amount of work the cell has to perform to recover a physiological state that allows the cell to multiply. For example, Hornbaek et al. (19) observed a trimodal intracellular pH cell distribution for Bacillus licheniformis. The capacity to multiply being correlated to intracellular pH, they revealed that the subpopulation of cells exhibiting lower intracellular pH had significantly longer lag phases than populations of cells having higher intracellular pH. The second quantity is the rate at which the cell can perform that work. The rate may be identified in case of stress with metabolic processes of repair systems (21). These processes vary with the nature of the stress and involve the synthesis of ATP, RNA, and DNA (10). As these mechanisms of repair were present in low abundance, Booth (9) proposed that their concentration in the cells would follow stochastic processes leading to their Poissonian distribution. Such an imbalance in the cells could generate a different rate for cells having the same work to do to recover the capacity of growth.

This research sought to evaluate and classify the impacts of stresses on individual lag time distribution of L. monocytogenes. The results of this study give information on the consequences of food processing on L. monocytogenes lag time. As we have shown, lag time distribution is dependent on the stress undergone by the cell. It results in an increased variability of lag times and in their particular distribution. Increased understanding of the individual behaviors after stress and the factors that affect them will contribute to the development of improved predictive models. These results reinforce the need to move about a stochastic approach of bacterial growth, especially when predictive microbiology is used for assessing the exposure to microbiological hazards (8). In the future we will focus on the study of the individual lag time variability by applying successive stresses corresponding to food processing events in order to optimize the evaluation of processing methods with respect to bacteriological safety and the quality of the food.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Ministères de la Recherche et de l'Agriculture (convention R02/04 programme Aliment-Qualité-Sécurité) and belongs to the French national program for predictive microbiology Sym'Previus.

L. Guillier is a recipient of a doctoral fellowship from Arilait-Recherches and the Association Nationale de la Recherche Technique.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anonymous. 2003. Quantitative assessment of relative risk to public health from foodborne Listeria monocytogenes among selected categories of ready-to-eat foods. [Online.] http://www.foodsafety.gov/∼dms/lmr2-toc.html.

- 2.Anonymous. 2004. Risk assessment of Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods, MRA series 4 & 5. [Online.] http://www.who.int/foodsafety/publications/micro/mra_listeria/en/.

- 3.Augustin, J. C., L. Rosso, and V. Carlier. 1999. Estimation of temperature dependent growth rate and lag time of Listeria monocytogenes by optical density measurements. J. Microbiol. Methods 38:137-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Augustin, J. C., A. B. Delattre, L. Rosso, and V. Carlier. 2000. Significance of inoculum size in the lag time of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1706-1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Augustin, J. C., and V. Carlier. 2000. Mathematical modelling of the growth rate and lag time for Listeria monocytogenes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 56:29-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baranyi, J. 1998. Comparison of stochastic and deterministic concepts of bacterial lag. J. Theor. Biol. 192:403-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baranyi, J., and C. Pin. 1999. Estimating growth parameters by means of detection times. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:732-736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baranyi, J., and C. Pin. 2004. Modeling the history effect on microbial growth and survival: deterministic and stochastic approaches, p. 285-302. .In R. C. McKellar and X. Lu (ed.), Modeling microbial responses in food. CRC series in contemporary food science. CRC, Washington, D.C.

- 9.Booth, I. R. 2002. Stress and the single cell: intrapopulation diversity is a mechanism to ensure survival upon exposure to stress. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 78:19-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bozoglu, F., H. Alpas, and G. Kaletunç. 2004. Injury recovery of foodborne pathogens in high hydrostatic pressure treated milk during storage. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 40:243-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bréand, S., G. Fardel, J. P. Flandrois, L. Rosso, and R. Tomassone. 1997. A model describing the relationship between lag time and mild temperature increase duration. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 38:157-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bréand, S., G. Fardel, J. P. Flandrois, L. Rosso, and R. Tomassone. 1999. A model describing the relationship between lag time and mild temperature increase duration for Listeria monocytogenes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 46:251-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Budde, B. B., and M. Jakobsen. 2000. Real-time measurements of the interaction between single cells of Listeria monocytogenes and nisin on a solid surface. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3586-3591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davey, K. R. 1991. Applicability of the Davey (linear Arrhenius) predictive model to the lag phase of microbial growth. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 70:253-257. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dykes, G. A. 1999. Physical and metabolic causes of sub-lethal damage in Listeria monocytogenes after long-term chilled storage at 4 degrees C. J. Appl. Microbiol. 87:915-922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Kest, S. E., and E. H. Marth. 1992. Transmission electron microscopy of unfrozen and frozen/thawed cell of Listeria monocytogenes treated with lipase and lysozyme. J. Food Prot. 55:687-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farber, J. M., and P. I. Pertenkins. 1991. Listeria monocytogenes, a foodborne pathogen. Microbiol. Rev. 55:476-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Francois, K., F. Devlieghere, A. R. Standaert, A. H. Geeraerd, J. F. Van Impe, and J. Debevere. 2003. Modelling the individual lag phase. Isolating single cells: protocol development. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 37:26-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hornbaek, T., J. Dynesen, and M. Jakobsen. 2002. Use of fluorescence ratio imaging microscopy and flow cytometry for estimation of cell vitality for Bacillus licheniformis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 215:261-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKellar, R. C. 1997. A heterogenous population model for the analysis of bacterial growth kinetics. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 36:179-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKellar, R. C., and X. Lu. 2004. Primary models, p. 21-62. .In R. C. McKellar and X. Lu (ed.), Modeling microbial responses in food. CRC series in contemporary food science. CRC, Washington, D.C.

- 22.McMeekin, T. 2004. An essay on the unrealized potential of predictive microbiology, p. 321-336. .In R. C. McKellar and X. Lu (ed.), Modeling microbial responses in food. CRC series in contemporary food science. CRC, Washington, D.C.

- 23.Métris, A., S. M. George, M. W. Peck, and J. Baranyi. 2003. Distribution of turbidity detection times generated by single cell-generated bacterial populations. J. Microbiol. Methods 55:821-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pascual, C., T. P. Robinson, M. J. Ocio, O. O. Aboaba, and B. M. Mckey. 2001. The effect of inoculum size and sublethal injury on the ability of Listeria monocytogenes to initiate growth under suboptimal conditions. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 33:357-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rechinger, K. B., and H. Siegumfeldt. 2002. Rapid assessment of cell viability of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus by measurement of intracellular pH in individual cells using fluorescence ratio imaging microscopy. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 75:53-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson, T. P., M. J. Ocio, A. Kaloti, and B. M. Mckey. 1998. The effect of growth environment on the lag phase of Listeria monocytogenes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 44:83-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson, T. P., M. J. Ocio, A. Kaloti, and B. M. Mckey. 2001. The effect of inoculum size on the lag phase of Listeria monocytogenes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 70:163-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ross, T., and T. A. McMeekin. 1994. Predictive microbiology: review paper. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 23:241-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross, T., and P. Dalgaard. 2004. Secondary models, p. 63-150. .In R. C. McKellar and X. Lu (ed.), Modeling microbial responses in food. CRC series in contemporary food science. CRC, Washington, D.C.

- 30.Rowan, N. J., and J. G. Anderson. 1998. Effects of above-optimum growth temperature and cell morphology on thermotolerance of Listeria monocytogenes cells suspended in bovine milk. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2065-2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siegumfeldt, H., K. B. Rechinger, and M. Jakobsen. 1999. Use of fluorescence ratio imaging for intracellular pH determination of individual bacterial cells in mixed cultures. Microbiology 145:1703-1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skinner, G. E., J. W. Larkin, and E. J. Rhodehamel. 1994. Mathematical modelling of microbial growth: a review. J. Food Safety 14:175-217. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smelt, J. P. P. M., G. D. Otten, and A. P. Bos. 2002. Modelling the effect of sublethal injury on the distribution of the lag times of individual cells of Lactobacillus plantarum. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 73:207-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stephens, P. J., J. A. Joynson, K. W. Davies, R. Holbrook, H. M. Lappin-Scott, and T. J. Humphrey. 1997. The use of an automated growth analyser to measure recovery times of single heat-injured Salmonella cells. J. Appl. Microbiol. 83:445-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swinnen, I. A. M., K. Bernaerts, E. J. J. Dens, A. H. Geeraerd, and J. F. Van Impe. 2004. Predictive modelling of the microbial lag phase: a review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 96:137-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tholozan, J. L., J. M. Cappelier, J. P. Tissier, G. Delattre, and M. Federighi. 1999. Physiological characterization of viable-but-nonculturable Campylobacter jejuni cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1110-1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walls, I., and V. N. Scott. 1997. Validation of predictive mathematical models describing the growth of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Food Prot. 60:1142-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whiting, R. C. 1995. Microbial modelling in foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 35:467-494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whiting, R. C., and L. K. Bagi. 2002. Modelling the lag phase of Listeria monocytogenes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 73:291-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu, Y., M. W. Griffith, and R. C. McKellar. 2000. A comparison of the Bioscreen method and microscopy for the determination of lag times of individual cells of Listeria monocytogenes. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 30:468-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zwietering, M. H., J. T. De Koos, B. E. Hasenack, J. C. de Wit, and K. van't Riet. 1991. Modeling bacterial growth as a function of temperature. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:1094-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zwietering, M. H., H. G. A. M. Cuppers, J. C. de Wit, and K. van't Riet. 1994. Evaluation of data transformations and validation of a model for the effect of temperature on bacterial growth. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:195-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]