Abstract

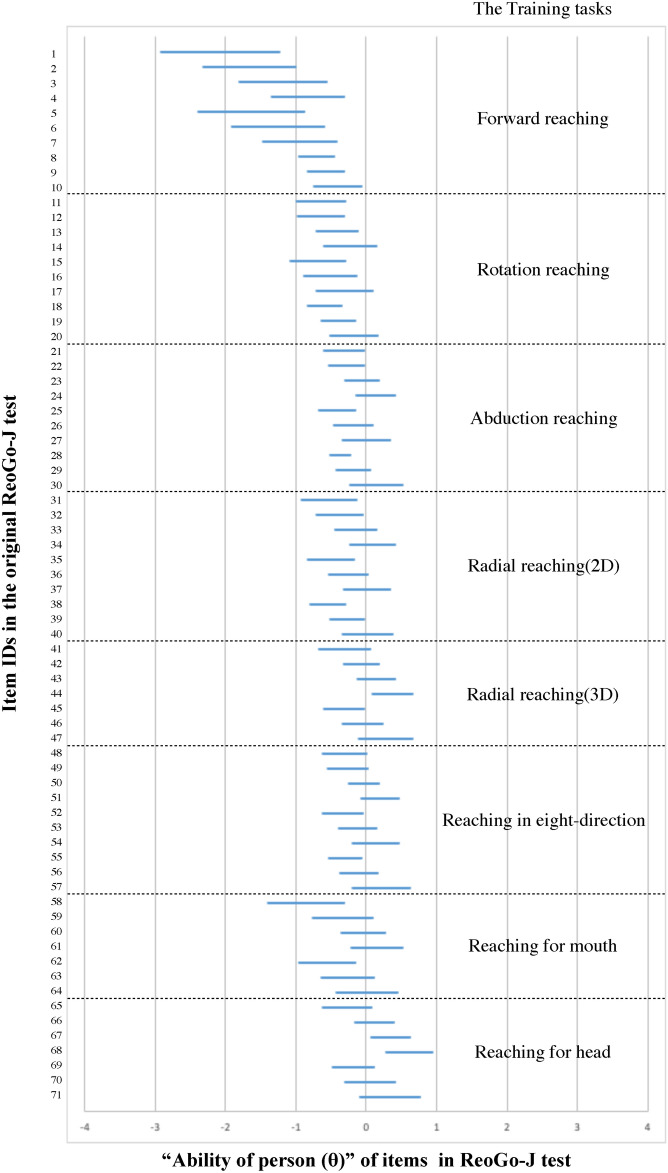

Stroke-induced upper-extremity paralysis affects a substantial portion of the population, necessitating effective rehabilitation strategies. This study aimed to develop an automated program, incorporating the item response theory, for rehabilitation in patients with post-stroke upper-extremity paralysis, focusing on the ReoGo-J device, and to identify suitable robot parameters for robotic rehabilitation. ReoGo-J, a training device for upper-extremity disorders including 71 items, was administered to over 300 patients with varying degrees of post-stroke upper-extremity paralysis. Each item was rated on a three-point scale (0, very difficult; 1, adequate; 2, very easy). The results were analyzed using the graded response model, an extension of the two-parameter logistic model within the framework of the item response theory, to grade the training items based on ability of the patients. The relationship between the predicted ability, an indicator of the predicted ability the paralyzed upper-extremity to perform an item in the item response theory analysis (higher numbers indicate higher ability, lower numbers indicate lower ability), and the items in the Fugl–Meyer assessment (FMA), which indicate the degree of paralysis, was analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. This study included 312 patients with post-stroke upper-extremity paralysis. The predicted ability (θ) of the tasks included in the original ReoGo-J test for forward reaching, reaching for mouth, rotational reaching, radial reaching (2D), abduction reaching, reaching in eight directions, radial reach (3D), and reaching for head ranged from − 2.0 to − 0.8, − 1.3 to − 0.8, − 1.0 to − 0.1, − 0.7 to 0.3, − 0.2 to 0.4, − 0.4 to 0.6, − 0.1 to 0.6, and 0.5 to 0.6, respectively. Significantly high correlations (r = 0.80) were observed between the predicted ability of all patients and the upper-extremity items of shoulder-elbow-forearm in the FMA. We have introduced an automated program based on item response theory and determined the order of difficulty of the 71 training items in ReoGo-J. The strong correlation between the predicted ability and the shoulder-elbow-forearm items in FMA may be used to ameliorate post-stroke upper-extremity paralysis. Notably, the program allows for estimation of appropriate ReoGo-J tasks, enhancing clinical efficiency.

Trial registration: https://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/index-j.htm (UMIN000040127).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-74672-2.

Keywords: Two-parameter logistic model, Robotic rehabilitation, Stroke, Upper extremity, Arm, Shoulder, ReoGo-J

Subject terms: Engineering, Clinical trials

Background

Stroke was a leading cause of physical disability worldwide, with long-term upper extremity (UE) disability affecting approximately 65% of patients after stroke1. While some patients regained independence in daily activities within a few months of stroke onset, the majority rely predominantly on the non-paralyzed UE for daily tasks2.

Rehabilitation programs could improve the function of the paralyzed UE, even in the chronic phase (more than six months after stroke)3,4. Among these, robot-assisted training has shown promise in helping patients with moderate to severe UE paralysis to improve function and integrate the use of the paralyzed UE into daily life.

Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs), systematic reviews, and meta-analyses have demonstrated the efficacy of robot-assisted training for subacute and chronic post-stroke UE disorders5,6. However, part of RCTs have reported no significant differences in UE function improvement between robot-assisted training and conventional rehabilitation7,8. These inconsistencies suggest that several factors may influence the effectiveness of robot-assisted training.

One such factor was the amount of robotic assistance provided. Excessive assistance could reduce the voluntary movement effort of the paralyzed UE, potentially leading to “slack”9, a condition that could hinder motor learning. Some studies advocated adjusting robotic assistance based on the severity of motor impairment in the paralyzed UE10–12. These findings highlighted the importance of optimizing intervention factors, such as the appropriate level of robotic assistance, to improve UE function in post-stroke patients.

Previous research has explored two primary approaches to facilitating recovery from UE motor paralysis: promoting voluntary movements of the paralyzed UE and minimizing compensatory movements involving the trunk and other body regions associated with the paralyzed UE movement13.

An important aspect of robotic rehabilitation was likely to be the fine-tuning of compensatory trunk movements that interfere with voluntary movement of the paralyzed upper extremity. However, this fine-tuning and its assessment were often subjective and heavily dependent on the experience of the therapist, which might lead to variability in assessment and poor reproducibility.

The purpose of this study is to develop a robotic device program that can automatically select appropriate training with high objectivity for patients with upper limb paralysis due to stroke, using item response theory (IRT) that includes compensatory movements of the trunk as an analysis variable.

Methods

Data sharing

Anonymized participant data, study protocols, and analysis plans will be made available to scientific investigators upon approval by the Committee of the Investigation of ReoGo-J (Teijin Pharma Limited, Tokyo, Japan) training program with appropriate difficulty for paralyzed UE function after stroke: A prospective observational study (INDEX study). The proposals should be addressed to takshi77@omu.ac.jp or yutti@hyo-med.ac.jp. A Data Sharing Agreement must be signed by the data requester. Data requests can be made within two years of the publication of the paper.

Study design

This multicenter, prospective observational study (cross-sectional study) was performed in accordance with the STROBE guidelines across 26 hospitals and clinics in Japan that provide outpatient rehabilitation for patients after stroke. Stroke survivors in the convalescent or chronic stage were enrolled between April 2020 and April 2022.

Participants

A sample size of 300 participants was determined to be appropriate for this clinical study based on the findings of our previous simulation study14.

Patients who fulfilled the following inclusion criteria were included in this study: (1) individuals diagnosed with hemiplegia of the UEs after stroke; (2) patients who had undergone or were scheduled to undergo rehabilitation using the ReoGo-J; (3) patients admitted to a convalescent ward for a minimum duration of 2 weeks following the incidence of stroke; (4) patients aged ≥ 20 years at the time of obtaining informed consent; and (5) patients who provided written consent to participate in this study.

Patients who fulfilled any of the following criteria were excluded from the study: (1) patients with cerebellar or brainstem stroke, (2) patients with severe aphasia or significant cognitive impairment, (3) patients with severe pain in the UE, (4) patients who had lost the ability to make clear decisions, and (5) patients deemed unsuitable for inclusion in this study by the attending physician.

Data regarding demographic factors, body measurements, stroke history, post-stroke complications, lifestyle factors, and baseline functional measurements were recorded in an electronic data capture system (EDC: e-Catch, EPS Corporation, Tokyo, Japan; not directly involved in the study).

Study protocol

The ReoGo-J robotic system was used in this study. The efficacy of this system in improving the UE function has been established in two RCTs6,15.

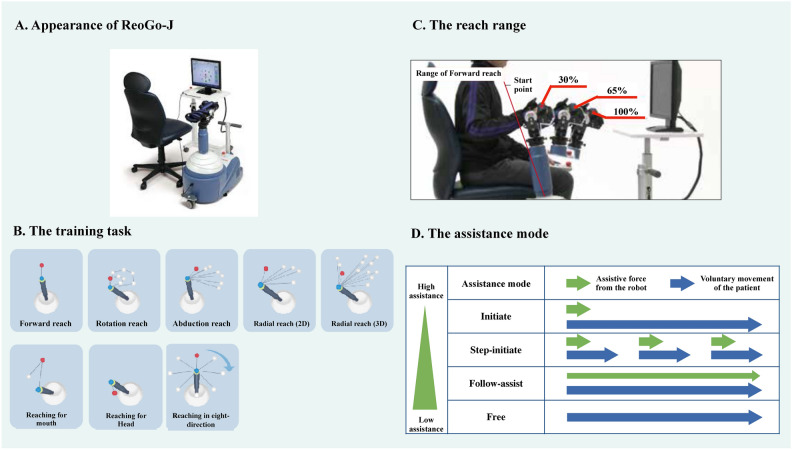

The ReoGo-J is a robotic system designed for comprehensive paralyzed UE rehabilitation, facilitating repetitive multi-directional arm movements with four levels of assistance mode (Fig. 1A). The system features a motorized robotic arm (stick) equipped with a platform to stabilize the patient’s hand, aiding in UE movement. Patients are instructed to maneuver the stick to perform point-to-point reach tasks shown on a monitor in front of them. The ReoGo-J providing visual and auditory feedback to indicate the success of the reaching movements.

Fig. 1.

Introduction of the ReoGo-J. (A) The ReoGo-J comprises a chair, a main unit with an operational stick, and a monitor positioned in front of the patients. (B) ReoGo-J has eight tasks that enable the paralyzed UE to reach in various directions. (C) ReoGo-J allows you to choose the reach range within the training task from 100%, 65%, or 30%. (D) Initiate mode, a mode in which the robot automatically assists the robot arm (stick) along a trajectory when the appropriate force is applied to the robot arm (stick) at the start of operation; Step-initiate mode, the trajectory is divided into several sections, and by applying the appropriate force at the start of each section, the robot arm (stick) moves automatically; Follow-assist, a mode in which the robot arm (stick) moves automatically at a low speed along a trajectory to assist the patient’s voluntary movement; Free mode, there is no robotic assistance; the patient operates the robotic arm (stick) using only voluntary movement . Additionally, in 3D mode, the free mode cannot be used due to the characteristics of the device’s control mechanism.

To restore the function of a paralyzed UE using the ReoGo-J in post-stroke rehabilitation, the therapist adjusted three factors (the training task, reach range, and assistance mode) to create training items tailored to the patient’s UE capabilities. These factors were adjusted as follows to create the ReoGo-J training items: (1) the training task selection: Based on the severity of UE paralysis, one appropriate task was selected from eight available options (Fig. 1B). (2) the reach range adjustment: After determining training task, the reach range within the selected task was selected according to the severity of paralysis, with options of 100%, 65%, or 30% (Fig. 1C). (3) the assistance mode Selection: After determining (1) and (2), one of four levels of robotic assistance mode was selected (Fig. 1D), also based on the severity of UE paralysis. Using the aforementioned methodology, 71 ReoGo-J training items in the original ReoGo-J test was developed for this study in consultation with occupational therapy specialists who participated in the previous study and had more than five years of experience using the ReoGo-J6,15. (Table S1).

To assess the appropriate practice for the severity of the subject’s UE paralysis from the 71 items, compensatory movements of the trunk and other parts of the body were assessed for each item. Compensatory movements involving the trunk and other body parts are often used to compensate for physical disabilities in patients with post-stroke UE impairment. These compensatory movements may indicate underlying functional issues that could hinder rehabilitation. Therefore, monitoring the compensatory movements plays a crucial role in optimizing rehabilitation programs for patients with multiple physical problems. Previous studies have reported that inhibiting these compensatory movements can improve UE function16.

Each of the 71 items of the ReoGo-J was administered to the patient, and the Quality of Compensatory Movement (QCM) score was used to detect compensatory movements of the trunk and other parts of the body. The QCM score evaluation was performed using a three-point scale, with each score indicating the following: 0 points, excessive compensatory movements, including trunk movements, and significant difficulty in paralyzed arm training (corresponding to a score of < 3.5 on the motor activity log’s quality of movement [QOM] scale17 as assessed by a therapist); 1 point, a setting that is neither difficult nor easy, thereby allowing the paralyzed hand to complete the task with some effort (corresponding to a score of 3.5–4.0 on the motor activity log’s QOM scale as assessed by the therapist); and 2 point (corresponding to a score of > 4.0 on the motor activity log’s QOM scale as assessed by the therapist, a setting where the effort required for patients to perform voluntary movements is greatly reduced due to excessive robotic assistance (corresponding to a score of > 4.0 points on the motor activity log’s QOM scale as assessed by the therapist).

The examination conducted to assess the QCM score for each of the 71 items was designated as the ReoGo-J test, and it was established as the primary outcome measure in this study. The secondary outcome measure was the assessment of UE motor function using the Fugl–Meyer assessment (FMA) scale, which encompasses various motor items for the shoulder, elbow, forearm, wrist, and finger joints, as well as coordination and velocity.

The safety endpoints encompassed identifying any untoward incidents related or unrelated to the intervention being investigated. Unfavorable incidents were meticulously documented in the medical records of patients and in a dedicated case report. The incidence of severe adverse events and malfunction was diligently compiled by the researcher and submitted to the hospital administration. These events encompassed those viewed as posing a potential threat to life or necessitating hospitalization. S2 presents the definitions and examples of serious and non-serious adverse events.

Statistical analysis

Main analysis

We employed an extending the two-parameter logistic model, the item response theory using the graded response model (2PLM-GRM-IRT) for our analysis. In general, item response theory uses “the predicted ability” called “theta (θ)” to represent the ability under analysis. In the case of a QCM score of 0 or 2 for all questions in the original ReoGo-J test (If the total original ReoGo-J score is 0 or 142 points), the predicted ability is defined as infinite due to the nature of item response theory.

In this study, the ability of the participating patients’ paralyzed UEs and the ability required to perform each item of the original ReoGo-J test were quantified using the predicted ability. After analysis, we identified the training items that are most likely to result in the QCM score of 1 point on the original ReoGo-J test, specifically for each predictive ability related to the patient’s paralyzed UE.

Adaptation of the item response theory

This study investigated the QCM score of the 71 items in the original ReoGo-J test using 2PLM-GRM-IRT. The probability of the latter category (“0 points” and “1 or 2 points”) was denoted as Pj(θ) for the QCM score of the 71 items in the ReoGo-J test. The QCM scores of the 71 items in the ReoGo-J test were divided into two categories: “0 or 1 point” and “2 points.” The probability of the “2 points” category was denoted as P’j(θ). The item discrimination and item difficulty were denoted by (a) and (b, b’), respectively. These probabilities were expressed using the following equation:

|

The index j used in this equation was the item ID in the original ReoGo-J test.

The item parameters (aj, bj, and b’j) were estimated using the marginal maximum likelihood estimation method, with the patient parameters (θ = θi) considered as the underlying population. The aj in item parameter represented item discrimination power, which refers to the ability of an item to accurately differentiate between patients’ abilities. The bj and b’j in item parameters represented item difficulty, The item parameters bj and b’j represented item difficulty, which refers to how challenging each item was.

While the patient parameter (θ = θi) refered to the predicted ability. The predicted ability were estimated using the maximum likelihood estimation method, with the item parameters (aj, bj, and b’j) obtained from the previous estimation held constant. In addition, i represented the patient ID in this study, and θi indicates the predicted ability for patient ID i. The predicted ability for all patients was listed by ID. For each of the 71 QOM scores, the item parameter estimation results were displayed, and the probability of occurrence of each point (0, 1, 2) corresponding to the predicted ability was shown an item characteristic curve (ICC). In addition, for each item, the range of the predicted ability for which the probability of occurrence of QOM 1 point was greater than 0 and 2 is obtained, and this relationship was for confirmation.

Based on an result of analysis using item response theory, the following were assessed: (1) The mean QCM score for each of the 71 items in the original ReoGo-J test, (2) the frequency and percentage of each score (0, 1, 2) for each of the 71 items in the original ReoGo-J test, (3) patients were classified into four groups based on the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of predicted ability for each item in the original ReoGo-J test, and the mean QCM score for each group was calculated. (4) we analyzed the relationship between the mean QCM score for each item on the original ReoGo-J test and the predicted ability for each patient using Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient.

Confirming the relationship between patients’ the predicted ability and UE function

The patients’ FMA scores (consisting of four sub-items: A, shoulder-elbow-forearm; B, wrist; C, finger; D, coordination and speed) and their predicted performance on all items of the ReoGo-J test were examined. The relationship between the predicted performance score and each FMA sub-item score and the total FMA score was analyzed using the Pearson correlation coefficient.

Sub-analysis

A sub-analysis was performed to confirm the assumptions of the IRT model and reconstruct a set of items for the original ReoGo-J test that were considered statistically valid.

Confirmation of one-dimensionality

The unidimensionality of the 71 items on the original ReoGo-J test assessing the predicted ability was examined for confirmation. All 71 items in the original ReoGo-J test were systematically combined into all possible two-item combinations. Polychoric correlation coefficients were calculated for each combination and a correlation coefficient matrix was constructed subsequently. All eigenvalues were extracted from this matrix, and the top five eigenvalues were identified (factor analysis). The ratio of each eigenvalue to the sum of all eigenvalues was calculated to evaluate the eigenvalues. This ratio facilitated the assessment of the proportion of variance explained by each eigenvalue. The ratio of the first eigenvalue was examined to ensure that it was sufficiently large to indicate a significant contribution to the overall variance.

In addition, the ratio of the second eigenvalue was also scrutinized to ensure that it was relatively small to indicate a diminishing contribution compared with that of the first eigenvalue. The unidimensionality was not confirmed, and the underlying factors were investigated further through factor analysis if the second and subsequent eigenvalues were substantial. This analysis helped identify the specific causes underlying the larger eigenvalues. Reducing the number of non-conforming items in the the original ReoGo-J test was considered to improve the unidimensionality of the assessment. In addition, data analysis was conducted by dividing the dataset based on relevant factors. Moreover, the possibility of utilizing a two-factor model for further analysis was also explored, considering the potential presence of multiple underlying factors influencing the test results.

Confirmation of monotonicity

For each item in the original ReoGo-J test, patients were classified into four groups based on the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of predicted ability, and the mean QCM score for each group was calculated. To confirm the monotonicity for all items, it was ensured that the mean QCM score of the higher percentile group was not less than that of the lower percentile group. Additionally, we analyzed the relationship between the mean QCM score for each item on the original ReoGo-J test and the predicted ability for each patient using Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient.

Confirmation of local independence

To confirm the local independence of the 71 items in the original ReoGo-J test, we utilized Q3 statics and other metrics to assess local independence. Yen et al.18, suggested to identify the causes of item similarity and address them by scaling the dependent causes together and separately. If the Q3 statistic exceeds 0.3619 for a particular combination, the items are considered similar.

Therefore, in this study, if local independence among the 71 items in the original ReoGo-J test could not be ensured, the following method would be implemented to take appropriate corrective action. It was anticipated from the research design stage that there would be a group of similar items with the same “training task” and “assist mode” but different “reach ranges” (The training task, reach range, and assist mode were the three factors adjusted when creating the training items).

For the modified ReoGo-J test (S3), we developed an integrated scale for each “training task”. The modified ReoGo-J test utilized a 21- or 15-point Likert scale to evaluate each of the eight items, as outlined in Table 1. To confirm the local independence of the eight items in the modified ReoGo-J test, we evaluated the local independence using Q3 statistics and other indicators.

Table 1.

How to convert from the original ReoGo-J test to the modified ReoGo-J test

| The three factors of the original reogo-J test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training task | Assistance mode | Reach range | QCM score | |

| Example of 21-Likert scale items | ||||

| Forward reaching | Initiate | 65 | (0–2) | |

| Forward reaching | Step-initiate | 30 | (0–2) | |

| Forward reaching | Step-initiate | 65 | (0–2) | |

| modified ReoGo-J test | Forward reaching | Step-initiate | 100 | (0–2) |

| Item ID 1 | Forward reaching | Follow-assist | 30 | (0–2) |

| (The item ID 2, 4 and 6 were the same) | Forward reaching | Follow-assist | 65 | (0–2) |

| Forward reaching | Follow-assist | 100 | (0–2) | |

| Forward reaching | Free | 30 | (0–2) | |

| Forward reaching | Free | 65 | (0–2) | |

| Forward reaching | Free | 100 | (0–2) | |

| Total | (0–20) | |||

| Example of 15-Likert scale items | ||||

| Radial reaching(3D) | Initiate | 65 | (0–2) | |

| Radial reaching(3D) | Step-initiate | 30 | (0–2) | |

| Radial reaching(3D) | Step-initiate | 65 | (0–2) | |

| modified ReoGo-J test | Radial reaching(3D) | Step-initiate | 100 | (0–2) |

| Item ID 5 | Radial reaching(3D) | Follow-assist | 30 | (0–2) |

| (The itemID 5, 7 and 8 were the same) | Radial reaching(3D) | Follow-assist | 65 | (0–2) |

| Radial reaching(3D) | Follow-assist | 100 | (0–2) | |

| Total | (0–14) | |||

If there were problems with the local dependency of the original ReoGo-J test, created a modified version of the 8-item ReoGo-J test (modified ReoGo-J test) by combining each training item into one item without changing the test structure, and then comfirmed the local dependency of each item again.

QCM indicated Quality Compensatory Movement. Item ID 1, forward reaching; ID 2, rotation reaching; ID 3, Abduction reaching; ID 4, Radial reaching(2D); ID 5, Radial reaching(3D); ID 6, Reaching in eight-direction; ID 7, Reaching for mouth; ID 8, Reaching for head.

Consideration of exclusion of low-contributing assessment items

As a result of the 2PLM-GRM-IRT analysis, the correlation coefficients between the scores of each test item in the original ReoGo-J test and the predicted ability reflecting the patient’s paralyzed UE function were evaluated. If the correlation coefficient was judged to be significantly low (r < 0.4), the cause was investigated. If an inappropriate cause was identified, it was excluded from the original ReoGo-J test.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

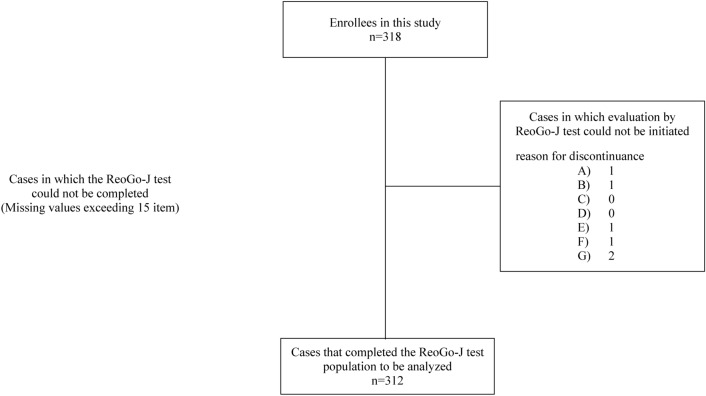

Among the 318 patients screened, 312 were eligible for inclusion in this study. Figure 2 presents the reasons for discontinuing participation. We identified 312 prospective candidates with acute, subacute, and chronic post-stroke UE paresis who were undergoing treatment at collaborating rehabilitation centers (Table 2). The patients were enrolled in 22 clinics and hospitals between April 1, 2020, and April 30, 2021.

Fig. 2.

Study flowchart. (A) If it is discovered after the research has started that the selection criteria are not met or that the exclusion criteria are applicable, (B) If the subject requests to stop the experiment, (C) If it becomes difficult for the subject to participate in this study due to circumstances beyond their control. (D) If the principal investigator decides that the study should be terminated due to the occurrence of an adverse event, (E) If the principal investigator deems it inappropriate to continue this research for reasons other than those listed above, (F) If it is impossible to track after registration. (G) If you were unable to complete the original ReoGo-J test (more than 15 missing values).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | Category | Number of cases (312) | Average (standard deviation) | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | – | 312 | 60.99 (13.03) | – |

| Time from onset (year) | – | 312 | 1.48 (2.86) | – |

| FIM (motor) | – | 311 | 74.2 (14.4) | – |

| FIM (cognition) | – | 312 | 31.2 (4.2) | – |

| Sex | Male | 208 | – | 66.7 |

| Female | 104 | – | 33.3 | |

| Dominant hand | Right | 303 | – | 97.1 |

| Left | 9 | – | 2.9 | |

| First/recurrent stroke | First stroke | 288 | – | 92.3 |

| Recurrent stroke | 24 | – | 7.7 | |

| Causes of stroke | Cerebral infarction | 166 | – | 53.2 |

| Cerebral hemorrhage | 144 | – | 46.2 | |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 2 | – | 0.6 | |

| Transient ischemic attack | 0 | – | 0.0 | |

| Recuperative hospitalization | Yes | 275 | – | 88.4 |

| No | 36 | – | 11.6 | |

| History of botulinum toxin administration | Yes | 29 | – | 9.3 |

| No | 279 | – | 89.4 | |

| Unknown | 4 | – | 1.3 | |

| Paralyzed side | Right | 152 | – | 48.7 |

| Left | 160 | – | 51.3 | |

| Language comprehension disorder | Yes | 29 | – | 9.3 |

| No | 283 | – | 90.7 | |

| Visual field impairment | Yes | 4 | – | 1.3 |

| No | 308 | – | 98.7 | |

| Brunnstrom stage (paralyzed upper-extremity) | I | 0 | – | 0.0 |

| II | 25 | – | 8.0 | |

| III | 95 | – | 30.4 | |

| IV | 77 | – | 24.7 | |

| V | 95 | – | 30.4 | |

| VI | 20 | – | 6.4 | |

| Brunnstrom stage (paralyzed finger) | I | 4 | – | 1.3 |

| II | 49 | – | 15.8 | |

| III | 75 | – | 24.1 | |

| IV | 69 | – | 22.2 | |

| V | 91 | – | 29.3 | |

| VI | 23 | – | 7.4 | |

| Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project (OCSP) classification | Total anterior circulation infarcts (TACI) | 97 | – | 31.1 |

| Partial anterior circulation infarcts (PACI) | 93 | – | 29.8 | |

| Posterior circulation infarcts (POCI) | 17 | – | 5.4 | |

| Lacunar circulation infarcts (LACI) | 105 | – | 33.7 |

Result of the main analysis

Adaptation of the item response theory in the original Reogo-J test

S4 showed the frequencies and percentages of QCM scores (0, 1, and 2) for each of the 71 items in the original ReoGo-J test. Also shown were the mean QCM scores for all items and for each of the four categories based on the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of predicted ability. In addition, correlation coefficients were shown for the relationship between the predicted ability and QCM score for each item.

S5 presents the item parameter estimated, such as difficulty (b, b’), and discrimination (a) from the ICC, which showed the probability of each QCM score (0, 1, and 2) corresponding to the ability value θ for the 71 items. Furthermore, the predicted ability of the patients in this study was presented in S6. The mean ± standard deviation of the predicted ability was − 0.026 ± 0.977, with a minimum value of − 3.080 and a maximum value of 1.600. Approximately 93% of the patients’ predicted abilities fell within the range of − 2.0 ≤ θ ≤ 2.0. These suggested that the original ReoGo-J test exhibited high measurement accuracy for patients with predicted ability within this range of characteristic values.

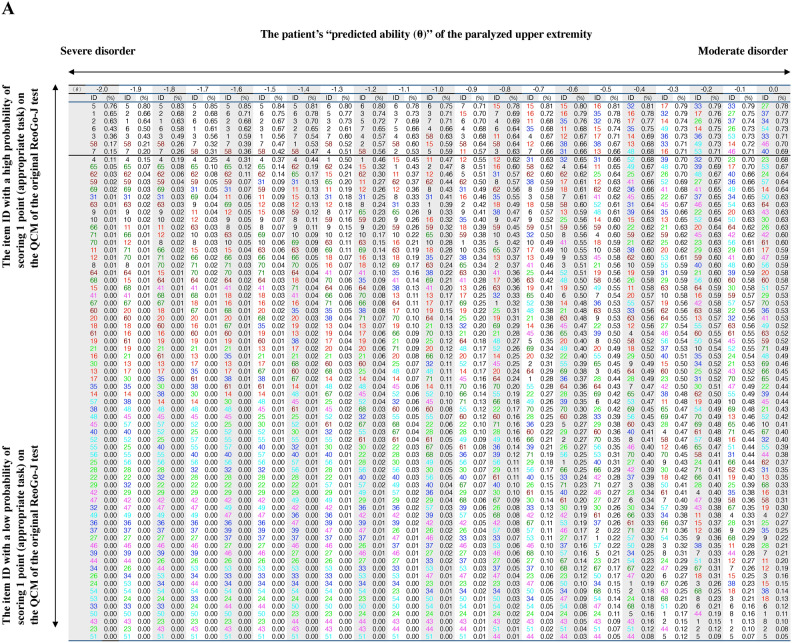

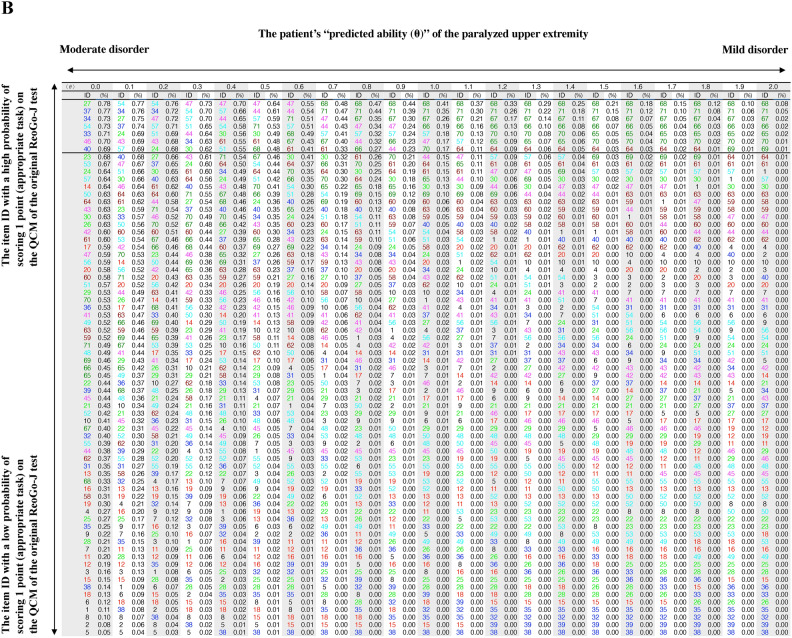

Figure 3A and B presented the item IDs in descending order of the probability of scoring 1 point on the QCM score, based on each patient’s predicted ability. The item IDs in the original ReoGo-J test listed at the top of the Table 3 indicate the items that are most likely to score 1 point in the QCM score. Furthermore, when the patient’s prediction ability was greater than 0.7, there were no item IDs with a probability of obtaining a QCM score of 1 greater than 50%. In Figs. 3A and 3B, we examined the minimum and maximum predictive abilities when each training item was in the top 7 and the probability of obtaining a QCM score of 1 point on the original Reogo-J test was greater than 50%. The results showed that for forward reaching, reaching for mouth, rotational reaching, radial reaching (2D), abduction reaching, reaching in eight directions, radial reaching (3D), and reaching for head, θ, which indicates the predictive ability of patients to adapt to the training tasks included in the original ReoGo-J test, was − 2.0 to − 0.8, − 1.3 to − 0.8, − 1.0 to − 0.1, − 0.7 to 0.3, − 0.2 to 0.4, − 0.4 to 0.6, − 0.1 to 0.6, and 0.5 to 0.6, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Training item ID for the original ReoGo-J test, which was suitable for the patient’s predicted ability. (A) showed the range from − 2.0 to 0 for the predicted ability (θ). (B) showed the range from 0 to 2.0 for the predicted ability (θ). The colors in the figure indicate the type of training task: black, forward reaching; red, rotation reaching; light green, Abduction reaching; Blue, Radial reaching(2D); pink, Radial reaching(3D); light blue, reaching in eight-direction; brown, reaching for mouth; green, reaching for head.

Table 3.

Relationship between upper-extremity movement items of FMA and the predicted ability of patients.

| Outcome | Distribution of the predicted ability of patients | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 25% point patients | Between 25% point ≤ , and < 50% point patients | Between 50% point ≤ , and < 75% point patients | 75% ≤ point patients | All patients | ||||||||

| Number of cases | Average | Number of cases | Average | Number of cases | Average | Number of cases | Average | Number of cases | Average | Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) | ||

| FMA | Total score | 78 | 16.231 | 78 | 34.269 | 78 | 48.923 | 78 | 54.013 | 312 | 38.359 | 0.77 |

| Shoulder-elbow-forearm | 78 | 12.346 | 78 | 22.359 | 78 | 29.205 | 78 | 31.462 | 312 | 23.843 | 0.80 | |

| Wrist | 78 | 1.013 | 78 | 3.795 | 78 | 6.423 | 78 | 7.769 | 312 | 4.75 | 0.67 | |

| Finger | 78 | 2.526 | 78 | 6.962 | 78 | 10.462 | 78 | 11.397 | 312 | 7.83 | 0.67 | |

| Coordination and speed | 78 | 0.346 | 78 | 1.154 | 78 | 2.833 | 78 | 3.385 | 312 | 1.92 | 0.55 | |

FMA, Fugl–Meyer assessment.

S6 showed the estimated predictive ability for each patient. Figure 4 showed the interval with the highest probability of QCM 1 point analyzed using the range of ICC for each item ID in the original ReoGo-J test.

Fig. 4.

The range of the predicted ability, where QCM scare in the original ReoGo-J test was 1 point for each item.

Confirmation of the relationship between the participant’s the predicted ability and paralyzed UE function

The correlation between the individual aptitude of the participants, denoted as the predicted ability, and paralyzed UE function, as evaluated by FMA, was investigated subsequently. Table 3 showed the mean scores for both total and individual sub-items within each category of FMA, along with correlation coefficients between the predicated ability and FMA subitem and total scores. All items showed significant correlations; however, significantly strong correlations were observed between the predicated of all patients and the FMA items of shoulder-elbow-forearm. The relationship equation between the predicated and the UE items of shoulder-elbow-forearm can be expressed as follows: θ = 0.084 × FMA shoulder-elbow-forearm score − 2.035 + error.”

Adverse events in this study

All adverse events were recorded to assess the safety of the protocols used in this study. Five adverse events were recorded during the study period. Details of the adverse events are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Safety outcomes.

| Variable | Number of events | |

|---|---|---|

| Adverse events (overall) | 5 (1.6%) |

2 Shoulder pain in a situation unrelated to this study 3 Listed under adverse events causally related to this study |

| Adverse events causally related to this study | 3 (1.0%) |

1 Fatigue and appearance of physical illness due to psychological stress after participation in this study 2 Shoulder pain appeared after participation in this study |

| Serious adverse events | 0 (0%) | |

| Device malfunctions | 0 (0%) |

Results of the sub-analysis

In confirming unidimensionality, the first factor (86.1%), second factor (3.8%), third factor (1.4%), fourth factor (1.4%), and fifth factor (0.7%) were all found to be unidimensional.

Regarding monotonicity, the mean QCM score for the high percentile group was not lower than the mean QCM score for the low percentile group on all items of the original ReoGo-J test (S4). In addition, the relationship between the QCM score and each patient’s predicted ability on each item of the original ReoGo-J test was moderately to highly related in Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient. These results also ensured monotonicity.

However, as anticipated during the design phase, analysis of the original ReoGo-J test results revealed some highly correlated items in the Q3 statistics, particularly for training items that shared the same “training task” and “assistance mode” but differed only in “reach range”.

Therefore, as described in the "Confirmation of Local Independence" section of the methods, to confirm the local independence of the eight items in the modified ReoGo-J test, we evaluated the local independence using Q3 statistics and other indicators. This analysis confirmed the local independence of approximately 93% of the items (S7). This sub-analysis did not clearly confirm that local independence was fully ensured. However, the results of the monotonicity test confirmed that all items were highly correlated with predictive ability (S4), and there was concern that the potential negative impact could be greater if several items were removed due to lack of local independence. Based on these results, it was decided to retain the results of the original ReoGo-J study without deleting any items, rather than adopt the results of the modified ReoGo-J analysis.

Discussion

This study aimed to create a program that automatically selects robot exercise items compatible with the severity of UE paralysis in ReoGo-J, a rehabilitation device for post-stroke UE motor disorders. The ReoGo-J test was created by selecting 71 items from all exercise items in the ReoGo-J. The ReoGo-J test was used to evaluate the adequacy of the difficulty level for each item in this study wherein over 300 patients with various severities of post-stroke UE paralysis performed all 71 items in the ReoGo-J.

The sample size for this study was 312. Previous simulation studies for this study have shown that a sample size of 300 or more was required for the design and statistical methods of this study to function properly14. In addition, other studies have suggested that in order to estimate item parameters using a 2PLM-GLM-IRT, the scale should have at least five items and the sample size should be at least 300 cases20. Therefore, the sample size used in this study is considered adequate. However, this was the first clinical study to use the original ReoGo-J test. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a confirmatory study in the future using the effect size obtained in this study to confirm the sample size in advance.

In this study, we examined whether there were problems with unidimensionality, monotonicity, and local independence in the sub-analysis. The results showed that only local independence was insufficient. To solve this problem, we developed the modified ReoGo-J test, which groups the items of the original ReoGo-J test for each training task to reduce the interdependence factors between items that affect local independence. In the modified ReoGo-J test, each of the eight items was scored on a 15-point or 20-point Likert scale according to the method shown in Table 1.

To confirm the local independence of 8items on the modified ReoGo-J test, we again used the Q3 statistic. Yen et al.21 state that if local independence cannot be ensured, the following measures should be taken: (1) developing independent items, (2) retesting under appropriate conditions, (3) grouping and scoring items with interdependencies, (4) reviewing to identify local dependencies, (5) grouping interdependent items, creating individual scales, and conducting re-evaluation, and (6) adopting testlets.

In this study, we implemented (4) and (5) and confirmed that there were no major problems with the local independence of the original ReoGo-J test through the results of the Q3 statistics of the modified ReoGo-J test. Therefore, it is believed that the measures taken in this study have adequately solved the problem of local independence.

The 2PLM-GRM-IRT analysis was performed to determine the predicted ability needed to perform each item of the ReoGo-J test. Similarly, the predicted ability of the function of the paralyzed UE of each patient with post-stroke UE paralysis was estimated from the results of the assessment of each item of the ReoGo-J test. Furthermore, the values of the UE items in FMA, which is considered the gold standard for assessing the degree of recovery of the paralyzed UE22, showed a strong correlation in this study.

In this study, a highly correlation was found between the predicted ability and the FMA scores for the shoulder-elbow-forearm. This result indicates that a patient’s predicted ability can be accurately estimated using the FMA, which is considered the gold standard assessment for UE paralysis after a stroke.

In other words, when a therapist measures the FMA score for the shoulder-elbow-forearm of a patient with upper limb paralysis in a clinical setting, they can estimate the patient’s ability to perform activities of daily living based on the FMA shoulder-elbow-forearm score. The specific procedure is as follows. First, in a clinical setting, the FMA shoulder-elbow-forearm is used to evaluate the function of the subject’s paralyzed UE. Next, by substituting this score of FMA shoulder-elbow-forearm into the formula (θ = 0.084 × FMA shoulder-elbow-forearm score-2.035 + error), the patient’s predicted ability is obtained. Once the predicted ability has been determined, the therapist can select appropriate training items that are likely to result in a QCM score of 1 point in the original version of the ReoGo test, as shown in A and B in Fig. 3. Through such a procedure, the results of this study have the potential to be useful in general clinical practice.

Previous studies on the treatment of post-stroke UE paralysis using robots have shown that inadvertently providing excessive robotic assistance in performing voluntary movements with the paralyzed UE can reduce the patient’s effort to perform UE movements or cause slacking13,23. Therefore, the developed program has clinical significance in that once the results of the FMA, the gold standard in motor paralysis, are known, the voluntary movements with the paralyzed UE can be derived automatically and reproducibly.

One of the limitations of the present study was the lack of empirical testing of the program. The developed program that automatically suggests ReoGo-J exercise items according to the degree of UE paralysis was predicted to be accurate and valid, as the predicted ability, which indicates the degree of difficulty of each item, was closely related to the FMA, the gold standard for evaluating the degree of recovery of the paralyzed UE. However, empirical studies using this program have not yet been conducted, and the evidence is insufficient. Non-inferiority RCTs should be conducted in the future to clarify the usefulness of this program.

Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to develop an automated rehabilitation program for post-stroke patients with UE paralysis, utilizing the ReoGo-J robotic device and IRT. Consequently, this study clarified the predicted ability required for patients to appropriately perform the 71 training tasks included in the ReoGo-J system. Additionally, a program was developed to identify the training items most likely to be suitable based on the predicted ability of each patient. The predicted ability also showed a highly correlation with the FMA shoulder-elbow-forearm score, which is the gold standard for clinical assessment of post-stroke UE paralysis. These findings supported the validity of this program and might indicate its potential value in clinical practice. However, this study did not prove the clinical effectiveness of this program. Further empirical studies, including non-inferiority RCTs, are needed to confirm its effectiveness in actual clinical settings.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

All authors thank the Hyogo Medical University Hospital Clinical Research Support Center for their support and assistance during study initiation and implementation.

Abbreviations

- UE

Upper extremity

- RCTs

Randomized controlled trials

- FMA

Fugl–Meyer Assessment

- 2PLM-GRM-IRT

Extending the two-parameter logistic model, the item response theory using the stage response model

- ICC

Item characteristic curve

- QCM

Quality of compensatory movement

- QOM

Quality of movement

- AIC

Akaike information criterion

- BIC

Bayesian information criterion

Author contributions

TT and YU contributed equally to the study design and manuscript writing and review. KD contributed to manuscript review. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Teijin Pharma Ltd., Tokyo, Japan.

Data availability

Anonymized participant data, study protocols, and analysis plans will be made available to scientific investigators upon approval by the Committee of the Investigation of ReoGo-J (Teijin Pharma Limited, Tokyo, Japan) training program with appropriate difficulty for paralyzed UE function after stroke: A prospective observational study (INDEX study). The proposals should be addressed to takshi77@omu.ac.jp or yutti@hyo-med.ac.jp. A Data Sharing Agreement must be signed by the data requester. Data requests can be made within two years of the publication of the paper.

Declarations

Competing interest

TT and YU report receiving personal fees and non-financial from Teijin Pharma Ltd. KD reports non-financial support from Teijin Pharma Ltd.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hyogo College of Medicine (#3354). The study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Registration details for this study are available at https://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/index-j.htm (UMIN000040127).

Consent for publication

The study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants to conduct the study and to prepare and publish the article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dobkin, B. H. Clinical practice. Rehabilitation after stroke. N. Engl. J. Med.352, 1677–1684 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakayama, H., Jørgensen, H. S., Raaschou, H. O. & Olsen, T. S. Compensation in recovery of upper extremity function after stroke: The Copenhagen Stroke study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil.75, 852–857 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winstein, C. J. et al. Guidelines for adult stroke rehabilitation and recovery: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke.47, e98–e169 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernhardt, J. et al. Agreed definitions and a shared vision for new standards in stroke recovery research: The stroke recovery and rehabilitation roundtable Taskforce. Int J Stroke.12, 444–450 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, Z. et al. Robot-assisted arm training versus therapist-mediated training after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Healthc. Eng.2020, 1–10 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takebayashi, T. et al. Robot-assisted training as self-training for upper-limb hemiplegia in chronic stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Stroke.53, 2182–2191 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rémy-Néris, O. et al. Additional, mechanized upper limb self-rehabilitation in patients with subacute stroke: The REM-AVC randomized trial. Stroke.52, 1938–1947 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodgers, H. et al. Robot assisted training for the upper limb after stroke (RATULS): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet.394, 51–62 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolbrecht, E. T., Chan, V., Reinkensmeyer, D. J. & Bobrow, J. E. Optimizing compliant, model-based robotic assistance to promote neurorehabilitation. IEEE Trans. Neural. Syst. Rehabil. Eng.16, 286–297 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu, X. L., Tong, K. Y., Song, R., Zheng, X. J. & Leung, W. W. A comparison between electromyography-driven robot and passive motion device on wrist rehabilitation for chronic stroke. Neurorehab. Neural. Repair.23, 837–846 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rowe, J. B. et al. Robotic assistance for training finger movement using a Hebbian model: A randomized controlled trial. Neurorehab. Neural. Repair.31, 769–780 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takebayashi, T. et al. Impact of the robotic-assistance level on upper extremity function in stroke patients receiving adjunct robotic rehabilitation: Sub-analysis of a randomized clinical trial. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil.19, 25 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cirstea, M. C. & Levin, M. F. Compensetory strategies for reaching in stroke. Brain.123, 940–953 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takebayashi, T., Uchiyama, Y., Okita, Y. & Domen, K. Development of a program to deter mine optimal settings for robot-assisted rehabilitation of the post-stroke paretic upper extremity: A simulation study. Sci Rep.13, 9217 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi, K. et al. Efficacy of upper extremity robotic therapy in subacute poststroke hemiplegia: An exploratory randomized trial. Stroke.47, 1385–1388 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greisberger, A., Aviv, H., Garbade, S. F. & Diermayr, G. Clinical relevance of the effects of reach-to-grasp training using trunk restraint in individuals with hemiparesis poststroke: A systematic review. J. Rehabil. Med.48, 405–416 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uswatte, G., Taub, E., Morris, D., Vignolo, M. & McCulloch, K. Reliability and validity of the upper-extremity motor activity log-14 for measuring real-world arm use. Stroke.36, 2493–2496 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yen, W. M. Effects of local item dependence on the fit and equating performance of the three-parameter logistic model. Appl. Psychol. Meas.8, 125–145 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smits, N., Zitman, F. G., Cuijpers, P. & den Hollander-Gijsman, M. E. Garlier IV. A proof of principle for using adaptive testing in routine outcome monitioring: The efficiency of the mood and anxiety symptoms questionnaire-anhednic depression CAT. BMC Med. Res. Methodol.12, 1–4 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dai, S. et al. Performance of polytomous IRT Models with rating scale data: An investigation over sample size, instrument length, and missing data. Front Educ.6, 721963 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yen, W. M. Scaling performance assessments: Strategies for managing local item dependence. J. Educ. Meas.30, 187–213 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker, K., Cano, S. J. & Playford, E. D. Outcome measurement in stroke: A scale selection strategy. Stroke.42, 1787–1794 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volpe, B. T. et al. Robotics and other devices in the treatment of patients recovering from stroke. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep.5, 465–470 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized participant data, study protocols, and analysis plans will be made available to scientific investigators upon approval by the Committee of the Investigation of ReoGo-J (Teijin Pharma Limited, Tokyo, Japan) training program with appropriate difficulty for paralyzed UE function after stroke: A prospective observational study (INDEX study). The proposals should be addressed to takshi77@omu.ac.jp or yutti@hyo-med.ac.jp. A Data Sharing Agreement must be signed by the data requester. Data requests can be made within two years of the publication of the paper.