Abstract

Background and study aims Topical hemostatic agents emerged as a new treatment modality for gastrointestinal bleeding. The aim of this study was to assess the safety and efficacy of PuraStat for control of active bleeding and for prevention of bleeding after different operative endoscopy procedures.

Patients and methods A national, multicenter, observational registry was established to collect data from ten Italian centers from June 2021 to February 2023. Demographics, type of application (active gastrointestinal bleeding or prevention after endoscopic procedures, site, amount of gel used, completeness of coverage of the treated area), outcomes (rates of intraprocedural hemostasis and bleeding events during 30-day follow-up), and adverse events (AEs) were prospectively analyzed.

Results Four hundred and one patients were treated for active gastrointestinal bleeding or as a preventive measure after different types of operative endoscopy procedures. Ninety-one treatments for active bleeding and 310 preventive applications were included. In 174 of 401 cases (43.4%), PuraStat was the primary treatment modality. Complete coverage was possible in 330 of 401 (82.3%) with difficulty in application in seven of 401 cases (1.7%). Hemostasis of active bleedings was achieved in 90 of 91 patients (98.9%). In 30-day follow-up 3.9% patients in whom PuraStat was used for prophylaxis had a bleeding event compared with 7.7% after hemostasis. No AEs related to the use of PuraStat were reported.

Conclusions PuraStat is a safe and effective hemostat both for bleeding control and for bleeding prevention after different operative endoscopy procedures. Our results suggest that the possible applications for the use of PuraStat may be wider compared with current indications.

Keywords: Endoscopy Upper GI Tract; Non-variceal bleeding; Endoscopy Lower GI Tract; Lower GI bleeding; Quality and logistical aspects; Performance and complications; Endoscopic resection (ESD, EMRc, ...); Endoscopic resection (polypectomy, ESD, EMRc, ...)

Introduction

Acute gastrointestinal bleeding, from either an upper or lower source, is a common clinical entity that often requires hospitalization and is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. Although risk assessment protocols and treatment algorithms have been implemented, gastrointestinal bleeding still represents a relevant economic burden for healthcare systems 1 .

Endoscopy is a cornerstone of management of gastrointestinal bleeding, for both assessment and treatment. The endoscopic armamentarium for hemostasis is wide, but it can be broadly categorized into injection, mechanical, and thermal methods 2 3 .

In recent years, topical hemostatic agents have emerged as a new treatment modality that may have a role in challenging situations, such as management of diffuse bleeding or hemostasis of lesions located in regions difficult to reach endoscopically 4 . These agents (ie. Hemospray, EndoClot) are provided as powder, which is propelled endoscopically via a compressed gas onto the bleeding site. On contact with bodily fluid, the powder turns into a gel and promotes hemostasis by sealing the bleeding site and enhancing clot formation 5 .

Use of hemostatic powders, however, is hampered by two main limitations: risk of clogging of the delivery catheter and limited visibility after application, due to the opaque nature of the hemostatic agent.

A novel type of topical hemostatic agent recently has been developed for treatment of oozing bleeding. PuraStat (3D-Matrix Europe SAS, France) is a viscous and transparent biocompatible synthetic peptide solution. On exposure to blood and because of a change in pH and ion concentration, it undergoes self-assembly into fibers and forms a hydrogel barrier that has a hemostatic effect and works as an extracellular matrix scaffold for subsequent healing 6 7 .

The first clinical applications of PuraStat were described in various fields, including cardiac surgery 8 9 , vascular 10 , ear, nose and throat 11 12 13 , and general surgery 14 15 .

With regard to gastrointestinal endoscopy, PuraStat has proved effective and its use was approved for postprocedural oozing and bleeding from small blood vessels in the gastrointestinal tract as an adjunct hemostatic modality and for reduction of delayed bleeding after colonic endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) 16 17 18 .

Further studies investigated the potential role of PuraStat in other indications, such as spontaneous acute gastrointestinal bleeding 19 20 21 , post-sphincterotomy bleeding 22 23 24 25 26 , post-papillectomy bleeding 27 28 , gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) 29 , hemorrhagic radiation proctopathy 30 , walled-off pancreatic necrosis 31 , solitary rectal ulcer syndrome 32 , acute intrahepatic biliary duct bleeding 33 , bleeding after endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy 34 , and delayed percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) bleeding 35 , with very limited data but initial results seemed promising.

To further investigate the role of PuraStat for various applications, we established a national, multicenter, observational registry with the aim of collecting data about feasibility, effectiveness, and safety and identifying any possible additional field of use other than the current indications.

Patients and methods

Patients

All patients that underwent endoscopy and for whom PuraStat was used were eligible for recruitment in the registry. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Research at Humanitas Research and Clinical Center as coordinating center. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before they underwent the endoscopic procedure at the respective institutions.

Inclusion criteria were age > 18 years and patient consent to be included in the study. The exclusion criterion was presence of a known coagulopathy likely to affect risk of bleeding.

Data were collected bout patient demographics, comorbidities (i.e. cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, liver disease, renal disease), antithrombotic treatment (antiplatelets, anticoagulants), blood tests (complete blood count and coagulation parameters), and need for blood product transfusion.

PuraStat use was possible in the setting of both active gastrointestinal bleeding (spontaneous or related to endoscopic procedure) and bleeding prevention after endoscopic procedures.

In case of active bleeding, data were collected regarding bleeding severity (mild: ooze from mucosa or resection base; moderate: bleeding visible vessel or clot; severe: arterial spurt), cause and location, whether hemostasis was possible, if PuraStat was the primary or secondary hemostatic treatment, and what other type of hemostatic therapy was used (i.e. injection, thermal, mechanical).

In case of use of PuraStat for prevention after endoscopic procedures, data were collected regarding the type of procedure (i.e. endoscopic mucosal resection [EMR], knife assisted resection [KAR], ESD, sphincterotomy, endoscopic papillectomy, treatment of radiation proctopathy), lesion size and extension (where applicable), length of procedure, if PuraStat was the primary or secondary hemostatic treatment, and if any other hemostatic method was used.

The patient then entered a follow-up period of 30 days in order to collect data about rebleeding after previous hemostasis with PuraStat or post-procedural bleeding after prophylactic application of PuraStat, and how the bleeding event was managed.

The primary endpoints of the studies were the rate of successful hemostasis with PuraStat in case of active bleeding and the rate of post-procedural bleeding after prophylactic PuraStat application. Secondary endpoints were represented by the rebleeding rate after hemostasis with PuraStat in case of active bleeding and completeness of coverage of the area treated with PuraStat for either hemostasis or postprocedural bleeding prevention. Furthermore, data about difficulty of PuraStat application were analyzed.

Finally, data were collected about safety and adverse events (AEs) related to PuraStat.

PuraStat application

Before the start of the study, training sessions about application of PuraStat were provided to investigators involved in the recruiting centers. The investigators from each center were endoscopists with significant experience in therapeutic endoscopic procedures.

The decision about whether employ PuraStat was left to operator discretion, based on the clinical scenario.

Use of PuraStat could be either as the primary and sole hemostatic treatment or as a secondary additional modality after other treatment options (i.e. mechanical, injection, thermal). In consideration of the effectiveness of PuraStat being proven in previous studies, especially for oozing and nonspurting bleeding, in the event of arterial spurting, application of PuraStat was allowed solely as a secondary therapy after a different primary hemostatic modality.

PuraStat was supplied in prefilled syringes available in different volumes (1 mL, 3 mL and 5 mL), according to the extent of the surface that needed to be covered. Delivery of PuraStat was carried out with a dedicated 220-cm endoscopic catheter (Nozzle System Type E) compatible with a 2.8-mm endoscopic working channel.

Data were collected about the total amount of PuraStat applied and percentage of coverage of the treated area, as well as difficulty of application and the reason for it (i.e. position of the endoscope, blockage or kinking of the catheter).

Statistical analysis

Patient data were collected in a dedicated electronic case report form (eCRF).

Descriptive statistics were calculated: mean value with standard deviation and median value with range were determined for continuous variables; percentages and proportions were determined for categorical variables.

Statistical analysis was performed using chi-squared, Fisher’s exact test, and Student’s t test, when appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Potential factors influencing the rebleeding rate after previous hemostasis with PuraStat and the delayed bleeding rate after prophylactic application of PuraStat were tested in a univariate logistic regression model and results were expressed in terms of odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

The inferential analysis for time to event data, namely the factors influencing time to rebleeding, was conducted using the Cox univariate regression model to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs.

Statistical analyses were performed with the R Statistical Software 3.0.2, Survival package (Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

A total of 403 patients were recruited in 10 Italian centers from June 2021 to February 2023. Two patients were subsequently excluded for missing essential data.

Ninety-one patients with active gastrointestinal bleeding and 310 patients undergoing postprocedural bleeding prevention were included. Baseline patient characteristics, sorted by indication, are shown in Table 1 and Table 2 .

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of patients treated for active bleeding.

| EFTR, endoscopic full-thickness resection; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; SD, standard deviation; WOPN, wall-off pancreatic necrosis. | |

| Number of patients | 91 |

| Sex (n,%) | Male 62 (68.1) Female 29 (31.9) |

| Age (mean, SD) | 68.7 ± 14 |

| Comorbidities (n,%) | None 18 (19.8) Cardiovascular 55 (60.4) Diabetes 21 (23.1) Renal disease 12 (13.2) Liver disease 6 (6.6) |

| Antithrombotic therapy (n,%) | Antiplatelet 18 (19.8) Anticoagulant 18 (19.8) Both 3 (3.3) |

| Bleeding location (n,%) | Upper location 62 (68.2)

|

Lower location 26 (28.6)

Ileum 1 (1.1) |

|

| Cause of bleeding (n,%) | Iatrogenic 45 (49.5)

|

Ulcer 28 (30.8)

|

|

| Angiodysplasia 11 (12.1) Mass lesion 3 (3.3) Mallory-Weiss tear 1 (1.1) Radiation proctopathy 1 (1.1) Diverticular bleeding 1 (1.1) Duodenal necrosis 1 (1.1) |

|

| Bleeding severity (n,%) | Mild 34 (37.4) Moderate 52 (57.1) Severe 5 (5.5) |

Table 2 Baseline characteristics of patients undergoing postprocedural bleeding prevention.

| EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; GAVE, gastric antral vascular ectasia; KAR, knife assisted resection; SD, standard deviation; WOPN, walled-off pancreatic necrosis. | |

| Number of patients | 310 |

| Sex (n;%) | Male 165 (53.2) Female 145 (46.8) |

| Age (mean, SD) | 69 ± 12.2 |

| Comorbidities (n,%) | None 107 (34.5) Cardiovascular 178 (57.4) Diabetes 40 (12.9) Renal disease 13 (4.2) Liver disease 7 (2.3) |

| Antithrombotic therapy (n,%) | Antiplatelet 57 (18.4) Anticoagulant 32 (10.3) Both 4 (1.3) |

| Bleeding location (n,%) | Upper location 103 (33.2)

|

Lower location 200 (64.5)

|

|

| Biliopancreatic 7 (2.3) | |

| Endoscopic procedure (n,%) | ESD 172 (55.5)

|

EMR 94 (30.3)

|

|

| ERCP 8 (2.6) Papillectomy 8 (2.6) |

|

KAR 8 (2.6)

|

|

| WOPN drainage 7 (2.3) Treatment of GAVE 4 (1.3) |

|

Polypectomy 3 (1)

|

|

| Treatment of gastric mass lesion 3 (1) Treatment of radiation proctopathy 2 (0.6) Pneumatic anastomotic dilation 1 (0.3) |

|

No AEs or complications related to PuraStat use were reported.

Acute active bleeding

The most relevant cause of acute gastrointestinal bleeding was iatrogenic in 45 cases, 39 of which occurred during an endoscopic intervention. The remaining cases were spontaneous bleeds, such as ulcer bleeding (28), and angiodysplasia (11), followed by other less common etiologies (further details are provided in Table 1 and Table 3 ).

Table 3 Details about treatments for active bleeding.

| EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; WOPN, walled-off pancreatic necrosis. | |

| Number of patients | 91 |

| PuraStat as primary modality | 30 (33) |

| Other primary treatment modality + PuraStat as secondary modality | 61 (67) |

|

|

| Cause of bleeding treated with PuraStat alone | Endoscopic intraprocedural 16

|

Ulcer 7

|

|

Angiodysplasia 2

|

|

| Mallory-Weiss tear 1 Anastomotic bleeding 1 Duodenal mass lesion 1 Duodenal necrosis 1 Post PEG placement 1 |

|

| Cause of bleeding treated with injection of a hemostatic agent + PuraStat | Endoscopic intraprocedural 7

|

Ulcer 8

|

|

| Duodenal angiodysplasia 1 Radiation proctopathy 1 |

|

| Cause of bleeding treated with thermal hemostasis + PuraStat | Endoscopic intraprocedural 2

|

Angiodysplasia 3

|

|

| Duodenal mass lesion 1 | |

| Cause of bleeding treated with mechanical hemostasis + PuraStat | Endoscopic intraprocedural 5

|

Ulcer 4

|

|

Angiodysplasia 3

|

|

| Anastomotic bleeding 3 Diverticular bleeding 1 |

|

| Cause of bleeding treated with combination modality + PuraStat | Endoscopic intraprocedural 9

|

Ulcer 9

|

|

Angiodysplasia 2

|

|

| Gastric mass lesion 1 Anastomotic bleeding 1 |

|

| Cases of rebleeding within 30 days | After PuraStat as primary treatment 3

|

After mechanical hemostasis + PuraStat 1

|

|

After injective hemostasis + PuraStat 1

|

|

After combination modality + PuraStat 2

|

|

For active bleeding, PuraStat was used as primary treatment modality in 30 patients (33%) and as secondary treatment modality in 61 patients (67%). Hemostasis was achieved in 90 cases (98.9%), with a single case (1.1%) of ineffective hemostasis due to diverticular bleeding that required subsequent radiological embolization.

In the setting of active bleeding, mean and median volumes of PuraStat used were 3.37 mL (± 1.51 mL) and 3 mL (range: 1–10 mL) respectively, with complete coverage of the treated area being possible in 76 patients (83.5%) and a mean percentage of coverage of 95% (± 12.4%).

Difficulty in application was reported in three cases (3.3%), all due to endoscope position.

During the follow-up period, seven cases (7.7%) of rebleeding were reported, five of which required endoscopic reintervention and one of which required treatment with interventional radiology.

Details about the outcomes after hemostasis with PuraStat are provided in Table 3 and Table 4 .

Table 4 Outcomes after hemostasis (active bleeding) with PuraStat.

| ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection. | |

| Effectiveness of hemostasis (n,%) | Effective 90 (98.9) Not effective 1 (1.1) |

| Rebleeding within 30 days (n,%) | 7 (7.7) |

|

Duodenal ulcer 2 Gastric ESD 1 Gastric ulcer 1 Duodenal angiodysplasia 1 Rectal ESD 1 Colorectal anastomosis bleeding 1 |

|

Mild 2 Moderate 5 Severe 0 |

|

None 3 On therapy (discontinued) 4 |

|

Complete 6 Incomplete (50%) 1 |

Logistic regression analysis was performed for rebleeding events after previous use of PuraStat for hemostasis of active bleeding. The threshold for significance, however, was reached for none of the variables taken into account (details are provided in Table 5 ).

Table 5 Logistic regression analysis for rebleeding within 30 days after hemostasis.

| Variable | Odds ratio and P value |

| OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. | |

| Sex | OR 1.45 (95% CI 0.78–3.11), P = 0.51 |

| Age | OR 0.78 (95% CI 0.56–2.16), P = 0.67 |

| Antiplatelet drug use | OR 1.43 (95% CI 0.91–2.32), P = 0.21 |

| Anticoagulant drug use | OR 1.35 (95% CI 0.71–2.30), P = 0.77 |

| Upper gastrointestinal tract origin of bleeding | OR 1.13 (95% CI 0.76–1.87), P = 0.94 |

| Bleeding related to endoscopic procedure | OR 1.78 (95% CI 0.93–2.87), P = 0.12 |

| PuraStat as primary treatment modality | OR 1.34 (95% CI 0.77–1.87), P = 0.56 |

| Complete coverage | OR 1.34 (95% CI 0.79–2.13), P = 0.87 |

| Difficult application | OR 1.11 (95% CI 0.89–2.33), P = 0.33 |

Bleeding prophylaxis

Prophylactic application of PuraStat was performed after the following endoscopic procedures: ESD (172), EMR (94), ERCP (8), endoscopic papillectomy (8), KAR (8), WOPN drainage (7), treatment of GAVE (4), polypectomy (3), treatment of gastric mass lesion (3), treatment of radiation proctopathy (2), and pneumatic colorectal anastomosis dilation (1). Further details are provided in Table 2 and Table 6 .

Table 6 Details about treatments for bleeding prevention.

| Treatments for bleeding prevention | |

| EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; GAVE, gastric antral vascular ectasia; KAR, knife assisted resection; SD, standard deviation; WOPN, walled-off pancreatic necrosis. | |

| Number of patients | 310 |

| PuraStat as primary modality | 144 (46.5) |

| Other primary treatment modality + PuraStat as secondary modality | 166 (53.5) |

|

1 (0.3) 92 (29.7) 31 (10) 42 (13.5) |

| Endoscopic procedure followed by bleeding prevention with PuraStat alone | EMR 53

|

ESD 56

|

|

KAR 6

|

|

Polypectomy 2

|

|

| Papillectomy 8 ERCP 7 WOPN drainage 7 Treatment of gastric mass lesion 2 Treatment of GAVE 1 Treatment of radiation proctopathy 1 Pneumatic anastomotic dilation 1 |

|

| Endoscopic procedure followed by bleeding prevention with injection modality + PuraStat | ERCP 1 |

| Endoscopic procedure followed by bleeding prevention with thermal modality + PuraStat | EMR 20

|

ESD 65

|

|

KAR 2

|

|

| Treatment of GAVE 3 Treatment of gastric mass lesion 1 Treatment of radiation proctopathy 1 |

|

| Endoscopic procedure followed by bleeding prevention with mechanical modality + PuraStat | EMR 17

|

ESD 14

|

|

| Endoscopic procedure followed by bleeding prevention with combination modality + PuraStat | EMR 4

|

ESD 37

|

|

| Duodenal polypectomy 1 | |

| Cases of bleeding within 30 days | After PuraStat as primary modality 5

|

After mechanical modality + PuraStat 3

|

|

After thermal modality + PuraStat 3

|

|

After combination modality + PuraStat 1

|

|

For bleeding prevention, PuraStat was used as the primary treatment modality in 144 patients (46.5%) and as secondary treatment modality in 166 patients (53.5%).

In the setting of bleeding prevention, mean and median volumes of PuraStat used were 3.32 mL (± 1.23 mL) and 3 mL (range: 1–6 mL), respectively, with complete coverage of the treated area being possible in 254 patients (81.9%) and a mean percentage of coverage of 98.8% (± 5.2%).

Difficulty in application was reported in four cases (1.3%), all due to endoscope position.

During the follow-up period, 12 cases (3.9%) of delayed bleeding were reported, seven of which required endoscopic reintervention and one of which required treatment with interventional radiology.

Details about the outcomes after prophylaxis with PuraStat are provided in Table 6 and Table 7 .

Table 7 Outcomes after bleeding prevention with PuraStat.

| EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection. | |

| Delayed bleeding (n,%) | 12 (3.9) |

|

ESD 6

|

|

None 7 On therapy (discontinued) 5 |

|

Complete 12 Incomplete 0 |

Predictive factors for postprocedural delayed bleeding

Logistic regression analysis was performed for delayed bleeding events after previous use of PuraStat for postprocedural bleeding prevention.

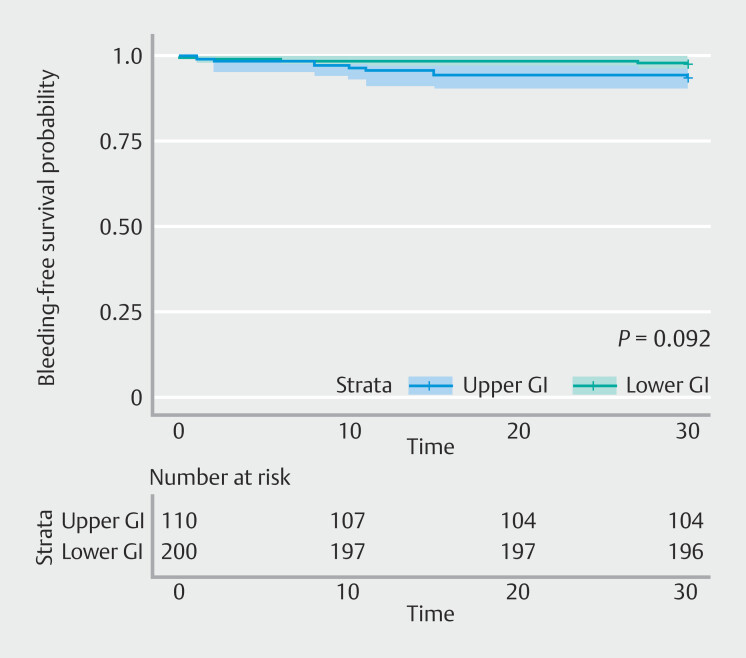

In particular, upper gastrointestinal bleeding had an OR of 1.49 (0.91–1.88; P = 0.09), although it was not statistically significant. The threshold for significance was not reached for any of the variables considered ( Table 8 ). Time-to-event analysis confirmed this trend (HR 0.38, 95% CI 0.12–1.21; P = 0.09) ( Fig. 1 ).

Table 8 Logistic regression analysis for delayed bleeding within 30 days after bleeding prevention.

| Variable | Odds ratio and P value |

| CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio. | |

| Sex | OR 1.64 (95% CI 0.71–3.23), P = 0.81 |

| Age | OR 1.98 (95% CI 0.88–3.07), P = 0.17 |

| Antiplatelet drug use | OR 1.41 (95% CI 0.76–2.51), P = 0.78 |

| Anticoagulant drug use | OR 2.64 (95% CI 0.88–3.67), P = 0.18 |

| Upper gastrointestinal tract origin of bleeding | OR 1.49 (95% CI 0.91–1.88), P = 0.09 |

| PuraStat as primary treatment modality | OR 1.45 (95% CI 0.71–2.03), P = 0.73 |

| ComPlete coverage | OR 1.38 (95% CI 0.75–1.88), P = 0.79 |

| Difficult application | OR 1.18 (95% CI 0.73–2.97), P = 0.87 |

Fig. 1.

Bleeding-free survival probability.

Logistic regression analysis was performed for delayed bleeding events in patients receiving antithrombotic and antiplatelet therapy. Even in these cases, the threshold for significance was not reached for any of the variables taken into account ( Table 8 ). In the case of rebleeding within 30 days after hemostasis with PuraStat, antiplatelet drug had an OR of 1.43 (95% CI 0.91–2.32; P = 0.21) and anticoagulant use had an OR of 1.35 (95% CI 0.71–2.30; P = 0.77). In the case of delayed bleeding within 30 days after bleeding prevention with PuraStat, antiplatelet and anticoagulant use had ORs of 1.41 (95% CI 0.76–2.51; P = 0.78) and 2.64 (95% CI 0.88–3.67; P = 0.18), respectively.

Discussion

Gastrointestinal bleeding is a condition often encountered in clinical practice, which is associated with high morbidity and mortality. Furthermore, with operative endoscopy procedures becoming more advanced and complex, bleeding is a well-known and common AE that may present either during the procedure or up to several days after it and which may be the cause of a longer hospital stay.

In recent years and since its introduction, PuraStat has emerged as an effective and safe hemostatic agent that may be helpful for both providing hemostasis for acute bleeding and preventing rebleeding or delayed bleeding events after various operative endoscopy procedures.

To the best of our knowledge, this registry collects data about the largest study population in which PuraStat has been used, for either hemostasis of acute gastrointestinal bleeding or prophylaxis of delayed bleeding following an endoscopic procedure.

PuraStat proved to be an excellent hemostatic agent for acute gastrointestinal bleeding as a primary or secondary modality, with an overall rate of successful hemostasis of 98.9%. Its effectiveness was shown in different bleeding settings: upper gastrointestinal, lower gastrointestinal and biliopancreatic, spontaneous, or related to different kinds of operative endoscopy procedures.

With regard to previous hemostasis with PuraStat, the rebleeding rate was low (7.7%) and in the majority of patients (85.7%), it was self-limiting or it could be managed with endoscopic reintervention.

In the context of postprocedural bleeding prevention, the data appeared promising as well, with delayed bleeding occurring in only 3.9% of patients, typically following endoscopic resection (ER) procedures (i.e. EMR, ESD, endoscopic papillectomy), and once again, it was self-limiting in nature or manageable with an endoscopic reintervention in the vast majority of patients (91.7%). The effectiveness of PuraStat application for bleeding prevention was studied in a wide array of endoscopic procedures involving the upper, lower, and biliopancreatic tract.

Of note, in the setting of prevention of post-procedural bleeding, PuraStat showed a higher magnitude of effect in the lower gastrointestinal tract (OR 1.49, 95% CI 0.91–1.88). Its use led to a 49% decrease in post-procedural bleeding in lower gastrointestinal as compared with the upper gastrointestinal, although the significance threshold was not reached ( P = 0.09), probably because the study was underpowered to detect this difference. Larger cohorts are needed to assess this important clinical issue. However, given the low event rate and the specific subsets of patients (prevention of postprocedural bleeding), a sample size of more than 1000 patients would be required to register a significant difference; unfortunately, such a huge sample size is very difficult to collect.

Regarding technical aspects, PuraStat delivery proved simple, with only a few cases of difficult application due to complex endoscope position. Nonetheless, near-complete coverage of the treated lesion was possible in almost all patients. Moreover, the safety profile of PuraStat proved excellent, with no reported AEs related to its application.

This noncomparative study is inevitably limited by the nature of its own design, which did not include a control group or random treatment assignment. Treatment was solely at the discretion of the operator, both for acute bleeding hemostasis and for bleeding prophylaxis, which therefore implies a potential risk of selection bias. In this regard, this study, therefore, can only provide real-world data.

In addition, due to the very low rates of both rebleeding after previous hemostasis and delayed bleeding after operative endoscopy procedures, it is not possible to draw any specific conclusions regarding any potential risk factor for PuraStat inefficacy. However, albeit not reaching the threshold for statistical significance, we can surmise two potential trends. One favors use of PuraStat for hemostasis of intraprocedural bleeding rather than its use for bleeding not related to endoscopic procedures and the other supports the use of PuraStat for bleeding prevention after endoscopic procedures on the lower gastrointestinal tract, rather than the upper gastrointestinal tract.

Nonetheless, we suggest that comparative studies may be necessary to mitigate the impact of confounding variables and enhance the broader applicability of the study findings.

Overall, our data further corroborate the effectiveness of PuraStat as both a treatment modality for both hemostasis and bleeding prevention for the indication for which it is currently approved. Moreover, for the first time, our study provides additional evidence of the efficacy and safety of PuraStat for indications different from the ones for which it is currently approved, such as treatment and prevention of bleeding related to ERCP with sphincterotomy, endoscopic papillectomy, radiation proctopathy, GAVE, EUS-guided WOPN drainage, and pneumatic dilation of colorectal anastomoses.

Conclusions

In conclusion, PuraStat appears to be a safe and effective addition to the endoscopic therapeutic armamentarium for both hemostasis and bleeding prevention, with more and more evidence suggesting a potentially wider number of applications compared with current indications. As a consequence, clinical data from further studies are needed to expand the indications for use of PuraStat and its place in the therapeutic bleeding algorithms.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Correction.

Efficacy of novel endoscopic hemostatic agent for bleeding control and prevention: Results from a prospective, multicenter national registry Roberta Maselli, Leonardo Da Rio, Mauro Manno et al. Endoscopy International Open 2024; 12: E1220–E1229. DOI: 10.1055/a-2406-7492 In the above-mentioned article institution 8 and 9 were corrected. This was corrected in the online version on 14.11.2024.

References

- 1.Oakland K. Changing epidemiology and etiology of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;42:101610. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gralnek IM, Stanley AJ, Morris AJ et al. Endoscopic diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (NVUGIH): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline – Update 2021. Endoscopy. 2021;53:300–332. doi: 10.1055/a-1369-5274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Triantafyllou K, Gkolfakis P, Gralnek IM et al. Diagnosis and management of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2021;53:850–868. doi: 10.1055/a-1496-8969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mourad FH, Leong RW. Role of hemostatic powders in the management of lower gastrointestinal bleeding: A review: Hemostatic agents lower intestinal bleed. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33:1445–1453. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vitali F, Naegel A, Atreya R et al. Comparison of Hemospray and Endoclot for the treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:1592–1602. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i13.1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang T, Zhong X, Wang S et al. Molecular mechanisms of RADA16–1 peptide on fast stop bleeding in rat models. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:15279–15290. doi: 10.3390/ijms131115279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung JP, Gasiorowski JZ, Collier JH. Fibrillar peptide gels in biotechnology and biomedicine. Biopolymers. 2010;94:49–59. doi: 10.1002/bip.21326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giritharan S, Salhiyyah K, Tsang GM et al. Feasibility of a novel, synthetic, self-assembling peptide for suture-line haemostasis in cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;13:68. doi: 10.1186/s13019-018-0745-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masuhara H, Fujii T, Watanabe Y et al. Novel infectious agent-free hemostatic material (TDM-621) in cardiovascular surgery. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;18:444–451. doi: 10.5761/atcs.oa.12.01977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stenson KM, Loftus IM, Chetter Iet al. A multi-centre, single-arm clinical study to confirm safety and performance of PuraStat, for the management of bleeding in elective carotid artery surgery Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 20222810760296221144307 10.1177/10760296221144307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedland Y, Bagot d’Arc M, Ha J et al. The use of self-assembling peptides (PuraStat) in functional endoscopic sinus surgery for haemostasis and reducing adhesion formation. A case series of 94 patients. Surg Technol Int. 2022;42:sti41/1594. doi: 10.52198/22.STI.41.GS1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee MF, Ma Z, Ananda A. A novel haemostatic agent based on self-assembling peptides in the setting of nasal endoscopic surgery, a case series. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;41:461–464. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong E, Ho J, Smith M et al. Use of Purastat, a novel haemostatic matrix based on self-assembling peptides in the prevention of nasopharyngeal adhesion formation. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2020;70:227–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2020.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nahm CB, Popescu I, Botea F et al. A multi-center post-market clinical study to confirm safety and performance of PuraStat in the management of bleeding during open liver resection. HPB (Oxford) 2022;24:700–707. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2021.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stefan S, Wagh M, Siddiqi N et al. Self-assembling peptide haemostatic gel reduces incidence of pelvic collection after total mesorectal excision: Prospective cohort study. Ann Med Surg. 2021;68:102553. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pioche M, Camus M, Rivory J et al. A self-assembling matrix-forming gel can be easily and safely applied to prevent delayed bleeding after endoscopic resections. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4:E415–E419. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-102879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subramaniam S, Kandiah K, Thayalasekaran S et al. Haemostasis and prevention of bleeding related to ER: The role of a novel self‐assembling peptide. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:155–162. doi: 10.1177/2050640618811504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subramaniam S, Kandiah K, Chedgy F et al. A novel self-assembling peptide for hemostasis during endoscopic submucosal dissection: a randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2021;53:27–35. doi: 10.1055/a-1198-0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Branchi F, Klingenberg-Noftz R, Friedrich K et al. PuraStat in gastrointestinal bleeding: results of a prospective multicentre observational pilot study. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:2954–2961. doi: 10.1007/s00464-021-08589-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Nucci G, Reati R, Arena I et al. Efficacy of a novel self-assembling peptide hemostatic gel as rescue therapy for refractory acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2020;52:773–779. doi: 10.1055/a-1145-3412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubo K, Hayasaka S, Tanaka I. Endoscopic hemostatic treatment for acute gastrointestinal bleeding by combined modality therapy with PuraStat and endoscopic hemoclips. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2023;17:89–95. doi: 10.1159/000528896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gagliardi M, Oliviero G, Fusco M et al. Novel hemostatic gel as rescue therapy for postsphincterotomy bleeding refractory to self-expanding metallic stent placement. ACG Case Rep J. 2022;9:e00744. doi: 10.14309/crj.0000000000000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishida Y, Tsuchiya N, Koga T et al. A novel self-assembling peptide hemostatic gel as an option for initial hemostasis in endoscopic sphincterotomy-related hemorrhage: a case series. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2022;15:1210–1215. doi: 10.1007/s12328-022-01702-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uba Y, Ogura T, Ueno S et al. Comparison of endoscopic hemostasis for endoscopic sphincterotomy bleeding between a novel self-assembling peptide and conventional technique. J Clin Med. 2022;12:79. doi: 10.3390/jcm12010079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogura T, Uba Y, Yamamura M et al. Endoscopic hemostasis using self-expandable metal stent combined with PuraStat for patient with high risk of post-endoscopic sphincterotomy bleeding (with video) Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2024;23:94–96. doi: 10.1016/j.hbpd.2023.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto K, Sofuni A, Mukai S et al. Use of a novel self‐assembling hemostatic gel as a complementary therapeutic tool for endoscopic sphincterotomy‐related bleeding. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2022;29:e81–e83. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyano A, Ogura T, Nishikawa H. Noninvasive endoscopic hemostasis technique for post‐papillectomy bleeding using a novel self‐assembling peptide (with video) JGH Open. 2023;7:81–82. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamamoto K, Tsuchiya T, Tonozuka R et al. Novel self‐assembling hemostatic agent with a supportive role in hemostatic procedures for delayed bleeding after endoscopic papillectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2023;30:e22–e24. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Misumi Y, Takeuchi M, Kishino M et al. A case of gastric antral vascular ectasia in which PuraStat, a novel self‐assembling peptide hemostatic hydrogel, was effective. DEN Open. 2023;10:e183. doi: 10.1002/deo2.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White K, Henson CC. Endoscopically delivered Purastat for the treatment of severe haemorrhagic radiation proctopathy: a service evaluation of a new endoscopic treatment for a challenging condition. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2021;12:608–613. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2020-101735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Binda C, Fugazza A, Fabbri S et al. The use of PuraStat in the Management of walled-off pancreatic necrosis drained using lumen-apposing metal stents: a case series. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023;59:750. doi: 10.3390/medicina59040750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gagliardi M, Sica M, Oliviero G et al. Endoscopic application of Purastat in the treatment of solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2021 doi: 10.15403/jgld-3680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soriani P, Biancheri P, Deiana S et al. Off-label PuraStat use for the treatment of acute intrahepatic biliary duct bleeding. Endosc Int Open. 2021;9:E1926–E1927. doi: 10.1055/a-1608-0931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakahara K, Michikawa Y, Sato J et al. A novel self‐assembling peptide hemostatic gel as rescue therapy for fistula bleeding after endoscopic ultrasound‐guided hepaticogastrostomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2023;30:e66–e67. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kubo K. Delayed bleeding following percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy successfully treated with PuraStat. Intern Med. 2023;62:487–488. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.9746-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]