Abstract

A simple and effective method based upon semi-specific PCR followed by cloning has been developed. Chromosomal mapping of the generated fragment on a somatic cell hybrid panel identifies the chromosomal position, and yields a unique sequence tag for the site. Using this method, the chromosomal location of one porcine endogenous retrovirus (PERV) was determined. The porcine genomic sequences were first amplified by PCR using a PERV-specific primer and a porcine short interspersed nuclear element (SINE)-specific primer. PCR products were cloned, and those sequences that contained PERV plus flanking regions were selected using a second round of PCR and cloning. Sequences flanking the PERV were determined and a PERV-B was physically mapped on porcine chromosome 17 using a somatic hybrid panel. The general utility of the method was subsequently demonstrated by locating PERVs in the genome of PERV infected human 293 cells. This method obviates the need for individual library construction or linker/adaptor ligation, and can be used to quickly locate individual sites of moderately repeated, dispersed DNA sequences in any genome.

INTRODUCTION

Mapping individual sites of elements with multiple genomic locations is a major challenge in biomedical research. Conventional mapping methods involve construction of a chromosomal linkage map (1,2), or require a genomic library (3) to facilitate physical mapping. In this study, we report the development of a new strategy based upon semi-specific PCR that ‘walks’ into unknown unique flanking regions of a specific genomic sequence, obviating the need for genomic library construction. The unique flank is then mapped physically using an established somatic hybrid panel. Unlike techniques that use double-stranded vectorette linkers (4), oligonucleotide adaptors (5), ligation-mediated PCR (6), or dGTP/dCTP tailing (7), this method does not require any restriction digestion, and linker or adaptor ligation step.

In this system, the region flanking the target sequence is first enriched by primer extension using an outward-facing, specific antisense (or sense) primer close to the 5′-end (or 3′-end) of the known sequence. PCR amplification is then performed on the extended products using this primer, in conjunction with a primer corresponding to a repeat element known to be present throughout the genome, such as short interspersed nuclear element (SINE) or long interspersed nuclear element (LINE) repeats. After cloning, and a second round of PCR, the target sequence with its flanking region is selected and sequenced, and subsequently mapped physically to a specific chromosome using a somatic hybrid panel.

The usefulness of this method was demonstrated by mapping a porcine endogenous retrovirus (PERV) on a Large White × Landrace crossbred pig. It has been estimated that a pig genome has an average of 50 copies of PERV, which are transmitted through the germ line (8). At least three types of PERVs (A, B and C) have been shown to infect human cell lines in vitro (9,10). Studies using immunosuppressed mouse models by van der Laan et al. (11) and our group (12) revealed that PERV could be transmitted to mouse cells in vivo. One way to minimize possible cross-species PERV transmission is to breed pig herds with reduced copies of PERV. Mapping of PERV locations on the pig genome provides useful information for breeding pigs with fewer PERVs, and for characterizing individual PERVs. Our method provides a way to map PERVs on pig genome without library construction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pig and human cells

The pig used in this study was Large White × Landrace (Bunge Meat Industries, Corowa, NSW, Australia). The human cell line 293 productively infected with PERV was kindly provided by Prof. R. Weiss and Dr Y. Takeuchi (London, UK).

DNA preparation, primer extension and PCR

Preparation of genomic DNA from pig and human cells was performed using a Puregene DNA isolation kit (Gentra Inc., Minneapolis, MN) as previously described (12). Primer extension was performed on 1 µg genomic DNA using Ventexo– DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI). The DNA template was first denatured at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 40 s at 62°C, 3 min at 72°C, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. PCR was performed using Taq DNA polymerase (Promega). The cycling conditions were denaturation at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55–60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s to 3 min (depending on the size of PCR products) and a final 72°C for 5 min. Both primer extension and PCR were performed on a Perkin-Elmer Cetus 9600 Thermal Cycler (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA).

DNA cloning, sequence analysis and somatic hybrid mapping

PCR products were cloned into pGEM-T vector according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Promega). PCR products were sequenced on both strands using an ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Perkin-Elmer) and a 377 DNA sequencing system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Sequence data were analyzed using BLAST (13), BestFit (14) and Clustal W (15) programs. The nucleotide sequence of the pig genomic DNA reported in this study has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF286463.

Mapping of a PERV on the pig genome was carried out using a human–rodent somatic cell hybrid panel following a standard protocol (16). The statistical algorithm used was as described by Chevalet et al. (17).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Cloning of PERV flanking regions from pig genomic DNA

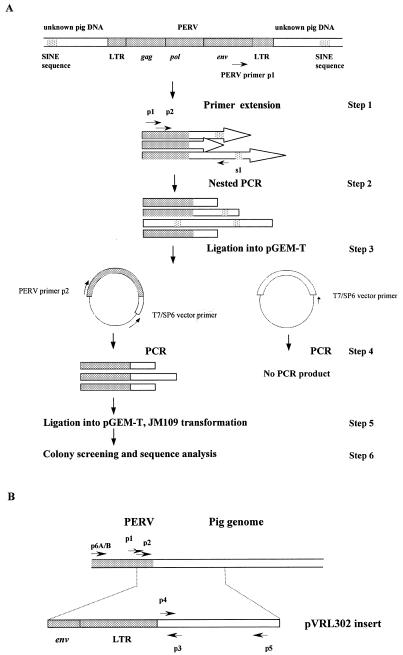

The overall strategy is outlined in Figure 1A. PERV-specific sequences in the pig template population were selectively enriched by primer extension with an outward-facing PERV-specific primer p1 (5′-CGAGTGAGTGCAGTCCAGATCA-3′) located in close proximity to the 3′-end of the PERV-conserved sequence (step 1). The PERV-enriched DNA pool was then amplified using PCR with PERV-specific primer p1, and primer s1 (5′-ACTATCGATATGCCGCGGGTGTGGCC-3′) corresponding to porcine SINE116 (18) (step 2). The sensitivity and specificity of the PCR was improved by semi-nesting using another PERV-specific primer p2 (5′-AAGACAAGAAGTGGGGAATG-3′), located downstream of primer p1 within the PERV-env region (Fig. 1B). Amplicons that were not PERV-related, due to amplification from the single SINE116 primer, were minimized by ligating the PCR products into pGEM-T (step 3), then amplifying the ligated DNA using the PERV-specific primer p2, and the vector specific primer T7 (or SP6) (step 4). Hence, only the vector containing PERV sequences could be amplified. A pool of PCR products of varying sizes obtained was ligated into pGEM-T, and transformed in Escherichia coli JM109 (step 5). Transformants were screened for the presence of PERV sequences by PCR using the PERV-specific primer p2 and the T7/SP6 vector primer (step 6). Thirteen of 24 colonies screened were found to be PERV positive. Seven of the 13 generated a PCR product of >400 bp. The expected distance between the p2 primer and the end of the long terminal repeat (LTR) is ~400 bp, and hence only the seven clones that produced a PCR product of >400 bp were considered positive and likely to contain flanking sequences. One clone, designated pVRL302, was characterized further, and the PCR product of 610 bp was sequenced. The 610 bp insert of pVRL302 consisted of a 21 bp sequence from the 3′-end of PERV-env sequence, a 423 bp complete LTR and a 166 bp sequence with no homology to any sequences in current databases.

Figure 1.

Amplification and cloning of regions flanking PERVs in the pig genome. The shaded bars represent a PERV sequence, the open bars represent the unknown pig genome sequences flanking the PERV, and the cross-hatched area represents SINE sequences. The long arrows represent primer extension products, and short arrows the PCR primers. (A) Overall procedure. Step 1: primer extension on pig DNA using PERV-specific primer (p1). Step 2: PCR using PERV and SINE primers (p1, p2 and s1). Step 3: PCR products are cloned into a suitable vector (pGEM-T). Step 4: PCR of the ligation mixture using PERV (p2) and vector primers (T7/SP6). Step 5: PCR products are cloned into a suitable vector (pGEM-T). Step 6: screening of colonies for PERV positive clones and sequence confirmation. (B) Locations of PCR primers on the region containing part of PERV with its downstream flanking sequence. The fragment that was cloned in pVRL302 is shown underneath. (C) Amplification products from Large White × Landrace pig DNA. PCR was performed using primers p1 and p3 (lane 2), PERV-A specific primer p6A and primer p3 (lane 3), PERV-B specific primer p6B and primer p3 (lane 5). Water controls were included for each PCR (lanes 1, 4 and 6). M, molecular weight marker (pGEM DNA marker).

Confirmation of the PERV flanking sequence

The origin of the unknown 166 bp sequence of pVRL302 was determined by PCR using p1 and an antisense primer p3 (5′-GGATGGGGAAAGGTAGCAGGTG-3′) congruent with the unknown sequence (Fig. 1B). A PCR product of the expected size (470 bp) was obtained (Fig. 1C, lane 2), confirming that the unknown sequence in pVRL302 was the sequence from the pig genome downstream of the PERV. The primer p3 was also used together with a PERV-A primer p6A (5′-AGCACTCAAGGGGAGGCTC-3′), or a PERV-B primer p6B (5′-CGAGGTGTTGCTCCTAGAG-3′) in separate experiments. Only the combination of p6B and p3 generated the expected 2.6 kb PCR product (Fig. 1C, lane 5), demonstrating that pVRL302 contained part of a PERV-B sequence and the flanking sequence from the pig genome.

Somatic hybrid mapping of the cloned PERV-B sequence

The PERV-B insertion site in the pig genome was determined by mapping the junction fragment using a somatic hybrid panel (16). Another primer pair p4 (5′-TCACACCACCTGCTACCTTTCC-3′) and p5 (5′-TCTGATGTGCCAACTGTGATTA-3′) was designed within the genomic region flanking the PERV-B (Fig. 1A) and PCR was carried out on the somatic cell hybrid panel DNA. Only hybrid cell lines 21 and 22 of the 27 clone porcine–rodent somatic cell panel, harboring the region (1/2 q2.1–q2.3) of pig chromosome 17, revealed amplification of the PERV junction fragment PCR product (Fig. 2). Thus the PERV could unambiguously be mapped to this segment (error risk <0.5%, correlation 1.0, chromosomal probability 0.98, regional probability 0.87) (17).

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the location of the PCR product on the chromosome. PCR product with expected size was generated from two out of the 27 porcine–rodent somatic hybrid clones (indicated by +). The proportion of pig chromosome 17 retained in each of the 27 somatic hybrid clones is shown as a solid bar.

During this study, the locations of 22 PERVs on the genome of a Large White pig, using the BAC library construction and fluorescence in situ hybridization screening method, were published (3). The location of PERV-B mapped in this study was consistent with the location of one PERV-B sequence mapped to porcine chromosome 17q2.1 in the Large White pig (3). Therefore no further characterization of the other clones was carried out in this study.

Cloning of human genomic sequences flanking PERV from a PERV-infected human cell line

The efficiency of this method in characterizing unknown sequences flanking a known sequence from genomic DNA was further evaluated using the human cell line 293. The 293 cells were productively infected with PERV-B (10), and the cells were expected to contain fewer copies of PERV than pig cells. A primer corresponding to the human alu sequence was used together with PERV-specific primers to determine the location of PERV-B in the 293 cells using the method described above. Four positive clones were obtained which contained part of the PERV sequence, plus 20–434 bp PERV downstream sequences. Sequence analysis revealed that the downstream regions all belong to the human genomic sequence (data not shown).

In summary, the strategy outlined above has been used successfully to clone PERV flanking sequences from genomes of the pig and PERV-infected human cells. The method provides a unique sequence tag for more precise mapping of the sequences, and has allowed the location of the specific PERV-B sequence in the pig genome. The method can also be used to locate any sequence with multiple copies in a eukaryotic genome, if the sequence information from the target sequence and another dispersed repeat such as a SINE (or LINE) is available. This technique is extremely useful to locate novel insertion sites resulting from integration of a retrovirus into the genome of a xenotransplantation recipient, without the need for library construction.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Prof. Robin Weiss and Dr Yasuhiro Takeuchi for providing PERV-infected human 293 cell line. The work was supported by Juvenile Diabetes Foundation International (JDFI) Postdoctoral Fellowship to Y.-M. D., the South Eastern Area Laboratory Service and the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation Australia (JDFA).

DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession no. AF286463

REFERENCES

- 1.Frankel W.N., Stoye,J.P., Taylor,B.A. and Coffin,J.M. (1990) Genetics, 124, 221–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tereba A. (1983) Curr. Topics Microbiol. Immunol., 107, 29–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogel-Gaillard C., Bourgeaux,N., Billault,A., Vaiman,M. and Chardon,P. (1999) Cytogenet. Cell Genet., 85, 205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenthal A. and Jones,D.S.C. (1990) Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 3095–3096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siebert P.D., Chenchik,A., Kellogg,D.E., Lukyanov,K.A. and Lukyanov,S.A. (1995) Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 1087–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prodhom G., Lagier,B., Pelicic,V., Hance,A.J., Gicquel,B. and Guilhot,C. (1998) FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 158, 75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt W.M. and Mueller,M.W. (1996) Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 1789–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patience C., Takeuchi,Y. and Weiss,R.A. (1997) Nature Med., 3, 282–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Tissier P., Stoye,J.P., Takeuchi,Y., Patience,C. and Weiss,R.A. (1997) Nature, 389, 681–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeuchi Y., Patience,C., Magre,S., Weiss,R.A., Banerjee,P.T., Letissier,P. and Stoye,J.P. (1998) J. Virol., 72, 9986–9991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Laan L.J.W., Lockey,C., Griffeth,B.C., Frasier,F.S., Wilson,C.A., Onions,D.E., Hering,B.J., Long,Z.F., Otto,E., Torbett,B.E. and Salomon,D.R. (2000) Nature, 407, 90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng Y.-M., Tuch,B. and Rawlinson,W. (2000) Transplantation, 70, 1010–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altschul S.F., Gish,W., Miller,W., Myers,E.W. and Lipman,D.J. (1990) J. Mol. Biol., 215, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Needleman S.B. and Wunsch,C.D. (1970) J. Mol. Biol., 48, 443–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson J.D., Higgins,D.G. and Gibson,T.J. (1994) Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yerle M., Robic,A. and Renard,C. (1996) Anim. Genet., 27, 217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chevalet C., Gouzy,J. and SanCristobal-Gaudy,M. (1997) Comp. Appl. Biosci., 13, 69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller J.R. (1994) Mamm. Genome, 5, 629–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]